Fundamental Things

Theory andApplications ofGrounding

LOUIS DEROSSET

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Louis deRosset 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022947972

ISBN 978–0–19–881289–0

ebook ISBN 978–0–19–254222–9

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198812890.001.0001

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books Limited

Contents

Preface

1.

Grounding and Fundamentality

A New Name for an Ancient Idea

Grounding and Explanation

Grounding Explanations are Metaphysical

Fundamentality

Facts and Their Kinds

Other Entities

Theories

Some Features of Grounding

Grounding and Dependence

Structural Features

Variable Adicity

Non-monotonicity

Operationalism or Relationalism?

Propositions or Facts?

Facts or Other Entities?

Worldly or Representational?

Grounding and Conceptual Priority

Conceptual Priority and the “Logical Cases” of Grounding

Transitity and Asymmetry

Varieties of Grounding

Unity

Grounds and Causes

Skepticism

3.1

Hard Eliminativism

Motivations

Against Hard Eliminativism

Proxies for Grounding

Intuitive Unintelligibility

Soft Eliminativism

Motivations

Against Soft Eliminativism

Revolutionary Reductionism Motivations

Against Revolutionary Reductionism Is There a Generic Grounding Relation? Is There a DistinctiveGeneric Grounding Relation?

Wilson’s Heuristic

First Problem: Assessment in Easy Cases

Second Problem: Wilson’s Heuristic and Small-g Grounding Relations

The Lesson of Wilson’s Objections

Wilson’s Challenge

4. 4.1

Grounding and Reduction

Identity Reduction

Property Identification and Conceptual Analysis

Reduction among Theories and Kinds of Facts

Laws

Unity of the Sciences

Complexity

A Priority

Grounding

Chunky Facts and Their Structure

Facts and Their Structure

Identity Reduction, Real Definition, and the Irreflexivity of Grounding

Asymmetry

Multiple Realizability Arguments

The Form of Multiple Realizability Arguments

Delimiting the Class of Physical Facts

The Aristotelian Situation

Ramsey Counterparts

Less Fanciful Counterphysical Possibilities

Life vs. Fool’s Life

The Disjunctive Model and the Modal Premise

Denying the Cointensionality Constraint

Appeals to Human Frailty

Other Kinds of Reduction

Type- and Token-Identity

Functional Realization

Mechanistic Explanation

Metaphysical Truth Conditions

Conclusion

Preventing Collapse

The Collapse

Generalizations of the Collapse

Identity Reduction and the Collapse

A Way Out

Objections

PrimaFacieImplausibility

Connection

Intelligibility

Groundiness

Different ExplanandaRequire Different Explanantia

Patterns in Grounding Relations

Implausible Consequences

Alternatives

Grounding the Unreal

8

Conciliatory Irrealism

Reduction

Ground Truthmaking

Grounding the Unreal

The Elements of the Metaphysics of Ground

The Elements of the Metaphysics of Truthmaking

Ground (or Near Enough) Without Facts

Simulation Achieved

Objections

Diagnostics for Reality

Hollow Truth

Puzzles Concerning Ground and Truth

What is Metaphysical “Heft”?

Truth as Hollow Solutions

A Problem for Internality Objections

Grounds vs. Causes

Generalizations

Epistemic Versions of the Puzzles

Inheritance

Generalizations of Aristotle’s Insight

Conclusion

The Nonreductivist’s Trouble with Explanation

Standard Nonreductivism

The Determination Constraint

The Connection Problem

Objections to the Determination Constraint

Enabling Conditions

Necessitation

Complexes

8.5 8.6

Alternatives to DC Accepting the Conclusion

8.6.1

8.6.2

8.6.3

8.6.4

Bibliography Index

Deny FACT UNIQUENESS?

Deny ENTITY AUTONOMY?

Deny ENTITY DETERMINATION? Softening the Blow

Preface

I first encountered explicit theorizing about grounding when I heard Kit Fine give “The Question of Realism” as the Reichenbach Lecture at UCLA near the turn of the 21st century. I was then a graduate student working in the metaphysics of modality. A prominent idea in that literature is that modal reality is somehow second class: it is dependent on and determined by non-modal reality. This tended at the time to get characterized as the idea that modal reality somehow reduces to non-modal reality. That struck me as an overly narrow conception of what was at issue. The conception of ground Fine introduced in the lecture seemed to me a better alternative, so I was excited.

Fine’s paper was soon published as (Fine, 2001). By the late 2000s, the idea of grounding had taken off. It was developed, defended, and criticized by a number of prominent thinkers, whom another philosopher has dubbed the “grounding celebrities.” It had a brief few years as perhaps the most fashionable topic in metaphysics, if not all of academic philosophy.

