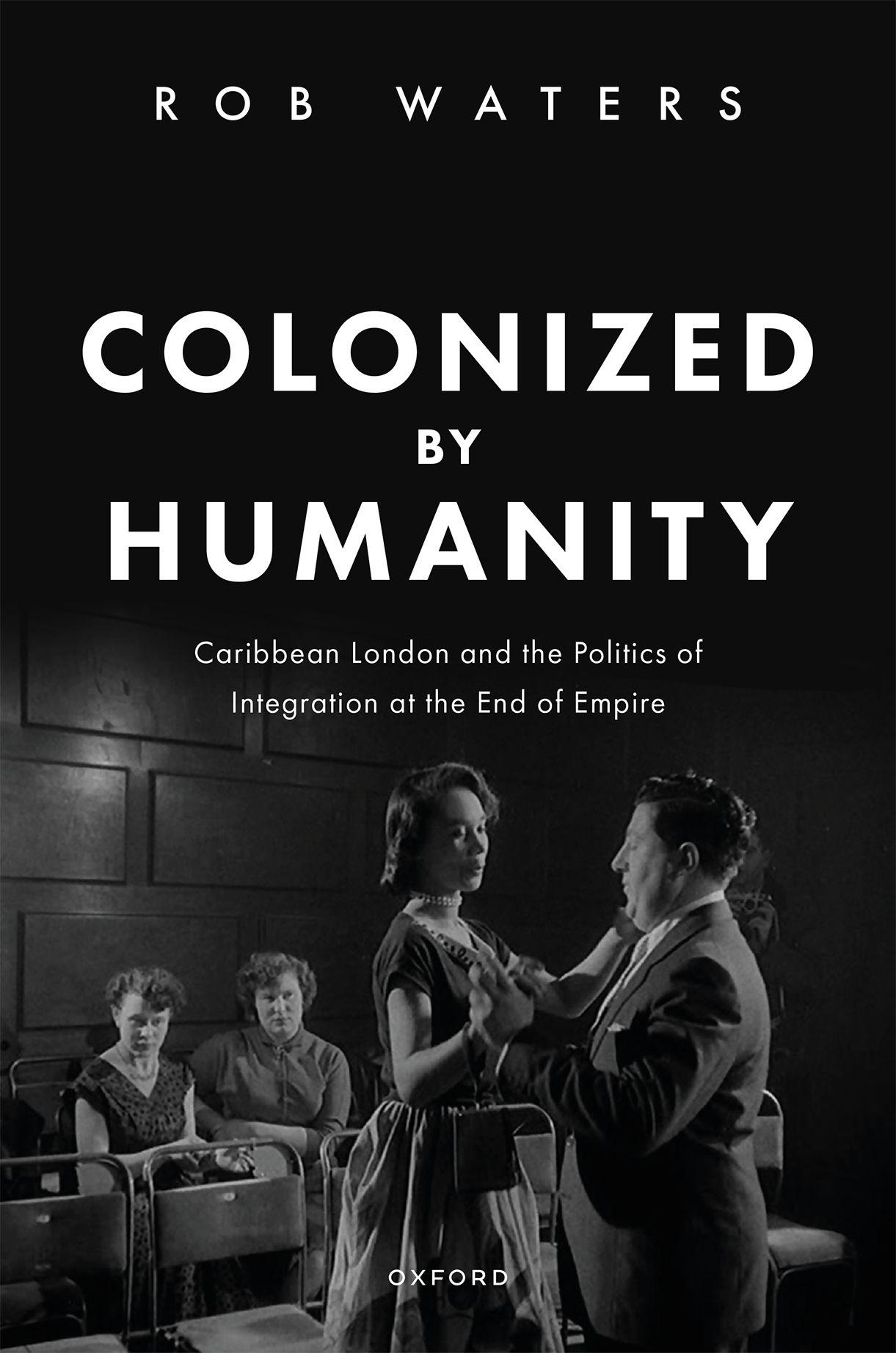

Colonized by Humanity

Caribbean London and the Politics of Integration at the End of Empire

ROB WATERS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Rob Waters 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023938861

ISBN 978–0–19–887983–1

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198879831.001.0001

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

In order to rebuke his aunt, he may marry my niece. I have not only been colonised by his humanity, I have been situated most firmly within the family circle. And everyone knows that families should not quarrel among themselves. It would be silly of me to raise the colour predicament with any member of the family, for we all know that what is wrong is the simple business of the ‘chip’; and we all also know that we, on the inside, are really different from those, meaning black and white—who are on the outside. For it must not be forgotten that white people also have shoulders that are getting more and more ‘chipped’ every day. We are all in the same sea. The tides are treacherous; but our family boat is now seen as a special boat.

GEORGE LAMMING, THE PLEASURES OF EXILE (1960)

Anxious to find some excuse to explain away the daily pin-pricking, I thought my encounters were limited only to the bad English. There were good ones. Decent English people. But where were they? I couldn’t find them, but that they existed I had no doubt. There were journalists, professional people who sat relaxed and self-assured in their living rooms with white friends and after a cold and dispassionate analysis of the situation (a measure of their privilege), condemned in the strongest possible terms English bigotry and prejudice. And if I happened to be there – ‘disgraceful’. They said in their sitting rooms, lighting up their pipes. ‘It’s most outrageous that in a land that professes to be the cradle of justice and liberty . . . but come on, Ken, your glass is empty . . .’. My journalist friend would even make a note in his pocket diary that he had to say something about prejudice in his newspaper diary at the end of the week—a concession to my presence. But life went on just the same when I left the gathering, when I was no longer under the umbrella of (‘disgraceful’, ‘outrageous’) tolerant people.

‘KEN, AN INDIAN FROM TRINIDAD’, IN DONALD HINDS, JOURNEY TO AN ILLUSION (1966)

Come on, now, we must learn to love our neighbours as ourselves. Learn to be tolerant (good word that! A damn’ good British-made word!).

ANDREW

SALKEY, ESCAPE TO AN AUTUMN PAVEMENT (1960)

Acknowledgements

This book was made possible by the generous support of the Leverhulme Trust. In 2017 I was fortunate to be awarded a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship. It allowed me both to finish my first book, Thinking Black: Britain, 1964–1985, and to get started on this one. But for this current book I did, I fear, travel some distance from what I had initially promised to the good people at the Leverhulme Trust. I was funded to write a study of the development of a black political culture in London between the time of the Notting Hill white riots and the Black People’s Day of Action. My wager was that I could reconstruct the development of a distinctive sense of particular London neighbourhoods as ‘black spaces’ in the period after the Notting Hill riots. I wanted to demonstrate that the development of this lived idea of a black neighbourhood had taken shape through far more than the offices and activities of black activists alone—such that an account of it must include all manner of phenomena in the nascent black civil society forged in these years. Much of my initial research for that project ended up finding a home in Thinking Black, but other questions pressed in on me, questions which could not be persuaded into the course I had initially set out for myself.

