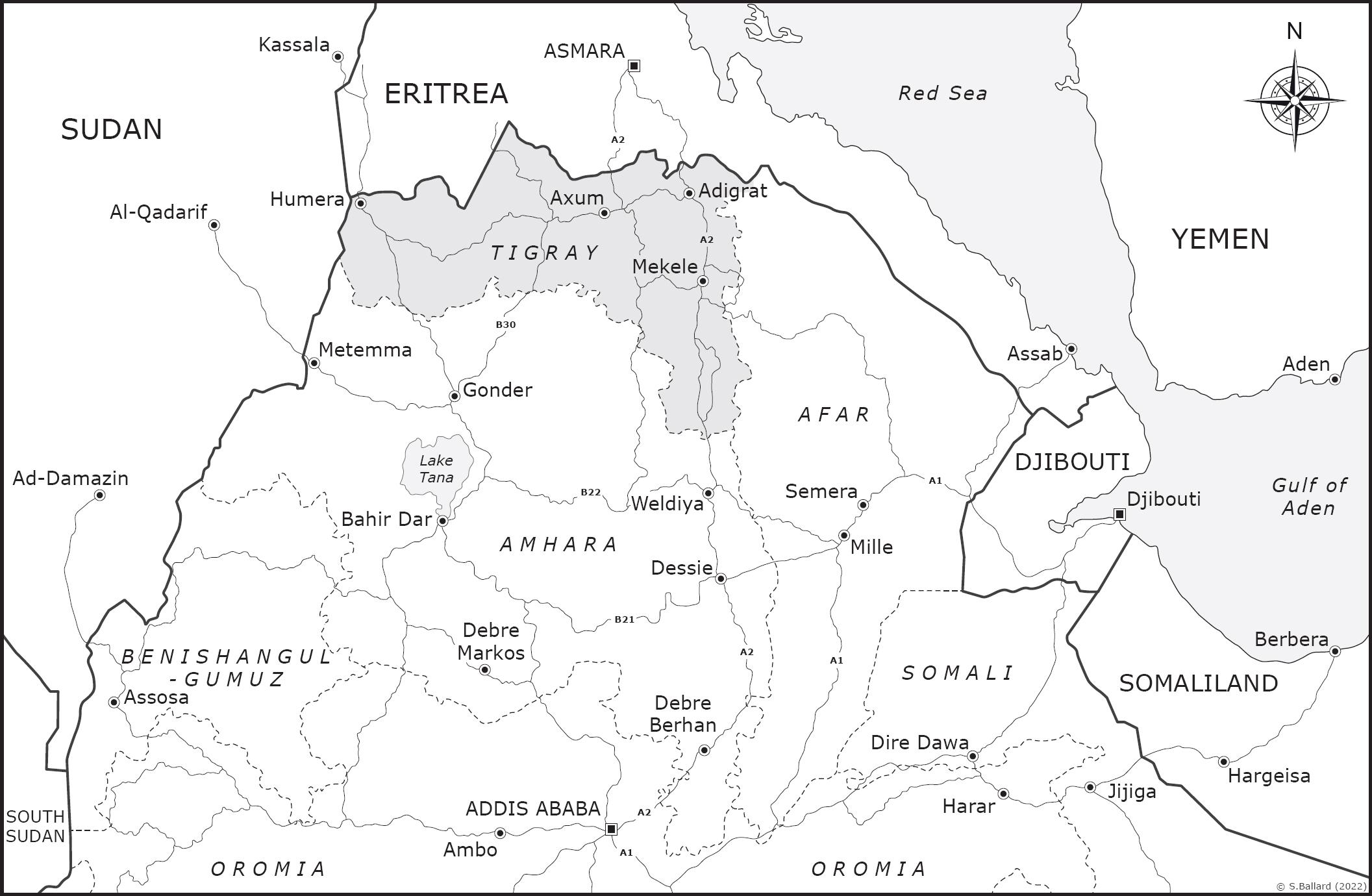

Map 2: Tigray Region and Adjacent Areas

Hatched areas to the south of Tigray indicates extent of Tigrayan advance towards Addis Ababa, November 2021. Areas under Eritrean control in northern Tigray are highlighted as well as areas in western Tigray under Ethiopian, Amhara and Eritrean forces.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

