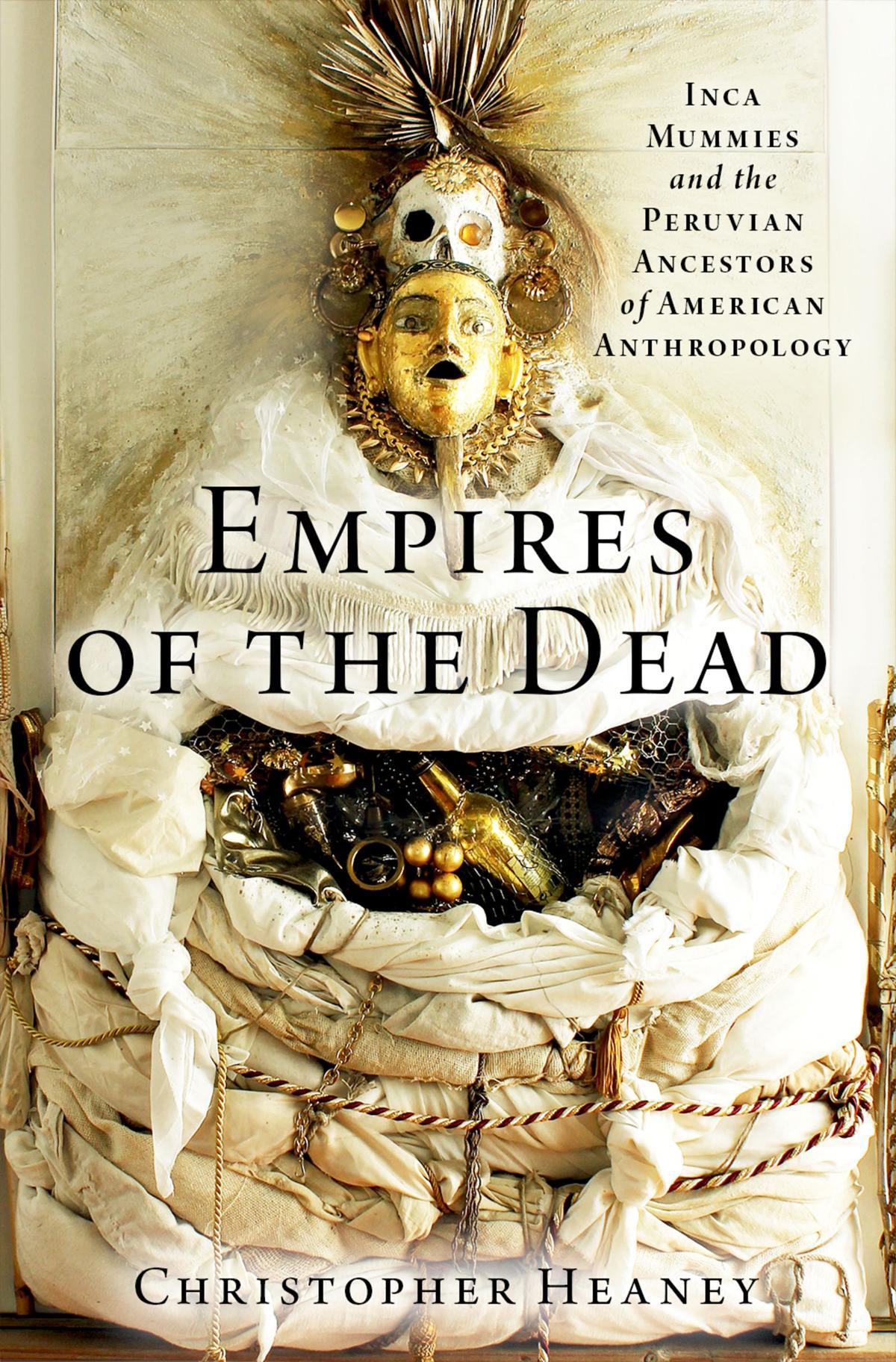

Empires of the Dead: Inca Mummies and the Peruvian Ancestors of American Anthropology Christopher Heaney

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/empires-of-the-dead-inca-mummies-and-the-peruvian -ancestors-of-american-anthropology-christopher-heaney/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

East Asians in the League of Nations: Actors, Empires and Regions in Early Global Politics Christopher R. Hughes

https://ebookmass.com/product/east-asians-in-the-league-ofnations-actors-empires-and-regions-in-early-global-politicschristopher-r-hughes/

The Archaeology of Ancestors: Death, Memory, and Veneration 1st Edition Hill Hageman

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-archaeology-of-ancestors-deathmemory-and-veneration-1st-edition-hill-hageman/

Peruvian Cinema of the Twenty-First Century: Dynamic and Unstable Grounds 1st ed. Edition Cynthia Vich

https://ebookmass.com/product/peruvian-cinema-of-the-twentyfirst-century-dynamic-and-unstable-grounds-1st-ed-editioncynthia-vich/

Skepticism and American Faith: from the Revolution to the Civil War Christopher Grasso

https://ebookmass.com/product/skepticism-and-american-faith-fromthe-revolution-to-the-civil-war-christopher-grasso/

American Poly Christopher M. Gleason

https://ebookmass.com/product/american-poly-christopher-mgleason/

The Rise of Empires: The Political Economy of Innovation 1st ed. Edition Sangaralingam Ramesh

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-rise-of-empires-the-politicaleconomy-of-innovation-1st-ed-edition-sangaralingam-ramesh/

The Relevance of Metaphor: Emily Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop and Seamus Heaney 1st Edition Josie O'Donoghue

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-relevance-of-metaphor-emilydickinson-elizabeth-bishop-and-seamus-heaney-1st-edition-josieodonoghue/

Handbook of Metal Injection Molding 2nd Edition Heaney

https://ebookmass.com/product/handbook-of-metal-injectionmolding-2nd-edition-heaney/

The Primacy of Metaphysics Christopher Peacocke

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-primacy-of-metaphysicschristopher-peacocke/

Empires of the Dead

Inca Mummies andthe Peruvian Ancestors of American Anthropology

Christopher Heaney

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

Portions of the introduction and Chapter 5 are adapted from “Skull Walls: The Peruvian Dead and the Remains of Entanglement,” AmericanHistoricalReview, vol. 127, no. 3 (September, 2022), pp. 1071–1101.Portions of Chapter 3 are adapted from “How to Make an Inca Mummy: Andean Embalming, Peruvian Science, and the Collection of Empire,” Isis: AJournaloftheHistoryofScienceSociety, vol, 109, no. 1 (March, 2018), pp. 1–27. © 2018

The History of Science Society. Portions of Chapter 6 are inspired by “Fair Necropolis: the Peruvian Dead, the first American Ph.D. in Anthropology, and the World’s Columbian Exposition of Chicago, 1893,” HistoryofAnthropologyReview41 (2017). http://histanthro.org/notes/fair-necropolis/. Portions of Chapter 8 are adapted from “Seeing Like an Inca: Julio C. Tello, Indigenous Archaeology, and Pre-Columbian Trepanation in Peru.” IndigenousVisions:RediscoveringtheWorldofFranzBoas, eds. Ned Blackhawk and Isaiah Wilner, 344–377. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Heaney, Christopher, author. Title: Empires of the dead : Inca mummies and the Peruvian ancestors of American anthropology / Christopher Heaney. Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2023004932 (print) | LCCN 2023004933 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780197542552 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197542576 (epub) | ISBN 9780197542583

Subjects: LCSH: Anthropological museums and collections—United States. | National Museum of Natural History (U.S.). Department of Anthropology—Exhibitions. | Ethnoscience—Peru. | Trephining—Peru—History. | Ethnology--Peru.

