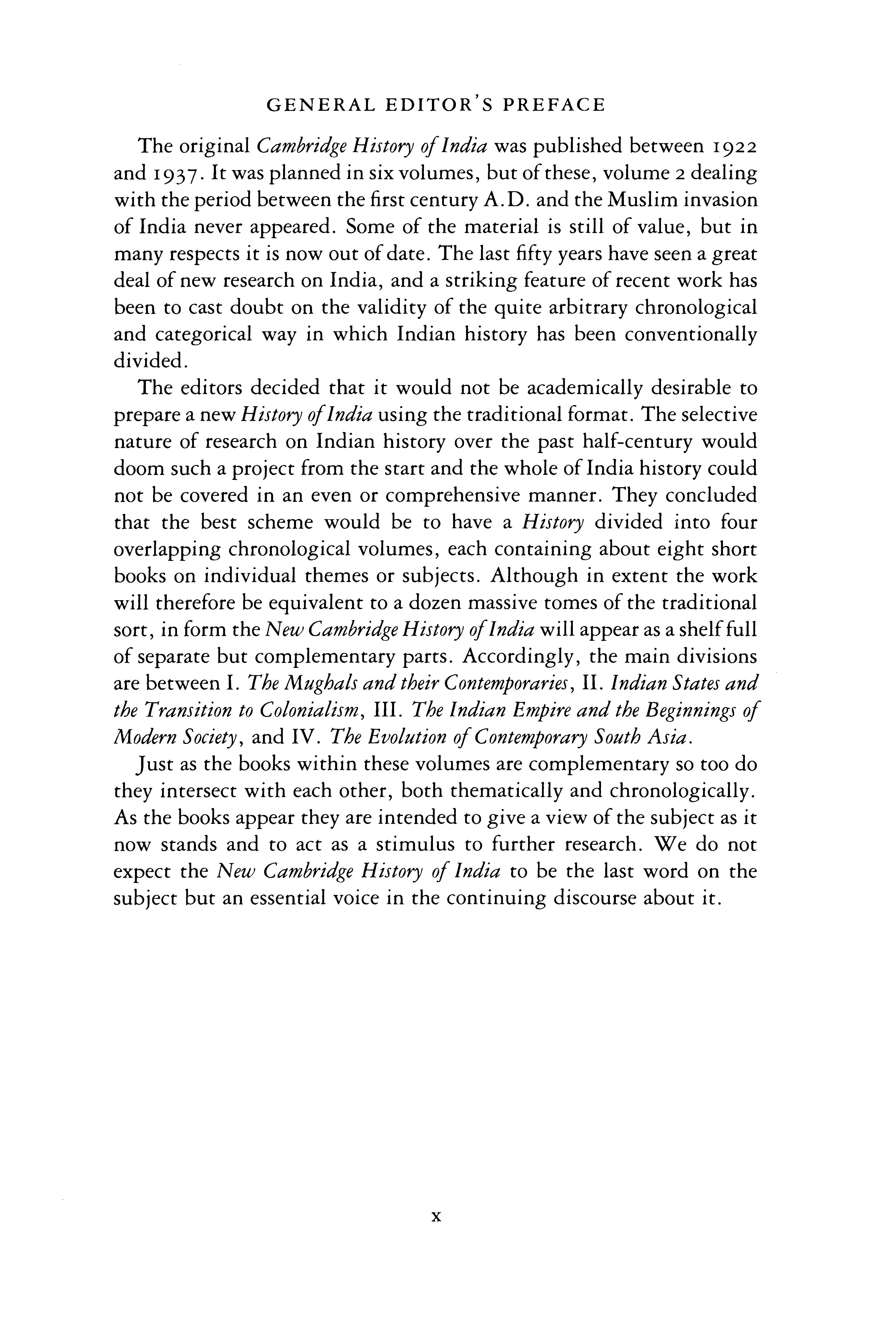

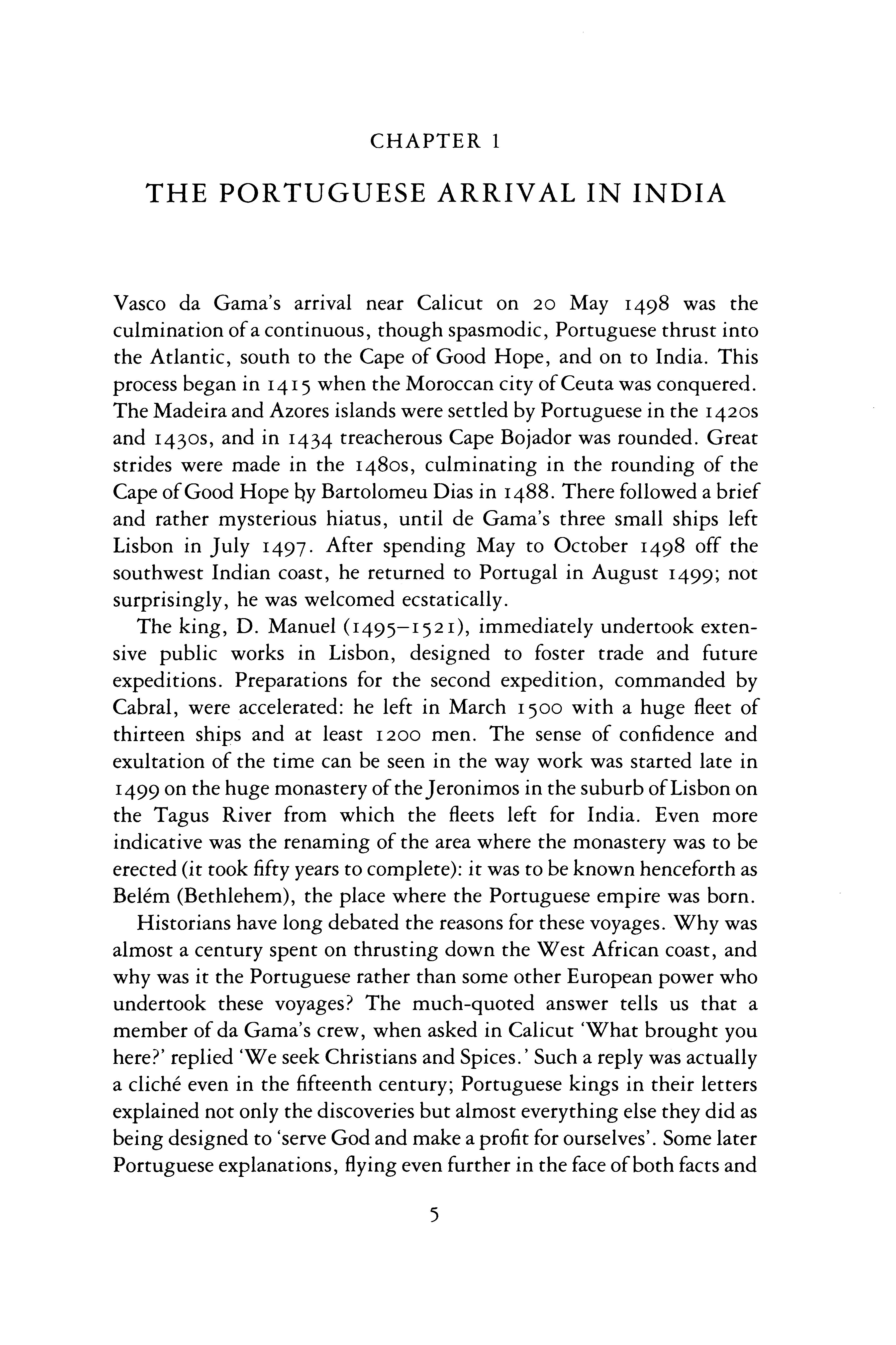

RULERS OF PORTUGAL 1385-191 0

HOUSE OF AVIZ

Joa o I , 1385-143 3

Duarte , 1433- 8

Affonso V , 1438-8 1

Joa o II , 1481-9 5

Manuel I , 1495—1521

Joa o III , 1521-5 7

Sebastian, 1557—78

Henry , 1578—80

HOUSE OF SPANISH HABSBURGS

Phili p II (I of Portugal) , 1580-9 8

Phili p II I (II of Portugal) , 1598-162 1

Phili p IV (III of Portugal) , 1621-4 0

HOUS

E O F BRAGANCJA

Joa o IV , 1640—56

Affonso VI , 1656-6 7

Pedr o II , 1667—1706

Joa o V , 1706—50

Jose , 1750-7 7

Maria I , 1777—92

