PURPOSE AND POWER

US Grand Strategy from the Revolutionary Era to the Present

Donald Stoker

National Defense University, Washington, DC

Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge CB2 8EA, United Kingdom

One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, NY 10006, USA

477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia

314–321, 3rd Floor, Plot 3, Splendor Forum, Jasola District Centre, New Delhi – 110025, India

103 Penang Road, #05–06/07, Visioncrest Commercial, Singapore 238467

Cambridge University Press is part of Cambridge University Press & Assessment, a department of the University of Cambridge.

We share the University’s mission to contribute to society through the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence.

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781009257275

DOI: 10.1017/9781009257268

© Donald Stoker 2024

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press & Assessment.

First published 2024

Printed in the United Kingdom by TJ Books Limited, Padstow Cornwall

A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stoker, Donald, author.

Title: Purpose and power : US grand strategy from the revolutionary era to the present / Donald Stoker, National Defense University, Washington, DC.

Description: Cambridge ; New York, NY : Cambridge University Press, 2024. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022040999 | ISBN 9781009257275 (hardback) | ISBN 9781009257268 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: National security – United States – History. | United States – Military policy. | United States – Foreign relations. | United States -- Economic policy.

Classification: LCC UA23 .S818 2024 | DDC 355/.033573--dc23/eng/20230206

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022040999

ISBN 978-1-009-25727-5 Hardback

Cambridge University Press & Assessment has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

To Carol – Who Made It Possible

The Fight for Sovereignty, 1775–1801

Expansion, Sovereignty, and War, 1801–1817

3 Seeking a Continent: Expansion, Indian Removal, and the Mexican War, 1817–1849

4 Schism, Civil War, and Reconstruction, 1849–1877

5 Conquering a Continent: The Indian Wars, 1865–1897

Moving Astride the World: The Second World War, 1939–1945

The Hot Peace and the Korean War, 1945–1953

The Hot Peace: The Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson Years, 1953–1969

