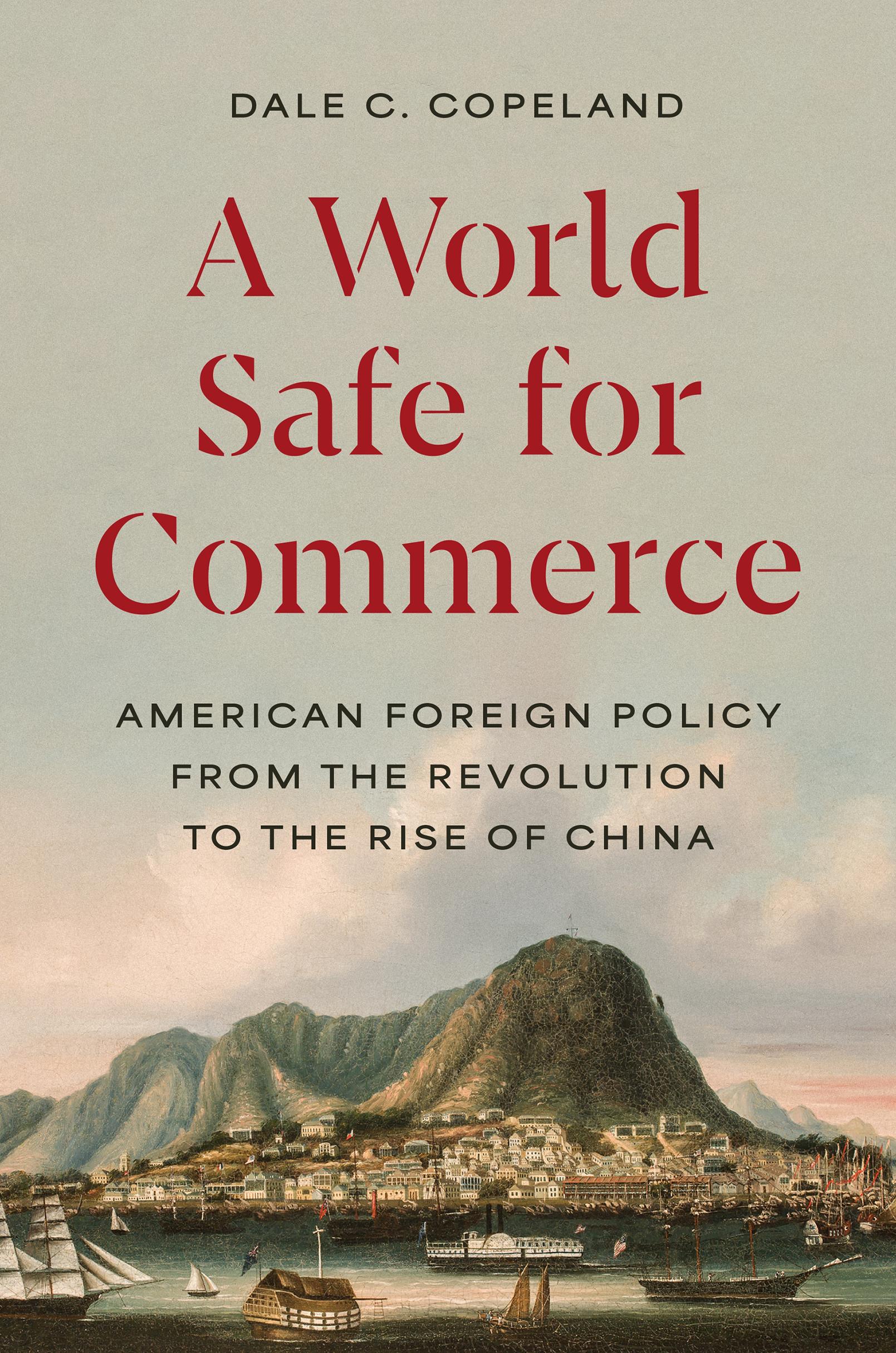

A World Safe for Commerce

AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY FROM THE REVOLUTION TO THE RISE OF CHINA

DALE C. COPELAND

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright © 2024 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Copeland, Dale C., author.

Title: A world safe for commerce : American foreign policy from the revolution to the rise of China / Dale C. Copeland.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2024] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023018406 (print) | LCCN 2023018407 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691172552 (hardback) | ISBN 9780691228488 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United States—Economic policy. | United States— Foreign economic relations. | United States—Foreign relations—China. | China—Foreign relations—United States. | BISAC: POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Economy | HISTORY / Asia / China

Classification: LCC HC103 .C76 2024 (print) | LCC HC103 (ebook) | DDC 330.973— dc23/eng/20230606

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023018406

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023018407

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Bridget Flannery-McCoy, Alena Chekanov

Jacket: Katie Osborne

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Kate Hensley (US); Kathryn Stevens (UK)