Joa o VI , 1792—1826

Pedr o IV , 1826-3 4

Miguel , 1828—34

Maria II , 1834—53

Pedro V , 1853-6 1

Luis I , 1861—89

Carlos I , 1889—1908

Manuel II , 1908-1 0

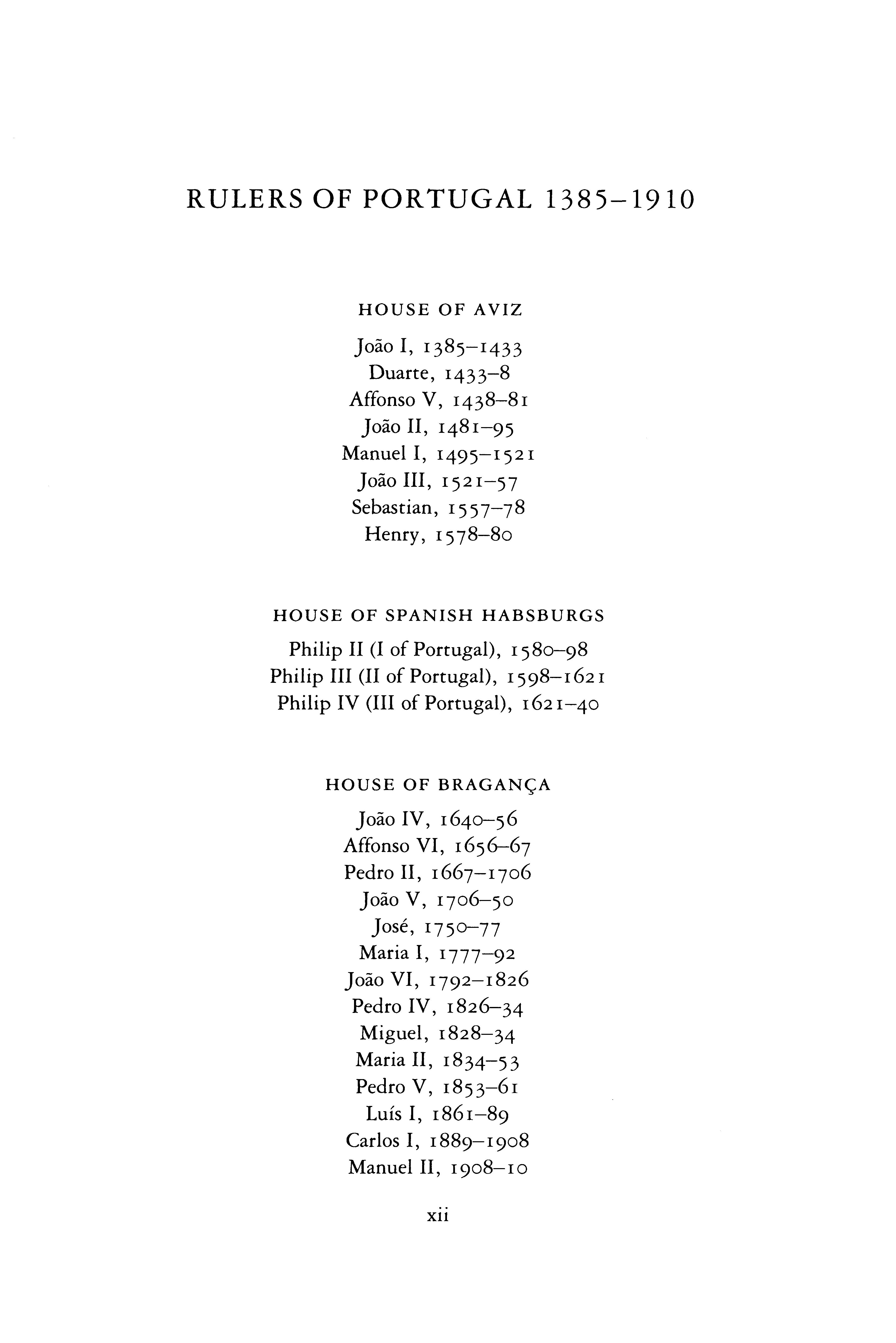

VICEROY S AN D GOVERNOR S OF PORTUGUES E INDI A 1505-196 1

All viceroys were also governors. Thus the serial number refers to governorships; those governors who were further honoured by being called viceroys have an asterisk. Gaps in the sequence, as between numbers 53 and 54, are because in these years there was a Council of Government. With a few exceptions, I have not includedtitles.

