FundamentalsofComputational Neuroscience

ThirdEdition

ThomasP.Trappenberg DalhousieUniversity

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

c OxfordUniversityPress2023

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin2002

SecondEditionpublishedin2010

ThirdEditionpublishedin2023

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY100106,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2022943170

ISBN978–0–19–286936–4

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192869364.001.0001

PrintedintheUKby

AshfordColourPressLtd,Gosport,Hampshire LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Preface

Computationalneuroscienceisstillayounganddynamicallydevelopingdiscipline, andsomechoiceoftopicsandpresentationstylehadtobemade.Thistextintroduces somefundamentalconcepts,withanemphasisonbasicneuronalmodelsandnetwork properties.Incontrasttothecommonresearchliterature,thisbookistryingtopaint thelargerpictureandtriestoemphasizesomeoftheconceptsandassumptionsfor simplificationsusedinthescientifictechniqueofmodelling.

ComputationalneuroscienceandArtificialIntelligence(AI)areclosecousins. ThetermAIissaidtobeinventedattheDartmouthworkshopin1956withmany famousparticipantsincludingpsychiatristRossAshby,theneurophysiologistWarren McCullochwhocreatedoneofthefirstmathematicalneuronmodels,andArthur Samuel,oneofthepioneersinreinforcementlearning.Computationalmodelsof neuralsystemssuchasmodelsofneuronsaremucholder,butconnectinglearningand cognitivesystemscreatedexcitementoverthepossibilitytobetterunderstandmind. Theinventionoflearningmachineshasrevolutionizedmanyapplicationsasrecently seeninthedramaticprogressofmachinevisionandnaturallanguageprocessing throughdeeplearning.

Whiletherehasbeenmuchrecentprogressinmachinelearning,researchersinthis areaoftenwonderhowthebrainworks.Itsometimesseemsthatscientificprogress oscillatesbetweencomputationalneuroscienceandmachinelearning.Forexample, theprogressofneuralnetworksandstatisticallearningtheoryinthelater1980sand early1990swasfollowedbyenormousactivitiesincomputationalneuroscienceinthe 1990sandearly2000s.Forthelastdecade,deeplearninghasoccupiedanexplosive growthinmachinelearninganddatascience,andnowthetimeseemsripeformore renewedinterestinlookingmorecloselyatthebrainforinspirationstogodeeper.This isfuelledbytheincreasingrealizationoflimitationsofdeeplearning,inparticular withthechallengeoflearningsemanticknowledgewithlimiteddataandtheabilityto transferknowledgetosituationsthatarenotdirectlyrepresentedinthelearningset.

Inthisneweditionofmybook,Itriedtoincorporatemanyoftherecentlessons fromdeeplearning.Whilethereareexcellentbooksondeeplearning,ouremphasishereistheirconnectiontobrainprocessing.Animportantaspectistherebythe conceptsofrepresentationallearningandcomputationwithuncertainties.Also,Inow includedgatedrecurrentneuralnetworksthatarebecominganimportantfundamental mechanismswhenthinkingaboutbrainprocessing.Whilewewillnotbeabletodive intoalltherecentprogress,Ihopethatthetextwillguidefurtherspecificstudiesand research.Furthermore,itwasimportantformetostreamlinetheexistingtext.Ihope thatIimprovedthereadabilityofsomeofthetextandevenremovedpartsthatseem lessrelevanttostudythemostbasicfundamentals.

Thethemesincludedinthisbookarechosentoprovidesomepaththroughthe differentlevelsofdescriptionofthebrain.Chapter1providesahigh-leveloverview andsomefundamentalquestionsaboutbraintheories,abriefdiscussionaboutthe

roleofmodelling,andsomebasicneurosciencefactsthatareusefultokeepinmind forlateruse.WealsoreviewtheessentialscientificprogramminginPythonandthe basicmathematicalandstatisticalconceptusedinthebook.Chapters2–4focuson basicmechanismsandmodellingofsingleneuronsorpopulationaverages.Thisstarts fromafairlydetaileddiscussionofchangesinthemembranepotentialsthroughion channels,spikegenerations,andsynapticplasticity,withincreasinglyabstractionsin thefollowingchapters.Chapters5–7describetheinformation-processingcapabilities ofbasicnetworks,includingfeedforwardandcompetitiverecurrentnetworks.Thelast partofthebookdescribessomeexamplesofcombiningsuchelementarynetworksas wellassomeexamplesofmoresystem-levelmodelsofthebrain.

Mostmodelsinthebookarequitegeneralandareaimedatillustratingbasic mechanismsofinformationprocessinginthebrain.Intheresearchliterature,thebasic elementsreviewedinthisbookareoftencombinedinspecificwaystomodelspecific brainareas.Ourhopeisthatthestudyofthebasicmodelsinthisbookwillenablethe readertofollowsomeoftherecentresearchliteratureincomputationalneuroscience.

Whilewetriedtoemphasizesomeimportantconcepts,wedidnotwanttogivethe impressionthatthechosenpathistheonlydirectionincomputationalneuroscience. Therefore,wesometimesmentionconceptswithoutextensivediscussion.Thesecommentsareintendedtoincreasethereader’sawarenessofsomeissuesandtoprovide somekeywordstofacilitatefurtherliteraturesearches.Also,whilesomeexamplesof specificbrainareasarementionedinthisbook,acomprehensivereviewofmodelsin computationalneuroscienceisbeyondthescopeofthistext.Wedonotclaimthatthis bookcoversallaspectsofcomputationalneurosciencenordoweclaimittobethe onlyapproachtothisarea,butwehopethatitwillcontributetothediscussion.

Mathematicalformulas

Thisbookincludesmathematicalformulasandconcepts.Weusemathematicallanguageandconceptsstrictlyaspracticaltoolsandtocommunicateideasincontrastto usingsuchformalismformathematicalproofs.Wetherebytriedtobalancedetailed mathematicalnotationswithreadabilityandcommunicatingthebasicconcepts.From readerswithlessextensivetraininginsuchformalsystemsIaskforpatience.Wedid nottrytoavoidmathematicalformulationssincesuchnotationsallowabrevityin communicationthatwouldbelengthywithplainwrittenlanguage.Thechosenlevelof mathematicaldescriptionsaremainlyintendedtobetranslateddirectlyintoprograms andotherquantitativeevaluations.

Thereisnoreasontobeafraidofformulas,anditisimportanttoseebeyondthe symbolsandtounderstandtheirmeaning.Manymathematicsnotationsareinvented tosimplifydescriptions.Thisincludestheuseofvectorsandmatrices,whichwill drasticallyshortenthespecificationofnetworkmodels.Weprovidereviewchaptersin thefirstpartofthebooktoreviewsuchnotations.Werecommendsometutorialson suchmaterialstoallowstudentstomovebeyondthesetechnicalitiesinthemaintext.

Mostmodelsinthisbookdescribethechangeofaquantitywithtime,suchas thechangeofamembranepotentialaftersynapticinputorsynapticstrengthvalues overtimeduringlearning.Equationsthatdescribesuchchangesarecalleddifferential equations.Acomprehensiveknowledgeofthetheoryofdifferentialequationsisnot requiredforunderstandingthisbook.However,discussingtheconsequencesofspecific

differentialequationsandsimulatingthemwithcomputerprogramsisattheheartof thisbook.Ihopeourtreatmentwillencourageanewlookintoatopicthatsometimes seemsoverwhelmingwhentreatedinspecializedclasses.Wewillspecificallybecome familiarwithasimpleyettellingexampleofadifferentialequation,thatofaleaky integrator.Abasicknowledgeofthenumericalapproachestosolvingdifferential equationsisessentialforthisbookandmanyotherdynamicmodellingapproaches. Thus,wealsoincludeareviewofdifferentialequationsandtheirnumericalintegration.

Anothermathematicaltheory,thatofrandomnumbers,isalsoreviewedinthe thirdchapter.Thelanguageofprobabilitytheoryisveryusefulincomputational neuroscienceandshouldbetaughtinsuchacourse.Inneuroscience(asinother disciplines),weoftengetdifferentvalueseachtimeweperformameasurement,and randomnumbersdescribesuchsituations.Weoftenthinkofthesecircumstancesas noise,butitisalsousefultothinkaboutrandomvariablesandstatisticsinterms ofdescribinguncertainties.Indeed,itcanbearguedthatlearningandreasoningin uncertaincircumstancesisafundamentalrequirementofthebrain.Wewillarguethat mentalfunctionscanbeviewedasprobabilisticreasoning.

