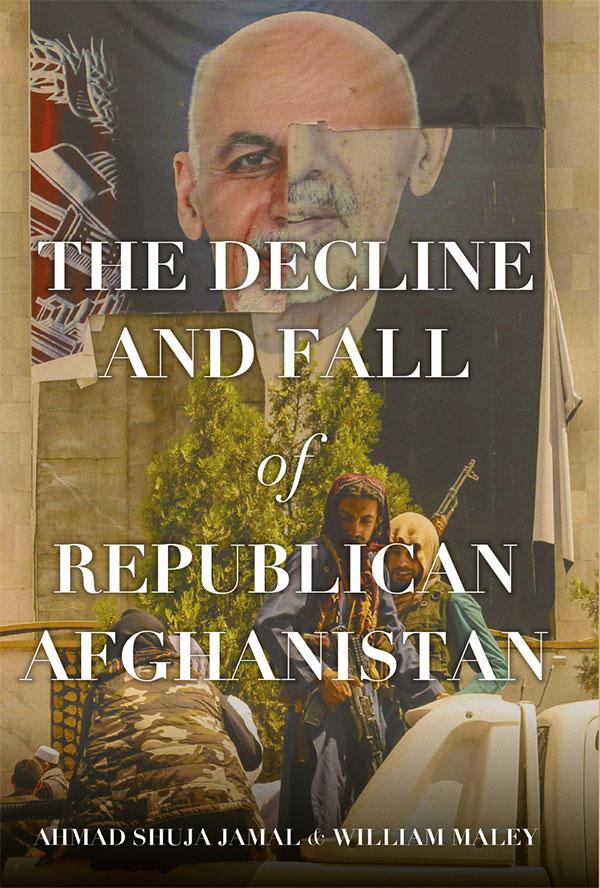

AHMAD SHUJA JAMAL

WILLIAM MALEY

The Decline and Fall of Republican Afghanistan

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2023 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 1LA

© Ahmad Shuja Jamal and William Maley, 2023

All rights reserved.

The right of Ahmad Shuja Jamal and William Maley to be identified as the authors of this publication is asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787388017

www.hurstpublishers.com

Dedicated to those courageous and steadfast members of the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces, and their families, who in the face of tremendous odds gave so much to Afghanistan and received so little in return.

Dedicated to the Afghans and their friends who shared the dream of a republican and democratic Afghanistan and worked towards it in their own ways.

Dedicated to the Afghans for whom hope died on 15 August 2021. And dedicated to the Afghans resisting the Taliban’s tyranny and keeping the nation’s aspirations for a more just country alive.

Acknowledgements

Map

Preface

1. Introduction

2. The Problem of Political Legitimacy

3. Pathologies of Aid and Development

4. Problems of Insurgency

5. Political Leadership

6. Diplomatic Disaster

7. Cascade Effects and the Unravelling of Military Power

8. The Final Days of Kabul

9. Conclusion

Afterword: On Betrayal

Notes Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their deep appreciation to Michael Dwyer and his colleagues at Hurst Publishers for supporting the writing of this book. For literally decades, no publisher has done more to foster serious analysis of Afghanistan and its travails.

Ahmad Shuja Jamal would like to thank the individuals who spoke to us in the research for this book and offered other assistance. He would also like to thank his co-author, William Maley, for the valuable opportunity to work together. And, of course, he offers special thanks to Homa for her constant love and companionship that sustained him in difficult times.