1* Francisc o d e Almeida , 1505- 9

2 Afonso d e Albuquerque , 1509—15

3 Lopo Soares d e Albergaria , 1515-1 8

4 Diog o Lopes d e Sequeira , 1518-2 2

5 Duart e d e Meneses , 1522—4

6 * Vasco d a Gama , 152 4

7 Henriqu e d e Meneses , 1524—6

8 Lop o Vaz d e Sampaio , 1526- 9

9 Nun o d a Cunha , 1529-3 8

10 * Garci a d e Noronha , 1538-4 0

11 Esteva o d a Gama , 1540—2

12 Marti m Afonso d e Sousa, 1542- 5

13 * Joa o d e Castro , 1545- 8

14 Garci a d e Sa, 1548- 9

15 Jorg e Cabral , 1549-5 0

16 * Afonso d e Noronha , 1550- 4

17 * Pedr o Mascarenhas , 1554- 5

18 Francisc o Barreto , 1555- 8

19 * Constantin o d e Bragan^a , 1558—61

20 * Francisc o Coutinho , 1561—4

2 1 Joa o d e Mendon^a , 156 4

22 * Anta o d e Noronha , 1564- 8

23 * Lui s d e Ataide , 1568-7 1

24 * Antoni o d e Noronha , 1571- 3

2 5 Antoni o Moni z Barreto , 1573- 6

2 6 Diog o d e Meneses , 1576—8

27 * Luis d e Ataide , 1578-8 1

VICEROY S AND GOVERNOR S 1505-196 1

28 Fernao Teles de Meneses, 1581

29 * Francisco Mascarenhas, 1581—4

30 * Duart e de Meneses, 1584—8

31 Manuel de Sousa Coutinho , 1588—91

32 # Matias de Albuquerque , 1591—7

33 * Francisco da Gama , 1597—1600

34 * Aires de Saldanha, 1600—5

35 * Marti m Afonso de Castro, 1605- 7

36 Frei Aleixo de Meneses, 1607- 9

37 Andre Furtado de Mendonga, 1609

38 * Rui Lourenc:o de Tavora, 1609-1 2

39 * Jeronim o de Azevedo, 1612—17

40 * Joao Coutinho , 1617-1 9

4 1 Fernao de Albuquerque , 1619-2 2

42 * Francisco da Gama , 1622- 8

4 3 Frei Luis de Brito e Meneses, 1628—9

44 * Miguel de Noronha , Conde de Linhares, 1629—35

45 * Pero da Silva, 1635- 9

4 6 Antoni o Teles de Meneses, 1639—40

47 # Joao da Silva Telo e Meneses, 1640- 5

48 * Filipe Mascarenhas, 1645-5 1

49 * Vasco Mascarenhas, Conde de Obidos , 1652—3

50 * Rodrigo Lobo da Silveira, 1655—6

51 Manuel Mascarenhas Homem , 1656

52 * Antoni o de Melo e Castro, 1662—6

53 * Joao Nune s da Cunha , 1666—8

54 * Luis de Mendonc^a Furtado e Albuquerque , 1671—7

55 * Pedro de Almeida Portugal , 1677- 8

56 * Francisco de Tavora, 1681- 6

57 Rodrigo da Costa, 1686-9 0

58 Miguel de Almeida, 1690- 1

59 * Pedro Antoni o de Noronh a de Albuquerque , 1692- 8

60 * Antoni o Luis Gongalves da Camara Coutinho , 1698-170 1

6i # Caetano de Melo e Castro, 1702—7

62 * Rodrigo da Costa, 1701-1 2

63 * Vasco Fernandes Cesar de Meneses, 1712—17