Programmingexamples

Whilethisbookincludesafewexamplesofpowerfulanalyticaltechniquestogive thereaderaflavourofsomeofthemoreelaboratetheoreticalstudies,notevery neuroscientisthastoperformsuchcalculationsthemselves.However,studyingsome ofthegeneralideasbehindthesetechniquesisessentialtobeabletogetsupportfrom thosewhospecializeinsuchtechniques.Inparticular,itisinstructivewhenstudying thisbooktoperformsomenumericalexperimentsyourself.Wethereforeincluded anintroductiontoamodernprogrammingenvironmentthatisverymuchsuitedfor manyofthemodelsinneuroscience.Writingprogramsandcreatingadvancedgraphics canbelearnedeasilywithinashorttime,evenwithoutextensivepriorprogramming knowledge.

TheprogramsinthisbookarenowprovidedinPythontoimproveaccessibility andduetoPython’sincreasingimportanceinmachinelearninganddatascience. Whileitwaschallengingtobalanceascientist’sapproachofmakingminimalistand cleanexampleswithcommonprogrammingapproaches,IhopethatIfoundsome balance.Commentsinprogramsareoftenagoodideaincomplexsoftwarepackages. However,thesituationisdifferenthere.Theprogramsarepurposefullykeptshortand theexpectationisthateachlineshouldbereadandunderstoodentirely.Forexample, wethinkthatcommentslike #assigningvaluebtovariablea todescribe thecode a=b shouldnotbenecessary.Instead,thereadershouldstrivetobeableto readthecodedirectly.Commentsintheprogramwerethereforedeliberatelyavoided excepttoexplainsomevariablenamestokeepthevariablenamesshort,andsome commentstostructurethecode.Manypeoplehavedifferentstylesofcoding,andthe styleheretrieddeliberatelytostriveforcompactnessandsimplicity.Whileitmight beanewlanguageforsome,tryingtounderstandeachlineinaprogramwillhelpto masterprogramminginashorttime.

References

Thisbookdoesnotprovideahistoricalaccountofthedevelopmentofideasincomputationalneuroscience.Indeed,extensivereferenceshavebeenavoidedwherepossible toconcentrateondescribingfundamentalideas.Thisishencemoreconsistentwith coursetextbooks.Referencestotheoriginalresearchliteratureareonlyprovidedwhen followingcorrespondingexamplesclosely.Thetextisverymuchaimedatproviding astartingplaceforfurtherstudies,andsearchengineswillnoweasilyprovidefurther directions.

I Background

1Introductionandoutlook

Thisintroductorychapterisoutliningthebigpicture.Wedefinethescopeofthe computationalneurosciencediscussedinthisbookandoutlinesomebasicfactsof brainorganizationandprinciplesthatweencounterinlaterchapters.Thischapter includesadiscussionontheroleofscientificmodellingingeneralandinneuroscience specifically.Inaddition,weoutlineahigh-leveltheoryofthebrainasapredictivemodel oftheworld,andweoutlinesomeprinciplesthatwillguidemuchofthediscussions inthisbook.

1.1Whatiscomputationalneuroscience?

Computationalortheoreticalneuroscienceusesdistincttechniquesandasksspecific questionsaimedatadvancingourunderstandingofthenervoussystem.Abriefdefinitionmightbe:

Computationalneuroscienceisthetheoreticalstudyofthebrainusedtouncovertheprinciplesandmechanismsthatguidethedevelopment,organization, informationprocessingandmentalabilitiesofthenervoussystem.

Mostpapersincomputationalneurosciencejournalsfollowoneoftwoquitedifferentprincipledirections.Onedirectionistheuseofcomputationalmethodstoanalyses datasuchassortingspikesortoquantitativelytesthypothesis.Inthiscontext,methods fromAI(ArtificialIntelligence)suchasmachinelearningtechniquesarenowoften includedastoolsfordataanalytics.Wewillencountersuchtechniques,specifically thatofneuralnetworksanddeeplearning.However,ourfocushereislessondescribingdataanalyticsmethodsbutrathertobuildmodelsofbrainfunctionstounderstand itsprocessingcapabilities.Thetypeofcomputationalneurosciencedescribedinthis bookishencemostlysynonymouswiththeoreticalneuroscienceinthatwedevelop andtesthypothesesofthefunctionalmechanismsofthebrain.

Weoftenusecomputersimulationsinourstudies,though‘computational’highlightsmorebroadlyourinterestedinthecomputationalandinformation-processing aspectsofbrainfunctions.Amainfocusinthisbookishencethedevelopmentand evaluationofbrainmodels,ormodelsofspecificfunctionsofthebrain.Theseare importanttosummarizeknowledge,toquantifytheories,andtotestcomputationalhypotheses.Wefocustherebyonfundamentalmechanismsandmechanisticfoundations whichseemtobeunderlyingbrainprocesses.Wealsotrytohighlightsomeemerging principlesofbrain-styleinformationprocessing.Thisbookdoesclaimacomprehensivetheoryofthemind.However,wehopethatlearningthesefundamentalswillbean importantpartoffurtherdevelopments.

1.1.1Embeddingwithinneuroscience

Computationalneuroscienceisaspecializationwithinneuroscience.Neuroscience itselfisascientificareawithmanydifferentaspects.Itsaimistounderstandthenervous system,inparticularthe centralnervoussystem andthespinethatwecallthebrain. Thebrainisstudiedindiversedisciplinessuchasphysiology,psychology,medicine, computerscience,andmathematics.Neuroscienceemergedfromtherealizationthat interdisciplinarystudiesarevitaltofurtherourunderstandingofthebrain.While considerableprogresshasbeenmadeinourunderstandingofbrainfunctions,there aremanyopenquestionsthatwewanttoanswer.Whatisthefunctionofthebrain andhowdoesitachieveitstask?Whatarethebiologicalmechanismsinvolved? Howisitorganized?Whataretheinformation-processingprinciplesusedtosolve complextaskssuchasperception?Howdidthebrainevolve?Howdoesitchange duringthelifetimeoforganisms?Whatistheeffectofdamagetoparticularareasand thepossibilitiesofrehabilitation?Whataretheoriginsofdegenerativediseasesand possibletreatments?Thesearequestionsaskedbyneuroscientistsinmanydifferent subfields,usingamultitudeofdifferentresearchtechniques.

Manytechniquesareemployedinneurosciencetostudythebrain.Thosetechniquesincludegeneticmanipulations,recordingofcellactivitiesinculturedcells, brainslices,opticalimaging;non-invasivefunctionalimaging,psychophysicalmeasurements;andcomputationalsimulations,tonamebutafew.Eachofthesetechniques iscomplicatedandlaboriousenoughtojustifyaspecializationofneuroscientistsinparticulartechniques.Therefore,wespeakofneurophysiologists,cognitivescientists,and anatomists.Itis,however,vitalforanyneuroscientisttodevelopabasicunderstanding ofallmajortechniques,soheorshecancomprehendandutilizethecontributions madewithinthesespecializations.Computationalneuroscienceisarelativenewarea ofneurosciencewithincreasingimportance.Itfillsanimportantroleinquantifying theoriesbasedontheincreasingamountofexperimentaldiscoveries.Abasiccomprehensionofthecontributionthatcomputationalneurosciencecanmakeisbecoming increasinglyimportantforallneuroscientists.

Withincomputationalneuroscienceweoftenusecomputers,althoughotherareas ofneuroscienceusecomputers.Ourmainreasonforusingcomputersisthatthe complexityofmodelsinthisareaisoftenbeyondanalyticaltractability.Forsuch modelswehavetoemploycarefullydesignednumericalexperimentstobeableto comparethemodelstoexperimentaldata.However,wedonotneedtorestrictour studiestothistool.Somemodelsareanalyticallytractableormightbedeliberately simplifiedtobeanalyticallytractable.Suchmodelsoftenprovideadeepandmore controlledinsightintothefeaturesofcertainmechanismsandthereasonsbehind numericalfindings.

