Dedication

Wearebornasfromaquietsleep,andwedietoacalmawaking.*

Zhuang Zhou, Zhuangzi

Notes

* Müller, F.M. (ed.) (1891) The Sacred Books of the East. Translated by J. Legge. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction: the ultimate questions of consciousness, life and the universe

1 A tale of millions of years: the origin of consciousness research (from the Old Stone Age to the Middle Ages)

Myth:facingtheunknownandtheabyss

Religion:thewordsofanoak

Philosophy:knowthyself

Science:thesubstratesofthesoul

2 A five-century quest: explaining consciousness (17th century–today)

Ghostinthemachineandbirthofconsciousness

Measureconsciousness:riseofexperimentalpsychology

Eraofconsciousness:qualia,brain,computerandquantummind

The hard problem: what is it like to be a bat or a zombie?

Theemergenceoftheexplanatorygap

Thehardproblem,afalseproblem?

The neural basis of consciousness: specialization, integration and embodiment

Globalintegrationofbrainactivity

Keyintegrativeneuralstructures

Computers as brains and conscious machines

Theriseofinformationtheory,functionalismandcomputationalism

ThebirthoftheTuringtestandconsciousmachines

Quantum consciousness

Consciousness:spectatororactor?

Consciousnessandquantumbrain

Wherearewenow?

3 Toward the ultimate understanding of consciousness: tracing the deep roots in life and the universe

Ouressence:thehiddenfoundationandnatureofconsciousness

The indispensable substratum of consciousness

Anatomicalhierarchyofconsciousness

Evolutionary and developmental hierarchy of the substrates of consciousness

Functionalhierarchyofthesubstratesofconsciousness

What is consciousness?

Feelingthebody:integratedinternalbodymappingasfoundational consciousness

Sensing the world: integrated body-environment mapping as expansiveconsciousness

Higher cognitive functions as advanced mapping tools for augmentingconsciousness

In search of the hidden part of ourselves: the nonconscious processesofthehumanorganism

Neural information processing that does not produce conscious experience

Dissociateexperimentallyconsciousandnonconsciousprocesses

Whentheblindarenotblind. . .

Markersofconsciousandnonconsciousprocesses?

Physiological processes that cannot be consciously controlled

Cognitiveprocessesoutofourcontrol

Thoseautomaticfunctionsthatkeepusalive Nonconsciouscontrolofmusclesandaction

Physiological processes that cannot be directly accessed through consciousness

Theinnerworkingsofourbodyinsulatedfromourselves

Benefitsandfatalflawsofthelimitedconsciousaccesstoourbody

Unlockthesecretsofourbody:mapthenonconsciousandexpand consciousness

Asolongjourney:fromasinglecelltothehumanorganism

Building a home: primitive internal and external mapping in unicellular organisms

Emergenceofthefirstlivingstructures

Membrane,thefoundationofahome

Theoriginofinternalandexternalmappinginlivingorganisms

Building a body: augmented and integrated internal and external mapping in multicellular organisms

Unitymakesstrength:fromsinglecellstomulticellularorganisms

Enhancement of senses and global homeostatic systems— enhancementofmappingabilities

Emergence of nervous systems: a further step in integrated mapping

The human organism: advanced internal and external mapping and the next leap of evolution

Fromabacterium'ssensingtohumanconsciousness

Whatmakesourconsciousnesshuman

Thenextevolutionaryleapofhumanconsciousness

Deepinourcells:fromparticlestotheuniverse

The origin of consciousness: what is life?

Theverypulseoflifeandconsciousness

ThefoundationandoriginoflifeonEarth

Specialstructuresinthefabricoftheuniverse

The ultimate origin and meaning of life and consciousness: what is the universe?

The cosmic origin of the fundamental laws governing life and consciousness

ThemindofGodortheoriginoftheuniverse:nothingness?

Thefinaljudgment:allismeaningless?

