Pilar Garcés-Conejos Blitvich

ElementsinPragmatics

editedby

JonathanCulpeper

LancasterUniversity,UK

MichaelHaugh UniversityofQueensland,Australia

PRAGMATICS,(IM)

POLITENESS,AND

INTERGROUP COMMUNICATION

AMultilayered,DiscursiveAnalysis of CancelCulture

PilarGarcés-ConejosBlitvich

TheUniversityofNorthCarolinaatCharlotte

ShaftesburyRoad,CambridgeCB28EA,UnitedKingdom OneLibertyPlaza,20thFloor,NewYork,NY10006,USA 477WilliamstownRoad,PortMelbourne,VIC3207,Australia

314–321,3rdFloor,Plot3,SplendorForum,JasolaDistrictCentre, NewDelhi – 110025,India

103PenangRoad,#05–06/07,VisioncrestCommercial,Singapore238467

CambridgeUniversityPressispartofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment, adepartmentoftheUniversityofCambridge.

WesharetheUniversity’smissiontocontributetosocietythroughthepursuitof education,learningandresearchatthehighestinternationallevelsofexcellence.

www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle: www.cambridge.org/9781009494830

DOI: 10.1017/9781009184373

©PilarGarcés-ConejosBlitvich2024

Thispublicationisincopyright.Subjecttostatutoryexceptionandtotheprovisions ofrelevantcollectivelicensingagreements,noreproductionofanypartmaytake placewithoutthewrittenpermissionofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment. Whencitingthiswork,pleaseincludeareferencetotheDOI10.1017/9781009184373

Firstpublished2024

AcataloguerecordforthispublicationisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary.

ISBN978-1-009-49483-0Hardback

ISBN978-1-009-18438-0Paperback

ISSN2633-6464(online)

ISSN2633-6456(print)

CambridgeUniversityPress&Assessmenthasnoresponsibilityforthepersistence oraccuracyofURLsforexternalorthird-partyinternetwebsitesreferredtointhis publicationanddoesnotguaranteethatanycontentonsuchwebsitesis,orwill remain,accurateorappropriate.

Pragmatics,(Im)politeness,andIntergroup Communication

AMultilayered,DiscursiveAnalysisof CancelCulture

ElementsinPragmatics

DOI:10.1017/9781009184373

Firstpublishedonline:January2024

PilarGarcés-ConejosBlitvich TheUniversityofNorthCarolinaatCharlotte

Authorforcorrespondence: PilarGarcés-ConejosBlitvich, pgblitvi@ charlotte.edu

Abstract: ThisElementarguesandpresentsthebasesforpragmatics/ (im)politenesstobecomeintergroup-orientedsoastobeableto considerinteractionsinwhichsocialidentitiesaresalientorare essentiallycollectiveinnature,suchasCancelCulture(CC).CCisaform ofostracisminvolvingthecollectivewithdrawalofsupportand concomitantgroupexclusionofindividualsperceivedashaving behavedinwaysconstruedasimmoralandthusdisplayingdisdainfor groupnormativity.Toanalyzethistypeofcollectivephenomenon, athree-layeredmodelthattacklesCCmanifestationsatthemacro, meso,andmicrolevelsisused.Resultsproblematizeextant conceptualizationsofCC-mostlyfocusedonthemacrolevel-and describeitasaBigCConversation,whosemeso-levelpracticesneedto beunderstoodasgenre-ecology,andwhereidentityreduction, im/politeness,andmoralemotionssynergiesarekeytounderstand groupentitativityandagency.

Keywords: Im/politeness,CancelCulture,Intergroupcommunication,Moral emotions,genres

©PilarGarcés-ConejosBlitvich2024

ISBNs:9781009494830(HB),9781009184380(PB),9781009184373(OC)

ISSNs:2633-6464(online),2633-6456(print)

1Introduction

ThisElement’smainargumentisthatpragmatics,morespecifically(im)politeness research,needstobemorecognizantofintergroupcommunication,understoodas thosecasesinwhichsocial – ratherthanindividual – identityissalient(Giles, 2012).Thethrustbehinditisthatthereseemtobemanycommunicativephenomenathatsimplycannotbeaccountedforininterpersonaltermsbutarecollectivein natureandshouldbeunderstoodbyrecoursetoagroup.Thisistrueofinteractions whenthoseinvolvedoccupypositionsaffordedtothembyarecognizedsocial identity – suchasemployer/employeeinacorporatemeetingorBlackLives Mattersupporterinademonstration.Further,therearecertainactionsthatcannot beperformedattheindividuallevelbecausetheyemanatefromthegroupand,as such,needtobecarriedoutbyit(oremissariesactingonitsbehalf).Amongthese, we findgroups’ reprisaltomembers’ breachingofsocialnorms.Socialnormsare, inthemselves,aquintessentialgroupphenomenon.Bydisplayingovert(oratleast perceived)disdainforgroupnorms,amembermaybe(intentionallyorperceived as)signalingthattheydonotconformtothegroup’sculturalpracticesandthusbe seenaspotentiallyharmfultogrouplife.Often,differenttypesofretributionfor infringementensuewhich,onoccasion,maybequitesevere,resultingingroup exclusionandostracism(Tomaselloetal.,2012).

Groupexclusionpracticesareattheheartofwhathasbecomeknownas cancelculture(CC),hereunderstoodasablankettermusedtorefertoamodern formofostracisminwhichsomeone(the cancelee)isthrustoutofsocialor professionalcirclesasaresultofbeing fired,deplatformedorboycottedby others,the cancelers.The cancelee isalsosubjectedtopublicshamingand censorshipandoftenfacesserious financial,andevenlegal,repercussionsfor havingengagedindifferenttypesofbehaviorperceivedasimmoral.Moralityis closelyconnectedtosocialnormsand,thus,togroupgoalsandcollective intentionality(Tomasello,2018).Whilethefactthat CC existsisnotcontroversial,whatvariessubstantiallyiswhetheritisseeneitheras(i)awaytokeep individualsaccountableandprovideavoicetotraditionallydisenfranchised groups(firstwave)or(ii)anunjustformofpunishmentandcensorshipthataims atundermining,amongothers,freedomofspeech(secondwave; Romano, 2021; Section4.2).Here,withouttakingastanceonwhetheritsgoalsare laudableorcensurable, cancelation isviewedasanintrinsicallyaggressive off/onlinesetofgrouppracticeswhosemaingoalsarepublicexposure,group exclusion,punishmentoftarget cancelees, andsocialregulation. CC-associated practicescanthusbecategorizedasatypeof reactiveaggression (Allen& Anderson,2017)sincetheyinvolveretaliationtoperceivedoffensewithfurther offense(Garcés-ConejosBlitvich,2022b).Therefore,thisElementis firmly

anchoredinthesubfieldofpragmaticsthatanalyzesunderstandingsof(im) politenessandlanguageaggressionandconflict(Culpeper,2011).

Byfocusingontheirinterconnections,thisElementaimsatadvancingour knowledgeofintergroupcommunication,ontheonehand,andof CC,onthe other.Withveryfewexceptions(Bouvier,2020;Garcés-ConejosBlitvich, 2021,2022a,2022b; Haugh,2022), CC analyseshavetakenamacro-level approachand,asaresult,mayhavepaintedthissocialphenomenonwitha thickbrush,manyofitsidiosyncrasiesglossedover(Garcés-ConejosBlitvich, 2021).Indeed,somearecallingfor “qualitativeaccountsofthespecificpracticesandinteractionaldynamicsatplay” andamoreethnographicapproachto thesephenomena(Ng,2020:623).

Bytakingadiscursivepragmaticsapproachtothedata(Garcés-Conejos Blitvich2010c,2013; Garcés-ConejosBlitvich&Sifianou,2019)thatinvolves macro/meso/micro-levelanalyses,thisElementscrutinizesthecomplexitiesof threecasestudiesof cancelation involvingthreeAmericanwomenfromdifferentwalksoflife:CongresswomanLizCheney,comedianEllenDegeneres,and sportscommentatorRachelNichols.1 Thus,thestudyhasaUSAfocus. Importantly,althoughCCisclaimedtobeexperiencedelsewhere(Velasco, 2020),itsoriginsarequintessentiallyAmerican(see Section4).Tocarryoutthe study, Fairclough’s(2003) discourseinsocialpracticemodelistakenasa startingpoint,sinceitnicelyincorporatesthesethreelevelsofsociological inquiry:discourses(macro-levelunits)a reinstantiatedingenres(meso-level units),whichare,inturnrealizedatthemicro-level(viadifferenttypesof linguistic – andothersemiotic – [inter]actions)manyofwhichareentextualized,suchastheuser-generatedcommentsinthecorpus.Morespeci fi cally, CC ,atthemacro-level,isunderstoodasaBigCConversation( Gee,2014 ) andwillbedistinguishedfromtheprocessesinvolvedinthenow recognizable ( Blommaertetal.,2018 ; Gar fi nkel,2002 )practiceof cancelation ( SaintLouis,2021 )wherebyindividualsgetcanceled,whichisproperlyrealizedat themeso-levelviaacomplexgenreecology(Spinuzzi&Zachy,2000)andat themicro-levelbygenre-speci fi cconstrainedinteractions.Althoughresearch ( Saint-Louis,2021 )insightfullypointedtotheconceptualdifferences between CC and cancelation ,nodiscourse-basedanalysistodatehasoffered adetaileddescriptionofthemeso-levelpracticesdeployedtocarryout cancelation .Fromthisperspective,thisElementcontributestoadvancing discursivepragmatics/( im)politeness,asthese fi eldshavetraditionallypaid moreattentiontothemacroandmicro-levels.