PART IV: RETREAT AND DEFEAT

Figures

0.1 A framework for strategic analysis page 2

12.1 North Vietnamese Army infiltration into South Vietnam, 1965–75 (in thousands) 421

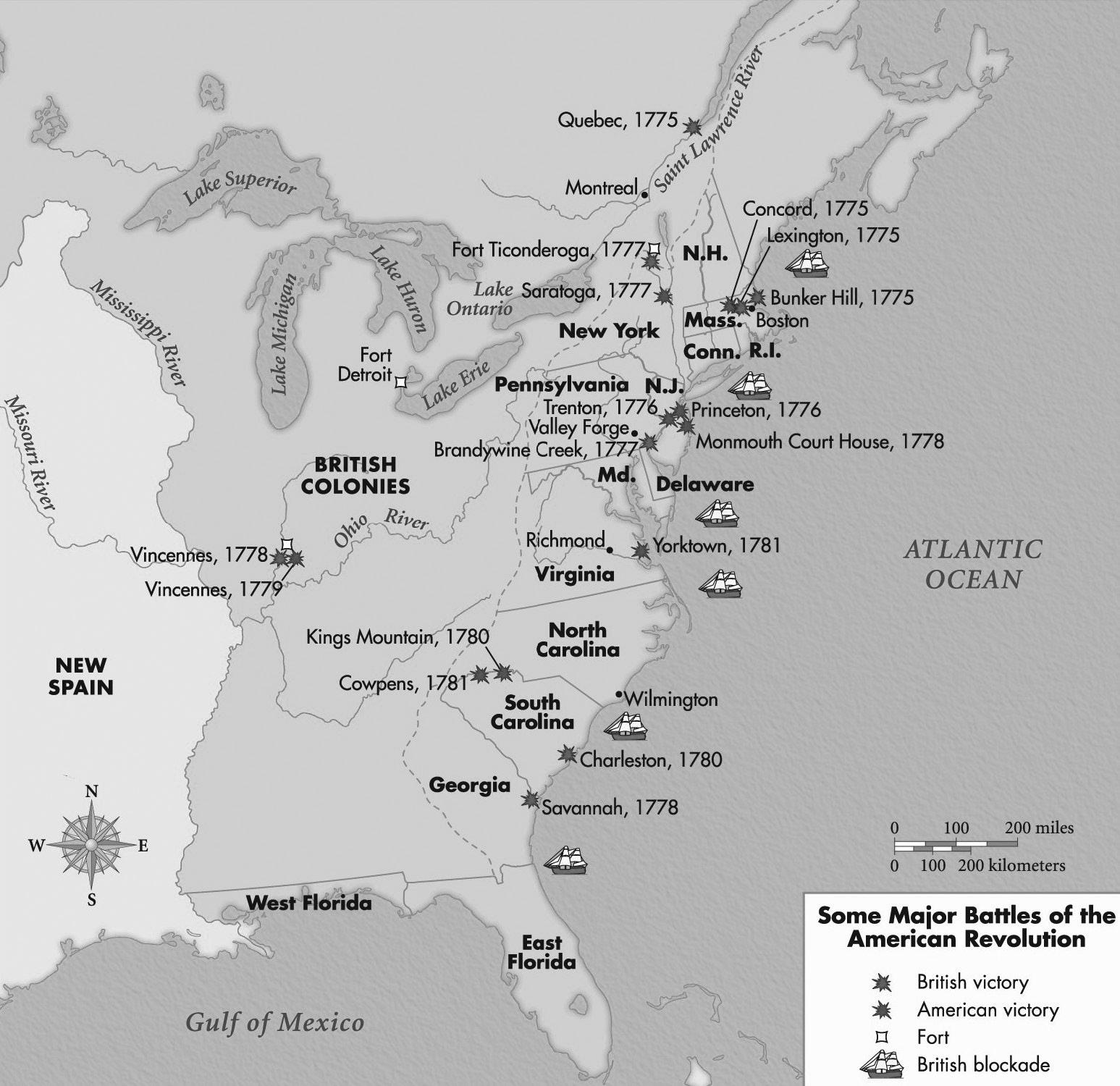

1.1 Principal battles of the American Revolutionary War, 1775–83. Universal Images Group North America LLC / Alamy page 14

2.1 An expanding country: US territorial acquisitions and growth 51

2.2 The Eastern United States, 1812 55

3.1 Florida and the Second Seminole War, 1835–42 93

3.2 The Mexican War, 1846–48 102

4.1 Principal campaigns of the American Civil War, 1861–65 123

5.1 The US army in the West, 1860–90 157

6.1 Santiago de Cuba and vicinity, 1898 193

6.2 Expansionism: The United States in the Spanish–American War, 1898–1902 194

7.1 The First World War, 1914–18 236

9.1a Major operations in Europe, 1939–45 295

9.1b Central Europe, 1944: Allied Occupation Zones 321

9.2a, 9.2b Pacific axes of advance, 1942–45 324

10.1 The Korean War, 1950–51 363

12.1 North and South Vietnam 441

16.1a, 16.1b Operation DESERT STORM, 1991 546

18.1 Major US operations, Afghanistan, 2001–02 593

18.2 Southern Iraq and vicinity, 2003 605 Maps

Abbreviations

AMH American Military History

B&L Battles and Leaders of the Civil War

CWL The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln

FRUS Foreign Relations of the United States

NYT New York Times

OR Official Records of the Civil War

ORN Official Records of the Civil War, Navy

ORS Official Records of the Civil War, Supplemental

PWR The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series

USGPO United States Government Printing Office

WSJ Wall Street Journal

WW The Writings of George Washington

THINKING ABOUT GRAND STRATEGY IN PEACE AND WAR

INTRODUCTION

On February 24, 2022, Vladimir Putin’s Russia escalated the war it began against Ukraine with its 2014 invasion of Crimea. This occurred at a time when tensions with China had increased as Beijing began openly seeking regional hegemony and to replace the United States as the world’s most powerful state. Totalitarian, revisionist states were on the march. “Greatpower competition” was back.

Will the United States emerge victorious from this new contest as it did during the Cold War? To do so, American leaders need to understand the purposes for which American power has been used and learn how to think about utilizing this power effectively. Examining the nation’s past actions – good and ill – is the best preparation for overcoming today’s challenges and tomorrow’s.

