POLITICSOFTHE NORTHKOREAN DIASPORA

SheenaChestnutGreitens UniversityofTexasatAustin

ShaftesburyRoad,CambridgeCB28EA,UnitedKingdom OneLibertyPlaza,20thFloor,NewYork,NY10006,USA 477WilliamstownRoad,PortMelbourne,VIC3207,Australia

314–321,3rdFloor,Plot3,SplendorForum,JasolaDistrictCentre, NewDelhi – 110025,India

103PenangRoad,#05–06/07,VisioncrestCommercial,Singapore238467

CambridgeUniversityPressispartofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment, adepartmentoftheUniversityofCambridge.

WesharetheUniversity’smissiontocontributetosocietythroughthepursuitof education,learningandresearchatthehighestinternationallevelsofexcellence.

www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle: www.cambridge.org/9781009454537

DOI: 10.1017/9781009197267

©SheenaChestnutGreitens2023

Thispublicationisincopyright.Subjecttostatutoryexceptionandtotheprovisions ofrelevantcollectivelicensingagreements,noreproductionofanypartmaytake placewithoutthewrittenpermissionofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment.

Firstpublished2023

AcataloguerecordforthispublicationisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN978-1-009-45453-7Hardback

ISBN978-1-009-19728-1Paperback

ISSN2632-7368(online)

ISSN2632-735X(print)

CambridgeUniversityPress&Assessmenthasnoresponsibilityforthepersistence oraccuracyofURLsforexternalorthird-partyinternetwebsitesreferredtointhis publicationanddoesnotguaranteethatanycontentonsuchwebsitesis,orwill remain,accurateorappropriate.

ElementsinPoliticsandSocietyinEastAsia

DOI:10.1017/9781009197267 Firstpublishedonline:December2023

SheenaChestnutGreitens UniversityofTexasatAustin

Authorforcorrespondence: SheenaChestnutGreitens, sheena.greitens @austin.utexas.edu

Abstract: PoliticsoftheNorthKoreanDiaspora examineshow authoritariansecurityconcernsshapeglobaldiasporapolitics. Empirically,ittracestherecentemergenceofaNorthKoreandiaspora – a globally-dispersedpopulationofNorthKoreanémigrés – andargues thatthenon-democraticnatureoftheDPRKhomelandregime fundamentallyshapesdiasporicpolitics.Pyongyangperceivesthe diasporaasathreattoregimesecurity,andattemptstodissuade emigration,de-legitimatediasporicvoices,anddeterordisruptdiasporic politicalactivity,includingthroughextraterritorialviolenceand transnationalrepression.This,inturn,shapestheNorthKorean diaspora’sperceptionsofcitizenshipandpatternsofdiasporicpolitical engagement:NorthKoreanémigréshaveinternalizedmanyhost countrynorms,particularlythecivilandparticipatorydimensions ofdemocraticcitizenship,andémigréshaveplayedimportantroles inbothhost-countryandglobalpolitics.ThisElementprovidesnew empiricalevidenceontheNorthKoreandiaspora;demonstratesthat regimetypeisanimportant,understudiedfactorshapingtransnational anddiasporicpolitics;andcontributestoourunderstanding ofcomparativeauthoritarianism’sglobalimpact.

Keywords: NorthKorea,authoritarianism,diaspora,politicalbehavior, humanrights

©SheenaChestnutGreitens2023

ISBNs:9781009454537(HB),9781009197281(PB),9781009197267(OC)

ISSNs:2632-7368(online),2632-735X(print)

ThisElementexaminestheemergenceandsignificanceoftheNorthKorean diaspora.Overthepastthirtyyears,agrowingnumberofindividualshaveleft theDemocraticPeople’sRepublicofKorea(DPRK)andresettledinthird countries,forminganew,globallydispersedpopulation.NorthKoreanemigrationhasbeenconcentratedinSouthKorea,butnotlimitedtoit:whilealmostall DPRKémigrésinitiallysettledinSouthKorea,asignificantnumberhavesince soughtasylumandresettlementbeyondtheKoreanpeninsula.

Thisspecificformofmigration,andthediasporicpoliticsthatithasengendered, hasreceivedlittlesystematicattention.Thereisrobustscholarshiponearlier wavesofmigrationthatformedtheKoreandiaspora,includingthediaspora’s roleinKoreanstateformationandcontemporarytransnationalpoliticsinand aroundthepeninsula.ThecontemporarywaveofmigrationfromNorthKorea, however,isempiricallydistinctfrompreviouswaves,eitherthosethatpreceded themodernKoreanstatesonbothhalvesofthepeninsula,ortheout-migrationof Koreansfromthepeninsula’ssouthernhalfsince1948.NorthKoreanémigrésthus formthemostrecentlayerofabroaderKoreandiaspora – embeddedwithinglobal Koreancommunities,butalsoretainingdistinctiveidentitiesandpatternsof politicalbehavior.Asyet,however,thereisrelativelylittlescholarshiponNorth Koreanémigrés – theirdestinations,experiences,conceptionsofidentity,and politicalengagement,eitherinhostcountriesorvis-à-vistheirhomeland.This Elementsystematicallyunpacksandaddressesthosequestions.

Asitdoesso,theElementalsoengageswiththequestionofhowhomeland regimetypeshapesdiasporicpolitics – agrowingareaofresearchattheintersectionofcomparativepoliticsandinternationalrelations.NorthKoreafallsin asubsetofcaseswhereinthediasporaemergesfromandengageswith ahomelandunderauthoritarianrule.Recentscholarshiphighlightsthatwhen authoritariangovernmentssuppressoppositionandcontentionathome,citizens canturntomigrationandresettlementabroadtoevade,organizearound,and contestthepowerandcontrolofhomelandregimes.Whenthathappens,diasporas becomeimportantsitesofanti-regimeactivity;authoritarianregimesinturn strategicallymanagemigrationanddiasporicpoliciestomitigaterisksandcontrol populationsresidingabroad(Ragazzi2009; BettsandJones2016; Glasius2018; Tsourapas2018; Adamson2020; MillerandPeters2020).

Theorigins,politicaldynamics,andimpactofthese “defectordiaspora” groups orsubgroups,however,remainincompletelyunderstood.Howdowavesof migrants fleeingauthoritarianruledifferfromandlayerintopreexistingethnic diasporapopulations,andwhatfactorsshapetheformthattheseauthoritarian diasporastake?Whenandhowdothesesubgroupsengageinpoliticalactivity,

eitherinthehostcountrieswheretheyresettleortransnationallyvis-à-vistheir authoritarianhomelands?Howdohomelandauthoritarianregimesviewthese diasporapopulations,andseektomanagethemtoensurethattheydon’tbecome athreat?Asoneofthemostclosednondemocraticregimesinthecontemporary world,NorthKoreaprovidesanimportantcasestudybywhichtoexaminethese largercomparativequestions.

PoliticsoftheNorthKoreanDiaspora explainstheoriginsandshapeofthe NorthKoreandiaspora,examineshowNorthKoreanémigrés’ participationin democratichostcountriesintersectswiththeiractivismvis-à-vistheDPRK’s authoritarianregime,anddiscusseshowthisapproachtodiasporicpoliticssheds lightoncomparativedevelopmentsinauthoritariandiasporasworldwide.The divisionoftheKoreanpeninsulaandsubsequentcontestationovermigrantcitizenshipandasylumeligibilityhavegeneratedaT-shapeddiaspora,deeplyconcentratedinSouthKoreabutwithathin,globaldistributionofdiasporamembers anchoredinothercountries.ManyoftheseindividualsleftNorthKoreafor economicaswellaspoliticalreasons, andnotallarepoliticallyactive,but asignificantsubsetengagesinpoliticaladvocacyinoppositiontotheirhomeland’s authoritarianregime.Theyengageboth vertically,asindividualsoradvocacy groupswithinspecifichostcountries,and horizontally,asmembersof atransnationalpoliticalcommunityfocusedonasharedhomeland;theirglobal distributionhasbroadenedtheavailabilityofexternalsupport andincreasedthe effectivenessofbothtransnationalanddomesticallyfocusedadvocacyefforts.In theseefforts,NorthKoreanshaveactedaswitnessestoNorthKorea’sauthoritarian past,asspokespeopleforapeopledeniedvoiceinthepresent,andasstakeholders inboththeircountriesofresettlementandNorthKorea’spoliticalfuture.

Thus,theNorthKoreandiasporarepresentsafragmented,limited,butstill significantsourceoftransnationalandpluralisticcontentiouspolitics,ofakind thatissuppressedwithintheDPRKitself.TheNorthKoreanregime,foritspart, appearstoregardthisnascentdiasporaasapotentialthreat,andhastakensteps todissuade,discredit,anddeterdiasporamembersfromengagingincriticism andoppositionalactivityabroad.Thus,thoughitissmall,thepoliticalsignificanceoftheNorthKoreandiasporaaffectsbothNorthKorea’spoliticalsystem andtransnationalglobalpolitics.

ThissectionprovidesanoverviewoftheNorthKoreandiaspora,outlining migrationprocessesandresettlementdestinations.Itarguesforconceptualizing theseémigréswithinadiasporicframework:theirglobaldispersion,distinctive sharedidentity,andemergenttransnationaltiesqualifyasanascentdiaspora.It arguesthataddingaregime-centered, North Korea–focuseddimensionto traditionalprimordialistconceptionsofthediasporashedsgreaterlighton NorthKoreans’ politicalidentities,networks,andpatternsofpoliticalaction.