1 Threemiddleaged/whitewomenwerechosenastargetstohomogenizethesample.However,this Elementlooksat CC fromanideologicalratherthangenderedperspective.

Regardingthemicro-level,interactionsthatrealizethegenrecommonly knownasonlinecomments,asizeableanalyticcorpusextractedfromthe CC Corpus,werequalitativelyscrutinizedtogaininsightsintointergroupcommunication.Although,asmentioned, CC isnotjustanonlinephenomenon,its onlinemanifestationsdocarrysignificantweightasinitiatorsandcontinuators of cancelation.Inaddition,theyprovideprimesitesfortheanalysisofgroup behaviorandintergroupcommunication.Inpart,thishastodowiththeanonymityaffordedbyonlineplatforms:anonymityenhancessocialidentity (Reicheretal.,1995).Further,digitalcommunicationallowsforthecreation ofamultiplicityofdiversegroups(fromvery thick tovery light,Blommaert, 2017a)andaffordsthenecessary “scenes,” onlinefreespaces(Fine,2012; Rao &Dutta,2012),forthesegroupstoassembleandcarryoutdifferentactions relatedtothegroup’sgoals.Thesegoalsarecloselytiedtotheirclaimedsocial identity(Fine,2012)andcollectiveintentionality(Jankovic&Ludwig,2017). Inthisrespect, CC isrelatedtowhathasbeendescribedas light groups,astaple ofonlinecommunication.Thepresentstudyalsocontributestounderstanding ofhowsuchgroupsbecomeagents(Tuomela,2013).

Concerning CC,thisElementhelpstodispelsomecommonlyheldbeliefs: suchasthat CC isentirelyanonlinephenomenonorthatitisunivocalinits direction:ledby woke mobsthatseekthesamegoal.Indeed,conservativesalso engageinatypeofstraightforward cancelation typicallyassociatedwiththe firstwaveof CC (asCheney’scaseillustrates).Resultsconfirmthat CC has evolvedsinceitsinceptionandsupportclaimsofasecondwave(Romano, 2021)inwhichthe ultimatecanceller – thatis,corporations,politicalparties, andsoon – ratherthanthe cancelees themselves,becomesthetarget.However, thissecondwaveisnotnecessarilyconservative-led.Athirdtypeof cancelation (notassociatedwithaspecificpoliticalpersuasion)targetsboththe cancelee and the ultimatecanceler.Further,fromtheanalysisofcomplexgenreecologiesdeployedtocarryout cancelations, CC emergesasprimeexampleofthe off/onlinenexusofpost-digitalsocieties(Blommaert,2019)andwillbehere seenfromtheperspectiveofaugmentedrealitywhichunderstandsthedigital andthephysicalashighlyenmeshed(Jurgenson,2011).

Additionally,althoughgroupphenomenasuchassocialexclusion/ostracism havereceivedconsiderableattention(Foucault,1996; Hoover&Milner,1998; Peters&Beasley,2014)forthemostpart,littleisknownabouthowthese exclusionarypracticesarecarriedoutatthemicro-level.Significantly,theserituals areapproachedherespatially,fromageo-semioticsperspective.Following Goffman(1963b),ScollonandWongScollon(2003)and Blommaert(2013), off/onlinespaceisunderstoodasbeingregulativeand,thus,historicalandpolitical.Further,applyingthetenetsofemotionalgeographies(Davidsonetal.,2005),

theonlinefreespaceshereunderscrutinyareseenastransforminginto “othercondemning/suffering” (Haidt,2003)emotionalspaceswherebehaviorconsideredantinormative(i.e.,triggersthatset cancelation inmotion)is,inturn,un/ civillyevaluated.Furthermore,saidspacesbecomemoralizingsitesaboutoffline normativitywherethedarksideofmoralityemergesfullforce(Monroe&Ashby Plant,2019; Rempalaetal.,2020).Relatedly,resultsrevealacloseconnection betweenmorality,sharedemotions,andaggressiveretaliationvia(im)politeness.

ThisElementisorganizedasfollows: Section2 discussesthehurdlestoand proposesamodelforapragmatics/(im)politenessofintergroupcommunication. Section3 payscloseattentiontothemeso-level,thelevelofgroups,anddiscusses howonlinespacesfacilitatetheformationoflightgroupings. Section4 beginsthe empiricalpartoftheElementbytacklingthemacro-levelexplorationof CC and includesanoverviewofthethreecasestudiesthatareprobedinthemeso/microlevelsofanalysis,thefociof Sections5 and 6,respectively.Foreaseofreading,a methodssectionrelatedtoeachdiscursivelevelstartsthededicatedsections.In Section7,analysisdrivenresponsesareprovidedtotheguidingresearchquestions(Section3.1)andfuturevenuesforfurtherresearcharediscussed.

2APragmaticsofIntergroupCommunication

Pragmatics,bothutteranceanddiscoursebased,hasmostlyfocusedoninterpersonalcommunication(Haughetal.,2013; Locher&Graham,2010),inwhichthe personal/individualidentityoftheinterlocutorsismostsalient.Personalidentity referstoself-categorieswhichdefinetheindividualasauniqueperson,regarding theirindividualdifferencesfromother(ingroup)members.Foritspart,intergroup communicationwasdefinedas “interactionswhereparticipants’ groupidentities –theirclans,cliques,unions,generations,families,andsoon – almostentirely dictatetheconversationaldynamics;speakers’ idiosyncraticcharacteristicshere wouldbealmostimmaterial” (Giles,2012:3).Theboundariesbetweenpersonal andsocialidentityareporous:group/socialidentityistheportionofanindividual’s self-conceptderivedfromperceivedmembershipinarelevantsocialgroup (Tajfel&Turner,1979/2006).Despitepragmaticsscholarshipleaningtoward theformer,thelatterplaysamajor(someargueevenmorehighlypervasive) roleincommunication.As Giles(2012:3)noted, “HenriTajfelhadalways argued ... thatatleast70%ofso-calledinterpersonalinteractionswereactually highlyintergroupinnature thiscouldperhapseventurntobeanunderestimate.”

Sayingthatpragmaticshasmostlyfocusedoninterpersonalcommunication doesnotmeanthattherearenostudiesinwhichintergroupcommunication figuresprominently.Forexample,within(im)politenessresearch,therehas beensubstantialworkdoneoncommunicationinprofessionalgenres:service

encounters(MárquezReiter&Bou-Franch,2017),healthencounters(Locher& Schnurr,2017);courtroomdiscourse(Lakoff,1988),politicaldiscourse(Harris, 2001)andongender(Holmes,2013; Lakoff,1975; Mills,2003),allinstancesof socialidentitybeingsalient.Thesamecouldbesaidaboutintercultural/crosscultural/contrastivepragmaticsthatfocusonnational,ethnic,orlanguage/culture groups(Blum-Kulka,House&Kasper,1989; Márquez-Reiter&Placencia,2005; Sifianou,1999).Toalesserdegree,linkshavebeenestablishedbetweenother socialidentitiesand(im)politeness.Forinstance,religion(Ariff,2012),age (Bella,2009),socialclass(Salmani-Nodoushan,2007),andrace(Morgan,2010).

However,intergroupcommunicationhasoftenbeenapproachedfromaninterpersonalperspectiveandtheconstraintsplacedoncommunicationbyoccurring intergrouphave,inmyview,notbeensufficientlyexplored.Thismaybedue,as Blommaert(2017a)discussesinhisreviewofDurkheim’sideas,tothedominance ofRationalChoiceTheory,aspin-offofMethodologicalIndividualism. MethodologicalIndividualismarguesthateveryhumanactivitycanbereduced toindividuallevelsofsubjectivityinaction(suchasinterests,intentions,motives, concerns,decisions)evenifitiseminentlysocial.RationalChoiceisdrivenbythe maximizationofindividualprofit(materialandsymbolic)andproceedsbymeans ofcalculatedintentionalandrationaldecisionsbyindividuals.

ItisnotdifficulttotracestrongparallelsbetweenthetenetsofMethodological Individualismandthoseoffoundationalmodelsandtheoriesofpragmatics,such as BrownandLevinson’s(1987) politeness,andtheirrationalModelPerson, Leech’s(1983)characterizationofpragmaticsaseminentlystrategicandthus rhetorical,ameanstoanend,andthespeaker-centerednessthatdominatesSpeech ActTheory.Further,Blommaert(2017a:17)pointsoutthat,initsmostradical versionsofRationalChoice, “peopleneverseemtocommunicateortocommunicateonlyindyadiclogicaldialogue.” Dyadiccommunicationhasalsobeena stapleinpragmatics,perhapsanotherhurdletotacklinggenresthatinvolve collectiveengagementandpolylogalinteraction(Bou-Franch&GarcésConejosBlitvich,2014).Allinall,withsuchastrongbiastowardindividualism, ithasnotbeeneasytoconceptualizethe “socialfact,” thatis,thecollectivein Durkheim’sterms,inpragmaticterms.

