Florin Curta

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/medieval-eastern-europe-500-1300-florin-curta/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Women Archaeologists under Communism, 1917-1989: Breaking the Glass Ceiling 1st Edition Florin Curta

https://ebookmass.com/product/women-archaeologists-undercommunism-1917-1989-breaking-the-glass-ceiling-1st-editionflorin-curta/

Urban Panegyric and the Transformation of the Medieval City, 1100-1300 Paul Oldfield

https://ebookmass.com/product/urban-panegyric-and-thetransformation-of-the-medieval-city-1100-1300-paul-oldfield/

The Chivalric Turn: Conduct and Hegemony in Europe before 1300 David Crouch

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-chivalric-turn-conduct-andhegemony-in-europe-before-1300-david-crouch/

Mass Shootings in Central and Eastern Europe Alexei

Anisin

https://ebookmass.com/product/mass-shootings-in-central-andeastern-europe-alexei-anisin/

The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Central Europe Nada Zecevic

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-medievalcentral-europe-nada-zecevic/

Defining ‘Eastern Europe’: A Semantic Inquiry into Political Terminology Piotr Twardzisz

https://ebookmass.com/product/defining-eastern-europe-a-semanticinquiry-into-political-terminology-piotr-twardzisz/

Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands Robert Ousterhout

https://ebookmass.com/product/eastern-medieval-architecture-thebuilding-traditions-of-byzantium-and-neighboring-lands-robertousterhout/

Medieval Ethiopian Kingship, Craft, and Diplomacy with Latin Europe Verena Krebs

https://ebookmass.com/product/medieval-ethiopian-kingship-craftand-diplomacy-with-latin-europe-verena-krebs/

Researching Memory and Identity in Russia and Eastern Europe: Interdisciplinary Methodologies Jade Mcglynn

https://ebookmass.com/product/researching-memory-and-identity-inrussia-and-eastern-europe-interdisciplinary-methodologies-jademcglynn/

MEDIEVAL EASTERN EUROPE (500–1300)

READINGS IN MEDIEVAL CIVILIZATIONS AND CULTURES: XXV series editor: Paul Edward

Dutton

This page intentionally left blank

MEDIEVAL EASTERN EUROPE

( 500 –1300 ) A READER

edited by

FLORIN CURTA

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS

Toronto Buffalo London

© University of Toronto Press 2024

Toronto Buffalo London utorontopress.com

Printed in the USA

ISBN 978-1-4875-4487-4 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-4875-4491-1 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-4875-4490-4 (paper) ISBN 978-1-4875-4492-8 (PDF)

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisher—or in the case of photocopying, a license from Access Copyright, the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency—is an infringement of the copyright law.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Title: Medieval Eastern Europe (500–1300) / edited by Florin Curta.

Names: Curta, Florin, editor.

Series: Readings in medieval civilizations and cultures.

Description: Series statement: Readings in medieval civilizations and cultures | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifers: Canadiana (print) 20230510035 | Canadiana (ebook) 20230510086 | ISBN 9781487544904 (paper) | ISBN 9781487544874 (cloth) | ISBN 9781487544911 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781487544928 (PDF)

Subjects: LCSH: Europe, Eastern – History – To 1500 – Sources. | LCSH: Civilization, Medieval – Sources.

Classifcation: LCC DJK46 .M43 2024 | DDC 947 0009/02–dc23

We welcome comments and suggestions regarding any aspect of our publications— please feel free to contact us at news@utorontopress.com or visit us at utorontopress.com

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders; in the event of an error or omission, please notify the publisher.

Cover design: EmDash

Cover image: Vekenega Evangelistary of 1096

We wish to acknowledge the land on which the University of Toronto Press operates. This land is the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Anishnaabeg, the Haudenosaunee, the Métis, and the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fnancial support of the Government of Canada and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario, for its publishing activities.

Funded by the Financé par le Government gouvernement of Canada du Canada

CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES • xi

MAPS • xiii

INTRODUCTION • xix

A NOTE ON THE TRANSLATIONS • xxv

CHAPTER ONE: FROM LATE ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES • 1

1 Procopius on the Slavs • 3

2 Theophylact Simocatta on the Origin of the Avars • 4

3. Avars and Slavs • 6

4. Slavs, Avars, and Franks • 8

5. The Sermesians and Thessalonica • 11

6. Theophanes on the Bulgar Migration • 14

7. Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus on the Migration of the Croats • 16

CHAPTER TWO: EARLY POLITIES AND CONVERSION • 19

8 Notker on the Avars • 21

9 The Annals of Fulda on Moravia • 23

10 The Conversion of the Carantanians • 25

11 Saint Cyril, Old Church Slavonic, and the Creation of the Glagolitic Alphabet • 27

12 King Joseph on the Conversion of the Khazars to Judaism • 35

13 The Conversion of the Volga Bulghars to Islam • 40

14. Pope Nicholas I Answers the Questions of Boris of Bulgaria • 42

CHAPTER THREE: MEDIEVAL NOMADS • 45

15. Ibn Rusta on the Magyars • 47

16. Ibn Fadlan on the Oghuz • 48

17. John Skylitzes on the Pechenegs • 51

18 Robert de Clari on the Cumans • 53

CHAPTER FOUR: THE IRON CENTURY • 55

19 Wulfstan Travels to Truso • 57

20 George the Bulgarian and the Magyars • 58

21 John the Exarch on Symeon the Great • 60

22 A Hermit Meets an Emperor • 62

23 Skylitzes Continuatus on the Bulgarian-Byzantine War • 64

24 Echoes of the Bulgarian-Byzantine War in France and in Syria • 66

25 Varangians in Rus’ • 67

26 Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus on the Rus’ • 69

27. A Trade Agreement between the Rus’ and Byzantium • 71

CHAPTER FIVE: THE BALKANS BETWEEN THE NINTH AND THE TWELFTH CENTURIES • 75

28. The Resettlement of the Peloponnese • 77

29. The Thirty-Year Peace • 78

30. The Story of Danelis • 80

31 Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus on the Confict between Bulgars and Serbs • 83

