Introduction

Intheyear1931,IwasmarriedtoNassifD.,ashoemakerfromJaffa, andhadfromhimsixchildren,fourgirlsandtwoboys.During 1944–1945,myhusbandbecameillandthenlosthismind;Your Excellencymayallowmetostatethatapartfromourbeingina completestateofdistress,myhusbandbeatsmeandthechildren practicallyeverynightandhasonmanyoccasionstriedtoburnthe hutinwhichwelive.IhaveinvainapproachedthePublicHealth DepartmentandthePoliceAuthoritiesinJaffatosendhimtoa LunaticAsylumbuttheyhavefailedtodoso.Ithereforehavebeen advisedtoreferthemattertoYourExcellencyandrespectfullytrustthat YourExcellencywillorderthedepartmentconcernedtoactassoonas possiblebeforeitistoolate,asIamsurethatoneofthesedays,my childrenandmyselfwillbethevictimsofalunaticman 1

InDecember1945,ZmurudD.wroteindesperationtotheHigh CommissionerofPalestine,thehighest-rankingofficialintheBritish mandategovernmentthathad,bythen,governedPalestineforover twodecades.Experiencingviolenceatthehandsofahusbandwhohad ‘losthismind’,shehadalreadysoughthelpfromthedepartmentof healthaswellasthepoliceinJaffa,buttonoavail;petitioningtheHigh Commissionerdirectlywasherlastresort.Zmurud’sgambityielded results,thoughnotinaformshehadanticipated.Ratherthanadmit herhusband,thedepartmentofhealtharrangedforhimtobeoffereda courseofelectro-convulsivetherapyatthegovernmentmentalhospital nearJaffaasanoutpatient.Whilethismeanttheovercrowdedhospital couldtreathimwithout fillingoneoftheirpreciousbeds,these ‘inoculations ’– asZmuruderroneouslycalledthemafewmonthslater – made herhusband ‘veryfurious ’.Everytimehereturnedhomefromthe hospital,hebeatherandthechildren,andpouredkeroseneovertheir mattressesinhisattemptstoburndownthehouse.Facedwiththis

1 ZmurudD.,Jaffa,toHighCommissioner,1December1945,IsraelStateArchives [ISA]M6628/6.

2

unbearablesituation,ZmurudwroteonceagaintotheHigh Commissionertodemandthatherhusbandbesenttoamentalinstitutionbeforeitwastoolate.2 Thistime,shewasassuredthather husbandwouldbeadmittedwhenavacancybecameavailable3 – though thereisnorecordinthecolonialarchiveofwhen,ifatall,thismayhave cometopass.

ThestoryofZmurud’sencounterwithmentalillnessisjustoneofthe manyIhavecomeacrossinthearchiveoftheBritishcolonialgovernmentthatruledPalestinefromtheendoftheFirstWorldWaruntil 1948,thoughthatdoesnotdiminishthepoignancyofhercallsforhelp underharrowingcircumstances.ThesestoriesunfoldedagainstthebackdropofapivotalperiodinthehistoryofmodernPalestine.Acrossthree shortdecades,formerOttomanterritoriesintheLevantwerepartitioned andparcelledoutasBritishandFrenchmandatesundertheauspicesof thenewlycreatedLeagueofNations;aBritishadministrationformally committedtothecreationofaJewishnationalhomeinPalestinewas imposedagainsttheexpressedwishesoftheindigenousArabpopulation; andaPalestiniannationalmovementemergedwhich,bythelate1930s, wascapableofsustaininganunprecedentedgeneralstrikeandyears-long revoltagainstboththeBritishandZionism.StorieslikeZmurud’sare easytooverlook,againstthebackdropofthesemomentousdevelopmentsandintheknowledgethatthemandateperiodwouldcometoa suddenanddramaticendin1948withtheestablishmentoftheStateof IsraelandthePalestinian nakba,orcatastrophe,ofdisplacement anddispossession.

Yetthesestories – ofhowpeoplelivinginmandatePalestinenegotiatedbothmentalillnessandthecolonialstateatthesametime – areat theheartofthisbook.Theymatterintheirownrightandontheirown terms:Zmurud’spetitions,whichspeakpowerfullytothewayherand herfamily’slifehadbeenturnedupsidedownbymentalillness,make thisplain.Thesestoriesalso,however,holdoutchallengestoandpossibilitiesforthestudyofmandatePalestine,thehistoryofpsychiatry,and ourunderstandingofhowPalestineconnectsuptowiderregional, imperial,andglobalhistories.Bycentringthesocialandculturalhistory ofmentalillnessinmandatePalestine, MandatoryMadness makesan interventionineachofthesethreeareas.First,itprovidesadistinctive newaccountofhowmandateofficials,EuropeanJews,andPalestinians –Muslim,Christian,andJewish – interrelated.StorieslikeZmurud’scan revealtheintimatewaysinwhichthebigpoliticaltransformationsofthe

2 ZmurudD.,Jaffa,toHighCommissioner,2May1946,ISAM6628/6.

3 A/DirectorofMedicalServicestoZmurudD.,Jaffa,17May1946,ISAM6628/6.

periodwerefeltbyordinaryPalestinians.Butmorethanthis,focussing onthesestoriesbringsintoviewarichseamofencounters,negotiations, andcontestationsstretchingacrosscolonialstateandsociety,ataregister overlookedbythepoliticalhistoriesthatdominatethescholarship. Second,thebookmakesthecaseforshiftingthecentreofgravitywithin historiesofpsychiatry – particularlycolonialpsychiatry – awayfrom institutionsorexpertsandtowardsafullerapprehensionofthemyriad spaces,actors,andissueswhichmentalillnessentangled.Tracingthe variedencounterswhichmentalillnessengenderedrequiresarethinking ofthearchiveofthehistoryofpsychiatry,too.Third,bylocating Palestine firmlyinrelationtowiderregional,imperial,andglobalcontexts, MandatoryMadness challengesthemethodologicalnationalism,the stubbornlynationalframingofanalysis,whichstillcharacterisesmuch scholarshiponbothPalestineandcolonialpsychiatry.Butitalsousesthe historyofpsychiatryinPalestine,includingitsspecificitiesandincommensurabilities,toengagecriticallyindebatesaroundmobility,translation,andglobalisationacrossthesedistinct fieldsandtounderscorethat blockages,andnotjustconnections,structuredPalestine’srelationships withwiderworlds.