Inthenextthreesections,Iproposeaframeworktoovercomepotentialhurdles toagrouppragmatics/(im)politeness.Althoughitmostlyfocuseson(im)politeness,duetothisElement’srelationalemphasis,itcanbeextendedtoother pragmaticphenomena(suchasexplicated/implicatedmeaningwhichisheavily influencedbythemeso-levelandindividual/socialidentityclaims/attribution).At thecoreofmyproposalliestherecommendationtomakepragmaticsdiscursive initsorientation(see Garcés-ConejosBlitvich2010c,2013; Garcés-Conejos Blitvich&Sifianou,2019)andtherelatedneedtoexplorethemeso-levelof

sociologicalenquiry(muchlessresearchedthanthemacroandmicro-levelsin pragmaticsscholarship).Themeso-levelhappenstobethelevelofpractices,and thusofgroups,and,therefore,essentialtounderstandcollectiveactionand intentionality(keycomponentsoftheproposedframework).Inthisrespect, CulpeperandHaugh(2021:323)arguethat “meso-levelconceptsdohavean importantroletoplayinteasingouttherolecontextplaysinassessmentsof(im) politeness.Indeed,wesuspectthatitisatthemeso-levelthatthemostimportant workintheorizing(im)politenessismostlikelytocontinue.” Inaddition,especiallyforresearchon(im)politeness,adiscursivepragmaticsopensthedoorto deeperconsiderationsofidentityinrelationtoface,centralconstructsof(im) politenessmodels,asidentityisatthecoreofdiscourses.

2.1OvercomingPotentialHurdlestoaPragmatics(im)politeness ofGroups

2.1.1FaceandIdentity

Thelackofexplorationofintergroupcommunicationwithinpragmatics/(im) politenessmaybeduetoseveralfactors.Oneofthembeingthat,ingeneral, mostresearchhasnotnecessarilyfocusedonidentitybuton face.Face,the inspirationbehindthecoreconceptin BrownandLevinson’s(1987) framework, wasdefinedbyGoffmanas “thepositivesocialvalueapersoneffectivelyclaims forhimselfbythelineothersassumehehastakenduringaparticularcontact. Faceisanimageofselfdelineatedintermsofapprovedsocialattributes” (1955/ 1967:5).As Garcés-ConejosBlitvich(2013) argued,Goffmanconceptualized faceasbeingtiedtoaline(arole,anidentity).2 However,BrownandLevinson’s construaloffacealtereditsessence,astheyseparatedfacefrom line and presenteditasaprimarilycognitiveconstructpossessedbyarational Model Person.Thisfocusonindividualismisoneofthereasonswhytheirpoliteness theorydrewsomeoftheearliestcritiquesfromscholarsfromcollectivismorientedcultures(Matsumoto,1988; Nwoye,1992)andtheargumentbehind takingintoconsiderationdiscernmentalongwithstrategicpoliteness(Ide,1989). Ithasalsobeenadeterrentforadvancingthestudyofintergroupcommunication.

Relatedly,anotherreasonleadingtoadearthofresearchonintergroupcommunicationcanberelatedtohowfaceisfurtherconceptualized,morespecifically astowhetheritistakentobeaccruedovertime,whichmeansitcanbeattachedto groups(Sifianou2011; Wang&Spencer-Oatey,2015)orisemergentininteraction(Arundale,1999; Haugh,2007),inwhichcaseitcannotbesharedbya group(sinceitisunlikelythatallmemberswouldbeinteractingconcurrently).

2 Goffmandroppedtheterm ‘face’ andsubstituteditwithidentityinthebulkofhiswork.

Althoughthisisakeyconceptualpointthatneedstobetackledtotheorize intergroupcommunication(see Haughetal.,2013 discussionofrelational histories),ithasnotreceivedsignificantattentionwithin(im)politenessresearch. Someexceptionsare HatfieldandHahn(2014) and,morerecently,O’Driscoll (2017:104)whoconcludedthat “itisagainnotclearhowgroupface istobe distinguishedfrom(theself-evidentlyvalidconceptof)agroup’sreputation/ image/identity.” However,hewentontocite Spencer-Oatey’s(2005) “social identityface,” thedesireforacknowledgmentofone’ssocialidentitiesorroles (e.g.,groupleader,valuedcustomer),asappearingtohavedistinctmeaning.

Inmyview,theproblemsthatface,asunderstoodintheliteraturediscussed, posesinrelationtogroupscanbebypassedbyresorting,instead,toaclosely relatedconcept:identityorthesocialpositioningofselfandother(Bucholtz& Hall,2005:586).Althoughfaceandidentityarebothsignificantlyrelatedtothe constructionandpresentationofself(Goffman,1955/1967),theyhave – forthe mostpart – beenthecornerstonesofdifferentresearchtraditions.Onefundamentaldifferencebetween(im)politenessandidentityscholarshipisthatthe latterhasdevotedconsiderablethoughttowhetheridentityisaccruedor emergentininteraction.Thereseemstobequiteuniversalconsensusinpoststructural/discursiveapproachestoidentityinthisrespect:identityisdiscursive, intersubjectivelyco-constructed, emergent ininteraction(forinstance,it involvesthoseveryephemeralsubjectpositionsthatweoccupyinunfolding discourseandthatmakeupstance),butalso durable (Bucholtz&Hall,2005).

Identitiesaredurable,notbecauseindividualshaveessentialorprimalidentities,butbecausedialogicallyconstructedidentitiesarerecreatedinmultiple localpracticeswheretheymakesenseandcreatemeaning(Holland&Lave, 2001). Butler(1990) referstoaprocessof sedimentation wherebypeoplerepeatedlydrawonresourcesthatgraduallybuildupanappearanceof fixedidentities. Whereasitistruethatcertainaspectsofperson,roleandsocialidentitiesaremore stable,eventhosearealwaysoverlappingwitheachotherandconstantlychanging(Burke&Stets,2009).BarkerandGalasinski(2001:31)sumupthiswell whentheystate: “Identitiesarebothunstable and temporarilystabilizedbysocial practiceandregular,predictablebehaviour.” Fromthisunstable/stabilized,emergent/durableperspective,itisconceptuallyquiteunproblematictotieidentity (andface,aswewillseelaterinthissection)togroups.

Inthemid-to-late2000s,identitystartedtobepresentedalongsidefaceinthe definitionsof(im)politeness.Scholarsalsobeganenquiringaboutitsrelationshipwithfaceandintroducing(im)politenessstudiestotheframeworksdevelopedfortheanalysisofidentity,arguingfortheirrelevanceto(im)politeness research(seeamongothers Spencer-Oatey,2007;Locher,2008; GarcésConejosBlitvich,2009,2013;Garcés-ConejosBlitvich&Sifianou,2017; 7 Pragmatics,(im)politeness,andintergroupcommunication

Garcés-ConejosBlitvich&Georgakopoulou,2021).Thosescholarswho arguedforamoremulti-disciplinaryapproachtothestudyof(im)politeness phenomenasawidentitymodelsasameanstoachievethatgoal,duetotheclose relationshipbetweenface,identity,andself-presentation.Proposedwaysof advancingthe fieldcanbesummarizedasfollows:

a.(Im)politenessmanifestations/assessmentscanbetiedtoidentity(co)construction,notjusttoface.

b.Identityandfaceareinseparable,astheyco-constituteeachother.

c.(Im)politenesscanbeanalyzedasanindexinidentityconstruction.

d.Modelsdevelopedfortheanalysisofidentityconstructioncanbefruitfully appliedtothestudyof(im)politeness(Garcés-ConejosBlitvich&Sifianou, 2017:238).

Sincethen,identityhaseitherreplacedfaceasacoreconceptin(im)politeness researchorhasbeenseenasessentialtograspwhatfaceentails,asfaceneeds varydependingontheidentitybeingco-constructedbyanagentengagedina specificpractice:thatis,anagent’sfaceneedsasa mother differsubstantially fromthoseofthesameagent’sfaceasa surgeon,orasa bridgeplayer.Inthis practice-basedapproach,faceandidentityareviewedasdifficulttoteaseapart ininteractionandasco-constitutingeachother(Joseph,2013; Miller,2013). Crucially,agentsengagedinpracticemayclaimorbeattributedeitheran individualorasocialidentityanditsconcomitantfaceneedsandthusgroup (social)identityisseen,fromthisperspective,asunproblematicallytiedtoface. Indeed,theconceptofself-esteemsocloselyconnectedtofaceisforemostin theconceptualizationofsocialidentityasdiscussedby Tajfel(1979) who proposedthatthegroups(e.g.,socialclass,family,andfootballteam)which peoplebelongedtoareanimportantsourceofprideandself-worth.Relatedly, Goffman(1959:85)reconceptualizedhisframeworkinmakingtheteam,rather thantheindividual,thebasicunitoftheinteractionalorder.Thegoaloftheteam istohelpteammatesmaintainthelinetheyhaveselected.Inthissense,teams/ groupsprovideuswithasenseofbelongingtothesocialworld.

2.1.2CollectiveIntentionalityandAction

Yet,anothermotivebehindtheinattentiontowardintergroupcommunicationin pragmatics/(im)politenessmayhavetodowiththemajorrolethatintentionality hasplayedinpragmaticunderstandingsoftheconveyanceandinterpretationof meaning(especiallyintheCognitive-Philosophicalfoundationalmodelsand theoriesofthe field,whichprimedspeaker-meaning,suchasSpeechAct Theory,Grice’sCooperativePrinciple,etc.).

