Introduction

Manyyearsagothewriterincompanywithanaccidentalpartyof travellerswasgazingonacataractofgreatheight,breadth,and impetuosity,thesummitofwhichappearedtoblendwiththesky andclouds,whilethelowerpartwashiddenbyrocksandtrees;and onhisobserving,thatitwasinthestrictestsenseoftheword,a sublimeobject,aladypresentassentedwithwarmthtotheremark, adding—“Yes!anditisnotonlysublime,butbeautifulandabsolutely pretty.

SamuelTaylorColeridge, EssaysonthePrinciples ofGenialCriticism (1814)

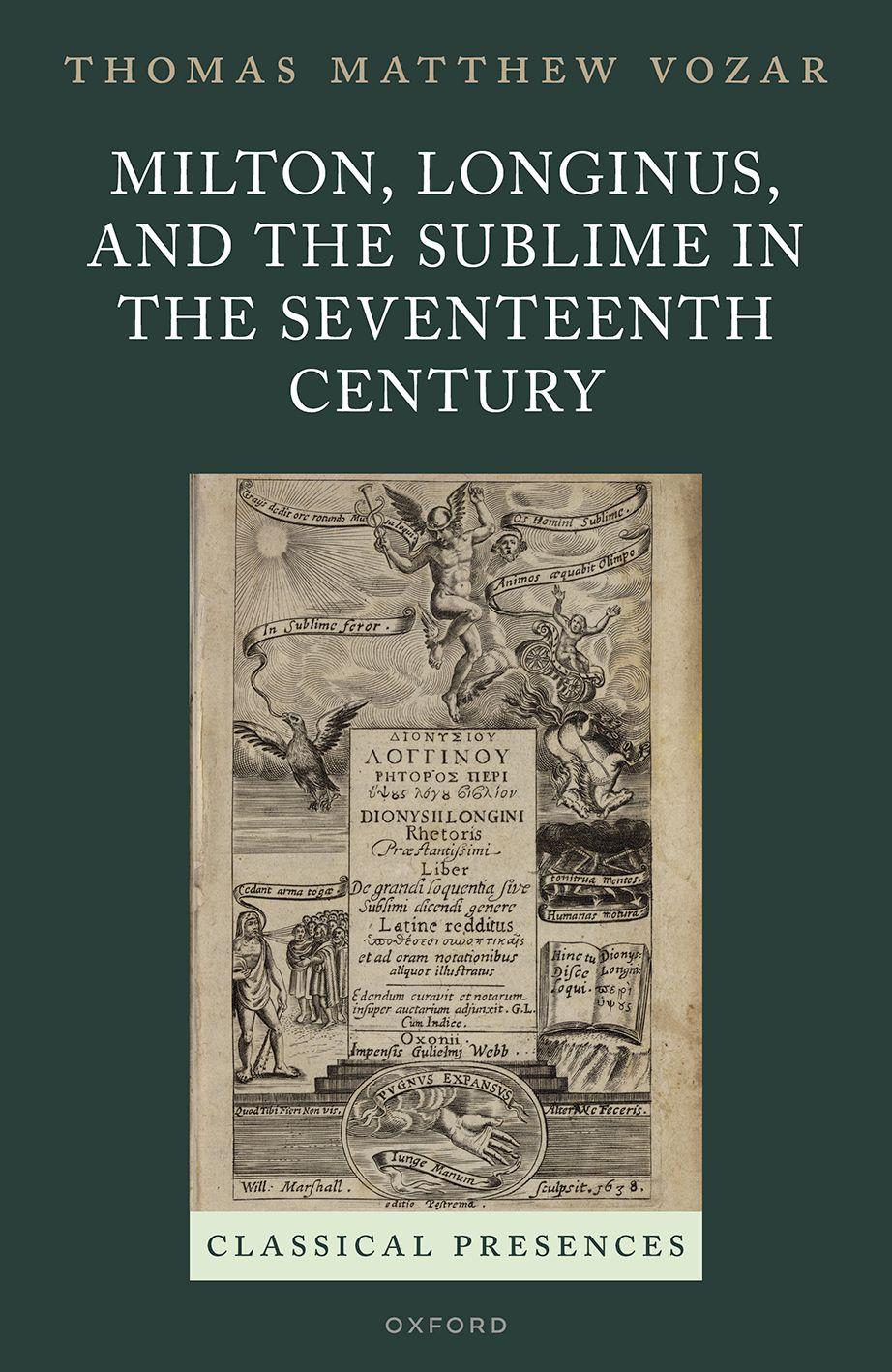

Eversincehisdeathin1674theworksofJohnMiltonhavebeenaccordedthe epithet sublime somuchsothatjustoveracenturylaterMaryWollstonecraft complainedthatshewas “sickofhearingofthesublimityofMilton,” whichshe comparedtotheclichéof “theoriginal,untaughtgeniusofShakespear.”²Ifthe sublimityofMiltonistomeananythingmorethanabanalaffirmationofliterary greatness,thesublimemustbeconsideredasaconceptgroundedwithina particularcontext,thatofEuropeanculturalandintellectualhistory.Theconventionalhistoriographyofthesublime,asrepresentedmostrecentlybyRobert Doran’ s TheTheoryoftheSublimefromLonginustoKant (2015),beginswith theGreektreatiseentitled Perihupsous,usuallytranslatedintoEnglishas Onthe Sublime andtraditionallyascribedtoacertainDionysiusLonginus;³resumeswith the1674translationofLonginusbytheFrenchpoet-criticNicolasBoileau;and thenproceedstoeighteenth-centurywritingsonthesublimebythelikesof EdmundBurkeandImmanuelKantwiththeadventofphilosophicalaesthetics.⁴ Thereremainshere,itwillbenoticed,adiscontinuityofsome fifteenhundred years:theimpressionisthatLonginuswasthesoleandanomalousinventorofthe

¹Coleridge1995:362.²Wollstonecraft1787:52.

³OnthedateandauthorshipofthistreatiseseeChapter1.IusethenameLonginusalone(or DionysiusLonginus)torefertotheauthorofthiswork;thethird-centuryphilologistandphilosopher CassiusLonginusisreferredtobyhisfullname.

⁴ ThoughDoran2015,tobefair,doesnotpurporttopresentacomprehensivehistoryofthe sublime,butmorespecificallyahistoryofthe “theory” ofthesublime,Iconsiderthestagesofhis narrativerepresentativeoftheconventionalview.ThesameleapfromLonginustoBoileauismadeby Shaw2006andFritz2011.OnBurke’suseofMilton,esp.inrelationtoLucretius,seeBullard2012;on KantandMiltonseeTisch1968;Budick2010;Shore2014.

Milton,Longinus,andtheSublimeintheSeventeenthCentury.ThomasMatthewVozar,OxfordUniversityPress. ©ThomasMatthewVozar2023.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198875949.003.0001

ideaofthesublime,andthathistreatisewasallbutunknownuntildiffused throughouttheEuropeanrepublicoflettersbyBoileau,therebyenablingthe developmentofthephilosophicaltheoryofthesublimeintheEnlightenment. Ifthispictureisright,itbecomesdifficulttoseehowMiltonhimselfcouldhave hadanynotionofthesublime.MiltonmentionsLonginusonlyonce,recommending “agracefullandornateRhetoricktaughtoutoftheruleof Plato , Aristotle, Phalereus, Cicero, Hermogenes, Longinus” (CPW 2:402–3)inhistract Of Education,andforalongtimescholarshavemostlyyieldedtotheviewSamuel Monkpronouncedalmostacenturyago,thatMilton “seemsnottohavefelt Longinus’scharm. ”⁵ IfLonginuswasjustanameMiltontackedontoalistof classicalauthoritiesandtheideaofthesublimewasnototherwisedevelopeduntil afterhislifetime,Miltoncouldnothavehadanyconceptionofthesublime.Itis perhapsnotsurprisingthenthat,asidefromtheoccasionalpassingreferenceto Longinus,scholarshiponthesubject,whenithasnotstrayedintoanachronism, hasbeenlimitedalmostentirelytothestudyofMilton’sreception.⁶ Oncea commonplace,Milton’ssublimityhasnowbeensothoroughlyeclipsedthat arecentmonographonMiltonandtheineffable whichonemightexpectto provokeatleastaperfunctoryallusiontotheideaofthesublime makesno mentionofit,⁷ nordoanyofthevariousMiltoniccompanions,readingguides, andsubjectencyclopediasincurrentuse.⁸ Giventhisstateofaffairs,onewould seemtohavegoodcausetosurrendertothejudgmentthattheMiltonicsublimeis, inthewordsofLeslieMoore, “ a fictionofeighteenth-centurycriticism. ”⁹

Advancesinscholarship,however,haverenderedobsoletetheconventional viewofthehistoryofthesublimeuponwhichthisjudgmentdepends.While LonginuswascertainlylessfamiliartoRenaissancereadersthansomeotherGreek authors,evidencehassteadilyaccumulatedthathistreatiseattractedtheattention ofanumberofhumanists,poets,clergymen,artists,andmanyothersinthe sixteenthandseventeenthcenturies,even,toamuchlesserextent,beforethe

⁵ Monk1935:20.SeerecentlyHale2016a:206(butcf.Hale2022,citingmyresearch);Martindale 2012a:89n.93;Martindale2012b:854.