I became fascinated by a group of interracial societies formed in the 1950s, which had been furiously busy trying to carve out spaces of Caribbean sociability in the metropolis and to ease the position of black Londoners facing—as it was called at the time—the ‘colour bar’. Initially, three groups grabbed my attention: the St John’s Inter-Racial Social and Cultural Club, established in Brixton by the Jamaican Courtney Laws; the Brockley International Friendship Association, founded by three West Indians living in South East London; and the West Indian Standing Conference, an umbrella organization that arose in the late 1950s seeking to provide a wider forum for outfits like the St John’s and Brockley clubs. These were groups that, initially, seemed to fit the bill for exactly what I hoped to investigate: groups concerned, simultaneously, with anti-racism and with black sociability, seeking to reimagine the metropolis in ways that could make black life there a normal and inevitable part of the scene. And yet, there was something in the dynamics of their operation that also pulled in a different direction. They were predominantly middle-class led operations and they saw their social mission as helping out their poorer, usually darker neighbours. Their attitude towards these neighbours swung between identification and repudiation: sometimes defending their rights and embracing the revivified city culture that they appeared to bring into being, sometimes chastising them and urging them to refine themselves—to do away, often, with what were cast as the excesses of their own blackness.

Once I became interested in these social workers and activists, I began to see like-minded people everywhere in the city—a vast network of clubs and societies, official and unofficial, who busied themselves in the politics of race in the postwar metropolis. They constituted, as I describe in this book, the city’s integration infrastructure. This multiracial formation grew continuously in the two decades after the end of the Second World War, before new policies and legislation from Westminster began, slowly, to fold its activities into the emerging field of a government-funded, and more closely directed, race relations ‘industry’ (as it was so often, pejoratively, called). Integration was a formation that interested me precisely for the difficulty that it posed for our account of the development of Britain’s race politics. These integrationists, black and white, were not the forerunners of anti-racist or black liberation movements like those that I had traced in Thinking Black. Not by any stretch of the imagination. And yet, they held some links— often direct—to that later political moment. Their uneasiness around blackness, however, placed them at other points closer to exactly what anti-racists and black liberationists railed against: the anti-immigrationists and racists, many of whom would eventually find a political home in Powellism. How, I wondered, are we to understand these ambivalent figures, who pushed to realize a new, multiracial, integrated city but seemed, so often, to fear or to wish to reform away those same black Londoners whom they sought to defend? Where they have been acknowledged, they have often been dismissed as assimilationists, but this seems too poor a term to cover the complexity of their lives and their mission. Moreover, as I came to realize, while the numbers formally committing themselves to the business of integration were interesting enough, they represented only the tip of the iceberg: the visible outposts of a far larger culture of racial liberalism that held sway in Britain in these years. It was not, I repeat, a force of anti-racism, or not in the way that this term is conventionally used today. But it was a culture that set store by a commitment to values that were described, at the time, as interracialism, multiracialism, or, perhaps with greater circumspection, tolerance. This book attempts to give an account of the culture and politics of integration forged in these years, where it came from, and the legacy that it left.

As with any work of this length, completed over several years and at various different institutional homes, I have accrued many debts along the way. I began it at the Department of History at the University of Sussex and continued it while based at the Department of History at the University of Birmingham. I finish it, now, at my new home in the School of History at Queen Mary University of London. Each has provided me with good company: great colleagues, great students, invigorating conversations. My particular thanks go to those many who have gone out of their way, at these various places, to support my work, or to ask searching questions that have pushed me in new directions: Anne-Marie Angelo, Hester Barron, Gurminder Bhambra, Ben Bland, Michell Chresfield, Joanna Cohen, Tom Adam Davies, Sarah Dunstan, Martin Evans, David Geiringer,

Rachael Gilmour, Rhodri Haywood, Matthew Hilton, Tim Hitchcock, Matt Houlbrook, Simon Jackson, Leslie James, Jill Kirby, Claire Langhamer, JoAnn McGregor, Melissa Milewski, Chris Moores, Mo Moulton, Alastair Owens, Hana Qugana, Sadiah Qureshi, Lucy Robinson, Michael Romyn, Miri Rubin, Robert Saunders, Gavin Schaffer, Bill Schwarz, Amanda Sciampacone, Robbie Shilliam, Gareth Stedman Jones, Barbara Taylor, Zoë Thomas, Dan Todman, Frank Uekotter, Nadia Valman, Kim Wagner, Chloe Ward, and, last but by no means least, Clive Webb. Thanks also to those who have, in other ways, kept me company and fed my ideas over the years: the ‘London Reading Group’ (Shahmina Akhtar, Hannah Elias, Sundeep Lidher, and Anna Maguire); the ‘Marking Race’ group (Nicole Jackson, Marc Matera, Radhika Natarajan, Kennetta Hammond Perry, and Camilla Schofield); Christienna Fryar; Hannah Ishmael; Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite; Philip Murphy, Juanita Cox, and Eve Hayes de Kalaf; and my comrades at the Raphael Samuel History Centre, the George Padmore Institute, and the Institute of Historical Research’s Black British History seminar. The course of the preceding paragraph may imply that my debts are all to professional academic historians and humanities scholars, but of course it is not so. This book owes an immeasurable debt to the archivists and librarians at the Black Cultural Archives, the British Film Institute, the British Library, Hackney Archives, the Institute of Race Relations, Islington Local History Centre, Lambeth Archives, Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre, the London Metropolitan Archives, The National Archives, Queen Mary University of London, the School of Oriental and African Studies, Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, and the University of Warwick. It was at Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, just around the corner from my current place of work, that I first came across Edith Ramsay, whose life was to inspire a significant portion of my arguments here. My deep thanks to the staff at Tower Hamlets, not only for directing me through Ramsay’s archive but also for inviting me to speak on my findings there. Others have been equally generous in offering me an audience beyond the academy, from which I have learned so much: my thanks to Tony Warner of Black History Walks, to Paula Royal of Lambeth Council, to the George Padmore Institute, and to all at What’s Happening Now in Black British History. Thanks, also, to Claudette Parry Laws, with whom I have had many illuminating conversations about Courtney Laws and post-war Brixton. At Oxford University Press, Cathryn Steele, Stephanie Ireland, Matthew Cotton, and Imogene Haslam have each helped me through the editorial and production process with patience and enthusiasm; if my endless queries and anxieties have plagued them, they have had the kindness not to let it show.

I have delivered papers from this project at several seminars and conferences. For hosting me, I want to thank Aaron Andrews, Ruth Craggs, Tom Hulme, Ben Jackson, Peter Jones, Alistair Kefford, Diarmaid Kelliher, Jon Lawrence, Anna Maguire, Helen McCarthy, Naomi Oppenheim, Kerry Pimblott, Nathan Richards,

and Daniel Warner. Some (the foolhardy) even indulged me so far as reading drafts of the manuscript, and for their careful attention and patient suggestions I am much indebted. Thank you to Michael Collins, Hannah Elias, Sundeep Lidher, Anna Maguire, Camilla Schofield, and Bill Schwarz. Susan D. Pennybacker, as well as being a meticulous reader and a great source of conversation and, indeed, critique on the ideas raised in this book, also did me the honour of sharing a couple of the draft chapters with students in the graduate Department of History seminar 810 ‘Colonial Encounters’ in spring 2021 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For their generous engagement, my thanks go to LaRisa Anderson, Nicole Harry, Madeleine McGrady, Tess Megginson, Samir Sefiane, Quinn Shepherd, Julia Short, Pasuth Thothaveesansuk, and Arttu Uuranmaeki. It goes without saying that none of these generous souls should be held responsible for any errors or bad judgements in the final manuscript. That is a cross that I must bear alone.

