Preface

Marcos Nadal and Oshin Vartanian

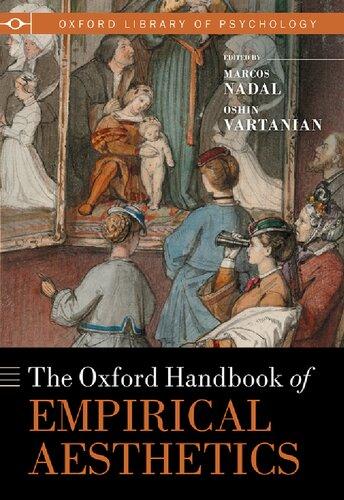

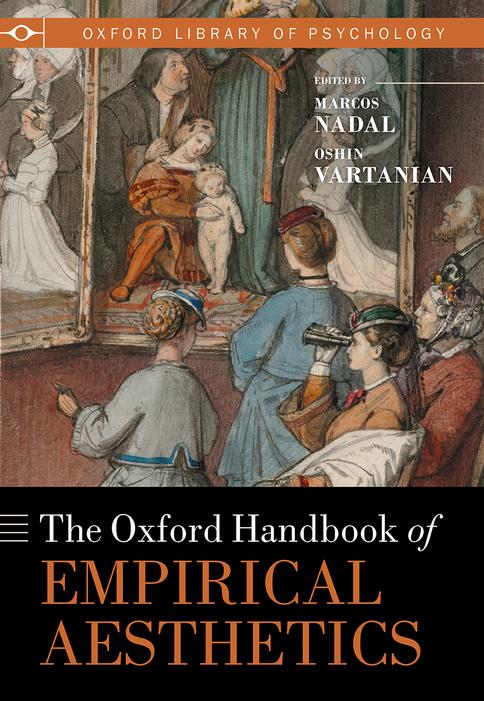

Te Madonna des Bürgermeisters Jacob Meyer zum Hasen, painted by Hans Holbein the Younger in 1526, sold for about $75 million on July 12, 2011, becoming Germany’s most expensive artwork at the time (Gropp, 2011). Not only is it regarded among the greatest German Renaissance paintings, the Madonna sparked one of the fercest and most consequential controversies in art history, and motivated Gustav Teodor Fechner to use empirical methods to study the appreciation of art. In doing so, he founded empirical aesthetics.

In 1743, the Dresden Gemäldegalerie acquired Hans Holbein’s Madonna des Bürgermeisters Jacob Meyer zum Hasen. Tis was no small addition to its collection for, at the time, it was considered the greatest painting in German art, equal to Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. It must have come as a shock when, in 1821, a second version surfaced in a private collection in Darmstadt. Te question of which version was the authentic Holbein, and which the copy, quickly became a national controversy. What began as a dispute among academics soon fared into a full-blown political afair, entangled with ideological passions (Bader, 2018b). Artists and academic art historians competed for the authority to decide on the works’ authenticity. Each side rolled out countless essays and pamphlets, printed and distributed reproductions of the paintings accompanied by analyses, arguments, and counterarguments, and spoke at conferences and exhibitions.

Fechner had been interested in the Holbein Madonna controversy at least since shortly afer publishing his Elements of Psychophysics (Fechner, 1860). He compiled, presented, and discussed the history of the confict and the two sides to it (Fechner, 1871a), and he plunged into it himself with several iconographic analyses (Fechner, 1866a-b, 1868, 1870a-b). In his opinion, both were authentic paintings by Holbein, but they expressed two diferent meanings. He thought that Holbein painted the Darmstadt version frst, and intended it for a chapel, and the Dresden version later, and intended it for the family home (Fechner, 1870a). Fechner concluded that the Dresden version was a votive work, and that the sick-looking infant was an amalgamation of the Christ Child and the donor’s ill child (Fechner, 1866b). Later, he speculated that the oldest woman in the painting was Meyer’s deceased frst wife, and that the fgure of the Madonna was the portrait of one of Meyer’s deceased daughters carrying her sick son (Fechner, 1868).

Te way to settle the confict, it was fnally agreed, was to exhibit the two paintings together. So, in 1869, the plans began for a Holbein retrospective exhibition that would feature, for the frst time ever, both versions of the Madonna side by side. Te exhibition had to be postponed, however, because of the Franco-Prussian war (July 19, 1870 – January 28, 1871). Te exhibition had been on Fechner’s mind while writing his monograph On Experimental Aesthetics, published in early 1871. Fechner (1871b) devoted much of it to arguing for the use of empirical methods in the study of aesthetics. He made his point mainly in reference to the pleasure of simple forms. But he also believed that the methods of empirical aesthetics could be used to study art, especially in the case of comparable artworks that have led to unresolved disputes among connoisseurs. He explicitly mentioned the two versions of Holbein’s Madonna as the sort of case to which his new methods could be applied. He expected that the joint exhibition would add fuel to the confict about authenticity without necessarily settling it. His experimental aesthetics, however, could answer a diferent, more fertile, question: which of the two versions is more preferred aesthetically by people in general, or by experts vs. laypeople, or by men vs. women? (Fechner, 1871b).