Classification: LCC GN35 .H43 2023 (print) | LCC GN35 (ebook) | DDC 301.074—dc23/eng/20230518

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023004932

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023004933

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197542552.001.0001

For Hannah, Curtis, and Jack

Andean people have not spent their history closed up in an impossible museum.

Alberto Flores Galindo, In Searchofan Inca (1986)

CONTENTS

ANoteonImages

ANoteonOrthography

Introduction: Death’s Heads: The Peruvian Ancestors at the Smithsonian

PART 1: OPENING, 1525–1795

1. Curing Incas: Andean Lifeways and the Pre-Hispanic Imperial Dead

2. Embalming Incas: Huayna Capac’s Yllapa and the Spanish Collection of Empire

3. Mummifying Incas: Colonial Grave-Opening and the Racialization of Ancient Peru

PART 2: EXPORTING, 1780–1893

4. Trading Incas: San Martín’s Mummy and the Peruvian Independence of the Andean Dead

5. Mismeasuring Incas: Samuel George Morton and the American School of Peruvian Skull Science

6. Mining Incas: The Peruvian Necropolis at the World’s Fairs

PART 3: HEALING, 1863–1965

7. Trepanning Incas: Ancient Peruvian Surgery and American Anthropology’s Monroe Doctrine

8. Decapitating Incas: Julio César Tello and Peruvian Anthropology’s Healing

9. The Three Burials of Julio César Tello: Or, Skull Walls Revisited

Epilogue: Afterlives: Museums of the American Inca

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

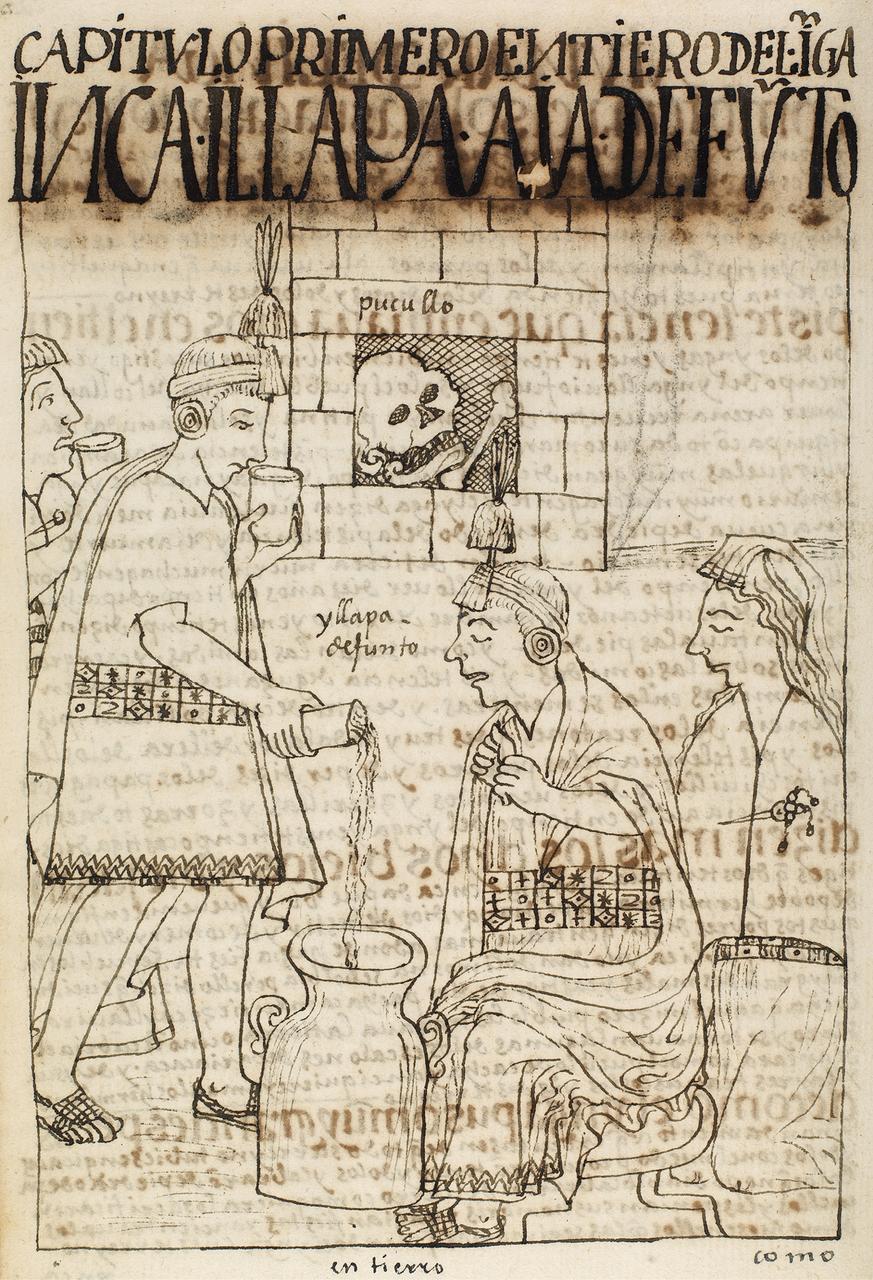

A NOTE ON IMAGES

The earliest known visual depictions of Inca and Andean ancestors were made by an Indigenous chronicler named Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, who in 1616 sent his richly illustrated manuscript Elprimer nveva corónica I bven gobierno to the king of Spain. That Guaman Poma wanted the king to see the mummified or skeletal forms of the Incas and their Andean subjects is clear. Guaman Poma was not Inca. He was a descendant of Chinchasuyu lords of the Inca empire, Tawantinsuyu, and had previously painted several illustrations for Basque friar Martín de Murúa’s HistoriageneraldelPiru. While Murúa commissioned portraits of the Inca emperors for his Historia, there were no depictions of actual Andean ancestors. With Elprimernveva corónica, Guaman Poma rectified that absence. Among his goals was the depiction of the Andean dead’s variety, showing that differences in their physical preservation demanded nuance when it came to understanding the many ways that Inca and Andean peoples loved, cured, venerated, and feared the unbreathing relatives they kept close.

