Acknowledgements

This book has taken two decades to write, so I have many people to thank for their support, expertise, guidance, and (not least) patience. At the top of this list are my husband, Rob Young, and our son, Adam. Rob has supported me in countless ways at every stage of the research and writing process. Adam has grown up with Materializing the Middle Passage: he was a year old when I began the research and turned 22 as I finished the text. I am sure my boys are mighty glad it is all done at last—but I could not have got there without them.

I am deeply indebted to my friends, who have helped me out in so many ways as this book has taken shape over the years: a huge thank you to Verity Anthony, Julie Evans, Hannah Flint, Sarah Haynes, Julian Haynes, Carsten Heldmann, Mark Jackson, Sophie Moore, Henrik Mouritsen, Caron Newman, Richard Newman, Kirsty Petley, David Richardson, and Debbie Richardson. Thanks also to the allotment that I share with Sarah Haynes—it has been a much-loved sanctuary for the pair of us for a long time, and sometimes we have even managed to grow stuff there.

Materializing the Middle Passage began life with a 2001 Caird Fellowship at the National Maritime Museum. I am most grateful to the Caird Trustees, and especially to Nigel Rigby, who was, at that time, the Director of Research at the NMM. I must thank the museum, first, for letting me loose on their fantastic collections and library resources and, second, for allowing me to spread a one-year fellowship across three years. I asked about that possibility at my interview and was granted it without hesitation; that flexibility allowed me to focus on two works in progress at once (a book and a

small boy): I will be forever grateful. My original Caird research project, centred entirely on the NMM’s own collection, has snowballed over the years into something roughly the size of the Lambert–Fischer Glacier: I do hope the Caird Trustees and the NMM will feel it was all worth the wait.

Maritime and terrestrial archaeologists from many countries have generously furnished information about their work and provided me with images of their wreck sites and artefacts. I am especially indebted to the SlaveryImages:AVisualRecordoftheAfricanSlave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora website (http://www.slaveryimages.org), which has been a much-valued source of inspiration, information, and images in the writing of this book. David Moore and Corey Malcom have both shared their expertise on the Henrietta Marie shipwreck. Special thanks are also due here to the team at Aust Agder Museum, who curate the finds from the Fredensborg wreck, and to Staffin von Arbin, Greg Cook, Karlis Karklins, Michael Cottman, Museum of London Archaeology, and Nigel Sadler. Jerome Handler went to considerable lengths to provide original slides for me from his work at Newton Plantation: I am most grateful to him and to my colleague Mark Jackson, who scanned the Newton images for me. I am also indebted to Adrienne Baron-Tacla for taking me to see Valongo Wharf and the Pretos Novos Institute in Rio de Janeiro, and for facilitating a memorable visit to the finds from Valango. I am grateful also to Helen MacQuarrie, who made it possible for me to see, in Bristol, the artefacts from the Rupert Valley cemetery on St Helena.

This book draws extensively on archive and museum collections, and I have relied throughout on the expertise of a great many archivists, curators, and artefact researchers. Thanks here especially to Bertrand Guillet at the Château des ducs de Bretagne (Nantes), the home of the unique and important images of Marie-Séraphique.I am also indebted to Robert Blyth at the NMM, Jeremy Coote and Ashley Coutu at Pitt Rivers, Suzanne Gott, Tony Coverdale, Vibe Martens, Kenneth Kinkor, Liverpool Museums, and Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. Thanks also to Karl-Eric Svardskog and Henriette

Jakobsen. Michael Graham-Stewart drew my attention to (and provided a copy of) the entry from the log of HMS Sybillediscussed in Chapter 10. I am also very grateful to Sarah Coleman, Margarita Gleba, and Malika Kraamer for sharing with me their ongoing work on the cloth samples in Thomas Clarkson’s chest, curated by Wisbech and Fenland Museum.

Over the last few years, I have been privileged to collaborate on two digital heritage projects for the slavevoyages (Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database) website, alongside David Eltis (Emory), Nicholas Radburn (Lancaster), Bertrand Guillet (Château des ducs de Bretagne), and the brilliant creative team at the Emory Centre for Digital Scholarship, who built the digital models of the French slave ships Aurore and Marie-Séraphiqueused in the slavevoyages videos. My own contribution to these projects has been minor, but my understanding of the appearance and characteristic features of slaving vessels has grown considerably through my involvement with this work.

