Kingdoms, Empires, and Domains

The History of High-Level Biological Classification

MARK A. RAGAN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ragan, Mark A., author.

Title: Kingdoms, empires, and domains : the history of high-level biological classification / Mark A. Ragan. Other titles: History of high-level biological classification Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022039010 (print) | LCCN 2022039011 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197643037 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197643051 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Biology—Classification—History. | Biology—Nomenclature—History. | Classification of sciences—History. Classification: LCC QH83 .R343 2023 (print) | LCC QH83 (ebook) | DDC 578.01/2—dc23/eng/20221005

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022039010

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022039011

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197643037.001.0001

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

Fellow Labourers! The Great Vintage & Harvest is now upon Earth. The whole extent of the Globe is explored. Every scatter’d Atom Of Human Intellect now is flocking to the sound of the Trumpet.

All the Wisdom which was hidden in caves & dens from ancient Time, is now sought out from Animal & Vegetable & Mineral. . . .

So spake Ololon in reminiscence astonish’d, but they Could not behold Golgonooza without passing the Polypus, A wondrous journey not passable by Immortal feet, & none

But the Divine Saviour can pass it without annihilation. For Golgonooza cannot be seen till having pass’d the Polypus It is viewed on all sides round by a Four-fold Vision, Or till you become Mortal & Vegetable in Sexuality

Then you behold its mighty Spires & Domes of ivory & gold . . .

William Blake, Milton (1804)

[Blake, Milton. In: Maclagan & Russell (1907), at 25:17–21 and 35:18–25 (original pagination)]

Budé: Roman law (1508)

Rabelais: literature in the vernacular (1546)

Jean Bodin: political theory (1576)

Jacopo Zabarella: Aristotelian logic (1606)

Johann Thomas Freig: Ramist natural history (1579)

Robert Burton: English vernacular (1621)

Juan Eusebio Nieremberg: baroque nature (1635)

David Person: rare and excellent matters (1635)

Henry More: the Spirit of Nature (1682)

Herbals (from 1475)

The rise of scientific botany 1: 1490–1580

The rise of scientific botany 2: 1580–1680

13.

The rise of scientific zoology 1: 1520–1550

The rise of scientific zoology 2: the momentous 1550s

The rise of scientific zoology 3: the encyclopædists 1560–1660

The rise of scientific zoology 4: curiosities and specialization

a fourth division of nature?

14.

15.