Finally, my thanks to my family and friends, particularly to Fay, and to my son, Vinnie, to whom the book is dedicated.

Images and epigraphs are reproduced with the kind permission of their copyright holders. For permission to use extracts from E. R. Braithwaite’s To Sir, with Love and Paid Servant, I thank Open Road Media. My thanks to Duke University Press for permission to use an extract from David Scott’s ‘The Sovereignty of the Imagination: An Interview with George Lamming’, Small Axe 6. 2 (2002), 72–200. Thanks to Peepal Tree Press for permission to use an extract from Andrew Salkey’s Escape to an Autumn Pavement. Thanks to Punch Cartoon Library/ Topfoto for permission to use an extract from Elspeth Huxley’s ‘Settlers in Britain: Some Conclusions’, Punch, 1 April 1964. Thanks to Pluto Press for permission to use extracts from George Lamming’s The Pleasures of Exile. Thanks to Aggrey Burke for permission to reproduce Syd Burke’s photograph of Brixton Market. Thanks to Howard Grey for permission to reproduce his photographs of Waterloo station. Thanks to the Evening Standard for permission to reproduce Victor Weisz’s cartoon ‘Notting Hill’, Evening Standard, 19 May 1959. Thanks to the Institute of Race Relations for permission to use an extract from their newsletter of November 1962. Thanks to Getty Images for permission to reproduce the photograph of Michael de Freitas in Hyde Park.

List of acronyms and initialisms

BCWS British Caribbean Welfare Service

BIFA Brockley International Friendship Association

CAB Citizens Advice Bureau

CLP Constituency Labour Party

CPPA Coloured People’s Progressive Association

EWFC East and West Friendship Council

HCWCC Hackney Council for the Welfare of Coloured Citizens

IAC Immigrants Advisory Committee (formerly the West Indian Advisory Committee)

IFL International Friendship League

KRICC Kensington Racial Integration Co-ordinating Committee

LCC London County Council

LCSS London Council of Social Service

LLP London Labour Party

MCPHA Metropolitan Coloured People’s Housing Association

MSD Migrant Services Division

NCCI National Committee for Commonwealth Immigrants

NHHT Notting Hill Housing Trust

WIAC West Indian Advisory Committee

WIFC Willesden International Friendship Council (formerly the Willesden International Friendship Committee)

WISC West Indian Standing Conference (formerly the Standing Conference of Organisations Concerned with West Indians in Britain, and formerly to that the London Leaders Standing Conference)

Introduction

We arrived, I think it was Waterloo or Victoria, I’ve forgotten what station it was, and in those days there were always English crusaders of one kind or another looking for such people.

GEORGE LAMMING1

In the summer of 1962, Howard Grey, a young Englishman who, like his father before him, sought to pursue a career in photography, went to Waterloo station to capture on film the arrival of a boat-train bringing new migrants to London from the West Indies.2 Boat-trains, which brought migrants from the ports of Southampton, Folkestone, and Portsmouth to two of London’s busiest railway terminals at Victoria and Waterloo, were by this time a well-established spectacle in the public drama of West Indian migration to the city. At the time that Grey visited Waterloo, the impending passage of the first Commonwealth Immigrants Act meant that the flow of migration, which had slowed following the horrors of the white riots in 1958, was rising again as many migrants, often wives and children sent for by their husbands and fathers, sought to arrive before the legislation came into force.

Grey shot just one roll of film, a beautiful document that depicts these new migrants dressed in their Sunday best, ‘determined to make a mark, make a favourable impression’.3 They wrestle with overstuffed trunks. They look out, confident and apprehensive at the same time, surveying the city they have just landed in but which they have known, imaginatively, since childhood. Some men lounge against the walls, waiting; mothers nurse their children on the wooden benches of the station forecourt. These are scenes we are habituated to—scenes that repeat across the photographic record of the ‘Windrush’ years of migration. Two of Grey’s photographs, however, show us the moment of arrival from another angle, with the journalists, video cameras, and photographers foregrounded. In one, as the boat-train pulls into a platform on which a small West Indian reception party waits, a cameraman begins shooting as two other journalists ready themselves (Fig. 1). In the other, the same three men move in on the disembarking migrants (Fig. 2).

1 David Scott, ‘The Sovereignty of the Imagination: An Interview with George Lamming’, Small Axe, 6. 2 (2002), 72–200, at 104.

2 ‘Howard Grey’, http://autographabp-iadl.co.uk/artists/howard-grey, accessed 28 October 2019.

3 Stuart Hall, ‘Reconstruction Work: Images of Postwar Black Settlement’ (1984), in Ben Highmore, ed., The Everyday Life Reader (London, 2002), 251–61, at 254.

Grey’s photographs remind us of the other side of the postcolonial encounter to that which has been consolidated in the photographic archive. As the ships and trains of migration rolled in, the historian Bill Schwarz reminds us, the cameras were trained upon them. We have become so used to watching the disembarkations that it is easy to forget that, for the most part, we lack shots like Grey’s, in which we might see, through the eyes of the emigrants, ‘the huddles of journalists and onlookers, police and social workers, white faces all’.4 The reverse shots remind us that, to the same degree that the migrants awaited the city, the city awaited the migrants.

Who, and what, greeted the arrivals? West Indian migrants disembarking from the boat-trains at London’s railway terminals could be sure of a reception party. Alongside family, friends, and the curious were journalists from the local papers,

4 Bill Schwarz, ‘Crossing the Seas’, in Bill Schwarz, ed., West Indian Intellectuals in Britain (Manchester, 2003), 1–30, at 1.

Fig. 1. ‘West Indian Arrivals’. © Howard Grey, 1962.

2. ‘West Indian Arrivals’. © Howard Grey, 1962.

photographers, news anchors, police officers, and not uncommonly representatives of various anti-immigration and fascist groups.5 There were also the representatives of organizations tasking themselves with these migrants’ welfare. Some of these white faces were state-employed, representatives from the Ministry of Labour and the London County Council. But migrants might as likely expect to be greeted by a charitable social worker. A memorable scene from the 1956 BBC drama A Man from the Sun depicts a woman from the Church Army swooping in on lost migrants at Waterloo station to protect them from pimps and direct them to sanctuary. The Salvation Army were also present, as were the Women’s Voluntary Service, the Red Cross, the East and West Friendship Council, the British Council, and more besides.6 These officials and semi-officials were armed with pamphlets introducing migrants to the local infrastructure and with lists of welfare service contacts and explanations of the new institutions of the welfare state. They were, we might recognize, a social manifestation of the border itself, and one that many of the migrants may have encountered also at their ports of embarkation in the

5 ‘At 10.30 p.m. 1.9.1960’, as one Metropolitan Police report records, ‘30 members of the British National Party demonstrated at Waterloo Station on the arrival of 1,200 West Indian immigrants, by shouting “Keep Britain White” and displaying posters.’ Document 27A, MEPO 2/9854, The National Archives (TNA).

