Praise for The OxfordHistory ofthe World

‘When a renowned academic publisher such as Oxford University Press gathers well-known (mainly British and American) historians to write a history of the whole world, one can expect a cross between the highest condition, light and metaphorical language… and this is exactly what this volume delivers.’

Matthias Middell, Comparativ

‘To say that The OxfordHistory ofthe World is a monumental undertaking is something of an understatement. In just over 400 pages some of the world’s most noted historians come together to tell the story of human history, from its first breath to the modern age.…The result is a triumph.…As accessible as it is well-researched, it really is a joy to read and will satisfy anyone who wants to delve deeper into the history of the world.’

AllAbout History

‘Extraordinary…with accessible essays of such originality.…’

Richard Drayton, Times Literary Supplement

‘Some books are admirable because of their sheer scope and ambition, and this overview of the entirety of the human story fits firmly within that category.’

History Revealed

‘A handy compendium of some of the major moments and periods of transformation in human history, set in a global context.’

Lucia Marchini, Minerva

‘Condensing the story of humanity’s 200,000 year tenure on Earth into 450 pages could be an act of hubris or the result of orderly—yet imaginative— minds making connections across centuries and continents. The Oxford History of the World is more the latter…a pleasure to read with many thought-provoking passages.’

David Luhrssen, ShepherdExpress

‘A truly remarkable book.’

‘Brilliant and provocative.’

Richard Lofthouse, QuadMagazine

Art Eyewitness

ListofMaps

ListofTables

Introduction

Part 1

Children of the Ice

ThePeoplingoftheWorldandtheBeginningsofCultural Divergence,c.200,000toc.12,000yearsago

Humanity from the Ice: The Emergence and Spread of an Adaptive Species

CliveGamble

The Mind in the Ice: Art and Thought before Agriculture

FelipeFernández-Armesto

Part 2

Of Mud and Metal

DivergentCulturesfromtheEmergenceofAgriculturetothe ‘CrisisoftheBronzeAge’,c.10,000 BCE–c.1,000 BCE

Into a Warming World

MartinJones

The Farmers’ Empires: Climax and Crises in Agrarian States and Cities

FelipeFernández-Armesto

Part 3

The Oscillations of Empires

Fromthe‘DarkAge’oftheEarlyFirstMillennium BCE totheMidFourteenthCentury CE

Material Life: Bronze Age Crisis to the Black Death

JohnBrooke

Intellectual Traditions: Philosophy, Science, Religion, and the Arts, 500 BCE–1350 CE

DavidNorthrup

Growth: Social and Political Organizations, 1000 BCE–1350 CE

IanMorris

The Climatic Reversal

ExpansionandInnovationamidPlagueandColdfromtheMidFourteenthtotheEarlyNineteenthCenturies CE

A Converging World: Economic and Ecological Encounters, 1350–1815

DavidNorthrup

Renaissances, Reformations, and Mental Revolutions: Intellect and Arts in the Early Modern World

ManuelLucenaGiraldo

Connected by Emotions and Experiences: Monarchs, Merchants, Mercenaries, and Migrants in the Early Modern World

AnjanaSingh

The Great Acceleration AcceleratingChangeinaWarmingWorld,c.1815–c.2008

The Anthropocene Epoch: The Background to Two Transformative Centuries

DavidChristian

The Modern World and its Demons: Ideology and After in Arts, Letters, and Thought, 1815–2008

PaoloLucaBernardini

13. Politics and Society in the Kaleidoscope of Change: Relationships, Institutions, and Conflicts from the Beginnings of Western Hegemony to American Supremacy