⁶ ForpassingreferencestoLonginusseeBurrow1999:496–7;Shore2012:102–3;Dobranski2015 passim;Goldstein2017:175,205n.81.AsSedley2005:158n.20observes: “Theoreticallyadvanced discussionsofthesublimethatdoconsiderauthorspriortoBoileau(e.g.,Milton)stilllookthroughthe lensofeighteenth-centurydiscussions.” SedleycitesKnapp1985andKahn1992asexamplesofsuch anachronism,towhichonemayaddforexampleTeskey2015:409–35.Cheney2018b:9n.16declares: “Aloneamongearlymodernauthors,Milton’ssublimityhasbeenmuchdiscussed.” Nearlyallthe exampleshegives,however,andothershedoesnot,arestudiesofthesublimeinrelationtoMilton’ s reception.Theseindeedarelegion,including,butnotlimitedto,Nelson1963:39–73;Morris1972 passim;Moore1990;vonMaltzahn2001;Budick2010;Crawford2011;Martindale2012a:71–8; Leonard2013passim;Sugimura2014a;Gigante2016;Hoxby2016.

⁷ Reisner2009.IamthinkinghereforexampleofLong. Subl.9.2,onthesublimityofAjax’ssilence intheunderworldofthe Odyssey.

⁸ InmysurveyofthesematerialsIhavefoundonlypassingmentionsofthesublime,andthen strictlyasitrelatestoMilton’sreception,inDanielson1999:161,245,247;Corns2012a:80–1;Schwartz 2014:198,201;Corns2016:552–3,576;andnoneatallinReisner2011.

⁹ Moore1990:2.

1554 editioprinceps ofFrancescoRobortello.¹⁰ Moreover,thoughthe Perihupsous istheonlysurvivingancientworkofrhetoricdevotedtothesublime,itis increasinglyappreciatedthattheideaofthesublimeinrhetoricwasnotlimited toLonginusbutwasinsteadmuchmorewidespreadinboththeclassicalrhetorical traditionanditslaterreception.¹¹Lastly,andperhapsmostcrucially,theancient ideaofthesublime,asJamesPorter’smagisterial TheSublimeinAntiquity (2016) hasshown,wasnotrestrictedtorhetoricbutextendedintovariousdiscoursesand domainsofinquiry,includingnaturalhistoryandphilosophy.¹²

Whenallofthisistakenintoaccount,thenotionthatMiltonwouldhavehad anideaofthesublimebeginstoseemlesslikeachronologicalimpossibilitythana nearcertainty.Thusfar,however,Miltonicscholarshiphasnotfullyassimilated thisemergingnewunderstandingofthehistoryofthesublimeasapre-aesthetic concept(i.e.asaconceptpredatingeighteenth-centuryaesthetics).¹³Despitesome importantstudiesbythelikesofAnnabelPattersonandDavidNorbrook,who havearguedthatthepoliticalresonancesofLonginusintheseventeenthcentury wouldhaveappealedtotherepublicanMilton,thesubjectofMiltonandthe sublimeinaseventeenth-centurycontexthasnotyetreceivedthecomprehensive treatmentitdeserves.¹⁴ Itisthetaskofthepresentstudytoamelioratethisstatus

¹⁰ FollowingthebibliographicalresearchofWeinberg1950,1962,and1971,anumberofstudies haveappearedconcernedwiththedisseminationofLonginusandtheinfluenceofLonginianideas beforeBoileauinItaly(Costa1984a,1984b,1985,1987a,1987b,1994,2003;Mazzucchi1989;Lehtonen 2016and2019;Refini2012and2016),inFrance(Fumaroli1986;Gabe1991;Gilby2006;Gilby2016), intheNetherlands(Bussels2016;Nativel2016;vanOostveldtandBussels2016;Jansen2016and2019), andinEngland(Ringler1938;Spencer1957;Cheney2009a,2011,2018a,2018b;Lehtonen2016; McDowell2008:Ch.5passim;andLazarus2021);seealsothepaperscollectedinvanEcketal.2012.

¹¹Fumaroli2002;Shuger1988;Goyet1996;Hendrix2005.

¹²Porter2016isthemostthoroughandsignificant,butstudiesspecificallyoftheLucretiannaturalphilosophicalsublimehavebeenfruitfulaswell,includinge.g.Conte1966and1994:9–52;Hardie 2009;andPorter2003,2007.SeealsothepaperscollectedinJaeger2010aonthemedievalconception ofthesublime.

¹³Onthesublimeasaconceptthatdevelopedconcomitantlywithaestheticsitselfintheeighteenth centuryseedeBolla1989,esp.27–102.

¹⁴ Patterson1993:258–72 firstdrewattentiontothepoliticalaspectoftheLonginiansublimein relationtoMilton,whichNorbrook1999:137laterdubbedits “republicanaccent.” Stark2003detects Longinus’ conceptof psuchrotēs (“falsegrandeur,” literally “frigidity”)intherhetoricofSatanandother fallenangelsin PL.Feinstein1998considersMilton’suseoftheword sublime,includingitsalchemical sense.Sedley2005,inacomparativestudyofsublimityandskepticisminMontaigneandMilton,offers chapterson “Comus andtheInventionofMilton’sGrandStyle” (82–107)and “ParadiseLost andHow (Not)toBeSublime” (108–33),butbotharepredominantlyconcernedwithMiltonicskepticismrather thansublimity;onecouldalsoarguethattheaporeticqualityofthesublime,whichunderpinsSedley’ s thematicconnectionofsublimityandskepticism,ispartofthedistinctivelyaestheticconceptofthe sublimewhichdidnotdevelopuntilafterMilton,butthatwouldrequiremorespacethanisavailable here.Cheney2009bconsidersMilton’ssublimityinrelationtoMarloweandrepublicanism;seealso Cheney2018bpassim.Machacek2011:121–35arguesgenerallyforthepotentialimpactofLonginus onMilton,inparticularbydrawingattentiontoLonginus’ Homericexempla.Norbrook2013provides animportant firststeptowardanextra-LonginianunderstandingoftheMiltonicsublimebyconsidering ParadiseLost inrelationtotheLucretiansublime.PromptedbyPorter2016andothers,Shaw 2017(thesecondeditionofShaw2006)includesachapteron “EarlyModernSublimity” (41–66),with ashortsectiononMilton(45–8).Mostrecently,Lehtonen2019seesthesublimityofMilton’sSatanasa responsetoaTassoanmodelofheroiccharisma.

quo.MorethanacomparativestudyofMiltonandLonginus thoughthatlies withinitspurview thisrequiresahistoricalexpositionofideasofthesublime, Longinianandotherwise,astheseexistedinMilton ’slifetime,whichcanthen informahistoricallygroundedexegesisofthesublimeinMilton.

