FromPerceptionto Communication

ATheoryofTypesforActionandMeaning

ROBINCOOPER

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries ©RobinCooper2023

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted Somerightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,forcommercialpurposes, withoutthepriorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpressly permittedbylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriate reprographicsrightsorganization.

Thisisanopenaccesspublication,availableonlineanddistributedunderthetermsofa CreativeCommonsAttribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivatives4.0 Internationallicence(CCBY-NC-ND4.0),acopyofwhichisavailableat http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthislicence shouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,attheaddressabove PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2022945201 ISBN978–0–19–287131–2 DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192871312.001.0001

Printedandboundby CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

ForJon whowouldhavereadandunderstood andthensuggestedacompletelydifferentwayofdoingit

1.Fromperceptiontointensionality

2.Fromeventperceptionandactiontoinformationstatesand

3.Grammarinatheoryofaction

II.TOWARDSADIALOGICALVIEW

4.2Propernamesassigns

4.7Summaryofresourcesintroduced

5.Framesanddescriptions

5.1Introduction

5.2Commonnounsandindividualconcepts

5.3TheParteepuzzle

5.4Framesasrecords

5.5Framesandcommonnouns

5.6Definitedescriptionsasdynamicgeneralizedquantifiers

6.Modalityandintensionalitywithoutpossibleworlds

6.4Modalitywithoutpossibleworlds

6.5Intensionalitywithoutpossibleworlds

8.Type-basedunderspecification

Howtoreadthisbook

Thisbookisaddressedtodifferentaudiences.Themainideasofthebookcanbefollowed withoutdelvingintoallthetechnicaldetailsandIwouldencourageevenreaderswhohave technicalintereststogofortheintuitiveideasfirstandthenfillinthetechnicaldetailsof theirrealization.Technicaldevelopmentsthatmightbeskippedonfirstreadingarepresentedinboxes.Themaintechnicaldevelopmentofthetheoryoftypesintheseboxed areasiscollectedagainintheAppendixandsometechnicallyinterestedpeoplemaywant tostartthereandfollowtheleadsbackintothebodyofthebookforexamplesandmotivation.Inaddition,attheendofeachchapterthereisasummaryofwhathasbeenadded orchangedtothetreatmentoflinguisticphenomenasincethepreviouschaptersothat thedevelopmentcanbefollowedchapterbychapter.Thesesummariesuse(butdonot include)thetheoryoftypespresentedintheAppendix.

Whilethebookcanbereadasthedevelopmentofanargumentfrombeginningtoendit isnotnecessarytoreaditthatway.PartIofthebookgivesabasicintroductiontothekindof theoryoftypesthatIproposeandhowIwanttouseittoanalyseactionandcommunication fromadialogicpointofview.PartIItakesupanumberofcentralissuesintraditional formalsemanticsandreadersmaywanttoselectamongthesechaptersaccordingtotheir interests.Wherethelaterchaptersrelyonthingsintroducedinearlierchaptersthisisclearly markedandwillleadthereaderbacktotheappropriateplaceinthebook.

Whenreferringtotheoreticalobjectsinthetextweusesinglequotationmarks,e.g.the label‘e’,iftherepresentationoftheobjectdoesnotinvolvemathematicalorlogicalsymbols. Otherwisedoublequotationmarksareusedinthetextforitemssuchasinformaldescriptionsofobjectsintroducedinthetheory,translations,andquotations.Doublequotation marksarealsousedinformulaeandoccasionallyinthetexttorepresentinformallytypesof stringsofphonologicalevents,e.g.“Dudamelisaconductor”.Linguisticexamplesreferred tointhetext(asopposedtothenumberedexamples)areitalicized,e.g. Dudamelisaconductor.Namesoftypes,suchas Ind,for“individual”,areitalicizedandbeginwithacapital letter.

Materialrelatedtothisbookisavailableon https://sites.google.com/view/robincooper/ publications/ttrbook.

Introduction

Asweinteractwiththeworldandwitheachotherweneedtoclassifyobjectsandsituations;thatis,weneedtomakejudgementsaboutwhattypesofobjectsandsituationswe areconfrontedwith.Thisisanimportantpartofwhatisinvolvedinplanningthefuture actionsweshouldcarryoutandhowweshouldcoordinatewithotheragentsincarryingoutcollaborativeactions.Thisistrueofactioningeneral,includinglinguisticaction. Thisclassificationneedstobemultimodalinthatweneedtoclassifywhatweexperience throughdifferentsensesandbeabletocombinetheinformationinordertocometoa judgement.Theaimofthisbookistocharacterizeanotionoftypewhichwillcoverboth linguisticandnon-linguisticactionandtolaythefoundationsforatheoryofactionbased onthesetypes.Wewillarguethatatheoryoflanguagebasedonactionallowsustotakea perspectiveonlinguisticcontentwhichiscentredoninteractionindialogueandthatthisis importantlydifferenttothetraditionalviewofnaturallanguagesasbeingessentiallysimilartoformallanguagessuchaslogicsdevelopedbyphilosophersormathematicians.Atthe sametimewewillarguethatthetremendoustechnicaladvancesmadebytheformallanguageviewofsemanticscanbeincorporatedintotheaction-basedviewandthatthiscan leadtoimportantimprovementsbothofintuitiveunderstandingandempiricalcoverage. Inthisenterpriseweusetypesratherthanpossibleworldsascommonlyemployedinstudiesofthesemanticsofnaturallanguage.Typesaremoretractablethanpossibleworldsand giveusmorehopeofunderstandingtheimplementationofsemanticsbothonmachines andinbiologicalbrains.

PartIofthebook(Chapters 1–3)dealswithatheoryoftypesrelatedtoperceptionand actionandshowsawayofpresentingatheoryofgrammarwithinatheoryofaction.PartII (Chapters 4–8)thenlooksatanumberofcentralissuesinsemanticsfromadialogical pointofviewandarguesthatthereareadvantagestolookingatsomeoldpuzzlesfromthis perspective.

