Mathematical Rigour and Informal Proof 1st Edition Fenner Stanley Tanswell Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/mathematical-rigour-and-informal-proof-1st-edition-fe nner-stanley-tanswell/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Syllogistic Logic and Mathematical Proof Prof Paolo. Mugnai Mancosu (Prof Massimo.)

https://ebookmass.com/product/syllogistic-logic-and-mathematicalproof-prof-paolo-mugnai-mancosu-prof-massimo/

Corruption and Norms: Why Informal Rules Matter 1st Edition Ina Kubbe

https://ebookmass.com/product/corruption-and-norms-why-informalrules-matter-1st-edition-ina-kubbe/

Big Chance Cowboy Teri Anne Stanley [Stanley

https://ebookmass.com/product/big-chance-cowboy-teri-annestanley-stanley/

Final Proof Rodrigues Ottolengui

https://ebookmass.com/product/final-proof-rodrigues-ottolengui-2/

https://ebookmass.com/product/final-proof-rodrigues-ottolengui/

Socioeconomic Protests in MENA and Latin America: Egypt and Tunisia in Interregional Comparison 1st ed. Edition Irene Weipert-Fenner

https://ebookmass.com/product/socioeconomic-protests-in-mena-andlatin-america-egypt-and-tunisia-in-interregional-comparison-1sted-edition-irene-weipert-fenner/

The Burden of Proof upon Metaphysical Methods 1st Edition Conny Rhode

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-burden-of-proof-uponmetaphysical-methods-1st-edition-conny-rhode/

An Introduction to Proof Theory: Normalization, CutElimination, and Consistency Proofs 1st Edition Paolo Mancosu

https://ebookmass.com/product/an-introduction-to-proof-theorynormalization-cut-elimination-and-consistency-proofs-1st-editionpaolo-mancosu/

Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning in Pathology 1st Edition Stanley Cohen Md (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/artificial-intelligence-and-deeplearning-in-pathology-1st-edition-stanley-cohen-md-editor/

The Philosophy of Mathematics Mathematical Rigour and Informal Proof Fenner Stanley Tanswell

ElementsinthePhilosophyofMathematics Ediitedby PenelopeRush

UniversityofTasmania

StewartShapiro

TheOhioStateUniversity

MATHEMATICALRIGOUR ANDINFORMALPROOF FennerStanleyTanswell TechnischeUniversitätBerlin

ShaftesburyRoad,CambridgeCB28EA,UnitedKingdom OneLibertyPlaza,20thFloor,NewYork,NY10006,USA 477WilliamstownRoad,PortMelbourne,VIC3207,Australia

314–321,3rdFloor,Plot3,SplendorForum,JasolaDistrictCentre, NewDelhi – 110025,India

103PenangRoad,#05–06/07,VisioncrestCommercial,Singapore238467

CambridgeUniversityPressispartofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment, adepartmentoftheUniversityofCambridge.

WesharetheUniversity’smissiontocontributetosocietythroughthepursuitof education,learningandresearchatthehighestinternationallevelsofexcellence.

www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle: www.cambridge.org/9781009494380

DOI: 10.1017/9781009325110

©FennerStanleyTanswell2024

Thispublicationisincopyright.Subjecttostatutoryexceptionandtotheprovisions ofrelevantcollectivelicensingagreements,noreproductionofanypartmaytake placewithoutthewrittenpermissionofCambridgeUniversityPress&Assessment. Whencitingthiswork,pleaseincludeareferencetotheDOI 10.1017/9781009325110

Firstpublished2024

AcataloguerecordforthispublicationisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary.

ISBN978-1-009-49438-0Hardback

ISBN978-1-009-32510-3Paperback

ISSN2399-2883(online)

ISSN2514-3808(print)

CambridgeUniversityPress&Assessmenthasnoresponsibilityforthepersistence oraccuracyofURLsforexternalorthird-partyinternetwebsitesreferredtointhis publicationanddoesnotguaranteethatanycontentonsuchwebsitesis,orwill remain,accurateorappropriate.

ElementsinthePhilosophyofMathematics

DOI:10.1017/9781009325110 Firstpublishedonline:March2024

FennerStanleyTanswell TechnischeUniversitätBerlin

Authorforcorrespondence: FennerStanleyTanswell, fenner.tanswell@gmail.com

Abstract: ThisElementlooksatthecontemporarydebateonthenature ofmathematicalrigourandinformalproofsasfoundinmathematical practice.Thecentralargumentisforrigourpluralism:thatmultiple differentmodelsofinformalproofaregoodataccountingfordifferent featuresandfunctionsoftheconceptofrigour.Toillustratethis pluralism,theElementsurveyssomeofthemainoptionsinthe literature:the “standardview” thatrigourisjustformal,logicalrigour; themodelsofproofsasargumentsanddialogues;therecipemodelof proofsasguidingactionsandactivities;andtheideaofmathematical rigourasanintellectualvirtue.Thestrengthsandweaknessesofeach areassessed,therebyprovidinganaccessibleandempiricallyinformed introductiontothekeyissuesandideasfoundinthecurrentliterature.

Keywords: mathematicalrigour,informalproof,mathematicalpractice, formalisation,epistemologyofmathematics

©FennerStanleyTanswell2024

ISBNs:9781009494380(HB),9781009325103(PB),9781009325110(OC) ISSNs:2399-2883(online),2514-3808(print)

1Prologue:ThreeProofs? Beforewebeginwiththephilosophy,anElementaboutmathematicsshould startwithsomemathematics.

Proof1:SumsofOddIntegers Hereisaclassicproofby DeMorgan(1838),updatedintomodernnotation:1

Theorem: Thesumofthe first n oddpositiveintegers,startingfromone,is n2 :

Proof: LetPnðÞ bethestatement “Xn k ¼1 2k 1 ðÞ¼ n 2 ”

Since X1 k ¼1 2k 1 ðÞ¼1 ¼ 12 weseeP 1 ðÞ istrue.

AssumePnðÞ istrue.Then

1

1

HencePn þ 1 ðÞ istrue.

SinceP 1 ðÞ istrueandPn þ 1 ðÞ followsfromPnðÞ weconcludethatPnðÞ istrue forallnbytheprincipleofmathematicalinduction.

Thisproofisatypicalrigorousproof,thesortstudentsaregivenwhenthey first learnaboutmathematicalinduction.Intheirstudyofmathematicalrigour, SangwinandKinnear(2021) foundthisprooftoberatedbyfarthemost rigorouspresentationofthisresultamongstaselectionofdifferentproof methodsandstyles.Therearenoerrorsandnogaps.Thisproofaccordingly canbetakenasaparadigmexampleofinformalrigour.

Proof2:Malfatti’sMarbleProblem Incontrasttothepreviouscorrectandrigorousproof,letuslookatthehistoryof a failed proof:2 thatofMalfatti’smarbleproblem.3 Theproblemisabouthowtocut threecircular “pillars” outofatrianglewhileminimisingtheamountofmarble wasted.Mathematically:withinagiventriangle,to findthreenon-overlapping

1 TheexactversionI’musinghereisby Sangwin(2023)

2 Aterminologicalnoteontheword “proof”:onewayofusing “proof” isasasuccessterm, meaningthat “failedproof” isa nonsequitur,orhastobereadas “afailed attempt ataproof” . AcentralthemeofthisElementisthephilosophicalcomplexityofseparatingcorrect,valid,or rigorousproofsfromincorrect,invalid,orunrigorousones.Therefore,Iwilluse “proof” inthe weakersenseofsomethinglikea “purportedproof” ora “possiblecandidateforbeingaproof” , meaningsomethingcreatedtobeaproof,presentedaccordingtothenormsofproofpresentation, withoutobviousreasonsforjudgingtheminvalid,andsoon.

3 Thishistoricaldescriptionprimarilydrawson Andreattaetal.(2011) and Lombardi(2022a).

circleswiththegreatesttotalarea.ThisproblemwasnamedafterGianfrancesco Malfatti(1803),thoughithadalsoappearedearlierinJapanintheworkof ChokuyenNaonobuAjimaandwasstudiedforthespecialcaseofisosceles trianglesbyJacobBernoulli(see Andreattaetal.2011).

Inhisarticle, Malfatti(1803) assumesthatthesolutiontothemarbleproblem isgivenby findingwhatarecalledthe “Malfatticircles”:theuniquetrioof circlesinsideatrianglethataretangenttooneanotherandtouchtwosidesofthe triangleeach(Figure1).4

ForMalfatti,theproblemwasto findawaytoconstructthesecirclesfor agiventriangle.Thatis,hebelievedtheareamaximisationproblemwassolved viathecircleconstructionproblem.Malfattihimselfworkedonthelatter problemtogiveaninitialsolution,andanelegantstraightedge-and-compass solutionwasgivenby Steiner(1826).Foracentury,Malfatti’smarbleproblem wasconsideredsettled.