Zmurud’sstorygivesasenseofwhatisgainedbyembracingthismore expansiveapproachtothehistoryofmandatePalestineandpsychiatry. Herpetitionsopenupourunderstandingofwherethehistoryofpsychiatryunfoldsandwhoitsprincipalcharactersare,andofferapowerful exampleofthesustained,consequentialnegotiationsPalestiniansundertookwiththecolonialstatearoundmentalillness;herstoryalsoprovides anobliqueavenueofapproachtounderstandingtheencounterbetween Palestineanddevelopmentsinpsychiatricpracticeglobally,byshowing howtheintroductionintothemandate’smentalinstitutionsofnew techniqueslikeelectro-convulsivetreatmentwasunderstoodandexperiencedbyfamilieslikeZmurud’s.Tostartwiththis firstpointabout spacesandactors,Zmurud’shusbandNassifwasnot,afterall,con fined forlongperiodsoftimebehindthewallsofamentalhospitalbutspent mostofhistimeathome,evenonceadmittedforoutpatienttreatment. Nassif’scondition,moreover,wasfarfromaprivatematter,concerning patientandpsychiatristalone;inonesenseintenselypersonal,itwasat thesametimehighlysocial,involvinghisfamilyaswellasarangeof officialsandotheractors.Centralthoughpsychiatryandmentalillness weretoZmurudandNassif’sstory,theirsisonethatmighteasilyslip fromviewifwekeepoursighttrainedtoocloselyonasinglepsychiatric institution,ortheresearchandpracticeofaparticularpsychiatristor school.Institutionalandintellectualhistoriesofcolonialpsychiatryhave beenimportantinrevealingtheoftenunevenintegrationofpsychiatric

expertiseandpracticewithinthewiderpanoplyofcolonialrule.4 But steppingoutsidetheinstitutionandde-centringtheexpertsmakespossiblearichsocialhistoryofhowcolonialsubjectsnavigatedmental illness,andhowthecolonialstate,inturn,responded.

Zmurud’sstoryalsodemonstrateshowmentalillnessprisedopena crucialifunstablespaceforPalestinianstonegotiateinmeaningfulways withthecolonialstate.Herhusband ’sillnessprofoundlydisruptedher family’slife,butshewasneitherthepassivevictimofcircumstances beyondhercontrol,nordidshemeeklydefertothediagnosesand prescriptionsofmedicalexperts.Whenmentalillnessmadeitsshocking appearance,Zmurudtookaction.Acrossthemandateperiod,mental illnesswasunderstoodbothasanissueaffectinganindividual ’shealth andasapotential,ifnotactual,threattothesafetyoffamilies,neighbours,andwidercommunities.Zmurudmadeuseofthis,andsoughtout anygovernmentagenciesshebelievedmightholdthepowertohelpher andherchildren,turningnotjusttodoctorsandhealthauthoritiesbutto thepoliceaswell.Rebuffedbyonesetofofficials,shetriedanother,and ratherthanacceptwhatexpertsdetermined,sheputforwardherown accountofherhusband’sconditionandproposalforhistreatment. Zmurudmobilisedhercommunity,too,addingtheirvoicestoherown tostrengthenhercallsforhelp.Her firstpetitiontotheHigh CommissionerwasattestedbyrepresentativesfromJaffa’sOrthodox Christiancommunity,whourgedthegovernmenttostepinandhelp withthedif ficultmatterof ‘hermadhusband’ 5 Hernegotiationswith doctorsandofficialstookplaceonamarkedlyunevenplaying field,and hergraspofthetreatmentwhichherhusbandwasreceivingseems partial,butherpersistenceyieldedatleastsomeconcessionsfromthe mandategovernment.Thiswasnomeanfeat.Inthewakeofwarand withthefutureofPalestinehanginginthebalance,itwouldnothave beendifficulttooverlookthestoryofashoe-makerwhohad ‘losthis

4 Foranoverviewofthehistoriography,seeRichardKeller, ‘MadnessandColonization: PsychiatryintheBritishandFrenchEmpires,1800–1962’ , JournalofSocialHistory 35,2 (2001),pp.295–326;andMeganVaughan, ‘Introduction’,inS.Mahoneand M.Vaughan,eds., PsychiatryandEmpire (Basingstoke:PalgraveMacmillan,2007), pp.1–16.Keypointsofreferenceinthisnowsubstantialbodyofscholarshipinclude: MeganVaughan, CuringTheirIlls:ColonialPowerandAfricanIllness (PaloAlto,CA: StanfordUniversityPress,1991);JockMcCulloch, ColonialPsychiatryand ‘theAfrican Mind’ (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1995);JonathanSadowsky, Imperial Bedlam:InstitutionsofMadnessinColonialSouthwestNigeria (Berkeley:Universityof CaliforniaPress,1999);RichardKeller, ColonialMadness:PsychiatryinFrenchNorth Africa (Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress,2007);and,albeitfocussedonpsychology ratherthanpsychiatry,ErikLinstrum, RulingMinds:PsychologyintheBritishEmpire (Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress,2016).

5 ZmurudD.,Jaffa,toHighCommissioner,1December1945,ISAM6628/6.

6Introduction

mind’ andbeatandthreatenedhiswifeandchildrenathome.Zmurud workedhardtomakesurethiscouldnotbeignored,couldnotbe overlooked,eitherbyhercommunityorbythecolonialgovernment.

Strikingthoughherstorymaybe,Zmurudwasnotaloneinbeing movedbymentalillnesstoenterintosuchcriticalnegotiationsacross stateandsociety.OvernearlythreedecadesofBritishrule,mentalillness engenderedandsustainedcomplex,consequentialinteractionswithin Palestine.StoriesoftheseencountersoftenreachusintheirmostcompellingformthroughpetitionslikeZmurud’s,andwithgoodreason:for alltherawemotionofthehumantragediestheyconvey,thesewere highlycraftedpiecesofwriting,carefullycalibratedtomovethestateto action.Butencounterswithmentalillnessarewoventhroughadizzying arrayofarchivalmaterial:sometimessensationalised,asinnewspaper reportageofcriminalinsanitytrials;atothertimes,buriedbeneaththe deadeningproseandstatisticsofthedepartmentofhealth’sannual reports.Thesearchivaltracesrevealthatencountersaroundmental illnessplayedoutacrossarangeofspacesandinvolvedawidecastof actors;theytookhugelyvariedforms.Some,asinthecaseofZmurud andherhusband,wereunspectacular,unequal,oftenunrewardingnegotiationsaboutthecareofthementallyill,initiatedandkeptgoingby familieswho,intheirdesperation,demandedthatthecolonialgovernmentreachintotheirhomesandtakeoverresponsibilityfortheirrelatives.IfthesenegotiationsofferaninsightintowhatClaireEdingtonhas calledthecolonialmicropoliticsofpsychiatriccare,6 andtelegraphwider contestationsoverthenatureofmentalillnessandefficacyofparticular therapeuticresponses,notallencountersaroundmentalillnessplayed outatsuchaneverydayregister.Othersunfoldedmorepublicly:inthe mandate’scourts,forinstance,wherejudges,lawyers,andwitnesses –expertandlay – debatedthementalresponsibilityandlegalculpabilityof defendantsinfullviewofthepressandpublic,andwherewhatwasat stakewasnotsimplythefateoftheaccusedindividualbuttherelationshipbetweenthelawandotherformsofpsychiatricandsocial knowledge.

