SCIENTIFICMODELS ANDDECISION-MAKING

EricWinsberg

UniversityofCambridge andUniversityofSouthFlorida

StephanieHarvard

TheUniversityofBritishColumbia

ShaftesburyRoad,CambridgeCB28EA,UnitedKingdom OneLibertyPlaza,20thFloor,NewYork,NY10006,USA 477WilliamstownRoad,PortMelbourne,VIC3207,Australia

314–321,3rdFloor,Plot3,SplendorForum,JasolaDistrictCentre, NewDelhi – 110025,India

103PenangRoad,#05–06/07,VisioncrestCommercial,Singapore238467

CambridgeUniversityPressispartofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment, adepartmentoftheUniversityofCambridge.

WesharetheUniversity’smissiontocontributetosocietythroughthepursuitof education,learningandresearchatthehighestinternationallevelsofexcellence.

www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle: www.cambridge.org/9781009468213

DOI: 10.1017/9781009029346

©EricWinsbergandStephanieHarvard2024

Thispublicationisincopyright.Subjecttostatutoryexceptionandtotheprovisions ofrelevantcollectivelicensingagreements,noreproductionofanypartmaytake placewithoutthewrittenpermissionofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment.

Whencitingthiswork,pleaseincludeareferencetotheDOI 10.1017/9781009029346

Firstpublished2024

AcataloguerecordforthispublicationisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary.

ISBN978-1-009-46821-3Hardback

ISBN978-1-009-01432-8Paperback

ISSN2517-7273(online)

ISSN2517-7265(print)

CambridgeUniversityPress&Assessmenthasnoresponsibilityforthepersistence oraccuracyofURLsforexternalorthird-partyinternetwebsitesreferredtointhis publicationanddoesnotguaranteethatanycontentonsuchwebsitesis,orwill remain,accurateorappropriate.

ElementsinthePhilosophyofScience

DOI:10.1017/9781009029346

Firstpublishedonline:January2024

EricWinsberg UniversityofCambridgeandUniversityofSouthFlorida

StephanieHarvard

TheUniversityofBritishColumbia

Authorforcorrespondence: EricWinsberg, winsberg@usf.edu

Abstract: ThisElementintroducesthephilosophicalliteratureon models,withanemphasisonnormativeconsiderationsrelevantto modelsfordecision-making.Section1givesanoverviewofcore questionsinthephilosophyofmodelling.Section2examinesthe conceptofmodeladequacyforpurpose,usingthreeexamplesof modelsfromtheatmosphericsciencestodescribehowthissortof adequacyisdeterminedinpractice.Section3exploresthesignificance ofusingmodelsthatarenotadequateforpurpose,includingthe purposeofinformingpublicdecisions.Section4providesabasic frameworkforvaluesinmodelling,usingacasestudytohighlightthe ethicalchallengeswhenbuildingmodelsfordecision-making.The Elementconcludesbyestablishingtheneedforstrategiesto managevaluejudgementsinmodelling,includingthepotentialfor publicparticipationintheprocess.

Keywords: models,climate,decision-making,Covid-19,philosophy

©EricWinsbergandStephanieHarvard2024

ISBNs:9781009468213(HB),9781009014328(PB),9781009029346(OC)

ISSNs:2517-7273(online),2517-7265(print)

1Introduction

1.1WhatIsaModel?

Ifthereisanythingthatcouldbedescribedasacorequestioninthephilosophy ofmodellinginscience,itisprobably Whatisamodel?Unfortunately,this questionisdeceptivelycomplex:aswewillsee,itistangledupwithnumerous otherkeyquestionsinthisbranchofphilosophy.Butsincewehavetostart somewhere,let’sgiveitashot:what is amodel?Here’sashortlistofexamples ofthingsscientistscallmodels:

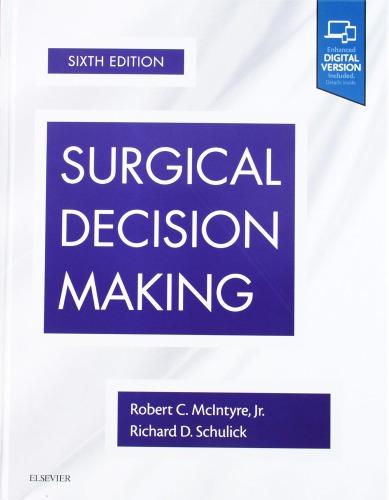

(1)A ‘typical’ drawingofacellinabiologytextbook,showingthecellto containanucleus,acellmembrane,aGolgibody,mitochondria,and endoplasmicreticulum(Downes1992)(Figure1).

(2)Thestandardlaboratoryrat, Rattusnorvegicus,depictedin Figure2,is amodelorganismwhichisstudiedwiththegoalofunderstandingarange ofbiologicalphenomena,includinghumans(AnkenyandLeonelli2021, chap.2; Leonelli2010; LevyandCurrie2015).

(3)Thesolarsystem,usedbyNielsBohrintheearlytwentiethcenturyasamodel oftheatom.BohrarguedthatthenucleusofanatomisliketheSun,the electronslikeplanetscirclingtheSun(Giere,Bickle,andMauldin1979).

(4)TheFriedmann–Lemaître –Robertson–Walkermodelsofcosmologyand thestandardmodelofparticlephysics.Theformerisawayofpickingout aparticularsetofconditionsthatsatisfiestheequationsofthetheoryof generalrelativity;thelatterameansof fleshingoutthemathematical frameworkprovidedbyquantum fieldtheory(Redhead1980; Smeenk 2020).Thisideaofascientificmodelbearingtherelationtotheorythat amodelbearstoasetofaxiomsinlogicgoesbackto MaryHesse(1967).

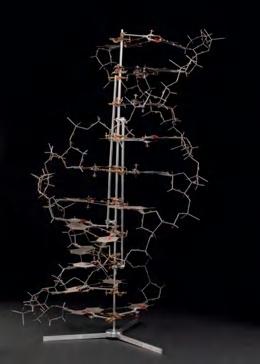

(5)WatsonandCrick’sfamousdouble-helixmodels,builtfrompiecesofwire andtinplates(depictedin Figure3)andultimatelytakentorepresentthe structureofDNA(Giere,Bickle,andMauldin1979,16–29).

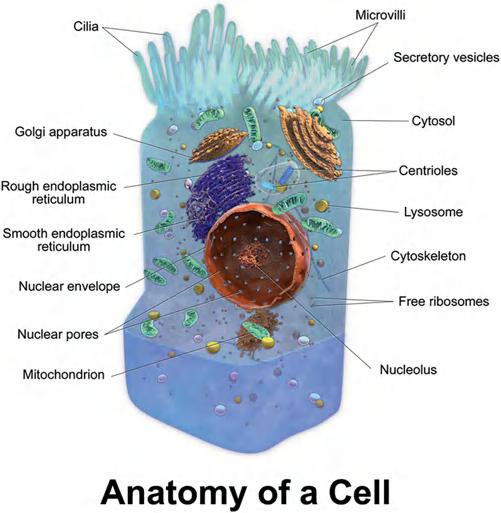

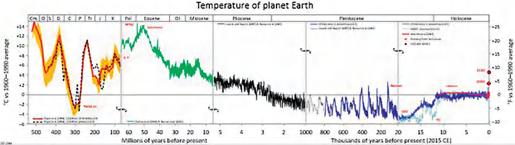

(6)AmodelreconstructionoftheEarth’stemperatureinpastgeological periods,developedusingproxydatafromsourceslikedeepicecores, fossilizedshells,treerings,corals,lakesediments,andboreholes(Parker 2018; Winsberg2018,chap.2).Anexampleofthisisdepictedin Figure4.

(7)TheSanFranciscoBaymodel,depictedin Figure5 – madeofconcrete, repletewithpumps,and filledwithsaltwaterwheninoperation – usedto simulatethebehaviourofwaterintherealSanFranciscoBay.TheArmy CorpsofEngineersconstructedthemodelinthe1950stopredictthe effectsofaproposaltocloseofftheGoldenGateandturntheBayinto afreshwaterreservoir(Weisberg2013).

Figure1 Amodelofaplantcell.

Source: www.pinterest.ca/pin/plant-cell-vs-animal-cell-whats-the-difference–533746 993338085307/

Amodelorganism,thewhitelabrat.

Source: Williams(2011)

Figure2

Figure3 WatsonandCrick’stinplatemodel.