However,itwasshownby LobandRichmond(1930)thattheMalfatticircles donotalwaysmaximisethearea,becauseinanequilateraltrianglethe “greedy” arrangementhasaslightlylargerarea(see Figure2).Thegreedyarrangement involvesplacingthelargestpossiblecircle first,thenthelargestpossibleonein theremainingspace,thendoingsooncemore.

Figure2 Malfatticirclesandthe “greedy” arrangementforanequilateral triangle.

4 Imagespublicdomain,viaWikimediaCommons,createdbyuserPersonline.

Figure1 Malfatticircles.

Likewise, Eves(1965,pp.245–7)noticedthatforalongisoscelestriangleit isbettertostackthreecircles,asin Figure3,thantouseMalfatti’scircles.

Amazingly, ZalgallerandLos’ (1994) eventuallyshowedthattheMalfatti circles never havethemaximumarea,andMalfattiwassimplymistaken. ZalgallerandLos’ (1994) werethemselvesalsoattemptingtomakeworkby Los’ fouryearsearlierrigorous,workwhichtheysay “containedsignificant gaps” (p.3163).Eventhen,theirproofoftheoptimalityofthegreedyalgorithm isincomplete,asarguedby Lombardi(2022a).Theirsolutionisbasedon enumeratingthepossiblearrangementsofcirclesandthenexcludingallbut thegreedyarrangementfrombeingmaximal,butthelemmathatenumeratesthe possiblearrangementsisunproven.Furthermore,thetrickiestcasetoexcludeis tackledbynumericalcheckingonsamplepointsgiveninatable,ratherthanby amathematicalproof.Thenumbersbeingcheckedarealsoobtainedbysubtractingonedecreasingfunctionfromanother,butthenumericalchecking missesthefactthatthetotalwillnotnecessarilytherebybedecreasingtoo.5

Onlyrecentlyhas Lombardi(2022a) closedthesegapsandproducedafully rigorousproofofthemaximalsolution,whichisthegreedyarrangementandnotthe Malfatticircles.Thishistoryrevealsfourdifferentfailuresofrigour:(1)themistaken assumptionsmuggledinthatoneproblemhasthesamesolutiontoanother;(2) makinguseofunprovenlemmas;(3)usingnumericalmethodsthatarenotsufficient toestablishtheresult;and(4)simplemathematicalerrors,likethinkingadecreasing sequencesubtractedfromanotherisalwaysdecreasing.Therearethusmultiple seductivewaysthatmathematicscangowrong,evenforsuchaseeminglysimple problem.Nonetheless,thisstoryalsorevealssomeofthecomplexityofdeveloping rigorousmathematics,ultimatelyculminatinginasuccessfulproof.

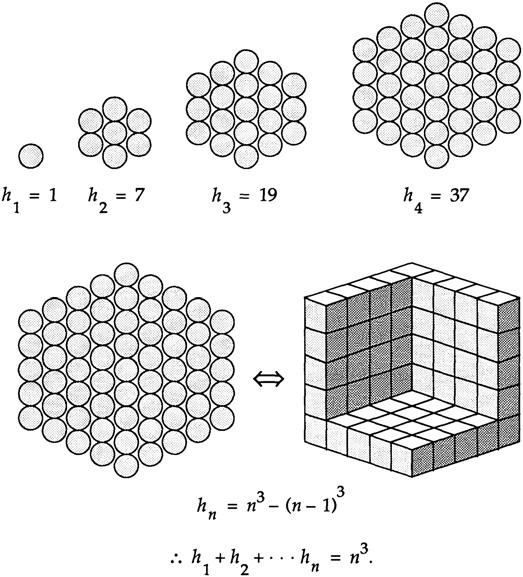

Proof3:HexNumbers Finally,letuslookatatrickycase.Thefollowingisoneofmyfavouriteproofs fromthe firstvolumeofthe ProofsWithoutWords series(Nelsen1993, 2000, 2015)andiscalled “SumsofHexNumbersareCubes” (Nelsen1993,p.109), withthereadershownthe firstfourhexnumbersatthetoptolearnwhatthey are,followedbytheproof(Figure4).

5 Lombardi(2022b) detailsvariousothergapsanderrors.

Figure3 Optimal “greedy” arrangementforalongisoscelestriangle.

Figure4 Nelsen’sproofthatsumsofhexnumbersarecubes. ProofWithout Words ©1993heldbytheAmericanMathematicalSociety.

Onemightcallthisa “proofbyGestaltshift”,wherethemainideainvolves ashifttoseeinghexnumbersinadifferentway,astheouterlayerofacube.While thisisinmyviewaproof – ifoneunderstandsitproperly,onecanseewhythe resultmustfollow – itwouldbehardtoarguethatthisisa rigorous proof.Firstof all,itneverevengivesanalgebraicdefinitionofwhathexnumbersare.Second,it implicitlycontainsaninductionproofbutdoesnotmakethekeyingredientsofan inductionexplicit.Third,theGestaltshiftismerelyillustratedfortheparticular caseofthe fifthhexnumber,sounderstandingtheinductivesteprequiresusto fill inthereasoningofwhyitholdsgenerally.Sufficientunderstandingandmathematicalinsightareenoughto fillinthesegaps,butthereisnodenyingthattheyare gaps,andthattheproofisgappyenoughnottoberigorousbyitself.

Thequestionsweface,then,are:whatisthedifferencebetweenthethree “proofs” wehaveseen?Andwhatismathematicalrigouranyway?

2Introduction InthisElementIwillsetouttherangeofanswersthatareavailablein contemporaryphilosophyofmathematicstothequestionsaboutrigourand informalproofs.Recentdecadeshaveseena practicalturn thatshiftsaway

fromtryingtoanswerphilosophicalquestionsaboutmathematicsintheabstract aloneandtowardsphilosophicalpositionsthatareinformedbythepracticesof mathematicians. 6 Theideaisthatmathematics,whilebeingabstractandlogical initssubjectmatter,isalsoadisciplineshapedbyhumaninterestsandvalues likeanyother,andthatanswerstoquestionsaboutmathematicalrigourarenot independentoftheactivitiesinvolvedindoingmathematics.

Theconceptofrigourcanapplytomanykindsofmathematicalpractices.The onethathasinterestedphilosophersthemost,andwhichIshallfocuson throughout,istheideaof rigorousproof.Arough firstpassisthatarigorous proofisadetailed,logicalproofthatisfreeoferrorsandgaps.Anotherimportant applicationis rigorousdefinition,adefinitionthatispreciseenoughtosettleforall caseswhetheritappliesornot.7 Thequestfor rigorousfoundations involves findingexplicitaxiomsandinferencerulestoencodeacceptableassumptionsand reasoningformathematics.8 Furthermore, rigorousareasofmathematics are thosewhereresultsandtechniquesarereliable,well-defined,andreproducible, withclear,agreed-uponinferentialpracticesandfoundations.9 Itisalsocommon tosee mathematicalrigourinphysics contrastingscrupulousandcarefulreasoningwithmoreconjectural,empirical,orexperimentalapproaches.10

Exploringthenotionofrigourinallofthesesenseswouldbetoomuchfor suchashortwork,somytaskwillbetosetoutthecontemporarydebateson mathematicalrigourandinformalproofs.Broadlyspeaking,informalproofsare thoseproofsaswritteninactualmathematicalpractice,suchasinjournals, textbooks,lectures,seminars,classrooms,onlineforums,emails,scribbledon napkins,andsoon.Thecentralquestionisthis:isthereasingleconceptof rigouracrossthesemanymathematicalcontexts,andwhatisit?

2.1ThePurposesofRigour Ithinkitisimportanttoconsiderthepurposeofhavingaconceptofrigourand whatitisbeingusedforinthemanycontextsinformalproofsmightshowup.In fact,theconceptofmathematicalrigourcanbeputtomanydifferentuses.This matchestheideathatproofsthemselvesdonothaveasinglepurpose.Catarina DutilhNovaes(2021,§11.4)surveyssomeofthemainusesofproofs,listing

6 Overviewsofthestateofthe fieldof ‘philosophyofmathematicalpractice(s)’ havebeengiven by VanBendegem(2014), Löwe(2016), Carter(2019),and HamamiandMorris(2020)

7 Formoreondefinitionsinmathematics,see Tappenden(2008), Cellucci(2018), Coumans (2021),and CoumansandConsoli(2023)

8 See,forexample, Maddy’s(2017, 2019)carefulworkonthemanypossiblepurposesofsettheoreticfoundations.

9 Foracasestudyofthisgoingawry,see DeToffoliandFontanari(2022, 2023)ontheItalian schoolofalgebraicgeometry.

10 SeethediscussionoftheJaffe–Quinndebatein Section5.3.

verification,certification,persuasion,explanation,innovation,andsystematisation.Likewise,wecanlistvariousfunctionsthattheconceptofrigourisoften saidtobeusedfor:

(1) Soundness. Arigorousproofprotectsusfromerrorsandcounterexamples. Historically,rigourwasadrivingforceinthemodernisationofmathematics.Concernsaboutinfiniteandinfinitesimalquantities,especiallyin analysis,reachedapeakinthenineteenthcenturywiththeappearanceof mathematical ‘monsters’ suchastheWeierstrassfunction,necessitatingthe “rigorisationofanalysis” and ε-δ definitions.