InChapter 1 weintroduceanotionofperceptionofanobjectorsituationasmakinga judgementthatitisofatype.Insymbols,wewrite a : T toindicatethat a isoftype T.We shalltalkinterchangeablyofsomethingbeingofatypeorbeingawitnessforatype.Our claimisthatperceivingsomethinginvolvesclassifyingitasbeingofatype,evenifthattype isverygeneral(like PhysicalObject or Event)—wecannotperceiveit simpliciter.Following KantwecannotperceivedasDingansich(“thethingitself”)butonlyintermsofatypethat weassigntoit.Wepresentbasicnotionsofthetheoryoftypeswhichwillbedevelopedin thebook,TTR,atheoryoftypeswithrecords,whichbuildstoagreatextentonideastaken fromthetypetheoryofPerMartin-Löfalthoughwehavemadesignificantchangesboth inthegeneraldesignandaimsofthetheoryandanumberofdetailswhichappeartous tobemotivatedbycognitiveandlinguisticconsiderations.Theoverallapproachpresented hereowesmuchtothetheoryofsituationsandsituationsemanticspresentedbyBarwise andPerryinthe1980s.Oneofthethemesofthisbookisaworkingoutofpartsoftheold situationtheoryusingideastakenfromMartin-Löf’stypetheory.

AcentralnotioninTTRisthatof record.Theterm“record”isusedincomputerscience forwhatisoftencalledanattribute-valuematrix(AVM)orfeaturestructureinlinguistics. Arecordisacollectionoffieldsconsistingofalabel(attributeorfeatureinthestandard linguisticwayoftalking)andanobjectofsomekind(whichitselfcanbearecord).A schematicexampleofarecordisgivenin(1),wherethe ℓi arelabelsandthe oi areobjects (includingsituations). (1)

Recordsarewitnessesforrecordtypeswhicharealsocollectionsoffields.Ratherthan objects,thefieldsinarecordtypecontaintypes.Intheschematicexamplein(2)the Ti are types. (2)

Therecord(1)willbeofthetype(2)justincasetheobjectsareofthetypeswiththesame labelling,thatis, o0 : T0, o1 : T1 and o2 : T2.Martin-Löf’sorginaltypetheorydidnot haverecordsorrecordtypesthoughtherehavebeenmanysuggestionsintheliteratureon howtoaddthem.WehaveborrowedfreelyfromsomeoftheseideasinTTRalthoughthe waywehavedevelopedthenotionsdiffersessentiallyfrompreviousproposals.Wewilluse recordsandrecordtypestomodelsituationsandsituationtypesinasenserelatedtothat ofsituationsemanticsasdevelopedbyBarwiseandPerry.Therecordsandrecordtypes arealsorelatedtodiscourserepresentationstructuresasintroducedbyKamp.

InChapter 2 weintroducesomebasicnotionsofatheoryofactionbasedonthesetypes whichwillbedevelopedfurtherasthebookprogressesandapplythetheoryoftypesfrom Chapter 1 tobasicnotionsofinformationupdateindialogue.Herewebuildonseminal workondialogueanalysisbyJonathanGinzburgandalsorelatedcomputationalimplementationbyStaffanLarssonleadingtotheinformationstateupdateapproachtodialogue systems.Wehaveadaptedtheseideasinawaythatallowsustopursuethequestionsof grammarandsemanticsthatwetakeupintheremainderofthebook.Acentralnotion hereisthatofthedialoguegameboardwhichweconstrueasatypeofinformationstate representingthecurrentstateofplayinthedialoguefromtheperspectiveofadialogue participant.Itincludesthedialogueparticipant’sviewofwhathasbeencommittedtoas beingtrueinthedialoguesofarandwhatquestionsarecurrentlyunderdiscussion.

InChapter3weshowhowsyntaxandsemanticscanbeembeddedinthetheoryofaction characterizedinChapters 1 and 2.Grammaticalrulesareregardedintermsofaffordances whichlicenseustodrawconclusionsaboutthetypestobeassociatedwithspeechevents onthebasisofspeecheventspreviouslyperceived.Thisisincontrasttoaformallanguage viewwherelanguageisseenasasetofanalysedstringsofsymbolsassociatedwithmeaningsofsomekind.Thephilosophicalgroundoftheaction-basedapproachgoesbackto therelationaltheoryofmeaningintroducedinBarwiseandPerry’ssituationsemantics whichfocussesontherelationbetweenutterancesituationsanddescribedsituations.This wasperhapsthefirstattempttogeneralizetheSpeechActTheorydevelopedbyAustinand

Searletotheconcernsofcompositionalinterpretationofsyntacticstructure.Italsoenables ustodevelopaformalapproachtodialogicaltheoriesoflanguagesuchasthosedeveloped bythepsychologistHerbClarkandthelinguistPerLinell.Arecenttheorytowhichthe ideasinthischapterarerelatedisthatofDynamicSyntax(DS).WhiletheparticularformulationsinourapproachlookratherdifferentfromthoseinDS,thetwotheorieshave commonaimsrelatingtotheanalysisoflanguageasactionandanemphasisontheincrementalnatureoflanguagewhichinthischapterwerelatetothebuildingofacharttype. Thereisalsoacommoninterestinthetreatmentoflanguageasasysteminfluxwhere anactofspeakingcancreateanewpreviouslyunavailablelinguisticresourcethatcanbe reusedinfuturespeechevents.

Thinkingofgrammarintermsofatheoryofactionleadsusintoanapproachtosyntaxandsemanticswhichemphasizeshowwereasonaboutspeecheventsandtheirtypes. Thisrelatestoseveralstrandsinlinguisticanalysiswhichemphasizetheinferentialnature ofsyntacticandsemanticprocessingincludingPereiraandWarren’sparsingasdeduction,variouskindsofcategorialgrammarincludingMorrill’sTypeLogicalGrammarand gluesemanticsasusedinLexicalFunctionalGrammar(LFG)byDalrympleandothers. OfparticularimportanceisAarneRanta’sworkonType-TheoreticalGrammarandthe GrammaticalFramework.Theuseofrecordsandrecordtypesandtheirsimilaritytotyped featurestructuresmakesthenotionofgrammarherecloselyrelatedtothatofHeadDriven PhraseStructureGrammar(HPSG).