32 Saint Luke the Younger and Bulgarian Attacks on Greece • 84

33 Kekaumenos on the Vlachs • 86

34 King Peter Krešimir IV Donates an Island • 89

35 Theophylact of Ohrid on Recruitment Shortages in the Balkans • 91

36 The Battle of Dyrrachion • 93

37. The Cadastre of Thebes • 98

38. Archdeacon Thomas on Archbishop Rainer of Split • 100

CHAPTER SIX: NEW POWERS • 103

39. The Magyars Conquer Hungary • 105

40. The Origin of the Přemyslid Dynasty • 107

41. The Origin of the Piast Dynasty • 110

42 Dagome iudex • 112

43 The Assassination of Duke Wenceslas • 113

44 The Gniezno Summit • 118

45 A King’s Mirror: The Admonitions • 120

46 Thietmar of Merseburg on Bolesław Chrobry • 123

47 The Decrees of Břetislav • 126

48 The Collapse of the Piast State • 129

49 Simon of Kéza on the Pagan Revolt • 130

50. Abu Hamid on Hungary • 132

51. Vincent of Prague on King Vladislav II • 135

52. The Golden Bull of 1222 • 136

CHAPTER SEVEN: ECONOMY AND SOCIETY • 141

53 The Diet of Rižana • 143

54 John Kaminiates on Thessaloniki before the Sack of 904 • 148

55 Slaves for the Benedictine Abbey of St-Peter in the Village • 153

56 The Typikon of Isaac Komnenos for His Monastery near Bera • 156

57 The “Statutes” of Conrad Otto II • 159

58 Treaty between Riga, Gotland, and Smolensk • 162

59. Charter of John II Asen for Ragusa • 168

60. The Henryków Book on Feudalism • 169

CHAPTER EIGHT: FAITH, RELIGION, HERESY • 171

61. The Invention of the Relics of Saint Clement • 173

62. The Bogomils • 176

63. The Martyrdom of Saint Ludmila • 178

64 Instruction on Liturgical Practices • 180

65 The Martyrdom of Saint Adalbert • 183

66 The Many Lives of Saint Stephen • 186

67 Demons, Wine, and Relics for a Church in Sparta • 190

68 Rule of the Lavra Monastery on Mount Athos • 193

69 A Hermit’s Portrait: Saint Andrew-Zoerard • 195

70 The Passion of the Holy Martyrs Boris and Gleb • 198

71 Typikon of the Monastery in Bachkovo • 203

72 Jews in East Central Europe • 207

73. Razumnik, a Study Guide • 210

74. Social Problems in the Questions of Kirik • 213

75. The Assassination of Bishop Stanisław of Cracow • 214

76. Stephen Nemanja Establishes the Hilandar Monastery • 218

77. Saint Sava’s Second Trip to the Holy Land • 220

78. The Synod of 1211 Condemns the Bogomils • 223

CHAPTER NINE: CRUSADES • 227

79 The Army of the First Crusade in Hungary • 229

80 Bernard of Clairvaux Calls on the Czechs to Take the Cross • 233

81. Hungary at the Time of the Second Crusade • 235

82 The Crusade against Lettgallians • 238

83 The Army of Frederick Barbarossa Crosses the Balkans • 240

84 The Sword Brothers • 244

85 The Conquest of Zara • 248

86 The Crusade of King Andrew • 251

87 The Teutonic Knights in Transylvania • 254

88 The Conquest of Prussia and Saint Barbara • 256

89 Pope Gregory IX Calls for a Crusade against John II Asen • 260

CHAPTER TEN: LAW • 263

90. First Law Code in Eastern Europe • 265

91. Church and Secular Law in the Statute of Yaroslav • 266

92. The Laws of King Coloman • 269

93. Russkaia Pravda • 272

94. Law Code of Vinodol • 273

95. Making a Will • 276

CHAPTER ELEVEN: LITERACY AND LITERATURE • 279

96 Khrabr Defends the Slavonic Letters • 281

97 Saint Clement of Ohrid on Saint Cyril • 283

98 Birchbark Letters • 285

99 Sermon on Law and Grace • 287

100 On the Lame and the Blind • 290

101 The Primary Chronicle on the Origins of the Slavs • 293

102. Queen Vanda of the Poles • 296

103. The Hungarian-Polish Chronicle on a Meeting of Rulers • 298

CHAPTER TWELVE: THE NEW POWERS IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY • 301