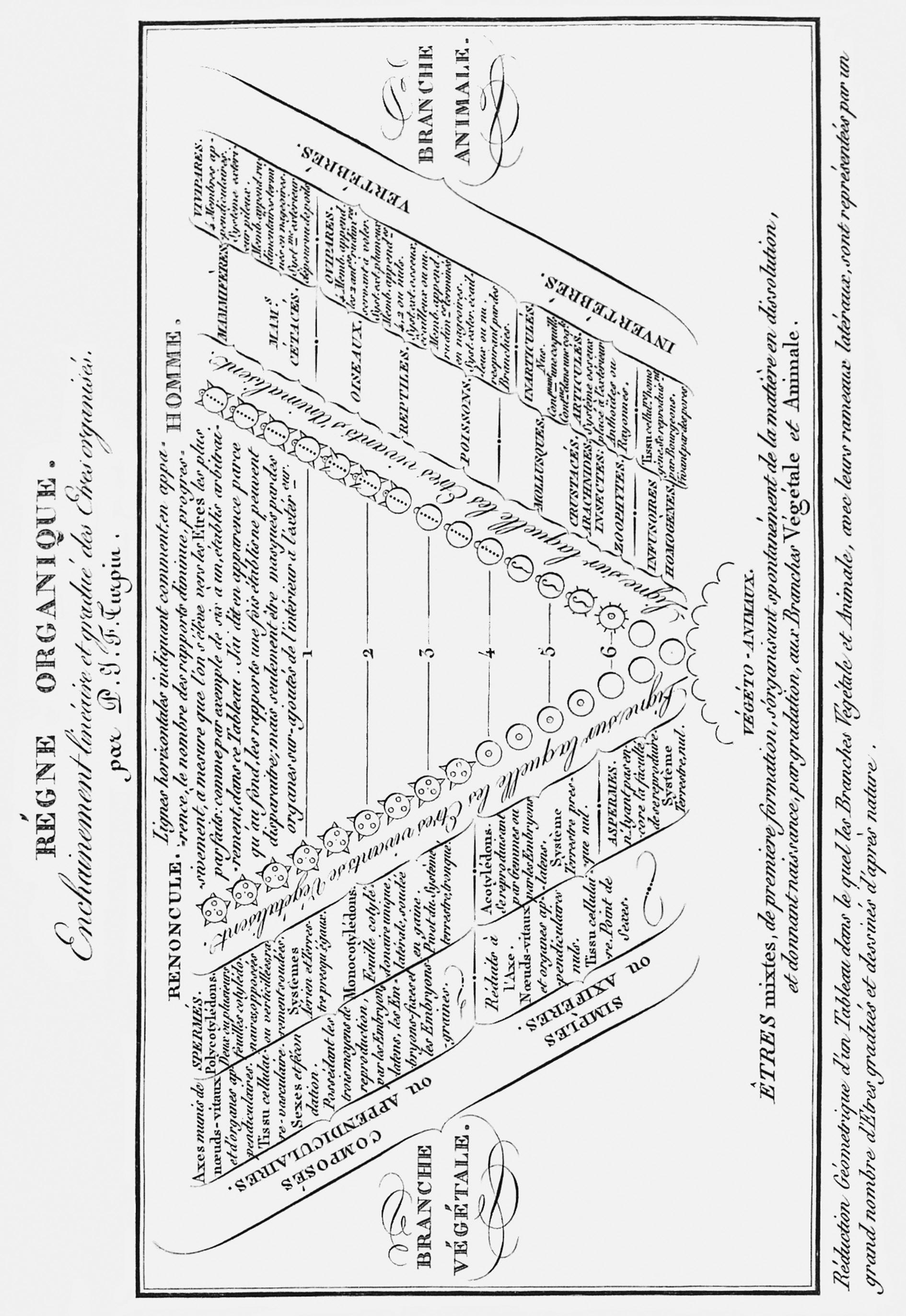

Pierre-Jean-François

végéto-animaux

de Blainville: infusoria as an

Jean-Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent: Règne

18. Naturphilosophie

Illustrations

Figures

6.1. Anonymous Twelfth-century manuscript, souls ascending from earth to God. 86

9.1. Cosmology of alchemy, according to the Kitāb Sirr al-khalīqa 145

9.2. Pico della Mirandola’s three worlds, as modified by Le Fèvre de La Boderie. 151

9.3. The Fountain of Mercury, from Rosarium philosophorum. 155

9.4. Kirchweger, Aurea catena Homeri. 160

11.1. Freig, division of corporeal bodies following the method of Ramus. 182

16.1. Linnæus (Giseke), genealogical-geographical table of the affinities of plants. 267

16.2. Buffon, genealogical table of the different races of dogs. 270

16.3. Goldfuss, animal-globe or Easter egg. 271

16.4. Von Baer, schematic representation of animals. 273

16.5. Eichwald, table of transitions among animals. 274

16.6. Adrien de Jussieu, map of genera of Rutaceæ 275

16.7. Duchesne, genealogy of strawberries. 277

16.8. Eichwald, tree of animal life. 279

16.9. Horaninov, schematic diagram of nature.

16.10. Fischer von Waldheim, organized nature as two cercles de mouvement

16.11. Macleay, general view of organized matter.

16.12. Macleay, quinarian arrangement of the animal kingdom. 285

20.1. Hogg, diagram of natural bodies, or of the four Kingdoms of Nature. 373

20.2. Hitchcock, palæontological chart showing plants and animals as branched series. 374

21.1. Haeckel, phylogenetic table of stem-relationships of the phyla of the Animal Kingdom. 394

21.2. Haeckel, Stammbaum of the organic world. 398

21.3. Bütschli, Stammbaum of organisms. 402

21.4. Klebs, relationships among the lower organisms. 405

21.5. Entz, relationships in the organic world. 408

22.1. Whittaker, four kingdoms of organisms. 418

22.2. Whittaker, five-kingdom system based on three levels of organization. 419

22.3. Margulis, modification of Whittaker’s five-kingdom scheme. 420

22.4. Mereschkowsky, representation of the organic world as two Stämme.

425

xiv List of Illustrations

23.1. Margoliash, Fitch, and Dickerson, statistical phylogenetic tree of cytochromes c. 434

23.2. Woese, universal phylogenetic tree determined from rRNA sequence comparison. 438

23.3. Woese, Kandler, and Wheelis, universal phylogenetic tree in rooted form. 438 Table

15.1. Major editions of Systema naturæ 250

Preface

Animals, vegetables, minerals: for twenty-six centuries, these three great groups have encompassed the scope of material bodies on earth. Philosophers, poets, naturalists, even children recognize their members: things sensate but mortal; living but insensate; and organized but nonliving. Homo sapiens, the one animal capable of pride, sometimes accords himself a fourth.

Yet as many of us are aware—perhaps dimly from some long-ago biology lecture—certain microscopic beings are motile like animals, yet pigmented like plants. In 1866, citing little precedent, Ernst Haeckel established for these and other simple creatures a third major group of living beings: the protists. Why did he take this step where others had not? Or perhaps there had been other supernumerary kingdoms of life, now—or even in Haeckel’s day—lost to the mists of time. And this odd word zoophyte, tucked away at the back of the dictionary: are zoophytes somehow both plant and animal? Are (some) protists zoophytes?