64 Sebastiao de Andrade Pessanha, 1717

65 * Luis Carlos Inacio Xavier de Meneses, 1717—20

66* Francisco Jose de Sampaio e Castro, 1720- 3 xiv

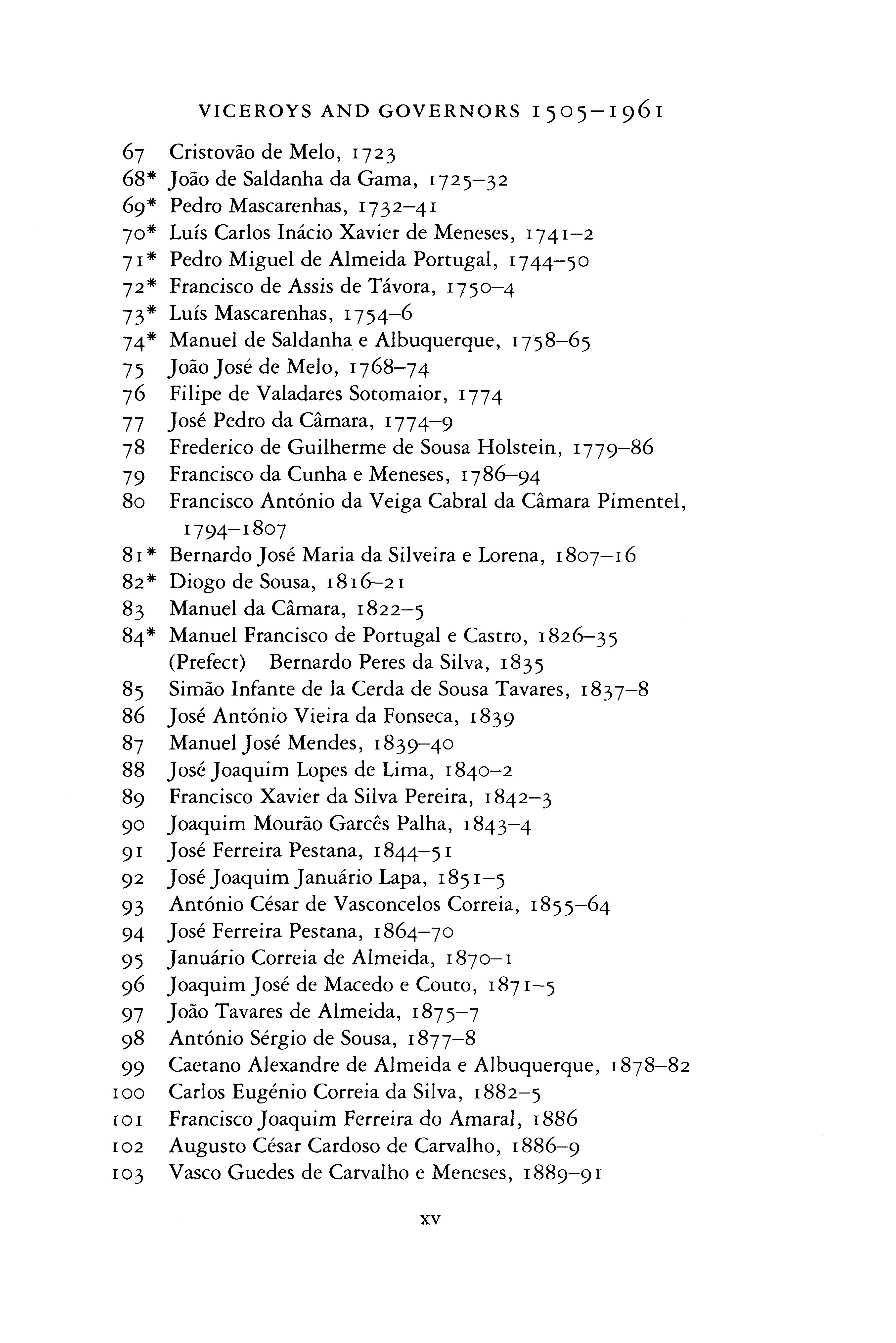

VICEROY S AN D GOVERNOR S 1505-196 1

67 Cristovao de Melo , 1723

68 * Joa o de Saldanha da Gama , 1725—32

69 * Pedr o Mascarenhas, 1732—41

70 * Luis Carlos Inacio Xavier de Meneses, 1741- 2

71 * Pedr o Migue l de Almeid a Portugal , 1744—50

72 * Francisco d e Assis d e Tavora, 1750—4

73 * Luis Mascarenhas, 1754- 6

74 * Manuel de Saldanha e Albuquerque , 1758—65

7 5 Joa o Jos e d e Melo , 1768-7 4

7 6 Filip e de Valadares Sotomaior, 1774

77 Jos e Pedro da Camara, 1774- 9

7 8 Frederico de Guilherm e de Sousa Holstein , 1779-8 6

7 9 Francisco da Cunh a e Meneses, 1786—94

8 0 Francisco Antoni o da Veiga Cabral da Camara Pimentel , 1794-180 7

8 1 * Bernardo Jos e Maria da Silveira e Lorena, 1807—16

82 * Diog o de Sousa, 1816-2 1

8 3 Manuel da Camara, 1822- 5

84 * Manue l Francisco de Portuga l e Castro , 1826—35 (Prefect) Bernardo Peres da Silva, 1835

85 Simao Infante de la Cerda de Sousa Tavares, 1837- 8

8 6 Jos e Antoni o Vieira da Fonseca, 183 9

87 Manuel Jos e Mendes , 1839-4 0

8 8 Jos e Joaqui m Lopes de Lima, 1840- 2

8 9 Francisco Xavier da Silva Pereira , 1842- 3

9 0 Joaqui m Mourao Garces Palha , 1843—4

9 1 Jos e Ferreira Pestana , 1844-5 1

92 Jos e Joaqui m Januari o Lapa, 1851—5

9 3 Antoni o Cesar de Vasconcelos Correia, 1855—64

9 4 Jos e Ferreira Pestana , 1864—70

95 Januari o Correia de Almeida , 1870- 1

9 6 Joaqui m Jos e de Macedo e Couto , 1871- 5

97 Joa o Tavares de Almeida , 1875- 7

9 8 Antoni o Sergio d e Sousa, 1877- 8

9 9 Caetano Alexandre de Almeid a e Albuquerque , 1878—82

100 Carlos Eugeni o Correia da Silva, 1882—5

101 Francisco Joaqui m Ferreira d o Amaral , 188 6

102 August o Cesar Cardoso de Carvalho, 1886- 9

103 Vasco Guedes de Carvalho e Meneses, 1889-9 1

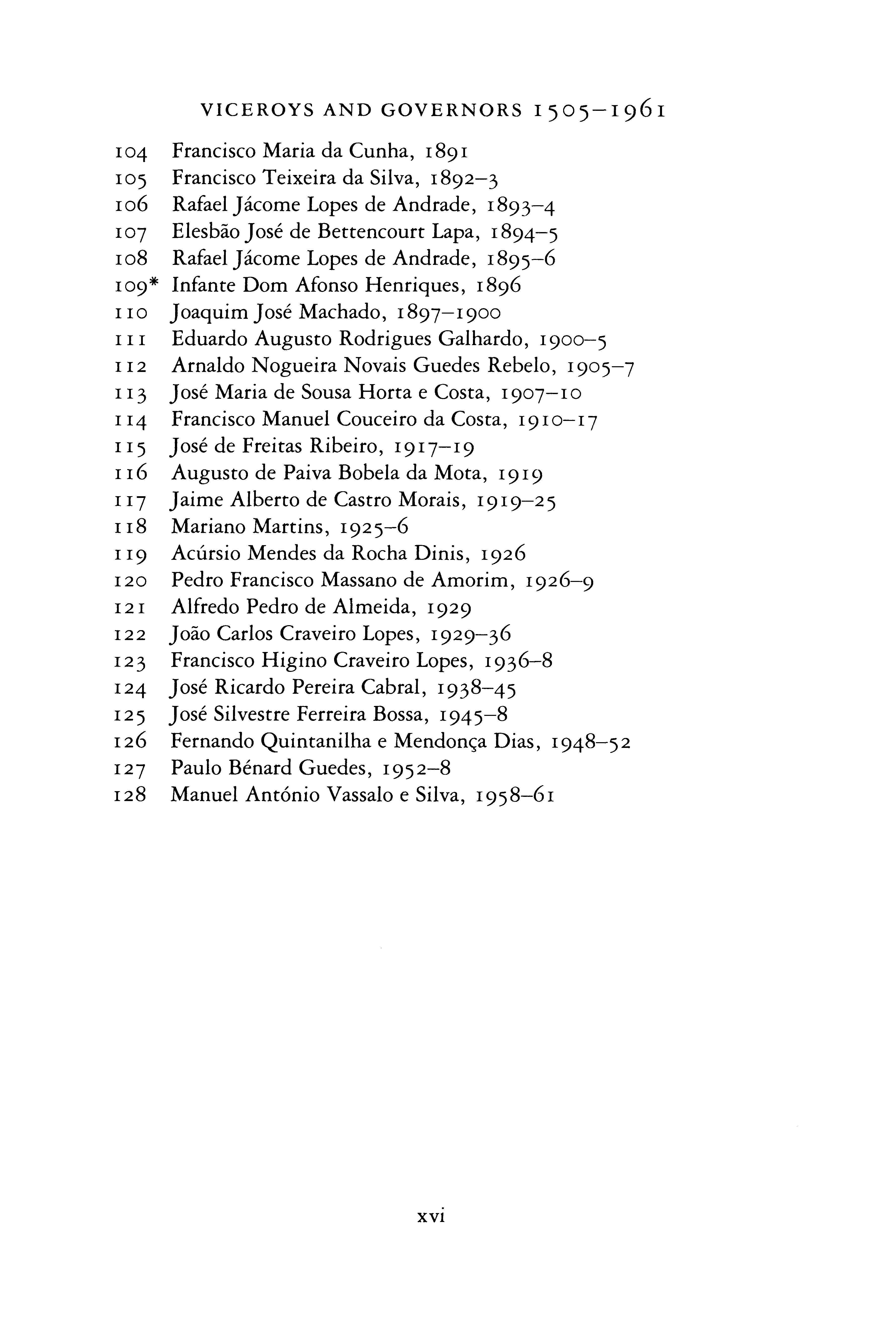

VICEROYS AND GOVERNOR

S 1505-196 1

104 Francisco Maria da Cunha, 1891

105 Francisco Teixeira da Silva, 1892—3

106 Rafael Jacome Lopes de Andrade, 1893—4

107 Elesbao Jose de Bettencourt Lapa, 1894- 5

108 Rafael Jacome Lopes de Andrade, 1895- 6

109* Infante Dom Afonso Henriques , 1896

n o Joaquim Jose Machado, 1897-1900 in Eduardo Augusto Rodrigues Galhardo, 1900—5