Thetheoryoftypesthatweemploygivesustwonotionswhichwillbeimportantin thedevelopmentofsemanticsinPartII.Thefirstisthenotionof intensionality.Typesin TTRareintensionalinthattheidentityofatypeisnotestablishedintermsofthesetof witnessesofthattype.Thatis,typesarenotextensionalinthewaythatsetsareinastandard settheory.Theaxiomofextensionalityinstandardsettheoryrequiresthattherecannot betwosetswhichhavethesamemembers.Incontrast,therecanbedifferenttypeswhich haveexactlythesamesetofwitnesses.Thesecondnotionhastodowiththefactsthatthe typesthemselvesaretreatedasobjectsthatcanenterintorelationsandbeusedtoconstruct newtypes.Wewillcallthis firstclasscitizenshipoftypes,thoughitisrelatedtonotionsof intentionality (witha“t”)and reflection inprogramminglanguages,thatis,theabilitynot onlytocarryoutproceduresbuttoreflectonandreasonaboutthem.Inourterms,an importantenablingfactorforhumanlanguageisthatwenotonlycanperceiveobjectsand situationsintermsoftypesandactontheseperceptionsbutthatwecanalsoreasonabout andactonthetypesthemselves,forexample,inascribingthemtootheragentsasbeliefs ormakingaplantoachieveagoalbycreatinganeventofacertaintype.Thetypesbecome cognitive resources whichwecanexploitinourcommunicativeactivity.InPartIIwewill lookatanumberofexamplesofthis.

InChapter 4 weexaminereferencebyusesofpropernamesandoccurrencesofpronounswhicharenotboundbyquantifiers.Inordertoaccountforthisweneedanotionof parametriccontent,whichistosaythatthecontentofanutterancedependsonacontext belongingtoacertaintype.Forexample,anutteranceofthepropername Sam requiresa contextinwhichthereisanindividualnamed“Sam”.Butwhereinherresourcesshoulda dialogueparticipantlookforsuchacontext?OneobviousplaceistheconversationalgameboardthatweintroducedinChapter 2.Thatis,thedialogueparticipantshoulddetermine whethertherehasbeenreferencetosomebodyofthatnamealreadyinthecurrentdialogueaccordingtohergameboard.Anotherplaceisthevisualscene,ormoregenerally

theambientsituationwhichtheagentcanperceivebydifferentsensemodalities.Thiswe alsorepresentasaresourceusingatype—thatis,thetypeforwhichtheambientsituation wouldbeawitnessiftheagent’sperceptioniscorrect.Yetanotherplacetolookistheagent’s long-termmemory(whichwewillequatewiththeagent’sbeliefs,althoughonemayultimatelywishtomakeadistinction).Thisresourceisalsomodelledasatyperepresenting howtheworldwouldbeiftheagent’smemoryorbeliefsarecorrect.(Thestructurednature ofrecordtypesmeansthattheycanbeusedineffectaslargerepositoriesofinformation indexedbythepathsprovidedbythelabelsintherecordtype.)Thefactthatwearereasoningabouttheextenttowhichthecontexttypeassociatedwiththeutterancematchesthe typesmodellingtheagent’srelevantresourcesenablesustotalkaboutcaseswherethere arenamesofnon-existentobjects(thatis,theagent’sresourcetypesdonotexactlymatch theworld)orwhereasingleobjectintheworldcorrespondstotwoobjectsintheresources orviceversa(anotherwayinwhichtherecanbeamismatchbetweenrealityandanagent’s resources).Theproposaltorepresentdifferentaspectsofmentalstatesintermsofrecord typesiscloselyrelatedto(andinspiredby)similarproposalsforrepresentingmentalstates usingdiscourserepresentationstructures.

InChapter5welookatframesassociatedwithcommonnouns.(Therestrictiontocommonnounsherehastodowiththeexamplesthatwillbediscussedandisnotaclaim thatonlycommonnounsareassociatedwiththekindsofframeswepropose.)Theidea offramesgoesbacktoearlyworkonframesemanticsbyFillmoreandalsopsychological workonframesbyBarsalou.Wewillconstrueframesassituations(modelledasrecordsin TTR).Wewillarguethatframetypesareanadditionalkindofresourcewhichisexploited innaturallanguagesemantics.Acommonnounlike dog,inadditiontobeingassociated withthepropertyofbeingadog(thatis,asimplepropertycharacterizedintermsofthe singlepredicate‘dog’),canalsobeassociatedwithatypeofsituation(aframetype)which iscommonfordogs,forexample,wherethedoghasaname,anageandvariousother attributeswecommonlyattributetodogs.Wewillarguethatsuchaframecanplayan importantroleininterpretingutterancessuchas thedogisnine inthesenseof“thedogis nineyearsold”.Somenouns,suchastemperature,seemtorepresentframelevelpredicates, followingananalysissuggestedbySebastianLöbnerinordertoaccountfortheanalysis ofutteranceslike thetemperatureisrising whereitisnotthecasethatsomeparticular temperatureisrising(say,30°)butthatdifferentsituations(frames)withdifferenttemperaturesarebeingcompared.Nounswhichnormallypredicateofindividualscanbecoerced topredicateofframes.Anexampleisthenoun ship inanexampleoriginallydiscussed byManfredKrifka: fourthousandshipspassedthroughthelock whichcaneithermean thatfourthousanddistinctshipspassedthroughthelockorthattherewerefourthousand ship-passing-through-the-lockeventssomeofwhichmayhaveinvolvedthesameship.We arguethatinordertointerpretsuchexamplesyouneedtohaveasaresourceanappropriate frametypeassociatedwiththenoun ship

InChapter6weexplorephenomenainnaturallanguagewhicharestandardlyreferredto asmodal andintensional.Wearguethattypesasweconceivethemarebetterplacedtodeal withthesephenomenathanthepossibleworldsthatareusedinstandardformalsemantics.Instandardformalsemanticspropositionsareregardedassetsofpossibleworlds. Forexample,thepropositioncorrespondingto aboyhuggedadog isthesetofalllogicallypossibleworldsinwhichaboyhuggedadogistrue.Whatwesubstituteforthisis thetypeofsituationsinwhichaboyhuggedadog.Atanintuitivelevelthesenotionsare

quitesimilar.Theybothrepresentmathematicalobjectswhichallowformanydifferent possibilitiesaslongasthefactthataboyhuggedadogisheldconstantacrossthem.One importantdifferenceisthatsetsofpossibleworldsareextensionalsetswhereasourtypes areintensional.Thusitispossibleforustohavetwodistincttypeswhichhaveexactlythe samewitnesses.Onepairofsuchexampleswediscussis KimsoldSyntacticStructuresto Sam and SamboughtSyntacticStructuresfromKim.Intuitivelywewantthesetorepresent differentpropositionsandwearguethattheycanyielddifferenttruthconditionswhen embeddedunderapredicatelike legal.(UnderSwedishlaw,forexample,itisillegaltobuy sexbutlegaltosellsex.)Anotherpairinvolvesso-calledmathematicalpropositionswhich aretrueinallpossibleworldsbutwhichneverthelesswewouldwanttorepresentdifferentpropositions: Twoplustwoequalsfour and Fermat’slasttheoremistrue (asprovedby AndrewWiles).