“WHAT SHOULD AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY BE?”

The advent of America’s post–Second World War rivalry with the Soviet Union moved “grand strategy” firmly into the US political-military lexicon. The latest wave of interest arose in the 2010s in the face of revisionist and expansionist Chinese and Russian regimes.

“What should American grand strategy be?” became a common query in political, defense, and academic circles.

But this is the wrong question.

Strategy is about the use of power. Grand strategy is the coordinated use of the various elements of national power. But to use power absent a political aim – and without understanding the effects of the aim or aims – is to flail, to expend at times both blood and treasure for no clear purpose. Proper analysis rests on asking “What is our aim? What do we want to achieve?” The political aim should be decided first. The wise use of power flows from this. Few works on grand strategy rest on such a solid foundation.1

The aim is the most important element in proper strategic analysis, but it is only a part. The first step is to learn how to think about the use of power and its purpose.

A FRAMEWORK FOR STRATEGIC ANALYSIS

Having a clear analytical approach is fundamental. (See Figure 0.1.) How we think about a challenge drives how we address it. Grand strategy works frequently conflate terms, confusing the aims being sought with the ways and means of achieving them and the underpinning interests. One critic of American grand strategy wrote: “Instead of pursuing a more restrained grand strategy, US leaders opted for liberal hegemony.”2 Grand strategies are implemented, political aims (such as hegemony) are pursued. This is more than a semantic problem: it is broken theory. This statement has the added weakness of being historically inaccurate, as no US administration has ever sought hegemony, and writers insisting upon this usually confuse war plans for addressing hypotheticals or the creation of regional military preponderance with a desire to achieve political dominance. Other works attempt encapsulation of American grand strategy in a single term. The urge is understandable as this could provide an instantly grasped concept,

A Framework for StrategicAnalysis

but America’s historical challenges are generally too complex for this.3 “Containment” in the Cold War comes the closest, one unsurpassed for branding success. But even this fails to paint a complete picture, nor was it meant to as it was initially directed at the Soviet Union. A critical examination of any topic requires a clear methodology based on solid definitions.

INTERESTS

We begin with interests. These are often issues relating to a state’s survival or prosperity. Interests depict part of the why and how of the behavior of state and nonstate actors and are often underpinned by ideas and values. Ideally, both become involved in issues because their leaders judge it necessary – in the interests, or national interests – of the state or organization. We must avoid confusing interests with political aims. Interests usually underpin why nations select certain political aims and drive the actions of leaders. But this is not an absolute; there are few absolutes in such matters.4 Some things can be both interests and aims, complicating the analytical problem. For example, it is in the interest of the United States to have security, but the security of the nation is also a political aim.

Interests can be subjective because leaders have different views and prejudices, they can vary over time as the international and domestic situations are in constant flux, and are sometimes determined by unique events. Administrations at times don’t see acting in some areas as in the US interest until a new threat arises. In 1950, fighting a war in Korea wasn’t viewed as in the American interest until Communist North Korea invaded non-Communist South Korea and threatened American credibility. Interests aren’t fixed and change as circumstances change. This can drive alteration of political aims, which means the grand strategy should be reassessed and changed where necessary to address the new environment.

How then do we determine what is in the nation’s interests? Interests, like so many aspects of foreign affairs, remain frustratingly subjective. Sometimes this is easy: countering a threat to the nation’s survival is clearly in the national interest. Sometimes this is difficult. Is it in the US interest to defend Taiwan against aggression from Beijing? Theorist Bernard Brodie wrote: “A sovereign nation determines for itself what its vital interests are (freedom to do so is what the term ‘sovereign’ means) and its leaders accomplish this exacting task largely by using their highly fallible and inevitably biased human judgment to interpret the external political environment.”5 Some advise ranking, but this suffers from subjectivism and sometimes poor judgment.6 As with so many things in politics and war, the answer depends

upon circumstances, the conditions under which the assessment is made, and the views and goals of the individuals performing the assessments and making the decisions. As elsewhere, as our graphic shows, risk is a factor.