Thisallowsustoassesstheoften-outsizedimpactémigréshavehadonpolicyat ahost-countryandgloballevel,andallowsustoplaceNorthKoreaincomparativedialoguewithotherdiasporapopulationsfromhomelandsunder authoritarianrule.

DescribingNorthKoreanMigrationandResettlement

What – orwhom – dowemeanby “NorthKoreandiaspora”?Empirically,two geographicallyoverlappingbutsociallydistinctnetworkscompriseNorth Korea’soverseaspresence.OneischieflycomposedofNorthKoreandiplomats andoverseasworkers,organizedincorporatistfashionandaffiliatedwiththe regimewhilepostedabroadonbehalfoftheDPRK’seconomicandpolitical purposes(Hastings2016).TheothernetworkofNorthKoreansworldwide, however,isamorerecentdevelopment:migrants,refugees,anddefectorswho haveexitedNorthKoreatoseekalifeelsewhere.Ifocusprimarilyon thissecondnetwork,whichhasgrowninsizeandinfluenceevenastheregimeaffiliatednetworkhascomeundersignificantpressure.AlthoughtheDPRK maintainsadiplomaticpresenceinapproximately fiftycountries(East-West Center/NCNK2019),UNsanctionsandotherinternationalpressureshave constrictedandretrenchedNorthKorea’sregime-affiliatedpresence.As aresult,thepopulationofNorthKoreansaroundtheworldhasshiftedfrom regime-affiliatedtoincreasinglyoppositional.

ConventionalwisdomonemigrationfromtheDPRKusuallyportraysNorth KoreandefectorsandrefugeesascongregatingintheRepublicofKorea(ROK), withanundocumented,transitorypopulationofunknownsizeinnortheastern China.Thatperceptionremainslargelyaccurate,althoughthepopulationin Chinamayhavecontractedduringtheglobalpandemicduetostrictborderand mobilitycontrolsonbothsidesoftheChina–DPRKborderandpost-pandemic repatriationeffortsbytheChinesegovernment(Yoon2023).AsofJune2023, anestimated33,981defectorshadenteredtheROK(MOU2023) – byfarthe largestconcentrationofpermanentlyresettledexilesoutsideDPRKterritory.

Undertheethnicnationalistnarrativeframeworkarticulatedinbothnorthand south,whereinbothhalvesofthepeninsulaarepartofasingleKoreannation (Miyoshi-Jager2003; Shin2006; Grzelczyk2014),thisresettlementisnotquite diasporic migration.NorthKoreanswhomigratetoSouthKoreaostensibly remainwithinapeninsular “homeland”– eventhoughthesouthernhalfofthis homelandhasfunctionedasaseparatecountryforoverseventyyears,and NorthKoreanémigrésareseparatedfromhome,whetherthathomeisdefinedas a physicalplace oforigin,orinthesenseofone’s familyandcommunity.By contrast,aregime-centerednotionofdiaspora – focusedonthecommonalityof

NorthKoreanresettlementinSouthKoreaandglobally (2000–20)

emigrationfromterritorycontrolledbytheDPRK – capturesthisdislocation, andalsoallowsustoplacemigrationandresettlementtoSouthKoreain abroaderinternationalandcomparativecontext.

Thisshiftmattersbecauseoflate,anincreasingnumberofNorthKorean emigrantshaveclaimedasylum,soughtrefugeestatus,andattemptedresettlementincountriesapartfromtheROK.NorthKoreanonwardmigrationfrom SouthKoreahasalsoincreased,makingtheROKnotjustaresettlement destination,butatransitpointinglobalmigrationchains – chainsthatoriginate insideNorthKorea,butnolongerbeginandendonthepeninsula(Song2015; SongandBell2019). Figure1 comparesresettlersarrivinginSouthKoreato NorthKoreansapplyingforasylumworldwide.1

TheUNHCRstatisticsshownin Figure1 likelyunderstatethesizeofthe globalNorthKoreandiaspora,duetodefinitionandmeasurementproblems.For differentreasons,China,Japan,andSouthKoreaallavoidapplyingthelabels “refugee” or “asylee” toNorthKoreanescapees,soJapanandChinaare excludedfromthe “global” line.Inaddition,UNHCRhasrefusedtomake formalrefugeedeterminationsforNorthKoreansinSoutheastAsia,duetothe geopoliticalcomplexitiesthathaving “twoKoreas” posesfordiplomaticrelationsandtheoptionofsimplysendingsuchindividualstoSouthKoreafor resettlement(HanVoice2016:5).

1 DataonSouthKoreafromROKMinistryofUnification(www.unikorea.go.kr/eng_unikorea/rela tions/statistics/defectors).Globaldatauses “asylumapplications” fromUNHCR’sRefugeeData Finder(www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/download/?url=5wmdYY).TheUNHCRdataexcludes somecountries,andNorthKoreanswhoinitially claimasylumabroadcouldeventuallyresettlein SouthKorea,sothetwocategoriesdepictedareneitherexhaustivenormutuallyexclusive.

South Korea Global

Figure1

Evenwherestatisticsarereported,neitherasylumnorrefugeenumbers completelycapturetheNorthKoreanémigrépopulation.Notallasylumapplicationssucceed;inEurope,thereareyearswherecountriesrejectedthemajority ofNorthKoreanasylumclaims(Section3).Insomecases,suchasthe Netherlands,NorthKoreanasyleeshaveresettledunderComplementary ProtectionsStatusratherthanasrefugees(Burt2015).Finally,UNHCR’s “refugee” figureisthetotalDPRK-originrefugeepopulationin-country,meaningthatindividualsenterthatcategoryeachyear,whileothersdropoutdueto naturalization,death,andonwardmigration.Thismakesestimatesderivedfrom UNHCRdatauncertain,andbesttreatedasalowerboundorbaseline;thesedata showedNorthKoreanswithrefugee/asyleestatusintwenty-fivedifferent countriesfrom1990to2020(Figure2).2

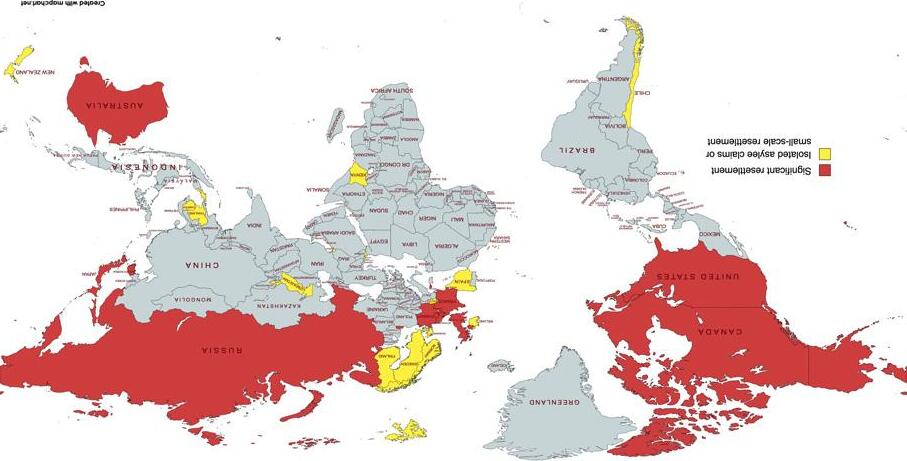

Somecountries(markedyellowonthecoloredversionof Figure2,ormedium grayonthegrayscaleone)recordedonlyahandfulofapplicantsinisolatedyears andnoneinothers,suggestingcasesofindividual/small-groupdefection.These includedCambodia(1996/2007),Chile(2015),Finland(2020),Kenya(2019), Kuwait(2015/2016),Spain(2015),andUzbekistan(1996).Others,likeIsrael (2013–20)andKyrgyzstan(2006–10),showlownumbersforasinglestretch,and nothingafterwards.Inothercases(redordarker-shadedin Figure2),including theUnitedKingdom,Germany,Canada,andtheUnitedStates,thenumbersof individualsseekingasylumorobtainingrefugeestatusarelargerandremain consistentoveryears,suggestingmoresustainedpatternsofmigrationand resettlementcorroboratedbyjournalisticoracademicinvestigation. Section3 ofthisElementassessesthefactorsthathaveshapedthisglobaldistribution.

ThereispresentlylittleresearchontheglobaldimensionsoftheNorth Koreandiaspora.ArobustliteratureontheKoreandiasporaconcentrates primarilyonhistoricalprocessesofmigrationaroundandbeyondtheKorean peninsula(R. Kim2008;J. Kim2016;A. Park2019),oronvariousformsof transnationalKoreanpolitics(N. Kim2008; Chubb2014;S.Y. Kim2014; Lie 2014;H.O. Park2015).AthirdstrandofscholarshipexploresSouthKorean economicmigrationandROKpolicytowardimmigrantsandtheoverseas Koreancommunity(ParkandChang2005; Lee2010, 2012; Brubakerand

2 Thesewere:Australia,Belgium,Canada,Cambodia,Chile,Denmark,Finland,France,Germany, Ireland,Israel,Kenya,Kuwait,Kyrgyzstan,Luxembourg,theNetherlands,Norway,Russia, Spain,Sweden,Switzerland,Thailand,Uzbekistan,theUnitedKingdom,andtheUSA.