(2) Verification. Arigorousproofverifiesthatatheoremistrue.

(3) Certainty. Rigorousproofsarethosethatcanbeusedtoobtainmathematicalknowledge.Theycanprovideahighlevelofapriorijustification,and absolutecertaintyinthetruthofthetheorem.

(4) BodyofKnowledge.Rigorousproofsformabodyofknowledgethatother mathematicianscanaccessandbuildon.

(5) Social. “Rigorous” isusedasalabeltoidentifywhichpiecesofmathematicsbyothermathematiciansaregoodandworthspendingtimeon.

(6) Demarcation. Theuseofrigorousproofsistakentobeoneofthemain criteriathatseparatesmathematicsfromotherdisciplines.11

(7) Conviction.Arigorousproofshouldconvinceareasonablebuttough audienceofthetruthofthetheorem.

(8) PeerReview. Beingrigorousisoneofthestandardsforpublishable mathematics.Inassessingtheworkofothermathematiciansinpeerreview, primarilyforresearchjournals,rigourisoneofthemainpropertiesthe proofsneedtohave.

Thislistisfarfromexhaustivebutgivessomeofthemainpotentialpurposesof rigour.12 Obviously,someofthesepurposesalsolinktopurposesof proof,such astheideathatonlyarigorousproofcantrulyverifyatheorem.Ontheother hand,somepurposesofproofsmightbebetterachievedinalessrigorous fashion,forexample,aproofmightbemoreexplanatorybyproviding acompellingintuitiveideathanbyrigorouslygoingthroughallofthedetails. Thesepurposesaredebatabletovaryingdegrees,sotheycanguideourdiscussioninthe followingsection butcannotbeimmutableconstraintsonaccountsof rigour.Aswewillseeshortly,thepluralityofpurposesforrigourwillconnectto myproposalthatweneedtobe rigourpluralists.

11 Thisgoalisnotablydefendedby Auslander(2009).

12 Italsoremainstobeseenhowsuccessfulmathematicsisatmeetingthesefunctions.For example,theideathatmathematicalproofscanproducecertaintyisapopularonebuthas beenwidelychallenged(e.g. Kitcher1984; Ernest1998; DeToffoli2021a).

Onetrickyfeatureofmathematicalrigouristhatitisusedbothdescriptivelyand normatively.The descriptive useconcernswhenandwhycertainproofsare called “rigorous” inpractice.The normative useconcernsrigourasanidealfor mathematics,thatis,thatmathematicsoughttobedoneinawaytomeetthe standardsofrigour.Thesedifferentusesraisedifferentquestionsaboutrigour. Thedescriptiveuseofrigourposesanempiricalquestion:whichkindsof mathematicsareactuallydescribedas “rigorous”?Thenormativeuseofrigour promptstwofurtherquestions.The firstquestionisthe thoroughlynormative one:whatstandardsoridealsshouldmathematicsbeheldto?Thesecond questionisa hybriddescriptive–normative one:whatstandardsdomathematicians say or believe theyapply?Itispossiblefortheanswerstoallthree questionstocomeapartorcoincideinanycombination.Lifewouldbesimple ifthedescriptiveusefollowedthenormative;thattheproofsdescribedas rigorouswerejusttheonesthatmeettheidealstandards,whicharealsojust whatmathematicianssaytheyare.Alternatively,itcouldbethattheanswersall comeapart;thatthestandardsbeingappliedarenottheonesthatmathematicianssaytheyapply,whicharealsonotthestandardsthatoughttobeused.

Ofthethreequestions,onlythenormativeonelooksimmediatelyphilosophicaland,eventhen,mathematiciansmightprefertokeepitforthemselvesto sortout.So,whatroledoesphilosophyplayinuntanglingthesevarious purposesandquestionsaboutrigour?ThewayIseethephilosophers’ job hereisingivingaccountsofmathematicalrigourthatenlightenandinform. Theconceptofrigourismultifaceted,unwieldy,andmessy,soanaccountof rigourshouldtrytounifyandexplainitsmainfeatures.Thelistofpurposesin the previoussection isanexampleofthismessiness:someofthemarenormativeideals,someofthemaredescriptive,andotherscanbereadeitherway.

Intheexistingliterature,theimplicitapproachtogivinganaccountofrigour seemstobeto findsomethinglikethe “trueessence” ofmathematicalrigour. Thiswouldseemtosupposethatoneconceptisfulfillingall – oratleastthe mostimportant – functionsofrigour.Aproponentofthisapproachwouldalso likelysaythattheyaremostinterestedinthenormativequestionofwhatthe idealstandardsofmathematicsare.Forthemitwouldbebetter,butnotessential,ifthisweretotrackmathematicians’ practicesandwhattheysaythose standardsare.However,theymuststillbecommittedtoatleastapproximating thedescriptivefeaturesofmathematicalpracticebecauseatheorypredicting thatallproofsdescribedasrigorousarenotactuallyrigorouswouldnotbeof muchuseinsatisfyingthefunctionalrolesoftheconcept.Thisleadstotwo connectedchallengesforanaccountofrigourtomeet:

(1) Functionaladequacy:tosatisfysomeorallofthemainfunctionsofthe conceptofrigour.

(2) Descriptiveadequacy:tocoherewithorapproximatemathematicalpractices concerningrigour.

OnepurposeofthisElementistosurveytheexistingpositionsandtoarguethat noneofthemprovidesanaccountofrigourthatmeetstheseconditionswell enoughtobethe “trueessence” ofrigour.

2.3RigourPluralism ThroughoutthisElement,IintendtoadoptanovelpositionIshallcall rigour pluralism.Insteadofsearchingfora “trueessence” ofrigourandauniquecorrect account,Iwilltakethedifferentproposalsintheliteratureasdifferent modelsof rigour,inthesenseofscientificmodelling,andarguethatalloftheseconvey importantinsights.Onthisview,theexistingaccountsofmathematicalrigourare seenasdifferenttheoreticalmodelsthateachattempttocapturesomecombinationoffunctionsanddescriptiveandnormativeaspectsofrigour.Wewill investigatewhichfeaturesofmathematicalpracticeareincorporatedintoeach model,andwhichareabstractedoridealisedaway.Unlikethe “trueessence” approach,however,thesemodelswillnotbeassessedasultimatelyrightor wrong.Ibelievethatnosuchmodelissufficientforallthepurposesofthe conceptofrigour,norareanyofthemodelswithoutmerit.Therigourpluralist approachwillbetoassessthestrengthsandweaknessesofdifferentmodels, evaluatingwhichaspectsofrigourtheycapturewell,andwhichtheydonot.

Aproponentofthe “ trueessence ” approachmighttrytoobjectthatthe modellingapproachislessplausiblebecauseitsrigourisultimatelyabout logic,andthat arigorousproofisalogicalproof.WhileIagreewiththis slogan,Idonotbelievetheappealtologicisde finitivehere.Morebasicthan logicality,rigorousproofisaboutonewayofdoing good mathematics.Onthe modellingapproach,wecansaythatformallogiccanprovide models ofgood mathematicsandthemathematicalreasoningfoundinproofs.Themovetosee thisasalsoinvolvingscientifi cmodelling fi tsdirectlyintothe “ logicas modelling” viewputforwardby Cook(2000 , 2010 ), Shapiro(2014),and Kurji(2021) 13 Furthermore,itcanbeseenasexemplifyingtheapproachof conceptualmodellingproposedby LöweandMüller(2011).

13 Thephilosophyoflogichasobviousimporttoquestionsaboutthephilosophyofmathematics here,buthasbeensurprisinglyunderutilisedindebatesaboutrigour.Forexample,thewider debatesonlogicalpluralism(see Beall&Restall2005; Cook2010; Shapiro2014; Russell2019) andlogicalnihilism(see Franks2015; Cotnoir2018; Russell2018; Kurji2021)alsoshowusthat logicality isnotasettledmatter.

Wewillreturntotheideaofrigourpluralismacrossthecomingsectionsto weighhowthevariousmodelsofrigourandproofsucceedandfailatcapturingthe featuresweareinterestedin.Furthermore,theselectionofmodelsisalsomeantto illustratethepluralistpositionbyshowingthateachofthemmodelssomeaspects ofrigourandinformalproofswell,butthatnoaccountmodelsallofthefeatures well.AfulldefenceofpluralismwouldtakeupmoreroomthanIhavehere,but Ihopethatconsideringthemeritsofaselectionofmodelswillillustratethevalue ofrigourpluralismasaviableandpromisingpositionforthesedebates.