Source: https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co146411/crick-andwatsons-dna-molecular-model-molecular-model

Figure4 SeveraldifferentmodelsoftheEarth’spaleoclimate,presented asonehistory.

Source: GlenFergus,CCBY-SA3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid= 31736468

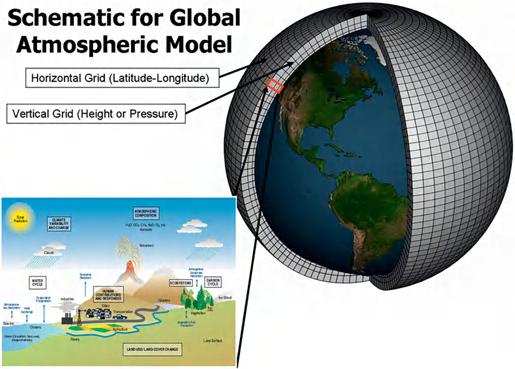

(8)Weatherandclimatemodelsthatrunoncomputers(anexampleis depictedin Figure6),whichareusedtomake predictions aboutactual short-termweatherconditionsand projections aboutpossiblelong-term climateconditionsunderdifferentCO2 emissionsscenarios(Parker2018; Winsberg2018).

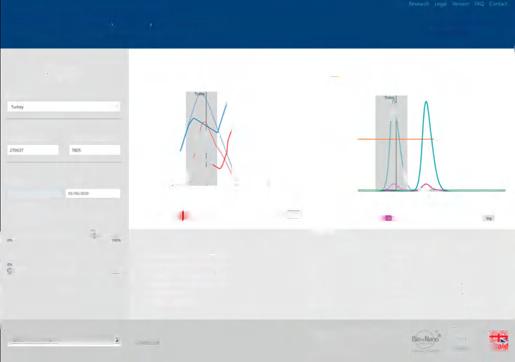

(9)Epidemiologicalmodelsthatforecastorexplainthespreadofaninfectious disease(WinsbergandHarvard2022).Anexampleisshownin Figure7.

Figure5 TheSanFranciscoBaymodel.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30086231

Figure6 Aglobalclimatemodel.

Source: www.gfdl.noaa.gov/climate-modeling/.

Figure7 AmodelrunoftheImperialCollegeLondonCovid-19 model ‘Covidsim’ .

Source: https://covidsim.org

(10)Health-economicdecisionmodels,whichcomparethecostsandconsequencesofimplementingdifferenthealthcareprogrammes,interventions, ortechnologies(Briggs,Sculpher,andClaxton2006).

Onethingthatisnoticeableaboutthislististhatitisextremelyheterogeneous. Take,tobeginwith,thestandardmodelsofcosmologyandparticlephysics:while theyareverycommonlycalledmodels,theyarereallycomplementstophysical theories.Comparethesetoclimatemodelsandepidemiologicalmodels:although theconstructionofthesemodelsisinpart guidedbytheory,theyaremorelike stand-alonebitsof mathematics.WithregardtotheSanFranciscoBaymodeland WatsonandCrick’sdouble-helixmodels,theseare actualphysicalentities,which were built byhumansforscientificpurposes.Thestandardlaboratoryratis avarietyofabiologicalspecies bred byhumansforthesepurposes,whilethe solarsystemisa foundobject thatBohrusedtoarticulatehisconceptionofwhat theatomlookedlike.And,unlikethesephysicalentities,areconstructedrecordof theEarth’stemperatureinapastgeologicalperiodisa datamodel (Bailer-Jones 2009; Bokulich2011; Hartmann1995; Laymon1982; Leonelli2016, 2019; Mayo1996, 2018; Suppes1962,2007): ‘acorrected,rectified,regimented, andinmanyinstancesidealizedversionofthedatawegainfromimmediate observation,theso-calledrawdata’ (FriggandHartmann2012).

Infact,ourshort,yetextremelyheterogeneouslistofmodelsreflectsakey sourceofconfusionaboutmodels: thereisverylittleonecansayaboutscientific modelsthatwillbegenerallytrueofallofthem.InthisElement,insteadof tryingtoworkourwaythroughthisconfusion,ourplanistolivewithit,sowe canfocusonotherissues.Inthissection,wewillsimplyzeroinonafew featuresthat many modelshave,sowecanlaterexplorehowthosefeaturesare importantforunderstandingphilosophicalissuesthatariseinconnectionwith certainmodels – especiallythosethatplayaroleinhelpingpolicy-makersto craftpoliciesthataffectusall.

Thereisonemoresourceofconfusionthatwemustaddressbeforewemove on.Thisistheratherhaphazardwayinwhichordinarylanguageuseinscience invokesafamoustriadofterms: model , theory,and experiment .Aswenoted, the ‘ standardmodelofparticlephysics’ isreallyapartoftheory – butis atheorydifferentfromamodel?Thisisfarfromclear,especiallysincewhen wetalkaboutourbest theories ofhowdiseasesspreadorofhowturbulence arises,whatwearereallytalkingaboutarethingsthatinvolve modelling . Furthermore,thereisaninfl uentiallineofthoughtinphilosophyofscience thatassertsthattheoriesarenothingmorethanfamiliesofmodels(Suppes 1960; Suppe1972 ; vanFraassen1980).Nancy Cartwright(1983, 1989) arguesthattheoriesareincompletewithoutaccompanyingmodels – models areinvolvedwheneveramathematicaltheoryisappliedtotherealworld. Finally,experimentsareoftendescribedasbeingcarriedoutundera ‘model ’ ofwhattheexperimentalsystemisandhowitismanipulatedinthelaboratory (Suppes1969 ).

Inlightofthis,howcanwepossiblydistinguishbetweenatheory,amodel, andanexperiment?Infact,attemptingtodrawthelinebetweenthesehas beenacentralactivityinthephilosophyofmodellingformanydecades.For thepurposeofthisElement,however,itwillsuf fi cetoemployaverysimple distinctionbetweentheory,model,andexperiment.Here,wetaketheword ‘ theory ’ tomeanaparticularlywell-su pported,widely-respected,and successful – inotherwords, well-credentialled – wayofunderstandinghow theworldworks(wewillsetasidethequestionofwhethersuchanentity comprisesafamilyofmo dels,asyntacticstructure,orwhateverelse( Suppe 1972 )).Incomparison,modelsandexperimentscanbemoreorlesswellcredentialled;thatis,neitherterm fl agsaparticularlevelofepistemicsupport orrecordofsuccess.Withregardtothedifferencebetweenmodelsand experiments,wewillnotdrawanyparticulardistinctioninthisElement: wesimplyusetheword ‘ modelling ’ toconveyascienti fi cprocesscarriedout eitherwithpaperandpenciloronacomputer,andtheword ‘ experiment ’ to conveyascienti fi cprocess,thecanonicalformofwhichtakesplacein

alaboratorybypokingandproddingat asampleofthekindofsystemthatis ofinterest.

Withthatsaid,let ’sbeginbyzeroinginonthreefeaturesthatmanymodels have.First,modelsarealmostalwaysintegratedintoa triad .Inotherwords, whenwetalkaboutmodelling,wearealmostalwaysreferringtothree things:(1)asystemorotherphenomenonintheworld,whichwecallthe target ;(2)themodelitself,which represents thetarget(moreonthisshortly); and(3)themodel user.Thesethreethingsmustbeunderstoodinrelationto eachother:inparticular,themodelusercannotbeignoredbecauseitisher intentions thatultimatelydeterminethemodel ’stargetsystemandthe model ’spurpose.Inotherwords,modelsareonlyrepresentationsoftheir targetsystemsbecauseamodelusersaystheyare.Forexample,thesolar systemhasbeenaroundforbillionsofyears – butitonlybecameamodelthat representsthetargetsystem ‘ theatom ’ whenahumanagent,NielsBohr, singleditoutandsaid ‘ that ’samodeloftheatom ’ .Similarly,aparticular computermodelhasthecognitivefunctionofpredictingtheweathertomorrowratherthanofprojectingtheclimateattheendofthecenturybecauseits usersaysso.Indeed,amodelonlyhasacognitivefunctionatall,ratherthan thefunctionofbeingavideoinstallationinanartmuseum,becauseitsuser saysso.