JeremyBlack

Epilogue

FurtherReading

PictureAcknowledgements

Index

List of Maps

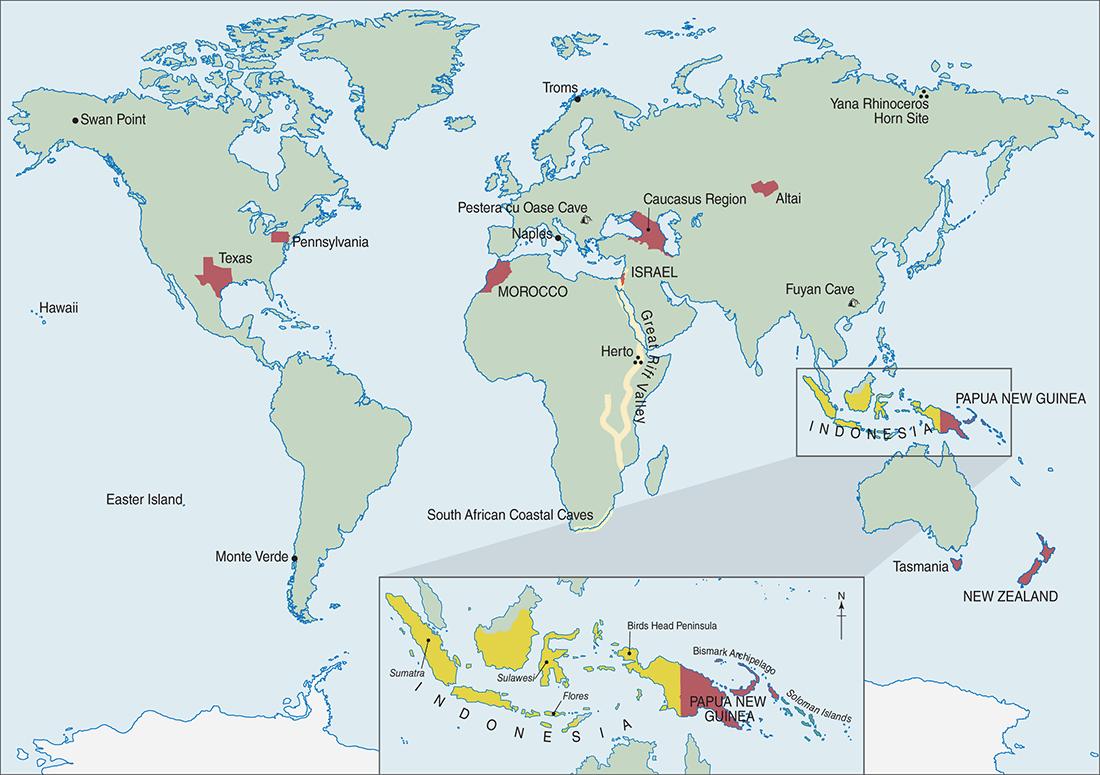

1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 2.1 3.1 5.1 6.1 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 11.1

Places named in the chapter.

Biodiversity hotspots.

‘Factories’ where new animals repeatedly evolved.

Hominin and human settlement.

Peter Forster’s genetic map.

Places named in the chapter.

Nicolai Vavilov’s ‘Centres of Diversity’.

Places named in the chapter.

Buddhist Expansion to about 1300 CE.

(a) and (b) Places named in the chapter.

Global distribution of social and political organizations in 1000 BCE.

Global distribution of social and political organizations in 175 CE.

Global distribution of social and political organizations in 1350.

Major agricultural expansions, 1000 BCE to 1350 CE.

Places named in the chapter.

List of Tables

1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 11.1 11.2

The anatomical criteria used by Chris Stringer and Peter Andrews to define a modern human.

A ten-point checklist of traits of fully modern behaviour detectable in the archaeological record and beginning 50,000–40,000 years ago.

The timeframe for the appearance of Homo sapiens, modern humans.

A comparison of three hominin species.

The effect of different falls in sea level on land area and, in particular, the palaeocontinents of Sunda and Sahul.

Statistics on human history in the Holocene & Anthropocene Epochs.

Chronology of power sources from 1800–2000, and corresponding power delivered.

Introduction

In 1928, Philo Vance, the hero of TheBishopMurderCase, imagined a hypothetical creature who can ‘…traverse all worlds at once with infinite velocity, so that he is able to behold all human history at a glance. From…Alpha Centauri he can see the earth as it was four years ago; from the Milky Way he can see it as it was 4,000 years ago, and he can also choose a point in space where he can witness the ice-age and the present day simultaneously!’

This book will not give the reader quite so privileged a perspective, but our aim is to see the world whole with objectivity hard to attain for humans trapped in our own history—to review the changes that really have taken place all over the planet, not just in parts of it—and present them in a tiny compass, such as a galactic observer might behold from an immense distance in time and space.

