Human Rights and the UN Universal Periodic Review Mechanism

A Research Companion

Edited by Damian Etone, Amna Nazir and Alice Storey

First published 2024 by Routledge

4 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2024 selection and editorial matter, Damian Etone, Alice Storey and Amna Nazir; individual chapters, the contributors

The right of Damian Etone, Amna Nazir and Alice Storey to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Etone, Damian, editor. | Nazir, Amna, editor. | Storey, Alice, editor.

Title: Human rights and the Universal Periodic Review mechanism : a research companion / edited by Damian Etone, Amna Nazir, and Alice Storey.

Description: New York : Routledge, 2024. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023042791 | ISBN 9781032524184 (hardback) | ISBN 9781032542614 (paperback) | ISBN 9781003415992 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Human rights. | International law and human rights. | Human rights monitoring. | United Nations Human Rights Council. | United Nations—Commissions. | United Nations. General Assembly. Declaration on the Rights of Peasants (2017 December 18)

Classification: LCC K3240 .H8548 2024 | DDC 341.4/8—dc23/ eng/20231003

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023042791

ISBN: 978-1-032-52418-4 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-032-54261-4 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-003-41599-2 (ebk)

DOI: 10.4324/9781003415992

Typeset in Galliard by Apex CoVantage, LLC

R. MCMAHON AND TOMEK BOTWICZ

II

Relationship Between the UPR and Other Human Rights Mechanisms

5 Searching for Recommendation Alignment Across UN Human Rights Bodies

ELVIRA DOMÍNGUEZ-REDONDO AND RHONA SMITH

6 The Universal Periodic Review and Transitional Justice

DAMIAN ETONE

7 Universal Periodic Review Prospects for Promoting Support for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP)

LOUISA ASHLEY

III

State and Regional Engagement With the UPR Mechanism

8 Still a ‘Mutual Praise Society’? The African Group at the Universal Periodic Review

EDUARD JORDAAN

9 The Significance of the UPR in the Absence of a Regional Human Rights System: The Case of the Asia Pacific

FIONA MCGAUGHEY, AMY MAGUIRE, NATALIE BAIRD, JAMES GOMEZ, AND ROMULO NAYACALEVU

10 Unpacking the Enigma of Reporting Under the Universal Periodic Review: The Case of Three Southeast Asian Countries

KAZUO FUKUDA

11 Navigating Devolution at the UPR: The Case of the United Kingdom

Acronyms

CAT Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment

CED/CPED International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance

CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child

CRC-OPCP Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child

CRPD Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

CRPD-OP Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

CSOs Civil Society Organisations

CtAT Committee against Torture

CtED Committee on Enforced Disappearance

CtEDAW Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

CtERD Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

CtESCR Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

CtRC Committee on the Rights of the Child

CtRMW Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families

CtRPD Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Cycle 1 First Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review

Cycle 2 Second Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review

Cycle 3 Third Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review

Cycle 4 Fourth Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review

HRC Human Rights Council

HRCt Human Rights Committee

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICERD International Covenant on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

x Acronyms

ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

ICESCR-OP Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

ICRMW International Covenant on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families

NHRI National Human Rights Institutions

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

OHCHR Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

OPCAT Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment

SDG Sustainable Development Goals

SuR State under Review

UDHR Universal Declaration of Human Rights

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNDRIP United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

UNDROP United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UPR Universal Periodic Review

ICTY International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

ICTR International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

IHL International Humanitarian Law

Kalomoh Report Report of the assessment mission on the establishment of an international judicial commission of inquiry for Burundi

ACHPR African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement

SPLM Sudan People’s Liberation Movement

ARCSS Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan

JMEC Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission

SMART Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Result-Oriented and Time-Bound

ICC International Criminal Court

TNCs Transnational Corporations

TWAIL Third World Approaches to International Law

FSPI Federation of Indonesian Peasant Unions

EU European Union

FAO Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nation

WIPO

World Intellectual Property Organization

Contributors

Dr Louisa Ashley’s academic research focuses primarily upon international human rights. Her PhD evaluates the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in relation to states in crisis. As well as writing on the UPR, Louisa’s published research addresses the human rights impact of unilateral economic sanctions and human rights in times of conflict and post-conflict. Louisa has delivered conference papers in the United Kingdom and overseas. Prior to joining higher education in 2008, Louisa had trained as a solicitor with United Kingdom corporate law firm Walker Morris LLP joining the firm’s employment group upon qualification. As an employment lawyer, Louisa advised individual and corporate clients on a range of contentious and non-contentious matters and represented claimant and respondent clients at tribunal. Before becoming a lawyer, Louisa was one of the founders of award-winning, Leeds-based Unlimited Theatre and subsequently chaired its Board of Trustees until 2016.

Natalie Baird is Associate Professor at the University of Canterbury Faculty of Law and Co-Director of Postgraduate Studies and LLM (International Law and Politics). Her research interests include international human rights, refugee law, Pacific legal studies, and the scholarship of teaching and learning. In the human rights field, her research focuses on the relationship between international human rights law and mechanisms and domestic legal systems in New Zealand and the wider Pacific region. Natalie is a former member of the Amnesty International Aotearoa New Zealand Governance Team and a current member of the New Zealand Human Rights Review Tribunal.