William Maley owes a special debt to his co-author Ahmad Shuja Jamal, not just for the intellectual engagement that led to this book, but for a decade of convivial friendship. He would also like to make special mention of several networks of researchers and officials studying Afghanistan that came together after 15 August 2021, both face-to-face and online, to canvass the complexities surrounding the decline and fall of Republican Afghanistan: these included Ali Yawar Adili, Waheed Ahmad, Shaharzad Akbar, Farkhonda Akbari, Muzafar Ali, Nasir Andisha, Michael Barry, Nematullah Bizhan, Srinjoy Bose, Wolfgang Danspeckgruber, Abbas Farasoo, Robert P. Finn, Niamatullah Ibrahimi, Haroro J. Ingram, Namatullah Kadrie, Joseph Mohr, Kobra Moradi, Nishank Motwani, Dipali Mukhopadhyay, Rani Mullen, Arif Saba, Mahmoud Saikal, David Savage, Susanne Schmeidl, Timor Sharan, Fred Smith, Barbara Stapleton, Safiullah Taye and Wahidullah Waissi, as well as others who would prefer not

to be named. The diverse views expressed by these observers have been very helpful in shaping the arguments in this book.

The map in this book is one freely supplied by ontheworldmap.com: see https://ontheworldmap.com/afghanistan/map-ofafghanistan.jpg.

Ahmad Shuja Jamal and William Maley

Brisbane and Canberra, November 2022

PREFACE

On 28 June 1919, statesmen gathered in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles for the signing of a momentous treaty, the product of months of discussion between the victorious powers of the First World War.¹ Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles affirmed Germany’s responsibility for the war, and under threat of invasion, Germany, which had not been part of the negotiations, was forced to sign. Some observers, such as the economist John Maynard Keynes, excoriated the treaty for its lack of magnanimity.² Others saw it as too lenient to Germany. French Marshal Ferdinand Foch ominously warned: ‘This is not Peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years’.³

Just over twenty years later, on 10 May 1940, forces of Nazi Germany smashed their way into Germany’s western neighbours— the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg—putting an end to the ‘phony war’ that had persisted uneasily since the outbreak of the Second World War following the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. Three days later, German forces crossed the river Meuse, and on 15 May, they broke through the French lines at Sedan. As an eminent historian put it, ‘Nothing stood between the German armies and the French capital’.⁴ The following day, the newly appointed British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, flew with a small team to Paris for consultations with their French counterparts. Churchill asked the French commander, General Gamelin, ‘Where is the strategic reserve?’ ‘Aucune’—‘there is none’—Gamelin replied. Churchill later wrote ‘I admit this was one of the greatest surprises I have had in my life’.⁵ Six days into the war in the west, the end for the French was in sight. A remarkable operation from 27 May to 4 June evacuated 338,226 soldiers from Dunkirk in northern France and transported them to England; most were from the British

Expeditionary Force (BEF), but roughly 110,000 of them were French.⁶ But as Churchill himself remarked, wars are not won by evacuations,⁷ and on 10 June, the French government left Paris, paving the way for German troops to enter the capital on 14 June. Four dark years were to pass before the liberation of Paris in August 1944.⁸ And debate persists to this day as to exactly what factors— military failure, poor leadership, weak institutions, social decay under the Third Republic, sheer complacency—led to the collapse.

Eighty years later, something eerily similar happened in another part of the world, in Afghanistan. In 1937, the French diplomat René Dollot had written ‘L’Afghanistan est la Suisse de l’Asie’—‘Afghanistan is the Switzerland of Asia’.⁹ No one seemed disposed to make such a claim in 2020 or 2021. In 2001, following the 11 September 2001 attacks by Al-Qaeda on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon, and the overthrow by the United States of the radical Taliban regime in Afghanistan that had hosted Al-Qaeda, another conference of victors was held, this time in Germany, in the city of Bonn. The Taliban, scorned and scattered, were not invited to participate. The Bonn Conference culminated in an agreement signed on 5 December 2001 between non-Taliban Afghan political actors that set out a pathway towards a new political system.¹⁰ The process was not perfect, but it offered some hope for Afghans after decades of conflict and misery.