The erudition of Vance (the fictional detective Willard Wright created under his pseudonym, S. S. Van Dine) was affected and his science absurd. He was right, however, about the effects of perspective on historical vision. The technique of shifting to an imaginary perspective can transform the way we see our past. Even small variants in viewpoint can disclose discoveries. When painting a still life, for instance, Cézanne used to switch between vantage points, seeking to combine fleeting perceptions in a single composition. He made the curves of the rim of a bowl of apples look as if they can never meet. He painted strangely distended melons, because he wanted to capture the way the fruit seems to change shape from different angles. In his assemblages of odds and ends each object assumes its own perspective. He painted the same subjects over and over again, because with every fresh look you see

something new, and every retrospect leaves you dissatisfied with the obvious imperfections of partial vision.

The past is like a painting by Cézanne—or like a sculpture in the round, the reality of which no single viewpoint can disclose. Objective reality (that which looks the same by agreement among all honest observers) lies somewhere out there, remote and difficult to find—except perhaps by encompassing all possible subjective perspectives. When we shift vantage point, we get a new glimpse, and try to fit it in when we return to our canvas. To put it another way, Clio is a muse we spy bathing between leaves. Each time we dodge and slip in and out of different points of view, a little more is revealed.

We know the advantages of multiple viewpoints from everyday experience. ‘Try to see it my way, try to see it your way’, sang the Beatles. We have to incorporate perspectives of protagonists and victims to reconstruct a crime. We need testimony from many witnesses to reproduce the flicker and glimmer of events. To understand whole societies, we need to know what it feels like to live in them at every level of power and wealth. To understand cultures, we need to set them in context and know what their neighbours think or thought of them. To grasp a core, we peel away at outer layers. But the past is ungraspable: we see it best when we add context, just as the bull’s eye makes a clearer target when the outer rings define it and draw in the eye.

The most spectacular and objective point of view I can imagine is that of Philo Vance’s ‘hypothetical homunculus,’ who sees the planet whole and views its complete past conspectually. The question for a global historian is, ‘What would history look like to that galactic observer in the cosmic crow’s nest?’ I suspect that Vance’s creature might need prompting even to mention a species as puny and, so far, short-lived as humankind. Grasses, or foxes, or protozoa, or viruses might seem more interesting: they all have, from a biological point of view, features at least as conspicuous as those of humans— vast environmental reach, stunning adaptability, remarkable duration. But one human feature would surely be conspicuous from

any perspective: the ways in which we differ from all other species in our hectic, kaleidoscopic experience of culture, and the fact that we have more of it, of more various kinds, than any other creature. Humans have a dazzling array of contrasting ways of behaving, whereas other species—though many of them resemble us closely in bodies and genes—encompass a comparatively tiny range of differences. We have vastly more lifeways and foodways, social structures and political systems, means of representing and communicating, rites and religions than any other cultural animal— even the great apes who are most like us. That variety is the subject-matter of this book.

Over the last sixty years or so, observers have identified culture among many primate species and claimed it for many others. Human cultures, however, are different: by comparison with other species, we are strangely unstable. Communities in all cultural species become differentiated, as they change in contrasting and inconsistent ways, but the processes involved happen incalculably more often, with a perplexingly greater range of variation, among humans than among any other animals: human cultures register the constant series of changes called ‘history’. They self-transform, diverge, and multiply with bewildering and apparently—now and for most of the recent past accelerating speed. They vary, radically and rapidly, from time to time and place to place.

This book is an attempt to clasp the whole of our variety, or as much of it as possible, by seeing the themes that link it, the stories that overarch it, and the pathways through it. Some people think the big narrative, which encompasses just about the whole of history, is of progress or providence or increasing complexity, or cyclical change or dialectical conflict, or evolution, or thermodynamics, or some other irreversible trend. The galactic observer, however, would surely notice subtler, less predictable, but more compelling, tales. The contributors to TheOxfordHistoryoftheWorldmuster between them five ways of tracing a path through the data. Call them masternarratives if you like, or meta-narratives if you prefer. But the storylines are objectively verifiable and can be followed in this book.