Tomek Botwicz is an undergraduate student studying mathematics and philosophy at the University of Vermont, with a particular focus on harnessing information technologies to further human rights and civilizational development. He is also a part of the Lawrence Debate Union, the University of Vermont’s nationally-recognised debate team, on which he primarily competes in social justice and British parliamentary formats. Through the Honors College and Catamount Innovation Fund, Tomek has researched emerging technologies and ideologies,

focusing on the climate crisis, the future of democracies, and new political economies. Through his work with the UPR, he has been able to learn and contribute to a sui generis mechanism for holding human rights violators accountable.

Dr Frederick Cowell is Senior Lecturer in Law at Birkbeck. His research focus on the interpretation and enforcement of international human rights law and treaty withdrawal. Previously he was an advisor for an NGO helping civil society groups with UPR submissions.

Elvira Domínguez-Redondo is Professor in Law at Kingston University, United Kingdom. She has been a visiting scholar at Columbia University (USA) and University Alcalá de Henares (Spain). Prof. DomínguezRedondo has held different academic positions at Middlesex University (UK), Transnational Justice Institute (UK), the Irish Centre for Human Rights (Ireland), and University Carlos II (Spain). She has worked as a consultant for the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (Switzerland). She is an advisory group member of the Geneva (Switzerland)-based think-tank Universal Rights Group. Dr. Domínguez-Redondo is the author three monographs, In Defense of Politicization of Human Rights (2020), Minority Rights in Asia (with Prof. J Castellino, 2006), and Public Special Procedures of the UN Commission on Human Rights (2005). She has edited three books and authored a wide range of publications on international law and human rights.

Dr Damian Etone is Senior Lecturer in International Human Rights Law at the University of Stirling. He is Director for the MSc Programme in Human Rights and Diplomacy run in partnership with the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). Damian’s current research expertise includes international law, human rights implementation, UN human rights bodies, African human rights system, and transitional justice. Damian is the author of the book The Human Rights Council: The Impact of the Universal Periodic Review in Africa (Routledge 2020) that examined the engagement of African states with the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) mechanism. This book offered the first detailed analysis of the effectiveness of African states’ engagement with the UPR mechanism from 2008–2019.

Kazuo (Kaz) Fukuda is Associate Professor at Kansai Gaidai University in Osaka, Japan. Prior to pursuing an academic career, Kaz worked for the United Nations Development Programme in Lao PDR in charge of the rule of law portfolio and was involved extensively in the UPR process for nearly five years. He is the author of Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review as a Forum of Fighting for Borderline Recommendations? Lessons Learned from the Ground (NJHR, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2022). He received his PhD in law and democracy from the Maurer School of Law, Indiana University in the United States.

James Gomez is Regional Director at Asia Centre, where he provides strategic oversight for its development and regionalization. He currently oversees the Centre’s operations in both Thailand and Malaysia and is leading the partnerships for the Centre’s many activities in other parts of the region. He represents the Centre in media and public speaking engagements and builds relationships with key stakeholders around the world. James is a senior academic and university administrator at public and private universities, research institutes, and think tanks. James has worked at inter-governmental organisations, including the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, and international NGOs such as Friedrich Naumann Foundation and Amnesty International, where he managed global and regional teams on projects related to democracy and human rights. He has written extensively on topics such as democracy, civil society, human rights issues, and the role of technology in politics in Singapore and the broader Southeast Asian region.

Eduard Jordaan is Associate Professor in the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University where he mostly teaches on human rights and international relations. His articles have appeared in journals such as African Affairs, Global Governance, Human Rights Quarterly, International Studies Review, Journal of Human Rights Practice, and Review of International Studies. He is the author of South Africa and the UN Human Rights Council: The Fate of the Liberal Order (Routledge, 2020).

Michael Lane is Lecturer in Law at the University of Worcester. Michael teaches on various undergraduate and postgraduate law modules and supervises on the law PhD programme. Michael’s PhD, funded by UK Research and Innovation, explored the United Kingdom’s engagement with the UN’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Michael’s research has informed civil society organisations’ engagement with the UPR, reports to the United Nations, a series of capacity building events with the Equality and Human Rights Commission, and advice to Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights on its plans to scrutinise the UK’s UPR. His work has featured in the Nordic Journal of Human Rights, Human Rights Law Review, and the Journal of Human Rights Practice.

Amy Maguire is Associate Professor in International Law and Human Rights and Deputy Head of School (Research Training) at the University of Newcastle Law School. She is the founding and co-director of the Centre for Law and Social Justice, and the top-ranked author in international law and human rights for The Conversation. Her research concerns public international law, with particular focus on human rights institutions, self-determination, Indigenous rights, climate change, refugees and asylum seekers, and the death penalty. Until 2018, she served as co-chair of the Indigenous Rights Sub-Committee of Australian Lawyers for Human Rights,

where she worked with lawyers and students to promote the recognition and achievement of substantively equal rights for Indigenous peoples in Australia.