Asof2017,UNHCRrecordedrefugees/asyleesinfourteenadditionalcountries,butremoved themlaterforreasonsthatareunclear:Angola,Austria,CostaRica,Egypt,Hungary,Japan, Mexico,NewZealand,Philippines,Poland,Singapore,Turkey,Ukraine,andYemen.

Darkshading(orred,inthecolorversion)denotesrefugeepopulations>25foratleastoneyearin thisperiod.Mediumgray(oryellow,ifincolor)denoteseitherarefugeepopulation<25forall years,orasylumclaimswithoutrefugeeresettlement.

Figure2 NorthKoreanrefugees/asyleesworldwide(1990–2020)

Kim2011; Yoon2012; Kim2013; Mylonas2013; Kim2016; LeeandChien 2017; TsudaandSong2019).Forallitsvalue,thisworkdoesnotexplainthe rolethatmembersoftheNorthKoreanexilecommunityhaveplayedin contemporarydomesticandglobalpolitics.Theseoutcomesbecomemore apparentwhenweconceptualizeaspecific “wave” ofmigration,motivatedby adesiretoleaveNorthKorea,thatlayersontothepreexistingdiaspora,andthat isembeddedinlargerpatternsofKoreandiasporicpoliticswithoutbeing subsumedcompletelybythem.

ResearchonNorthKoreanémigrécommunitiesisunevenlydistributedand almostexclusivelycomposedofsinglehost-countrycases.Thereisextensive academicandpolicyworkonNorthKoreanresettlementinSouthKorea, includinghowNorthKoreansperceiveandengageintheROK’scapitalist democraticsystemandonthechallengesofeffectiveresettlementandintegration(Choo2006; Lee2016;S. Kimetal.2017; Hur2018, 2020; Denney,Green, andWard2019; Park2023).KoreancommunitiesinJapanhavealsoreceived in-depthethnographicandanthropologicalattention.OtherNorthKorean émigrécommunities,however,havebeenreportedonsolelybyjournalists (Canada)orlargelyoverlooked(theNetherlands,etc.).ThisElementbuilds onexistingworkbydrawingthesecasestudiesintocomparativeconversation, fillinginempiricalgaps,andtreatingNorthKoreanémigrésasanetwork definedbysharedhomelandorientation – asignificant,emergentformof transnationalKoreanmobility,identity,andpoliticalengagement.

ANorthKoreanDiaspora?RegimeTypeinDiasporicPolitics

DiscussionsofNorthKoreanswho’velefttheDPRKimmediatelyencounter difficultiesofnomenclature,whichshapepoliticalmeaning,bothinKoreaand moregenerally(Chung2008; BrubakerandKim2011).InSouthKorea,these individualsare talbukja, saetomin,or,officially, bukhanitaljumin; 3 English termsinclude defectors, refugees, exiles, migrants, resettlers,and immigrants Theredebatesovernomenclaturereflectbroadercomparativeconversations: Hamlin,forexample,arguesagainstreifyingbinarydistinctionsbetween migrantsandrefugeesbecausesuchachoiceimplies,misleadingly,thatmotivationsforbordercrossingaredistinct,thatrefugeesareneedier,andthat “true” refugeesarerare(2021:6–18).

Asanalternative,theuseof “diaspora” canavoidsomefalsebinaries,treating NorthKoreansworldwideasaconceptualcategoryorganizedbyhomelandof

3 OverseasKoreansarereferredtoeitherbythehomeland-oriented gyopo,orthemoretransnationalandethnically-oriented dongpo (“compatriots,” butwithafamilialconnotation).ANorth Koreandefector ’sanalysisofterminologyappearsin LimandZulawnik(2021:73–77).

origin,butcomposedofindividualsandfamilieswithmultiplemotivations, levelsofneed,andtypesofengagementinpoliticallife.

Adiasporicframework,however,doesnotresolvealldefinitionalproblems; thetermremainscontestedandmultivalent.Theuseof “diaspora” inthis Elementparallels Gamlenetal.(2017:511),whousethetermtomeansimply, “emigrantsandtheirdescendants.” Incontrast, Brubaker(2005:12)defines diasporasbysubjectiveself-perception: “anidiom,astance,aclaim.” Others combineobjectiveandperceptualelements: Vertovec(2009:5)describes “an imaginedcommunitydispersedfromaprofessedhomeland” (seealso Safran 1991:83).BettsandJonesdefinediasporasas “communitiesthataretransnationallydispersed,resistassimilation,andhaveanongoinghomelandorientation,” whileremindingusthatnotallgroupsofexilesadoptadiasporicstance (2016:3–5).Adamson(2019)describesthemas “constitutedbyanarrativeof dispersion,attachmenttoahomeland,andasenseofgroupidentity.” Shainand Barth(2003:452)describeadiasporaas:

Apeoplewithacommonoriginwhoreside,moreorlessonapermanent basis,outsidethebordersoftheirethnicorreligioushomeland – whetherthat homelandisrealorsymbolic,independentorunderforeigncontrol.Diaspora membersidentifythemselves,orareidentifiedbyothers – insideandoutside theirhomeland – aspartofthehomeland’snationalcommunity. Inthissense,NorthKoreansbeyondtheKoreanpeninsulaareadiaspora,atleast anemergentone.Theyaredispersedfromthehomeland,whetherthathomeland isconceptualizedastheKoreanpeninsula;asthecountryofNorthKorea;oras aspecificlocalcommunityoffamilialancestryandorigin.ManyNorthKorean émigrésshareacommonsenseofidentityandevenprideintheirgroup,ifnotthe regimethatgovernsit(see Section4 ofthisElement; GreenandDenney2021); theyarerecognizedasNorthKoreansbyothers.Theyspeakadialectclearly distinguishablefromSouthKorean,adifferencethatcanconditionmigrants’ networkstructureandpatternsofpoliticalincorporation(Liu2021).ManyNorth Koreanssharestrongerwithin-network(bonding)tiesthan(bridging)tiestothose outside;manyhavealsoformedtransnationallinkagesbasedontheirshared countryoforigin – particularlyonanti-regimeadvocacy,andsometimesas adeliberatealternativetodeepeningtieswithnon–NorthKoreancivicorganizationsinhostcountries(Bell2013, 2016:265; YeoandChubb2018:4).Indeed,the broader “NorthKoreandiaspora” haswithinitasizable “defectordiaspora” engagedinpoliticalactivism – thoughinNorthKorea’scase,theactivistsubset isacomparativelylargefractionofthewhole(see Section5).

Atthesametime,thistransnationalnetworkofNorthKoreanexilesis overlaidonto,andnestedwithin,alargerKoreandiasporathatemergedearlier,

generatedbydifferentcircumstances,timing,andprocesses. Cohen(1997) classifiesdiasporasintofourtypes:victim/refugee;imperial/colonial;labor/ service;andtrade/commerce.Muchpreviousscholarshiponthebroader Koreandiasporahasemphasizeditscolonial/postcolonialandeconomic dimensions.4 NorthKoreans,however,hewclosertothevictim/refugeetype, meaningthatspecificallynorthernrefugeediasporathreadsareoverlaidand wovenintoabroader,existingKoreanpostcolonialandlabor-based/commercialdiaspora.

Thisnarrativeishighlystylized;theNorthKoreandiasporaitselfisnot monolithic,noristhebroaderdiasporainwhichitisembedded.North KoreansinSouthKoreaself-identifywiththenationalcommunitytovarying degrees,anddefinethatnationalcommunityinarangeofways(Hur2018).In theUnitedKingdom,identityperceptionsstratifybyage:youngerNorth Koreansidentifyprimarilyas “foreignimmigrantsinamulticulturalcountry,” whileolderNorthKoreansaremorelikelytothinkintermsofmembershipin specificallyKoreandiasporanetworks(Watson2015).As Sections4–5 show, however,thisstylizednarrativeisusefulforunderstandinghowNorthKorean emigrationandresettlementinareaswherethereisapreexistingKorean diasporacan both produceaseparatediasporiclayerwithdistinctivedynamics, and alsogeneratenewintra-diasporiccleavagesalongregime,language,and otherlinesforthosewhocontinuetodefinethediasporawithreferencemostly tosharedethnicity. “Diaspora” ismultivalentenoughtoallow fluidity:North Koreansaresimultaneouslymembersofatransnationalnetworkspecificto NorthKorea,andmembersofabroaderKoreancommunitythathasbeen dispersedbyglobalforcesofviolenceanddevelopmentsincethebeginning ofthetwentiethcentury.