6 See Ivo de Souza, ‘Arrival’, in S. K. Ruck, ed., The West Indian Comes to England (London, 1960), 51–62; A Man from the Sun (BBC, 8 November 1956); E. R. Braithwaite, Paid Servant (London, 1962), 155.

Fig.

Caribbean.7 Alongside the white faces were black ones, also offering help. Many were there in an unofficial capacity. In Sam Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners (1956), the protagonist Moses Aloetta makes a habit of travelling to Waterloo to see the boat-train arrive, and before he realizes it he has become ‘like a welfare officer’ taking new arrivals ‘around by houses he know it would be all right to go to’.8 Others took a more systematic approach, manning the station concourses to provide migrants with information on the social organizations of the areas to which they were headed.9 Black Londoners were also present in official roles, working for the Colonial Office and the various Commonwealth High Commissions.

The white faces, the black faces, greeting the arriving migrants: these were representatives of the city’s integration infrastructure, a network of voluntary associations and welfare bodies that stretched from overseas and interracial clubs to international friendship societies, racial brotherhood and unity associations, harmony and goodwill clubs, local council units, East and West Friendship Councils, Quaker clubs, Methodist clubs, socialist fellowships, Citizens Advice Bureaux, settlements, and Councils for Social Service. A report in the Scotsman in 1962 estimated that between eighty and a hundred such organizations existed across the country as a whole, but this was a conservative estimate. In London, where they were concentrated, there were almost a hundred organizations even by 1959.10 By 1964, a year before a new Immigration from the Commonwealth White Paper brought in provisions for funding community relations work that would substantially change the level and kind of activity being undertaken, organizations ran to well over a hundred.11 Cumulatively, these organizations represent a significant but largely overlooked network of social welfare and

7 ‘Bordering’ is described by Nira Yuval-Davis, Georgie Wemyss, and Kathryn Cassidy as the processes that ‘construct, reproduce, and contest borders [to] determine individual and collective entitlements and duties as well as social cohesion and solidarity . . . . Processes of bordering always differentiate between “us” and “them”, those who are in and those who are out, those who are allowed to cross the borders and those who are not’ (Bordering (Cambridge, 2019), 3, 7). Borders have usually been studied as sites of repression, places where people are made ‘illegal’ and made vulnerable to various forms of state sanction and violence. But border-making practices that appear with a benign face deserve our scrutiny too. The reception parties at London’s railway terminals were there to mark the arrival of what they perceived as problematic new citizens and to intervene in those citizens’ lives— the very presence of the reception party made it clear that, the shared citizenship status of these migrants notwithstanding, this was a border crossing. It is worth reminding ourselves, always, which migrations and movements remain unproblematic, devoid of surveillance and interventions, and which attract attention and intervention.

8 Sam Selvon, The Lonely Londoners (London, 2006 [1956]), 3–4.

9 Standing Conference of Organisations Concerned with West Indians in Britain, ‘Agenda for Conference to Be Held at 2.30 p.m. on Sunday, 5 March, at 26 Grosvenor Gardens, S.W.1.’, ACC/1888/117, London Metropolitan Archives (LMA).

10 ‘A Fair Deal for Immigrants’, Scotsman, 21 August 1962, 8. Cf London Council of Social Service, ‘Welfare of West Indians in London: List of Organisations Active in the Field of Race Relations in London’, September 1959, ACC/1888/119, LMA.

11 London Council of Social Service, ‘Welfare of West Indians in London: List of Organisations Active in the Field of Race Relations in London’, July 1964, ACC/1888/036, LMA.

associational culture that set itself to the task of integrating New Commonwealth migrants as they arrived in Britain in the 1950s and early 1960s.

This book is about these workers for integration. It follows the lives and activities of the integrationists, white and black, who worked to build a harmonious multicultural society in London in the two decades before the first Race Relations Act and the state-sponsored race relations infrastructure that it inaugurated. These were decisive decades in the making of postcolonial Britain. The historical realities of colonialism had not yet come to an end, but their end had become historically imaginable.12 What Erik Linstrum has termed the ‘project of disentanglement’ from empire was well underway, even as the question of what came after remained up for grabs.13 The political stakes, for many, were as high in the metropole as in the colonial territories, although this might have been recognized more readily by black and brown colonial migrants than by their white neighbours.14 Amid the turmoil and hope of these years, the integration project certainly appears conservative and timid. It shared the vocabulary of Martin Luther King Jr’s ‘third revolution’ in the United States,15 but while King and his contemporaries voiced the demand for integration in terms of ‘a burning need for justice’, seeking to transform the citizenship rights and social horizons of black America and to end the reign of white supremacy and white terror, in Britain ‘integration’ was used to describe more modest ambitions: ‘harmony’, ‘good will’, an end to the ‘colour bar’, and the beginning of ‘friendship’. Indeed, it was frequently cast as the necessary commitment needed to avoid the social upheaval witnessed in the United States of America.

To see the integration project as part of Britain’s process of becoming postcolonial, however, draws out a neglected but significant dimension of that story. If we are asking how integration as a social fact happened in post-war Britain, it was certainly the social movements that ultimately decided the shape of Britain’s ‘multicultural drift’—a term coined, indeed, as an indictment of the failure of the British state to develop a coherent and strong vision of a multicultural future, which left the gains of multiculturalism in Britain to be decided elsewhere.16

12 Bill Schwarz, Memories of Empire, vol. 2: The Caribbean Comes to England (Oxford, forthcoming).

13 Erik Linstrum in Erik Linstrum, Stuart Ward, Vanessa Ogle, Saima Nasar, and Priyamvada Gopal, ‘Decolonizing Britain: An Exchange’, Twentieth Century British History, 33. 2 (2022), 274–303, at 291.

14 See Kennetta Hammond Perry, London Is the Place for Me: Black Britons, Citizenship and the Politics of Race (Oxford, 2015). The politics of the end of empire could be all-encompassing in the metropole. ‘The world of the young Commonwealth immigrant of the early fifties was full of political talk’, wrote Beryl Gilroy. ‘People slept, dreamt and lived politics. The federation of the Rhodesias, the independence of the Gold Coast, and British exploitation of the Colonies were burned into our throats. We were all going to put this world to rights in five or six moves.’ These battles left their mark on the white English too: ‘Long after the Mau-Mau troubles had died down, the memory still somehow lingered on in deepest suburbia and a black face was enough to resurrect them’ (Black Teacher (London, 1976), 103, 121).

15 Martin Luther King, Jr, Why We Can’t Wait (New York, 2000 [1963]), 2.

16 See Runnymede Trust, The Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain: Report of the Commission on the Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain (London, 2000). The term came from Stuart Hall. See his further elaborations in ‘From Scarman to Stephen Lawrence’, History Workshop Journal, 48 (1999), 187–97; and Essential Essays, vol. 2, ed. David Morley (Durham, 2019), 290.