I have reached out to many other scholars for information about the material world of the slave ship, including Kathleen Murphy (who generously shared her research on the naturalist James Petiver in advance of publication), Stephen Farrell (who in his former role as Senior Research Fellow of the History of Parliament Trust advised me on the workings of eighteenth-century parliamentary committees), Lisa Lindsay (who shared her insights into Robert Norris’s time in West Africa), Andrew Lewis (who provided invaluable advice on the terms of the Dolben Act), Deirdre Coleman (who shared her research on Henry Smeathman), and Katrina Keefer (who shared her work on scarification and allowed me to use one of her reconstruction drawings of marks on the face of an African recaptive).

I have always explored slavery from a diachronic perspective, and discussions with colleagues who work on Roman slavery have impacted this book in important ways. I am especially grateful here to Jennifer Baird, Nick Cooper, Simon Corcoran, Sandra Joshel, Franco Luciani, Henrik Mouritsen, Rebecca Redfern, and Ulrike Roth.

My academic home is the Archaeology section of the School of History, Classics, and Archaeology at Newcastle University. Three iterations of the UK’s RAE/REF research review system rolled by at Newcastle without this book appearing; but, if my colleagues harboured suspicions that Materializing the Middle Passage might never be finished, they did not say so; on the contrary, I have received nothing but encouragement. I would like my co-workers at Newcastle to know that I am truly thankful to be part of such a supportive, inspirational team. I owe a special debt to my friend and colleague Caron Newman for the maps and other images she produced for this book, and for taking on some of the work of organizing image permissions. I have also learned a great deal from former Newcastle graduate students who have shared my interest in slavery, slave ships, West Africa, and postcolonial theory. I am particularly grateful here to Stephanie Moat, Michael Smith, Wendy Smith, and Tom Whitfield. Grants from the School of History, Classics and Archaeology supported the cost of some key images, and indexing.

Colleagues at Newcastle and elsewhere have generously made the time to read and comment in detail on chapters or sections of my draft text. I owe a particular debt to David Eltis and Mark Leone here, but have also benefited from the insights of Katrina Keefer, Lisa Lindsay, and Luis Symanski. I also want to thank Chris Fowler, Diana Paton, Nicholas Radburn, and Rob Young for making time to comment on various aspects and chapters of the book.

A note about images

Every effort has been made to source high-resolution images for this book. In a small number of cases, such pictures did not exist. In these instances, I have elected to include a lower resolution image, rather than leave out important data entirely.

List of Figures

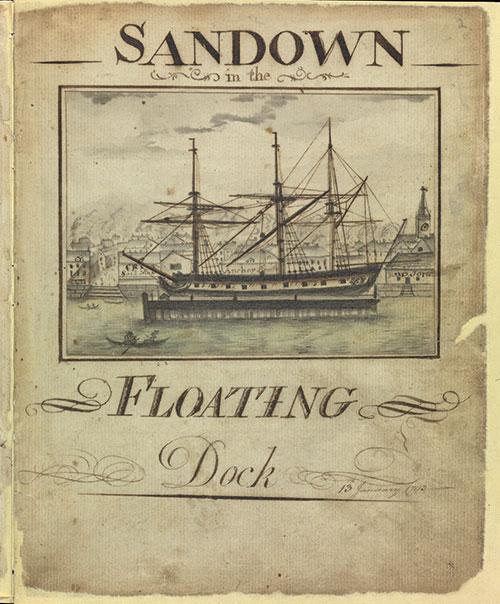

Sandown in the Floating Dock. From the sea journal of Samuel Gamble (1793–4). LOG/M/21, title page. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Elizabeth Finch Hatton and Dido Belle. Possibly by David Martin, c.1780. (The Earl of Mansfield, Scone Palace, Perth)

Enamelled porcelain punch bowl depicting Swallow, probably painted by William Jackson. C.58–1938. (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

Elements of a necklace from grave B72, Newton Plantation, Barbados. (Jerome Handler, Virginia Humanities)

The ‘Guinea’ coast, with the West and Central African countries mentioned in Chapter 2. (Created by Michael Athanson, based on drafts prepared by Caron Newman)

Sketch for the arms and crest granted to John Hawkins, ‘The Canton geven by Rob[er]t Cooke Clar[enceux] King of Arms 1568’. (The College of Arms, London)

Obverse of a 1663 Guinea coin. E1528. (British Museum Images)

The LuxboroughGalley on fire, 25 June 1727. John Cleveley, 1760. BHC.2389. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

The jack (knave) of hearts from a set of playing cards marking the collapse of the South Sea Company. (Kress Collection (Bancroft), Baker Library, Harvard Business School)

The proportions of the 10,480 TSTD slaving voyages undertaken by ships from Britain originating in London, Liverpool, Bristol, and Lancaster. (Image prepared by Caron Newman, using https://(Image prepared by Caron Newman, using https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyages/mOu2kS5A (accessed 21 March 2022))

2.7.

