Preface to the New Edition

The central argument of Horror in Architecture, when it was first published in 2013, was that “unprecedented” moments—and transitional ones— create monsters.1 This substantially new edition of our study attempts to expand and sharpen an exploration of this process: of how interesting times make interesting buildings. It is a fascinating and difficult subject, and not an easy one to wrangle into anything resembling a conventional academic work. A book that links horror to architecture, and to industrial modernity, affective history, and creatures from speculative film and fiction, should perhaps be condemned outright as monstrous. This is an inherent danger of interdisciplinary writing, which often runs afoul of differing fields’ biases and emphases. Among architects and architectural theorists, the fundamental importance of buildings, as sites of life and as thingsin- the- world, can be assumed. When we published a “crossover” study that was to be read by literary historians, genre fans, writers, and artists, we quickly saw the limits of this assumption.

Our modest paperback met with its avid supporters and also its discontents. Some in film and media, especially a few concerned with “spatiality” in horror movies, found our own theoretical concerns (typology, program, organization of plan and section, materiality, meaning, and misrepresentation) to lack urgency. Our approach contradicted a tendency in some regions of the humanities to view architecture as symbolic backdrop or outsize figural sculpture. Others recognized something more: a link from considerations of affect to physical objects and operations of form, in doubling and cloning, subdivision, distortion and disproportion, partial negation, and the like. Generous interlocutors in fiction, in the arts and visual culture, and in theater and curatorial practices responded with invaluable insights and correctives.

We found all the varied strains of reaction to be helpful as we considered how a new edition might take shape. We have substantially reworked the contents of the present volume to underscore what is at stake— that is, to make clear why architecture matters. We have also expanded on horror’s intimate relation to

the logics of advanced capital, a theme of the previous book; our discussion of this topic has been clarified, broadened, and supplemented with four new chapters. The result will, we hope, help to illustrate the fearful and perverse effects of moder nity while engaging broader issues of determination and autonomy in the built environment. Finally, we have expanded our typologies to explain further why these embody processes of genuine consequence, and not merely for those involved or invested in design practice.

It is worth noting that this reanimated text has had to adapt to evolving circumstances in the world at large. The past decade has been one of global upheaval, in politics and culture alike. This includes the advent of social media (now inseparable from the experience of late modernity and of horror in all senses), a planetary pandemic, the rise of illiberal populism, and a polarized, agonistic realpolitik between left and right. These events necessarily condition contemporary thinking in design and theory. A darker and more irrational spirit, powerfully ascendant, informs what follows.

These shifts, and an escalating sense of crisis, have had clear echoes in the realm of cultural production, close to our subject. A significant effect has been the so- called horror renaissance. Feature films are being made in greater numbers and for larger audiences, and are being distributed via streaming media as an original modality. There has been substantial debate around this increase in popularity. Explanations for it have ranged from universal psychoanalytic “needs” to the emergent historical conditions of advanced capital.2 Significantly, the field has been transformed by writers and directors of color, who have given new life to a genre that recycles its own tropes and clichés ad infinitum. While Asian studios took the lead in the first decade of this century, African American auteurs are now producing work that operates brilliantly as both speculative fiction and social critique, speaking to the present through its own frightening idiom. The films of Jordan Peele and Ali LeRoi, among others, have added much to what follows.

The past ten years have seen the rise of eco-horror as a fertile literary space of its own, particularly in the novels of Jeff VanderMeer, which imagine a universe of extraordinary exchanges between human and natural biologies and forms. The climate crisis gives heightened relevance to this genre, which exists also as a test bed for the imagination of organic-anthropogenic beings, environments, and relations. The subject is fraught but also wildly creative and surprising. We include in this new edition a chapter on insurgent natures, about vegetal and elemental anxieties. And romances.

Certainly, all that has transpired since 2013 suggests that horror is no less

relevant now than it was then. If anything, the tendencies that drive the production of our nightmares are rather more aggressive and exaggerated. These exist not at the fringes of reactionary irrationalism—it is not the “sleep of reason” but the all- too-aware strategizing of productive rationalities that produces monsters. And so we offer what follows . . . a book for unprecedented times.

This page intentionally left blank

Introduction

You have always been a frightful mirror, a monstrous instrument of repetitions . . .

Julio Cortázar, Hopscotch

Sublime Horror

Why spend time on horrifying things? Antonio Rocco, as early as 1635, argued that we should look at them because they are instructive. And because the opposite, anodyne beauty, contains a dangerous surfeit of sweetness.1 Deviance teaches; charm will make you sick. Rocco claimed that horrors in particular— putrefaction, decay, distortion, and dissymmetry, among others—are sites of fertility, change, and invention.

This is a book about horror in architecture. We explore discomfiting buildings and urbanisms, “authored” and non, that may be understood by analogy to deviant and fearsome bodies and beings from popular history. These span from pre- to postmodernity and are organized into typologies or tropes—identifiable regions along a spectrum of morphological/anatomical deviance or monstrosity: doubling, reiteration, disproportion, formlessness, shifts of scale, excess parts and openings, solidity, and others. Such works are not necessarily bad, although some may appear to violate good taste. The examples that follow have been selected, rather, because they are interesting—and because they are highly suggestive in considering possible futures.