This book was born of dissatisfaction with how I thought that discussion was going. It seemed to me that enthusiasts and critics alike were writing as if grounding were some exotic specimen whose existence had been disclosed to a few, lucky metaphysicians. But the idea struck me, on the contrary, as a familiar presence in essentially all of the philosophy and most of the science that I have encountered in my years since middle school. Its ubiquity, in my view, provides a rich source of examples that could be used to augment our understanding of the idea and guide our theorizing. The existing literature had, I thought, a need for these resources. There were interesting and fruitful constraints that guided ordinary

inquiry into what grounds what, and attention to those constraints sheds light on independently interesting questions. So, here I make a sustained attempt to bring these resources to bear. Though the tides of fashion have ebbed at least somewhat in the years since I began working on this project, I hope nonetheless that some of the results will have lasting utility for our collective and continuing work. The book is roughly and somewhat artificially divided in half, with the first four chapters developing the theory of grounding and the last four chapters applying that theory. Chapter 1 introduces the notion and the treatment in its terms of what I call the idea of layered structure. Chapter 2 engages some of the more abstract issues in the theory of grounding that have been important in the recent literature. Chapter 3 confronts skepticism about the idea, and Chapter 4 explores the relation between grounding and reduction.

I think of these first four chapters as drawing on a series of fairly innocuous observations to develop a rudimentary theory and an associated battery of methods. The last four chapters are more speculative. Each can be characterized as addressing a problem. Chapter 5 considers Sider’s (2011) problem concerning what grounds the grounding facts. Chapter 6 concerns the problem of reconciling grounding claims with an interesting but puzzling kind of irrealism, Chapter 7 treats the problems concerning how truth ascriptions are grounded discovered by Fine (2010a), and Chapter 8 considers a problem for accommodating a standard and plausible sort of nonreductivism. The problems get increasingly severe. In my view, Sider’s problem has a completely satisfactory solution. The solutions explored in Chapters 6 and 7 are more speculative, and I have no solution at all to offer for the problem discussed in Chapter 8.

Naturally, consideration of each of these problems has lessons for the theory of grounding. So, as I said, it is somewhat artificial to characterize the first half of the book as focused on the theory of grounding, and the second half as focused only on applications. But applying the tools developed in the first four chapters to these problems, I argue, has significant upshots for questions whose

interest was obvious before the burgeoning of the grounding literature in the years since 2001. So, it is not misleading to hold that we find, in the second half of the book, applications of the tools developed in the first half to questions outside the theory of grounding.

Readers should start with Chapter 1, which introduces the idea of grounding. I have tried to make each of the subsequent chapters self-contained, with common issues flagged and cross-referenced. So, readers should feel free to skip around as their interests suggest. The book is free of technical content. There are no logics characterized or theorems proved. Any reader with a basic understanding of logic, including some elementary modal logic, and who can understand complex expressions for properties like ‘being either red or a bachelor’ (and their regimentation using -abstracts, as in ‘ ’) has all of the necessary logical background. Some familiarity with philosophical work of the sort discussed in standard undergraduate survey courses in ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics is presupposed. So, for instance, I presume that readers can easily remember what a Gettier case is, and that they know that Kant defended a claim to the effect that what makes an action morally permissible or impermissible involves features of the maxim with which the act is performed. I expect that different readers will find the material challenging in different places. I regard Chapter 6 as the most difficult chapter, since the idea of conciliatory irrealism is among the most challenging ideas I have ever encountered. One reader has suggested, however, that Chapter 7 is harder going. In any case, I think it is fair to warn my readers that sometimes matters in the later chapters are complicated and difficult. I have tried to ensure that, where there is difficulty, it is due to the nature of the subject matter.

An earlier version of large portions of Chapter 5 was published as (deRosset, 2013a). An earlier version of large portions of Chapter 6 was published as (deRosset, 2017). Chapter 7 was published as (deRosset, 2021) and is reprinted here with only minor revisions.