2.8.

2.9. 2.10.

2.11.

3.1.

3.2.

The SouthwellFrigate Trading onye CoastofAfrica, Nicolas Pocock, c.1760. M669. (Bristol City Museums, Galleries, and Archives UK/Bridgeman Images)

The principal zones from which British ships transported African captives. (Created by Michael Athanson, based on drafts prepared by Caron Newman)

Locations of the Gold Coast forts (Ghana) and other principal West African trading sites mentioned in Chapter 2. (Created by Michael Athanson, based on drafts prepared by Caron Newman)

Views of European forts and castles along the Gold Coast. Jan Kip, c.1704. PAH2826. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

‘New World’ disembarkation sites discussed in Chapter 2. (Created by Michael Athanson, based on drafts prepared by Caron Newman)

Gold weight from the Gold Coast (height 62.5 mm). Af1949,08.2. (British Museum Images)

Jean Barbot presents himself to the King of Sestro, 1681. Churchill and Churchill (1732: v, plate G). (British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images)

3.3.

3.4. 3.5.

Lithograph of Hugh Crow (by W. Crane): frontispiece of Crow’s 1830 Memoirs. (Private Collection/Bridgeman Images)

Creamware jug (height 242 mm) bearing the transfer-printed image of a 3-masted ship. Below are the words ‘ SUCCESS TO THE BROOKS CAPT . NOBEL’ . 1994,0718.2. (British Museum Images)

Oval silver epergne by Pitty and Preedy, engraved with the arms of the Town of Liverpool, inscribed: ‘This is one of two Pieces of Silver Plate presented TO JAMES PENNY ESQr by The CORPORATION OF LIVERPOOL 1792’. 1973.278. (National Museums Liverpool)

3.6. 3.7.

Frontispiece of Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative, published in 1789. Based on a painting thought to be the work of the miniaturist William Denton. British Library Board. (All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images)

Ignatius Sancho. Engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi, published by John Bowyer Nichols in 1781. Based on the portrait of Sancho painted by Thomas Gainsborough in 1768. (Michael Graham-Stewart/Bridgeman Images)

4.1.

4.2.

4.3.

4.4.

4.5.

4.6.

Locations of the wreck sites discussed in Chapter 4. (Created by Michael Athanson, based on drafts prepared by Caron Newman)

Model of Fredensborg, built by Terry Andersen. Aust-Agder Museum. (Photo: Karl Ragnar Gjertsen, KUBEN Museum and Archive)

Underwater archaeologist on the site of Adélaïde, wrecked on the coast of Cuba in 1714. (Photo: Christoph Gerigk. Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation)

Site plan of the Elmina wreck, showing the range of artefacts identified, and their locations. (Gregory Cook)

Brick stack on the Havmanden wreck site. (Staffan von Arbin, Bohusläns Museum)

Basket (143 × 165 × 165 mm) created in 2015 by artisans in Mossuril, Mozambique. 2016.168ab. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Open Access (CC0) http://n2t.net/ark:/65665/fd5c1dcaef5-0d51-4e34-8df7-27f2ee6dd95a)

4.7.

4.8. 4.9. 4.10. 5.1. 5.2. 5.3. 5.4.

5.5.

Queen Anne’s Revenge site plan. (Image courtesy of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

Plan of the James Matthews shipwreck. (Western Australia Museum)

Plan of the artefact debris field of ‘site 35F’ (full site name T7a35f-5) (Sea Scape)

Michael Cottman at the site of the Henrietta Marie memorial. (Courtesy of Michael Cottman)

Creamware punch bowl depicting a three-masted ship with the words ‘Success to the LORD STANLEY Capt. Smale’. 146703. (National Museums Liverpool)

The key structural characteristics of a frigate-built merchant slaver. (Illustration prepared by Caron Newman)

Reconstructed preliminary lines plan of James Matthews. (B. Hartley/Western Australian Museum)

The Practice ofSailMaking withthe Tools and ASailLoft, illustrations from Steel (1794: i, unnumbered page preceding 84). (Public domain)

Average (imputed) numbers of captives embarked graphed against TSTD standardized vessel tonnages for British-based vessels between 1680 and 1807. (Data from https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyages/bGGx6qZa (accessed 21 March 2022))

5.6. 5.7.