Althoughcomputationalneuroscienceistheoreticalbyitsverynature,itisimportanttobearinmindthatmodelsmustbegaugedonexperimentaldata;theyare otherwiseuselessforunderstandingthebrain.Onlyexperimentalmeasurementsofthe realbraincanverify‘what’thebrainactuallydoes.Incontrasttotheexperimental domain,computationalneurosciencetriestospeculate‘how’thebrainoperates.Such speculationsaredevelopedintohypotheses,realizedintomodels,evaluatedanalyticallyornumerically,andtestedagainstexperimentaldata.Also,modelscanoftenbe usedtomakefurtherpredictionsabouttheunderlyingphenomena.

1.2Organizationinthebrain

Mentalfunctionssuchasperceptionandlearningmotorskillsarenotaccomplished bysingleneuronsalone.Thesefunctionsareanemergingpropertyofspecialized networkswithmanyneuronsthatformthenervoussystem.Thenumberofneuronsin thecentralnervoussystemisestimatedtobeontheorderof 1012,anditisdemanding toexploresuchvastsystemsofneurons.Therefore,ratherthantryingtorebuildthe braininallitsdetailonacomputer,weaimtounderstandtheprincipalorganization ofbrainsandhownetworksofneuron-likeelementscansupportandenableparticular mentalprocesses.Integrationofneuronsintonetworkswithspecificarchitecturesseem tobeessentialforsuchskills.Wewillexplorethecomputationalabilitiesofseveral principalarchitecturesofneuralnetworksinthisbook.

Athoroughknowledgeoftheanatomyofthebrainareaswewanttomodelisessentialforanyresearchthatattemptstounderstandbrainfunctions.However,although recentresearchhasrevealedmanyimportantfactsaboutneuralorganization,itisstill oftendifficulttospecifyallthecomponentsofamodelonthebasisofanatomical andphysiologicaldataalone,andplausibleassumptionshavetobemadetobridge gapsintheknowledge.Evenifwecandrawonknowndetails,itisoftenusefulto makesimplifyingassumptionsthatenablecomputationaltractabilityorthetracingof principalorganizationssufficientforcertainfunctionalities.Itisbeyondthescopeof thisbooktodescribeallthedetailsofneuronalorganization,andmorespecialized booksandresearcharticleshavetobeconsultedforspecificbrainareas.Theaimof thefollowingsectionistooutlinealargevarietyoffactsmainlytoraiseawarenessof themanyfactorsofstructuresandorganizationsinthebrain.Incomputationalneurosciencewehaveaconstantstrugglebetweenincorporatingasmanydetailsaspossible whilekeepingmodelssimpletoilluminatetheprinciplesbehindbrainfunctions.We hopethatthissectionwillencouragemorespecificstudiesofbrainanatomy.

1.2.1Levelsoforganizationinthebrain

Modelsincomputationalneurosciencecantargetmanydifferentlevelsofdescriptions. Thisinitselfisaconsequenceofthefactthatthenervoussystemhasmanylevelsof organizationonspatialscalesrangingfromthemolecularlevelofafewAngstrom (1 ˚ A=10 10m),tothewholenervoussystemonthescaleofoverametre.Biological mechanismsonalltheselevelsareimportantforthebraintofunction.

DifferentlevelsoforganizationinthenervoussystemareillustratedinFig.1.1. Animportantstructureinthenervoussystemistheneuron,whichisacellthat isspecializedforsignalprocessing.Dependingonexternalconditions,neuronsare abletogenerateelectricpotentialsthatareusedtotransmitinformationtoother cellstowhichtheyareconnected.Mechanismsonasubcellularlevelareimportant forsuchinformationprocessingcapabilities.Neuronsusecascadesofbiochemical reactionsthathavetobeunderstoodonamolecularlevel.Theseinclude,forexample, thetranscriptionofgeneticinformationwhichinfluencesinformation-processingin thenervoussystem.Manystructureswithinneuronscanbeidentifiedwithspecific functions.Forexample,mitochondriaarestructuresimportantfortheenergysupplyin thecell,andsynapsesmediateinformationtransmissionbetweencells.Thecomplexity ofasingleneuron,andevenisolatedsubcellularmechanisms,makescomputational

Levels of Organization

studiesessentialforthedevelopmentandverificationofhypotheses.Itispossibletoday tosimulatemorphologicallyreconstructedneuronsingreatdetail,andtherehasbeen muchprogressinunderstandingimportantmechanismsonthislevel. CNS System Maps

map

Compartmental model

Fig.1.1 Somelevelsoforganizationinthecentralnervoussystemondifferentscales[adapted fromChurchlandandSejnowski, Thecomputationalbrain,MITPress(1992)].

However,singleneuronscertainlydonottellthewholestory.Neuronscontacteach otherandtherebycomposenetworks.Asmallnumberofinterconnectedneuronscan exhibitcomplexbehaviourandenableinformation-processingcapabilitiesnotpresent inasingleneuron.Understandingnetworksofinteractingneuronsisamajordomainin computationalneuroscience.Networkshaveadditionalinformation-processingcapabilitiesbeyondthatofsingleneurons,suchasrepresentinginformationinadistributed way.Anexampleofabasicnetworkistheedgedetectorformedfromacentre-surround neuronasproposedbyHubbleandWiesel.Theillustratedlevelsabovethelevellabelled‘Networks’inFig.1.1arealsocomposedofnetworks,yetwithincreasingsize andcomplexity.Anexampleontheleveltermed‘Maps’inFig.1.1isaself-oganizing topographicmap,whichispartofanimportantdiscussioninthisbook.

Theorganizationdoesnotstopatthemaplevel.Networkswithaspecificarchitectureandspecializedinformation-processingcapabilitiesarecomposedintolarger structuresthatareabletoperformevenmorecomplexinformation-processingtasks. System-levelmodelsareimportantinunderstandinghigher-orderbrainfunctions.The centralnervoussystemdependsstronglyonthedynamicinteractionofmanyspecializedsubsystems,andtheinteractionofthebrainwiththeenvironment.Indeed,wewill seelaterthatactiveenvironmentalinteractionsareessentialforbraindevelopmentand

function.

Althoughanindividualresearchertypicallyspecializesinmechanismsofacertainscale,itisimportantforallneuroscientiststodevelopabasicunderstandingand appreciationofthefunctionalitiesofdifferentscalesinthebrain.Computationalneurosciencecanhelptheinvestigationsatalllevelsofdescription,anditisnotsurprising thatcomputationalneuroscientistsinvestigatedifferenttypesofmodelsatdifferent levelsofdescription.Computationalmethodshavelongcontributedtocellularneuroscience,andcomputationalcognitiveneuroscienceisnowarapidlyemergingfield.The contributionsofcomputationalneuroscienceare,inparticular,importanttounderstand non-linearinteractionsofsubprocesses.Furthermore,itisimportanttocomprehend theinteractionsbetweendifferentlevelsofdescription,andcomputationalmethods haveprovenveryusefulinbridgingthegapbetweenphysiologicalmeasurementsand behaviouralcorrelates.