Fiona McGaughey is Associate Professor at the University of Western Australia Law School with a background in not-for-profit research and policy roles. She teaches international human rights law and co-ordinates the master of international law. Her primary research areas are international human rights law, United Nations bodies and the role of non-governmental organisations, human rights pedagogy, and higher education. Fiona has received grant funding for research on modern slavery and co-founded the UWA Modern Slavery Research Cluster in 2017. Fiona has published widely in leading Australian and international journals and her monograph Non-Governmental Organisations and the United Nations Human Rights System was published by Routledge in 2021.

Edward R. McMahon EdD is Visiting Associate Professor in the Middlebury College Political Science Department. He also holds a joint appointment as Adjunct Associate Professor in Community Development and Applied Economics, and Political Science, at the University of Vermont. He previously served as Dean’s Professor of Applied Politics and Director of the Center on Democratic Performance at Binghamton University. From 1989–1998, he directed African programs at the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs. He previously spent ten years as a foreign service officer with the U.S. Department of State. Dr. McMahon is a board member of UPR-Info, a human rights organization based in Geneva, Switzerland. He has consulted for numerous organizations in the international development field, including the Carter Center, USAID, the UN Development Program, the World Bank, and the International Foundation for Electoral Systems. Dr. McMahon has co-authored or co-edited three books and has contributed many journal articles and book chapters on a range of international governance and development issues.

Kathryn McNeilly is Professor of Law at Queen’s University Belfast School of Law. She is an expert in the areas of international human rights law and international legal theory. Professor McNeilly’s recent work has explored topics of international human rights monitoring, international legal history, international legal institutions, and the connection between international human rights law and time. Funding for her research includes award of a Leverhulme Research Fellowship (2019–2020) to undertake research on human rights monitoring, with a focus on the United Nations Universal Periodic Review. She is a member of the UKRI Talent and AHRC Peer Review Colleges, the Royal Irish Academy’s Ethical, Political, Legal and Philosophical Studies Committee, and an editorial board member of leading journals, including Human Rights Law Review.

Romulo Nayacalevu is a PhD scholar at the Australian National University and director for the R2P Pacific Project launched by the Asia-Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. Romulo is an experienced human rights practitioner, trainer, lawyer, and advisor to Pacific Island governments and NGOs, active in advocating for human rights promotion and protection, including the ratification of the Rome Statute among Pacific states, monitoring human rights, and strengthening legislation to protect civil freedoms. He was the program manager for the Governance and Legal Affairs program with the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) Secretariat in Vanuatu. Before then, he was also a senior human rights adviser with the Pacific Community, supporting 14 Pacific governments on a range of human rights issues. He spent over five years with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights: Pacific Regional Office and about three years in private practice in Suva.

Dr Amna Nazir is Reader in International Human Rights Law and Associate Director of the Centre for Human Rights at Birmingham City University. She also serves as a trustee for the United Nations Association – UK. Her research focuses on the UPR mechanism and Islamic law, both as separate and interlinked areas, exploring pertinent human rights issues such as capital punishment and freedom of religion. Amna actively participates in the UPR through submission of stakeholder reports to selected states’ review and engages in UPR Pre-sessions to directly advocate to governments on their countries’ human rights landscapes. She has undertaken extensive consulting and policy work with the UN, governments, civil society, and academic institutions. Most recently, she has been ranked in the top two candidates for appointment by the UN Human Rights Council for the role of special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief.

Dr Rhona Smith is Professor of International Human Rights at Newcastle University in the UK. She has worked on international human rights through diverse capacity building projects within academic and justice sectors, as well as by researching various aspects of human rights including the UN institutional framework.

Dr Alice Storey is Senior Lecturer in Law and Associate Director of the Centre for Human Rights at Birmingham City University, where she also leads the UPR Project at BCU. Her research focuses on the UPR mechanism and international human rights, predominantly from the perspective of women’s rights and the abolition of capital punishment. Through the UPR Project, Alice has engaged in practice with the UPR mechanism through submitting stakeholder reports to selected countries’ UPRs and taking part in UPR Pre-sessions, which involves direct engagement with UN government delegations from across the globe and other civil society organisations.

Contributors

Jon Yorke is Professor of Human Rights in the School of Law and the Director of the Centre for Human Rights (CHR). He has advised the United Nations and the European Union, and numerous governments including, Gambia, Myanmar, Spain, and the United Kingdom. He has worked on human rights cases in the United States, Sudan, and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and has submitted amicus curiae briefs in death penalty cases. He has been awarded multiple Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO) grants for projects to protect human rights in Sudan, and has worked on EU funded projects for the representation of capital defendants in foreign jurisdictions. He has recently worked on The UPR Project at BCU funded project ‘Universal Periodic Review 2022 – Civil Society Engagement’ which focuses upon the United Kingdom’s Fourth Cycle review in the UPR. This project has engaged UK parliamentarians, the legal profession, and CSOs.