But the projects for integration that I chart in this book, developed in the 1950s and early 1960s, nonetheless enjoyed the support of the state and became incorporated into official state policy. It was in large part because integrationism in its British articulation offered a version of how the metropole could peacefully transform itself into a postcolonial polity that other, more radical challenges of the postcolonial could be held off: this was integration as a form of Gramscian passive revolution. And yet, the significance of integrationism was more than simply its function, in its formal modes, as an attempt to avoid social conflict or to stave off bigger political transformations. In this book I seek to set out how integration operated as a political rationality, a form of racial liberalism, which both sought to create a new kind of citizen—the integrating citizen, imagined as the ideal subject of this passive revolution—and, in producing that ideal citizen-type, re-enacted colonial, racialized distinctions between the civilized and the savage, the modern and the native. In this form, indeed, integrationism as a racialized rationality of rule was entrenched across the social formation as a whole, operating far beyond the formal cultures and politics of the integration project itself and repeated by black and white alike.

From racism to race

Attending to the history of the development of liberal integrationism in Britain, Colonized by Humanity offers an important counterpoint to the histories of this era that have emphasized the development of racist and anti-immigration politics. And yet, as my earlier comments must suggest, this book does not offer a salve for our historical conscience. Rather, as the title, drawing on an essay by the Barbadian writer George Lamming, indicates, this book identifies the paradox of that liberal vision of the integrationists, which simultaneously worked by an appeal to the virtues of common humanity and presented its vision of humanity in colonial mode: people of colour were to be welcomed into humanity, civilized for integration.17

To return to this history of integrationism I perhaps lay myself open to the accusation of indulging what Kennetta Hammond Perry has called the ‘mystique of British anti-racism’, a phrase Perry uses to explain the endurance of ideas of Britain as a ‘tolerant, liberal, morally virtuous anti-racist nation’ that stand in the way of a reckoning with how race and racism operate in Britain. Black activists had their work cut out dismantling this mystique and necessarily fought their

17 The section of Lamming’s essay from which this phrase is drawn serves as one of the book’s epigraphs. In that essay (‘A Way of Seeing’, in George Lamming, The Pleasures of Exile (London, 2005 [1960]), 56–85 ), Lamming evaluates the terms on which he is invited into ‘civilized’ society by English integrationists. The essay, and Lamming himself, are discussed in greater detail in the final section of Chapter 3.

battles ‘in a context where the world imagined that anti-Black racism didn’t exist’.18 However, pointing to the limits or contraventions of Britain’s selfproclaimed liberalism risks leaving that liberalism itself unexamined. We have, as I see it, a number of different options. Firstly, as Perry does, we could question how ‘liberal’ the British state or British society truly were or are.19 There is certainly a case to make that, when we turn to questions of race, it is the curtailment of freedom that dominates, whether in histories of policing, imprisonment, internment, immigration restriction, deportation, surveillance, or the overturning of civil liberties. Historians unmasking the ‘illiberal’ state concealed behind the veneer of liberal democracy have pointed, equally, to the illiberalism of its populace: the ‘race riots’, the hostilities, and the discriminations which secured their representatives at the heart of government. A second approach might attempt to separate out the ‘liberal’ and ‘illiberal’ elements. The historian Panikos Panayi has urged this method. Noting that the history of ‘official and unofficial racism . . . only points to one side of autochthonous reactions to migrant communities’, Panayi insists that we equally recognize both the accommodation of different ethnicities within the polity, for which he draws a line between Catholic emancipation and the passage of the Race Relations Acts, and the development of ‘positive attitudes’, ‘tolerance’, ‘welcome’, and a harmonious, if uneven, multiculture.20 A third option is to focus on how Britain’s liberal democratic structures have actually provided

18 The quotations are drawn from Reena N. Goldthree, ‘Black Britons and the Politics of Belonging: An Interview with Kennetta Hammond Perry’, Journal of Pan African Studies, 9 (2016), 25–34, at 30. More widely, see Perry, London.

19 Colin Holmes in 1985 defined the task of the historian of race and immigration in Britain as confronting what he termed the ‘myth of fairness’. See Colin Holmes, ‘The Myth of Fairness: Racial Violence in Britain 1911–19’, History Today, 35 (1985), 41–5; Colin Holmes, John Bull’s Island: Immigration and British Society, 1871–1971 (Basingstoke, 1988); Colin Holmes, A Tolerant Country? Immigrants, Refugees and Minorities in Britain (London, 1991). Tony Kushner credits Holmes as the historian who ‘demolished the idea that racism is somehow “unEnglish” ’. See Kushner, ‘Colin Holmes and the Development of Migrant and Anti-Migrant Historiography’, in Jennifer Craig-Norton, Christhard Hoffmann, and Tony Kushner, eds, Migrant Britain: Histories and Historiographies. Essays in Honour of Colin Holmes (London, 2018), 22–32, at 26. This, as Kushner’s colleague Ken Lunn notes, is a founding premise of what is referred to as the ‘Sheffield School’. See Lunn, ‘Uncovering Traditions of Intolerance: The Early Years of Immigrants and Minorities and the “Sheffield School” ’, in CraigNorton et al, eds, Migrant Britain, 11–21. See also Tony Kushner and Kenneth Lunn, eds, Traditions of Intolerance: Historical Perspectives on Fascism and Race Discourse in Britain (Manchester, 1989).

20 Panikos Panayi, An Immigration History of Britain: Multicultural Racism (New York, 2014), quotations at 242, 274, 280. Panayi coins the term ‘multicultural racism’ (318) to describe this ‘contradiction’ between the liberalism and illiberalism he sees defining British race and immigration politics. David Feldman has similarly turned to the history of multiculturalism in Britain to propose that the story of racialization and racism by which the history of race and immigration in Britain is told by historians like Paul Gilroy, Wendy Webster, and Bill Schwarz ‘is less wrong than it is incomplete’ because it fails to take ‘into account a history of pluralism’. See Feldman, ‘Why the English Like Turbans: Multicultural Politics in British History’, in David Feldman and Jon Lawrence, eds, Structures and Transformations in Modern British History: Essays for Gareth Stedman Jones (Cambridge, 2011), 281–302, at 285. Versions of this argument have pointed, also, to the ‘Janus face’ of British multiculturalism, ‘progressive to insiders but regressive to outsiders’. See Nasar Meer and Tariq Modood, ‘Accentuating Multicultural Britishness: An Open or Closed Activity’, in Richard T. Ashcroft and Mark Bevir, eds, Multiculturalism in the British Commonwealth (Berkeley, 2019), 46–66, at 54.

the means for an illiberal politics to gain ground. One such argument sets the liberal and the democratic ideals of the liberal democratic state against one another (what happens, in other words, when racism is voted in?).21 Another points to how immigration and racism ‘pitted liberal principles against each other: freedom of contract versus anti-discrimination and freedom of speech versus the protection of minorities’.22