Second,asnoted,modelsarealmostalways representations oftarget systems.Whatexactlyitmeansforsomethingtobeascienti fi crepresentationisanothercoreareaofinquiryin philosophyofmodelling,witharich literaturethatwewillnotreviewhere( FriggandNguyen2021 ).Forour purposes,itwillsuf fi cetosaythatamodel represents atargetsystemif amodelusertakesittostandforthattargetsysteminawaythathelpsthe modeluserreasonaboutthatsystem( MorganandMorrison1999 ; Morrison 1999 ); R.I.G.Hughes ’ (1997 ) ‘ Denotation – Demonstration – Interpretation ’ accountofmodellingisespeciallyusefulhere.Somehaveevenarguedthat thereisakindofuseofmodelsalongtheselinesthatgivesrisetoitsown styleof ‘ model-basedreasoning ’ ( Magnani,Nersessian,andThagard1999 ; Knuuttila2005 , 2011 ; MagnaniandNersessian2002 ; Peschard2011 )in which ‘ inferencesaremadebymeansofcreatingmodelsandmanipulating, adaptingandevaluatingthem ’ ( Nersessian2010 ,quotedin Friggand Hartmann2012 ).

Furthermore,becausemodelsarerepresentationsoftargetsystems – not perfectlycompleteandentirelyaccuratedepictionsofthosesystems – the modellingprocessinvolvespragmaticchoicesaboutwhattorepresentand howtorepresentit,whichwecall representationaldecisions (Harvardand Winsberg2022 ).Awell-wornanalogyisusefulatthispoint:modelsarelike

maps.Thinkaboutasubwaymap:thechoicesthatgointohowtorepresentthe worldinasubwaymaphaveagreatdealtodowithhowthemapwillbeused. Thepurposeofasubwaymapistohelppeople fi gureouthowtogetfrom stationAtostationB(‘ Isthereasinglelinethattakesmethere?AmIgoingto havetomakechangesalongtheway?’).So,asubwaymapisdesignedto representthefeaturesoftheworldthataresalienttobeingabletodecidehow togetfrompointAtopointB.Subwaymapusersdon’tparticularlycarehow farthedifferentstopsarefromeachother,nordotheycareifthepathbetween twostopsisastraightlineorifthesubwaytakesacurvedpathtoget somewhere.Thekeytomakingagoodsubwaymapiscarefullychoosing themostusefulinformationtorepresentandusingrepresentationalconventionsthat,together,makeitaseasyaspossibleforuserstoreasonaboutand identifythebestwaytogetfromAtoB.

Modelsarealotlikethis.Likemaps,theyarethingsthatwebuildto representtheworldandtohelpusreasonaboutit.Andtheyrefl ect choices abouthowtorepresenttheworld:modeldevelopersdecide ‘ we ’ regoingto includethis,we ’ re not goingtoincludethat ’ .ThinkofWatsonandCrick ’stin plateandwiremodelofDNA.Itwasveryimportantforthemtorepresent,in theirmodel,thelengthofthefournitrogen-containingnucleobases(cytosine (C),guanine(G),adenine(A),andthymine(T)),butnottheirinternal molecularstructure.Thatisbecausetheyweretryingtoreasonabouthow thesefournucleobasescould fi ttogetherlikeapuzzle.Sotheyuseda(3D) puzzle-piece– likerepresentationaltoolkittobuildthemodelandtohelpthem dothatreasoning.

Thisbringsustoourthirdextremel yimportantfeatureofmanymodels. Theircriterionofadequacyismostoftennotthattheyare ‘true ’ totheworld.It isnotanimportantcriticismofasubwaymapthattheBroadwayline ‘isn ’t reallyorange’,orthatthemapdoesn ’tshowthatsomesubwaylinescross bodiesofwaterbygoingunderthemintunnelswhileothersgooverthemon bridges.Yetit would beanimportantcriticismofasubwaymapifitwereto representtwonearbystationsbytheexactsamedotonthemap.Afterall,this wouldmakeusersthinktheycouldchangelinesatthatstopwithoutleaving thesystem,andavoidingthiskindofmistakeiswhatsubwaymapsare supposedtofacilitate.Partofasubwaymap ’sintendedpurposeistohelp usersmakeaccurateinferencesaboutwhereandhowtochangesubwaylines. Withmodels,aswithmaps,thecriterionofadequacyisthattheyaregood enoughforthepurposesweintendtousethemfor.Sometimesmeetingcertain purposesrequiresthattherepresentationalrelationshipbetweenthemodel(or map)andtheworldisverisimilitude.Butoftenitdoesnot.Andadequacyfor purposeisthetelosofamodelandamap,nottruth.

Whetherornotthisfactaboutmodels,alongwiththefactthatmodelsvery ofteninvolvedeliberatedistortions,posesathreattoscientificrealismisatopic ofmuchphilosophicaldebate.Thethreatmightarise(accordingtothedebate)if oneassumes,asmanyphilosophersdo,thatscienceisfundamentallyamodelbasedactivity(mostfamouslyNancyCartwright(Cartwright1983, 1989, 2019),RonaldGiere(Giere1988, 1999, 2006; Giere,Bickle,andMauldin 1979),andMargaretMorrison(MorganandMorrison1999; Morrison1999, 2000, 2005, 2009)).1

1.2AreThere ‘ Types’ ofModels?

Givenalloftheabove,itisnotsurprisingthatphilosophershavemadevarious attemptstoclassifymodelsinto types.Someoftheseclassificationattempts havecorrespondedtokeyquestionslike ‘Howdoesthemodelrepresent?’ and ‘Whatisthemodel’scognitivefunction?’.Partlybecauseitisacloselyrelated question,andpartlybecausephilosophersarealwaysfascinatedbyontological questions,thequestion ‘Whatkindofentityisamodel?’ oftenalsoplays acentralroleinclassificationsofmodels.Wewillnotexplorehereallthe philosophicalattemptstoclassifymodels(see,especially, FriggandHartmann (2012) and Weisberg(2013) ifthisisofinterest).However,thefollowingrough divisionofmodelsintofourcategorieswillbehelpfulintyingtogethersomeof thecentralissuesthatconcernusinthisElement.Weshouldemphasizethatnot everyonewill findthiscategorizationschemeadequate,especiallyreaderswho areconcernedwithunderstandingthemostheterogeneouslistsofmodels.

1.2.1Abstract/MentalModels

Considerourvery firstexampleofsomethingscientistscallamodel:apictureof acellinabiologytextbook.ThiswhatStephen Downes(1992) hascalledan ‘idealized’ exemplar.AsDownesnotes,textbookswillpresentaschematized cellthatcontainsitemsofinterest:inabotanytextbooktheschematizedcell willcontainchloroplastsandanoutercellwall,butinazoologytextbookthe schematizedcellwillnotincludethosethings(1992,145).AsDownesputsit, ‘thecellisamodelinalargegroupofinterrelatedmodelsthatenableusto understandtheoperationsofallcells.Themodelisnotanervecell,norisit amusclecell,norapancreaticcell,itstandsforallofthese’ (1992,145).Aswe willsee,abstract/mentalmodelshavemuchincommonwithournextcategory

1 Foradiscussionofwhetherafundamentallymodel-basedconceptionofscienceiscompatible withscientificrealism,see section5.1 of FriggandHartmann(2012) andreferencestherein, especially Hartmann(1998); Laymon(1985); Massimi(2018a, 2018b); Morrison(2000); Saatsi (2016);and Teller(2018).

ofmodels, concretemodels.However,oneimportantdifferenceshouldbe emphasized.Makinginferencesfromabstract/mentalmodelsrequiresmodel userstohaveanimplicitunderstandingofthetargetsystemthatallowsthemto dosomethingakintomentallysimulatingitsbehaviour.Unliketheconcrete modelswedescribenext,abstract/mentalmodels,likeasimpledrawingof acell, donotmechanicallygeneratetheirownbehaviour

1.2.2ConcreteModels

SomeexamplesofconcretemodelsfromourintroductorylistaretheSan FranciscoBaymodel,thesolarsystemasamodeloftheatom,andthelaboratory ratasamodelofbiologicalphenomenainhumans.Whatseemstobespecial aboutconcretemodelsisthattheycomewiththeirowndynamicalbehaviour and theyrepresentandsupportdynamicalinferencesbypurportingtobeacausal duplicateofthetargetsystem.Forexample,theSanFranciscoBaymodelis aconcretethingthatmechanicallygeneratesitsownbehaviour:waterliterally sloshesinthemodel,andwhenitsloshesinaparticularwayinthemodel,theuser infersthatwaterwillsloshsimilarlyintherealSanFranciscoBay.Whileconcrete modelsarenottheonlytypeofmodelthatismeanttolicensedynamical inferencesabouttheirtargetsystems,theyaretheonlytypeofmodelthatdoes thisbypresentingactualbehaviour.Asaresultofthisbuilt-inbehaviour,usersof aconcretemodeldonotneedtoknowhowtoreasonabouthowthesystemshould beexpectedtoevolve – rather,aconcretemodeldemonstratesthatevolution.For example,aschematizedcellinabiologytextbook(anabstract/mentalmodel) doesnotdemonstratetoushowmitochondriabehaveincells,butalaboratoryrat (aconcretemodel)mightverywellbeusedtodemonstratethisbehaviour.