104. Benjamin of Tudela on the Vlachs • 303

105. The Vlach Rebels in Bulgaria • 304

106 Stephen Nemanja Submits to Emperor Manuel I • 307

107 Saint Sava on Stephen Nemanja’s Abdication • 308

108 Johannitsa Kaloyan Writes to Pope Innocent III • 311

109 Robert de Clari on the Battle of Adrianople • 313

110 Henri de Valenciennes on Alexius Slav • 315

111 John II Asen Boasts of His Victory at Klokotnica • 318

112 Serbs Defeat the Byzantines, a Serb on the Bulgarian Throne • 319 viii

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: MONGOL CONQUESTS AND PAX MONGOLICA • 323

113 The Quriltai of 1235 (Juvaini) • 325

114 Mongols in Northeastern Rus’ • 327

115 The Battle of Muhi • 330

116 The Mongol Sack of Oradea • 335

117 The Camp of Batu Khan on the Volga • 337

118 Kiev after the Mongol Invasion • 340

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • 343

CHRONOLOGY • 345

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY • 349

SOURCES • 351

INDEX OF TOPICS • 359

This page intentionally left blank

1.1 Triumphant Avar Warrior on Horseback • 1

2.1 Saints Cyril and Methodius • 19

3.1 Pechenegs Ambush and Kill Prince Sviatoslav of Kiev ( 971) • 45

4 1 Saint John of Rila • 55

5 1 Inscription of Süleyman Köy • 75

6 1 Assassination of Duke Wenceslas of Bohemia • 103

7 1 Saint Adalbert Pleads with Boleslav II, Duke of Bohemia 141

8 1 Angel • 171

9 1 Hermann of Salza • 227

10 1 Law Code of Vinodol • 263

11 1 Funeral Sermon and Prayer • 279

12 1 Seal of Grand Ž upan Stephen Nemanja (1198) • 301

13.1 The Battle of Legnica (1241) • 323

This page intentionally left blank

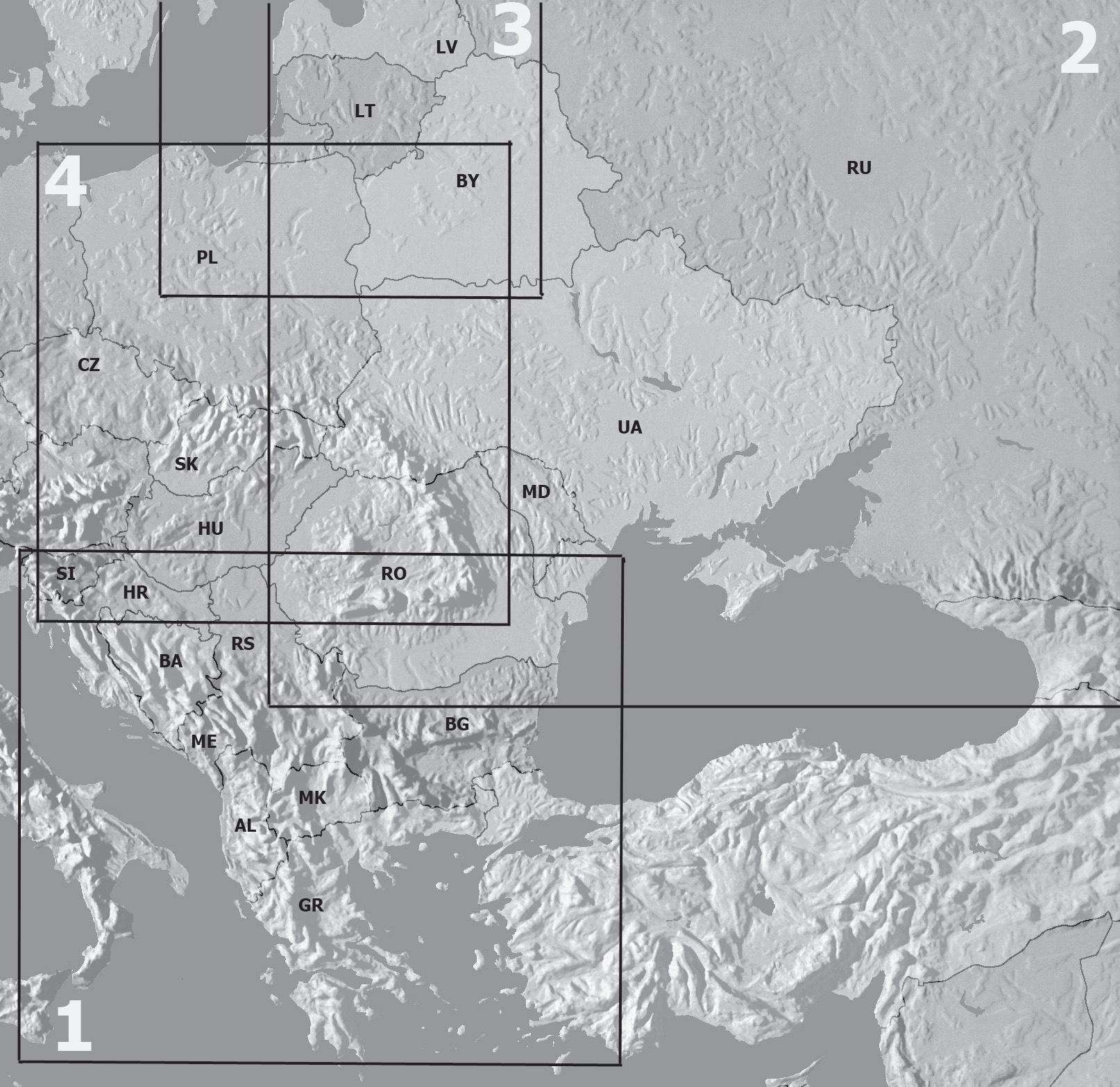

MAPS

Landscape and political map of eastern Europe

Country abbreviations: AL—Albania; BA—Bosnia and Herzegovina; BG—Bulgaria; BY—Belarus; CZ—Czech Republic; GR—Greece; HR—Croatia; HU—Hungary; LT— Lithuania; LV—Latvia; MD—Moldova; ME—Montenegro; MK—Macedonia; PL— Poland; RO—Romania; RS—Serbia; RU—Russia; SI—Slovenia; SK—Slovakia; UA— Ukraine. The numbers refer to the following detail maps.