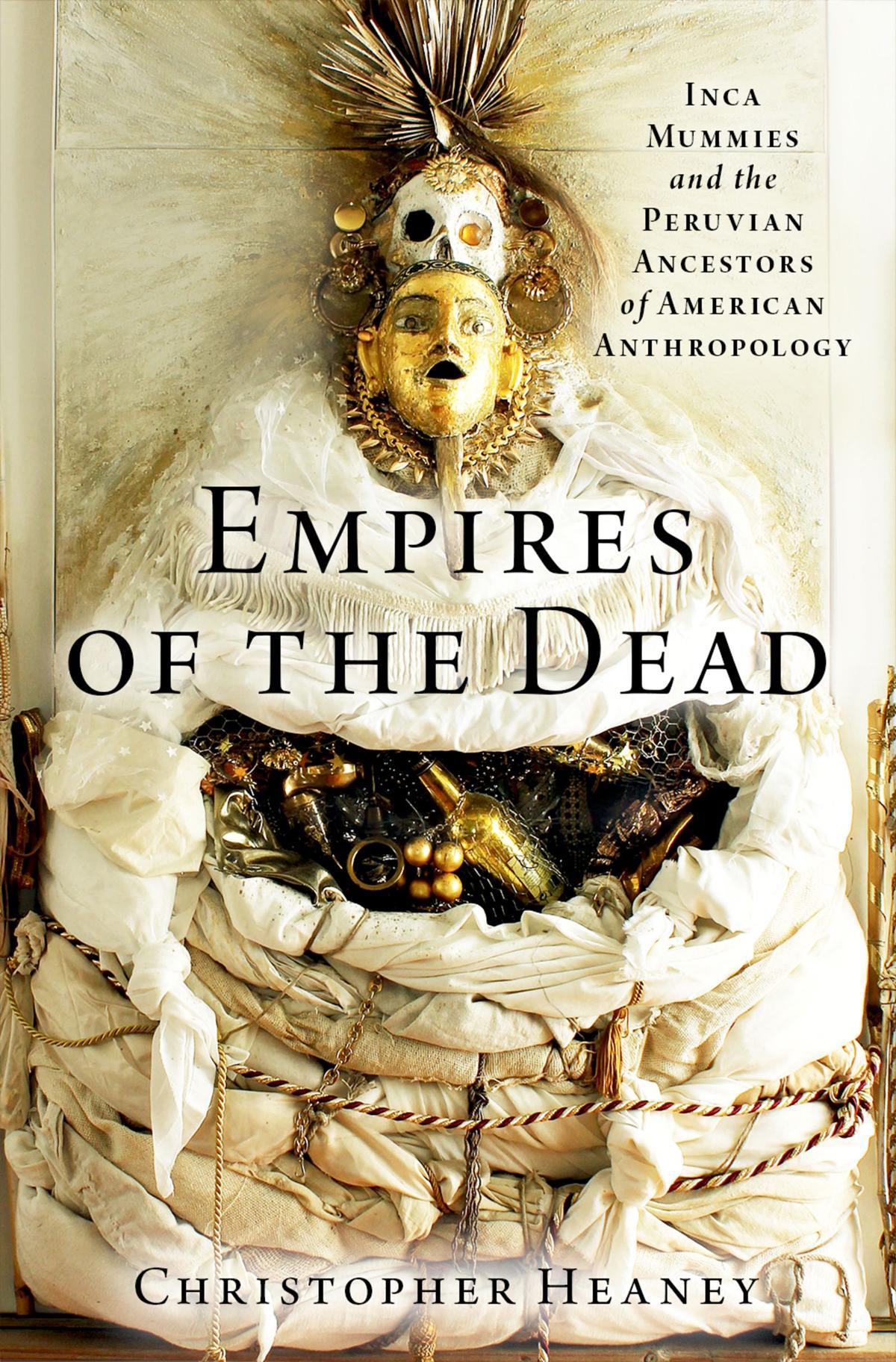

This book contains numerous visual depictions of Inca and Andean remains, beginning with its cover, Yachaya, a mixed-media sculpture by the Cuban-German artist Nancy Torres that uses paint, textiles, glass, wood, feathers, plaster, straw, wire mesh, and objects over canvas to evoke an ancestor under colonial assault. Most of the other images in this book likewise outstrip anything that Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala intended for his royal audience of one. The mortuary culture of Inca and Andean Tawantinsuyu—where the unbreathing could look upon the living, and the living might sometimes look back—is a far cry from the nineteenth- and twentieth-century museum cultures in which non-Andean curators and anthropologists unwrapped “Inca mummies” and de-fleshed

Andean crania to depict them as racialized “specimens” of wider human history. Many of these later images and photographs are—to my eyes, at least—shattering. They have contributed to a culture of displaying non-European human remains still with us today, a practice that Indigenous North Americans, in particular, have worked to end. Yet Andean ancestors are often excepted from that care. Nearly every week, I receive news alerts for articles illustrated by new photos of Andean mummies, a dead made “scientific” by their supposed distance from the present, Europe, and the United States. Some of these depictions are so artistic that they encourage casual viewers to forget that their subjects were disinterred.

Others, like Yachaya, a sculpture that Nancy Torres has shown in Peru, Cuba, and Germany, make that violence impossible to ignore. I chose Torres’s meditation on Spanish looting of Andean bodies and wealth for this book’s cover because, as Torres intended, viewers who deny the history of European assaults upon Indigenous bodies and sovereignty lose the privilege of looking away. It also inducts those viewers into a visual culture, in Peru and the Andes, that remains far more comfortable with their display. To that end, this book selectively reproduces other depictions of Andean ancestors within its pages not to titillate, but to explain why four centuries of looting Andean ancestors, skulls, and bones made them foundational to the field of human research known today as anthropology—and why thousands reached museums around the world, where they have been used to represent all human history and have inspired some of its most existential art .

This forgotten visual genealogy of Inca and Andean mummies and ancestors matters for two reasons. First, it demands that we see what museums often instruct us to unsee: their role as gathering places of the supposedly dead and inert, human and nonhuman, from whom science is made. And second, because it reminds us of how looking can also become an act of care. This book shows why the belief that looking upon the remains of the dead disrepects them, in and out of scientific settings, is not universal. For Guaman Poma, his ancestors, and some of his modern Andean intellectual heirs—some of them Peruvian anthropologists—seeing and being

seen by a dead that embodied history, or healed the sick, induced respect. It could also be a demand for recognition—that ancestors be appreciated for their differing cultures of mourning, science, and care. Museums have sometimes used that fact to justify their display of Andean ancestors still sought by their original communities. But other professionals are returning that dead, working with communities to store or display them respectfully, or, in Peru, are considering places within and outside of museums for their mourning.

All of this is to say that we cannot ignore the fact that museums collected and displayed Andean ancestors in a way that extended violence. But limiting that story to violence is to ignore how the culture of their display across time and space meant radically different things. By selectively including some of these Inca and Andean ancestors in these pages, this book hopes to extend their challenging gaze. But it is also an archive of their care. Engaging with their animacy—seeing them see us if only in the pages of a book—broadens our understanding of their loss and recognizes their possibility of healing.

A NOTE ON ORTHOGRAPHY

Because this is also a book about how embodied Andean ancestors and knowledges were inscribed, an explanation of how it uses words is in order. When Spain’s conquistadors invaded the Incas’ realms, they met peoples who conveyed history in many ways, none of which were written on fragile paper. The Spanish praised the “Inca historians” nevertheless, singling out the khipukamayuq, the keepers of khipus, the knotted and pendant cords that kept track of labor and tribute obligations, but also the lives and accomplishments of the Inca rulers. By 1559 the Spanish seem to have confiscated some of the most important historical khipus, transcribing some of the stories recounted by their khipukamayuqs. But Castilian ears and the Latin alphabet were a poor match for Quechua (and other Andean languages like Aymara and Puquina), and the transmission of their knowledges to Europe further garbled and misrepresented the details and names of Inca history. Republished sources can reference a supposed tyrant named “Atabalica” or “Atabalipa”—actually the ruler Atahualpa or Atahuallpa, the Sapa Inka (Peerless Inca) whose murder by the Spanish lastingly colored his reputation.