Whenconsideringconcretemodels,asometimesusefuldistinctionisthat betweenanalogicalmodels(Bailer-Jones2002, 2009; Bailer-JonesandBailerJones2002; Hesse1963, 1967, 1974)andscalemodels(Black1962; Sterrett 2006, 2021).Bothanalogicalmodelsandscalemodelsareconcrete,butan analogicalmodelisfound(e.g.,thesolarsystemasamodeloftheatom)and ascalemodelisconstructed(e.g.,theSanFranciscoBaymodel).Whileinferencesfrommodeltotargetareprobablythemoststraightforwardinthecaseof scalemodels,thisdoesnotnecessarilytranslateintoreliability.Itisveryeasyto seewhattheSanFranciscoBaymodelsaysaboutwhatwillhappeninthereal SanFranciscoBay.However,theinferenceisonlyasreliableastheassumption thatoneisacausalduplicateoftheother.Infact,thisisalmostcertainlynottrue inthiscase,because fluidshavescale-dependentfeatures.TheSanFrancisco Baymodelwasmostlyusedforrhetoricalpurposes(moreontheuseofmodels forrhetoricalpurposesin Section3).

1.2.3DataModels

Anexampleofadatamodelfromourintroductorylistisareconstructedrecordof theEarth’stemperatureinpastgeologicalperiodsthatisdevelopedusingproxy data.Adatamodelisessentiallyasummaryofinformation – a corrected, normalized,systematized,and idealized summary – thatscientistsbelieveis relevanttotheirreconstructionprojectandthattheyhavecollectedfromvarious datasources.Forexample,scientistsmaystartbysummarizingvariationsinthe ratioofdifferentisotopesofoxygenindeepicecoresandinthefossilizedshells oftinyanimals(Parker2018)andgraduallyincorporatethisdatamodelinto anothertodrawinferencesabouttheEarth’stemperatureinthepast.Examplesof otherfamiliardatamodelscomefromrandomizedcontrolledtrialsandobservationalstudiesinthehealthsciences:forexample,whenanewdrugisdeveloped, researcherswillroutinelycollectselectedpiecesofinformationfrompeoplewho aretakingandthosewhoarenottakingthedrugandsummarizeitintheformof adatamodel(e.g.,descriptivestatisticalmodelsofclinicaloutcomes).Suchdata modelsoftenbecomeusefulsourcesofclinicalinformationthatareperceivedto berelevanttoandcanbeincorporatedintootherresearchprojects,including computationalmodels(describedinthe nextsubsection).Forexample, arandomizedcontrolledtrialmay findthatpatientswhoreceiveanewasthma drughaveanannualrateofasthmaexacerbationof0.11(95%CI0.10,0.13), whilepatientswhoreceiveanexistingasthmadrughaveanannualrateof exacerbationof0.12(95%CI0.10,0.14).Thissummaryofclinicalinformation maythenbeincorporatedasa parameter inthesortofmodelthatisusedto explorethecost-effectivenessofanewmedication(e.g., FitzGeraldetal.2020). Importantly,datamodelsalsoplayacentralroleinevaluatingcomputational models.Thatis,theresultsofcomputationalmodelswilloftenbedirectly comparedtodatamodelsasameansofassessingwhethertheirresultsare consistentwithourexistingknowledgeabouttheworld.Althoughourfocusin thelatersectionsofthisElementisnotondatamodelsthemselves,theyareakey componentofthemodelswefocuson.Inthiscontext,theimportantthingtokeep inmindisthatdataanddatamodels ‘arerepresentationsthatareproductsof aprocessofinquiry’ (BokulichandParker2021,31).Liketheothermodelswe discuss,datamodelsinvolverepresentationalchoices,andourobjectiveisfor themtobe adequateforpurpose,nottrueorfalse.

1.2.4Mathematical(includingComputational)Models

Atahighlevel,thepurposeofmathematicalmodelsistobeableto fittogether mathematicalrelationshipsthatwethinkdescribetheworldandapplythemto atargetsystem.Thosemathematicalrelationshipscanbebitsoftheory,law,

mathematicalregularity,rulesofbehaviour,ortheproductofourownhuman reasoning.Wethenusethemathematicalmodeltoreasonaboutthattargetsystem andhelpusbetterunderstandit.Think ofaweathersystem,ahurricane,traffic patterns,predator–preyrelationsinanecosystem,orthespreadofdiseasein ahumanpopulation.Inaweathermodel,we fittogetherlawsofthermodynamics withlawsthatgovernthedynamical flowofparcelsofairintheatmosphere.In ahurricanemodel,wetreattheatmosphereasa fluidthatwedivideintoparcelsand usebasicprimitivelawsofmotionaswellasthermodynamiclawsofgasdynamics tocalculatehowthoseparcelsofairwillmovearound.Inatrafficmodel,wegive eachcar(withitsdriver)asetofrulesforwhenitwillspeedup,slowdown,orstop dependingonwhatitseesinitsenvironment.Inapredator–preymodel,we fit togetherourbestassumptionsabouttherateatwhichpredatorskillpreywiththe rateatwhichpredatorsdiewhentheyfailtocaptureprey.Attheendoftheday,the goalistointegratevarioussalientbitsoftheoryandothermathematicalregularities thatwehavesometrustinsothattheycanbeappliedtodrawoutinferencesabout the targetsystem (thehurricaneorthetrafficjam)byreasoningwiththemodel (MorganandMorrison1999,chap.1; Winsberg2010).

Computationalmodelscanbeunderstoodasasubsetofmathematicalmodels. Amathematicalmodelbecomescomputationalwhenthebitsofmathinthe modelbecometooanalyticallyintractabletodrawtheneededinferencesusing pencilandpaper.Oftenthisisbecausethemodelinvolvesdifferentialequations thatcan’tbesolvedanalytically(Winsberg2010).Butitcanalsobebecausethe mathematicalmodelismoreaboutrulesofbehaviourthanitisaboutsolvableor unsolvableequations.

Earlierwepointedoutthatabstract/mentalmodelsarequitedifferentfrom concretemodelsinthatthelattermechanicallygeneratetheirownbehaviour whiletheformerrequiremodeluserstoeffectivelymentallysimulatethebehaviour ofthetargetsystem.Asaresult,whatbehaviourabstract/mentalmodelswillpredict dependsquiteabitonwhatthemodeluserbringstothetask.Mathematicalmodels, interestingly,straddlethisdivide.Ifyouhaveabasicpencilandpapermodelwith whichyoucanmakesimplecalculations,thenthemodeljustdoeswhatitdoes,not unlikeaconcretemodel.However,ifthemathematicalmodelneedstobeturned intoacomputationalmodel,thenhowthatgetsimplementedbyitsbuilder/userwill oftenhaveasignificanteffectonwhatbehaviouritexhibits.

1.3MathematicalandComputationalModels:ACloserLook

Inthissubsection,wedelveingreaterdetailintomathematicalandcomputationalmodels; Sections2, 3,and 4 willfocusonphilosophicalissuesconnected specificallywiththesemodels.Ourmaingoalinthissubsectionistoestablish

thatmathematicalmodelscanvaryalongatleast fiveoverlappingcontinua –idealization, articulation, credentials, sensitivity,and skill –andtoexplainhow wewillusethesetermsintheremainderofthisElement.

