FOUNDATIONSOF STATISTICALMECHANICS

RomanFrigg

TheLondonSchoolofEconomicsandPoliticalScience

CharlotteWerndl UniversityofSalzburg

ShaftesburyRoad,CambridgeCB28EA,UnitedKingdom OneLibertyPlaza,20thFloor,NewYork,NY10006,USA 477WilliamstownRoad,PortMelbourne,VIC3207,Australia

314–321,3rdFloor,Plot3,SplendorForum,JasolaDistrictCentre, NewDelhi – 110025,India

103PenangRoad,#05–06/07,VisioncrestCommercial,Singapore238467

CambridgeUniversityPressispartofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment, adepartmentoftheUniversityofCambridge.

WesharetheUniversity’smissiontocontributetosocietythroughthepursuitof education,learningandresearchatthehighestinternationallevelsofexcellence.

www.cambridge.org

Informationonthistitle: www.cambridge.org/9781009468237

DOI: 10.1017/9781009022798

©RomanFriggandCharlotteWerndl2023

Thisworkisincopyright.Itissubjecttostatutoryexceptionsandtotheprovisions ofrelevantlicensingagreements;withtheexceptionoftheCreativeCommonsversion thelinkforwhichisprovidedbelow,noreproductionofanypartofthisworkmaytake placewithoutthewrittenpermissionofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment.

Anonlineversionofthisworkispublishedat doi.org/10.1017/9781009022798 under aCreativeCommonsOpenAccesslicenseCC-BY-NC4.0whichpermitsre-use, distributionandreproductioninanymediumfornon-commercialpurposesproviding appropriatecredittotheoriginalworkisgivenandanychangesmadeareindicated. Toviewacopyofthislicensevisit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 Allversionsofthisworkmaycontaincontentreproducedunderlicensefromthird parties.

Permissiontoreproducethisthird-partycontentmustbeobtainedfromthesethird partiesdirectly.

Whencitingthiswork,pleaseincludeareferencetotheDOI 10.1017/9781009022798

Firstpublished2023

AcataloguerecordforthispublicationisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN978-1-009-46823-7Hardback ISBN978-1-009-01649-0Paperback ISSN2632-413X(online) ISSN2632-4121(print)

CambridgeUniversityPress&Assessmenthasnoresponsibilityforthepersistence oraccuracyofURLsforexternalorthird-partyinternetwebsitesreferredtointhis publicationanddoesnotguaranteethatanycontentonsuchwebsitesis,orwill remain,accurateorappropriate.

ElementsinthePhilosophyofPhysics

DOI:10.1017/9781009022798

Firstpublishedonline:December2023

RomanFrigg

TheLondonSchoolofEconomicsandPoliticalScience

CharlotteWerndl UniversityofSalzburg

Authorforcorrespondence: CharlotteWerndl, charlotte.werndl@sbg.ac.at

Abstract: Statisticalmechanicsisthethirdpillarofmodernphysics, nexttoquantumtheoryandrelativitytheory.Itaimstoaccountforthe behaviourofmacroscopicsystemsintermsofthedynamicallawsthat governtheirmicroscopicconstituentsandprobabilisticassumptions aboutthem.InthisElement,theauthorsinvestigatethephilosophical andfoundationalissuesthatariseinSM.Theauthorsintroducethetwo maintheoreticalapproaches,Boltzmannianstatisticalmechanicsand Gibbsianstatisticalmechanics,anddiscusshowtheyconceptualise equilibriumandexplaintheapproachtoit.Indoingso,theauthors examinehowprobabilitiesareintroducedintothetheories,howthey dealwithirreversibility,howtheyunderstandtherelationbetweenthe microandthemacrolevel,andhowthetwoapproachesrelatetoeach other.Throughout,theauthorsalsopinpointopenproblemsthatcan bethesubjectoffutureresearch.ThistitleisalsoavailableasOpen AccessonCambridgeCore.

Keywords: statisticalmechanics,probability,equilibrium,Boltzmann,Gibbs

©RomanFriggandCharlotteWerndl2023

ISBNs:9781009468237(HB),9781009016490(PB),9781009022798(OC)

ISSNs:2632-413X(online),2632-4121(print)

1.1TheAimsofStatisticalMechanics

Statisticalmechanics(SM)isthethirdpillarofmodernphysics,nextto quantumtheoryandrelativitytheory.Itsaimistoaccountforthebehaviour ofmacroscopicsystemsintermsofthedynamicallawsthatgoverntheir microscopicconstituentsandprobabilisticassumptionsaboutthem.Theuse ofprobabilitiesismotivatedbythefactthatsystemsstudiedbySMhave alargenumberofmicroscopicconstituents.ParadigmaticexamplesofsystemsstudiedinSMaregases,liquids,crystals,andmagnets,whichallhave anumberofmicroscopicconstituen tsthatisoftheorderofAvogadro’s number(6.022×1023 ). 1

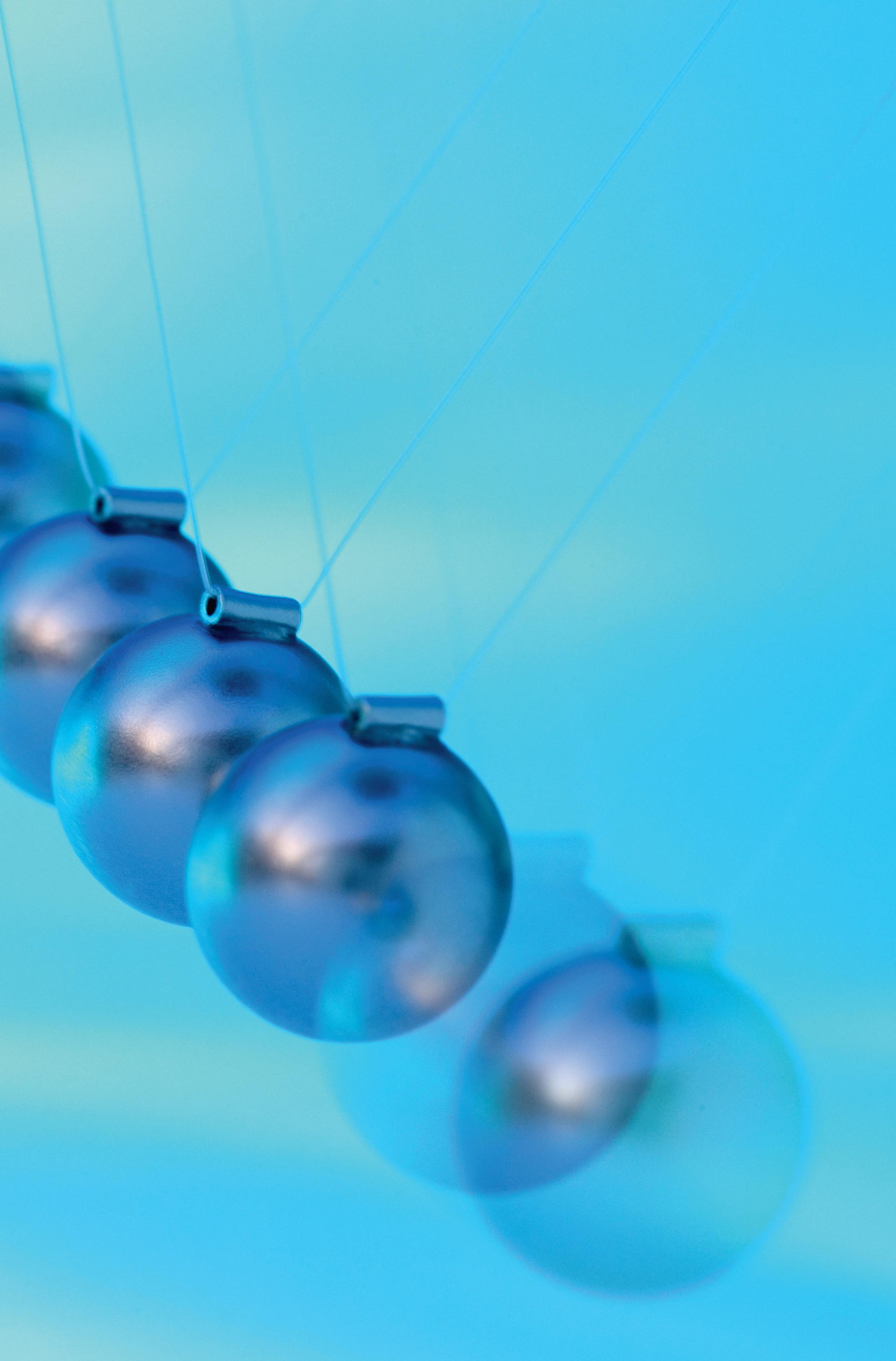

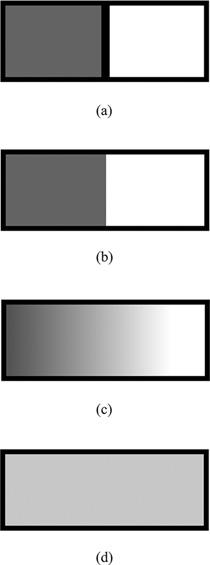

ThefocalpointofSMisaparticularaspectofthebehaviourofmacrosystems,namelyequilibrium.Tointr oduceequilibrium,andtoboostintuitions,letusconsiderastandardexample.Agasisconfi nedtothelefthalfof acontainerwithadividingwall,asillustratedin Figure1a.Thegasisin equilibrium inthesensethatthereisnomanifestchangeinanyofitsmacro propertieslikepressure,temperature,andvolume,andthegaswillhavethese macropropertiessolongasthecontainerremainsunchanged.Nowconsider suchachange:removethedividingwallinthemiddle,asillustratedin Figure1b.Thegasisnownolongerinequilibriumbecauseitdoesnot fi ll thecontainerevenly.Asaresult,thegasstartsspreadingthroughtheentire availablevolume,asillustratedin Figure1c.Thespreadingofthegascomesto anendwhentheentirecontaineris fi lledevenlyandnofurtherchangetakes place,asillustratedin Figure1d .Atthispoint,thegashasreachedanew equilibrium.Sincetheprocessofspreadingculminatesinanewequilibrium, thisprocessisan approachtoequilibrium .Akeycharacteristicofthe approachtoequilibriumisthatitseemstobe irreversible :systemsmove fromnon-equilibriumto equilibrium,butnotviceversa:gasesspreadto fi ll thecontainerevenly,buttheydonotspontaneouslyconcentrateinthelefthalf ofthecontainer.Sinceanirreversibleapproachtoequilibriumisoftenassociatedwiththermodynamics,thisisreferredtoas thermodynamicbehaviour. 2