Some argue that “a nation’s interests are determined by its power.” This is backward reasoning. A nation’s interests have little to do with its power, but power has everything to do with the achievement of its aims. The leaders of all states see regime survival as in the nation’s interest. But the nation may lack the power to assure it. President Abraham Lincoln decided it was in the country’s interest to resist secession despite the great costs, and mustered the power to suppress the rebellion.7 Interests should drive the creation of political aims, though this isn’t always the case.

AMERICA’S HISTORIC POLITICAL AIMS: SECURITY, SOVEREIGNTY, EXPANSION (AND DEMOCRACY)

Political aims provide a foundation for analysis and the point toward which a nation’s power is directed. Ideally, the aims being sought are rationally founded upon what is best for the state – or at least what the leaders decide is best. But there are potentially many aims – in peace and in war – and these change. Possessing multiple aims often means states need multiple grand strategies to achieve them, a challenge overlooked in most works on grand strategy. We see in American history predominant aims in particular eras. The pursuit of these leads to the formulation of additional aims (sometimes), which then, ideally, drive the development of different and multiple grand strategies (coordinated uses of power) for pursuing these disparate aims. This is not always clear or even systematic. But methodically examining past aims and related uses of power teaches future leaders and their advisors how to think critically while providing a historical foundation for crafting future aims and grand strategy.

From the time of their first settlements, the people who came to be called “Americans” sought security. For the infant United States, security became a critical political aim. Until the 1890s, Native American peoples constituted the most persistent though withering threat. Early settlers also worried about foreign intrusions, particularly from Spain and France. The danger of their destroying what became the United States evaporated with Britain’s victory in the French and Indian War in 1763. They remained a threat, though Britain became a greater one. The hazards evolved as the country grew, but the desire to achieve security has remained a dominant aim driving the creation of US grand strategy.

The second key political aim is sovereignty. Americans were first concerned with achieving sovereignty during their war for independence: they wanted to control their own affairs without interference from abroad. After achieving independence in 1783, securing sovereignty against external enemies, particularly the European powers, as well as the neighboring Native American nations, became important. America has also faced internal threats to sovereignty such as the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion, the Confederacy, and domestic organizations using terrorism. In each case, Federal power was wielded to defeat threats.

A third aim was expansion. Americans were land hungry from the beginning, and American expansion was dominated by taking land from Native American nations. This desire to expand underpinned wars against European powers and their former colonies as Americans enthusiastically sought British (Canadian), French, Spanish, and Mexican lands.

The American trinity of security, sovereignty, and expansion altered after President Theodore Roosevelt’s acquisition of what became the Panama Canal Zone in 1903. Afterward, the US no longer pursued territorial expansion using military force. Instead, the US added a new political aim toward which it directed power. “Security, Sovereignty, and Expansion” became “Security, Sovereignty, and Democracy.” The US would go abroad in search of monsters to slay. There were tinges of this in US foreign relations dating to Thomas Jefferson, but Woodrow Wilson made it a core political aim by weaponizing Progressivism to spread democracy.

All aims can produce troubles at home. Politics as a blood sport was present from the republic’s birth. A myth arising during the Cold War was “politics stops at the water’s edge,” meaning America’s political parties unite against a foreign danger. Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg, perhaps Congress’ foremost internationalist in his day, used the phrase to illustrate how he and Democratic president Harry Truman worked in a bipartisan fashion. Their relationship, even at the time, was “an aberration.”8 Bitter partisanship marked disagreements over the Quasi-War of 1798–1800 with France. American resistance to the War of 1812 reached full-fledged treason. The American Civil War marked the bloodiest partisan discord. Schisms over neutrality and preparedness for war prevented national political unity at the dawns of both world wars. Disagreement over the Vietnam War became noxious. In 2007, Democratic Senator Harry Reid enthused upon how Republican George W. Bush’s errors in Iraq would help Democrats win Senate seats.9 America’s foreign relations – especially its wars – have always provoked division.

