EvolutionandDevelopment

ConceptualIssues

ElementsinthePhilosophyofBiology

DOI:10.1017/9781108616751

Firstpublishedonline:February2024

AlanC.Love

UniversityofMinnesota

Authorforcorrespondence: AlanC.Love, aclove@umn.edu

Abstract: Theintersectionofdevelopmentandevolutionhasalways harboredconceptualissues,butmanyoftheseareondisplayin contemporaryevolutionarydevelopmentalbiology(evo-devo).These issuesinclude:(1)thepreciseconstitutionofevo-devo,withitsfocuson boththeevolutionofdevelopmentandthedevelopmentalbasisof evolution,andhowit fitswithinevolutionarytheory;(2)thenatureof evo-devomodelsystemsthatcomprisethematerialofcomparative andexperimentalresearch;(3)thepuzzleofhowtounderstandthe widelyusednotionof “conservedmechanisms”;(4)thedefinitionof evolutionarynoveltiesandexpectationsforhowtoexplainthem;and (5)thedemandofinterdisciplinarycollaborationthatderivesfrom investigatingcomplexphenomenaatkeymomentsinthehistoryoflife, suchasthe fin–limbtransition.ThisElementtreatstheseconceptual issueswithcloseattentiontobothempiricaldetailandscientific practicetooffernewperspectivesonevolutionanddevelopment.This ElementisalsoavailableasOpenAccessonCambridgeCore.

Keywords: evo-devo,homology,interdisciplinarity,models,novelty

©AlanC.Love2024

ISBNs:9781009468022(HB),9781108727525(PB),9781108616751(OC)

ISSNs:2515-1126(online),2515-1118(print)

1.1SomeHistoricalPerspective

WhenastudentlearnsabouttheAmericanRevolutionoftheeighteenth centuryinsecondaryeducation,theyoftenencountermomentsthatencapsulatethebeginning,end,orclimaxofthiscomplexhistoricalevent. Famousamongtheseis “ theshotheardroundtheworld, ” whichpicksout the1775battleofConcord(Massach usetts)asthetouchstoneofopen hostilitiesbetweenBritishsoldiersandcolonialiststhatmarkstheformal startoftheAmericanWarofIndependence.Therewerecertainly “ fi rsts ” thatday,including fi rstshots fi redbycolonialminutemenbecauseofexplicitordersandthe fi rstBritishfatalities.Andthephraseismemorable, derivingfromRalphWaldoEmerson ’s “ ConcordHymn ” writtensixty-two yearslaterwhentheinternationalsigni fi canceoftheAmericanRevolution wasmorerecognizable.However,anyhistorianworkingonthisperiodwill tellyouthatthevarietyofeventsovermanyyearsleadinguptothisbattle, thebattleitself,andsubsequenteventsyieldamoretangledtale.The secondarystudentwillnodoubtbeaidedbyEmerson ’ssloganinpreparing foranexam,butadeeperunderstandingoftheinitiationoftheAmerican Revolutionanditscomplicatedarchitecturerequiresmore(McDonnell2016).

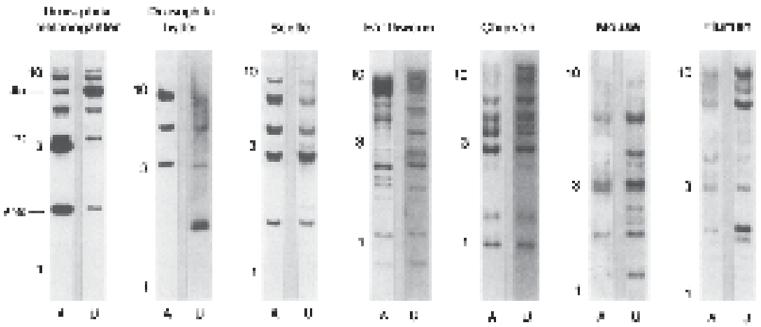

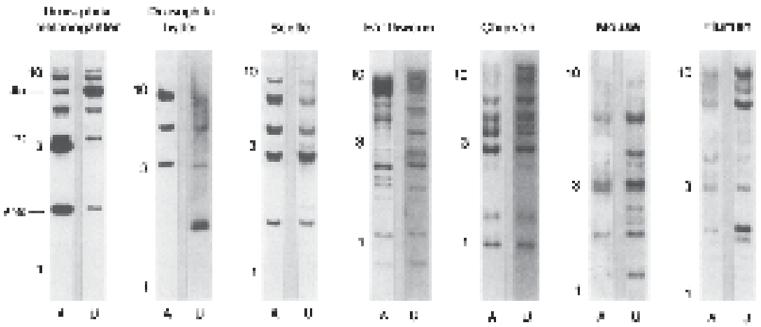

Referencestotheoriginofevolutionarydevelopmentalbiology(evo-devo) haveamemorablemomentthatencapsulatesitscontemporarybeginningsfor manybiologists.Thisisthediscoveryoftheevolutionaryconservationof~180 basepairsofnucleotidesequence(the “homeobox”)responsibleforthe~60 aminoacid “homeodomain” regionofDNA-bindingproteins – transcription factors – thatregulateavarietyofcriticalgeneactivityduringdevelopment (McGinnisetal.1984; ScottandWeiner1984).Thediscoveryofhomeobox geneconservationacrossmetazoans(multicellularanimals)wasdepictedvividlyinseveralSouthernblotsofgenomicDNAfromdiversespecies(Figure1). (TheSouthernblotisamolecularbiologytechniqueusedtodetectthepresence ofspecificDNAsequencefragmentsbyhybridizingalabeledprobethat containsacomplementaryDNAsequence.)Itisdifficult,inretrospect,to appreciatehowsurprisingthis findingwastobiologists.Whatisnow acommonplaceduetosubsequentempiricalinvestigation –“surprisingly deepsimilaritiesinthemechanismsunderlyingdevelopmentalprocessesacross awiderangeofbilaterallysymmetricmetazoans ... acommoncoreofgenetic pathwaysguidingdevelopment” (BierandMcGinnis2003,25) – wasjustglimpsed atthetime: “someelementsofpatternformationinmetazoans ... wouldseemtobe mechanisticallyrelatedinaverybasicway,raisingthepossibilityofuniversal controlmechanismsofdevelopment” (McGinnisetal.1984,407).

Figure1 ConservationofthehomeoboxDNAsequenceacrossmetazoans.There areduplicategenomicblotsforeachspecieswithtwodifferentprobescontaining the~180basepair(bp)homeoboxsequence: A =600bpfragmentfromthe Antennapedia homeoboxgeneof Drosophilamelanogaster (thefruit fly); U =450 bpfragmentfromthe Ultrabithorax homeoboxgeneof Drosophilamelanogaster. RadiolabeledhybridizationfragmentsindicateacomplementaryDNAsequence andthereforethepresenceofthehomeoboxsequenceinotherspecies.Ten,three, andonekilobaselabelsaremigrationdistancesizestandards.Abbreviations:Ubx: Ultrabithorax;ftz: fushitarazu;Antp: Antennapedia. Adaptedfrom: McGinnisetal.(1984).ReproducedwithpermissionfromElsevier.

Formanybiologists,thismemorableeventisrecalledasafountainhead: “present-dayevo-devoeruptedoutofthediscoveryofthehomeoboxinthe early1980s” (Arthur2002,757). “Evo-devobeganinthepre-genomicerawhen geneticstudies revealedthatthe Hox genesthatcontroltheanterior-posterior (A-P)axiswereunexpectedlyconserved” (DeRobertis2008,186).Thefuture, asaconsequence,wasbright: “Weareataremarkablepointinourunderstandingofnature,forasynthesisofdevelopmentalgeneticswithevolutionary biologymaytransformourappreciationofthemechanismsunderlyingevolutionarychangeandanimaldiversity” (Gilbert1997,914).Onanalogywiththe AmericanRevolution,wemightcallthevisualevidenceofhomeoboxconservationin Figure1 “theblotseenroundtheworld” (withapologiestoEmerson). Yetamoreaccurateunderstandingoftheemergenceandsignificanceofevodevoinallitscomplexityturnsouttobemorecomplicated(Love2007b, 2015a; Moczeketal.2015).Andthis,inturn,isrelevantforhowwethinkabout conceptualissueslikethestructureofevolutionarytheory(see Section1.3).