1 Fromnowon,wewilluse ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ assynonymsfor ‘microscopic’ and ‘macroscopic’ , andwewillspeakofmacrosystemsandtheirmicroconstituents,aswellasofmacroormicro properties,macroormicrocharacterisations,andsoon.Wewillalsouse ‘micro-states ’ and ‘macro-states’,whereweaddthehyphentoindicatethattheyareunbreakabletechnicalterms.We use ‘SMsystems’ asashorthandfor ‘thesystemsstudiedinSM’

2 Thisiscommonlyseenasaresultofthesecondlawofthermodynamics.However,as Brownand Uffink(2001) note,theirreversibilityofthekindillustratedinourexampleisnotpartof thesecondlawandhastobeaddedasanindependentprincipletothetheory,whichtheycall the minus-firstlaw.

Characterisingthestateofequilibriumandaccountingforwhy,andhow, asystemapproachesequilibriumarethecoretasksforSM.Sometimesthese twoproblemsareassignedtoseparatepartsofSM,namely equilibriumSM and non-equilibriumSM.

Whatdoescharacterisingthestateofequilibriuminvolve?Wesaidthatthe gasisinequilibriumwhenthereisnomanifestchangeinanyofitsmacro properties.Thisisavalidmacrocharacterisation.YetiftheaimofSMisto accountforthemacropropertiesofasystemintermsofthebehaviourofits microconstituents,thenweneedacharacterisationofequilibriuminmicrophysicalterms:whatconditiondoesthemotionofthemoleculesinagashaveto satisfyforthegastobeinequilibrium?Andhowdothevaluesofmacroscopic propertieslikelocalpressureandlocaltemperaturedependonthestateof motionofgasmolecules?EquilibriumSMprovidesanswerstotheseandrelated questions.

Turningtonon-equilibrium,thecorequestionishowthetendencyofsystems tomovetoequilibriumwhenpreparedinanon-equilibriumstateisgrounded inthedynamicsofthemicroconstituentsofthesystem:whatisitaboutthe motionsofmoleculesthatleadsthemtospreadsothatthegasassumesanew equilibriumstatewhentheshutterisremoved?And,crucially,whataccounts forthefactthatthereverseprocessdoesnothappen?

Figure1 Thespreadingofgaswhenremovingashutter.

ThisElementfocusesonthesequestions.This,however,isnottosaythatSM dealssolelywithequilibrium.Whileequilibriumoccupiescentrestage,SMalso addressesotherissuessuchasphasetransitions,theentropycostsofcomputation,andtheprocessofmixingsubstances;andinphilosophicalcontextsSM hasbeenemployedtoshedlightonissueslikethedirectionoftimeandthe possibilityofknowledgeaboutthepast.Spaceconstraintspreventusfrom delvingintotheseissues,andwewillconcentrateonequilibrium.

1.2TheTheoreticalLandscapeofSM

Foundationaldebatesinmanyotherareasofphysicscantakeastheirpointof departureagenerallyacceptedformalismandaclearunderstandingofwhatthe theoryis.Adiscussionofthenatureofspaceandtime,forinstance,canbaseits considerationsonthegeneraltheoryofrelativity,andadiscussionofthe foundationsofquantummechanicshastheformalismofthetheoryasreference point.ThesituationinSMisdifferentbecause,unlikequantummechanicsand relativitytheory,SMhasnotyetfoundagenerallyacceptedtheoreticalframework,letaloneacanonicalformulation.ThosedelvingintoSM findamultitude ofdifferentapproachesandschoolsofthought,eachwithitsownconceptual apparatusandformalstructure.3 AdiscussionofthefoundationsofSMcan thereforenotsimplybeginwithaconcisestatementoftheformalismofSM anditsbasicprinciples.Indeed,thechoice,articulation,andjustificationof atheoreticalframeworkforSMisanintegralpartofthefoundationalendeavour! IthasbecomecustomaryinthefoundationsofSMtoorganisemost(although notall)theoreticalapproachesinSMunderoneoftwobroadtheoretical umbrellas.TheseumbrellasareknownasBoltzmannianSM(BSM)and GibbsianSM(GSM)becausetheircoreprinciplesareattributedtoLudwig Boltzmann(1844–1906)andJosiahWillardGibbs(1839–1903)respectively. Accordingly,approachesarethenclassifiedas ‘Boltzmannian’ or ‘Gibbsian’ . 4 InthisElement,wefollowthisclassificatoryconventionanduseittostructure ourdiscussion.Wenote,however,thatfromahistoricalpointofview,this labellingisnotentirelyfelicitous.WhileBoltzmanndidindeedchampionthe approachnowknownasBSM,hisworkwasinnowayrestrictedtoit.

3 Forreviewsoftheseapproachessee Frigg(2008b), Penrose(1970), Shenker(2017a, 2017b), Sklar(1993),and Uffink(2007).

4 Thereisaninterestinghistoricalquestionabouttheoriginandsubsequentevolutionofthis schism.Wecannotdiscussthisquestionhere,butwespeculatethatitgoesbacktoEhrenfest andEhrenfest-Afanassjewa’sseminalreview(1912/1959).WhiletheydonotusethelabelsBSM andGSM,theyclearlyseparateadiscussionofBoltzmann’sideas,whichtheydiscussunderthe headingof ‘TheModernFormulationofStatistico-MechanicalInvestigations’,andGibbs’ contributions,whichtheydiscussinasectionentitled ‘W.Gibbs’s ElementaryPrinciplesin StatisticalMechanics’ .

Boltzmanninfactexploredmanydifferenttheoreticalavenues,amongthem alsoensemblemethodsthatarenowclassifiedasGibbsian.So ‘BSM’ isa neologismthatshouldnotbetakentobeanaccuratereflectionofthescopeof Boltzmann’sownwork.5

1.3Outline

InthisElementwediscusshowBSMandGSMdealwiththequestions introducedin Section1.1.BothBSMandGSMareformulatedagainstthe backgroundofdynamicalsystemstheoryandprobabilitytheory.In Section2 weintroducethebasicconceptsofboththeoriesandstateresultsthatare importantinthecontextofSM.In Section3 weturntoBSM.Westartby introducingthecoreconceptsofBSMandthendiscussdifferentwaysof developingthem. Section4 isdedicatedtoGSM.Afterintroducingtheformalism,wediscussitsinterpretationanddifferentdevelopments,andweendby consideringtherelationbetweenBSMandGSM. Itgoeswithoutsayingthatomissionsareinevitable.Someofthemwehave alreadyannouncedin Section1.1:wefocusonequilibriumandtheapproach toit,andwesetasidetopicslikephasetransitionsandtheentropycostsof computation,andwewillonlybrieflytouchonquestionsconcerning reductionism.6 Inadditiontothese,wesetasideapproachestoSMthatdonot clearlyfallundertheumbrellaofeitherBSMorGSM,whichimpliesthatwedo notdiscusstheBoltzmannequation.7

2MechanicsandProbability

Asthename ‘statisticalmechanics’ indicates,SMaimstogiveanaccountofthe behaviourofsystemsintermsofmechanicsandstatistics.Theuseoftheword ‘statistics’ inthiscontextis,however,outofsyncwithitsmodernuse,wherethe termusuallymeanssomethinglike ‘thetechnologyofextractingmeaningfrom data’ (Hand2008,1).Asabranchoftheoreticalphysics,SMisnotconcerned withthecollectionandinterpretationofdata(althoughdataareofcourse importantintestingthetheory).Inthesecondhalfofthenineteenthcentury, whenthefoundationsofthedisciplinewerelaid,oneofthemainusesofthe term ‘statistics’ wasalsotodesignatea ‘descriptionofthepropertiesorbehaviourofacollectionofmanyatoms,molecules,andsoon,basedontheapplicationofprobabilitytheory’ (OED ‘statistics ’).Soa ‘statistical’ treatmentof

5 ForanoverviewofBoltzmann’scontributionstoSMsee Uffink(2022);fordetaileddiscussions see,forinstance, Brush(1976), Cercignani(1998), Darrigol(2018),and Uffink(2007).