As a young scientist interested in the diversity of life, I read Haeckel’s Generelle Morphologie and pondered these questions. Later, as a member, then President, of the International Society for Evolutionary Protistology (ISEP), I had occasion to investigate the history of Third Kingdoms of Life. I was scarcely prepared for what I found. Plants and animals have not, in fact, been recognized as the highest-level taxa of living beings since time immemorial. Zoophytes were first considered intermediate between plants and animals not in Eighteenth-century Europe, but in Fourth-century Syria, and eventually found a place in a classification of animals that was falsely attributed to Aristotle. The most-inclusive taxa began to be called kingdoms only in 1604—first by alchemists, not botanists or zoologists. Since then, more than fifty taxa at kingdom level or above been proposed by philosophers, scholars, or naturalists including Linnæus. Haeckel’s Protista has itself been pronounced dead more than once.

I invite you, dear reader, to join me on this eclectic tour of the history of the idea that there is more to the living world than plants and animals. We shall meet aboriginals and alchemists, philosophers and mystics, saints and heretics, physicians and poets, soldiers and diplomats, sea-captains and stonemasons (well, one stonemason), botanists, zoologists, Haeckel himself, and other protistologists. Our story unfolds across twenty-three chapters, each describing a theme or historical episode. The narrative is broadly chronological, although certain chapters run in parallel and are best read together. I rely heavily on primary texts and authoritative translations, but draw on secondary literature where appropriate.

My fascination with algae and protozoa can be traced to a microscope given me at age twelve by my parents; then classes and an honours paper with David J. Chapman at the University of Chicago. James S. Craigie supervised my PhD project, on brown seaweeds, at Dalhousie University. Over succeeding decades, research collaborations brought encounters with amazing creatures: diatoms, sponges, red algae, Spirogyra, dinoflagellates, charophytes, Cryptococcus, chytrids, ichthyosporeans, ciliates, labyrinthulids, diplomonads, Sulfolobus, various bacteria, dinoflagellates again, corals, and Chromera, in approximately that order. I outlined this book (1997) and drafted two early chapters (1998–2000) while at National Research Council (NRC) Canada, then took it up again in early 2018 upon retirement from the University of Queensland. In the interim, I read widely across the history of high-level biological classification, with special focus on organisms that do not fit comfortably within the canonical kingdoms of living things.

I did not make this journey alone. First and foremost, I thank my wife, Chikako, and our children, Alicia and Wesley, for their love and forbearance. Colleagues in my research institutions, in ISEP, in the Evolutionary Biology Program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, in the Reef Future Genomics 2020 consortium organized by the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, and many others brought inspiration and wondrous organisms. Marvin Green, Dave Chapman, Emanuel Margoliash, Jim Craigie, Arne Jensen, Jack McLachlan, Carolyn Bird, Max Taylor, Lynn Margulis, John Corliss, Tom Cavalier-Smith, Lynn Rothschild, Miklós Müller, Ford Doolittle, Carl Woese, and John Mattick have been teachers, mentors, colleagues, and friends.

I could not have begun this book without a firm grounding in Latin, for which I thank Agnes Landis. My first steps into the early literature were facilitated by Gina Douglas (Linnean Society of London), Tony Swann (Wheldon & Wesley), and colleagues at the Natural History Museum (London). Staff at the NRC Canada National Science Library and the University of Queensland Library tracked down obscure books and articles. Online resources, notably the Biodiversity Heritage Library and the Internet Archive, opened an unimaginable world of early texts. J. Patrick Atherton KHS, Denis Brosnan, Anitra Laycock, Georges Merinfeld, Amin R. Mohamed, and Atefeh Taherian Fard provided expert translations. William Chittick, Ford Doolittle, Ernst Mayr, Minaka Nobuhiro, Marie-Odile Soyer-Gobillard, and David M. Williams helped me understand specific issues or viewpoints. Nick Hamilton photographed Figure 9.1.

I owe a debt of gratitude to my editors at Oxford University Press, Jeremy Lewis and Michelle Kelley, for their belief in this project and unfailingly wise advice. Suganya Elango and her team at Newgen Knowledge Works brought my dream to reality on the printed (and electronic) page.

Finally, dear reader, let us return to the theme of texts. Primary texts—or more typically, their instantiations in print—form the bedrock of any deep history of ideas. We accept each text as a gift handed down to us, through the years, from its author. Texts set out an argument, reveal assumptions, and open a window into

the author’s world. Sometimes we glimpse the author’s personality: even on the printed page, we do not mistake Tertullian for Augustine, nor Erasmus Darwin for Gilbert White. Moreover, a printed work bears evidence of skill and craftsmanship: of its author to be sure, but also of its illustrator, editor, printer, and bookbinder. Institutions and individuals have preserved books through natural disasters, wars, and periods of intolerance. For all these reasons—commitment to historicity, gratitude to our antecessors, respect for the printed word—I present texts as I find them. My translations are literal rather than literary. Items in the reference list hew closely to their original form, with minimal stylistic concessions for capitalization, italicization, and forms of diacritical marks. Nor have I retrofit italics onto scientific names or embedded titles. Even so, we shall often enough find ourselves in contested areas of orthography, for which I accept full responsibility.

