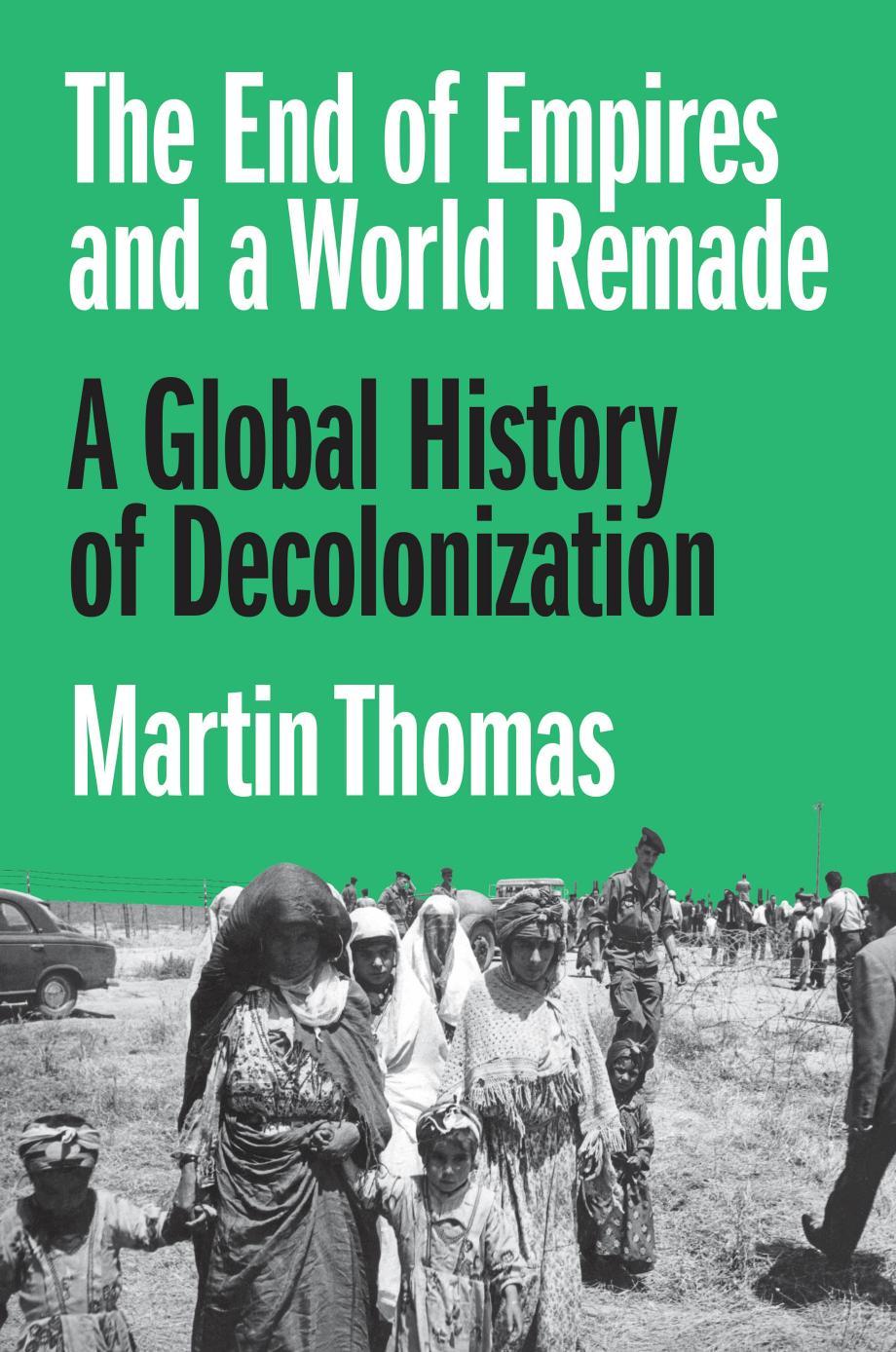

The End of Empires and a World Remade

a global history of decolonization

Martin Thomas

prince ton university press

prince ton & oxford

Copyright © 2024 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press princeton edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thomas, Martin, 1964– author.

Title: The end of empires and a world remade : a global history of decolonization / Martin Thomas.

