NG

Contents

Contributors xi

Preface xvii

Share Global Health Nursing in the 21st Century

Unit i: FoUndations oF Global nUrsinG 1

Suellen Breakey and Patrice K. Nicholas

1: Global Health and Global Nursing 3

Patrice K. Nicholas and Suellen Breakey

2: Climate Change, Climate Justice, and Environmental Health Issues 25

Patrice K. Nicholas, Suellen Breakey, Shira Winter, Eleonor Pusey-Reid, and Ana M. Viamonte-Ros

3: A Foundation for Global Health, The Lancet Report on Health Professionals for a New Century: An Interview With Dean Julio Frenk 41

Patrice K. Nicholas

Commentary

Shira Winter, Holly Fulmer, Suellen Breakey, and Patrice K. Nicholas

4: Global Health Ethics 49

Suellen Breakey and Linda A. Evans

5: Health, Human Rights, and Social Justice: An Interview With Paul Farmer and Sheila Davis 73

Patrice K. Nicholas

Commentary

Suellen Breakey, Patrice K. Nicholas, Shira Winter, Nancy L. Meedzan, and Inge B. Corless

6: The Intersection of Global Health and Community/Public Health Nursing 85

Karen Anne Wolf

7: Global Health Partnerships 103

Anne Sliney

Unit ii: issUes in Global HealtH 113

Nancy L. Meedzan

8: The Importance of Water for Global Nursing 115

Suzanne S. Prevost and Tabatha Dye

9: Access to Clean Water and the Impact on Global Health: An Interview With Gary White, CEO and Cofounder, Water.org 123

Nancy L. Meedzan, Patrice K. Nicholas, Suellen Breakey, and Inge B. Corless

Commentary

Nancy L. Meedzan, Suellen Breakey, Patrice K. Nicholas, Shira Winter, and Inge B. Corlesss

10: The Impact of HIV/AIDS on the Nursing Profession in Sub-Saharan Africa 137

Busisiwe Rosemary Bhengu and Busisiwe P. Ncama

11: Vulnerable Populations: Ethical Issues in HIV Care 157

Carol Dawson-Rose and Denise Kelsey Wishner

12: The Role of Midwives and Nurses in Reducing Global Maternal Mortality Around the World and in Haiti 173

Erin George

13: Violence Against Women 193

Annie Lewis O’Connor, Karen A. Conley, and Suellen Breakey

14: Sex Trafficking as a New Pandemic 211

Mary de Chesnay

15: Complex Issues in Conflict Areas 229

Antonia Makosky

16: Mental Health of Asylum Seekers 253

Jayden Nadeau, Patrice K. Nicholas, and Susan Stevens

17: Childhood Malnutrition in India 281

Diane E. Hazel, Elissa C. Ladd, and Ansuya Begre

18: End-of-Life Care in a Global Health Context 307

Inge B. Corless, Rana Limbo, Regina Szylit Bousso, and Kim Rochon

Unit iii: aCHievinG Global HealtH 327

Inge B. Corless

19: Expanding Access to Address Priority Health Needs in Low-Resource Settings 331

Deborah von Zinkernagel, John Palen, and Avril Kaplan

20: The Challenges of International Nurse Migration: Seeking Global Solutions 357

Carol L. Huston

21: Nursing Leadership in Interprofessional Education 375

Nancy Hoffart, Elizabeth J. Brown, and Susan E. Farrell

22: The Importance of Continuing Education in Global Health Nursing 391

Lynda Tyer-Viola

23: Nursing Education and Practice in China and Thailand 407

Puangtip Chaiphibalsarisdi, Bridget E. Meedzan, Patrice K. Nicholas, and Nancy L. Meedzan

24: Professional Nursing Education in South Africa 421

Hester C. Klopper and Leana R. Uys

25: Cultural Immersion Experiences in Nursing Education 441

Nancy L. Meedzan

26: Working Globally With Faith-Based Organizations 453

Teri Lindgren, Sally Rankin, and Ellen Schell

27: Global Nursing Issues in China: A Partnership of Boston Children’s Hospital and Shanghai Children’s Medical Center 471

Patricia A. Hickey, Jianhua Lou, and Lily Hsu

28: Developing a Sustainable Model for Cardiovascular Care in Rwanda 485

Ceeya Patton-Bolman, Noella Bigirimana, and Julie Carragher

29: Dreyfus Health Foundation: Advancing the Future of Global Health Nursing 509

Pamela Hoyt-Hudson, Hsin-Ling Tsai, Joyce J. Fitzpatrick, and Barry H. Smith

30: The Fulbright Scholar Program and Nursing in Southern Africa 531

R. Kevin Mallinson

31: Interdisciplinary Collaborations in Global Health Research 547

Ann Kurth, Allison Squires, Michele Shedlin, and James Kiarie

Index 565

Contributors

Ansuya Begre, RN, RM, MSc(N) Manipal College of Nursing, Manipal University, Karnataka, India

Busisiwe Rosemary Bhengu, PhD, RN Chairperson, South African Nursing Council; Honorary Associate Professor, School of Nursing and Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard Campus, Durban, South Africa

Noella Bigirimana, BS Project Manager, Team Heart Inc., Newton, Massachusetts

Regina Szylit Bousso, RN, MS, PhD Associate Professor, School of Nursing, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Suellen Breakey, PhD, RN Assistant Professor, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts

Elizabeth J. Brown, RN, MSN, MBA Director, Global Nursing Programs, Partners Healthcare International, Boston, Massachusetts

Julie Carragher, MS, RN, ACNP Clinical Instructor, Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts

Puangtip Chaiphibalsarisdi, PhD, RN Associate Professor and Dean, School of Nursing, Shinawatra University, Pathumthani, Thailand