What,then,isthevalueoffocusingmorenarrowlyonthe North Korean diaspora,andcenteringtheauthoritariannatureoftheDPRKregimeinthat analysis?Omittingthenondemocraticnatureofthehomeland – inNorthKorea orgenerally – overlooksasignificantfactorthatconditionsemigrationand resettlementprocesses;systematicallyaltersthenatureofpoliticalengagement withthehomelandbutalsowithhostcountries;andalsoaltersthehomeland government’scalculationsaboutdiasporicpolicy.Ashwini Vasanthakumar (2022:22)notesthatnormatively, “exileisassociatedwithunjustandundemocraticpoliticalorders.” Empirically,recentscholarshiphasdocumentedthat authoritarianismdiffersfromdemocracysystematicallyintermsofpatternsof emigrationpermitted(MillerandPeters2020);thediasporicmanagement

4 TransnationalismisdeeplyembeddedinstudyofKoreanidentityandmembershippolitics(Park 2005; Kim2008; Kim2011; Kim2016).

policiesthatnondemocratichomelandregimesadopt(DelanoandGamlen 2014; Tsourapas2018);thewaysthatcitizenswhogrowupunderauthoritarianismperceiveandengageinsubsequentdemocraticpolitics(Pop-Elechesand Tucker2017);andthestrategiesofpoliticalcontentionemployedwithrespect tothehomeland(BettsandJones2016).NorthKoreanexiles,likeexilesfrom otherhomelands,possessakindofpoliticalandmoralagencythatchallenges traditionalnotionsofpoliticalcommunity,membership,andobligation (Vasanthakumar2022);theyarenotjustwitnessestoNorthKorea’sauthoritarianpastandpresent,butrepresentativesofitspeopleinaworldwherethe regimelimitsexternalvoiceandaspirantstakeholdersinitspoliticalfuture.

Inshort,althoughauthoritariandiasporas5 sharesomefeaturesincommon withdiasporasfromdemocracies,theopportunitystructureandpatternsof diasporicpoliticalactionalsodifferinsystematicandimportantways.6 This Elementseekstoforegroundtheseinitsnarrative,withoutlosingsightofwhere andhowdiasporicactivismmightoccurintheabsenceofhomelandauthoritarianrule.

RoadmapfortheElement

TherestoftheElementproceedsasfollows. Section2 beginswithanoverview ofhowtheauthoritarianregimeinNorthKoreahasattemptedtocontroland manageitsdiaspora,historicallyandinthepresent.Theregime’sapproachto diasporamanagementhasshiftedasstate-sponsored,pro-regimegroupsno longercomprisethemajorityofNorthKoreansabroad,andoppositionalvoices haveincreasinglyinfluencedtheinternationalcommunity’spoliciestowardthe DPRK.Pyongyangdissuadesemigration;discreditsthosewholeavetodomesticandinternationalaudiences;andattemptstodeteranddisruptdiasporic abilitytoengageinoppositionandcriticism.Itemploysdomesticandinternationalpropagandanarrativesaboutdefection/re-defection;attemptstopreventlinkagesbetweendefectorsabroadandhomelandresidents;andthreatens politicalviolence,includingassassination,tostopdiasporamembersfrom engaginginanti-regimepoliticalspeechandaction.Throughtheseactivities, theregimeseekstomonopolizerepresentationoftheNorthKoreanpeople abroad,counteringandsuppressinga “defectordiaspora” thathasincreasingly contestedthelegitimacyofthatmonopolization(Ragazzi2012).Extraterritorial discreditationandrepressiveviolencealsoseektoconfrontemergentcontention

5 Here “authoritariandiaspora” means “adiasporadispersedfromahomelandpresentlygoverned byanon-democraticregime.” Thisisdistinctfrom LoxtonandPower(2021;465),whousethe termtomeandispersionofformerauthoritarianregimeofficialswithinacountry’spolitical system.

6 ThiswasalsotrueofSouthKoreaundermilitary-authoritarianrule,apointrevisitedin Section6.

andoppositionoverseas,beforeitcaninfiltratethehomeland’sborders,thereby bolsteringregimesecurity.Theseauthoritarianeffortscreatetheconditions underwhichNorthKoreandiasporicpoliticsemergeandevolve.

Section3 askswhereNorthKoreanswholeavetheirauthoritarianhomeland resettleandwhy.WhatfactorshaveshapedtheglobaldistributionoftheNorth Koreandiaspora?Itsuggeststhatcontestationovercitizenshipinadivided Koreashapesglobalpatternsofmigration:althoughNorthKoreansmeetlegal andcommunitarianstandardsforcitizenshipintheROK,actuallyclaimingthat citizenshipinthirdcountriesduringescapeisarduous,andoftencontingenton geopoliticalfactors,whichhascomplicatedtheNorth-to-Southmigrationand resettlementpipeline.Additionally,manyhost-countryimmigrationcourtshave interpretedKoreancitizenshipinwaysthatforcereversemigration,reconcentratingNorthKoreanémigrésontheKoreanpeninsula.TheresultisaT-shaped diaspora:heavilyconcentratedinSouthKorea,butwithabroad, “thin” global distributioninahandfulofcountriesthathaveeithertemporarilyorindefinitely permittedsmall-scaleNorthKoreanresettlement.

Section4 analyzesNorthKoreanémigrés’ politicalbeliefs,especially aboutdemocraticcitizenship.NewsurveydatashowsthatNorthKoreans intheUnitedStatesemp hasizeconceptionsofdemocraticcitizenship orientedtowardcivillibertiesandrights,andhaveinternalizedmany normsofdemocraticcitizenshipshare dbyAmericancitizens.Surveydata alsosuggestthatformanyNorthKoreans,prideinone ’sidentityand exerciseofrightsasanAmericanoccurinparallelwithstrongremaining communalattachmenttotheirethnicho meland,indicatingthatcivicpatriotismandethnicnationalismcanbedelinked.

Section5 examinesNorthKoreanémigrés’ politicalbehavior.Ingeneral, NorthKoreanswhohaveresettledindemocraciesshowahighlevelofcivicand politicalengagement.TheT-shapeddiasporadescribedin Section3 alsofacilitatesmultilevelpoliticalaction:membersofthediasporaareoftensimultaneouslyengagedwithintheirhostcountriesandtransnationally,anddiasporic “anchors” inmultiplecountrieshavebroadenedaccesstoexternalanimators thathavebeencriticaltodiasporicadvocacyatboththedomesticandinternationallevels(BettsandJones2016).Thisstructurehasenabledthediaspora, despiteitssmallsize,tosignificantlyinfluencehost-countryandinternational policytowardtheKoreanpeninsula.

Section6 assessestheimplicationsoftheElement’s findings.Itarguesfor amultilayeredviewofthediaspora,onethatincorporatesregime-specificforms ofpoliticalidentificationandtransnationaloppositionalongsidehistoricaland primordialistconceptionsofdiaspora.PlacingtheNorthKoreandiasporic “wave” incomparativecontext,itarguesthatthisElement’ssystematic

incorporationofregimetypeshedslightondevelopmentsworldwide,from HongKongexpatriatespursuinga “diasporicmodelofopposition” (Economist 2021)toadvocacyeffortsbyCubansintheUnitedStatestoSvetlana TikhanovskayaorganizinganoppositionmovementfromoutsideBelarus’ borders.Thesectionconcludesbyoutliningquestionsforfutureresearch, suchashowdiasporasthatemergefromauthoritarianhomelandschange underdemocratization;howoppositionalor “defector” diasporasrelateto politicallyinactiveorpro-regimediasporicsubgroups;andwhatpatternsof diasporicpoliticalactivitystabilizeorunderminehomelandauthoritarianrule.

2NorthKorea’sDiasporaManagementPolicies

TheauthoritariannatureofNorthKorea’shomelandregimefundamentally structuresandshapesdiasporicpolitics.Pyongyang’sapproachtodiaspora management,however,hasevolvedovertime.Foryears,theDPRKreliedon corporatistcontrolandpro-regimepropagandatomanageNorthKoreansoverseas:exportingworkersto(mostly)otherautocracies/hybridregimesin exchangefortheeconomicbenefitsthatsuchout-migrationprovided.Asthe proportionofthediasporapoliticallyopposedtotheregimeincreased,North Koreashiftedtactics.Today,itseeksto dissuade mostcitizensfromleaving;to discredit thosewholeaveandvoicecriticismfromabroad;and,usingtransnationalrepression,to deter and disrupt organizeddiasporicopposition.

Migrantsaretargetsof “twokindsofpolicies:theemigrationanddiaspora policiesoftheircountriesoforigin,andtheimmigrationandimmigrantpolicies ofdestinationcountries” (Muller-Funk2019).7 Whilealmostalldemocracies allowrelativelyopenout-migration,autocraciesvarygreatlyintheirapproaches, withtheDPRKonthemostclosed,restrictiveside.Scholarssuggestthatautocraciesmustbalancetheeconomicbenefitsofemigrationwithriskstopolitical stability.Emigrationisa “mechanismofdemocraticdiffusion” (MillerandPeters 2020:2);people “votingwiththeirfeet” cantriggermassexitandregimecollapse, butevenwithoutthatworst-casescenario,migrationcancreatecross-border flowsand “linkage” associatedwithgreaterlikelihoodofdemocratization (Hirschman1993; LevitskyandWay2010).Destinationregime-typealsomatters:emigrationtodemocraciesisassociatedwithgreaterlikelihoodofhomeland regimetransition,anddiasporashavecontributedtobothanti-regimemobilization(Nedelcu2019;NugentandSiegel2021;EsbergandSiegel2023)and democratization(Levitt1998; Camp2003; Bermeo2007; Chauvierand Mercier2014; Kapur2014; Mahmoudetal.2017).Thus,eventhoughmost

7 Untilrecently,comparativescholarshiponimmigrationfocusedonwealthydemocracies(Peters 2017).

emigrationiseconomic,autocraciessetemigrationpoliciesandmanagediasporas withbotheconomicincentivesandthelogicofpoliticalsurvivalinmind.