The first story is of divergence and convergence—how ways of life multiply and meet. Divergence—the single word with which, I think, the galactic observer would summarize our story—is surely dominant. It denotes how the limited, stable culture of Homo sapiens, at our species’ first appearance in the archaeological record, scattered and self-transformed to cover the tremendous range of divergent ways of life with which we now surprise each other and infest every inhabitable environment on the planet. We started as a small species, with a uniform way of life, in a restricted environment in East Africa, where all humans behaved in much the same way, foraging for the same foods; relating to each other with a single set of conventions of deference and dominance; deploying the same technologies; using, as far as we know, the same means of communication; studying the same sky; imagining—as best we can guess—the same gods; probably submitting, like other primates, to the rule of the alpha male, but venerating the magic of women’s bodies that are uniquely regenerative and uniquely attuned to the rhythms of nature. As migrant groups adjusted to new environments and lost touch with each other—so the authors of Part 1 show—they developed contrasting traditions and distinctive ways of behaving, thinking, organizing families and communities, representing the world, relating to each other and to their environments, and worshipping their peculiar deities.

Until about 12,000 years ago or so, they all had similar economies —getting their sustenance by hunting and gathering. But climate change induced a variety of strategies, with some people opting to continue traditional ways of life, others adopting herding or tillage: in Part 2, Martin Jones tells that story in Chapter 3. Farming accelerated every kind of cultural change, as Chapter 4 and Chapter 7 make clear. So, as John Brooke’s contribution in Chapter 5 shows, did adjustments to the dynamics of elements of the environment beyond human control—the lurches of climate, the convulsions of the Earth, the bewildering evolution of the microbes that sometimes sustain, sometimes rupture, the ecologies of which we are part. Culture has, moreover, a dynamic of its own, partly because human

imaginations are irrepressible, continually re-picturing the world and inspiring us to realize our visions, and partly because every change— especially in some areas of culture, such as science, technology, and art—unlocks new possibilities. The results are visible around us.

Tracing the divergence of humans, however, is not enough. For almost the whole length of the story, countervailing trends, which we can call convergence, have been going on, too. David Northrup’s work in this book broaches the theme, which increasingly dominates the chapters from Part 4 onwards, little by little mirroring the way cultures established or re-established contact, exchanged lifeways and ideas, and grew more like each other as time went on. In convergence, sundered cultures meet at the edges of their explorations or at tense frontiers of the expansion of their territories, or in the adventures of traders or missionaries or migrants or warriors. They exchange thoughts and technologies along with people, goods, and blows.

Convergence and divergence are more than compatible: they are complementary because exchanges of culture introduce novelties, stimulate innovations, and precipitate every other kind of change. For most of the human past, divergence outstripped convergence: cultures, that is to say, became more and more diverse—more and more unlike each other—despite mutual encountering and learning. Isolation kept most of them apart for long spells. Uncrossable oceans, daunting deserts, and mountains deterred, interrupted, or prevented potentially transforming contacts. At a contested moment, however—the contributors to this book cannot agree about how or when to fix it—the balance swung away from divergence, so that convergence became more conspicuous. Over the last half millennium, convergence has been increasingly intense. Exploration has ended the isolation of almost every human community. Global trade has brought everyone’s culture in reach of just about everyone else’s, and global communications have made the process instantaneous. A fairly long period of Western global hegemony seems to have privileged the transmission of culture from Europe and North America to the rest of the world, ‘globalizing’, as we now

say, Western styles in art, politics, and economics. Divergence has not been halted—merely overshadowed. Under the shell of globalization, old differences persist and new ones incubate. Some are precious, others perilous.

As divergence and convergence wind and unwind through this book, they tangle with another thread. In Chapter 7, Ian Morris calls it ‘growth’: accelerating change, which, with some hesitancies and reversals, has perplexed and baffled people in every age, but now seems to have speeded up uncontrollably; the sometimes faltering but ever self-reassertive increase of population, production, and consumption; ever more intensive concentrations of people— successively in foragers’ settlements, agrarian villages, growing cities, mega-conurbations; increasingly populous and unwieldy polities, from chieftaincies to states to empires to superstates.

In some ways, as is apparent from David Christian in Chapter 11, all types of acceleration are measurable in terms of consumption of energy. To some extent, nature supplied the energy that accelerating human activities required, by way of global warming. Today we tend to think of global warming as the result of human profligacy with fuel, creating the greenhouse effect. But climate on Earth depends above all on the sun—a star too potent and distant to respond to humans’ petty doings—and irregularities in the tilt and orbit of the planet, which are beyond our power to influence. Except for a brief blip—a ‘little ice age’ of diminished temperatures in the period covered by Part 3 of this book and some minor fluctuations at other times, the incidence and results of which the reader will find chronicled in Parts 1 and 3, natural events beyond human reach have been warming the planet for about 20,000 years or so.