Historians and anthropologists have worked to complicate those reputations, but imperfect transcriptions and orthographies—the spellings of words—remain a kind of colonization, as Andean linguists have noted for half a century. The Spanish inscribed the Inca capital as Cuzco, for example, while more faithful modern transcription render the Inka capital as Qosko or Cusco. Removing Spanish influences from written Andean languages has allowed their nuanced inflections of time, space, and knowledge to glow. Even the term “Inca Empire” has been questioned: to the Incas, their realm was Tawantinsuyu, “The Four Parts Bound Together.”

For these reasons, this book uses modern spellings for key Inca and Andean figures and terms. However, because it is a work of history written mostly from pre-1970 texts, it preserves original spellings in primary sources, and carries some—like Inca or Cuzco— into the text itself. While unsatisfying as a solution, it allows readers searching for more conventional terms to engage with their history.

Empires of the Dead

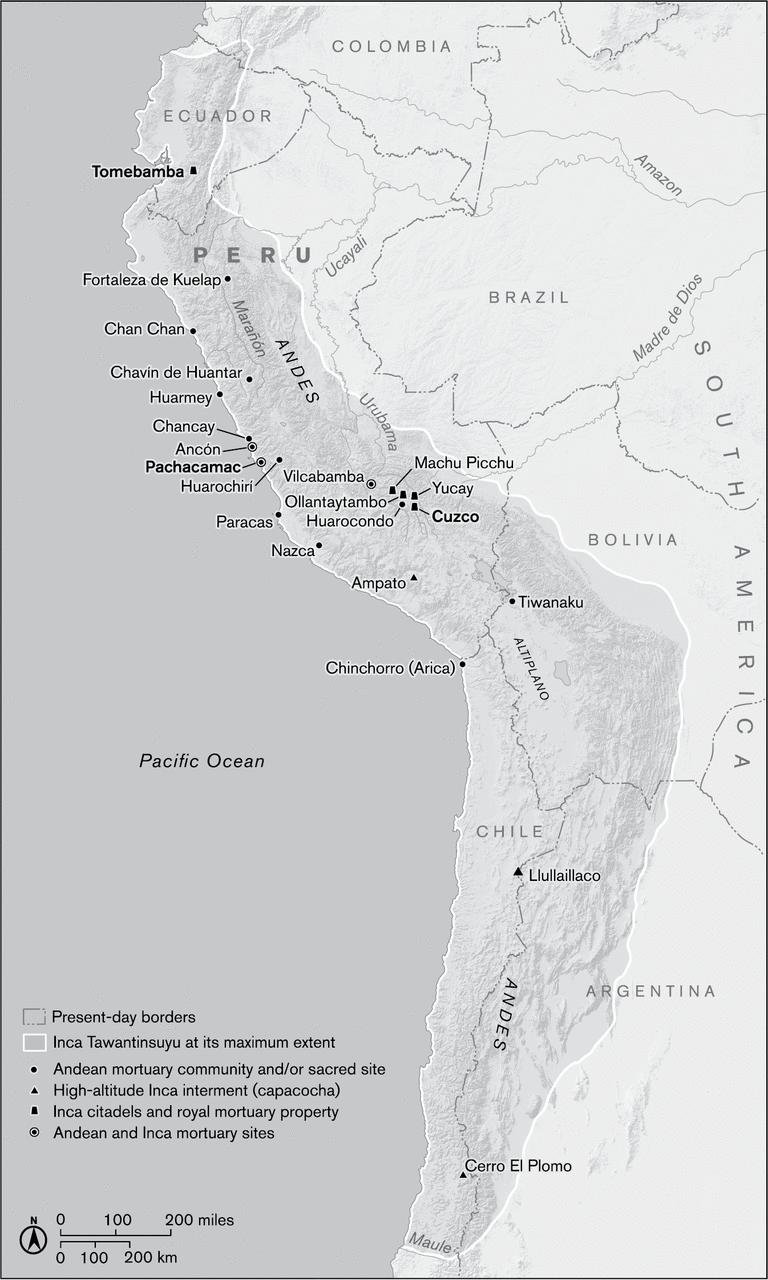

Pre-Hispanic mortuary landscapes of the Andes and Tawantinsuyu, the Inca empire, mentioned in Empires ofthe Dead. Map by Ben Pease.

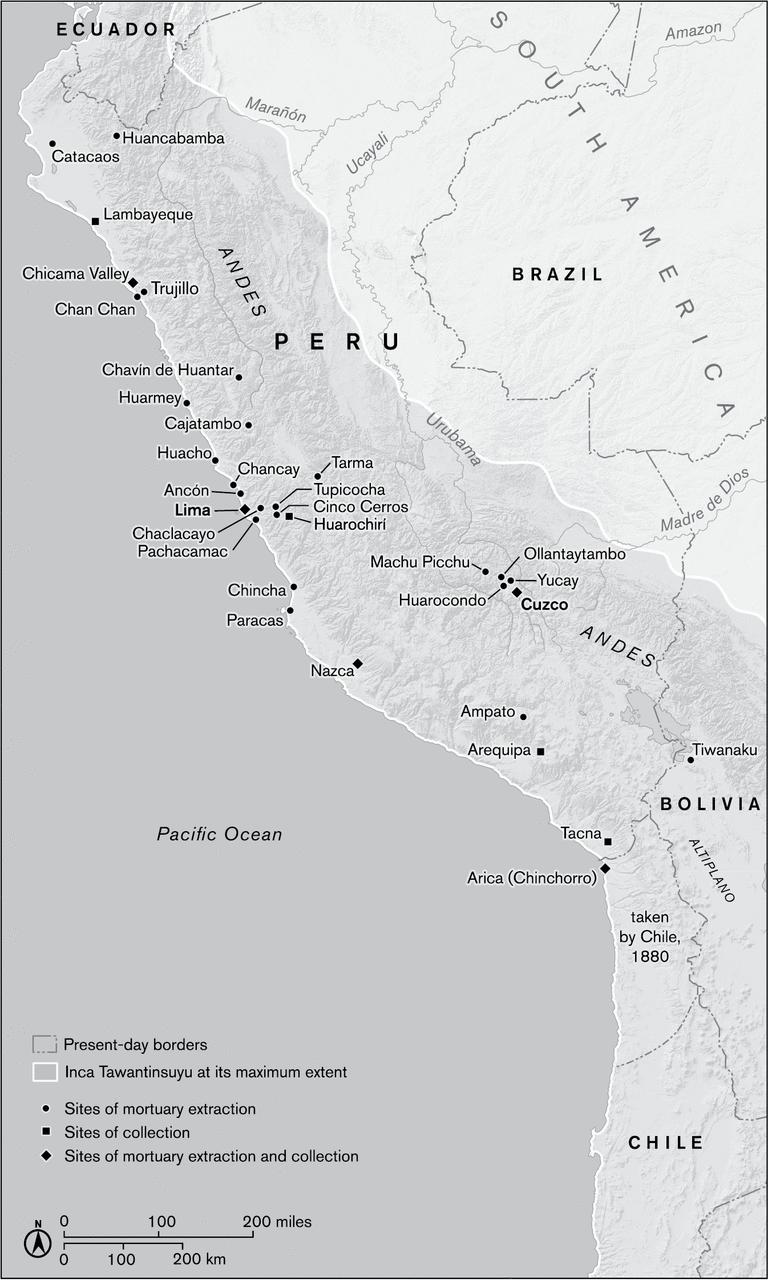

Landscape of extraction of pre-Hispanic Andean human remains and their collection in Peru, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Map by Ben Pease.