Foreword

I welcome the publication of Human Rights and the UN Universal Periodic Review Mechanism: A Research Companion and strongly encourage the further development of the UPR Academic Network, leading to much greater attention to this mechanism also as part of the legal education in law schools. While a peer review – States to States – with a participation rate of 100 per cent –the UPR currently generates some 250 recommendations on average for each State reviewed. Many such recommendations reflect the content of concluding observations of Human Rights Treaty Bodies and recommendations made by Special Procedures Mandate Holders. The difference of UPR recommendations with those of other mechanisms, is that they are vetted by the government and, once accepted, following a process of consultations and sovereign decisions, offer entry points for action by the State – with the support of the UN and the international community. I have no doubt that the UPR is the best way to domesticate international human rights norms and to translate them into consistent laws and practices in a process involving different branches of the government, increasingly Parliament, and multiple other national stakeholders, including local and regional governments, NHRIs and CSOs.

At a High-Level panel on the UPR,1 during the last session of the Human Rights Council, on 1 March 2023, the UN Deputy Secretary-General clearly underlined that:

The Universal Periodic Review is a powerful and unique mechanism. . . . With the 4th cycle just initiated, the UPR is among our most impactful instruments to promote human rights as part of development efforts. . . . The United Nations Development System and Resident Coordinators stand ready to cooperate with all States in implementing UPR recommendations and together advance the SDGs with human rights at their core.

1 See Human Rights Council, ‘High-level Panel Discussion on UPR Voluntary Funds: Achievements, Good Practices and Lessons Learned Over the Past 15 Years and Optimized Support to States in the Implementation of Recommendations Emanating from the Fourth Cycle’ (1 March 2023) available at www.ohchr.org/en/news/2023/03/human-rights-councilholds-high-level-panel-discussion-voluntary-funds-universal accessed 15 July 2023.

With the continuing support of States – especially following the adoption, by consensus, of resolution HRC 51/30, last October, and the strong partnership with UNDP and the rest of the UN system, the UPR will be better placed to meet the technical cooperation gap and to ensure its consistent use as a problem-solving tool. Indeed, the UPR is the most effective instrument to promote human rights as part of development efforts.

The OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Chair, during the same High-Level panel, flagged that DAC members – when making recommendations to States that are of priority for their official development assistance – could facilitate follow up action to their accepted recommendations. Doing so systematically, and other forms of South-South cooperation, could indeed ensure the focus on enhanced implementation of the UPR 4th cycle would result into greater human rights action, everywhere. As UPR recommendations are increasingly becoming part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Frameworks (UNSDCFs), and UN Entities are taking responsibility of recommendations falling within their mandate, significant progress is being made on abolishing capital punishment; decriminalizing defamation; passing legislation to protect Human Rights Defenders (HRDs); ending all forms of discrimination; eliminating violence against women, including domestic violence; setting up a National Protection Mechanism (NPM) following OPCAT ratification. These are a few examples of the power of the UPR and I am convinced that more follow up action will emerge by better understanding and better using the UPR mechanism to strengthen protection, advance prevention and ensure the success of the SDGs.

1 May 2023

Gianni Magazzeni,Former UPR Chief, OHCHR, (1 May 2017 to 30 April 2023). Member of the Technical Advisory Group of WHO Universal Health and Preparedness Review (UHPR).

Photo of the Human Rights and Alliance of Civilizations Room, formerly Room XX at the UN Building in Geneva

Damian Etone, Amna Nazir, and Alice Storey

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is an innovative addition to the international human rights monitoring system. It is a state-led, peer-review mechanism employed by the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council (HRC) with the ‘improvement of the human rights situation on the ground’1 as a major objective. The UPR is designed to be a cooperative and non-confrontational mechanism that will ‘ensure universal coverage and equal treatment of all States’.2 The UPR is the only global human rights mechanism scrutinising the human rights records of all UN member states. From the inception of the UPR, this seemed utopian. Scholars and practitioners have sought to understand the mechanics of the UPR process and its potential to promote and protect human rights. After three cycles of the Universal Periodic Review (2008–2022) and the fourth cycle ongoing (2022–2027), there are important questions about how the UPR can mature and evolve into a robust international human rights monitoring mechanism. Some of the questions scholars have grappled with include how to conceptualise the UPR, the relationship between the UPR and other human rights mechanisms, state and regional engagement with the UPR, the quality and relevance of UPR recommendations, and opportunities for more effective NGO engagement. This edited collection attempts to engage with some of these issues through sustained analyses of all three cycles of the UPR mechanism.

This publication’s origins stem from the first workshop of the UPR Academic Network (UPRAN) held on 15 June 2022. UPRAN was founded by academics at Birmingham City University’s Centre for Human Rights (England) and the University of Stirling (Scotland) in June 2022. UPRAN brings together a global network of researchers and academics working on the HRC’s UPR mechanism to exchange research ideas, consider new perspectives, and explore under-researched aspects of the UPR process. This is the first academic

1 UNHRC, ‘Institution Building of the United Nations Human Rights Council’ HRC Res 5/1, UN HRC OR, 5th sess, Annex [IB] (18 June 2007) UN Doc A/HRC/RES/5/1, annex para 16.