Atadifferentlevelagain,theBritishauthoritiesfoundthemselves grapplingwiththespecificitiesofmentalillnessandpsychiatryin Palestine.Someofthedynamicsofthisencounter findparallelsacross thecolonisedworld,ascolonialstatesandtheirmedicalexpertsstruggled withthequestionofhowculturaldifferencemightaffecttheexpression andtreatmentofmentalillness.InPalestine,unusually,themost

6 ClaireEdington, BeyondtheAsylum:MentalIllnessinFrenchColonialVietnam (Ithaca,NY: CornellUniversityPress,2019),pp.6–7.

systematicattempttocometotermswiththiswasnotthroughany specialistresearchbutratherthroughtheenumerationofthe ‘insane’ populationinthe1931census.OtherdynamicswereuniquetoPalestine, mostobviouslytheimmigrationofhundredsofthousandsofEuropean Jewsacrossthisperiodandtheconcomitantdevelopmentofvoluntary provisionforthementallyill,provisionwhichoftenoutstrippedthe government’sown.Anotherpeculiarity,nolessimportant,wasasetof institutions,understandings,andlawsinheritedfromPalestine’sformer rulers,theOttomans,aninheritancetheBritishmoreoftenretainedand adaptedthanuprootedandreplaced.Agrowingbodyofscholarship highlightsthecontinuitieswhichsuturetogetherthehistoriesof OttomanandBritishPalestine.7 Extendingthisintotherealmofpsychiatricencountersfurnishesuswithnotonlyafullerappreciationof Ottomanlegacies,butalsoadistinctiveangleofapproachtoglobal historiesofscienceandmedicine,whereacommitmenttotranscending nationalorevenimperialboundarieshasnotalwaysentailedreflection, asAnnaTsingputsit,on ‘strugglesovertheterrainofcirculationandthe privilegingofcertainkindsofpeopleasplayers’ . 8 Ratherthanlocate globalconnectivityinnetworksofEuropeanexpertsalone,9 fromthe vantagepointofmandatePalestineinter-imperialexchangeentangleda non-EuropeanempireanditsEuropeansuccessor,andregionalconnectionsestablishedinthelateOttomanperiodweresustainedasmuchby patientsandtheirfamiliestravellingfortreatmentasbyArabmedical doctorsandnursesseekingtrainingandprofessionaldevelopment. EncountersaroundmentalillnessinmandatePalestinerippledupand downthesemultipleregistersofexperience,atestimonytoboththe polyvalencyofmentalillnessitselfasatermalwaysopentonegotiation

7 RobertoMazza, Jerusalem:FromtheOttomanstotheBritish (London:I.B.Tauris,2009); SalimTamari, ‘CityofRiffraff:Crowds,PublicSpace,andNewUrbanSensibilitiesin War-TimeJerusalem,1917–1921’,inK.A.AliandM.Rieker,eds., ComparingCities: TheMiddleEastandSouthAsia (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2010),pp.302–11; AbigailJacobson, FromEmpiretoEmpire:JerusalembetweenOttomanandBritishRule (Syracuse,NY:SyracuseUniversityPress,2011);JacobNorris, LandofProgress: PalestineintheAgeofColonialDevelopment,1905–1948 (Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press,2013).

8 AnnaTsing, ‘TheGlobalSituation’,inJonathanXavierIndaandRenatoRosaldo,eds., TheAnthropologyofGlobalization:AReader (Oxford:Blackwell,2002),p.463.Forthese critiques,seeSarahHodges, ‘TheGlobalMenace’ , SocialHistoryofMedicine 25,3 (2011),pp.719–28;andWarwickAnderson, ‘MakingGlobalHealthHistory:The PostcolonialWorldlinessofBiomedicine’ , SocialHistoryofMedicine 27,2 (2014),pp.372–84.

9 Thereareimportantexceptions,includingAbenaDoveOsseo-Asare, BitterRoots:The SearchforHealingPlantsinAfrica (Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress,2014);and EliseBurton, GeneticCrossroads:TheMiddleEastandtheScienceofHumanHeredity (Stanford,CA:StanfordUniversityPress,2021).

andcontestation,anditsproductiveversatilityasalensofanalysiswhich cancarryusacrossthethresholdsofsocial,cultural,orpoliticalhistory. TrackingpsychiatricencountersthroughtheselayersprovidesastrikinglydifferentperspectiveonthiscrucialperiodinPalestine’shistory. Itde-centresandre-contextualisesthelandpurchases,politicalmanoeuvrings,andinsurgenciesandcounter-insurgenciesthathaveserved inmoreteleologicalpoliticalhistoriesasmilestonesontheroadtothe endofBritishrule,thepartitionofPalestineandestablishmentofthe StateofIsrael,andthedisplacementofhundredsofthousandsof Palestiniansinthe nakba. 10 Ifafocusonpsychiatricencountersopens upvitalspaceforsocialandculturalhistoryandmakesitpossibletotake themandateperiodonitsowntermsratherthanasmerelyapreludeto 1948,italsoreimaginesthesites,actors,andindeedsourcesofthe historyofpsychiatry.Finally,followingpatients,aswellaspsychiatric ideasandpractices,astheytravellednotjustwithinbutbeyondthe bordersofthemandaterevealsboththeconnectionsandthedisjunctures whichstructuredPalestine’spositionrelativetowiderregional,imperial, andglobalcontexts.StorieslikeZmurud’s,inotherwords,formarich tapestryofinteractionsaroundmentalillnesswithinwhichstateand societyareknittedtogetherinsometimesunexpectedways,layersof historyandregistersofexperienceoftenheldapartareinsteadcrosshatchedintoconnection,andthethreadsofcertainstoriesstretchout towardsLebanon,Egypt,andIndia – orhangloose,trailingoffinto unknown,uncertainoutcomes.

Re-EntanglingtheHistoriesofMandatePalestine

Whilethereisnowagrowingbodyofscholarshiponthehistoryof psychiatryandthesciencesofthemindintheMiddleEast, 11 its

10 Forausefulrecentreviewofthehistoriographyofthemandate:LaurenBanko, ‘HistoriographyandApproachestotheBritishMandateinPalestine:NewQuestions andFrameworks’ , ContemporaryLevant 4,1(2019),pp.1–7.Thereisagrowinglistof importantworkswhichbreakwiththisfocus,including:SalimTamari, Mountainagainst theSea:EssaysonPalestinianSocietyandCulture (Berkeley:UniversityofCaliforniaPress, 2008);ElaGreenberg, PreparingtheMothersofTomorrow:EducationandIslaminMandate Palestine (Austin:UniversityofTexasPress,2010);Norris, LandofProgress;Andrea Stanton, ‘ThisIsJerusalemCalling’:StateRadioinMandatePalestine (Austin:University ofTexasPress,2013);ShereneSeikaly, MenofCapital:ScarcityandEconomyinMandate Palestine (Stanford,CA:StanfordUniversityPress,2015);andFredrikMeiton, Electrical Palestine:CapitalandTechnologyfromEmpiretoNation (Oakland:UniversityofCalifornia Press,2019).