Finally, the peace treaty was signed in May 1871, and the plans for the exhibition moved forward. It took place from August 15 to October 15, 1871, in Dresden’s recently built Prinzen Pavillion. By the time’s standards, it was massive. On display were over 500 items, including paintings, woodcuts, drawings, and photographs, lent from over 60 museums, galleries, and private collections from over 40 European cities. It was the frst time masterpieces had been transported across frontiers for an exhibition on such a scale; the frst time an art exhibition had been promoted by art history academics, and not aristocrats, nobility, governments, or artist associations (Haskell, 2000); and the frst time the paintings were seen side by side. Alfred Richard Diether, artist and teacher at the School of Arts and Crafs, captured the interest of the exhibition’s visitors for the Madonnas in the pencil and watercolor image on the cover of this book. Te exhibition catalogue included a bibliography of over 70 publications on the controversy compiled by Fechner (Bader, 2018b), showing just how absorbed in the controversy he had become.

Te exhibition committee allowed Fechner to conduct the research on the visitors’ preferences he had been planning for a year. In the hall where the two paintings were exhibited, he placed an announcement of his study, a table and necessary writing materials, the instructions for participants, and a booklet with space for the visitors to write their answers. Te scene, sketched by the renowned German painter Adolph Menzel in his pocketbook, as “Plebiscite table” (Figure 1), was certainly an unusual one to see at a museum. Te art historians at the exhibition dismissed Fechner’s study, for the issue of aesthetic value could only confound the issue of authenticity (Bätschmann, 1996). In an analysis of the role that the Holbein exhibition at Dresden played in the forging of art history as an academic discipline, Bader (2018a) recounts the skeptical remarks of one of the most eminent Holbein scholars: “Of to one side, on a writing desk, can be found a pen, a large book, and a placard above it. Professor Fechner, the

highly-regarded physicist in Leipzig ( . . ) intends to enable a decision between the two pictures on the basis of universal sufrage” (Bader, 2018a, p. 7).

Te instructions asked the visitors to state which of the two Madonnas made such an appealing and positive impression as to grant it a place in their room for constant or repeated contemplation. Fechner asked them to disregard the artworks’ deterioration caused by the darkening varnish and other conservation defects. Te visitors were also asked to write their name, title, position, and place of residence, and had space to make open remarks about the comparison and the reasons for their responses (Fechner, 1872).

Fechner’s analysis of the responses showed that the visitors generally preferred the Darmstadt Madonna. But he was, nevertheless, disappointed with the outcome of the study. Of the 11,842 visitors to the exhibition, only 113 answered his survey, and many of them clearly did not understand the goal of the study or the instructions. He devoted much of his report to outlining the improvements to the methods and instructions that were required for similar studies in the future (Fechner, 1872). On top of this, art-historical research on the two paintings later proved that Fechner’s iconographic analyses were wrong. Te Darmstadt Madonna was the only authentic Holbein and the Dresden Madonna was a copy of the original, painted over a century afer the original (1635/1637) by Bartholomäus Sarburgh (Bader, 2018b).

Fechner’s disappointing experiment and his incorrect iconographic analyses of the Madonnas should not overshadow the magnitude of his achievements in 1871. First, by fnding value in the public’s reception and appreciation of art, he broke with the tradition that considered that the only legitimate value of art could be set by experts and academics. Second, he showed that understanding the way laypeople appreciate art was worthy of scientifc study, and that such a study should and could be pursued with empirical methods. Tird, he was the frst to collect data on the aesthetic appreciation of art from over 100 people, to use statistical techniques to determine the aesthetic value of artworks for the whole sample, to study the impact of individual variables, such as sex and expertise, and to study aesthetic appreciation in a public space (Leder, 2005). So, it was at the greatest art exhibition of his time, absorbed in the most resounding and longlasting dispute on an artwork’s authenticity, in the presence of a masterpiece of German art, and amid skepticism, misunderstanding, and disappointment, that Fechner sowed the seeds of the new feld of empirical aesthetics.