This book exists in large measure thanks to the efforts of other people. Work on the manuscript was supported by a grant from the U.S.-Norway Fulbright Foundation for Educational Exchange, with additional support from Concept-Lab at the University of Oslo. I would like to thank Fatema Amijee, Louise Antony, John Bengson, Karen Bennett, Selim Berker, Phillip Bricker, David Chalmers, Andrew Cortens, Terence Cuneo, Shamik Dasgupta, Cian Dorr, Billy Dunaway, Matti Eklund, Kit Fine, Martin Glazier, Jeremy Goodman, Randall Harp. Mark Jago, Nic Jones, Zoë A. Johnson King, Dan Korman, Kathrin Koslicki, David Mark Kovacs, Stephan Krämer, Øystein Linnebo, Jon Erling Litland, Adam Lovett, Brannon McDaniel, Michaela McSweeney, Eliot Michaelson, Mark Moyer, Kate Nolfi, Gideon Rosen, Gonzalo Rodriguez-Pereyra, Rob Rupert, Noël Saenz, Jonathan Schaffer, Benjamin Schnieder, Alan Sidelle, Ted Sider, Riin Sirkel, Jack Spencer, Mack Sullivan, Tuomas Tahko, Mike Titelbaum, Kelly Trogdon, Matt Weiner, Alastair Wilson, Jessica Wilson, Keith Wilson, Jeremy Wyatt, and Justin Zylstra for extraordinarily helpful comments and questions. I would also like to thank participants in reading groups at the University of Vermont and the University of Oslo. I also owe thanks to a small army of anonymous referees for astute comments and criticism, including two referees for Oxford University Press whose care and attention were exemplary.

Versions of Chapter 3 were presented at the University of Richmond, Virginia Tech, and the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Versions of Chapter 6 were presented at the Birmingham Fundamentality Workshop, the 2014 Inland Northwest Philosophy Conference entitled “Metaphysics on the Mountain,” the Centre for the Study of Mind and Nature at the University of Oslo, the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a conference at the CUNY Graduate Center entitled “The Metaphysics and Epistemology of Grounding.” Versions of Chapter 7 were presented at a workshop on ground and normativity at the University of Texas at Austin, at Oxford University, and at New York University. The titular metaphor for that chapter was suggested by Matt Weiner, and Caley MillenPigliucci helped prepare the text. A version of Chapter 8 was

presented at Harvard University. Thanks to all of the audiences at those presentations for comments, questions, and discussion. This book is materially improved as a result.

Thanks to Janina Cuneo for help on revisions of the manuscript. I also owe thanks to Peter Momtchiloff at Oxford University Press for his encouragement and his apparently boundless patience.

Finally, I would like to thank my spouse, Mary Beth McNulty, for her love and support. This book is dedicated to her, and to our children.

Grounding and Fundamentality

1.1 A New Name for an Ancient Idea

This book is a study of an ancient idea, that some bits of reality may “rest on” others, in a sense badly in need of explanation. The metaphor of one thing’s “resting on” another strongly suggests the figure of a structure in which some things support others. The ancient idea has a new name, “grounding,” which appeals to this figure.

There is a relatively young literature that uses this new name to limn the features of the phenomenon that answers to it, but the idea is almost certainly as old as theoretical inquiry itself.1 Most areas of philosophical inquiry regularly truck in the idea. Ethicists want to know, among other things, what makes good things good, virtuous people virtuous, and right actions right. An ethicist is concerned, for instance, to discover what made Oswald’s assassination of Kennedy morally wrong. A virtue theorist might suggest that what made it wrong is that it is not the sort of thing a virtuous person would do. A Kantian might suggest instead that it is wrong in virtue of having proceeded from a maxim which could not be willed as a universal law. A consequentialist might suggest instead that it is wrong in virtue of having worse consequences than some alternative— presumably, not assassinating Kennedy—available to Oswald. Importantly, all three might agree that a virtuous person wouldn’t do it, that Oswald’s maxim was not universalizable, and that the act was

not optimific. The dispute does not center on whether the proposed grounds are in fact the case. Instead, it centers on whether the wrongness of the act depends on and is determined by one or another of those proposed grounds. The Kantian denies, and the consequentialist affirms, that the act’s wrongness “rests on” the nature of its consequences. Similarly, reliabilists and virtue epistemologists might agree that my belief that I have hands was formed by a reliable belief-forming mechanism and manifests my epistemic skill, while disagreeing about which of those facts makes my belief justified. Similarly, metaphysicians of modality dispute what makes Hilary Clinton a possible U.S. president.

So, philosophers in these disparate areas have something in common. They are all wondering which facts are grounded in which. The extent of the unity of these fields should not be exaggerated. They are large and diverse, and there are significant differences among them. Also, there are, of course, many other questions addressed by investigators in these areas which do not appear to concern what grounds what. But they share at least this much in common: sometimes they are concerned to dispute grounding claims, with the aim of discovering what grounds what.