Althoughitsroleasanaprioriconcepthasbeenquestioned(Haugh,2008a), mostpragmaticscholarsstillseeintentionasplayinga(varying)influentialrole incommunication(Culpeper,2011;differentcontributionsto Journalof Pragmatics179,2021).AsHaugh(2008b)discussed,traditionalviewsrelate intentionalityto individual utterances/speakers,butahigher-orderintention wouldneedtobeattachedtolargerstretchesofdiscourse.Inaddition,if intentionalityisunderstoodasco-constructedamongparticipantsininteraction, itmaybeappropriatetoconsidera we-intention asalsobeingapplicable (Haugh,2008a;Haugh&Jaszczolt,2012).However,Haugh(2008b)saw weintention,asdescribedinthethenextantliterature,asstaticandnotadequately capturingtheemergentnatureofinferentialworkunderpinningcooperative activities,suchasconversation.

Animportant,forthisElement,relatedquestioniswhetherweshouldappealto anontologyofgroupagents,i.e.,whenateamplays,istheteamjustmadeupof individualscoordinatinginsearchofacommongoaloristheteamitselfthatplays? Thisquestionhasbeentackledmostlyfromthepointofviewofphilosophyand resultedintotwoopposingcamps:individualismandcollectivism.Individualism understandsandexplainsbothindividualactionandsocialontologyresortingto individualsandtheirrelationsandinteractions.Foritspart,collectivismarguesthat therearegenuinelyemergentsocialphenomena,suchassocialobjects(i.e., groups),states,facts,events,andprocesses(Tuomela,2013).

Whendealingwithsharedintentions,morespecifically,twoopposingviews areupheld:(i)thosewhospousereductiveviewsofsharedintention,thatis, attributinganintentionto us – asinagroup – canbeundertakenbyresortingto conceptsrelatedtoindividualaction/intention,and(ii)thosewhodisagreewith thispositionandholdnon-reductiveviewsandunderstand we-intentions as involvinganirreducible we-mode.The we-mode approach(Tuomela,2007, 2011)ispredicatedonthecrucialdistinctionbetweenactingasagroupmember guidedbythegroupethosversusactingasaprivateperson.

Inmorerecentwork,Tuomela(2017:16)reviewedsomeofthecentral accountsofnon-reductiveviews,namelythoseespousedby Gilbert(1989), Searle(2010) andhimself(Tuomela,2013),anddescribedthemalongthe followinglines:

Groups(includingcollectivelyconstructedgroupagents)associalsystems (interconnectedstructuresformedoutofindividualsandtheirinterrelations) seeminmanycasestobeontologicallyemergent(viz.involvequalitatively newfeaturesascomparedwiththeindividualisticbasis)andinthissense irreducibletotheindividualisticpropertiesofourcommonsenseframework ofagencyandpersons onconceptualgroundscollectivestatesarenot reducibletoindividualiststates.

Despitesomecommonalities,TuomelacriticizedGilbert’spluralsubjecttheory arguingthatitiscircularandSearle’sargumentationof we-intentions as underdeveloped.Hisownproposal – basedon I-mode/we-mode ofsociability thattakesjointintention,interdependentmemberintentions(we-intentions)are expressibleby “wewilldoxtogether”– was,inturn,alsocriticizedascircular (Schweikard&BernhardSchmid,2021).Further,evenamongthosewhoagree thatcollectivescanbethesubjectofintentionalstateascription,thereis manifestdissent: Gilbert(1989) and Tollefsen(2002,2015)arguethatitis appropriatetoattributearangeofintentionalstatesincludingbeliefstogroups. Others, Tuomela(2004) and Wray(2001),disagreewiththispositionasgroups, intheirview,canacceptpropositionsbutcannotbebelievers.

Fromthisdiscussion,itsoundsasifallproposalsthatstemfromphilosophical explanationsperhapsleaveuswithmorequestionsthananswers(Weir,2014), whichmayalsoapplytogeneralapproachestoindividualisticintentionwithin pragmatics,mostlystemmingfromaphilosophyoflanguagetradition.Theroleof intentionalityininterpersonalcommunicationhasproventobedifficulttoascertain oragreeupon,andgroupintentionalityiscertainlynotanunproblematicnotion either.However,thepost-hocreconstructionofintentionalityviainferencesand attributionsiskeyincommunication,beitinterpersonalorintergroupinnature. Therefore,understandinggroupnessandtheattributionofgoalsandintentionsto groupsareessentialforhumansand,notsurprisingly,theyhaveplayedamajorrole inthedevelopmentofthespecies’ socialcognition(Tomasello&Rakoczy,2003).

Certainly,knowledgeaboutgroupscarriesimportantand,sometimes,vital informationandimpactsattitudesandbehaviors(ingroupbias,implicitbias, moralobligations);therefore,itseemsessentialforhumanstobeabletocategorizeothersasnon/members.Apparently,thisissomethingthatchildrenasyoung as3caneasilydo,usingmutualintentions(i.e.,thegeneralagreementof individualsthattheybelongtoagroup, Noyes&Dunham,2017:34)asaguiding principle,closelyconnectedtoperceivedcommongoals(Strakaetal.,2021). Oncegroupsareconstitutedsocially,childrenseemstronglyinclinedtobelieve thatgroupnesssanctionsspecificwaysofrelatingandcarrieswithitpatternsof behavior,association,andmoralobligations(Noyes&Dunham,2017:141).

Thus,howpeoplearetransformedfromarandomcollectionofindividuals intoagroup,asocialunit,orientedtojointactionis,accordingtoJankovicand Ludwig(2017:1–2) thewaytheythink aboutwhattheyaredoingtogether;this wayofthinkingconstitutesthefocusofstudyofcollectiveintentionality3 (CI) whichcanbedefinedas:

3 Itisimportanttopointoutthatintentionalityisnotlimitedtointentions,whichareapropositional attitudedirectedatactions.Intentionality “encompassesallthepropositionalattitudes – believing, desiring,fearing,hoping,wishing,doubting aswellasperceiving imagining and

Theconceptualandpsychologicalfeaturesofjointorsharedactionsandattitudes andtheirimplicationsforthenatureofsocialgroupsandtheirfunctioning. Collectiveintentionalitysubsumesthestudyofcollectiveaction,responsibility, reasoning,thought,intention,emotion,phenomenology,decision-making, knowledge,trust,rationality,cooperation,competition aswellashowthese underpinsocialpractices,organizations,conventions,institutions,andontology.

TheauthorsseeCIascrucialtounderstandingthenatureandstructureofsocial reality.Inthistheycoincide,amongmanyothers,with TomaselloandRakoczy (2003), Tomaselloetal.(2012),and Strakaetal.(2021) whoclaimthatCIis whatmakeshumancognitionunique.Morespecifically,Tomaselloand Rakoczy(2003:123,143)arguethatCIrelatedskillsunderliechildren’s culturallearningandlinguisticcommunicationandenablethecomprehension ofculturalinstitutionsbasedoncollectivebeliefsandpractices.ThisisimportantasCIis,therefore,seenasthefoundationforsocialnorms,whichemanate notfromindividualbutgroupopinion.Asaresult,conformingtosocialnorms displaysgroupidentity.Inthesamewaynotabidingbythemsignalsdisdainfor thegroup.Thatiswhy,asisthecasewith CC, “punishmentforthelaggard needstobebythegroupaswhole – sothatwhenanindividualenforcesasocial norm,sheisdoingso,ineffect,asanemissaryofthegroupaswhole” (Tomaselloetal.,2012:683).Thenormsthatdefinethegroupanditsgoals andassignrolestoitsmembers,thatis,thegroup’sCI,areinturninternalized bythosemembers,accordingto Tomasello(2018:74)as “‘anobjective morality’4 inwhicheveryoneknewimmediatelythedifferencebetweenright andwrongasdeterminedbythegroup’ssetofculturalpractices.”

Theseclaimsareconsequential,notonlyforthisElementandtheunderstandingof cancelation practices,butalsoforpragmatics.Norms,thequintessential pillarsofresearchinmanypragmaticsubfields((im)politenessamongthem)are theoutcomeofgroups’ collectiveintentionality.Therefore,apragmatics/(im) politenessofintergroupcommunicationneedstoincorporate(social)identityand collectiveintentionalityaskeytheoreticaltenets.Socialidentity – anindividual’s cognitive,moral,andemotionalconnectionwithabroadercommunity,category, practice,andinstitution(Polletta&Jasper,2001) – isessentiallyconnectedto collectiveintentionalityandbotharefundamentaltounderstandingthetypeof collectivemobilizationinvolvedin cancelation. emotionsdirectedatobjectsandevents(e.g.,beingangryataperceivedslight)(Jankovic& Ludwig,2017:1).

4 Objectivemoralityreferstotheconceptualizationofmoralityasuniversal,notupforinterpretation.Anobjectivemoralityof “rightandwrong” isthelaststage,accordingto Tomasello(2018), oftheevolutionofmodernhumanmorality.Thisstageisprecededbyself-interest(tiedto individualintentionality)and “asecondpersonmorality”,thatis, me hastobesubordinatedto we,keyedtojointintentionality.