4 Expand consciousness: toward the unknown

Expandbodymappingandenhanceself-regulationandself-repair

Expand environment mapping and assimilate the worlds of other life-forms

Expand the multiscale mapping of the universe: from nothingness totheentirecosmos

Conclusion:createthefuture Index

FOREWORD

In Consciousness,LifeandtheUniverse, Dr. Xue Fan, a historian and philosopher of science, provides a unique, original and elegant review across billions of years of many aspects of life, not least importantly of consciousness and initially its old cousin, the soul. From ancient times until today, humans have mostly considered the soul to be separate from the body, and this is the theme of the very interesting first part of the book. In old myths, the spirits of the dead were thought to haunt the living, and measures were taken to please the evil spirits. In practically all religions, the soul is considered immortal. In Christianity, there is a paradise for the wellbehaved and an awful place for the remaining group. Similarly in other Abrahamic religions, there are a good place and an evil place for the souls. The souls are treated somewhat differently in Hinduism and in Buddhism, but in both, they are thought to migrate after death. The Epicureans represent one of the few exceptions. “I was not; I have been; I am not; I do not care” was written on their gravestones. The ancient Indian school of thought, Charvaka, similarly, considered that the mind was a product of the body and perished with it. Except for these two examples, practically all religions have preached that the soul will survive after the death of the body.

Xue Fan also deals with the views of philosophers. Interestingly, up till the 19th century, practically all philosophers, including Plato, Aristotle and Descartes, thought that the soul would exist after the death of the body, although they speculated wildly about what the soul might consist of. The seat of the soul was mostly considered to be in the heart, although the brain was regarded by some as the seat of sensation and thought as early as the 5th century BCE. Descartes, belonging to the latter group, thought of the body as a machine and that the soul would control the body through the pineal

gland, as it was unpaired. Leonardo da Vinci placed the soul in the optic chiasm, while others placed it in the fourth ventricle. Aristotle reported that the soul (nous) would be installed in male fetuses 40 days after conception, while in female fetuses 90 days after!

The next interesting section of the book describes consciousness as the coexistence and integration of the many faculties of the brain, based on structure and function in neurobiological terms. Xue Fan provides a critical analysis of the many different theories of consciousness that have been presented over the years by philosophers, neuroscientists, computer scientists and physicists. Xue Fan also brings forward the essential role of the intralaminar group of thalamic nuclei and of the ascending reticular system in maintaining consciousness. The same areas are involved in the transition from wakefulness to sleep, an unconscious condition. These structures feed information to the relevant parts of the forebrain. In contrast, large parts of the cortex can be damaged bilaterally with maintained consciousness, whether they be the occipital, parietal, temporal or frontal lobes. In conclusion, consciousness is not dependent on any given part of the cortex. Even children with hydranencephaly, a severe condition in which the cerebral hemispheres are absent, display consciousness, although with reduced mental capacity.

Xue Fan also emphasizes the remarkable wealth of unconscious processing, which is not available to our conscious brain that only represents a very limited part of the overall operation of our nervous system. Take, for instance, the operation of the large neuronal networks in the gut, which we have no possibility to become aware of. The same applies to the hypothalamic control of, for instance, the water-salt balance, endocrine system, stress, temperature regulation and so forth. These are complex homeostatic systems, which depend on different sensors and feedback and effector systems. We are largely unaware of them, and it is only when there is a major problem that information is channeled to the conscious level for

action, such as when stomachache occurs or when we feel thirsty or hungry. These many remarkable control systems represent the larger part of our nervous system, and they operate without our interference. We cannot get access to their data even if our conscious part of the brain would try to. These aspects also relate to Freud’s early emphasis on the importance of the unconscious for the understanding of human behavior.

The brain does thus not let most of the rich information needed for our survival reach consciousness, which is processed by a refined homeostatic machinery within the nervous system out of our conscious control—maybe for good reasons. The conscious part of the brain is mainly reserved for actions in relation to the world around us. It of course also includes cognitive aspects, such as learning and memory of past events that can be used for future planning.