1.3.1Idealization

Ithasbecomepopularinrecentphilosophyofsciencetocallcertainkindsof models ‘idealized’ models,andtodivideso-calledidealizationinto ‘Aristotelian idealization’ (McMullin1985)and ‘Galileanidealization’ (Cartwright1989).On thisaccount,Aristotelianidealizationconsistsof ‘strippingaway’,inourimagination,allpropertiesfromaconcreteobjectthatwebelievearenotrelevanttothe problemathand.Thisallowsustofocusonalimitedsetofpropertiesinisolation. Anexampleisaclassicalmechanicsmodeloftheplanetarysystem,which describestheplanetsasobjectsonlyhavingshapeandmassanddisregardsall otherproperties.Galileanidealizations,ontheotherhand,areonesthatinvolve deliberate distortions.Physicistsbuildmodelsconsistingofpointmassesmoving onfrictionlessplanes,economistsassumethatagentsareomniscient,biologists studyisolatedpopulations,andsoon.ItwascharacteristicofGalileo’sapproach tosciencetousesimplificationsofthissortwheneverasituationwastoo complicatedtotackle(FriggandHartmann2012).Inmathematicalmodels, AristotelianandGalileanidealizationusuallyworkinharmony.Indeed,thetwo generallygohandinhandforgoodreason:so-calledGalileanidealizationusually onlyworksinsofarassomedegreeof ‘Aristotelian’ reasoningisinplay.Ifwedo toomuchGalileanidealizationwithoutensuringthatthisidealizationdoesn’t affectwhatis ‘relevant’ tous,wewillgetintotrouble.Makingthetwokindsof idealizationworkinharmonyispartofthewayweensurethatourmodelsare adequateforpurpose.Thetakeawaypointisthatmathematicalmodels(including computationalmodels)canvaryintermsofhowidealizedtheyare,bothinterms ofthedegreetowhichtheysimplifyreality(i.e.,excludeelementsofthetarget systemfromtherepresentation)anddistortit(i.e.,deliberatelychangeelements ofthetargetsystemintherepresentation).

1.3.2Articulation

Earlier,wedrewattentiontothefactthat mathematicalmodelsseemtocomeintwo varieties.Sometimes,amathematicalmodelinvitesustousesimplepaperand pencilmethodstodrawoutinferencesabouttheworld.Othertimes,amathematical modelneedstobeaugmentedwithadditionalreasoning,includingreasoningabout whichcomputationalmethodscanandwillbeusedtoimplementit – and,aswe said,howacomputationalmodelgets implementedwilloftenhaveasignificant effectonwhatbehaviouritexhibits.Considerthecaseofacomputationalmodel

designedtosimulate fluid flowsthatcontainsignificantshockdiscontinuities.The existenceofshocksmakesitdifficulttoturnthedifferentialequationsof fluid dynamicsintoastep-by-stepalgorithmthatacomputercancalculatewithouterrors compoundingandblowingup.Ahostofdifferentstrategies,includingtheso-called piecewiseparabolicmethoddiscussedin Winsberg(2010,46),isanextremecase ofamathematicalmodelneedingsubstantialaugmentationinordertobeimplementedsuccessfully,anddifferentimplementationscouldleadtosubstantially differentresults.Ausefulpieceofvocabularytohelpunderstandthedegreeto whichamathematicalmodelneedstobesupplementedwithadditionalreasoningin ordertosuccessfullycalculatewithitis articulation.Wecansaythatthesimplest paperandpencilmodelwillnotrequireanyarticulationatall,whileanycomputationalmodelwillrequireatleastsomedegreeofarticulation;themorecomplexthe computationalmodel,themorearticulationitwillrequire.Amodelcomprising differentialequationsof fluiddynamicsthatwehopewillenableustocalculatethe behaviourofshockswillrequireenormousarticulation.Onlyamodelthatrequires noarticulationwilljust ‘dowhatitdoes’,thatis,generateitsownbehaviourlike aconcretemodel(see Section2.4).Notethatitmaybetemptingtosaythatoncewe have finisheddevelopingacomputationalmodel,themodeljust ‘doeswhatit does’.However,thisisonlyreallytrueifwezeroinonaspecificversionofthe model,writtenwithaspecificsetofinstructions,runonaspecificpieceof hardware,andcompiledbyaspecificcompiler.Otherwise,the ‘same’ computationalmodel(ifitiscomplexenough)canveryeasilyexhibitsubstantiallydifferent behaviour.Itisthereforeveryusefultounderstandmathematicalandcomputational modelswithreferencetothedegreeofarticulationtheyrequire.

1.3.3Sensitivity

Inmanycontexts,amodel’s sensitivity referstohowsensitiveitsoutputisto choicesofparametervalues.Moregenerally,itcouldrefertohowsensitivethe model’soutputistomethodologicalchoicesofanykind.Itisimportantto distinguishamodel’ssensitivitytochoicesofparametervaluesandthesensitivitythatthesystemitmodelsexhibitstotheinitialvalueofitsvariables.Here weareconcernedwiththeformer.

Whatisthedifferencebetweenavariableandaparameter?Aparameter valueisthevalueofsomemeasurablequantityassociatedwiththesystemthat stays fixedthroughoutthelifeofthesystemoverthetimescaleofthemodel, whileavariable,obviously,varies.Avariableforamodelisthusbothaninput foramodel(thevaluethevariabletakesataninitialtime)andanoutput(the valuethevariabletakesatallsubsequenttimes – including,ofcourse,atthe finaltimeofamodelrun).Aparameterissimplyaninput.So,forexample,inan

epidemiologicalmodel,itmightbethatthereproductiverateofthevirusis aparameter,andthevalueforthenumberofpeopleinfectedatanyonetimeis avariable.

Whenbuildingmathematicalmodels,therecanbevaryinglevelsofuncertaintyaboutwhattorepresentinthemodelandhowtorepresentit.Insome cases,thereisawealthofwell-establishedbackgroundknowledgeaboutthe targetsystem,whichfunctionstoinformandeven constrain representational decisions.Forexample,whenmodellersbuildcomputationalmodelsofthe motionsoftheplanetsinthesolarsystem,modellers’ representationaldecisions areconstrainedbythewell-establishedlawsofcelestialmechanics.However,in othercases,backgroundknowledgeaboutatargetsystemislacking:thereisfar moreuncertaintyaroundwhatshouldberepresentedinthemodelandhow.In thesecases,wesaythatrepresentationaldecisionsare unconstrained.When amodelisbuiltundertheseconditions,itisimportantformodellerstoexplore whetherandhowmodelresultschangewhentheymakedifferentrepresentationaldecisions.Inotherwords,itisimportanttoexplorehow sensitive model resultsaretochangesinrepresentationaldecisions.IfthevalueofXthat amodelcalculatesishighlysensitivetorepresentationaldecisions,andthose decisionsarenothighlyconstrained,wehavereasonsnottotrustthemodelto giveusprecisepredictionsofthevalueofX.

1.3.4Credentials

Roughlyspeaking,amodel’scredentialscorrespondtohowmuchtrustwe shouldputinit:thedegreetowhichweshouldexpectthemodelnottoletus down,butrathertoprovetobeasuccessfulwayofunderstandinghowtheworld works.Inthecaseofmathematicalmodels,modelcredentialsareintrinsically linkedtothe ancestries ofwhateverbitsofmathhavegoneintomakingthem. Afterall,bitsofmathcancomefromalmostanysourceweusetogain knowledgeabouttheworld:theycancomefromtheory,frompatternswesee indatathatwethinkarerobust,orjustbasicassumptionswethinkareplausible (forwhateverreason).Ifthebitsofmaththatgointoamodelcomefromtheory, thiswillhelptogivethemodelcredentials(aswedescribedin Section1.1,we reservetheterm ‘theory’ fora well-credentialled wayofunderstandingthe world,onethatenjoysnotonlywiderecognitionbutahistoryofsuccess).Ifthe bitsofmaththatgointomakingamathematicalmodelcome,notfromtheory butfrom modelsofdata,thenthosebitsofmathwillonlybeasgoodandas widelyapplicableasthosemodelsofdata – themodel’scredentialsarelinkedto thedatamodels.Andifthosebitsofmathcomenotfromtheory,notfromdata models,butfromhumanintuitionsofwhatisplausible,thenthosebitsofmath

willonlybeasreliableashumanintuitionsare.Amodelwhosecredentialsare intrinsicallylinkedtohumanintuitionsisoneweshouldputlesstrustin.