5.8.

5.9.

Plan of the profile, hold, and decks of Marie-Séraphique made by JeanRené Lhermitte in 1770. (Château des ducs de Bretagnes, Musée d’histoire de Nantes)

William Jackson’s painting ALiverpoolSlave Ship, c.1780. 1964.227.2. (National Museums Liverpool)

The slave ship Fredensborg II, commanded by Captain J. Berg. (Privately owned. Photograph: M/S Maritime Museum of Denmark Picture Archive)

TSTD standardized tonnages plotted against average embarkation levels for British slaving voyages, 1787–1807. (Data from https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyages/mOu2kS5A (accessed 20 March 2022))

5.10.

5.11.

5.12.

5.13. 5.14.

5.15. 5.16.

5.17. 5.18.

A Guinea merchant ship, drying sails. William Van de Velde the Younger, c.1675. PAF6918. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Profile view of the likely appearance of Henrietta Marie (constructed in 1699). From Moore (1997). (‘Henrietta Marie’, Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2617 (accessed May 16, 2022))

Aview ofthe BlandfordFrigate, Nicholas Pocock, c.1760. M761. (Bristol City Museums, Galleries, & Archives/Bridgeman Images)

Hallas illustrated in Hutchinson (1794). (Public domain)

Description ofa Slave Ship. Broadsheet printed by James Phillips London, in 1789. (Private Collection: The Stapleton Collection/Bridgeman Images)

Cross-section of an eighteenth-century slave ship. (Chris Hollshwander/Division of Work & Industry, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

The Anchorage off the Town of Bonny River Sixteen Miles from the Entrance. PAD1929. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Capture of the Spanish slaver Formidable by HMS Buzzardon 17 December 1834, William Huggin. BHC0625. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Method for separating slaves, accompanying the testimony of Robert Heatley, HCSP 69: 123. (Redrawn by Caron Newman)

5.19. 5.20.

6.1.

6.2.

6.3.

6.4.

6.5. 6.6.

French slave ship Marie-Séraphique, Saint Domingue (Haiti), watercolour by unknown artist. (Château des ducs de Bretagnes, Musée d’histoire de Nantes)

Detail from a painting of the slave ship Fredensborg II, dated 1788. (Privately owned. Photograph: M/S Maritime Museum of Denmark Picture Archive)

The Mataró ship model. Marietem Museum Collection (Marietem Museum Rotterdam)

Detail from the lid of an ivory salt cellar, made by an Edo or Owo artist, Benin (Nigeria), c.1525–1600. Af1878,1101.48. (British Museum Images)

Drawing of a mermaid as found in the lakes of Angola, by James Barbot Jnr, from Churchill and Churchill (1732: v, plate 30) (Public domain) Sapi–Portuguese salt-cellar lid, with mermaid figure. EDc 67. (National Museum of Denmark. Photograph by Laila Malene Odyja Halsteen)

A twentieth-century Ibibio (Nigerian) Mami Wata figure. (87 × 61 × 25 cm). 1994.3.9. (Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University. Photograph by Bruce M. White)

Copper alloy Akan gold weight in the form of a single-masted European sailing ship (49 × 88 × 18 mm), eighteenth–nineteenth centuries. nmfa_95-6-3. (Gift of Ernst Anspach, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution. Photograph by Franko Khoury)

6.7.

6.8. 6.9.

6.10.

Undated emblem of Agaja (226 × 138 mm). Wooden finial, covered in silver, depicting a three-masted ship with quarterdeck and two anchors. 1992.40.1 (402.910.001). (Musée Africaine de Lyon. Ji-Elle, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47162707 (accessed 20 August 2022))

Cast of a bas-relief from the Palace of Agaja, Abomey, made by Emmanuel-Georges Waterlot in 1911. 71.2012.0.4166. (RMN Grand Palais/Musée du quai Branly)

Female figurehead, c.1805, attributed to Simeon Skillin Jnr (?1756–1806). M27185. (Peabody Essex Museum)

Three nineteenth-century wooden tomb figures from Brass in the Niger Delta. (Left: 0.4652. Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester. Centre: Ea7825. Bristol City Museums, Galleries, & Archives. Right: AF

6.11. 6.12.