Description: Princeton, New Jersey ; Oxford, United Kingdom : Princeton University Press, [2024] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023030324 (print) | LCCN 2023030325 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691190921 (hardback : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780691254449 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Decolonization—History. | Globalization—History. | Wealth—Moral and ethical aspects. | BISAC: HISTORY / World | HISTORY / Modern / 20th Century / General

Classification: LCC JV151 .T563 2024 (print) | LCC JV151 (ebook) | DDC 325/.309—dc23/eng/20230801

LC record available at https://lccn loc gov/2023030324

LC ebook record available at https://lccn loc gov/2023030325

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Priya Nelson and Emma Wagh

Production Editorial: Natalie Baan

Jacket Design: Chris Ferrante

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Carmen Jimenez and Alyssa Sanford

Copyeditors: Gráinne O’Shea and Katherine Harper

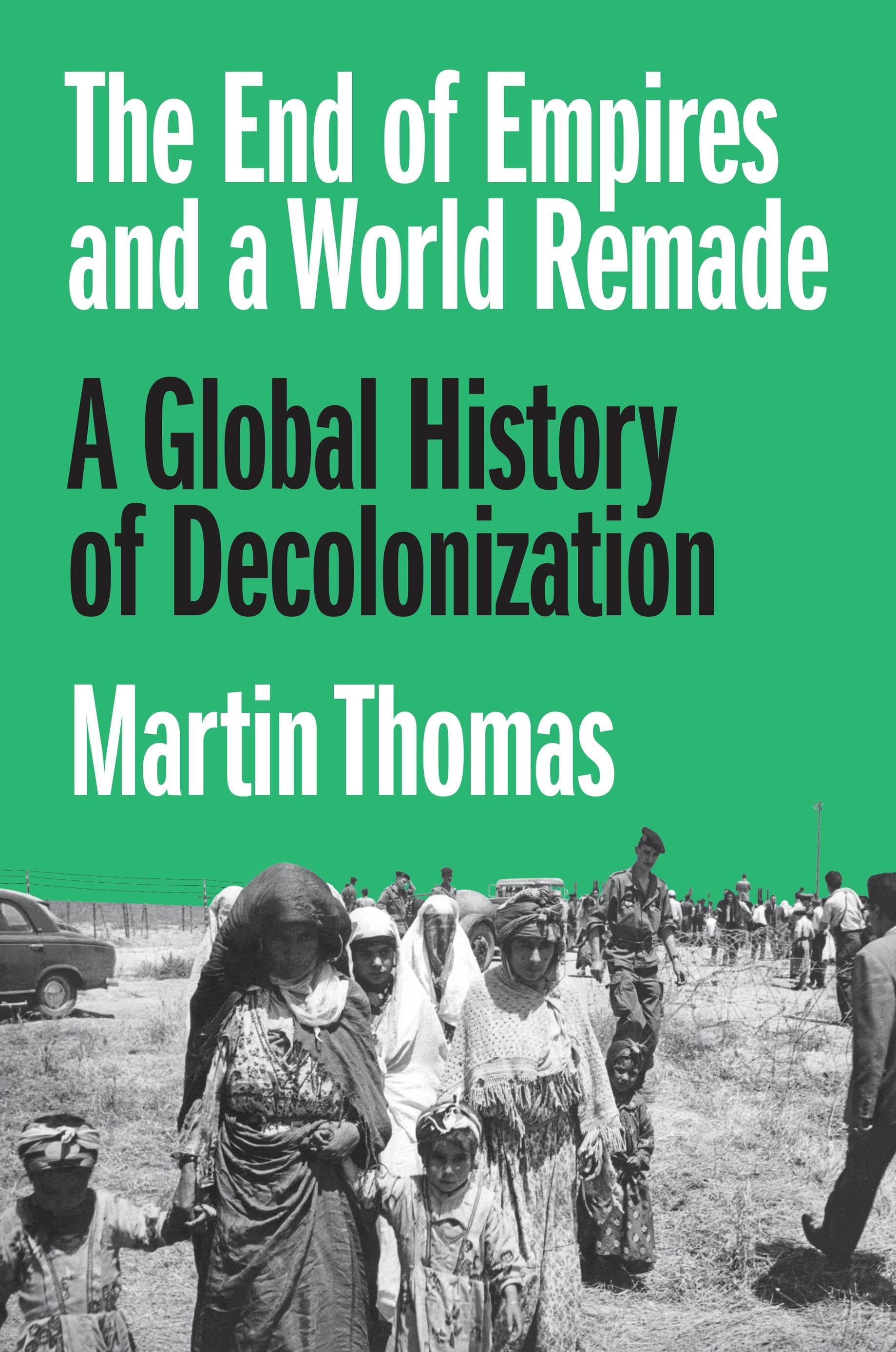

Jacket image: The first Algerian refugees from Tunisia wait to cross the electrified border in eastern Algeria on May 30, 1962, as they return to their country. Source: Getty Images.

This book has been composed in Miller

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

chapter 12 Political Economies of Decolonization and Development

chapter 13 Political Economies of Decolonization II: The 1950s and 1960s

chapter 15 Endgames? Decolonization’s Third-World Wars

abbreviations and terms

aapso Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization, founded 1957.

ackba American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive.

aef Afrique Equatoriale Française: the federation of French Equatorial Africa, comprising the French Congo, Oubangui- Chari, Gabon, and Chad. The former mandate of French Cameroon, declared a UN trust territory in 1945, was economically tied to AEF.

afd Agence française de développement.

afpfl Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (Burma).

aln Armée de Libération Nationale, armed wing of the Algerian FLN.

anzus Australia–New Zealand–United States defense treaty, 1951.

aof Afrique Occidentale Française: the federation of French West Africa, comprising Senegal, Mauritania, French Soudan, Niger, Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire), Guinea, Dahomey, and, from 1948, Upper Volta (Haute-Volta). Federal authorities in Dakar also retained links with Togo, another former mandate, made a UN trust territory in 1945.

arc Asian Relations Conference (India, 1947).