Aben National Movement of Amhara (NAMA)

ADFM Amhara Democratic Forces Movement

AGOA African Growth and Opportunity Act

ALA Agaw Liberation Army

ANDM Amhara National Democratic Movement

AU African Union

CUD Coalition for Unity and Democracy

EDORM Ethiopian Democratic Officers’ Revolutionary Movement

EDU Ethiopian Democratic Union

EFFORT Endowment Fund for the Rehabilitation of Tigray

EHRC Ethiopian Human Rights Commission

ELF

ENDF

EPDM

EPLF

EPRDF

EPRP

Eritrean Liberation Front

Ethiopian National Defence Force

Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement

Eritrean People’s Liberation Front

Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front

Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party

EU European Union

Ezema Movement of Ethiopians for Social Justice

FDRE Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

GHI Global Hunger Index

IDP internally displaced person

IGAD

Intergovernmental Authority on Development

INSA Information Network Security Agency

IOM International Organization for Migration

ISEN Institute for the Study of Ethiopian Nationalities

LPP Liberal Progressive Party

MSF

NAMA

Médecins Sans Frontières

National Movement of Amhara (Aben, in Amharic)

NISS National Intelligence and Security Service

OCHA

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

OFC Oromo Federalist Congress

OLA Oromo Liberation Army

OLF Oromo Liberation Front

OMN Oromo Media Network

ONLF Ogaden National Liberation Front

OPDO Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation

PFDJ Popular Front for Democracy and Justice

SEPDM Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement

SNNPRS Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Regional State

TDF

TLF

TPLF

Tigray Defence Forces

Tigray Liberation Front

Tigray People’s Liberation Front

UNFPA UN Population Fund

UNHCR UN High Commissioner for Refugees

VOA Voice of America

WPE Workers’ Party of Ethiopia

INTRODUCTION

LAND, POWER AND EMPIRE

SarahVaughan

andMartin Plaut

During the night of 3/4 November 2020, the first shots were fired in a brutal war between the government of the regional state of Tigray and the government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. On this single fact most accounts agree, but on little or nothing else. The dominant narrative of the war, pushed strongly by government spokespersons in Addis Ababa, is that it was a limited ‘law and order’ operation by the federal government and its allies to arrest a small group or ‘junta’ of rogue Tigrayans (soon labelled ‘terrorists’) in the northern regional state: the leaders of its ruling Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).

The war was—in the Ethiopian federal government’s view—the fault of this ‘traitorous gang’, an ‘illegal clique’ who had ‘treasonously’ attacked units of the Ethiopian national army stationed on their northern border with Eritrea. Seeing ‘a red line crossed’, the federal government then moved to ‘save the country and the region

from spiralling into instability’. The narrative of prime minister Abiy Ahmed’s government has been simple, clear, pervasive and persuasive. From the first hours of the war, it was repeated endlessly and, on the face of it, seemed to be widely believed by many Ethiopians and international observers: but, like the claim that the ‘operation’ would be completed within three weeks, the narrative was false. It disguised more than it illuminated.

The Ethiopian government and its allies’ occupation and devastation of Tigray in November and December 2020 had been long in the preparation and gestation. What the government portrayed as a treasonous plot by a faction in Tigray can also be seen as the result of the long-held ambition of their opponents to eliminate the Tigrayans as a political force. This plan, conceived at least partly in Eritrea, was further developed after 2018 together with Ethiopia’s newly appointed prime minister, Abiy, and others from Ethiopia, and also involved the government of Somalia. From the first, the conflict was more than just an Ethiopian civil war: Eritrean and Somali troops participated in the fighting. Their preparations were low-key, and some aspects of military planning were carefully concealed, although the rhetoric was not. What the Ethiopian premier insisted was a ‘domestic matter’ would soon be seen for what it was: a war involving international combatants from two neighbouring states, which at times threatened to embroil other Horn neighbours, including Sudan, Kenya and Djibouti.