One hundred and ffy years have passed since the Dresden exhibition, and empirical aesthetics has come a long way. Te frst steps were uncertain and, early on, the prospects were not very encouraging at all. Titchener (1910) saw very little progress in empirical aesthetics in his survey of the major advances in psychology between 1900 and 1910, and wrote that “No doubt, the time is still distant, if indeed it is fated to arrive at all, when experimental aesthetics shall bear to a System der Aesthetik the relation that experimental now sustains to systematic psychology” (Titchener, 1910, p. 419). In contrast, he reported a resurgence and extension of psychophysics during the very same period (Titchener, 1910). Psychologists were still conducting all manner of experiments to probe the efects of diferential increments on sensation 50 years afer Fechner’s (1860) Psychophysics, but

they had only conducted a handful of studies on aesthetic appreciation, mostly on the efects of the proportions of simple geometrical forms, 34 years afer Fechner’s (1876) Aesthetics. Psychologists’ interest in the two felds founded by Fechner could hardly have been more unalike. But why?

Te reason, in Santayana’s (1896) words, was that:

Te moderns, also, even within the feld of psychology, have studied frst the function of perception and the theory of knowledge, by which we seem to be informed about external things; they have in comparison neglected the exclusively subjective and human department of imagination and emotion. We have still to recognize in practice the truth that from these despised feelings of ours the great world of perception derives all its value, if not also its existence.

(Santayana, 1896, p. 3)

So, psychologists preferred to study the scaling of sensation (psychophysics) because they believed it refected objective facts about the world, rather than the value of sensation (aesthetics) because they believed it refected only the feelings of the observer.

However, with functionalist psychology, the focus of inquiry began shifing from the mechanisms of sensation to the functions of sensation. From the point of view of functionalism, psychophysics’ study of valueless sensation made little sense. Organisms do not sense the world for the mere point of determining the intensity of stimulation. Tey sense it to value the options it ofers, and to determine the most advantageous course of action. Tere is no sensing for the sake of sensing. Psychologists, and also neuroscientists, became more interested in sensory values, in the role that pleasantness and unpleasantness play in the adaptation of individuals and species to their environment, and began studying things like reward value and motivation.

Following the trail of new fndings and new methods of psychology and neuroscience, in the past century empirical aesthetics has amassed a wealth of knowledge on the psychological and neurobiological process involved in aesthetic valuation: liking, beauty, preference, attractiveness, and so on. Most research has traditionally focused on the visual aesthetics of fgures, shapes, and paintings, or on the auditory aesthetics of music. But the past 20 years have witnessed a surge in empirical studies on the aesthetics of language and poetry, of movement and dance, of interior and exterior architecture, of design and consumer products, and of the presentation of food on dishes.

Empirical aesthetics is thriving like never before, expanding at a fast pace and diversifying in many directions. We felt the time was right for a comprehensive and balanced handbook. We believe the feld will beneft greatly from a single source that takes stock of the feld; that brings together and organizes current knowledge on a diversity of topics, and uses it as a springboard for imagining its future. Our intention was to produce a handbook that can be used both as an aid for teaching the next generation of empirical aestheticians and as a tool for research.

We have grouped the chapters into seven broad sections. Te reason is purely organizational, not because we believe that these represent separate issues. In fact, they refect

the inseparable components of empirical aesthetics: an object that is valued, a person that does the valuing, and a context in which the valuation takes place. Te eight chapters in Section 1 provide the historical, conceptual, biological, and evolutionary foundations of empirical aesthetics. Section 2 includes nine chapters on the basic methods of empirical aesthetics, from the historiometric to noninvasive brain stimulation. Te seven chapters in Section 3 focus on the object features that have traditionally been the main focus of empirical aesthetics. Section 4 includes eight chapters on the aesthetic appreciation of diferent art forms, including music, dance, architecture, flm, poetry, and narrative. Te six chapters in Section 5 turn inwards to the person, and examine the role of cognition, personality, age, expertise, aesthetic sensitivity, and cultural background in aesthetic appreciation. Section 6 includes fve chapters that focus on the context of aesthetic experience, from laboratories to everyday situations, and to museums. Finally, Section 7 incudes three chapters on the application of empirical aesthetics to design, consumer products, and dining.

Figure 1. Adolph Menzel, Holbein-Ausstellung, Plebiscit-Tisch, Dresden. Ident. Nr. SZ Menzel Skb.36, S.59/60 © Photo: Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Fotograf/in: Wolfram Büttner. Reproduced with permission.

Te editors of this volume would like to express their deepest gratitude to the authors for the time, diligence, and care they have put into each of the chapters that make up this book. Contributions to handbooks are not valued nearly enough by academic performance metrics. We would also like to thank Charlotte Holloway, Laura Heston, and Martin Baum at Oxford University Press, whose commitment, guidance, and support from beginning to end made this handbook a reality.

References

Bader, L. (2018a). Artists versus art historians? Conficting interpretations in the Holbein controversy. Journal of Art Historiography, 19, 1–23.