Horror in the built environment is an urgent subject. As we will see, its emergence is immanent in the project of the modern. It closely shadows the disconcerting scalar and typological evolution of our cities, as well as the rise of economic and social logics that put the building, as a category of object, into crisis. At the same time, the unique character of horror is increasingly relevant in what we might call an “age of affect,” within an emergent politics of the sublime that poses the

ecstatic and the shocking as alternatives to older Enlightenment values. Horror is important because—as an intellectual-affective tradition and a sphere of cultural production—it is effective in queering the norms of design practice. Horrid buildings deserve consideration because their violence is productive. They represent a variety of Nietzschean operation. Their deviant physicality opposes the creep of reification, of assumptions of objectivity and realism that mask a worrying order of things. In their place, a dark or “paranoid” ontology emerges.

This is not least because horror pushes against the bounds of the thinkable. The horrible, like the mad, presents the world not as it is but as it might be. It is utopianism without utopia, transformation without telos. It speaks of the present in the conditional tense. Through inversion—playing the fool—it says that which cannot be said. Our architectural examples are deeply uneasy with respect to the aspirations of contemporary design, with its patterns, parameters, and diagrammatic postures. The inheritance of sublime terror is not nearly so elating, or so beautifully aloof. Horror is one by-product of modernity and thus mimics its advanced forms—evolving with them. But it remains a dark mirror, an unsettling or ungrateful fellow traveler. It reverses, while sharing, formal characteristics.

This is due, in part, to a unique historical ambivalence. Horror is an aesthetic category that has traditionally been a site of profound skepticism about the merits of the aesthetic itself. From Roman times through the early nineteenth century, it was posited as a quality distinct from either beauty or ugliness.2 For Immanuel Kant, and for the romantics, it was an element of the sublime, experienced for spiritual and didactic benefit—a mode of feeling that bypassed the eye, skirted rationality, and addressed our inner nature. The terrible was one form of sublimity, alongside the noble and the splendid. In the former camp were objects that “arouse enjoyment but with horror.”3

For Kant, this gravity stood in opposition to beauty, which was a more superficial thing. In its simplicity and greatness, the sublime “moves.”4 Longinus, an originator of the concept, claimed that it tears up facts “like a thunderbolt.”5 Such an effect is superior precisely because it need not engage the faculties of persuasion. It is a sensation; when sublimity strikes, in the manner of pain or mortal fear, we simply know it to be true.6 In the eighteenth century, Thomas Reid noted that this mode of communication “carries the hearer along with it involuntarily, and by a kind of violence rather than by cool conviction.”7 Indeed, this wild affect is uncool. It is a site of swooning, of spiritual overpowering, of renewed commitments.

Horror is also a slippery fish. The great works on the subject continually insist upon its illuminating power, the value of clarified affect. In its wake, we will feel

and we will know. But know what? For Kant, the “rigid” and “astonished” sensation revealed nothing less than the dignity of humanity itself. Experiencing the sublime was an ethical operation and would spur one toward noble action. This was not an unheard-of idea. The British writers of moral sensitivity and improvement, such as the third Earl of Shaftesbury and Lord Kames, likewise proposed that there were objects in the world capable of bettering their observers. For others, sublimity clearly invoked the religious. Erich Auerbach, for example, thought that Dante’s description of the striding deity who “passed the Stygian ferry with soles unwet” succeeded in viscerally communicating the power of divinity.8 Horror, as its acute manifestation, is the shadow of the metaphysical moving across the waters. In a word, it is God.

Or a form of God. But a rarefied and perverse one, occupying a moment in which the tidy beauty of nature wears at the seams, and the unruly side—a divine excess—expresses itself. This announces its presence in the impenetrable dark tangle of the valley floor, in split and sundered trees, in the mountains “unjust” and “hook- shouldered,” and within the nimbus pregnancies of stormy skies. In the two centuries following Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux’s 1674 translation of Longinus, a godly surplus was felt in the appreciation of a “wild element, . . . something different from regularity.”9 This was famously true for Jean- Jacques Rousseau, hence his heroic standing among the French romantics. But it was more commonly the taste of English writers such as John Dennis and Thomas Burnet, who caught glimmers of such ferocious power in art more generally.

This nature was not the charming pastoral of the previous century, but something appalling. In 1753, for example, Dr. John Brown wrote of Keswick in the Lake District that its

perfection consists of three circumstances: Beauty, Horror and Immensity united. . . . But to give you a complete idea of these three perfections, as they are joined in Keswick, would require the united powers of Claude, Salvator, and Poussin. The first should throw his delicate sunshine over the cultivated vales. The second should dash out the horror of the rugged cliffs, the steeps, the hanging woods, and foaming waterfalls; while the grand pencil of Poussin should crown the whole with the majesty of the impending mountains.10

Similarly, Thomas Gray wrote about a 1739 visit to a “monstrous precipice, almost perpendicular,” which contained within itself “religion and poetry.”11 Joseph Addison famously remarked that the Alps overtook him with an “agreeable type

of horror,” as he absorbed “one of the most irregular mis- shapen scenes in the world.”12 Burnet likewise praised those natural vistas that were “ill- figur’d” and “confused.”13

Again, the emphasis here is not on the aesthetic so much as on the sensational: the eye becomes, in an actual sense, the window to the spiritual interior. In his influential article on the picturesque, Edmund Burke praised the effect of “sublime horrors,” which lead to a condition of astonishment—a “state of the soul in which all emotions are suspended.”14 In contrast to beauty, this involves physical pain; it is aesthetics made neural. Beauty is more closely related to ugliness. As the conservative philosopher was quick to point out, these may share formal characteristics, such as proper proportion. But the stupefaction of fear emerges from an alien matrix of feeling that permits no meaningful comparison.