Close observers knew that war was coming—and just how devastating it would be. Six months before it erupted, veteran Tigrayan exile and former military strategist Siye Abraha warned from the US that, if fighting were to start,

it will be a full-fledged war. No one will have any idea where it will end. We can already see the interference of foreign forces in our country and the war of words being waged on social media. We are seeing it daily, are we not? If we once allow real bullets to be added on top of this verbal violence, our entire country will degenerate into a cheap bar for the amusement of all our most meddling and insolent

neighbours. We will be inflicting harm on one another not just with words on social media but with kalashnikovs. Anyone who thinks it is safe to play with this kind of fire, counting on their tanks and heavy weaponry to be able to come out on top, will themselves get burned. These aren’t idle words: my warning is based on my personal experience of war, and what I know of the current situation in our region.1

Siye was right. The outbreak of hostilities came as a surprise to few close observers, but the ferocity of the onslaught was unexpected and appalled many. The war had been carefully prepared over several years, but its causes drew on wellsprings of bitterness and resentment deep in collective memories of the history and politics of the region. Many accounts would have it that the TPLF were simply ‘bad losers’: piqued to see their star waning after they had been displaced from power at the centre in 2018, and jealous of the neoliberal ‘reforms’ and ‘peace-making’ of the new prime minister, Abiy, a popular national leader and soon also a Nobel laureate. But the drivers of the war reach back far beyond the immediate period. In the minds of its protagonists they were entangled in long-standing patterns of power, land and empire across—and beyond—the Ethiopian state.

This book explores these historical memories and resources and their continuing relevance and remobilisation during the Tigray war. These apparently deep and intertwined roots make this a particularly intractable conflict. The war has brought a complex and shifting— constellation of allies into play on either side. Running centrally through the motivation for war is a profound dispute over the nature of the Ethiopian state and the balance of power across it: should Ethiopia be centralised at the national level, or decentralised and devolved to its constituent peoples, and how? Where should the balance of power lie? This argument itself has a long history and it mobilised interpretations of the history of a much longer period.

Complicating this central power struggle are a number of other dynamics: contemporary land hunger and the creation of

opportunities—and ‘historical’ excuses—for its forcible annexation; the desire for revenge and score-settling for past injustices, real or perceived; perceptions of the betrayal of promises of ‘reform’ or ‘inclusion’ under a new government established in 2018; and deeply entrenched historical stereotyping and socio-cultural prejudice. The sustainable resolution of the war depends on the emergence of a new equilibrium in the constellation of power, in the control of land, and in the shape of the Ethiopian empire state. Given the degree of controversy and polarisation that had become associated with each of these issues, this kind of outcome was increasingly hard to envisage in 2022. The weight of Ethiopian history suggests that settlement of such disputes could be (and usually was) ‘enforced’ by military means (at least for a cycle of thirty to fifty years). As a result, a negotiated consensus remained vanishingly unlikely throughout 2021 and into early 2022.

This book is about a current war and a long history. It situates the Tigray war in the context of an oscillating pattern of political power in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa: a pendulum swinging between centralising and decentralising influences over many decades— arguably in flux over millennia. One factor that distinguishes several of these areas of the Horn from much of the rest of sub-Saharan Africa is their close ties across the Red Sea. Several of the region’s cultures and languages are tied to the Arabian Peninsula and the wider Middle East. Parts of what are now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea were relatively unusual in having developed written languages and records over time. These allowed its elites and historians to trace (or reinvent) the roots of power back through the centuries in a way few other sub-Saharan African societies have been able to. It meant that rights and lineages could be traced and disputed down the generations, with apparently long-held divisions smouldering for years before being reinvented, reignited and fought over.