Togiveanexample,imaginewearebuildingaclimatemodelandweneed abitofmaththatcalculateshowmuchinfraredradiationtheEarthradiates backasitabsorbsultravioletradiationfromtheSun.To fi ndone,wecanreach fortheStefan – Boltzmannlaw,whichisadirectapplicationofPlanck’slaw, whichisultimatelygroundedinthewell-establishedtheoryofquantum mechanics.Puttingamathematicalrelationshiplikethatintoourclimate modelisunlikelytoletusdown.Ontheotherhand,imagineweneedabit ofmaththatcalculateshowmanycloudsandofwhatkindwillforminvarious parcelsoftheatmosphere.Unfortunately,itisunlikelythatwewillbeableuse basicphysicstocalculatethis:ingeneral,climatemodelsaretoocoarsegrainedto ‘resolve ’ cloudformation(Winsberg2010 , 2018 ).Instead,wewill needtocomeupwitha subgridmodel ofcloudformation.Thegoalof asubgridmodelistodictateafunctionthatwilltellushowmuchcloud structurethereisineachgridcellofthesimulationasafunctionofthe temperature,humidity,pressure,ando thervariablesinthegridcell.Because subgridmodelsoftenrequireanumberofparametervaluestospecifythem, theyareoftencalled parameterizations.Thesesubgridmodelshavecomplex ancestries:theyarederivedfromlaboratoryexperiment, fieldobservation, and,morerecently,fromtheoutputof machinelearningalgorithms.Noneof thesesourceswillhavethesamecredentialsasourpieceofmaththatcalculatesinfraredradiation.Furthermore,itisnotuncommoninclimatemodels fortheparameterizationofcloudformationtobedeliberatelywrong – soasto offsetothererrorsthatclimatemodelsareknowntohave( Mauritsenetal. 2012).Thishighlightsanimportantfactaboutrepresentationaldecisions:the bestrepresentationaldecisionistheonethatismostadequateforpurpose,not necessarilytheonethatistruetotheworld.The ‘best ’ parameterizationof cloudformationinaclimatemodelmightnotbetheonethatmostaccurately depictscloudformation,buttheonethat,inconjunctionwithalltheother representationaldecisions,makesthemodelmostadequateforpurpose(that is,perhaps,theonethattellsusthetruestthingsaboutwhattheclimatewillbe likeattheendofthecentury,ifthatisourmodel’spurpose).

Totheextentthatmodelconstructionsdependonhumanjudgementand ability – ratherthan,forexample,beingdeterminedbytheory – ourappraisal ofthetrustworthinessofamodelmightdepend,atleastinpart,onthepeopleor groupsofpeoplewhobuiltthemodel.Differentresearchersandgroupsof researchershavepasttrackrecordsofsuccess,institutionalcredentials,andso on,andthereisnoreasonthattheseelementsshouldnotaffectthedegreeof trustwecanrationallyputintheirwork.

1.3.5Skill

Mathematicalmodelscanhelpustoreasonabouttheworldinmyriadwaysand canbeputtoalmostinfinitelymanypurposes(aswesaid,nothingtechnically stopsusfromusingamodelasanartinstallation).However,modelsdovaryin theirdegreeofadequacyfordifferentpurposes.Onewayofunderstanding modeladequacyforpurposeisintermsofmodel skill (Winsberg2018,chap. 10).Skillreferstoamodel’sadequacyforspecifictypesofepistemicpurposes.

Threeexamplesofepistemicpurposesforwhichmathematicalmodelsmaybe moreorless skilled arethefollowing:

(1) Prediction: mathematicalmodelscanhelpustoknowwhatatargetsystem willdointherealworldatsomeparticularpointintime.

(2) Projection: mathematicalmodelscanhelpustoestimatewhatatarget systemwouldlikelydounderdifferentpossiblecounterfactualscenarios, especiallyundervariouspossiblehumaninterventions.

(3) Causalinference: mathematicalmodelscanhelpustolearn whatcauses what inatargetsystem.Ifamodeloftheclimatewithoutincreasedcarbon concentrationdoesnotexhibitthewarmingexhibitedbyboththerealworld andmodelswithincreasedcarbonconcentration,thenwemightplausibly inferthatthecarboncausedthewarming(especiallyifthatwarming exhibitsthesame ‘fingerprints’ inbothcases).

Aswewillseeinthe nextsection,sometimesmodelskillcanbemeasuredusing specifictypesofempiricaltests.However,atothertimesnosuchempiricaltests areavailable,inwhichcasemodelusersmustjudgeamodel’sskillusingother means,oftentakingintoconsiderationitslevelsofidealization,articulation,and credentials,amongotherthings.Inanycase,modelskillshouldbeunderstoodon acontinuum:thatis,whenassessingamodelforthepurposeofprediction, projection,orcausalinference,wespeakofitbeing moreorless skilled.

1.4Conclusion

Inthisintroductorysection,wecanvassedavarietyofdifferentrepresentational entitiesinsciencethatarearegularlyreferredtoas ‘models’.Wenotedthatthis wasanextremelyheterogeneouscollectionofentities,butthattheycouldbe looselygroupedintofourcategories:abstract/mentalmodels,concretemodels, datamodels,andmathematical/computationalmodels.Wealsonotedthatone thingtheseentitieshaveincommonisthatwhiletheyareallrepresentational (thatis,theyalldepicttheworldasbeingsomewayoranother),fewofthemare truthapt – thesortsofthingswesayare ‘true’.Rather,theyareadequate(ornot) forsomepurposeoranother – thoughoftenthepurposeforwhichwehopethey

areadequateincludesthepurposeofinferringtrueclaimsabouttheworld.The modelsthemselvesarenottruthapt,butoftentheinferenceswedrawfromthem are,andadequacyforpurposeoftenmeans ‘thismodelisadequateforinferring claimsabouttheworldthatarelikely(enough)tobetruetoahigh(enough) degreeofaccuracyinabroad(enough)domainofapplication’.(There’llbe muchmoreonthisinthe nextsection.)

Wenextdecidedtozeroinonmathematicalandcomputationalmodels.We sawthatmodelsliketheseareespeciallyusefulforthetasksofprediction, projection,andcausalinference,andthatthis,inturn,makesthemespecially usefulandimportantinguidingdecision-making.Whenthisisthecase,it’s especiallyhelpfultotalkaboutthedegreeof skill thatmodelsofthiskindhave forcarryingoutthesetasks.Skill,wesaid,isadequacyforaspecifickindof quantitativepurpose,andevaluatingtheskillofamodelforvariouspurposesis complexandmotley – butitofteninvolveslookingatthecredentialsofthe model,andthedegreetowhichitisidealized,articulated,andsensitivetothe representationalchoicesthatwemadeincreatingit.

2AdequacyforPurpose

2.1Introduction

In Section1,weemphasizedthatourobjectiveisnotusuallythatamodelbetrue, butratheradequateforpurpose.Thisnaturallyleadstothequestion: ‘whatdoesit mean foramodeltobeadequateforpurpose?’.Thissimplequestionhasafairly straightforwardanswer:themodeluserssimplyneedtotrustthattheycanusethe modelforwhatevertaskstheyintendtouseitfor.However,thissimplequestion invitesfartrickierones.Forexample, ‘Whatareallthepurposestowhichmodels canbeput?’.Infact,modelscanhavemyriadpurposes:theycanbeusedtomake predictionsorprojectionsofvariouskinds,todrawcausalinferences,toexplain behaviour,toconveythingspedagogically,orforsomethingelseentirely. Furthermore,whenwespecifyamodel’spurpose,weusuallydosorelativeto aparticular standardofaccuracy.Inotherwords,wemaycountamodelas adequateforpurposeifitgetsthingsrightacertainamountofthetime,butno less:ourmodel’spurpose,then,iscementedtoourstandardofaccuracy.Wealso tendtospecifyamodel’spurposerelativetoaparticular domain.Wemaytrust amodeltopredicttheweatherinonegeographicalregion,butnotinanother,for example.Becauseofthis,amodel’spurposemayendupbeingexpressedin arathercomplicatedsortofcompoundstatement:wemayintendamodeltoassist reasoningin x way,to y degreeofaccuracy,andacross z domainoftargets.Inlight ofthiscomplexity,articulatingallthepurposestowhichmodelscanbeputis aloftyproject(andwewillnotattemptithere).Thebestwecandoisprovide

illustrativeexamples,whichcanhelpusgainagoodunderstandingofagiven model’spurposeincontext.