Thisincorporationisnotcomplicatedifonetakesadiscursiveapproachto pragmatics/(im)politeness).Indeed,asthe fieldunderwentadiscursiveturn (Barron&Schneider,2014; Locher&Watts,2005),identitygainedprominence.Thisisunsurprisingas,accordingtodiscoursetheorists(Fairclough, 2003; Gee,2005),theconstructionofindividual/social(group)identityisat thecoreofdiscourses,andthelatterfundamentallyinvolvescollectiveintentionality.Fromthisperspective,therearenoapparentobstaclesforpragmatics todealwithinterpersonal and intergroupcommunication.Inaddition,aswillbe discussed,discoursepragmaticspayscloseattentiontothemeso-level,thelevel ofgrouppractices.

2.2ADiscursivePragmatics

Totacklepragmaticphenomena,weneedtogroundtheirstudyinamodelthat includesthethreelevelsofsociologicalenquiry,accountsfortheinterconnectionsamongthem,andoffersscholarswell-developedmeso-levelunitsthatcan teaseouttherolecontextplaysin – forinstance – assessmentsof(im)politeness (Garcés-ConejosBlitvich,2010c,2013).

Traditionally,three(interconnected)levelsofenquiryhavebeenidentified/ applied:macro/meso/micro.Usedextensivelyinmanydisciplines,whatexactly theyrefertois,somewhat,specifictoeach.Insociolinguistics/discourseanalysis,macroreferstobeliefsystems,ideologies,socialstructure,andinstitutions;mesounitsofcommunicationareemployedbygroupsandcommunities ofpractice,suchasspecifictypesofdiscourseorgenres;whereasmicrorefersto specific,localinteractionsamongparticipantswithspecialattentiontothe syntactic,interactional,phonological,orlexicalresourcesdeployed.

Inarecentdiscussion, Garcés-ConejosBlitvichandSifianou(2019) argued that(im)politenessresearchhadmostlyfocusedonthemacro/micro-levels withoutmuchregardtotheessential,mediatingroleofthemeso-level(but seeCulpeper,2021amongotherpublications).Inaddition,theshortcomingsof somemeso-levelunitsofanalysiscommonlyusedin(im)politenessresearch, suchasframes,communitiesofpractice,andactivitytypes,wereconsidered.A wayforwardwasproposed:theselimitationscouldbeassuagedbyresortingto well-established,tripartitediscoursemodelssuchasthatproposedby Fairclough(2003)5 andtogenreasakeymesounitofanalysis.

Relevanttothisconversationisthefactthatthestartingpoint,asitwere,of Fairclough’smodelisarebukeofBourdieu’sviews.ForFairclough,akey

5 Please,notethatalthoughFaircloughappliedhismodelmostlytoworkonCriticalDiscourse Analysis(CDA)thisdoesnotmeanthathismodelisCDAbasedororiented.Itcanbeappliedtoa non-critical,descriptiveanalyses.

omissionofBourdieu ’smodelisthelackofattentiontothemeso-level.Asan example,whendiscussingpoliticaldisc ourse,Fairclougharguesthatpoliticiansneverarticulatepoliticaldiscours einitspureform:politicaldiscourseis alwayssituated,alwaysshapedbygenres(presidentialspeeches,pressconferences,debates,etc.).Incontrast,genre(meso-level)notionsplayafundamentalroleinFairclough’saccountoflanguagesocialpractices,thatis,orders ofdiscourse.Ordersofdiscoursearedefi nedas “thesocialorganizationand controloflinguisticvariation ” (2003:24).Asshownin Figure1,theway discourse figuresinasocialpracticeisthusthreefold:discourses(waysof representing),genres(waysofacting,i nter-actingdiscoursally),andstyles (waysofbeing).

Theterm “discourse” ishereusedintwoways:(i)asanabstractnoun referringtolanguageandotherkindsofsemiosisaselementsofsociallife, (ii)asacountnounreferringtowaysofrepresentingapartoftheworld – for example,thediscourseofthealt-rightintheUSA.Styles,inturn,refertothe roleoflanguage,alongwithnonverbalsemioticmodes,increatingparticular socialorindividualidentities.Faircloughseesthesethreeelementsofmeaning asdialecticallyrelated,eachoftheminternalizingtheothers.In Fairclough’s (2003:29)words: “particularrepresentations(discourses)maybeenactedin particularwaysofActingandRelating(genres)andinculcatedinparticular waysofIdentifying(Styles).” Morespecifically,stylerefersto “thedifferent waysinwhichindividualstalkindifferentsituationstoenactdifferentidentities” (Jones&Themistocleous,2022:135;seealso Coupland,2010). Discourses,genres,andstylesaredurableandstable,buttheyarealsoin constant flux.Atthestylelevel,agentsarecarriers,asitwere,ofdiscourse/ genres.However,theydonotmerelyreproducethem,byconstructingrecognizableidentities,butcanreinterpret/reinventtheminaway,thatifconstantand shared,maysignificantlyalterthegenreand,inturn,thediscourse.

Therefore,themodelincludesthethreelevelsofsociologicaldescription (discourse/macro,genre/meso,style/micro)and,importantly,seesthemas

– representations

Discourse

dialecticallyrelatedinthesensethatnotonlythemacro/meso-levelshavean impactonthemicro-level,butthatchangesinthemicro-levelcanaltergenres andultimatelydiscourses.Forexample,theeruptionof CC’ s,amacro-level phenomenon,secondwavehassubstantiallyalteredthemicro-levelrealization of cancelation andthespacesinwhichitisconducted(Section6).

Inamorerecentreformulation, Fairclough(2004:381–382)addedanother keyelementtohismodel:thatis, texts, “[g]enres,discoursesandstylesare realizedinfeaturesoftextualmeaning.” Genressituatediscourses,buttheyare stillabstractions(wehaveasociallyacquiredsenseandexpectationsofwhata lectureorhealthcareencounterare).However,genresthemselvesare instantiatedintexts:thesociallysituated,individually/collectivelynegotiatedinstantiationsofgenres.

As Fairclough(2004:229)argues “[t]extsarethesituationalinteractional accomplishmentsofsocialagentswhoseagencyis,however,enabledand constrainedbysocialstructuresandsocialpractices.” Forexample,ideologies, suchashowclassesshouldbetaught,arepartofourrepresentationofEducation Discourse.Foritspart,EducationDiscourseissituatedindifferentgenres,a lecture,forinstance.Thewayaprofessordeliversanactuallecturewillbe instantiatedina text thatwillreflectthediscourseandthegenrebutwill uniquelybeshapedbytheprofessor ’sandthestudents’ stylesandtheiragencies.Thus,althoughtext(asintextlinguistics)wasinitiallyanattempttoextend grammaticalprinciplesbeyondthesentence,nowadaysitis “widelydefinedas anempiricalcommunicativeeventgiventhroughhumancommunicationrather thanspecifiedbyaformaltheory” (deBeaugrande,2011:290).Consequently, discursivepragmatics’ analyticfocus – andthestudyof(im)politeness anchoredtherein – isthe(writtenorspoken) text. Goingbacktothemodelbeingdiscussed,Pennycook(2010),likeFairclough, acknowledgedthecentralityofgenreinmodelsofcommunication(seealso Blommaert2008,2017a)and – tomovepracticetheoryforward – proposedto reconceptualizediscourse/genre/styleaspractices: discourse,genreandstyle,whenviewedintermsofpractice,directour attentiontodifferentwaysinwhichweachievesociallifethroughlanguage: weconstructrealitiesthroughdiscursivepractices,fromtemporaryregularitiestogetthingsdonethroughgenericpracticesandperformsocialmeanings withdifferenteffectsthroughstylisticpractices.(Pennycook,2010:122)

ThedialecticrelationshipbetweenFairclough ’sthreelevelsiscrucial. Inparticular,genreandstyleexemplifythedualnatureofpracticewhichis: notreducibletoindividualactivitynortosociallyorideologicallydetermined behavior ... AsKemmis(2009)suggests ... practicesrefiguretheactionsof

particularactors thesearrangementsofsayings,doing,set-upsandrelationshipsarenotindividualattributesbutratherasetoforganizingand mediatingconditionsthatrenderactivitycoherent.(Pennycook,2010:28)

Thiscoincideswith Garfi nkel ’s(2002) viewthatitispractices,notindividuals,thatconstitutetheessentialfoundationsofsocialstructureandisvery relevantforthepresentdiscussion:somegenrepractices – suchasdemonstrations,boycotts,groupexclusion, cancelation ,arecollectiveinnatureand cannotbereducedtotheindividuallevel.Inaddition,therestofgenre practices(althoughnotnecessarilycollectiveasintheotherexamples)such as,forinstance,aserviceencounter,alsoinvolvetwosalientsocialidentities (service/providerandcustomer,ofcourse,coloredbyindividualstyles)that cannotbeunderstoodunlesswithreferencetoagroupandthusconstitute intergroupcommunication.

