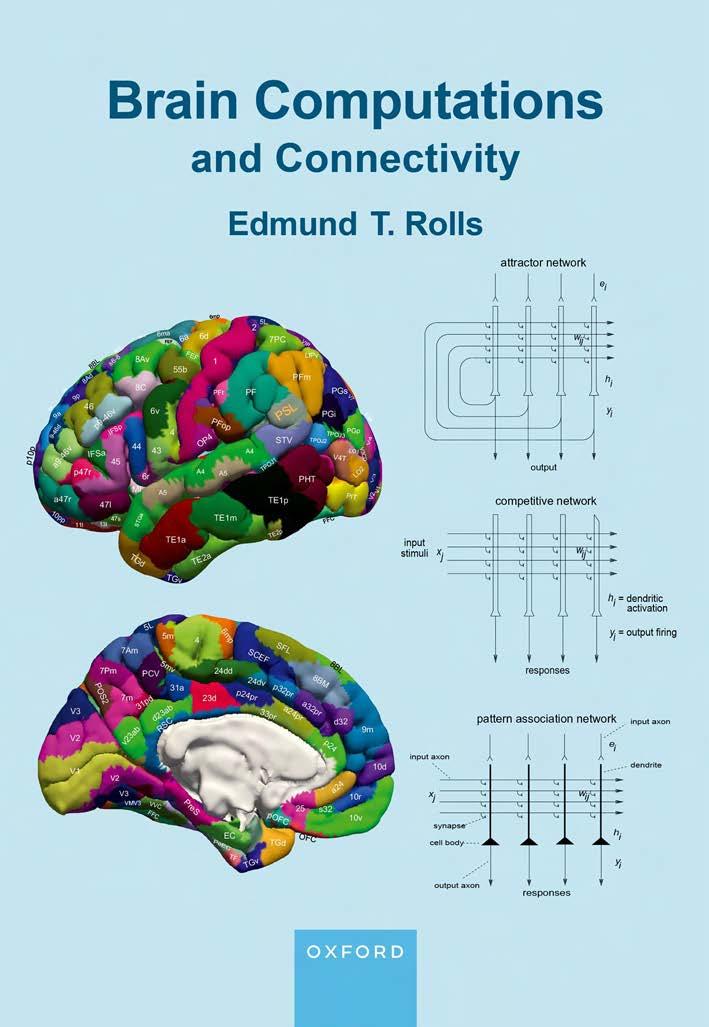

BrainComputationsandConnectivity

EdmundT.Rolls

OxfordCentreforComputationalNeuroscience

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

c EdmundT.Rolls2023

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted Somerightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,forcommercialpurposes, withoutthepriorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpressly permittedbylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriate reprographicsrightsorganization.

This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023940370

ISBN 978–0–19–888791–1

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198887911.001.0001

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface

Thisbook, BrainComputationsandConnectivity isanupdatetoRolls BrainComputations: WhatandHow publishedbyOxfordUniversityPressin2021.Akeypartofthisupdated versionof BrainComputations:WhatandHow istheadditionofmuchnewevidencethat hasemergedsince2021ontheconnectivityofthehumanbrain,whichbyanalysingthe effectiveorcausalconnectivitybetween360corticalregions,enrichesourunderstanding ofinformationprocessingstreamsinthehumancerebralcortex.Knowinghowonecortical regionconnectstoothercorticalregionshelpstoprovideadeeperunderstandingofhow eachstageinaprocessingstreamcontributestothecomputationsbeingperformed,aseach processingstreamisnowbecomingbetterdefined.

Theadditionin BrainComputationsandConnectivity ofmuchnewevidenceontheconnectivityofthehumanbrainisleadingtobetterunderstandingofwhatiscomputedindifferenthumanbrainregions,whichinturnhasimplicationsforhowthecomputationsareperformed.Theaddedemphasisinthisbookontheorganisation,connectivity,andfunctionsof 360corticalregionsinthehumanbrainincreasestheapplicationofnewapproachestakento understandinghowthebrainworksthataredescribedinthisbook,bymakingtheevidence veryrelevanttothehumanbrain,andtherebytothosewhoareinterestedindisordersofthe humanbrain,includingneurologistsandpsychiatrists,aswellastoallthoseinterestedin understandinghowthehumanbrainworksinhealthanddisease.Theenablesthecomputationalapproachestounderstandingbrainfunctiondescribedinthisbooktobecombined withandmadehighlyrelevanttounderstandinghumanbrainfunction.Itishopedthatthese developmentsinunderstandinghumanbrainfunctionbyincludinganalysisoftheconnectivityofthe360corticalregionsintheHumanConnectomeProjectMultimodalParcellation (HCP-MMP)atlas(Glasseretal., 2016a; Huangetal., 2022)asdescribedherewillprovidea foundationforfutureresearchthatbyusingtheHCP-MMPcanberelatedtotheconnectivity andfunctionsofthese360corticalregionsinthehumanbrainthataredescribedinthisbook. Thetitleofthisbook, BrainComputationsandConnectivity,referstotheimportanceofthis typeofconnectivityinunderstandingwhatandhowthebraincomputes.

Anotherfeatureofthisbookisthatitadoptswhatwasdescribedasa‘grandunifying approach’inareviewinthejournal Brain (Manohar, 2022)of BrainComputations:What andHow (Rolls, 2021b)inthatittakesabiologicallyplausibleapproachtohowthebrain computes,ratherthaninvokingtheartificialintelligenceapproachofdeeplearningtotry toaccountforbraincomputation.Theapproachtohowthebraincomputesinthisbookis biologicallyplausibleinthatitutilisesprimarilylocalsynapticmodificationrulestosetup thesynapticconnectionsbetweenneurons,andunsupervisedlearning,yetconsidershowfar thiscantakeusinunderstandinghowthebrainoperates.Thisapproachisquitedifferenttothe deeplearningapproachusednowinmuchmachinelearningandAI,whichbackpropagatesan errorbackwardsthroughthenetworktocorrecteverysynapticweightinallprecedinglayers ofthenetwork,butthereisnoconnectivityinthebrainforthat.Moreover,thelearninginthe brainislargelyunsupervised,whereasdeeplearningapproachestypicallyrequireasupervisor foreachoutputneuron,whichinturnrequireswhatmustbecomputedforeachoutputneuron tobespecifiedbythedesignerofthedeepnetwork.Thepointisdeveloped(inChapter 19) thatmachinelearningmightbenefitfromunderstandingsomeoftheunsupervisedapproaches usedbythebraintosolvecomplexproblems,includingnavigation,attention,semantics,and

evensyntax.Thetitleofthisbook, BrainComputationsandConnectivity,alsoreferstothis conceptthattheactualconnectivityatthelocallevelofneuronsandsynapsesthatisfoundin thebrainisimportantinunderstandingwhatandhowitcomputes.

MyaiminmakingthisbookOpenAccessistomakethescholarshipandideasinthis bookeasilyavailabletocolleagues,intheinterestsofbetterunderstandingthehumanbrain inhealthanddisease.ThisbookcanbecitedasRolls,E.T.(2023) BrainComputations andConnectivity,OxfordUniversityPress,Oxford.Thebookcanbedownloadedfrom https://www.oxcns.org orfromtheOxfordUniversityPresswebsite.Anadvantageofpublicationofthisbookasa.pdfisthatitcontainsextensivehyperlinks,enablingreadersto quicklycross-refertootherpartsofthebookortocitations.Withthe.pdf,figurescanalsobe expandedtoshowdetails.