assra Assistances Sanitaires et Sociétés rurales auxiliaires (in Algeria).

au African Union, launched in 2002 as successor to the OAU.

bmeo British Middle East Office.

bna British Nationality Act (1948).

caf Central African Federation, established 1953; dissolved 1963.

[ viii ] a bbreviations and t erms

cao Committee of African Organizations (African student group in Britain).

cdc Commonwealth Development Corporation (British, established 1947).

cgt Confédération Générale du Travail, French trade union confederation.

cicrc Commission Internationale Contre le Régime Concentrationnaire (Commission against the Concentration Camp Regime).

comecon Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Soviet-directed).

coremo Comité Revolucionário de Moçambique.

cpc Colonial Policy Committee (of the British government).

cpgb Communist Party of Great Britain.

cpp Convention People’s Party, founded in the Gold Coast, 1949.

crit Conference (of Asian Countries) on the Relaxation of International Tension, 1955.

cro Commonwealth Relations Office.

dgs Direção-Geral de Segurança (Portuguese security service).

doms Départements d’outre-mer, French overseas departments, post-1946.

drv Democratic Republic of Vietnam, established in Hanoi in 1945.

dst Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire, French internal security service.

ecowas Economic Community of West African States.

eec European Economic Community.

efo Economic and Financial Organization (of the League of Nations).

emb Empire Marketing Board, (British) in existence from 1926 to 1933.

a bbreviations and t erms [ ix ]

emsi Équipes Médico-Sociales Itinérantes (in Algeria).

ena Étoile Nord-Africaine: North African Star; Algerian nationalist party, established 1926.

eoka Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston: National Organization of Cypriot Fighters.

fao Food and Agriculture Organization (of the United Nations).

fco Foreign and Commonwealth Office (British).

fides

Fonds d’Investissement pour le Développement Économique et Social: Economic and Social Development Fund, set up in 1946.

fln Front de Libération Nationale, Algerian National Liberation Front, founded in 1954.

frelimo Frente de Libertação de Moçambique.

gatt General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

gco General Counter- Offensive (in Vietnam).

giedc Groupement internationale d’études pour le développement du Congo.

gpra Gouvernment Provisoire de la République Algérienne (Algerian provisional government, established 1958).

g77 Group of 77 (coalition of developing countries).

Haganah Zionist paramilitary organization.