Bader, L. (2018b). Te Holbein exhibition of 1871—an iconic turning point for art history. In M. W. Gahtan & D. Pegazzano (Eds.), Monographic exhibitions and the history of art (pp. 129–142). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bätschmann, O. (1996). Der Holbein-Streit: eine Krise der Kunstgeschichte. Jahrbuch Der Berliner Museen, 38, 87–100.

Fechner, G. T. (1860). Elemente der Psychophysik. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.

Fechner, G. T. (1866a). Die historischen Quellen und Verhandlungen über die Holbein’sche Madonna: Monographisch zusammengestellt und discutirt. Archiv Für Die Zeichnenden Künste, 12, 193–266.

Fechner, G. T. (1866b). Vorbesprechung uber die Dentungsfrage der Holbein’schen Madonna mit Rucksicht auf die Handzeiclmung Nr. 65 des Baseler Museum. Archiv Für Die Zeichnenden Künste, 12, 1–30.

Fechner, G. T. (1868). Nachtrag zu den drei Abhandlungen über die Holbein’sche (Meier’sche) Madonna. Archiv Für Die Zeichnenden Künste, 14, 149–187.

Fechner, G. T. (1870a). Der Streit um die beiden Madonnen von Holbein. Die Grenzboten. Zeitschrif Fur Politik Und Literatur, 2, 1–18.

Fechner, G. T. (1870b). Ueber das Holbein’sche Votivbild mit dem Bürgermeister Schwartz in Augsburg. Archiv Für Die Zeichnenden Künste, 16, 1–39.

Fechner, G. T. (1871a). Ueber die Aechtheitsfrage der Holbein’schen Madonna. Discussion un Acten. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.

Fechner, G. T. (1871b). Zur experimentalen Aesthetik. Leipzig: Hirzel.

Fechner, G. T. (1872). Bericht über das auf der Dresdner Holbein-ausstellung ausgelegte Album Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.

Fechner, G. T. (1876). Vorschule der Ästhetik. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.

Gropp, R.-M. (2011, July 14). Holbein—Madonna. Deutschlands teuerstes Kunstwerk. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

Haskell, F. (2000). Te Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Leder, H. (2005). Zur Psychologie der Rezeption moderner Kunst. In B. Graf & A. B. Muller (Eds.), Sichtweisen. Zur veränderten Wahrnehmung von Objekten in Museen (pp. 79–90). Berlin: VS Verlag fur Sozialwissenschafen.

Santayana, G. (1896). Te sense of beauty. Being the outline of aesthetic theory. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Titchener, E. B. (1910). Te past decade in experimental psychology. Te American Journal of Psychology, 21, 404–421.