Reading the racial dynamics of liberal integrationism itself, this book instead seeks to shift the frame through which we understand race as a feature of Britain’s post-war liberal social democracy. As useful as each of the approaches discussed in the previous paragraph are, they tend to leave intact a distinction between an idealized liberalism and its debased or compromised reality, showing us a liberalism defiled by its opposites. It is revealing how often, in many of the works cited earlier, analysis advances by distinguishing the moments of ‘illiberalism’ by which ‘liberalism’ is undone, contradicted, or revealed to be hollow. Separating out the liberals from the illiberals is an analytical approach with a long history, and indeed it was a popular method for understanding race and racism in the 1950s and 1960s, when attempts to quantify the incidence of liberalism and illiberalism in the populace—one-third ‘extremely prejudiced’, one-third ‘mildly prejudiced’, and one-third ‘tolerant’—were common.23 Though the attempts at quantification have diminished, the tendency to speak of a population divided between the ‘positively inclined’ and the ‘hostile’ has continued into the historiography, while governments and politicians are likewise divided up.24 And yet, to cast this

21 ‘In a liberal democratic state’, Panayi writes, ‘a groundswell of hostility influences policy makers, especially during the course of the twentieth century, when Britain has operated upon universal suffrage.’ See Panayi, Immigrant History, 221. A similar argument informs Randall Hansen’s Citizenship and Immigration in Post-War Britain (Oxford, 2000). The political scientists Richard T. Ashcroft and Mark Bevir pose the problem thus: ‘Multiculturalism gives rise to dilemmas for polities such as the UK, which are committed to liberal democracy. Liberal democracy is based on political equality and traditionally safeguards the rights of individuals and minority groups. Yet it is also committed to some form of majority rule, and often uses the law to enforce common moral standards.’ See ‘Multiculturalism in Contemporary Britain: Policy, Law and Theory’, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 21 (2018), 1–21, at 4. See also Holmes, Tolerant Country; Desmond King, ‘Liberal and Illiberal Immigration Policy: A Comparison of Early British (1905) and US (1924) Legislation’, Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, 1 (2000), 78–96; Randall Hansen and Desmond King, ‘Illiberalism and the New Politics of Asylum: Liberalism’s Dark Side’, Political Quarterly, 71 (2000), 396–403.

22 Chris Hilliard, ‘Modern Britain, 1750 to the Present, by James Vernon’, Twentieth Century British History, 30 (2019), 272–5, at 274.

23 See, for example, Anthony Richmond, The Colour Problem: A Study of Racial Relations (Harmondsworth, 1955), 240. Diana Spearman’s attempt to quantify ‘racialism’ in the letters sent to Enoch Powell is a famous example (Spearman, ‘Enoch Powell’s Postbag’, New Society, 9 May 1968).

24 The most direct defence of this approach is found in Mica Nava, ‘Sometimes Antagonistic, Sometimes Ardently Sympathetic: Contradictory Responses to Migrants in Postwar Britain’, Ethnicities, 14 (2014), 458–80 (see also Mica Nava, Visceral Cosmopolitanism: Gender Culture and the Normalisation of Difference (Oxford, 2007); Tony Kushner, We Europeans? Mass-Observation, ‘Race’ and British Identity in the Twentieth Century (Aldershot, 2004), 4). Assessments of government figures, Whitehall officials, and policy programmes similarly often work by placing them within this liberal/ illiberal grid, for example in Hansen’s Citizenship and Immigration

distinction in terms of ‘liberalism’ versus ‘illiberalism’, or ‘tolerance’ versus ‘prejudice’, or the ‘positively inclined’ versus the ‘hostile’, may, as Ali Rattansi has suggested, reveal both a certain ‘coyness’ to the debate and a ‘discursive deracialization’ by which a consideration of the central concerns—race and racism—is either deferred or displaced.25 Deferred alongside this is the question of what the relations of race and racism are to both illiberalism and liberalism. Precisely by implying that illiberalism and racism might be in some measure synonymous, the possibility of a racial or racist liberalism is not confronted. This is an analytical position that I find unsustainable. Building instead on the work of critics who have located racial thinking at the heart of the development of liberalism as a political philosophy and culture, this book offers a reading of what post-war race politics in its liberal guises might look like once we place the racial dynamics of liberalism at the centre of our analysis.26

Colonized by Humanity reads integration as a process for making new kinds of citizens. By attending to the productive ambitions of integration as a politics of citizenship, I turn from a focus on the failed promises of or alternatives to the liberal social-democratic settlement to look instead at how integration worked as a racial dimension of liberal social democracy itself, operating as a civilizing project that turned on self-reform. My concern here is less with rights withheld or won than with the cultural-political rationalities within which integrating

25 Ali Rattansi, ‘The Uses of Racialization: Time-Spaces and Subject-Objects of the Raced Body’, in Karim Murji and John Solomos, eds, Racialization: Studies in Theory and Practice (Oxford, 2005), 271–301, at 277.

26 Race, Amitav Ghosh writes, has operated historically as ‘the ground upon which liberal thought is built’ (Amitav Ghosh and Dipesh Chakrabarty, ‘A Correspondence on Provincializing Europe’, Radical History Review, 83 (2002), 146–72, at 148). Uday Singh Metha offers an extensive analysis of how race, racism, and racialization became integral to the historical development of liberalism as a political philosophy in his Liberalism and Empire: A Study in Nineteenth-Century British Liberal Thought (Chicago, 1999). See also David Theo Goldberg, The Racial State (Malden, 2002); Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, 2008); and, with the greatest nuance, Duncan Bell, Reordering the World: Essays on Liberalism and Empire (Princeton, 2016). The decisive role of racial thinking within the wider culture of liberalism in the nineteenth century is most expertly demonstrated in Catherine Hall’s Civilising Subjects: Colony and Metropole in the English Imagination (Cambridge, 2002). As Goldberg additionally argues, it is not by accident that the coarticulation of race and liberalism have often escaped attention. This is the paradox of liberalism: ‘Race is irrelevant, but all is race’ (David Theo Goldberg, Racist Culture: Philosophy and the Politics of Meaning (Oxford, 1993), 6–7). It is surprising that the readiness with which many historians of the British empire have understood the racial logics of liberalism, as a philosophy, a political economy, and a culture, has made so little impact on how race and liberalism have been studied in histories of the metropole itself. For the twentieth century such concerns have been centred instead on analysis of late- and post-imperial policy in the areas of ‘development’ and ‘aid’, or the constitutional and institutional dimensions of the transition from empire to Commonwealth (see Emily Baughan, Saving the Children: Humanitarianism, Internationalism, and Empire (Berkeley, 2021); Anna Bocking-Welch, British Civic Society at the End of Empire: Decolonisation, Globalisation and International Responsibility (Manchester, 2018); H. Kumarasingham, ed., Liberal Ideals and the Politics of Decolonisation, special issue of Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 46 (2018); Caroline Ritter, Imperial Encore: The Cultural Politics of the Late British Empire (Oakland, 2021)).

citizenship was made in the post-war era.27 Focusing on the enduring rationalities of liberalism as a civilizing project, which formed the background against which political, civil, and social settlements were negotiated, I propose that this project reinscribed race even when it aimed at overcoming its discriminations. Thus, this is not a story about exclusion so much as the terms on which inclusion was offered, the reforms of the self that were demanded, and the ways in which these terms and these reforms depended upon discourses of race.28 Race was deeply