Manyscientists,andmanyothers,areinterestedinhowthebrainworks.Inordertounderstandthis,weneedtoknow what computationsareperformedbydifferentbrainsystems; and how theyarecomputedbyeachofthesesystems.

Theaimofthisbookistoelucidatewhatiscomputedindifferentbrainsystems;andto describecurrentcomputationalapproachesandmodelsofhoweachofthesebrainsystems computes.

Tounderstandhowourbrainswork,itisessentialtoknow what iscomputedineach partofthebrain.Thatcanbeaddressedbyutilisingevidencerelevanttocomputationfrom manyareasofneuroscience.Knowledgeoftheconnectionsbetweendifferentbrainregions isimportant,forthisshowsthatthebrainisorganisedassystems,withwholeseriesofbrain regionsdevotedforexampletovisualprocessing.Thatprovidesafoundationforexaminingthecomputationperformedbyeachbrainregion,bycomparingwhatisrepresentedina brainregionswithwhatisrepresentedintheprecedingandfollowingbrainregions,using techniquesofforexampleneurophysiologyandfunctionalneuroimaging.Thewaysinwhich effectiveconnectivityisnowavailablefor360corticalregionsareintroducedinChapter1, withtheresultsofthesenewanalysesfoundthroughoutthisbook.Neurophysiologyatthe singleneuronlevelisneededbecausethisisthelevelatwhichinformationistransmitted betweenthecomputingelementsofthebrain,theneurons.Evidencefromtheeffectsofbrain damage,includingthatavailablefromneuropsychology,isneededtohelpunderstandwhat differentpartsofthesystemdo,andindeedwhateachpartisnecessaryfor.Functionalneuroimagingisusefultoindicatewhereinthehumanbraindifferentprocessestakeplace,andto showwhichfunctionscanbedissociatedfromeachother.Soforeachbrainsystem,evidence onwhatiscomputedateachstage,andwhatthesystemasawholecomputes,isessential.

Tounderstandhowourbrainswork,itisalsoessentialtoknow how eachpartofthe braincomputes.Thatrequiresaknowledgeofwhatiscomputedbyeachpartofthebrain, butitalsorequiresknowledgeofthenetworkpropertiesofeachbrainregion.Thisinvolves knowledgeoftheconnectivitybetweentheneuronsineachpartofthebrain,andknowledge ofthesynapticandbiophysicalpropertiesoftheneurons.Italsorequiresknowledgeofthe theoryofwhatcanbecomputedbynetworkswithdefinedconnectivity.

Thereareatleastthreekeygoalsoftheapproachesdescribedhere.Oneistounderstand ourselvesbetter,andhowweworkandthink.Asecondistobebetterabletotreatthesystem whenithasproblems,forexampleinmentalillnesses.Medicalapplicationsareaveryimportantaimofthetypeofresearchdescribedhere.Athird,istobeabletoemulatetheoperation ofpartsofourbrains,whichsomeinthefieldofartificialintelligence(AI)wouldliketodoto produceusefulcomputersthatincorporatesomeoftheprinciplesofcomputationutilisedby thebrain.Allofthesegoalsrequire,andcannotgetofftheground,withoutafirmfoundation inwhatiscomputedbybrainsystems,andtheoriesandmodelsofhowitiscomputed.To understandtheoperationofthewholebrain,itisnecessarytoshowhowthedifferentbrain

systemsoperatetogether:butanecessaryfoundationforthisistoknowwhatiscomputedin eachbrainsystem,andtheconnectivitybetweenthedifferentregionsinvolved.

Partoftheenterprisehereistostimulatenewtheoriesandmodelsofhowpartsofthebrain work.Theevidenceonwhatiscomputedindifferentbrainsystemshadadvancedrapidlyin thelast50years,andprovidesareasonablefoundationfortheenterprise,thoughthereis muchthatremainstobelearned.Theoriesofhowthecomputationisperformedareless advanced,butprogressisbeingmade,andcurrentmodelsaredescribedinthisbookfor manybrainsystems,intheexpectationthatbeforefurtheradvancesaremade,knowledgeof theconsiderablecurrentevidenceonhowthebraincomputesprovidesausefulstartingpoint, especiallyascurrenttheoriesdotakeintoaccountthelimitationsthatarelikelytobeimposed bytheneuralarchitecturespresentinourbrains.Inthisbook,thefocusisonbiologically plausiblealgorithmsforbraincomputation,ratherthanforexampledeeplearningwhichdoes notappeartobehowthebrainlearnsandcomputes(Sections B.12 and B.14).

Thesimplestwaytodelineate braincomputation istoexaminewhatinformationis representedateachstageofprocessing,andhowthisisdifferentfromstagetostage.For exampleintheprimaryvisualcortex(V1),neuronsrespondtosimplestimulisuchasbars oredgesorgratingsandhavesmallreceptivefields.Littlecanbereadofffromthefiring ratesaboutforexamplewhosefaceisrepresentedfromasmallnumberofneuronsinV1. Ontheotherhand,afterfourorfivestagesofprocessing,intheinferiortemporalvisual cortex,informationcanbereadfromthefiringratesofneuronsaboutwhosefaceisbeing viewed,andindeedthereisremarkableinvariancewithrespecttotheposition,size,contrast andeveninsomecasesviewoftheface.Thatisamajorcomputation,andindicateswhatcan beachievedbybiologicalneuronalnetworkcomputation.

Theseapproachescanonlybetakentounderstandbrainfunctionbecausethereisconsiderablelocalizationoffunctioninthebrain,quiteunlikeadigitalcomputer.Onefundamental reasonforlocalizationoffunctioninthebrainisthatthisminimizesthetotallengthofthe connectionsbetweenneurons,andthusbrainsize.Anotheristhatitsimplifiesthegenetic informationthathastobeprovidedinordertobuildthebrain,becausetheconnectivityinstructionscanreferconsiderablytolocalconnections.Thesepointsaredevelopedinmybook CerebralCortex:PrinciplesofOperation (Rolls, 2016b).

Thatbringsmetowhatisdifferentaboutthepresentbookand CerebralCortex:PrinciplesofOperation (Rolls, 2016b). CerebralCortex:PrinciplesofOperation tookonthe enormoustaskofmakingprogresswithunderstandinghowthemajorpartofourbrains,the cerebralcortex,works,byunderstandingitsprinciplesofoperation.Thepresentbookbuilds onthatapproach,andusesitasbackground,buthasthedifferentaimoftakingeachofour brainsystems,anddescribing what theycompute,andthenwhatisknownabout how each systemcomputes.Theissueofhowtheycomputereliesformanybrainsystemsonhowthe cortexoperates,so CerebralCortex:PrinciplesofOperation providesanimportantcomplementtothepresentbook.

Withitsfocusonwhatandhoweachbrainsystemcomputes,afieldthatincludescomputationalneuroscience,thisbookisdistinctfromthemanyexcellentbooksonneuroscience thatdescribemuchevidenceaboutbrainstructureandfunction,butdonotaimtoprovidean understandingofhowthebrainworksatthecomputationallevel.Thisbookaimstoforgean understandingofhowsomekeybrainsystemsmayoperateatthecomputationallevel,sothat wecanunderstandhowthebrainactuallyperformssomeofitscomplexandnecessarilycomputationalfunctionsinmemory,perception,attention,decision-making,cognitivefunctions, andactions.