Copyeditor: Alison S. Britton

Jacket Credit: Hong Kong and Victoria Peak circa 1855 / Wikimedia Commons

CONTENTS

Preface vii

Acknowledgments xi

AbbreviationsforPrimaryDocumentsandSourceMaterial xv

Introduction 1

1 Foundations of Dynamic Realist Theory 12

2 Character Type, Feedback Loops, and Systemic Pressures 33

3 The Origins of the War for Colonial Independence 63

4 The United States and the World, 1790–1848 94

5 American Foreign Policy from 1850 to the Spanish-American War of 1898 142

6 The U.S. Entry into the First World War 189

7 The Second World War and the Origins of the Cold War 232

8 The Crises and Conflicts of the Early Cold War, 1946–56 286

9 Trade Expectations and the Struggles to End the Cold War, 1957–91 319

10 Economic Interdependence and the Future of U.S.-China Relations 354

Notes 395 References 447 Index 469

PREFACE

THE TITLE of this book, A World Safe for Commerce, has within it both light and dark undertones, swirling in tension like the two halves of the “yin-yang” symbol in Chinese Daoism. On the one hand, by playing off of Woodrow Wilson’s inspiring statement to Congress on April 2, 1917, that the United States had to enter the European war to “make the world safe for democracy,” I wish to evoke the idea that commerce has been and can still be a force for peace, and thus a worthy end of any state’s foreign policy. Yet by shifting the phrase to its commercial equivalent, I want to stress the dark and calculating side of power politics that the vast majority of American leaders since the eighteenth century have so effectively practiced. And this includes that great liberal internationalist, Woodrow Wilson himself. For more than two and half centuries, American policy makers have typically conceived of “world” as meaning not the planet, but theirworld, the places on the earth that most determine their interests and concerns. And when they conceive of keeping that world “safe,” they are almost always thinking of how to ensure continued access to the goods and markets that will keep the economy strong and national security intact. If other powers help to promote and secure the expansion of this commercial world, great. Peace can prevail. But if others challenge America’s access to this world, watch out! Conflict and war may have to be chosen, even when other powers want a peaceful status quo. This book represents a sustained exploration of this and other such fundamental tensions, and the trade-offs in policy that go with them.

The book represents the third in an unplanned trilogy of books that seeks to offer a more dynamic view of international politics. When I was a second-year grad student, a professor of mine made an offhand comment that Kenneth Waltz’s famous Theory of International Politics had already shown us how great powers respond to outside forces (the “systemic” level in Waltz’s language), and that all interesting work in international relations would now come from the study of domestic politics and leaders (the “unit” level). Since I had already taken to heart critiques of Waltz’s book which underscored, above all, that it provided a far too static picture of the international system, I remember approaching him after class and stating that I thought there was still a lot more to be done at the systemic level. Most important, we needed to show how trends in systemic-level factors such as relative power and trade dependence force great powers to alter, often radically, their foreign policy behaviors. I recall he looked rather bemused, said something like “Good luck!” and walked off.

At the time, it was commonly believed that systemic or “neorealist” theories of power politics could only explain broad recurring patterns in great power relations, and that for any purchase on the specific behavior of states, one had to “dip down to the unit level” (to use a popular phrase from those days). I resisted this view then and have resisted it ever since. Great powers don’t simply face general and largely fixed systemic factors such as bipolarity (two large states) and multipolarity (many large states), as Waltz claimed. They also must deal with their specific relative positions within those polarities and how those positions are expected to change over time. They must answer questions such as: Who is bigger than whom, and by how much? Are we rising or declining in our level of power and economic dependence compared to other states in the pecking order? How have past decisions shaped current trends not just in military power, but also in economic and technological power? And perhaps most important of all, what do we expect will happen in the future, independent of

current trends, that might affect our ability to access the materials and markets we need to sustain our economic power base and thus our long-term national security?

The first book, TheOriginsofMajorWar, focused mostly on how dynamic trends in a state’s relative military power position caused it to act either moderately in foreign policy when it was inferior but rising in relative power and wished to buy time for future growth—or aggressively, given beliefs that it was declining from a strong current position and would be vulnerable to attack or coercion later. The second book, Economic Interdependence and War, took one step back in the causal chain. It showed how changes in a great power’s dependence on trade and financial flows, combined with expectations of the future commercial environment, could lead those in power to believe that the state was either rising or declining in long-term power. If expectations of future trade were positive, leaders could expect the state to grow in power, and would thus have more reason for moderate foreign policies. But if expectations turned sour and leaders came to see that others were either cutting the state off from trade and investment, or were likely to do in the future, then they could anticipate decline and be more inclined to hard-line policies to rectify the situation. In short, both books, drawing from the preventive war literature, demonstrated that anticipated decline is a major reason for great powers to turn to policies that lead to risky crises or war, with the second book also showing one very important reason for why leaders come to believe their states are indeed in significant decline.