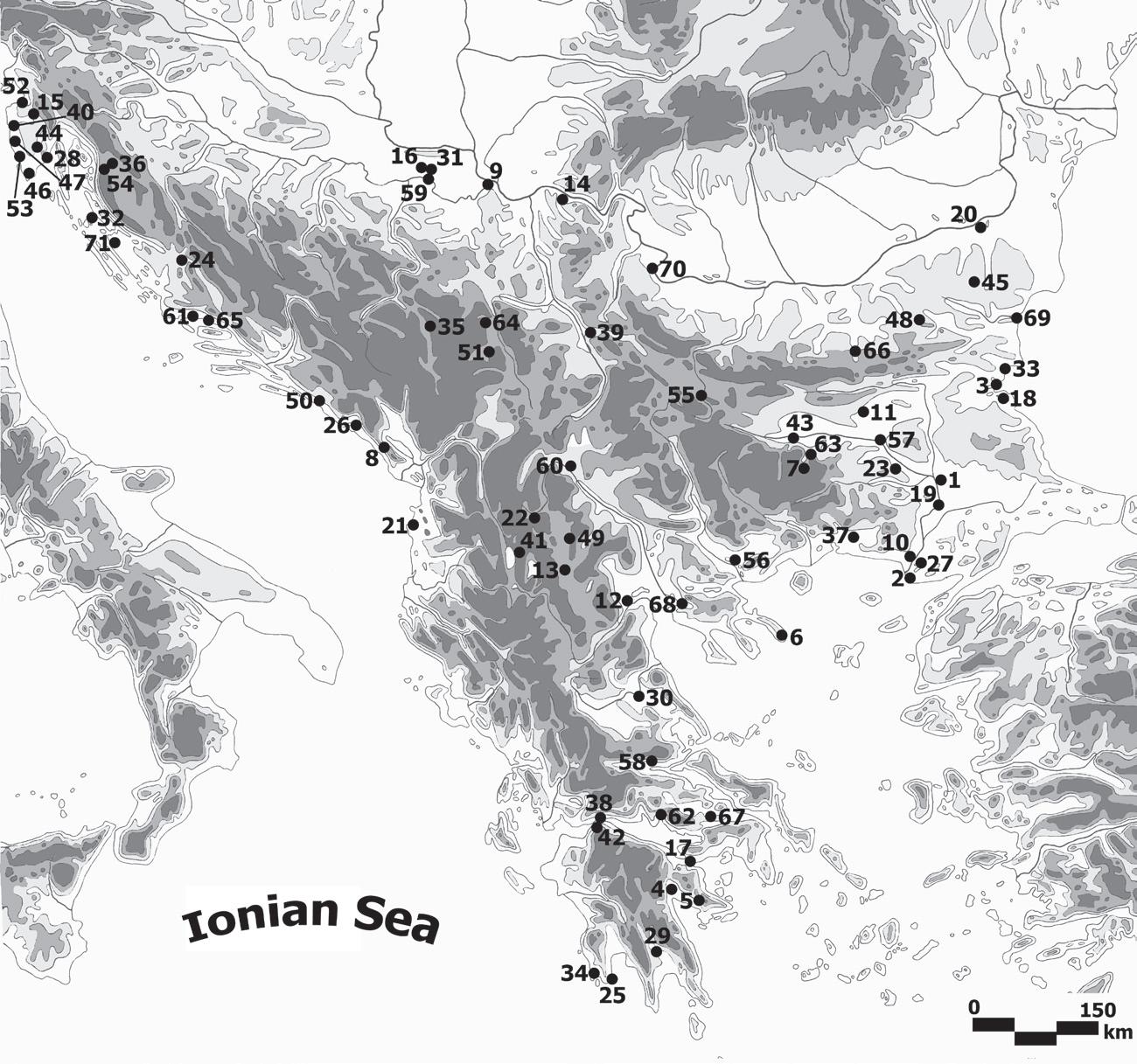

Detail map 1 with place names mentioned in the text (ancient or medieval names in italics and parentheses): 1 Adrianopolis (Adrianople); 2 Ainos; 3 Anchialos; 4—Argos; 5—Athens; 6—Athos, Mount; 7—Bachkovo; 8—Bar; 9—Belgrade; 10 Bera; 11 Beroe (Borui); 12 Beroia (Veroia); 13—Bitola; 14—Braničevo; 15—Buzet; 16 Čalma; 17— Corinth; 18 Deultum; 19 Dimotika; 20 Dorostolon; 21 Dyrrachion (Drach); 22— Kičevo; 23—Klokotnica; 24—Knin; 25 Korone; 26—Kotor; 27 Kypsella; 28—Labin; 29 Lakedaimon (Sparta); 30—Larissa; 31—Manđelos; 32—Maun; 33 Mesembria; 34 Methone; 35—Mileševa; 36—Modruš; 37 Mosynopolis; 38—Naupaktos; 39 Naissus (Niš); 40—Novigrad; 41—Ohrid; 42—Patras; 43 Philippopolis; 44—Pićan; 45— Pliska; 46 Pola; 47—Poreč; 48—Preslav; 49—Prilep; 50 Ragusa; 51—Ras; 52—Rižana; 53—Rovinj; 54—Senj; 55 Serdica (Sredec, Triadica); 56—Serres; 57—Simeonovgrad; 58 Sinon Potamo; 59 Sirmium; 60—Skopje; 61—Split; 62—Steiris; 63 Stenimachos; 64—Studenica; 65—Sumpetar; 66—Tărnovo; 67—Thebes; 68 Thessalonica (Thessaloniki); 69—Varna; 70—Vidin; 71—Zadar.

Detail map 2 with place names mentioned in the text: 1—Beloozero; 2—Bolgar; 3— Chernigov; 4—Cherson; 5—Dnipro; 6—Halych; 7—Iur’ev Polski; 8—Izborsk; 9—Kaniv; 10—Kiev; 11—Kolomna; 12—Kozel’sk; 13—Moscow; 14—Murom; 15—Novgorod; 16—Pereiaslavl’; 17—Pinsk; 18—Polotsk; 19—Pronsk; 20—Riazan’; 21—Rostov; 22— Saqsin; 23—Smolensk; 24—Suzdal’; 25—Torzhok; 26—Tver; 27—Vitichev; 28—Vladimir-in-Volhynia; 29—Vladimir-on-Kliazma; 30—Volokolamsk; 31—Voronezh; 32— Vyshhorod; 33—Yaroslavl; 34—Zaporizhzhia.

Detail map 3 with place names mentioned in the text (medieval names in italics and parentheses): 1 Balga; 2 Christburg; 3 Dobrin; 4 Dorpat (Iur’ev); 5 Fellin; 6—Gdańsk; 7—Ikšķile; 8—Koknese; 9 Kulm; 10 Marienwerder; 11 Rehden; 12 Reval; 13—Riga; 14—Rubene; 15—Scheidenitz; 16 Thorn; 17 Truso; 18—Turaida.

Detail map 4 with place names mentioned in the text (medieval names in italics): 1— Bakonybél; 2—Braşov; 3—Bratislava; 4—Břeclav; 5—Brno; 6—Budapest; 7—Cenad; 8—Cracow; 9—Esztergom; 10—Giecz; 11—Gniezno; 12—Hălmeag; 13—Henryków; 14 Hung; 15—Kalocsa; 16—Kołobrzeg; 17—Lubiń; 18—Meißen; 19—Mosonmagyaróvár; 20—Muhi; 21 Munkács; 22—Oradea; 23—Ostrów Lednicki; 24—Pannonhalma; 25—Pécs; 26—Płock; 27—Poznań; 28—Prague; 29—Rodna; 30—Sadská; 31— Slankamen; 32—Stará Boleslav; 33—Székesfehérvár; 34—Tarcal; 35—Tetín; 36—Ungra; 37—Vyšehrad; 38—Wrocław; 39—Znojmo; 40 Zobor

xvii

This page intentionally left blank

INTRODUCTION