For Burke, the agonizing presence of horror is quickly converted to pleasure. As we realize we are not in actual danger, shock is sublimated in relief. In this sense, the phenomenal arc of the sublime here resembles Kant’s. The ache, for the idealist, is dispelled via the dignity of the mind, which in the moment of extremis recognizes its own power. This formulation oddly shadows Sigmund Freud’s explanation of laughter: it is “cathexic” energy that builds up anxiously, only to be released in a variety of exhalation. Aristotle had already theorized such an effect in his Poetics, in a rather similar image of catharsis. Fear (eleos) is one emotion thought to be provoked by literary art, and also ritually ejected in a burst of social delight. Such an idea might help to explain the proximity of comedy and fright, as in the early American films The Cat and the Canary (1927) and The Last Warning (1929) and later in the Scream franchise (since 1996).

The experience of modernity has made these affective matters yet more turbid. Since the passing of its romantic heyday, horror appears inseparable from mass media. It seems mostly to have been exiled to the titillations of low culture. It has become that most mediocre of things, a “genre”: an area of production ostensibly below the threshold of seriousness.15 This divestment takes place against a backdrop of desacralization, the creep of the banal, and the routinization of charisma. Or, at least, the eviction of myth to newer quarters. Theodor Adorno, for example, denied the continued existence of fear in art. Such an expectation was atavistic, the hallmark of a lost, enchanted age. It survived only as a feeling of discomfort, inherent in the repulsion of ugliness. The Frankfurt School theorist even rejected the kitsch character of those popular products— such as the antiwar protest songs of the Vietnam era— that attempted to “take the horrendous and make it somehow consumable.”16 For Adorno, the horrible was something “out there,” in the violence of imperialism, Auschwitz, and the irrational.

The ache of an increasingly disenchanted world has doggedly haunted this discourse for centuries. It was certainly felt by the romantics. In the work of Burke, as well as Lord Byron and Caspar David Friedrich, we are already aware of a groping for intensity of experience. Like the famous Claude glass that was used to make picturesque landscapes look more picturesque, this aspiration was ridiculed in its own time as dangerously overripe, as a frequently forced attempt to stage emotive experiences.17

The romantic courtship of sensation was likewise powerful in a society less frazzled than our own. In contemporary culture, horror becomes merely one source of shock among many. The effects of the sublime must compete with the alarmism of sensationalist news, video games simulating mass killing, ubiquitous pornography, “venti” coffees, and militarized foods—like potato chips designed to deliver one hundred decibels into the inner ear for an “extreme” eating experience.18 Theorists of the modern condition have understood such titillation as a desensitizing force, causing a “blasé attitude.” This phrase is Georg Simmel’s, and refers to the stupor that arises from the constant jostling of urban life.19 It is a sickness that leads the overstimulated to seek further stimulation. Stephen Eide, in his close reading of Alexis de Tocqueville and John Locke, locates the origins of the problem of restlessness even prior to the explosion of the metropolis, as a central pathology of liberalism itself.20 Within the Tocquevillian narrative of Peter Carey’s novel Parrot and Olivier in America, a rocking chair epitomizes the plight of “agitated” republican subjects. Unsettled by social and financial mobility, they cannot sit still, and must calm themselves through neurotic repetition: motion that simulates movement.21 For its critics, this society produces a strain of traumatic automatism, which Adorno identified in pop and jazz “standards” on endless replay.22

Perhaps for this reason, horror in the contemporary appears fated to a state of mediocrity. The emotion is evacuated of high- cultural or philosophical import, and when employed for “serious” art or for credible culture—as in the films of Andy Warhol, Lars von Trier, and Quentin Tarantino, or in Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)— can only be rehabilitated as camp.23 As an inherently affective and graphic mode of communication, horror necessarily flirts with kitsch and falls prey to a problem avoided by the abstract arts of the twentieth century. At least, if we believe Clement Greenberg and Gillo Dorfles in their contention that bad taste grows from sentiment and representation.24 This “vulgar” tendency leads to exile, to the spheres of Hollywood and pulp cinema. The venerable sensation has become inseparable from the calculus of commercial spectacle.