2.4TheHistoryofRigour MyfocusinthisElementwillbeonsettingoutthecontemporaryresearchon mathematicalrigourandinformalproofs,soIwillnotbediggingintothehistory ofthedevelopmentofmathematicalrigour.Suchashorttreatmentwouldnotdoit justice.Nonetheless,thehistoryofmathematicsisveryimportantand,likeany otherconcept,Iholdthattheconceptofrigourcannotbefullyunderstoodwithout referencetothehistoricalandsocialcontextfromwhichitemerged.For aphilosophicalworkthatengagesmoreexplicitlywiththehistoricaldevelopment ofrigour,see Burgess(2015,chs.1&2).Foramorerecentpartofthepictureof proofandrigour,see Mackenzie(2004).Alotofexcellentresearchinthehistory ofmathematicsisdirectlyengagedwithquestionsaboutthehistoryofmathematicalrigourandhowconceptionsofithavechangedovertime(e.g., Barany 2011, 2013; Haffner2021; Cantù&Luciano2021; DeToffoli&Fontanari2022).

2.5Outline Inthefollowingsections,Iwilloutlineandevaluateaselectionofmodelsof rigourandinformalproofs,groupedintofourbroadfamilies.The first,in Section3,isthemostprominentandorthodox,sometimescalledthe “standard view”:that rigourisformality.In Section4,wewilllookatmodelsofinformal proofsandrigourthatanalyseproofsasargumentsanddialogues. Section5 will focusonthe recipemodelofproofs,whereproofsareakintorecipesfor mathematicalactivities.Finally,in Section6,Iwillconsidertheideaof rigour asanintellectualvirtue ofthemathematician.

WiththiswideselectionofmodelsofrigourandinformalproofIhopeto illustratetheideaofrigourpluralism.Thesemodelsareatdifferentstagesof development,withsomelong-establishedandothersmorerecent,butIbelieveall ofthemareviablemodelsofmathematicalrigour.Myclaimisthattryingtosettle whichamongsttheseistheultimatecorrectaccountofrigourandproofis fruitless.Instead,eachoffersadifferentwayofmodellingimportantfeaturesof themessyconceptofrigourthattanglestogethernormsoflogicandmathematical

reasoning,realpracticesofmathematiciansandtheircommunities,andacomplex historyofdevelopment.TheprojectofthisElementistoconsiderthestrengths andweaknessofeachfamilyofmodels,andtorevealhowbetweenthemtheylet usseethediversefeaturesofmathematicalrigour.

3TheStandardView:RigourasFormality 3.1Introduction Our firstmodelofmathematicalrigourisoftenreferredtoasthe ‘standardview’ becauseitisseenasthedefaultpositioninmoderndiscussionsofmathematical rigour.14 Thestandardviewis,roughly,thatrigourinmathematicsshould simplyandstraightforwardlybeunderstoodas formal rigour.Thesenseof formalityinquestionisthatofformallogic,sothatarigorousproofmustbe alogicalderivationinsomesystemofformallogic.15 Thestandardview emergedalongsidemodernlogic,pioneeredbyprominentmathematicallogicianslike Frege(1884), Hilbert(1899),and WhiteheadandRussell(1910),as partofaquestto findthelogicalfoundationsofmathematics(see Ferreirós 2008).Thesefoundationsrequiredawaytoguaranteethateverystepinaproof isinaccordancewiththeexactrulesoflogic.Beforelong,thishadsolidified intothedominantviewamongmathematiciansandphilosophers,exemplified mostprominentlybytheBourbakigroup(see Hamami2019; Barany2020).In turn,thislegacyhasbeeninheritedbythecontemporaryproponentsofformal, computer-checkablemathematics,suchas Hales(2008), Gonthier(2008), Wiedijk(2008),and Avigad(2021).

Theobviousmotivationforthisviewisthatformalderivationsareby definitiongap-freeandhavepreciseandexplicitlystatedstandardsofcorrectness.So,itissafetosaythatallformalderivationsarerigorous.Itisextremely temptingtoclaimthatformalityisalsothe only waytoberigorous.Ifaproof hasgapsorreliesoninferentialmovesthatarenotexplicitlystated,thenthiscan introduceassumptionsthatarenotjustifiedorreasoningthatcouldleadto flawedconclusions.AnexampleofthiswasseeninthestoryofMalfatti’s marbleprobleminthePrologue,wherebothincorrectassumptionsandunrigorousmethodsledtounrigorousproofs. Detlefsen(2009)summarisedthe motivationforthestandardviewsuccinctly:

14 In Tanswell(2015) and Azzouni(2020)thisclassofviewshasalsobeencalled “derivationist” Aswillbecomeclear,Iactuallythinkthatcallingitthe “standardview” inthesingularis misleadingbecauseitisreallyafamilyofoverlappingviewswithimportantdifferences, somethingalsopointedoutby BurgessandDeToffoli(2022)

15 Infact,whatcountsasformalityisnotsostraightforward. DutilhNovaes(2011) identifiesmany differentwaysthatlogiccanbesaidtobeformal.

Thereasoningbehindthisviewisstraightforward:(i)properproofsare proofsthateitherareorcanreadilybemaderigorous;(ii)proofsthatareor canreadilybemaderigorousareformalizable;therefore(iii)allproperproofs areformalizable(Detlefsen2009,p.17).

Inthissection,wewillstartin Section3.2 withasimplisticversionofthisview, whichinvolvesaprocessof fillinginthegapsofinformalproofs,notingthatthis doesnotstanduptoscrutiny.Next,in Section3.3,Iwilloutlinevariousdesiderata foramoredefensibleversionoftheview.Withtheseinhand, Sections3.4, 3.5, and 3.6 willlookatarangeofmoresophisticatedversionsofthestandardview, specificallyonesinvolvingroutinetranslations, inprinciple formalisability,and derivation-indication. Section3.7 willthengivealonglistofcriticismsofthe standardview.Finally,in Section3.8 Iwillmakethecasethatthestandardviewis notacorrectaccountofmathematicalrigourbyitself,butthatitisapowerful familyof models ofinformalproofandmathematicalrigour.

3.2FillingintheGaps Whiletheideathatrigourreducestoformalitycanbeusefulasanormative ideal,thestandardviewneedstooffermoreinordertosuccessfullydescribe howpeoplejudgerigour.Mostproofsproducedbymathematiciansarenot formal,anditwouldbeanoddresultforsomethingcalledthe “standardview” topredictthatalmostnomathematicsiseverrigorous.Thestandardviewmust thereforeincludeanothercomponentthatexplainshowinformalproofscan nonethelessberigorousinsomesense.Thiscanbeapproachedinmanydifferentways,butthecommonthreadbetweenthemistheideathatinformalproofs canberigorousbycorrespondingtoformalproofs,eveniftheythemselves aren’tformalproofs.Inthisway,formalitycanstillbethegoldstandardfor rigour,butinformalproofscanmeetthisstandardindirectly.

Whatthecorrespondenceshouldamounttoinordertoidentifyrigorous informalproofsvariesfordifferentproposals.Thesimplestversionofthis ideaisthatinformalproofs abbreviate theirformalcounterparts,meaningthat simple,straightforwardstepsareleftoutfrominformalproofs,butcouldbe restoredbyaprocessof fillinginthegaps.Especiallyforsimpleproofs,thisidea isveryappealingbecauseitexplainswhylinkinginformalproofstoformalones stillmaintainsrigour.Thereasonisthatthemainstepsareallstillpresent,and the “missingsteps” areactuallyjusttheeasylogicalmovesthataretooobvious toneedstating.Theinformalproofisrigorousdespitethegapsbecauseany mathematiciancouldeasilysupplythestepsthathavebeenleftout.

However,theabbreviationapproachglossesovermanyoftheimportant details.Forexample,thestepsthat are givenininformalproofsarealsotypically

12 PhilosophyofMathematics notinaformallanguage,sotheywouldalsoneedtobeseenasabbreviationsof formulas,whichleadstothequestionofhowexactlytheyshouldbetranslated. Informalproofsalsodon’t flagwhichformalsystemisbeingusedinthe first place,andtherearemany,manyoptions.Translatinginformalsentencesinto formalonesisnotasstraightforwardasthe “fillinginthegaps” ideawouldmake itsound,ascanbeattestedbyanyonewhohaseverattemptedit.Furthermore,the abbreviationapproachwouldalsobelessclearformoreadvancedmathematics, wherethemissingstepsmaybelessobvious.Therefore,therearefurther complexitiesthatthestandardviewneedstoaddress.

3.3AimsfortheStandardView Beforewegetdeeperintopossiblewaysof fillingoutthestandardview,let’s discusswhatitshouldbeaimingtoachieve.InsomeofmypreviousworkIhave givenvariousdesideratathatthestandardviewmightaimtomeet(Tanswell 2015,sect.2).Letusbrieflysurveythese.

Tobegin,themainideabehindthestandardviewistoexplainrigorous informalproofs:

(Rigour) Togiveanaccountofhowinformalproofsare(orcanbesaidtobe) rigorousthroughtheirconnectiontoformalproofs.