NorthKoreaisinmanywaysprototypical.TheDPRKishighlyrestrictiveof emigration,butallowsitinselectcaseswhereperceivedeconomicbenefitsare high.Pyongyangalsoappearsto findmigrationtoautocracies(especially China)lessthreateningthandemocracies(especiallySouthKorea,butalso theUnitedStatesandtheUnitedKingdom),consistentwithconcernabout reversediffusionofdemocraticideasandmobilizationfromabroad. Accordingly,Pyongyangattemptstoenmeshregime-sponsored(largelylaborfocused)emigrationwithinautocraticcountries,whereitcanberegulatedvia corporatistcontrolandpro-regimepropaganda.Tomanagepoliticalrisks,the regimedissuadesout-migrationaltogetherthroughbordercontrolsandbyusing “re-defectors” instatemedia;discreditsthosewhodefectindomesticand internationaloutlets;andseekstodeteranddisruptpotentialoppositionfrom engaginginanti-regimemobilizationandactivismabroad.

CorporatistControlandPro-regimePropaganda

Beforethe1990s,anyNorthKoreanabroadwasalmostcertainlyaffiliatedwith theregime:diplomats,tradingcompanyrepresentatives,orthoseassociated withvarious “friendshipassociations.” TheDPRK’soverseaspresencetypicallyoperatedalongregime-ledcorporatistprinciples,inwhich “associational affiliationsarestructured,non-competitive,andvertical,” existinginhierarchy ratherthanthediverse,competitive,andcrosscuttingassociationalformsthat characterizepluralistsystems(Gallagher2020:4).InsideNorthKorea,asin otherLeninistsettings,organizationallifeformsa “transmissionbelt” between stateandsociety(Lankovetal.2012).Abroad,Pyongyanghasappliedsimilarly corporatistapproaches:regime-sentdiasporagroupsarestate-controlledand hierarchicallyorganizedtoberesponsivetoregimedirectives.

MovementinandoutoftheDPRKisvirtuallyforbiddenunlesssponsored andcontrolledbytheregime;NorthKoreahasgenerallysoughttolimitits overseaspresencetosituationsorcountriesinwhichitcouldmaintaincorporatistcontrol.Pyongyang’sexternalrevenue-earningendeavors,forexample, reliedheavilyondiplomaticoutpostsandstatetradingcompanies,projecting aregime-ledeconomicpresenceintotheworldthatoperatedasanextensionof domesticcorporatiststructures(Hastings2016).Stateexportofworkershas beenorganizedsimilarly:ministries,departments,orstate-ownedenterprises arrangeandsignlaborcontractsthatdispatchworkersontightlycontrolled overseasassignmentswheremanagerscanisolateworkersinspecifichousing, monitortheirmovementsandinteractions,andcontrolthe financial flowsthat

theirworkgenerates(Arteburn2018;Dept.ofTreasury2020).Thesetemporary assignmentsareofteninnondemocraticsystemswhereDPRKpoliticalcontrol isnotobjectionabletothehostgovernment.NorthKoreahasalsocultivated relationswithanetworkofsympathetic “KoreaFriendshipAssociations” or “JucheIdeaStudyGroups,” generallyMarxistorCommunistinpoliticalorientation,establishingasmanyas200worldwidefromthe1960sonward(Gauthier 2014; Dukalskis2021:159–183; Young2021;onpro-NorthKoreagroupsin theUnitedStatestoday,see EberstadtandPeck2023).Whiletheseorganizationsdonotnecessarilycarryoutdiasporamanagement,theyareexamplesof theparty-ledpresencethatPyongyanghassoughttoprojectintotheoutside world.

Thiscorporatistapproachtodiasporamanagementincludesthepro-North KoreadiasporicpresenceinJapan.Inthemid-1950s,apro-DPRK,left-leaning organizationcalledChongryon/ChosenSoren(GeneralFederationofKorean ResidentsinJapan)wasfounded “underthedirectcontrolofNorthKorea” (Shipper2010:60);fearofrepressioncombinedwithconnectionstotheDPRK helpedchannelChongryon’spoliticalmobilizationawayfromJapanesedomesticpolitics,andtowardsupportforPyongyangasthelegitimategovernmentof aneventual,reunifiedKoreanhomeland(Ryang1997, 2016; Lie2008; Shipper 2010).Chongryonbecamearobustorganization(morethanMindan,itsweakly supportedSouthKorea-alignedcounterpart),maintaininghundredsoflocal branches,apressoperation(includingthe ChosonSinbo newspaper),and aschoolsystemfromprimaryleveltoaDPRK-fundeduniversity(Ryangand Lie2009).

Overtime,however,thepro-DPRKdiasporainJapanhasprovendifficultto sustain.Chongryon’sinvolvementinthemassmigrationof90,000Koreans backtoNorthKoreainthelate1950s–1960sbegantocorrodesupportforthe DPRK,asreturneessharedinformationaboutmaterialdeprivationandpolitical repressioninNorthKorea(Morris-Suzuki2007; Bell2018, 2021).Erosionof supportacceleratedwiththegrantingofpermanentresidentstatusforKoreans inJapaninthe1980s,whichfacilitatedtravelbetweenNorthKoreaandJapan (Chung2006; Ryang2016).GovernmentpressureafterNorthKorea’snuclear testsandadmissionofabductionsintheearly2000sledtofurtherattritionand weakeningoforganizationaltiestoNorthKorea(Hastings2016),what Ryang (2016:13)calls “aprolongeddeathfor Chongryun asamassorganizationof KoreanexpatriatesinJapan.”

Today,Chongryon’smembershipisestimatedbetween30,000and70,000, afractionofitsformerstrength(Bell2019:32; Dukalskis2021:171).Beyond numericalattrition,thepro-NorthKorean “homelandorientation” ofKoreansin Japanhasalsodeclined,replacedbylong-distanceidealizationwithoutany

practicaldesiretorepatriate(Lie2008; Shipper2010, Bell2018).Chongryon itselfhasshiftedtowardadvocatingforminorityrightsinJapan(M.Kim2015; Dukalskis2021:173–174;forexamples,see ChosonSinbo 2015, 2018, 2019). Foritspart,PyongyanghasexcoriatedtheJapanesegovernment’s “antiChongryoncampaigns,” andNorthKoreanstatemediaemphasizes Chongryon’ssupportforthecurrentDPRKleadership.Therealizationthat Chongryonis “seeminglyheadedforacceleratedirrelevance” (Dukalskis 2021:177),however,highlightstheinadequacyofNorthKorea’sattemptsto maintainpro-regimediasporicorientation.Inthefaceoffast-erodingsupport, Pyongyanghashadto findnewtacticsforadiasporaincreasinglycomposedof individualsopposedtotheregime,andwillingtovoicethatoppositionand criticismfromabroad.

Dissuasion:PreventingDefection

The firsttechniquethatNorthKoreahasusedtomanagedissidencewithinthe diasporaisdissuasion:physicalbordercontrolsandinformationstrategies aimedatreducingcitizens’ abilityorwillingnesstoleave.

UnderKimJongUn,bordersecurityhastightened.AccordingtoHuman RightsWatch,controlsonmovementwithinNorthKorea,andacrosstheNorth Korea–Chinaborder,tightenedafter2012(Shim2015).Thesenumbersalmost immediatelyimpactedthe flowofNorthKoreandefectorsarrivinginSouth Korea,fallingbyhalffrom2011to2012(Jung2021).TheCOVID-19pandemic intensifiedthesemeasuresfurther,asNorthKoreaessentiallycloseditsbordersin January2020andhasallowedlittlemovementinoroutsince,evenastradewith China – typicallyconsideredaneconomiclifelineforNorthKorea – droppedby over90percent.InAugust2020,theKoreanWorkers’ PartyPolitburoestablished restricted “bufferzones” alongtheChineseborderanddemotedMinisterofState SecurityJongKyong-thaek,supposedlyforhavingfailedtostopcross-border traffic(KCNAWatch2020;M.S. Kim2020; Weiser2021).

TheserestrictionsappeartohavedecimatedmigrationoutofNorthKorea, whichreliesonmovementacrosstheNorthKorea–Chinaborderandisheavily intertwinedwithcross-bordermarketactivity(Lee2021).Whilemuchcrossbordertrafficisnotintentionalpermanentdefection,almostalldefectorsleave NorthKoreainitiallyviaChina,meaningthatborderclosurescutoffthemajor exitpoints.Only229NorthKoreansenteredtheROKin2020,63in2021,and 67in2022(Jung2021;MOU2023).Thoughalackofstatemedicalcapacityhas limitedtheefficacyofDPRKcontrolsforpandemicmanagementandpublic health,thesemeasureshavenonethelessenhancedthestate’scontrolover marketsandeconomicactivity.ManyNorthKoreanentrepreneursandmarket

participantsdependedontradewithChinatomakemoney,soborderclosures willlikelyweakentheirleverageandstrengthenthestate(GreitensandKatzeff Silberstein2021),potentiallylimitingoutboundmigrationforthemediumto longterm.