11 Foranincompletelist,seeEugeneRogan, ‘MadnessandMarginality:TheAdventofthe PsychiatricAsyluminEgyptandLebanon’,inE.Rogan,ed., OutsideIn:Marginalityin theModernMiddleEast (London:I.B.Tauris,2002),pp.104–25;FatihArtvinli, ‘“Pinel

geographiccoveragehasbeenuneven.Todate,totheextentthat scholarshavealightedonthehistoryofmentalillnessinmandate Palestineatall,theyhavelargelyapproacheditasthestoryofthestruggle ofagroupofEuropeanJewishpsychiatriststoestablishtheirownprivate clinics,professionalorganisations,andultimatelythefoundationsofthe futureIsraelimentalhealthserviceafter1948.12 Withinthisscholarship, thehistoryofthemandate’sengagementswithmentalillnessisgiven littleattention,exceptinsofarasthecolonialgovernment’sprovisionis representedasakindoffoil,asformingaparallelifinferiorsystemtothat beingevolvedbyandfortheYishuv,Palestine’sJewishcommunity.13 AndthehistoryofPalestinianencounterswithmentalillnessandpsychiatryisaffordedevenlessweight.Inpart,thisisaresultoftheprivileging ofparticularkindsofsourcesasconstitutingthearchiveforwritinga historyofpsychiatryinPalestine,aboveallthepublications – whether researcharticlesinmedicaljournals,conferenceproceedings,orreports byprofessionalsocieties – ofpsychiatricexperts.Inpart,italsofollows fromtheadoptionofateleologicalframingthatworksbackwardsfrom theestablishmentoftheStateofIsraelandanIsraelimentalhealth service,andthusapproachesthehistoryofpsychiatryinthemandate periodnotonitsowntermsbutratherassubsumedwithinthisbigger nationalstory.

ofIstanbul”:DrLuigiMongeri(1815–82)andtheBirthofModernPsychiatryinthe OttomanEmpire’ , HistoryofPsychiatry 29,4(2018),pp.424–5;JoelleAbi-Rached, ʿAsfūriyyeh:AHistoryofMadness,Modernity,andWarintheMiddleEast (Cambridge, MA:MITPress,2020);BeverlyA.Tsacoyianis, DisturbingSpirits:MentalHealth, Trauma,andTreatmentinModernSyriaandLebanon (NotreDame:NotreDamePress, 2021);LamiaMoghnieh, ‘TheBrokenPromiseofInstitutionalPsychiatry:Sexuality, WomenandMentalIllnessin1950sLebanon’ , Culture,Medicine,andPsychiatry 47,1 (2023),pp.82–98.Thehistoryofpsychoanalysishasreceivedmuchattentioninitsown right:CyrusSchayegh, WhoIsKnowledgeableIsStrong:Science,Class,andtheFormationof ModernIranianSociety,1900–1950 (Oakland:UniversityofCaliforniaPress,2009); OmniaElShakry, TheArabicFreud:PsychoanalysisandIslaminModernEgypt (Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress,2017);KutluğhanSoyubol, ‘Turkey Psychoanalyzed,PsychoanalysisTurkified:TheCaseof İzzettin Şadan’ , Comparative StudiesofSouthAsia,AfricaandtheMiddleEast 38,1(2018),pp.57–72.

12 TheworkofRakefetZalashikisexemplaryinthisrespect.See,inparticular,Rakefet Zalashik, AdNefesh:Immigrants,Olim,Refugees,andthePsychiatricEstablishmentinIsrael (TelAviv:Ha-Kibbutzha-Me’uhad,2008)[inHebrew];RakefetZalashik, DasUnselige Erbe:DieGeschichtederPsychiatrieinPalästinaundIsrael (FrankfurtamMain:Campus Verlag,2012)[inGerman];RakefetZalashikandNadavDavidovitch, ‘Professional IdentityacrosstheBorders:RefugeePsychiatristsinPalestine,1933–1945’ , Social HistoryofMedicine 22,3(2009),pp.569–87.

13 MarcellaSimoni, ‘ADangerousLegacy:WelfareinBritishPalestine,1930–1939’ , Jewish History 13,2(1999),pp.81–109;MarcellaSimoni, ‘AttheRootsofDivision:ANew PerspectiveonArabsandJews,1930–39’ , MiddleEasternStudies 36,3(2000),pp.52–92.