Furthermore,theaccountshouldbeofpracticaluse,inthatitwouldideally provideinsightintowhichproofsdonotliveuptothecriteriaitestablishes:

(Correctness) Todistinguishcorrectinformalproofsfromincorrectones, thatis,thecorrespondenceshouldonlylinktheinformalproofsthatare correcttothejustifyingformalproofs.

Rigourandcorrectnessarecloselyconnected.Arigorousproofwillalsobe acorrectone,andsospecifyingcriteriaforwhenaproofisrigorouswillalso specifyaclassofcorrectproofs.Conversely,onemightthinkthattherearecorrect proofsthatarenotrigorous,suchasbyskippingtoomanydetailswhilegettingthe overallideasright,asinthesumofhexnumbersproofthatwesawinthe Prologue.Thisclassofproofswillhavegapsbutnoterrors,ascorrectproofs cannotcontainerrors.16 Onecould,alternatively,arguethatthisclassdoesn’t, strictlyspeaking,existatall,thatallproofsworthyofthenamemustberigorous. Inthatcase,therewouldbeonlytwocategories:correct,rigorousproofs,and

16 Eventhismightbetoostrongforactualpractice.Injointworkwith JoshuaHabgood-Coote (2023),weconsidertheenormousproofofthe ClassificationofFiniteSimpleGroups.Inthis case,themathematiciansseeminglyaccepttheproofdespitebelievingitwillinevitablycontain someerrorsduetoitssize,becausetheyareconvincedthattheseerrorswillbeso-calledlocal errorsthatcouldbe fixedwithouttoomucheffort,andwhichdonotaffectthecorrectnessofthe theoremoverall.

failedproofs.Thiswouldamounttorejectingtheproposedproofofthesumof hexnumbers.(Maybeonecoulddemoteittosomeintermediatething,like a “proofsketch” or “proofidea”.)Ideally,then,ifthestandardviewisappealing toformalproofstoidentifygapsanderrors,itshouldprovideguidanceonhowto separatecorrectandrigorousproofsfromthosewhicharenot.

Toarticulatethestandardviewproperlyrequiresonetoaddressthedetailsof howaspecificinformalproofwilllinktoaformalproofthatexplainsitsrigour. Thatis:

(Content) Toshowhowthecontentofaninformalproofdeterminesthe structureoftheformalproof(s)itcorrespondsto.

Wewillseeinthefollowingsectionsthatdifferentversionsofthestandardview takequitesubstantiallydifferentapproachestothistask.

Aparticulardifficultythatneedstobeaddressedbythestandardview concernsinformaltechniques:

(Techniques) Toprovideanexplanationofapparently inherently informal techniques.

Themostobviousofthesewouldbetosetoutwhatistobesaidaboutdiagramsin proofs.Therearemultipleoptionsforthis,rangingfromdenyingthatdiagrams canplayanessentialroleinproofsatall,toexplainingwhichdiagramsare amenabletoformalisationandhow(see Brown1999,ch.3; DeToffoli2023).

Finally,sincethestandardviewisalsoattemptingtogiveadescriptive accountofhowmathematiciansjudgerigourinpractice,anotheraimthey haveistoaccountforthemechanismbywhichmathematicians agree onthe rigourandcorrectnessofinformalproofs:

(Agreement) Toexplainhow,inpractice,mathematiciansmanagetoconverge andagreeontherigourandcorrectnessofinformalproofs.

Itiscommonlytakenasoneofthevirtuesofthestandardviewthatitwouldhelp toexplainagreementamongmathematicians.Forexample,Azzounisays, “[M] athematicianshaveawayofagreeingaboutproofthatisvirtuallyunique (agreementofanysortamonghumansisalwaysasurprise,andalwayshasto beexplainedsomehow),andtheexplanationofthissurelyisthatsomesortof recognitionofmechanicalproceduresisinvolved.” (2004,p.103).

However,recentempiricalworkhasshownthatmathematiciansdosometimes disagreeonwhatcountsasavalidproof(Weber2008; Inglis&Alcock2012; Weber&Czocher2019)andwhatcountsasagaporerrorinaproof(Inglisetal. 2013; Daviesetal.2021).Thisdoesnotmeanthereisnoagreementtoexplain; onenotable findingfromthesearticlesistheimportanceofthecontextofthe

proofforevaluatingitsvalidity.Thedisagreementwasalsoelicitedbyasking aboutdifficultcaseslikediagrammaticproofsandcomputerproofs.So,by keepingthecontext fixedandchoosinglessborderlinecases,theremightstill behigheragreementamongmathematiciansthanresearchersinother fields.One mightalsopositthatthereissomethinglikelong-termconvergenceonagreement, sothateveniftherecanbedisagreementaboutvalidityaboutsomesteportypeof proof,overthelongtermmathematicianswillconvergeonagreement.Ofcourse, thesearealsoempiricalclaimsthatcanandshouldbetested.

In Section2.1,Igavesomeofthepurposesofhavingaconceptofrigourat all,butitisnoteworthythatthiswasnotthesameastheambitionsofthe standardview.Thestandardviewseemstobeinterestedprimarilyinasubsetof thebroaderusesoftheconcept,mostobviously Soundness and Verification, though Agreement linkstothesocialsideofmathematics.Ingeneral,the explanationforthisisthatthestandardviewleansmoretowardsthenormative questionofhowmathematicaltheoremsoughttobefullyjustifiedratherthan thedescriptiveclaimofmathematicaljustificationinpractice.

Bysettingouttheseaimsforthestandardview,wecanjudgeindividual componentsofthevariousproposalsagainsttheiraims.Forexample,thesimple “fillinginthegaps” abbreviationmodelwealreadysawhasproposalstoanswer Rigour, Correctness,and Agreement.However,wefoundthestoryfor Content tobelackinginimportantdetails,andtheanswerto Techniques wouldlikelyneedtorejectanything,likediagrams,thatcannotundergothe “fillinginthegaps” processeasily.

Withanumberofpossibleaimsforthestandardview,andaselectionof optionsforwhatitmightmeanforinformalproofstocorrespondtoformalones, itnowbecomesclearthatthereisnotreallyonestandardview,butinstead afamilyofstandardviews whichshareacommitmenttothegeneralideathat formalproofsexplainwhichinformalproofsarerigorous.In Sections3.4, 3.5, and 3.6,Iwillsurveythreeofthemostprominentproposedoptionsinmore detail,andlikewiseevaluatethemagainsttheaimsIhavejustconsidered.

3.4Hamami’sRoutineTranslations Letusbeginwiththeversionofthestandardviewsetoutby Hamami(2019) HamamiclaimsthatheisgivinganexpositionofthestandardviewasunderstoodbymostmathematiciansandfollowingtheideasofSaunders MacLane (1986) andthecollective Bourbaki(1968) group. 17 Forexample,hequotes themasalreadydefendingsomeversionofthestandardview:

17 ForadiscussionofthesocialdynamicsoftheBourbakigroup,see Barany(2020).

AMathematicalproofisrigorouswhenitis(orcouldbe)writtenoutinthe fi rstorderpredicatelanguage L 2 ðÞ asasequenceofinferencesfromthe axiomsZFC,eachinferencemadeaccordingtooneofthestatedrules. To besure,practicallynooneactuallybotherstowriteoutsuchformalproofs.In practice,aproofisasketch,insufficientdetailtomakepossiblearoutine translationofthissketchintoaformalproof.(MacLane1986,p.377)

Inpractice,themathematicianwhowishestosatisfyhimselfofthe perfectcorrectnessor “ rigour ” ofaprooforatheory iscontentto bringtheexpositiontoapointwherehisexperienceandmathematical fl airtellhimthattranslationintoformallanguagewouldbenomore thananexerciseofpatience(thoughdoubtlessaverytediousone). (Bourbaki1968,p.8)

Hamamidescribeshowthestandardviewwillhaveanormativeand adescriptivecomponent:thenormativecomponentwillgivetheidealof howaproofoughttoberigorous,while thedescriptivecomponentwillpick outhowjudgementsofrigourareactuallymadeinpractice.Hearguesthatthe conditionthataninformalproofshouldbe “ routinelytranslatable” into aformalproofprovidesausefulmiddlegroundbetweenthesenormative anddescriptiveparts.Theideaisthatr outinetranslatabilityisaweakenough conditionthatproofscanmeetitinpractice,butnonethelessmaintainsthe strongconnectiontotheidealofformalderivations.Hisproposalisthat advocatesofthestandardviewhaveanimplicitconceptionofthemechanism forjudgingrigour,withreasonsforthinkingtheywillsucceedinidentifying whenaproofconformstothenormativestandard.The “ conformitythesis ” is Hamami ’sclaimthateveryproofthatis “descriptively ” rigorousinpractice alsosatisfi esthenormativeidealofformalrigour.Inotherwords:thepractice ofrigourconformstotheidealviaanimplicitlyunderstoodmechanismof formalisability.