History is never over in Ethiopia, and the brutality of its contestation is a remarkably persistent pattern across enduring ‘frontiers of violence’.2 Richard Reid has explored ‘how force of arms was an extension of polity and economy, and a very practical instrument for construction as well as destruction; and how war was understood and interpreted, how military culture came to be imbued in society, and how the past was remembered in military terms’.3 Like Reid, the analysis of this book is ‘interested in both war as fact and war as image, war as policy alongside war as constructed truth’.4

The argument is not that Ethiopia’s violent history led inexorably to the Tigray war: it did not. It is rather that their different interpretations of Ethiopia’s history tended to lock the antagonists of the war into particular patterns of relations with one another. The point is not that one needs to understand Ethiopia’s history in order to understand Ethiopia’s Tigray war. Rather, one needs an understanding of the multiple ways in which different aspects of Ethiopia’s history have been differently understood by the contemporary parties to the war; and of how and why these different understandings made them antagonists. In a country as large, populous and diverse as Ethiopia, with such plural understanding of the significance of its history, generating this understanding is a complex business. This book is structured into five distinct parts designed to increase the accessibility of this intricate story.

Part One, ‘History’, recounts controversies over the essentials of Ethiopia’s long history which are centrally implicated in Ethiopians’ various understandings of the war in which the whole country is—to one degree or another—now embroiled. Part Two, ‘Living Memory’, examines the most recent cycle of political history, the evolution of the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) federal period from 1991 to 2018, during which the protagonists emerged. Part Three, ‘Path to War’, discusses the whirlwind drama of frenetic domestic change and regional political upheaval as tension mounted during the first two and a half years of Abiy Ahmed’s

premiership, from April 2018 to November 2020. Part Four, ‘War’, gives a detailed account of the outbreak of the conflict, and of the 14 months of military activity during 2020 and 2021. Finally, Part Five, ‘Impact of War’, looks at the devastating damage to society and economy primarily (but not only) in Tigray, at the humanitarian crisis caused by the way the war was waged, and at its diplomatic fallout internationally.

Tigray was a focus of empire during the early Axumite period (roughly 100–940 CE) when a growing trading power was centred on the towns of Yeha and Axum at the heart of the region. This apparently more centralised pattern of power dissipated, fractured and re-coalesced over the centuries. One focus of this fissiparous pattern shifted to Gonder, with Tigray again at the margins. In the nineteenth century a series of gradually centralising emperors again began an incremental process of consolidation away from the highly decentralised constellation of power of the so-called Era of Princes (1769–1855). Tigray was intimately involved in the processes by which the modern Ethiopian empire state was formed and its current borders established. After Emperor Tewodros’s suicide (r. 1855–68), Tigrayan emperor Yohannes IV (r. 1869–89) then consolidated Abyssinia’s western flank, defeating the Mahdist forces of Sudan in 1885.5

After his death, power shifted south to the province of Shewa from where Emperor Menelik II (r. 1889–1913) transformed the empire, producing approximately the borders of Ethiopia familiar today. Menelik had observed the imperial ambitions of European powers, and in a decade of military campaigning (1879–89) he expanded his direct and indirect rule over vast swathes of territory to the west, south and east of the highlands. Menelik’s Amhara and Oromo forces moved south-east and south-west to conquer the southern plateau and lowland peripheries, incorporating myriad Oromo, Southern and pastoral communities within Ethiopia’s borders. In so doing he incorporated dozens of new peoples, with

very different traditions. Many of his new subjects were Muslim, with cultures far removed from those of the predominantly Christian Orthodox highlands. Some had traditionally been enslaved by highland Ethiopians and were treated with the racism that slavery brings with it. The empire thus forcefully established ‘sowed the seeds of future conflicts’.6

Meanwhile, in the north, in March 1896, Ethiopian forces inflicted on Italy one of the few defeats by an African power on a European state at the famous battle at Adwa, blocking further Italian encroachment. Nevertheless, on 2 May 1889 Menelik II signed the treaty of Wuchale which recognised Italian rule over the coastal region of Eritrea. This saw the Tigrigna-speaking population of the northern highlands bifurcated along the Mereb River. The northern half remained—as Eritrea—under Italian occupation. The southern half, Tigray, became a new periphery broadly external to Ethiopia’s centre of power for the next century.