IF AT WAR…

If not attacked, one of the most important decisions of American leaders is whether it’s in the nation’s interest to go to war. The nation’s chiefs should determine the political aim or aims before doing so, and if the US has been forced into a conflict, its leaders should quickly determine the political aims sought. The course for achieving them – the grand strategy – should follow. In the American experience, the aims generally involve some version of the quadrumvirate detailed above, but not always. There may be multiple political aims, and these can vary by opponent. Aims that are pursued via war can always be classified as two types: unlimited aims – meaning the overthrow of the enemy state, or limited aims – something short of regime change, such as seizing territory. The political aims and the planning associated with them should include a vision of the postwar situation and a peace treaty – when possible – as this is ideally a war’s final act.10

Critical to the decision regarding what political aims are being sought is an assessment of the situation to see whether the nation possesses the power to achieve the aims, or what resources must be mobilized or obtained to succeed, as well as the potential roles of other powers. A thorough appraisal can increase the chances of success or show that the aims need to change. Thucydides, the historian of the Peloponnesian War, observed: “It is a common mistake in going to war to begin at the wrong end, to act first, and wait for disaster to discuss the matter.”11

Prussian soldier and theorist Carl von Clausewitz cut a clear path for performing assessments, one useful in both peace and war:

we must first examine our own political aim and that of the enemy. [It is important to understand what the foe wants.] We must gauge the strength and situation of the opposing state. We must gauge the character and abilities of its government and people and do the same regarding our own. Finally, we must evaluate the political sympathies of other states and the effect the war may have on them.12

Clausewitz also had no illusions regarding the difficulty of doing this well. Ideally, reassessment should occur continuously despite the challenges of doing so. It should certainly take place whenever there is significant change, such as a battlefield victory or defeat or the entry of a third party into the war. Leaders should also decide how to bring the war to a victorious conclusion. The paths here are innumerable, but Clausewitz marks the dominant routes:

We can now see that in war many roads lead to success, and they do not all involve the enemy’s outright defeat. They range from the destruction of the

enemy’s forces, the conquest of his territory, to a temporary occupation or invasion, to projects with an immediate political purpose, and finally to passively awaiting the enemy’s attacks. Any one of these may be used to overcome the enemy’s will: the choice depends on circumstances.13

GRAND STRATEGY

The path for tapping American power to accomplish the desired aims –both in peace and in war – is grand strategy. Grand strategy – as a concept and a necessity – has its skeptics.14 The term has been with us since the early 1800s, but no common definition has emerged.15 Grand strategy is how nations use their power, ideally in a coordinated manner. This should be directed at specific political aims. Some works on grand strategy mix the political aim being sought with the strategy being pursued to obtain it, making the analytical error of not distinguishing between them.16 Others deem the political aim grand strategy.17 Some discuss the advantages of specific grand strategies, and then examine the nation’s interests and political aims.18 This places the grand strategy cart before the political horse. The elements of national power can be divided into four dominant realms: diplomatic, informational, military, and economic, which are sometimes represented by the acronym DIME. There are numerous additions made to this, finance, intelligence, and law (FIL) being the most common, but intelligence is part of the “I,” and other add-ons generally mark tools for implementing or “operationalizing” the DIME’s respective elements. Finance, for example, is an economic strategy tool, while law is part of all four. Grand strategy is not the end being sought but the course for getting there – the ways – that considers the necessary means.19 “National strategy” is sometimes used as a synonym.20 “Doctrine” often serves as another, but this also describes the methods military forces use to implement operations. Some insist grand strategy must necessarily be for the long term, an artificial requirement ignoring the reality of changing political aims and an international environment in perpetual flux. If the aims and situation change, the grand strategy might need to as well. Other artificial requirements include the insistence that grand strategy only applies to wartime and that small states can’t have one. All countries (and even non-state actors) can have a grand strategy, or even multiple grand strategies, as all nations have interests and threats, and these usually generate political aims. Different aims often require different utilizations of national power. The reality of the possession of multiple political aims, combined with how nations variously use their elements of national power, destroys a basic

conceit of much grand strategy literature: that a nation can simply pick a grand strategy that addresses all its strategic challenges. This mistake arises from analysis mistakenly rooted in the ways or means used to pursue an aim rather than the aim itself.