I have emphasized only a few important highlights in Xue Fan’s valuable and original contribution, which, however, is written in a much richer framework. It extends from the origin of life with chains of RNA to unicellular organisms sensing the surrounding world and finally to aspects of the universe. I recommend this unique book to everybody with an interest in life on Earth and beyond.

Stockholm, 23 March 2023 Sten Grillner

Distinguished Professor of Neurophysiology and Behavior

Former chair of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Nobel Institute for Neurophysiology, Karolinska Institute Royal Swedish Academy of Science

INTRODUCTION

The ultimate questions of consciousness, life and the universe

DOI: 10.4324/9781032636863-1

They say that just before we die, we would see our entire life flash in our mind in seconds, which would be the swan song of our brain, our final dream before death. We are not sure about that yet. We will see.

There are certain moments in life that determine who we are, leading us to understand what is essential and that all the rest is insignificant. Illness makes us conscious of the fragility of our body, our finitude and what life really means. The inexorable absence of loved ones makes us conscious of how visceral the connection with another being can be and how empty the world could feel, even full of wonders. At twilight in Africa, surrounded by an ancient land and grand mountains under a majestic dark blue sky, we become conscious of the weight of eons and of our deep connection with something much bigger than us. These are some moments leading to the ultimate questions of consciousness, life and the universe, which form the foundation of our existence.

The Sun, with a diameter of about 1.4 million kilometers, is more than a million times bigger than the Earth. However, about 9,500 light-years from the Earth, the red star UY Scuti is five billion times bigger than the Sun yet just looks like a tiny dot among several hundred billion stars in our galaxy, which itself appears a tiny dot among hundreds of billions of galaxies in the universe. Nevertheless, we, tiny creatures living on a speck of dust drifting in a seemingly infinite space can look beyond our little lives, conscious not only of ourselves but also of the vast universe.

About 13.5 billion years after the birth of the universe and 4.2 billion years after that of the Earth, dinosaurs began their 160 million years’ reign on Earth, more than 500 times longer than the history of Homosapiens, which is merely a blink of an eye in the history of the Earth. Today, all that is left of dinosaurs is mere bones. Yet the human mind can travel across billions of years, reason about the origin of the universe and contemplate these giant creatures once roaming the Earth.

Consciousness connects us to ourselves and the universe, the finite to the infinite, the ephemeral to the eternal. Where will it finally lead us? Who can tell the limits of ourselves and of our reality?

What is consciousness? What is life? What is the universe?

In search for answers, humans began to weave their tale of millions of years. Those ancient myths concealed a deep truth and gave birth to religion, philosophy and science. Then began the fivecentury quest for explaining consciousness, which confounded the greatest minds, from the ghost in the machine to the rise of experimental psychology to the era of consciousness. Philosophy tackles the hard problem, neuroscience tries to find the neural basis of consciousness, computer science regards computers as brains and investigates conscious machines, and quantum physics tries to discover an essential role for consciousness in the physical world. Yet a deep understanding of consciousness in relation to life and the universe is still missing.

Therefore, we will embark on a journey toward the ultimate understanding of consciousness by tracing its deep roots in life and the universe. The identification of the indispensable substratum of consciousness will lead to a clear redefinition of consciousness. The nonconscious processes of our body will reveal the hidden part of ourselves and our potential for expanding consciousness. The fourbillion-year evolution of life on Earth, from the first living molecular structures to the human organism, will tell how consciousness has

evolved as a fundamental process of life. To trace the origin of consciousness, we will try to understand what is life, which will lead us to revise the division of different patterns of matter into the conscious and the nonconscious, the living and the nonliving. To elucidate the ultimate origin and meaning of life and consciousness, we will try to understand what is the universe, which will lead us to investigate its origin and nature, from nothingness to vacuum fluctuations to the entire cosmos. Finally, we will use our acquired knowledge to build a path for expanding consciousness and improving the human condition.