Inadditiontoblockingoutboundmigration,NorthKoreaalsoseeksto dissuadecitizensfromleavingbyusingtestimonyfrom “re-defectors”:individualswholeftforSouthKoreabutthenreturnedtotheDPRK.Whetherthese individualsreturntoNorthKoreafreelyisunknown,anddebated.ROKlawmakershavesuggestedthatsomeindividualsweretrickedor “lured” into returningonfalsepremises,orduetopressureonfamilymembersinthe North(Harlan2012;S.G. Park2013).In2021,SouthKoreanauthorities indictedaNorthKoreanwomanintheSouthfor,asanMinistryofState Securityagent,persuadingotherdefectorstoreturntotheDPRK(Yonhap 2021).Othershaveimpliedthatre-defectorscouldhavebeenspieswhoposed asdefectorsandthenreturnedtogeneratecredibilityforregimepropaganda (Lee2013).Athirdperspectivetakesseriouslythenotionthatdefectorsmight findlifeinSouthKorea,andespeciallyseparationfromlovedones,difficult enoughtoreturnoftheirownvolition(J.M. Park2013; McCurry2014; Sunwoo 2014; GriffithsandKwon2017).Afteraspateofre-defectorpressconferences inNorthKorea,severaladditionaldefectorslivinginSouthKoreadeclared adesiretoreturn(Haas2018).

Thetotalnumberof “re-defectors” isunknown.Around700(2.6percent) NorthKoreanresettlersinSouthKoreawereunaccountedforina2015study, butthemajoritywerethoughttohavemigratedonward,ratherthanhaving returnedtotheDPRK(Lankov2020).TheMinistryofUnificationcitedthirty re-defectionsfrom2012tothepresent;othersestimatehighertotals(Scarlatoiu etal.2013; McCurry2014).Thelastpubliclyknowncaseofre-defectionwas onNewYear ’sDay2022,byatwenty-nine-year-oldmanwho’dbeeninSouth Koreaonlyfourteenmonths;beforethat,thereweretwore-defectionattempts in2020,onesuccessfulandoneunsuccessful(Choe2020; Kasulis2020;Lee andKim2022).Ofthirtypeoplewhoreturnednorth,atleastsixhavedefected again,returningtotheSouth(Lankov2020).

TheNorthKoreanregimeemploystelevisedpressconferenceswithredefectorstohighlightitsownostensiblebenevolence.Priorto2012,theregime hadonlypublicizedonere-defection:YuDae-junin2000,whoreturnedto Seoultwoyearslater(NewYorkTimes2002; Cathcartetal.2014:155).InKim JongUn’searlyyears,however,Pyongyangheld7–8additionalpressconferences,emphasizingthetrickery,classdivision,discrimination,andpoortreatmentthatdefectorsencounteredinSouthKoreaandcontrastingthatwiththe benevolenceandgenerosityofNorthKorea’sleadership(Gleason2012;Kang

2014).The firsttwopressconferenceswerein2012;anotherhalf-dozenorso followedin2013,usuallywithmultiplere-defectorsspeakingateach.While publicpressconferenceshavedeclinedsince2013,reportingasof2018indicatedthatre-defectorsweremakingpublic-educationalappearancesinborder areastocautionpeopleagainstdefectionandtosharetheirregretoverleaving (Y.J. Kim2018).Thisapproachemphasizesthestate’swarmwelcomeofthose whoreturn,butalsoallowstheregimetousecitizens’ voicestospeakforthe state,promotingtheNorth’sofficialnarrativeandcriticizingSouthKorean politicalauthorityandcultureatthesametime.

Severalthemesinthesepressconferencesaugmenttheregime’sdissuasion message.First,manyspeakersdescribebeingtrickedintoleaving,bySouth Koreanintelligence(KCNA2012a; KCNA2013a; KCNA2013b)or “agentsof thepuppetgovernment” ofSouthKorea(Jin2013;Kang2014);brokersand “fleshtraffickers” (KCNA2012b; KCNA2013a; KCNA2013c);orgreedy familymemberswho’dalreadydefected(KCNA2013d).Theallegationthat defectionsareactually “abductions” donebydishonestROKintelligenceagents alsoappearsina2016CNNvideo,inwhichWillRipleyinterviewsthefamily ofawomanwholeftforSouthKorea(CNN2016).

AsecondthemeisthedifficultyofdailylifeandtreatmentofNorthKoreans assecond-classcitizensinaSouthKorean “societyofdarkness” (Jin2013).The languageisnotsimplythatofeconomicstruggle,thoughconferencesdo describehow “peoplelikeushavenomoneyandcannotobtainwork” (KCNA2012a; KCNA2013a).Itisalsoanemotivelanguageofcoldheartedness,rejection,andpain –“unbearablescornandhumiliation ... [and] despair” (Jin2013).Defectorsdescribebeingtreatedas “subhuman,” findingit “hopeless ... toopainfultolive” (KCNA2012b; KCNA2013b).

BleakportrayalsoflifeintheSoutharecontrastedwithKimJongUn’s warmthandbenevolence.In2013,Kimappearedtosetasideharshpunishments previouslyappliedtothosewhoattemptedtoleave;statemedianoted, “Thanks tothedeepaffectionandgenerosityofKimJongUn,traitorscanstilllive normallivesaslongastheyrepent” (Kang2014).Familiesofthosewho’dleft fortheSouthwereaskedtoconveymessagesthatreturningdefectorswouldbe welcomedratherthanpunished(J.M. Park2013).Pressconferencesechothis theme,oftenpersonallylinkingittoKimJongUn.In2012,oneoftheearliest re-defectorssaid, “ThedearrespectedKimJongUndidnotblamemewhodid somanywrongsinthepast,butbroughtmeunderhiswarmcare.Heshowed profoundlovingcareforme” (KCNA2012a,quotedinCathcartetal. 2014:156).Similarly,anarticleontheLaos9 – nineyoungdefectorsapprehendedinLaosandrepatriatedtotheDPRKviaChinain2013 – quotedanother re-defectorassaying, “Insteadofblamingyouforthepathoftreason,the

motherlandwillengageyouinawarmembraceandtakecareofyou.Yourpast ofcrimewillbeerased” (Jin2013).Statemediasubsequentlyreleasedfootage oftheLaos9inwhichtheyclaimedtobecontentandpatrioticallyloyal;one expressedadesiretojointhemilitaryto “protecttheMarshal[KimJongUn],” whileanothersaidhe “shouldonlytrusttheMarshalandfollowthatpath [studyinghard]torepayhim” (Kang2014b).Re-defectorstypicallydonot justexpressgratitudefortheregime’sbenevolenceandmercy,butalsosignal redoubledloyaltyandwillingnesstosacrificefortheNorthKoreanregimeand leadership.

Re-defectorpressconferences,then,appearaimedatseveralpurposesand audiences.Firstisthedissuasivemessageforthedomesticaudience,which appearsparamount:don’tleaveNorthKorea,becausethereisnothinginSouth Koreaforyou.Additionalorsecondarymessaging,however,appearstobe aimed(potentially)atNorthKoreanswho’vedefected,urgingthemtoconfess andreturntotheirhomelandwithoutfearofpunishment.Re-defectorsdefend theregimeagainstthethreatthatdefectionposes – ifnotdirectlytoregime securityitself,tothenarrativeofpaternalprotectionandsuccoruponwhichthe Kimfamilybasesitslegitimacy.

Discrediting:ThePoliticsofDefectorLegitimacy

Otherpropagandaseekstodiscredit – tobothdomesticandinternational audiences – theaccountsofthosewholeaveandofferexperiencesandopinions criticaloftheDPRK.Discreditingisnotalwaysthesolepurposeofthemedia segmentinwhichitoccurs;itissometimesamomentinalargernarrativeof rejectionoflifeinSouthKoreaand(re)-embraceoftheNorth.One2016video ofre-defectorSonOk-Sun,whoreturnedaftersixteenyears,showshertearfully rippingthecoverfromhermemoir.Sheisshownvisitinganamusementpark andpoliticalmonumentsinPyongyang,thenaprimaryschoolwhereshe embraceschildrendressedintraditionalKoreanclothesandspeakspositively oftheegalitarianismandwelfarepoliticsofNorthKorea(Rothwell2016). Ayearlater,statemediafeaturedJeonHye-sung,awomanwho’ddefectedin 2014andappearedonthepopularTVshow MoranbongClub,sayingshe’d beeninstructedtoslanderNorthKoreaduringmediaappearances(Hu2016; GriffithsandKwon2017).Whilethesesegmentsarenotdirectattacksonthe credibilityofothermemoirsorvideoappearances,theysetupapresumption amongtheaudiencethatsuchstoriesareuntrustworthy.