Meanwhile, three great revolutions, in which humans have been involved as active participants, have further boosted our access to energy: first, the switch from finding food to producing it—from foraging to farming. As Martin Jones’s chapter makes clear, the switch was not solely or entirely the product of human ingenuity; nor was it a fluke (as some enquirers, including Darwin, used to think), but rather a long process in response to climate change. It was a

mutual adjustment in which plants and creatures, including humans, established relationships of reciprocal dependence: humans could not survive without species that, without humans, could not exist. Insofar as human agency procured it, the inception of farming was a conservative revolution, produced by people who wanted to stick to their traditional food stocks, but had to find new ways to guarantee supply. The result was a stunning interruption of the normal pattern of evolution: for the first time, new species came into being by ‘unnatural selection’, crafted for human purposes by sorting, transplanting, nurturing, and hybridization.

Evolution got warped a second time in a process described in Chapter 8 and Chapter 10: the ‘ecological revolution’ that started when long-range voyages began regularly to cross the oceans of the world from the sixteenth century onwards. In consequence, life forms that had been diverging on mutually separate and increasingly distant continents, during about 150 million years of continental drift, began to be swapped, partly as a result of conscious human efforts to multiply access to a variety of foods, and partly as an unintended consequence of biota—weeds, pests, microbes—hitching, as it were, a ride with trading, exploring, conquering, or migrating human populations. The previously divergent course of evolution from continent to continent yielded to a new, convergent pattern. Today, as a result, climate for climate, we find the same life forms all over the world.

Not all the consequences favoured humankind. The disease environment worsened for populations that became suddenly exposed to unfamiliar bacteria and viruses; fortunately for our species, however, as we see in Chapter 8 and Chapter 11 by David Northrup and David Christian, respectively, other changes in the microbial world counteracted the negative effects, as, in response to global warming, some of the most deadly diseases mutated and targeted new, non-human niches. Overwhelmingly, meanwhile, changes in the distribution of humanly digestible food sources hugely increased the supply of energy in two crucial ways. First, more varied staples were available, indemnifying against blight and

ecological disaster societies formerly dependent on a very limited range of crops or animals. (There were exceptions, as some newly available crops proved deceptively nutritious, trapping some populations into over-reliance on potatoes or maize, with subversive effects on health or the incidence of famine.) More straightforwardly, the amount of food produced in the world increased with the effects of the ecological revolution, which enabled farmers and ranchers to colonize previously unexploited or underexploited lands—especially drained, upland, and marginal soils—and to boost the productivity of existing farmland.

Supplementary sources boosted food energy: animal musclepower, gravity, wind and running water, clockwork and gears (on a very small scale), and the combustibles (mainly wood, with some use of wax, animal and vegetable fats, peat, turf and waste grasses, tar, and coal) used to make heat for warmth and cooking. But the world resorted to no new revolutionary way of mobilizing energy until industrialization, when the use of fossil fuels and steam power multiplied muscle exponentially. The results, as we have seen, were equivocal. As Ian Morris points out, people’s capacity to ‘get things done’ was immeasurably enhanced. But as Anjana Singh points out in her chapter, that extra capacity was exploited for destructive ends —of human life in war, and of the environment in pollution and resource depletion. In the last hundred years or so, electricity has displaced steam and new ways of generating power have begun to relieve stress on fossil fuels, but the equivocal outcomes remain unresolved.

Along with divergence and accelerating change, the third theme to emerge in The Oxford History of the World is of humans’ relationship with the rest of nature, which changes constantly, sometimes in response to human—or in currently fashionable jargon ‘anthropogenic’—influences that form part of the story of culture, but also, more powerfully, in ways humans cannot control and are still largely unable to foresee: climatic, seismic, pathogenic. Every society has had to adjust its behaviour in order to balance exploitation with conservation. Civilization is perhaps best understood as a process of

environmental modification to suit human purposes—re-shaping landscapes for ranching and tilling, for instance, then smothering them with new, built environments designed to satisfy human cravings. In some ways, environmental history is another chronicle of accelerating change, as exploitation has intensified in order to supply growing populations and growing per capita consumption. The relationship between humans and the rest of creation has always been uneasy and has become increasingly conflictive. On the one hand, humans dominate ecosystems, master vast portions of the biosphere, and obliterate species that we see as threatening or competitive. Yet, on the other, we remain vulnerable to the uncontrollable lurches of forces that dwarf us: we cannot halt earthquakes, or influence the sun, or predict every new plague.