Most courses on eastern Europe offered in North American universities focus on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the period of nationalism. The medieval history of the area is given comparatively less attention, which often amounts to slightly more than total neglect. The underlying assumption is that the lands in that area “entered” Europe only during the Modern Age, and then only partially. On the other hand, for most students of medieval history, eastern Europe is marginal and eastern European topics somewhat exotic. Textbooks of medieval European history typically contain maps of the continent “cut off” at the River Elbe. When showing the entire continent, the eastern part is typically left blank, except for some physical features and a couple of cities such as Prague or Constantinople. Judging from such textbooks, one is left with the impression that eastern Europe was deserted in the Middle Ages, and if any people lived in the sparse communities in the eastern part of the continent, they did not matter much and left no sources or testimonies of their lives.

This reticence may be explained in part, at least, by means of the relatively recent interest in the study of the medieval history of eastern Europe. The very idea of “eastern Europe” goes back to the intellectual milieu of the Enlightenment, but the serious study of the region’s history during the Middle Ages began less than a century ago. Three consecutive international congresses of historical sciences that took place in the interwar period—in Brussels (1923), Oslo (1928), and Warsaw (1933), respectively—frst established the topic and its fundamental directions of research. During World War II, Oskar Halecki (1891–1973), a historian specializing in the history of late medieval Poland and a refugee from the lands occupied by the Nazis, transplanted that new scholarly interest to America. For a decade or so at the beginning of the Cold War, the interest in medieval eastern Europe was directly linked to the west-east division of the continent and served as its justifcation. After c. 1960, however, that interest simply died out, as the ideological and political confrontations of the Cold War moved outside Europe. The interest in the medieval history of eastern Europe was revived only in the late twentieth century, largely, again, as a reaction to the political developments following the demise of the communist regimes. The eastern European Middle Ages have therefore become a remarkably dynamic feld of study only during the last three decades or so.