This book builds on the theoretical arguments of the first two books, but also adds three new elements to help complete the larger dynamic argument I am developing. First, drawing from offensive realism but going beyond it, I argue that in any situation of anarchy where there is no central authority to protect states from the threatening actions of others, great powers have an incentive not only to seize opportunities to expand their territorial-military positions as a hedge against potential attacks down the road. They

also have an incentive to grab opportunities to expand their economic power spheres—the realms of trade and commerce they rely upon for continued growth—to reduce the chances that others will cut them off from future access to vital goods and markets. The fact that the United States and China today share this age-old drive to expand and protect their commercial realms goes a long way to explaining why in 2013 Beijing created the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to continue its “going out” policies from the 1990s and 2000s, and why Washington is so keen to ensure that the BRI does not hurt U.S. trade ties in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Indeed, the reason underlying China’s expansion outward parallels one of the foundational drives propelling American expansion after 1790— namely, the need for a larger sphere that could ensure continued access to raw materials, investments, and markets.

Yet the United States in its past, as with China over the last forty years, could not seize opportunities to increase its economic sphere without also considering the risk that this might upset other major powers. Smart great powers understand that overly hard-line behavior can cause a spiral of mistrust and hostility that may lead other states to reduce trade or even to engage in military actions to protect their own economic spheres. This is the second way that I extend past work. I seek to build a dynamic realist theory that integrates offensive realist insights on the need to expand as a hedge against the future with defensive realist insights on the need to worry that one might acquire a reputation for being a state with an aggressive, even pathological, character. Rational leaders will take into account both needs simultaneously as they make difficult decisions about the level of moderation or assertiveness in their foreign policies. And they will assess these needs in light of the severity of external changes in power and commerce, shifting to more hard-line policies either when they have reason to fear deep decline, or when they are rising but believe that without stronger policies, they will start to peak and decline in the near future (for the latter, think of the United States after 1895 and China after 2007).

The third new element is the book’s analysis of exactly how rational leaders interested in security go about making assessments of the other’s character assessments that, in conjunction with power trends, shape the way such leaders estimate the level of future threat arising from the external environment. Since these leaders are focused on the external environment—the other state’s character, and whether it is, like their state, rational and securityseeking, or something else altogether—this is not a “dipping down to the unit level” to explain why these leaders make the decisions they do. Rather, it is simply an unpacking of the various forces that shape the behavior of potential adversaries and that must go into any rational security-maximizing leader’s evaluation of the other’s future willingness to trade and to trade at high levels. This leader’s commercial expectations for the future, in short, come from somewhere, and in chapter 2 I unpack “the where,” using the assumption that nothingfromwithinthisleader’sstateis shaping his or her expectations. The expectations are shaped only by factors outside of the state. This assumption preserves the core assertion of all systemic realist arguments: namely, that rational leaders focused on national security are driven only by changes in the external situation the state faces, not by domestic pressures bubbling up “from below.” So while I later add complexity to my initial barebones argument, the book also bounds its argument in a way that gives the theory a strong measure of parsimony, and most importantly, allows it to be tested against the many theories that do start from unit-level domestic pressures to explain a state’s behavior.

The empirical focus of the book is on the main cases of American foreign policy over the last two and a half centuries. These cases, from the War for Independence to the Cold War, reveal something important. They show that American policy makers, far from simply responding to pressures from below or personal impulses, have regularly operated from a logic that I claim is a universal and overhanging “force from above” for all great powers, or at least for those in the post-1660 age of modern globalized commerce.

American leaders, in sum, are not naïve, nor are they all that different from the leaders of the European and Asian states explored in my first two books. In fact, they understand the commerce of power politics better than perhaps any other single group of state leaders over the last three centuries. Even if they cloak their policies in the warm and fuzzy language of liberal individualism and freedom, and occasionally find themselves shaped (and trapped) by this language, they prove themselves to be, first and foremost, careful calculators of national security through the lens of economic and commercial power. And for the most part, the world is a better place for it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS BOOK has a long history, and there are many people to thank for their help along the way. I first presented some of my initial and largely inchoate ideas on economic interdependence and international conflict back in my last year of graduate school at the University of Chicago, and I had a chance to return a quarter century later to present what I hoped was a much improved and better supported version of those ideas at the University of Chicago’s Program on International Politics, Economics, and Security (PIPES). John Mearsheimer and Charles Lipson were there on both occasions to offer direct and insightful comments on my overall logic and evidence. The dynamic realist theory that I present in this book may ultimately show that offensive realism should be best thought of as what physicists call a “special case” within a larger theoretical framework. But it was John’s version of offensive realism that convinced me that all great powers are forced by their uncertainty about the future to seek to expand their realms of power—in the military-territorial sense for John; and in the commercial-economic sense for me. And it was Charles’s graduate seminar on international political economy, which opened with Waltz’s seminal book, that pushed me to consider how the issues of the IPE and security subfields might be brought together within a single framework.