OtherattemptstodiscreditNorthKoreanswho’veleftaremoreovert.For example,oneKCNApiececharacterizedthelandmark2014reportbythe UnitedNationsCommissionofInquiry(UNCOI)onHumanRightsinNorth

Korea,whichwasbasedlargelyondirecttestimonyfromdefectors(see Section5),as “pepperedwithliesandfabrications,deliberatelycookedupby suchriff-raffsasthosewhodefectedfromtheDPRKandcriminalswhoescaped aftercommittingcrimes” (KCNA2014).SimilarlanguageappearsinNorth Korea’scommunicationstotheUnitedNationsandrhetoricinUNfora.A2014 letterfromAmbassadorJaSongNamtotheUNSecurityCouncil,forexample, referredtothe “humanrightsracket” as “hysteriakickedupbythehumanscum who fledtosouthKoreaafterhavingbeenforsakenbytheirkithandkinforall theirevildoingsandvicesperpetratedintheirhometowns. acharadestaged onthebasisofmisinformationprovidedbythem” (Ja2014).Anotherrefersto thereportasbasedon “fabricatedstories” ofcriminals(UNWebTV2014;see alsocommentsbyDPRKrepresentativeKimYongHo,I.R. Kim2016).Atan unusualCouncilonForeignRelationseventin2014,DPRKAmbassadorJang repeatedhisassertionthat “so-calleddefectorsfabricatedtheirstoriestoraiseup thepriceoftheirpresentation” (Jang2014).In2015,aletterfromNorthKorean ForeignMinisterRiSu-yongappearedtorequestnamesofthosewho’dtestified beforetheUNCOI,saying, “wearereadytorevealtothewholeworldthetrue identitiesofeachandeveryoneofthemandthecrimescommittedandthelies toldbythemonebyone” (Anna2015).

OnerevealingexchangeataUNforum,inOctober2014,includedtwoNorth Koreanrefugeeswho’dtestifiedtotheUNCOI.Itrevealsthecentralityof defectorvoicesintworespects – totheCOI’slegitimacy,andtotheDPRK’s effortstounderminethelegitimacyofdefectorspeechandtherebythecredibilityofthereportitself.ADPRKrepresentativesuggestedthattheCommission hadusedtestimony “forcedfromwitnessesbyleadingquestions,” aclaim rebuttedforcefullybytheCommission’schair,AustralianJusticeMichael Kirby.TheDPRKrepresentativearguedthattheCOIreporthad “nolegitimacy” becauseitwas “onlybasedonthetestimonyofthedefectorswhoescapedfrom theNorthaftercommittingcrimes” andthatwitnesseswholeftwereunfair becausetheyheld “inveteratenegativedispositionagainstourpoliticaland socialsystem.” Kirbyrespondedthatallegationsofcriminalitymeanlittle whentheveryactofexitisitselfconsideredacrimebythestate – bydefinition, onecannotleaveNorthKoreaforthesouthandbeanythingelse.TheDPRK representativedidnotaddresstwodirectrequestsfromKirbytoretracthis allegationthatwitnesseswere “humanscum” bribedtoappear(Kirby2014). Kirby’saffirmationofthecredibilityoftheUNCOI’sconclusionsoncrimes againsthumanityreferencedthefactthateveryallegationwassupportedby directevidencefromtestimony,whiletheDPRKrepresentative’sattemptto discreditthereportsuggestedthatwitnessesweresimultaneouslycoerced, dishonest,andbiased.

DPRKstatemediararelyreferstoindi vidualdefectorsbyname,preferringtocollectivelylabelthemwithemotiveepithetssuchas “ humanscum ” or “ humantrash ” ( inkansuraegi )( Fahy2019 ).FromJanuary2014to May2015(thewindowaround/aftertheUNCOIreportrelease),North Koreanmediareferencedhumanrightsaroundathousandtimes,usingthe collectivelabel “ humanscum ” 242times,butonlyreferringtoindividual defectors fi vetimes( Fahy2019 :209 – 211).Afewparticularindividuals, however,arediscreditedbyname,ingreatdepth.NorthKoreahasproduced lengthydocumentaries – oftenwithEnglishsubtitlesandavailablevia Uriminzokkiri,aNorthKorea-af fi liatedpresswebsiteinJapan – onhighpro fi ledefectors,presentingwitnessestotheirdeviouscharactersand supposedlycriminalpasts.Thedocumentariesonlysometimesrefute speci fi callegationsofhumanrightsviolationsmadeindefectortestimony; atothertimes,theyfocusonoverallcharacterdiscreditationinsteadof refutingspeci fi callegations( Fahy2019 :247).

Amongtheregime’stargetshavebeenJeongKwangIl/JungGwangIl,an activistinvolvedinattemptingtosmuggleinformationintoNorthKoreafrom theSouth;ShinDongHyuk,whosestory EscapefromCamp14 wasoneofthe firstdefectormemoirspublishedinEnglish;andYeonmiPark,ayoungfemale defectorwhosevideotestimonyata2014internationalconferencecatapulted hertointernationalcelebrity(Section5).8 OnevideoonShin,forexample, arguesthat “[TheUSandROK]areusingthevicious ‘defectors,’ whoranaway fromtheDPRKtoescapethepunishmentforthecrimestheyhavecommitted, tofabricatethehumanrightssituationoftheDPRKwithpreposterousfalse information.SinTongHyok[sic]isattheforefrontofthisplot” (“Lieand Truth” 2014; Jin2015).Shin’sfatherprovidesalternativeaccountsforthescars onShin’sbody(hotdogfoodspillingontohisback),theoffenseforwhich Shin’smotherandbrotherwereexecuted(murderversuspoliticaloffense),and Shin’sownroleinreportinghisfamily,whileShin’sformerminingcoworker claimshehurthis fingerafterfallingoutsideatnight,andaneighborallegesthat herapedathirteen-year-oldgirl.

InthecasesofShinDongHyukandYeonmiPark,Pyongyangexploited inconsistenciesintheiraccountstoargueforgeneraldiscreditationofdefector testimony,andofanycriticismofNorthKoreathatemploysdefectortestimony

8 Park’sspeech: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ei-gGvLWOZI.Over200memoirsbyindividuals who’veleftNorthKoreahavebeenpublishedinEnglishandKorean;~20areinEnglish, includingthosebyShinDongHyukandYeonmiPark(D.H. Shin2012;Y.M. Park2015).For agraphillustratingthegrowthofthisgenre,see Greitens2021:123.ManyoftheDPRK’svideos arenolongeravailable,asYouTuberemovedUriminzokkiriandseveralotherNorthKoreaaffiliatedaccountsin2016–17.

asevidence.Shin’searlyversionsofhismemoiromittedasecondcampwhere he’dlivedformuchofhislife,describedhisescapetoChinadifferently,andleft outhisownroleintheexecutionofhismotherandbrother.ShintoldBlaine Harden,thejournalistwho’dhelpedhimtellhisstory,thathefoundittoo painfultorecountsomedetails,saying, “Imadeacompromiseinmymind. IalteredsomedetailsthatIthoughtwouldn’tmatter.Ididn’twanttotellexactly whathappenedinordernottorelivethesepainfulmomentsalloveragain” (Harden2015; Rauhala2015).InPark’scase,bothWesternobserversandother defectorsdrewattentiontoinconsistenciesinherstory:thecontrastbetweenthe tearfulstoryofnear-starvationtoldonstageinDublinandherreputationfor arelativelyluxuriouspastlifewhenshe’dappearedontheSouthKorean televisionprogram NowOnMyWayToMeetYou;whathappenedafterher parentswereimprisoned;whosheescapedwith;thenarrativeofherfather ’s death(Jolley2014; Power2014; Vollers2015).NorthKoreaproducedseveral documentariesaccusingherofwritinga “bookoflies,” buildingonthese critiques(Fahy2019:238–241).

Theinconsistenciesmatteredinthepubliccontestforcredibilitybecause thishandfulofdefectorshadbecome,asHardenstatedaboutShin, “ thesingle mostfamouswitnesstoNorthKorea ’scrueltytoitsownpeople. ” Moreover,in Shin’scasethestorychangedmorethanonce;evenHardenreluctantlynoted, “ Shintoldmeheisnowdeterminedtotellthetruth.Regrettably,hehastold methisbefore.Itseemsprudenttoexpectmorerevisions ” (Harden2015 ). Pyongyang ’seffortstodiscreditShinappeartohaveplayedanimportantrole inhisstory ’sgradualexcavation:itwasShin’sfather ’sappearanceinaNorth Koreanvideothatbroughttolightthathe’dlivedmuchofhislifeinCamp18, ratherthanCamp14.(Shin’sfather,inthevideo,deniedlivinginapolitical prisoncampatall,thoughthecityhenameswould ’vebeenwithinCamp18 ’s bordersthen.)Anamplifi cationeffectoccurs:inconsistenciesindefector storiescreateanopeningforDPRKmediatointroduceanalternativenarrative thatamplifi esthoseoriginalinconsistenciesandusesthemtoprovideapicture ofwholesale,irredeemabledeception;theseattacks,inturn,canheighten attentiontotheinconsistenciesamongexternalaudiences,evensympathetic ones.

ThereisnoeasywaytoassesshoweffectiveNorthKorea’seffortsat discreditinghavebeen.Some,includingtheAmericancollaboratorswho helpedbothShinandParktelltheirstoriesinmemoirs,notethatfragmented, incompletenarrativesareamarkofpasttrauma(Harden2015; Vollers2015; Fahy2019).Otherspoint,lesssympathetically,to financialandcelebrityincentivesthatpredisposedefectorstowardsensationalismandexaggeration(Song 2015; SongandDenney2019).As Haggard(2015) writes:

Therearecomplexissueshere,andtheycannotsimplybesweptaside.The integrityofthelegalprocessofwhichtheCOIcouldbeapartrestsonthe testimonyonwhichitdraws.Factscannotbetreatedcasually.Memoryplays tricks,butstoriescanalsogettoldinaparticularwayandembellished:for psychologicalreasons,foropportunisticreasons,orfornoclearreasonsatall.