After the Second World War, Haile Selassie I (r. 1930–74) pushed through a second process of modernisation and centralisation which further curbed the power of the regional aristocracy and landowning classes that the nineteenth-century expansion had established. Under his rule Ethiopia also experienced a second Italian attempt to conquer Ethiopia (1935–41), which was eventually defeated with British help during the Second World War. In both Italian attempts to invade Ethiopia, Eritrean troops—known as ‘askaris’—fought alongside the Italians. They were conscripts, but their role in these wars was not forgotten.

A second chapter on history (Chapter 2) looks at the emergence of twentieth-century challenges to the empire. Emperor Haile Selassie moved incrementally in the middle decades of the twentieth century to undermine a compromise Ethio-Eritrean federation that had been cobbled together in the post-war period, and resentment began to coalesce as Eritrea was re-annexed. In 1961 the first shots were fired in Eritrea’s 30-year struggle for independence. During the feverish period of Marxist politics in the late 1960s and 1970s, emancipation and self-determination slogans swept like a contagion

through Ethiopia’s growing student movements. A new and radical generation of activists agreed on the need for reform of a ‘feudal’ socio-economic order, which would return land rights ‘to the tiller’. They disagreed violently over the prominence and power to be given to the different ‘national’ or ‘ethnic’ identities which made up the population. This visceral divide has riven Ethiopian politics ever since.

Rigid centralisation under the ageing emperor saw politics stagnate in the late imperial period, but the ‘creeping coup’ of 1974 brought a very different centralist government to power. The Derg (r. 1974–91), a military committee, espoused Marxism as a vehicle for mobilisation—domestically, but also in its post-1977 alliance with the Soviet Union. Radical land reform did much to diffuse popular opposition in rural areas, especially in the Oromo areas and the south of the country. Meanwhile an intensification of the Derg’s ‘Ethiopia first’ (Etyopia tikdem) rhetoric of pan-Ethiopian unitary nationalism and centralised control exacerbated a series of subnational conflicts. Nationalist and ethno-nationalist movements gradually gained momentum in different parts of the empire state: in Eritrea (annexed by Ethiopia in 1962 after a decade of federation), but now also in the Somali and Afar areas of the lowland east, in parts of Oromia, and along the far western borders with Sudan, in Sidama, and in Tigray.

The present Ethiopian state is a peculiar combination of African and European norms. On its northern Abyssinian plateau it evolved over the longueduréefrom a series of indigenous and long-standing political communities at its centre, very much along the lines of European states. At the peripheries, meanwhile, its borders look just as much the arbitrary result of nineteenth-century imperial expansion as elsewhere in Africa: in this case, competition between Emperor Menelik II and his Italian, British, French or Anglo-Egyptian neighbours.7 Communities living on Ethiopia’s peripheries straddled these arbitrarily drawn borders. In the context of Cold War competition, many drew on support from the neighbouring states of the Horn, breathing new life into a well-entrenched mantra

according to which ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’. Compared with the rest of the African continent, the Horn of Africa is home to a particularly high concentration of secessionist and irredentist claims. Many of these were fed by the unique history of modern Ethiopian state formation.8 Cold War competition made matters worse as the US and the Soviet Union juggled allies, and Eritrean anti-colonialism was infectious.

During the late 1970s and 1980s the remote mountainous areas of rural Tigray were home to a number of different kinds of movements all fighting the Derg government: remnants of the aristocracy seeking a return to the imperial order; a pan-Ethiopianist leftist opposition grouping; and the ethno-nationalist TPLF. Tigray and other parts of the north of Ethiopia experienced a devastating famine, greatly exacerbated—if not caused—by the manner of the Derg’s counterinsurgency strategy against the rebels. By the end of the 1980s the TPLF had forged an alliance with other groupings under the banner of the EPRDF. As support for the Derg from the Soviet bloc now began to fail, and the army was left reeling from an attempted coup in 1989, the military pendulum swung away from the centre. The EPRDF fought its way south in a tactical alliance with the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) of Isaias Afwerki. In coordinated EPRDF and Eritrean offensives, Asmara fell to the Eritreans on 24 May 1991; four days later Ethiopian rebel troops, supported by Eritrean artillery, captured Addis Ababa.