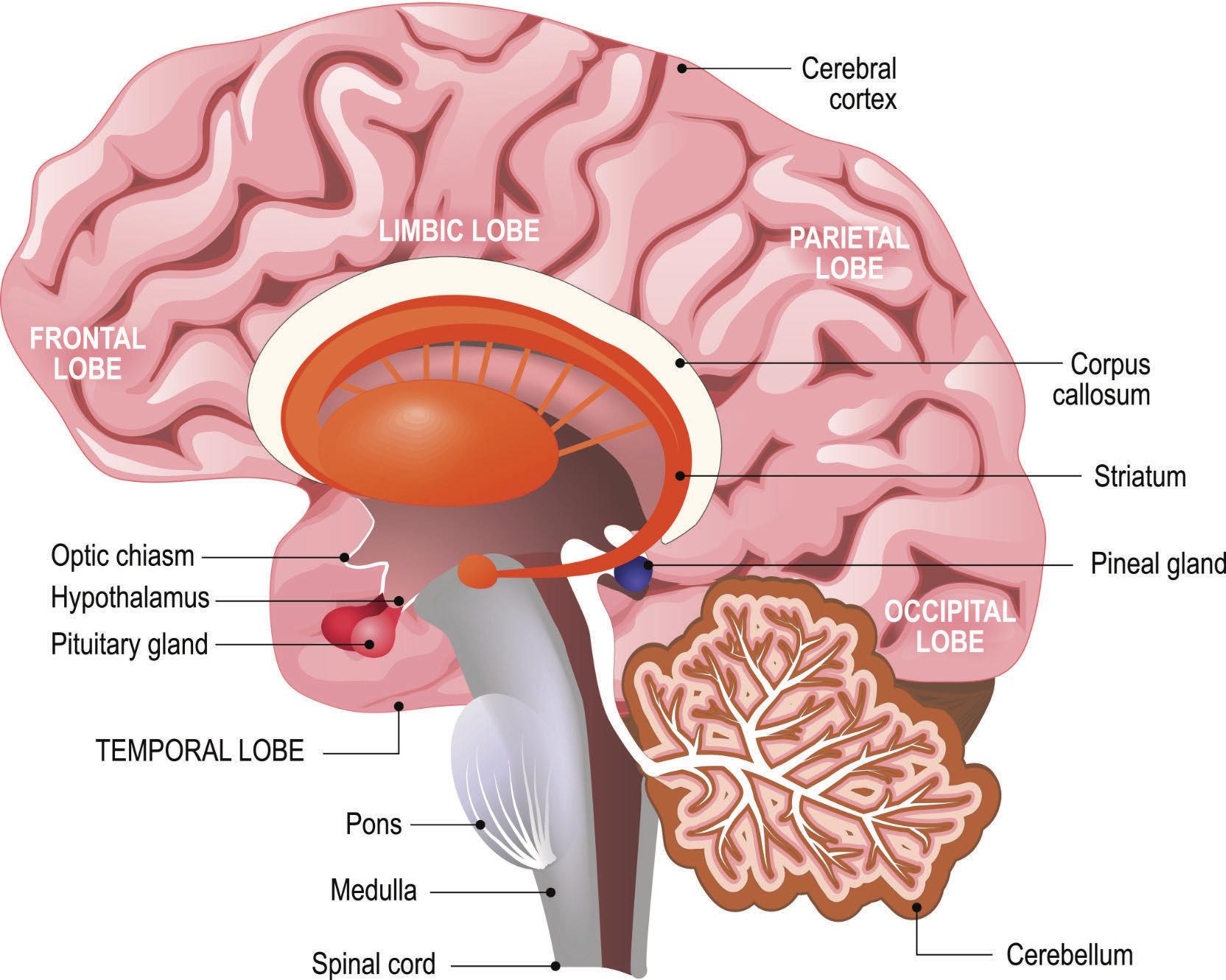

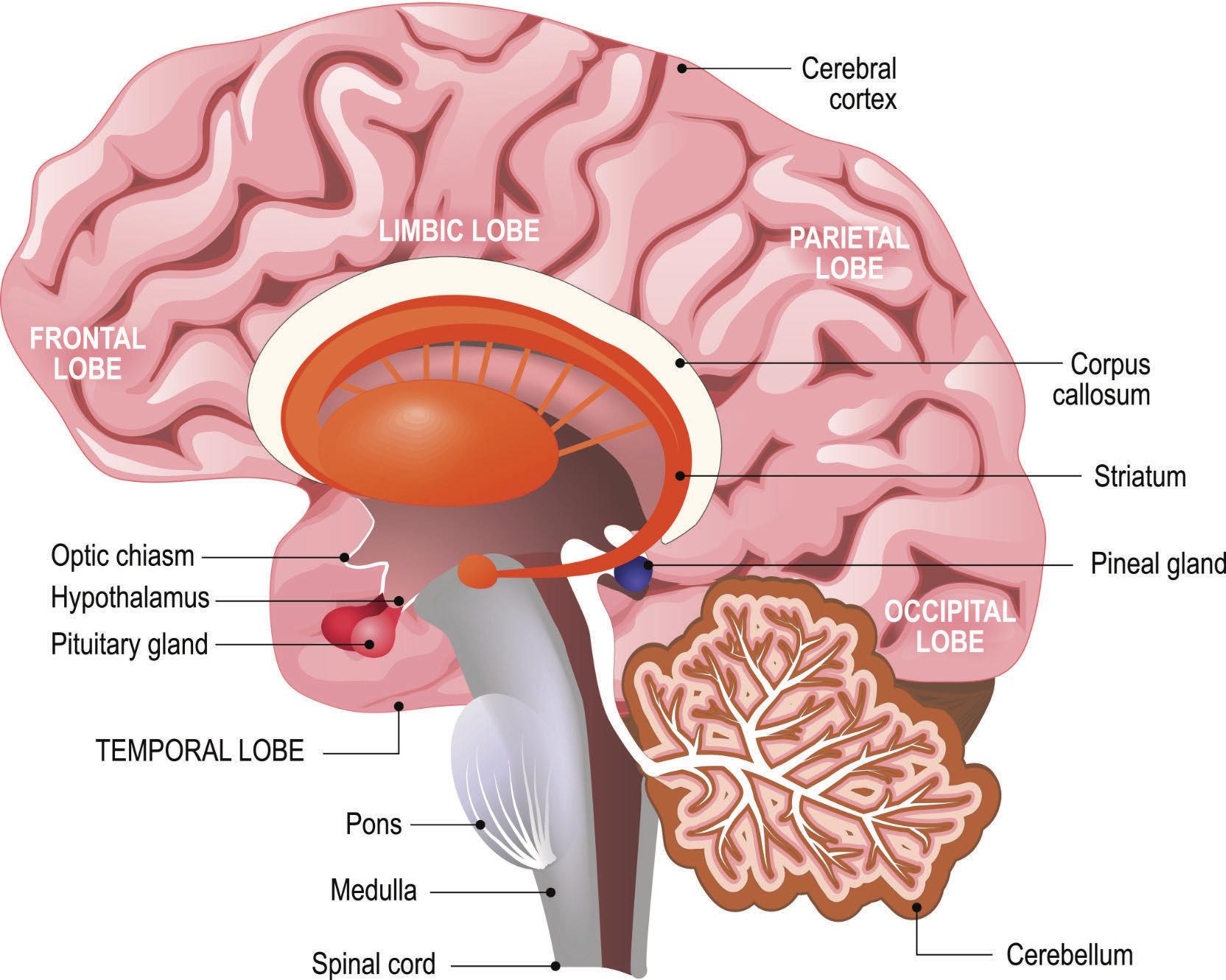

1.2.2Large-scalebrainanatomy

Thenervoussystemisdistributedthroughoutthewholebody.Someoftheperipheral nervoussystemincludesensorssuchastouchsensorsorsensorsforauditorysignals. Someofthosesensorsliketheeyesareinthemselvesalreadyhighlysophisticated neuralsystems,andthebrainstemalreadyprocessessensorysignalstoproducefast responsessuchasreflexes.Ofcourse,itisclearthatmorecomplexinformationprocessingcanbeachievedwiththeaddedcomplexityofthecentralnervoussystemthat weusuallycallthebrain(Fig.1.2).Thebrainitselfhasalotofstructureinitself, suchassubcorticalmidbrainareasthatincludestructuresthatwewillmentionlikethe basalgangliaorthethalamus.Evenwithinthecortexwecaneasilydistinguishareas ofthepaleocortexandarchicortex,whichincludestructuresliketheamygdala,the secondaryolfactorycortex,andthehippocampalformation.Thesecorticalstructures havemostlythreeorfourlayersofcortexcomparedtothesixlayersoftheneocortex thatcoversetheoutsideofthemammalianbrain.Asthenameindicates,theneocortex seemsphylogeneticallynewerthanthearchicortexandthepaleocortex,meaningthat theneocorrtexdevelopedlaterduringevolution.