112 Arnaldo Nogueira Novais Guedes Rebelo, 1905- 7

113 Jose Maria de Sousa Hort a e Costa, 1907-1 0

114 Francisco Manuel Couceiro da Costa, 1910—17

115 Jose de Freitas Ribeiro, 1917-1 9

116 Augusto de Paiva Bobela da Mota, 1919

117 Jaim e Alberto de Castro Morais, 1919—25

118 Mariano Martins , 1925- 6

119 Acursio Mendes da Rocha Dinis , 1926

120 Pedro Francisco Massano de Amorim , 1926- 9

121 Alfredo Pedro de Almeida, 1929

122 Joao Carlos Craveiro Lopes, 1929-3 6

123 Francisco Higin o Craveiro Lopes, 1936- 8

124 Jose Ricardo Pereira Cabral, 1938-4 5

125 Jose Silvestre Ferreira Bossa, 1945- 8

126 Fernando Quintanilh a e Mendonga Dias, 1948-5 2

127 Paulo Benard Guedes, 1952- 8

128 Manuel Antonio Vassalo e Silva, 1958-6 1

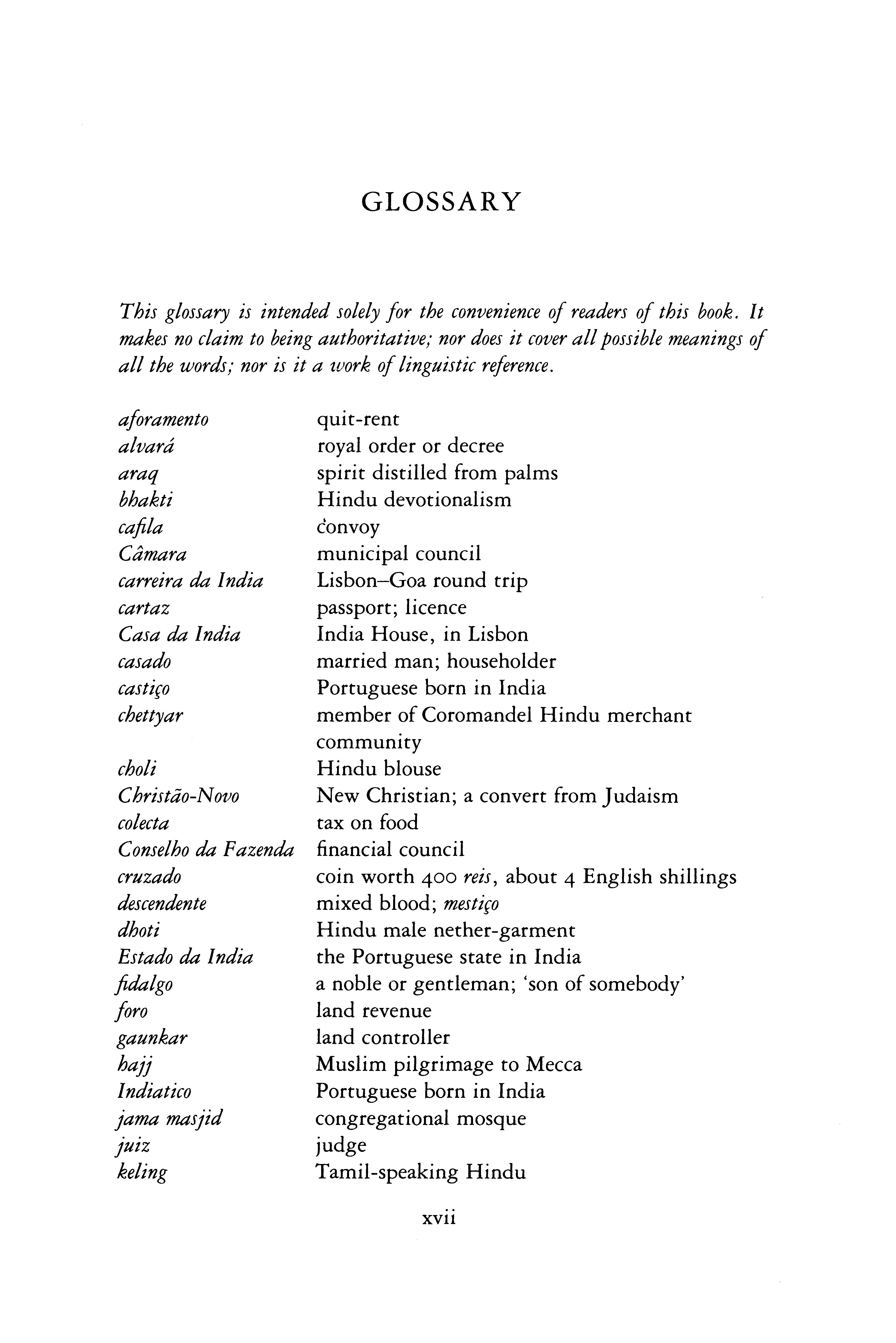

GLOSSAR Y

This glossary is intended solely for the convenience of readers of this book. It makes no claim to being authoritative; nor does it cover all possible meanings of all the words; nor is it a work of linguistic reference.

aforamento alvard

araq bhakti cafila

Camara carreira da India cartaz

Casa da India casado

castico chettyar

choli

Christdo-Novo colecta

Conselho da Fazenda cruzado descendente

dhoti

Estado da India fidalgo foro

gaunkar hajj

Indiatico

jama masjid

juiz

keling

quit-ren t

royal order or decree

spiri t distille d from palm s

Hind u devotionalis m convoy municipa l council

Lisbon—Goa roun d tri p passport ; licence

Indi a House , in Lisbon marrie d man ; householder Portugues e bor n in Indi a membe r of Coromande l Hind u merchan t communit y Hind u blouse

Ne w Christian ; a convert from Judais m tax on food

financial council coin wort h 40 0 reis, abou t 4 Englis h shilling s mixed blood ; mestizo

Hind u mal e nether-garmen t th e Portugues e stat e in Indi a a noble or gentleman ; 'son of somebody' land revenue land controlle r

Musli m pilgrimag e t o Mecca Portugues e born in Indi a congregationa l mosqu e judg e

Tamil-speakin g Hind u

mestizo ndo

padroado pan pandit paroe quintal reinol rendas roteiro ryotwari

satyagraha

Senado da Cdmara soldado sudra taluka tanador-mor vania

vedor da fazenda zamorin

GLOSSARY

Eurasian; a person of Indo-Portugues e ancestry large shi p patronag e bete l leaf

Hind u teacher light , oared boat

abou t i hundredweigh t (5 1 kgms ) Portugues e bor n in Portuga l tax-farming contract s rutter ; navigationa l guid e Hind u system unde r whic h th e stat e takes a proportio n of th e actual productio n of every cultivatin g family