ThePhilologyoftheSublime

The firstchapterofthisstudywillconsiderthehistoryofvariousconceptionsof thesublimefromantiquitytotheRenaissance.Buthowisthesublimetobe defined?PatrickCheney,inthemostrecentofhisseveralstudiesofthesublimein EnglishRenaissanceliterature,characterizesitasnothingmorethan “literary greatness.”¹⁵ Yetthisdefinitionseemstomeinadequate,beingatoncetoospecific andtoogeneral,forthesublimeisnotlimitedtoliterature,norisitquitesovague asaqualityof “greatness. ” Isubmitthatthequestionofdefinitioninsteadneedsto beapproachedphilologically.Givenitspost-classicalimportance,Ishallbeginby treatingtherootoftheEnglishword sublime Latin sublimis anditsderivatives beforeturningtothemoreexpansiveGreekvocabularyofLonginusandits implicationsforthephilologyofthesublime.

Asmyownusagesuggests,themostobviouswordsfortheconceptofthe sublimearetheLatin sublimis anditsderivativesinEnglishandotherlanguages. TheRomangrammarianFestusglossestheLatinwordas “Sublimemeanslifted onhigh” (Sublimemestinaltitudinemelatum,Festus Gloss. Lat.306.17–18)and speculatesthatitderivesfrom “ahigherthreshold,becauseitisaboveus” (limine superiore,quiasupranosest,Festus Gloss. Lat.306.26–27Lindsay).AlfredErnout andAntoineMeilletdismissthisasa calembour suchasancientetymologistswere wonttomake.¹⁶ The firstelementof sublimis mostlikelydoesnotderivefrom super (“over,above”)butinsteadfrom sub,meaning “under,beneath,” andhence also “movementfrombelow,reachingupward.”¹⁷ Theoriginofthesecond element(-lim-)islessclear.Festus’ limen couldbecorrect,giving sub+limen (“uptothethreshold”).ButtheetymologicaldictionariesofErnout-Meilletand MichieldeVaanbothagreeinpreferring limus (“oblique,transverse”),fromthe Proto-Italicroot*limo-:thecompound*sub-lim-i wouldthussignify “thatwhich ascendsinanobliqueline,thatwhichrisesonanincline” or “transversefrom belowupward.”¹⁸

¹⁵ SeeCheney2018bpassim,esp.36: “Literarygreatness ismyworkingdefinitionofthesublime.”

¹⁶ ErnoutandMeillet2001s.v.sublimis.

¹⁷ Ibid.;deVaan2008s.v.sub,su(b)snotes: “Themeaning ‘movementupwards’ canbeseene.g.in suspicio, sublevo, surgo, sublatus ”

¹⁸ ErnoutandMeillet2001s.v.sublimis;DeVaan2008s.v.limus2.

TheLatinwordis firstattestedinearlyRomandramaofthelatethirdandearly secondcenturies .¹⁹ ItsearliestappearanceisinafragmentfromNaevius’ tragedy Lycurgus:thetextiscorrupt,butitseemstorepresentthetitular character’sinstructionto “lure” (inlicite )andtrapthemaenads,herecalled “two-footedbirds” (bipedesvolucres)or “flyingbipeds” (bipedesvolantes), “ on high” (sublime ,Naev. Trag .18Schauer).Theuseof sublimis inrelationto flightin general,particularlyinthephrase sublimevolans (“flyinghigh”),isfoundinsuch authorsasAccius(Acc. Trag.390,576Ribbeck),Lucretius(Lucr.2.206,6.97),and Vergil(Verg. Aen.10.664),buthereinNaeviustheinhibited flightofthemaenads onhigh(sublime)mayalsorefertothemysticalnotionofthedyingsoulasa flutteringbird.²⁰ MorelegiblearetheseveralplacesinthetragediesofEnniusin whichtheword sublimis isusedforvariousphenomenaabovetheearth,meteorological,astronomical,anddivine:inoneinstanceheappliesittoclouds(sublimas subices [= nubes],Enn. Trag.3–4Jocelyn;cf.Lucr.4.135,6.97),whilethephrase sublimeiter (“sublimejourney”)isusedbothfortheheavenlypathofthehorsesof HeliosandforthemovementoftheconstellationBoötes(Enn. Trag.169,190 Jocelyn).ElsewhereEnniususes sublimis todescribethesun “onhigh” (sublime), identifiedasJupiter(quemvocantomnesIovem ,Enn. Trag.301Jocelyn),²¹and providestheearliestattestationoftheverb sublimare (“toelevate,raiseup”)when hesaysthatthesun “liftsupitsglowingtorchinthesky” (candentemincaelo sublimatfacem,Enn. Trag.243Jocelyn).H.D.Jocelynnotesthat sublimis, “aword ofsomedignity,” appears “notatallincomedyexceptinthesetphrases sublimem rapere (arripere )and sublimemferre (auferre).”²²Itisnotdifficulttoseehowthe upwardmovementdenotedbythe firstelementof sublimis couldhaveledtothe wordbeingappliedtothegeneralactofliftingsomeoneofftheirfeet,asisthecase inRomancomedy,butlaterusageof sublimemrapere forabductionbythegodsor assumptionintotheheavenssuggeststhepossibilitythattheoriginalsenseofthe phrasemayhavebeenmorenuminousthanhumorous,aslaterinthe Aeneid (Verg. Aen.1.259,5.255).²³RudolfEhwaldin1892evenproposedthatLivy’ s descriptionoftheapotheosisofRomulusasa sublimeraptum (Liv. AbUrb. Cond. 1.16.2)wastakenfromEnnius’ epic Annales,ahypothesisthathasbeenaccepted byanumberofscholarssince.²⁴

¹⁹ Themostextensiveoverviewoftheearlyuseof sublimis remainsHaffter1935,reprintedin Lefèvre1973:110–21.

²⁰ SeeSeaford2009:410–11.

²¹PossiblyinspiredbyEur.fr.941Snell ὁ

,inwhichcaseEnnius’ sublime wouldbetranslating ὑψοῦ;seethediscussioninJocelyn1969:423–4.

²²Jocelyn1969:169.SeePlaut. Asin.868; Men.992,995,1002,1052; Mil.1394;andTer. Ad.316, An.861.

²³Theword rapere ingeneralisstronglyassociatedwithdivineabduction,liketherapeof Persephone,asinOvid;seeHinds1987:151n.20.

²⁴ Ehwald1892:12.Cf.Enn. Ann.54–55,105–11SkutschandseeNorden1957onVerg. Aen 6.719f.,Meister1925:35;Haffter1935:252;Hardie2009:200.

Theseearlyattestationssuggestsomeofthewaysthat sublimis wouldcontinue tobeusedthroughoutthehistoryofRomanliterature:itcouldsimplymean “high,” andhencesomethingasmundaneasliftingsomeoneup(sublimemferre); itcoulddescribeanythingintheairorsky,includingclouds,stars,meteors,orthe movementofcelestialbodiesandheavenly figuresabove(sublimeiter);andit couldbeusedinrelationto flight(sublimevolans),especiallyformodesofdivine transportsuchasabductionorapotheosis(sublimeraptum).Itisonlyinthe first century thatwe findevidenceofthesemanticdevelopmentof sublimis intothe sense “great,distinguished,eminent, ” asappliedforexampletopersons ofwhich the firstinstanceisinVarro(Varr. Rust.2.4.9) andthesense “grand,noble, lofty” asaliterary-criticalterm, firstfoundinOvid(Ov. Am.1.15.23,3.1.39–40). Columellainthe firstcentury providestheearliestwitnessforthesubstantive sublimitas (“sublimity”),hereusedsimplywithregardtothephysicalheightofa building(Colum. DeReRust.8.3.3).