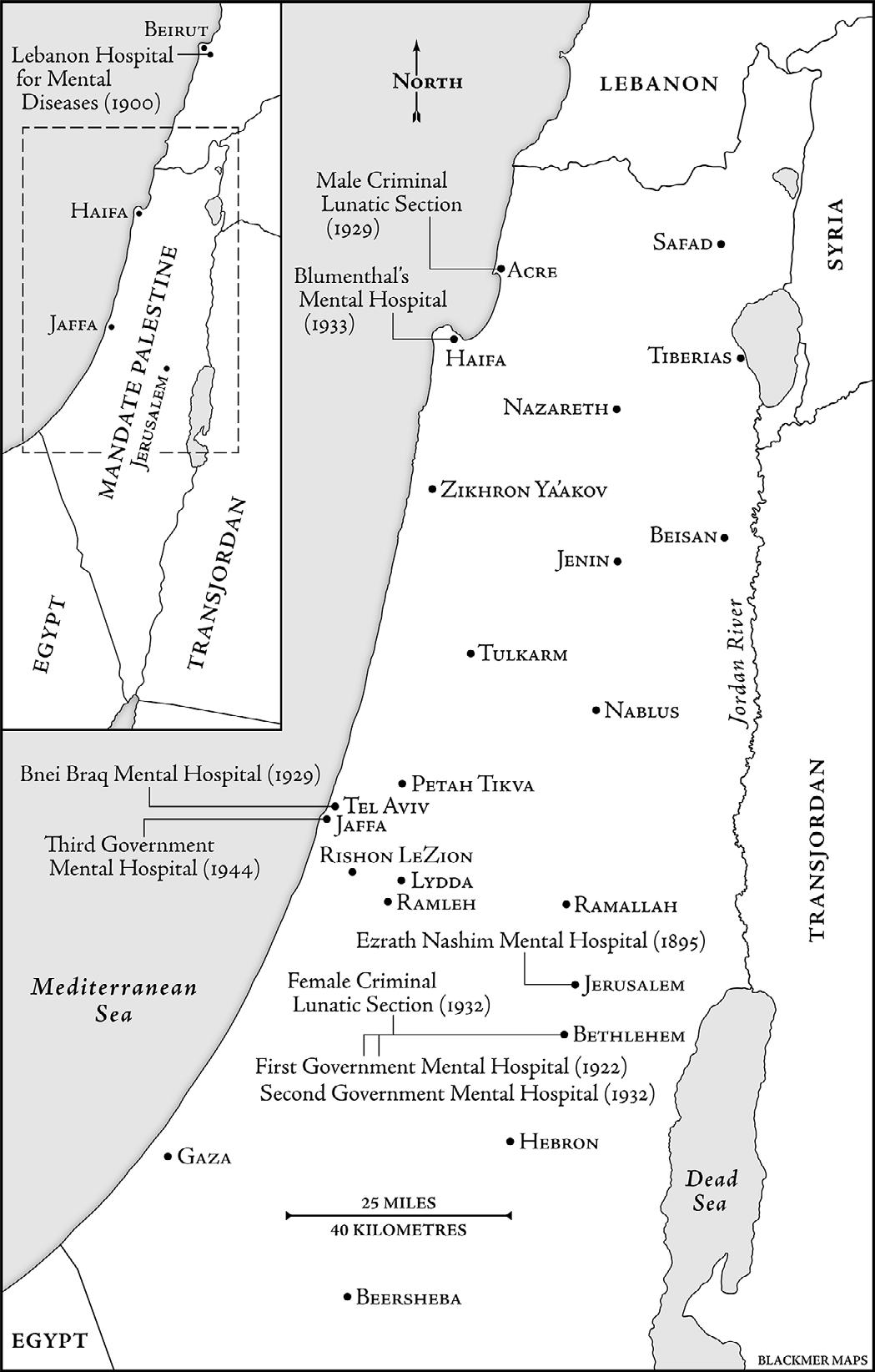

MandatoryMadness doesnotseektounderplaythesigni ficanceof privateJewishprovision:itisanundeniablyimportantdimensionofthis historyandindeeddistinguishesPalestinefromothercolonialcontexts. Formostofthemandateperiod,privateJewishprovisionnotmerely rivalledbutoutstrippedgovernmentprovisionbothintermsofitsbedstrengthandthekindsoftreatmentavailable.AcrossPalestine’smajor citieswithsigni ficantJewishpopulations – citieslikeJerusalem,Jaffa,Tel Aviv,andHaifa – privatepsychiatricinstitutionsproliferated,especially after1933,whentheNaziscametopowerinGermanyandprecipitated the flightoflargenumbersofEuropeanJewishpsychiatriststo,among otherdestinations,Palestine.PrivateJewishprovisionpredatedthemandate’sowneffortsinthis field,too:theearliestinstitutiontotendtothe ‘insane’,theEzrathNashimhomeinJerusalem,openeditsdoorsforthe firsttimeinthe1890s,whentheOttomansstillruled.Ignoringthis historytofocusexclusivelyonthemandate’sprovision,oron Palestinianengagementswithmentalillness,wouldnotonlybeimpossible,butproduceanequallypartialunderstandingoftheperiod.

Byadoptingamorecapaciousapproachtowhatthehistoryofpsychiatryentails,focussedlessonpsychiatricinstitutionsandexpertsthan interactions, MandatoryMadness bringsthemandategovernment,the Yishuv,andPalestinianstogetherintoasingleanalyticframeinstead. Thelasttwotermsappear – likethebetter-knownpairingofAraband Jew – todenotetwomutuallyexclusivegroupings.Yetwhiletheiruse maybeunavoidable,notleastascategoriesadoptedbyactorsatthetime, itisimportanttoclarifythatthesearenotneutralorunproblematic descriptions.ThepositionofPalestine’sSephardiorMizrachi(‘eastern ’) Jewsbringsthissharplyintofocus.FormerOttomansubjects,theyspoke ArabicwiththeirMuslimandChristianneighboursandweredeeply dividedonthesubjectofZionism,withsomejoininganti-Zionistprotests intheearlyyearsofBritishrule.Fortheirpart,EuropeanJewishémigrés werealsoambivalentabouttheir ‘backwards’ , ‘native’ co-religionists.Yet overtime,bothasaresultoftheevolutionofasetofZionistparastatal institutionsthatclaimed,withthemandate’sblessing,responsibilityfor allofPalestine’sJewishpopulation,andasaconsequenceofthefailureof ArabnationaliststomaintainacleardistinctionbetweenZionismand Jewsmoregenerally,thesecategoriesdidcometoformanoppositionary binary.AsEllaShohatputsit, ‘[f]orthe firsttimeinSephardihistory, ArabnessandJewishnesswereposedasantonyms’ . 14 Ratherthan

14 EllaShohat, ‘SephardiminIsrael:ZionismfromtheStandpointofItsJewishVictims’ , SocialText 19/20(1988),p.11.SeealsoMichelleU.Campos, ‘Between “Beloved Ottomania” and “TheLandofIsrael”:TheStruggleoverOttomanismandZionism

straightforwarddescriptions,thetermsArabandJew,Yishuvand Palestinians,shouldbetreatedasdenotingprotean,contested,andat timesoverlappinggroupings,thoughinthisbookIhavetried,either throughcontextorthroughadditionalquali fiers,toclarifymyownusage asfaraspossible,and,morethanthis,tohighlighthowencounters aroundmentalillnessattimesworkedtoreinforceandatothersserved tounderminethehardeningboundariesbetweenthesecategories.

Attendingtohowmandateofficials,EuropeanJewishémigrés,and PalestinianArabs – Muslim,Christian,andJewish – engagedwiththe questionofmentalillnesschallengesexistingaccountsontwokeypoints. Inthe firstplace,asharedlensofanalysisrevealsthatgovernmentand privateprovisionforthementallyill,ratherthanformingseparateand parallelsystems,wereinextricablyentangled;thehistoryofonesimply cannotbeunderstoodinisolationfromtheother.EuropeanJewish psychiatrists,includingthosewhorantheirownprivateclinics,appeared beforethemandate’scourts,testifyingtothementalcapacityofdefendants;theywereappointedtoinspectandreportoncriminallunatic wards;theyofferedaninterpretationofthereturnsofthe ‘insane’ populationinthe1931census.Inturn,themandategovernment – while attemptingingeneraltoavoidassumingresponsibilityforprivateinstitutions – steppedinwhentheseinstitutionsstumbledandtheirpatient populationsthreatenedtospilloutontothestreets,eitherwithanofferof subsidiesandademandforreform,orbyexpandingtheirownprovision. Thisdynamic,indeed,canbeseenasdrivingthehistoryofthemandategovernment’sprovision.In1922,whenthe firstgovernmentmental hospitalopenedoutsideBethlehem,itdidsoinparttorelievethebeleagueredEzrathNashiminstitution;in1932,asecondgovernmentmental hospitalwasestablished,againoutsideBethlehem,formuchthesame reason;andin1944,athirdand finalsuchgovernmenthospital,thistime nearJaffa,openedandimmediatelytookinallthepatientsatanearby privatementalinstitutionteeteringonthebrinkofcollapse.Knitting thesesystemstogetheratanotherlevelstill,patientscontinuouslycirculatedbetweenprivateandgovernmenthospitals,especiallyasthecostsof privatetreatmentmountedandfamiliesturnedtogovernmentinstitutionsfor financialrespite.Fromthevantagepointofferedbypsychiatric provision,colonialandZioniststate-buildingprojectsinPalestineappear