Hamami’sprimarycontributionistogivespecificationsofwhatthedescriptiveandnormativeaccountsofrigourareforhisversionofthestandardview,18 andhowtheyconformtooneanother.Letustaketheseinturn.

Forthedescriptiveaccount,thegeneralideathatHamamiproposesisthat informalproofsinvolvesequencesof “higher-level” inferencepatterns.These kindsofinferencesareacquiredasonelearnsmathematics.Onebeginswith basicknowledgeofmathematicalstatementsandsimple,obviousinferential moves,thenproceedstocumulativelygainknowledgebyprovingmorethings, andrecognisingmorecomplicatedhigher-levelinferencesasacceptableby

18 Hamamiclaimstobemerelyexplicatingthestandardviewasitiscommonlyheldbymathematiciansand fillingoutthedetailsimplicitintheworksofBourbakiandMacLane.Idon’tthinkthis givescredittothesubstantialadditionalideashebringstothisdebate.

verifyingthattheymerelyabbreviatesomelonger-establishedpatternof inferences.19

Forthenormativeaccount,Hamamiattemptstosetoutwhata “routine translation” is,andtogiveapreciseinsightintohowitwillproceed.Hisview isthattheroutinetranslationisbestunderstoodascomposedofthreestages.The firststagetakesaninformalproofand fillsindetailssothattheinferencesuse higher-levelinferencerules.Thesecondstageunpacksthosehigher-levelinferencerules,fullybreakingthemdownintothemorebasicinferencesthatthey abbreviate.Thethirdstagetakesthesequenceofbasicinferencesandformalises itintosomeformalsystem.Importantly,Hamamiclaimsthatthisprocedureis routineinthesensethatitisalgorithmic,mechanical,andautomatic.

Finally,theargumentfortheconformitythesisusesthecentralroleofhigherlevelinferencesinboththedescriptiveandnormativeparts:Hamami’sideais thatadescriptivelyrigorousproofwillbemadeupofhigher-levelinferential moves,forwhichtheroutinetranslationwillsucceed,therebyreachingthe normativeideal.

Intermsoftheaimsoftheaccount,Hamami ’sversionofthestandardview isclearlymoresophisticatedthantheoriginal “ fi llinginthegaps ” account. Whileheisstilladdressing Rigour and Correctness ,thedetaileddescriptionoftheroutinetranslationhegivesisalsoaddressing Content . Furthermore,theideathatmathemati ciansimplicitlyrecognisethemechanismbywhichrigourisjudgedisintendedtoaddress Agreement ,becausethe mechanismis,presumably,sharedbymathematicianswhoareabletomake therelevantjudgements.Thequestionof Techniques islessstraightforward becauseitisnotobviousthatHamami ’saccountwillapplyandhedoesnot explainhowtodealwithcasessuchasdiagrammaticproofs.Thedescriptive accountcouldpotentiallybethesame:thatonebuildsupatoolboxof acceptablediagrammaticinferences cumulatively.However,onequick objectionisthatthisassumesthattheacceptableinferencesalwayscome fromthiskindofprocess,anddonotrelyonpreviouslyuntestedinferences thattakeadvantageofvisualelementsofthediagram,ratherthanbeing madeupofsmallerinferences.

3.5 InPrinciple Formalisability Anotherversionofthestandardviewistothinkthatrigorousinformalproofs arethosethatwouldbeformalisable inprinciple.Thatis,ratherthanthinking

19 Thisdescriptiveaccountissimilartothatgivenby Tatton-Brown(2023) whoalsothinksthat mathematicallearningiscumulativeandtherebyallowsustorecognisemoresubstantial mathematicalinferencesasrigorous,whilestillhavingthoseinferencesultimately “deductively grounded” informalcorrectness.

thereisaroutinetranslationfromarigorousinformalprooftoaformalderivation,theyinsteadrelyonthetheoreticalpossibilityofsuchatranslation. Prominentproponentsofthiskindofapproachinclude Steiner(1975) and Burgess(2015)

StartingwithBurgess,hebuildsontwogeneralideasaboutrigorous proof.The fi rstisthat: “ Aproofiswhatconvincesareasonableperson; arigorousproofiswhatconvinces[even]anunreasonableperson ” ( Burgess 2015 ,p.91). 20 Thesecondideaisthatrigorousinformalproofsarenotabout givinganabbreviatedversionofaformalproof,butinsteadareprimarily aboutconvincingothermathematiciansthatsuchaproofexists.Burgess referstothisprinciplefromHymanBass,whosays:

Thenotionofmathematicalproofisaprecisetheoreticalconstruct,butitis quiteformal,rulebound,andponderous.Mathematicianstypicallydonot producesuchformalproofs,butratherconvinceexpertcolleaguesessentially thatsuchaproofexists,thepresumptionbeingthattheconvictioncarriesthe beliefthatunderduressandwithsufficienttimesuchaproofcouldbe suppliedbytheproponent.(Bass2003,p.770)

Burgesssummarisesthisinsloganform: “ Aproofiswhatconvincesmathematiciansthataformalproofexists ” ( Burgess2015 ,p.91).However,this isnotadequatebyitselfbecauseitisrelevant how theconvictioncomes about.Beingconvincedcanhappeninnumerousways,suchasthrough experttestimonyorbrainwashing.Evenanunreasonablepersonmightbe convincedforthewrongreasons – giventheirunreasonableness,wemight expectthisevenmore – andcertainlyexperttestimonycanconvincepeople oftheexistenceofformalproofs.WhatBurgessisafteristhattheconvincingisn ’tofthisdefectivesort;thattheconvincinghappens intherightway. Hetentativelysuggeststhattherightwayforthisconvictiontocomeabout isbecausethestepssuppliedshow enough oftheformalproof: “ Whatrigor requiresisthateachnewresultshouldbeobtainedfromearlierresultsby presentingenoughdeductivestepstop roduceconvictionthatafullbreakdownintoobviousdeductivestepswouldinprinciplebepossible ” ( Burgess 2015 ,p.97).

InhisreviewofBurgess ’sbook, Pettigrew(2016) respondsthatitisn ’t aboutsupplyingenoughsteps,butaboutsupplyingtherightsteps.He observesthatanadvancedmathematicianmightonlyneedtoseeasingle trivialstepofaverydif fi cultprooftoconvincethemselvesthataformal proofexists,invirtueoftheirabilitytocomeupwithproofs,butthatcannot

20 BurgessascribesthisideatoMarkKac.I’venotmanagedtotraceadirectquotation,otherthanin hisobituaryby Thompson(1986).

betherelevantsenseofthe “ rightway ” tobringaboutconviction,because onlysupplyingatrivialstepdoesnotmakeforarigorousproof.Pettigrew proposesthatwhatismissingfromBurgess ’saccountisadistinction between ingenious and routinesteps .Aproofshoulddisplayallofthe ingeniousstepsandtherebyconvinceitsaudienceoftheexistenceof aformalproof: “ Arigorousproofisonethatconvincesitsaudiencethat thereexistsaformallyrigorousproofbyprovidingthosestepsinthe formallyrigorousproofthatitisnotsimplyroutinetoprovide ” ( Pettigrew 2016 ,pp.132 – 3).Theideaisthattheroutinestepsarethosethatonecan reasonablyexpectanothermathematiciantocomeupwithforthemselves, whileingeniousstepsmustbegiven.Therefore,toconvinceothermathematiciansoftheexistenceofaformalproof,oneneedstosupplythose ingenioussteps,butmaytaketheroutinestepsforgranted.

Asimilarlineofthoughtispresentin Steiner ’s(1975) accountofmathematicalknowledge.Hethinksthatonecangainmathematicalknowledgefrom aproofonlyifthatproofisinprincipleformalisable.To filloutwhat “in principle” meanshedeploysthethoughtexperimentofbeingabletoproduce aformalproofwiththeassistanceofahypotheticallogicianhelper.Most mathematiciansdon’tknowenoughformallogictoproduceformalproofs,so itcannotbeexpectedthattheythemselvescanproduceformalequivalentsof theirproofs.Steinersolvesthisbyimaginingwhatwouldhappeniftheywere pairedwithalogicianwhocouldproduceformalproofs.Thelogicianwouldbe abletohandlethelogicitselfandthedetailsoftheroutinesteps,whilethe mathematicianmustsupplytheingeniousandcreativepartsofthemathematical reasoning.If,inthehypothetical,thetwoofthemcouldproduceaformal derivationtogether,thentheinformalproofwouldbesufficienttoestablish themathematician’sknowledgeallalong.

The inprinciple formalisabilityapproachisclearwithregardto Rigour butunderspeci fi edwithrespectto Correctness .Afterall,itisnotobvious thatsupplyingenough(orenoughingenious)stepsofaproofissuf fi cientto guaranteeitsformalisability,norisitclearthatthehypotheticallogician canreallyunderpinanaccountofcorrectproofs.The inprinciple account seemstobypassthedemandof Content altogetherbecauseitdoesnotwant tospecifyatallwhataninformalproof ’scorrespondingformalproofis,let alonehowthetwoarelinked.For Techniques ,thisaccountrejectsany prooftechniquesthatare inherently informal,sincetheycouldn ’tbeformalisedeveninprinciple.For Agreement ,astoryisneededofhow mathematiciansconvergeonwhichproofsareformalisable inprinciple , thoughthesuggestionsofBurgessandPettigrewprovideanoutlineofhow thiscouldgo.