THE ELEMENTS OF GRAND STRATEGY

By beginning with the political aims, this book examines US diplomatic, informational, military, and economic strategies, though it emphasizes the diplomatic and military. US actions in any of these arenas are invariably intertwined with the others and cannot be adequately considered in isolation from one another or the political aims being sought. This provides a picture of how America has used its power and for what purposes.

DIPLOMATIC STRATEGY

In diplomatic strategy (or foreign affairs) the key question is: how has the US used its diplomatic power in pursuit of its political aims? There are, of course, many variables, but among the most important are alliance relations, interactions with friendly or partner nations, and dealings with rivals, bad actors, and enemies. When examining American debates over foreign affairs, one must also keep in mind the effects of domestic politics.21

A related myth is America’s supposed isolationist tradition, meaning that the United States sought at times to separate itself from the world and remains in danger of doing so again. The US has never done this. A trading nation from its inception, America has always engaged abroad. Trade, evangelism, immigration, and the currency of ideas characterized America’s internationalism from its founding. Its struggle for independence against Britain saw the nascent republic forge with France its first military alliance. What alarmed American statesmen was foreign entanglement. Don’t confuse reluctance to being dragged into Europe’s internecine struggles with burying one’s head in the international sand.22

The isolationist canard first appeared in the 1890s as an imperialist bludgeon used against political foes. One of its most important propagators was expansionist and naval theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan. Politicians and pundits continue Mahan’s approach. When President Bill Clinton failed to get his Nuclear Test Ban Treaty through the Senate, he claimed to see “signs of a new isolationism.” President George W. Bush, in defense of his war in Iraq, wrote in 2006: “We choose leadership over isolationism.”23 The period often deemed the most isolationist – the years between the world wars – were marked by particularly intense US action abroad. America has

always been involved with the world beyond – both in peace and in war. What follows makes this clear.

INFORMATION STRATEGY

The information realm can be viewed as a stool with four legs: ideas (which can include values), intelligence, strategic communication or propaganda, and public affairs or public information. The ideas underpinning America – liberty, personal freedom, democracy, and others – are critical for motivating Americans and telling the nation’s story abroad. Intelligence is key for understanding others and threats. Strategic communication (propaganda is what other states do) is usually directed at competitors. Public affairs efforts, which are often aimed internally, provide information on the nation’s activities. The latter two are sometimes branded narrative creation. Having the world see the picture we wish to present – not that painted by enemies – is important for the preservation of American freedoms at home, and the building and maintenance of respect for them abroad. It is also a tool for achieving the political ends that secure US interests. So-called “soft power” is a nebulous form of influence difficult to wield in the pursuit of political aims.24 Information strategy is inextricably tied to diplomacy.

MILITARY STRATEGY

Much of US grand strategy has been driven by preparation for war, waging it, and its aftermath. It is a myth to think Americans historically rejected Clausewitz’s dictum that war is a political tool used in pursuit of the nation’s aims.25 The key question here: how has the US used its military power – in peace and in war (in war one uses military force) – to achieve its political aims? This, of course, has many facets, all based upon the circumstances and the aims being pursued. We also consider the ideas driving the development and application of American military power. Military strategy is exemplified by such things as attrition and simultaneous pressure, and is “the link between military means and political ends, the scheme for how to make one produce the other.”26 Plans and strategy are not the same. War plans are the tools by which nations execute strategy.27

It is impossible to talk about an “American way of war.” First, Americans were originally Europeans, predominantly English, and derived their warfighting methods from a European military heritage. Second, Americans have always absorbed warfighting ideas and techniques from other places, just like everyone else. Adaptation is a hallmark of military learning. Third, war has a certain perverse logic no matter who is fighting.28 Examples of

American tactical innovation, which are generally the basis of such arguments, demonstrate not a uniquely American way of war but tactical innovation.

ECONOMIC STRATEGY

So much of America’s power, particularly since the 1890s, derives from and rests upon American economic strength. Preserving and strengthening America’s economic situation is critical and a perennial presidential concern. Domestic industrial and raw material production, foreign trade, technology investment, and infrastructure construction are among the key economic activities. The important question: how has the US developed and used its economic power in pursuit of its political aims?