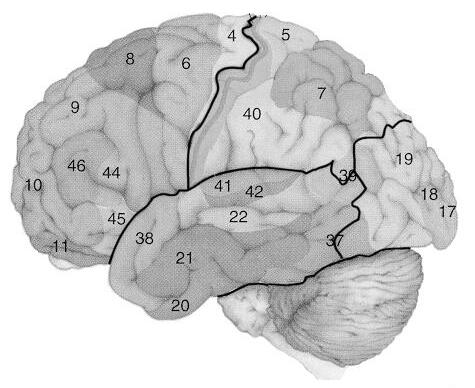

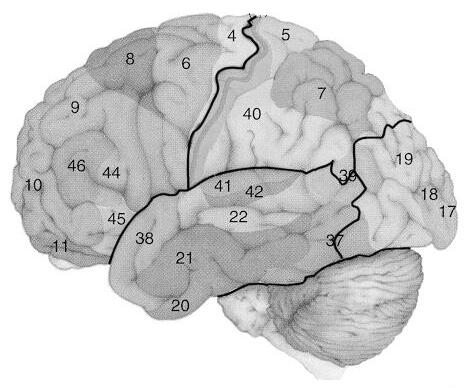

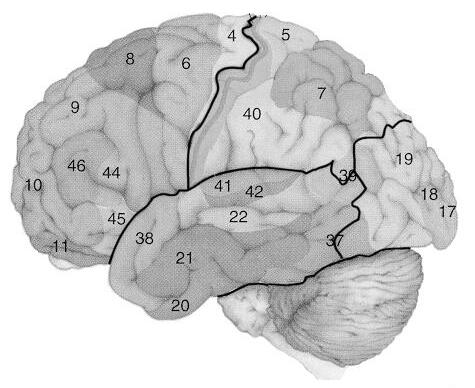

Whiletheneocortexlooksmorehomogeneous,regionsoftheneocortexarecommonlydividedintofourlobesasillustratedinFig.1.2B,theoccipitallobeattherearof thehead,theadjacentparietallobe,thefrontallobe,andthetemporallobesattheflanks ofthebrain.Furthersubdivisionscanbemade,basedonvariouscriteria.Forexample, atthebeginningofthetwentiethcenturytheGermananatomistKorbinianBrodmann identified52corticalareasbasedontheircytoarchitecture,thedistinctiveoccurrence ofcelltypesandarrangements,whichcanbevisualizedwithvariousstainingtechniques.Brodmannlabelledtheareashefoundwithnumbers,asshowninFig.1.2B. Someofthesesubdivisionshavesincebeenrefined,andlettersfollowingthenumber arecommonlyusedtofurtherspecifysomepartofanareadefinedbyBrodmann. Brodmann’scorticalmapis,however,nottheonlyreferencetocorticalareasusedin neuroscience.Othersubdivisionsandlabelsofcorticalareasarebased,forexample, onfunctionalcorrelatesofbrainareas.Theseincludebehaviouralcorrelatesofcortical areasasrevealedbybrainlesionsorfunctionalbrainimaging,aswellasneuronal responsecharacteristicsidentifiedbyelectrophysiologicalrecordings.

Fig.1.2 Outlineofthelateralviewofthehumanbrainincludingtheneocortex,cerebellum,and brainstem.Theneocortexisdividedintofourlobes.ThenumberscorrespondtoBrodmann’s classificationofcorticalareas.Directionsarecommonlystatedasindicatedin1.2B.

Itis,ofcourse,ofmajorinteresttoestablishfunctionalcorrelatesofdifferentcorticalareas,achallengethatdrivesmanyphysiologicalstudies.Wemightspeculatethat thediversefunctionalspecializationwithintheneocortexfoundwithelectrophysiologicalmeasurementsisreflectedinmajorstructuraldifferencesamongthedifferent corticalareastosupportspecializedmentalfunctions.Itisthereforeremarkableto realizethatthisisnotthecase.Instead,itisfoundthatdifferentareasoftheneocortex havearemarkablycommonneuronalorganization.Allneocorticalareashaveanatomicallydistinguishablelayersasdiscussedbelow.Thedifferencesinthecytoarchitecture, whichhavebeenusedbyBrodmanntomapthecortex,areoftenonlyminorcompared totheprincipalarchitecturewithintheneocortex,andthesevariationscannotaccount solelyforthedifferentfunctionalitiesassociatedwiththedifferentcorticalareas. Theneocortexisdifferentinthisrespecttoolderpartsofthebrain,suchasthe brainstem,wherestructuraldifferencesaremuchmorepronounced.Thisisreflected inavarietyofmoreeasilydistinguishablenuclei.Wecanoftenattributespecificlowlevelfunctionstoeachnucleusinthebrainstem.Incontrasttothis,itseemsthatthe cortexisaninformation-processingstructurewithmoreuniversalprocessingabilities thatwespeculateenablemoreflexiblementalabilities.Itisthereforemostinteresting toinvestigatetheinformation-processingcapabilitiesofneuronalnetworkswitha neocorticalarchitecture.

1.2.3Hierarchicalorganizationofcortex

Acommonfeatureofneocortexisthatthereareprimarysensoryareasinwhich basicfeaturesofsensorysignalsarerepresented,whileotherareasseemtosupport morecomplexrepresentationsormentaltasks.Letushighlightthiscommonviewof neocortexwiththeexampleofvision.Theprimaryvisualareathatreceivesmayorinput fromtheeyesliesinthecaudalendoftheoccipitallobeandiscalledV1.Information isthentransmittedtoothervisualareasintheoccipitallobebeforesplittingintotwo majorprocessingstreams,thedorsalstreamalongaparietaltofrontalpathway,and theventralstreamalongthetemporallobe.Ithasbeenarguedthatthedorsalstreamis specificallyadaptedtospatialprocessing,whereastheventralstreamiswellequipped forobjectrecognition.Wewillinvestigateamodelofsuchwhat-and-whereprocessing

Temporallobe Brainstem Cerebellum

laterinthebook.Themainpointhereisthatbrainscientiststrytoidentifyfunctional specificareasandconnectionsbetweentheseareas.

Inordertounderstandhowdifferentbrainareasworktogetheritisimportantto establishtheanatomicalandfunctionalconnectivitybetweenbrainareasinmoredetail. Anatomicalconnectionsarenoteasytoestablishasitisextremelydifficulttofollow thepathofstainedaxonsthroughthebraininbrainslices(includingthebranches thatcanoftenhavedifferentpathways).Thisisadauntingtask,thoughithasbeen doneinisolatedcases.Thereareothermethodsofestablishingconnectivitiesinthe brain.Theseincludetheuseofchemicalsubstancesthataretransportedbytheneurons totargetareasorfromtargetareastotheorigin.Functionalconnectivitypatterns,in whichweareparticularlyinterestedwhenstudyinghowbrainareasworktogether,can alsobeestablishedwithsimultaneousstimulationsandrecordingsindifferentbrain areas.Suchexperimentsshowcorrelationsinthefiringpatternsofneuronsindifferent brainareasiftheyarefunctionallyconnected.Also,somelarge-scalefunctionalbrain organizationscanberevealedbybrain-imagingtechniquessuchasfunctionalmagnetic resonanceimaging(fMRI),whichcanhighlighttheareasinvolvedincertainmental tasks.Suchstudiesestablishedclearlythatdifferentbrainareasdonotworkinisolation. Onthecontrary,manyspecializedbrainareashavetoworktogethertosolvecomplex mentaltasks.