6 Forrecentdiscussionsofreductionwithspecialfocusonstatisticalmechanics,see Batterman (2002), Butterfield(2011a, 2011b), Lavis,Kühn,andFrigg(2021),and Palacios(2022)

7 ForadiscussionoftheBoltzmannequation,see Uffink(2007).

aproblemissimplyatreatmentintermsofprobabilitytheory.Thisuseof ‘statistics’ hasbecomelesscommon,andhence ‘probabilisticmechanics’ might betterdescribethedisciplinetoamodernreader.But,forbetterorworse, historicallabelsstick.Whatthisshortexcursionintotheetymologyof ‘statisticalmechanics’ bringshomeisthatthetheorybuildsontwootherdisciplines, namelymechanicsandprobability,whichprovideitsbackgroundtheories.

Theaimofthissectionistointroducethesebackgroundtheories.The mechanicalbackgroundtheoryagainstwhichSMisformulatedcanbeeither classicalmechanicsorquantummechanics,resultingineitherclassicalSMor quantumSM.Foundationaldebatesarebyandlargeconductedinthecontextof classicalSM.WefollowthispracticeinthisElement,andforthisreasonthe currentsectionfocusesonclassicalmechanics.8

Thesectionisstructuredasfollows.Webeginbyintroducingdynamical systemsatagenerallevel,alongwithsomebasicmechanicalnotionslike trajectory, measure,and determinism (Section2.1).Wethenhaveacloser lookataspecificclassofdynamicalsystems,Hamiltoniansystems,whichare importantinthiscontextbecausetheyprovidethefundamentalstructureofSM systems(Section2.2).Hamiltoniansystemshavetwodynamicalpropertiesthat featureprominentlyindiscussionsaboutSM,namelytime-reversalinvariance (Section2.3)andPoincarérecurrence(Section2.4).Beingergodicisaproperty thatcertaintimeevolutionspossess.Thispropertyplaysanimportantrolein SMbecausedifferentapproachesappealtoittojustifytheequilibriumbehaviourofSMsystems(Section2.5).Thisbringsourdiscussionofmechanicsto aconclusion,andweturntoprobability.Weintroducethebasicformalismof probabilitytheoryanddiscussthethreemainphilosophicalinterpretationsof probability(Section2.6).

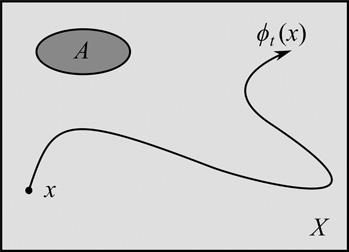

2.1DynamicalSystems

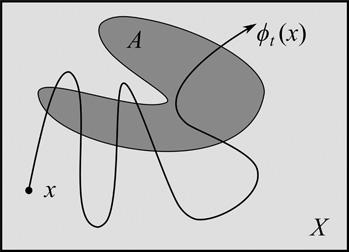

Attheleveloftheirmicroconstituents,SMsystemshavethestructureofaso-called dynamicalsystem,atriple ðX ; t ; μÞ. 9 Thisisillustratedin Figure2.Here, X is the statespace ofthesystem:itcontainsallstatesthat,thesystemcouldpossibly assume.Inclassicalmechanics,thestateofmotionofanobject(understoodasa pointparticle)iscompletelyspecifiedbysayingwhatitspositionandmomentumare.Ifasystemconsistsofseveralobjects,thestateofmotionofthesystem isspecifiedbysayingwhatthepositionsandthemomentaofallitsobjectsare. Moleculesmoveinthree-dimensionalphysicalspace,andsoamoleculehas

8 ForadiscussionoffoundationalissuesinquantumSMsee,forinstance, Emch(2007).

9 Ourcharacterisationofadynamicalsystemisintuitive.Formathematicaldiscussionssee,for instance, ArnoldandAvez(1968) and KatokandHasselblatt(1995).

threedegreesoffreedom.Thismeansthataspecificationofthepositionofthe moleculerequiresthreeparameters,oneforeachspatialdirection.Sincethe moleculehasamomentumineachdirection,afurtherthreeparametersare neededtospecifyitsmomentum.Soweneedsixparameterstospecifythestate ofmotionofamolecule.Accordingly,thespecificationofthestateoftheentire gaswith n moleculesrequires6n parameters.Hence, X isa6n-dimensional spacecontainingthepositionsandmomentaofallmolecules.

Thesecondelementofadynamicalsystem, t ,isthe timeevolutionfunction. Thisfunctionspecifieshowthestateofasystemchangesovertime,andwewrite t ðxÞ todenotethestateintowhichaninitialstate x evolvesaftertime t.Ifthe timeevolutionisspecifiedbyequationsofmotionlikeNewton’s,Lagrange’s,or Hamilton’s,then t ðxÞ isthesolutionofthatequation(wediscussHamilton’s equationsinmoredetailinthe nextsection).Astimepasses, t ðxÞ drawsa ‘line’ through X thatrepresentsthetimeevolutionofasystemthatwasinitiallyin state x;this ‘line’ iscalleda trajectory.Thisisillustratedin Figure1

Thethirdelementofadynamicalsystem, μ,isa measure on X.Atageneral level,ameasureisadevicetoattributeasizetoanobject.Familiarexamplesare theattributionofalengthtoasegmentofaline,asurfacetoapartofaplane,and avolumetoaportionofspace.Fromamathematicalpointofview X isaset,and themeasure μ attributesa ‘size’– or ‘measure’– tosubsetsof X inmuchthe samewayinwhicharulerattributesalengthto,say,apencil.Ifthemeasure μ is abletoattributeasizetoaparticularsubset A ⊆ X ,then A issaidtobe measurable.Inwhatfollowsweassumethatallsetsaremeasurable.If ameasureissuchthat μðX Þ¼ 1,thenthemeasureis normalised. Thingscanbemeasuredindifferentways.Onemeasureisofparticular importanceinthecurrentcontext:theso-called uniformLebesguemeasure. Thismeasureisamathematicallypreciserenderingofthemeasureweusewhen attributinglengthsandsurfacestoobjects.Forinstance,theinterval[2,5]has uniformLebesguemeasure(orlength)3,andacirclewithradius r hasuniform Lebesguemeasure(orsurface)of π r2 .

Figure2 Adynamicalsystemandasubset A ⊆ X

Thetimeevolution t isdeterministic.Itiscommontodefinedeterminismin termsofpossibleworlds(Earman1986,13).Let W betheclassofallphysically possibleworlds.Theworld w 2 W isdeterministicifandonlyiffor any world w ’ 2 W itisthecasethat:if w and w ’ areinthesamestateatsometime t0 ,then theyareinthesamestateat all times t.Thisdefinitioncanberestrictedtoan isolatedsubsystem s of w.Considerthesubsetworld Ws ⊆ W ofallpossible worldswhichcontainanisolatedcounterpartof s,andlet s ’ betheisolated counterpartof s in w ’.Then s isdeterministicifandonlyiffor any world w ’ 2 Ws itisthecasethatif s and s ’ areinthesamestateatsometime t0 ,then theyareinthesamestateat all times t.Thesystem s canbeadynamicalsystem ofthekindwehavejustintroduced.Determinismthenimpliesthateverystate x hasexactlyonepastandexactlyonefuture,or,ingeometricalterms,trajectories cannotintersect(neitherthemselvesnorothertrajectories).

2.2HamiltonianMechanics

Thenotionofadynamicalsystemintroducedinthe previoussection is extremelygeneral,andmorestructuremustbeaddedtomakeitusefulforthe treatmentofSMsystems.Thestructurethatisusuallyaddedisthatof Hamiltonianmechanics.10

InHamiltonianmechanics,thestateofanobjectisdescribedbyitsposition q anditsmomentum p.Infact,thereisa q-and-p pairforeverydegreeof freedom.Hence,foragaswith n moleculesmovinginthethree-dimensional physicalspacethereare3nq-and-p pairs.The3n pairsconstitutethestatespace X ofthesystem,whichinthiscontextisoftenreferredtoas phasespace (and sincehaving3n pairsmeanshaving6n variables,thephasespacehas 6n dimensionsasnotedpreviously).

TheHamiltonianequationsofmotionare

wherethedotindicatesaderivativewithrespecttotimeandtheindex k ranges overalldegreesoffreedom(so,foragaswehave k= 1, ...,3n).Thisdefines asystemof k differentialequations,andthesolutiontothisequationisthetime evolutionfunction t ofthesystem.SolvingtheseequationsforSMsystemsis usuallyapracticalimpossibility,andsowewillnotbeabletowritedown t explicitly.ThisdoesnotrenderHamiltonianmechanicsuseless.Infact,the equationsensurethat t hasanumberofgeneralfeatures,andthesecanbe

establishedevenif t isnotexplicitlyknown.Intheremainderofthissectionwe reviewsomeofthefeaturesthatarecentraltoSM.