Karen A. Conley, DNP, RN Associate Chief Nurse, Connors Center for Women and Newborns, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Inge B. Corless, PhD, RN, FAAN Professor, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts

Sheila Davis, DNP, RN, FAAN Chief Nursing Officer, Partners In Health, Boston, Massachusetts

Carol Dawson-Rose, PhD, RN, FAAN Associate Professor, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California

Mary de Chesnay, PhD, DSN, RN, PMHCNS-BC, FAAN Professor, WellStar School of Nursing, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, Georgia

Tabatha Dye Graduate Research Assistant, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Linda A. Evans, PhD, RN Assistant Professor, MGH Institute of Health Professions; Nurse Researcher, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Paul Farmer, MD, PhD Koloktrones University Professor, Harvard Medical School; Chair of Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Chief of the Division on Global Health Equity, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Susan E. Farrell, MD Program Director, Partners Healthcare International, Boston, Massachusetts

Joyce J. Fitzpatrick, PhD, MBA, BSN, RN, FAAN Professor of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio

Julio Frenk, MD, MPH Dean of the Faculty, Harvard School of Public Health; T & G Angelopoulos Professor of Public Health and International Development, Harvard School of Public Health and Harvard Kennedy School, Boston, Massachusetts

Holly Fulmer, RN, MSN Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Erin George, MSN, CNM, RN Nurse Midwife, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Diane E. Hazel, MSN, MPH, RN School Nurse, Canton Public Schools, Canton, Massachusetts

Patricia A. Hickey, PhD, MBA, RN, FAAN Vice President, Cardiovascular and Critical Care Services, Boston Children’s Hospital; Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Nancy Hoffart, PhD, RN Founding Dean and Professor, Alice Ramez Chagoury School of Nursing, Lebanese American University, Byblos, Lebanon

Pamela Hoyt-Hudson, BSN, RN Global Nursing Coordinator, Dreyfus Health Foundation, The Rogosin Institute, New York, New York

Lily Hsu, MS, RN Director, Project Hope Education, China

Carol L. Huston, PhD, RN, FAAN Past President, Sigma Theta Tau International; Director, School of Nursing, California State University, Chico, California

Avril Kaplan, MSc Senior Analyst, Abt Associates, Washington, DC

James Kiarie, MBChB, MMed, MPH University of Nairobi, Center for HIV Research and Prevention, Nairobi, Kenya

Hester C. Klopper, PhD, RN, RM, MBA, FANSA President, Honor Society of Nursing, Sigma Theta Tau International; Professor, Northwest University and University of the Western Cape, Pretoria, South Africa

Ann Kurth, PhD, RN, FAAN Professor and Executive Director, New York University College of Nursing Global; Associate Dean for Research, New York University Global Institute of Public Health, New York, New York

Elissa C. Ladd, PhD, RN, FNP-BC Associate Professor, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts

Rana Limbo, PhD, RN, PMHCNS-BC, CPLC Bereavement and Advance Care Planning Services, Gundersen Health System, LaCrosse, Wisconsin

Teri Lindgren, PhD, MPH, RN Assistant Professor, Rutgers the State University of New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey

Jianhua Lou, RN Chief Nursing Officer, Shanghai Children’s Medical Center, Shanghai, China

Antonia Makosky, MS, MPH, ANP-BC Clinical Assistant Professor, School of Nursing, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts

R. Kevin Mallinson, PhD, RN, AACRN, FAAN Associate Professor, Assistant Dean Doctoral Division, School of Nursing, College of Health and Human Services, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia

Bridget E. Meedzan, BS Clinical Research Coordinator, AED Pregnancy Registry, Pediatrics Department, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Nancy L. Meedzan, DNP, RN, CNE Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Endicott College, Beverly, Massachusetts

Jayden Nadeau, RN, MSN, PMHNP-BC Nurse Practitioner, ConnectionsAZ, Phoenix, Arizona

Busisiwe P. Ncama, PhD, RN Associate Professor, Dean and Head of School, Nursing and Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College Campus, Durban, South Africa

Patrice K. Nicholas, DNSc, DHL (Hon), MPH, MS, RN, ANP, FAAN Director of Global Health and Academic Partnerships, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Senior Nurse Scientist, Division of Global Health Equity and Center for Nursing Excellence; Professor, MGH Institute of Health Professions School of Nursing, Boston, Massachusetts

Annie Lewis O’Connor, PhD, MPH, NP-BC Director, Women’s C.A.R.E. Clinic, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

John Palen, PhD, MPH Senior Human Resources for Health (HRH) Advisor, Abt Associates, Washington, DC

Ceeya Patton-Bolman, MSN, RN Program Coordinator, Team Heart, Inc., Newton, Massachusetts

Suzanne S. Prevost, PhD, RN, COI, FAAN Dean, University of Alabama School of Nursing, Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Eleonor Pusey-Reid, RN, DNP, MS, MEd, CCRN Clinical Assistant Professor, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts

Sally Rankin, PhD, RN, FAAN Professor and Associate Dean, Global Health and International Programs, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California

Kim Rochon, MSN, RN MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts

Ellen Schell, PhD, RN, FAAN International Programs Director, Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance; Associate Adjunct Professor, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California

Michele Shedlin, PhD Professor, College of Nursing, New York University, New York, New York

Anne Sliney, RN, ACRN Chief Nursing Officer, Clinton Health Access Initiative; Faculty, Brown University AIDS Program; Chief Nursing Officer, Clinton Foundation, Boston, Massachusetts

Barry H. Smith, MD, PhD President and Chief Executive Officer, The Rogosin Institute; Director, The Rogosin Institute of Dreyfus Health Foundation; Director, Research, The Rogosin Institute Xenia Division; Professor of Surgery, Weill Medical College of Cornell University; Attending Surgeon, New YorkPresbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell, New York, New York