In1978,yearsbeforethediscoveryofhomeoboxconservation,apromising graduatestudentwrotealettertohisadvisordescribinghisrecentintellectual interactionswithotherbiologistsataconference.

TheGordonConferenceonTheoreticalBiologywasveryinterestingsince Ihadtheopportunitytomeetalotofpeopleina fieldthatisnewforme.The mostimportanteventwastomeetLewisWolpert.Hewasveryinterestedin ourpaperandwehadalongdiscussionabouttheroleofdevelopmentin evolution.Healsobelievesthat “thenextmajorbreakthroughinbiologywill involvetheintegrationofdevelopmentinevolutionarytheory.” (Pere AlberchtoDavidWake,July8,1978;courtesyofDavidWake)

Alberch’sconversationwithWolpertbecametheimpetusforaworkshopon evolutionanddevelopmentheldin1981withparticipantsdrawnfromavariety ofdisciplinaryapproaches(e.g.,mathematicalbiology,paleontology,morphology,molecularbiology,evolutionarygenetics,developmentalgenetics,and experimentalembryology)andtaxonomicspecialties(lowereukaryotes,marineinvertebrates,terrestrialarthropods,andvertebrates).ItincludedStephen JayGouldwhosehistoricaltreatmentoftherelationshipbetweenontogenyand phylogenycontributedtothemotivationbehindtheworkshop(Gould1977). Theresultingeditedvolume(Bonner1982)wascatalyticforevo-devoandwas quicklyjoinedbyachorusofotherbooks(e.g., Arthur1984; Goodwinetal. 1983; RaffandKaufman1983).

Thegoalofthis “Dahlemworkshop” onevolutionanddevelopmentwas “to examinehowchangesinthecourseofdevelopmentcanalterthecourseof evolutionandtoexaminehowevolutionaryprocessesmolddevelopment.” This remainsanaptstatementofthetwomainaxeswithincontemporaryevo-devo: (1) theevolutionofdevelopment,orinquiryintothepatternsandprocessesof howontogeny(development)variesandchangesovertime;(2)the developmentalbasisofevolution,orinquiryintothecausalimpactofontogenetic processesonevolutionarytrajectories,bothintermsofconstraintandfacilitation(Love2015b).However,thisdescriptionleavesobscurethemajorroleof phylogeneticreconstructionthathadnotyetmaturedatthetimeoftheDahlem workshop(Love2015a).Boththecladisticrevolutioninsystematicsandthe increasinguseofmoleculardatatobuildphylogenetictreesledtoadramatic reconceptualizationofthemetazoantreeoflife(Adoutteetal.2000 ).This beganwiththeuseofribosomalRNAtoreconstructrelationshipsamongten differentphyla(Fieldetal.1988 )andfosteredtheresolutionofnewmajor clades,suchastheLophotrochozoaor “ crest/wheel” animals(Halanychetal. 1995)andEcdysozoaormoltinganimals(Aguinaldoetal.1997).Additional refinementscontinue,butthebroadoutlineisnowconsensus(Figure2;see GiribetandEdgecombe2020).Phylogenyandcladisticsarerecognizedascentral toresearchmethodologyinevo-devo(Jenner2000; TelfordandBudd2003).

Combiningthehistoricalsignificanceofbothevolutionaryconservationin geneticmechanismsthatcontroldevelopmentandmolecularphylogenetic

Figure2 Aphylogenetictreerepresentingrelationshipsamongmetazoanclades. Thereconstructionwasdoneusingmaximumlikelihoodmethods.Redrawn.

Source: Schierwateretal.(2009) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Metazoan_ Phylogenetic_Tree.png.

reconstructionclarifieshowcrucialelementsofcontemporaryevo-devo emerged.However,thesetendtopaintapredominantly “genetic” portrait (Wilkins2002).Thisishowsomebiologistsinterpretedthesituation. “Three mainfactorshavecontributedtotheemergenceandphenomenalgrowthof

evolutionarydevelopmentalbiology.Ironically,allthreedependongenetics” (Holland1999,C41).Thesethreefactorsareconservedregulatorygenesthat playsimilarfunctionalrolesinontogenyacrosswidelydivergenttaxa,molecularphylogenetics,andmolecularbiologicaladvancesintechniquethatfacilitate thesophisticatedanalysisandmanipulationofgeneticmaterial.The firstof theseyieldedtheinfluentialconceptofa “conservedmechanism” (Section3) thathelpedunderwritetheincreasinglycommonuseofmodelorganisms (Section2).Arguably,thecentralityofthehomeoboxstoryinhistoricalmemoryowesalottothecentralityofconservedmechanismsandmodelorganisms ineverydayexperimentalresearchfourdecadeslater.

However,keepinginmindtheheterogeneityofresearchersattheDahlem workshop,thisportrait – focusedonmolecularadvancesandgeneticmanipulation –canencourageaneglectoftheinterdisciplinarynatureofevo-devo(Section5), whichwasevidentpriortothesekeydevelopmentsandprovidedtheintellectual contextforthesignificanceofthethreefactors.Forexample,manyofthecontemporarytoolsforexploringtheevolutionofdevelopmentarosefromthelineageof experimentalembryology,mostnotablythosenowubiquitousindevelopmental genetics.Thedominanceofgenetictechniquesincontemporarydevelopmental biologyreinforcestheirimportancetothehistoryofevo-devo(FraserandHarland 2000).Ifweshiftourattentionawayfromthe investigativetoolstotheagendaof problemswithinevo-devo,experimentalembryologyisnottheappropriateintellectualancestor.Thisagenda,whichincludedreconstructingphylogeneticrelationshipsamongmetazoangroupsandaccountingfortheoriginofevolutionary novelties,derivedfromcomparativeevolutionaryembryology(LoveandRaff 2003),aswellasresearchinmorphologyandpaleontology(Love2007b).

Thishistoricalperspectiveshould,ataminimum,alertustobecautiousabout theintendedreferentwhensomeonereferstoevo-devo.Narrowdepictions oftenrevolvearoundthecomparativedevelopmentalgeneticsofmetazoans (Carroll2005a; DeRobertis2008),wherethefocusisonconservedgenetic regulatorynetworks(GRNs)1 andsignalingpathwaysunderlyingdevelopmentalprocesses(commonlyreferredtoas “thegenetictoolkit”).Evolutionary changeisunderstoodintermsofprocessesofgeneregulationwithaspecial emphasison cis-regulatoryelements2 (Carroll2008; Davidson2006; Davidson

1 AGRNisanorganizedcollectionofmolecularentitiesthatinteractwithoneanotherincoordinatedpatterns(e.g.,negativefeedbackrelationships)toregulategeneexpressionduringdevelopmentandthroughoutthelifeofanorganism(DavidsonandPeter2015).

2 A cis-regulatoryelementisaregionofDNAthatdoesnotcodeforaproteinbutregulatesnearby genesthroughtheactivationorrepressionoftheirtranscriptionderivedfromtranscriptionfactors bindingatsitesinthisregion.Theadjective “cis” derivesfromtheLatinprefixmeaning “onthis side” andreferstobeinglocatedonthesamestretchofDNAbeingregulated(see Davidsonand Peter2015).

andPeter2015).Mostofthisempiricalresearchhasbeenprosecutedusing modelorganismsfrommainstreamdevelopmentalbiology,suchasfruit flies, becausetheexperimentaltoolsavailableformanipulatingthesesystemsarethe mostpowerfulanddiverse(see Section2).