Oneofthemostinfluentialproposalsformakinginformalrigourdependenton formalproofscomesfromtheearlierworkofJody Azzouni(2004) onhis derivation-indicator view.21 Wehaveseenthe routinetranslations viewtryto specifyhowformalproofscorrespondtoagiveninformalproof,andthe in principleformalisability viewthatinformalproofsonlyneedtobeformalisable inprinciple.Incontrast,thederivation-indicatorviewisthatinformalproofsdo indicate correspondingderivations,butwithoutthemathematiciansneedingto knowhowthatcorrespondenceworks.Theseindicatedderivationsexplain thingslike Rigour, Correctness,andespecially Agreement,butdonotneed tobeknowntothemathematicians,norarethey fixedtoaparticularformalism.

Theoverallideaisthatformalderivationsareimplicitininformalproofs,in awaythatsecuresmathematicalrigourbecausethosederivationsaremechanicallycheckable,whichindirectlysecurestheinformalproofstoo.

Itakeaproofto indicate an ‘underlying’ derivation Since(a)derivationsare (inprinciple)mechanicallycheckable,andsince(b)thealgorithmicsystems thatcodifywhichrulesmaybeappliedtoproducederivationsinagivensystem are(implicitlyor,oftennowadays,explicitly)recognizedbymathematicians,it followsthatifproofsreallyaredevicesmathematiciansusetoconvinceone anotherofoneoranothermechanically-checkablederivation,thissufficesto explainwhymathematiciansaresogoodatagreeingwithoneanotheron whethersomeproofconvincinglyestablishesatheorem.(Azzouni2004,p.84)

Mathematicianscanagreeonrigorousandcorrectproofsbecausetheyare implicitlysensitivetowhichinformalproofsindicateformallyvalid,mechanicallyrecognisablecounterparts.Nonetheless,thisdoesn’trequirethemto actuallyknowwhatthoseindicatedderivationsare,whichexplainshowmathematicscouldfunctioninthiswaydespitethelonghistoryofmathematics beforetheinventionofformalproofsanddespitethemanymathematicianswho arenotabletoproduceformalproofs.

Theproposalthattheformalderivationsareimplicitandnotnecessarily knownbythemathematiciansthemselvesworksinpartbecausethederivations Azzounihasinmindarenot fixedtoasingleformalsystem.Instead,theycanbe foundacrossawholefamilyofalgorithmicsystems(withsometechnical caveatsthatwedonotneedtoexplorehere).Mathematiciansarenotboundto someparticularformalism,soneitherarethederivationsthatunderlieproofs.

21 Inmorerecentwork, Azzouni(2020)hasmovedawayfromthederivation-indicatorview towardsthe algorithmicdevice viewofinformalproofs.Whilethishassomefamilialrelationshiptothederivation-indicatorview,italsohassomesubstantialdifferencesthatmeanit explicitlynolongerfallsunderthelabelofthe “standardview” .

Furthermore,newtechniquescanleadtoneedingtheresourcesofdifferent formalsystems,andAzzouniseesmathematiciansas flexibleandfreetomove tonewformalsystemsthatcanaccommodatetheirneeds: “Onthederivationindicatorviewofmathematicalpractice,themathematicianisseeninsteadas gracefullysprintingupanddownalgorithmicsystems,manyofwhichheorshe inventsforthe firsttime” (Azzouni2004,p.103).

Thismeansthatinformalproofsthatmakeuseofmoremeta-levelreasoning arehappeninginahigher-levelsystemthatcanhandlethem.Azzouni’sexample isusinga “proofbysymmetry”,wherejustoneofseveralcasesisprovenin detailandtherestarearguedtofollowsymmetrically.Healsotakesthistoallow the flexibilityfortheretobealgorithmicsystemsthatareindicatedbydiagrammaticreasoning,allowingforananswerto Techniques.

Inotherpapers, Azzouni(2005, 2009)developsanovelaccountof “inference packages”,whichare “psychologically-bundledwaysofphenomenologically exploringtheeffectofseveralassumptionsatoncewithoutexplicitrecognition ofwhatthoseassumptionsare” (Azzouni2005,p.9).Theseworklikecognitive blackboxeswhichallowustocarryoutmathematicalmanipulationswithout havingtobeabletointrospectivelyknowtheunderlyingformaljustification,or eventorecognisewhichassumptionsarebeingmanipulated.Thatmathematiciansoftenuseinferencepackagestothinkaboutmathematicsaddstothe accountbyexplaininghow Techniques canseemsoinherentlyinformaland compellingwhilestillindicatingunderlyingderivations.Furthermore,it fills outhowindicatedderivationsmightsecure Agreement amongmathematicians despitethemnotknowingtheexactderivationsthemselves.

Overall,Azzouni’sderivation-indicatorviewdoeswellataccountingfor Rigour and Correctness,usingtheindicatedfamilyofderivations.For Agreement, mathematiciansaremeanttoagreeabout validitybecausetheirjudgementsare trackingtheimplicit,indicatedderivation.Meanwhile,bynotneedingmathematicianstobeawareofwhichderivationisindicated,theaccountcanaddress apparentlyinherentlyinformal Techniques andnotrelyonthemathematicians knowingsubstantialformallogic,whichisuncommonevennowandwasimpossiblepriortotherelativelyrecentdevelopmentofmodernlogic.Onethingthatis leftsomewhatunderspecifiedis Content:theindicatedderivationsaremeantto providetheultimatesourceofjustificationfortheinformalproofs,butitisnotclear howtheydosoorwhatthe “indication” relationamountsto.

3.7CriticismsoftheStandardView Sofar,wehavebeenassessingthemeritsofthevariousversionsofthestandard viewbythecriteriafrom Section3.3.However,thishastakenforgrantedthat

theviewsbroadlysucceedinthe firstplace.Thisisfarfromclear.Oneofthe majorcontributionsofthepracticalturninthephilosophyofmathematicshas beentochallengethestandardviewwithawideselectionofcriticisms.Inthis section,Iwillsurveysomeofthemostprominentonesandaddsomemoreof myown.Wewon’thavespacetogointomuchdepth,butthereadercanfollow thereferencesforfurtherdiscussion.

3.7.1NoFormalSystem The fi rstobjectiontothestandardviewistheabsenceofaspeci fi cformal systemunderdiscussion.Differentsy stemswillhavedifferentthingsthey canproveanddifferentwaysofprovingthem,sowhatsystemunderliesthe rigourofinformalproofsisfarfromani dlequestion.Iftheinferencesfound inaninformalproofarewarrantedbyoneformalsystembutnotbyanother, whatisthestatusofthatinformalproof?Thisquestionappliesatseveral levels.First,onemightaskwhatunderlyinglogicisbeingused.Thedefault assumptionwouldbeclassicallogic,thoughtheconstructivistsandproponentsofotheralternativelogicswouldr ejectthis.Evenwithinclassicallogic, onemustsettleonusing fi rst-orderlogic,somehigher-orderlogic,orsomethinginbetween.Onemustdecideabouttheacceptabilityofin fi nitary proofs. 22 Atthetechnicallevel,thesechoiceswillmatterastowhatcanbe formalisedandhow.Beyondthelogic,onemustsettleonwhichaxiomsare used.Again,thedefaultwouldprobablybethoseofZFCsettheory,which itselfcanbesupplementedwithall kindsofextraaxioms,butthereare alternativeproposalsforfoundationsofmathematicstoo,suchasthrough categorytheoryorhomotopy-typetheory.Again,thesewouldaffectwhat couldbeformalised.

Multipleformalisationprojectsareunderwaytousecomputer-checkingin mathematics,suchasinLean,Coq,theHOLfamilyincludingIsabelle,and Mizar.Theseallhavedifferentimplementationsofhowproofsarewrittenand howthingsareformalised.Ifthesuccessesoftheseformalisationprojectsare tobeusedtosupportthestandardviewbyvindicatingthepossibilityof formalisingmathematics,itseemsthatwemustacceptthatthesesystems arecapableofjustifyingrigorousproofs.However,thesesystemsareall idiosyncratictosomeextent,andtheproductofvariouscontingentprogrammingchoices,soitisunlikelythatthe yarereallyexplainingtherigourof mathematicalproofs.

22 Forexample, Rav(1999) and Azzouni(2004) disagreeonthismatter. Weir(2016) arguesthat allowingproofstobeinfinitaryisnecessaryforthestandardview.