Aneventrickierepistemologicalquestionis: ‘howdowe decide when amodelisadequateforaspecifiedpurpose?’.Thisquestiondefiesageneral answer – andweshouldbeveryclearthatthequestionofwhat ‘adequacyfor purpose’ means isadifferentquestionfromhowweassessit.Infact,assessing amodel’sadequacyforpurposerequiresagoodunderstandingofthemodel’s purposeincontext,aswellasintimateknowledgeofseveralmodelattributes, includingitslevelsofidealization,articulation,credentials,andsensitivity, amongotherthings.Forexample,ifusingamodelrequiresthatitbeseeded withinitialconditionsthatreflectthepresent(orpast)stateoftheworld,then ourassessmentmightalsodependontheconfidencewehaveinthedatamodels thatwetreatasinitialconditions.

Inthissection,weexplorethetopicofmodeladequacyforpurposebytaking acloselookatthreedifferentmodelsthatareusedintheEarthandatmospheric sciences:a zero-dimensionalenergybalancemodel,a weatherforecasting model,anda globalcirculationmodeloftheatmosphere.Aswewillsee,each ofthesemodelsisusedforadifferentpurposeinadifferentcontext,andeach hasitsownspecialcombinationofattributes.The firstofthesemodels,in particular,isusedforwhatwecallan idealizedpurpose,thatis,apurposein thecontextofAristotelianidealization.Thesecondandthirdmodels,onthe otherhand,areusedfor non-idealizedpurposes,whicharethesametypesof epistemicpurposesthatweassociatewithmodel skill (Section1.3.5).The measurementofmodelskill(or ‘adequacyforanon-idealizedpurpose’)raises specialepistemologicalissuesindifferentcontexts:insomecases,modelskill canbemeasuredoperationally;inothers,itcannot.Inlightofthesecomplexities,ourdiscussionofassessingadequacyforpurposeproceedsdifferentlyfor eachofthemodelsweexploreinthissection.

2.2AZero-DimensionalEnergyBalanceModel

Oneverybasicepistemicpurposetowhichmodelscanbeputis explanation: modelscanhelpustounderstandwhyatargetsystembehavesinthewayit does.Consideraveryinterestingphenomenonwemightliketoexplain:why doesEarthhaveanequilibriumtemperature,ratherthansimplyheatingup indefinitelyandburningupundertheSun?Tohelpexplainthis,wecanuse asimplemathematicalmodelcalleda zero-dimensionalenergybalancemodel (ZDEBM)(Winsberg2018).Thissimplemodelisdescribedas zerodimensional becauseitdoesnotallowforanyvariationintime,norany variationinspace.ItsimplytreatstheEarthasthesurfaceofasphere,asit

wouldlooktoyouifyouwerelookingatitfromthesurfaceoftheSun,whichis reallyjustadisc.Theterm energybalance inthemodel’snamehintsatthe usefulexplanationitprovides,whichisthatEarthreachesanequilibrium temperaturethankstoabalancebetweenitsincomingandoutgoingenergy.

Asitallowsnovariationintimeandnovariationinspace,wecanalreadytell thataZDEBMisahighly idealized model.Themodelstripsawayproperties thatarenotrelevanttotheproblemathand,whichistounderstandwhyplanets achieveequilibriumtemperatures.Italsoinvolvesdeliberatedistortions,aswe willsee.However,themodelissimpleenoughthatwecanreasonwithitusing pencilandpaper:itdoesnotrequirearticulation.

Thebitsoftheoryandmathematicalrelationshipsthat fittogetherinthe modelcomefromsolarphysics,simpleoptics,andquantummechanics,which areallwell-credentialledsources.Hereishowtheyworktogetherinthemodel:

• Solarphysicstellsushowmuchincomingradiationthereis.

• Simpleopticstellsusthatsomeofthatradiationgetsreflectedintospace.We calltherateatwhichtheEarthreflectssolarradiationits ‘albedo’ .

• TheStefan–Boltzmannlawofblackbodyradiationtellsushowmuchradiation getsre-radiatedbackintospace.Thehotterthediscgets,themoreradiation getssentback.

Ifweassumethatallofthesemustbalanceout,wecancalculateatarget temperatureinthefollowingway.

Theonlysourcesofincomingandoutgoingenergyareradiation,whichwe canmeasureinwattspersquaremetre(Wm 2).Sowehaveincomingradiative energy,Ein,andoutgoingradiativeenergy,Eout.Andsincewewantanequilibriummodel,weset

Ein ¼ Eout : ð1Þ

WecalltheenergypersquaremetrethattheSundeliverstotheEarththe ‘Incidentsolarradiation’,S0.

SincetheEarthpresentsadisc-shapedfacetotheSun,ithasarea π R2 ,soit receives π R2 S0 inincomingradiation.

Weassumethatsomefractionofthat(whichwecallthealbedo)isreflected backintospaceandthattheremainder(1-α)(the ‘co-albedo’)isabsorbed.We nowhaveaformulaforEin:

Ein ¼ 1 α ðÞπ R2 S0 ð2Þ

Tomodeloutgoingenergy,themodeltreatstheEarthasasimple,spherical blackbodythatobeystheStefan–Boltzmannlaw,whichsaysthatablackbody

willradiateawayheatinproportiontothefourthpowerofthetemperature(T,in degreesKelvin),withtheconstantofproportionality, σ ,calledtheStefan–Boltzmannconstant.Thisgivesusanequationfor Eout :

¼ 4π R2 σ T

(4π R2 beingthesurfaceareaofasphere)

Combining equations1, 2,and 3,andsolvingforTweget:

Since S0 ¼ 1; 368Wm 2 and σ ¼ 5 67 10 8 Wm 2 K 4

wecalculatethatT ¼ 254:8Kor 18:38C:

WecancallthistheEarth’s effective temperature.Notethatthisisnotequalto theEarth’s actual temperature,whichismorelike15°C:ifourgoalwasto findthe Earth’sactualtemperature,ratherthanitseffectivetemperature,wewouldneedto alterthemodeltomakeitaccountfortheEarth’semissivity.2 However,thegoal ofaZDEBMisnotto findEarth’sactualtemperature.Rather,thepurposeofthe modelistoexplain whyplanetshaveanequilibriumtemperature andidentify thedominantcausalprocess.Themodelgivesusaverygoodexplanationofthis phenomenon:theEarth’singoingandoutgoingenergybalanceout.

Theastutereadermightbetemptedtointerjectthefollowing: ‘Igetthat aZDEBMisbeingusedforexplanationratherthanprediction,butIstilldon’t understandhowamodelthatgetsEarth’sequilibriumtemperaturesowrong couldbeadequateforanypurposethathastodowiththeEarth’stemperature. ’ TheanswerherehastodowithAristotelianidealization.RecallthatAristotelian idealizationiswhenwestripaway,inourimagination,factorsthatwedeem unimportanttothesystemofinterest.Insuchcases,itishelpful,following MartinJones(2005)andPeterGodfrey-Smith(2009),tothinkofmodelsthat engageinAristotelianidealizationastellingusliterallytruethingsabout abstractsystems.So,onthisconception,theZDEBMisaperfectlyaccurate modelofaperfectlysphericalblackbodyimmersedforanarbitrarilylongtime inauniform fieldofhighfrequencyradiation.Whyshouldwecareaboutthatif wearethinkingabouttheEarth,whichis,afterall,notaperfectlysimpleblack body,andsoon?Thereasonisthatwethinkthatinunderstandinghowsuch

2 Thesimplestwaywecoulddothiswouldbetoaddasimple ‘emissivitycoefficient’ tothemodel. Theemissivitycoefficient(callit ε)isdefinedastheproportionoftheenergyradiatedoutbyabody relativetowhatablackbodywouldradiate.Therearevariouswaysofmeasuringtheemissivityof theEarth,andtheygenerallysettle,forthepresenttime,ataround ¼ 0 62.Therearealsomore complexwaysforclimatemodelstoaccountforEarth’semissivity,buttheyresemblethemethods discussedin Section4 muchmorethantheydothesimplemodeldiscussedinthissection.

asimple,idealized,imaginarysystembehaves,wegetinsightbothintowhythe Earthhasanequilibriumtemperatureandregardingoneofthemostfundamentalcausalprocessesinvolvedindeterminingwhatitis.Inmanycases,radical idealizationofthekindweseeinaZDEBMisared flagthatamodelisunlikely tobeadequateforpurpose.However,inothercases,weunderstandthepurpose ofthemodelintermsofAristotelianidealization,andintermsofgettingatonly one ofmanypossiblecausalprocessesthatarebehindaphenomenonwewantto understand.Inthosecases,itiseasytoseewhyradicalidealizationisnotan impedimenttoadequacyforpurpose.