Broaddepictionsofevo-devoincludecomparativedevelopmentalgenetics butalsopointtocomparativeembryologyandmorphology,experimental investigationsofepigeneticdynamics(e.g.,interactionsamongcellcollectives),computationalorsimulation-orientedinquiry,paleontology,andphylogeny(Hall2002; Müller2007; Raff2000, 2007; TelfordandBudd2003; Wagneretal.2000).Thesedepictionsaresometimesarticulatedintermsof disciplinarycontributorsormethodologicalapproaches: “[Evo-devo]isnot merelyafusionofthe fieldsofdevelopmentalandevolutionarybiology, ... [it]strivestoforgeaunificationofgenomic,developmental,organismal,population,andnaturalselectionapproachestoevolutionarychange.Itdrawsfrom development,evolution,paleaeontology,molecularandsystematicbiology,but hasitsownsetofquestions,approachesandmethods” (Hall1999,xv).These broaderdepictionshaveastrongresonancewiththemorecomplicatedarchitectureidentifiedfromourbriefrompthroughrecenthistoryandisreinforced byotheranalyses(Amundson2005; LaubichlerandMaienschein2007).3

Answerstothequestionofwhatevo-devoisvary.Andthisisnotsomething artificiallyconcoctedbyhistoriansorphilosopherslookinginonthe fieldfromthe outside. “Whatisevo-devo?Thisisahardquestiontoanswersuccinctly;evo-devo isdevelopmentalgenetics,itismathematicsandmodeling,itisgenomicsand anatomyandpaleontology.Inshort,evo-devoinsightscancomefrommyriadlines ofresearch.Thisissimultaneouslyoneofthemostexcitingattributesofthe field andoneofitsgreatestchallenges” (Albertson2018,191).Fromaphilosophical perspective,differentanswerstothequestioninvolvecommitmentsaboutthe structureofknowledgeandespeciallyhierarchicalrelationsbetweendifferent elements(i.e.,whetheronedomainismorefundamentalthananother).Thus, ourhistorybringsustothepresentbecausethesecommitmentsarewhatisatstake incurrentconversationsaboutevo-devoandcallsforan “extendedevolutionary synthesis” (EES)(Futuyma2017; Lalandetal.2015; Müller2017; Pigliucci2007; PigliucciandMüller2010).Onestrategyforexploringthesecommitmentsisto askarelatedquestion:Withinthebodyofknowledgereferredtoasevolutionary theory,wheredoyouputevo-devo(Fábregas-TejedaandVergara-Silva2018)?

3 Acomprehensivetreatmentofthelandscapeofmodernevo-devothatnicelycoversthediversity describedhereinmuchmoredetail(historical,philosophical,andscientific)canbefoundin EvolutionaryDevelopmentalBiology:AReferenceGuide (NuñodelaRosaandMüller2021). Severalofitschaptersarecitedherein.

1.2SituatingEvo-DevoinEvolutionaryTheory

Theplaceofevo-devowithinevolutionarytheoryiscontested.Somevoices havebeenskeptical: “problemsconcernedwiththeorderlydevelopmentofthe individualareunrelatedtothoseoftheevolutionoforganismsthroughtime” (Wallace1986,149).Othershavebeenoptimistic,seeingevo-devoasproviding aunifiedtheoreticalframeworkintermsofcentralorganizingmechanisms, suchasGRNs(Laubichler2009),orconceptslikeevolvability(Hendrikseetal. 2007;see Section4.4).Theseperspectivesareintimatelyconnectedtohowboth evo-devoandstandardevolutionarytheoryareconceptualized: “[evo-devo] seekstoamplifyandextendthemodernsynthesisofevolutionarybiologyand geneticstoincludedevelopmentalgeneticsaswellaspopulationgenetics” (GilbertandBurian2003,68).Theyappearmorespecificallyinthecontextof problemdomains,suchastheoriginofevolutionarynovelty: “Itdoesnothelp muchtosaythattherewereoneortwomutationsthatcreatedeyespotsandthat thesealleleswereselected” (Wagner2000,97).

Onewayofsituatingevo-devogiventhislineofcriticismisbydistinguishing twoexplanatoryprojectswithinevolutionarybiology.The firstisassociated withaperspectivethatemphasizespopulationsandfunction.Evolutionary changefromonephenotypeortraittoanotherisexplainedviapopulation processessuchasnaturalselection,whichsortsphenotypes,altersgenefrequencies,andyieldsoutcomesthatarefrequentlythoughnotexclusively adaptive(DickinsandRahman2012; HoekstraandCoyne2007; Lynch 2007).Thesecondprojectisassociatedwithorganismsandstructure(Wagner 2014).Evolutionarychangefromoneontogenytoanotherisexplainedby avarietyofdevelopmentalgeneticandepigeneticprocesses,whichcanbe alteredindifferentwaystoproducenovelmorphologiesinorganisms (Amundson2005; Calcott2009; Laubichler2010). “Evo-devorepresents acausal-mechanisticapproachtowardstheunderstandingofphenotypicchange inevolution. itseekstoexplainphenotypicchangethroughthealterationsin developmentalmechanisms” (Müller2007,945–6;see Baedke2021).

Althoughthisinterpretivepossibilitybolsterstherationalefordistinguishing evo-devofromtheevolutionaryinquiryseeninpopulationgeneticsorbehavioralecology,itdoeslittleforsituatingevo-devowithinevolutionarytheory. Forexample,istheorganism-structureexplanatoryprojectsubsidiarytothe population-functionexplanatoryagenda,aprerequisiteforit,orsimplyorthogonal?Someevolutionarybiologistshaveaclearanswertothisquestion: “The litmustestforanyevolutionaryhypothesismustbeitsconsistencywithfundamentalpopulationgeneticprinciples ... populationgeneticsprovidesanessentialframeworkforunderstandinghowevolutionoccurs” (Lynch2007,8598).

Asmightbeexpected,someevo-devoproponentsdisagree: “Iamnotconvincedthatwhatwehavelearnedabouttheevolutionofformisbeing adequatelyconsideredincomparativegenomicsandpopulationgenetics, wherethepotentialroleofregulatorysequenceevolutionappearstobe asecondaryconsideration,orignoredaltogether” (Carroll2005b,1164).

SeanCarroll’saccentonthe “theevolutionofform” isanimportantsignalof whereevo-devomightbelocatedwithinthelargerpaletteofevolutionary biologybecausetheneedtoexplainthenatureandoriginofmorphology seemstorequireasubstantiveincorporationofembryologyandmolecular developmentalbiology.

Evolutionarydevelopmentalbiology(evo–devo)emergedasadistinct field ofresearchintheearly1980stoaddresstheprofoundneglectofdevelopment inthestandardmodernsynthesisframeworkofevolutionarytheory, adeficiencythathadcauseddifficultiesinexplainingtheoriginsoforganismalforminmechanisticterms.(Müller2007,943)

Atthetimeofthe “ModernSynthesis” ofevolutionarytheorythatdrewtogether variousdisciplinesincludinggenetics,paleontology,andsystematics,verylittle couldbesaidabouttheeffectsofgenesondevelopment,letaloneonthe evolutionofform. [Evo-devo]discoveriesforced evolutionarybiologists toconfrontanewsourceofunforeseenandpenetratinggeneticinsightsintothe generationanddiversificationofanimalform.(Carroll2008,25)

Thereferentof “ form ” intheseclaimsisstructureormorphology – the compositionandarrangement,shape,orappearanceoforganicmaterials.The contrastiswithfunction – activitiesperformedordisplayedbyorganisms.

Adifferentyetcomplementarywayofsituatingevo-devoinrelationtoevolutionarytheoryistoseeitasaddressingthe introduction ofvariation,whereas standardevolutionarymodelshavetreatedthe fate ofvariation(e.g., Stoltzfus 2021).Insteadoftwodifferentexplanatoryprojects,theevolutionaryprocessis splitintotwodistinctcomponents.Thispermitsdiscussionofwhetherpropertiesof mutationalprocessesordevelopmentthatchannelvariationcanbiastherateor directionofevolutionwithlesser,similar,orgreaterstrengththanprocesses involvedinthefateofthatvariation,suchasnaturalselection(Arthur2004). Traditionally,thiswasdiscussedundertherubricofdevelopmentalconstraints thatretardnaturalselection(MaynardSmithetal.1985).Inrecentdecades, discussionhasshiftedtoanemphasisonthepropertiesoflineagesthatcontribute toevolvability(Brigandt2015a; Stoltzfus2021;see Section4.4).Whatisatstake canbeillustratedconcretelyinaclassicembryologicalexperimentthatlooked attheorderofcondensationformationinamphibiandigitdevelopmentto accountforevolutionarypatternsofdigitalreductioninlineagesofthisclade

(AlberchandGale1985).Frogsexperiencethelossofpreaxialdigits(“bigtoes”) duringhindlimbdigitalreductionbecausethesedigitsformlastduringontogeny; salamanders,incontrast,losepostaxialdigits(“pinkytoes”)duringhindlimb digitalreductionbecausethesedigitsareformedlastduringontogenyinthis lineage(Figure3).Thedevelopmentalpatternofhowvariationisintroducedin theselineageshelpstoexplaintheevolutionaryoutcomeinawaythatselection forhindlimbreduction(i.e.,thefateofdigitalvariation),whichispresumedto havebeenoperative,doesnot.