Thechapterbeginswithadiscussionoftheproblemsassociatedwithpossibleworlds analyses.WethencontinuewithadiscussionofmodalityandinparticularofhowAngelika Kratzer’snotionsofconversationalbackgroundandidealscanbeseenasresourcesbased ontypesandthekindoftopoithatEllenBreitholtzhasintroducedintheTTRliterature. Inthethirdpartofthechapterwediscusswhataretraditionallyregardedasintensional constructionsinvolvingattitudeverbslikebelieveandintensionalverbslikeneedandwant. Wetreat‘believe’asarelationbetweenindividualsandtypes(correspondingtothecontent oftheembeddedsentence).Foranindividualtobelieveatypeithastobethecasethatthe typematches(inawaywemakeprecise)thetypewhichmodelsthebeliefs(orlong-term memory)oftheindividual,thatisthesameresourcethatwasneededinChapter 4 toget thedialogicalanalysisofpropernamestoworkout.

InChapter 7 welookatgeneralizedquantifiersfromtheperspectiveofdialogicinteraction.Traditionallygeneralizedquantifiersaretreatedassetsofsetsorsetsofproperties andtheworkofBarwiseandCooperongeneralizedquantifiersbuiltonthisidea.BarwiseandCooperalsointroducedtheauxiliarynotionofwitnesssetforquantifiersunder theheading“Processingquantifiedstatements”.Inthischapterweturnthingsaroundand makethecharacterizationofwitnesssetstheprimarynotionindefiningquantifiers.This makesitmorestraightforwardtoaccountfortheanaphoricpossibilitiesrelatingtoquantifiedexpressionsindialogue.Weoftenusequantifiedstatementsindialoguewhenwehave inadequateinformationtodeterminetheirtruth.Thisisparticularlytrueofdeterminers like every and most whentalkingaboutlargesets.Wesuggestthatthisphenomenoncan beanalysedbyestimatingaprobabilitybasedontheevidencepresentedinourcognitive resources(long-termmemoryorbeliefsasdiscussedinChapters 4 and 6).

InChapter 8 wegiveanaccountofhowTTRtypescanbeusedtotalkofcontentwhich isunderspecified.Theideaistoexploitthenotionoftypeswhichcanhaveseveralwitnessesas“underspecifications”ofthosewitnesses.Ratherthanassociatingcontentswith utterancesaswehavedoneintheearlierchapters,weassociatetypesofcontentswithutterances.Thusadialogueparticipantwhenobservingaspeecheventassociatesitwithatype ofcontentratherthanaparticularcontent.Weshowhowearlierideasaboutthetreatment ofunderspecificationofquantifierscopeandanaphoracanbeaccommodatedinthisview.

Fromperceptiontointensionality

1.1 Introduction

Whenweperceiveobjectsandeventsweclassifythemasbelongingtosometype.Inthis chapterwewillexplainthisideaandintroduceamathematicaltheoryofsomeofthetypes weuse.Perceptionandtheuseofnaturallanguageforcommunicationarecloselylinked. Types,particularlytypesofevents,areagoodmodelforwhatareoftencalled“propositions”,trueifthereissomethingofthetypeandfalseifthereisnothingofthetype.Itseems thattheoriginoflinguisticmeaningseemscloselyrelatedtoperception.Ifyouaretalking toatwo-year-oldchild,youtendtopointatphysicalobjectsorobservableeventsandutter thecorrespondingwordorphrase.Youdonottalkaboutabstractconceptslike‘university’, ‘democracy’,‘thought’,or‘feeling’.Thesecomelater.Wewillargueinthisbookthathumans havebuiltonthebasicperceptualapparatusintermsoftypesinawaythatallowsthemto reasonaboutthetypesthemselvesandthatitisthisabilitywhichallowsustotalkabout intensionalnotionslike‘belief’and‘knowledge’.

Inthischapterwewilltalkfirstaboutthenotionofperceptionastypeassignment(Section 1.2).Wewillthenlaythebasisforourmathematicalmodellingoftypes (Section1.3).Weintroduceanotionofsituationtype(Section1.4)whichwillbeimportant fortheideathattypesareusedtomodelpropositions(discussedinSection 1.5).Included inthekindsoftypesweuseassituationtypesaretypesconstructedfrompredicatesand theirarguments(ptypes)andtypeswhicharecollectionsoflabelledfields(recordtypes).

1.2 Perceptionastypeassignment

Kimisoutforawalkintheparkandseesatree.Sheknowsthatitisatreeimmediatelyand doesnotreallyhavetothinkanythingparticularlylinguistic,suchas“Aha,that’satree”.Asa humanbeingwithnormalvisualperception,Kimisprettygoodatrecognizingsomething asatreewhensheseesit,providedthatitisafairlystandardexemplar,andtheconditions areright:forexample,thereisenoughlightandsheisnottoofarawayortooclose.Weshall saythatKim’sperceptionofacertainobject, a,asatreeinvolvestheascriptionofatype Tree to a.Intermsofthekindoftypetheorydiscussedby Martin-Löf (1984); Nordström etal. (1990),wemightsaythatKimhasmadethe judgement that a isoftype Tree (in symbols, a : Tree).

Objectscanbeofseveraltypes.Anobject a canbeoftype Tree butalsooftype Oak (a subtypeof Tree,sinceallobjectsoftype Oak arealsooftype Tree)and PhysicalObject (a supertypeof Tree,sinceallobjectsoftype Tree areoftype PhysicalObject).Itmightalso beofanintuitivelymorecomplicatedtypelike ObjectsPerceivedbyKim whichisneither asubtypenorasupertypeof Tree sincenotallobjectsperceivedbyKimaretreesandnot alltreesareperceivedbyKim.