This will be an exciting adventure, from the redefinition of consciousness to that of life, from the first living molecular structures to the human organism and civilization, from quantum fields and subatomic particles to the giant Cosmic Web, from an infinitesimal fraction of a second to the entire time span of the universe, from nothingness to the whole cosmos.

Philosophers ask fundamental questions about the nature and meaning of consciousness, life and the universe and examine them through logical reasoning. Scientists try to discover the fundamental laws governing consciousness, life and the universe in a quantified manner based on observation, experimentation and abstraction. Most people try to understand themselves, life and the world through their lifelong experience. Here, different paths converge, using different languages to try to express the same truth. As Stephen Hawking said,

[I]f we do discover a complete theory, it should in time be understandable in broad principle by everyone, not just a few scientists. Then we shall all, philosophers, scientists, and just ordinary people, be able to take part in the discussion of the question of why it is that we and the universe exist. If we find the answer to that, it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason for then we would know the mind of God.

(Hawking, 1988)

Everything we do in science and humanities is conditioned by our worldview, which is necessarily limited and shaped by our consciousness. It is only through the consensual regularities identified through our consciousness that we come to know the world and describe its properties. All research, including science, depends on consciousness—the foundation of all our knowledge. Even physical science does not deal with the world itself but a world of shadows, a world of models and conceptual constructs shaped by human consciousness and built through human perception and reasoning.

Facing the wide unknown of consciousness, life and the universe, we need to remain open but avoid unfounded speculations; we need vastly more knowledge from multiple disciplines in humanities and science to rise to this supreme challenge. For Erwin Schrödinger, a founder of quantum mechanics, his own pursuit of understanding life and consciousness was rooted in human innate longing for unified, all-embracing knowledge, and although the knowledge of multifarious branches is overwhelming, we should venture to embark on a synthesis of facts and theories and integrate the sum total of all that is known into a whole (Schrödinger, 2012). In this book, to explore the ultimate questions of consciousness, life and the universe, we leverage and integrate knowledge and methods from multiple disciplines in humanities and science, in particular philosophy, history, neuroscience, computer science, medicine, psychology, biotechnology, evolutionary science, biology, chemistry, physics and cosmology.

The common spirit of research must be changed. Any attempt to understand the universe should explain its relationship to consciousness and life, and any attempt to understand consciousness and life should trace their deep roots in the universe. The fundamental mission of humanities and science is to elucidate the place of humans in the universe, and any kind of research should be connected to the existence of every human being without

which it would be meaningless. Why build a science, a theory or a philosophy if it cannot be effective in expanding our consciousness and improving the human condition?

Humans are not the only beings that are conscious of their finitude. Some animals also possess this knowledge. Feeling their end approach, they will leave others and quietly die alone in an isolated place. There is grandeur in this choice. Humans have evolved more abilities to change the world and themselves. When the final moment comes, let it be a supernova.

Bibliography

Hawking, S.W. (1988) ABriefHistoryofTime:FromtheBigBangto BlackHoles. Toronto; New York: Bantam.

Schrödinger, E. (2012) What Is Life?: With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches. New York: Cambridge University Press.

A TALE OF MILLIONS OF YEARS

The origin of consciousness research (from the Old Stone Age to the Middle Ages)

DOI: 10.4324/9781032636863-2

One day, in the 4th century BCE, Zhuang Zhou, a Daoist philosopher, dreamed of himself being a butterfly, a free and insouciant psyche. Having suddenly awoken, pondering this oneiric experience, he wondered, “Am I Zhuang Zhou who dreamed of being a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming of being Zhuang Zhou?” Life is a tale.