Thesepossibilitiesforhowtothinkab outsituatingevo-devoinevolutionarytheoryarebynomeansexhaustive( Love2020 ).Theseandotherstrategies havemeritbutdependcruciallyonhowevo-devoischaracterized,andthere areseveraldistinctwaystoaccomplishthis( Section1.1). 4 Thus,insteadof attemptingtosettleonwhatmightbethebeststrategyforsituatingevo-devo inevolutionarytheory,itispreferabletoexplicitlyattendtowhatwethink

Figure3 Digitalreductiontrendsinfrogsandsalamanders.Asimplified, schematicrepresentationofhowtheorderofcondensationformationin amphibiandigitdevelopment(theintroductionofvariation)helpstoexplainthe evolutionarypatternofdigitalreductioninthesetwolineages(Alberchand Gale1985).(A)Frogsexperiencinghindlimbdigitalreductionlostpreaxial digits(“bigtoes”)becausetheyformedlastduringontogeny.(B)Salamanders experiencinghindlimbdigitalreductionlostpostaxialdigits(“pinkytoes”) becausetheyformedlastduringontogeny.Redrawn.

Source: Love(2015b).

4 Thisincludesquestionsaboutthemeaningandstatusoftypologicalthinkinginevo-devo (Amundson2005; Brigandt2021; Love2009b).

evo-devoisandthegoalsofourattemptstosituateit.Thelattermightinclude sortingoutaparticularcontroversy,establishingconnectionsbetweendisciplines,de finingthehorizonsofcurrentresearch,orclarifyingresearchquestions(Scheiner2010).Someformsofsituatingevo-devo,characterizedin aparticularway,maybebettersuitedtoachievingsomeofthesegoalsrather thanothers.However,theseeffortsalsodependonhowwecharacterize evolutionarytheoryandthereforeitalsorequiresexplicitconsideration.

1.3APleaforPluralism(AboutTheoryStructure)

Anunstatedassumptionofthisdiscussionaboutsituatingevo-devoisthatthereis asingleevolutionarytheoryinwhichtolocateit.Tospeakofanextendedor expandedtheoryofevolutionsuggestsweknowwheretheextensionswouldgoor whatportionsneedexpansion.Thiscanbeseenintheclaimseducedtocontrast standardevolutionarytheorizingassumptionsfromthoseofanEES(Lalandetal. 2015).Theseincludeabroadenednotionofinheritancebeyondgeneticmaterial (e.g.,culturalandecologicalinheritance)thatyieldsanexpandedviewofwhat countsasheritabletraitsofapopulationandtherebythenatureandtypesof evolutionaryprocesses.Thisthencouldaccountformacroevolutionarypatterns andcontributetoanunderstandingofevolvability.Commonterminologicalchoices inthesedescriptionsalignwithametaphorofspatialincrease: “encompass,” “broaden,” and “additional.”

Toexpandevolutionarytheoryistoincreaseitscontent;toextenditisto enlargetheboundariessuchthatmorethingsareencompassed.Theargumentfor expansionorextensionastheappropriatemodifiersforempiricalandtheoretical developmentsthatEESproponentsadvancederivesfromtheperceivedneedto preservemuchofwhatiscurrentlyinevolutionarytheory.Diagrammaticrepresentationsdepictclearlythatwhatisinviewinvolvesaformofspatialincrease (Figure4).However,wemightwonderwhattheconceptual “chunks” depictin theserepresentations:Howdoweconceptualizethecontentofevolutionary theory?Theserepresentationsdonottellusmuchabouthowthosechunks mightbeinterrelated,whichseemstobeanaturalassumptioniftheycompose thesametheory:Howisthecontentofevolutionarytheoryorganizedorstructured?Atmost,thediagramsuggestsa “core” orfoundationalstructure(centerof Figure4).Oftenthisisthoughtofastheapparatusofevolutionarygeneticsthat undergirdsanunderstandingofhowgenotypicandphenotypicchangesoccurin populationsduetonaturalselection,mutation,migration,andgeneticdrift.

Ideasabouttheorycontentandstructureinphilosophyofsciencesupply avarietyofanswerstothesequestions.Forcontent,wemightseparateout empirical findingsorknowledgeaboutadomain,modelsofhowphenomenain

Figure4 Representingevolutionarytheoryandtheextendedevolutionary synthesis(EES).Keyevolutionaryconceptsorganizedschematicallyinterms ofDarwinism(center field),theModernSynthesis(intermediate field),andthe EES(outer field),representingatrendofcontinuousexpansion.Redrawn.

Source: Pigliucciand Müller(2010a, figure1.1,p.11).©2010MassachusettsInstitute ofTechnology,bypermissionofTheMITPress.

thesedomainsbehave,andconceptsthatrepresentdiverseinstantiationsofthe phenomenathatarebeingpredicted,characterized,manipulated,orexplained(or doingtheexplaining).Thisfacilitatesdiscussionofwhethernewempirical findingsmustbeadded,modelsofphenomenarequirerevision,ornewconcepts mustbeinvokedtoaccomplishoneormorescientificaims.Forstructure,there aredescriptivequestionsabouthowempirical findings,models,andconceptsare organized:Howisknowledgereferredtoas “evolutionarytheory” orderedand arranged(Bock2010; Tuomi1981)?Doesithaveastructurethatissimilartoor differentfromotherscientifictheories(Lloyd1988)?Therealsoareprescriptive questions: Should weorganizeevolutionarytheoryinaparticularway? Should it besimilarinstructuretoothertheories?Questionsofthiskinddrawusinto aphilosophicalconversationaboutthenatureofscientifictheories(Winther 2021).Thesequestionsarenotwhollyseparatedfromthecontentofatheory, buttheyrequireexploringevolutionarytheoryfromananglethatisless frequentlycontemplatedbyworkingbiologists.

Theepistemicorganizationofevolutionarytheoryhaslongworriedhistorians andphilosophersofbiology(DepewandWeber1996).Itseemsanomalousin

comparisonwithotherscientifictheories,whichraisesaquestionaboutwhether existingphilosophicalanalysesoftheorystructureareapplicable(Caplan1978). Inpart,thisisbecauseevolutionarytheoryappearstoincludenumerouscommitmentsbeyondpopulationandquantitativegeneticmodelsofevolutionarychange andiscommonlyviewedasapackage: “thestandardmodernsynthesisframeworkofevolutionarytheory” (Müller2007,943).Theideaofa “framework” suggestsalternativecategories,suchasahypertheorythatsubsumessubordinate theoriesofevolutionarymechanisms(Wasserman1981),abundleoftheoriesthat involvenomologicalandhistoricalexplanations(Bock2010),orakindof Kuhnianparadigm(Gayon1990).

Philosophicalanalysesprovideuswiththreebasicoptionsforhowtothink abouttheorystructure:syntactic,semantic,andpragmatic(Winther2021).In boththesyntacticandsemanticviews,theorystructureisreconstructedin aformallanguage.Theformeristypicallyanaxiomatizationintermsof predicatelogic,wheretheaxiomsareoftenunderstoodaslawsthat,when combinedwithinitialandboundaryconditions,willexplaintherequisite domainofempirical findings.5 Forthesemanticview,reconstructiontypically occursinsettheoryasafamilyofmodelsthatmapontothoseusedinthe science.Thepragmaticviewismoreheterogeneousandservesasabroad catchallforapproachestotheorystructurethathewcloselytoscientificpracticesoftheoryuseandthereforeincludenotonlymathematicalformalismbut alsoavarietyofotherelements,manyofthemnonformal(e.g.,analogies, assumptions,andheuristicprinciples).Thereisnopresumptionthatthecontoursoftheorywillbesharedacrossallscientificdisciplinesandanemphasison boththepurposestowhichtheoryisputandthevaluesoftheresearch communitiesthatuseitsdifferentelementsregularly.