Takingadiscursiveapproachandgenrepracticesasameso-levelunitallows ustocircumventanypotentialproblemsregardinganalyzingcollective/intergroup-basedpractices,astheyarepartandparcelofgenericexpectationsand constraints.Further,adiscursiveapproachallowsustoconceptualizehow discoursesareoftennotrealizedbyjustonegenrepracticebut,aswith CC, byagenreecology(multiplegenresworkingtogethertoachievethesameend) broughttogethercontingentlyforeachcaseof cancelation (Section5).Inthe nextsections,Ipaydetailedattentiontothemeso-levelasthelevelofgenres practicesandthelevelofgroups,respectively.

2.2.1GenresandtheMeso-Level

AsemphasizedthroughoutthisElement,meso-levelpracticesareessentially relatedtogroupsand,thus,mergeinwellwiththeintergroupperspective advocatedhere.Intakingthisstep,aspragmaticsbecomesdiscourse-centered, pragmaticiansofdifferentpersuasionscandrawinterdisciplinarilyfromlinguisticandrhetoric fieldsthathavemademeso-levelpracticesoneoftheirmain objectsofresearch,suchasSystemicFunctionalLinguistics,Englishfor SpecificPurposes(ESP),andRhetoricalGenreStudies.

ItisthelasttwoapproachesImostlydrawfrominmyownunderstandingof genre.Regardingthe first,initsfoundationalpaper, Miller(1984) approached genreassocialactionanddefinedgenresas “typifiedrhetoricalactions” that respondtorecurringsituationsandbecomeinstantiatedingroups’ behaviors. Millerarguedthat “arhetoricalsounddefinitionofgenremustbecenterednot onthesubstanceortheformofdiscourse,butontheaction,itisusedto accomplish” (151),which – inMiller ’sview – makesthempragmaticinnature. Bazerman(1997:19),akeycontributortothisapproach,summarizesitwell:

Genresarenotjustforms.Genresareformsoflife,waysofbeing.Theyare framesforsocialaction.Theyareenvironmentsforlearning.Theyare locationswithinwhichmeaningisconstructed.Genresshapethethoughts weformandthecommunicationsbywhichweinteract.Genresarethe familiarplaceswegotocreateintelligiblecommunicativeactionwitheach otherandtheguidepostsweusetoexploretheunfamiliar.

Further,genresarestabilized-for-nowbutconstantly-in-fluxsitesofsocialand ideologicalaction(Berkenkotter&Huckin,1993)andthus recognizable by membersofcommunities.AsBazerman(1994:100)pointedout, “[w]ithouta sharedsenseofgenre,otherswouldnotknowwhatkindofthingwearedoing.” Importantly,asthemeso-levelrealizationofdiscourses,genresopencertain positions,roles,andrelationships,sinceidentityisalwaysatthecoreofdiscourses/genres(Bazerman,1994;Blommaert,2017a; Fairclough,2003; Gee, 2005).Relevanttoourdiscussion,knowledgeofgenresthroughsocialization practicesincludesrhetoricalexpertise,dynamicknowledgeofprocessesand audience ’sexpectations(regardingnorms ofbehavior,forinstance)( Tardy, 2009 )

Miller(2015),whenponderingontheinfluenceofherfoundationalviews, arguedthatgenrecontinuestobeausefulconceptbecauseitconnectsour experiencestooursenseofthepastandthefuture,makesrecurrentpatterns significant,andveryimportantlyforthisElement,itcharacterizescommunities byofferingmodesofengagementthroughjointactionanduptake.6

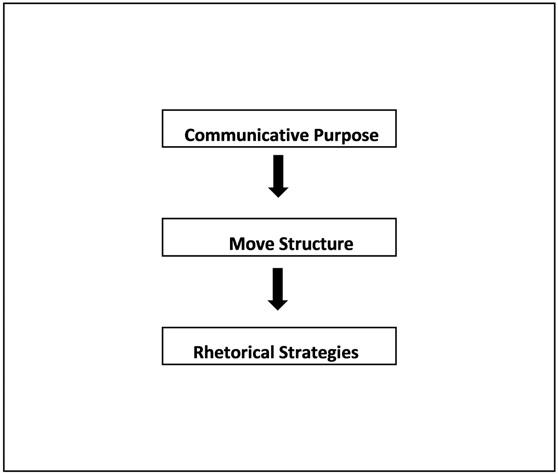

WithinESP,oneofthemostinfluentialdefinitionsofgenrewasprovidedby Swales(1990:58): “Agenrecomprisesaclassofcommunicativeevents,the membersofwhichsharesomesetofcommunicativepurposes.Thesepurposes arerecognizedbytheexpertmembersoftheparentdiscoursecommunity,and therebyconstitutetherationaleforthegenre.” Swales’ modelisreferredtoas thethree-levelgenremodelandprovidesausefultemplatefortheactual analysisofgenres.

Communicativepurpose/goalemergesasthemainrationaleforthegenreand triggersamovestructure.Movesareunderstoodasdiscoursalorrhetoricalunits thatperformacoherentcommunicativefunctioninawrittenorspokendiscourse(Swales,2004:228),wheresomemovesareessential/obligatoryand othersarenonobligatory.Forinstance,inresumes,oneisexpectedtoincludea part(move)oneducationandanotheronprofessionalexperience,whereasa moveonhobbiesisnotnecessarilyexpected.Fortheirpart,rhetoricalstrategies refertothedifferentsemioticmodes(lexico-grammaticalstructures,jargon, layout,font,register,amongothers)usedatthemicro-leveltorealizeeachmove

6 “Uptake” istheillocutionaryresponseelicitedbyparticularsituations.

andcarryoutthegeneralpurposeofthegenre,andare,therefore,audiencedesigned.Tocontinuewiththesameexample,aresumefollowsawell-establishedandrecognizablelayoutandusesprofessional-lookingfonts;itshouldbe formalinregister,use field-relatedjargon,beshort(circatwopagesforcorporatejobs),andsoonInthisrespect,asmentioned,genresarestabilizedfornow andsocio-rhetorical;therefore,movestructureandrhetoricalstrategiesarealso in fluxascommunities’ conventionsandexpectationschangeorinfluential trailblazersfundamentallyalterthegenreinabottom-upfashion.

Relatedly,theadventofdigitaltechnologiespartlychanged,amongmany others,ourconceptualizationoftextsandgenres,astraversalsfacilitatedby hyperlinkscreatedsignificantlydifferentexpectationsregardingthe finiteness oftextsandthehighhybridizationofgenres(Bhatia,2015; Lemke,2002). Althoughmentionedinrelationtodigitalmediation,as Bhatia(2015) argued, hybridizationisaconstantacrossgenres,despitescholarshiphavingtendedto focuson “pure” genres.Forinstance,antitobaccobillsmergeandenactlegal andhealthdiscourses.However,genresdonotonlymergeandinfluenceone another,theyrelatetoeachotherinamyriadofotherways,asitisnotoftenthe casethatagivenactivitycanbecarriedoutbyjustonesinglegenre.Notehowa politicalcampaignoracollegeapplicationinvolvemanygenrespractices comingtogethertoachieveaspecificgoal:being(re)electedandbeing(re) admitted,respectively;thosegenrepracticesinclude,tonameafew,fromphone callsandletterstopotentialvoters/donors, flyers,rallies,fundraisers,andsoon, inthecaseofcampaigns,andapplicationforms,statementsofpurpose,official

Figure2 Swales’ model.

transcripts,lettersofrecommendation,meetingswithacademicadvisorsand financecounselors,andsooninthecaseofapplications.

Asaresult,scholarshavedevisedconceptualizationsregardinghowgenrescome together,suchasingenresets(fullrangeofthekindoftextsthatonepersonusesto filloutonesideofamultiple-personinteractions,Bazerman,1994),genresystems (“interrelatedgenresthatinteractwitheachotherinspecificsettings,” Bazerman, 1994:97),genrerepertoires(“Thesetofgenresthatareroutinelyenactedbythe membersofacommunity,” Orlikowski&Yates,1994:542),genresequences (asimilarconcepttogenresystems, Swales,2004),genrecolonies(atermdevelopedtodescribehowgenresmovefromoneactivitysystemtoanothertocreatenew clustersofgenres,Bhatia,2002),andgenreecologies(acontingent,interacting, interdependentsystemornetworkofgenres,asdistinctfromaseriesofgenreswith aspecificallysequentialseriesofuptake, Spinuzzi&Zachry,2000).7

Itisthelastconcept,genreecologies,thatI findparticularlyuseful.Applying thismodeltothedata,Iwillarguethat cancelation iscarriedoutbycomplex genreecologies(Section5.2).

3GroupsandtheMeso-Level

Outofthethreesociologicallevelsofanalysisdescribedanddiscussedin Section2.2,themeso-levelhasbeenoneofthemostdebatedandproblematized dimensionsofsocialtheoryandsociology(Serpa&Ferreira,2019).What scholarsagreeonisthatsocialorderisembodiedinpatternsofsocialrelationships,occurringindifferentdomainsandscales,andseen “inthesimilaritiesof individualbehaviorsasinthe regularitiesofencountersbetweenhumanagents, in theestablishmentofgroups andorganizationsasinthefunctioningof institutionsandinthedistributionofsocialresources” (myemphasis, Pires, 2012:40).