It would be a mistake, however, to think that questions concerning grounding are confined to philosophy. Physical chemists can tell us, in a general way, what makes the fluid in one system hotter than the fluid in another, and they can tell us that a given hydroxide ion has unit negative charge in virtue of the charges of its constituent particles. I once heard a theoretical physicist characterize her research on the radio as an investigation into what makes gravity so weak. In all these cases, these researchers, philosophers and scientists alike, are asking questions or making claims about what certain circumstances “rest on” in the sense at issue.

Presumably almost none of these theorists, until very recently at least, were using the new terminology, ‘grounds’, to express their hypotheses. As the examples noted above illustrate, one natural way to express the idea deploys the notion of makingsomething F, for some feature F. Ethicists want to know what makes certain acts

wrong; epistemologists, what makes certain beliefs justified; scientists, what makes ions negatively charged and gravity weak. Another natural expression of the idea, also used above, deploys the idea of one thing’s being the case in virtue of another’s being the case. These are my favored idioms for expressing the idea of grounding. There are other idioms. Sometimes people wonder about the grounds for a certain phenomenon— necessity or normativity by asking after its “source” (Korsgaard, 1996), (Cameron, 2010a). Others talk of “locating” the phenomena to be grounded (Jackson, 1998). Sometimes people use ‘reduces’ and its cognates to express the idea (Fine, 2001). None of these locutions is perfect. The ‘rests on’, ‘source’, and ‘locating’ locutions are clearly metaphorical. As we shall see (Chapter 4), ‘reduction’ can be used to indicate a very different idea. Even my favorites, ‘making’ and ‘in virtue of’ have well-entrenched uses that do not express grounding. I can make my desk black by painting it, and I can summarize the results of my efforts by saying that my desk is black in virtue of my having painted it. But if a metaphysician of color wants to know what makes the desk black, or what it is in virtue of which the desk is black, her question is not answered, even in part, by appeal to my brushwork. So, the ‘making’ idiom can be used to indicate instances of causation that are not also grounding.2

As with many important philosophical ideas, there seems to be no natural language expression which exactly captures the idea. I trust nonetheless that you have enough familiarity with the metaphysical, ethical, epistemological, and scientific investigations I have mentioned above to have some idea, however dim, of what’s under discussion. If you have participated in any of these debates, you have proposed or objected to arguments for or against the grounding claims which characterize them. So, you have enough of an idea of what’s under discussion to assess at least some grounding claims.

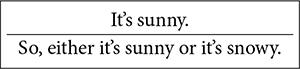

In fact, it is easy to recognize certain manifestly plausible grounding claims. The weather today is sunny. So, it’s either sunny or snowy. It is overwhelmingly plausible to think that these two

circumstances are related: the weather is either sunny or snowy in virtue of being sunny. It is overwhelmingly implausible to think that it is sunny in virtue of being either sunny or snowy. Similarly, though it is plausible to think that someone is a philosopher at least partly in virtue of the fact that you are philosopher, it is overwhelmingly implausible to think that what makes you a philosopher is that someone is. Or again, the desk at which I write is both brown and wooden. It is overwhelmingly plausible to think that it is both brown and wooden partly in virtue of being brown, and overwhelmingly implausible to think that it is brown even partly in virtue of being both brown and wooden.3 Aristotle held that the statement that there are human beings is true in virtue of there being human beings.4 This strikes me as powerfully plausible, though some would deny it.5 It is even more plausible to deny the converse grounding claim, that there are humans in virtue of the truth of the statement. So, we have a large class of grounding claims and denials of grounding claims that enjoy a high degree of plausibility.

Our appreciation of the plausibility of these claims manifests our grasp of the notion of grounding. The claims may also guide our theorizing about grounding, even if we acknowledge, as we must, that, despite their plausibility, any or all of them are defeasible. They may guide us even if the upshot of our investigations is that there is no such thing as grounding. The upshot of our investigations into the supposed wonders of the invisible world is that there are no witches. Presumably, this eliminative result proceeds in part from the fact that nothing answers to the conception that Cotton Mather and his contemporaries had of what witches were supposed to be. Similarly, the upshot of our chemical investigations is that there is no such thing as phlogiston. Presumably, this is partly because the conception that theorists in the pre-history of chemistry had of phlogiston was that it was the substance whose loss explains combustion, and no substance fits that conception. There are several important arguments in the grounding literature for being skeptical that anything answers to our conception of grounding. We will be

confronting such skeptics later (Chapter 3). For now, our task is to understand what it is that they urge us to be skeptical about.