A related myth is that the US became a great power because of dedication to free trade. The truth is more complex. George Washington and Alexander Hamilton supported tariffs to protect nascent American industries – particularly those important to national defense. In the late 1800s, “a protectionist America and a protectionist Germany both outperformed free trade Britain.” “Free trade does not assure prosperity,” historian Alfred Eckes wrote, “nor does protectionism automatically produce ruin.”29 Economic power is a critical tool of grand strategy. But economic conditions and connections remain in constant flux. Grasping what has worked, when, and under what circumstances is critically important. Another myth among critics of US foreign relations is that America goes to war for economic reasons. Supporters of American intervention abroad have rarely pushed for action because of economic motivations, though their opponents generally accuse them of it. Other reasons weighed more heavily, particularly during the Cold War when credibility and maintaining commitments influenced US involvement in Korea, Vietnam, and other parts of what was then called the Third World. Developing states were never significant markets for US exports, which have gone overwhelmingly to developed nations. Washington certainly promotes foreign US business interests and has sometimes protected them with force, but US leaders rarely voice such things publicly from a fear of eliciting opposition from the American public, which exhibits an amusing schadenfreude toward the overseas business losses of wealthy Americans.30 Economic sanctions, such as those placed upon Russia in 2022 because of its war against Ukraine, can fall into this realm, though they are inextricably tied to diplomacy.

ASSEMBLING THE PARTS

Ideally, the grand strategy realms work together in harness in pursuit of the aims. But this isn’t always the case as sometimes administrations lack clear political aims and provide little guidance. The American machine of state then runs on its own. At other times there are clear aims and firm direction. Deciding these aims, and constructing coherent grand strategies for achieving them, demands leaders who are educated to think creatively and in a disciplined manner about the uses of American power and the purposes toward which it should be directed. Where do the nation’s interests lie? How do we decide this? What should be achieved? How can American power be used to do this? What are the risks of action or inaction? What are the rewards? What, in the end, do we want the future America to look like? And what should be its role in the world?31

A FINAL WORD BEFORE WE BEGIN…

It would be incorrect to insist the US has always possessed a grand strategy or developed clear strategic paths. It’s equally false to say it never has. Some may find it surprising that although past American leaders didn’t always use terms recognizable to us or define their actions in the same manner, they thought and acted in ways familiar to and often more coherent than what we see today. The framework provided here is useful for analyzing the actions of any nation. I have applied it to the United States to paint a clearer picture of the nation’s aims and strategic history. I hope it will teach readers how to think about political aims and grand strategy. We begin by examining America’s first efforts to use its power.

PART I FROM BACKWATER TO GREAT POWER

Map 1.1 Principal battles of the American Revolutionary War, 1775–83. Universal Images Group North America LLC / Alamy.

THE FIGHT FOR SOVEREIGNTY, 1775–1801

THE INSURRECTIONISTS

America’s founders were insurrectionists, rebels against the greatest imperial overlord of their age. The Americans, like most rebels, were weak and initially bereft of diplomatic, military, or economic power. But in the informational realm, the Americans had something of immense value – a powerful, infectious idea.

THE ORIGINS OF THE WAR FOR AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, 1776–83

The most important Colonial idea was that the Americans should have a say in ruling themselves. Britain had long practiced “salutary neglect” toward the colonies, but 1763’s conclusion of the French and Indian War (or Seven Years’ War) left a victorious but indebted Britain eager to right its fiscal ship via a once traditional means: taxation. London expected its subjects to do their duty, including those in America, a demand made after Britain took France’s Canadian lands, removing the primary threat to American security. The drive for a common response knit together thirteen colonies.1

Britain’s Parliament passed the Sugar Act in April 1764, reducing the molasses tax by half, but this half London intended to collect. The Americans’ reply was novel: Parliament had no right to tax them because the colonists hadn’t elected any of its members. March 1765’s Stamp Act imposed a levy on anything the Colonials printed. Opposition groups known as the Sons of Liberty formed; a protest petition followed. Parliament dropped the Stamp Act but insisted upon its authority over the colonies. The 1767 Townshend Acts followed, taxing imports such as tea, paint, and glass, and feeding the Colonial political awakening. Riots and protests produced tragedies like the 1770 Boston “Massacre,” while Pennsylvanian John Dickinson argued the colonists could only be taxed by assemblies they elected. Parliament eventually repealed the taxes – except that on tea.2