The rigor of the critiques offered that day at the PIPES seminar decisively shifted the direction of this book, and for that I want to also thank Paul Poast and Marc Trachtenberg and the graduate student participants who were there that day. Around the same time, I also greatly benefited from a seminar at MIT, where many of the case studies in the book were discussed. In particular, I wish to

thank Frank Gavin, Ken Oye, Roger Peterson, Barry Posen, Dick Samuels, and Stephen Van Evera for their great comments on that day. Also significant to the development of the argument were two presentations over two years I did at workshops on trade and conflict at the University of California, Irvine, organized by Michelle Garfinkel and Stergios Skaperdes of Irvine’s economics department. Feedback from Michelle and Stergios, as well as from Tommaso Sonno, helped me see more clearly how economists might go about formalizing my expectations-based argument. I’ve held off publishing the formal model that I developed out of those sessions for my next book. But the exercise itself served to hone the deductive logic behind my argument. I also want to thank Mike Beckley and Pat MacDonald for comments on my theoretical argument and the First World War chapter at the online 2020 APSA convention, Michael Mastanduno for his astute critique of the final draft, and Chris Carter, Gary Goertz, Stephan Haggard, and David Waldner for valuable discussions on the book’s methodological approach.

As the book was nearing completion, I had a chance to present chapters from the manuscript in three quite distinct venues. The theory chapters were presented to the Institute for Security and Conflict Studies seminar on international security at George Washington University. For suggestions that helped me refine many aspects of the final argument, I thank Alex Downes, Charlie Glaser, and Joanna Spear, as well as the attending GWU grad students. At Haifa University’s workshop on the future of the world order, sponsored by Israel Science Foundation, I received great feedback on my chapter on the future of U.S.-China relations from an amazing group of scholars, including Lars-Erik Cederman, Tom Christensen, Andrew Hurrell, John Ikenberry, Arie Kacowicz, Deborah Larson, Jack Snyder, and the workshop’s organizer, Benny Miller. The same chapter was also presented at a conference on the future of the U.S. dollar and the global economic order at Credit Suisse Bank in Zurich. I was surprised and delighted to have John Major, former prime minister of Britain, as my discussant. Sir John offered trenchant

comments about the practical implications of my trade expectations logic that significantly shaped the way I think about China’s ability to use the global system for its advantage.

At the University of Virginia I benefited greatly from a scrub session on the book and two later discussions organized through the Miller Center and the program on Democratic Statecraft. Will Hitchcock, David Leblang, Jeff Legro, Melvyn Leffler, Allen Lynch, John Owen, Len Schoppa, Todd Sechser, and Mark Schwartz provided incisive comments on specific chapters. I was also fortunate to receive feedback from a number of smart graduate students who directly shaped the book’s ultimate form: Josh Cheatham, Ghita Chraibi, Justin Gorkowski, James Kwoun, Yuji Maeda, Sowon Park, Sunggun Park, Angela Ro, John Robinson, Melle Scholten, Luke Schumacher, and Chen Wang. Six terrific undergrad students also offered great comments on the overall argument: Sam Brewbaker, Jenny Glaser, Lily Lin, Adrian Mamaril, Dao Tran, and Nick Wells. I’m also very grateful to four of my former grad students who took time away from their own busy academic careers to read the near-finished manuscript and help me hone the final product: Kyle Haynes, David Kearn, Mike Poznansky, and Brandon Yoder. And, of course, I need to thank four anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and my wonderful editors at Princeton University Press: Bridget Flannery-McCoy, who guided the book through the challenges of the review process and the crafting of the final product; and Eric Crahan, who first inspired me to write a book on American foreign policy building on the ideas from my previous book for Princeton.

Finally, I dedicate this book to my family: V. Natasha Copeland and my two amazing children Liam and Katya. They kept my spirit up through the long and winding road that was this book project: tolerating long hours in my room going through documents when I could have been playing more soccer, volleyball, or Clue with them; and helping me relax with Seinfeld, Harry Potter movies, and Beatles

albums when I seemed just a bit too stressed out. Couldn’t have done it without you!

ABBREVIATIONS FOR PRIMARY DOCUMENTS AND SOURCE

MATERIAL

CDJD TheCabinetDiariesofJosephusDaniels,1913–1921, ed. E. David Cronon (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1963).

CIA (CWE) AtColdWar’sEnd:U.S.IntelligenceontheSovietUnion andEasternEurope,1989–1991, ed. Benjamin B. Fischer (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 1999).

CIA (HT) CIAColdWarRecords:TheCIAunderHarryTruman, ed. Michael Warner (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 1994).

CR ChurchillandRoosevelt:TheCompleteCorrespondence, 3 vols, ed. Warren F. Kimball (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984).

CWIHP Cold War in International History Project. Washington, DC.

CWIHPB ColdWarinInternationalHistoryProjectBulletin, Issues 1–11 (Washington, DC, 1992–1998).

DAPS Containment:DocumentsonAmericanPolicyand Strategy, eds. Thomas Etzold and John Lewis Gaddis (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978).

DDEL Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, Kansas.

DS DimitrovandStalin1934–1943:LettersfromtheSoviet Archives, ed. Alexander Dallin and F. I. Firsov (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000).