What is eastern Europe, after all? The vast area of the European continent situated between the Czech lands to the west and the Ural Mountains to the east, and from beyond the Arctic Circle to Greece on a north-south axis may be best described as the land mass between latitude 36º and 70º north, and from longitude 12º to 60º east. If dividing that land mass arbitrarily into two slightly unequal slices, east central Europe is the western half, between 12º and xix

35º east; and eastern Europe the eastern half, between 35º and 60º east. The western half may be further subdivided latitudinally along 45º north to distinguish southeastern Europe, located to the south of that parallel. These internal divisions of the area and their conventional names represent two-thirds of the entire European continent. The vast extent of the area is only matched by its incredible variety, which was directly refected in the economic and political developments of the Middle Ages. Despite the political meaning commonly attached to “eastern Europe,” in this book the phrase is used in a primarily and purely geographic sense.

Historians in eastern European countries have long struggled with periodization, especially when attempting to match the order of events in western Europe and to fnd a place in the history of the continent for their respective countries. Such problems concern both the beginning and the end of the Middle Ages. To be sure, much of what Oskar Halecki called east central Europe and the whole of eastern Europe never formed a part of the Roman empire. In southeastern Europe, the withdrawal of the Roman armies in the early seventh century provides a convenient marker, but many scholars prefer to begin with the coming of the “barbarians,” especially the Slavs, c. 500. With no event to fall in place conveniently like a curtain at the end of Antiquity, some historians have now placed the “dawn of the Dark Ages” in 568, the year in which the Avars defeated the Gepids and the Lombards migrated to Italy. However, the “arrival of the Slavs” marks the beginning of the Middle Ages to such an extent that the adjectives “Slavic” and “medieval” are used interchangeably in many Slavic-speaking countries.

Much more diffcult is it to reach some agreement among historians about the end of the Middle Ages. Generations of Hungarian historians, for example, have used the year 1526 (in which the Hungarian army was crushed by the Ottomans at Mohács) as the dividing point between the ages called medieval and modern. It is worth noting that in that interpretation, the modern era begins with a national tragedy, with foreign rule, with misery. Similarly, Bulgarian historians of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries unanimously condemned the period of Ottoman rule as one of utter subjugation, national disaster, and misery. “Dark Ages” to Bulgarian historians of an earlier generation was not another name for the Early Middle Ages, but a most appropriate description of the centuries following the fall of Tă rnovo in 1393 According to such views, the Ottoman conquest was a turning point in Bulgarian history, for both state and church were abolished, with Bulgaria now being divided between two eyalets (or administrative divisions of the Ottoman empire), and the lands previously under the jurisdiction of the patriarch of Tă rnovo taken over by the patriarch of Constantinople, the patriarch of Peć, and the archbishop of Ohrid. The Ottomans allegedly stopped the gradual

process of economic convergence between Bulgaria and the rest of the European continent.

The diffculty in fnding an appropriate marker for the end of the Middle Ages creates further problems for the assessment of later periods, especially when there are clear signs of continuity from the Late Middle Ages. Were seventeenthcentury Hungary under Habsburg rule or eighteenth-century Bulgaria under Ottoman rule still medieval in any sense? Can one speak of the Middle Ages for pre-Petrine Russia? When do the Middle Ages end, and when did modernity begin in eastern Europe? These are complicated questions involving a deeper analysis of multiple factors of development, and no answers have so far been provided. Most historians have in fact rejected the attempt to pigeonhole the history of the region into preconceived chronological boxes. The existence of multiple criteria for periodization makes arbitrary any attempt to “cut” the Middle Ages to size.

For the purposes of this book, however, the cutoff date of 1300 may be a felicitous, if arbitrary, choice. Several economic and political transformations were well underway by 1300 : intensive agriculture, nucleated settlements, the arrival of a great number of “guests,” particularly from the German-speaking areas of central Europe, increased urbanization, the rise of the money economy, and changes in the structure of the nobility. All of these transformations opened a new chapter in the history of the region. The year 1300 also marks a watershed in the history of southeastern Europe, as it is directly linked to the early Ottoman conquest. Moreover, the native dynasties of Hungary and Bohemia died out around that year. The loss of the Holy Land prompted the Order of St-Mary (the Teutonic Knights) to abandon its headquarters in Venice and to move to Marienburg in Prussia, a move that many historians regard as the pivotal point in the development of the Teutonic Order and of its state in the Baltic region. In neighboring Poland, the year 1300 witnessed the restoration of the kingdom after the coronation in 1295 in Gniezno of Przemyśl II, duke of Greater Poland. Several other developments in the course of the frst half of the fourteenth century may evidently be tagged as novel, from the rise of the Serbian empire of Stephen Dušan (1331–55), the dispute between Moscow and Tver over Vladimir’s position as grand prince of (1304–27), the rise of the Gediminid dynasty in Lithuania and of the Shishmanid dynasty in Bulgaria, to the Islamicization of the Golden Horde after the conversion of Khan Üzbek (1313–41). The eight centuries between c. 500 and c. 1300 represent therefore a suffciently long segment to follow the medieval history of eastern Europe.