Grant, then, that we have some idea of what grounding is or is supposed to be. Why should we want to theorize about it? Just as scientists can use the notion of property or quantity without being in possession of a theory of properties or of quantities, so, one might think, philosophers and scientists can use the notion of grounding without being in possession of a theory of the phenomenon. Why, then, should we study grounding itself, rather than simply getting on with our philosophical and scientific investigations concerning what grounds what? Presumably, since you are reading, you are not immune to the intrinsic interest of an abstract theoretical investigation of this sort. But there is another source of interest. The theory of grounding has important upshots for debates which have antecedent interest. If you are interested in the nature of truth, the mind-body problem, or the ways in which even true theories might fail to accurately reflect the structure of representation-independent reality, then you should also be interested in the theory of grounding. For that theory reveals new vistas on those questions. It opens the way for clear expression of new positions, solves some old problems, and enables the articulation of some new ones. Theorizing about grounding is theoretically fruitful, and that is a reason to pursue it. At least, so I will argue in this book.

In the remainder of this chapter, I will describe the raw materials for a theory of grounding and outline a key application of the theory. Briefly, the key application is to make sense of the compelling but somewhat woolly idea that there is a layered structure of dependence and determination, with higher-level entities “resting on” lower-level entities. Naturally, we understand the idea of one thing’s “resting on” another in terms of grounding. The remainder of the book is intended as an extended demonstration that such an understanding is theoretically fruitful.

1.2

Grounding and Explanation

We start by tallying a number of resources which are available to inform our theorizing about grounding. These will be the raw materials we use to develop the theory of grounding. We have already encountered two such resources. First, we are familiar with a number of investigations concerning what grounds what. Some of those investigations have made some impressive progress, giving us some data to work with. Moreover, we are familiar in practice with features of those investigations, providing a rich source of insight into the constraints on grounding. Second, we have a large class of antecedently plausible claims about what obtains in virtue of what. We understand those claims well enough to appreciate their plausibility, and they may also offer us some insight into the features of grounding.

A third source of understanding and insight has not yet been mentioned: there is a link between grounding claims and explanations of a certain sort. Evidently, when ethicists attempt to say what made Oswald’s assassination of Kennedy wrong, they are in some sense explaining its wrongness. The same goes for the other cases I have mentioned. When Aristotle claims that the truth of the statement that there are human beings is grounded in the existence of human beings, he expresses himself using explanatory locutions:

[T]here being a man reciprocates as to implication of existence with the true statement about it: if there is a man, the statement whereby we say that there is a man is true, and reciprocally—since if the statement whereby we say that there is a man is true, there is a man. And whereas the true statement is in no way the cause of the actual thing’s existence, the actual thing does seem in some way the cause of the statement’s being true: it is because the actual thing exists or does not that the statement is called true or false.

(Aristotle, Categories, 14b14–22, trans. J.L. Ackrill)

Grounding and explanation go together. Some theorists of grounding have even identified grounding and what they call “metaphysical

What is the link between grounding and explanation? Answering this question is complicated by the fact that, even in the philosophical literature, ‘explanation’ and its cognates are used to indicate a wide variety of things. In particular, ‘explanation’ may be used for a linguistic item, like a sentence, utterance, speech act, etc. It may instead be something more abstract, like the proposition expressed by such sentences. In either of these cases, ‘explanation’ may be used either for the entire explanatory sentence, claim, etc., or for the sentence, claim, etc., that occupies the explanansposition. For instance, in one sense of ‘explanation’,

(1.1)

the desk is black because I painted it black is an explanation for the blackness of the desk, whereas in another

(1.2)

I painted the desk black is. Moreover, sticking once more to the use of ‘explanation’ for linguistic items, there is a use of ‘explanation’ as a success term; on this use

(1.3) explanation”; see especially (Fine, 2001), (Rosen, 2010), (Dasgupta, 2014b), and (Litland, 2015).

I painted the desk black because it is black

is not an explanation of my painting the desk black, since it is false. On another use of ‘explanation’, the term does not imply success; a consequentialist may discuss “the Kantian’s explanation” of the wrongness of a certain act without thereby implying the truth of the Kantian view. There are also uses of ‘explanation’ and its cognates to indicate the circumstances, facts, events, or states of affairs reported by sentences, propositions, etc., rather than those sentences, propositions, etc., themselves. So, for instance, it is natural to say that my brushwork—not a sentence, but the periodic

dips of the brush into the paint, followed by swipes across the surface of the desk—explains the desk’s blackness.

All of this variation is independent of the widely acknowledged fact that there are many different kinds of explanation. Any attempt at a complete inventory of the different kinds of explanation would be controversial. At a minimum, however, there seem to be causal explanations, rationalizing explanations, and the sort of explanations with which we are concerned. These three kinds are exemplified, respectively, by the following sentences:

(1.4)

The match lit because it was struck.