Indeed,asoneofthekeyaimsofthisbookistodescribe whatcomputations areperformedbydifferentbrainsystems,Ihavechosentoincludeinthisbooksomeofthekeyactual discoveriesinneurosciencethatIbelievehelptodefinewhatcomputationsareperformedin

differentbrainsystems.Partoftheaimofcitingtheoriginalpioneeringdiscoveriesistoshow howconceptualadvanceshavebeenmadeinourunderstandingofwhatiscomputedineach regionofourbrains,forunderstandingthekeydiscoveriesprovidesafoundationforfurther advances.

Thatmakesthisbookverydifferentfrommanyofthetextbooksofneuroscience(such as PrinciplesofNeuralScience (Kandeletal., 2021)),andsomeofthetextbooksoftheoreticalneurosciencethatdescribeprinciplesofoperationofneuronsorofnetworksofneurons (DayanandAbbott, 2001; Hertzetal., 1991; Gerstneretal., 2014),butnotingeneralwhat iscomputedindifferentbrainsystems,andhowitiscomputed.Further,therearelikelytobe greatdevelopmentsinourunderstandingof how thebraincomputes,andthisbookisintended tosetoutaframeworkfornewdevelopments,byprovidingananalysisofwhatiscomputed bydifferentbrainsystems,andprovidingsomecurrentapproachestohowthesecomputations maybeperformed.Ibelievethatthisbook,anditspredecessor BrainComputations:What andHow,ispioneeringinwhatIproposeisthenecessaryapproachtounderstandingbrain function,understanding‘What’iscomputedbyeachbrainregion,and‘How’itiscomputed.

Atestofwhetherone’sunderstandingiscorrectistosimulatetheprocessingonacomputer,andtoshowwhetherthesimulationcanperformthetasksperformedbythebrain,and whetherthesimulationhassimilarpropertiestotherealbrain.Thisapproachtoneuralcomputationleadstoaprecisedefinitionofhowthecomputationisperformed,andtoprecise andquantitativetestsofthetheoriesproduced.Howmemorysystemsinthebrainworkisa paradigmexampleofthisapproach,becausememory-likeoperationswhichinvolvealtered functionalityasaresultofsynapticmodificationareattheheartofhowmanycomputationsin thebrainareperformed.Ithappensthatattentionanddecision-makingcanbeunderstoodin termsofinteractionsbetweenandfundamentaloperationsinmemorysystemsinthecortex, andthereforeitisnaturaltoaddresstheseareasofcognitiveneuroscienceinthisbook.The samefundamentalconceptsbasedontheoperationofneuronalcircuitrycanbeappliedtoall thesefunctions,asisshowninthisbook.

Oneofthedistinctivepropertiesofthisbookisthatitlinkstheneuralcomputationapproachnotonlyfirmlytoneuronalneurophysiology,whichprovidesmuchoftheprimarydata abouthowthebrainoperates,butalsotopsychophysicalstudies(forexampleofattention); toneuropsychologicalstudiesofpatientswithbraindamage;andtofunctionalmagneticresonanceimaging(fMRI)(andotherneuroimaging)approaches.Theempiricalevidencethat isbroughttobearislargelyfromnon-humanprimatesandfromhumans,becauseoftheconsiderablesimilarityoftheircorticalsystems,andthemajordifferencesintheirsystems-level computationalorganizationfromthatofrodents,assetoutinSection 19.10

Anotherfeatureofthebookisthatitaimstodescribetheprinciplesofoperationofthe brain,andindoingthat,frequentlyreferstotheoriginalresearchinwhichthoseprinciples werediscovered.AnotherfeatureofthebookisthatIhavealsochosentomakeeachChapter relativelyunderstandableonitsown,whichmayinvolvesomeinformationalsopresentin otherpartsofthebook,sothatreaderswithaninterestinonepartofthebraincanbenefitby readingtherelevantchapters,ratherthannecessarilyhavingtoreadthewholebook.

Theoverallaimsofthebookaredevelopedfurther,andtheplanofthebookisdescribed, inChapter 1.Appendix B describesthefundamentaloperationofkeynetworksofthetype thatarelikelytobethebuildingblocksofbrainfunction.Appendix C describesquantitative, informationtheoretic,approachestohowinformationisrepresentedinthebrain,whichisan essentialframeworkforunderstandingwhatiscomputedinabrainsystem,andhowitiscomputed.Appendix D describesMatlabsoftwarethathasbeenmadeavailablewiththisbook toprovidesimpledemonstrationsoftheoperationofsomekeyneuronalnetworksrelatedto corticalfunction;toshowhowtheinformationrepresentedbyneuronscanbemeasured;and toprovideatutorialversionoftheVisNetprogramforinvariantvisualobjectrecognition

describedinChapter 2.TheneuralnetworksprogramsarealsoprovidedinPython.Theprogramsareavailableat https://www.oxcns.org

Partofthematerialdescribedinthebookreflectsworkperformedincollaborationwith manycolleagues,whosetremendouscontributionsarewarmlyappreciated.Thecontributions ofmanywillbeevidentfromthereferencescitedinthetext.Especialappreciationisdue toAlessandroTreves,GustavoDeco,SylviaWirth,andSimonM.Stringer,whohavecontributedgreatlyinalwaysinterestingandfruitfulresearchcollaborationsoncomputational andrelatedaspectsofbrainfunction,andtomanyneurophysiologyandfunctionalneuroimagingcolleagueswhohavecontributedtotheempiricaldiscoveriesthatprovidethefoundationtowhichthecomputationalneurosciencemustalwaysbecloselylinked,andwhose namesarecitedthroughoutthetext.CharlNing(UniversityofWarwick)isthankedforhelp withtranslatingtheMatlabneuralnetworkprogramsdescribedinAppendix D intoPython. DrPatrickMillsandImogenKrusearethankedforveryhelpfulcommentsonanearlierversionofthisbook.Muchoftheworkdescribedwouldnothavebeenpossiblewithoutfinancial supportfromanumberofsources,particularlytheMedicalResearchCounciloftheUK,the HumanFrontierScienceProgram,theWellcomeTrust,andtheJamesS.McDonnellFoundation.IamalsogratefultomanycolleagueswhoIhaveconsultedwhilewritingthisbook.The GatsbyFoundationisthankedforagranttowardsthecostofmakingthisbookOpenAccess. ThebookwastypesetbytheauthorusingLATEXandWinEdt.

Updatestoand.pdfsofmanyofthepublicationscitedinthisbookareavailableat https://www.oxcns.org.Updatesandcorrectionstothetextandnotesarealsoavailableat https://www.oxcns.org.

Idedicatethisworktotheoverlappinggroup:myfamily,friends,andcolleagues–insalutem praesentium,inmemoriamabsentium.