DSB Department of State Bulletin (Washington, DC, various years).

ED TheEisenhowerDiaries, ed. Robert H. Ferrell (New York: Norton, 1981).

FCY Department of Commerce, ForeignCommerceYearbook (Washington, DC, various years).

FD TheForrestalDiaries, eds. Walter Millis and E. S. Duffield (New York: Viking, 1951).

FDRL Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York.

FP FederalistPapers.

FRUS ForeignRelationsoftheUnitedStates(Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, various years).

FTP ForthePresident,PersonalandSecret:Correspondence betweenFranklinD.RooseveltandWilliamC.Bullitt, ed. Orville H. Bullitt (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1972).

GOC TheGovernanceofChina:XiJinpingSpeeches, 4 vols. Beijing: Foreign Language Press.

HD Edward House Diaries, Yale University Library.

HSTL Harry S. Truman Library, Independence, Missouri.

IAFP IdeasandAmericanForeignPolicy:AReader, ed. Andrew Bacevich. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

IPCH IntimatePapersofColonelHouse, 2 vols., ed. Charles Seymour (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1926).

JFKL John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

JFKL NSF John F. Kennedy Library, National Security Files.

KR KhrushchevRemembers, trans. and ed. Strobe Talbott (New York: Little, Brown, 1972).

KR: LT KhrushchevRemembers:TheLastTestament, trans. and ed. Strobe Talbott (Boston: Little, Brown, 1974).

KT TheKissingerTranscripts:TheTop-SecretTalkswith BeijingandMoscow, ed. William Burr (New York: New Press, 1998).

LC Library of Congress.

LLWP TheLifeandLetterofWalterH.Page, 3 vols., ed. Burton Hendrick (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1926).

LTT TheLettersandTimesoftheTylers, 2 vols., ed. Lyon G. Tyler (New York: De Capo, 1970).

LWES LifeofWilliam,EarlofShelburne, ed. Lord Fitzmaurice, 2 vols., 2nd rev. ed. (London: MacMillan, 1912).

MH MasterpiecesofHistory:ThePeacefulEndoftheColdWar inEurope, eds. Svetlana Savranskaya, Thomas Blanton, and Vladislav Zubok (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2010).

MJQA MemoirsofJohnQuincyAdams, ed. Charles Francis Adams. 12 vols. (New York: Lippincott, 1875).

MP PapersofJamesMadison,PresidentialSeries, 11 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, various dates).

MPWW TheMessageandPapersofWoodrowWilson, 2 vols., ed. Albert Shaw (New York: Review of Reviews Co., 1924).

NA United States National Archives.

NPD Polk:TheDiaryofaPresident,1845–1849, ed. Allan Nevins (New York: Longmans, Green, 1952).

NSA (BC)

NSA (SE)

National Security Archive, TheBerlinCrisis,1958–1962 (Alexandria: Chadwyck-Healey, 1991, microfiche).

National Security Archive, TheSovietEstimate:U.S. AnalysisoftheSovietUnion,1947–1991(Alexandria, VA: Chadwyck-Healey, 1995, microfiche).

NYT NewYorkTimes, various years.

PD TheDiaryofJamesK.PolkDuringHisPresidency,1845–1849(Chicago: McClurg, 1910).

PTBF ThePoliticalThoughtofBenjaminFranklin, ed. Ralph Ketcham (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1965).

PV ThePriceofVision:TheDiaryofHenryA.Wallace,1946–1949, ed. John Morton Blum (New York: Houghton Mifflin,

1973).

PWW ThePapersofWoodrowWilson, 68 vols., ed. Arthur S. Link (Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press, various years).

TJW ThomasJefferson:Writings, ed. Merrill Peterson (Library of America).

TP TheTiananmenPapers, eds. Andrew J. Nathan and Perry Link (New York: Public Affairs).

UECW UnderstandingtheEndoftheColdWar:The Reagan/GorbachevYears, briefing book prepared by the National Security Archive for an oral history conference, Brown University, 7–10 May, 1998.

WWLL WoodrowWilson:LifeandLetters, 8 vols., ed. Ray Stannard Baker (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran, 1935).

WR WilsonandRevolutions,1913–1921, ed. Lloyd C. Gardner (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1982).

WSA TheWritingsofSamuelAdams, 3 vols., ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing (New York: G. P. Putnam’s).

YCY Department of Commerce Statistics, various years.