TheHamiltonianequationscontainthefunction H,whichiscalledthe Hamiltonian ofthesystem.TheHamiltonian H istheenergyfunctionof thesystem,which,ingeneral,dependsonallcoordinates qk and pk .So,the Hamiltonianequationsofmotionspecifyhowasystemevolvesintimebasedon theenergyfunctionofthesystem.Iftheenergyofthesystemdoesnotexplicitly dependontime(whichisthecase,forinstance,ifasystemisnotdrivenby outsideinfluenceslikepushesorkicks),thenthesystemis autonomous.Inan autonomoussystem, H isaconservedquantity(ora ‘constantofmotion’), meaningthatitdoesnotchangeoverthecourseoftime.Thishastheimmediate consequencethatanyfunction f ðH Þ isaconservedquantitytoo.

Thegasthatweusedasourintroductoryexampleisanautonomoussystem:it isisolatedfromtheenvironmentthroughtheboxandoncetheshutterhasbeen removed,itisnotsubjecttoanyoutsidedisturbances.Thegasisnoexception, andtypicalsystemsinSMareautonomousHamiltoniansystems.Thefactthat theenergyisconservedhasanimportantconsequence.Oncetheenergyofthe systemis fixedtohaveacertainvalue E,theconservationofenergymeansthat H ¼ E mustholdallthetime. H isafunctionofthecoordinates qk and pk ,which meansthatitdefinesahypersurface XE in X.Thissurfacehasonedimension fewerthan X itself.Inthecaseofthegas,itistherefore6n – 1dimensional.This surfaceisknownasthe energyhypersurface. 11 Since H ¼ E holdsatalltimes,it followsthatthemotionofthesystemisconfinedtotheenergyhypersurface: trajectoriesthatstartinaninitialcondition x intheenergyhypersurfacewill neverleavethehypersurface.

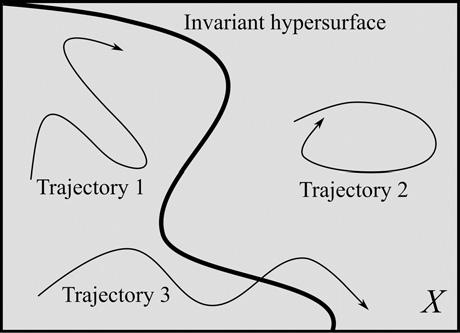

Thetotalenergyofthesystemmaynotbetheonlyconservedquantity. Dependingonthenatureofthesystem,otherquantitiesmaybeconserved too.Fromaformalpointofview,eachconservedquantityisafunction Q of thecoordinates qk and pk forwhich Q ¼ C holdsforalltimes,where C isthe valuethat Q assumes.Ingeometricterms,eachconservedquantitydefines ahypersurfacetowhichtrajectoriesremainconfined.Suchsurfacesarealso called invarianthypersurfaces.Thecrucialaspect(andthiswillbeimportant lateron)isthatthesehypersurfacesdividethephasespaceintoregionsthatare ‘disconnected’ inthesensethattrajectoriescannotpenetratethesurfacetogetto theotherside.Thisisschematicallyillustratedin Figure3,whereweseean invariantsurfaceandthreetrajectories.WhileTrajectory1andTrajectory2are

11 Itisa hypersurfacebecause ‘surface’ hastheconnotationofbeingtwo-dimensional,like atabletop,whichthesurfaceofconstantenergyisnot.

possible,Trajectory3isimpossiblebecausenotrajectorycancrossaninvariant hypersurface.So,invarianthypersurfacesdividethestatespace X intosectors thataremappedontothemselvesunderthedynamics.

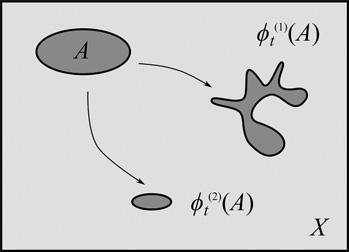

AutonomousHamiltoniansystemshaveanimportantfeaturethatisrelatedtothe thirdelementofadynamicalsystem,themeasure μ.Aswehaveseeninthe previoussection,ameasureallowsustoattributea ‘size’ or ‘measure’ toapart ofthestatespacesuchastheblob A shownin Figure2.Ablobultimately consistsofpointsand,aswehaveseen,pointslieontrajectories:apoint x evolvesinto t ðxÞ astimeevolves.Thismeansthattheevolutionoftheblob aswholeisdeterminedbytheevolutionofitsconstituentpoints.Wewrite t ðAÞ todenotethetime-evolvedblob.Wecannowask how ablobevolves.Oneofthe mostimportantquestionstoaskabouttheevolutionofblobsiswhathappenstotheir measure.Theinitialmeasureoftheblobis μðAÞ,andthemeasureofthetimeevolvedblobis μð t ðAÞÞ.Howdothesecompare?Ifthesetwoareidentical –namely μðAÞ¼ μð t ðAÞÞ – forallblobs A ⊆ X andalltimes t,then t is measurepreserving.AnimportantresultinHamiltonianmechanics,knownas Liouville’stheorem,saysthatany t thatisthesolutionoftheHamiltonian equationsofmotionismeasurepreserving.Thismeansthatifasystemis governedbytheHamiltonianequations,ablobcanchangeitsshapebutnot itssize.Thisisillustratedin Figure4,whichshowshow A evolvesundertwo differenttimeevolutionfunctions, ð1Þ t and ð2Þ t .Underthe firstfunction, A evolvesinto ð1Þ t ðAÞ,whichdoesnothavethesameshapeas A butisofthe samesize.ThiskindofevolutionisallowedundertheHamiltonianequationsof motion.Underthesecondfunction, A evolvesinto ð2Þ t ðAÞ,whichissmaller than A.ThisisruledoutbytheHamiltonianequations,andafunctionlike ð2Þ t couldnotbeasolutionoftheequations.Itisimportanttopointoutthatthis featureisspecifictotheHamiltonianequations.Farfromruledoutingeneral,

Figure3 Invariantsurface.

Twodifferenttimeevolutionfunctionsactingon A

evolutionslike ð2Þ t arecommoninothercontexts,andtheyareallowed,for instance,iftheguidingequationisNewton’sratherthanHamilton’s.

Beforemovingon,webrieflynotethateventhoughHamiltonianmechanicsis assumedtobethefundamentaltheoryofSMsystems,inpracticalcalculations otherdynamicallawsaresometimesconsidered.TypicalexamplesaretheKacring orthebaker ’sgas. 12 Thesedynamicallawsaretypicallychosenfortworeasons: theyaresimpleandcanbeimplementedrelativelyeasilyoncomputers,andyet theyshareimportantfeatureswiththefullHamiltoniandynamics,mostnotably measurepreservation.So,evenwhenconsiderationsaremadewithalternative dynamicallaws,Hamiltonianmechanicsinformsandguidesthechoice.

2.3Time-ReversalInvariance

AnimportantaspectofHamiltoniandynamicsistime-reversalinvariance.13 To introducetheconcept,imagineyouarewatchingamovieshowingaball movinghorizontallyfromthelefttotheright.Intuitively,reversingthetime oftheprocessamountstoplayingthemoviebackward,whichresultsinyou seeingaballmovinghorizontallyfromtherighttotheleft.Assumenowthatthe movingballsaregovernedbyatheory T,whichregulateswhichprocessesare allowedandwhicharebanned.Theory T istime-reversalinvariantifandonlyif for every processthatisallowedbythetheory,itstimereverseisallowedtoo.14 Togiveaprecisestatementofthisidea,weneedtwothings.The firstis atime-reversaltransformation t → t .Thesecondisthereversalofaninstantaneousstateofasystem.Consideragainourball.Itsstateisgivenbythe

12 ForadiscussionoftheKacring,see Jebeile(2020);forthebaker ’sgas,see Lavis(2008).

13 InwhatfollowswerestrictattentiontoautonomousHamiltoniansystems.

14 Notethattime-reversalinvariancedoes not implythatprocessesmustbesuchthattheylookthe sameinbothtemporaldirections:processesdonothavetobepalindromic.Inourexample,you seeaballmovingfromlefttorightinonetemporaldirectionandfromrighttoleftintheother. Fordetaileddiscussionsoftime-reversalinvariancesee,forinstance, Roberts(2022) and Uffink (2001).

Figure4

coordinates q and p.Whenwestopthemovieandstartplayingitbackwards,the positionoftheballremainsunchanged,butitsmomentum flipsfrom p to p So,thetime-reversedstateof ðq; pÞ is ðq; pÞ.Hence,performingaso-called time-reversaltransformationamountstoreplacing t by t and p by p

InHamiltonianmechanicstheverdictonwhetheraprocessisallowediscast bytheHamiltonianequationsofmotion:ifaprocesssatisfiestheequations,itis allowed,andifnot,itisruledout.So,letusseehowtheHamiltonianequations behaveunderatime-reversaltransformation.Someelementaryalgebraic manipulationsshowthattheequationsareleftunchangedifyoureplace t by t and p by p.Thismeansthatprocessesunfoldingbackwardintimeare governedbythesameequationasthoseunfoldingforwardintime,andthis meansthatthetheory – theHamiltonianequations – castthesameverdictabout whatisallowedinbothdirectionsoftime.Hence,Hamiltonianmechanicsis time-reversalinvariant.Thismeansthatifaprocessfromaninitialstate ðqi ; pi Þ toa finalstate ðqf ; pf Þ duringtimespan Δt isallowed,thenaprocessstartingin state ðqf ; pf Þ andendingin ðqi ; pi Þ duringtimespan Δt isallowedtoo.Aswe willsee,thisisthecrucialformalingredientofwhatisnowknownas Loschmidt’sreversibilityobjection.