With Eritrea seceding de facto in 1991 (de jure after a referendum in 1993), the new EPRDF-led government in Addis Ababa now adopted a system of federalism based on the ‘selfdetermination of nations, nationalities and peoples’ in the Leninist phrase. Part Two of this book looks in closer detail at this most recent cycle of Ethiopia’s political history: the period well within living memory, from 1991 to 2018, during which the contemporary protagonists of the Tigray war began to evolve and their grievances deepened. Chapter 3 looks at the period from 1991 to 2012. Ethiopia’s system of multinational or ‘ethnic’ federalism drew

together representatives of many of the various language groups across Ethiopia which had—to one degree or another—opposed the Derg government. However, it excluded members of the Derg’s Workers’ Party of Ethiopia (WPE), along with key pan-Ethiopian nationalist organisations that had opposed them. These groups joined the new Eritrean government in condemning the federal arrangement as a system of ‘divide and rule’ that would weaken the Ethiopian state, along the lines of the former Yugoslavia, which in the early 1990s was disintegrating in violent fashion. The Derg’s imperial opponents and its victims had fled abroad during the 1970s; Derg officials now fled the EPRDF’s new federation, consolidating a vociferous and sustained diaspora opposition chorus.

Two blocs of domestic opposition to EPRDF and to federalism gradually emerged through the 1990s. Pan-Ethiopianist nationalists loathed the imposition of the federal arrangement, deriding it as intrinsically divisive and as undermining the narrative power of Ethiopia’s ancient history. Meanwhile, several of the other ethnonationalist groups which had also fought the Derg and also supported the federation were manoeuvred out of power by the ruling party in the 1990s. They complained that federal practice fell far short of constitutional principle; that it was in effect ‘fake’, serving as a cover for continued control by the centre, now under an EPRDF apparatus dominated by Tigrayan politicians. Important ethno-nationalist groups representing the Oromo, the Somali and the Sidama left government and returned to armed opposition.

By the early 2000s, the pan-Ethiopianist bloc launched a concerted process of political mobilisation in an attempt to unseat the ruling EPRDF. In highly contested elections in 2005, its parties won an overwhelming majority of seats in Addis Ababa and a number of other multi-ethnic cities, and a large number of seats also in Amhara and in the Gurage zone of the Southern region. Believing that the ruling EPRDF had stolen what it claimed was an overall national victory, pan-Ethiopianist opponents boycotted parliament, and the standoff ended in violence, mass arrests and prosecutions. Key nationalist leaders finally went abroad and joined their militant

ethno-nationalist colleagues in ‘armed struggle’, in many cases based in Eritrea.

Barely five years after Eritrean independence, relations between the new government in Asmara and the EPRDF Ethiopian government had soured and erupted into another brutal round of bloodletting along the northern border (1998–2000). In the cold-war standoff that followed the Ethio-Eritrean war, EPRDF’s political adversaries won military training and logistical support from an Eritrean government hostile to Addis Ababa and Mekele. Asmara had been stung by its military defeat in 2000; it seethed over Ethiopia’s refusal to cede the contested border town of Badme under the Algiers accords; and it resented the imposition of UN sanctions in 2009, in which it saw the hand of the TPLF-led Ethiopian government. Eritrea emerged as a third vehement opponent of federalism and of the TPLF, working consistently to undermine both.