Joe majored in physics because it would impress potential employers.

This ion has unit negative charge because it has 18 electrons, 17 protons, and no other charged leptons or bosons.

So, we can use ‘explanation’ to pick out causes, reasons, or grounds for something; sentences stating those causes, reasons, or grounds; sentences stating merely putative causes, reasons, or grounds; sentences stating that those things are causes, reasons, or grounds; the facts or circumstances stated by those sentences; and, similarly, for propositions; etc.

This multiplicity of uses has the potential to confuse the discussion. I propose to deal with it by stipulation: when I use ‘explanation’ and its cognates, I have in mind a certain class of sentences: those which deploy recognizably explanatory locutions. For example,

(1.5) (1.6) (1.7)

‘There are human beings’ is true because there are human beings

is an explanation, in the sense I intend here. What’s more, I stipulate that my use of those explanatory locutions indicates

grounding, rather than rationalization, causation, or some other phenomenon picked out by uses of explanatory locutions. Thus, the sentences on which we will focus are groundingexplanations.

This stipulation immediately takes off the table the identification of grounding itself with any sort of explanation. Explanations are sentences, and presumably the phenomenon in question is not to be identified with any class of sentences which report its instances. Of course, this is not some deep discovery about the nature of grounding that contradicts what several authors have said. It is, instead, the immediate upshot of my stipulation about how I am using “explanation” and its ilk, and my stipulation does not govern other authors’ usage. Nevertheless, so long as we have the vocabulary to state the relevant circumstances, whenever we find grounding we will also find a true grounding explanation which reports it. In this sense, grounding and true explanations are found together.6

So, true grounding explanations typically accompany grounding. What’s more, I will assume a highly plausible view about the nature of grounding explanation. On this assumption, a grounding explanation is true if and only if there is an argument whose conclusion is the explanandum, whose premises are the explanantia, and in which the series of inferences from explanantia to explanandum follows the order of dependence and determination among the facts or circumstances reported by those sentences.7 I will summarize this claim by saying that every grounding explanation is accompaniedby an argument of the relevant sort.

Why think this assumption is true? One particularly nice, particularly convincing way to answer the question, “In virtue of what is it the case that P?” is to cite some truths, and then trace an argument from those truths to P, where the steps in the argument trace the order of dependence and determination. So, for instance, consider (it’s either sunny or snowy) in virtue of the fact that it’s sunny.

(1.8)

(1.8) is true. This explanation is accompanied by the explanatory argument (1.9)

Similarly, one way to tell that

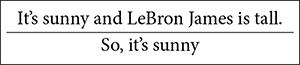

(1.10)

It’s sunny in virtue of the fact that it’s sunny and LeBron James is tall is not a true grounding explanation is to note that (1.11)

while valid, is not an explanatory inference. Its inference does not trace any relations of dependence and determination. In fact, in this case the direction of dependence and determination is exactly opposite the direction of inference.

When we offer answers to questions that call for grounding explanations, we construct and criticize arguments of this sort; we train our students to explain things by constructing such arguments, and we identify gaps in their accounts by finding gaps in the corresponding arguments. The activity of asserting and defending explanations involves the production of putatively explanatory arguments. This makes the assumption that true grounding explanations are accompanied by such arguments highly plausible, since that assumption is manifest in our practices of constructing, asserting, and defending explanations.

My assumption is evidently shared with the deductive-nomological model of explanation (Hempel and Oppenheim, 1948). That model is nowadays recognized to face severe problems (Woodward, 2019, §2). I am not, however, signing on to the deductive-nomological

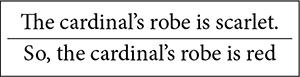

account in detail; in particular, I do not require that the arguments in question be logicallyvalid, nor that they be nomological—laws need not play any special role. To illustrate, it is standard in the grounding literature to claim that ‘the cardinal’s robe is red in virtue of the fact that it is scarlet’ is true. But the corresponding argument (1.12) is not logically valid.8 At least, it is not valid in the sort of first-order logic we teach in introductory logic courses.9 Also, no law of nature plays any special role in the explanatory argument (1.9).10 So, one way of summarizing the import of my assumption is that I endorse the deductive-nomological account of explanation, except to the extent that it is deductive or nomological.