2.4PoincaréRecurrence

HowdoHamiltoniansystemsbehaveinthelongrun?Withaneyeonirreversibility,onemighthopethatSMsystemswillbesuchthattheystartinonepartof X andthenendupinanotherpartof X.Poincaré’sso-called recurrencetheorem establishesthatthiscannotbe.Considerasystemwithastatespaceof finite measure(μðX Þ < ∞)andwithadynamicsthatismeasurepreservingandmaps thestatespaceontoitself( t ðX Þ¼ X forall t).Thetheoremthensaysthatfor anyset A ⊆ X of finitemeasure(μðAÞ > 0)itisthecasethatalmosteverypoint x in A willreturnto A infinitelymanytimesas t → ∞.Theset A canbechosento beanarbitrarilysmallareaaroundaninitialcondition x.Thetheoremthensays thatforalmostallinitialconditions,thesystemwillreturnarbitrarilyclosetothe initialconditioninfinitelymanytimes.Thetimethatittakesthesystemtoreturn closetoitsinitialconditioniscalledthe recurrencetime. 15

TheHamiltoniansystemsthatareofinterestinSMsatisfytherequirements ofthetheorem:theyaremeasurepreserving(aswehaveseen),andsincethey have finiteenergyandareboundedinspace(theyarethingslikevesselsfullof gas),theaccessibleregionofthestatespaceisbounded.Wecanthen ‘throw away’ theregionsofthestatespacethatthesystemcannotaccessandassociate X withtheaccessibleregion,whichis finite.Hence,SMsystemsshowPoincaré

15 ForadiscussionofPoincarérecurrence,see,forinstance, Cornfeld,Fomin,andSinai(1982).

recurrence.Aswewillsee,thisisthemathematicalbackboneofwhatisnow knownasZermelo’srecurrenceobjection.

2.5Ergodicity

Amongthemanypropertiesthatatimeevolutioncanhave,ergodicityisof particularimportancebecauseitplaysacrucialroleindiscussionsofbothBSM andGSM.16 Considerafunction f : X → ℂ,where ‘ℂ’ denotesthecomplex numbers.Sometimessuchafunctioniscalleda ‘phasefunction’ becauseinthe contextofHamiltonianmechanics X isalsoreferredtoasthephasespace (Section2.2).The spaceaverage f of f (sometimesalsocalled ‘phaseaverage’ , forthesamereasons)is

The timeaverageofthesamefunctionis

where x istheinitialconditionofthetrajectoryattheinitialtime t0 .Itis importanttonotethatthetimeaveragedependsontheinitialconditionand can,inprinciple,bedifferentfordifferentinitialconditions.Intuitively,the spaceaveragegivesusinformationaboutthemeandistributionoverspace.If, forinstance,avillageoccupiesanareaof3squarekilometres,andthereare100, 300,and800dwellersinthe first,second,andthirdsquarekilometrerespectively,thentheaveragepopulationpersquarekilometreis400.Thetimeaverage givesusinformationaboutthedistributionovertime.Considerthe firstsquare kilometreofourvillageandtraceitspopulationovertime.You findthatithad 50dwellersfrom1800to1900and100dwellersfrom1900to2000.Thetime averageofthepopulationinthe firstsquarekilometreovertheperiodfrom1800 to2000isthen75.

Theso-called Birkhofftheorem statesthat f ðxÞ existsforalmostallinitial conditionsanddoesnotdependon t0 (butmaywelldependon x).Thequalification ‘almostall’ meansallexcept,perhaps,forasetofmeasurezero. Intuitively,measurezerosetsaresmall:apointinanintervalhasmeasure zero,andsodoesalinewithinaplane.Withthisresultinthebackground,we canstatethedefinitionofergodicity:adynamicalsystemisergodicifandonlyif

16 Forrigorousdiscussionsofergodicityandergodictheory,see,forinstance, ArnoldandAvez (1968), Cornfeld,Fomin,andSinai(1982),and Petersen(1983).

f ðxÞ¼ f foralmostall x.Aswewillsee,ergodicityisanon-trivialproperty andmanysystems – alsoHamiltoniansystems – arenotergodic.

Withoutlossofgenerality,wenowassumethatthemeasureis normalised, thatis: μðX Þ¼ 1.17 Twoconsequencesofergodicityareworthemphasising becausebothplaycentralrolesinSM.The firstconsequencetranspiresifwe choose f tobetheso-called characteristicfunction ofaset A in X:thefunction assumesvalueonefor x thatarein A andzerofor x outside A.Thespaceaverage forthisfunctionisthensimplythemeasureof A,andthetimeaverageisthe fractionoftimethatthesystemspendsin A inthelongrun.Ifthesystemis ergodic,itfollowsthatforanyarea A in X,thefractionoftimethesystemspends in A isequaltothemeasureof A.Thisisillustratedin Figure5.If,forinstance, A takesupaquarterof X,thenthesystemwillspendaquarterofitstimein A in thelongrun,andthisisthecaseforalmostallinitialconditions.

Thesecondconsequenceisthatsincetheprecedingholdsforany A in X,there cannotbeapart B ofthestatespace(with μðBÞ > 0)thatthesystemdoesnot visit.Aswehaveseenin Section2.2,ifasystemhasinvarianthypersurfaces, thesedividethestatespaceintodisconnectedareas.Thisisincompatiblewith ergodicity,andsoitfollowsimmediatelythatanergodicsystemmustnothave invarianthypersurfaces.Thisissometimesexpressedbysayingthatergodic systemsare ‘indecomposable’ or ‘metricallytransitive’ . Animportantquestionconcernsthespaceonwhichasystemisergodic.So farwehaveformulatedeverythingintermsof X,thestatespaceofthesystem. Thisisachoiceofconvenience.Aswehaveseen,anautonomousHamiltonian systemalwayshasatleastoneconservedquantity,namelytheenergyofthe system,andsoitsmotionisalwaysconfinedtotheenergyhypersurface XE

17 Wecandothiswithoutlossofgeneralitybecause,aswehaveseen,SMsystemshavea finite phasespaceandonecanthenalwayschoosethemeasuresothattheentirespacehasmeasure one.

Figure5 Ergodicity.

Hence,aHamiltoniansystemcannotpossiblybeergodicon X.This,however, doesnotprecludeitfrompotentiallybeingergodicon XE ,or,indeed,asubspace of XE .CrucialdiscussionsinSMrevolvearoundexactlythisissue:whetherthe systemisergodicon XE orarelevantsubspaceofit.

Asnoted,manysystemsarenotergodic,notevenwhenrestrictingconsiderationtotheenergyhypersurface XE .Butnowthereisasurprisingresult.An ergodicdecomposition ofasystemisapartitionofthestatespaceintodifferent partssothatthepartsareinvariantunderthedynamics(i.e.aremappedonto themselvesunder t )andthat,forallparts(ofwhichtherecanbea finiteoran infinitenumber),thedynamicswithinthepartisergodic.The ergodicdecompositiontheorem makesthe – intuitivelysurprising – statementthatsuch adecompositionexistsfor every measure-preservingdynamicalsystemwith anormalisedmeasure,andthatthedecompositionisunique.Inotherwords,the dynamicsofasystemcanbeascomplexaswelikeandtheinteractionsbetween theconstituentsofthesystemcanbeasstrongandintricateaswelike,andyet thereexistsauniqueergodicdecompositionofthestatespaceofthesystem.We willcomebacktothisresultlaterintheElement.

2.6ProbabilityTheory

Probabilityisafamiliarconcept.Weconsidertheprobabilityofrainbefore goingout,orweconsidertheprobabilityofgettingthenumberthreewhen throwingadie.Aswewillsee,inthecontextofSMweareinterestedinthe probabilityofasystemapproachingequilibrium,theprobabilityofentropy increasing,andtheprobabilityof findingthesysteminacertainstate.The theoryofprobabilitycanbedividedintotwoparts.The firstpart,theformal theoryofprobability,developsthemathematicalapparatusofprobability. Thesecondpart,theinterpretationofprobability,isconcernedwithhowthe formalapparatusofthemathematicaltheoryrelatestotherealworld.