Theconcernsofbiologistsaboutstructuralorganizationandarrangement largelysuggestapragmaticorientation,thoughnotbecausetheothertwo approachesareincorrect.Forexample,therearefruitfulandilluminating analysesofevolutionarytheoryfromthevantagepointofthesemanticview (Lloyd1988).However,thepragmaticviewkeepsourattentiononhowbiologistsuseevolutionarytheoryinpractice.Andthisissomethingobservableat ourjunctureofconcern,therelationshipofevo-devotoevolutionarytheory.

Butdoquestionsposedaboutevo-devoandevolutionarytheorymatterto anyonebesidesthespecialistsandafewfuturehistorians?Ithinktheanswers matterverymuch.By “theory” here,Imean “structuresofideasthatexplain

5 Althoughatypical,afewbiologistsholdviewsoftheorystructureamenablewiththisreconstructiveapproach: “evolutionarytheoryisnotjustacollectionofseparatelyconstructedmodels,butis aunifiedsubjectinwhichallofthemajorresultsarerelatedtoafewbasicbiologicaland mathematicalprinciples” (Rice2004,xiii).

andinterpretfacts” Withouttheoriestoorganizeandinterpretfacts, withoutthepowerofgeneralexplanations,weareleftwithjustpilesof casestudies.Moreover,wearewithouttheframeworksthatenableusto makepredictionsaboutanyparticularcase.(Carroll2008,25)

These “structuresofideas” donotcomefromstandardevolutionarytheory: “theevolutionofformisthemaindramaoflife’sstory,bothasfoundinthe fossilrecordandinthediversityoflivingspecies” (Carroll2005a,294).General explanations,inthisinstance,donotrelyprimarilyonevolutionarygeneticsor itstheoreticalprinciples.Insteadof “nothingmakessenseinevolutionexceptin thelightofpopulationgenetics” (Lynch2007,8597),weget “nothingin evolutionmakessenseexceptinthelightofcell,molecular,anddevelopmental biology” (Kirschner2015,203).Weneedmorerefinedtoolsfortheorystructure thanappealstoexpansionorextensioncansupply.

Isuggestwecombinethepragmaticorientationtotheorystructurewith apluraliststance.Thereismorethanonelegitimatewaytostructureevolutionarytheoryandlocateevo-devoinrelationtoit.Whendifferentresearch questionsareinviewanddifferentaimsareundertaken,divergentexplanatory goalsandcriteriaofadequacycomeintoviewandleadtodistinctconfigurations ofvarioustheoryelements(Love2010a).Butwhatdoesitmeantosaythat evolutionarytheoryhasmorethanonelegitimatestructure?Whatdoesitmean toadoptapluraliststancetowardtheorystructure?First,itinvolvesarejection ofthepresumptionthat “thereisasingleperspicuousrepresentationsystem withinwhichallcorrectaccountscanbeexpressed” (Kellertetal.2006,xv). Second,ittakesseriouslynotonlytheheterogeneityoftheorystructurein scientificpracticeacrossdisciplinesbutalsowhatwe findwithindisciplines, suchasevolutionarybiology.Thereisanembraceof “anopennesstothe ineliminabilityofmultiplicityinsomescientificcontexts” (xiii).Insteadof engaginginreconstructiveeffortsthatofteninvolvethepostulationof “hidden” theorystructurethatisnotpresentinscientificdiscourse,westayfocusedon howevolutionarybiologiststhemselvescreateandusetheorystructuresof differentkindstoevaluatetheirownreasoning.

Apluraliststancefromapragmaticorientationconcentratesattentiononthe legitimacyofstructuresforevolutionarytheoryintermsoftheirsuccessorfailure withrespecttodifferentrolesthatcontributetoscientificaims,suchas:(1) articulatingtherelationshipsamongdifferentscientificdisciplinesinthetheory (orpartsofit);(2)facilitatingongoingresearchwithrespecttoparticularpartsof atheory,includingattemptstoanswerspecificresearchquestions;(3)presenting aspectsofthetheoryinpedagogicalcontextsforotherstoassimilate;or(4) comprehendingthehistoricaldevelopmentofmodelsorconceptsofthetheory. Thereisnoreasontothinkthatsuccesswithrespecttooneormoreoftheseroles

willbegetsuccesswithrespecttoanother.Differentroleshavedistinctand sometimesdivergentcriteriafordecidingwhenandwheredifferenttheory structuresobtainlegitimacy.Apluraliststancenotonlyleadsustoexpectdiverse structuresbutalsohelpstoexplainwhytheydivergeinthewaysthattheydo.

Differenttheorystructurescanbeinterpretedastheory “presentations” (Griesemer1984),whichrefertohowempirical findings,models,andconcepts arespecifiedinrelationtoresearchquestions.Apresentationofevolutionary theoryorsomesubsetofitislegitimatewhenitproducesadvantagestosome scientificend,suchasfacilitatingongoinginvestigationintonaturalphenomena withinadomain.Howscientistsuseevolutionarytheoryinpracticeguides preferencesaboutitsstructuralrepresentation;choicesaremadeintermsof whatwedowiththetheory(Love2013).Theorypresentationsarealways partialspecificationsthatareheuristicinnatureandthuspronetosystematic biases(Wimsatt2007).Theyoftenappearassummarynarrativesoftheevolutionaryprocess.6 Wecanunderstandthemasakindofmodelingthatinvolves idealization – knowinglyignoringvariationinpropertiesandexcludingvalues forvariables(Jones2005; Weisberg2013).Researchersknowinglymisrepresentaspectsofatheory,whetherempirical findings,models,orconcepts,inthe endeavorofaddressingresearchquestionsorpursuingotherscientificaims.

Onefruitfulapproachtoidealizedtheorypresentationisintermsofstructuredproblemagendas(Love2010a).Withinthisidealization,therelatively stabletopicsofevolutionarybiologyfoundacrosstextbookscorrespondto organizedarraysofconceptual,theoretical,andempiricalresearchquestions (“problemagendas”)aboutcomplexphenomenathatareconcurrentlytackled bymultipledisciplinaryapproaches.Thisidealizationoffersawaytounderstandhistoricalcontinuityinevolutionarytheory(e.g.,specificempiricalquestionscanchangewhiletheproblemagendaretainsitsidentity),drawsattention tohowdifferentdisciplinarycommunitiesmakedistinctexplanatorycontributions(inthecontextofdifferentproblemagendas),displayshowresearchis guidedinparticulardirections(byresearchquestionsinaproblemagendarather thanhypothesistesting),andaccountsformethodologicalchoicesandthe adoptionofexplanatorystandards.Italsodisplayshowdifferenttopicsin evolutionarytheorycoalescearoundmajordivisionsofbiologicalscience –genetics,cell,anddevelopmentalbiology;ecology;systematics – andexplains

6 E.g., “evolutionisconcernedwithinheritedchangesinpopulationsoforganismsovertime leadingtodifferencesamongthem. Geneswithinindividuals(genotypes)inapopulation, whicharepasseddownfromgenerationtogeneration,andthefeatures(phenotypes)ofindividualsinsuccessivegenerationsoforganismsdoevolve.Accumulationofheritableresponsesto selectionofthephenotype,generationaftergeneration,leadstoevolution” (Halland Hallgrímsson2008,3).

whyconcentratingononeormoreproblemagendasinevolutionarytheoryto theexclusionofotherscanleadtoadevaluingofdevelopmentalorecological factorsinouraccountsofevolutionaryprocesses(Figure5).