Nearly twenty years later, everything unravelled. After years of insurgent attacks by Taliban fighters given sanctuary in neighbouring Pakistan, Afghanistan’s long-time backer the United States, under the leadership of the most erratic and unpredictable president in its history, Donald Trump, struck an agreement with the Taliban on 29 February 2020 entitled ‘Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan’ (Mowafeqatnamah-e awardan-e solh ba Afghanistan).¹¹ Negotiated and signed by Dr Zalmay Khalilzad, who in September 2018 had

been appointed as ‘Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation’, the fine print revealed it to be an exit agreement for the United States. The Afghan government had been excluded from the negotiations that led to it, and as US forces were drawn down, Taliban attacks on Afghan targets escalated sharply. Peace was nowhere in sight. The end came in July–August 2021. The Taliban, after seizing customs posts at Afghanistan’s borders, surged unexpectedly into the north of the country, taking over key cities such as Herat and Mazar-e Sharif. Resistance to the Taliban began to crumble, and at an accelerating pace. With the capital Kabul wide open to attack, President Ashraf Ghani fled the country on 15 August with a few members of his intimate circle, his reputation in ruins.¹² The government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan collapsed, and the Taliban occupied Kabul. Scenes of horror emerged as desperate Afghans sought to leave the country by air before the United States terminated its evacuation flights at the end of the month. For Afghans who had been inspired by the vision of a modern, pluralistic and globalised society, life had become dark indeed.

Just as debate has swirled in France and beyond over what factors led to the collapse of Republican France in 1940, a multiplicity of explanations might be offered to shed light on the collapse of Republican Afghanistan in 2021.¹³ This book sets out our account of what happened and why.

INTRODUCTION

Afghanistan is a landlocked country in West Asia. Within its boundaries are both wide plains and rugged mountains, with the Hindukush, an offshoot of the Himalayas, running from the northeast to the central west. Its present shape and form were not dictated from on high through a settlement between powers, as occurred in Europe with the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, the Congress of Vienna of 1815, or the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Rather, it owed much to the creeping expansion of powers in the neighbourhood of what is now Afghanistan, most importantly Russia and Britain. Russia, between 1550 and 1700, had ‘acquired on the average 35,000 square kilometres—an area equivalent to modern Holland—every year for 150 consecutive years’,¹ and its influence weighed heavily on the Muslim khanates that remained in Central Asia.² Britain had entrenched its position in India, especially after the East India Company was replaced as ruler by the British Raj in 1858. It broadly suited the interests of each of these powers to have a ‘buffer state’ in the region. Anglo-Russian negotiations in 1873 and 1887 largely fixed Afghanistan’s northern border,³ and its eastern boundary with British India was demarcated in 1893 by a British official, Sir Mortimer Durand.⁴ But that said, while Afghanistan was subject to colonial influences, it was never colonised, and recent scholarship suggests Afghan players exercised greater agency than has often been realised.⁵ Even before the mid-twentieth century, it was a recognised state, a member of the League of Nations from 27 September 1934, and of the United Nations from 19 November 1946.

Afghanistan is sometimes seen as a small country, but the Afghan population, estimated in 2021 to be 38,835,428, is larger than the populations of Canada, Poland, Malaysia, Australia, Syria and many European countries.⁶ The bulk of the population is based in villages and small towns, and only the capital Kabul, with an estimated 2021 population of 4,335,770, exceeds 1 million residents.⁷ It is also a young population; according to official data from 1 June 2020, some 24,559,262 Afghans, or 74.6 per cent of the total population, were estimated to be under the age of 30.⁸ The population is of kaleidoscopic social complexity. While Dari and Pashto are the two most widely spoken languages, multiple languages are used by different communities, reflecting the diverse range of ethnic groups —Pushtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks and many others—to be found within Afghanistan’s borders.⁹ While the overwhelming majority of the population is made up of Muslims, there are significant distinctions between members of the Sunni Muslim majority and the substantial Shiite Muslim minority.¹⁰ The complex life-experiences of women in Afghanistan have often differed greatly from the equally complex experiences of their male counterparts,¹¹ not least because of the persistence of patriarchal norms in many parts of the country. But it is dangerous to over-generalise about social dynamics in Afghanistan, for two reasons. First, people tend to live simultaneously in a multiplicity of social worlds, navigating their complexities as a matter of everyday living. Second, the norms and expectations that are seen as defining ‘cultures’ are themselves malleable and elastic in the face of factors such as educational opportunity and globalisation.¹² It is perilous to assume that Afghanistan in the twenty-first century is basically the same as it was in the nineteenth or twentieth centuries.