List of Contributors

SECTION 1. FO UNDATIONS

1. Empirical Aesthetics: An Overview 3

Marcos Nadal and Oshin Vartanian

2. One Hundred Years of Empirical Aesthetics: Fechner to Berlyne (1876–1976)

Marcos Nadal and Esther Ureña

3. Revisiting Fechner’s Methods

Gesche Westphal-Fitch

4. Te Link Between Empirical Aesthetics and Philosophy

William P. Seeley

5. Appreciation Modes in Empirical Aesthetics

Rolf Reber

6. Exploring the Landscape of Emotion in Aesthetic Experience

Gerald C. Cupchik

7. Te Neurobiology of Sensory Valuation

Martin Skov

8. Te Evolution of Aesthetics and Beauty

Dahlia W. Zaidel

SECTION 2. ME THODS

9. Historiometric Methods

Dean Keith Simonton

10. Observation Method in Empirical Aesthetics 219

Pablo P. L. Tinio and Eva Specker

11. Observational Drawing Research Methods 235

Justin Ostrofsky

12. Implicit Measures in the Aesthetic Domain 256

Letizia Palumbo

13. Te Study of Eye Movements in Empirical Aesthetics 273

Paul Locher

14. Electrophysiology 291

Thomas Jacobsen and Stina Klein

15. Functional Neuroimaging in Empirical Aesthetics and Neuroaesthetics 308

Tomohiro Ishizu

16. Noninvasive Brain Stimulation: Contribution to Research in Neuroaesthetics 339

Zaira Cattaneo

17. Integrated Methods: A Call for Integrative and Interdisciplinary Aesthetics Research 359

Martin Tröndle, Steven Greenwood, Chandrasekhar

Ramakrishnan, Folkert Uhde, Hauke Egermann, and Wolfgang Tschacher

SECTION 3. O BJECT FEATURES

18. Te Role of Collative Variables in Aesthetic Experiences 385

Manuela M. Marin

19. Processing Fluency

Michael Forster

20. Te Use of Visual Statistical Features in Empirical Aesthetics 447

Daniel Graham

Oshin Vartanian

22. Te Study of Symmetry in Empirical Aesthetics

Marco Bertamini and Giulia Rampone

23. Te Curvature Efect

Guido Corradi and Enric Munar

24. Facial Attractiveness

Aleksandra Mitrovic and Jürgen Goller

SECTION 4. AR TFORMS

25. Te Empirical Aesthetics of Music 573

Elvira Brattico

26. Te Aesthetics of Action and Movement

Emily S. Cross and Andrea Orlandi

27. Aesthetics of Dance

Beatriz Calvo-Merino

28. Te Audio-Visual Aesthetics of Music and Dance

Guido Orgs and Claire Howlin

29. Aesthetic Responses to Architecture

Alexander Coburn and Anjan Chatterjee

30. Aesthetics, Technology, and Popular Movies

James E. Cutting

31. Empirical Aesthetics of Poetry

Winfried Menninghaus and Stefan Blohm

32. Aesthetic Responses to the Characters, Plots, Worlds, and Style of Stories

Marta M. Maslej, Joshua A. Quinlan, and Raymond A. Mar

SECTION 5. THE PERSON

33. Te Role of Attention, Executive Processes, and Memory in Aesthetic Experience

John W. Mullennix 34. Children’s Appreciation of Art

Thalia R. Goldstein

35. Te Infuence of Expertise on Aesthetics 787

Aaron Kozbelt

36. Te Infuence of Personality on Aesthetic Preferences 820

Viren Swami and Adrian Furnham

37. Aesthetic Sensitivity 834

Nils Myszkowski

38. Cross-Cultural Empirical Aesthetics 853

Xiaolei Sun and Jiajia Che

SECTION 6. THE CONTEXT

39. Te General Impact of Context on Aesthetic Experience 885

Matthew Pelowski and Eva Specker

40. Empirical Aesthetics: Context, Extra Information, and Framing 921

Helmut Leder and Matthew Pelowski

4 1. Studying Empirical Aesthetics in Museum Contexts 943

Jeffrey K. Smith and Lisa F. Smith

42. Aesthetic Experience in Everyday Environments 960

Paul J. Silvia and Katherine N. Cotter

43. Te Impact of the Social Context on Aesthetic Experience 973

Stefano Mastandrea

SECTION 7. AP PLICATIONS

44. Design and Aesthetics 993

Paul Hekkert

45. Te Role of Empirical Aesthetics in Consumer Behavior 1010

Vanessa M. Patrick and Henrik Hagtvedt

46. On the Empirical Aesthetics of Plating 1027

Charles Spence

Index 1053

List of Contributors

Marco Bertamini, Università di Padova, Italy

Stefan Blohm, Radboud University, Netherlands

Elvira Brattico, Aarhus University, Denmark

Zaira Cattaneo, University of Bergamo, Italy

Anjan Chatterjee, University of Pennsylvania, USA

Jiajia Che, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Alex Coburn, University of Cambridge, UK

Guido Corradi, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Katherine N. Cotter, University of Pennsylvania, USA

Emily S. Cross, Macquarie University, Australia and University of Glasgow, UK

Gerald C. Cupchik, University of Toronto, Canada

James E. Cutting, Cornell University, USA

Hauke Egermann, Zeppelin University, Germany

Michael Forster, University of Vienna, Austria

Adrian Furnham, Norwegian Business School, Norway

Talia R. Goldstein, George Mason University, USA

Jürgen Goller, University of Vienna, Austria

Daniel Graham, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, USA

Steven Greenwood, Zeppelin University, Germany

Henrik Hagtvedt, Boston College, USA

Paul Hekkert, Delf University of Technology, Te Netherlands

Claire Howlin, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

Tomohiro Ishizu, Kansai University, Japan

Tomas Jacobsen, Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg, Germany

Stina Klein, Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg, Germany

Aaron Kozbelt, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, USA

Helmut Leder, University of Vienna, Austria

Paul Locher, Montclair State University, USA

Raymond A. Mar, York University, Canada

Manuela M. Marin, University of Vienna, Austria

Stefano Mastandrea, Roma Tre University, Italy

Marta M. Maslej, Te Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Canada

Winfried Menninghaus, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, Germany

Beatriz Calvo-Merino, City University of London, UK

Aleksandra Mitrovic, University of Vienna, Austria

John W. Mullennix, University of Pittsburgh, USA

Enric Munar, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Marcos Nadal, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Guido Orgs, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK

Andrea Orlandi, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Justin Ostrofsky, Stockton University, USA