Inpost-classicalLatin sublimis, sublimare ,and sublimitas spawnedanumberof newwords.Thedeverbalnoun sublimatio (“elevation ”)is firstattestedinthelate antiqueauthorAvitusofViennewithasenseoftheologicaldeliverance(Alc.Avit. ContraEutych Haer .20.6Peiper),butlaterbecomesthestandardLatintermfor theprocessofalchemicalsublimation,socalledbecausetheextractrisestothetop ofthevessel.Renaissanceauthorsproducedsuchcoinagesas sublimamentum (“cloudiness”), sublimaticus (“distilled ”), sublimipeta (“onewhoaspiresto heights”),and sublimivagus (“strivingtoheights”).²⁵ DerivativesfromtheLatin begintoappearinvernacularlanguagesfromthefourteenthcenturyonward. PerhapstheearliestinstanceisintheoftenhighlyLatinateItalianofDante’ s Commedia,inwhichtheangelscirclingaroundGodstrive “tomakethemselves likethepoint[i.e.God]asmuchastheyareable,/andareableasmuchtheyare sublime[soblimi]intheirvision” (persomigliarsialpuntoquantoponno,/ e possonquantoavedersonsoblimi , Paradiso 28.101–102).French sublime and Occitan sublimatiu are firstattestedaroundthesametime,infourteenth-century translationsofmedievalLatinencyclopedicworks.²⁶

InEnglish, sublime is firstfoundasanalchemicalterm,afterLatin sublimatio, referringtotheprocessofsublimation:in TheCanterburyTales Chaucerhasthe Canon’sYeomandescribe “hisscience” withreferencetotheprocessof “sublymyng, ” theproduct “sublymedmercurie,” andthevesselsinwhichsublimation takesplace, “sublymatories.”²⁷ Beforetheendofthe fifteenthcenturythere appearstheverb sublime inthesense “toelevate,exalt,orpurify” aswellasthe noun sublimity,whichlikeLatin sublimitas isnotusedinrelationtoalchemybut

²⁵ SeeRamminger2020s.v.sublimamentum,sublimaticus,sublimipeta,sublimivagus.

²⁶ SeeGodefroy1902s.v.sublimeandRaynouard1843s.v.sublimatiu.

²⁷ Chaucer2008:VIIIG721,770,774,793.Cf.thequotationoftheroughlycontemporaryEnglish translationofthe ChirurgiaMagna ofLanfrancofMilanin OED s.v.sublime, v.I.1.

rathersignifiesnobility,greatness,height,asin “hevenlysublimitee.”²⁸ The adjective sublime is firstattestedinthe1567EnglishpsalterofMatthewParker, ArchbishopofCanterbury,whoinhisverseproem “TotheReader” recommends theelevatingpowerofmusicbecause “flatverseitreysthsublime.”²⁹ Milton’susageof sublime islargelyconsistentwithearlymodernEnglish practicemoregenerally,butwiththealchemicalsensepredominating.³⁰ From thisonemightsurmisethatMiltonhadnospecialconceptionofthesublimeatall, atleastinthesensewithwhichIamconcerned.Butthesignificanceofthisone word, sublime,shouldnotbeoverstated.Afterall,itisawordthatthegreat ancientauthorityonthesubject,Longinus,asawriterofGreek,doesnotuseatall. Longinusopenshistreatisebynotinghisdisappointmentwithaworkthat CaeciliusofCalactewrote “aboutthesublime” (perihupsous,Long. Subl.1.1)and respondingtohisaddressee’sappealtowrite “somethingaboutthesublime” (tiperihupsous,Long. Subl.1.2)himself.Itwaspresumablyfromthesestatements thattheworkwasgiventhetitle Perihupsous,iftheauthordidnotdeviseit himself.Thenoun hupsos issimplythemostbasicwordfor “height” intheGreek language,derivedfrom hupsi (“up,above”).³¹Longinususesthisandrelated wordslike hupsēlos (“high,” Long. Subl.40.2), hupsēgoria (“loftyexpression,” Long. Subl.8.1),and hupsēlophanēs (“lofty-seeming,” Long. Subl.24.1)throughouthistreatise.But hupsos-wordsarehardlytheonlytermsinwhichLonginus discusseshissubject:asJamesPorterhasnoted,thetext’ s “indifferencetoterminologycanbebreathtaking andabanetomodernphilology.”³²If,asPorterhas claimed,theobsoletehistoriographyofthesublimedependsinpartona “ narrow Wortphilologie” whichtakesforgrantedthatonlythewords hupsos, sublimitas, andthelikecansignifythesublime,attentiontotherangeandvarietyof Longinus’ vocabularyshouldserveasacorrective.³³

Longinusonceevenappearstotreat bathos (“depth”),seeminglythesemantic oppositeof hupsos,asavirtualsynonym,whenhewonders “ifthereissome technique[technē]ofloftiness[hupsous]ordepth[bathous]” (εἰἔστιν ὕψουςτις ἢ βάθουςτέχνη,Long. Subl.2.1).Isay “ appears ” becausetheByzantinearchetypeof themanuscripttraditionhasthereading bathous,³⁴ althoughanumberofscholars havethoughtthatthetextrequiredemendation:thebestconjectureis pathous (“passion,emotion”), firstintuitedbyGiovannidiNiccolòdaFalganoinhis Italiantranslationdedicatedin1575.³⁵ Thisreadinghasbeenadoptedbymany editorssince,includingCarloMazzucchi,whoproposesinhis1992editionthat

²⁸ See OED s.v.sublime, v.II.5.a.(a)ands.v.sublimity, n ²⁹ Parker1567:sig.A2r.See OED s.v.sublime, adj.and n.A.1.a.(a).³⁰ Feinstein1998.

³¹SeeBeekes2010s.v. ὕψι.³²Porter2016:182.

³³Ibid.49;see7ff.Ibid.180–2providesacomprehensivelistofLonginiantermsforthesublime whichformsthebasisofmydiscussionhere.

³⁴ BnFCodexParisinusGraecus2036,fol.179v.

³⁵ BibliotecaNazionaleCentralediFirenze,MSMagl.VI.33,fol.5v(affetto);seetheapp.crit.in Mazzucchi1992adloc.OnGiovannidaFalgano’stranslationseeCardillo2010.

thepairingofheightsanddepthsinbiblicalimageryprompted “theerrorofthe Byzantinescribe.”³⁶ Thepairingofheightsanddepths,however,isasclassicalasit isbiblical,andtheimageryofsublimedepthsevenappearselsewhereinthe Peri hupsous.³⁷ Moreover,theemendation pathous isproblematicinitself,asLonginus latercriticizesCaeciliusforimplyingthatsublimityandpassionareidentical (Long. Subl.8.2).Tonamehissubjectbothloftinessandprofunditywouldhave beennocontradictionforLonginus,whohadamultitudeofwordsforthesublime athisdisposal.

Longinusspeaksofthesublimeintermsofsize,greatness,ormagnitude,many ofwhichareformedfromtheroot mega-,including megas (“great,large”), megethos (“greatness,size”), megalophuēs (“great-natured ”), megalophrosunē (“greatnessofmind”).Hespeaksofthesublimeas ogkos (“mass,bulk,swelling”) andas hadrotēs,whichmeans “strength,vigor,ripeness,thickness,abundance,” fromtheadverb hadēn (“toone’ s fill,tosatiety,unceasingly”).³⁸ Heuseswords withtheprefix huper-,whichhavethesenseofgoingover,above,andbeyond: theseinclude,amongothers, huperphuēs,literally “over-natured” or “ overgrown, ” usedtomean “extraordinary,strange,monstrous;” huperbolē (“ excess ”),literally “overshooting;” and tohuperairon,fromtheverb huperairein (“togobeyond,to raiseabove ”),whichforLonginussignifiessomethingliketranscendence: “One seeksinstatuesthelikenessofahuman,butinliterature,asIwassaying,the transcendence[tohuperairon]ofhumanity” (

,Long. Subl. 36.3).Wordswiththepre fix ek-(“out”)haveasenseofdisplacement,suchas ekphulos,literallyoutsideof(ek)thetribe(phulē),hence “strange,alien,horrible;” ekstasis (“ecstasy”),literallyoutof(ek)place(stasis),displacement;and ekplēxis, from ek and plēxis (“blow,strike”) glossedbyD.A.Russellinhiscommentary onLonginusas “surpriseorfearwhich ‘knocksyouout.’”³⁹ Healsousestheword deinos,aswellasderivativeslike deinotēs,whichinrhetoricalwritingsoftenhas thesense “forceful” or “intense” butwhosebasicmeaning,fromtheProto-IndoEuropeanroot*duei-no-,is “fearful,dreaded,terrible.”⁴⁰ Thefearfulaspectofthe sublimeisnotlimitedto ekplēxis and deinos butfoundalsoinLonginus’ useof wordswiththeroot phobos or “fear” (e.g.,Long. Subl.10.6).Longinusalsospeaks ofthesublimeintermsofdivineinspirationandpossession: pneuma (“inspiration,”) enthousiasmos (“divinepossession ”), mania (“madness ”), Korubantiasmos (“Corybanticfrenzy”), Bakcheia (“Bacchicpossession”), Phoibolēptos (“seizedby Apollo”).Thesublimeis semnotēs (“solemnity,majesty”)aswellas sphodrotēs

³⁶ Mazzucchi1992:135.