Allison Squires, PhD, RN Assistant Professor, Deputy Director, International Education and Visiting Scholars, New York University College of Nursing, New York, New York

Susan Stevens, DNP, MEd, MSN, PMHNP-BC Clinical Instructor, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts

Hsin-Ling Tsai, MHA Dreyfus Health Foundation of the Rogosin Institute, Taipei, Taiwan

Lynda Tyer-Viola, PhD, RNC, FAAN Director, Women’s Services, Texas Children’s Hospital; Adjunct Faculty, Texas Woman’s University–Houston Campus, Houston, Texas

‡ Leana R. Uys, PhD, RN Professor Emerita and Fellow of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Ana M. Viamonte-Ros, MD, MPH Associate Dean for Women in Medicine and Science, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine; Associate Professor, Department of Humanities, Florida International University; Director of Medical Staff Development, Baptist Health South Florida, Miami, Florida

Gary White Chief Executive Officer and Cofounder, Water.org, Kansas City, Missouri

Shira Winter, BA MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, Massachusetts

Denise Kelsey Wishner, MSN, RN Ethicist, Department of Veterans Affairs, Long Beach, California

Karen Anne Wolf, PhD, ANP-Bc, DFNAP Nurse Consultant, Oakland, California

Deborah von Zinkernagel Acting U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, Washington, DC ‡ Deceased

Preface

The genesis of this book occurred when the editors posed the following question, “Is there a need for a text on global nursing that encompasses the work of nursing, the complex issues that affect the health of the world’s people, and nursing’s contributions to interprofessional efforts to achieve global health?” So began the journey that has culminated in this text, Global Health Nursing in the 21st Century. When we set out to answer this question, we discovered a paucity of nursing texts related to global nursing and embraced the idea that the literature would be enriched by the contribution of this book. During our review of existing scholarly works, we discovered several contributions to the global health literature from the fields of public health, international health, and global health. However, most texts were written by experts from other disciplines and few explored the unique contributions of the nursing profession to the interprofessional landscape of global health. In retrospect, this observation should not have been unexpected. While it is widely understood that nurses represent the vast majority of the global health workforce, and that nurses and midwives play a critical role in health care delivery, their expertise is often overlooked or—at the least—undervalued. Indeed, nurses have been late in being invited to join other key stakeholders, such as health scientists, physicians, economists, public health professionals, and international development experts, in the discussions that shape global health. However, there is a growing recognition that nurses and midwives are essential to providing quality, people-centered care, and improving the cost effectiveness of that care. The World Health Organization (WHO) publication, Nursing and Midwifery Services: Strategic Directions 2011–2015 (2010), acknowledges nursing’s absence and strongly advocates that “…governments, civil society and professional associations must work together with educational institutions, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and a range of international and bilateral organizations to remedy the situation so that the input of nurses and midwives is actively sought and acknowledged” (p. 3). Likewise, Frenk et al. (2010) have shifted the paradigm of those educated in the health professions and have enlisted not only educators and universities, students and young health professionals, but also NGOs, international philanthropic organizations, and foundations to promote the reform needed for the health professions to address the health of the world’s people in the 21st century. These authors contend that both institutional and instructional reforms are needed to achieve a model transformative professional education. As they state: “The result will be more equitable and better performing health systems than at present, with consequent benefits for patients and populations everywhere

in our interdependent world” (p. 4). One of the hallmarks of Frenk et al.’s mandate—interdependence—requires a shift to interprofessional and transprofessional education, as it is well understood that collaboration and teamwork result in better patient outcomes. Along with the strategic directions recommended by the WHO (2013), Frenk et al.’s mandate strengthens the argument that nurses are integral members of the global health team. They suggest that past laudable efforts to reform the health professions to suit contemporary needs have “…mostly floundered, partly because of the so-called tribalism of the professions—that is, the tendency of the various professions to act in isolation from or even in competition with each other” (p. 1). Nurses worldwide must embrace and advocate for Frenk et al.’s vision that:

all health professionals in all countries should be educated to mobilize knowledge and to engage in critical reasoning and ethical conduct so that they are competent to participate in patient and populationcentred health systems as members of locally responsive and globally connected teams. (pp. 2–3)

To realize this vision, it is critical that nurses worldwide understand and strengthen their professional scope so that they can practice to the full extent of their education and training. This goal will make nurses more effective members of an interdisciplinary team and build what is required to address the comprehensive needs for population health globally.

The underlying assertion of Global Health Nursing in the 21st Century is that global health encompasses the health problems of both rich and poor countries and implies a shared responsibility for achieving health and eradicating inequities (Birn, Pallay, & Holtz, 2009). It takes into account the social, political, cultural, economic, and environmental factors—including climate change—that may impact health. We developed the text to account for this unique and critical conceptualization. The book comprises three units and includes contributions from nurses with global health expertise, as well as global health experts from other disciplines. It is structured to provide a layered understanding of the complexities surrounding global health.

Unit I offers an overview of the foundations of global health. This is the first global nursing text to include the emerging concept of climate justice and its relationship to climate change and environmental health consequences. Additional tenets that underlie global health and global nursing are explored. These include an analysis of the distinctions that relate to public health, international health, and global health; the ethical context of global health, human rights, and social justice; and the importance of interprofessional education to achieve global health and global health equity. Globalization and the significant impact on the health of people worldwide is discussed not only in Unit I, but also more broadly in several chapters throughout the book. Taken together, these tenets form the basis for understanding and undertaking effective bidirectional global health partnerships.

Unit II highlights issues of global health and the effects on the most poor and vulnerable worldwide—particularly women, children, and those living in areas of conflict. The physical and mental health sequelae related to violence that occur

both within and outside personal relationships and country-specific conflicts are explored. The likelihood that women and girls will experience negative health effects related to violence is also examined within the scope of their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS and their forced participation in sex trafficking. The impact of HIV/ AIDS and its detrimental effects on the nursing workforce in sub-Saharan Africa, which experiences a disproportionate burden of the disease, are also explored in this unit. Maternal mortality and childhood malnutrition are additional health risks experienced by women and children that are discussed in Unit II.