Mark Ragan Brisbane, Australia

The earliest Nature

We have been transported one million years back in time. From our vantage point, the panorama of the vast African plain unfolds before us; morning mists rise as the sun begins its ascent. Herds of zebra graze silently, alert for lions. A small hunting party of hominids, armed with simple clubs and poles, stalks the herd. A kilometre away another party gathers grasses and seeds, watchful too for the lion. Distinguishing carnivore from herbivore was then, as now, a key survival skill; had these early hominids not recognized the distinction and adjusted their behaviour correspondingly, there might be no Homo sapiens today. For a hundred thousand generations hunters and gatherers, carnivores and herbivores were linked in this way. Long before there was symbolic language, or indeed the prerequisite cranial capacity, our distant ancestors must have been strongly selected to recognize and distinguish broad classes of objects in their environment: those immobile, green, and cellulosic, and those motile and suffused with blood.

We follow our ancestors back to their camp, watch them re-enact the hunt, gesticulate, dance. We cannot know precisely what they imagine themselves to be doing: teaching and learning, celebrating, appeasing the spirits? Whatever their intent, their abstracted or ritualized behaviour conveys selective advantage by bringing past success to bear on present and anticipated future needs: roots, seeds, meat, skins. Even without symbolic language, each member of the group shares, as common points of reference, the host of agents in their environment—the sun, moon, and stars; day and night; earth, sky, and horizon; wind and rain; drought and wildfire. Why should we imagine that they linked animal more strongly with plant than with rainy season or hunting spirit of our clan?

We are still painting with too broad a brush. These distant ancestors of ours were dramatically successful. Whether primarily by selection or through their own emerging perspicacity, they must have reacted differently to carnivores than to herbivores, differently to fruit trees than to grasses or fungi. Even birds and insects avoid poisonous plants. Was not the lion-hunting party constituted differently than the zebra-hunting party, the root diggers differently than the fruit gatherers? There is no a priori reason to believe that animal, or plant, elicited from them any common activity or social organization. Even if our ancestors conceptualized herbivores and carnivores as a single class, did this class include birds, fish, snakes, insects, worms? Do these too graze in fine herds in the morning mists, or stalk their prey in the tall

grass? Do their carcasses permeate the camp with the smell of roasting flesh, fill the belly, increase fertility, appease the spirits?

Primitive concepts of natural entities

As we shall see in subsequent chapters, for century upon century all manner of authorities—philosophers, naturalists, littérateurs have juxtaposed the terms animal and vegetable (or animal, vegetable, and mineral; or these plus man) with confidence often verging on nonchalance. One might almost be forgiven for concluding that the concepts and distinctions implied by each of these words alone, and by their juxtaposition, must somehow be self-evident. But is this, in fact, the case? Have high-level concepts of animal and vegetable1 truly been with us since the beginning?

The question has received surprisingly little attention. In Geschichte des Ursprungs der Eintheilung der Naturkörper in drey Reiche, 2 Johann Beseke identified Emmanuel König as the first (in Regnum animale, 1682) to refer to minerals, vegetables, and animals as the three kingdoms of nature 3 In fact (as we shall see in due course), the first such description dates to the first decade or two of the Seventeenth century. The three-volume Histoire naturelle générale des règnes organiques (1854–1862) by Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire4 offers far more detail, not all of it accurate. More recently, Susannah Gibson introduced her delightful account of mid-Eighteenth-century natural history with a brief synopsis of the views of Aristotle, Pliny, Linnæus, and others on animals, vegetables, and minerals.5 More typically, however, treatments such as Samuel Haughton’s The three kingdoms of nature (1868) offer no historical context whatsoever.

How, then, were animals and plants conceptualized long ago? The very nature of this question requires us to look far beyond written sources. Our argument has multiple interdependent strands: none is entirely unproblematic or fully definitive, but most lead in the same direction. In this chapter we consider the earliest possible lines of evidence, including from cave drawings and other early figurative art, comparative linguistics, folk taxonomies, creation myths, totemism, animal deities, and anthropomorphized plants, up to the earliest written records. We shall find only hints of evidence for significant antiquity of animal and vegetable as static high-level concepts. Instead, we uncover a diverse, fluid conceptual landscape in which every boundary is transgressed again and again: a landscape not of fixity, but of metamorphosis. But let us not get ahead of our story.

Early figurative art

Three million years ago, australopithecines wielded stones as tools; carved tools had appeared by half a million years later. Inevitably, little can be inferred about their probable use, or the mindset of those who used them. Flint-tipped spears

obviously useful for hunting appeared very much later, towards the end of the Upper Palæolithic, an era we can glimpse via figurative art—etchings, paintings, and carvings, sometimes in combination—across more than one hundred presentday countries.