1.14.1Thefinestructureandconnectivityoftheneocortex

1.14.4Quantitativeaspectsofcorticalarchitecture

1.14.5Functionalpathwaysthroughthecorticallayers

2Theventralvisualsystem

2.1Introductionandoverview

2.1.1Introduction

2.1.2Overviewofwhatiscomputedintheventralvisualsystem

2.1.3Overviewofhowcomputationsareperformedintheventralvisualsystem

2.1.4Whatiscomputedintheventralvisualsystemisunimodal,andisrelatedto other‘what’systemsaftertheinferiortemporalvisualcortex

2.2What:V1–primaryvisualcortex

2.3What:V2andV4–intermediateprocessingareasintheventralvisualsystem

2.4What:Invariantrepresentationsoffacesandobjectsintheinferiortemporalvisual

2.4.1Rewardvalueisnotrepresentedintheprimateventralvisualsystem

2.4.2Translationinvariantrepresentations

2.4.3Reducedtranslationinvarianceinnaturalscenes

2.4.4Sizeandspatialfrequencyinvariance

2.4.5Combinationsoffeaturesinthecorrectspatialconfiguration

2.4.6Aview-invariantrepresentation

2.4.7Learningintheinferiortemporalcortex

2.4.8Asparsedistributedrepresentationiswhatiscomputedintheventralvisual system

2.4.9Faceexpression,gesture,andview

2.4.10Specializedregionsinthetemporalcorticalvisualareas

2.5Theconnectivityoftheventralvisualpathwaysinhumans

2.5.1AVentrolateralVisualCorticalStreamtotheinferiortemporalvisualcortex forobjectandfacerepresentations 86

2.5.2AVisualCorticalStreamtothecortexintheinferiorbankofthesuperior temporalsulcusinvolvedinsemanticrepresentations 89

2.5.3AVisualCorticalStreamtothecortexinthesuperiorbankofthesuperior temporalsulcusinvolvedinmultimodalsemanticrepresentationsincludingvisualmotion,auditory,somatosensoryandsocialinformation 89

2.6Howthecomputationsareperformed:approachestoinvariantobjectrecognition

2.6.1Featurespaces

2.6.2Structuraldescriptionsandsyntacticpatternrecognition

2.6.3Templatematchingandthealignmentapproach

2.6.4Invertiblenetworksthatcanreconstructtheirinputs

2.6.5Deeplearning

2.6.6Featurehierarchies

2.7Hypothesesabouthowthecomputationsareperformedinafeaturehierarchyapproach

2.8VisNet:amodelofhowthecomputationsareperformedintheventralvisualsystem

2.8.1ThearchitectureofVisNet

2.8.2InitialexperimentswithVisNet

2.8.3Theoptimalparametersforthetemporaltraceusedinthelearningrule

2.8.4Differentformsofthetracelearningrule,anderrorcorrection

2.8.5Theissueoffeaturebinding,andasolution 134

2.8.6Operationinaclutteredenvironment

2.8.7Learning3Dtransforms

2.8.8Capacityofthearchitecture,andanattractorimplementation 159

2.8.9Visioninnaturalscenes–effectsofbackgroundversusattention 162

2.8.10Therepresentationofmultipleobjectsinascene 170

2.8.11Learninginvariantrepresentationsusingspatialcontinuity 172

2.8.12Lightinginvariance 173

2.8.13Deformation-invariantobjectrecognition 175

2.8.14Learninginvariantrepresentationsofscenesandplaces 176

2.8.15Findingandrecognisingobjectsinnaturalscenes 178

2.8.16Non-accidentalproperties,andtransforminvariantobjectrecognition 181

2.9Furtherapproachestoinvariantobjectrecognition 183

2.9.1Othertypesofslowlearning 183

2.9.2HMAX 183

2.9.3Minimalrecognizableconfigurations 188

2.9.4Hierarchicalconvolutionaldeepneuralnetworks 189

2.9.5Sigma-Pisynapses 190

2.9.6Aprincipaldimensionsapproachtocodingintheinferiortemporalvisual cortex 190

2.10Visuo-spatialscratchpadmemory,andchangeblindness 192

2.11Processesinvolvedinobjectidentification 194

2.12Top-downattentionalmodulationisimplementedbybiasedcompetition 195

2.13Highlightsonhowthecomputationsareperformedintheventralvisualsystem 198

3Thedorsalvisualsystem 201

3.1Introduction,andoverviewofthedorsalcorticalvisualstream 201

3.2Globalmotioninthedorsalvisualsystem 202

3.3Invariantobject-basedmotioninthedorsalvisualsystem 204

3.4Whatiscomputedinthedorsalvisualsystem:visualcoordinatetransforms 206

3.4.1Thetransformfromretinaltohead-basedcoordinates 207

3.4.2Thetransformfromhead-basedtoallocentricbearingcoordinates 208

3.4.3Atransformfromallocentricbearingcoordinatestoallocentricspatialview coordinates 209

3.5Howvisualcoordinatetransformsarecomputedinthedorsalvisualsystem 211

3.5.1Gainmodulation 211

3.5.2Mechanismsofgainmodulationusingatracelearningrule 211

3.5.3Gainmodulationbyeyepositiontoproduceahead-centeredrepresentation inLayer1ofVisNetCT 213

3.5.4Gainmodulationbyheaddirectiontoproduceanallocentricbearingtoa landmarkinLayer2ofVisNetCT 214

3.5.5GainmodulationbyplacetoproduceanallocentricspatialviewrepresentationinLayer3ofVisNetCT 215

3.5.6Theutilityofthecoordinatetransformsinthedorsalvisualsystem 216

3.6ThehumanDorsalVisualCorticalStream 217

3.6.1Dorsalstreamvisualdivisionregions 217

3.6.2MT+complexregions(FST,LO1,LO2,LO3,MST,MT,PH,V3CDandV4t) 218

3.6.3Intraparietalsulcusposteriorparietalcortex,regions(AIP,LIPd,LIPv,MIP, VIP;withIP0,IP1andIP2) 219

3.6.4Area7regions 220

4Thetasteandflavorsystem

221

4.1Introductionandoverview 221

4.1.1Introduction 221

4.1.2Overviewofwhatiscomputedinthetasteandflavorsystem 221

4.1.3Overviewofhowcomputationsareperformedinthetasteandflavorsystem 223

4.2Tasteandrelatedpathways:whatiscomputed 223

4.2.1Hierarchicallyorganisedanatomicalpathways 223

4.2.2Tasteneuronaltuningbecomemoreselectivethroughthetastehierarchy 226

4.2.3Theprimary,insular,tastecortexrepresentswhattasteispresentandits intensity 228

4.2.4Thesecondary,orbitofrontal,tastecortex,anditsrepresentationofthe rewardvalueandpleasantnessoftaste 229

4.2.5Sensory-specificsatietyiscomputedintheorbitofrontalcortex 231

4.2.6Oraltextureisrepresentedintheprimaryandsecondarytastecortex:viscosityandfattexture 234

4.2.7Visionandolfactionconvergeusingassociativelearningwithtastetorepresentflavorinthesecondarybutnotprimarytastecortex 236

4.2.8Top-downattentionandcognitioncanmodulatetasteandflavorrepresentationsinthetastecorticalareas 238

4.2.9Thetertiarytastecortexintheanteriorcingulatecortexprovidestherewards foraction-rewardoutcomelearning 240

4.2.10Taste,oraltextureandflavorprovidetherewardsforeating,andthegut providessatietysignals 241

4.3Tasteandrelatedpathways:howthecomputationsareperformed 245

4.3.1Increasedselectivityoftasteandflavorneuronsthroughthehierarchyby competitivelearningandconvergence 245

4.3.2Patternassociationlearningofassociationsofvisualandolfactorystimuli withtaste 245

4.3.3Rule-basedreversalofvisualtotasteassociationsintheorbitofrontalcortex 246

4.3.4Sensory-specificsatietyisimplementedbyadaptationofsynapsesonto orbitofrontalcortexneurons 246