'trut h force'; Gandhia n pacifist resistance municipa l council soldier; an unmarrie d ma n botto m grou p in th e Hind u caste hierarchy distric t

overseer

membe r of Gujara t Hind u or Jai n merchan t communit y chief financial official

titl e of th e ruler of Calicu t

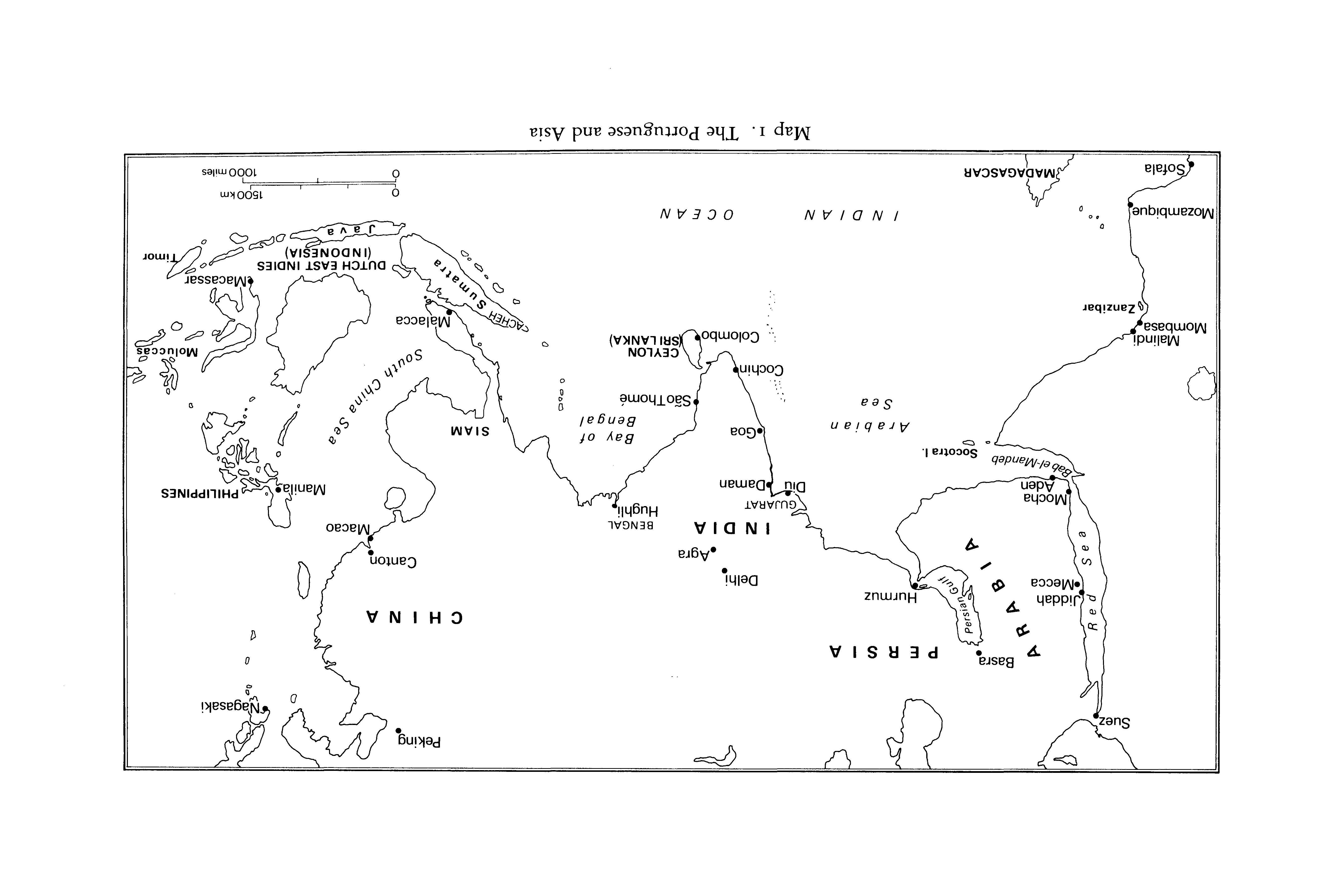

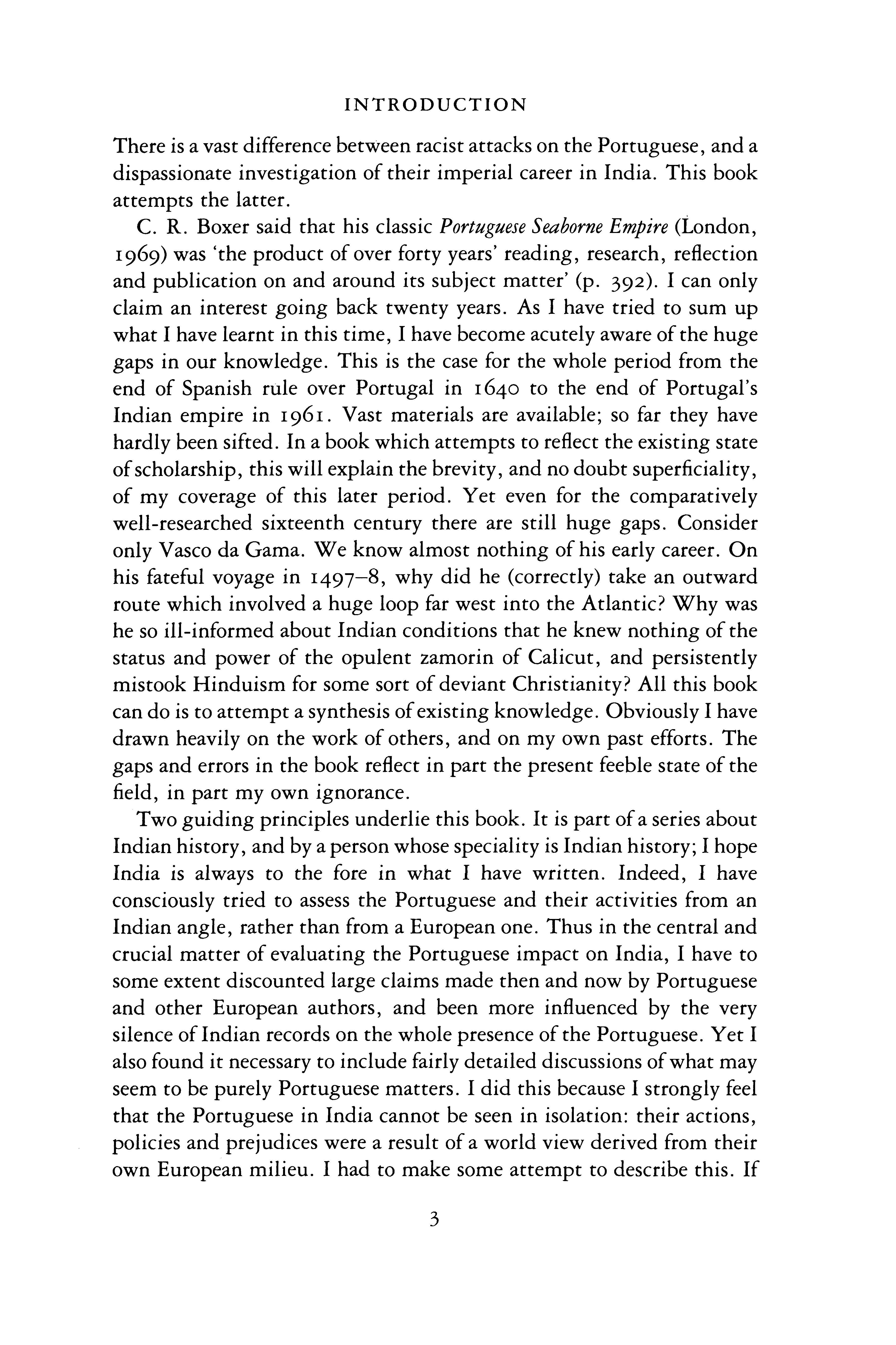

Malindi Mombasa

GUJARAT

Diu">Dama n BENGAL Hughli Mocha Aden

Bay of Bengal SaoThome Arabian Sea (\CEYLON Colombo\J SR I LANKA ) Macassar DUTCH EAST INDIES (INDONESIA) imor