Importantly,thisidealizedpresentationofevolutionarytheorydoesnotcapture somefeaturesweoftenassociatewithevolutionarytheory.Itdoesapoorjobof recoveringthedistinctionbetweenpatternandprocess.Ifevolutionarytheoryis understoodintermsofmechanismsofchange,thentheinclusionofclassification isincongruent.However,thisisexactlywhatwewouldexpectfromdistinct choicesthatmotivatedifferenttheorypresentations.Theidealizedpicturein

Figure5 makesitdifficulttoseehowphenotypicplasticity(theenvironmental inductionofdifferenttraits)andnicheconstruction(organismsactivelyaltering theirenvironment) fitintoevolutionarytheory,bothofwhichhaveimportant placesinevo-devo(e.g., Moczeketal.2011)anddiscussionsofanEES(Laland etal.2015).Phenotypicplasticityisaphenomenonthatcombinesvariationand

Figure5 Anidealizedpictureofaneroteticstructureforevolutionarytheory. Thisstructureiscomposedofproblemagendasandtheirinterrelations,aswellas theircorrespondencetoprimarydomainsofbiologicalinquiry:systematics, ecology,andgenetics,cell,anddevelopment. “Erotetic” means “oforpertaining toquestioning” andderivesfromtheGreekword “erōtētikós.” Redrawn. Source: Love(2010a)

ecology;nicheconstructionisaphenomenonthatcombinesinheritanceand ecology.Theseconnectionsareopaqueanddifficulttorecoveronthistheory presentation.Yetthiswasintentionallyaccomplished;weknowinglymisrepresentedthoseaspects.Itisanidealization.Wecanputforwardanotheridealized theorystructure(Figure6)thatrepresentssomeofthesedrawbacks(e.g.,afocus onevolutionaryprocess,depictionoftheroleofphenotypicplasticityandniche construction,andthejuxtaposingofecologywithvariationandinheritance). However,weloseadvantagesassociatedwiththepreviousidealizedrepresentation(e.g.,howdifferentdisciplinarycommunitiesmakedistinctcontributionsor whataccountsformethodologicalchoicesandtheadoptionofexplanatory standards).Linguisticandpictorialtheorypresentationsalwaysinvolvetrade-offs.

Thediversityoftheorystructuresobservableinpresentationsofevolutionary theoryacrossdifferentrealmsofinvestigationcanbereinterpretedassetsof incompatibleidealizationsthatneednotberesolvableintoasingleperspicuous representationsystem.WedonothavetoinvokehypertheoriesorKuhnian paradigmstodissectthestructure(s)ofevolutionarytheoryorfussoverwhatis (orisnot)inthecore.Byimplication,differentstructuresforevolutionary theoryandevo-devo,andhowtheyrelatetooneanother,arenotinconstant

Figure6 Adifferentidealizedrepresentationofstructureforevolutionary theory.Thisstructureiscomposedofelementsthatemphasizetheprocessof evolutionarychangeandspecificallydepicttherolesofphenotypicplasticity (viaenvironmentalinduction)andnicheconstruction,aswellasdifferent channelsofvariationandinheritance.Forcomparison,seethenarrative summaryinfootnote6.Redrawn.

Source: Müller(2017)

competition.Whethertheyareconsideredrivalsdependsonwhethertheyshare scientificaims.Thediversityofmethodologicalandepistemologicalgoalsin evolutionarytheoryimpliesthatapluraliststanceisagoodstrategyforadvancingourunderstandingofevolution: “theexplanatoryandinvestigativeaimsof science[may]bebestachievedbysciencesthatarepluralistic,eveninthelong run” (Kellertetal.2006,ix–x).

2ModelOrganisms(andMore)

2.1CriteriaforandCategoriesofModelOrganisms

Thedemonstrationofhomeoboxgeneconservationthatencapsulatedthegenerativemomentrecalledbymanybiologistsaslaunchingevo-devowasaccomplishedinmodelorganismslikethefruit fly,chicken,andmouse(Section1, Figure1).Modelorganismsarecentraltocontemporarybiologyandstudiesof embryogenesisinparticular(AnkenyandLeonelli2011; BierandMcGinnis 2003).Biologistsutilizeonlyasmallnumberofspeciestoexperimentally elucidatevariouspropertiesofontogeny.Theseexperimentalmodelspermit researcherstoinvestigatedevelopmentingreatdepthandfacilitatethedetailed dissectionofcausalrelationships.Acommonjustificationfortheiruseisthe conservedgeneticmechanismssharedbyallmetazoans(KirschnerandGerhart 1998),suchascollinearexpressionof Hox genestospecifybodyaxes (McGinnisandKrumlauf1992).Thecentralityofconservedmechanismsin modelorganismresearchhelpedtocementthehomeoboxdiscoveryasthe initiatingmomentforevo-devo(Section1.1).Whatexactlyaconservedmechanismamountstowillbeourfocusin Section3.Thepresentsectionexplores criteriaandexamplesofmodelorganismuseinbiology,withaspecialfocuson evo-devowheretherehasbeenexplicitconcernabouttheirstatus(Bolker2014; JennerandWills2007; LoveandYoshida2019; MinelliandBaedke2014).

Developmentalmodelorganismsaretypicallyusedtoestablishcoresimilaritiesexemplifiedbymanytaxa,especiallywithaneyetowardmedicalapplication(BierandMcGinnis2003).Criticshavequestionedwhetherthesemodels aregoodrepresentativesofotherspeciesbecauseofinherentbiasesinvolved intheirselection,suchasrapiddevelopmentandshortgenerationtime (Bolker1995),aswellasproblematicpresum ptionsabouttheconservation ofgenefunctionsandregulatorynetworks(Lynch2009 ).Biologistsalso routinelydiscuss “non-model ” organisms( Russelletal.2017).Toavoid agameofclaimandcounterclaimaboutwhatcountsasagoodmodel(ornonmodel)organism,itishelpfultofocusontwoelementsofscientifi cpractice: (1) criteria thatbiologistsusetoevaluatemodelorganisms,and(2)different categories ofmodelorganismsthathavebeenintroducedtocapture

standardizedcombinationsorspecifi cationsofthesecriteriaindifferent arenasofinquiry.

Twomajorcriteriausedtoevaluatemodelorganismsare representation and manipulation (LoveandTravisano2013).7 Theformerconcernswhatbiologicalsystemsamodelcanrepresentandtowhatextent.Thelatterconcerns easeofempiricalexaminationofamodel. AnkenyandLeonelli(2011) emphasizetwodimensionsoftherepresentationalcriterion:scopeandtarget. Representationalscope describeshowwidelyandtowhatbiologicalsystems theresultsandlessonslearnedbystudyingamodelsystemareprojected.If aresearchgroupuseszebrafishtolearnaboutvertebrates,thenzebrafishas amodelorganismissupposedtohavevertebratesasitsrepresentationalscope. Representationaltarget indicateswhatbiologicalphenomenaareexploredby studyingthemodelsystem.Iftheresearchgroupuseszebrafishtoexplorehow neuralectodermbecomeshindbrain,thennervoussystemdevelopmentisthe representationaltarget.Inmanycases,thechoiceofrepresentationaltargetis connectedtorepresentationalscope.Forexample,thestudyofgeneticand cellular mechanisms indevelopment(representationaltarget)andthediscovery thattheyarewidelyconservedevolutionarily(representationalscope)is asignificantmotivatorforthecontinueduseofmodelsystems(Ankenyand Leonelli2011).Additionally,therepresentationaltargetmightbeahigher-level phenomenon insteadofamolecularmechanism,andeitherofthesecanbe scrutinizednarrowly(specificity)orwithrespecttoarangeofvariationonthe theme(variety)(Table1).

Manydifferentfactorsarerelevanttothecriterionofmanipulation.Examples includeorganismavailability,thecostofinitiatinginquiry,possibleexperimental techniquesthatcanbeapplied,andhowquicklyonecanproducedataandresults (AnkenyandLeonelli2011; LoveandTravisano2013).Althoughthereare differencesinthedegreetowhichthesefactorsmustbepresentandhowthey arefulfilled(e.g.,availabilitymightbeachievedthroughchemicallypreserving andstoringspecimens),itiswidelyacceptedthatmanipulationisacrucial criterionformodelorganisms.Furthermore,thecriteriaofrepresentationand manipulationareinterrelated.Insomecases,theyexhibitatrade-offrelationship; amodelthatfaithfullyrepresentsorganismsofinterestmightbedifficultto experimentallymanipulate,oranorganismthatiseasytomanipulatemight representaphenomenonofinterestpoorly.Biologistschooseandevaluate

7 Dietrichetal.(2020) providea fine-grainedanalysisoftwentydifferentcriteriaforchoosing aresearchorganismunder fivethematicclusters.Itisespeciallydetailedwithrespecttothe diversityofpragmaticcriteriainvolved(e.g.,easeofsupply,viabilityanddurability,training requirements,andinstitutionalsupport).