27 In this respect, I turn away from the familiar frame through which the history of race in postwar Britain has been told, which has focused on rights claimed or denied and revolutions promised but forestalled. Accounts focusing on the issue of citizenship rights have taken several angles. Some have explained the withholding, de jure or de facto, of social rights of people of colour in the new social democracy (see, especially, Victoria Noble, Inside the Welfare State: Foundations of Policy and Practice in Post-War Britain (London, 2009), chap. 4; Robbie Shilliam, Race and the Undeserving Poor: From Abolition to Brexit (Newcastle, 2018), chaps 4–5. The black women’s movement long had its finger on the pulse of this traducing of social rights in Britain, particularly in relation to education and healthcare. See Beverley Bryan, Stella Dadzie, and Susan Scafe, The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain (London, 1985)). Critical assessments of the post-war era have also, as we have already noted, held British liberalism to account, pointing to the refusal of civil rights, particularly through attention to policing and the courts, and political rights, with attention focusing particularly on the limits of political representation. The literature is big, but a good summary is provided in John Solomos, Race and Racism in Britain (Basingstoke, 1993). Many of the most effective histories have emerged from the struggles to confront this denial of rights, for example in Roach Family Support Committee, Policing in Hackney: 1945–1985 (London, 1989). On political representation, see, for example, Simon Peplow, Race and Riots in Thatcher’s Britain (Manchester, 2019). The rising interest in black British political history has seen historians paying greater attention to how this refusal of rights was challenged (see Perry, London; Lara Putnam, ‘Citizenship from the Margins: Vernacular Theories of Rights and the State from the Interwar Caribbean’, Journal of British Studies, 53 (2014), 162–91; Matthew Grant, ‘Historicizing Citizenship in Postwar Britain’, Historical Journal, 59 (2016), 1187–206). Others have pointed to how black Britons pressed for new futures beyond liberal social democracy, drawing on the revolutionary promises of anti-colonialism and Marxism (see Minkah Makalani, In the Cause of Freedom: Radical Black Internationalism from Harlem to London (Chapel Hill, 2011); Carole Boyce Davies, Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones (Durham, 2007); Rob Waters, Thinking Black: Britain, 1964–1985 (Oakland, 2019)).

28 I take this approach cognizant of the Jamaican anthropologist David Scott’s critique of the idea of freedom that animates both the denouncements of liberalism’s contradictions and the offer of revolutionary alternatives to it. Following Michel Foucault, Scott refuses that either the contradictions of liberalism and social democracy or liberal social democracy itself are simply blocks to be overcome on the path to freedom. He focuses, instead, on how political modernity, in its metropolitan and colonial forms, transformed the very terrains of the social and the political, altering their rules of engagement. Working by a reformist drive that demanded ‘a suitably reformed, disciplined, and uplifted popular’, these political modernities demanded that ‘disreputable, unrepresentable difference[s]’ were left behind as a condition of entering the public realm. In Scott’s reading, elaborated most effectively in his numerous essays on Jamaica, the question that must animate our discussion of power in the (post) colonial politics of race is its point of application, with ‘the government of conduct’ as its ‘distinctive strategic end’. Rather than focusing on the forms of exclusion from sociopolitical settlements like Jamaica’s, Scott’s approach allows us to see how the terms on which inclusion operates are themselves governed by racial logics, demanding forms of racial uplift and reform that rely precisely on the figuration of a racialized disorderly excess beyond the comprehension and utility of the social: ‘reform depends upon a “norm of civilization” and a division between those who are ready for citizenship and those who have to be made ready for it (blacks, women, the colonized, the working class).’ See David Scott, Refashioning Futures: Criticism after Postcoloniality (Princeton, 1999), 34, 86, 194, 216; David Scott, ‘On the Very Idea of the Making of Modern Jamaica’, Small Axe, 21 (2017), 43–7; David Scott, ‘Political Rationalities of the Jamaican Modern’, Small Axe, 14 (2003), 1–22; David Scott, ‘The Permanence of Pluralism’, in Paul Gilroy, Lawrence Grossberg, and Angela McRobbie, eds, Without Guarantees: In Honour of Stuart Hall (London, 2000), 282–301. The Jamaican case is useful to

rooted in the culture of integration, even if this was not always in forms that were explicitly racist. Race structured the language of integration: supposed racial characteristics were always an implicit part of its categorizations.29 The racial grammar of integrationism meant that for its black subjects, it was always ambivalent: they entered the integration game under the promise that they were progressively reformable—capable of inclusion in the culture of liberal civility—and yet simultaneously they were marked out as interlopers in that culture, their very bodies the signifiers of all that civility was not.30

Although the projects to build an integrated society undertaken in response to the increasing scale of non-white migration to Britain in the immediate post-war era have received far less attention from historians than the efforts made to limit that migration, integrationism was nonetheless a prominent part of both public and private debates in this era and cause for a great deal of new social and political organization. Indeed, getting integration right was a crucial matter for the post-war governing class, many of whom both continued to believe in the special historical role Britain was to play as a racially liberal nation and were painfully aware of the diplomatic costs that publicly abandoning a commitment to that liberalism would incur.31 The appeal of integrationism, moreover, was at least in part its ability to confirm the virtues of a loosely defined British liberalism, the watchwords of which were tolerance, civility, understanding, and conciliation, and the idealized forging ground of which was a strong civil society. These were the values that would continue to define Britain against its elected continental or transatlantic opposites, in which intolerance, incivility, ignorance, and conflict were seen to reign, or in which overreaching states attempted to impose social harmony or division by force.

It was social harmony, above social justice, that concerned integrationists— and this was to be achieved, as far as possible, with minimal state intervention. Both the meaning and means of integration differed across the political formation,

consider not only as a model for understanding how integration worked in Britain but also because integration projects in Jamaica intersected with integration projects in Britain. As Radhika Natarajan has demonstrated, early post-war projects of integration in Britain drew substantially on late-imperial community development programmes, from the West Indies and across the British imperial world (see Natarajan, Empire and the Origins of Multiculturalism: Migrants, Citizenship, and Community in Britain, 1948–1982 (Oxford, forthcoming)). More than this, as I show in Chapter 6, nation-building projects in the former colonial territories unfolded in part as dimensions of British integration politics.

29 I borrow directly, here, from Catherine Hall’s description of the liberal cultures of race that shaped nineteenth-century missionary projects, which I see as important precursors to the integration project of the twentieth century: ‘Race, it was clear, was deeply rooted in English culture. Not always in forms which were explicitly racist, but as a space in which the English configured their relation to themselves and to others . . . . The vocabulary . . . was a racialized vocabulary, for supposed racial characteristics were always an implicit part of categorisations’ (Hall, Civilising Subjects, 8). See also Goldberg’s conception of ‘racial grammar’ in Racist Culture, 46.

30 My emphasis on the ambivalence generated through this dynamic draws, of course, on Homi Bhabha’s work. See Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London, 1994), 118.