4.3.5Top-downcognitiveandattentionalmodulationisimplementedbybiased activation 247

5.1Introduction

251

5.1.1Overviewofwhatiscomputedintheolfactorysystem 251

5.1.2Overviewofhowthecomputationsareperformedintheolfactorysystem 252

5.2Whatiscomputedintheolfactorysystem

253

5.2.11000gene-encodedolfactoryreceptortypes,and1000corresponding glomerulustypesintheolfactorybulb 253

5.2.2Theprimaryolfactory,pyriform,cortex:olfactoryfeaturecombinationsare whatisrepresented 255

5.2.3Orbitofrontalcortex:olfactoryneuronalresponseselectivity 256

5.2.4Orbitofrontalcortex:olfactorytotasteconvergence 257

5.2.5Orbitofrontalcortex:olfactorytotasteassociationlearningandreversal 257

5.2.6Orbitofrontalcortex:olfactoryrewardvalueisrepresented 259

5.2.7Cognitiveinfluencesonolfactoryrepresentationsintheorbitofrontalcortex 260

5.3Howcomputationsareperformedintheolfactorysystem

262

5.3.1Olfactoryreceptors,andtheolfactorybulb 262

5.3.2Olfactory(pyriform)cortex 263

5.3.3Orbitofrontalcortex 267

6Thesomatosensorysystem

6.1Whatiscomputedinthesomatosensorysystem

6.1.1Thereceptorsandperiphery

6.1.2Theanteriorsomatosensorycortex,areas1,2,3a,and3b,intheanterior parietalcortex

6.1.3Theventralsomatosensorystream:areasS2andPV,inthelateralparietal cortex

6.1.4Thedorsalsomatosensorystreamtoarea5andthen7b,intheposterior parietalcortex

6.1.5Somatosensoryrepresentationsintheinsula

6.1.6Somatosensoryandtemperatureinputstotheorbitofrontalcortex,affective value,pleasanttouch,andpain 272

6.1.7Decision-makinginthesomatosensorysystem

6.1.8Somatosensorycorticalregionsandconnectivityinhumans

6.2Howcomputationsareperformedinthesomatosensorysystem

6.2.1Hierarchicalcomputationinthesomatosensorysystem

6.2.2Computationsforpleasanttouchandpain

6.2.3Themechanismsforsomatosensorydecision-making

7Theauditorysystem

7.1Introduction,andoverviewofcomputationsintheauditorysystem

7.2AuditoryLocalization

7.3Ventralanddorsalcorticalauditorypathways

7.4Theventralcorticalauditorystream

7.5Thedorsalcorticalauditorystream

7.6Auditorycorticalregionsandconnectivityinhumans

7.6.1EarlyAuditorycorticalregions

7.6.2Ventralauditorycorticalstreams

7.6.3Dorsalauditorycorticalstreams

7.6.4Otherauditorysystemcorticalconnectivities

7.7Howthecomputationsareperformedintheauditorysystem

8Thetemporalcortex

8.1Introductionandoverview

8.2Middletemporalgyrusandfaceexpressionandgesture

8.3Semanticrepresentationsinthetemporallobeneocortex

8.3.1Neurophysiologyofthemedialtemporallobe,includingconceptcells

8.3.2Neuropsychology 303

8.3.3Functionalneuroimaging

8.3.4Brainstimulation

8.4Connectivityandfunctionsofthehumantemporalloberegionsrelatedtosemantics 305

8.4.1Group1semanticregionsthatincluderegionsintheventralbankofthe SuperiorTemporalSulcus 306

8.4.2Group3semanticregionsthatincluderegionsinthedorsalbankofthe SuperiorTemporalSulcus 309

8.5Themechanismsforsemanticlearninginthehumananteriortemporallobe 311 9Thehippocampus,memory,andspatialfunction 313

9.1Introductionandoverview 313

9.1.1Overviewofwhatiscomputedbythehippocampalsystem 313

9.1.2Overviewofhowthecomputationsareperformedbythehippocampalsystem 315

9.2Whatiscomputedinthehippocampus

9.2.1Systems-levelanatomy 316

9.2.2Evidencefromtheeffectsofdamagetothehippocampus 319

9.2.3Episodicmemoriesneedtoberecalledfromthehippocampus,andcanbe usedtohelpbuildneocorticalsemanticmemories 321

9.2.4Systems-levelneurophysiologyoftheprimateincludinghumanhippocampus 324

9.2.5Spatialviewcellsinprimatesincludinghumans,andfovealvision

9.2.6Headdirectioncellsinthepresubiculum 344

9.2.7Perirhinalcortex,recognitionmemory,andlong-termfamiliaritymemory

9.2.8Connectivityofthehumanhippocampalsystem 353

9.3Howcomputationsareperformedinthehippocampalsystem

9.3.1Historicaldevelopmentofthetheoryofthehippocampus

9.3.2Hippocampalcircuitry

9.3.3Medialentorhinalcortex,spatialprocessingstreams,andgridcells

9.3.4Lateralentorhinalcortex,objectprocessingstreams,andthegenerationof timecellsinthehippocampus 372

9.3.5CA3asanautoassociationmemory 378

9.3.6Dentategranulecells 397

9.3.7CA1cells

9.3.8Backprojectionstotheneocortex,memoryrecall,andconsolidation 405

9.3.9Backprojectionstotheneocortex–quantitativeaspects 409

9.3.10Simulationsofhippocampaloperation 413

9.3.11Thelearningofspatialviewandplacecellrepresentations 414

9.3.12Linkingtheinferiortemporalvisualcortextospatialviewandplacecells 416

9.3.13Ascientifictheoryoftheartofmemory:scientiaartismemoriae 418

9.3.14Hownavigationisperformed 419

9.3.15Navigationalcomputationsusingneurontypesfoundinprimatesincluding humans 423

9.4Testsofthetheoryofhippocampalcortexoperation 432

9.4.1Dentategyrus(DG)subregionofthehippocampus 432

9.4.2CA3subregionofthehippocampus 435

9.4.3CA1subregionofthehippocampus 442

9.5Comparisonofspatialprocessingandcomputationsinprimatesincludinghumansvs rodents 445

9.5.1Similaritiesanddifferencesbetweenthespatialrepresentationsinprimates androdents 445

9.5.2Hippocampalcomputationalsimilaritiesanddifferencesbetweenprimates androdents 447

9.6Synthesis:thehippocampus:memory,navigation,orboth? 450

9.7Comparisonwithothertheoriesofhippocampalfunction 454

10Theparietalcortex,spatialfunctions,andnavigation 459

10.1Introductionandoverview 459

10.1.1Overviewofwhatiscomputedintheparietalcortex 459

10.1.2Overviewofhowthecomputationsareperformedintheparietalcortex 460

10.2Inferiorparietalcortexsomatosensorystream,PFregions 460

10.3Intraparietalsulcusposteriorparietalcortex,regionsAIP,LIPd,LIPv,MIP,VIP,IP0, IP1,andIP2 464