³⁷ SeeGrube1957:360–2,Capizzi1983,andPorter2016:530–1,withreferencetoLong. Subl. 9.6,35.4.

³⁸ SeeBeekes2010s.v. ἅδην

³⁹ Russell1964:122.OnthedislocatingpowerofLonginianrhetoricseeToo1998:187–217.

⁴⁰ SeeBeekes2010s.v. δεινός

(“violence,vehemence”).Inoneplacethesublimeis “ambitiousness[to... hadrepēbolon]inideas” (τὸ περὶ τὰςνοήσεις ἁ

,Long. Subl.8.1),the dislegomenon hadrepēbolon literallymeaning “aimingatvigor[hadrotēs];”⁴¹in anotheritissimply kallos (“beauty”).

TheextensivevocabularyofLonginusnotonlyshowstheimpoverishmentof anyhistoricalstudyofthesublimewhichdoesnottakeintoaccountanyterms beyond sublimis or hupsos butalsosuggeststhewidesemantic fieldofthesublime: loftiness,elevation,andexaltation;depthandprofundity;vastness;magnitude; massorbulk;fear,terror,anddread;divineinspirationandpossession;excess, goingbeyond,exceedinglimits,transcendence;vehemence,violence,andforce; flight,transport,rapture;shock,displacement,andecstasy. ⁴²Therearethereforea numberofwordsthatcouldbeusedtosignifythesublime,whetherinclassicalor vernacularlanguages.

InLatin,forinstance,someothertermsbesides sublimitas areindicatedbythe differentwaysthatthetitleofLonginus’ treatisewastranslatedintheearly modernperiod.Mostfollowthepatternofthe editioprinceps,whichhasthe title Degrandisivesublimiorationisgenere,identifyingthesubjectasaformof speaking(genusorationis/genusdicendi)thatisgrand(grandis)orsublime(sublimis): sublimis translatestheliteralsenseofheightin hupsos,while grandis connectsthisqualitywiththegrandstyle(genusgrande)inrhetoricandwitha moregeneralkindofgrandeur(granditas).⁴³Themanuscriptoftheearliestextant Latintranslation,ontheotherhand,isentitled Dealtitudineetgranditate orationis,likewisenamingthesubjectas “grandeurofspeech ” (granditateorationis)butheretranslating hupsos with altitudo awordwhichcanequallysignify heightordepth,andthusperfectlyencapsulatestheLonginianconjunctionof hupsos and bathos. ⁴⁴ Inasectionofhis1630rhetoricaltreatisetreating “the variousnamesofthesublimestyle” (variissublimisstylinominibus)theDutch classicalscholarGerardusVossiusillustratessomeofthepossiblelexicalbreadth involvedwhenherecordsthealternativeadjectives magnificus (“magnificent”), magniloquus (“magniloquent”), altiloquus (“high-speaking”), magnus (“great”), altus (“high”), summus (“ supreme ”), plenus (“full”), uber (“rich”), gravis (“ grave ”), copiosus (“copious”), ornatus (“ornamented”).⁴⁵ SamuelHartlib,towhomMilton addressedhisessay OfEducation,offers sublimitas asasynonymof magnitudo (“greatness,magnitude”),theLatincognateoftheLonginianGreekterm megethos,togetherwith infinitas (“boundlessness,infinity”), amplitudo (“extent, abundance”),and sufficientia (“suf ficiency,plenitude”).⁴⁶

⁴¹Theonlyotherappearanceof hadrepēbolon inallofextantGreekliteratureisatVett.Val.43.2.

⁴²Cf.therespectivelistsofHardie2009:81ff.andPorter2016:51–3.

⁴³Robortello1554;Manutius1555;Portus1569/70;dePetra1612;Langbaine1636,1638,1650; Manolessi1644.

⁴⁴ BAVMSVat.Lat.3441. ⁴⁵ Vossius1630:II432. ⁴⁶ HP38/7/11A.

ManymorewordsinGreekandLatincouldbeadded,nottomentionthe vernaculars,anexhaustivelistofwhichwoulditselfwarrantaLonginianlabel suchas mania or huperbolē.Butitsufficestohaveintimatedthegreatvarietyof termsthatcanbeusedtosignifythesublime,andhavingconcludedthisbrief philologicalinvestigationIamnowpreparedtoofferaworkingdefinitionofthe sublime,imperfectthoughitcertainlyis,asIthinkMiltonandhiscontemporaries mighthaveunderstoodit.Itisthis:thesublimeisarhetoric,andathematics,of loftiness,grandeur,power,andscale,whicheffectsravishment,astonishment, awe,andoftenterror.Miltonhimselfmayneverhaveformulatedsuchadefinition ofthesublime,buttheconfluenceoftheseelementsinhiswritingsandthought,as shallbecomeapparent,suggeststhathewouldhaverecognizedit.

ThePlanofThisStudy

Boileau ’spopularFrenchtranslationofLonginuswaspublishedinJuly1674, withindaysoftheappearanceofthesecondeditionof ParadiseLost andlessthan halfayearbeforeMilton’sdeath, ⁴⁷ anditwasoverthefollowingdecades,partly undertheinfluenceofBoileau ’sLonginus,thatMilton ’ssublimitybecame entrenchedasacriticalcommonplaceamongwritersincludingJohnDryden, JohnDennis,andJosephAddison.⁴⁸ But,crucially,itisnotonlyafterBoileau thatsuchcommentsweremade.Asearlyas1669EdwardPhillips,Milton’ s nephewandformerpupil,commends ParadiseLost forits “sublimityofargument” (sublimitatemArgumenti),its “majestyofstyle” (MajestatemStyli),andits “sublimityofinvention ” (sublimitatemInventionis).⁴⁹ Intheirdedicatorypoems includedinthesecondeditionof ParadiseLost,bothSamuelBarrowandAndrew MarvellpraiseMiltonasapoetofthesublime:BarrowinhisLatinverseslauds Milton’ s grandiacarmina (“sublimecantos”),whileMarvellmorepointedlyuses theEnglishword sublime intheline “ThyversecreatedlikethyThemesublime.”⁵⁰ TheseearlyresponsesidentifyinMiltonsomeoftheaspectsofthepre-aesthetic sublimethatwillbeconsideredinthisstudy.

Chapter1outlinesthediachronicdevelopmentofvariousnotionsofthe sublimeinEuropeanthoughtfromclassicalantiquitytotheearlyseventeenth century.Ibeginwithanoverviewofthe Perihupsous anditscontextinGreek

⁴⁷ SeeBrody1958,Cronk2002,andDoran2015:97–123.

⁴⁸ Seeesp.Moore1990.OntheinfluenceofBoileau’sLonginusseeinteraliaClark1925:361–79; Huntley1947;Gelber2002:161–5;andDelehanty2007.Boileau’sLonginuswastranslatedfromFrench intoEnglishatleasttwice(Pulteney1680;[Anon.]1698).Additionally,a1679advertisementrecords theexistenceofanotherwiseunknownvolumeprintedbyJacobTonsonunderthetitle “ATreatiseof Sublimity:Translatedoutof Longin,by H.Watson,ofthe InnerTemple,Gent.” (Hall1679:sig.Ttt4r); theuseoftheFrenchform Longin andthedatebothsuggestthatthistoowastranslatedfromBoileau.

⁴⁹ Phillips1669:399.SeeMcDowell2019andChapter2.

⁵⁰ Lewalski2007:5,Marvell1971:I138.SeevonMaltzahn2001:166ff.andMiner2004:35–40.Lieb 1985recognizesBarrow’sversesasconstitutinga “sublimecommentary” on PL.OnBarrowseealso vonMaltzahn1995.

rhetoricaltheory,whichisfollowedbyanexaminationofthereceptionof LonginusandtheLonginiansublimeinearlymodernEurope.Thisprovidesthe necessarybackgroundtotherhetoricalspeciesofsublimity,oracertainnotionof loftystyle,asitwouldhavebeenunderstoodbyMiltonandhiscontemporaries. Ithenprovidesketchesoftheothertwospeciesofthesublime,thephysicaland thetheological.Thesublimeinnatural-philosophicaldiscourseistracedfrom classicalauthorssuchasLucretiustotheseventeenth-centuryJesuitpolymath AthanasiusKircher,whileatraditionofthesublimeintheologicaldiscourseis showntoextendfrombiblicalcommentatorssuchasPhiloofAlexandriato theologiansoftheReformation.Thehistoricalexpositionfurnishedhereprepares thegroundforthesubsequentchaptersonMilton,eachofwhichtakesasitsfocus oneofthethreespeciesofthesublime.