Table1 Representationalcriteriaformodelorganisms.

Representational scope Isrelated to Phenomena or mechanisms Focusedon Specificity or variety

Representational target Is Phenomena or mechanisms Withrespect to Specificity or variety

Asummarydepictionoftherepresentationalcriteriaformodelorganisms.Readingfrom lefttorightgeneratesphrasesthatsummarizemotivationsformodelorganismpractices. Forexample,representationalscopecanberelatedtodevelopmentalmechanisms,suchas collinear Hox geneexpression,focusedontheirvariety(e.g.,establishinganterior–posterioraxesofthebodyversusestablishingproximal–distalaxesofappendages).Or, therepresentationaltargetcanbedevelopmentalphenomena,suchasgastrulation,with respecttotheirvariety(e.g.,delamination,epiboly,ingression,invagination,and involution).

modelorganismsbyconsideringthesecriteriajointly,givingweighttodifferent factorsintermsofwhattheyaimtoaccomplish(i.e.,theirresearchpurposes).

Configurationsofdifferentcombinationsandspecificationsofthesecriteria yieldavarietyofmodelorganismcategories. AnkenyandLeonelli(2011) distinguish model organismsfrom experimental organisms.Thesedifferintheir representationalscope,representationaltarget,manipulativerequirements,and purposesofresearch. “Modelorganisms” correspondtoalimitednumberof speciesthathavebeenwidelyusedinbiologicalresearch,suchasthemouseor thefruit fly.Studiesofmodelorganismshavevariousgenetic,developmental, physiological,ecological,andevolutionaryphenomenaastheirtarget,especially thosethatoccurinorganismsgenerally.Resultsofthesestudies(e.g.,identified mechanisms)aregeneralizedtoawiderangeofotherspecies.Importantmanipulativerequirementsformodelorganisms(inthissense)aretheabilitytoundertake geneticanalysisandsuccessfulstandardizationtominimizeconfoundingvariation(e.g.,purelinesorstrains).Theyarestudiedforthepurposeofsecuring “anintegrativeunderstandingofintactorganismsintermsoftheirgenetics, development,andphysiology” (AnkenyandLeonelli2011,319).

Incontrast, “experimentalorganisms” arestudiedtoexplorespecificbiological phenomena.TheyexemplifytheKroghprinciple: “Foralargenumberofproblemstherewillbesomeanimalofchoiceorafewsuchanimalsonwhichitcanbe mostconvenientlystudied” (Krogh1929,202).Anexampleisstudyingfertilizationinseaurchins.Experimentalorganismsarechosentoanswerspecific questions,whichmeansthateachonetypicallyhasspecificphenomenaasits representationaltarget(Greenetal.2018).Inthecaseofexperimentalorganisms,

theresultsoftheresearchareoftengeneralizedorextrapolatedmorenarrowly thanresultsderivedfrommodelorganisms.Theyarealsonotasstandardizedand lesssuitableformanyformsofgeneticanalysis.However,thisisnotaninherent drawbackbecausemanipulativerequirementsvarydependingonwhatquestions arebeingaddressed.Thegiantsquidaxonwasstrategicforelectrophysiological experimentstoascertainneuronalfunctionbecauseitscomparativelylargesize madeitpossibletoreliablyapplyvoltageclamps.

Anotherhelpfuldistinctionseparates exemplary and surrogate models (Bolker2009).Exemplarymodelsarestudiedasexamplesoflargergroupsof organisms,suchaszebrafishasamodelofvertebrates.Theresultsacquiredby investigatinganexemplarymodelaregeneralizedtoalargergroupofwhichthe modelspeciesisamember.Developmentalbiologymodelorganismsare exemplaryinthissense: “Themotivationfortheirstudyisnotsimplyto understandhowthatparticularanimaldevelops,buttouseitasanexampleof howallanimalsdevelop” (Slack2006,61).Ontheotherhand,surrogatemodels serveassubstitutesforspecificbiologicalsystems.Theresultsderivedfrom themareextrapolatedtoaspecifictarget.Anexampleistheuseofthemouseas amodelforhumansystemsorphenomena(CheonandOrsulic2011).The inferenceisfromaproxytoatargetinsteadoffromanexemplartoothertaxa moregenerally.Differentrolesplayedbyexemplarymodelsandsurrogate modelsarisefromdifferentinvestigativepurposes.Forexemplarymodels,the goalistoidentifywidelysharedbiologicalmechanismsorbetterunderstand evolutionaryprocesses.Asaresult,theyareassociatedwithbasicresearch.In contrast,surrogatemodelsareusedinapplied fields,suchasbiomedicineor conservationresearch,tobetterunderstandmedicalorecologicalproblemsand developpotentialsolutions.

2.2ModelCladesandLifeHistories

Althoughmostaccountsofthecriteriaandcategoriesformodelorganisms havebeenconcernedwithorganismsofspecifi c species,therearealsoperspectivesthatfocusondifferentlyarrayedbiologicalsystems.Thenotionof amodel taxon referstoaclade(agroupderivedfromacommonancestor)that isusedtoinvestigatediversequestionsaboutgenetic,developmental,physiological,ecological,andevolutionaryphenomenawithinacladeandidentify generalizationsapplicabletootherclades(Griesemer2015).Thus,therepresentationalscopeofamodeltaxonisunderstoodastaxawithinandbeyondthe clade,withresultsascertainedthroughinvestigationapplyingdifferentiallyto individualtaxaofsmallerandlargersizes.Inquiryisorganizedaround interrelated “ packagesofphenomena” astherepresentationaltarget – rather

thanindividualphenomena – andtheseconstitutecentralfeaturesofthe evolutionofthetaxon.Forexample,lunglesssalamandershavebeenstudied asamodeltaxonandprovidedexplanatoryinsightsabouttheevolutionof anatomicalfeatures(e.g.,thetongueorbodysize)andassociatedfunctional systems(e.g.,feeding,locomotion,etc.),especiallywithrespecttomechanismsthatcontributetothesepatterns(e.g.,miniaturizationderivedfrom changesindevelopmentaltiming)( WakeandLarson1987).Anotherprominentmodeltaxonusedtoinvestigateecologicalandevolutionaryquestionsis thesquamategenus Anolis,whichiscomposedofmanylizardspecieswith goodphylogeneticresolution,whilealsobeingregionallydelimitedand relativelyaccessible(Sanger2012 ).

Griesemerusestheterm “ export ” torefertothepredominantinference madefrommodeltaxa,whereexportationisdistinguishedfrominferences involvingsimplegeneralization.Thelatteriscommoninmolecularbiology andoperatesbyassumingthatconspeci ficindividuals(orspeciesmembers) areinstancesofthesametype.Exportationisbasedontheideathattaxaare historicalindividualsandingenealogicalrelationshipswithoneother. Althoughdiscussionsofmodelorganismstendtofocusonhowparticular resultsacquiredbystudyingthemareextrapolated,generalized,orexported, Griesemeralsoemphasizesadditionalkindsofpayoffsthatcanbeacquiredby studyingmodeltaxa,suchasmethodologicallessonsabouthowtoinvestigate differenttaxa.

Anotherdistinctcategoryisamodel lifehistory (LoveandStrathmann2018). Thesearetemporalsequencesthatoccurwithintheontogenyoforganisms, characterizedintermsoffunctionalandmorphologicalproperties,whichare usedasmodelsofdevelopmentalsequencesfoundinotherspecies.Marine invertebratelarvaeareaprimaryexample(Love2009a).Unlikeamodeltaxon, thesestagesoflifehistoryarenotunifiedwithinasinglemonophyleticgroupor clade.Often,studiesofmarinelarvaeinvolvecross-cladecomparisonsof functionalrequirementsforspecificecologicalsettingsthatexhibitabroad butdisjointtaxonomicdistribution(i.e.,theirrepresentationalscope).The representationaltargetsofinvestigationsofmodellifehistoriesarefunctional ormorphologicaltraitsinontogeneticsequencesrelevanttoquestionsabout developmental,ecological,andevolutionaryphenomena.Someresultinggeneralizationsrevolvearoundinstantiationsoflarvalformsthatexemplify abroadertype(e.g.,thetrochophoreofmollusksandannelids),whileothers pertaintobehavioralandecologicalpatterns,suchasfeedingversusnonfeeding orplanktonic(floatingintheopensea)versusbenthic(livingontheseafloor). Modellifehistoriesconcentrateattentiononproblemsrelatedtoadaptationand phylogeny.Theyservetocoordinateresearchbyscientistsfromdifferent

Figure7 Thestarletseaanemone,anevo-devomodelsystem. Adaptedfrom:WikimediaCommons(CCBY-2.0).RobertAguilar,SmithsonianEnvironmentalResearchCenter. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nematostella_ vectensis_(I1419)_999_(30695685804).jpg

disciplines,oftenatmarinestationswheretheavailability,cost,andinfrastructuralprerequisitesformanipulationareinplacetosupporttherelevantconfigurationofapproachessimultaneously.