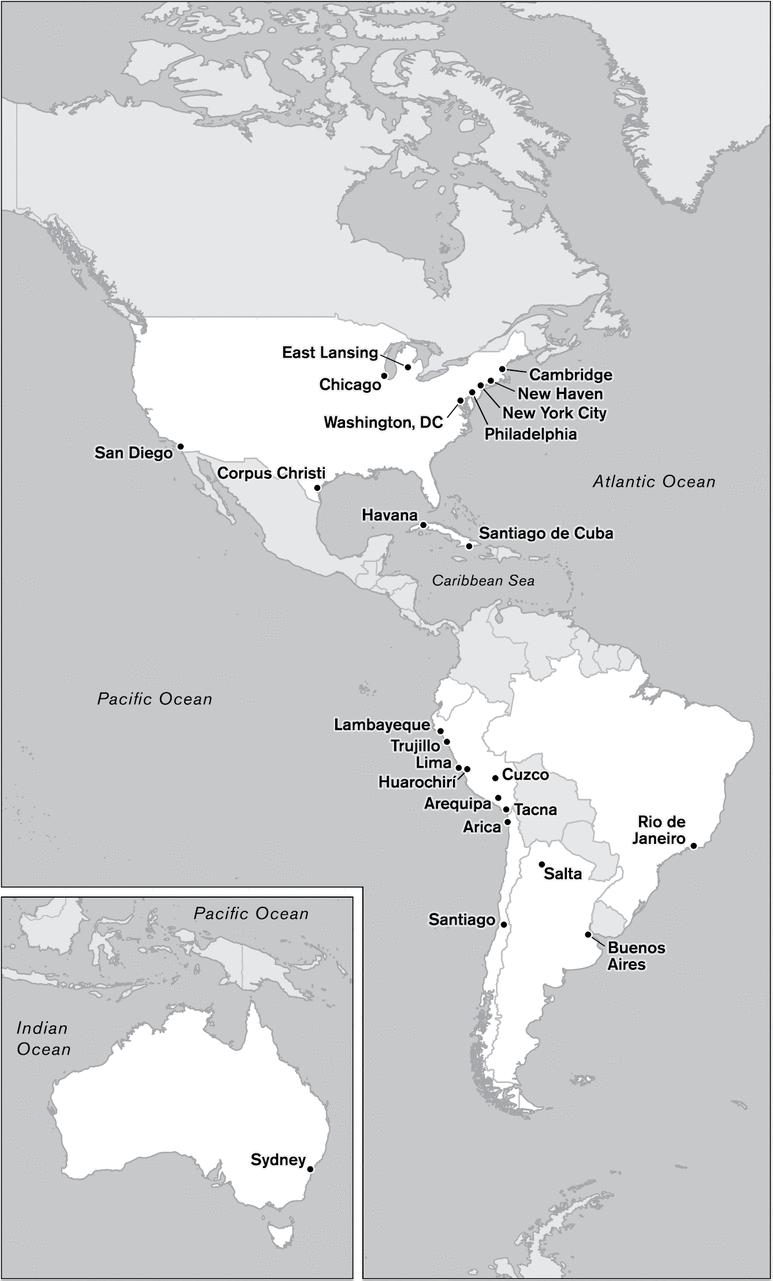

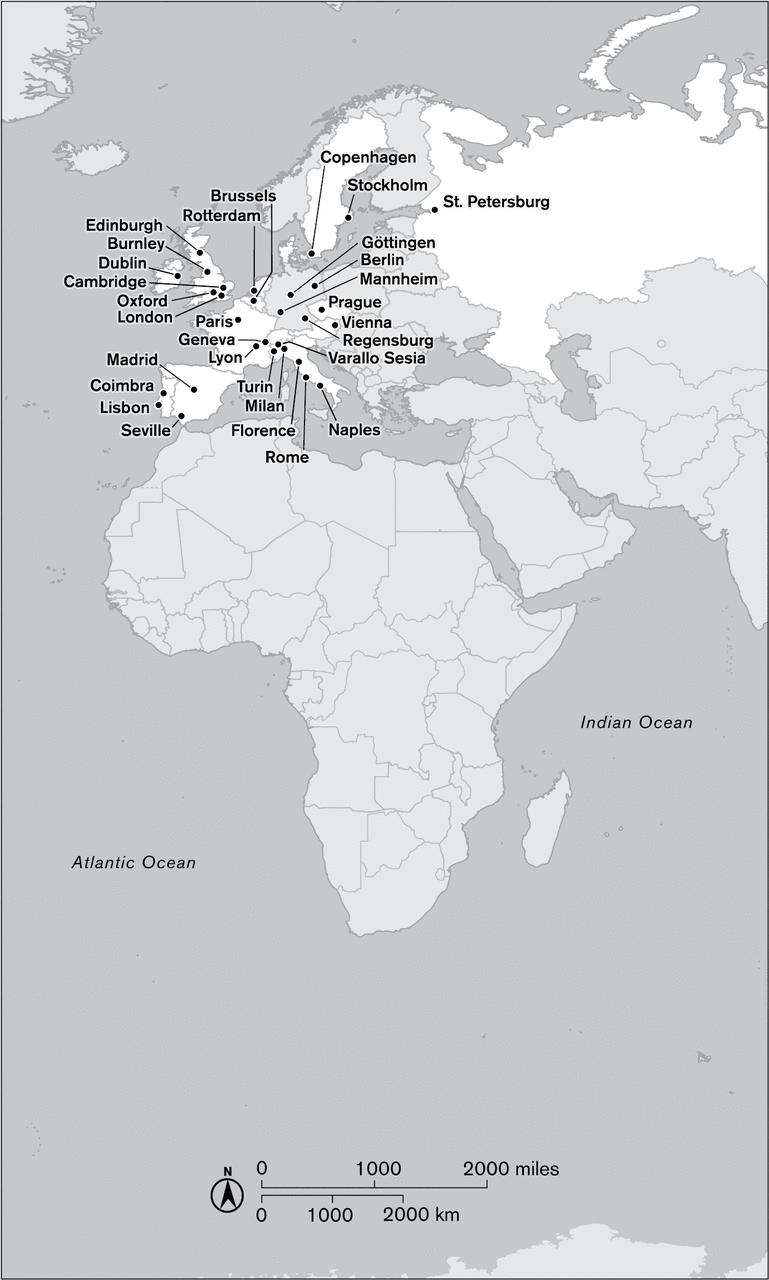

Global destinations of Andean ancestors and human remains, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as mentioned in Empires ofthe Dead. Map by Ben Pease.