amongPalestine’sSephardiJews,1908–13’ , InternationalJournalofMiddleEastStudies 37(2005),pp.461–83;DafnaHirsch, ‘“WeAreHeretoBringtheWest,NotOnlyto Ourselves”:ZionistOccidentalismandtheDiscourseofHygieneinMandatePalestine’ , InternationalJournalofMiddleEastStudies 41,4(2009),pp.577–94;SalimTamari, ‘Ishaqal-ShamiandthePredicamentoftheArabJewinPalestine’ , JerusalemQuarterly 21(2004),pp.10–26.

asenmeshedandoftenmutuallyreinforcing,ratherthanwhollydistinct, enterprises 15

Asecondwayinwhich MandatoryMadness departsfromexisting framingsofthehistoryofpsychiatryinmandatePalestineisbymoving beyondanexclusivefocusonthemandateandtheYishuv,aboveallby writingPalestiniansbackintothisstory.LikeZmurud,whomobilised bothhercommunityandthegovernmentwhenmentalillnessintruded onherfamily’slife,Palestinians – Muslim,Christian,andJewish –participatedactivelyinthemakingofthishistoryinmyriadways.They actedaspetitionersseekingsuccourfortheirrelatives,andasplaintiffs, defendants,andwitnessesincriminalinsanitytrials.Theywerealsothe doctors,nurses,andhospitalattendantswhoselabourallowedgovernmentmentalinstitutionstofunctionandwhoworked – frequentlyinthe faceofindifferenceonthepartoftheiremployer,themandate’s departmentofhealth – tocultivatepsychiatricexpertise.Butwriting Palestiniansbackintothishistoryalsodramaticallyrefiguresitsparameters,byprovincialisingpsychiatryanditsmedicalisedofferingsofcure orconfinement.ThetherapeutictrajectoriesPalestinianfamiliescharted fortheirrelativesexceededboththepsychiatrichospitalandthecolonial archive,astheypursued – oftensimultaneously – medicalandnonmedicaloptionsalike,inwayswhichtroubleanysharpdistinction betweenthemodernandthepremodernorthesecularandthesacred. Andevenwithinthewallsofthementalhospital,Palestinianpatients mightcarrywiththemcontrapuntalunderstandingsoftheirexperiences, transformingthissiteintoaspaceanimated,fractured,evenhauntedby dissonantregisters:thepsychiatric,theotherworldly,thesomatic, thepolitical.

AswellasrecoveringtheagencyofPalestinians,zoomingoutfromthe mandateandtheYishuvrevealstheimportanceofbothregionalconnectionsandOttomanlegaciestothishistory.Palestineisoftenrepresented asexceptional,notleastastheonlycaseinwhichtheLeagueofNations’ PermanentMandatesCommissionendorsedsettlercolonialismby incorporatingtheBalfourDeclaration,withitscommitmentofBritish supportfor ‘anationalhomefortheJewishpeople ’,intothemandate text 16 WithoutelidingallofPalestine ’sstubbornspeci ficities,widening thecameralenscanbringintoviewhowthehistoryofmandatory

15 Forsimilardynamicsinotherareas,seeNorris, LandofProgress,andMeiton, ElectricalPalestine.

16 Seebelow.SusanPedersen, ‘SettlerColonialismattheBaroftheLeagueofNations’,in CarolineElkinsandSusanPedersen,eds., SettlerColonialismintheTwentiethCentury: Projects,Practices,Legacies (London:Routledge,2005),pp.124–9.

psychiatrywasembeddedinthelargerregionalcontext.Palestinians travelledfortreatmentattheLebanonHospitalforMentalDiseasesat Beirutbeforeandafterthepost-warpartitionoftheregion,andthevast majorityofaspiringdoctorsinmandatePalestinehadlittlechoicebutto makesimilarjourneysnorthformedicaltrainingattheAmerican UniversityofBeirut,astheirlateOttomanpredecessorshaddone.And itwasnotonlyEuropeanJewishémigréswhopippedtheBritishtothe postbytransplantingpsychiatrytoPalestinebeforetheFirstWorldWar; knowledgeofthepsy-scienceswasalreadyindependentlycirculating acrossOttomanArabterritoriesthroughscienti ficjournalslike alMuqtataf fromthelastdecadesofthenineteenthcenturyonwards.17 Theirexpectationsprimedbyalongvisualandliterarytraditionof representingPalestineasatimeless,biblical ‘HolyLand’ , 18 theBritish mayhavearrivedimaginingthatinPalestine,aselsewhereinthecolonisedworld,theywoulddiscoverapopulationforwhompsychiatrywasa noveltyandmentalillness – commonlyunderstoodasanunfortunatebyproductofindustrialmodernity19 – ararity.Asitturnedout,however, manyoftheirnewlyacquiredsubjectswerelesspsychiatricallynaı ¨vethan theBritishhadfantasised,andcametodemandmorefromtheirnew rulersthanthemiserlysumsetasideforhealthinthemandate’s budgetsallowed.

Takentogether,recognitionoftheinterdependencyofgovernment andprivateprovision,ontheonehand,andofPalestinianpsychiatric agency,ontheother,warnsagainstassumingtoosharpabreakbetween thehistoriesofArabsandJewsinthisperiod.Farfromremainingwithin theclosedcircuitofgovernmentprovision,atleastsomePalestinians soughttreatmentforrelativesinprivateJewishinstitutions,aswellas beyondthebordersofthemandate.AndlargenumbersofEuropean Jewishpatientswereadmittedtogovernmentmentalhospitals,tobe treatedbyArabdoctorsandnursesalongsideArabpatients.Bytheend ofthemandateperiod,certainly,thehistoryofpsychiatryhadbeen partitioned,alongwithhistoricPalestine,aspsychiatricpatientpopulationswerereordereddownethno-religiouslinesandgovernmentmental institutionswereparcelledoutbetweenIsraelandJordan.Butacrossthe precedingdecades,entanglementratherthanseparationcharacterised

17 Abi-Rached, ʿAsfuriyyeh,pp.39–46.

18 ForthehistoryofEnglishrepresentationsofPalestineasa ‘HolyLand’,seeEitanBarYosef, TheHolyLandinEnglishCulture,1799–1917:PalestineandtheQuestionof Orientalism (Oxford:ClarendonPress,2005).