2 ibid para 3.

Damian Etone, Amna Nazir, and Alice Storey

network set up to examine the effectiveness of the UPR mechanism, engage with theoretical and conceptual debates about its modus operandi, identify the lessons that can be drawn across different regions/states, and work to strengthen the research capacity of NGOs and other stakeholder engaging with the UPR mechanism. The work of UPRAN will provide a point of reference from which trends on the operation of the UPR mechanism can be identified and recommendations for improvements can be made.

This research companion is by no means exhaustive in examining the potential value of the UPR mechanism and there are several ‘dystopian’ aspects of the review process. In particular, the question of implementation/compliance with UPR recommendations is not significantly addressed in this edited collection and deserves more scholarly engagement. However, this research companion charts new conceptual and theoretical framework for the UPR mechanism (as an evolving process on the path to development; as utopia; as a source of international law). We also examine in this research companion the potential for the UPR to more effectively interact and enhance other human rights mechanisms through (i) a pilot case study of the extent of alignment between UPR recommendations and the recommendations by treaty bodies and special procedures; (ii) how the UPR can support transitional justice processes in post conflict states; and (iii) the prospects for the UPR to promote support for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP). These are previously unexamined aspects of the UPR mechanism which our research companion brings visibility to. Equally significant in this research companion is the examination of specific states and regional engagement with the UPR, underscoring the significant value it provides to the Asian Pacific region where there’s a lack of a regional human rights system, to devolved governments within states, and unpacking the importance of the substance of the three documents used as the basis for the review. The limitations and challenges the UPR faces are not lost to the authors of this research companion. Several ‘dystopian’ practices in the UPR mechanism are highlighted throughout the collection and the persistent tendency for the review process to devolve into a ‘mutual praise society’ is also noted.

This research companion draws on the expertise of an interdisciplinary group of scholars bringing in distinct contributions from multiple disciplinary backgrounds including international law and international politics.3

The Establishment of the UPR

The UPR was established in 2006 together with the HRC.4 The establishment and design of the UPR as a mechanism of the HRC can be better understood

3 We would like to thank Rebecca Erekaha for the editorial assistance provided and for helping to maintain UPRAN website at https://upracademicnetwork.org/

4 UNGA Res 60/251, UN GAOR, 60th sess, 72nd plen mtg, Agenda Items 46 and 120 (3rd April 2006) UN Doc A/Res/60/251 (‘Resolution 60/251’) para 5(e).

in the context of the failures of the Commission for Human Rights (CHR). The CHR was the predecessor of the HRC established under Article 68 of the UN Charter, entrusted with the international promotion and protection of human rights.5 Whilst the CHR recorded significant achievements in its 60 years of existence, including drafting the UDHR and several international human rights treaties,6 its work subsequently came under severe criticism for lack of credibility and professionalism. These criticisms included selectivity in human rights scrutiny (unequal treatment of states) and acting as a shield masking the human rights abuses of certain member states.7 In 2004, a report by the UN High Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change addressed the problems with the CHR and underscored the need for reform.8 It was deemed necessary for the UN to chart a new direction in international human rights monitoring. The UPR represented this new approach.

The HRC and UPR were both created under the UN General Assembly Resolution 60/251. The HRC was established as an inter-governmental body within the UN comprising of 47 states and responsible for the promotion and protection of human rights across the globe. It has a mandate to undertake a ‘universal periodic review’ of the human rights performance of all states.9 The UPR was designed to be a cooperative peer-review mechanism that ensures universality and equal treatment in the assessment of the human rights performance of every state, whilst also complementing but not duplicating other human rights mechanisms.10 The foundational principles of the UPR therefore included ‘cooperation’, ‘equal treatment’, and ‘complementarity’.11

The Guiding Principles for the UPR

According to Resolution 5/1 of HRC, the UPR process is guided by 13 core principles which are reaffirmed in HRC Resolution 16/21. These are:

(a) Promote the universality, interdependence, indivisibility, and interrelatedness of all human rights;

(b) Be a cooperative mechanism based on objective and reliable information and on interactive dialogue;

5 United Nations, ‘Charter of the United Nations’ (24 October 1945), 1 UNTS XVI, Article 68.

6 For some detailed analysis of the work of the CHR and the transition to the HRC see Philip Alston, ‘Reconceiving the UN Human Rights Regime: Challenges Confronting the New UN Human Rights Council’ (2006) 7(1) Melbourne Journal of International Law 185; UN General Assembly, ‘Report of the High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change, Entitled “A More Secure World: Our Shared Responsibility”’ (2 December 2004) UN Doc A/59/565, 282–91.

7 ibid.

8 UNGA (n 5), 282–91.

9 UNHRC (n 1).

10 ibid para 3(f).

11 ibid.