2.3Evo-DevoModels:SomethingSimilar,SomethingDifferent Forevolutionaryresearchers,akeyinvestigativeaimisestablishingsigni ficantpatternsofdifference(i.e.,evoluti onarychange),oftenmanifestedacross aclade,ratherthanonlysameness(i.e.,conservation).However,thesetwo endsofacontinuumareentangledintheuseofmodelsystemswithinevodevo.Theestablishmentofconservationorhomologyforacharactercan provideabasisfromwhichtoidentifyandcharacterizeevolutionarydivergenceinthatcharacterortheoriginofnewones(see Section4 ).Giventhis entanglement,itisunsurprisingthatresearchershaveoftenre fl ectedmethodologicallyonmodelorganismsinevo-devo( Bolker2014 ; Milinkovitch andTzika2007 ; MinelliandBaedke2014 ; Sommer2009 ),especiallyincalls tointroduceandstandardizenewones(e.g., Almudietal.2019 ; Laprazetal. 2013 ). “ Modelorganisms ... areconceptualcarry-overfromdevelopmental biology,buttheirstudywascrucialinestablishingevo – devoasanewdiscipline ” ( JennerandWills2007 ,311).Thisconceptualcarryoverincludesthe criterionofmanipulationbecauseexperimentaltractabilityisanimportant aspectofevo-devomodelsystems.Theresultsacquiredbystudying

experimentallytractablemodelsystemsinevo-devoarebothgeneralizedor extrapolatedtoparticulartaxa(developmentalmodelingemphasizingsimilarities)andcomparedphylogeneticallytoothertaxa(evolutionarymodeling emphasizingdifferences). 8

Thereasoningstrategiesassociatedwithevo-devomodelsystemshave distinctivefeaturesandarenotsuf fi cientlycharacterizedbyanyoneofthe accountsofmodelorganismsreviewedthusfar.Onecentralfeatureisthe importanceofphylogeneticallyinformedcomparison.Althoughresultsand lessonsacquiredbystudyingmodelsystemsinevo-devoaregeneralizedor extrapolated,asinmanyothermodelorganisms,thisistypicallyfollowed bycomparisonswithtaxarelatedbypatternsofcommondescent.These comparisonsarecrucialforelucidatingtheoriginofnoveltraitsin alineage,theevolutionofpropertiesofontogeny,anddissectingthe relevantin fl uenceofdevelopmentalprocessesonevolutionarymechanisms, allofwhichmotivatetheuseofmodelsystemsinevolutionarydevelopmentalresearch.

Agoodexampleofanevo-devomodelsystemisthestarletseaanemone, Nematostellavectensis ( Figure7 ; Darlingetal.2005 ; Genikhovichand Technau2009 ; Laydenetal.2016 ).Ithasmanypracticaladvantagesfor experimentalstudies:easilymaintainedinlittlespaceandatalowcost; adultsreproduceunderlaboratoryconditionsaboutonceaweekand throughouttheyear;eggsarelargeenoughformanipulation;andthe generationtimeisrelativelyshort.Resourcesandmanipulationtechniques availableincludeanannotatedgenome, insitu hybridizationandimmunohistochemicalanalysis,andknockdown/knockouttechniquesfrommoleculargeneticanalysis.

Animportantproblemtowhich Nematostella cancontributeanswersis theevolutionofbilaterality.Bilateralsymmetryoriginatedinanimalsmore than600millionyearsago,andevo-devoresearchershavetriedtodetect whenandexplainhowthetwomajorbodyaxes(anterior – posterior(A-P) anddorsal – ventral(D-V))emerged( Erwin2020 ).Toaccomplishthis requirescomparingbilaterianaxisformation(e.g.,in Drosophila or mouse)withtheancestralpatternofdevelopment. Nematostella belongs tothephylumCnidaria,whichisanout-groupofBilateriathatincludes corals,jelly fi sh,hydras,andseaanemones(Figure2).Itisexpectedtoserve asamodeloftheancestralpatternofdevelopmentinmetazoansonthe

8 Toavoidterminologicalconfusion,Irefertoevo-devomodel “systems” ratherthanevo-devo model “organisms” (LoveandYoshida2019).However,thischoiceofterminologyisforthesake ofclarityanddoesnotreflectanunderlying,substantivedistinctionbetweensystemsand organisms.

assumptionthatextantmembersofthisout-grouphaveretainedsigni fi cant featuresofthispattern.Althoughitappearstoberadiallysymmetrical, Nematostella hastwobodyaxes:theoral – aboralaxisrunsfromthemouth totheotherendofthebody,andthedirectiveaxisrunsacrossthepharynx, orthogonaltotheoral – aboralaxis.Moleculardevelopmentalstudieshave revealedrelationsofsimilarityanddifferencebetweenthebodyaxesof Nematostella andtheA-PandD-Vaxesofbilaterians,providinginsightinto howtheprimaryandsecondaryaxesofsymmetryinanimalsoriginated.

ConsiderWnt/ β -cateninsignaling,whichpla ysacrucialroleinA-Paxis speci fi cationacrossbilaterians( PetersenandReddien2009 ). 9 Inmanybilaterianspecies,Wnt/ β -cateninsignalingisdiffere ntiallyactivatedatcertain stagesofembryonicdevelopmentandindifferentlocationsoftheembryo. Duringearlyembryogenesis,thesideoftheembryowithhighWnt/β -catenin signalingactivitydevelopsintotheposteriorend,whilethesidewithlower signalingactivitybecomestheanteriorend.Becauseofthis,thefunctionof Wnt/ β -cateninsignalinginoral – aboralaxisspeci fi cationhasbeenexamined in Nematostella .Fromthemid-blastulastagewheretheembryoisahollow ballofcells, Wnt geneexpressionexhibitsademarcated,staggeredexpressionwithintheoralhalfoftheembryo(Kusserowetal.2005 ).Overactivation ofWnt/β-cateninsignalingpromotesoralidentity,whileinhibitionleadsto expandedexpressionofaboralmarkersandreductionoforalmarkerexpression (Röttingeretal.2012).

TheseresultspointtowardaroleforWnt/β-cateninsignalinginprimaryaxis specificationthatexistedbeforetheseparationofBilateriaandCnidaria (PetersenandReddien2009).Theyalsohintatapotentialcorrespondence betweenbilateriananteriorandcnidarianaboralaxes,ontheonehand,and betweenbilaterianposteriorandcnidarianoralaxes,ontheother.However, morerecentworkdemonstratesthatthedirectiveaxisof Nematostella isunder thecontrolofanaxial Hox genecode – adevelopmentalcharacteristicofthe metazoanA-Paxis – whichindicatesthatmolecularsignalingpathwaysfrom bothaxialspecificationmechanismsinbilateriansarepresentindirectiveaxis specification(Heetal.2018).Thissuggeststhatthereisnostraightforward relationshipofhomologybetweentheoral–aboralanddirectiveaxesof Nematostella andtheA-PandD-Vaxesofbilaterians.

9 TheWnt/β-cateninpathwayismadeupoffourbasicsegments:anextracellularsignal, amembranereceptor,cytoplasmicinteractors,andacomponentthattranslocatestothenucleus. TheextracellularsignalsareprimarilyWntproteins;akeyplayerinthecytoplasmicinteractions andeventualtranslocationtothenucleusis β-catenin.Indevelopment,thispathwayinitiatesgene expressionrelatedtocellproliferationandtheregulationofcellpolarityandmigration(van AmerongenandNusse2009;see Section3 forfurtherdiscussion).