Chapter2arguesfortheimportanceofaconceptionofsublimerhetoricin Milton’spoetryandprose.I firstspeculateonwhenandinwhicheditionMilton mighthave firstencounteredLonginus.Milton’seducationinrhetoricmore broadlyisalsoconsidered,asistheevidencefromhistract OfEducation and fromthewritingsofEdwardPhillipsthatMiltonhimselfmayhavetaughtthe Peri hupsous tohisnephews.Ithenshow,withreferencetoIsaacCasaubonandHugo Grotius,thatMiltonpossessedasenseofbiblicalsublimityofstylewhichdeeply informedhissoaringpropheticpoetry.Thepotentiallydangerousassociationof suchsublimitywithenthusiasmorreligiousfanaticism,astouchedonbyJohn SpencerandespeciallyMericCasaubon,isalsoexplored.FinallyIturntothe politicalimportofLonginusforMilton.IdiscusswhatDavidNorbrookhascalled the “distinctivelyrepublicanaccent” ofthesublimeintheperiodoftheEnglish CivilWars, ⁵¹agreeingwiththisgeneralcharacterizationbutwiththequali fication thatsometimes,asforJohnAubrey,Longinian hupsos didnotalwaysalignwith revolutionarypolitics.ThechapterconcludeswithananalysisofSatanin Paradise Lost asarepublicanoratorwhoseenslavementbyhispassions,asLonginuswarns, preventshimfromachievingtruesublimity.

Chapter3contendsthatin ParadiseLost inparticularMiltonmakesuseofa physicsofsublimemagnitudesinhisattempttorenderadequatelytheunimaginablesizesandspacesofthepoem,inspiredbothbyclassicalauthorsandbythe technologiesanddiscoveriesofthenewscience.IbeginwithafocusonMount Etna,anobjectofphysicalsublimityforbothLonginusandAthanasiusKircher,as itappearsinMilton ’searlywork InQuintumNovembis andespeciallyin Paradise Lost.IthenconsiderwhatIcallMilton ’ s “hyperbolicsimiles” in ParadiseLost, whichIpositcanbeunderstoodlogicallyasquantitativecomparisonsdeveloped inaprocessofRamist inventio .ThesesimilesareshowntomagnifySatanandhis ilktosublimedimensions,thoughnotunproblematically,andIproposethatthe simileofthediminishingdemonsattheendofBook1inparticularmaybearthe

⁵¹Norbrook1999:137.

influenceofapassageofLonginusregardingpygmyslaves.Thelastpartofthis chapterisconcernedwiththenewastronomyandthevastnessofspace.Looking toearlymodernscientistssuchasGalileoandJohnWilkins,IexamineMilton’ s attemptstodepicttheimpossiblyhugesublimitiesoftheuniverse indeedthe multiverse inthepoem,rangingfromtheseeminglyincalculablespanofthe finitecreateduniversetotheinfiniteexpanseofChaos.

Chapter4assertsthatanotionofthesublimealsopervadedMilton ’stheologicalthought.I firstattendto AMaskePresentedatLudlowCastle,1634,which SirHenryWottondescribesintermsofrapture,asaworkinwhichvirginpurity sosublimesthesoulthatthethreatofGod’swrathisinvokedagainstitsenemies. Thisspeakstoanotionofdivinesublimitywhich,astheReformedtheologian DanielChamierwrites,inheresnotinrhetoricalstylebutinholymatter.Next Iconsiderthewarinheavenin ParadiseLost,arguingthatthisepisodeshouldnot beinterpretedwhollyorpredominantlyasfarceorcomedybutratherasasublime theomachywhichcloselyfollowstheHomericpatternpraisedbyLonginus.After thisIturntothecontentioustopicofMilton’sGod.Brieflyconsideringtheviews ofPseudo-DionysiustheAreopagiteandJohnColetontherepresentationofthe divine,Iendeavortodemonstratethatin ParadiseLost andinthetheological treatise DeDoctrinaChristiana Miltonportraysadeitywhoseobscurityandwrath suggesttheultimatelyincomprehensiblesublimityofthedivine.Milton ’ssublime GodistobemetwiththerightChristianpracticeof timorDei (“fearofGod”), whichstandsinoppositionto timoridololatricus (“idolatrousfear”):the finalpart ofthechapterconsidersthisneglectedtheologicalnotion,whichMiltoninherited fromtheReformedtheologiansAmandusPolanusandJohannesWollebius, in DeDoctrina, ParadiseLost,and SamsonAgonistes . Theconclusionofthisstudybrieflyreviewsitscontributions.Twoappendices follow,whichofferadditionalevidenceforthereceptionofLonginusinseventeenthcenturyEngland.The firstisabibliographicalstudyofcopiesofLonginus thatIhavebeenabletoplaceinEnglishprivatelibrariesbefore1674.Thesecond providesaneditionoftheLansdowneLonginus,apreviouslyunknown seventeenth-centuryEnglishtranslationofthe Perihupsous thatIdiscoveredin theLansdownecollectionattheBritishLibrary.⁵²

Milton’ssublimity,asIhopetoshow,isno “fictionofeighteenth-century criticism.”⁵³Onthecontrary,notionsofthesublimetouchonalmosteveryaspect ofMilton’scareer,fromrhetorictopolitics,fromsciencetotheology.Making contributionstoliteraryscholarship,classicalreceptionstudies,andthehistoryof ideas,thisstudyseekstoreturnthesublimetoitsproperplaceattheforefrontof Miltoncriticism,toreevaluatethediffusionofLonginiantextsandnotionsin earlymodernEurope,andtorecordacrucialmissingchapterinthehistoryof thesublime.

⁵²SeeVozar2020. ⁵³InthewordsofMoore1990:2.

TheSublimefromAntiquity totheRenaissance

Theaimofthischapteristoofferagenealogyofthesublimefromantiquitytothe Renaissance.Itakegenealogyinthissensetosignifyakindofhistoricalinquiry intotheevolutionanddevelopmentofsomeconceptorinstitutionwhichemphasizesitscontingency.¹Thischapter,accordingly,isconcernedwithtracingthe developmentofvarioushistoricalnotionsofthesublimefromtheirancient originstotheseventeenthcentury.It firstconsidersLonginusandthenotionof rhetoricalsublimityinGreco-Romanantiquity,thentreatsthereceptionof LonginusintheRenaissance.AfterthisIturntotwoothermodesofsublimity, adaptedfromJamesPorter’sconceptsofthematerialandtheimmaterialsublime: physicalsublimity,orthesublimeasitrelatestonatureandmatter,andtheologicalsublimity,orthesublimeasitrelatestodivinity.²Thesethreelineagesofthe sublime therhetorical,thephysical,andthetheological providethetemplate forthesubsequentthreechapters,aseachtypeofsublimityisconsideredin relationtoMilton.Thistripartitedivisionmustbeunderstoodasamereheuristic deviceororganizationalprinciple:thesublimecaneasilytransgresssuchartificial limitations.Nevertheless,thistripartitedivisionhastheadvantageofallowingthe rhetoricalideaofthesublimetobetreatedwithdueattentiononitsown,while alsogivingspacetoconsiderthemoreexpansivereachofthesublimeintoboth thephysicalornaturalrealmandthemetaphysicalortheologicalone.Ibegin, then,withLonginus.

LonginusandGreekRhetoricalTheory

Asnotedearlier,Longinusdoesnotclaimtohavediscoveredsomethingnew,but ratherframeshisworkasaresponsetoa “littletreatise ” (sungrammation)that CaeciliusofCalactewrote “aboutsublimity” (perihupsous,Long. Subl.1.1),which

¹Nietzsche2006,withhisgenealogyofmorality,wasthe firsttousethewordinthissense;onhis conceptionofgenealogyseeGeuss1994.Foucault1995genealogizedtheinstitutionoftheprison;see Foucault1977forhisownthoughtsongenealogy.Bevir2008:266identifies “nominalism,contingency, andcontestability” asfeaturesofgenealogy;foritsfunctionasaformofcritiqueseeGeuss2002.