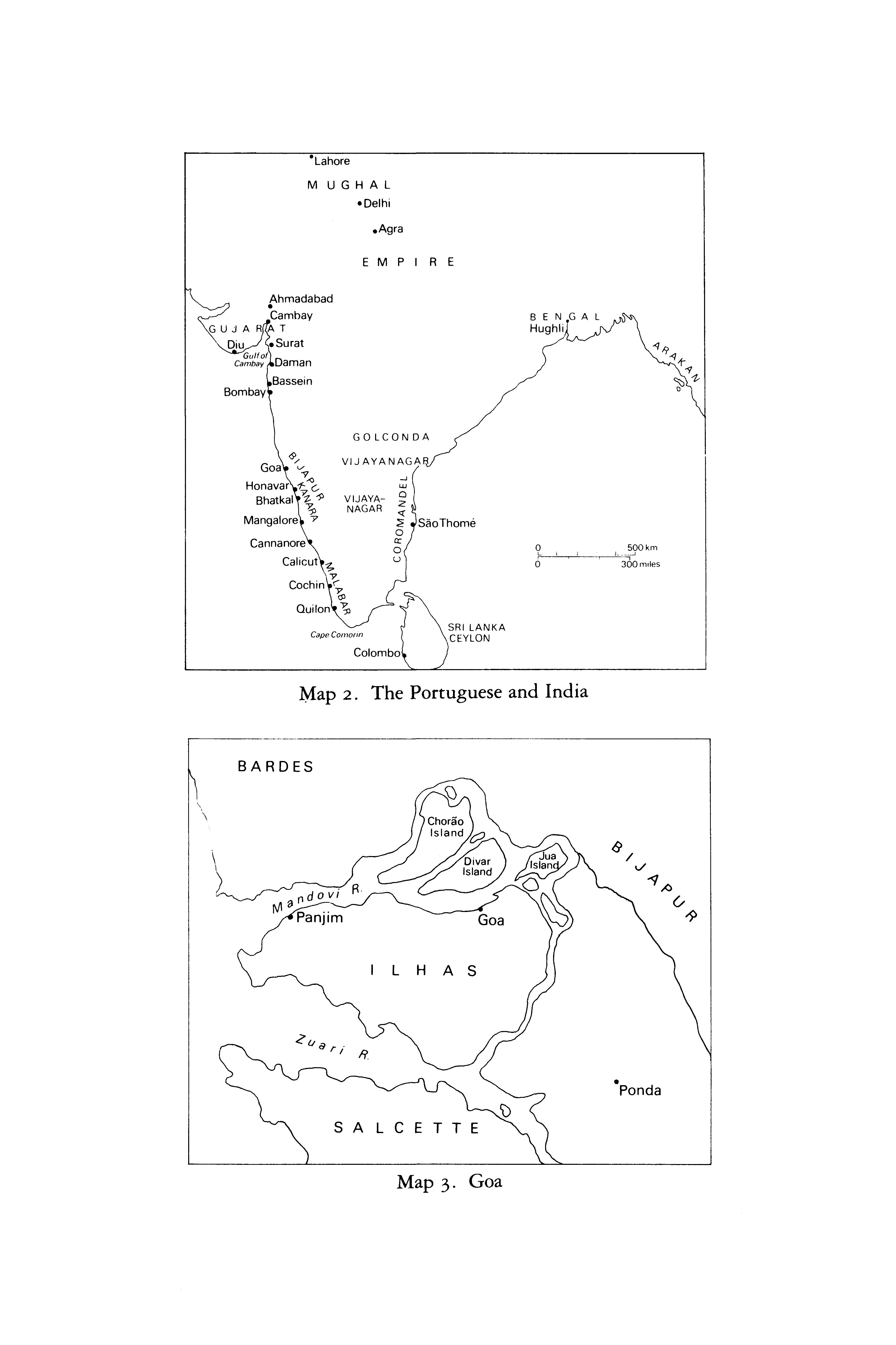

Map i . Th e Portugues e and Asia

PHILIPPINES

INDIAN

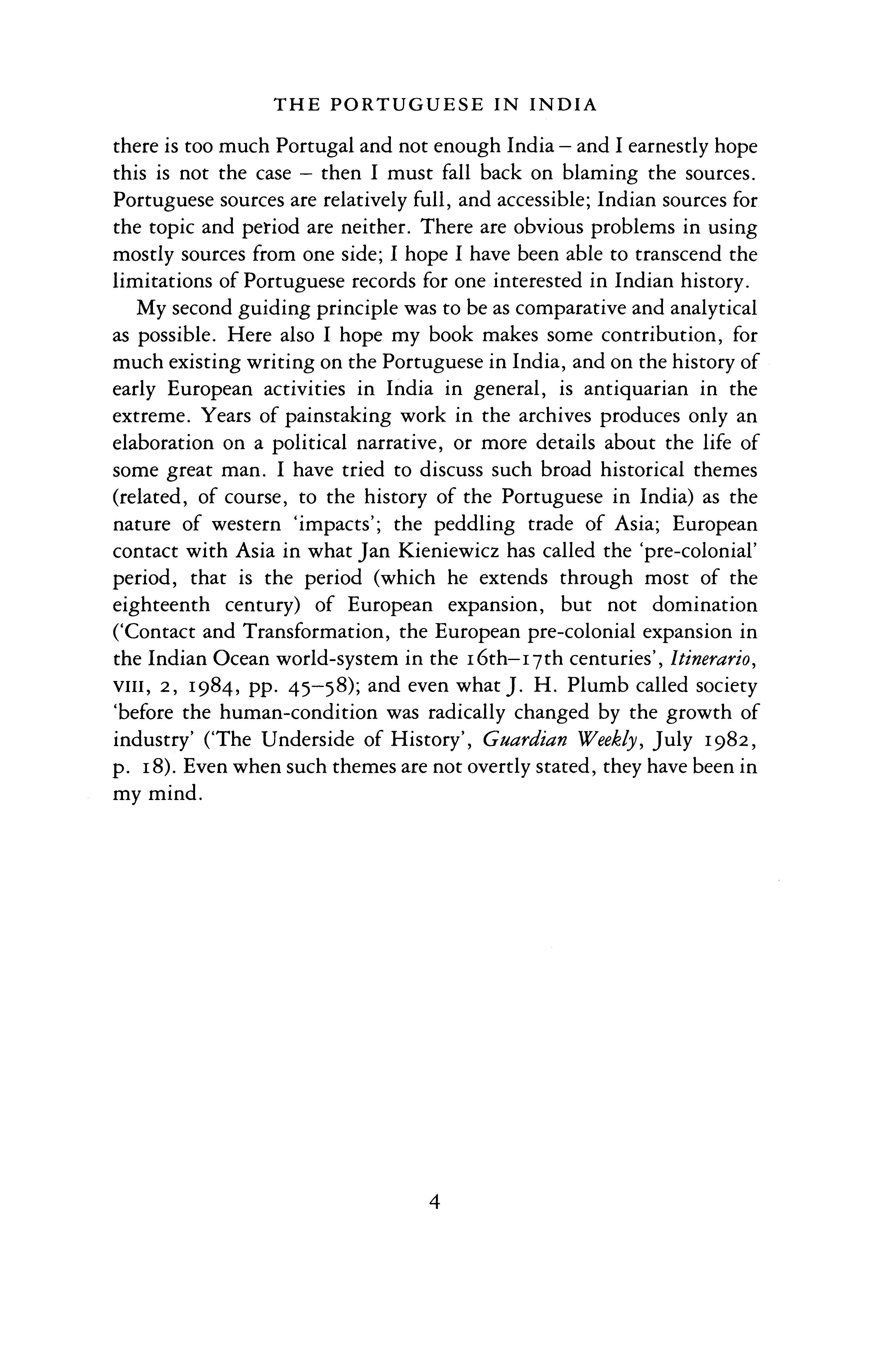

'Lahor e M U G H A L • Delhi •Agr a

E M P I R E

Ahmadabad Cambay

L Hughlil

G O LCO N D A