Two millennia elapsed. One day, in the 19th century, on the other side of the world, a solitary Christian poet, deep in his soul, believed to see a world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wildflower. “Hold infinity in the palm of your hand, and eternity in an hour” (Blake, 1863), so we were told. Life is a tale.

Here is a tale, a tale of millions of years, a tale of love and loss, life and death, a tale of what it means to be human and a tale of our essence. From the collective evolutionary journey of humans, which began about two million years ago in Africa, to our individual life on Earth, which lasts for decades, it is our history.

Myth: facing the unknown and the abyss

The first humans, fragile in front of nature and constantly in fear of its caprices, struggled to survive from day to day starvation and

disasters, cold and darkness. They tried to explain the world and their own life, endure a precarious existence and the uncontrollable, protect what they loved and free themselves from suffering. The explanations that they imagined grew into stories about superpowers and gods, the creation of the world and the origin and fate of humans. These stories then became myths.

About 100,000 years ago, early Homo sapiens in the Levant covered their dead with red ocher, in the color of blood and life, and buried them with grave offerings, caring about their well-being in the afterlife (Hovers et al., 2003). About 60,000 years later, Aboriginal Australians also covered their dead with red ocher, symbolizing blood and the Great Goddess, hoping for the rebirth of their loved ones. They shared their being with their land, which they believed to have feelings. When they died, their spirits—the essence thought to define a person—returned to the land where they were born. Their land suffered and trees died. The spirits of the dead would eventually go to the Skyworld and enter the eternal Dreamtime—the real existence in which they could be connected to all their ancestors and the origin of time from which all lives emerged through birth and to which they would return after death to be reborn (Charlesworth et al., 1984). Death was part of this cycle of life, and the present life, prone to harshness and randomness, was merely a passing phase, a moment in eternity. Through rituals or during dreams, the spirit of a person could leave the body and enter the Dreamtime where time and space were boundless. The dead remained an integral part of the world of the living. Their spirits talked to their loved ones in dreams and could heal them if they were in pain.

Over 30,000 years ago, Cro-Magnons, early European modern humans, began to paint humans, animals and goddesses on the walls or ceilings of deep, dark caverns, the hidden Upper Paleolithic underground cathedrals for magical and spiritual rituals, such as the Chauvet Cave in France. Symbolic art was born. Haunted by the

spirits of the dead, Cro-Magnons tried to charm and control them through the worship of the goddess. Cro-Magnons buried their dead with food, clothing, tools and ornaments to prepare them for the journey to the spirit world, where they could live for all eternity with their ancestors and gods. The spirit left the body at death, and the body was buried in the womb of the earth, from which new life would emerge. The liberated spirit would ascend to heaven in the form of a bird.

Over 5,000 years ago, Sumer in Mesopotamia became the earliest literate civilization on Earth. Sumerians believed that the souls of the dead went to the underworld, a dark and drear cavern deep underground, where they dwelt in a weak, shadowy form of life and could only feed on dry dust. To allow their loved ones to drink in this land of no return, the families of the dead poured libations into their graves through a clay pipe. Sumerians tried to have as many children as possible, so they would not suffer from thirst after death. The vital importance attached to death and the afterlife was emphasized in the 4,000-year-old Sumerian poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest surviving great work of literature, which recounted the quest of a hero for immortality. Afflicted by the death of his friend Enkidu, the king Gilgamesh realized his own mortality and set off on a perilous journey to discover the secret of eternal life. “The life that you seek, you will not find. When the gods created mankind, death they imposed on mankind; life they kept in their power” (Jastrow and Clay, 1920), so he was finally told. Gilgamesh then became “He who saw the unknown,” “He who saw the abyss.” Sumerians built the earliest pyramids, ziggurats(Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Ziggurat of Ur (21st century BCE), the Neo-Sumerian Empire, Mesopotamia. Tell el-Muqayyar, Dhi Qar Province, Iraq