FromPerceptiontoCommunication.RobinCooper,OxfordUniversityPress. ©RobinCooper(2023).DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192871312.003.0002

Thereisnoperceptionwithoutsomekindofjudgementwithrespecttotypesoftheperceivedobject.Whenwesaythatwedonotknowwhatanobjectis,thisnormallymeans thatwedonothaveatypefortheobjectwhichisnarrowenoughforthepurposesathand. Itripoversomethinginthedark,exclaiming“What’sthat?”,butmypainfulphysicalinteractionwithitthroughmybigtoetellsmeatleastthatitisaphysicalobject,sufficiently hardandheavytoofferresistancetomytoe.Theactofperceivinganobjectisperceiving it as something.Youcannotperceivesomethingwithoutascribingsometypetoit,evenif itisaverygeneraltypesuchas Thing or Entity

Whatwecallmakingajudgementorascribingatype,isnotnecessarilyalinguisticor evenconsciousprocess.Itissomethingthatprelinguisticchildrenandevennon-humans cando.Itinvolvesanagentbeingabletoengageinacertainkindofbehaviourwhen confrontedwithacertaintypeofobject.Typesinvolvedinperceptioncorrespondtothe kindofcategoriesthataretalkedaboutinthelargepsychologicalliteratureonperceptual categories.Foranoverviewsee Mareschal etal. (2010).

Recognizingsomethingasatreemaybeimmediateandnotinvolveconsciousreasoning.Recognizingatreeasanaspen,anelm,oratreewithDutchelmdiseasemayinvolve closerinspectionandsomeconsciousreasoningabouttheshapeoftheleavesorthestate ofthebark.Forhumanstherelatingofobjectstocertaintypescanbetheresultofalong chainofreasoninginvolvingagreatdealofconsciouseffort.Butwhethertheperception isimmediateandautomaticortheresultofaconsciousreasoningprocess,fromalogical pointofviewitstillseemstoinvolvetheascriptionofatypetoanobject.

Thekindoftypeswearetalkingaboutherecorrespondtoprettymuchanyusefulwayof classifyingthingsandtheycorrespondtowhatmightbecalledpropertiesinothertheories. Forexample,intheclassicalapproachtoformalsemanticsdevelopedby Montague (1974) andexplicatedby Dowty etal. (1981)amongmanyothers,propertiesareregardednotas typesbutasfunctionsfrompossibleworldsandtimesto(thecharacteristicfunctionsof) setsofentities;thatis,thepropertytreewouldbeafunctionfrompossibleworldsandtimes tothesetofallentitieswhicharetreesatthatworldandtime.Montaguehastypesbasedon aversionofRussell’s(1903)simpletheoryoftypesbuttheywere“abstract”typeslikeEntity and TruthValue andtypesoffunctionsbasedonthesetypesratherthan“contentful”types likeTree.TypetheoryforMontaguewasawayofprovidingbasicmathematicalstructureto thesemanticsysteminawaythatwouldallowthegenerationofinterpretationsofinfinitely manynaturallanguageexpressionsinanorderlyfashionthatwouldnotgetintoproblems withlogicalparadoxes.Thedevelopmentofthetheoryoftypeswhichwewillundertake herecanberegardedasanenrichmentofan“abstract”typetheorylikeMontague’swith “contentful”types.Wewanttodothisinawaythatallowsthetypestoaccountforcontent andrelatetocognitiveprocessingsuchasperception.Wewantourtypestohavepsychologicalrelevanceandtocorrespondtowhat Gibson (1979)mightcall invariants,thatis, aspectsthatwecanperceivetobethesamewhenconfrontedwithsimilarobjectsorthe sameobjectfromadifferentperspective.Inthisrespectourtypesaresimilartonotions developedinsituationtheoryandsituationsemantics(BarwiseandPerry, 1983; Barwise, 1989).

Gibson’snotionofattunementisadoptedbyBarwiseandPerry.Theideaisthatcertainorganismsareattunedtocertaininvariantswhileothersarenot.SupposethatKim perceivesacherrytreewithflowersandthatabeealightsononeoftheflowers.One assumesthatthebee’sexperienceofthetreeisverydifferentfromKim’s.Itseemsunlikely

thatthebeeperceivesthetreeasatreeinthesensethatKimdoesanditisnotatallobvious thatthebeeperceivesthetreeinitstotalityasanobject.Differentspeciesareattunedtodifferenttypesandevenwithinaspeciesdifferentindividualsmayvaryinthetypestowhich theyareattuned.Thismeansthatourperceptionislimitedbyourcognitiveapparatus—not averysurprisingfact,ofcourse,butphilosophicallyveryimportant.Ifperceptioninvolves theassignmentoftypestoobjectsandweareonlyabletoperceiveintermsofthosetypes towhichweareattuned,then,as Kant (1781)pointedout,wearenotactuallyabletobe awareofdasDingansich(“thethingitself”);thatis,wearenotabletobeawareofanobject independentlyofthecategories(ortypes)whichareavailabletousthroughourcognitive apparatus.

1.3 Modellingtypesystemsintermsofmathematicalobjects

Inordertomakeourtheoryprecisewearegoingtocreatemathematicalmodelsofthesystemswepropose.Thisrepresentsoneofthetwomainstrategiesthathavebeenemployed inlogictocreaterigoroustheories.Theotherapproachistocreateaformallanguageto describetheobjectsinthetheoryanddefinerigorousrulesofinferencewhichexplicate thepropertiesoftheobjectsandtherelationsthatholdbetweenthem.Atacertainlevel ofabstractionthetwoapproachesaredoingthesamething—inordertocharacterizea theoryyouneedtosaywhatobjectsareinvolvedinthetheory,whichimportantpropertiestheyhave,andwhatrelationstheyenterinto.However,thetwoapproachestendto getassociatedwithtwodifferentlogicaltraditions:the modeltheoretic and prooftheoretic traditions.

Thephilosophicalfoundationoftypetheory(aspresented,forexample,by Martin-Löf, 1984)isnormallyseenasrelatedtointuitionismandconstructivemathematics.Itis,at bottom,aproof-theoreticdisciplineratherthanamodel-theoreticone(despitethefact thatmodeltheorieshavebeenprovidedforsometypetheories).However,itseemsthat manyoftheideasintypetheorythatareimportantfortheanalysisofnaturallanguage canbeadoptedintotheclassicalsettheoreticframeworkfamiliartolinguistsfromthe classicalmodel-theoreticcanonofformalsemanticsstartingfrom Montague (1974).We assumeastandardunderlyingsettheorysuchasZF(Zermelo-Fraenkel)withurelements (asformulatedforexamplein Suppes, 1960).Thisiswhatwetaketobethecommonor gardenworkingsettheorywhichisfamiliarfromthecoreliteratureonformalsemantics derivingfromMontague’soriginalwork.