6.13.

5122 University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)

Ancestral screen, duein fubara, eighteenth–nineteenth centuries, Kalabari, Nigeria (1140 × 730 × 420 mm). Af1950,45.333.a. (British Museum Images)

‘Ship-like’ instrument. TM-A-11006. (National Museum of World Cultures, Amsterdam)

Nkisikumbilipanya, Cabinda National Museum of Ethnology. AO253.

(Direção-Geral do Património Cultural/Arquivo e Documentação Fotográfica)

7.1.

7.2.

7.3.

7.4.

7.5.

7.6.

Samples of trade cloth. The West India Company and Board of Directors, Documents and Letters from Guinea, 1705–1722. (Danish National Archives. Photo: Vibe Martens)

European trade knife collected in Senegal in 1787–8 by Anders Sparrman. 1799.02.0083. (Museum of World Cultures, Stockholm)

Chokwe pendant, Angola, sixteenth–eighteenth centuries (279 × 375 mm). 1996.456. (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Seventeenth-century trade beads from the manufacturing site of Nicholas Crisp, Hammersmith Embankment, London. (MoLA. Photo: Karlis Karklins)

Glass trade beads collected in Senegal by Anders Sparrman, 1787–8. 1799.002.0090. (Museum of World Cultures. Stockholm)

Left: powdered-glass bodom bead, probably of nineteenth-century date, made in West Africa. Right: Venetian version of the bodom. 73.3.351 (L) and 73.3.333 (R). Corning Museum of Glass. (Images licensed by The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY (www.cmog.org), under CC BY-NCSA 4.0)

7.7. 7.8. 7.9.

One of the 162 block-print designs for Indiennes made by Favre, Petitpierre et Compagnie (1800–25). (© François Lauginie / Château des ducs de Bretagne, Musée d’histoire de Nantes)

Page from a textile sample book made by the Manchester firm Benjamin and John Bower. 156.4 T31. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.)

Battery-wares made at Saltford Brass Mill. Left: Lisbon pan (350 × 100 mm). Right: Guinea kettle (300 × 190 mm). (Tony Coverdale, Saltford Brass Mill Project)

7.10.

7.11.

7.12.

7.13.

7.14.

8.1.

8.2.

Brass and pewter basin assemblage from the Elmina wreck site. (Gregory Cook)

A strand of akoso beads dating to the eighteenth–nineteenth centuries. (Suzanne Gott)

Ijebu-Ode cloth, handwoven local cotton and imported silk, with brocaded imagery. A.716.29. (National Museums Scotland).

Thomas Clarkson’s chest, opened to show its contents. (Wisbech and Fenland Museum)

A selection of the manillas recovered from the Elmina wreck site. (Gregory Cook)

A. E. Chalon’s portrait of Thomas Clarkson, c.1790. (Wilberforce House/Bridgeman Images)

Box of shells c.1800. Mahogany and pine box with pine trays holding cardboard and glass boxes containing specimens. W.5:1 to 4-2010. (Victoria & Albert Museum)

8.3.

8.4.

8.5. 9.1.

The Grotto at Bulstrode Park, as depicted by Samuel Hieronymus Grimm in 1781. King George III Topographical Collection, 11.1d. (British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images)

Mid-nineteenth-century sailor’s valentine (shells and mahogany), made in the West Indies. (Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images)

The four Bambara cowries gifted to Sarah Sophia Banks by Mungo Park in 1797. SSB 155.4. (British Museum Images)

Mortality rates among captives on British vessels over time imputed estimate. (TSTD data set https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyages/Neg0nOcp (accessed 20 March 2022))

9.2. 9.3.

9.4.

Katrina Keefer’s reconstruction of the markings of Recaptive 5959, Register of Liberated Africans 1814–15, Sierra Leone Public Archives. (Katrina Keefer)

Medical chest of naval surgeon Sir Benjamin Outram (1774–1856). TOA0130. (National Maritime Museum UK, Greenwich, London)

Left: urethral syringe. Right: apothecary’s mortar and pestle. The Queen Anne’s Revenge wreck site. (Images courtesy of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

9.5.

9.6. 9.7. 9.8.