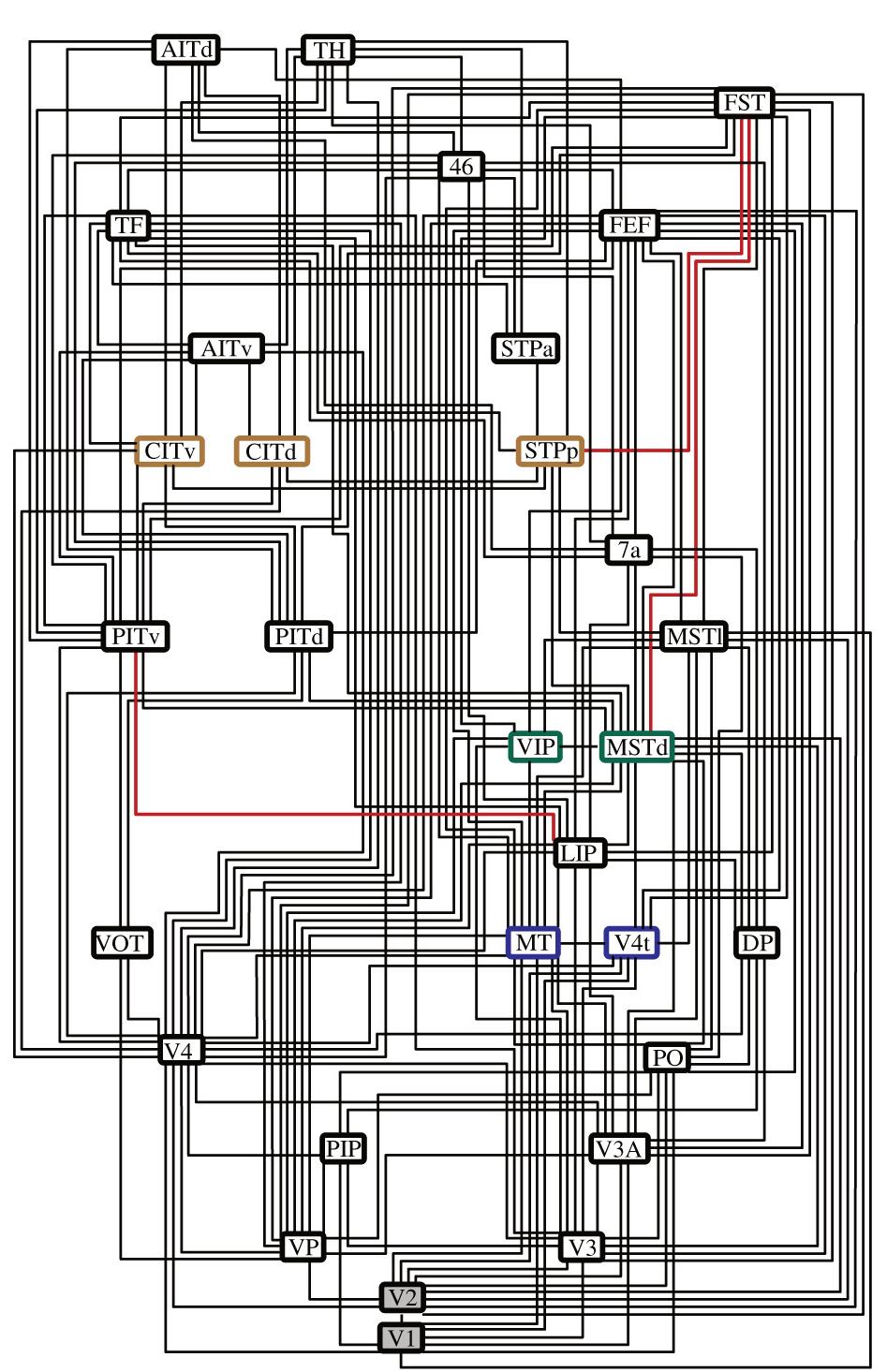

Somescientists,suchasVanEssenandcolleagues,havelongtriedtocompile experimentaldataintoconnectivitymapssimilartotheoneshowninFig.1.3.The specificexamplewasproducedbyClausC.Hilgetag,MarkA.O’Neill,andMalcolmP.Young.Theresearchersusedaneuroinformaticsapproach.Neuroinformatics isspecificallyconcernedwiththecollectionandrepresentationofexperimentaldata inlargedatabasestowhichmoderndataminingmethodscanbeapplied.Hilgetagand colleaguesconsideredanalgorithmthatwouldevaluatemanypossibleconfigurations, andtheyfoundalargesetofpossibleconnectivitypatternsinthevisualcortexsatisfyingmostoftheexperimentalconstraints.EachboxinFig.1.3representsacorticalarea thathasbeendistinguishedfromotherareasondifferentgrounds,typicallyanatomical andfunctional.Thesolidpathwaysbetweentheseboxesrepresentknownanatomical orfunctionalconnections.Theorderfrombottomtothetopindicatesroughlythehierarchicalorderinwhichthesebrainareasarecontactedintheinformation-processing stream,fromprimaryvisualareasestablishingsomebasicrepresentationsinthebrain tohighercorticalareasthatareinvolvedinobjectrecognitionandtheplanningand executionofmotoractions.Theauthorsalsotookthetwobasicvisualprocessingpathwaysintheirrepresentationintoaccount,plottingbrainareasofthedorsalstreamon theleftsideandtheventralstreamontherightside.Notethattherearealsointeractions withinthesepathways.

Interestingly,mostsolutionsofthenumericaloptimizationproblemhavedisplayed someconsistenthierarchicalstructures.Allsolutionsfoundviolatedsomeoftheexperimentalconstraints(dashedlineinFig.1.3),whichisprobablybasedontheinaccuracy ofsomeoftheexperimentalresults.Also,theconnectionsindicatedarenotunidirectional.Itiswellestablishedthatabrainareathatsendsanaxontoanotherbrainarea alsoreceivesback-projectionsfromthestructuresitsendsto.Suchback-projections areofteninthesameorderofmagnitudeastheforwardprojections.Interestingexamples,notincludedinFig.1.3,areso-calledcorticothalamicloops.Thesubcortical

Fig.1.3 Exampleofamapofconnectivitybetweencorticalareasinvolvedinvisualprocessing [reprintedwithpermissionfromC.Hilgetag,M.O’Neill,andM.Young, PhilosophicalTransactionsoftheRoyalSocietyofLondonB 355:71–89(2000)].

structurecalledthethalamuswasinitiallyviewedasthemajorrelaystationthrough whichsensoryinformationprojectstothecortex.However,itisbecomingincreasinglyclearthatthenotionofapurerelaystationistoosimpleastherearegenerally manymoreback-projectionsfromthecortextothethalamuscomparedtotheforwardprojectionsbetweenthethalamusandthecortex.Someestimatesevenindicatea numberofback-projectionsthatexceedtheforwardprojectionstenfold.Thespecific functionalconsequencesofback-projectionsbetweenthethalamusandthecortexas wellaswithinthecortexitselfarestillnotwellunderstood.However,suchstructural featuresareconsistentwithreportsoftheinfluenceofhighercorticalareasoncell activitiesinprimarysensoryareas,forexample,attentionaleffectsinV1.

Inthelastdecadetherehavebeenincreasinglyelaborateattemptstoproducea moredetailedwiringdiagramofthebrain,assocalledconnectome.Oneofthefirst fullmappingofallneuronsandconnectionhasbeendoneforaroundwormcalled Caenorhabditiselegans.Thisanimalhadthereforebecomeoneofthebest-studied

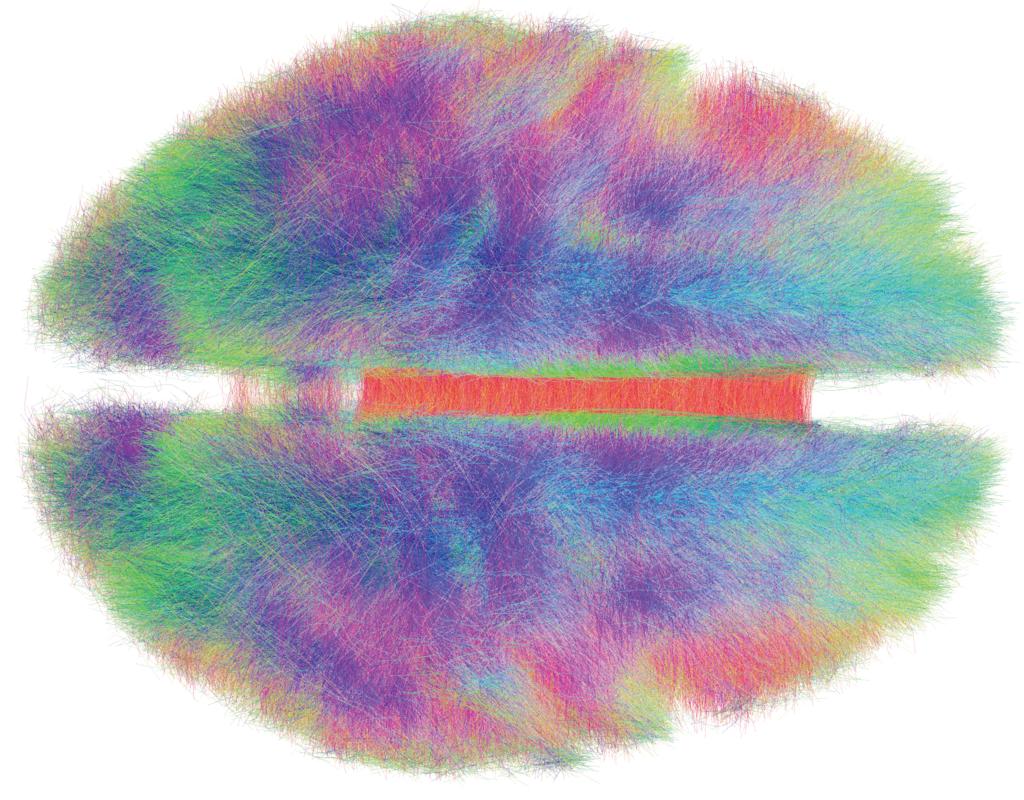

modelsystemsinneuroscience.TheEuropeanBlueBrainProjectattemptstomapthe mousebrain,andtherearealsoattemptstomapthehumanbrain.Avisualizationof whitematterconnectionsfrom20subjectsisshowninFig.1.4