Regardinggroups,as Fine(2012:159)pointsout, “Afocusonthegroups –themeso-levelofanalysis – enrichesbothstructuralandinteractional approaches,stressingsharedandongoingmeaning.Groupsconstitutesocial order,justasgroupsthemselvesareconstitutedbythatorder.” Morerecently, FineandHallett(2014) arguedthatgroupsandthemeso-levelnotonlymediate themicroandthemeso-levels,butthatthemeso-levelhassemi-autonomous propertiesanddynamicsthatshapeeverydaylife.Thesedynamicscanbe relatedto fiveprocessescruciallyrelatedtogroupsby HarringtonandFine (2000) namely,controlling,contesting,organizing,representing,andallocating, someofwhich,aswewilldiscuss(Section6),areofkeytothepresentanalysis. Theseprocesses,accordingtotheauthors,showthatgroupsarethelocusof

7 See Spinuzzi(2004) foradetailedcomparisonofgenreassemblages.

socialcontrolandsocialchange.Whatisclearisthatthroughthestudyof groups,wecanconcentrate,amongothers,onsocialidentity,collectiveintentionality,collectiveactionviaengagementingenrepractices,andgroupculture, whicharekeytotheunderstandingof CC andthepracticeof cancelation,which aimstoeffectbothsocialcontrolandsocialchange(Garcés-ConejosBlitvich, 2022a,2022b).

Asdiscussed,groupsareessentialtocognitionandtosociety(Section2.1.3). Notsurprisingly,groupresearchhasalongtrajectory(startinginthe1850sand gettingestablishedin1930s) andhasbeenapproachedfromavarietyofdisciplines(psychology,sociology,anthropology,philosophy,organizationalscience, andeducation,tonameafew(Gençer,2019). Providingadefinitionofgrouphas provennottobeeasy,asitmayoverlapwiththatofnetwork,community,or organization(Fine,2012:172). Fine(2012:160)claimsthattheyarean “aggregationofpersonsthatischaracterizedbysharedplace,commonidentity,collectiveculture,andsocialrelations.” Tobeagroup,acrowdshouldhavecommon objectives,norms,andshareafeelingofgroupness(Gençer,2019).Inaddition,it hasbeenarguedthat emotionalcommitment toagroupanditslocalculturesetsthe standardsforactionthatshapethegroupandprojectthisactionoutward(Lawler, 1992).Tyinggroupstotheirmeso-levelpractices,Garfinkel(2002)doesnot definegroupsonthebasesofdemographiccharacteristics,kinshiprelations,or culturalpractices/beliefsheldbypeopleacrosstime,space,andpoliticalconnections.Instead,groupsaredefinedbyGarfinkelbythepracticesthatconstitutetheir membership.Therefore,toconstituteagroupasetofpersonsneedstobemutually engagedinenactingasituatedpracticeinawaythatsaidpracticesdefinethe pertinentsocialidentitiesandinteractionalpossibilitiesforallofthoseinvolved –therebyconstitutingthemasrecognizableandcompetentmembers.

Further,scholarshiphasprovideddifferentclassificationsofgroups,among others:primary/secondarygroups,basedoncontact;ingroup/outgroup,based onidentification;formal/informalgroups,basedonrules/regulations;voluntary/involuntarybasedonchoiceofmembership;institutional/non/institutional; temporaryandpermanent;un-social,pseudo-social,anti-social,andpro-social groupsbasedonrelationtosociety;large/smallinrelationtosize(see Gençer, 2019,foradiscussion).

Signi ficantlyforthisElement,relatedresearch(Blommaert,2017a,2017b) hasalsodistinguished,between “ thick” groups – thatis,(i)traditional demographiccategories(suchasrace,gender,ethnicity,nation,class,caste, family,profession,andreligion)and(ii)tight-knit,establishednetworksin whichpeoplesharemanynorms,valuesandcollectiverepresentations –and “ light ” groups,orlessconspicuousformsofrelationshipandsocial interaction(suchas thoseobservedby Goffman,1961 )whichinvolve

momentsoftightbuttemporarygroupness(Blommaert,2017b).Light groups,althoughalsocommonof fl ine,arecloselyrelatedtoonline interactions – suchasthosethatformaroundparticularcon fi gurationsof communicativeresourcesandsocialpractices:frommemestoconspiracy theories,toonlineplatformchallenges – andtowhathasbeenlabeledthe “ networkedsociety ” ( Castells,1996 )whichhassubstantiallyalteredthe essenceandunderstandingofgroups,astheycannotbecontainedwithin traditionalboundaries( Appadurai,1996 ).Iwillreturntothispointinmore detailinthenextsection.

Althoughthickgroupshavetraditionallyreceivedthebulkofacademic attention,formostpeople,in “dailylivedexperiencemembershipin ‘light’ communitiesprevailsoverthatof ‘thick’ communities” (Blommaert,2017a: 50).Therefore,understandingcontemporaryformsofsocialcohesionrequires anawarenessofthekeyroleoflightcommunities.Itisimportanttoconsider, however,thatthethick/lightdistinctionshouldbetakenasacline,ratherthan discreetcategories.Inthisrespect, Fine(2012:65)claimsthatsociability networks,thatis,lightinteraction,canevolveintoathickformofcommunity whenmemberscollaboratetowardacommongoal.Similarly,Blommaert (2017a)concurredthat “light” communitiescanexhibitmanyfeatureshabituallyascribedto “thick” communities.Forinstance,lightcommunitiescan displayaheavyqualityduetothepassion,zeal,andsharedoutrage/violence thatthoseinvolvedinthemcanexpress.

Itcanbearguedthatthisisthecaseofthelightgroupsthatassemblefor cancelation pursuits(referredtoasmobsorsocialjusticeactivists,depending onideologicalpositioning, Romano,2021).Thesharedgoalsofexpressing outrage,enactingsocialregulation,anddenouncing,exposing,andmaking canceleesfaceconsequencesfortheiractions(Garcés-ConejosBlitvich, 2022b),aswewillsee,givethegroupentitativity(i.e.,howmuchagroupor collectiveisperceivedbyothersasanactualentitywithcohesion,coherence, andinternalorganization,ratherthanjustacollectionofseparateindividuals) andmakeitcoalescearoundrecognizablegenrepractices – cancelation, Sections5 and 6 – thatco-constitutethegroupidentity.Further,theselight groupscanmeshwithothermoreestablishedthickgroups(asinthecaseof cancelation whichisaprimeexampleoftheon/offlinenexusofpostdigital societiesandinvolvesbothon-andoff-linepractices, Section5) tocarryout powerfultypesofactivismthat,insomecases,havebeenlikenedto “revolutionaryaction” (Costea,2017).

Regardlessofitsthickness/lightness,agroup’sidentitywillbecloselytiedto thegenrepracticesitengagesin – thatis,agroupiswhatagroupdoes (Angouri,2015:325), cancelation inthecasehereunderscrutiny.As

Blommaert(2017a:40 – 45)hasarguedregardinghisgenretheoryofsocial action, “ [c]ommunicativepracticeisalwaysandinvariablyanactofidentity [and]identityworkis genrebased. ” Socialactors,thatis,groupmembers, areephemeral(theypasson,mayleavethegroupandjoinothers,etc.)but iterativegroup-associatedpractices,althoughalwaysin fl ux – andthusalso creative,inthesensethattheycandeviatefromgenretemplates – tendtoremain andofferthenecessarycontinuityandrecognizability(Blommaertetal.,2018; Garfinkel,2002)forthegrouptoperpetuateitself.As Rawls(2005) argued,itis situationsthataffordtheappearanceofindividualsandnottheotherwayaround. Inotherwords,practices/actionsgeneratethosewhoareinvolvedinthem.

Whatisalsokeytothisdiscussionishowgroups(eitherthickorlight) becomeagents.Aswithotheraspectsofgroupresearch,itismostlythick groupsthathavebeenseenasconstitutinggroupagents,thatis,agroup organizedtohavegroup-levelrepresentationandmotivationandthecapacity toactontheirbasis.Groupagents – suchasseveraloftheonesthatparticipated inthethree cancelations hereunderscrutiny,forinstance,NBC(National BroadcastingCorporation),ESPN(EntertainmentandSportsProgramming Network),andtheHouseofRepresentatives – havesystemsinplacetoprocess individualvoices,opinions,andsoon,intoasingularvoice(voting,decision hierarchies,etc.).Importantly,thebeliefs,decisions,andactionsweattributeto thegrouparenotreducibletothebeliefsofindividuals(List&Pettit,2011;see Section2.1.3foradiscussionofnon-reductiveviews).

However,canlightgroupsbecomegroupagents?Iwillarguethattheycan, albeitindifferentwaysfromthickgroups.Whatmakesthetwoprocesses similaristheclaimingofcertainsocialidentities,theestablishmentofcommon goals,emotionalinvestment,andtheinvolvementincollectiveactiontoachieve saidgoals.Inthecaseofthelightgroupsthatengageinonline cancelation, onlinespacesplayakeyroleinfacilitatinggroupentitativityandagency.

3.1GroupsandOnlineSpaces

In Section4,thesituatednessandhistoricalaspectsof CC willbescrutinized;here, thefocuswillbeonthespaceswhereonline cancelation takesplace,andwhich facilitatethoselightgroupsinvolvedinthepracticetobecomegroupagents.Space emergesaskeybothforthisElementandgroupsingeneral.Relevantforthis analysisistheconceptof scenes,thatis,placesinwhichindividualswithsimilar interestsgatherwiththeexpectationof findinglike-mindedothersandengagingin sharedaction(Fine,2012).The scenes ofthetwenty-firstcenturyareoftenmediated digitally.