Histadrut Federation of Jewish Labor.

ibrd International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

icftu International Confederation of Free Trade Unions.

icp Indochinese Communist Party, formed in 1930.

icrc International Committee of the Red Cross.

ilo International Labour Organization.

ilrm International League of the Rights of Man.

imf International Monetary Fund.

ina Indian National Army.

[ x ] a bbreviations and t erms

Irgun National Military Organization in the Land of Israel. Tzva’i Le’umi

ito International Trade Organization.

kau Kenya African Union.

lai League against Imperialism.

Lehi b’Herut Fighters for the Freedom of Israel. b’Yisrael

lnho League of Nations’ Health Organization.

l zvn Liga zur Verteidigung der Negerrasse: ‘League for the Defense of the Negro Race’.

Mau Mau Kenyan anticolonial movement, sometimes translated as ‘the ravenous ones’.

mca Malayan Chinese Association.

mcf Movement for Colonial Freedom (British pressure group).

mcp Malayan Communist Party.

mdp Masai Development Plan (in Kenya).

mdrm Mouvement démocratique de la rénovation malgache, Madagascar nationalist party, founded in 1946.

meo Military Evacuation Organization (Indian subcontinent), founded September 1947.

mna Mouvement National Algérien, rival to the FLN, led by Messali Hadj.

mpaja Malayan Peoples Anti-Japanese Army, largely ethnically Chinese guerrilla force in Malaya in the Second World War.

mps Minorities’ Protection Section (of the League of Nations).

mrla Malayan Races’ Liberation Army, armed wing of the Malayan Communist Party.

mrp Mouvement Républicain Populaire, French Christian Democrat Party, founded in 1944.

mss Malayan Security Service.

a bbreviations and t erms [ xi ]

mtld Mouvement pour le Triomphe des Libertés démocratiques, Algerian nationalist party, forerunner to the FLN.

naacp National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, founded 1909.

nam Non-Aligned Movement.

nato North Atlantic Treaty Organization, set up in April 1949.

nieo New International Economic Order.

oas Organisation de l’Armée Secrète, reactionary counterterror group.

oas Organization of American States, established in 1948.

oau Organization of African Unity, founded 1963.

os Organisation Spéciale, pre-FLN paramilitary group linked to the MTLD.

otc Overseas Trade Corporation (British, founded 1957).

paigc Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde.

pavn People’s Army of Vietnam.

pcf Parti Communiste Français, French Communist Party, established in 1920.

pide Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado (Portuguese).

pla People’s Liberation Army, national army of the People’s Republic of China.

pmc Permanent Mandates Commission (of the League of Nations).

pmi Protection Maternelle et Infantile (in French Morocco).

ppa Parti Populaire Algérien, Algerian Popular Party, founded in 1937.

psd Parti social démocrate: [Malagasy] Social Democratic Party.

[ xii ] a bbreviations and t erms

raf Royal Air Force.

rda Rassemblement Démocratique Africain, established in 1946.

renamo Resistência Nacional Moçambicana.

rf Rhodesian Front.

rpf Rassemblement du Peuple Français, Gaullist movement, launched in 1947.

saa Syndicat Agricole Africain: West African planters’ association.

sas Sections Administratives Spécialisées, army civil affairs specialists in Algeria.

sau Sections Administratives Urbaines (urban counterpart to the SAS).

sdece Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage, French overseas intelligence service, broadly equivalent to Britain’s MI6.

seato South East Asia Treaty Organization, established 1955.

sfio Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière, unified French Socialist Party, founded in 1905.

sig Special Investigations Group (of the British Ministry of Defence).

sip Sociétés indigènes de prévoyance (French Empire rural credit agencies).

tom s Territoires d’outre-mer: French overseas territories, post-1946.

uctan Union Générale des Travailleurs d’Afrique Noire.

udc Union of Democratic Control, British pressure group founded in 1914.

udhr Universal Declaration of Human Rights (December 1948).

udi Unilateral Declaration of Independence (by Southern Rhodesia).

a bbreviations and t erms [ xiii ]

udma Union démocratique de Manifeste algérien, Algerian proto-nationalist group.

ugcc United Gold Coast Convention, founded in 1947.

umhk Union Minière du Haut Katanga.

umno United Malays National Organization.

unctad United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

unesco United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

unia Universal Negro Improvement Association, established 1914.

unicef

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund.