Herein lies a paradox central to this book. While horror increasingly attends the experience of modernity—and nowhere clearer than in architecture—it has been largely banished from the mainstream of prestigious cultural production. Certainly, it remains close, as a kind of dodgy fellow traveler. Moreover, it appears not as its own theorized entity, but as a spectral eminence: a secondary, shadow- or countercultural sensibility that is overwhelmed by discourses of progressivism, positivism, and transcendent abstraction. We feel its critical chill in the work of Kurt Schwitters, Hannes Meyer, and those who likewise expressed the anxieties of the early twentieth century. Or, more recently, in the iconoclastic portraiture of Francis Bacon (see our chapter “Distortion and Disproportion”). The sublime went “underground,” to reappear in Gordon Matta- Clark’s vivisectioned houses, or in Vito Acconci’s audible masturbation beneath the floorboards of the Sonnabend Gallery.25

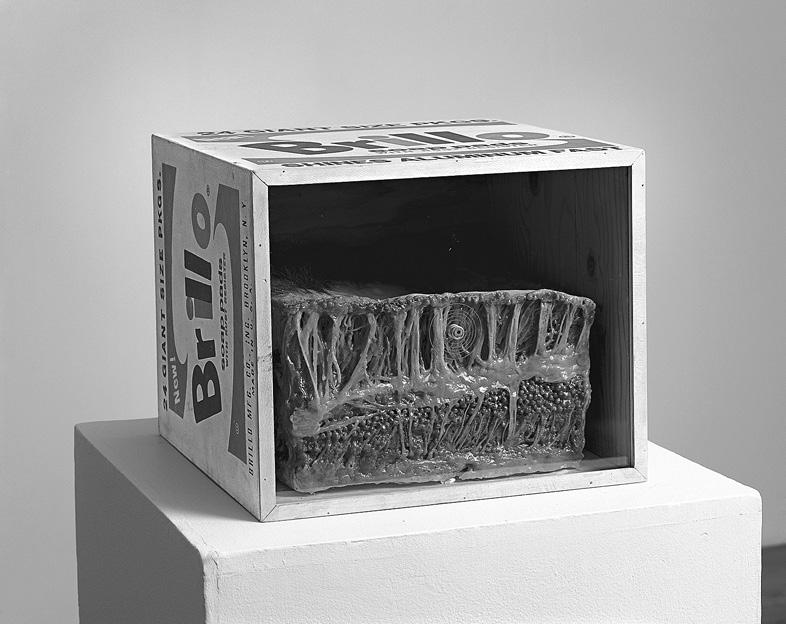

While terror and the uncanny may be highly abstract—a vaporous or creeping unease—horror is more commonly literal. The artist Paul Thek perhaps best expressed this sensibility, using latex casts to stage contrasts between the “finish- fetish” of midcentury art and chunks of meat and bone. Thek famously rereappropriated the icons of Warhol and combined them with simulated butchershop cuttings. In the slyest example, a Brillo box is laid on its side to reveal a kind of spinal flap in its hollow underbelly.26 This asserts an explicit fleshliness lurking within works of minimalism and pop art, and by extension in the commodity and its fetishism. It makes use of a vulgar technique, of gore as it would be modeled by a B-movie studio, and intrudes into the rarefied atmosphere of commercial iconography and its seizure by refined culture.

The staging of horror, as a recurrent social scandal of the modern, frequently operates via Thek’s method: a paradoxical effect that produces the literal, as bodily substance, alongside a certain trespass of epistemological limits. We might think, for example, of the Sex Pistols: a threatening and incomprehensible physicality, ritualized through sputum, vomit, blood, piercings, and “senseless” violence. The reification of the pop product, its resolution into an autonomous and objective reality, is resisted through a tactical incontinence.27 Importantly, this embodies a resistance to this process, which grows from deep unease regarding the power of objects in the current dispensation. Here, the consumable is continually juxtaposed with a biophysical substrate. It is a most vulgar kind of materialism, which reorients one to the notion that what exists is not necessarily what could be.

This echoes in the output of some contemporary British artists, who also fill their abstract containers with meat and viscera. Examples include Damien Hirst’s installations of rotting or cross- sectioned creatures in technical cham-

bers that resemble the architecture of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House (1951). These are flooded with chemicals or fetid air and provide a foil to the gore—like the glass freezer that preserves Marc Quinn’s Self (first produced in 1991), a bust cast from his own blood. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, critics have charged that the atmosphere of horror devalues the work. Such products have often been dismissed as expensive juvenilia.28 Even Hirst himself has claimed that the shark in his tank was unnecessary; the formaldehyde was enough.29

But there is more. In the subcultural sensibility of horror, suspicion of the object—as an example of commodity logic—is matched by a corresponding distrust in knowledge. Even in its most apparently debased expressions, there remains an unsettling power of epistemic rejection. This is diametrically opposed to the power claimed by Burke et al.: that is, an affective shortcut to truth. The

Paul Thek, Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box, from the series Technological Reliquaries, 1965. Wax, painted wood, and Plexiglas, 14 × 7 × 17 inches (35.6 × 43.2 × 43.2 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with funds contributed by the Daniel W. Diedrich Foundation, 1990. Copyright Estate of George Paul Thek. Photograph: D. James Dee. Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York.

ultimate import of the slasher or creature film seems to be a profound commitment to indeterminacy that is clearly in contrast with detective stories (another important, and often seedy, modern genre). As literary critic Franco Moretti tells us, the police “procedurals” are all about restoration. The world is disordered and then put to rights. The message of such fiction is that there is a force, amoral or pericriminal though it may be, that does the work of certainty: killers are found, motives are unearthed.30

Horror movies allow no such positivism. Their outcomes are ambiguous, at best. The great cliché is the killer or monster rising from the grave for one last tweak before the credits roll. The significance is perpetual derangement, and this is why— financial motivations aside—a “franchise” always seems to produce endless sequels. There is no search for truth through shock, and no desire for ethical restitution. The fan base is a fringe that identifies with violence and the supernatural, as well as a growing mainstream audience in pursuit of increasingly extreme experiences. No progressive end is served by the “torture porn” of Hostel (2005), the Saw series (2004–present), or The Human Centipede (First Sequence, 2009). And there is no greater certainty, moral or otherwise, to be found in works that aim for higher levels of artistry, such as David Fincher’s Seven (1995) or Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill volumes 1 and 2 (2003, 2004). Even the social satire of Candyman (1992, 2021) and Day of the Dead (1985), which smuggle commentary beneath the splatter, represents no singular message.