Abstract representations in red ochre at Blombos Cave, South Africa, date to 75000 bce 6 The earliest known figurative art comes to us from the Upper Palæolithic: cave art depicting a native pig (Sulawesi, at least 43500 bce); hunting scenes, including humanoid images with facial and other bodily features of animals (Sulawesi, 41900 bce); a standing human figure with the head of a lion, carved in mammoth ivory (Swabia, 38000 bce); and engravings of aurochs, ibex, horses, and mammoths (France, 36000 bce). Modern humans carved fertility-figures from mammoth tusk at 40000–35000 bce, and fashioned others in ceramic around 24000 bce. A long-eared owl is engraved at Chauvet (31000–28000 bce), and other birds (perhaps geese) at Cussac (around 25000 bce) and Roucadour (around 24000 bce) in France. Images of fish, crocodiles, turtles, wallabies, emus, and other animals are common in early Australian rock art.7

Representational art flourished in Europe during 17500–9000 bce. Best known are the magnificent cave drawings in southwestern Europe including at Lascaux (around 17000 bce) and Altamira (14800–13100 bce), with powerful horses, aurochs, bison, and large animals depicted by the thousands. We may speculate on what these drawings meant to their creators, but they do not constitute a zoology in any modern sense. The cave floor at Lascaux is littered with reindeer bones, for example, but no reindeer are depicted on the walls—although they are at Le Placard (17500 bce) and Les Combarelles (12000 bce). Images of snakes, insects, birds, or plants are uncommon. At Lascaux in particular, images of different animals are not distributed at random across the walls and ceilings, but instead are sometimes associated spatially in ways that may reflect shared ecosystems, seasonality, or “male” and “female” animal types.8

Human images are infrequent in European cave art of this era, and unlike the anatomically accurate animals, are greatly simplified. Some are associated with the hunt, while others probably had a ritualistic or shamanistic significance. In particular, “sorcerer” figures combine human with animal features: a humanoid torso with antlers (Trois Frères, 14000–13000 bce), a spear-hunter with a bird-like head or mask (Lascaux), bison-headed (Gabillou) and seal-headed men (Cosquer, 17000 bce). At Lascaux we also find a two-horned chimæra with “the body of a woolly rhino, the shoulder of a bison, the head of a lion and the tail of a horse”.9 Humans become the centre of attention in the later Spanish Levantine rock art (8000–3500 bce). We see them hunting with bow and arrow, engaging in battle, dancing, tending domesticated animals, and collecting honey. Birds, fish, spiders, and bees are occasionally depicted, plants rarely so. At several sites, women are depicted working in fields, holding digging sticks, poles, or plants.10 A famous mural at Selva Pascuala shows mushrooms, perhaps the psychoactive Psilocybe, and (if so) may point to its ritual use.11

Symbolic language and folk taxonomies

Our capacity for language is one of the more-credible reasons why we humans deem ourselves superior to other earthly beings. The genes that enable us to vocalize had counterparts in the genomes of Neandertals and Denisovans.12 In light of research with chimps, great apes, and marine mammals, our superiority is perhaps less clearcut than we once proudly assumed. Even so, human language is surely unequalled in descriptive power, nuance, and abstraction. But the challenge our ancestors faced was great indeed: to conceptualize and express the richness of nature and natural phenomena.

Adam gave names to cattle, fowls, and beasts—names that refer, of course, not to individuals but to groups: naming is classifying.13 Egyptian papyri refer to oxen, cattle, goats, asses, lions, hounds, crocodiles, wild fowl, corn, sycamores, shrubs, thorns, hedges, and melons.14 The Egyptian Book of the dead adds the ape, ram, hippopotamus, antelope, cat, panther, dogs, jackal, serpent, phœnix (bennu bird), ostrich, duck, heron, hawk and other birds, fish, tortoise, scarab, scorpion, worms, palm tree, lotus, barley, figs, orchards, and grass.15 From cuneiform characters on clay tablets we know that 5000 years ago, Babylonians distinguished at least thirty kinds of fish, hundreds of terrestrial animals, and at least 250 kinds of plants. Lists of plants and medicines in the royal library at Nineveh ran to more than 400 names or expressions.16