Atheoryisnotveryinterestingifitdoesnotmakepredictions;thatis,bymakingcertain assumptionsyoucaninfersomeconclusions.Thisgivesyouonewaytotestyourtheory: seewhatyoucanconcludefrompremisesthatyouknoworbelievetobetrueandthen testwhethertheconclusionisactuallytrue.Ifyoucanshowthatyourtheoryallowsyouto predictsomeconclusionanditsnegation,thenyourtheoryisinconsistent,whichmeans thatitisnotusefulasascientifictheory.Onewaytodiscoverwhetheratheoryisconsistent ornotistoformulateitverycarefullyandexplicitlysothatyoucanshowmathematical propertiesofthesystemandanyinconsistencieswillappear.

Fromtheinformaldiscussionoftypetheorythatwehaveseensofar,itisclearthatit shouldinvolvetwokindsofentity:thetypesandtheobjectswhichareofthosetypes.(Here weusetheword“entity”notinthesensethatMontaguedid,thatis,basicindividuals,

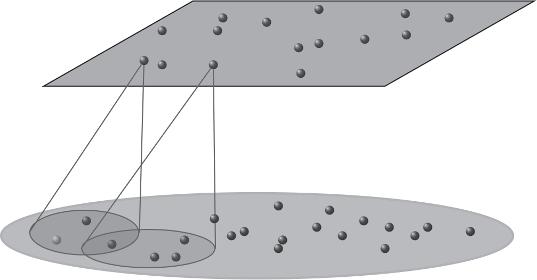

butasaninformalnotionwhichincludesbothobjectsandtypes.)Thismeansthatwe shouldcharacterizeatypetheorywithtwodomains:onedomainfortheobjectsofthe typesandanotherdomainforthetypestowhichtheseobjectsbelong.Thusweseetypes astheoreticalentitiesintheirownright,not,forexample,ascollectionsoftheobjects whichareobjectsofthetypes.DiagrammaticallywecanrepresentthisasinFigure 1.1 whereobject a isoftype T1.

Figure1.1 Systemofbasictypes

Asystemofbasictypesconsistsofasetoftypeswhichare basic inthesensethatthey arenotanalysedas complex entitiescomposedofotherentitiesinthetheory.Eachofthese typesisassociatedwithasetofobjects,thatis,theobjectswhichareofthetype,the witnesses forthetype.Thusif T isatypeand A(T) isthesetofwitnessesfor T,then a isof type T (insymbols, a : T)justincase a ∈ A(T).Werequirethatanyobject a whichisa witnessforabasictypeisnotitselfoneofthetypesinthesystem.(Thisrequirementwill berelaxedlaterindifferentkindsoftypesystems.)Atypemaybe empty inthesensethat itisassociatedwiththeemptyset;thatis,thereisnothingofthattype.

Noticethatwearestartingwiththetypesandassociatingsetsofobjectswiththem.This meansthatwhiletherecanbetypesforwhichtherearenowitnesses,therecannotbe objectswhichdonotbelongtoatype.ThisrelatesbacktoourclaiminSection 1.2 that wecannotperceiveanobjectwithoutassigningatypetoit.

Noticealsothatthesetsofobjectsassociatedwithtypesmayhavemembersincommon. Thusitispossibleforobjectstobelongtomorethanonetype.Thisisimportantifwewant tohavebasictypes Elm, Tree,and PhysicalObject,andsaythatasingleobject a belongsto allthreetypesasdiscussedinSection 1.2.

Anextremelyimportantpropertyofthiskindoftypesystemisthatthereisnothing whichpreventstwotypesfrombeingassociatedwithexactlythesamesetofobjects.In standardsettheorythenotionofsetis extensional;thatissetsaredefinedbytheirmembership.Youcannothavetwodistinctsetswithexactlythesamemembers.Thechoiceof definingtypesasentitiesintheirownrightratherthanasthesetsoftheirwitnessesmeans thattheycanbe intensional;thatis,youcanhavemorethanonetypewiththesamesetof witnesses.Thiscanbeimportantfortheanalysisofnaturallanguagewordslike groundhog andwoodchuckwhich(asIhavelearnedfromtheliteratureonnaturallanguagesemantics) arethesameanimal.Inthiscaseonemaywishtosaythatyouhavetwodifferentwords whichcorrespondtothesametype,ratherthantwotypeswiththesame extension (that is,setofwitnesses).Suchananalysisislessappealinginthecaseof unicorn and centaur,

bothmythicalanimalscorrespondingtotypeswhichhaveanemptyextension.Iftypes wereextensional,therewouldonlybeoneemptytype(justasthereisonlyoneemptyset insettheory).InthekindofpossibleworldsemanticsespousedbyMontague,thedistinctionbetween unicorn and centaur wasmadebyconsideringtheirextensionnotonly intheactualworld(wherebothareempty)butalsoinallpossibleworlds,sincetherewill besomeworldsinwhichtheextensionsarenotthesame.However,thiskindofpossible worldsanalysisofintensionalityfailswhenyouhavetypeswhoseextensionscannotpossiblybedifferent.Consider roundsquare and positivenumberequalto 2 5.Thepossible worldsanalysiscannotdistinguishbetweenthesesincetheirextensionsarebothemptyno matterwhichpossibleworldyoulookat.

Finally,noticethattheremaybedifferentsystemsofbasictypes,possiblywithdifferent typesanddifferentobjects.OnewayofexploitingthiswouldbetoassociatedifferentsystemswithdifferentorganismsasdiscussedinSection 1.2.(Laterinthisbookwewillsee differentusesofthisfortheanalysisoftypeswhichmodelthecognitivesystemofasingle agent.)Thus,properlyweshouldsaythatanobject a isoftype T withrespecttoasystem ofbasictypes TYPEB,insymbols, a :TYPEB T.However,wewillcontinuetowrite a : T in ourinformaldiscussionwhenthereisnodangerofconfusion.

Thedefinitionofasystemofbasictypesismadeprecisein(1),whichisrepeatedin Appendix A2.