Chapter 4 examines the period after the unexpected death of the Tigrayan EPRDF leader and prime minister, Meles Zenawi, in 2012. Between 2012 and 2018 the cohesion of the EPRDF began to dissolve and, under weaker leadership, differences between the four constituent fronts began to emerge. Mutual recrimination and jockeying between Amhara and Tigrayan politicians became particularly vicious—even if kept mostly away from the public eye. Claims about land and border disputes between the two regions were remobilised, and exacerbated tensions between the two blocs. Arguably the most significant of the policy problems of federalism began to become pressing: its static allocation of land between ethnically defined federated units. As Ethiopia’s economy and its population grew, pressure on arable land intensified, and nowhere more visibly than in and around the land-poor and densely populated regions of the old Abyssinian north. This included commercially valuable fertile land in the western peripheries (Gambella and Benishangul-Gumuz), but also—and explosively—in the border areas of western and southern Tigray. As demography and economy shifted, the federal dispensation did not. Ruling politicians in Amhara began to see this as a potential focus for

shoring up their popular support in the region, which the 2005 elections had exposed as shaky.

Political mobilisation in several of the EPRDF-administered regions had been relatively cautiously managed during the 1990s and 2000s. It now began to take on an overtly and competitively ethnicised tone, as regional politicians sought shortcuts to bolster their constituencies as power at the centre began to fracture.

Amhara’s EPRDF ruling politicians faced new challenges from ethnonationalist competitors, eventually including a new National Movement of Amhara (NAMA). A newly ethnicised vision of Amhara interests emerged, at variance with an older generation of nationalists who had elided their interests with the Ethiopian empire state. Meanwhile, after 2014, Oromo street protests began to spread, driven by a combination of savvy diaspora social media agitation and tacit facilitation from Oromo ruling party politicians. Like their Amhara peers, they were newly keen to flex their muscles and leverage their large constituency at the centre of the country, no longer constrained by a powerful Tigrayan premier. By early 2018 a moribund, weakened centre and a fragmenting ruling EPRDF had no answers to the groundswell for change.

Part Three of the book (‘Path to War’) looks at the extraordinary convulsion of the politics of Ethiopia and the Horn after the appointment of Abiy Ahmed as prime minister in April 2018. Chapter 5 describes the dramatic series of revolutions in domestic politics; and Chapter 6 examines the new international military alliances which paved the road to war just over two and a half years later. By the time Ethiopia’s prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn (2012–18) resigned in February 2018, the rise of Oromo nationalism meant that his successor could only be an Oromo, and Abiy rode to power on this carefully cultivated wave. In a remarkable irony, however, the appointment of the new prime minister served also to elevate the interests of pan-Ethiopian nationalists, who quickly returned from exile. They brought with them highly effective satellite TV and radio broadcast outlets, which now began to transmit a long-standing diaspora barrage of anti-TPLF and anti-federal narratives into the

homes of millions of Ethiopians. These entrenched division and whipped up prejudice and hostility.

The new prime minister’s facility with language meant that he was able to win over different constituencies with different narratives. Ambiguity became confusion as his rhetoric became more unitary and nationalist. Ethno-nationalist competitors and supporters of federalism who had also returned were gradually marginalised, jailed or manoeuvred out in a series of dramatic shifts through 2019 and 2020—especially but not only in Oromia. When a new unitary national ruling Prosperity Party was formed in late 2019, ‘proFederalist’ opposition began to coalesce around the TPLF, which refused to join it. The TPLF had increasingly drawn in its horns after 2018, members returning to its home region as its influence at the centre decreased and its record and leaders were attacked. From the start of the new government a sustained campaign of scapegoating the TPLF leadership for the collective sins of the EPRDF period embittered relations. When the federal government and Tigray government fell out over the legality of postponing elections beyond the constitutionally defined term, Addis Ababa cut funding flows. Meanwhile, there had also been a seismic shift in the geopolitics of the Horn. The new prime minister upturned a regional political constellation which had persisted since the 1990s, forging alliances with Asmara and Mogadishu and, in the process, releasing the Eritrean regime from a decade of international sanctions. The new constellation united three heads of government known to favour strong centralisation over the more devolved arrangements which had persisted in Somalia and Ethiopia—three antagonists of the TPLF and the system of federalism they had instituted. In February 2018 Eritrean president Isaias Afwerki declared ‘game over!’ for the TPLF, which he loathed, and the new tripartite alliance set about bolstering its military and security cooperation. The stage was set for a showdown.