Etone, Amna Nazir, and Alice Storey

(c) Ensure universal coverage and equal treatment of all States;

(d) Be an intergovernmental process, United Nations Member-driven, and action-oriented;

(e) Fully involve the country under review;

(f) Complement and not duplicate other human rights mechanisms, thus representing an added value;

(g) Be conducted in an objective, transparent, non-selective, constructive, non-confrontational, and non-politicised manner;

(h) Not be overly burdensome to the concerned State or to the agenda of the Council;

(i) Not be overly long; it should be realistic and not absorb a disproportionate amount of time, human, and financial resources;

(j) Not diminish the Council’s capacity to respond to urgent human rights situations;

(k) Fully integrate a gender perspective;

(l) Without prejudice to the obligations contained in the elements provided for in the basis of review, take into account the level of development and specificities of countries;

(m) Ensure the participation of all relevant stakeholders, including non-governmental organisations and national human rights institutions.

The ultimate goal for the UPR is the improvement of the human rights situation at the domestic level.

Modalities and Operations of the UPR Process

Resolution 5/1 of the HRC, often referred to as the institution-building package, sets out the modalities for the UPR process.12 This was revised in 2011 by HRC Resolution 16/21 which, amongst other things, extended the periodicity of the review from four years to four and a half years.13 The workings of the UPR can be understood in terms of process, documentation, and actors.

Process

All UN member states are reviewed every four and a half years. Forty-two states undergo the review each year. Reviews takes place within a working group, where 14 states are reviewed per session and there are three, two-week sessions per year. These sessions include the 47 HRC members, although any member or observer state of the United Nations may also take part in the

12 ibid paras 18–25.

13 UNHRC, ‘Review of the Work and Functioning of the Human Rights Council’ HRC Resolution 16/21, HRC 16th sess, Agenda Item 1 (12 April 2011) UN Doc A/HRC/RES/16/21 (‘Resolution 16/21’) para 3.