Horror, as a spirit of negative counterdiscourse, would thus seem totally contrary to the Geist of modern life. Does it still speak to our cultural moment, then—or are we truly postromantic? We argue that, despite its diminished status, this much- vaunted and much-maligned affective complex is as relevant as ever. If Naomi Klein is to be believed, it has emerged—in the figure of emergency—as the central force in a novel economic, political, and social order. In this form, horror functions in the service of intimidation and pacification, becoming a weapon of consensus. Its use gives rise to a collectively sanctioned state of sovereign “exception,” in which corporate and national powers expand in the name of security. The continual threat of destabilization, of chaos and anarchy, justifies the incremental seizures of the public sphere by capital and its official facilitators.31 The excesses of the second Bush presidency and of the Trump administration are perhaps the most convincing evidence put forward for this theory. Klein’s argument is rather the opposite of Horkheimer’s or Adorno’s: the world has not been banalized or subsumed within a “one-dimensional” culture of co-optation. Instead, extreme forms of heightened, and “unprecedented,” experience are the new currency of authority.

In this politics of the sublime, horror has been discursively institutionalized as “Terror,” in the official sense of the word.32 Here, too, it dwells in the public memory. In many ways, the events of 9/11 represented the very apex of the picturesque— the sublimity of great height and the epochal imagery of fallen civilizations: the hubris of Babel, Oriental siege, Rome burning, acts of God, birds alighting moments before catastrophe, and so forth. Cameras showed clouds like those in J. M. W. Turner’s 1817 painting of the eruption of Vesuvius, rising in a vortex to block out the sun. Fragments of the towers’ façades resembled a hypertrophied Tintern Abbey. Terror transmits a Burkean experience, a messianic and transformative violence, followed by an unquiet soul. Failure of abstraction was also an effect; the envelope of multinational capital was peeled back, and its contents were disgorged. The aerie of finance opened, and what fell out were not equations but a cascade of paper, dust, metal, plastic, and other.

Lastly, this historical development has proceeded alongside—and been intertwined with—a general reemphasis on affect in the broader culture of the present. This has asserted itself through a variety of anti-Weberian manifestations: from charismatic religion to academic theory appealing to redemptive emotion to “experiential environments” and material effects in the built environment that have added sensational optics to the products of the architect. Such emphases suggest the extent to which the Enlightenment project of rationalist knowing has fallen into a moment of crisis.33 At the least, it is losing out to a neoromanticism in which feeling is believing. The lingering force of the sublime is an assumed purchase on our souls. This has long been thought to congeal, to realize, things out of reach: the spirit, natural laws and essences, authentic divinity, and human dignity.

Deviant Anatomy

With the present work, we enter into a fraught affective- theoretical field—one caught in a nearly impossible contradiction between the experiential and the taxonomic. Since the early days of the gothic in fiction, attempts have been made to parse what is rightly a spectrum of emotive potential. Ann Radcliffe, famously, distinguished between terror and horror.34 Where the former is more akin to anxiety or apprehension, the latter involves the admixture of fear and revulsion created by an encounter with the object of fear. As a corrective to Burke, Radcliffe associated terror with the sublime, whereas horror involved only dulling and paralysis.35

The unheimlich (discussed in “Doubles and Clones”) is yet another significant variant. It is by convention more akin to terror—existing as an anticipatory

unease, and without the direct and shocking encounter with the violent or the supernatural.36 Freud defined this in a manner that is at once exact and open to myriad manifestations: as the realization that something close is, in fact, deeply alien. The resulting sensation, explored by Anthony Vidler in The Architectural Uncanny, is closer to “creep”: a despair or discomfiture growing from the deep conviction that things are not as they should be.37 There are ghosts and specters in Rudyard Kipling’s stories, for example, that instill in their victims a kind of purified melancholic experience. This is absolutely unheimlich, but it does not evoke horror in the proper sense.38 This is likewise distinct, as Lincoln Michel has pointed out, from straightforward repulsion, or the “gross-out” (in the language of Stephen King).39

Such distinctions are instructive, and necessary—but attempts at taxonomy quickly encounter problems in any analysis of the architectural. Without doubt, these terms are used variably, and with a lazy interchangeability, in fiction and in discussions in popular and academic media. But the situation becomes more complex when we engage objects of horror and the often-muddled sensations of experience. A valuable contribution of affect theory is a renewed care for how feelings are experienced and classified, as well as an attention to their ineffable and indeterminate aspect.40 Certainly, there is a “creep” to the unheimlich that is distinct from anticipation, anxiety, paralysis, or revulsion. But just as these may be felt singularly, they can be confused or combined in a common moment. Moreover, as these undergo cultural mediation, the differences are yet further muddied. There is obviously a desire to court fear as thrill or enjoyment, as well. This impulse would appear to drive the popularity of scary films, haunted houses, and other non-life- threatening experiences that lie within the broader penumbra of the frightful.41 In what follows, we maintain a distinction between terms, while acknowledging that more than one species of adverse sentiment is likely to be at work in reactions to the built environment as a messy perceptual matrix.42