Proponents of the deductive-nomological account committed themselves to the assumption that scientific explanations are accompanied by arguments. This is not a source of trouble for the view. Instead, the view faces trouble because it attempts to do without the admittedly obscure proviso that the course of the accompanying argument must trace the order of dependence and determination. Consider a classic objection to the deductivenomological account. The case involves a flagpole which casts a shadow on the ground. The shadow projected by the flagpole has length lbecause the flagpole has height hand the sun is at angle θ; it is not the case that the flagpole has height hbecause the shadow has length l and the sun is at angle θ.11 This is a problem for the deductive-nomological account of scientific explanation, since there are sound deductive arguments (appealing to the laws of optics and trigonometry) going in both directions. Only one of those arguments, however, traces the direction of dependence and determination (which is in this case causal). So, the classical problems for the deductive-nomological account underscore my assumption that true explanations are accompanied by arguments that proceed in the

correct direction, since that is precisely the requirement that appears to fail in the flagpole case. Thus, the classic objections to the deductive-nomological account of scientific explanation actually support the assumption that true grounding explanations are accompanied by arguments of the relevant sort.

The proviso that the inferences trace the order of dependence and determination is, as I have emphasized, obscure. It would be nice to have some less obscure replacement. Unfortunately, I know of no helpful analysis of the distinction between arguments that trace the order of dependence and determination and those that do not. The examples show, nonetheless, that, in at least some cases, we have a fairly firm grip on the difference. Our grip does not consist exclusively in our grip on the truth of the corresponding grounding explanations, for being accompanied by an explanatory argument is only a necessary condition for a good grounding explanation. Suppose it’s neither sunny nor snowy. Then (1.8) is not true. Nevertheless, it’s easy to tell that the argument accompanying it contains only explanatory inferences. That argument has what it takes to accompany a true grounding explanation, so long as the facts cooperate. Similarly, you don’t need a weatherman to know that (1.10) cannot be right. In general, some, but not all, inferences have what it takes to trace the direction of the sort of dependence and determination indicated by ‘in virtue of’, so long as the other necessary conditions for such explanations are in place. Clearly, one such necessary condition is engendered by the factivity of grounding explanation: the inferences of any accompanying argument must proceed from true premises to a true conclusion. I will argue in later chapters that there are others.12

I will call an argument accompanying a grounding explanation an explanatory story. An explanatory story is step-wisegood (or good, for short) iff each claim it contains is possibly true,13 and each of its inferences is explanatory. So, we allow that the argument above involving conjunction elimination is an explanatory story, but deny that it is a good one.14

An explanatory story whose conclusion is ϕ is an explanatory story for ϕ. Thus, true grounding explanations whose explanandum is ϕare accompanied by good explanatory stories for ϕ. Allowing any old argument to count as an explanatory story is mostly a matter of bookkeeping. On my stipulation, ‘explanation’ is not a success term, but instead applies to any sentence that uses ‘in virtue of’, ‘because’, or related locutions to indicate grounding. Many such explanations will be false, some laughably so. It is easiest to treat them systematically if we have a term for accompanying arguments that covers both those arguments that succeed in tracing the order of dependence and determination and those that fail, sometimes laughably. So, just as my use of ‘explanation’ covers sentences that are laughably false, so my use of ‘explanatory story’ covers accompanying arguments that are laughably bad at tracing the order of dependence and determination.15

Here, then, are our raw materials for theorizing about grounding. First, we can recognize a battery of explanatory theoretical projects, across a wide variety of fields, that each concern what makes things a certain way or what it is in virtue of which they are that way. Second, we have a large class of overwhelmingly plausible claims about what obtains in virtue of what. Third, we are familiar in practice with the constraints governing such explanations, since we liberally indulge in constructing and criticizing them, at least in our professional lives. Finally, a large element of constructing and criticizing explanations involves scrutiny of the features of accompanying arguments. This may not sound like much, but it turns out to be a surprisingly rich starting point for theorizing. Indeed, all of the theory and applications of grounding discussed in this book are built in large measure from these simple and straightforward materials.

1.3 Grounding Explanations are Metaphysical

As we have seen, grounding enthusiasts standardly link grounding and what they call “metaphysical explanation,” and some even identify grounding with this sort of explanation. It is not entirely clear what distinction is marked by their use of ‘metaphysical’ in this context. There is the exegetical question of what any particular theorist may have had in mind by linking grounding with metaphysical explanation, as opposed to some other kind. I don’t propose to engage that question; those theorists can speak for themselves.