19 Alinkassertedinternationallybythelatenineteenthandearlytwentiethcenturies:see forinstanceAndreaKillen, BerlinElectropolis:Shock,NervesandGermanModernity (Berkeley:UniversityofCaliforniaPress,2006).

thishistory,andevenafter1948,notallthesetieswereimmediatelyor fullyshredded.Inthe1990s,inanattempttobreakoutofapattern withinthehistoriographyofattendingexclusivelytoeithertheArabor Jewish ‘side’ ofthisstory,labourhistorianspioneereda ‘relational’ approachtotheperiod,whichemphasisedthemutuallyconstitutive natureofthesehistories,andputtheinteractionsbetweenthemfront andcentre. 20 Butitisnotonlyinthe fieldoflabourhistorythatsuchan approachispossible.ReconstructingandtrackingtheinteractionsgeneratedbymentalillnessuncoversanewrelationalhistoryofPalestine,in whichArabs,Jews,andindeedtheBritishmandateseldomnegotiated thequestionofmentalillnessinisolationfromoneanother.

AHistoryofPsychiatrywithoutCaseFiles

InEmileHabibi’ssatiricalclassic TheSecretLifeofSaeed:ThePessoptimist, thenarratorissent ‘strangeletters’ whichrelatethesurreallifeofthe eponymousanti-hero,aPalestinianrefugeewhoendsupactingasan Israeliinformantafter1948.Towardstheendofthenovel,thenarrator tracksdowntheauthoroftheseletters firsttoAcre,andthentothe mentalhospitalhousedinthesamebuildingthathadservedasanotoriousprisonduringthemandateperiod.Afterexpressingastonishmentto thehospital’sstaffthatashrinetothoseexecutedbytheBritishonthe sitecommemoratesonlymembersofaJewishparamilitaryorganisation, andnottheArabswhomtheyhangedaswell,theunnamednarrator attemptstodiscoverwhothemysteriousSaeedmightreallybe. Together,theysearchthehospital’srecords,tryingtodiscoverSaeedin amongallthepatientsadmittedsincethefoundingofthestate,butare unableto findanyonewiththatname.Theythenlookforsimilarnames, and ‘findonethatlookedsuspicious ’:Saadi.Butthatisallthehospital ’s recordsyield;theonlyadditionalinformationthenarratorisabletoglean fromthehospitalstaffabouthiselusivecorrespondentisthatawoman hadrecentlyvisitedthehospitalfromBeiruttoaskafterhim – andthathe haddiedtheyearearlier.21 Thearchivaltrailhasgonecold.

20 GershonShafir, Land,Labour,andtheOriginsoftheIsraeli-PalestinianConflict,1882–1914 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1989);ZacharyLockman, ‘RailwayWorkers andRelationalHistory:ArabsandJewsinBritish-RuledPalestine’ , ComparativeStudies inSocietyandHistory 35,3(1993),pp.601–27;ZacharyLockman, Comradesand Enemies:ArabandJewishWorkersinPalestine,1906–1948 (Berkeley:Universityof CaliforniaPress,1996);DeborahBernstein, ConstructingBoundaries:JewishandArab WorkersinMandatoryPalestine (Albany:SUNYPress,2000).

21 EmileHabibi, TheSecretLifeofSaeed:ThePessoptimist [1974],trans.SalmaJayyusiand TrevorLeGassick(London:ArabiaBooks,2010),pp.161–2.

Forhistorians,asforHabibi’snarrator,thesearchforpatientsamong therecordsofthemandateperiodcanbeafrustratingone.Zmurud’s storyisacaseinpoint.Althoughshehadbeenreassuredbythemandate governmentthatherhusbandNassifwouldbeadmittedassoonasabed inthementalhospitalatJaffabecameavailable,Ihavebeenunableto findanydocumentinthecolonialarchivewhichwouldallowusto ascertainwhen – orif – thisultimatelytookplace,letaloneacase file withwhichtocontinuethisstory.Inthisrespect,Nassif’scaseistypical. Withthenotableexceptionof filesrelatingtocriminallunatics,patient case filesdonotappeartohavesurvived.Theyarenottobefoundamong themanyotherrecordsofthemandate’sdepartmentofhealthheldbythe IsraelStateArchivestoday.NorareanyrecordsonsiteinBethlehemat whatwasatthetimethe firstgovernmentmentalhospital,andwhichhas continuedsince1948tooperateasapsychiatrichospitalunder first Jordanianruleand,after1967,Israelioccupation. 22

Alongsidethelimitedsurvivalofpatientcase filesinthearchive, historiansmustcontendwithadecidedlyunevenbodyofpublished material.WhileEuropeanJewishpsychiatristsandotherexpertspublishedresearchbasedontheirclinicalexperiencesinprivateinstitutions inPalestine,noparallelsetofpublicationsaboutmentalillnesswas producedinthisperiodbytheArabdoctorswhomadeupthemajority ofthestaffofthemandate’sdepartmentofhealth.Theselacunaeand imbalancesinthekindsofsourceswhichhavebeentheanchorsofmost institutionalandintellectualhistoriesofpsychiatryareinpartresponsible fortheexistingscholarship’sportrayalofthishistory,asoneinwhich EuropeanJewishpsychiatristsaretheprincipalactors,themandategovernmentabitplayer,andPalestiniansoff-stageentirely.Intheabsenceof theseconventionalsources,historiansappeartohaveconcludedthatthe historyofpsychiatryinmandatePalestineisitselfnon-existentandhave focussedtheirattentionontheYishuvinstead.Justashistoriansof decolonisationintheregionhaveinnovatedmethodologicallywhen facedwithinaccessibleorabsentarchives,23 sotoodoes Mandatory Madness contendthatembracingalessconventional,moreeclecticbody ofsources – evenfromwithinthecolonialarchive – canuncoveran expansive,ultimatelyricherhistoryofpsychiatryinmandatePalestine. Ratherthantreatthelimitedsurvivalofcase filesandtheuneven publicationofpsychiatricresearchsimplyasanobstacletorecovering

22 PrivatecorrespondencewithDrIssamBannoura,directoroftheBethlehempsychiatric hospital,21December2017.

23 OmniaElShakry, ‘HistorywithoutDocuments:TheVexedArchivesofDecolonization intheMiddleEast’ , AmericanHistoricalReview 120,3(2015),pp.920–34.