Introduction

Death’s Heads: The Peruvian Ancestors at the Smithsonian

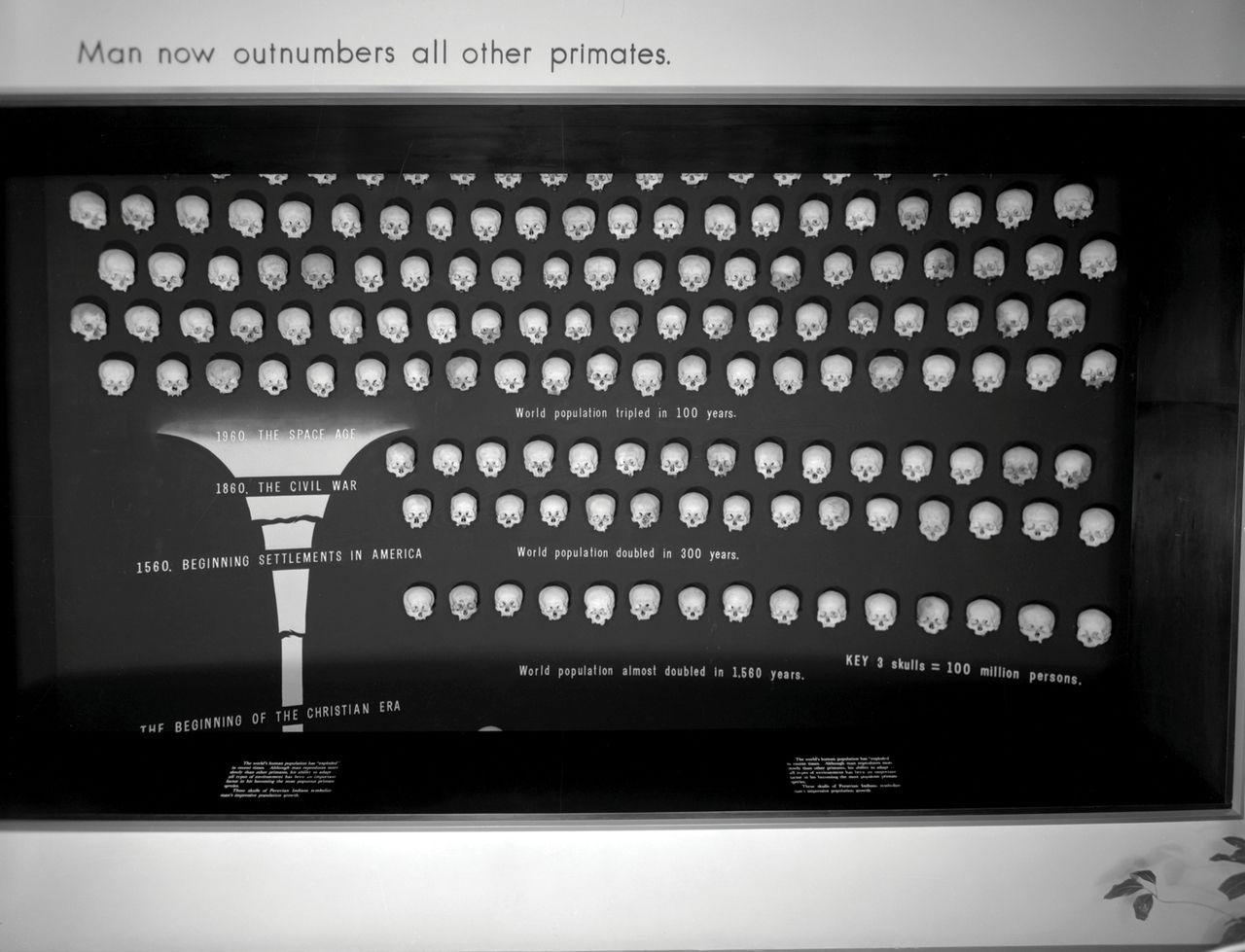

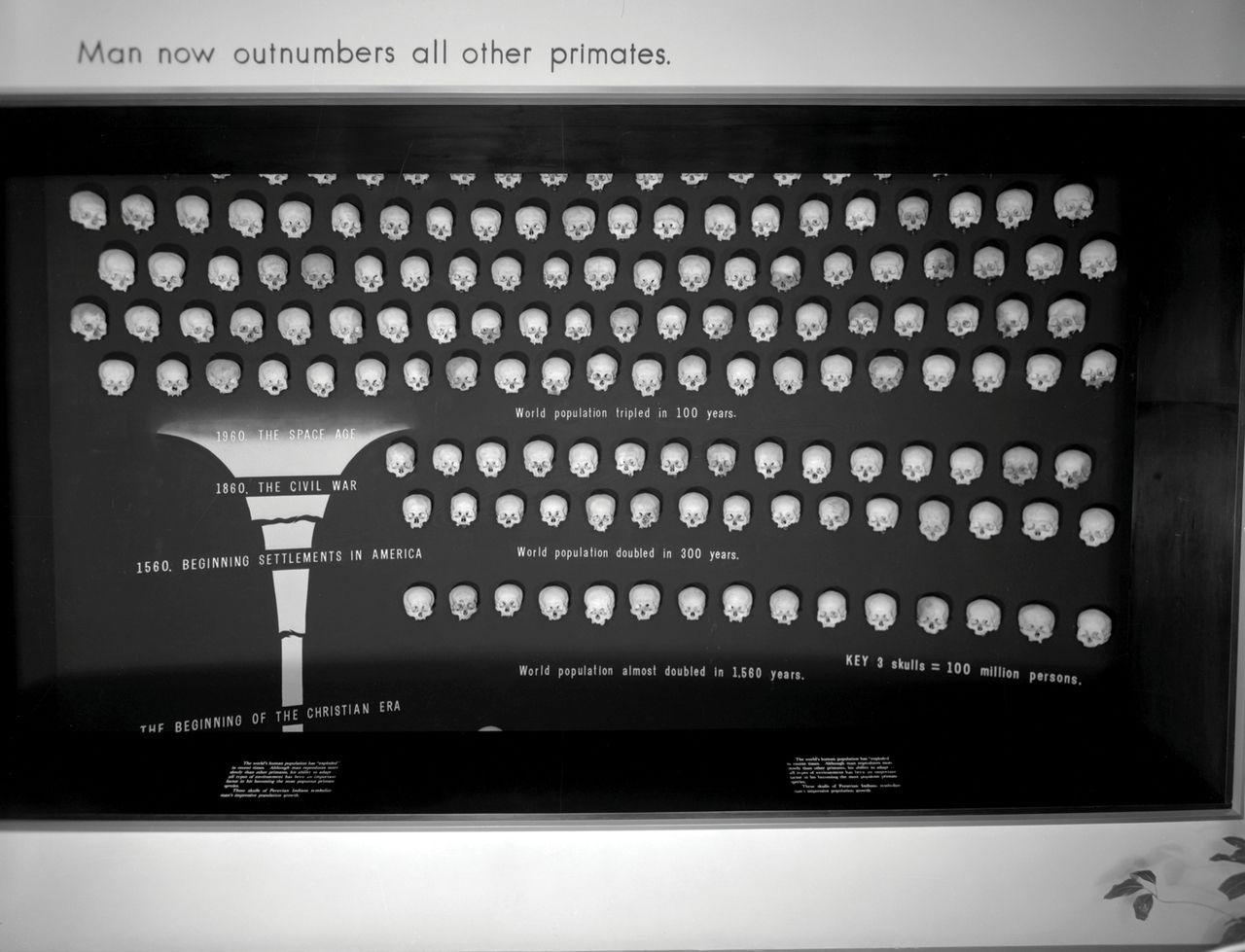

When the Hall of Physical Anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution (SI) opened in Washington, DC, in 1965, its visitors met a wall of florid death: the skulls of 160 “Ancient Peruvians,” arranged like a lopsided mushroom cloud. The anthropologists at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) had fixed them to the wall to visualize how the “world’s human population has literally ‘exploded’ in historic times.” Every three crania represented 100 million people. At the bottom, nine skulls represented the 300 million people believed to constitute the world’s human population in AD 1, the “Beginning of the Christian Era.” The row above was fifteen skulls long, the 500 million people supposed alive in 1560, which the exhibit’s designers labeled “Beginning Settlements in America.” Thirty more crania in two rows represented the 1 billion people estimated for 1860, the eve of “The Civil War.” And at the top, a thunderhead of 106 skulls represented the 3.5 billion human beings alive in 1960, “The Space Age” (see plate 1). According to the Washington Post, the new hall’s “overall theme—man’s supremacy over all other primates—[was] eerily demonstrated by the grinning skulls of the ancient Peruvians.” This dual display of mortality and fertility was also a monument to a sweepingly American history of humanity, made legible via the accumulation, measurement, and concentration of the dead. Its designers called it the “Skull Wall.”1

Plate 1 The “Skull Wall” in the Smithsonian Institution’s first permanent Hall of Physical Anthropology, ca. 1965, in which 160 Andean crania embodied the population growth of all humanity. This photograph cuts off the bottom row of nine skulls, which were only visible when a museumgoer approached the display. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image No. MNH-1646A.

The Post’s reporter acknowledged the obvious questions. Why had these “sun-bleached Peruvian Indian skulls” come from South America to the Smithsonian? And why had the anthropologists chosen them, of all the many other peoples the institution had collected, to stand for the biggest possible thing they could say about the recent history of humanity? On this point, museum director T. Dale Stewart—also the Smithsonian’s senior physical anthropologist—was both forthcoming and vague. “The death’s heads,” the reporter was told, “were found about 60 years ago after