31 See Perry, London, 100–4.

but uniting much of it was the common objective to ease the social tensions and potential political conflicts around Britain’s expanding multiculture. This was what the philosopher Adrian Favell calls a consequentialist approach to integration policy, in which the first focus was not on protecting the rights of racialized minorities but on avoiding the public disorders that were seen to be a likely consequence of their presence.32 Indeed, as Favell and others have noted, it was because the emphasis was placed on preventing public disorder and political ruptures around race that both anti-discrimination legislation and anti-immigration legislation could, by the mid-1960s, be presented as mutually reinforcing parts of the same integration policy, a key part of the ‘race relations settlement’.33 The architects of this approach would describe it as inaugurating a ‘liberal hour’ in British race relations from the mid-1960s—though how long this hour lasted, and who was responsible for ending it, remain topics of contention.34 Its history has received little investigation.35 In this book, however, I make a case for returning to the liberal cultures and politics of integration that preceded and shaped the

32 Adrian Favell, Philosophies of Integration: Immigration and the Idea of Citizenship in Britain and France (Basingstoke, 1998), chap. 4.

33 This was the policy position captured in the famous words with which Roy Hattersley introduced Labour’s White Paper on Immigration from the Commonwealth in 1965: ‘without integration limitation is inexcusable, without limitation integration is impossible.’ The 1965 White Paper simultaneously tightened the terms of the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act and established a national coordination body for managing local integration initiatives, the National Committee for Commonwealth Immigrants (see Michael Banton, Promoting Racial Harmony (Cambridge, 1985), 45). Passing immigration restriction in tandem with integration measures as part of a coherent ‘package’ was, in fact, introduced with the 1962 Act, which included the establishment of the Commonwealth Immigrants Advisory Council, but it was the 1965 White Paper, paired with the first Race Relations Act that same year, which formalized the model (see Nadine Peppard, ‘The Age of Innocence: Race Relations before 1965’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 14 (1987), 45–55). A commitment to integration was pursued, to varying degrees, as a policy objective of each of the major political parties, even as the Conservative Party and, by 1963, Labour both also supported limiting non-white migration from the Commonwealth. By 1965, this approach—limiting further non-white immigration while ‘integrating’ those who had already arrived—became the basis of the so-called ‘race relations settlement’, an informal agreement between Labour and the Conservatives to take race out of the field of political debate and disagreement by committing to a dual policy of limiting nonwhite immigration and easing social tensions around race through supporting anti-discrimination legislation and a locally devolved community relations infrastructure. As Wendy Ball and John Solomos describe the ‘race relations settlement’, ‘The common thread was an indirect approach to race issues, tackling them obliquely while maintaining a low political temperature’ (Race and Local Politics (Basingstoke, 1990), 25). Devolving the management of race relations to a local level was a crucial part of this approach. See Romain Garbaye, Getting into Local Power: The Politics of Ethnic Minorities in British and French Cities (Oxford, 2005), chap. 2; Shamit Saggar, ‘The Politics of “Race Policy” in Britain’, Critical Social Policy, 13 (1993), 32–51; Shamit Saggar, ‘Re-Examining the 1964–70 Labour Government’s Race Relations Strategy’, Contemporary Record, 7 (1993), 253–81.

34 The key components defining this ‘liberal hour’ are summarized in Banton, Racial Harmony, 69–70. See also E. J. B. Rose, Colour and Citizenship: A Report on British Race Relations (London, 1969); Mark Bonham Carter, ‘The Liberal Hour and Race Relations Law’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 14 (1987), 1–8; Anthony Messina, ‘Race and Party Competition in Britain: Policy Formation in the Post-Consensus Period’, Parliamentary Affairs, 38 (1985), 423–36.

35 This tendency is beginning to change. See Brett Bebber, ‘The Architects of Integration: Research, Public Policy, and the Institute of Race Relations in Postimperial Britain’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 48 (2020), 319–50; Natarajan, Empire

emerging settlement of the so-called ‘liberal hour’, which were developed in the two decades after the end of the Second World War. This prehistory of the race relations settlement has received even less attention than the settlement itself, but the associational cultures of integrationism in the 1950s laid the foundations of the political settlements of the 1960s, defining, even if loosely, what integration should look like.36 It is in the integrationism of the immediate post-war decades that the issues of integration became defined primarily as matters of conduct, character, and citizenly duty, rather than as matters of racism, discrimination, and structural subordination. The question of racism became individualized and reduced to the banal territory of ignorance and incivility.

The integrationism forged in these years breathed fresh life into the values and social structures of older sociopolitical projects, carrying forth a social vision that was in many respects recognizably Victorian, within the modernizing dynamics of post-war social democracy.37 In their emphasis on the reform of conduct as the condition of entry into the public political nation, integrationists rehearsed a familiar argument of liberal politics in Britain in the transition to mass democracy.38 Indeed, it is part of my argument that the demand for active citizenship and civic culture long promoted by Britain’s voluntary associations and local political cultures in the transition to and early decades of mass democracy continued in the field of integration when it had declined elsewhere. Through the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, associational cultures served as vehicles for democratic claims and sites where the democratic transitions inaugurated by political reforms were managed, as reformers sought to mould new democratic citizens.39 With the advent of social democracy, however, the commitment of voluntary associations to active citizenship largely declined and the political class were more likely to look to the voluntary sector as an instrument to aid the transition to state welfare provision than as a site for

36 See Peppard, ‘Innocence’, 46.

37 Several historians have drawn attention to this continued power of the Victorian past in postSecond World War Britain. See, for example, Frank Mort, Capital Affairs: The Making of the Permissive Society (New Haven, 2010), 4; Lynda Nead, Tiger in the Smoke: Art and Culture in Post-War Britain (New Haven, 2017), 8; Bill Schwarz, Memories of Empire, vol. 1: The White Man’s World (Oxford, 2011), 12; Jeremy Nuttall, ‘The Persistence of Character in Twentieth-Century British Politics’, Journal of Contemporary History, 56 (2021), 96–116.

38 See Catherine Hall, Keith McClelland, and Jane Rendall, Defining the Victorian Nation: Class, Race, Gender and the Reform Act of 1867 (Cambridge, 2000), chap. 2; Peter Mandler, ‘Introduction: State and Society in Victorian Britain’, in Peter Mandler, ed., Liberty and Authority in Victorian Britain (Oxford, 2006), 1–21.

39 Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780–1850 (London, 1987), chap. 10; Frank Prochaska, The Voluntary Impulse: Philanthropy in Modern Britain (London, 1988); Simon Gunn, The Public Culture of the Victorian Middle Class: Ritual and Authority and the English Industrial City, 1840–1914 (Manchester, 2000); M. J. D. Roberts, Making English Morals: Voluntary Association and Moral Reform in England, 1787–1886 (Cambridge, 2004); Susan Pedersen and Peter Mandler, After the Victorians: Private Conscience and Public Duty (London, 1994); Helen McCarthy, ‘Associational Voluntarism in Interwar Britain’, in Matthew Hilton and James McKay, eds, The Ages of Voluntarism: How We Got to the Big Society (Oxford, 2011), 47–68.