The point of architectural horrors is not that they necessarily revolt or mortify us. Some are genuinely frightening. For example, the images of dilapidated buildings in Detroit captured by photographers Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre are chilling both for the buildings’ distorted appearance and for the human implications of their ruin.43 Other buildings, such as the Tianzi Hotel in Langfang, China, are alarming and amusing at the same time. In what follows, we feature numerous examples, past and present, disturbing and lovely, crude and sophisticated (and sometimes both). In true eighteenth- century style, we choose to divorce these structures from boring and unhelpful judgments about their beauty or ugliness. Some are ugly, to be sure. Some are achingly beautiful. But all embody

the possibilities of deviant architecture as an opening into new worlds of form, composition, space making, program, and hierarchy.44 Following Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror, we understand such “abject” objects to defy fixity and comprehension, because their very logic is to repudiate rules. Theirs is a condition of continual ontological and epistemological scandal and transgression.45 But we make no assumption that a uniform reaction of revulsion, or shock—or any other affective cognates— will necessarily follow. Instead, we look for horrifying potential: for those buildings, and aspects thereof, that have an identifiable capacity to cause unease.46

But such potential must exist somehow in form, as an aberration—in the fact of being aberrant with respect to a norm. Horror finds this in the monstrous. In our typologies, we look to the legible compositional matrix of architecture itself: forms, materials, conventions or expression, and inhabitation and use. The buildings that possess this disconcerting power are those that are, in fundamental ways, deviant. In the physical, be it anatomical or architectural (or both), such deviance appears as monstrosity.

This follows classic tropes of abomination, reaching back to François Rabelais and before: mismatched limbs and morphemes, transgressions of the line between natural and nonnatural, elements out of place, crossed borders and cultures, inappropriate intimacies.47 In these wretched examples, the boundary between subject and world, self and other, does not coincide with the limits of the body. Rather, bodies may include foreign objects, as in Pantagruel’s image of the drunk intersected with his barrel. Or they may be horribly incontinent, with restless pieces that invade their neighbors in the crepuscular hours.48 These can appear unnatural, or ugly. But they are also creative and exceedingly energetic.

Such bodies have been imagined differently at various moments. Curiously, aberration and “monstrous” exception have not always implied evil or ugliness. As Hillel Schwartz quotes Montaigne: “What we call monsters are not so to God, who sees in the immensity of His work the infinity of forms that He has comprised. . . . There is nothing that is contrary to nature.”49 There are those who have seen the internally heterogeneous body as a sort of divine emergence, the upwelling of new design— who have not mistaken convention for loveliness, and vice versa. Schwartz, for one, notes the changing interpretation of the monster from a “marvel, an amazing thing under God’s heaven,” to the “monster as multiplicity, a polyform being nursed by extravagant Nature.”50 Likewise, the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote in “Pied Beauty” of the blessed character of the polyglot. Like Montaigne, and later Jacques Derrida, Hopkins credited God with “dappled things,” for all “counter, original, spare, strange.” Kant, similarly, claimed that

“multiplicity is beauty.”51 The unique and the multiform merely show the breadth of the Lord’s creation.

While it has not been simply equated with ugliness or perversity, deviant anatomy has usually signaled the exceptional. The notion of physical aberration has been associated with figures of power, with kings and deities. Horrid forms were a medium for conceptualizing superhuman sovereignty. In the medieval church, for example, some morphological experiments were even applied to the godhead. Artists tried to tackle the problem of the Trinity, of a god that is simultaneously three and one. This resulted, briefly, in the Tricephalous Christ: a multiheaded figure conjoined at the cheek.52 Celtic Christianity was likewise subject to odd compromises, centuries of secret accommodation with Druidic and “folk” religions.53 The Anglo- Saxon crucifixion depicted Jesus and King Arthur intersected with a tree. Here, brambles replaced the cross; tangled branches pierced the flesh like nails.54

As with the superhuman, the anomalous body has provided a medium for pondering the boundaries of the species, and those of the individual subject. This frequently has to do with the horizon of humanity, blurring the demarcation between animals and ourselves. This is, of course, a classic of carnival: bestial masks and behaviors, creatures dignified with human titles and honorifics, dogs walking on their hind legs. The mythical spawn of classical antiquity— fauns, the

Tricephalous Christ, Salisbury Cathedral. Courtesy Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Copyright The Courtauld.

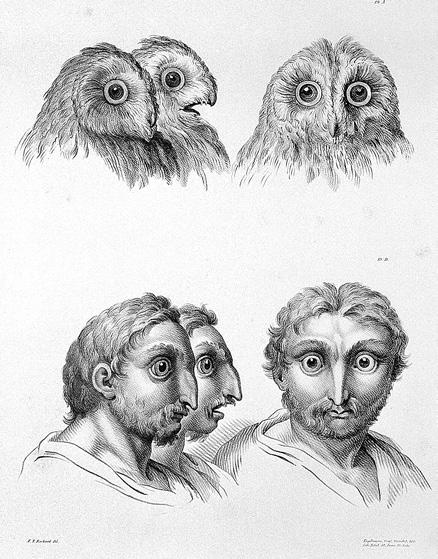

Charles Le Brun, comparison of human physiognomy with that of owls, illustration from a lecture delivered to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, Paris, 1671. Wellcome Collection.