Letizia Palumbo, Liverpool Hope University, UK

Vanessa M. Patrick, University of Houston, USA

Matthew Pelowski, University of Vienna, Austria

Joshua A. Quinlan, York University, Canada

Chandrasekhar Ramakrishnan, Zeppelin University, Germany

Giulia Rampone, University of Liverpool, UK

Rolf Reber, University of Oslo, Norway

William P. Seeley, University of Southern Maine

Paul J. Silvia, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, USA

Dean Keith Simonton, University of California, Davis, USA

Martin Skov, Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, Denmark

Jefrey K. Smith, University of Otago, New Zealand

Lisa F. Smith, University of Otago, New Zealand

Eva Specker, University of Vienna, Faculty of Psychology, Austria

Charles Spence, University of Oxford, UK

Xiaolei Sun, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Viren Swami, Anglia Ruskin University, UK, and Perdana University, Malaysia

Pablo P. L. Tinio, Montclair State University, USA

Martin Tröndle, Zeppelin University, Germany

Wolfgang Tschacher, University Bern, Switzerland

Folkert Uhde, Radialsystem V, Germany

Esther Ureña, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Oshin Vartanian, University of Toronto, Canada

Gesche Westphal-Fitch, University of Vienna, Austria

Dahlia W. Zaidel, University of California at Los Angeles, USA

Empirical Aesthetics

An Overview

Marcos Nadal and Oshin Vartanian

What is Empirical Aesthetics?

Gustav T. Fechner (1871, 1876) had high hopes for empirical aesthetics. He expected it to evolve into a unifed system of general principles of beauty and art. Fechner’s empirical aesthetics, thus, had the same goals as philosophy, but it progressed in the opposite direction. Whereas philosophical aesthetics began “from above,” with general principles that could then be applied to specifc cases, empirical aesthetics began “from below.” Aesthetics from below meant dealing frst with the most basic elements and facts of aesthetics. It meant, specifcally, explaining the reasons for liking and disliking particular cases, and why objects give pleasure or displeasure. From these explanations, a series of principles could then be deduced, which would eventually coalesce into a comprehensive system of beauty and the arts. Fechner, thus, conceived empirical aesthetics as the scientifc investigation of beauty and art that begins by collecting specifc facts that can later be used to build up general principles and, eventually, a general system of aesthetics

A century later, this general system of aesthetics was still not in sight. Empirical aesthetics had not even made much progress moving from the particular cases to the general principles (see Section 2, and Nadal & Ureña, this volume). Daniel E. Berlyne summarized the achievements of a century-worth of research in empirical aesthetics as “relatively sparse and, on the whole, not profoundly enlightening” (Berlyne, 1974, p. 5). Berlyne (1971, 1974) attributed the lack of meaningful progress to unfounded assumptions, outdated theories, and obsolete methods. So, he set out to place empirical aesthetics within a general information theory and motivational framework and to develop a new suite of methods. Berlyne’s (1974) “new experimental aesthetics” difered from Fechner’s “old experimental aesthetics” in that it focused on properties that modifed arousal levels, its explanations were grounded in motivational mechanisms, it studied nonverbal behavior as well as verbal judgments, and it did not aspire to produce

an autonomous aesthetic system, but to show how aesthetic phenomena were the result of common psychological processes. As such, Berlyne (1972) conceived empirical aesthetics as the scientifc study of the motivational efects of collative properties of stimulus patterns. More specifcally, empirical aesthetics was the study of how and why structural features make stimuli appear surprising, novel, complex, or ambiguous; how they modulate arousal levels and, consequently, the stimuli’s hedonic value, that is to say, their pleasurableness, reward value, and incentive value (Berlyne, 1974).

In the 50 years that have passed since Berlyne (1971) reformulated empirical aesthetics via his new experimental aesthetics, the feld has grown substantially and has benefted from the addition of many new methods. Berlyne’s focus on arousal-related motivational mechanisms turned out to be overly restrictive and simplistic. We now know that liking something, or fnding it pleasing, beautiful, or attractive, is not merely a matter of responding to its features. We know that liking, pleasingness, beauty, and attractiveness are infuenced by momentary personal factors, such as expectations, available information (Pelowski & Specker, this volume and Leder & Pelowski, this volume), attention, and memory (Mullennix, this volume), and by stable personal attributes, such as personality (Swami & Furnham, this volume), age, (Goldstein, this volume), expertise (Kozbelt, this volume), aesthetic sensitivity (Myszkowski, this volume), and cultural background (Che & Sun, this volume), among others. Even the physical context (Smith & Smith, this volume and Silvia & Cotter, this volume) and the social context (Mastandrea, this volume) can modulate assessments of liking, pleasingness, beauty, and attractiveness. Indeed, aesthetic appreciation is a good example of the contextual permeability of perception, cognition, and emotion (Bar, 2004; Mesquita, Barrett, & Smith, 2010). We also know now that aesthetic appreciation cannot be reduced to arousal-boosting or -reducing motivational mechanisms. We know it involves complex interactions between several perceptual, cognitive, and afective processes—realized in the form of top-down and bottom-up processes (Chatterjee & Vartanian, 2014; Leder, Belke, Oeberst, & Augustin, 2004; Skov, 2019). Berlyne was right when he argued that the phenomena we consider aesthetic rely on general neural and psychological mechanisms, although the data and methods available to him could not reveal the diversity and complexity of those mechanisms.