Introduction

THE WORLD has changed. Over the past decade, we have witnessed a distinct shift toward a renewed competition between the great powers. The green light that China seems to have given to Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and its subsequent saber-rattling over Taiwan six months later only served to reinforce concerns that have been building within the American foreign policy community since at least 2010. Just how intense this great power competition will become is uncertain. But what seems clear is that the optimism of the 1990s—when pundits and politicians alike saw growing economic interdependence and a rules-based international order as fostering long-term prosperity and peace between the United States, China, and Russia—is gone. In its place is talk of new cold wars and even military conflict. A rising China now seems willing to flex its muscles not just in its region but around the globe. Leaders in Beijing have not only challenged the U.S. navy for dominance in the South China Sea and the Pacific but also have signaled that they intend to extend China’s economic and political influence not just to Eurasia and Africa, but to an area Americans have always considered their backyard: Latin America. Russia, with a GDP the size of Italy, may have been reduced to the status of a middle power within the larger Sino-American competition. Yet its leaders’ very resentment of this fact, combined with Russia’s vast energy resources and the willingness to take military actions against neighbors—Georgia in 2008, Ukraine in 2014 and again in 2022— make Russia a continued threat to the global economic and political system. Even if Russian leaders cannot contribute to this system, they can undermine it, thereby interfering with the plans of both the

United States and China as they struggle for more influence and control around the world.

Russia’s continued ability to play the role of spoiler, however, should not distract us from a larger geopolitical fact: it is the bipolar struggle between the United States and China that is the new Great Game of the twenty-first century. Because both sides have nuclear weapons, we can expect leaders in Washington and Beijing to be inherently reluctant to engage in behavior that might raise the risk of actual war. And we can be thankful that at least one key lesson came out of the Cold War: that neither side can afford to push the system to anything that looks remotely like the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. This is the good news.

Yet as this book shows, there is also bad, or at least concerning, news. Great powers need continued economic prosperity to support their militaries and to ensure that they can maintain stability at home in the face of other states’ possible efforts to subvert it. They thus have an ongoing drive to expand their economic and commercial power spheres beyond their borders, and to support these spheres with strong navies and offensive power-projection capability. The American ongoing military presence in the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific regions since World War II and China’s growing naval support for its Belt and Road Initiative are only two obvious examples from recent history. This means that even in the nuclear age, great powers will struggle to improve their geoeconomic positions around the world. They will worry that their adversaries might decide to cut them off from access to vital raw materials, investments, and markets (“RIM”). In short, commercial strugglesfor prosperity and position remain an essential element of great power grand strategy, and these struggles can end up leading to crises that increase the probability of devastating war between the powers.

To see the inherent dangers, we need only remember that the Second World War in the Pacific came directly out of the tightening of an economic noose around Japan beginning in the early 1930s

and ending with a total allied embargo on oil exports to Japan in 1941. Chinese leaders are very much aware that the scenario of 1941, even more than that of 1914, is the one to avoid. Yet like Japanese leaders after 1880, they also know that China must work hard to extend its commercial presence, even at the risk of a spiral of hostility, if it is to sustain the growth that has made it the stable and secure superpower that it is today. This tension between needing to expand one’s economic sphere of influence and wanting to avoid an escalatory spiral that might restrict access to vital goods and markets is baked into the DNA of modern great power politics. It is a tension, as we will see, that the United States has faced repeatedly since the founding of the American republic. When it comes to explaining how competitions over commerce affect the likely behavior of great powers, there are two big questions that need to be examined in depth. What exactly is the role that commerce plays in driving states either toward more accommodating soft-line actions or toward more assertive hard-line postures, including the initiation of military containment and war against adversaries? And how significant is this role compared to the many other causes of cooperation and conflict that scholars have identified? This book seeks to answer these questions through a study of American foreign policy from the eighteenth century to contemporary U.S.-China relations. Yet this is not simply a book that explores the fascinating changes in American behavior toward the outside world since 1750 and then applies historical lessons to twenty-first century geopolitics. More than that, it represents a test of the relative explanatory power of the key theories of international relations (IR) for one very important country over time and across highly varied circumstances. These theories can be divided into two main groups: “realist” theories that focus on howthreatsexternalto a state will force almost any type of leader or elite group toward similar policies; and “liberal” theories that emphasize how forces internal to a state shape and constrain its behavior independent of the effects of the external factors. It is clear to nearly all IR scholars

that the United States, due to its strong liberal democratic foundations, poses a hard case for any realist theory, including the one offered here. We just expect American leaders to “think differently” about global affairs, and to be guided more by a sense of moral values, domestic pressures, and ideological ends than by traditional European notions of Realpolitik. So as that great philosopher (and sometime singer) Frank Sinatra might have said, if realist theory can make it here, it should be able to make it anywhere.

This book has three specific goals. The first is the building of a better, more dynamic realist theory of international relations, one that can resolve some of the problems with the two main versions of systemic realism in the field—namely, offensive realism and defensive realism. Systemic realists start with the common assumption that in anarchy, with no central authority to protect them, great powers will be primarily driven by factors that transcend domestic issues: factors such as differentials in relative power and uncertainty about the economic and military threats that other states pose, now and into the future. Yet offensive and defensive realists remain divided over the role of such systemic forces. By bringing together the insights of both forms of realism, the book establishes a stronger foundation for thinking about how states grapple with trade-offs presented by their external situations. Great powers do worry about building power positions that can handle problems that may arise in the future, as offensive realists stress. But they are also concerned that being overly assertive in the pursuit of this position can lead them into undesired spirals of hostility and conflict, as defensive realists emphasize.