unita União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola.

unrwa United Nations Relief and Works Agency.

unscop United Nations Special Committee on Palestine.

upa Union of Angolan Peoples.

upc Union des Populations du Cameroun.

vnqdd Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dong: Vietnam National Party, founded in 1927.

vwp Dang Lao Dong Viet Nam: Vietnamese Workers’ Party, designation for the Vietnamese Communists from 1951.

wfdy World Federation of Democratic Youth.

wftu World Federation of Trade Unions.

who World Health Organization.

zanu Zimbabwe African National Union.

zapu Zimbabwe African People’s Union.

acknowl edgments

there’s a lot of book ahead of us, so I’ll keep my acknowl edgments short. Although brief, every thank you that follows is heartfelt. Each of the groups and individuals mentioned has been fundamental in getting me over the finishing line of a project that, in many ways, goes back over thirty years. I owe huge debts of gratitude, first to the Leverhulme Trust, which funded Major Research Fellowships and an International Research Network that made the research and writing feasible. Another UK-based scholarly funder, the Independent Social Research Foundation, supported a project on imperialist humanitarianism that brought me into lasting contact with the inspiring community of ISRF fellows in social sciences and the humanities. I’ve had constant support from colleagues and students at the University of Exeter, whose Centers for Imperial and Global History and for Histories of Violence and Conflict have become terrific forums for the exchange of ideas.

A wonderful 2019 semester at the Netherlands Institute of Advanced Studies in Amsterdam, as part of the ‘Comparing the Wars of Decolonization’ project team led by Thijs Brocades Zaalberg and Bart Luttikhuis, transformed my thinking about colonial violence. For that, plus their great company, I thank all the team members, including Pierre Asselin, Huw Bennett, Roel Frakking, Brian Linn, Peter Romijn, Stef Scagliola, and Natalya Vince. (And thanks again for the All Bran, Natalya’s mom.) Visitors to the project, including David Anderson, Saphia Arezki, Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo, Raphaëlle Branche, Elizabeth Buettner, Rémy Limpach, and Kim Wagner, helped me better understand how to approach decolonization conflicts. An international research network on ‘Understanding Insurgencies’, co-organized with my Exeter colleague Gareth Curless, provided the platform for seven workshops over three years that, again, proved how much we learn as historians of empire from collaborative research across countries and disciplines: a special thank you to everyone who took part. Closer to home, it’s been a pleasure and a privilege getting to know Alex Zhukov and Tanya Zhukova.

Turning ideas into books needs the help of a great press. The team at Princeton has been exemplary: generous with their time, thoughtful with their comments, and patient with their author. To my editor, Priya Nelson, production assistant, Emma Wagh, production editor, Natalie Baan, and

[ xv ]

[ xvi ] a cknowledgments

copyeditors, Gráinne O’Shea and Katherine Harper, a massive thanks. I’m also indebted to Tarak Barkawi and Nicholas White. Their forensic analysis as press readers was matched by their generosity of spirit in suggesting improvements. I could not have asked for more. I thank Getty Images for awarding image rights. And thank you to my co-authors, Andrew Thompson and Roel Frakking, and to Cambridge University Press, Cornell University Press, and Oxford University Press for allowing me to use elements from chapter contributions I’ve published with them, credited below.

A last word to Suzy: thanks for everything; you’re the one.

Martin Thomas, “The Challenge of an Absent Peace in the French and British Empires after 1919,” in Peacemaking and International Order after the First World War ed. Peter Jackson, William Mulligan, and Glenda Sluga (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2023), 151–75.

Roel Frakking and Martin Thomas, “Windows onto the Microdynamics of Insurgent and Counterinsurgent Violence: Evidence from Late Colonial Southeast Asia and Africa Compared,” in Empire’s Violent End: Comparing Dutch, British, and French Wars of Decolonization, 1945–1962 ed. Thijs Brocades Zaalberg and Bart Luttikhuis (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2022), 78–126.

Martin Thomas and Andrew Thompson, “Rethinking Decolonization: A New Research Agenda for the Twenty-First Century,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Ends of Empire ed. Thomas and Thompson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 1–26.

Martin Thomas, “Decolonization and the Civilianization of Violence,” in The Oxford Handbook of Late Colonial Insurgencies and CounterInsurgencies ed. Martin Thomas and Gareth Curless (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 141–60.