Primary types could be aggregated into more-inclusive groups. The Book of the dead refers to beasts and beasts of the field. 17 According to Reginald Thompson, in the Ras Shamra (Ugarit) texts (13000–11000 bce) šam-mu referred to plants in general, whereas in Assyrian texts it could mean plant, grass, vegetable, or mineral drug. 18 In old Sumer, names for animals were written with a cuneiform prefix that could place them within a more-inclusive group.19 Some Babylonian tablets distinguish fish from other water-dwellers; on others, plants are arranged into trees, herbs, spices and drugs, and cereals. Large quadrupeds (horses, camels, asses) are sometimes listed separately from small ones (dogs, hyenas, lions), and fruit trees are grouped by shape of their fruit.20 Genesis refers to quadrupeds, birds, fishes, and reptiles, as do the Babylonian and Hebrew narratives of the Great Flood. The earliest known epic is that of Gilgamesh, the legendary fifth ruler in the first postdiluvian dynasty of Uruk in Mesopotamia, during the Fourth millennium bce.21 The story is replete with names of animals, plants, and precious stones encountered by Gilgamesh and Enkidu. Several passages speak of aggregate groups: “all living creatures born of the flesh”, “all the trees of the forest”, “all long-tailed creatures”, “the beasts we hunted”, and “small creatures of the pastures”.22

A system of aggregated and subdivided groups is the beginning of a hierarchy. Only slightly later than Gilgamesh is an alabaster vase from Warka, now in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.23 This meter-high vase bears three registers of decoration: the top shows the goddess Inanna, the middle a procession of porters bearing offerings, the bottom a row of sheep or goats above, stalks and heads of grain beneath. Is this

a statement that god, man, animal and plant are arranged in hierarchical order and comprehend all life? Or is it something simpler, the record of a harvest ritual or feast day?

Around the world, native tongues are often rich in words for plants and animals. As often as not, the named groups correspond acceptably well to modern taxa.24 However, folk taxonomies are limited to local flora and fauna, tend to be shallow (that is, have few intermediate ranks), and as pre-theoretical systems often deal poorly, or not at all, with organisms that are anomalous or share features of different groups, such as bats. Aggregate groups can be broad (bird, fish, tree) or narrow, and to outsiders may seem arbitrary. Moreover, folk taxonomies tend not to have a name for the group—animal or plant at the very top of the hierarchy. In the anthropological literature, this group is called the unique beginner. 25 In the Mayan (Tzeltal) language, which has a unique beginner (canbalam1) for animal, the term excludes man; different informants variously included or excluded bats and/or armadillos.26

Of course, absence of a standard term does not necessary imply absence of the corresponding concept. Tzeltal lacks a word for plant, but numerous expressions contrast plants with members of other domains. Plants “don’t move” (ma šhihik), whereas animals do; they “don’t walk” (ma šbenik), “are planted in the earth” (?ay c’unulik ta lum), and “possess roots” (?ay yisimik). Names for types of plants are joined with the numerical classifier tekh, whereas animal names are used with the numerical classifier hoht, and names of humans with tul. 27 Variations on these themes can be multiplied. Early explorers recorded no words for animal, plant, or vegetable in Aztec, Algonquin, Cree, or Yoruba.28 Dawson29 reported the same for three Australian aboriginal languages, although each had inclusive words for bird and insect, and distinguished freshwater fish from saltwater fish. Greenland Eskimos have general terms for plants, fish, and sea animals, while their word for living can also mean an animal. 30 Adam named cattle, fowls, and beasts, but it is not recorded that he coined the terms animal and plant. On the other hand, Gilgamesh’s all living creatures born of the flesh surely comes close to being a unique beginner.

Finally, folk taxonomies often lump small, superficially undifferentiated beings into a catch-all group of “bugs”, whether because such creatures are difficult to examine, intrude little into human lives and livelihood, or (following Atran) fall far short of the glorious standard of comparison, man himself.31 The rich vocabulary Australian aborigines deploy for insects,29 many of which serve as sources of food, provides a telling counterexample. But lumping residual forms under a single name conflates heterogeneous types, while leaving the boundaries of animal or plant vague or unexamined.

Perhaps our propensity to aggregate and subdivide arises ultimately from the hierarchical nature of human society;32 in any event, taxonomy is “everywhere as old as language”.33 Beyond this it is risky to generalize: textual materials are fragmentary, languages evolve and die, and we—as anthropologists, archæologists, biologists, or translators—necessarily seek, and find, reference points in our own societies, time, and languages. Perhaps the scribes of Sumer or Thebes considered it

blindingly obvious that there are plants and animals. But so far, we have uncovered little evidence that modern concepts of animal and plant are necessary or universal, or have been firmly entrenched since time immemorial.

Creation myths

By their nature, creation myths are stories of transformation. A recurrent theme from many lands and cultures is that of the Earth Mother: humans were fashioned from earth, clay, dust, or rock, or arose from a spring.34 Maimonides connected the name of the first man, Adam, to adamah, “earth”.35 A goddess shaped Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s companion, from clay,36 and Prometheus fashioned man and woman from clay. The Qumran scrolls declare man to be “moulded clay” and “a creature of clay”.37 Enoch dreamt not only of man but also of diverse animals and birds, springing up from the earth.38