By fusing these insights and then extending them into the realm of commercial geopolitics, this book goes beyond the limitations of current realist theory. It reveals the importance of two crucial variables to the decision-making process of any great power: the intensity of a state’s drive to extend and protect its economic power sphere to ensure a base-line level of access to key raw materials,

investments, and markets; and leader expectations about how willing adversaries are to allow the state future access to areas of trade and finance beyond its immediate power sphere. Modern realist theories tend to focus primarily on the military and territorial aspects of the great power security competition, downplaying the economic. These former aspects are important, to be sure. But by tying drives for commercial spheres of influence to expectations of trade beyond those spheres, I show that the overall trade environment and the way leaders anticipate changes in that environment regularly play an even more fundamental role in driving the foreign policies of great powers.

The second main goal of the book is to show that this new more dynamic and commercial approach to systemic realism can more than hold its own with the very case that has always proved problematic for realism: the United States and its foreign policies over the last two and a half centuries. Contemporary realists often buy into the liberal premise that America is exceptional, that it is founded in an ideology that rejected “Old World” aristocratic power politics in favor of the liberal pursuit of individual happiness, and that this outlook often leads the United States to act in ways that are contrary to realist predictions. Such realists are inclined to accept traditional arguments that the perceived need to spread democracy or protect liberal institutions abroad have been driving forces for why American leaders moved to a more globalist strategy after 1916 and why Washington continues to promote “liberal hegemony” long after the end of the Cold War. This starting assumption can lead offensive and defensive realists to give too much away to domestic-level explanations for American foreign policy behavior. To be sure, U.S. leaders and officials have at times sought to extend American liberalism’s reach when they could do so at low cost or when having liberal states in one’s sphere was seen as essential to countering the extension of an opponent’s sphere, as during the Cold War. And at certain points in U.S. history, as I show, bottom-up domestic pressures within a pluralist American state did indeed play important

roles in shaping policy. This book’s empirical chapters demonstrate, however, that the importance of commercial and power-political factors on American foreign policy behavior over the last two and a half centuries has been significantly underplayed, at least by political scientists if not always by neo-Marxist revisionist historians. From the formation of the republic to the current era, U.S. leaders, concerned about long-term national security, have been driven by a combination of commercial factors and relative power trends that have often overshadowed the ideological and domestic determinants of foreign policy. Americans, it turns out, are extremely smart and savvy realists, precisely because they have intuitively understood from the get-go the importance of dynamically fusing offensive and defensive realist insights with commercial power politics.

In the testing of its dynamic realist approach, this book does something unusual. Almost every book of historically based political science tries to set its theory against “competing arguments” in order to show that the causal factors posited by other theories are less useful in explaining the empirical cases of conflict and war than the pet theory of the book in question. This leads to endless cycles of debate as to which scholar’s factors were most critical to the understanding of controversial cases. My method is different. By recognizing that almost every case involves numerous key causal factors, I seek to identify the causal role that these factors are playing in a particular case, such as Woodrow Wilson’s decision to enter World War I or Franklin Roosevelt’s and Harry Truman’s policies that helped establish the post–World War II global order. Specifically, I ask questions such as: To what extent was a factor propellingthe leader to act, rather than acting as a facilitatingfactor for that action, or perhaps as a constraining factor that forced the postponement of the action? Was the factor merely acceleratingthe leader’s timetable for action or perhaps only reinforcing the original decision by giving added reasons to act, rather than being the factor that propelled the leader to act in the first place? As I discuss in chapter 2, by analyzing the various roles different causal factors play

within any particular “bundle” of factors leading to an important event in world history, we can provide nuanced understandings of history while at the same time isolating “what was really driving the event” as opposed to simply helping bring it on or change the manner in which it occurred.

This book examines almost all the cases of American foreign policy history after 1760 where there was a significant shift toward conflict or away from conflict with other states. Although this makes for a longer book, covering so many cases avoids biasing the research toward events that support one’s theory, while helping scholars and practitioners understand the full scope of causal forces that are at work across time and for very different sets of both domestic and international conditions. There are cases that do not work for my theory, such as the 1835–42 disputes with Britain over Canada, the inward turn from 1865 to 1885, and important aspects of America’s twenty-five-year involvement in Vietnam. Finding such problematic cases is a good thing. Since no theory in social science can (or should try to) explain everything, such negative cases serve to highlight—for both theorists and policy makers—the conditions under which a theory likely will and willnotbe useful.