Ending Empire and Remaking the World

december 1963 found b arbara Castle in Kenya. Labour Party politician, writer, and parliamentary voice of Britain’s leading anticolonial pressure group, the Movement for Colonial Freedom, Castle arrived in Nairobi on the 10th. She was there to celebrate. Hours after her arrival, Castle attended a multiracial ‘civic ball’. Diary entries rec ord her thrill at what was to come: ‘Atmosphere so gay: races mixing equally and naturally— so diff. from the old Kenya! I twisted and jived uninhibitedly and I felt like a 20 yr old’.1 The next day brought wildlife-watching before another night of celebration. The evening began with drinks on the terrace of the Lord Delamere Bar, once an exclusive settler haunt, now, in Castle’s oddly colonialist metaphor, the ‘Piccadilly Circus of a world society’.2 Six hours later, Castle was an honored guest at the Uhuru (Freedom) Stadium for Kenya’s independence ceremony. Other British dignitaries included Anglican priest and antiracism campaigner Michael Scott, Oxford anthropologist and Colonial Office adviser Margery Perham, the departing colonial governor Malcolm MacDonald, and Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh. The duke took the salute of a King’s African Rifles parade marching to the strains of “Auld Lang Syne.” Jarringly inappropriate, the traditional invocation of a freezing Scottish new year was meant to convey the warmth between hosts and visitors. Besides, the regimental band knew it well— they were required to play it often. The music done, MacDonald offered Britain’s congratulations to Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, as the Union Jack was lowered for the last time on the stroke of midnight, December 11, 1963.3

The imperial choreography of an end to empire was one thing, but the lived experience, for ordinary Kenyans and honored guests alike, was rather different. Castle arrived late. She got stuck in a traffic jam of cars and minibuses convoying people to the stadium. Anxious not to miss out, she tore her clothes clambering over a fence, to find thousands already celebrating with singing and dances of their own. The band was drowned out. So too was the Duke of Edinburgh’s whispered aside to Kenyatta just before that flag came down: ‘Want to reconsider? There’s still time’.4

Ten years earlier, thousands of Nairobi residents had faced beatings, expulsion, and internment, accused of association with Mau Mau in a war against British colonialism. Kenyatta had been locked up for much of it but emerged on the side of the conflict’s ‘loyalist’ winners.5 Was December 11, 1963, a celebration of victory or the burial of a traumatic, divisive past? Arguably, it was neither. Beyond Kenya, ceremonies of this type were commonplace in the early 1960s.6 Formal declarations of independence were supposed to mark something definitive, a societal transition from one political condition, colonial dependency, to another, sovereign independence. Liberation from discriminatory foreign rule was meant to enable authentic freedom, both individual and collective.7 But decolonization was not a single event, once accomplished, forever done. Processes of ending empire and breaking with colonialism were messier, more attenuated and less final than independence ceremonies suggested.

Ending Empire?

Empires, until relatively recently, were everywhere.8 A minimalist definition of what they were is the foreign enforcement of sovereign political control over another society in a delimited territorial space. But that’s not enough. Describing the varie ties and degrees of imperial influence, and the lived experience of empire, demands more than such coldly geopolitical terms. Eurocentric or Westphalian notions of sovereign independence tied to statehood and international legal recognition were difficult to translate to colonial spaces, where relational politics, religious loyalties, and kinship obligations suggest more layered, pluralistic attachments to multiple sources of authority.9 Economic influence, sometimes exercised without ‘formal’ political dominion, could be crucial. Most importantly, the ‘political control’ over territorial space fails to capture the fragilities of colonial governance, its unevenness across vast geographical areas whose territorial limits were often porous. Movements of people, goods, money, ideas, and beliefs were impossible to confine within a single colonial

polity.10 The tensions between movement and restriction, between cosmopolitanism and compliance, between private spheres of life beyond colonialism and lives constrained by it, would lend decolonization local variegations that nationalist political schema rarely captured.