Indeed,asmentioned,digitalcommunicationwasinstrumentalinestablishinganetworkedsociety(Castells,1996;Papacharissi,2011)bygreatlyfacilitatingthecreationofendlesstypesofgroupingsand,indoingso,itwasalso conducivetotheproblematizationoftraditionalconceptssuchas group, community, andsocial network.Inthisrespect,translocality,amongothers,has fundamentallyshiftedhowgroupnessemergesonline,asitisnolongerpredicatedonstrongandlastingtiesanchoredinsharedbodiesofknowledgeor facilitatedbytemporalorspatialco-presence(Varis&vanNuenen,2017). Similarly,ithasbeenarguedthatindividualizationisakeyfeatureofglobal connectivity;itassumesthat “digitalcommunicationnetworkshavetransformedpeople’ssocialrelationshipsfromhierarchical,arranged,stable,tightly, anddenselyboundedgroupstomore fluid,dispersed,episodic,andless boundedrelationships globalnetworkedaudiencesareactiveagentswho canmakefreechoicesbasedontheirowninterests,preferences,andaffiliations” (Li&Jung,2018:4).Alternativeconcepts:onlineaffinityspaces (Gee, 2005), ambientaffiliation (Zappavigna,2014), conviviality (Blommaert& Varis,2015)wereproposedtocapturethelightnatureofonlinegroupness, theoften-limitedrequirementsforgroupaffiliation(sharedactivities,interests, andcommongoals)andparticipation(Blommaert,2017a).

Often,thesegroupingshavebeendescribedascommunitiesofknowledgeor epistemicorientedcommunities,althougheudaimonic(i.e.,pertainstothe personalfeelingslinkedwitheudaimonia,orstrivingforhumanexcellence throughvirtuousliving)socialvariablessuchastheestablishment/maintenance ofsocialrelationshipsofconviviality,groupcohesion,desireforhappiness, self-efficacy,etc.havebeenseenasfacilitatingtheformationofthatcollective knowledge(Blommaert,2017a;Vähämaa,2013).Scholarshavealsodevoted significantattentiontohashtag/memicactivismandthegroupsthataretemporarilyormorepermanentlyunitedviathecommonuseofahashtagorthe continuouspermutationandrecontextualizationofmemes(seeBlommaert, 2017b; Bonilla&Rosa,2015; Zeng&Abidin,2021).Clearly,ambientaffiliation,onlineaffinityspacesarenottraditionalgroups,butasenseofcommunity isevidentinthedifferentandoftenfrequentwaysinwhichonlineusersattempt toreachandconnectwitheachother.

Cyberspacedoesofferamultitudeoftranslocaldigitalspaceswherelikemindedindividualsengageindifferenttypesofgroup-sharedaction.Digital spacesarethusveryfacilitativeofgroupformationsandprovideawindowinto howpeoplebehaveasmembersofgroups,thatis,whentheirsocialidentityis salient,andengageinintergroupcommunication.Intergroupcommunicationis pervasiveonlinesincedigitalenvironmentsfoster deindividuation.Although initialdeindividuationmodelsrelatedittoantinormativeconduct,other

approaches(astheSIDE,SocialIdentityModelofDeindividuationEffects, model,basedonSocialIdentitytheory; Reicheretal.,1995)havearguedthat deindividuation,indigitalenvironmentsdoesnotnecessarilyfosterderegulationofsocialbehaviorbutincreasesthesaliencyofsocialidentityandgroupassociatedsocialnorms,whicharekeytointergroupcommunication.Inthis sense,oftenintechnologicallymediatedpractices,individuals’ personalcharacteristicsmustbesetasideinordertoparticipatesuccessfully(Rawls,2005).

Itisimportanttoconsiderthatthepositiveconnotationsofaffiliation,affinity, andconvivialitymaypredisposeonetothinkofonlinecommunitiesasrapportbasedgroupings,engaginginplayfulnessandotherludicactivities(Blommaert, 2017b)devoidofanyintra/intermanifestationsofconflict.However,thisisnot alwaysthecase(see Blommaert,2017c;GarcésConejosBlitvich,2021,2022a, 2022b),asnotinfrequentlygroupswillassembleonlineverypurposefullyto turnsomescenesintothe tyrannicalspaces (Andrews&Chen,2006)where cancelation takesplace.

CC – morespecificallyinits firstwave(Section4.2) – wasunderstoodasa waytochallengeandholdaccountablepowerfulindividualswhohadbeen perceivedasactingimmorallyand,concurrently,toempowertraditionally disenfranchisedgroupsbygivingthemavoice.Collectiveprotestandboycott wereunprecedentedlyfacilitatedbymassiveaccesstoonline,publicspaces.In thissense,onlinespacescanbelikened,withafewcaveats,to “freespaces.” Accordingto RaoandDutta(2012),freespacesarearenas – inorganizations andsocieties – shieldedfromthecontrolofeliteswhichpromotecollective empowermentandintenseemotionandtriggercollectiveidentities,enabling individualstoengageincollectiveaction.Arguingthatmoreattentionneedsto bepaidtohowprotestspacesthemselvesshapeinteractionandstrategies therein, Au(2017) reconceptualizedonlinespacesas “freespaces” andtied themtotheaffordancesandconstraintsofferedbydigitalmediawhichenable certaintypesofengagement(andnotothers).Morespecifically, Au(2017:147) claimedthatonlinefreespacesarestrategicinsupportingtheexchangeof information,massrecruitment,andtheexpressionof(oppositional)identities (cancelersand canceleesinthiscase).

Takingintoconsiderationthatmostsocialmediaplatformsareinthehandsof powerfulindividualsandcorporationsandregulatedbyproprietaryalgorithms aboutwhosefunctionandimpactonusweknowlittle(Cheney-Lippold,2017),it ishardtoequateonlinefreespaceswiththeinitialconceptualizationsoffreespaces ascompletelyshieldedfromthecontroloftheelite.Nonetheless,theycertainly meettheotherrequirements,and,notably,algorithmsthemselvesplayarolein bringinglike-mindedpeopletogether,and, thus,ingroupformation,bycirculating contenttopeoplebasedonwhattheyhavebeenengagedwithinthepast.

Thisconceptualizationofonlinefreespacesasshapinginteractionand facilitatingtheemergenceofcertainidentitiesisinlinewith Goffman’s (1963b),ScollonandWongScollon’s(2003),and Blommaert’s(2013) views onon/offlinespacesasbeingregulativeandthushistorical,political,andtiedto emotions;thelatterisalsoarguedbyemotionalgeographies(Davidsonetal., 2005),thatis,thestudyofthefeelingspeopleattachtophysicalplaces(i.e.,how emotionsbothhavespatialaffectsandaffectspace).Indeed,itisduetothe collectiveorganizational/regulative/emotivepowerthatonlinespacesafford thatsuchlightgroupingscanbecomegroupagents.Itisimportanttonotethat becominggroupagentsisessentialtothenengagewithothergroupsagents,the offlinethickgroupsalreadymentioned,suchasthosethatultimatelycarryout cancelation.Aswewillsee,thecomplexgenreecologiesinvolvedin cancelation (Section5)bothrequireandfacilitateforlight/thickgroupstocoalesce intohybrid,contingentgroups,aphenomenonthathasreceivedlessattention.

Inviewofwhathasjustbeendiscussed,itbecomesclearthatpragmatics/(im) politenessshouldnotobviatethetheoreticalandempiricalramificationsof intergroupcommunication.Acomplexsocio-cultural,collectivephenomenon suchas CC needstobeapproachedfromanequallycomplexmodelthatallows theanalystaholisticviewofitsrealizationsatthemacro/meso/micro-levels.I haveproposedthatFairclough’smodelprovidesthenecessarytoolsandcomplexitytotacklethistask.Moreimportantly,withitsinclusionofgenrepractices asmeso-levelunits,itisuniquelyequippedtopayattentiontointergroup communicationandgroupsingeneral,asthemeso-levelisthelevelofgroups, bothinthesenseofsomegenresmakingsocialidentities(andthusintergroup communication)salient(e.g.,ameetingbetweenabossandemployee)andalso inthesensethatsomegenrepracticescannotbefulfilledbyindividualsbutare unavoidablycollectiveandtiedtocollectiveintentionality.Afocusoncollectiveaction,asneededin cancelation,impliesscrutinizinghowthickandlight groupscometogetherwithacommongoal(orsetofgoals)thatrequiresthe deploymentofacomplex,contingentgenreecologytobringit/themtofruition. Notably,online cancelation micro-levelpracticeswillbescrutinizedtooffera rareglimpse(astheyhavebeenmostlyapproachedfromamacro-levelperspective)intohowlightgroupscoalesceandturnintogroupagents,thisbeing facilitatedbythenormativity,morality,andemotionsassociatedwithonline spaces,alongwiththeirdigitalaffordances.

Figure3 summarizes Sections2 and 3 andbringstogether Fairclough’s (2003) discourseinsocialpracticemodelandthesocialphenomenonhere underscrutiny: CC.

Bypayingcloseattentionto CC asasocio-culturalphenomenonandthe complexitiesofthreecasesof cancelation involving:CongresswomanLiz