Finally, while much work toward achieving global health is underway and there have been notable accomplishments, Unit III addresses areas where efforts must be redoubled to achieve success. This unit focuses on seeking and implementing solutions necessary to realize this overarching goal. The work of critical stakeholders working within governmental organizations, NGOs, and foundations is described. Collectively, their efforts are centered on increasing access to primary health care; increasing access to services that would otherwise be unavailable (e.g., surgical services); improving clinical practice by expanding educational opportunities for both students and practicing nurses and midwives; and engaging interdisciplinary researchers in the discovery of viable solutions to these challenges. At the core of achieving global health—and the overarching goal of the text—is the understanding that many of the initiatives highlighted are strategies aimed at strengthening health systems and achieving global health equity. The goals are achievable in the 21st century and represent a contemporary human rights obligation.

We are proud of the development of Global Health Nursing in the 21st Century. The chapters provide nurses and those interested in nursing’s contribution to the field of global health, a comprehensive survey of the range of issues. This knowledge is essential to understanding how to best influence the health and attainment of human rights for people worldwide. In closing, we offer a quote from Nelson Mandela, who espoused the issues of equity during his journey toward achieving justice for the people of South Africa and, more broadly, the world. His vision embraced equity in all aspects of life and has relevance for social justice, human rights, and global health.

Let there be justice for all. Let there be peace for all. Let there be work, bread, water, and salt for all. Let each know that, for each, the body, the mind, and the soul have been freed to fulfill themselves. The sun shall never set on so glorious a human achievement.

—Nelson R. Mandela

Statement of the President of the African National Congress at his inauguration as president of the Democratic Republic of South Africa, 1994

Suellen Breakey

Inge B. Corless

Nancy L. Meedzan

Patrice K. Nicholas

referenCes

Birn, A.E., Pillay, Y., & Holtz, T.H. (2009). Textbook of international health: Global health in a dynamic world. (3rd ed). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., … Zurayk, H. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet, 376, 1923–1958. Retrieved from http://www .healthprofessionals21.org/docs/HealthProfNewCent.pdf

World Health Organization. (2010). Strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery services (SDNM) 2011–2015. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. Retrieved from http:// www.who.int/hrh/resources/nmsd/en

Share

Global Health Nursing in the 21st Century

Global Health and Global Nursing

Patrice K. Nicholas and Suellen Breakey

WHat is Global HEaltH?

The burgeoning discipline of global health has increased in scope and complexity since the beginning of the new century. Despite these advances, Farmer, Kleinman, Kim, and Basilico (2013) contend that identifying global health as a discipline is premature. Rather, they view global health as a collection of problems that affect the health of the world’s people. Transformation from professional commitment to a unique discipline will require interdisciplinary efforts aimed at rigorously analyzing and solving the areas of concern for global health (Farmer et al., 2013). Global health emerged as a new concept arising from the earlier disciplines of public health and international health. Koplan et al. (2009), writing on behalf of the Consortium of Universities for Global Health Executive Board, note that:

Global health is fashionable. It provokes a great deal of media, student, and faculty interest, has driven the establishment or restructuring of several academic programs, is supported by governments as a crucial component of foreign policy [Institute of Medicine, 2008] and has become a major philanthropic target. (p. 1993)

These authors advocate for the adoption of a common definition of global health that encompasses a broad range of health challenges (for example, maternal child health, infectious diseases, noncommunicable and chronic diseases, and environmental health issues). They argue that establishing and agreeing on a common definition is critical to prioritizing and advancing the work of global health. The authors also discuss the scope of global health in terms of both the problems to be addressed and its geographical reach. Koplan et al. contend that global health should not be restricted to health issues that cross international borders. Moreover, they suggest that:

Global refers to any health issue that concerns many countries or is affected by transnational determinants, such as climate change or urbanization, or solutions, such as polio eradication. Epidemic infectious diseases such as dengue, influenza A (H5N1), and HIV

infection are clearly global. But global health should also address tobacco control, micronutrient deficiencies, obesity, injury prevention, migrant-worker health, and migration of health workers. The global in global health refers to the scope of problems, not their location. (p. 1994)

Based on this rationale, Koplan et al. (2009) propose the following definition: “Global health is an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving health equity in health for all people worldwide” (p. 1995).

Global health—like public health but unlike international health—must address domestic health disparities as well as cross-border issues (Farmer et al., 2013; Koplan et al., 2009). As noted by Farmer et al. (2013), global health’s antecedent term was international health, which emphasized the nation-state as the important focus. In their view, global health includes the role of nonstate institutions, including international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), private philanthropies, and community-based organizations. Koplan et al. (2009) recommend that global health must also address the “training and distribution of the health-care workforce in a manner that goes beyond the capacity-building interest of public health” (p. 1994). They offer a view on global health that is relevant for global medicine and nursing:

Global health can be thought of as a notion (as in the current state of global health), an objective (a world of healthy people which is a condition of global health) or a mix of scholarship, research, and clinical practice (with many questions arising as well as issues and competencies that must be addressed). (p. 1993)

Critical to a robust definition of global health, they argue, is agreeing on the goals, strategies, approaches, and skills needed by health professionals to achieve global health outcomes. Birn, Pillay, and Holtz (2009) suggest that while international health primarily focused on health issues in underdeveloped countries and the efforts by industrialized countries and international agencies to address these problems, to preserve their self-interests, the concept of global health reconceptualizes and depoliticizes international health to rise above the past ideological underpinnings of colonialism. This shift is also embedded in the recent Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2009) report on The U.S. Commitment to Global Health: Recommendations for the Public and Private Sectors. This report resulted from the convening of the Committee on the U.S. Commitment to Global Health to investigate the U.S. commitment to global health and articulate a vision for U.S. involvement in global health issues. The report identified five areas for action:

1. Scale-up of existing interventions to achieve significant health gains

2. Generate and share knowledge to address health problems prevalent in low- and middle-income countries

3. Invest in people, institutions, and capacity building with global partners

4. Increase U.S. financial commitments to global health

5. Set the example of engaging in respectful partnerships (IOM, 2009, p. 1)

Finally, this report notes that: “The United States has the responsibility as a global citizen, and an opportunity as a global leader, to contribute to improved health around the world. U.S. leadership in global health is a reflection of American values: generosity, compassion, optimism, and a wish to share the fruits of our technological advances with others around the world” (p. 3). This responsibility and commitment are also embraced by countries around the world. However, it is important to note that some argue that one of the negative aspects related to global health is that the United States attempts to assert unilateralism and dominate the international health agenda to meet its own national interests at the expense of international interests (Birn et al., 2009). Other industrialized countries may also need to closely examine the motivations behind their efforts.

EMErGEnCE oF tHE FiEld oF Global HEaltH

The field of global health emerged from the 19th-century work in public health in the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States. Public health was influenced by the growing understanding of communicable diseases as well as the ability to gather data; to focus on population health rather than individuals; social justice and equity; and an emphasis on prevention rather than curative care (Koplan et al., 2009). Further, the IOM (1988) embraced the importance of public health in The Future of Public Health report, which formalized the mission, goals, and organizational framework for public health and defined the mission as “fulfilling society’s interest in assuring conditions in which people can be healthy” (IOM, 1988), thus setting the stage to move public health to a global arena for societies worldwide. Fried et al. (2010) suggest that “public health has unique, and critically important, roles in creating global health and well-being” (p. S7 and original); further, they note that public health principles are foundational to global health approaches. Fried et al. also support the following key principles for global health leadership.

• Core values that include commitment to the public good and health as a human right

• A frame of reference that prevention is cost-effective and critical to accomplishing health for all

• Health promotion accomplished through a combined platform that engages science, evidence, experience, matching solutions to needs, shared knowledge, and a commitment to equity that is translated into practice

• Health systems and global public health leadership that includes a commitment to the most effective, evidence-based approaches to prevention and care in integrated health systems and with an approach to continual learning

• A continuum of prevention, treatment, and care (Fried et al., 2010, p. S8)

Fried et al.’s focus on global health also espouses a critical understanding of how population health is changing globally and that health professionals will confront old and new public health challenges in the years from 2030 to 2050 that include “the health challenges related to longevity and aging; chronic diseases (noncommunicable and communicable); the physical environment and climate change; the built environment and urbanization; disasters and conflicts shifting food sources and water and food security; population migration; and disparities and vulnerable populations” (Fried et al., 2010, p. S9). Similar to Koplan et al. (2009) and their call for a consistent definition of global health, Fried et al. suggest that clarity is needed in finding solutions to these health challenges. Their views are shared by Farmer et al. (2013) in that they propose engaging in science, technology, and practice for success in global health leadership.

International health emerged within the science of public health. Merson, Black, and Mills (2006) describe a framework that applies the principles of public health to challenges that affect low- and middle-income countries. However, this framework does not address the bidirectional issues that occur across countries or consider the fact that international health should also address the health needs of people in all countries. The Global Health Education Consortium (2009) explored the concepts of global versus international health and suggested that international health is more focused on health systems, policies, and practices with a lens on differences between countries rather than common health challenges shared across countries. Koplan et al. (2009) discuss the overlap of public health, international health, and global health. Specifically, they discuss the three areas as sharing certain characteristics that include “priority on a population-based and preventive focus; concentration on poorer, vulnerable, and underserved populations; multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches; emphasis on health as a public good and the importance of systems and structures; and the participation of several stakeholders” (pp. 1993–1994). Most notably, they argue that global health is highly interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary across the health professions and extends to other disciplines and the unique and overlapping contributions that may occur. This aspect of global health further extends the scope and impact of the work from domestic health issues to crossing borders and continents, the distribution and competencies of health professionals, and capacity building and policy issues that are fundamental to the health of the world’s people. Koplan and colleagues’ definition of global health, as described previously, encompasses the knowledge, resources, and impact of societies in addressing health challenges. They note that global health engages in transnational solutions and engages many disciplines in promoting the goals of health. The profession of nursing, as the largest number of global health professionals worldwide, has a critical contribution to offer in global health.

tHE ContEXt oF GlobaliZation and EMErGEnCE oF 21st-CEntUrY

The World Health Organization (WHO, 1946) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease

or infirmity” (p. 100). This definition is universally accepted as the gold standard for health worldwide. Nurses and other health professionals play a key role in addressing the health of those living in our global village. There is both a professional duty as well as an ethical obligation for the nursing profession to advance this enduring vision of health for the world’s people.

One of the most significant events that launched the focus on global health and subsequently global medicine and global nursing efforts was the Alma Ata conference. This conference was held in 1978 at the International Conference on Primary Health Care at Alma Ata, Kazakhstan, and was cosponsored by WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). A major achievement of the conference was the adoption of a resolution, the Declaration of Alma-Ata (WHO, 1978), aimed at attaining Health for All by the Year 2000; subsequently, Health for All in the 21st Century (Health 21) was developed.