²ForwhatIcall “physical” and “theological” sublimitycf.theconceptsof “material” and “immaterial” sublimityinPorter2016.

Milton,Longinus,andtheSublimeintheSeventeenthCentury.ThomasMatthewVozar,OxfordUniversityPress. ©ThomasMatthewVozar2023.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198875949.003.0002

14

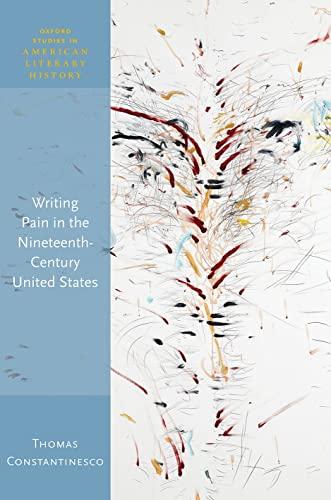

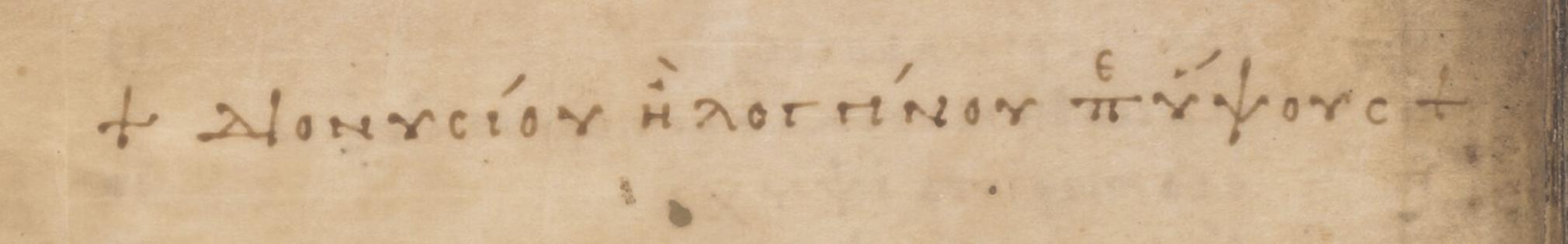

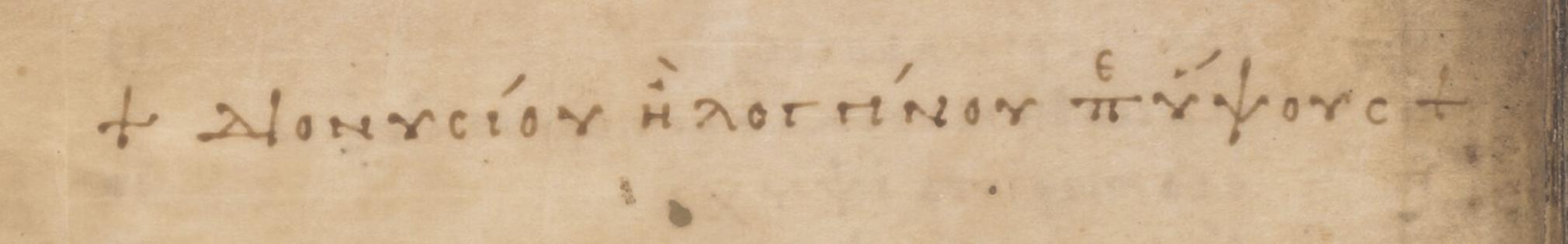

LonginusandhisRomanaddressee,acertainPostumiusFlorusTerentianus,³ founddefective.Buthowthe Perihupsous shouldbesituatedwithinthislarger conversationaboutthesublimeinantiquityisnotstraightforward.Neither Caecilius’ noranyotherancientworkdevotedtothesublimesurvives,andthe dateandauthorshipofthe Perihupsous aremattersofcontinuingspeculationand debate.Internalreferencestoauthorsofthe firstcentury restrictitsearliest possibledatetotheAugustanperiod.Intheearliestwitnessofthetext,a Constantinopolitanmanuscriptinahanddatedtothesecondhalfofthetenth century nowattheBibliothèquenationaledeFranceinParis,theauthoris listedinthetableofcontentsas “DionysiusorLonginus” (Dionusion ē Longinon ), whiletheheadingatthebeginningofthe Perihupsous itselfattributesitto a “DionysiusLonginus” (DionusiouLonginou ).⁴ Thescribe,orhispredecessor, seemstohavebeensuggestingtheAugustanrhetoricianandhistorianDionysius ofHalicarnassusandthethird-century philosopherCassiusLonginusas possibleauthors,orsuggestingoneinadditiontothenamethathefoundinhis source,onlytoconflatethetwolater.Alternatively,itispossiblethatDionysius Longinuswastheformthatwastransmitted,andthatthescribelateraddedtheeta (ē)asanafterthoughttoindicatesomemeasureofdoubt,asappearspossiblefrom thespacingoftheline(Figure1).⁵ Inanycase,themanuscript ’sDionysius Longinus,identifiedwithCassiusLonginus(Dionysiususuallybeinginterpreted asthephilosopher’ s praenomen),becamethenameunderwhichthetextcirculatedintheRenaissance.Occasionalattemptshavebeenmadetosalvagethe traditionalattributionofthetexttoCassiusLonginus,butmostscholarstoday datetheworkearlier,tothelate firstcentury ortothe firstcentury ,making himacontemporaryornearcontemporaryofCaecilius.⁶

Figure1 DetailofaByzantinemanuscriptofLonginus,ParisinusGraecus2036, fol.1v,courtesyoftheBibliothèquenationaledeFrance.

³OntheemendationofthenameseeMazzucchi1992andHalliwell2022atLong. Subl.1.1. ⁴ BnFCodexParisinusGraecus2036,fol.1v,fol.178v. ⁵ Mazzucchi1992:xxx.

⁶ ThetraditionalattributiontoCassiusLonginushasbeendefendedmostnotablybyHeath1999; seealsoHeath2012a:15–16and2012b:169–79.Grube1965 findsa “first-centurydate[...] improbable” (342).Amongothers,Goold1961:168–78andMazzuchi1992:xxxi–xxxivargueforan Augustandate,tentativelysupportedbydeJonge2012and2014;Russell1990writesthat “convincing argumentsagainstanAugustandatearedifficultto find” (309).CrossettandArieti1975,ontheother hand,positaNeroniandate.SeealsothediscussioninMartano1984:365–70.Seemostrecently Halliwell2022:x–xix,whonotesthatproblemsofdatingderiveinpartfromthetext’spursuitofa “timeless” Greekideal.

Inestablishingthecontextofthe Perihupsous inancientcriticism,Caecilius wouldseemtobeacrucialauthor,buttheverylittlethatisknownofhisworkon thesublimeisfromLonginushimself.⁷ Caecilius,Longinusobjects,thoughhe providedmanyexamplesofthesublime,omitted “bywhatmeanswemightbe abletoadvanceournaturestosomeincreaseofgreatness[megethous ]” (δι᾿ὅτου

Long. Subl.1.1).Later,intreatingtherhetoricalviceof “frigidity” (psuchrotēs) inthehistorianTimaeus,⁸ Longinussays: “Ishallcitejustoneortwopassagesof theman,sinceCaeciliusseizeduponmostofthembeforeme” (

,Long. Subl.4.2).Elsewhere LonginusclaimsthatCaeciliusmisunderstoodtherelationshipbetweensublimity (hupsos)andpassion(pathos):ifCaeciliusunderstoodpassionandsublimityas identical,heerred,forpassionneednotbelofty,andsublimityneednotbe passionate;if,ontheotherhand,Caeciliusdidnotconsiderpassionsomething thatcontributestothesublime,hewasalsomistaken,since “thereisnothingso magniloquentasintensepassion[pathos]rightwhereitisneeded