Political theorists have used the metaphor of a social contract to explain the emergence of the instrumentalities of the state, but in

the real world it is little more than a metaphor. Historically, the state has emerged through a diverse range of processes, including the use of violence to establish a monopoly of centralised force,¹³ especially in the hands of what the economist Mancur Olson labelled the ‘stationary bandit’.¹⁴ But the emergence of a state and state authority has often been a prolonged process, gradual rather than instantaneous, and involving bargaining, exchange, and patronage as well as pure coercion. While studies of the Afghan state often date it from the times of Ahmad Shah Durrani (1747–72), serious scholarship suggests that this is better seen as one step in a more elaborate process, with critical events coming both before and after Ahmad Shah’s reign.¹⁵ Migdal has identified state functions as being to ‘penetrate society, regulate social relationships, extract resources, and appropriate or use resources in determined ways’.¹⁶ He has also sought to distinguish different parts of the state: these he calls the trenches, consisting of ‘the officials who must execute state directives directly in the face of possibly strong societal resistance’; the dispersed field offices, the ‘regional and local bodies that rework and organize state policies and directives for local consumption, or even formulate and implement wholly local policies’; the agency’s central offices, the ‘nerve centers where national policies are formulated and enacted and where resources for implementation are marshaled’; and the commanding heights, the ‘pinnacle of the state’ where the ‘top executive leadership’ is to be found.¹⁷ Afghanistan before an April 1978 communist coup experienced a number of different regime types: monarchy from 1747 to 1973 and a republic from 1973 to 1978. But throughout this period, the state had a somewhat ramshackle character, with varying capacities in different parts of the state.¹⁸

The analysis of Afghan affairs has often suffered from serious oversimplification, to which a range of tropes have contributed. Recent times have seen the popular press flooded with expressions purporting to sum up Afghanistan in just a few words. ‘Graveyard of

empires’ is one. Another is ‘tribal society’.¹⁹ Such expressions, together with the ubiquitous ‘forever wars’ and ‘failed state’,²⁰ do not assist in illuminating Afghanistan’s complexities. While there is no doubt that networks based on lineage have been and are politically important in some parts of Afghanistan, it is worth recalling Elizabeth Leake’s reminder that ‘Colonial officials across empires constructed “tribes” to explain local relationships, to create leadership hierarchies, and to establish “stable, enduring, genealogically and culturally coherent units” that were easier to understand and thereby govern’.²¹ The deeper lesson here is that Afghanistan is a dynamic space. Its peoples have a much richer history of engagement with the wider world than is often recognised,²² and internally, relationships wax and wane in importance depending upon a number of factors, ranging from broad sociological developments such as globalisation and urbanisation to very specific calculations that individuals may make in the light of the incentives that they confront, which themselves can change for diverse reasons. As a result, ‘essentialising’ metaphors that depict a remote, timeless, fixed, unchanging (and often highly romanticised) Afghanistan need to be treated with the greatest degree of caution.

Thepost-1978context

On 27 April 1978, a coup d’état mounted by supporters of the Marxist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) overthrew President Mohammad Daoud, a former Prime Minister who himself had overthrown the monarchy, and his cousin Zahir Shah, in a palace coup in July 1973.²³ It was the 1978 coup that was the ultimate trigger for virtually all the disasters that have befallen Afghanistan since that date. The coup did not reflect any mass demand for revolutionary change; rather it reflected stark divisions within Afghanistan’s political elite, divisions which in turn owed much