Ethiopia’s war in Tigray is the latest in a long series of rounds of competition for control of the Ethiopian state, and between centralising and decentralising forces. Tracing the roots of these

conflicts in what has gone before, however, does not mean that the war that erupted in November 2020 was unavoidable or somehow dictated by history. Nor was this return to violence inherent in a system of federalism which recognised the self-determination of ‘ethnic’ or linguistic groups. As the discussion of history in Part One of the book illuminates, the thoroughgoing politicisation of Ethiopia’s multiple identities had long been a feature of the country’s political evolution, since before the modern empire state was established in the nineteenth century. Rather, the war that erupted at the beginning of November 2020 was the result of active choices by contemporary politicians in Ethiopia and its neighbours in the Horn. The new upsurge in the manufacture and mobilisation of ‘ethnic hatreds’ may draw on perceptions of deep historical division, but it was set in train by the contemporary calculations of political elites. Things could have been otherwise.

Part Four of the book gives the first detailed account of the fighting itself: the military trajectories of the war from the beginning of November 2020 until the end of the following year. A pair of chapters look at the two major phases of the ebb and flow of the military conflict. Chapter 7 describes the Ethiopian federal government and its allies’ rapid defeat and subjugation of Tigray in the last two months of 2020, and a gradual fightback from the Tigrayan forces which saw federal forces ousted from much of eastern and central Tigray by the end of June 2021. A second military phase (Chapter 8) saw an equally dramatic ebb and flow of military fortunes, as forces loyal to the Tigray government gradually pushed south into Afar and Amhara in the second half of the year, occasionally linking up with federalist allies. They came within a hundred miles of the capital Addis Ababa, before abruptly pulling their forces north again in late November 2021, in the face of overwhelming airpower, particularly from Addis Ababa’s newly purchased armed drones.

If the war was widely expected for many months before it began, its consequences have been extraordinarily devastating, particularly (but not only) for the civilian population of Tigray. The exceptionally

damaging civilian impact of the war seems to have been, at least in part, a function of the way in which it was waged: with extremist calls to erase even the memory of the TPLF and ‘those who resemble them’ beyond the recovery of later researchers. Part Five of the book explores three aspects of the concrete impact of the war in Tigray: its socio-economic devastation (Chapter 9); the deliberate starvation of its population by means of a strategy of siege warfare (Chapter 10); and the fallout in terms of diplomacy and advocacy (Chapter 11). At the beginning of 2020, an anonymous author had commented:

Victory is virtually impossible in the likely Ethiopian scenario of multi-dimensional infighting among relatively symmetrical forces. We would be fighting each other, brother against brother, neighbour against neighbour. The costs would be astronomical in human and material terms. And, the bigger risk is not just the collapse of Ethiopia as a federation, but a perpetual state of war where no faction can win. We are seeing that in Libya and Yemen, we see it in Syria, in Afghanistan, and in other places.9

Hugo Slim has recently observed that ‘most people experience war as poverty rather than as battle … It is the civilian, not the wounded soldier, who stands at the centre of the moral frame we put around war.’10 In Tigray, civilians have experienced both violence and impoverishment in quick succession: a devastatingly brutal period of military occupation, characterised by extrajudicial executions of civilians, systematic rape, ethnic cleansing, and the wholesale destruction and looting of the means of survival; followed by a year (at the time of writing in mid-2022) not just of poverty but of starvation, as the Ethiopian government subjected the region to what the United Nations called a ‘de facto blockade’. But these desperate civilians have not been at the centre of the moral frame placed around the war by the international community. Their experiences have been silenced and ‘invisibilised’—rendered ‘ungrievable’11—by Ethiopia’s systematic media, telecommunications

and internet blackout. If nothing else, this book is an attempt to understand something of the disaster that has befallen them.