Fig.1.4 Exampleofagroup-levelconnectomeofhumanwhitematter.[A.Horn,D.Ostwald,M. Reisert,F.Blankenburg(November2014).‘Thestructural-functionalconnectomeandthe defaultmodenetworkofthehumanbrain’. NeuroImage 102(1):142-{51].

1.2.4Rapiddatatransmissioninthebrain

Fromthesystemlevelviewofthebrainitseemsthattherearemanystagesofprocessing inthebrainsothatachievingevenbasictaskslikeobjectrecognitioncouldtakea considerabletime.Angoodillustrationofhowquicklyinformationcanbetransmitted throughthebrainisprovidedbytheresearchofSimonThorpeandcolleagues.They showedthathumansubjectsareabletodiscriminatethepresenceorabsenceofspecific objectcategories,suchasanimalsorcars,invisualscenesthatarepresentedforvery shorttimes,asshortas20ms.Thepercentageofcorrectmanualresponses,which consistedofreleasingabuttononlywhenananimalwaspresentinacompleximage thatwaspresentedfor20ms,isshownfor15subjectsinFig.1.5Aplottedagainstthe meanreactiontimeforeachsubject.Theexperimentshowssometrade-offbetween reactiontimeandrecognitionaccuracy,buttheimportantpointtonotehereisthehigh levelofperformanceforsuchshortpresentationsoftheimages.

Theabilitytorecognizeobjectswiththeseshortpresentationtimesisnottheonly astonishingresultintheseexperiments.TheauthorsalsorecordedskullEEGsduring theexperiments.Theevent-relatedpotential,averagedoverfrontalelectrodes,isshown inFig.1.5B,separatedforimagepresentationswithandwithoutanimals.Theaverage responseisnotdifferentforthefirst150ms,butbecomesmarkedlydifferentthereafter. Theresponseofthefrontalcortexthereforealreadyindicatesacorrectanswerafter 150ms.Thisisremarkablebecauseforsuchcategorizationtasksweknowthatneural activityhastopassthroughseverallayersofbrainareas.Eachneuronintheprocessing streamnecessaryforthecategorizationpathmustthusbeabletoprocessandpasson informationintimeintervalsoftheorderofonly10–20msorso.

Fig.1.5 (A)Recognitionperformanceof15subjectswhohadtoidentifythepresenceofananimal inavisualscene(presentedforonly20ms)versustheirmeanreactiontime.(B)Event-related potentialaveragedoverfrontalelectrodesacrossthe15subjects[redrawnfromThorpe,Fize,and Marlow, Nature 381:520–2(1996)].

1.2.5Thelayeredstructureofneocortex

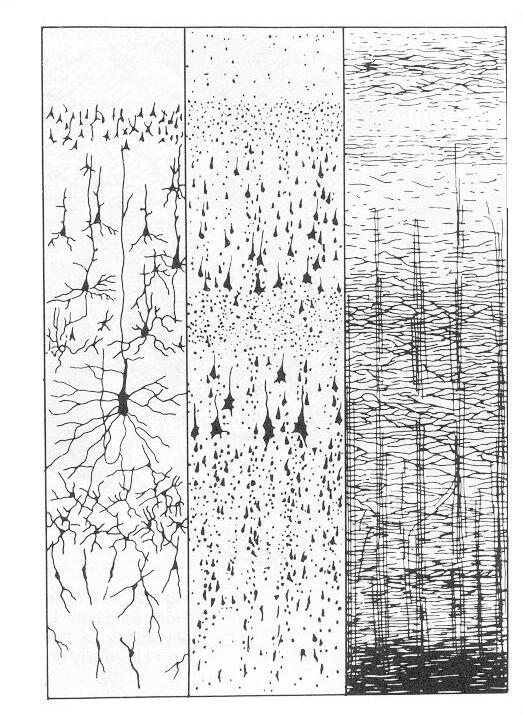

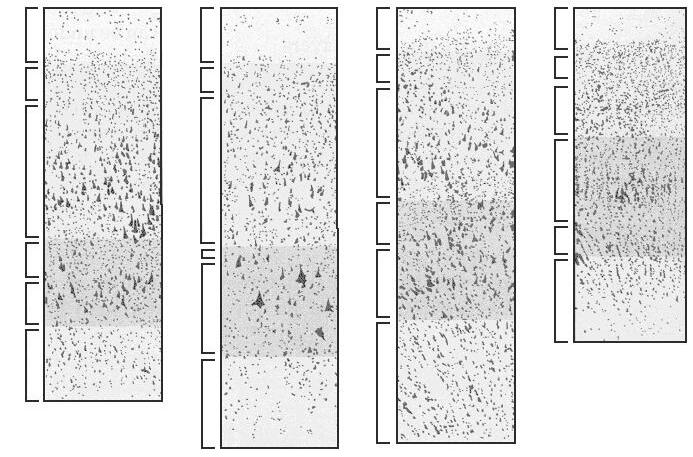

Stainingofcellbodiesorneuritesrevealsagenerallylayeredstructureoftheneocortex, asillustratedinFig.1.6.Weincludeheresomebriefcommentsonexperimental stainingtechniquestoclarifyassumptionsandlimitationsofsuchtechniques,since thesetechniquesareoftencrucialforestimatingparametersonwhichmodelsare based.Manydifferentstainingtechniquescanbeusedtoidentifyneuronsorparts thereof.Somestainingtechniques,suchastheNisslstain,colouronlythecellbody andcannotbeusedtoinvestigatedendriticoraxonalorganizations.TheGolgistain, basedonasilversolution,canbeusedtovisualizemorepartsoftheneuronthanthose accessiblebyNisslstaining.Whenviewingillustrationsofsuchstainedtissuesitis importanttoknowthatonlyasmallpercentageofneurons,ontheorderofonly1–2%, arestainedbytheGolgistainingmethod,anddifferentneuronscanhavedifferent receptivitiestothisstain.Theappearanceofneocorticalslicesvisualizedbydifferent stainingtechniquesisillustratedinFig.1.6A.

Inadditiontothesetraditionaldyesthereisnowavarietyofotherstainingtechniquesincludingdirectintracellulardyeinjectionsreachingmostpartsofaneuron, anterogradestainingthatutilizesdyesthataretakenupbythecellbodyandtransporteddowntheaxons,andretrogradestainingthatutilizesdyesthataretakenupby theterminalendingsofaxonsandtransportedbacktothecellbody.Theformertwo stainingtechniquescanbeusedtoidentifytheprojectionrangeofneurons,andthelatterisusefultohighlighttheneuronsthatprojectintoaparticularbrainarea.Mastering suchtechniquesandapplyingthemcarefullytogetestimatesofneuronalpopulations anddendriticoraxonalorganizationsisaspecializationwithinneuroscienceonwhich computationalneuroscientistsrelyheavilyinordertodevelopbiologicallyfaithful models.