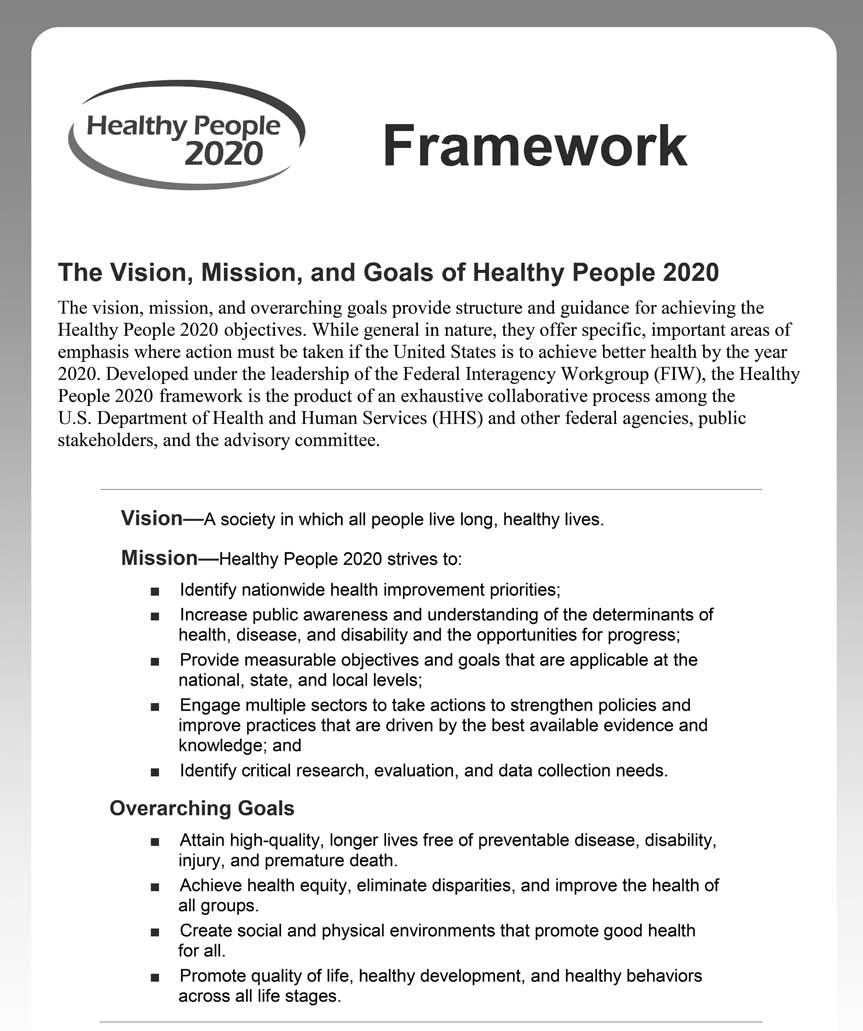

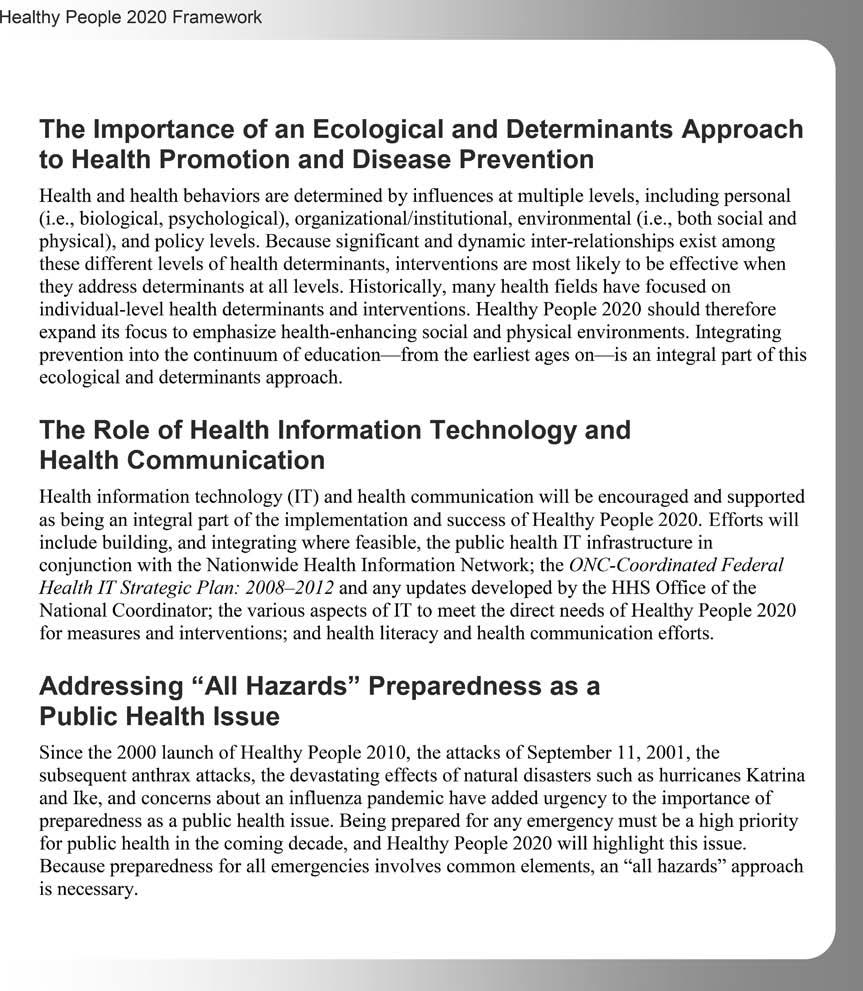

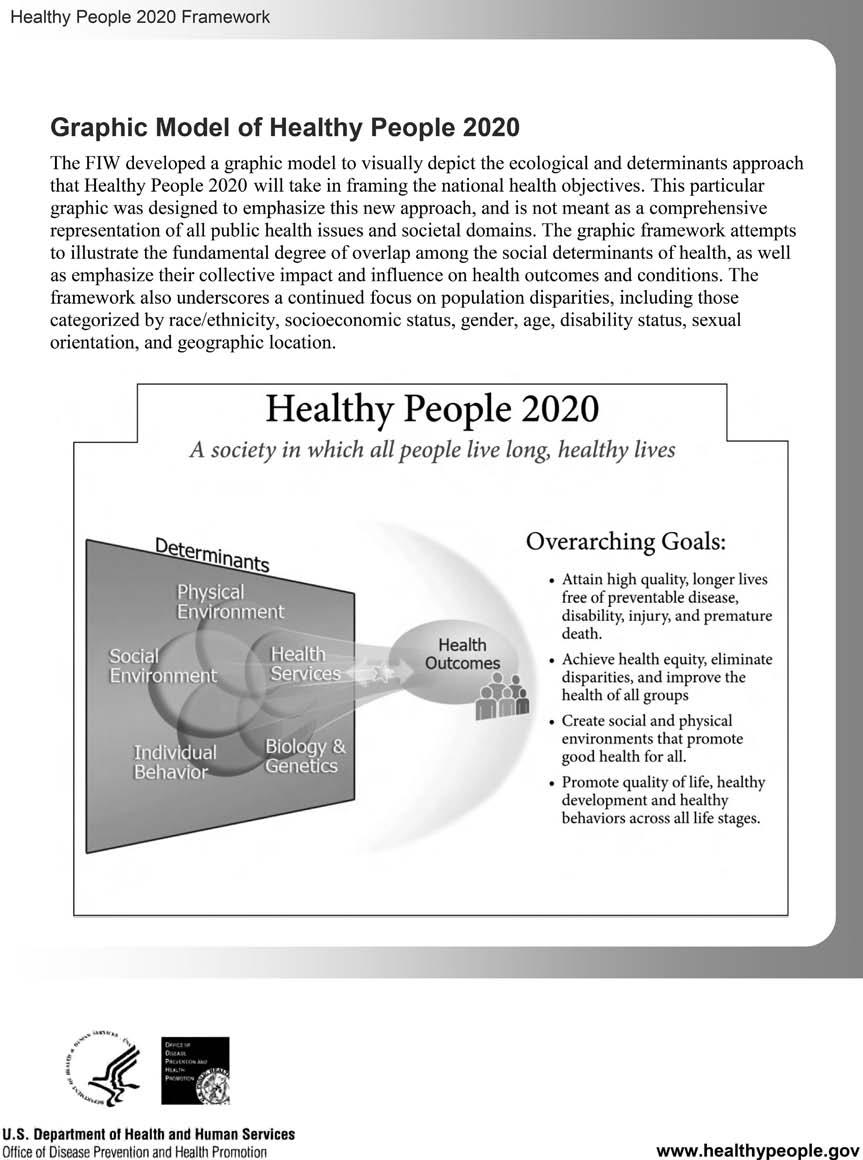

The U.S. Healthy People 2020 objectives are the U.S.-specific recommendations that address the important health goals similar to the goals of HFA 21. In 1990, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services offered the first version of Healthy People 2000, with subsequent recommendations offered in 2010 and 2020. These reports address health promotion, health protection, and preventive services. The goals of Healthy People 2020 are shown in Figure 1.1.

applying a Framework for Global Health and Global nursing

Our world is becoming increasingly global. As Crigger, Brannigan, and Baird (2006) note: “Globalization is reshaping the world and its people. Nursing, likewise, is in the process of expanding its worldview to one that accommodates global care” (p. 15). In their paper on compassionate nursing professionals as good citizens of the world, they emphasize the importance of two key concepts—world citizenship and the nursing role as compassionate professional. World citizenship is a concept first developed by Nussbaum (1997) in her text Cultivating Humanity. Crigger et al. (2006) view nursing as integrally linked with globalization and world citizenship because of the profession’s altruistic focus, engagement with social justice, and ethical framework. The second concept of compassionate professional is aimed at nurturing partnerships of mutual respect.

Austin (2001) poses a fundamental question related to the concept of compassionate professional: “What does a shift to a global frame of reference mean to the ethical practice of the 11 million nurses [now over 19.3 million] providing care around the world?” (p. 1). She contends that the global context of nursing is linked to the advancement of technology and transportation. She