Clearly, the knowledge we have gained and the methods we have added since Berlyne (1971, 1974) refashioned empirical aesthetics, and certainly since Fechner (1871, 1876) created the domain, require broadening the defnition of empirical aesthetics. Te most inclusive defnition would conceive empirical aesthetics as the scientifc feld that uses empirical methods to study aesthetics. Although tautological, this defnition specifes the features of the knowledge empirical aesthetics seeks and generates (scientifc knowledge), the kinds of methods it uses (empirical methods), and what the knowledge it seeks and generates is about (aesthetics). It avoids Fechner’s promise of a general system of art and aesthetics, and Berlyne’s reduction of all explanation to a single major mechanism. Te scientifc and empirical aspects of this defnition are probably quite uncontroversial, but there will surely be disagreement among empirical aestheticians today about what aesthetics is. So, let us frst see what it means that empirical aesthetics is a

scientifc feld, and why it is that it uses empirical methods. We can then turn to the contentious issue of what aesthetics is or is not about.

Empirical aesthetics is a scientifc feld

Science relies on a system of procedures that generate a particular kind of knowledge about some natural (as opposed to supernatural) phenomenon. Te kind of knowledge science produces is descriptive and explanatory, testable, replicable, revisable, incremental, and collective. Tus, empirical aesthetics seeks and produces a diferent kind of knowledge than the one philosophical aesthetics does (Seeley, this volume). What, specifcally, does it entail that empirical aesthetics is a scientifc domain?

• First, that, as with research in biology, medicine, and other scientifc disciplines, research in empirical aesthetics occurs with the understanding that its focus of study is coextensive with the natural world. As such, research fndings and inferences emerging in empirical aesthetics must be informed by and can potentially contribute to knowledge in other domains of natural science.

• Second, that empirical aesthetics generates descriptive knowledge by recording data as they are observed, as with surveys and questionnaires, natural observation, and central tendency and dispersion summary statistics. It also generates explanatory knowledge when it uses experimental methods. Experiments involve the manipulation of one or several factors and the observation of the efects on one or several outcomes under controlled conditions. Experimental control is indispensable for explanations in terms of causes and efects, and the associated ability to draw causal inferences.

• Tird, it means that knowledge in empirical aesthetics is not disjointed, but assembled into scientifc theories. Empirical aesthetics formulates scientifc theories based on the descriptive and explanatory knowledge it generates. It uses those theories to make predictions about future results, in the form of hypotheses, and to interpret those results. Tus, the theories of empirical aesthetics should make clear and falsifable predictions, be consistent with existing results, and make accurate predictions of new results. A good scientifc theory is able to accurately describe (what), identify the underlying mechanisms (how), and interpret (why) observations in its domain (Dayan & Abbott, 2001, p. xiii).

• Fourth, it means that these descriptive and explanatory results can be—and should be—tested again in replication studies. Many tenets in empirical aesthetics, and psychology and neuroscience in general, rest only on single experiments, even though some are taught and presented in handbooks as established facts. Te knowledge generated by empirical aesthetics should be reliable, but reliability is difcult to measure unless experiments are repeated and replicated. Some of these replications might confrm previous results, and support their conclusions, while others might not. Reiterated failures to replicate should lead to the rejection of

those tenets, and to new alternative explanations. In this sense, attempts at falsifcation must be central to the practice of the science.

• Fifh, it means that the fndings in empirical aesthetics are revisable. It is not a weakness of scientifc knowledge that it is revisable and provisional; it is one of its fundamental strengths. With revision comes progress, so the more a scientifc feld revises it knowledge, the faster it progresses. A scientifc domain is alive when there is room for major improvements to current knowledge, but lifeless when there is little room for improvement, if that is possible at all. Te revisability of scientifc knowledge is what distinguishes it from dogma. Scientifc dogmatism—resistance to revise ideas held on to as truths despite challenging results—has more in common with faith than with science.

• Sixth, it means that empirical aesthetics commonly progresses through the piecemeal accretion of results produced by diferent teams of researchers. New fndings, or a reinterpretation of old ones, might occasionally make a feld leap forward, and some individuals have a pivotal impact on progress, as Fechner and Berlyne undoubtedly had on empirical aesthetics. But these are the exceptions. As a rule, science is an incremental and collective endeavor.