thishistory,orasevidenceofitsabsence,accountingforthisarchivalstateof affairscanalsobeitselfrevealing.Theasymmetryinresearchpublications, forinstance,isanimportantreminderthatbringingthemandate,theYishuv, andPalestiniansintothesameframeofanalysisshouldnotobscuretheir starkdifferences,orimplyanequivalency.The firstwasacolonialstate, sanctifiedininternationallawunderthecoverofadifferentnamebutableto marshaltroopsandresourcesfromacrosstheBritishempireinmomentsof need.Thesecondwasweldedacrossthisperiodintoastate-in-waiting, completewithitsownself-governinginstitutions,byahighlyorganised politicalnationalistmovementandwiththerecognitionandpracticalsupport ofthemandate.Meanwhilethethirdwasanindigenouspopulationwhohad beencolonisedinthewakeofprofoundwartimepoliticalandsocialdislocationandwhosepoliticalrightswerenever,inspiteoftheirtirelesseffortsto organise,affordedinternationalrecognition.Theseandotherdifferences cruciallyshapedtheconditionswithinwhichpsychiatricandmedicalexpertisewascultivatedandvalidated.Put simply,whileEuropeanJewishpsychiatristsandotherspecialistsworkingin privateinstitutionshadthefreedomto selectclinicallyinterestingpatients,trialnewmethodsoftreatment,and publishtheir findings,thedepartmentofhealth – themostimportantthough notthesoleemployerforPalestinianArabdoctorsacrosstheperiod –investedlittleindevelopingPalestinian psychiatricexpertise,insteadabetting conditionsofworkatgovernmentmentalinstitutionsthatrestrictedopportunitiesforresearchoranyotherkindofspecialistdevelopment.

Thelackofpsychiatricresearchpublishedbythoseemployedinthe mandate’sdepartmentofhealthmarksPalestineoutfromothercolonial contexts.WhileambitiousFrenchand,toalesserextent,Britishpsychiatristsoftenfoundinthecoloniesalaboratorythattheycoulduseto pushthelimitsofthe field,establishtheirreputations,andultimately returntothemetropolitanmedicalstagefetedaspioneers , 24 Palestine wasdifferent.Itsatincontrasttomedicalserviceselsewhereinthe Britishempire,wherewestern-traineddoctorsdrawnfromthecolonised populationonlygraduallyreplacedEuropeansintheinterwardecadesin India,orthepost–SecondWorldWardecadesacrossmuchofsubSaharanAfrica.25 Instead,fromthestartthemajorityoftheemployees

24 McCulloch, ColonialPsychiatry;Keller, ColonialMadness.Forcoloniesaslaboratoriesof modernitygenerally,see:PaulRabinow, FrenchModern:NormsandFormsoftheSocial Environment (Cambridge,MA:MITPress,1989);GwendolynWright, ThePoliticsof DesigninFrenchColonialUrbanism (Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress,1991).

25 WaltraudErnst, ‘TheIndianizationofColonialMedicine:TheCaseofPsychiatryin Early-Twentieth-CenturyBritishIndia’ , NTMZeitschriftfürGeschichtederWissenschaften, TechnikundMedizin 20(2012),pp.61–89;YolanaPringle, PsychiatryandDecolonisation inUganda (Basingstoke:PalgraveMacmillan,2018),pp.59–92.

ofthedepartmentofhealthwereformerOttomansubjectswhohad receivedmedicaltraininginBeirut,Istanbul,Damascus,andCairo26 –thoughacrossthisperiodthehighestranksinthedepartmentwere filled exclusivelybyEuropeans.Allocatedapaltry4percentofgovernment expendituremostyears,thehealthdepartmentprioritisedtacklinginfectiousdiseases – aboveallmalaria – overprovidinghospitalcare,27 and certainlyovernurturingpsychiatricexpertise.

Thisismadeclearestbythecareerofthedoctorwhowasinchargeof thegovernment’sonlymentalhospitalsformostoftheperiod,DrMikhail ShedidMalouf.Malouf – acentral,albeitelusive,characterinthisbook

startedoutworkingasanophthalmologist,beforebeinggivenresponsibilityforthe firstgovernmentmentalhospitalin1925.Ratherthanreceivingsupportfromthegovernmenttodevelophisexpertiseby,forinstance, takingspecialisttrainingabroad,heappearstohavehadtolearnonthe job.Whetherasaresultofalackofformalqualificationsorsimplytime,he neverdrewonhisextensiveclinicalexperiencetopublish,andso,besides ahandfulofreportsproducedforthegovernmentandtheoccasional interview,frustratinglylittleexistsbywayofhiswriting.Thissituation didnotchangeeveninthe1940s,whenPalestinianArabdoctorsworking inthedepartmentofhealth,voluntaryclinics,andmissionhospitalscame togethertoformthePalestineArabMedicalAssociationandlaunched theirownArabic-languagemedicaljournalin1945.Inspiteoftheir enthusiasticsupportforthecultivationofspecialistknowledge,psychiatry wasnotontheirradar.Itneverfeatured,forinstance,amongthearticles publishedbyPalestiniandoctorsintheassociation’sjournal,wherethe focus – asforthehealthdepartment – wasoneitherinfectiousdiseaseslike malariaorinfantandmaternalhealth.28

26 LiatKozmaandYoniFuras, ‘PalestinianDoctorsundertheBritishMandate:The FormationofaProfession’ , InternationalJournalofMiddleEastStudies 52(2020), pp.87–108.Inthisrespect,therewereparallelswithBritishmandateIraq,thoughthis formallyendedin1932.SeeOmarDewachi, UngovernableLife:MandatoryMedicineand StatecraftinIraq (Stanford,CA:StanfordUniversityPress,2017),pp.48–53.

27 SeeSandySufian, ‘ArabHealthCareduringtheBritishMandate,1920–1947’,in T.BarneaandR.Husseini,eds., SeparateandCooperate,CooperateandSeparate:The DisengagementofthePalestineHealthCareServicefromIsraelandItsEmergenceasan IndependentSystem (London:Praeger,2002),p.14.Miserlyhealthbudgetswerenot uniquetomandatePalestine,withcolonialstatesgenerallybudgetinglittleforhealthand husbandingthosescantresourcesforusein ‘colonialenclaves’ andincombating epidemicdisease.Fortwoclassicstudies,seeVaughan, CuringTheirIlls;andDavid Arnold, ColonizingtheBody:State,MedicineandEpidemicDiseaseinNineteenth-Century India (Berkeley:UniversityofCaliforniaPress,1993).

28 Inpart,theattentiontomalariawasalsoinordertorefuteZionistclaimsabouttheirown effortsinthisarea.SeeSandraSufian, HealingtheLandandtheNation:Malariaandthe ZionistProjectinPalestine,1920–1947 (Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress, 2007),pp.319–27.