Letusbeginwiththe formaltheoryofprobability.An eventspace Ω isthe spaceofallpossibleevents(thisisalsoknownasthe outcomespace).Theevents in Ω aremutuallyexclusive.Intuitively,thisspacecontainsallbasiceventsthat canhappen.Inthecaseofthequestionofwhetheritwillrain,thespacecontains thetwoelements, ‘rain’ and ‘norain’,andinthecaseofadieithassixelements, thenumbersone,two,three,four, five,andsix.Fromaformalpointofview Ω is aset,andsotheeventspaceforthedieistheset{1,2,3,4,5,6}.Butwemaynot onlybeinterestedinbasicevents.Whenthrowingadie,forinstance,wemaynot onlybeinterestedingetting,say,thenumberthree,butalsoineventslikegetting anevennumberorgettinganumbersmallerthanfour.Sucheventsareassociated withsubsetsof Ω:gettinganevennumberisassociatedwiththesubset{2,4,6}

andgettinganumbersmallerthanfourwith{1,2,3}.Wecannowalsoformaset ofsubsets.Forinstance,wecanconstructthesetconsistingofthesets{2,4,6} and{1,2}:{{2,4,6},{1,2}}.Let Σ beasetofsubsetsof Ω.Theset Σ is a sigma-algebra ifandonlyifitsatisfiesthefollowingconditions: Ω isan elementof Σ ;if s isanelementof Σ ,thenalso Ωnsiselementof Σ (where ‘Ωns’ denotesthecomplementof s withrespectto Ω);andeverycountable unionofsubsetsof Ω isin Σ .A probabilitymeasure thenisafunction p : Σ → ½0; 1 suchthat pðΩÞ¼ 1and pðs1 ∪ s2 Þ¼ pðs1 Þþ pðs2 Þ forall mutuallyexclusiveevents s1 and s2 in Σ ,where ‘ ∪ ’ denotesthesetunion. Or,moreintuitively,aprobabilitymeasureisafunctionthatassignseveryevent (basicandnon-basic)anumberbetweenzeroandone,andthisnumberthenis theprobabilityoftheevent.18 Thetriple(Ω; Σ; p)iscalleda probabilityspace. Theprobabilityof s1 conditionalon s2 is pðs1 js2 Þ¼ pðs1 ∩ s2 Þ=pðs2 Þ provided that pðs2 Þ > 0,where ‘ ∩ ’ denotesthesetintersection.

Theprobabilityspaceofadieisrelativelysimple.Notallprobabilityspaces arelikethis.Somesituationsaresuchthattheeventspaceiscontinuous.Asan example,consideradartboard.Inprinciple,adartcanhitanypointofthe dartboard.So,theeventspaceistheentirediskthatconstitutesthedartboard, whichhasanuncountableinfinityofpoints.Insuchcases,theprobability measureisdefinedbyanormalisedfunction ρ ontheeventspaceviathe followingequation:

where R isasubsetof Ω: Thefunction ρ iscalleda probabilitydensity.The conditionthat ρ benormalisedmeansthat

Ineffectthisisjustthe ‘continuousversion’ oftheconditionthatprobabilities adduptoone.

Letusnowverybrieflyturntothesecondpart,theinterpretationof probability.19 Aninterpretationofprobabilityspecifiesthemeaningofprobabilitystatements.Interpretationsofprobabilityfallintotwogroups:objective

18 Theseconditionsareknownasthe axiomsofprobability.Whatwehavepresentedhereisthe standardaxiomatisationofprobability.Therearealternativeaxiomatisations.Nothinginwhat followsdependsonwhichaxiomswechoose.Foradiscussionofalternativeaxiomatisations,see Lyon(2016).Foranin-depthdiscussionoftheformaltheoryofprobability,see,forinstance, Fine(1973)

19 Weherelargelyfollow Hájek’s(2019)classificationofinterpretationsbutconcentrateon accountsthatare,atleastinprinciple,candidatesfortheinterpretationofSMprobabilities.

pðRÞ¼ ðR ρ dω;

ðΩ ρ dω

andsubjective.Objectiveinterpretationstakeprobabilisticstatementsto describeobjectivefeaturesoftheworld.If,say,theprobabilityofobtaining numberthreewhenthrowingadieissaidtobe1/6,thenanobjectivistseesthis asbeingastatementoffact.Subjectivists,bycontrast,seeprobabilities as credences.Acredenceisadegreeofbeliefthatanagenthas(oroughtto have)intheoccurrenceofacertainevent.

Theforemostquestionfortheobjectivistis:whatfactsintheworlddo probabilitiesdescribe?Thetwomostcommonanswerstothisquestionare relativefrequenciesandpropensities. Frequentism interpretsprobabilitiesas frequenciesthatarecalculatedinasequenceofeventsofthesamekind. Frequenciestherebyprovideastatisticalsummaryofthedistributionofcertain featuresinthatsequence.Forafrequentist,thestatementthattheprobabilityfor numberthreeis1/6simplymeansthatinasequenceofthrowsofadie,number threehascomeupin1/6thofthecases.Frequentismcomesindifferentversions, themostimportantdivisionbeingbetween finiteandinfinitefrequentism. Infinitefrequentism,mostprominentlydevelopedbyvonMises,interprets probabilitiesaslimitingrelativefrequenciesofeventsinsequencesextended toinfinity.Finitefrequentisminsiststhatintherealworldweneverhaveinfinite sequencesofeventsandhenceinterpretsprobabilitiesintermsofrelative frequenciesin finitesequences.Oneofthemainproblemsof finitefrequentism isthatonecannotruleoutthatonegetsan ‘atypical’ sequenceofevents(you may getthenumberthreeahundredtimesinaseriesofahundredthrows).Socalled Humeanbestsystems accountsaddressthisproblembyrequiringthat probabilitiesarenotdeterminedby finitefrequenciesalone;theyalsohavetobe consequencesofasystemoflawsthatstrikesthebestbalancebetweenthe theoreticalvirtuesofsimplicity,strength,and fit.Theserequirementsallowthe accounttoruleout ‘atypical’ resultsonthegroundsofoveralltheoretical considerations.

Thesecondcommonobjectivistinterpretationtakesprobabilitiestobe propensities thatareinherentinobjects.Propensitiesaredispositionsortendencies orpowerstoyieldanoutcome,andthestrengthofthepropensityisdescribed (orquantified)bytheprobability.Onthisinterpretation,thereisatendency inherentinthedietoproducethenumberthree,andthistendencyhasstrength 1/6.Differentversionsoftheinterpretationdifferinwhataccountofpowers theygive,andalargearrayofoptionsisavailable.Aproblemthatallpropensity accountshaveisthattheydonotseemtobecompatiblewithdeterminism: eitherprocessesarefundamentallydrivenby ‘chancy’ powers,ortheyare

Whatfollowsisonlythebriefestofsketches.Extendeddiscussioncanbefoundin Galavotti (2005) and Gillies(2000);foradiscussionofBestSystemsaccounts,see Hoefer(2019).

deterministic,butnotboth.20 ThisisobviouslyaprobleminthecontextofSM, where,aswehaveseen,theunderlyingdynamicsisdeterministic.

Subjectivists,alsoknownasBayesians,thinkthatbothfrequentismandthe propensityinterpretationsgotstartedonthewrongfootbecauseprobabilities arenotdescriptionsoffactbutratherdescriptionsofthestateofmindofan agent.Theprobabilitiesweattachtooutcomescodifythedegreeofbelief,or credence,thatanagenthasaboutacertainoutcome.Toasubjectivist,the statementthattheprobabilityforthenumberthreeis1/6meansthatanagent’s degreeofbeliefthatthenumberthreewillappearis1/6.Subjectivistsfallinto twogroups. PersonalistBayesians holdthatprobabilitiesarenothingoverand abovethecredencesofsuitableagents,anditisthenperfectlyconceivablethat twoagentsdisagreeontheirprobabilityassignments.Thisiswhat objective Bayesians reject.21 Theyinsistthatwhileprobabilitiesaredegreesofbelief, probabilitiescannotvaryacrossrationalagentsandareuniquelydetermined bytheavailableevidenceandobjectivemethodsofdeterminingprobabilities. Amongthosemethods,themaximumentropyprincipleplaysanimportant role.Theprinciplesaysthatinasituationoflackofknowledge,or ignorance , arationalagentshouldsettheircredencessothattheentropyoftheirprobabilitydistributionismaximal.Wewillencounterthisprincipleagainin Section4.7.

2.7PointsofContact

Lookingbackatthesubsectionsinthissection,thereadermaybeleft undertheimpressionthatmechanicsandprobabilitytheoryarewholly differentandunrelatedsubjectmatters.Thereisagrainoftruthinthis:the twotheorieshavedevelopedautonomously,andtheycanbe(andare) practicedindependentlyfromeachother.However,thetwotheoriesmake contactattwopoints.The firstpointofcontactisthefactthatthestate space X ofadynamicalsystemcanberegardedastheeventspace Ω of aprobabilityspace,andsubsetsof X canformitssigmaalgebra Σ.Indeed, thisthestandardmoveinSM,wheretheeventsofinterestareeventsinthestate spacesuchas ‘thesystemisinstate x ’ or ‘thestateofthesystemliesinblob A’ . Thesecondpointofcontactisthemeasure μ.In Section2.5 wenotedthatthe measurecanbenormalisedwithoutlossofgenerality.Butanormalisedmeasure hasthemathematicalstructureofaprobability.Itisthereforenocoincidence thatinSM μ isoftenusedtoprovideprobabilitiesofevents.Hence,despite

20 Foradiscussionofchanceanddeterminism,see Frigg(2016).

21 Thelabel ‘objectiveBayesian’ issomewhatunfortunatebecausethisisobviouslynotan objectiveinterpretationinthesenseinwhichfrequenciesandpropensitiesare.

beingdifferenttheories,theassociationsof X with Ω andof μ with p provide astrongbridgebetweenthetwotheories.Indeed,muchofSMcanbeseenasthe attempttoarticulatetheexactnatureofthisbridgeandtoshowhowitworks. Themainchallengeinthisendeavouristhehandlingofthetimeevolution function t .Notonlydoesthisfunctionhaveno ‘cousin’ inprobabilitytheory;it infactseemstoconflictwithprobabilitytheoryinthatitintroducesstructures liketrajectoriesandinvariantsurfaceson X thatareforeigntoprobability theory,wherethereisnodynamicson Ω.Asaresult,amajorchallengefor SMisto ‘harmonise’ thewayprobabilitiesareintroducedwiththedynamicsof thesystem.Aswewillsee,differentapproachesdothisindifferentways.