Minotaur, lycanthropes, nymphs, and sylphs— commonly straddled this uneasy interface. Others combined different beasts into a single being, or multiples of the same in a conjoined being, like Cerberus.

This last, when applied to the human, provides another major strain of horror. The European folk traditions included numerous many-headed giants and ogres, multiple selves forced into the unbearable intimacy of a common body, with shared hungers and movements, hearts and assholes. The nightmare of the partial individual, who must share core elements of his subjectivity with others, was a contravention of the territorial anatomy—at least in those cultures where liberal humanism was on the ascent.

The deviant might be considered an “experimental subject,” a mode of being that articulates human experience under shifting circumstances. The mania becomes acute when the pace of history, for whatever reason, appears to be abnormally brisk. No coincidence, perhaps, were those outbreaks of freaks among the Victorians, during the so- called Age of Revolution, or more recently in an era of “translocalization,” when the geographies of wealth and connection have come to seem ever more opaque and conspiratorial.

As Moretti observes, the two archetypal modern monsters—he with the electrodes and he with the pointy teeth—emerge as the “horrible faces of a single society, its extremes: the disfigured wretch and the ruthless proprietor,” labor and capital.55 Frankenstein’s creation shows humanity penetrated and demolished by technology, forced to perform a kind of Saint Vitus’s dance on the factory floor, cadaverous and automated. By contrast, Dracula is the ur-exploiter depicted by Marxian theory, a sort of deified junkie: both the beneficiary and the victim of extraction. His amazing powers become a form of enslavement. Both figures embody a fear of what is to come: “express[ing] the anxiety that the future will be monstrous.”56

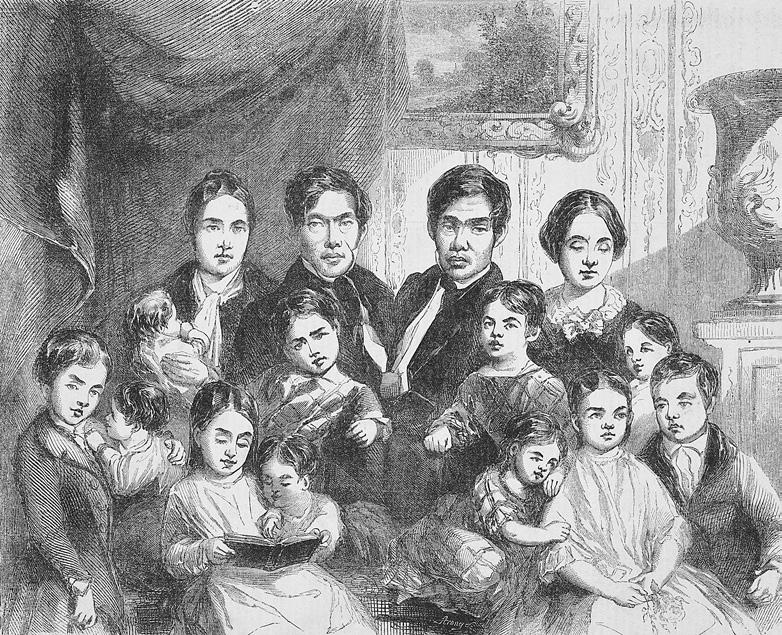

In a similar manner, the “Siamese twins” known as Chang and Eng gave embodiment to worry and ambivalence surrounding the threat of civil war to the “curious institution” of the antebellum South. This was because the famous pair, having taken the surname Bunker and married American sisters, settled in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains and accumulated a double homestead comprising twenty- two children and more than thirty slaves. When P. T. Barnum offered to pay for the conjoined twins’ surgical separation in 1868, many writers (Mark Twain among them) saw this as a ripe metaphor for the tenuous state of the nation. Would the brothers separate, or “would the union be preserved?”57

In making problematic the boundaries of the human actor, the aberration raises questions about the shifting contradictions of social context. The aberration embodies the Freudian uncanny: alien yet uncomfortably near, ourselves as the other. As Moretti writes, the monster “serves to displace the antagonisms and horrors evidenced within society outside society itself.”58 Here it stands objectified, as with the case of Shelley’s and Stoker’s symbols of exploitation, or in the figure of the cannibal who frequently appears in the pop mythology of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and more recently in the writing of Mo Yan.59 But this is merely one historical theme among many. Wherever there is an erosion of the conventions and structures that hold the seams (and the semes) together, monsters emerge.