The story of human interventions in the environment looks like a series of hair’s breadth escapes from disaster, each of which, like the sallies of an adventure story, thickened the plot and introduced new difficulties. Farming helped people who practised it survive climate change; however, it created new reservoirs of disease among domesticated animals, condemned societies to dependence on limited foodstuffs, and justified tyrannous polities that organized and policed war, labour, irrigation, and warehousing. Industrialization hugely boosted productivity, at the cost of fearful labour conditions in ‘infernal wens’ and ‘dark, satanic mills’. Fossil fuels unlocked vast reserves of energy, but polluted the air and raised global temperatures. Artificial pesticides and fertilizers saved millions from starvation, but poisoned the soil and winnowed biodiversity. Nuclear power has saved the world from exhaustion and threatened it with immolation. Medical science has spared millions of people from physical sickness, but ever more rampant ‘lifestyle diseases’—often the result of misuse of sex, food, drugs, and drink—have gone on wrecking or ending lives, while neuroses and psychoses swarm. Overall, the global disease environment hardly seems benign. The costs of treatment leave most of the world outside the reach of enhanced medicine. Technology has saved us from each successive set of self-inflicted problems, only to create new ones that demand

ever bigger, riskier, and costlier solutions. A technologically dependent world is like the old woman in the song, who began by swallowing a fly and, in an effort to catch it, gulped down ever bigger predators in pursuit of each other. She ended ‘dead, of course’. We have no better strategy at present than escalating recourse to technology.

The fourth theme apparent in this book concerns the one area apparently largely exempt from change: what we might call the limitations of culture—the apparently immutable background of all other stories in the stagnancy and universality of human nature, the bedrock mixture of good and evil, wisdom and folly that transcends every cultural boundary and never seems to alter much over time. While we increase our ‘capacity to get things done’, as Ian Morris points out, our morals and our stewardship of the world and of each other remain mired in selfishness and riven with hostilities. Anjana Singh points out how much of our enhanced capacity we divert to destructive ends—destructive of each other, destructive of the ecosystems on which we depend, destructive of the biosphere that is our common home.

We can, of course, point to some improvement, but only with subversive qualifications. Perhaps the most comforting change traceable in this book is the way our moral community has gradually enlarged to encompass almost the whole of humankind. The achievement has been astounding, because humans are not typically well disposed to those outside their own groups of kin or fellow countrymen. As Claude Lévi-Strauss pointed out, most languages have no word for ‘human’ beyond the term that denotes group members: outsiders are usually called by words that mean something like ‘beast’ or ‘demon’. The struggle to induce humans to see common humanity beneath the superficialities of appearance, pigmentation, and differences of culture or priorities or abilities has been long and hard. Key moments can be traced in the chapters below by Manuel Lucena Giraldo, Anjana Singh, Paolo Luca Bernardini, and Jeremy Black, but blind spots remain. Some bioethicists still regard certain minorities as imperfectly human or

disqualified from human rights: the unborn, the victims of euthanasia, infants supposedly too tiny to have conscious interests. Some feel our moral community will never be fully moral while it excludes non-human animals. And in practice, we behave as viciously as ever, when the opportunity arises or the perceived need occurs, persecuting and exploiting migrants and refugees, victimizing minorities, exterminating supposed enemies, immiserating the poor while increasing cruelly unjust wealth gaps, engrossing resources that ought to be common, and honouring ‘human rights’ in the breach. Claims of the demise or, at least, retreat of violence seem premature (though David Christian would dissent). Fears of the destructiveness of modern weapons has curtailed large-scale war, but terrorism has expanded its niche. Outside the realms of terrorism and war crimes, murder has declined, suicide grown. Abortion has replaced infanticide in some parts of the world. Spanking has dropped out of the parental armoury, while sadism has achieved tolerance, even a certain respectability. Overall, people seem no better and no worse, no dumber or brighter than ever. The effect of moral stasis is not, however, neutral, because of the way improved technologies empower evil and folly.