Much of the renewed interest in that history derives in fact from an attempt to move away from the practice, so prevalent during the Cold War, of using it as a justifcation for modern divisions. On the other hand, an “add-eastern-Europeand-stir” approach to the history of the continent proves to be reductionist: xxi

a way to distill the specifc history of the region to a simple solution, one that can easily match (and confrm) models created on the basis of western European history. That in turn results from the idea that eastern Europe had to imitate the much earlier developments taking place in western Europe, for progress moved from west to east. To the extent that eastern Europe forms an entity worth studying by historians of the Middle Ages, its distinctive feature is therefore identifed as a supposed lateness of development, in economic, political, and cultural terms. Some go so far as to deny that the eastern part of the continent became “European” before the tenth century. Others have already noted, however, that in many respects, eastern Europe followed its own path, often in contradiction to that of the western regions of the continent. A chasm has meanwhile been created and continues to grow between the production of outstanding works by talented historians of eastern Europe in the Middle Ages and the reception of that scholarly output, its impact on historiography in general, and its supposed incorporation into “global history.” At this juncture, it is therefore necessary to bridge that chasm and to correct, if only partially, the many misperceptions and stereotypes that plague this feld of study. This book, the frst of its kind on the subject, aspires to provide a solid documentary basis for that scholarly and educational endeavor, and to make a signifcant contribution to the understanding of the problems raised by the medieval history of eastern Europe.

Writing and literacy came to eastern Europe from the outside as part of the “cultural kit” accompanying the conversion to Christianity between c. 800 and c. 1000. Moreover, new scripts were created at the time of the conversion to Christianity (frst Glagolitic, then Cyrillic), and remained characteristic of the medieval culture of the region, for they do not appear elsewhere in Europe. Chanceries began to operate in the tenth century in Croatia and Bulgaria, and in the following century in Hungary, Poland, Bohemia, and Rus’. The earliest surviving charters are those from eleventh-century Hungary, Bohemia, and Poland, followed by Serbia and Rus’ in the twelfth century. Some Benedictine monasteries in Croatia have extensive cartularies, containing copies of charters issued by Croatian and Hungarian rulers. The private use of writing, for example in letters, is a later phenomenon. The most extraordinary body of letters providing a unique glimpse into the daily lives of medieval people in eastern Europe is the ever-growing corpus of letters written not on parchment, but on birchbark. The birchbark letters are not preserved in archives but have been found during archaeological excavations since 1930 on several urban sites in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. The contemporary evidence of writing from Bulgaria consists of inscriptions. Fewer such documents are known from Bohemia and Poland, but foundation inscriptions in churches appear in Hungary and Croatia.

The medieval history of eastern Europe is not very rich in narrative sources. Very few such sources exist for the period before c. 1000, and most “national” chronicles are of a later date. The earliest is the so-called Primary Chronicle, which is in fact the work of several annalists, the last of whom fnished writing c. 1113 About the same time, in Poland, an anonymous author of possibly French origin (hence his conventional name, Gallus Anonymus) wrote the Deeds of the Prince of the Poles. A decade later, Cosmas of Prague fnished his Chronicle of Czechs, which was then continued by an anonymous author known as the Canon of Vyšehrad to 1142, when another canon from Prague named Vincent wrote an independent chronicle covering the years 1140 – 67. His work was then continued by Gerlach, the abbot of the Premonstratensian house of Milevsko. In Hungary, the earliest surviving historical writing is the Deeds of the Hungarians, written in the 1220s by the former “notary” (secretary) of a king named Béla, most likely Béla III. Slightly earlier are the annals compiled in the Vydubichi Monastery near Kiev, known as the Kievan Chronicle. In the early thirteenth century, Master Vincent Kadłubek, the future bishop of Cracow, fnished his Chronicle of the Kings and Princes of Poland. In the course of the thirteenth century, several annals were compiled in Cracow, in a number of monasteries in Silesia, in Pozna ń, as well as in Prague and Bratislava. Both the Hungarian-Polish Chronicle, a fantastic version of Hungarian history combined with Polish historical elements, and the History of the Bishops of Salona and Split of Archdeacon Thomas of Spalato were written in the mid-thirteenth century or shortly thereafter. The last decades of that century witnessed the appearance of another work entitled the Deeds of the Hungarians by Master Simon of Kéza, the Silesian-Polish Chronicle and the Chronicle of the Poles, written in Greater Poland. Shortly before 1300, the Chronicle of Halych-Volhynia was also fnalized. Most, if not all, of these narrative sources were written by churchmen who, with few exceptions, had no reliable sources for the earliest periods in the history of their respective countries. For the frst centuries of eastern European medieval history, historians have therefore had to rely on foreign sources—Byzantine (in Greek), west European (in Latin), but also Arabic and Hebrew.

Contrary to the common misconception, there is an abundance of written sources on the medieval history of eastern Europe. This book is meant to provide a helpful sample for students and other readers. Far from aspiring to cover eight hundred years of history in just 118 documents, my intention is to offer a glimpse into the variety of the material available and to supply sources that could complement textbooks and monographs used in history courses. The following sections include a few texts that are known to many, such as the “invitation” of the Varangians to Rus’—a story to be found in the Primary Chronicle —or Geoffrey of Villehardouin’s account of the conquest of Zara at the beginning of the Fourth Crusade. However, most other texts are less well xxiii

known, even if the reader may be familiar with their authors’ names—Wulfstan, Anna Komnena, Bernard of Clairvaux, Benjamin of Tudela, Robert de Clari, or William of Rubruck. In such cases, the sources shed a different light on the range of concerns that those authors had and will help integrate many chapters of eastern European history into a broader discussion of medieval Europe. Many more texts may simply be unknown to the reader, much like their authors—ibn Fadlan, John the Exarch, Kekaumenos, Thomas of Spalato, Cosmas of Prague, Gallus Anonymus, Simon of Kéza, Abu Hamid, Vincent of Prague, John Kaminiates, Henry of Livonia, Vincent Kadłubek, Niketas Choniates, or Roger of Torre Maggiore.