For most of those affected by it, opposing empire was more visceral than ideological. The constraint of rights and opportunities was part of something bigger, the restriction of freedoms—to move, to associate, to own certain things, to practice one’s culture. These limitations were, and are, what makes colonialism possible. More a pervasive social condition than an exact political relationship, the colonialism of empire describes not just the maintenance of unequal political relations between a controlling imperial power and a dependent society, but the socioeconomic hierarchies, the cultural discriminations, and the racial inequalities such relations entail.11

Imperialism, understood as the ideas and practices of empire, lingers on. So do numerous silences and occlusions surrounding it, a consequence of what one analyst has described in a British governmental context as a systematic ‘deprioritizing of empire’. 12 Empires may no longer dominate global politics, but multiple colonial legacies endure. 13 Some are so invidious that they cry out for our attention: acute inequalities of global wealth, uneven access to the resources essential to human security, and the persistence of societal racisms. In other ways, searching out colonialism’s imprint seems easier. Less than half a century ago, foreign colonial rulers were still geographically widespread. The job is to work out how much changed when they left or were compelled to go. Elsewhere, empire’s impact is more oblique but remains imminent even so. From the use of land and the extraction of resources to borders and administrative structures, the language and patterns of global commerce, and the social and cultural identifications that people make, our contemporary world is inflected with recent imperial history.

This is where decolonization comes in. It stands alongside the twentieth century’s world wars, the Cold War, and the longer arc of globalization as one of the four great determinants of geopolitical change in living memory.14 The chapters to come suggest that decolonization was one globally connected process. Their cumulative argument is that we cannot understand decolonization’s global impact by examining individual empires or single colonial histories. Decolonization worked as much across nations, empires, and boundaries as within them. It proceeded by forging new global connections that reordered relations between First World, Second World, and Third.15 Colonialism’s devastating impact on

the ‘Fourth’ World of indigenous peoples and first nation communities was replicated in their sublimation within a broader ‘Third World’ designation. Decolonization, indeed, is why this three worlds construction came to be used in the first place. Usually portrayed as disintegrative, decolonization was anything but. Instead, decolonization is intrinsically connected to globalization, whether that is conceived as a process of increasing global connectivity or as competing ideological visions of how the world might be reconfigured through economic, cultural, and political exchange. The conditions and possibilities of globalization—or rival globalizations—assured the supporters of decolonization greater access to essential resources, to wider networks of influence, and to global audiences. But globalization could also hinder. Its neoliberal variant has reinforced economic inequalities and facilitated imperial forms of influence, making decolonization harder to complete.16 The first section of this book tries to explain why the deck was so heavily stacked against newly independent nations.

Ending empires occasioned many of the longest wars of the twentieth century, reminding us that decolonization was more than a political contest.17 It energized different ideas of belonging and transnational connection, of sovereignty and independence and the struggles necessary to achieve them. Late colonial conflicts spurred other connections as the colonized ‘weak’ built transnational networks of support to overcome the military and economic advantages of ‘strong’ imperial overseers. Insurgencies spread. The counterinsurgencies that followed triggered rights abuses whose global exposure left empires shamed and morally disarmed. In its violence as in its politics and economics, decolonization reshaped globalization just as globalization conditioned decolonization.18

This book is about what brought down European overseas empires, whose constituent territories were separated by oceanic distance but conjoined by global processes of colonialism. The opening three chapters deal with ideas and concepts. The first concentrates on what decolonization means and when it occurred, examining its twentieth-century chronology. The second chapter addresses the relationship between decolonization and globalization. And the third considers alternatives to decolonization, revisiting debates over the rights and wants of people living under colonial rule. Scholars familiar with the panoply of reformist engagement with empire, with proposals for different governing structures and pooled sovereignties, and with diverse viewpoints that were never simply ‘anticolonial’ remind us that decolonization was not a foregone conclusion.19 We know that claims to nationhood built on various models of sovereign independence eventually prevailed. But what contexts made these outcomes more likely?

My attempt to answer this question accounts for the transition from part I to part II of this book.

Beginning with chapter 4, my attention shifts toward factors which, it seems to me, were crucial in triggering European colonial collapse. Briefly summarized, they are these:

• issues of political economy;

• the global weight of anticolonial opposition and rights claims;

• the transformative aftereffects of two world wars;

• territorial partitions;

• the violence of those fighting to end empire and those fighting to keep it; and

• the vulnerability of the colonial civilians at the epicenter of decolonization.