Finally, as this book helps to show, the story of human societies’ relationships with each other can be told in terms of the shift of what I call initiative: the power of some human groups to influence others. Initiative changes broadly in line with the global distribution of power and wealth. With some exceptions, wealthier, tougher communities influence those that are less well off in these respects. As readers of this book will see, over the 7,000 years or so during which we can document the drift of initiative, it was first concentrated in Southwest Asia and around the eastern end of the Mediterranean. It became concentrated, for largely undetectable reasons, in east and south Asia, and especially in China, from early in the Christian Era until a slow shift westward became discernible, in some respects, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, accelerating in the nineteenth and twentieth. Western science, especially astronomy, established parity of esteem in China—a

surprising achievement in the face of Chinese contempt for Western ‘barbarians’. In the eighteenth century, Western European markets seem, on the whole, to have been more integrated than those of India, wages higher, mutatis mutandis, than those of India or China, and financial institutions, especially in Britain, better equipped to fund new economic initiatives. But in overall productivity and in terms of the balance of trade, China and India led the world until well into the nineteenth century. At present, Western hegemony seems to be waning and the world reverting, in this respect, to a situation in which initiative is unfocused, exchanged between cultures in multiple directions, with China re-emerging in her ‘normal’ place as the most likely potential world hegemon.

The global triumph of two Western ideas—capitalism and democracy—may come to seem, in retrospect, both the culmination and conclusion of Western supremacy. In the last three decades of the twentieth century, most dictatorships toppled or tottered. One form of totalitarianism, fascism, collapsed earlier in the century; its communist rival crumbled in the 1990s. Meanwhile, deregulating governments in much of the world liberated market forces. The dawn soon darkened and blight disfigured any bliss optimists may have felt at being alive. Democracy proved insecure, as many states slid back into authoritarian hands. Fanaticisms replaced ideologies: nationalism, which had seemed doomed in the increasingly interdependent world of globalization, re-emerged like vermin from the crooked woodwork of the world; religion—which secularists had hoped to see burn itself out—reignited mephitically as a justification for actions of terrorists, who generally seemed to be psychotic and incoherent victims of manipulation by criminals, but who talked like fundamentalists and dogmatists. Capitalism proved delusive. Instead of increasing wealth, it increased wealth gaps. Even in the world’s most prosperous countries, the chasm between fat cats and regular guys gaped by the beginning of the new millennium at levels not seen since before the First World War. On a global scale, the scandal of inequality was frankly indecent, with, for every billionaire, thousands of the poor dying for want of basic sanitation, shelter, or

medicine. Life expectancy in Japan and Spain was nearly double that of a peasant in Burkina Faso. The global ‘financial meltdown’ of 2008 exposed the iniquities of under-regulated markets, but no one knew what to do about it. Economic lurches have continued, increasing the prevailing insecurities that nourish extremist politics. Capitalism has been dented, if not discredited, but no efforts to replace it, or even patch its wounds, have worked.

History is a study of change. This book is therefore divided into chronological tranches, in each of which an author who is an expert in environmental history sketches the environmental context and humans’ interactions with it, before others, also experts in their fields, deal with what happened to culture—typically in one chapter on art and thought, another on politics and behaviour—in the period concerned. For early periods, up to about 10,000 years ago, the evidence of what people thought and what they did is so interdependent that contributors have to cover both in a single chapter in each part of the book. For more recent periods, the evidence is abundant enough for us to see the differences, as well as the similarities, between the way people recorded thoughts and feelings, on the one hand, and the way they behaved in practice towards each other in politics and society. Thus, the chapters multiply accordingly.

Readers will see that, although all the contributors to this book try to stand back from the world in order to see it whole, or as nearly whole as possible, and although all have in mind the themes of divergence, acceleration, environmental interactions, the limitations of culture, and the shifts of initiative, there are tensions between the authors, differences of priority and emphasis, and sometimes underlying conflicts of values or ideological tenets or religious beliefs. Still, the collegiality and goodwill with which everyone involved in the project has collaborated unstintingly is one cause for pleasure. Another, which I hope readers will appreciate, is that the diversity of my fellow writers’ viewpoints echoes, in a small way, the diversity of history, and helps us see it from multiple perspectives.