Cupping instruments in leather case, London, England, 1801–1. A606733. (Science Museum, London/Wellcome Collection Images)

An illustration in Le Commerce de l’Ameriquepar Marseille (1764 : ii). Original copper engraving by Serge Daget, 1725. (Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library)

Scrubbing brush (16.2 × 6.0 cm) from the Fredensborg wreck site. AustAgder Museum. (Photo: Karl Ragnar Gjertsen, KUBEN Museum and Archive)

Detail from Résumé du Témoignage Donné Devant un Comité de la Chambre des Communes de la Grande Bretagne et de l’Irelande, Touchant la Traite des Negres, 1814. (Diagram of the Decks of a Slave Ship, 1814, Slavery Images: AVisualRecordofthe African Slave Trade andSlave Life in the Early African Diaspora, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2004 (accessed 30 March 2023))

10.1.

10.2.

10.3.

Snuffbox made from the timbers of HMS BlackJoke. ZBA 2435.4. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Wives andSweethearts, or Saturday Night, 1792: a broadsheet published in London by John Evans. (American Antiquarian Society)

Brass bell from the Benin Kingdom, sixteenth or seventeenth century. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991.17.85. (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence)

10.4.

10.5. 10.6.

Swivel gun, c.1750–1770. Mariners’ Museum and Park, 1935.0029.000001A. (Courtesy of the Mariners’ Museum and Park, Newport News, Virginia)

Transportdes Nègres dans les Colonies. Lithograph by Prexetat Oursel, second quarter of the nineteenth century. (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Chartres, France/Bridgeman Images)

Items of restraint, punishment, and force-feeding purchased by Thomas Clarkson in Liverpool. From Clarkson (1808: i, between pp. 374 and 375). (‘Untitled Image (Iron Shackles)’, Slavery Images: AVisualRecordofthe African Slave Trade andSlave Life in the Early African Diaspora, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2619 (accessed 13 July 2022))

10.7.

Cord-wrapped shackle from the Queen Anne’s Revenge wreck site. (Image courtesy of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural

Resources)

10.8. 10.9.

10.10. 10.11. 10.12.

AMarine &Seaman fishing offthe Anchor on boardthe Pallas in Senegal Road, Jany 75. Gabriel Bray, 1775. PAJ2013. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Mid-eighteenth-century salt-glazed stoneware dish from the wreck of Fredensborg. Aust-Agder Museum. (Photo: Karl Ragnar Gjertsen, KUBEN Museum and Archive)

Deck plan of the Danish ship Rio Volta, constructed in 1777. Neg. A.3457.

M/S Museet for Søfart, Maritime Museum of Denmark. (M/S Museet for Søfart CC-BY-NC-SA)

Sandstone mortar (400 × 250 × 230 mm) from the Fredensborg wreck site. Aust-Agder Museum. (Photo: Karl Ragnar Gjertsen, KUBEN Museum and Archive)

Colorized version of an archived copy of Vue du navire la Marie-Séraphique de Nantes au momentde repas des captives. 2e voyage a Loangue 1771. (Collection Dauvergne, National Maritime Museum, France, Plate No. 9912. Colorization by Ian Burr, Emory University)

10.13. 10.14. 10.15. 11.1. 11.2. 11.3. 11.4.

Group of Negroes as Imported to be Sold for Slaves, 1796. Print of an engraving by William Blake for John Stedman. E.1215E-1886. (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Nineteenth-century naval cat o’ nine tails. NMM TOA0066. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Plan of the slave deck of Marie-Séraphique made by Jean-René Lhermitte in 1770. (Château des ducs de Bretagnes, Musée d’histoire de Nantes)

Colorized reprint of a lithograph from the fold-out sheet (‘Plan and sections of a slave ship’) included in the cover pocket of Carl Wadström’s An Essay on Colonization, 1794. (The Library Company of Philadelphia/Everett Collection/Bridgeman Images)

Illustration by William Butterworth for The Young Sea Officer’s Sheet Anchor. From Lever (1808: plate facing p. 9). (Public domain, Google Digitized)

Trade card of the London plane-maker John Jennion. BM, Heal, 118.8. (British Museum Images)

Illustration by William Butterworth for The Young Sea Officer’s Sheet Anchor. From Lever (1808: plate facing p. 23). (Public domain, Google

11.5.

11.6.

11.7.