10.4Posteriorsuperiorparietalcortex,regions7AL,7Am,7PC,7PL,and7Pm 466

10.5Inferiorparietalcortex,visualregionsPFm,PGi,PGsandPGp 467

10.5.1RegionPGi

10.5.2RegionPGs

10.5.3RegionPFm

10.5.4RegionPGp 471

10.6Navigation:Whatcomputationsareperformedintheparietalandrelatedcortex 473

10.7Howthecomputationsareperformedintheparietalcortex 474

11Theorbitofrontalcortex,amygdala,rewardvalue,emotion,and decision-making

11.1Introductionandoverview

11.1.3Overviewofhowthecomputationsareperformedbytheorbitofrontalcortex 478

11.2Thetopologyandconnectionsoftheorbitofrontalcortex

11.2.2Outputsoftheorbitofrontalcortex

11.3Whatiscomputedintheorbitofrontalcortex 483

11.3.1Theorbitofrontalcortexrepresentsrewardvalue

11.3.2Neuroeconomicvalueisrepresentedintheorbitofrontalcortex 490

11.3.3Arepresentationoffaceandvoiceexpressionandothersociallyrelevant stimuliintheorbitofrontalcortex 492

11.3.4Negativerewardpredictionerrorneuronsintheorbitofrontalcortex 495

11.3.5Thehumanmedialorbitofrontalcortexrepresentsrewards,andthelateral orbitofrontalcortexnon-rewardandpunishers 500 11.3.6Decision-makingintheorbitofrontal/ventromedialprefrontalcortex 502 11.3.7Theventromedialprefrontalcortexandmemory 504

11.3.8Theorbitofrontalcortexandemotion 506

11.3.9Emotionalorbitofrontalvsrationalroutestoaction 508

11.3.10Theconnectivityofthehumanorbitofrontalcortex,anditsrelationtofunction 521

11.3.11Mentalproblemsassociatedwiththeorbitofrontalcortex 528

11.4Whatiscomputedintheamygdalaforemotion 529

11.4.1Overviewofthefunctionsoftheamygdalainemotion 529

11.4.2Theamygdalaandtheassociativeprocessesinvolvedinemotion-related learning 530

11.4.3Connectionsoftheamygdala 531

11.4.4Effectsofamygdalalesions 532

11.4.5Amygdalalesionsinprimates 532

11.4.6Amygdalalesionsinrats 534

11.4.7Neuronalactivityintheprimateamygdalatoreinforcingstimuli 535

11.4.8Neuronalresponsesintheamygdalatofaces 536

11.4.9Evidencefromhumans 538

11.4.10Connectivityofthehumanamygdala 539

11.5Howthecomputationsareperformedintheorbitofrontalcortex 544

11.5.1Decision-makinginattractornetworksinthebrain 544

11.5.2Analysesofreward-relateddecision-makingmechanismsintheorbitofrontal cortex 549

11.5.3Amodelforreversallearningintheorbitofrontalcortex 554

11.5.4Atheoryandmodelofnon-rewardneuralmechanismsintheorbitofrontal cortex 559

11.6Highlights:thespecialcomputationalrolesoftheorbitofrontalcortex 560

12Thecingulatecortex 564

12.1Introductiontoandoverviewofthecingulatecortex 564

12.1.1Introduction 564

12.1.2Overviewofwhatiscomputedinthecingulatecortex 565

12.1.3Overviewofhowthecomputationsareperformedbythecingulatecortex 567

12.2Anteriorcingulatecortex 568

12.2.1Anteriorcingulatecortexanatomyandconnectionsinprimates 568

12.2.2Anteriorcingulatecortex:Aframework 569

12.2.3Anteriorcingulatecortexandaction-outcomerepresentations 571

12.2.4Anteriorcingulatecortexlesioneffects 572

12.2.5Anteriorcingulatecortexandventromedialprefrontalcortexconnectivityand functionsinhumans 572

12.2.6Pregenualanteriorcingulaterepresentationsofrewardvalue,andsupracallosalanteriorcingulaterepresentationsofpunishersandnon-reward 575

12.2.7Thehumansupracallosalanteriorcingulatecortex,dACC,andactionoutcomelearning 578

12.2.8Rewardvalueoutputsfromtheorbitofrontalandpregenualanteriorcortex, andvmPFC,tothehippocampalmemorysystem 579

12.2.9Thepregenualanteriorcingulatecortexhasconnectivitywiththeseptal cholinergicsystemthatisinvolvedinmemoryconsolidation 579

12.2.10Rewardvalueoutputsfromtheorbitofrontalandpregenualanteriorcortex, andvmPFC,tothehippocampalsystemtoprovidethegoalsfornavigation 580

12.2.11Subgenualcingulatecortex 581

12.3Posteriorcingulatecortex 581

12.3.1Introductionandoverview 581

12.3.2Postero-ventralposteriorcingulateandmedialparietalregions31pd,31pv, d23ab,v23aband7m,andtheirrelationtoepisodicmemory 582

12.3.3Antero-dorsalPosteriorCingulateDivisionregions23d,31a,PCV;andRSC, POS2,andPOS1;andtheirrelationtonavigationandexecutivefunction 584

12.3.4DorsalVisualTransitionalareaandProStriateregion:theretrosplenialscene area 587

12.4Mid-cingulatecortex,thecingulatemotorarea,andaction–outcomelearning 588

12.5Howthecomputationsareperformedbythecingulatecortex 589

12.5.1Theanteriorcingulatecortexandemotion 589

12.5.2Action-outcomelearninginthesupracallosalanteriorcingulatecortex (dACC) 590

12.5.3Connectivityoftheposteriorcingulatecortexwiththehippocampalmemory system 592

12.6Synthesisandconclusions 593

13.2Divisionsofthelateralprefrontalcortex 600

13.2.1Thedorsolateralprefrontalcortex 600

13.2.2Thecaudalprefrontalcortex 603

13.2.3Theventrolateralprefrontalcortex 603

13.3Theconnectivityandcomputationalorganisationofthehumanprefrontalcortex 603

13.3.1Inferiorfrontalgyrus 604

13.3.2Dorsolateralprefrontalcortexdivision 606

13.4Thelateralprefrontalcortexandtop-downattention 609

13.5Thefrontalpolecortex 612

13.6Howthecomputationsareperformedintheprefrontalcortex 613

13.6.1Corticalshort-termmemorysystemsandattractornetworks 613

13.6.2Prefrontalcortexshort-termmemorynetworks,andtheirrelationtoperceptualnetworks 615

13.6.3Mappingfromonerepresentationtoanotherinshort-termmemory 620

13.6.4Themechanismsoftop-downattention 621

13.6.5Computationalnecessityforaseparate,prefrontalcortex,short-termmemorysystem 622

13.6.6Synapticmodificationisneededtosetupbutnottoreuseshort-termmemory systems 623

13.6.7Sequencememory 623

13.6.8Workingmemory,andplanning 623

14Languageandsyntaxinthebrain 624

14.1Introductionandoverview 624

14.1.1Introduction 624

14.1.2Overview 624

14.2Whatiscomputedindifferentbrainsystemstoimplementlanguage 626

14.2.1TheWernicke-Lichtheim-Geschwindhypothesis 626

14.2.2Thedual-streamhypothesisofspeechcomprehension 627

14.2.3Readingrequiresdifferentbrainsystemstohearingspeech 627

14.2.4Semanticrepresentations 629

14.2.5Syntacticprocessing 630

14.2.6Theparietalcortex:supramarginalandangulargyri 631

14.3Corticalregionsforlanguageandtheirconnectivityinhumans 631

14.3.1Asemanticsystemthatincludestheinferiorbankofthesuperiortemporal sulcusincludingobjectrepresentations 632