,Long. Subl.8.4).WhileLonginus, givenhisdissatisfactionwithCaecilius’ work,mustbeconsideredasomewhat prejudicedsource,itseemsfairtodeducefromthesecommentsthatCaecilius’ work onthesublimewasprobablymoredescriptivethananalytical,notsomuchconcernedwithprovidingatheoryofthesublimeaslistingillustrationsofit,an approachparalleledinsomeextantfragmentsofCaecilius’ otherrhetoricalworks.⁹ BeforeCaeciliusthereareintimationsofanotionofthesublimeinrhetoricas farbackasthesophists,aswhenGorgiaswritesabouthowpoetrycanproducea “fearfulshudder” (phrikē periphobos,Gorg. Hel.9)initsauditors.¹⁰ Aristotle remarksinthe Rhetoric onhowanaudienceismade “enthused” or “godpossessed” (enthousiasai)byoratorswhoarethemselves “inastateofenthusiasm ” (enthousiazontes,Arist. Rh.3.7.11)anddeclaresthatspeechrequiresbotha measureof “solemnity” (semnotēta)andtheecstaticcapacity “totakeoneoutof oneself ” (ekstēsai,Arist. Rh.3.8.4).¹¹HisdiscipleTheophrastus,asfarascanbe gleanedfromtheextanttestimonia,seemstohavewrittenabout “themagnificent” (tomegaloprepes,Simplic. Cat.10.30Diels),theorator’spowerto “shock” (ekplēxai)and “ overpower ” (cheirōthenta)anaudience(Ammon. Int.66.6-7 Diels),andthereadingofpoetryasanaidtotheoratorinachieving “sublimity inwords” (inverbissublimitas,Quint. Inst.10.1.27),inQuintilian’sphrase.¹² Theseauthors,andothersbesides,seemtoanticipatethelanguageinwhich Longinuswouldlaterdescribethesublime.

⁷ Onancientcriticismgenerallyseeesp.Russell1981andToo1998.

⁸ Onrhetorical psuchrotēs seeWright2012:108–10.

⁹ SeeInnes2002andPorter2016:184–94.¹⁰ SeePorter2016:314–19. ¹¹Seeibid.289–303.¹²Seeibid.283–9.

BeforetheAugustanperiod,however,perhapstheclearestpredecessorof CaeciliusandLonginusisDemetrius,theauthorofaworkentitled Peri hermēneias,whichmostlikelydatestothesecondorearly firstcentury .¹³ Ratherthanthetripartiteschemaofstyles grand,middle,andplain familiar fromworkslikethe RhetoricaadHerennium,Demetriuspresentsafourfold divisionconsistingofthemagnificent(megaloprepēs),theelegant(glaphuros), theplain(ischnos),andthevehement(deinos).Mostrelevantforourpurposes arethe firstandthelastofthese,thegreat(megaloprepēs)andtheforceful(deinos), bothofwhich,asshowninthepreviouschapter,areLonginiantermsforthe sublime.ForDemetrius,rhetoricalgrandeurormagnificence(megaloprepeia)is equallydiscernibleatthemostelementalleveloflanguage—“thelongsyllableis grandinnature” (φύσειγὰρμεγαλε

,Demetr. Eloc.39),hewritesatone point andatthegenerallevelofsubjectmatter,aswhenthethemeisabattleon landorsea,orsomethingaboutheavenorearth(Demetr. Eloc.75).Aberrant magnificencedevolvesintothefaultof psuchrotēs (Demetr. Eloc.75),thesame qualitythatforLonginusresultsfromafailuretoachievesublimity(Long. Subl 3–4).Forcefulnessorvehemence(deinotēs),ontheotherhand,canbeexpressed throughcompression, “forlengthloosensintensity[sphodrotēta],andmuch meaningdisplayedinafewwordsismoreforceful[deinoteron]” (τὸ γὰ

,Demetr. Eloc 241).¹⁴ Aswithgrandeur,somesubjectsare “forceful” (deinos)inthemselves, specificallysubjectsofmoralinvectivelikeprostitution(Demetr. Eloc.240). Neitherofthesetwostyles,thegrand(megaloprepēs)andthevehement(deinos), exactlycorrespondsonitsowntothesublimeintheLonginiansense.For Demetrius,however,anyofthefourstyles,besidesthecontrarypairingofthe grandandtheplain,canbecombinedwithanyother—“allmixingwithall” (πάνταςμιγνυμένουςπᾶσιν,Demetr. Eloc.37) notablyincludingthecombination ofthegrandandthevehement.Demetriusinfactmakesthispointinresponseto thosewhoclaimthereareonlytwostyles, “ratherattributingtheelegant[glaphuron]totheplain[ischnō],andthevehement[deinon]tothemagnificent [megaloprepei]” (τὸνμὲ

μεγαλοπρεπεῖ τὸνδεινόν,Demetr. Eloc.36).Thecombinationofgrandeur(megaloprepeia)andforcefulness(deinotēs)inDemetriuslooksverymuchlikeaprefigurationofLonginiansublimity.¹⁵

Theword hupsos,inparticular,seemstohavebeen firstemployedasaliterarycriticaltermbythepreviouslymentionedAugustancriticDionysiusof

¹³TheoldestMS,thetenth-centuryBnFCodexParisinusGraecus1741,inoneplaceidentifiesthe authorasDemetriusofPhaleron(c.350–c.280 ),anattributionwhichbecameconventionalbutis nowgenerallyconsiderederroneous;onthedateofthe Perihermēneias seee.g.Grube1961:39–46; Chiron1993:xiii–xl;Innes1999:310–19;Marini2007:8ff.;deJonge2009.

¹

⁴ Onthesenseof deinotēs seeGrube1961:136–7andChiron1993:cii–ciii.

¹⁵ SeeChiron1993:c–ciiandPorter2016:246–82.

17

Halicarnassus,whocouldcallCaeciliusa “dearfriend” (philtatō,Dion.Hal. Pomp.3). Dionysiuswrotenotreatiseofthesublimehimself,butthroughouthisrhetorical worksheevincesaclearinterestinsublimity,whichheoftencalls hupsos.For Dionysiusthesublime(hupsēlon),togetherwiththeintermediate(metaxu)and theplain(ischnon),constitutesoneofthefamiliarthreestyles,butsublimity (hupsos)isalsooneofthevirtuousqualities(aretai)ofspeechingeneral.¹ ⁶ Throughouthisrhetoricaloeuvresublimityisarecurringtopicofinterest. Dionysiusbestdefinesitbyantithesis.WhenheclaimsthatLysias’ styleisnot hupsēlon,heclari fieswhatthislackofsublimitymeans,illustratingbynegation whathetakessublimitytobe:

ThestyleofLysiasisneitherlofty[hupselē]normagnificent[megaloprepēs];not astonishing[kataplēktikē],byZeus,norwonderful[thaumastē];notdisplaying sharpness[topikron]norforcefulness[todeinon]norfear[tophoberon];nor doesithaveagrippingqualityandstrongnotes;norisitfullofspirit[thumou] andinspiration[pneumatos];norisitaspowerfulinitsemotions[pathesin],asit ispersuasiveinitsmorals;norisitasabletoforce[biasasthai]andcompel,asitis topleaseandpersuadeandcharm.Itissafe[asphalēs]ratherthandaring [parakekinduneumenē].

Similarly,inapassageconcernedwith “sublimityofspeech” (tohupsostēslexeōs), Dionysiuswritesthat “onewhoaspirestogreatthings[megalois]sometimesfails” (

)likePlato “aimingatlofty [hupsēlēs]andmagnificent[megaloprepous]anddaring[parakekindyneumenēs] expression” (τῆ

ἐφιέμενον,Dion.Hal. Pomp.2).Hedeclaresthat “thesublimity[hupsos]of Isocrateanartistryisagreat[mega]andwonderful[thaumaston]thing,belonging moretoasemi-divine[hērōikēs]naturethantoahumanone” (θαυμαστὸνγ

φύσεωςοἰκεῖον,Dion.Hal. Isoc.3);thatthespeechesofDemosthenesprovokea stateofenthusiasm(enthousiō)ordivinepossessionandevoketheexperienceof Corybanticdances(taKorubantika,Dion.Hal. Dem.22).Dionysius’ languageand

¹⁶ Dion.Hal. Dem.33, Thuc.23.