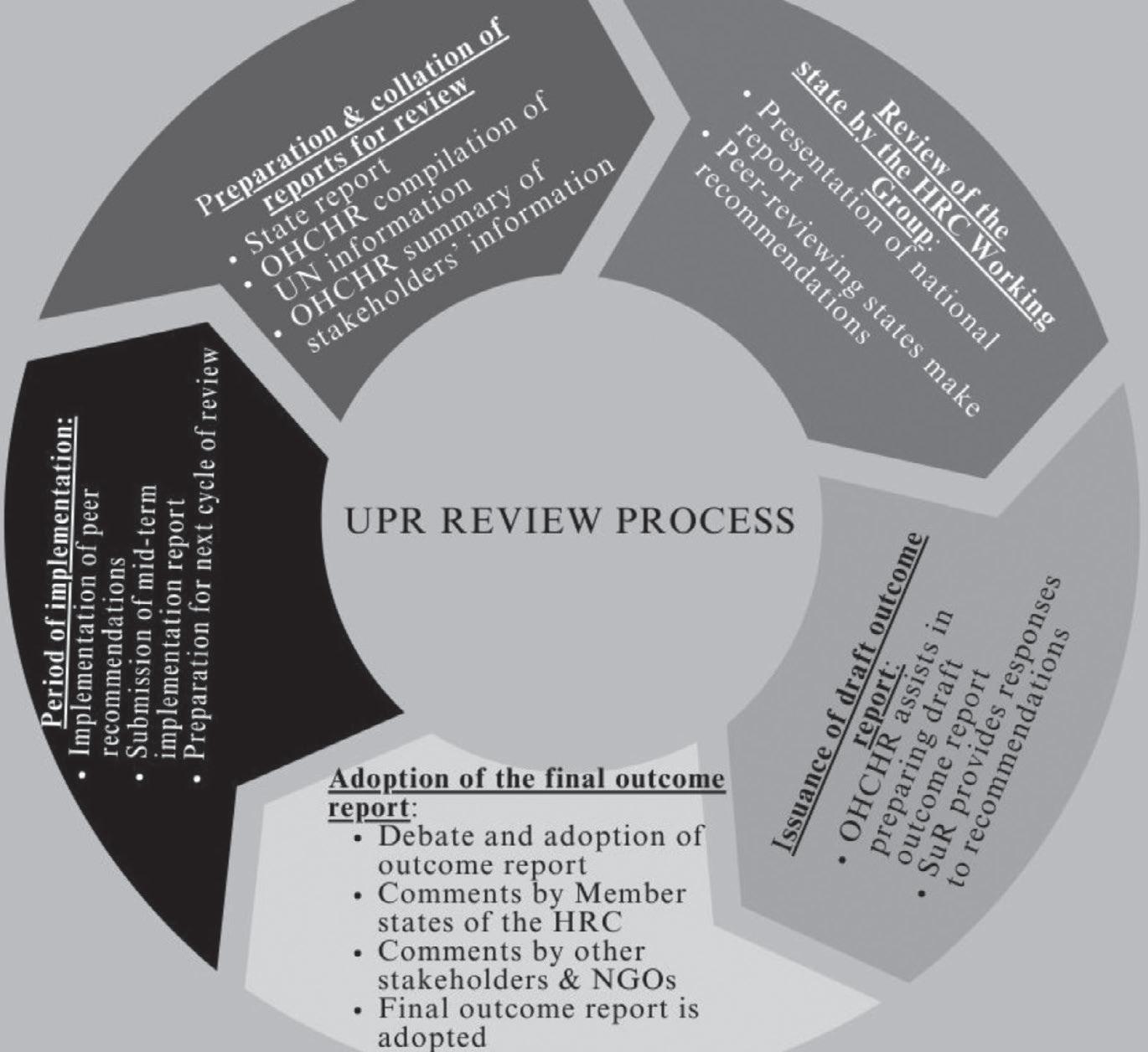

process. There are several distinct phases of the review process. These include (i) preparation and collation of reports for review; (ii) review of the state by the HRC Working Group; (iii) issuance of a draft outcome report; (iv) adoption of the final outcome report; and (v) period of implementation.

The origins, design, and operations of the UPR process can help shape our conceptualisation of the UPR as a source of international law (Chapter 3), a manifestation of utopia in theory and practice (Chapter 2), and as an ‘evolving process’ underpinned by cyclicality and linearity (Chapter 1). It can also help us understand the potential of the UPR to influence human rights changes in the absence of a regional human rights system (Chapter 9), the opportunities for cooperation between devolved governments at the national level (Chapter 11), but also the tendency to slip into a ‘mutual admiration society’ (Chapter 8). The operation of the UPR for three cycles allow us to question its ability to complement other human rights mechanisms and processes (Chapters 5, 6, and 7).

UPR Cycle

Documentation and Actors

To ensure the principles of universality, equal treatment, and complementarity, the UPR engages a range of actors within the UPR process, including member states, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), other UN bodies and agencies, civil society and NGOs, the ‘troika’, and national parliaments.

Member states are the core focus of the UPR, whether acting as a State under Review (SuR) or a peer-reviewing state. A SuR is expected to provide key information regarding its protection and promotion of human rights, including an update on implementation of recommendations from the previous cycle, through its submission of a National Report in advance of the review. The SuR will also attend the HRC for the review itself and will respond to/implement recommendations. Peer-reviewing states engage with the SuR by asking questions in advance of the review, engaging with the interactive dialogue during the review (including making recommendations), and commenting on the SuR’s performance during the adoption stage. States also have a role to play in each review as the designated ‘troika’. Three states of the HRC are selected to form the troika to assist in facilitating each state review, supporting activities such as ensuring advance questions are submitted to the SuR and drafting the Report of the Working Group.

The OHCHR acts as the ‘Secretariat’ of the UPR. One of its most vital roles is summarising important information that forms two of the three underpinning reports for each review: (i) the Compilation of UN Information and (ii) Summary of Stakeholders’ Information. For the Compilation Report, the OHCHR will identify and summarise pertinent information, recommendations, and concluding observations from other UN bodies and agencies (including the treaty bodies, special procedures, and the UN Secretary-General, etc.). In terms of the Stakeholder Summary, civil society organisations (CSOs) are permitted to engage with the UPR as ‘stakeholders’. This includes allowing stakeholders to submit ‘credible and reliable’ information to a state’s UPR, setting out key themes relating to human rights, highlighting positives, areas of concern, action on recommendations from the previous cycle, and they can also provide their own recommendations. The OHCHR will read all stakeholder submissions for each UPR, synthesising them into the final Stakeholder Summary document, with all individual submissions being available on each state’s UPR webpage. Stakeholders should also be engaged by governments in a ‘national consultation’ when they are drafting the National Report and equally should be involved with the implementation of recommendations, where appropriate.

National parliament processes and parliamentarians are also vital to the success of the UPR, and to ensure the mechanism is meeting its mandate to ensure human rights protection and promotion on the ground. Parliament should be involved in the implementation of recommendations, for example, through law reform and drafting and enacting human rights policies.

Structure of the Book

A central theme running through the chapters of this book is that the UPR, despite its limitations, is an important human rights mechanism with the potential to evolve over time into an effective cooperative tool for monitoring and encouraging implementation of human rights. Contributions in this book are organised into three parts.

Part I consists of four chapters focused on a variety of conceptual and theoretical approaches to understanding the UPR. Kathryn McNeilly’s Chapter 1 embraces the conceptual tools of cyclicality and linearity to argue that the UPR is as an ‘evolving process’ propelled by its cyclical activities that places the UPR on a continuous linear path of development. This chapter examines what exactly this evolution has involved across procedural and operational aspects, as well as how it can be understood holistically. It engages with the UPR’s formal procedural modalities – including amendments to timetabling, periodicity, documentation, the Working Group session, and participation of civil society stakeholders – and development of its operation. The chapter provides significant insights into the themes that have characterised the UPR’s evolution across cycles, as well as its status as a process that stands to evolve further.