But it may be useful and prevent confusion if we start by noting a way in which grounding explanation is not metaphysical. Grounding explanations are not proprietary to theorizing on the sorts of topics that one finds on syllabi for courses recognized by experts as courses in metaphysics. One does not find them exclusively, or even mainly, in journal articles by authors who list “metaphysics” as their area of specialization. Instead, as I have emphasized, one encounters grounding explanations in almost every area of philosophical and scientific inquiry.16 Contrast this with the notion, for instance, of a hyperintensional linguistic context. (Roughly, an expression e occurs in a hyperintensional linguistic context in a sentence Φ(e) iff the truth value of Φ(f) and Φ(f*) sometimes differ even though f and f* are necessarily co-extensive.) That’s not a notion one ever encounters outside of metaphysics. Hyperintensionality and claims that attribute hyperintensionality, then, are metaphysical in what we might call the disciplinarysense. Grounding explanations are not metaphysical in the disciplinary sense.

In this respect, grounding is like the notion of necessity that is studied so intensely in modal metaphysics. Though this notion is often called “metaphysical necessity,” it appears to be used by nonmetaphysicians more or less constantly. Instead, what is marked by calling this sort of necessity metaphysical is that the necessity of, say, a claim is not a matter of what sort of access any particular knower or speaker has to the claim or its truth.17 The point of calling grounding explanations “metaphysical” is the same: they concern

the access-independent natures of the things under discussion, rather than our knowledge of them, attitudes toward them, or words for them.

An example may help illustrate the point. Recall that physical chemists can tell us, in a general way, what makes the fluid in one system hotter than the fluid in another. A physical chemist can tell us, for instance, that the fluid in system Ais hotter than the fluid in system Bin virtue of system Acontaining exactly particles a0, a1, …, ai, a0’s having kinetic energy of n0 joules, a1’s having kinetic energy of n1 joules, …, together with something similar concerning the kinetic energy of the particles in system B. (Of course, the physical chemist cannot specify the facts to which she alludes: she does not know all of them and could not survive long enough to catalog them.) This concerns a certain feature of the two systems, rather than anyone’s knowledge of or access to that feature of the system. If we wanted to talk about our knowledge of the fact that Ais hotter than B, presumably we would say something about thermometers or our sensations. No actual person’s access to this feature of the two systems is appropriately characterized by a catalog of the kinetic energies of the particular particles in question. Similarly, it would be implausible to suggest that the physical chemist’s claim characterizes the linguistic meaning of the word ‘hotter’, or any other expression, at least insofar as a specification of linguistic meaning articulates information that must be somehow internalized in order to be counted as a competent user of the word. What we have been told is something about the representation- and knower-independent natures of those two systems.

A certain stripe of metaphysical idealist might insist that what the physical chemist tells us does, ultimately, concern someone’s representations. Alternatively, perhaps someone might think that grounding explanations, despite appearances, say something about our access to the circumstances reported by their explananda, or some semantic feature of the expressions they contain. Nothing in the example shows these views to be incorrect. If they are correct, however, then plausibility requires that the views in question provide

some resources to mark the distinction between claims that, on their face, concern the nature and features of the thermodynamic systems, and claims that, on their face, concern our access to those features. That is the distinction I intend to mark by saying that grounding explanations are metaphysical.

In fact, the distinction we need is not most clearly put using the bare attributive adjectives like ‘metaphysical’, ‘epistemic’, and ‘semantic’. For the very same distinction shows up with respect to subject matters that are themselves clearly epistemic or semantic. So, for instance, I have suggested that those epistemologists who ask what it is in virtue of which I am justified in believing that I have hands are asking after the grounds of such justification. It would be clearly misleading to call this investigation “metaphysical,” in a way that precludes its being epistemological. A less misleading way to put the point is that, for a given subject matter X, one may investigate, on the one hand, X’s access-independent nature and features; and, on the other, the nature and features of our access to X, including how we represent X and how we gain knowledge or justified beliefs about X. The former we may mark out as “the metaphysics of X,” and the latter as “the epistemology or semantics of X.” So, the epistemologist’s investigation is of the metaphysics of justification, as opposed, say, to its epistemology. The investigation is into the metaphysics of what is a recognizably epistemic subject matter. One may also inquire into the epistemology of a metaphysical subject matter, such as metaphysical necessity (Gendler and Hawthorne, 2002). As the examples suggest, one should expect that in a given case the line separating the metaphysics of a given subject matter from its epistemology may be neither sharp nor easy to draw. Addressing oneself to a question of the former sort may quickly lead one into questions of the latter, and vice versa; and it will sometimes be difficult to tell which side of the line one is treading.

Appreciating these subtleties allows us to forestall an objection one sometimes hears to the utility of grounding in metaphysics. The objection is that explanation is an epistemic or linguistic matter,