On December 16, 1773, Americans dressed as Indians famously staged the Boston Tea Party by dumping tea into the harbor. Parliament acted against growing Colonial lawlessness by closing Boston harbor pending restitution, occupying the city, and suspending Massachusetts’ government. The colonists replied with Philadelphia’s September 1774 Continental Congress. It branded British actions the “Intolerable Acts,” dispatched a petition listing thirteen grievances, and used trade as a weapon for the first time by halting British imports and restricting American exports. Colonial committees formed to enforce Congress’ rulings began seizing local reins of power, including over the militia. The British attempted conciliation. The colonists prepared for war by stealing British gunpowder and stockpiling military supplies.3

Under the direction of Lord Frederick North, first minister to the king and head of government, Parliament declared Massachusetts in rebellion on February 9, 1775, ordered its leaders arrested and Colonial arsenals seized, and authorized Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, Massachusetts’ military governor, to use force to reassert control. On April 18, 1775, Gage dispatched 800 soldiers from Boston to seize powder and weapons stored at a village named Concord. American militia assembled on the green at Lexington blocked their advance. A firefight ensued from which the Americans fled. Another skirmish at Concord followed. On their return march to Boston, the British endured numerous, uncoordinated attacks from Colonial militia (who proved exceptionally poor marksmen) and retaliated by looting the homes of suspected attackers and killing the occupants. The Americans put their version of events on a fast ship and had it to the London newspapers two weeks before the British government received Gage’s report.4

The violence enflamed the Americans, who overthrew the Royal governors in the lower thirteen colonies. Even in areas where they were a minority, the insurrectionists seized control.5

AN INSURRECTION LIKE NO OTHER

America first learned to use its power – slight though it was – in war’s crucible. That the War for American Independence began as an insurrection shaped its nature. It also became a revolutionary struggle as the Americans sought to rule themselves in a manner and on a scale not attempted since ancient Rome. But doing this required the revolt succeed. Insurrections generally hinge upon three factors: the support of the people; the control of internal or external insurgent sanctuary; and whether the rebels have outside aid.

THE POLITICAL AIMS

At the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, its members disagreed upon the fundamental issue: for what purpose were the Americans fighting? The core dispute: should they pursue reconciliation or independence? Moderates wanted “redress of grievances.” Radicals wanted independence but balked at open advocation; public opinion sat not in their camp. Congress adopted Jefferson’s Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms. It listed American grievances, expressed loyalty to the Crown, and insisted upon self-government but not independence. The key complaint: Parliament’s insistence it could “of right make Laws to bind us in all Cases whatsoever.” The colonists fought not for independence, but “in defence of the Freedom that is our Birthright.”6

Congress declared a trade embargo, created a Continental Army in June 1775 and navy in October, improved the militia, raised defense funds, and, in November, a committee to communicate with European states. Congress believed Canada should be part of “the American union” and wanted control over the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and Mississippi River. Its actions and expansionist territorial aims didn’t align with seeking “redress of grievances.”7

To Britain, the value of the object was high. London insisted the rebels recognize Parliament’s supremacy and right to rule; the shape of British constitutionalism was at stake. King George III and others saw the American lands as the Empire’s jewel and believed losing them threatened national survival. On August 23, 1775, London issued a Proclamation of Rebellion. It forbade all trade with the rebellious colonies and allowed the capture of American ships, but London never abandoned efforts to craft a political solution.8

The conflict established one of the great traditions of American grand strategy: entering a war unprepared. Here, the Americans had little choice, but it took the nation’s leaders generations to correct this. When the war began, America possessed neither army nor navy. Each state had a regulated militia, but preparation varied, and their appearance when summoned was as unpredictable as their performance in battle. The presence of Continental Army troops usually helped both, but, if not used quickly, militia often went home.9 The seafaring Americans also had an enormous merchant fleet.

ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

When fighting began, 2.5 million people lived in the thirteen colonies. (See Map 1.1.) Perhaps 15 to 20 percent were Loyalists. Others were