There are also charters, legal and fscal texts, private letters, inscriptions, and treatises without which an in-depth understanding of the history of eastern Europe during the Middle Ages would not be possible. I have tried to provide a balanced view by selecting sources of many kinds, including such “oddities” as homiletic literature and penitentials. While the presentation of the selections is largely chronological, some sections are purely thematic (economy, society, religion, law), in an attempt to cover as much ground as possible within the given space. It is of course impossible to include everything and I am conscious of omissions, but convinced that the selection is representative at least of the current directions of research on the history of eastern Europe in the Middle Ages. My hope is that readers will be encouraged to delve further into primary texts dealing with eastern Europe in the Middle Ages. The clusters of documents on certain topics, such as law, will beneft particularly those readers who are interested in a comparative approach. I have provided the necessary context in the introduction to each reading, but have kept my interventions to a minimum, in order to allow students to discover on their own the points of view of the medieval authors.

The questions asked at the end of each section are mere suggestions for further discussion of those points of view. The juxtaposition of genres in certain sections (for example, Chapter 6, “New Powers”) should prompt readers to note conficting, complementary, and divergent views and ideas about power, law, and rule. My own editorial interventions within the texts are meant to assist with the clarifcation of the context. I have kept such interventions to a minimum, as in the introductions. I draw attention to particular themes that have been highlighted by research into eastern Europe or are currently popular study topics, but understanding the medieval history of the region involves the study of many texts and documents from several other parts of Europe and Asia, written in many different languages. My goal with this collection is to highlight the geographic, historical, and linguistic diversity of the primary source materials relating to medieval eastern Europe.

A NOTE ON THE TRANSLATIONS

Unless otherwise noted, all texts are translated for this reader. Editorial insertions appear in square brackets. Most personal names and some place names have been anglicized. For example, Ivan Asen II appears as John II Asen, Václav as Wenceslas, and King István as Stephen, as well as King András as Andrew. By the same token, I have used Prague instead of Praha, Cracow instead of Kraków, and Thebes instead of Thiva. I have also preferred Kiev to Kyiv, and Vladimir to Volodymyr, because of the usage established in the literature on Rus’ written in English. With the exception of cases where common English spelling was preferred, the transliteration of personal and place names follows a slightly modifed version of the Library of Congress system.

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER ONE

FROM LATE ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

This page intentionally left blank

1. PROCOPIUS ON THE SLAVS

Procopius of Caesarea is one of the greatest historians of Late Antiquity. He was born around 500 and died c. 560, having thus lived much of his life as a contemporary of Emperor Justinian (527 – 65 ). Procopius was an assessor (legal adviser) on the staff of General Belisarius and accompanied him on campaign in Mesopotamia, Africa, and Italy. His longest and most important work consists of a history of the wars of Emperor Justinian, comprising two books on the Persian, two on the Vandal, three on the Ostrogothic wars, and a fnal book continuing the story on all three fronts. The work covers the period 527 –51 and is one of the most important sources for the sixth-century history of the empire and its barbarian neighbors. The excursus (digression) on the Slavs in Book 7 is the longest description of any barbarian group in the work on Justinian’s wars, an indication of the special interest Procopius and his audience had in things Slavic. The excursus was most likely written in 550 or 551 on the basis of information that Procopius may have obtained through interviews with Sclavene and Antian mercenaries in Belisarius’s army in Italy.

Source: trans. H.B. Dewing and A. Kaldellis, Procopius, The Wars of Justinian (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2014), pp. 408–09.

7 14 22–30. For these nations, the Sclavenes and the Antes, are not ruled by one man, but they have lived from of old under a democracy, and consequently everything which involves their welfare, whether for good or for ill, is a matter of common concern. In almost all other matters these two barbarian peoples have had the same institutions and beliefs from ancient times. They believe that one god, the maker of lightning, is alone lord of all things, and they sacrifce to him cattle and all other victims; but as for fate, they neither know it nor do they in any way admit that it has power over men. Whenever they face death, either stricken with sickness or at the start of a war, they promise that, if they escape, they will immediately make a sacrifce to the god in exchange for their life; and if they escape, they sacrifce just what they have promised and consider that their safety has been bought with this same sacrifce. But they also revere rivers and nymphs and some other spirits, and they sacrifce to all these too, and they make their divinations in connection with these sacrifces. They live in pitiful hovels that they prop up far apart from one another, and, as a rule, every man is constantly changing his abode. When they enter battle, the majority of them go against their enemy on foot carrying little shields and javelins in their hands, but they never wear breastplates. Indeed, some of them do not wear even a shirt or a cloak but hitch their trousers up by their private parts and so enter battle with their opponents. Both people have the same language, which is utterly barbarous. Nor do they differ at all from each another in appearance. For they are all exceptionally tall and hardy