Source: Author: Kaufingdude. CC BY-SA 3.0

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

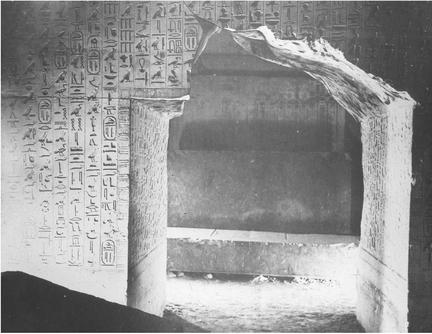

From the Old Kingdom, the “Age of the Pyramids,” established about 4,700 years ago, ancient Egyptians expended enormous energy and resources to ensure the survival of their souls after death, which formed the foundation of their civilization (Figure 1.2). They thought that the soul was composed of multiple parts and that each played a role in the dead’s access to the afterlife (Taylor, 2001). The first part was the khet, the physical body of the dead, which should be well preserved to allow the dead to reach the underworld of death and rebirth, ruled by Osiris, who had been murdered by his brother and then resurrected by his sister and wife, Isis. After the murder, Isis cried for her dead husband. The Nile flooded and then retreated, crops grew and died each year, and so did the human soul’s cycle of life, death and rebirth. In the Old Kingdom, only the pharaohs could be mummified and had access to an eternal existence in the afterlife. Their tombs, their palaces after death,

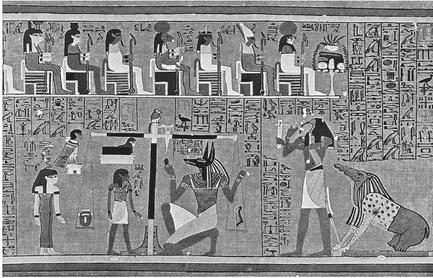

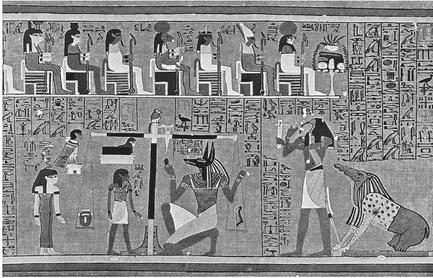

were protected by Pyramid Texts—complex spells to guide their souls to the afterlife (Figure 1.3). In the Middle Kingdom, all dead could be mummified, and their souls were protected by Coffin Texts and the BookoftheDeadto avoid the perils in the underworld to not die a second time and be reborn in the afterlife. The mummy would be reanimated in the underworld through funeral rites, and the most important step was to magically open the mouth of the mummy to allow the dead to breathe, eat, drink and speak, as well as to form the sah, the spiritual body that could exist in the afterlife. The name of the dead, the ren, was thought to be a part of the soul containing a person’s identity, which would live for as long as the name was spoken. Some tomb inscriptions implored passersby to speak aloud the names of the deceased to perpetuate their life. The ib, the heart, was created from one drop of blood from the heart of the child’s mother and was considered to be the seat of emotion, thought and memory. The ibwas an essential part of the soul and the key to the afterlife. The heart was preserved inside the mummy with a heart scarab atop—an amulet symbolizing Khepri, the morning manifestation of the sun god Ra, representing creation and rebirth. In the Hall of Two Truths in the underworld, the heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice, to determine the fate of the dead (Figure 1.4). If the Scale of Justice was balanced, the dead would go on a perilous journey to Aaru, the boundless reed fields in the east where the sun rose, a paradise with eternal bliss. If the heart, heavy with evil, outweighed the feather, it would be

FIGURE 1.2 Giza pyramid complex (2600–2500 BCE), Giza, Egypt

Source: Author: Yasser Nazmi. CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

FIGURE 1.3 A burial chamber with the walls covered with Pyramid Texts. Pyramid of Unas. 5th Dyn. Sakkara., n.d. Brooklyn Museum Archives (S10–08 Sakkara, image 9643)