Theproponentsofthestandardviewwouldpointoutthatthekeyfeatureof thesevarioussystemsisthattheyshouldcontainenoughstandard,everyday mathematics.Themanysystemsallprovelargelythesamethings,using mostlythesametools.AsAzzounimakesexplicitforhisderivationindicatorview,thedetailsoftheexactsystemarenotimportantsolongasit capturestherightinferences.Itcouldalsobethatanysystemis finesolongas itsatisfi essomelistofcriteria,thoughIknowofnosuchlist.Nonetheless,we haveseenthatthedetailsareimportantifthestandardviewistoexplain mathematicalrigour.

3.7.2IncompletenessandInconsistency OnelimitationonformalsystemscomesfromGödel ’stwoincompleteness theorems.The fi rstshowsthatanyconsistentformalsystemthatissuf fi cient toproveacertainamountofmathematicswillfailtobecomplete,meaning thattherewillbestatementsthatitcannotproveordisprove.Thesecond thenprovesthat,ifsuchaformalsystemisconsistent,thenthestatement thatthesystemisconsistentwillnotbeprovablewithinthesystem.Gödel ’s proofsinvolveusingacodingtoconstructaGödelsentence GF (relativeto aformalsystem F ),whichisprovablyequivalenttotheformulaexpressing that GF isunprovableinthesystem F .Thesentence GF willnotbeprovable in F ,onpainofcontradiction,butwillthereforebetrueofthesystem F . Priest(1987,ch.2),whowantstoarguefordialetheism – theviewthatthere aretruecontradictions – and,insupportofthis,thatmathematicsisinherently inconsistent,usesthestandardviewasamainpremiseofhisargument.Theidea isthatifonetakesthestandardviewseriously,thenrigorousinformalproof procedurescanbeformalised,andhencecanbeusedtogenerateaninconsistencyusingGödel’stheorems:

Forlet T be(theformalisationof)ournaïveproofprocedures.Then,since T satisfiestheconditionsofGödel’stheorem,if T isconsistentthereisasentence ’ whichisnotprovablein T ,butwhichwecanestablishastruebyanaïve proof,andhenceisprovablein T .Theonlywayoutoftheproblem,otherthan toacceptthecontradiction,andthusdialetheismanyway,istoacceptthe inconsistencyofnaïveproof.Soweareforcedtoadmitthatournaïveproof proceduresareinconsistent.Butournaïveproofproceduresjustarethose methodsofdeductiveargumentbywhichthingsareestablishedastrue.It followsthatsomecontradictionsaretrue;thatis,dialetheismiscorrect. (Priest1987,p.44)

Inmyownwork(Tanswell2016a),Ihavearguedthattheplacewherethis argumentbreaksisinadoptingthestandardviewinthe fi rstplace.

Aproponentofthestandardviewisthereforechallengedtoofferadifferent solution,ortoacceptPriest ’sconclusionthatmathematicsisinconsistent.

3.7.3UnformalisableproofsandFaithfulness Amajorstrategyforattackingthestandardviewhasbeentopresentproofs thatwouldappeartobeunformalisable.Ifthereexistsarigorousproofthat isunformalisable,thiswouldbeaco unterexampletothestandardview. Likelycandidateswouldbediagrammaticproofsorproofsthatrelyessentiallyondiagrams. 23 However,whilethesemaybehardtocapturein language-basedformalsystems,th ereareformalsystemsforcertain kindsofdiagramstoo,suchas Mumma ’s(2010) formalsystemfor Euclid ’sElementsand Shin ’s(1994) systems Venn-I and Venn-II .This suggeststhatrigorousdiagramscouldbeamenabletotreatmentby aformalsystemfordiagrams.Nonetheless, DeToffoli(2023) showsthat therearerigorousdiagrammaticproofsthatcannotbefaithfullytranslated intoformalcounterparts.

Likewise,recalltheproofby “Gestaltshift ” .Itmaynotbepossibleto capturefaithfullyreasoningthatreliesonsuchaswitchofperspective.24 However,theword “ faithfully” isimportanthere,becausewiththeresources offormallogicagreatmanythingsareformalisableinsomebroadsense,but intryingtounderwritearigorousinformalproofwewanttheformalisationto befaithfultothereasoningpatternoftheoriginal.25 Faithfulnesswillmean somethinglikepreservingthemainideas,structure,andmethodsoftheproof. Tothecriticofthestandardview,itmay beobviousthatatranslationshouldbe faithfulinordertosecurerigour,butfortheproponentthisrequirementcould beseenasunfairlyrestrictingthetoolsoflogicbysettinganebulousextra requirementontranslation.After all,whojudgesthefaithfulnessof atranslation,andbywhatstandards?26

23 Azzouni(2020)arguesagainstthestandardviewalongtheselines,witharecentreplyby Weisgerber(2022).

24 Thespecificversionwesawwasgivenasanexampleofanunrigorousbutcorrectproof,sothis suggeststhatthisexamplecouldberejected.However,thereisnoobviousreasonwhythere couldnotbearigorousproofbyGestaltshift.Eventheonewesawcouldbemademoreexplicit whilestillrelyingontheGestaltshiftasitsmainstrategy,anditisthismovethatseemstobe difficulttoformalisefaithfully.In SangwinandTanswell(2023) wealsolookattheprocessof translatingbackandforthbetweenalgebraicanddiagrammaticproofs.

25 Thesignificanceoffaithfulnessoftranslationsintheliteraturemightbetracedto Lakatos(1976) Forexample: “Alpha:Areyousurethatyourtranslationof`polyhedron’ intovectortheorywas a true translation?” (Lakatos1976,p.121).Iwilldiscussthisbookin Section3

26 Thisproblemisalsoconsideredby DeToffoli(2023) whorightlypointsoutthatidentity conditionsforproofsarehardtopindownandarecontext-dependent.

24 PhilosophyofMathematics 3.7.4KnowledgeandExplanatoryRedundancy

Amainlineofattackfrommathematicalpracticeonthestandardviewhasbeen epistemic,arguingthatformalproofsarenotneededtoexplainhowinformal rigorousproofsprovidemathematicalknowledge.Thatis:formalproofsare explanatorilyredundantintheepistemologyofmathematics.27

Rav(1999) listsvariousareasofmathematicsthatareacceptedasrigorous andproceedwithoutaxiomatisationorformalisationasanintermediary.28

Therefore,asadescriptiveaccountofhowrigoursecuresmathematicalknowledgeinpractice,itdoesnotsucceed.Thethreemoreadvancedversionsofthe standardviewwouldreplythattheirmodelsarenecessarytoexplainrigouras anormativeidealforproof,andthattheactualpracticesaretryingtomeetthis idealinvariousways.Nonetheless,otherliteraturechallengesthesesolutions.

Forexample,replyingtothe routinetranslations view, Weber(2023) givestwo examplesfromcomputabilitytheorywhereproofsaretakentoberigorousby themathematicalcommunity,butarenotverifiablebymathematiciansinthe wayHamamihassetout,norarethetechniquesdevelopedinthecumulative waythathedescribes.

Similarly, AntonuttiMarfori(2010) arguesthatthelackofformalisationsin mathematicalpractice,eitherinpresentingproofsorresolvingcontroversies aboutproofs,meansthatanepistemicaccountbasedonformalisationwould makemathematicalknowledgemysterious.Eitherthisleavesmathematical practice “lazyandunsuccessful” (AntonuttiMarfori2010,p.267)oritallows informalproofstotrackmathematicaltruthwithoutthepractitionersknowing how,whichmakesforanunconvincingaccountofmathematicalknowledge.

Pelc(2009) alsoarguesthatformalproofsmightbetoolongtoplayarole inmathematicalknowledge.Inpractice,formalisationsarelongerthantheir informalcounterparts.Pelcarguesthatforcomplicatedproofs,suchas Wiles ’sproofofFermat ’sLastTheorem,itisnotknownwhetherthe formalisationissolongthatitwouldeverbeveri fi able,evenifallthe resourcesintheuniversewerededicatedtothetask. 29 Therefore,formal

27 Besidesthoselistedinthetext, Buldtetal.(2008) usethisargumentasalaunchpadfor demandinganewepistemologyofmathematicsthatdoesnotrelyonthestandardview. GoetheandFriend(2010) alsogiveaversionofthisargument.

28 Thelistof “unaxiomatised” theories Rav(1999,p.16–18)givesnowlooksratherquaintbecausein theinterveningyearsalotmoreformalmathematicshasbeendone,andmanyofthelistedareashave beenformalisedandverifiedinsystemslikeLeanandMizar.Thisdoesn’tundermineRav’spoint, though,whichisthatthemathematicalpracticeswereperfectly fineandrigorouswithoutthose formalisations.

29 FreekWiedijkhasalisttrackingtheformalisationeffortsof100 “top” theoremsinvarious formalsystems,inanexercisetofollowdevelopmentsinformalmathematics(www.cs.ru.nl/ ~freek/100/).Funnilyenough,theonlytheoremthathasnotyetbeenformalisedinanyofthe mainsystemsisFermat’sLastTheorem.Thefactthattheother99haven’tseenthehumongous