This caveat notwithstanding, the broad sweep of cases covered in this book reveals an important pattern. From the get-go, American leaders were very concerned about maintaining and enhancing a core economic power sphere that would ensure access to key trading partners, initially in the neighborhood and then around the world. When these leaders were confident about future commerce and believed that trade was helping to build a strong and growing base of economic power, they were inclined to maintain peaceful relations with European and Asian great powers, even when ideological and domestic variables were pushing for conflict. When, however, their expectations of future trade turned sour and they saw others trying to restrict American access to the vital goods and markets needed for economic growth, these leaders almost invariably turned nasty and for national security reasons, not for

fear of the loss of elite power and wealth as left-leaning revisionist scholars typically argue. American decision-makers knew that without a forceful response to the other states’ policies, the longterm security of the nation would be put at risk. A weakened economy at home would have reduced the nation’s ability to protect its interests and might even leave the homeland vulnerable to attack or outside efforts to subvert the social order. Commercial ties, therefore, proved critical in pushing American leaders either toward peace or toward war, depending on whether their expectations of the future were optimistic or pessimistic and whether American and foreign diplomacy was seen as able to overcome mistrust and foster positive expectations into the future.

The empirical chapters begin with the War for Colonial Independence by adding a commercial explanation of the origins of the war to the ideological and domestic-political ones of traditional historiography. I seek to answer a puzzle that historians often ignore or downplay: why were the British North American colonies from 1763 to 1773 so reluctant to begin a war with the mother country, Britain, and yet why did they ultimately, and as a cohesive group, choose to undertake such a risky move? I argue that the war for independence was initiated not only to defend the concept of personal liberty a taken-for-granted notion since Britain’s Glorious Revolution of 1688—but to safeguard American commercial and economic growth in the face of London’s determined efforts to restrict the rise of an increasingly vibrant British North America. The continuation of the liberties and society that the colonists had come to value were seen as intimately tied to the continued development of trade; without the latter, the local power structures that protected the former would decline over the long term.

The subsequent conflicts of the young republic were also driven by fears for long-term commercial access and the economic growth needed to protect the unique American republican experiment. The War of 1812 may have been about the safeguarding of republicanism in a general sense, as some historians suggest. But it

was not a war chosen to protect the power of certain parties or to give western and southern “war hawks” more land for territorial expansion. Rather, President Madison reluctantly moved to war as a response to British policies that had shut U.S. products out of the European continent, policies that would have hurt the nation’s viability as a republic into the future. Similarly, President Polk did not initiate the war against Mexico in 1846 to extend slavery westward or to make his Democratic Party more popular, but to preempt an expected British move to acquire California and then use its ports to dominate the burgeoning trade with China and the Far East. If he could not secure this future trade, the nation itself would be more vulnerable to the economic and political predations of European powers.

By the late nineteenth century, the United States had become what it was not in 1812 or 1846—namely, a real player in the great power game. But its position was still vulnerable, albeit in a different way. To continue its industrial growth and to protect its increasing overseas trade—the growth of which was set in motion by the policies of the 1840s—U.S. leaders had come to see the importance of securing the American commercial position in the Caribbean and the Far East against the increasingly expansionistic powers of Britain and Germany. When a humanitarian crisis arose in Cuba after 1896, President McKinley was initially reluctant to act. By early 1898, however, with China being carved up by the European powers and a Central American canal needed to complete Alfred Thayer Mahan’s vision of the United States as a secure naval and commercial power, McKinley shifted gears. He became convinced that a war with Spain over Cuba would kill two birds with one stone: it would not only solve the humanitarian crisis but would allow the taking of Spanish territories needed to counter British and German commercial expansionism in the Far East and the Caribbean. Perhaps the most surprising case of the book is the 1917 U.S. intervention into World War I. Almost every historian of this intervention suggests that Woodrow Wilson was reluctant to enter

the war but felt forced to do so in order to have a say at the peace table and to help to reshape the world according to his liberal ideological vision—a vision that included promoting democracy and collective security as alternatives to traditional balance of power politics. The truth is much more complex and interesting. Wilson did harbor thoughts from his first days in office that the world would be a better place if it had more liberal democracies, especially ones trading freely with each other. But he also understood that global politics was about trade-offs. And if he had to choose between spreading democracy and protecting U.S. trade access, the latter would have to come first. It was only later in the war, with an allied victory on the horizon, that Wilson gave free rein to his more idealistic fantasy of remaking the world in the American image. Up until that point, his primary goal was to protect America’s economic power position in the western hemisphere and in Asia from threats of great power encroachment.

This broader objective was in place from his first month in office in March 1913 and it continually shaped his willingness to contain civil conflicts in Central America and the Caribbean prior to and during the European war. Wilson’s liberal mindset shaped his perception of which states were seen as the greatest threats to U.S. commerce through the Panama Canal and in the Far East: namely, the great rising neo-mercantilist nations of Germany and Japan. Spreading liberal democracy was at best an occasional means to his larger geopolitical ends. That the nation’s commercial security was foremost in his mind is shown by his great concern in mid to late 1916 that Britain had perhaps become the greatest threat to U.S. trade in the western hemisphere. Germany’s shift to unrestricted submarine warfare and its encouraging of a Mexican attack on the United States in early 1917 made it clear that war to ensure a British-French victory would be necessary. But when he told Congress on April 2 that the world must be made “safe for democracy,” his main goal remained Germany’s defeat and the denial of its penetration into the western hemisphere, not the more