14.3.2Asemanticsystemthatincludesthesuperiorbankofthesuperiortemporalsulcusincludingvisualmotion,auditory,somatosensoryandsocial information 634

14.3.3Multimodalsemanticrepresentations 635

14.3.4Broca’sareaandrelatedregions(TGv444547lSFL55b) 637

14.4Hypothesesabouthowsemanticrepresentationsarecomputed 640

14.5Aneurodynamicalhypothesisabouthowsyntaxiscomputed 641

14.5.1Bindingbysynchrony? 641

14.5.2Syntaxusingaplacecode 642

14.5.3Temporaltrajectoriesthroughastatespaceofattractors 642

14.5.4Hypothesesabouttheimplementationoflanguageinthecerebralcortex 643

14.5.5Testsofthehypotheses–amodel 646

14.5.6Testsofthehypotheses–findingswiththemodel 651

14.5.7Evaluationofthehypotheses 654

14.5.8Furtherapproaches 658

15.1Introductionandoverview

15.2Whatiscomputedindifferentcorticalmotor-relatedareas 661

15.2.1VentralparietalandventralpremotorcortexF4 661

15.2.2Superiorparietalareaswithactivityrelatedtoreaching 661

15.2.3Inferiorparietalareaswithactivityrelatedtograsping,andventralpremotor cortexF5 662

15.3Themirrorneuronsystem 662

15.4Howthecomputationsareperformedinmotorcorticalandrelatedareas 664

16Thebasalganglia

16.1Introductionandoverview

16.2Systems-levelarchitectureofthebasalganglia 666

16.3Whatcomputationsareperformedbythebasalganglia? 669

16.3.1Effectsofstriatallesions 669

16.3.2Neuronalactivityindifferentpartsofthestriatum 670

16.4Howdothebasalgangliaperformtheircomputations? 683

16.4.1Interactionbetweenneuronsandselectionofoutput 683

16.4.2Convergencewithinthebasalganglia,usefulforstimulus-responsehabit learning 686

16.4.3Dopamineasarewardpredictionerrorsignalforreinforcementlearningin thestriatum 688

16.5Comparisonofcomputationsforselectioninthebasalgangliaandcerebralcortex 692

17Cerebellarcortex

17.1Introduction

17.2Architectureofthecerebellum 697

17.2.1TheconnectionsoftheparallelfibresontothePurkinjecells 697

17.2.2TheclimbingfibreinputtothePurkinjecell 698

17.2.3Themossyfibretogranulecellconnectivity 698

17.3ModifiablesynapsesofparallelfibresontoPurkinjecelldendrites

17.4Thecerebellarcortexasaperceptron

17.5Cognitivefunctionsofthecerebellum

17.5.1Anatomicalconnectionsfrommostneocorticalregions 702

17.5.2Functionalconnectivityofdifferentcorticalsystemswithdifferentpartsof thecerebellum 703

17.5.3Activationofdifferentcerebellarcorticalregionsindifferenttasks 703

17.5.4Damagetodifferentpartsofthecerebellumcanproducedifferentcognitive, emotional,andmotorimpairments 703

17.5.5Neocortical–cerebellarcorticalcomputationsforcognition 703

17.6Highlights:differencesbetweencerebralandcerebellarcortexmicrocircuitry 707

18.1Introductionandoverview

18.2Thenoisycortex

18.2.1Reasonswhythebrainisinherentlynoisyandstochastic

18.2.2Attractornetworks,energylandscapes,andstochasticneurodynamics 714

18.2.3Amultistablesystemwithnoise 719

18.2.4Stochasticdynamicsandthestabilityofshort-termmemory 721

18.2.5Stochasticdynamicsindecision-making,andtheevolutionaryutilityofprobabilisticchoice 725

18.2.6Selectionbetweenconsciousvsunconsciousdecision-making,andfreewill 726

18.2.7Stochasticdynamicsandcreativethought 728

18.2.8Stochasticdynamicsandunpredictablebehavior 729

18.3Attractordynamicsandschizophrenia 729

18.3.1Introduction 729

18.3.2Adynamicalsystemshypothesisofthesymptomsofschizophrenia 730

18.3.3Reducedfunctionalconnectivityofsomebrainregionsinschizophrenia 733

18.3.4Beyondthedisconnectivityhypothesisofschizophrenia:reducedforward butnotbackwardconnectivity 734

18.4Attractordynamicsandobsessive-compulsivedisorder 738

18.4.1Introduction 738

18.4.2Ahypothesisaboutobsessive-compulsivedisorder 739

18.4.3Glutamateandincreaseddepthofthebasinsofattraction 741

18.5Depressionandattractordynamics 742

18.5.1Introduction

18.5.2Anon-rewardattractortheoryofdepression

18.5.3Theorbitofrontalcortex,andthetheoryofdepression

18.5.4Alteredconnectivityoftheorbitofrontalcortexindepression

18.5.5Activationsoftheorbitofrontalcortexrelatedtodepression

18.5.6Implications,andpossibletreatments,andsubtypesofdepression

18.5.7Maniaandbipolardisorder

18.6Attractorstochasticdynamics,aging,andmemory

18.6.1NMDAreceptorhypofunction

18.6.2Dopamineandnorepinephrine

18.6.3Impairedsynapticmodification

18.6.4Cholinergicfunctionandmemory

18.7Highbloodpressure,reducedhippocampalfunctionalconnectivity,andimpaired memory

18.8Braindevelopment,andstructuraldifferencesinthebrain

19.1Introductionandoverview

19.2Computationsthatcombinedifferentcomputationalsystemsinthebraintoproduce behavior

19.3Braincomputationcomparedtocomputationonadigitalcomputer

19.4Braincomputationcomparedwithartificialdeeplearningnetworks

19.5ReinforcementLearning

19.6Levelsofexplanation,andthemind-brainproblem

19.6.1Alevelsofexplanationtheoryofcausality,andtherelationbetweenthemind andthebrain

19.6.2DownwardorUpwardCausality?

19.6.3Consciousness-aHigherOrderSyntacticThoughttheory

19.6.4Levelsofexplanation,andlevelsofinvestigation

19.7Biologicallyplausiblecomputationinthebrain:agrandunifyingtheory?

19.8Brain-InspiredIntelligence

19.9.1Computationalpsychiatryandneurology

19.9.2Rewardsystemsinthebrain,andtheirapplicationtounderstandingfood intakecontrolandobesity