Historically,theneocortexisdividedintosixlayerslabelledwithRomannumerals fromItoVI,althoughmorethansixlayers,commonly10includingthewhitematter, canbeidentifiedandareincludedintothehistoricallabellingschemebyfurther subdivisions.LayerIVistherebysubdividedintoIVA,IVB,andIVC,andlayerIVC isfurthersubdividedintolayersIVCα andIVCβ.Theextent,orthickness,ofthe layersvariesthroughouttheneocortexuptoapointwheresomelayersaredifficult toidentifyifnotabsent.Examplesofstainedslicesfromdifferentareaswithinthe

Different staining techniques

Golgi Nissl Weigert

Variation in cortex

Fig.1.6 Examplesofstainedneocorticalslicesshowingthelayeredstructureoftheneocortex. (A)Illustrationofdifferentstainingtechniques[adaptedfromHeimer, Thehumanbrainandthe spinalcord,Springer,2ndedition(1995)].(B)Differentsizesofcorticallayersindifferentareas [adaptedfromKandel,Schwartz,andJessell, Principlesofneuralscience,McGraw-Hill,4th edition(2000)].

neocortexareshowninFig.1.6B.Thevisualappearanceinthestainedslicesdefining thelayersisdependentondifferentpopulationsofcellbodiesandneurites.LayerI iseasilydistinguishableasitismainlylackingincellbodiesandconsistsmainlyof neurites.Theotherlayersaremarkedbythedominationofdifferentcelltypes. Thesomaofseveralneuronaltypescanbefoundineachneocorticallayer,although thedistributioncanbeusedtomarkthelayerstosomeextent.Asmentionedabove, layerIisnearlycompletelylackingincellbodiesandconsistsmainlyofneurites. Pyramidalcellscanbefoundinmostotherlayersoftheneocortex.LayersIIandIII consistpredominantlyofsmallpyramidalcells,althoughthecellsinlayerIIItend tobelargerthanthoseinlayerII.Stellateneuronsseem,inparticular,concentrated aroundlayerIV.Intheupperpartofthislayer(IVAandIVB)onecanfindamixture ofmedium-sizedpyramidalcellsandstellatecells,whereasthedeeperlayer(layer IVC)seemstobedominatedbystellateneurons.Largepyramidalcellsarefound predominantlyinlayerV.Avarietyofcelltypescanbefoundinthedeepestlayer, layerVI.ThisincludesMartinotticellsandalsocellsthathaveelongatedcellbodies andaresometimesusedtomarkthislayer.Suchcellsaresometimescalledfusiform neurons.

1.2.6Columnarorganizationandcorticalmodules

Theneuronalorganizationintheneocortexdiscussedsofarismainlybasedonanatomicalevidence.Thereis,inaddition,animportantfunctionalorganizationintheneocor-

texrevealedbyelectrophysiologicalrecordings.Theseexperimentshaveshownthat neuronsinasmallareaofthecortexrespondtosimilarfeaturesofaninputstimulus. HubelandWieselhaveinvestigatedsuchorganizationintheprimaryvisual(orstriate)cortex.Neuronsinthiscorticalarearespondtovisualbarsmovinginparticular directions.Moreprecisely,neuronsinasmallcorticalcolumnperpendiculartothe layersandseparatedbyaround30–100 µmrespondtomovingbarswithaspecific retinalpositionandorientation.Theseregionsarecalledorientationcolumns.Separatefromthesearrangementsareoculardominancecolumns,corticalsectionsthat respondpreferentiallytoinputfromaparticulareye(seeFig.1.7A).Therelationsof orientationcolumnsandoculardominancecolumnsareillustratedschematicallyin Fig.1.7B.Neuronsinsmallcolumnsinotherpartsofthecortexalsotendtorespond tosimilarstimulusfeatures.Forexample,corticalcolumnsinthesomatosensorycortexeachrespondtospecificsensorymodalitiessuchastouch,temperature,orpain. Thedistributionofneuronswithspecificresponsecharacteristicsishencenotpurely randominthecortex,butthereseemstobesomeformoforganization.

Fig.1.7 Columnarorganizationandtopographicmapsintheneocortex.(A)Oculardominance columnsasrevealedbyfMRIstudies[fromK.Cheng,R.A.Waggoner,andK.Tanaka, Human oculardominancecolumnsasrevealedbyhigh-fieldfunctionalmagneticresonance imaging, Neuron 32:359–74,(2001)].(B)Schematicillustrationoftherelationbetweenorientationandoculardominancecolumns.(C)Topographicrepresentationofthevisualfieldinthe primaryvisualcortex.(D)Topographicrepresentationoftouch-sensitiveareasofthebodyinthe somatosensorycortex.[(C)and(D)adaptedfromKandel,Schwartz,andJessell, Principlesof neuralscience,McGraw-Hill,4thedition(2000).]

A. Ocular dominance columns

B. Relation between ocular dominance and orientation columns

C. Topographic map of the visual field in primary visual cortex

D. Somatosensory map

HubelandWieselcalledacollectionoforientationcolumnsrepresentingacompletesetoforientationsahypercolumn.Theyshowedthatadjacenthypercolumnsin thestriatecortexrespondtovisualinputfromadjacentretinalareasasillustratedin Fig.1.7C.Centralregionsofthevisualfieldarerepresentedbyalargercorticalarea thanperipheralareas.Themappingbetweenthevisualfieldandthecorticalrepresentationisthereforenotarea-preserving;thecentralvisualareaisover-represented,a featurethatiscalledcorticalmagnification.However,themappreservestherelationshipsbetweenadjacentpointsbutnotthearea.Suchmapsarecommonlylabelledas topographicintherelatedliterature.Wewillusethisterminageneralsense,meaning anymapofafeaturespacewithsomesystematicrelationsbetweenpoints(features) onthemap.Forexample,atonotopicmap,whichisamapofsoundrepresentations, istopographicwhenadjacentfrequenciesarerepresentedatadjacentlocationsinthe map.Ahypercolumnitselfisatopographicmapasitcontainsanorderedrepresentationoforientation,andtherearemanymoreexamplesofsuchmapsincortexandin subcorticalareas.OneotherexampleisillustratedinFig.1.7D,thatofthesomatosensorycortexwhichrepresentstactileinputfromdifferentbodyparts.Thiscorticalarea representsagainmoresensitiveareaswithlargercorticalareas.Chapter8explores mechanismsthatcanexplainhowsuchcorticalorganizationcanbeformedthough experience.

Itisconceptuallyimportantthatneuronsinasmallareasofthecortexrespondto similarsensorystimuliaswecanusethistosimplifymodelsofcorticalorganization andfunctions.Formanymodelsinthisbookitisthereforesufficienttorepresentthe neuronsinacertainareaasasingleunit,asdiscussedfurtherinChapter5.Withsuch populationneuronsitisthenmucheasiertoexplorevariousbrainmechanisms,such astheformationoftopographicorganizationsorthetransformationofrepresentations.

1.2.7Connectivitybetweenneocorticallayers

Theconnectivitypatternwithinthelayeredstructureofneocortexisbecomingincreasinglyimportantforcomputationalmodels.NeuronsinlayerIVseemtoreceive aparticularlylargenumberofafferentsthroughthewhitematterfromsubcorticaland othercorticalareas.Thislayeristhereforeoftenviewedasaninputlayer.LayerVhas manylargepyramidalcellswithaxonsextendingintothewhitematter.Thislayerseems thereforetocontributelargelytotheoutputofcorticalprocessing.Asthewhitematter isthemainpathwaybetweenremotecorticalareasand,inparticular,betweencortical andsubcorticalareas,itisobvioustosuggestthattheinformationflowingthrough thewhitematteris,toalargeextent,responsibleforglobalinformationtransmission inthebrain.Incontrast,pyramidalcellsinlayersIIandIIIarethoughttobelargely responsibleforlong-rangecortico-corticaltangential(lateral)connections.Martinotti cellsinthedeeplayersoftheneocortexhaveaxonsextendingintolayerI.Thesecould beresponsibleforinformationtransferbetweenadjacentcorticalmodulesfromwhich pyramidalneuronsintheupperlayersreceivesynapticinput.Stellateneurons,onthe otherhand,seemtobemorelocalintheirneuriticsphere.Thesmoothstellatecells arethereforecandidatesforinhibitoryinterneurons.Theirroleinthestabilizationof corticalprocessingisanimportantissuethatwewilldiscussinlatersectionsofthis book.

Anoutlineofconnectivitypatternswithinasmallcolumnoftheneocortexis