2.3WeatherForecastingModel

Thepurposeofweatherforecastingmodelsistomakespatiallyandtemporally fine-grained predictions aboutstatesoftheatmosphereoverashorttimehorizon –inotherwords,totelluswhatweatherconditionswill actuallyoccur at aparticulartimeandplaceinthenearfuture.ComparedtotheZDEBMdescribed in Section2.2,weatherforecastingmodelsarefarlessidealized.Infact,these modelsarebasedonacomparativelyhighdegreeof fidelitytoourunderstanding ofcausalrelationshipsinweathersystems.

Weathermodelsincorporatebothinitialconditionsandtheso-calledprimitiveequations.Theprimitiveequationsareasetofnon-linearpartialdifferential equationsgroundedinthewell-credentialledtheoriesof fluidmechanicsand thermodynamics.Initialconditionsareestablishedthroughadata-drivenprocess:directmeasurementsofalargenumberofobservablevariablesthat describetheatmosphereanditssurroundingsinaspecifiedregion,suchas temperature,precipitation,humidity,atmosphericpressure,wind,andcloud cover.Alongwithdirectmeasurementsofthesevariablesatweatherstations, dataoninitialconditionscomefromsatellitedata,aircraftobservations,weatherballoons,andstreamgauges.Thismeasurementprocessresultsinawealth ofdata,whichareoftensubjectedtovarioussmoothing,interpolation,anderror correctionmethodsthatturnthemintostandardizeddatasets(i.e.,modelsof data).Thesestandardizeddatasetsaretreatedasinitialconditions.3

Theprimitiveequationsareonlysolvableanalytically(i.e.,withpaperand pencil)inverysimpleandunrealisticscenarios,whichmeanstheyhavetobe turnedintoequationsthatcanbecalculatedtime-stepbytime-steponacomputerif weactuallywanttopredicttheweather.Thismeansweatherforecastingmodels requirearticulation.Articulationoftheequationsofthismodelconsistsintransformingthemintoaformthatisdiscreteinbothspaceandtime.(Inaweathermodel, thespatialgridsizeisroughly10kilometresandthetime-stepisafewminutes.)

3 Formoredetail,seetheNationalWeatherServicewebsite, www.weather.gov/about/models.

Thediscretizedversionoftheequationsissupplementedwithparameterizationsthattrytoestimatewhatishappeninginsidetheserelativelylargegrid cellsandisthereforelosttotheprimitiveequations.Oncethecomputermodel completesthesecalculationsforonetime-step,themodelcancreatesomething thatlooksjustliketheinitialdataset.Thisnew ‘dataset ’ isfedbackintothe model,whichthenrunsforanothertime-step.Themodelcanbeusedto visualizethesedatatoseewhattheatmospherewilllooklikeovertime.We canalsocombine(say,byaveraging)theforecastsofensemblesofmodelsthat relyondifferentarticulationsorondifferentdatasetsbywayofinitialconditions. Oftentheensembleaveragesperformbetterthananysinglemodel.

Anepistemologicallysignificantthingaboutweathermodelsisthatwecan measuretheirforecastingskill(i.e.,theiradequacyfor prediction)fairlyobjectivelywithvariousoperationalizedmetrics.Ifweuseaweathermodeltomake alargenumberofforecastsandthencomparethosetowhatactuallyhappens, wecandefinemeasuresofforecastingskilllikemeanabsoluteerror(MAE), bias,andBriarscore.Thesemeasurestellus,respectively,thingslikehowfar thepredictionsarefromwhatwemeasured,whethertheyaresystematically wronginonedirectionoranother,andwhethertheprobabilitiestheygenerate matchtheobservedfrequenciesintheworld.4 Thisenablesustoseehowmuch progressisbeingmadeinimprovingaweathermodel’sforecastingskillover time.TheBriarscoreisespeciallyimportantbecauseitlendsanaturalunderstandingtotheprobabilitiesthatweatherforecastsgiveus,sincetheyare evaluatedwithrespecttoobservedfrequencies.

Insummary,weathermodelsweartheiradequacyforpurposeontheir sleeves:becausetheyareusedtopredictphenomenathatwesooncometo observeingreatdetail,wecanmeasuretheirskillinarelativelystraightforward manner.Onthe flipside,wecanseeveryeasilywhatweathermodelsare not skilledat:aseveryoneknows,itisimpossibletopredictwhetheritwillrainon anyparticulardaysixmonthsfromnow.Aswewillseein Section2.4,model skillcannotalwaysbemeasuredsostraightforwardlyasitcaninthecontextof weathermodels.Thisraisesspecialepistemologicalissues,notablyinthearea ofclimatescience.

2.4ClimateModels

Thedynamicsoftheatmospherearechaotic.Thismeansthatsmallerrorsin initialconditionsgrowveryfastwhenwetrytopredictthefuturestateofthe atmosphere,whichexplainswhypredictingtheweathermorethanabout10days

4 Formoredetail,seetheMeteorologicalDevelopmentLaboratorywebsite, https://vlab.noaa.gov/ web/mdl/ndfd-verification-score-definitions.

intothefutureisnearlyimpossibleforpracticalpurposes.Incontrastto ‘weather ’ , theveryconceptof climate istiedtoalongtimehorizon:whenwespeakof aregion’sclimate,wearereferringtobig-picturetrendsintheaveragevaluesof weathervariablesoverperiodsofatleast30years.Atahighlevel,then,the purposeofclimatemodelsistoproducecoarse-grainedsummariesofweather variables,oftenintheformofglobalorcontinentalaveragesordegreesof variation,andtousethisknowledgetohelpmakeprojectionsoffutureclimate conditions.Todothis,climatemodelsgenerallydonottakeintoaccountpresent weatherconditions.(Afterall,thesecontributeonlytotheclimatesystem’s internalvariability,whichisnotthetargetofinterestinclimatemodelling. Worsestill,theinformationcontainedinaweatherdatasetismostlylostafter about10daysofforecasting.)Whatclimatemodels do takeintoaccountarethe possibleeffectsofvarious externalforcings:thingslikeozonedepletion,CO2 emissions,othergreenhousegases,deforestation,andsoon.Theseareforcesthat areexternaltotheclimatesystem,butwhichcouldpushitbeyonditsnormal rangeofvariation – andthereforeaffectprojectionsoffutureclimateconditions. Ofcourse,thereismuchuncertaintyaroundtheseforcingsthemselves:future CO2 emissions,forexample,dependonnumerousunpredictablefactors,including(butnotlimitedto)futureenergypoliciesandpractices.Asaresult,climate modelsoftenconsiderarangeofplausiblefuturescenariosforexternalforcings, producingprojectionsthatcorrespondtothesecounterfactualscenarios.

Climatemodelsofthemostadvancedkindincludenotonlyrepresentations oftheEarth’satmosphere,butofitshydrosphere(includingriversandseas), cryosphere(icecapsandsheets),landsurfaces,andbiosphere,aswellasthe manycomplexinteractionsbetweenthesesystems.Ourpurposesforsuch modelsarealmostascomplexasthemodelsthemselves:weusethemto estimateclimatesensitivity;toattributehumanactivitiesasthecauseof observedwarming;toprojectregionalchangestotheclimateundervarious forcingscenarios;toprojectsea-levelrise;to findpossible ‘tippingpoints’ inthe climate(acriticalthreshold,thecrossingofwhichleadstodramaticand irreversiblechanges),andmore.Whilethesearesomeofthemany skills we hopeourclimatemodelswillhave,wearenotquitedonespellingoutthe purposesofclimatemodels.Inpractice,wehavetospecifymodelpurposes relativetothedegreeofaccuracyweexpect,thedegreeofconfidencewewant tohaveinananswerbeforeweuseit,andsoon.Inclimatemodellinggenerally, wefacecertainobstaclesthatwemustmitigateby lowering ourstandardsof adequacy:thechaoticnatureoftheatmosphereandthelongtimescalesthatare ofinteresttous,forexample,meanwemustlimitwhatweexpectfromour models.Atbest,wehopethatclimatemodelswillgiveusaveragesontimescalesoftwotothreedecades.Tomitigateothersourcesoferror,wetemperour