In Chapter 2, Amna Nazir, Alice Storey, and Jon Yorke, introduce a new conceptual lens, viewing the operation of the UPR as a form of translating utopian theory into practice for international human rights. According to the authors, understanding the UPR as a practice of utopia brings together multiple processes (including the treaty bodies, special procedures, UNSDGs, etc.) for promoting global change. They contend that viewing the UPR’s modalities through a utopian lens leads to the recognition of the spectrum of opportunities for the protection of human rights and that, through the UPR, the UN offers a way out of dystopian practices which are curtailing and violating human rights.

Frederick Cowell’s Chapter 3 investigates whether the UPR can be understood as an international law-making process. This chapter unpacks some of the assumptions underlying theories on the sources of law and argues that the UPR is a law-making process underpinned by three key features – dialogue, structural reputation, and equality of participation.

In Chapter 4, Edward R. McMahon and Tomek Botwicz undertake a quantitative analysis of UPR recommendations across the first three cycles to determine if the trends observed in the earlier cycles have continued and the lessons learned on how the UPR has evolved as a global mechanism for the promotion of human rights. McMahon and Botwicz examine the value of the UPR process against key metrics including the number of recommendations made, state responses to the recommendations, and the action category of the recommendations. They contend that the UPR process overall has substantive merit and that there is a correlation between state adherence to democratic values and a more robust utilisation of the UPR process.

Etone, Amna Nazir, and Alice Storey

Part II of this collection examines the relationship between the UPR and other mechanisms. In Chapter 5, Elvira Domínguez-Redondo and Rhona Smith explore the congruence, or otherwise, of recommendations made to states by the UPR, treaty bodies, and special procedures. Through a pilotstyle study of five states, the authors examine thematic recommendations each state received during the period of the third cycle of the UPR. They find relative congr uence of recommendations, but also some evidence of disparities in the datasets emerged. The authors conclude that a larger-scale project on the alignment of recommendations could provide further insights into the consensus (or otherwise) around specific themes and may be useful in terms of strengthening follow-up and even in prioritising national level implementation efforts.

Damian Etone’s Chapter 6 examines the relationship between the UPR and transitional justice, and the extent to which the UPR mechanism can promote transitional justice processes in post conflict societies. The chapter develops a framework for assessing the relationship between the UPR and transitional justice and undertakes the first empirical analysis of that relationship with a focus on Burundi and South Sudan. Etone argues that the UPR can play a significant role in promoting transitional justice measures, reinforcing, and increasing the visibility of recommendations from other international mechanisms, and promoting accountability for human rights atrocities.

The final chapter in Part II, Chapter 7 by Louisa Ashley, provides the first comprehensive assessment of the capacity of the UPR to operate as a vehicle for the promotion and implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP). Ashley addresses two key issues: whether the UPR is an apt vehicle via which to, firstly, increase support for UNDROP amongst those states that abstained or voted against it and, secondly, to secure implementation by those that voted in favour, and if so, how. The discussion in this chapter considers the background to UNDROP and factors that might contribute to states withholding support.

Part III of this book assesses how states/regional groupings have engaged with the UPR mechanism and what lessons could be learned for the future of the mechanism. In Chapter 8, Fiona McGaughey, Amy Maguire, Natalie Baird, James Gomez, and Romulo Nayacalevu, deploy a postcolonial theoretical framework and draw on empirical data to analyse the engagement, performance, and influence of states within the Asia Pacific region in the UPR. McGaughey et al argue that the lack of a regional human rights mechanism in the Asia Pacific region makes the UPR simultaneously more significant and less substantial. They identify dystopian elements of ritualism and performativity in the UPR engagement of states within the region but also the potential for the UPR to influence domestic human rights changes, where there is state willingness to improve on its human rights record.

This claim about the lack of willingness to improve domestic human rights and assertions of ritualism is re-examined by Eduard Jordaan in Chapter 9 in

the context of African states’ engagement with the UPR. This chapter evaluates the strength of African states’ reviews over the last three UPR cycles to determine if the African group is still a ‘mutual praise society’. Specifically, Jordaan examines the extent to which African states are willing to address violations of political rights in countries under review.

Kazuo Fakuda’s Chapter 10 undertakes one of the first detailed analyses of the contents of the core documents/reports that form the basis of the UPR. Fukuda argues that an investigation of the data contained in these documents can help unpack the essence of the UPR and shed light on its strengths and weaknesses. Focusing on the UPR engagement of Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Thailand, and Vietnam, the author finds that the contents of three core reports, in different instances, were incomprehensive in issue coverage, dissociated from UPR recommendations, did not directly report on implementation, and failed to meet technical guidelines.

The final chapter by Michael Lane makes a unique contribution to UPR scholarship by examining the significance of the UPR at the sub-national level. The chapter considers the challenges that devolution poses for the United Kingdom’s engagement with each stage of the UPR. This includes, navigating the ‘broad consultation’ process in advance of reviews; how recommendations might (or might not) be appropriately targeted to devolved administrations; and the role of devolved administrations in responding to and implementing recommendations.