The list could be much longer. Questions of identity and culture, gender and ethnicity, ideology and ethics are each central to the factors I’ve highlighted. So are other, perhaps more familiar matters of geopolitics, international organization, and a globalizing Cold War. It would also be wrong to assume that identifying causes makes prioritizing among them easy. The problem, of course, is that the conventions of historical analysis demand such differentiation. So the dilemma for anyone attempting to compare how and why European empires were brought down is twofold: first, to distinguish between major and minor in teasing out causes, and, second, to avoid the oversimplification of a complex historical process by ascribing too much transformative power to a single factor. This is a difficult line to tread. Decolonization was pluri-continental, supranational, and globally comparable at the same time as it was locally specific and highly contingent.20 These traits are not contradictory. Its local iterations might defy generalization, but decolonization had distinctive patterns nonetheless. I’ve tried to strike a balance here. I make frequent use of archival sources to make the case, although the work of other scholars in history and social science figures prominently throughout. My aim in identifying particular triggers and their consequences is to keep those global patterns in view without losing sight of the people caught up in the decolonization process.

Remaking the World?

Placing decolonization within a temporal frame, beginning with the First World War and ending somewhere in the 1970s, makes good sense insofar as the great majority of formal decolonizations occurred at some point

within these years.21 But there are gaps. Colonies still exist. Economic dependencies are real. Attitudinally and emotionally, colonialism is with us still.22 Twentieth-century decolonization was transformative even so. It lent political coherence to the global South as a transregional bloc united in its rejection of the white racial privilege that for so long underpinned rich-world politics. As applied to Africa, Asia, and Latin America, that shorthand term ‘global South’ encompassed a wide spectrum of nations and dependencies, from middle-income countries to colonial territories. For all that, the global South was identifiable less by geography than by shared opposition to the colonialist interventions and discriminatory practices of imperial powers. For its constituent territories, ending empire was integral not just to the rights claims or freedom struggles of par ticular nations, but also to changing the north–south dynamics of rich world and poor. As historian Angela Zimmerman has suggested, by the early 1900s the global South was evident in a ‘colonial political economy’ at once tied to, but kept distinct from, rich-world capitalist economies by the racial hierarchies of colonialism. Put differently, it was not the equator but rather what W. E. B. Du Bois identified as ‘the color line’ that separated global South from global North.23

In the 120 years or so since Du Bois mapped out the global color line, the collapse of formal colonial control, the end of empires, or, as specialists usually term it, decolonization has reshaped the world’s political geography. Its impact on political culture—on the ways regimes, governments, and social movements justify their behavior—has been equally profound. Whatever the arguments about its finality, rejecting colonialism was the necessary precursor to the creation of new nation-states, new ideological attachments, and new political alignments in much of the global South. For some, that rejection did not produce support for decolonization but, rather, for alternate claims to political inclusion, social entitlements, and cultural respect: aspirations thought to be achievable within rather than beyond the structures of empire. For others, anticolonialism demanded a fuller decolonization—of politics, of economies, and of minds. These more radical and rejectionist objectives implied profound social transformations, placing decolonization within a spectrum of revolutionary change.24

The historical rec ord lends weight to this revolutionary reading of events. Decolonization fostered bold experiments in social, racial, and gender equality. It changed prevailing ideas about sovereignty, citizenship, and collective and individual rights.25 Its contestations stimulated new types of social activism, innovative forms of international cooperation between governments, and a global surge in transnational networking

between nonstate actors, activist groups, and those that colonialism otherwise excluded.26 Some of the ideas involved were locally specific, but many more were shared, borrowed, or adapted among the peoples caught up in fights for basic rights, for self-determination, for the dignity of cultural recognition.27

So where are we? If decolonization was once depicted in reductive terms as the sequence of high-level reforms leading to a definitive constitutional transfer of power, it now risks being freighted with so many elements that it loses coherence. At one level, this book’s purpose is thus a basic one: to rethink what decolonization is. The end of empires catalyzed new international coalitions and diverse transnational networks in the second half of the twentieth century. It triggered partitions and wars. It challenged ideas about individual and collective rights, and which mattered most. And it shaped the ways in which globalization gathered momentum. Decolonization, in other words, signifies the biggest reconfiguration of world politics ever seen.