Empirical aesthetics uses empirical methods

Empirical methods are those that produce data through observation and measurement. Empirical data are fundamental to the testability, replicability, and revisability of scientifc knowledge. Some of the early methods of empirical aesthetics were derived from psychophysics, and they continue to be prominent today. Tey involve the measurement of people’s responses to controlled variations in stimulus features, such as proportion, symmetry, complexity, or predictability. As neighboring felds advanced, empirical aesthetics also borrowed methods from behavioral psychology, cognitive psychology and, more recently, cognitive neuroscience. Te methods now available to empirical aesthetics allow recording verbal judgments, choices and preferences, exploratory time and movements, implicit measures, eye movements, psychophysiological measures, temporal and spatial patterns of brain activity, and the efects of brain stimulation, among others. In addition, technological innovations have made it possible to use several of these methods simultaneously, enhancing greatly our knowledge of various phenomena across multiple levels of measurement (see the chapters in Section 2).

Collecting, analyzing, and systematically organizing observations are essential to the goals of empirical aesthetics. However, this does not mean that there is no theorizing or conceptual work to be done by researchers. Observations are valuable and meaningful to the extent that they have implications for theory. In science, a theory is a formal explanation of a substantial set of observations. Te goal of scientifc theories is usually to reveal the mechanisms whereby a set of observed or hypothetical causes leads to a set of observed or hypothetical consequences. For instance, Berlyne’s (1971) theory mentioned above was intended to explain how certain stimulus properties (i.e., observed causes)

induced certain arousal dynamics (i.e., hypothesized consequences) that, in turn, lead to (i.e., hypothesized causes) pleasure or displeasure (i.e., observed consequences). Teories are the source of the interpretation of patterns of collected observations, and the source of predictions about future observations. Indeed, it is debatable whether atheoretical observation is even possible, given that our decisions regarding what to observe are infuenced heavily by expectations. Tus, empirical aesthetics does not collect observations for the sake of it, but rather to improve its explanations and predictions.

Empirical aesthetics studies aesthetics

Aesthetics is a concept that means diferent things to diferent people (Anglada-Tort & Skov, 2020). In the Western tradition of thinking, aesthetics has had two main foci: making and appreciating art, and the appreciation of the value of certain perceptual features (Levinson, 2003; Sparshott, 1963). Tis dual focus made sense to, and was adopted by, Fechner and others when they applied empirical methods to aesthetics in the late 19th century. Külpe (1897), for instance, wrote that

Te objects investigated by the science are on the one hand judgments of aesthetic pleasure and displeasure, and on the other works of art. Te separation of the two groups shows that there was truth in the old distinction between a philosophy of beauty and a philosophy of art. Te aesthetic judgment extends beyond works of art, since there is a beauty of nature as well as of art; and works of art give us more than the aesthetic judgment, since when we have decided as to the pleasingness or displeasingness of their impression we can go on to discuss the conditions of their origination, the relation between portrayal and portrayed, between the form and contents, copy and model, etc. etc.

(Külpe, 1897, p. 88)

Berlyne (1972) agreed that empirical aesthetics should study art and aesthetic appreciation, but he was wary of grounding the defnition of the feld on either aspect. Such a defnition, he believed, would misleadingly suggest that aesthetics was a separate domain of human life, and would cut empirical aesthetics of from the rest of the behavioral and brain sciences: “Te essentially superstitious view that the aesthetic realm is sharply distinct from the rest of life and governed by principles peculiar to itself has long been a bugbear” (Berlyne, 1972, p. 304).

Today, empirical aesthetics continues to be divided about what makes art and aesthetic experiences unique and diferent to other kinds of objects and experiences, respectively. Te various positions on this topic lie along a continuum. At one pole of the continuum we fnd researchers who argue that art and aesthetic experience involve unique forms of pleasure or emotion, and that it is therefore important to distinguish aesthetic pleasure, aesthetic emotions or art emotions from nonaesthetic or non-artbased pleasure and emotion (Christensen, 2017; Fingerhut & Prinz, 2020; Makin, 2017;

Menninghaus et al., 2019). At the other pole of the continuum we fnd researchers who argue that art and aesthetic experience involve the same kind of pleasure and emotions as any other kind of object and experience and that, therefore, the notions of aesthetic pleasure, aesthetic or art emotions are unnecessary and misleading (Berlyne, 1972; Nadal & Skov, 2018; Skov & Nadal, 2019, 2020). Somewhere between both of these poles we fnd the views of researchers who have argued that aesthetic experiences arise from a unique combination of general cognitive and afective processes (Leder et al., 2004; Pelowski, Markey, Forster, Gerger, & Leder, 2017), and those who have argued that aesthetic emotion is ordinary emotion lacking its motivational component (Chatterjee, 2014; Chatterjee & Vartanian, 2014).