describes the international focus of nursing since 1870 and the work of nursing in the International Red Cross as early examples of nursing’s global influence. Austin’s (2001) focus is on three key ethical issues: the influence of biotechnological advancement on the business industry, the demands of equity and justice in global resource allocation, and the importance of an ethic that respects diverse cultures and values.

FIGURE 1.1 Vision, mission, and goals of Healthy People 2020.

Most importantly, health challenges such as epidemics and infectious and chronic diseases, as well as human distress caused by ethnic conflicts, wars, famine, and lack of access to safe water, are drivers for the expanding role of nursing to engage in our global world. Most troubling is the fact that globalization is increasing the marginalization and poverty of the world’s most vulnerable. Austin (2001)

notes, “The shocking fact is that, according to the 1996 United Nations Human Development Report (1996), 358 people have more wealth than the combined incomes of 45% of the world population (i.e., 358 rich people own more than 2.3 billion poor people)” (p. 7). The trend that a very small number of people own the majority of the world’s wealth continues today. Poverty is directly associated with

FIGURE 1.1 Vision, mission, and goals of Healthy People 2020. (continued )

1.1 Vision, mission, and goals of Healthy People 2020. (continued )

FIGURE

poorer health outcomes. The resulting myriad acute and chronic health problems are frequently addressed in wealthier countries—although less effectively for the poor. However, poorer communities continue to struggle. Also, many of these communicable and chronic diseases such as measles, mumps, rubella, polio, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H1N1, and hepatitis, as well as HIV and malaria, are endemic in poorer countries.