Source: Author: Brooklyn Museum

devoured by Ammit, a demoness with a composite body combining crocodile, lion and hippopotamus—the three man-eating animals most feared by ancient Egyptians. This second death condemned the soul to an everlasting restlessness in the underworld. The ka, vital essence, was breathed by gods into humans at birth, and its departure caused death. Offerings of food and drink were made to ensure the survival of the kaafter death. The ba, personality, would be released through the “opening the mouth” ceremony to join the kaand form the akh, the spirit of the dead, which could exist in the afterlife and be invoked by prayers or written letters left in the tomb to help the dead’s living relatives. Each night, the bahad to return to its body in the tomb for being reenergized, so it could emerge again as the akhwith the morning sun, following the daily rebirth cycle of Ra. Each day, Ra traveled across the sky on his solar barge, the Boat of Millions of Years. At night, he descended into the underworld where he had to defeat Apep, a giant serpent and the Lord of Chaos, in order to be regenerated by Osiris and reborn at dawn. Only then would the sun rise again the next morning. The survival of the soul had never been granted forever. Instead, it must be gained through a perpetual struggle in the cycle of life, death and rebirth.

FIGURE 1.4 Weighing of the heart, the Egyptian Bookofthe Dead, Papyrus of Ani (19th Dynasty, c. 1250 BCE). Edited by A. Mayer in 1925.

CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en)

Source: Wellcome Images

Some 4,000 years ago, ancient Mayas began to develop their civilization. Like ancient Egyptians, they believed that the soul had multiple parts such as “breath,” “shadow” and “blood.” The loss of one or more parts would cause disease. A person’s soul had an animal or a natural phenomenon as companion and protector; it is the soul’s “co-essence.” Maya families buried their dead under their houses and made regular offerings. The afterlife was conceived of as either an underworld or a paradise such as “Flower Mountain.” Ancestral spirits were highly worshiped as protectors of their living descendants, capable of interceding with gods. Maya royalty also built great pyramids as palaces for their dead, although most of them served as temples to gods (Figure 1.5). Maya pyramids were also places for human sacrifice. In some rituals, a human was killed and skinned, and a priest, dressed in the skin of the sacrificed person, performed a ritual dance symbolizing rebirth.

Ancient Egyptian and Maya pyramids had their counterparts in ancient China. To ensure the survival of their souls in the afterlife, Chinese emperors built gigantic mausoleums. Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor who unified China in 221 BCE, began to build his mausoleum when he ascended to the throne at age 13, mobilizing 700,000 men over 38 years. The mausoleum included palaces, heavenly constellations, as well as rivers and the sea that were made of mercury and set to flow mechanically. At his burial, many of his wives were sacrificed to accompany him in the afterlife. About 7,000 life-sized terracotta statues of warriors as well as chariots and horses formed the Terracotta Army and were deployed in the mausoleum to protect the dead emperor in the afterlife (Figure 1.6). However, such a spectacular afterlife was only reserved for

emperors. Most of the souls of the dead went to “Yellow Springs,” the underworld. While digging wells deep underground, the water that first appeared was yellow in color and thus became the symbol of the underworld. On their journey to Yellow Springs, the souls were guided by Manjusaka or red spider lilies—the hell flowers blooming along the path (Figure 1.7). Manjusaka is poisonous, and its leaves and flowers could never meet: the leaves will fully appear only after the flowers have faded away, which symbolizes the ultimate separation and death. The souls would arrive at the River of Forgetfulness, above which was the Bridge of Sighs. On the bridge, Meng Po, the goddess of forgetfulness, would invite the souls to drink a potion prepared from all the tears that a person had shed in life: tears of birth, tears of old age, tears of suffering, tears of regret, tears of love and loss, tears in illness and tears of separation. Then, the souls could forget their past, cross the bridge and be reincarnated.