The horrible has thus to do, in part, with a shifting of territorial borders. This is true of bodies and also of geographies. It moves the line of radical alterity, that which separates ourselves and others, to an inappropriate location. The seam or suture represents a joining of the unlike. The migration of frontiers often creates a misalignment between established communities and their spaces, as in states born of imperial fiat. Such is the case today with the flows of the translocal. As Achille Mbembe observes in his account of Africa, the manifold products of the entrepôt and the global city unfold under the sign of the horrid, their very be-

A characteristic depiction of Chang and Eng, the “Siamese twins,” with their wives and children, artist unknown, circa 1850–75. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library Prints and Drawings Collection, Yale University.

ing an embodied history of “strange signs,” “convulsive movements,” and “monstrous couplings.”60

The abnormality gives imaginative form to anxieties about being human under evolving conditions in a defamiliarized world. Horror is a notion that embodies both intimacy and “blasphemous alienage,” figuring the plight of modern subjects “at two with nature,” with our circumstances, and with ourselves.61

Horror in Architecture

When we look specifically at architecture, a parallel matrix of monstrous alterity emerges. This, too, concerns the deviations between “naturalized” norms and other, much more rarefied, possibilities. Deviant buildings, as one would expect,

represent conditions that reconfigure the conventions of the architectural object— substituting deformity for conformity. These mutations generalize under pressure, staking a claim as the genomics of a different order. For example, we will consider how the modernist assumption of the building as a coherent totality has recently been subverted: fragmentation, a totally opposed compositional principle, is now de rigueur in worlds of commercial expediency and elite cultural production. Here, a singularity— what Maurice Blanchot has called a “monstrous exception”— can quickly become the basis for a new rule.62

This raises a crucial question: How do such conditions arise in buildings? The productive innovations of capital provided an almost continuous source of upheaval for architects: mass replication, dramatically increased (and later reduced) scale, diversification and consolidation, and the domestication of electricity, wind, and water. These march alongside urban and geographical transformation: suburbanization, unprecedented increases and depreciations in value, war and cataclysm. The monstrosity frequently crops up in language at the interface of such transformations. In a crisis, the resources of an existing vocabulary are put under pressure by emergent aesthetic tropes, functions, and transformative materials and construction methods. The transitional building appears ill formed, as its prior devices are maladapted to their task. The good old tricks no longer work. The architect is forced to deploy conventions in ungrammatical assemblages, as there is no formal solution to the problem of the novel construction. The horrid wells up when the techniques of one historical moment fail to meet the needs of another.

The immanence of horror in the dynamism of the modern is especially legible in architecture. As elsewhere, built horrors have an intimate connection to the birth and death of conventions. This recalls Walter Benjamin’s claim that each great work signals the advent of a genre. However, new cultural constructs are frequently present, in incomplete form, before they are recognized. These are often greeted not as advancements but as oddities. Their arrival appears abominable: a mother birthing a child of a different species. This problematic nativity is due to a historical process, such as a shift in a dominant mode of production.63 Various socioeconomic orders have hatched the tragedy and the comedy, the essay and the novel, after their own image. Each has been retroactively hailed as an authentic expression of its time. Regardless, their morphogenesis was initially thought freakish. Herein we see the real avant-garde: awkward amalgams and provisional gestures.

Even now- canonical works have been viewed, in their infancy, as dubious. For this reason, Michel de Montaigne, while contributing to a new and influential

mode of philosophical writing, called his own essays “monstrous bodies, pieced together of diverse members, without definite shape, having no order, sequence, or proportion other than accidental.”64 Likewise, we might understand Henry James’s dismissal of the Russian novel as a “loose, baggy monster.” A similar charge has been leveled at the texts of James Joyce, at Jean Genet’s autobiographies, and also at some of Jacques Derrida’s compositional experiments. In particular, formal innovators—modern bricoleurs foremost among them—have been cast as Frankensteinian, making unseemly assemblages from fragments.

What does an equivalent building look like? Examples can be seen in the architecture of the so- called American commercial renaissance (circa 1840–1929). Many of the first great palaces of trade—mushrooming arcades and office towers—rose during this period to meet the practical needs of the industrial class, as well as to express the self-image of financial power.65 New orders of retail and recreational space came to prominence in burgeoning urban areas: department stores, auditoriums, and museums. These were of unprecedented size, both in sprawl and in height.

The resulting aesthetic—one of crowding—is discernible in the architecture of the period. This was particularly acute in the city, in the press of humanity around new commercial centers. As E. L. Doctorow later described it in Ragtime, “There seemed to be no entertainment that did not involve great swarms of people.”66 The social problem of the age involved unparalleled quantities and densities. As such, the regnant language of neoclassicism collided violently with the hyperbolic proportions of modernity. The adaptation of buildings to novel problems of scale and scope demanded prolonged experimentation and produced many rank failures; a menagerie of suggestive creatures sprang up along the way.

Architects experimented wildly with the application of historical styles and compositional tricks. As a stubborn conundrum, the large and complex structure required innovation. This reached an apex in the tower. Raymond Hood, designer of many significant examples, “felt that the skyscraper problem was still a relatively new phenomenon in American architecture, lacking any established traditions or strict formulas.” Hood, for one, “was quite happy with the prevailing mood in which everyone could try out whatever idea came into their head.”67 This was likewise the case with other emergent typologies.

Take, for example, the grandstand of the thoroughbred racetrack at Washington Park in Chicago (1884), the construction of which illustrates that moment in which a new challenge faces vernacular conventions. The question is straightforward: How should the very large building be designed? The answer is far from clear. Huge surfaces and volumes test the ability of the architect to create a