ButthemostimportantpointisthatthecaseagainstNorthKoreadoesnotrest onthetestimonyofanyoneindividual,butontheaccumulatedevidencefrom avarietyofsources,fromstudiesofthefamineandsurveyofrefugeesweand othershavedone,tosatelliteimagery,tosmuggledvideofootage,totheoverwhelmingweightoftherefugeetestimonyonoffer,nowrunningtohundredswho hadsomeexperiencewiththepenalsystem ... .Thecoreevidenceisstaggering.

JusticeKirby,theCOIChair,arguedforcefullythat “minorretractionsof asingle,highlytraumatizedperson” shouldnotoverturnevidenceprovided byhundredsofwitnessesatCommissionhearings(Haggard2015).Other advocateshavelikewisepointedoutthatchangestodetailsinahandfulofhighprofileaccountsdonotdiscreditthemuchlargerbodyofevidencethatcorroborateshumanrightsabusesonamassivescale(Vollers2015; Rauhala2015). Theirneedtoremindreadersofthisfact,however,reinforcestheimpactthat NorthKorea’sdiscreditingeffortshavehadonglobalconversation.

DeterrenceandDisruption:ThreatsandAssassination

Pyongyangalsousesextraterritorialrepressiontodetermembersofthediaspora fromspeakingabouthumanrightsabusesorengaginginoppositionalactivity fromabroad.Inthis,NorthKoreaisnotalone;otherstatesusetransnational repressiontosilencecriticsandseverconnectionsbetweendissidentsinsideand potentialsupportersoralliesabroad(Tansey2016; Glasius2018; Adamson 2020; Dukalskis2021).

Intargetingthediaspora,NorthKoreaseekstolimitinformationandmoney flowsacrossitsborders,perhapsoutoffearthattherolediasporashaveplayed elsewhere – supportingoppositionandsharinginformationthatcouldcatalyze protest – willrepeatitselfintheDPRK(EsbergandSiegel2022; Nugentand Siegel2023).Pyongyanglimitsreunionsamongfamilymembersseparatedfor decadesbythedivisionofthepeninsula;mailandphonecallsto/fromNorth Koreaareprohibitedorheavilymonitored.From1990to2018,theROK recordedonly11,610casesofletterexchanges;1,755face-to-faceencounters involving3,416Koreansarrangedbycivilgroups;andaround20,000participantsintwenty-onegovernmentsponsoredface-to-facereunions(H.J. Kim 2018);Korean-Americansarestillexcluded.9 Informally,diasporamembers

9 InJuly2021,afteryearsofadvocacybyKorean-Americans,theUSHouseofRepresentatives passedtwomeasures(H.R.826andH.Res.294)thatdirecttheStateDepartmenttoreporton

usebackchannelstocallfamilyandsendremittances(Section4)butrisksvary overtime,andasubstantialcutofremittancemoneygoestobrokersorbribing localofficials(Greitens2019),therebysiphoningoffsomeofitspotentialfor politicalempowerment.

SometimestheNorthKoreanregimeemploysrhetoricalrepression,wherein thestatethreatensdiasporamembersabroadwithviolence(CarterandCarter 2022).Inthedocumentariesdiscussedearlier,forexample,statemediaemploys citizenvoicestoexpressangeranddesiretodoviolencetothoseitaccuses. Shin’suncleandthemotherofthegirlhe’saccusedofrapingexpressadesireto beathimtodeath(“LieandTruth” 2014).10 Thisuseofcitizens’ voices –atechniquethat Fahy(2019:251)referstoas “thestateasventriloquist”–alsoappearsincaseslikethatofJangSongThaek,whoseexecutionwas portrayedbyKCNAasacarrying-outofpopularangerandthirstforretribution (KCNA2013e).Inanotherstatemediaarticle,re-defectorPakJongSuk criticizesbynametwoactivistsinvolvedinsendingleafletsandUSBdrives toNorthKorea,ParkSang-hakandKimHongGwang – theformerofwhom hadbeentargetedforassassinationayearearlier(I.B. Kim2012).

Inothercases,theregime’srepressiveactivitytowardextraterritoriallybased diasporicoppositionoccursincyberspace.High-profile,politicallyactive defectorsarecommonlytargetedbyhackingcampaigns(KimandWeisensee 2021);manyreceivethreateningphonecallsmeanttoscareandintimidate (Jeong2020).In2018,hackersbelievedtobeaffiliatedwithNorthKorea obtainedaddressesandotherinformationonalmost1,000defectorsfrom adatabasemaintainedbytheHanaFoundation,thegovernmentbodyresponsibleforhelpingNorthKoreanstransitiontolifeintheSouth(Jeong2018). DefectorsinSouthKoreahaveallegedthatsomere-defectorsreturnedtoNorth Koreaunderdirectthreatofharmtofamilymemberswhoremain, aphenomenonthatChinascholarsterm “relationalrepression.” Inthewords ofoneNorthKoreandefector-activist, “NorthKoreausedmotherhoodfor apoliticalpurpose” bythreateningamotherwithharmtohersonandhisfamily ifshedidnotrepatriate(Harlan2012).

A finaltoolthatPyongyanghasusedtomanageoppositionabroadisdecapitation,atermusedinsecuritystudiesfortargetedkillingofanorganization’s leaders.Lifeasahigh-rankingofficialisrelativelydangerous inside North Korea,astheKimregimecommonlypurges(sometimesexecutes)officials

effortsto findawayfor100,000Korean-AmericanstoseefamilyinNorthKoreabeforemoreof theoldergenerationpassaway.Atthetimeofwriting,thelegislationisbeforetheSenateForeign RelationsCommittee(Chavez2021).

10 Interestingly,inpartoneofthesamevideo,Shin’sfathernotesthereturnofotherdefectorsto their “homeland,” andasksShintocomehome.

whofallfromfavor(Goldring2021);astringofothershavediedincar accidents(Len2003; Dong-a Ilbo 2013; AP2015; BBC2016) – aperplexing andsuspicion-inducingpatternforacountrywithlittleroadtraffic.ButNorth Korea’shistoryofassassinationeffortsshowsthatitsuseoftargetedpolitical violenceisnotjustaninternalregimesecuritystrategy,butonethat’sbeen projectedextraterritorially.

Someofthebest-knownassassinationattemptsoutsideDPRKterritorywere high-watermarksofinter-KoreantensionduringtheColdWar.In1974,aNorth KoreasympathizerresidinginJapanattemptedtoassassinateROKPresident ParkChungHee,insteadkillingPark’swife,YukYoung-soo(Halloran1974). In1983,DPRKagentsorchestratedabombinginRangoon(Yangon),Burma/ Myanmar,thatmissedthen-presidentChunDooHwanbutkilledseventeen SouthKoreanofficials(BBC1991).Theseincidents,andthebombingof KoreanAirFlight858byNorthKoreanagentsin1987,resultedinNorth Korea’splacementontheUS “StateSponsorsofTerrorism” list.TwolowerprofileeventsoccurredaftertheColdWar,inthemid-1990s:in1996,aSouth KoreandiplomatwasfounddeadinVladivostok(Hockstader1996),andin 1997,twomenshotNorthKoreandefectorLeeHan-younginBundang, asouthernsuburbofSeoul(AFP1997; AP1997).

Afterthat,however,extraterritorialassassinationssubsidedforabout adecade.In2008,aNorthKoreanwomanwasconvictedbyaSouthKorean courtforplanningtoassassinateROKofficialswithpoisonneedles(Windrem etal.2017).InJanuary2010,SouthKoreanpolicearrestedseveralindividuals ostensiblyaffiliatedwiththeDPRK’sGeneralReconnaissanceBureaufor plottingtokillHwangJang-yop,thehighest-rankingindividualevertodefect fromNorthKorea(AlJazeera2010; KoreaTimes2010).InSeptember2011, authoritiesarrestedadefector,AhnHak-young,whoallegedlyplannedto assassinatefellowdefectorandwell-knowndissidentactivistParkSang-hak (theonementionedbyre-defectorsthefollowingsummer)atasubwaystation inSeoulusingapoisonedneedle;aSouthKoreancourtconvictedAhnand sentencedhimtofouryears’ imprisonmentinApril2012(Park2011; Feith 2013; LimandZulawnik2021:120).ThemonthbeforeAhn’sarrest,in August2011,twoKoreanmissionariesworkingontheNorthKorea–China borderwerestabbedwithpoisonedimplementstwodaysapart,oneinDandong onthewesternedgeoftheborder,andtheotherinYanji,capitalofYanbian KoreanAutonomousPrefecture,closetoMt.Paektu(Changbaishanin Chinese).The firstman,PatrickKim,didnotsurvive,butthesecond,Gahng Ho-bin,did(Demick2011a, 2011b;T. Kim2017).Fiveyearslater,pastorHan ChungRyeolwasfounddeadwithknifeandaxewoundsinChangbaicounty, alsoalongtheborder(Choi2016; Ryall2017; Stanton2016).