FIGURE 1.5 Maya pyramid, Temple of the Inscriptions (7th century), served as the tomb of K'inich Janaab Pakal I (603–683), Mexico

Source: Author: Jan Harenburg. CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en)

FIGURE 1.6 Terracotta Army, mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor (3rd century BCE) in Xi’an, China

Source: Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas, CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

FIGURE 1.7 Manjusaka or red spider lilies, the “hell flowers” that guide the souls of the dead to “Yellow Springs,” the ancient Chinese underworld

Source: Author: xe zna. CC BY-SA 3.0

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

The river of forgetfulness also existed in Hades, the ancient Greek underworld, and its name was Lethe. The souls of the dead drank water from the Lethe to forget their past lives and begin anew. Other rivers in Hades are the Styx, the river of hatred between life and death, which circled Hades seven times; the Acheron, the river of pain, over which Charon, the ferryman, would row the souls who paid him coins that had been placed under their tongue during burial; the Phlegethon, the river of fire leading to Tartarus, the hell beneath Hades for the evil souls, to which the Titans were banished by Zeus, opposite to blissful Elysium for the distinguished souls and the Asphodel Meadows for the ordinary. In front of the entrance to Hades lived some special gods: Phobos, god of fear; Limos, goddess of starvation; Nosoi, god of disease; Algos, gods of pain; Geras, god of old age; Penthos, god of grief; Hypnos, god of sleep; Thanatos, god of death. As souls in Hades were inactive, blood offerings intended to give them the vital essence were made to communicate with them. The souls in the underworld did not evolve and lived as mere shadows of their past lives. Homer, the author of the Iliadand the Odyssey, thus thought that the best fate for humans was never to be born because the greatness of life could never balance the price of death (Mystakidou et al., 2005).

About 1,000 years ago, the Inuit arose in western Alaska. Like ancient Egyptians and Mayas, they also thought that the soul had several parts, such as the life force, which would depart for the east after death as well as the personal spirit and the name soul, both of which could be reborn. Considered weak, the souls of children needed to be protected by their dead relatives, whose names were therefore carried by children to incorporate their souls. For the Inuit, all things had a soul, and the soul of killed animals or humans could take revenge. Life in the Arctic was harsh and prone to hazards. The Inuit lived constantly in fear of the wrath of nature and the spirits of the dead. Taboos and rituals were established to placate gods and spirits, and shamans became the mediators between the world of

humans and the world of gods and spirits. As the soul was thought to have originated in the sky, Inuits peered into northern lights to try to see the spirits of their loved ones dancing in the afterlife. When people died, their families observed three days of mourning and promised venison to their souls. The souls of the dead went to the underworld, where they would be purified for a year before traveling to the Land of the Moon, the land of eternal peace and bliss.

While the Inuit incorporated into themselves the souls of their dead by bearing their names, the Fore people in Papua New Guinea did so by consuming the corpses of their loved ones. Like the Inuit and the Australian Aborigines who also lived in Oceania, the Fore believed that their land was alive and created their ancestors. For them, the soul of each person had five parts (Whitfield et al., 2008). Immediately after death, the auma, the good qualities of a person, would travel across the land bidding farewell and depart for the land of the dead. To help the auma on this journey, the family left food and water with the body. The ama, similar to the auma but more powerful, would remain to assist the family until mortuary rituals had been completed. The aona, the abilities of a person, would be passed on to the deceased’s favorite child. The yesegi, the ancestral power of a person, would be transferred to the deceased’s children. The kwela, the pollution from the decomposition of the body, could harm the family if the obsequies were not conducted properly. Two or three days after death, the body would be cooked and consumed out of love and grief to incorporate the deceased’s soul in the family. This funerary cannibalism was the origin of Kuru, a form of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy caused by the transmission of prions, which also includes the “mad cow disease.” Kuru mostly affected Fore women and children because they usually consumed the brain, the organ in which infectious prions were most concentrated.