Austin (2001) also discusses the shift of the nursing profession toward global engagement, as well as societal actions and the role of organizations, both nursing and world health organizations. Perhaps the most powerful question that she poses is the following: “Should we be tinkering with genes when, for many parts of the world, the most acute biotechnological problem is a safe water supply?” (p. 7). There are numerous issues that affect the health of the world’s people and are global mandates for the nursing profession to address. These include lack of access to water, emerging infectious diseases, chronic illnesses, lack of access to natural resources, war and conflict, and climate change. As Nelson (2011) suggests: “Climate change poses challenges on a new scale for humanity, particularly for the populations of lower income countries” (p. vi). Further, women, children, and the elderly are noted to have unique vulnerabilities with respect to climate change—particularly related to “existing power inequalities and social norms, [thus] the impacts of climate change will not be felt evenly, but will be overlaid onto existing patterns of vulnerability within rural and urban populations and communities—and may make patterns of inequality more pronounced” (Nelson, 2011, p. vii).

Upvall, Leffers, and Mitchell (2014) address the intersection of international health, public health, and global nursing and define global nursing as “individual and/or population-centered care addressing social determinants of health with a spirit of cultural humility, deliberation, and reflection in true partnership with communities and other health care providers” (p. 6). Their conceptual model for partnership and sustainability for global nursing reflects the key components, the partnering process, and goal of sustainability of interventions in global efforts. Their model includes partner factors for global nurses and host partner nurses, which enriches the global projects. Mutual goal setting, collaboration, empowering, and capacity building are infused in the model since global nursing efforts should be bidirectional rather than U.S. centric.

This section provides an overview of several global organizations that influence the health of the world’s people, including the United Nations (UN), WHO, the World Bank, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, and nursing organizations such as the International Council of Nurses, which advances the work of nursing and the health needs of our global population. Although not an exhaustive review of the many organizations that contribute to global health, this section offers an overview of the contributions of global health organizations.

Global HEaltH orGaniZations

Global or international organizations are generally multilateral, bilateral, or nongovernmental in nature. Multilateral organizations cross several countries and borders and receive funding from multiple organizations and sources. Examples of these organizations include the UN, WHO, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), and the World Bank. Bilateral global organizations address country-specific needs through a single agency. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is an example of a bilateral global organization. NGOs or private voluntary organizations (PVO) are a third type of organization that addresses pressing global health needs. Examples of NGOs include Partners In Health (PIH), Project Hope, Doctors Without Borders, Oxfam, and the International Red Cross.

WHO was established in 1946 to address the international health needs and the comprehensive organization required of a health agency to address the scope of the world’s health problems and the design of initiatives aimed at mitigating these problems. The organization is led by a director general and five assistant directors general with three major divisions: the World Health Assembly to address policy initiatives; an Executive Board that links the Assembly and the Secretariat; and the Secretariat, which supports the implementation of policy work and strategic initiatives with day-to-day operations. It is arguably the most important global organization to address the health of people worldwide. However, van de Pas and von Schaik (2013) suggest that there has been “a progressive erosion of the democratic space [that] appears as one of the emerging challenges in global health today” (p. 195), and that there are key challenges that WHO faces due to the power and money of which key decision makers have control. Hoffman and Rottingen (2013) argue that WHO has not been able to fully achieve its mission in

serving as the world’s pre-eminent public health authority and intergovernmental platform for global health . . . this forces [WHO] staff to walk uncomfortably along many fine lines: advising but never directing; guiding but never governing; leading but never advocating; evaluating but never judging. The result is mediocrity on both fronts. Instead, WHO should be split in two—separating its technical and political stewardship into separate entities. (p. 188)

Such a division, as Hoffman and Rottingen suggest, may strengthen WHO’s political decision making and the organization’s ability to secure independent scientific advice. The profession of nursing could benefit directly from this proposal if WHO’s role in global nursing is strengthened and there is an emergence of strong nursing leadership within the organization and in countries worldwide.

As a global organization, in 2000 the UN promulgated the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in response to the 21st-century needs of the world’s population. These goals look to address eight important health and development goals that aim to be achieved by 2020. The eight goals are

Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education

Goal 3: Promote gender equality and empower women

Goal 4: Reduce child mortality

Goal 5: Improve maternal health

Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability

Goal 8: Global partnership for development (UN, n.d.)

We present examples of successful global programs that address achievement of the UN MDGs in Table 1.1.

The UN has other initiatives that address global health issues, including UNICEF and global human rights initiatives. UNICEF was formed after World War II to address the health challenges of children worldwide.

TablE 1.1 Examples of Millennium development Goal (MdG) programs in Global locations

1 Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

2 Achieve universal primary education

3 Promote gender equality and empower women

4 Reduce child mortality

• Halve the proportion of people whose income is less than $1/day

• Full employment and decent work for all

• Halve the proportion of people suffering from hunger

• Ensure that children are able to complete primary schooling

• Eliminate gender disparity in education

Yemen: Since 2007, the World Food Programme’s Food for Girls’ Education Program gives wheat and vegetable oil to families who send their girls to school.

5 Improve maternal health

• Reduce the under-5 mortality rate by two thirds

Guatemala: Since 2004, Abriendo Oportunidades has helped more than 4,000 girls from isolated Mayan communities build self-esteem and develop literacy.

Rwanda: UN Women is working with 15 cooperatives to teach women budgeting skills, and to encourage male farmers to include women in making financial and agricultural decisions.

Nigeria: Saving One Million Lives campaign, launched by the Nigerian government in 2012, expands access to health services by providing bed nets, supplying equipment to reduce mother–child HIV transmission, and providing health workers with telephones.

• Reduce maternal mortality ratio by three fourths

• Universal access to reproductive health

India: UNICEF and its partners are working to provide conditional cash transfers to women who deliver in health facilities to encourage them to access appropriate medical care at time of delivery.

(continued )