19.9.3MultipleRoutestoAction

19.10Primatesincludinghumanshavedifferentbrainorganisationthanrodents 796

19.10.1Thevisualsystem 796

19.10.2Thetastesystem 797

19.10.3Theolfactorysystem 798

19.10.4Thesomatosensorysystem 798

19.10.5Theauditorysystem 799

19.10.6Thehippocampalsystem,memory,andnavigation 799

19.10.7Theorbitofrontalcortexandamygdala 800

19.10.8Thecingulatecortex 801

19.10.9Themotorsystem 802 19.10.10Language 802

AIntroductiontolinearalgebraforneuralnetworks 803

A.1Vectors 803

A.1.1Theinnerordotproductoftwovectors 803

A.1.2Thelengthofavector 805

A.1.3Normalizingthelengthofavector 805

A.1.4Theanglebetweentwovectors:thenormalizeddotproduct 805

A.1.5Theouterproductoftwovectors 806

A.1.6Linearandnon-linearsystems 807

A.1.7Linearcombinations,linearindependence,andlinearseparability 808

A.2Applicationtounderstandingsimpleneuralnetworks 809

A.2.1Capabilityandlimitationsofsingle-layernetworks 810

A.2.2Non-linearnetworks:neuronswithnon-linearactivationfunctions 812

A.2.3Non-linearnetworks:neuronswithnon-linearactivations 813

BNeuronalnetworkmodels 815

B.1Introduction 815

B.2Patternassociationmemory 815

B.2.1Architectureandoperation 816

B.2.2Asimplemodel 818

B.2.3Thevectorinterpretation 821

B.2.4Properties 822

B.2.5Prototypeextraction,extractionofcentraltendency,andnoisereduction 825

B.2.6Speed 825

B.2.7Locallearningrule 826

B.2.8Implicationsofdifferenttypesofcodingforstorageinpatternassociators 831

B.3Autoassociationorattractormemory 832

B.3.1Architectureandoperation 832

B.3.2Introductiontotheanalysisoftheoperationofautoassociationnetworks 834

B.3.3Properties 836

B.3.4Dilutedconnectivityandthestoragecapacityofattractornetworks 843

B.3.5Useofautoassociationnetworksinthebrain 854

B.4Competitivenetworks,includingself-organizingmaps 855

B.4.1Function 855

B.4.2Architectureandalgorithm 856

B.4.3Properties 857

B.4.4Utilityofcompetitivenetworksininformationprocessingbythebrain 862

B.4.5Guidanceofcompetitivelearning 864

B.4.6Topographicmapformation 866

B.4.7Invariancelearningbycompetitivenetworks 870

B.4.8RadialBasisFunctionnetworks 871

B.4.9Furtherdetailsofthealgorithmsusedincompetitivenetworks 873

B.5Continuousattractornetworks 876

B.5.1Introduction 876

B.5.2Thegenericmodelofacontinuousattractornetwork 878

B.5.3Learningthesynapticstrengthsinacontinuousattractornetwork 879

B.5.4Thecapacityofacontinuousattractornetwork:multiplecharts 881

B.5.5Continuousattractormodels:pathintegration 882

B.5.6Stabilizationoftheactivitypacketwithinacontinuousattractornetwork 884

B.5.7Continuousattractornetworksintwoormoredimensions 886

B.5.8Mixedcontinuousanddiscreteattractornetworks 887

B.6Networkdynamics:theintegrate-and-fireapproach 888

B.6.1Fromdiscretetocontinuoustime 888

B.6.2Continuousdynamicswithdiscontinuities 889

B.6.3Anintegrate-and-fireimplementation 893

B.6.4Thespeedofprocessingofattractornetworks 894

B.6.5Thespeedofprocessingofafour-layerhierarchicalnetwork 897

B.6.6Spikeresponsemodel 900

B.7Networkdynamics:introductiontothemean-fieldapproach 901

B.8Mean-fieldbasedneurodynamics 902

B.8.1Populationactivity 903

B.8.2Themean-fieldapproachusedinamodelofdecision-making 905

B.8.3Themodelparametersusedinthemean-fieldanalysesofdecision-making 907

B.8.4Abasiccomputationalmodulebasedonbiasedcompetition 908

B.8.5Multimodularneurodynamicalarchitectures 909

B.9Interactingattractornetworks 911

B.10Sequencememoryimplementedbyadaptationinanattractornetwork 915

B.11Errorcorrectionnetworks 915

B.11.1Architectureandgeneraldescription 916

B.11.2Genericalgorithmforaone-layererrorcorrectionnetwork 916

B.11.3Capabilityandlimitationsofsingle-layererror-correctingnetworks 917

B.11.4Properties 920

B.12Errorbackpropagationmultilayernetworks 922

B.12.1Introduction 922

B.12.2Architectureandalgorithm 923

B.12.3Propertiesofmultilayernetworkstrainedbyerrorbackpropagation 927

B.13Deeplearningusingstochasticgradientdescent 928

B.14Deepconvolutionalnetworks 928

B.15ContrastiveHebbianlearning:theBoltzmannmachine 930

B.16DeepBeliefNetworks 931

B.17Reinforcementlearning 932

B.17.1Associativereward–penaltyalgorithmofBartoandSutton 933

B.17.2Rewardpredictionerrorordeltarulelearning,andclassicalconditioning 934

B.17.3TemporalDifference(TD)learning 935

B.18Learningintheneocortex 938

B.19Forgettingincorticalassociativeneuralnetworks,andmemoryreconsolidation 940

B.20Genesandself-organizationbuildneuralnetworksinthecortex 945

B.20.1Introduction 945

B.20.2Hypothesesaboutthegenesthatbuildcorticalneuralnetworks 946

B.20.3Geneticselectionofneuronalnetworkparameters 950

B.20.4Simulationoftheevolutionofneuralnetworksusingageneticalgorithm 952

B.20.5Evaluationofthegene-basedevolutionofsingle-layernetworks 961

B.20.6Thegene-basedevolutionofmulti-layercorticalsystems 964

B.20.7Summary 965

C.1Informationtheory 968

C.1.1Theinformationconveyedbydefinitestatements 968

C.1.2Informationconveyedbyprobabilisticstatements 969

C.1.3Informationsources,informationchannels,andinformationmeasures 970

C.1.4Theinformationcarriedbyaneuronalresponseanditsaverages 971

C.1.5Theinformationconveyedbycontinuousvariables 974

C.2Theinformationcarriedbyneuronalresponses 976

C.2.1Thelimitedsamplingproblem 976

C.2.2Correctionproceduresforlimitedsampling 977

C.2.3Theinformationfrommultiplecells:decodingprocedures 978

C.2.4Informationinthecorrelationsbetweencells:adecodingapproach 982

C.2.5Informationinthecorrelationsbetweencells:secondderivativeapproach 987

C.3Neuronalencodingresults 990

C.3.1Thesparsenessofthedistributedencodingusedbythebrain 991

C.3.2Theinformationfromsingleneurons 1002

C.3.3Theinformationfromsingleneurons:temporalcodesversusratecodes 1005

C.3.4Theinformationfromsingleneurons:thespeedofinformationtransfer 1008

C.3.5Theinformationfrommultiplecells:independenceversusredundancy 1019

C.3.6Shouldoneneuronbeasdiscriminativeasthewholeorganism? 1023

C.3.7Theinformationfrommultiplecells:theeffectsofcross-correlations 1025

C.3.8Conclusionsoncorticalneuronalencoding 1029

C.4Informationtheoryterms–ashortglossary 1033

C.5Highlights 1034

DSimulationsoftwareforneuronalnetworks,andinformationanalysis ofneuronalencoding 1035

D.1Introduction 1035

D.2Autoassociationorattractornetworks 1036

D.2.1Runningthesimulation 1036

D.2.2Exercises 1038

D.3Patternassociationnetworks 1038

D.3.1Runningthesimulation 1038

D.3.2Exercises 1040

D.4CompetitivenetworksandSelf-OrganizingMaps 1041

D.5Furtherdevelopments 1043

D.6MatlabcodeforatutorialversionofVisNet 1043

D.7Matlabcodeforinformationanalysisofneuronalencoding 1044

D.8Matlabcodetoillustratetheuseofspatialviewcellsinnavigation 1044

D.9TheAutomatedAnatomicalLabellingAtlas3,AAL3 1044

D.10TheextendedHumanConnectomeProjectextendedatlas,HCPex 1044