3BoltzmannianStatisticalMechanics

IncurrentdebatesaboutSM, ‘ BSM’ denotesafamilyofpositionsthattake astheirstartingpointtheapproachthatwas fi rstintroducedbyBoltzmann inhis( 1877 )andthenpresentedinastreamlinedformbyEhrenfestand Ehrenfest-Afanassjewaintheir(1912/ 1959 ).Inthissectionwediscuss differentcontemporaryarticulationsofBSMalongwiththechallenges theyface.

Thesectionisstructuredasfollows.Webeginbyintroducingthebasic structureofBSMthatallpositionsthatidentifyas ‘Boltzmannian’ share (Section3.1).WethendiscussBoltzmann’scombinatorialargument,whichis thecanonicalmethodtoconstructmacro-statesandtoidentifyequilibrium (Section3.2).Thismethodisoftencombinedwithanexplanationofthe approachtoequilibriumbasedonergodicity(Section3.3).Anyexplanationof theapproachtoequilibriumfacestwoimmediateobjections:Loschmidt’s objectionbasedontime-reversalinvarianceandZermelo’sobjectionbasedon Poincarérecurrence(Section3.4).Thepackageofthecombinatorialargument andergodicityfacesanumberofdifficulties,whichareresolvedinthe ResidenceTimeaccount(Section3.5).Analternativeaccountaimstoexplain theapproachtoequilibriumintermsoftypicality(Section3.6).Probabilities haveplayednoroleinthedevelopmentofBSMuptothispoint,andwenow reviewdifferentwaysofintroducingprobabilitiesintothetheory(Section3.7). TheMentaculusisadistinctivewayofresolvingsomeoftheissuesthatarisein BSM,whichhasatitscoretheuseofconditionalprobabilitiescombinedwith whathasbecomeknownasthePastHypothesis(Section3.8).Despiteits appeal,theframeworkofBSMfacesanumberofproblemsandlimitations (Section3.9).

3.1TheBareBonesofBSM

AllpositionsthatgatherundertheumbrellaofBSMshareatheoreticalcore,and differentversionsofBSMvaryinhowtheydevelopthiscoreandinwhatthey addtoit.Inthissectionweintroducethiscore.22

BoltzmannianSMdistinguishesbetweenmicro-statesandmacro-states.The micro-state ofasystemspecifiestheexactmechanicalstateofeverymicroconstituentofthesystem.Aswehaveseenin Section2.1,thesystem’sstate space X consistsofallstatesthatthesystemcouldassume.Sothesystem’s micro-stateattime t issimplythestate x 2 X inwhichthesystemisattime t. Intuitively,the macro-stateM ofasystemspecifiesthemacro-constitutionof thesystemintermsofvariableslikevolume,localpressure,localtemperature, andotherpropertiesthatareobservable,looselyspeaking,atahumanscale.The configurationsshownin Figure1 aremacro-statesinthissense.Itisnotobvious howtocharacterisemacro-statesprecisely,andwewillcomebacktothis problemin Section3.9.Fornow,weoperatewithanintuitivenotionofmacrostates.

ThecorepositofBSMisthatmacro-statessuperveneonmicro-states. Considertwosetsofproperties, A and B Asupervenes on B ifandonlyiftwo thingscannotdifferintheir A-propertieswithoutalsodifferingintheir B-properties.23 Aparadigmaticexamplecomesfromthephilosophyofmind, where A isthesetofmentalpropertiesand B isthesetofbrainproperties. Superveniencethensaysthattwopeoplecannothavedifferentmentalpropertieswithoutalsohavingdifferentbrainproperties.BoltzmannianSMpositsthat therelationbetweenmacro-statesandmicro-statesisjustlikethis:twosystems cannotbeindifferentmacro-stateswithoutalsobeingindifferentmicro-states. Or,inotherwords,itcannotbethatthepositionandmomentaofallmolecules intwogasesareidenticalwhilethemacro-conditionsofthetwogasesare different.Forthisreason,everymicro-state x hasexactlyonecorresponding macro-state,whichwecall M ðxÞ.

Thecorrespondencebetweenmicro-statesandmacro-statestypicallyisnot one-to-one:severalmicro-statescancorrespondtothesamemacro-state,meaningthatmacro-statesare multiplyrealisable.If,forinstance,weswapthe positionsandmomentaoftwomolecules,themacro-stateofthegasdoesnot change.Itisthennaturaltogrouptogetherallmicro-states x thatcorrespond tothesamemacro-state M: XM ¼ x 2 X suchthat M ðxÞ¼ M g f XM isthe

22 Fordiscussion,see,forinstance, Albert(2000), Frigg(2008b),and Goldstein(2001).

23 Thisbasicideacanbedevelopedindifferentways,butnothinginourdiscussiondependson thesedifferences.Forasurvey,see McLaughlinandBennett(2021).

macro-region of M,which,bydefinition,containsallandonlythosemicrostatesthatcorrespondtomacro-state M

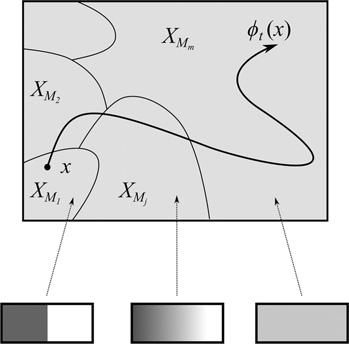

Nowconsideracompletesetofmacro-states:asetthatcontainseverymacrostatethatthesystemcanbein.Tokeepthingssimple,assumethatthereis onlya finitenumber m ofsuchstates.24 Letthiscompletesetbe M 1 ; ... ; M m g f . Itisthenthecasethatthesetofcorrespondingmacro-regions,

X M 1 ; ... ; X M m g f ,formsapartitionof X,meaningthattheelementsoftheset donotoverlapandjointlycover X.Thisisillustratedin Figure6.Asin Figure2, thelargesquaresymbolisesthestatespace X,andthecurvedthinlinessymbolisethepartitionofthestatespaceintodifferentmacro-regions. Figure6 also showsthatifthesystemunderstudyisagas,thenthemacro-statescorrespond tothedifferentstatesofthegasweencounteredin Section1.1

Thisraisestwofundamentalissuesthatoccupycentrestageindiscussions aboutBSM.The firstissueconcernsthenatureandoriginofmacro-states.In thepreviousparagraphwesimplypostulatedthatthereisacompleteset M1 ; ... ; Mm g f ofmacro-statesalongwiththecorrespondingset XM1 ; ; XMm g f ofmacro-regions.Butwhatisthenatureofthesemacrostatesandwheredothesecomefrom?Andthereisalsoaquestionaboutthe structureofthesesets.Aswehaveseenearlier,systems,whenpreparedin anon-equilibriumstateandthenlefttothemselves,approachequilibrium.This meansthatoneofthemacro-statesinoursetmustbetheequilibriumstate.How isthisstateidentified,andwhatareitscharacteristics?Aswehaveseenin Section2.1,thestatespace X comesequippedwithameasure μ thatallowsusto sayhowlargeapartof X is.Thismeasurecannowbeusedtoattributeasizeto

24 Thisassumptionholdstrueinthemostcommonwaytoconstructmacro-states,whichwediscuss inthenextsection.Ingeneral,thisisanidealisationandsystemscanhaveaninfinitenumberof macro-states.Nothinginthissectiondependsonthenumberofmacro-statesbeing finite.

Figure6 Thestatespace X withthepartitionofmacro-regions.

themacro-regionsand,aswewillseelater,itturnsouttobethecasethat equilibriumisthemacro-statewiththelargestmacro-region.Hence,theevolutionfromnon-equilibriumtoequilibriumcanbeunderstoodastheevolution fromasmallertolargermacro-region.Thisisindicatedin Figure6,wherethe largestmacrostate, XMm ,correspondstotheequilibriumstateofthegas,and thesmallesttoitsinitialstate.

Thesecondissueconcernstheapproachtoequilibrium.Intheframeworkwe haveoutlinedsofar,anapproachtoequilibriumtakesplaceifthetimeevolution ofthesystemissuchthatamicro-state x inanon-equilibriummacro-region evolvessothat t ðxÞ comestolieintheequilibriummacro-regionatalaterpoint intime,asalsoillustratedin Figure6.Ideally,onewouldwantthistohappenfor all x inanynon-equilibriummacro-region,becausethiswouldmeanthatall non-equilibriumstateswouldeventuallyapproachequilibrium.Thequestion nowisunderwhatconditionsthiswouldbethecase,andindeed,whetherthisis possibleatall.

Beforeturningtothesequestions,letusintroducethe BoltzmannentropySB, whichisapropertyofmacro-statesdefinedthroughthemeasuresoftheir macro-regions: SB ðMi Þ¼ kB log½μðXMi Þ forall i ¼ 1; ... ; m,where kB isthesocalledBoltzmannconstant.Sinceasystemisinexactlyonemacro-stateatany instantoftime,theBoltzmannentropycanequallyberegardedasapropertyof asystemitself.Let M(x(t))bethemacro-stateofthesystemattime t.The Boltzmannentropyofthesystemattime t thensimplyistheBoltzmannentropy of M(x(t)).Sincethelogarithmisamonotonicfunction,thelargerthemeasure μ ofamacro-region,thelargertheentropyofthecorrespondingmacro-state.This impliesthatiftheequilibriummacro-statehasthelargestmacro-region,thenit alsohasthehighestBoltzmannentropy.Theapproachtoequilibriumcanthen bedescribedasatransitionfromlowtohighBoltzmannentropy.