Other creation myths link man with animals. Storyteller “Jim” Mulluk of the Ngulugwongga people in northern Australia begins the story of Manark the mother kangaroo and Memembel the porpoise as follows: “In the Dreamtime when animals were the people, the Porpoise was a woman called Memembel.” Similarly, the story of Micherin, the dingo: “A long time ago when animals were people the Dingo was a black fellow”; and the story of Murroo, the dugong: “In the Dreamtime when animals and trees were people, the Dugong used to be a beautiful girl.”39

A close relationship between mankind and other earthly beings lies at the heart of totemism, “that curious system of superstition which unites by a mystic bond a group of human kinfolk to a species of animals or plants”.40 We take the word totam from Ojibwa, but totemism is, or was, more widespread, not only among North American native societies but also in Australia, Africa, and elsewhere.41 The totem itself has been interpreted as an imagined intermediate between the group and its ancestor, although totems include not only mammals but also fish, salamanders, caterpillars, plants, seeds, fire, wind, stars, planets, and the sea.42 In other traditions, our link with creation or the heavens is instead represented as a tree, seen not as a totem (a symbolic ancestor or intermediate) but instead as an organic bridge between earth and heaven.43

Whatever the nature of these imagined relationships—and we would be foolhardy to generalize too aggressively in the face of such diversity—it is clear that even in conceptualizing ourselves, human imagination has not been overly constrained by the boundaries of what have been recognized as the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms.

Animal deities and anthropomorphized plants

Diverse societies have depicted gods, deities, and other sacred figures as animal or part-animal. Ancient Egypt was notably well-supplied with animal gods

including Horus, with the face of a hawk; Anubis, with the head of a canine; Sekmet, with the head of a lion; and Thoth, with the face of a heron.44 An Eighthcentury bce relief from ancient Khorsabad depicts a Babylonian water-god, man above the waist, fish below. Indians had Ganesha, the elephant God; Cambodians Garuda, a winged monster with the face of a bird and the feet of a beast; Cretans the Minotaur, Greeks Pan, and so on. The winged Lion of St Mark graces Chartres Cathedral.

Hybrid creatures inhabited not only the sacred world but also the profane.45 Gilgamesh encountered two “awful guardians” at the mountain of the sun, part man, part lion, and with the tail of a scorpion.46 The sphinx of Thebes dates to about 1400 bce; winged and sometimes human-headed bulls adorned walls and gates in imperial Assyria and Persia. The phœnix served both pagan and Christian myth, appearing in the Physiologus and in authors as diverse as Ovid, Tertullian, Tacitus, Celsus, Philostratus, and St Ambrose.47 Chinese ritualistic bronze vessels dating to the Second millennium bce depict composite animals, and ancient Chinese texts described hybrid beasts “unhampered by conventional genetic laws”;48 to this day the merlion, with the head of a lion and the body of a fish, symbolizes the citystate of Singapore. Mythology and literature are replete with griffins, manticores, ægopitheci, arctopitheci, leontopitheci, cynocephali, centaurs, fauns, satyrs, silenians, sea-wolves, sea monsters, eals, gorgons, sirens, harpies, mermaids, lamias, tritons, nereids, winged serpents, yales (centicores), and other chimæric beings. Other creatures, although not hybrids per se, certainly lay outside the standard boundaries of humanity: lares, genii, wood nymphs, foliots, airies, Robin Goodfellows, and trolls.49

Hybridization could draw upon not only animals and man but also the physical world. According to the Iliad, the west wind Zephyrus fathered wind-swift mares. Astolpho’s horse Rabican was born of “a close union of the wind and flame, and, nourished not by hay or heartening corn, fed on pure air”. The wind is personified in Bengalese tradition, the sky in many cultures, and signs of the zodiac are even today depicted as animals. Herodotus relates that Egyptians believed fire to be thurion emphochon, a live beast.50

Although mankind has seen fit to worship an appalling diversity of zoomorphs, we seem to have drawn the line at plant deities.51 Nonetheless, a herb conveyed immortality to Gilgamesh,52 and mushrooms have been held sacred in various religions. Many early systems of medicine were centred on a fundamental sympathy between medicament and patient; diverse plants were considered to share these sympathies, while minerals were largely excluded from the Western pharmacopœia until much later.53

The most human-like of plants was undoubtedly the mandrake (genus Mandragora), which was widely held to occur in two forms, male and female. Various myths, some rather gruesome, speak of its growth from human sperm or urine spilled upon the ground. Often explicitly described as a hybrid between person and plant, mandrakes were reputed to be so “full of animal life and

consciousness that they shriek when torn out of the earth”. They could bring fertility not only to women but to female elephants as well.54