being uncovered by gold miners,” but there was “no particular significance in their use.”

“We used Peruvian skulls,” Stewart explained, “because we had so many of them.”

Stewart wasn’t wrong. Skulls and bones from “ancient Peru” had long been the largest historical population at the Smithsonian—itself the largest scientific collection of skeletal remains in the world. When the institution’s founding ethnological collection was first catalogued, the first eleven objects listed were three Peruvian mummies and eight Peruvian skulls. The early Smithsonian otherwise avoided the collection of human remains—ceding that work to the Army Medical Museum—but Stewart’s predecessor Aleš Hrdlička in the 1910s more than doubled the institution’s collection of human remains, mostly due to his addition of more than ten thousand “ancient Peruvian” crania, bones, and mummified remains.2 Their use in the Skull Wall reflected that fact, given that to do otherwise would deplete more crania, proportionally, from groups less well represented in the research collection.3

The use of Andean remains in the hall’s other displays, though, suggested that their importance at the Smithsonian went beyond numbers. The exhibit employed bones from the Peruvian Andes to show how anthropologists read skeletons for evidence of fractures, explaining that “Diseases of prehistoric man are sometimes recorded in skeletons.” In another display, Andean crania demonstrated how diverse Indigenous Americans used bundle boards and bandages to modify the shape of their children’s crania to embody and display group belonging. Peru’s dead were also a prime example of physical anthropologists’ understanding of the mutability of human “forms,” the word the exhibit used instead of “race.” One display illustrated how populations’ phenotypes—skin color, height, cranial size and shape—changed over time owing to individual variability and the prevalence of some traits over others. It did so by highlighting the only human skeletal feature named after an ethnic group: “The ‘Inca’ bone,” or os incae—an interparietal bone in the skull whose “high frequency among Inca Indians of Peru”—was the product of

gradual changes and convergences in a population’s traits. The larger cranial variety of Peruvians was then used to assert that “generalized Asiatic mongoloids” became the “first Americans” after crossing the Bering Land Bridge, when their physical characteristics diverged.4