(1) A systemofbasictypes isapair:

TYPEB = ⟨Type, A⟩

where:

1. Type isanon-emptyset

2. A isafunctionwhosedomainis Type

3. forany T ∈ Type, A(T) isasetdisjointfrom Type

4. forany T ∈ Type, a :TYPEB T iff a ∈ A(T)

Somereadersmaypreferaslightlylessformalcharacterizationwhichusesthekindof formatnormallyemployedinprooftheory.Thismayprovideamoreeasilyreadable overviewofthedefinitionswhilesuppressingsomeofthedetailswhicharenotnecessaryforintuitiveunderstanding.Wewilluse Γ,normallyusedforcontextsinproof theory,thatissequencesofjudgementstorefertotypesystemslikethosecharacterized in(1).Thusin(2) Γ correspondsto TYPEB.Wewillwrite Γ ⊢ T ∈ Type “T ∈ Type followsfrom Γ”torepresentthat Type isthesetoftypesin Γ asspecifiedin(1)andthat thetype T isamemberofthisset.Wewillsimilarlywrite Γ ⊢ a ∈ A(T) toindicatethat object a isinthesetassignedto T bythefunction A givenby Γ.Wecanthenwritearule asin(2).

(2) For Γ asystemofbasictypes:

Γ ⊢ T ∈ Type Γ ⊢ a ∈ A(T)

Γ ⊢ a : T continued

Wetakethistobeaninductivedefinitionofthesetofconsequences.Thatis,weare characterizingthesmallestsetofjudgements Γ ⊢ a : T whichobeythepremises.In thiswaytheinferencerule(2)hastheforceofabiconditionalcorrespondingtoclause4 in(1).

ThefactthatwearerelatingthewitnessesoftypestoasetassignedtothetypeoccasionallyleadstothemisunderstandingthattypesinTTRarejustsetsornamesofsets (ChatzikyriakidisandLuo, 2020,p.17).Hopefullythediscussionaboveandthedevelopmentsundertakenintherestofthebookwillmakeclearthattheyaremathematical objectsintheirownrightanddistinctfromthecollectionsoftheirwitnesses.Theuseof setsheregivesusaconvenientwaytorelatetothekindofmodeltheorywhichisusedin Montagovianformalsemantics.However,elsewhereintheTTRliteraturebasictypes areoftenassociatedwithclassifiers(Cooper,2019;Larsson,2020,forexample)andthis possibilityisanimportantaspectofhavingtypesasobjectsandnotidentifyingthem withcollectionsoftheirwitnesses.

Whatcountsasanobjectmayvaryfromagenttoagent(particularlyifagentsareofdifferentspecies).Differentagentshavewhat Barwise (1989)wouldcalldifferent schemesof individuation.Itevenseemslikelythatasingleagentmightswitchquiteeasilybetweendifferentschemesofindividuation.Forexample, Cooper (2011)discusseswhatmightcount asindividualbooks:forexample,physicalvolumes,aparticulartext,atextanditstranslationsintootherlanguages.Thereappearstobeacomplexrelationshipbetweenthetypes thatanagentisattunedtoandthepartsoftheworldwhichtheagentwillperceiveasan object.Wemodelthisinpartbyallowingdifferenttypesystemstohavedifferentobjects. Inadditionwewillmakeextensiveuseinoursystemsofabasictype Ind or“individual” whichcorrespondstoMontague’snotionof“entity”.Thetype Ind mightbethoughtofas modellingalargepartofanagent’sschemeofindividuationinBarwise’ssense.However, thisclearlystillleavesagreatdealtobeexplainedandwedothisinthehopethatexploringthenatureofthetypesystemsinvolvedwillultimatelygiveusmoreinsightintohow individuationisachieved.

1.4 Situationtypes

Kimcontinuesherwalkinthepark.Sheseesaboyplayingwithadogandnoticesthat theboygivesthedogahug.Inperceivingthiseventsheisawarethattwoindividualsare involvedandthatthereisarelationholdingbetweenthem,namelyhugging.Shealsoperceivesthattheboyishuggingthedogandnottheotherwayaround.Sheseesthatacertain action(hugging)isbeingperformedbyanagent(theboy)onapatient(thedog).Thisperceptionseemsmorecomplexthantheclassificationofanindividualobjectasatreeinthe sensethatitinvolvestwoindividualparticipantsandarelationbetweenthemaswellasthe rolesthosetwoindividualsplayintherelation.Whileitisundoubtablymorecomplexthan thesimpleclassificationofanobjectasatree,wewanttosaythatitisstilltheassignment ofatypetoanobject.Theobjectisnowaneventandsheclassifiestheeventasahugging eventwiththeboyasagentandthedogaspatient.Weshallhavecomplextypeswhichcan beassignedtosuchevents.

Complex typesareconstructedoutofotherentitiesinthetheory.Aswehavejustseen, cognitiveagents,inadditiontobeingabletoassigntypestoindividualobjectsliketrees, alsoperceivetheworldintermsofstatesandeventswhereobjectshavepropertiesand standinrelationstoeachother—what Davidson (1967)calledeventsand Barwiseand Perry (1983)calledsituations.Forthepurposesofthisbookwewilltendtousethewords situation and event interchangeably,althoughproperlyaneventshouldbeconsidereda situationwheresomethinghappens(asopposedtoastatewheresomethingpersistsin holdingtrue).

1.4.1 Typesconstructedfrompredicates(ptypes)

Weintroducetypeswhichareconstructedfrompredicates(like‘hug’)andobjectswhich areargumentstothispredicate.If a and b areobjects,wewillrepresentsuchaconstructed typeashug(a,b)andwewillcallitaptypetoindicatethatitisatypewhosemainconstructor isapredicate.Whatwouldanobjectbelongingtosuchatypebe?AccordingtothetypetheoreticapproachintroducedbyMartin-Löfitshouldbeanobjectwhichconstitutesa proofthat a ishugging b.ForMartin-Löf,whowasconsideringmathematicalpredicates, suchproofobjectsmightbenumberswithcertainproperties,orderedpairs,andsoon. Ranta (1994)pointsoutthatfornon-mathematicalpredicatestheobjectscouldbeevents asconceivedby Davidson (1967, 1980).Thushug(a,b)canbeconsideredtobeanevent typeorasituationtype.Insomeversionsofsituationtheory(Barwise,1989;Seligmanand Moss, 1997),objects(called infons)constructedfromarelationanditsargumentswere consideredtobeonekindofsituationtype.Theterm“infon”wasmeanttosuggestthatthey wereminimalunitsofinformation.Oneviewwouldbethatptypesareplayingasimilar roletotherolethatinfonsplayinsituationtheory,allowingustoconstructsituationtypes intermsofoneormoreptypes.