Digitized)

Akan drum acquired by Hans Sloane in Virginia. Am, SLMisc.1368. (British Museum Images)

Tobacco pipe from grave B72 Newton Plantation, Barbados. (Jerome Handler, Virginia Humanities)

Left: nineteenth-century Kongo power figure (NkisiNkondi). Right: Minkisi Nkubulu. 1919.01.1162. (L: Dallas Museum of Art, Texas, USA Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of the McDermott Foundation/Bridgeman Images. R: CC by 2.5, Museum of World Cultures, Stockholm)

12.1.

12.2.

12.3.

The scarification marks of John Rock recorded 18 February 1820, after Mullin 1994 29). (Redrawn by Caron Newman)

Scarification marks on the faces of enslaved Africans from Mozambique, Johann Moritz Rugendas, 1835. (‘Brazilian Slaves from Mozambique, 1830s’, Slavery Images: AVisualRecordofthe African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1571 (accessed 29 March 2023))

Beads found with burial B340, New York African Burial Ground. (Adapted by Caron Newman from Bianco et al. (2006: fig. 299); original drawing by M. Schur)

List of Tables

1.1. 2.1.

2.2.

3.1. 3.2.

3.3.

3.4.

3.5.

3.6. 5.1. 5.2. 5.3. 5.4. 6.1.

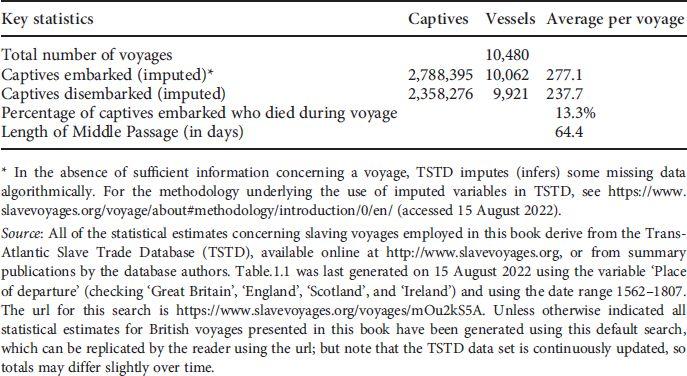

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database summary statistics for slaving voyages outfitted in ports in England, Scotland, and Ireland between 1562 and 1807

Estimated numbers of captives carried away from Africa (by region) on ships originating in Britain between 1562 and 1807

Principal disembarkation points for captives carried away from Africa on voyages originating in British ports between 1562 and 1807

Key slaving logs and journals employed in this study

Key slaving voyage memoirs employed in this study

Key documents published at the behest of SEAST 1788–9 and containing detailed accounts of the Middle Passage

Testimonies by sailors with Middle Passage experience recorded in Substance ofthe Evidence (1789)

House of Commons Sessional Papers (HCSP) containing witness statements made as part of the 1778–92 inquiry process

Key parliamentary inquiry testimonies made by sailors with Middle Passage experience

The nine Liverpool vessels measured in 1788 by Captain Parrey

Characteristics of some of the vessels introduced in Chapter 3, using information drawn from TSTD, Lloyds Register, and details provided in sailors’ accounts

Measurements relating to airflow on the ships measured by Captain Parrey

The metamorphosis of Duke ofArgyle in 1750, as reconstructed from John Newton’s account

Figureheads of some Liverpool-built slave ships of the eighteenth century, where recorded in the Liverpool Registry of Merchant Ships

6.2.

7.1.

7.2.

7.3.

7.4.

8.1.

9.1.

9.2.

11.1.

11.2.

11.3.

12.1.

Popular women’s names employed for British slave ships, and the number of voyages made by ships so named

Trade goods in demand at Cabinda, 1700

Trade goods carried on DanielandHenry, 1700

Trade goods carried on Henrietta Marie, 1699

Cargo of the East India Company ship RoyalCharles, 1661

Individuals with links to the slave trade who collected botanical samples on behalf of James Petiver or transported letters and materials for him

Crew deaths on Samuel Gamble’s Sandown, 1793–4

Sickness and death on Duke ofArgyle, 1750–1

Documented insurrections on British slaving voyages

Infrapolitical actions on Duke ofArgyle, 1751 and African, 1752–3

Weapons used by captives, with the numbers of times each is mentioned in documentary sources

African-born individuals from selected sites in the Americas

1.1.

3.1.

3.2.

5.1.

9.1.

9.2. 10.1.

10.2.