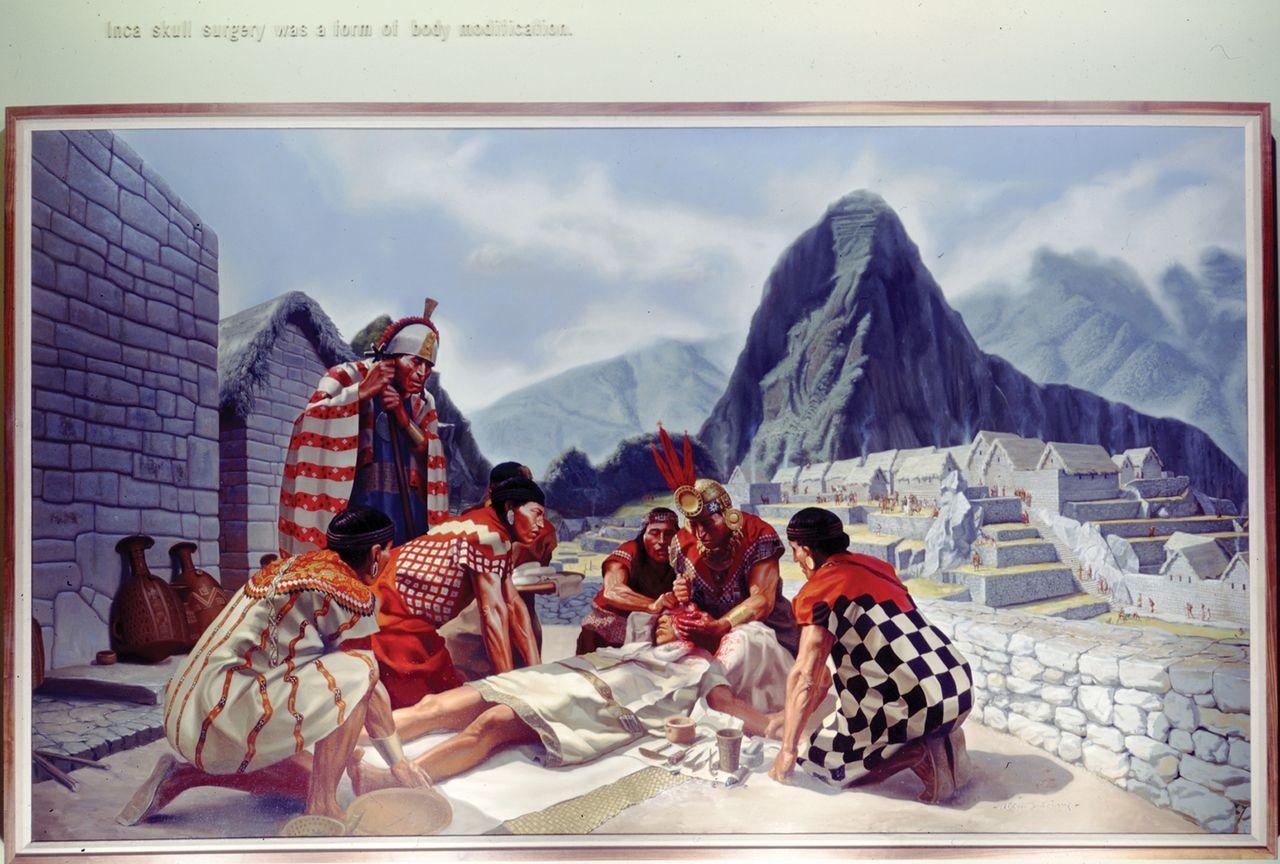

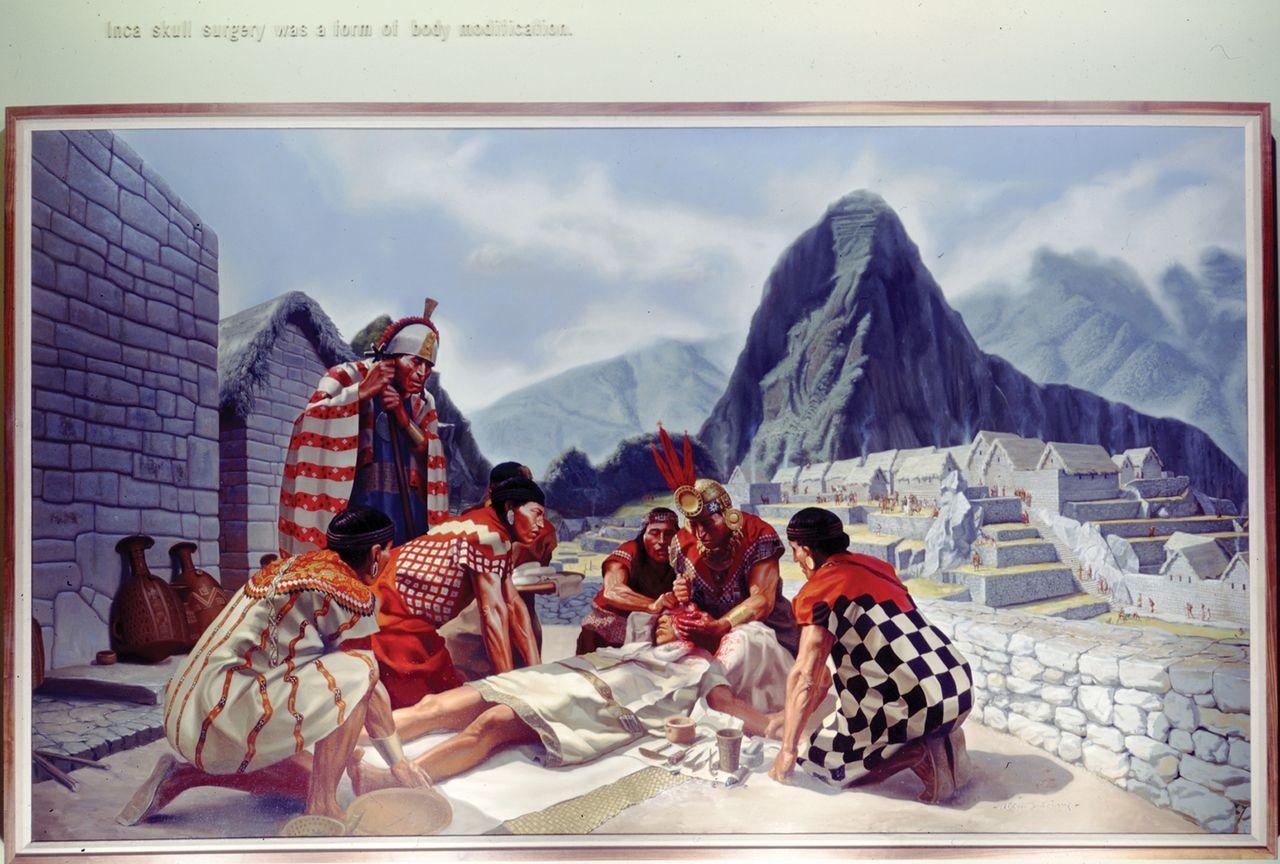

The hall’s two most memorable displays after the Skull Wall, however, suggested that the ancient Peruvians were not just an illustrative branch of American anthropology; they were part of its trunk. Unit 20 was the most jaw-dropping. It explained that “Ancient Peruvians excelled in Skull Surgery.” Western doctors called this operation “trepanation,” which relieved pressure on an individual’s brain by cutting away sections of crania. In the Andes, the operation addressed fractures caused by everyday life and war. A case in Unit 20 thus presented the heavy metal and stone weapons that gave Andean healers so many skulls to heal. It also displayed “surgical implements” they used to lift the scalp and cut away damaged bone. Skulls with five, even seven holes made over an individual’s lifetime suggested a pre-Hispanic Andean skill in this high-risk maneuver unrivaled worldwide until the late nineteenth century.5 It was all dramatized in a massive walnut-frame painting by a Connecticut artist named Alton S. Tobey. The Smithsonian had sent Tobey to South America to study trepanation’s most famed Peruvian practitioners, the Incas, whose empire, Tawantinsuyu, spanned the Andes before the Spanish invaded in 1532. The resulting painting depicted an Inca surgeon at work, opening a patient’s bloodsmeared skull at the Inca royal estate of Huayna Picchu, today known as Machu Picchu. This was Indigenous Americans’ most ambitious medical technique, framed by their most iconic architectural site (see plate 2).6

Plate 2 For at least two thousand years, Andean healers practiced trepanation, a skull surgery in which the world’s most successful practitioners prior to the late nineteenth century belonged to the Inca Empire. This photograph depicts the exhibition of Alton Tobey’s “Inca trephination mural” in the first Hall of Physical Anthropology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History after 1965. Tobey’s painting depicts the Incas trepanning at famous Machu Picchu, though the display qualifies its medical achievement by suggesting “Inca skull surgery was a form of bodily modification.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image No. 75-2104.

Softened by Inca surgeons’ ability to extend their patients’ lives, visitors gazed upon Andean peoples’ accomplishments at curing death itself. A display on “Mummies” was included “partly to appease the public’s morbid curiosity and partly to explain how bodies get preserved” after death “due to various causes,” the exhibit’s script explained. Visitors likely expected to find the ancient Egyptian lying supine. But they first saw a “Peruvian,” a woman from the coastal Chancay culture whose pose challenged expectations of what mummies were supposed to be. She sat upright, wrapped in a textile, her arms tucked beneath her head. The display made no

mention of what her preservation meant: how Andean peoples had mummified their ancestors and children to extend their social and sacred being for eight millennia, which made the South Americans’ artificial “mummies” the world’s oldest (see plate 3). But more than any other display in the exhibit, this seated Andean individual reminded museumgoers that every other skull in the hall was once similarly embodied.