Whatkindofentityarepredicates?Oneimportantfactaboutpredicatesisthatthey comealongwithan arity.Thearityofapredicatetellsyouhowmanyandwhatkindof argumentsthepredicatetakesandwhatordertheycomein.Forus,thearityofapredicate willbeasequenceoftypes.Thepredicate‘hug’,asdiscussedjustabove,wecanthinkofas atwo-placepredicatebothofwhoseargumentsmustbeoftype Ind,thatis,anindividual. Thusthearityof‘hug’willbe ⟨Ind, Ind⟩.Theideaisthatifyoucombineapredicatewith argumentsoftheappropriatetypesintheappropriateorderindicatedbythearitythenyou willhaveatype.Thusif a : Ind and b : Ind thenhug(a,b)willbeatype,intuitivelythetype ofsituationwhere a hugs b.

Wewillintroduceafunction Arity whichisdefinedonpredicatesandwhichassigns anaritytoanypredicate.Thisfunctionisintroducedina predicatesignature whichin additiontellsyouwhatpredicatesthereareandwhatwecanusetocharacterizetheir arguments(asetoftypesinthewaywewillusethis).Wedefineapredicatesignature bythedefinitionin(3)(repeatedinAppendix A3.1). continued

(3) A predicatesignature isatriple

⟨Pred, ArgIndices, Arity⟩

where:

1. Pred isaset(ofpredicates)

2. ArgIndices isaset(ofindicesforpredicatearguments,normallytypes)

3. Arity isafunctionwithdomain Pred andrangeincludedinthesetoffinite sequencesofmembersof ArgIndices.

Asimpleexampleofapredicatesignaturewouldbegivenby(4).

(4) a. Pred ={boy,dog,hug}

b. ArgIndices ={Ind}

c. Arity isdefinedby:

Arity(boy)= ⟨Ind⟩

Arity(dog)= ⟨Ind⟩

Arity(hug)= ⟨Ind,Ind⟩

Itmaybedesirabletoallowsomepredicatestocombinewithmorethanoneassortment ofargumenttypes.Thus,forexample,onemightwishtosaythatthepredicate‘believe’ cancombinewithtwoindividualsjustlike‘hug’(asin KimbelievesSam)orwithan individualanda“proposition”(asin KimbelievesthatSamistellingthetruth).Similarlythepredicate‘want’mightbebothatwo-placepredicateforindividuals(asin Kim wantsthetree)oratwo-placepredicatebetweenindividualsand“properties”(asinKim wantstoownthetree).Weshallhavemoretosayabout“propositions”and“properties” later.Fornow,wejustnotethatwewanttoallowforthepossibilitiesthatpredicatescan be polymorphic inthesensethattheremaybemorethanonesequenceoftypeswhich characterizetheargumentstheyareallowedtocombinewith.Thesequencesneednot evenbeofthesamelength(consider Kimwalked and Kimwalkedthedog).Wethus allowforthepossibilitythatthesepairsofnaturallanguageexamplescanbetreated usingthesamepolymorphicpredicate.Anotherpossibility,ofcourse,istosaythatthe Englishverbscancorrespondtodifferent(thoughrelated)predicatesintheexample pairsandnotallowthiskindofpredicatepolymorphisminthetypetheory.Wedonot takeastandonthisissuebutmerelynotethatbothpossibilitiesareavailable.Ifpredicatesaretobeconsideredpolymorphicthenthearityofapredicatecanbeconsidered tobeasetofsequencesoftypes.In(5)wegiveadefinitionofapolymorphicpredicate signature(repeatedinAppendix A3.1).

(5) A polymorphicpredicatesignature isatriple

⟨Pred, ArgIndices, Arity⟩

where:

1. Pred isaset(ofpredicates)

2. ArgIndices isaset(ofindicesforpredicatearguments,normallytypes)

3. Arity isafunctionwithdomain Pred andrangeincludedinthepowerset ofthesetoffinitesequencesofmembersof ArgIndices.

Asimpleexampleofapolymorphicpredicatesignatureisgivenin(6).

(6) a. Pred ={boy,dog,hug,walk}

b. ArgIndices ={Ind}

c. Arity isdefinedby:

Arity(boy)= {⟨Ind⟩}

Arity(dog)= {⟨Ind⟩}

Arity(hug)= {⟨Ind,Ind⟩}

Arity(walk)= {⟨Ind⟩,⟨Ind,Ind⟩}

Analternativetoourcharacterizationofpredicatesistoconsiderthemasfunctionsfrom sequencesofobjectsmatchingtheiraritytotypes.Assuchtheywouldbea dependent type,thatis,anentitywhichreturnsatypewhenprovidedwithanappropriateobject orsequenceofobjects.Wecanalsothinkofthemas typeconstructors aswillbemade clearinourdiscussionofsystemsofcomplextypesjustbelow.

A systemofcomplextypes addstoasystemofbasictypesacollectionoftypesconstructedfromasetofpredicateswiththeirarities;thatis,itaddsallthetypeswhich youcanconstructfromthepredicatesbycombiningthemwithobjectsofthetypescorrespondingtotheiraritiesaccordingtothetypesintherestofthesystem.Thesystem alsoassignsasetofobjectstoallthetypesthusconstructedfrompredicates.Manyof thesetypeswillbeassignedtheemptyset.Intuitively,ifwehaveatypehug(c,d)and therearenosituationsinwhich c hugs d thentherewillbenothingintheextensionof hug(c,d);thatis,itwillbeassignedtheemptysetinthesystemofcomplextypes.Notice thattheintensionalityofourtypesystembecomesveryimportanthere.Theremaybe manyindividualsxandyforwhichhug(x,y)isemptybutstillwewouldwanttosaythat thetypesresultingfromthecombinationof‘hug’withthevariousdifferentindividuals correspondstodifferenttypesofsituations.Theformalcharacterizationofasystemof complextypesisgivenin(7)(repeatedinAppendix A3.2).

(7) A systemofcomplextypes isaquadruple:

TYPEC = ⟨Type, BType, ⟨PType, Pred, ArgIndices, Arity⟩, ⟨A,F⟩⟩ where:

1. ⟨BType, A⟩ isasystemofbasictypes

2. BType⊆Type

3. forany T ∈ Type,if a :⟨BType,A⟩ T then a :TYPEC T

4. ⟨Pred, ArgIndices, Arity⟩ isa(polymorphic)predicatesignature