Thisframeworkisthebackboneofpositionsthatidentifyas ‘Boltzmannian’ . Differencesappearinhowtheelementsofthisframeworkarearticulatedandin whatisaddedtothem.Beforemovingon,wewouldliketodrawattentiontoan importantissue,whichhasimplicationsforhowthetheoryisdeveloped.As introducedsofar,macro-regionsaresubsetsofthestatespace X.Thisishow macro-regionsarestandardlyintroducedintheliterature,andwefollowthe conventioninthissection.However,aswehaveseenin Section2.2,themotion ofanautonomousHamiltoniansystemisconfinedtothehypersurface XE , whichisa6n – 1-dimensionalsubsetofthefull6n-dimensionalstatespace X. Often – forinstanceinthecasediscussedinthe nextsection wheretheequilibriumisgivenbytheMaxwell–Boltzmanndistribution – theequilibriumstate dependsontheenergyofthesystem(andtherealsomightbefurtherconserved quantitiesthattheequilibriumdependson).Thismeansthatallmacro-states

thatthesystemcanpotentiallyvisitgivenacertaininitialstatearedefined relativetotheenergyofthesystem (andsometimesalsorelativetotheinvariant surfacescorrespondingtootherconservedquantities).Insuchcases,when tryingto findtheequilibriumstate,onehastoconsidermacro-regionsthatlie in XE ratherthanin X andworkwithameasure μE on XE ratherthanwiththe measure μ on X (or,again,iftherearefurtherinvariantsurfaces,onehasto find theequilibriummacro-statebyconsideringmacro-statesrelativetoconstant valuesofallinvariantsurfaces).25

3.2DefiningEquilibrium:TheCombinatorialArgument

Inhis(1877),Boltzmannpresentedaningeniouswaytoaddressthe fi rst issuementionedinthe previoussection ,toconstructmacro-statesandto identifyequilibrium.Boltzmann’sargumentfocusesonthestatespaceof one particleofthesystem,whichinthecaseofagashassixdimensions.

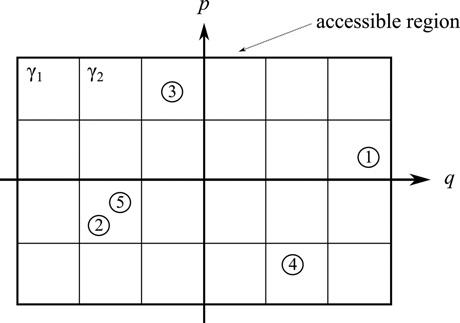

Sincethegasisconfi nedtoabox,theparticlescannotmovebeyondthebox andtheirenergyisbounded(noparticlecanhavemorethanthetotalenergy ofthegas).Thismeansthattheparticlecanaccessonlya fi niteregionofits statespace.Thisisthe accessibleregion.Thisisschematicallyrepresented in Figure7,wherethelargerectanglesymbolisestheaccessibleregion(and bewareoftheschematiccharacterofthis fi gure:wecanonlydrawone p and one q axis,butthespacehasthree p andthree q axes).Themicro-stateof asystemisaspeci ficationofthepositionandmomentaofallparticles.Aswe

Figure7 Coarse-grainingontheone-particlespace.

25 Foramoredetaileddiscussionoftheroleofmacro-regionsandmeasuresonsubsetsof X whendeterminingtheequilibriumstate,see WerndlandFrigg(2015a) .Inthiscontext,note thatthemeasure μ on X canberestrictedto XE inanaturalway;fortechnicaldetails,see Frigg (2008b ,180).

haveseen,inthe ‘full’ 6n-dimensionalstatespace X thisstateisgivenbyone point.Butthisisnottheonlywaytospecifythestate.Wecanequallyspecifythe statewith n pointsinthe6-dimensionalone-particlespace.Thisisalsoillustrated in Figure7,wherethenumberedcirclesindicatethestateoftheparticles:the centreofthecirclewithnumber1denotesthestateofparticlenumber1,and soon.

Thecrucialmovenowistointroduceagridonthespace – anoperation knownas coarse-graining.Thisgridde fines coarse-grainedmicro-states: twoparticleshavethesamecoarse-grainedmicro-stateiftheyareinthe samegridcell.Welabelthegridcells γ1 , γ2 , ....Thecellsaresuchthatthey allhavethesamesize.Aspeci ficationofthecoarse-grainedmicro-stateof everyparticleinthesystemiscalledan arrangement .Thatis,anarrangementisalistwith n entriesofthefollowingform:particlenumber1iscell γ56 ,particlenumber2isincell γ21 ,andsoon.Again,thisisillustratedin Figure7 .Atthispointthereisacrucialrealisation:ifweareonlyinterested inthemacropropertiesofthegas,thenanarrangementcontainstoomuch information.Thisisbecauseitisirrelevantforthesystem’smacrofeatures whichparticleisinwhichstate.Whetherparticlenumber1isincell γ56 and particlenumber2isincell γ21 ,orviceversa,hasnoeffectonquantitieslike thelocalpressureofthegas.Thismeansthatthemacro-stateofthegasmust beunaffectedbyapermutationoftheparticles.Thismeansthatthemacrostateofthegasonlydependsonthe distribution ofparticles,aspecifi cation ofhowmanyparticlesthereareineachgridcell.

ThecoreideaofBoltzmann’sapproachistodeterminehowmanyarrangementsarecompatiblewithagivendistribution,andtodefinetheequilibrium stateastheoneforwhichthisnumberismaximal.Tothisend,letusintroduce ni ,thenumberofparticlesincell γi ,forallcells.Hence,adistribution D is avector ðn1 ; ... ; nk Þ,where k isthenumberofcoarse-grainedmicro-states. Someelementarycombinatoricsthenshowsthatthenumberofarrangements thatarecompatiblewithagivendistribution D is

GðD

Þ¼

n! n1 ! ... nk ! ;

wheretheexclamationmarkdenotesthefactorial(i.e. n! ¼ 1 2 ... n). Makingthestrong(and,aswewillsee,unrealistic)assumptionthattheparticles inthegasarenon-interactingandthattheenergyofthegasispreserved, Boltzmannshowedthatthedistributionthathasthelargestnumberofcompatiblearrangementsistheoneforwhichthe ni satisfytheso-calleddiscrete Maxwell–Boltzmanndistribution:

where Ei istheenergyofparticleincell γi ,and α and β areconstantsthatdepend onthenumberofparticlesandthetemperatureofthesystem(Tolman1938/ 1979,ch.4).Thisistheequilibriumdistributionofthegas.From amathematicalpointofview,derivingthisdistributionisaproblemincombinatorics,whichiswhytheapproachisnowknownasthe combinatorial argument (Uffink2007,974).

TheviewthattheMaxwell–Boltzmanndistributionistheequilibriumdistributionofthegasreceivesindependentsupportfromanargumentdueto Maxwell.Indeed,Maxwellhadalreadyderivedthisdistributioninhis(1860/ 1965),and,crucially,hisderivationisentirelyindependentfromconsiderations ofhowmanyarrangementsarecompatiblewithadistribution,andindeedfrom achoiceofcoarse-grainingontheone-particlespace.Maxwell’sderivationwas basedsolelyonthepositthatgasparticlesmoveinthesamewayinallspatial directionsandthatthereforethedistributionfunctionmustfactoriseintofunctionsoftheorthogonalcomponentsoftheirvelocities.Hence,theequilibrium distributionthatthecombinatorialargumentprovidesisknowntobethe equilibriumdistributionforreasonsthatareindependentofthecombinatorial argument.

Theseconsiderationsconcernthestatespaceof one particle.Thisisdifferent fromourconsiderationssofar,whichhaveallbeenintermsofthe6n-dimensionalstatespace X oftheentiresystem.Sothequestionis:whatdoesthe combinatorialargumenttellusaboutmacro-regionsin X asintroducedinthe previoussection?Thegoodnewsisthattheresultstranslate.Itisobviousthat everypointin X correspondstoadistributionintheone-particlespace(because bothspecifythepositionandmomentaofallparticles).Onecanthensaythatall pointsin X thatcorrespondtothesamedistributionconstituteamacro-region. Thisisplausiblebecause,aswehaveseen,themacropropertiesofthegasonly dependonthedistribution D.Wenowneedaconnectionbetweenthenumberof arrangementscompatiblewithagivendistributionandthemeasureofmacroregions.Thisconnectionisprovidedbythefollowingresult:

where XD isthemacro-regionassociatedwithdistribution D and Δ isthesizeof acellofthecoarse-graining(asshownin Figure7).Hence,thesizeofamacroregionisproportionaltothenumberofarrangementscompatiblewiththe distributionassociatedwiththemacro-region.Thisleadsdirectlytothedesired result:since GðDÞ ismaximalfortheMaxwell–Boltzmanndistribution,the

μðXD Þ¼ GðDÞΔn ;