Physical objects have also been deified, personified, or otherwise assigned properties more usually associated with animals. In the Neoplatonic tradition, heavenly bodies were beings or souls. Saint Paul called the sun, moon, and stars creatures, and in this was followed by Origen, Jerome, and other Fathers of the Church.55 Giordano Bruno later described the heavenly bodies as animals possessing not only sensation but also intelligence—indeed, intelligence perhaps greater than our own.56 The Fourth-century bce Epinomis, earlier misattributed to Plato, posits that there are five principal types of creatures, each associated with an element: the visible gods (i.e. the stars) associated with fire; creatures of the earth (men, animals, and vegetables) linked through legs, belly, or roots to the earth; daimones of the æther; a race of æry beings; and one of watery beings, perhaps the nymphs.57 In many cultures, anthropomorphic concepts of sexuality, fecundity, birth, and death have been projected onto the earth, and expressed as various rites and mysteries. Some involved mining and metallurgy—for example, the Malaysian belief that ore bodies are alive and can actively elude miners precisely as animals can elude hunters.58 Others surrounded agriculture, horticulture, and the fertility of the earth.59

Transformation and metamorphosis

Our early hominid ancestors must have noticed not only regularities among individuals—the basis of classification—but also how these individuals change. Wind and clouds turn to rain, plants sprout up from bare earth, tadpoles become frogs, grubs and caterpillars are reborn as beetles and butterflies, and all flesh journeys “from dust to dust”. The Neolithic horses and deer at Lascaux are painted with seasonal coats corresponding to the mating and rutting seasons. It is hardly a surprise that from every age, land, and people come abstracted tales of transformation and metamorphosis. Perhaps more surprising is the frequency with which these changes transgress every boundary, including those that might separate animals, vegetables, and minerals.

A Neolithic mural at Çatal Höyük (6500–5650 bce), in present-day Anatolia, depicts the fertility goddess having given birth to the head of a bull (the male god).60 Dumuzi, primary consort of the Sumerian fertility-goddess Inanna, was transformed into a snake.61 In the Egyptian Book of the dead, the deceased can be transformed into a golden hawk, a lily, lotus, phœnix, heron, serpent, crocodile— indeed into whatsoever form he pleases.62 Lot’s wife became a pillar of salt, and Aaron’s rod a serpent.63 Athena turned the Gorgon Medusa into a winged monster with reptile locks. Empedocles famously stated that “I have been ere now a boy and a girl, a bush and a bird and leaping dumb fish in the sea.”64 In The Papyrus of Ani the deceased states that his physical body does not decay after death, but is instead

transformed into a spiritual body symbolized by the bennu (phœnix). Budge translates the hieroglyphs “I grew [germinated] in the form of plants.”65 Although hardly a taxonomic statement, this does imply a class of things that germinate.

In Metamorphoses, Ovid announced his “intention . . . to tell of bodies changed to different forms” and went on to relate more than one hundred transformations.66 Some sixty-five of these speak of transformations among animals, men, demigods, and gods, with man-to-bird being a favourite; sixteen describe the change of animal, man, or god into vegetables or vegetable products. There are twenty metamorphoses from animals into minerals, earth, or waters; six apotheoses of animal or god into a star; the wooden ships of Troy are changed to sea-nymphs; and three minerals are made animal (as is the entire city of Ardea). Wood is changed to stone, seaweed to coral, and the spear of Romulus into a tree.67 In The golden ass, Apuleius tells of a man who was first transformed by witches into an animal, then returned to human form after an ecstatic vision of the goddess Isis.68

Writing in the Seventh century ce, Isidore of Seville allegorized classical mythological monsters, and was noncommittal on many reported transformations of men into animals. Other transformations—including that of Diomedes’s companions into birds—he accepted as not mere “fabled fictions” but proven by “historical evidence”. He accepted too that bees can arise from cattle, locusts from mules, and (citing Ovid) scorpions from crabs.69 Isidore was made a saint (indeed, a Doctor of the Church), but the Church remained cautious about transformation, on the one hand celebrating the rite of transubstantiation (see below) while on the other condemning, or worse, witchcraft and most forms of magic. Indeed, the canon law collated by Burchard of Worms in about the year 1020 expressly rejected the possibility that people could be transformed into animals70 a move that neither prevented the persecution of witches, nor diminished the appeal of tales of magic.71 Much later, Thomas Browne rejected all reports of human metamorphosis except that of Lot’s wife.72

Transformations involving non-human animals were, of course, quite another matter. Belief that flies, bees, wasps, scorpions, and the like were generated from animal carcasses seems to have been widespread in the ancient world; we return to this idea in subsequent chapters. Such beliefs persisted undiminished during the Middle Ages. Petrus Bonus, for example, wrote in about 1330 ce that “nature generates frogs in the clouds, or by means of putrefaction in dust moistened with rain, by the ultimate disposition of kindred substances . . . . The decomposition of a basilisk generates scorpions. In the dead body of a calf are generated bees, wasps in the carcass of an ass, beetles in the flesh of a horse, and locusts in that of a mule.”73 Even in Linnæus’s time, many Norwegians apparently believed that rats fell from the clouds.74

Plants could undergo transformations as well. Theophrastus discussed— sceptically except for wheat and barley—the apparently common belief that crop plants could degenerate into weeds. In the Second century ce, Galen’s father, Nicon,