VI J AYANAGA R

Honavary^

BhatkalW * VIJAYAZ NAGAR

Mangalore

Cannanore

Cochin

Quilon

SaoThome

Cape Comonn I \ C E Y L O N Colombow I \ J

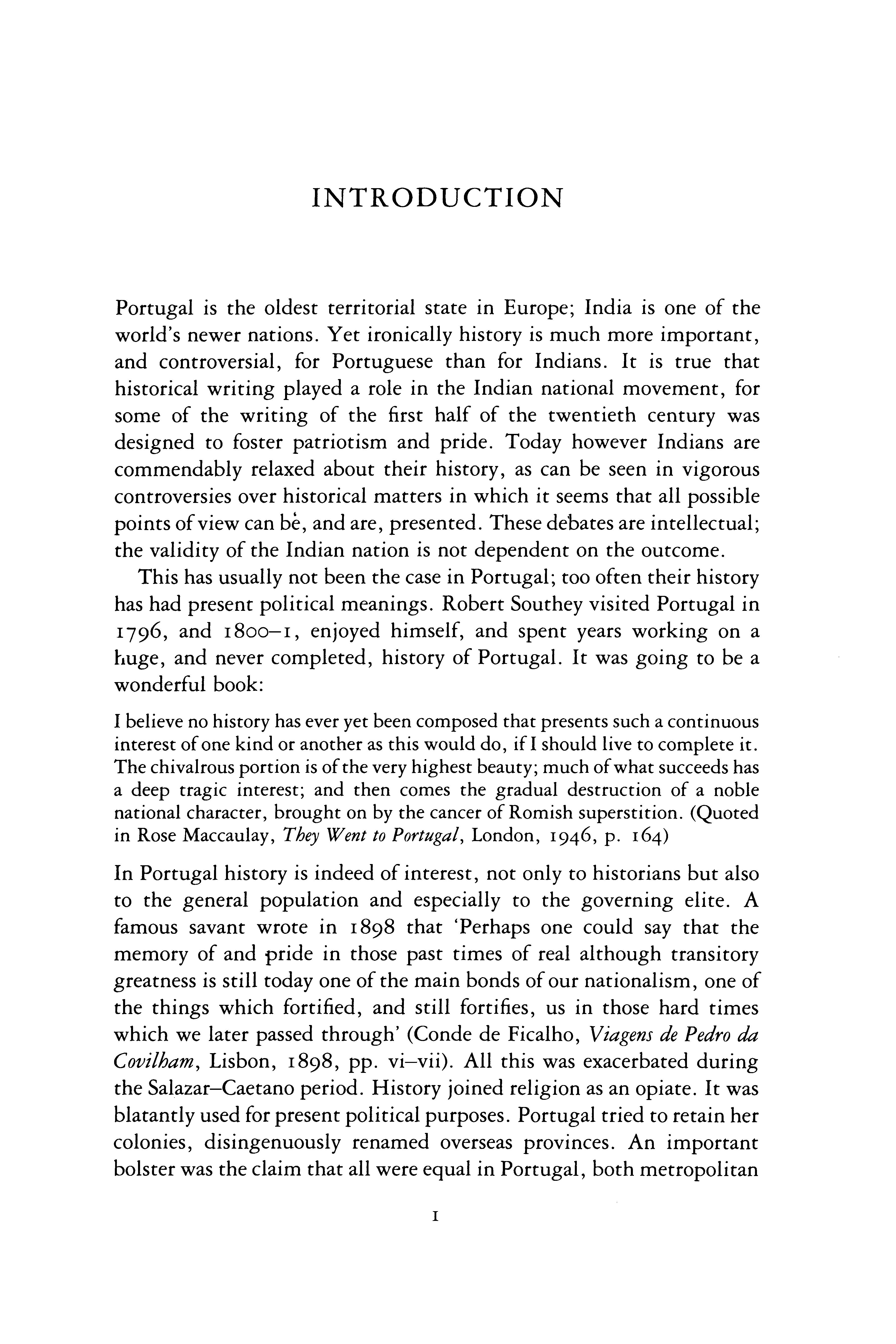

Ma p 2 Th e Portugues e and Indi a

500 km - i 30 0 miles

I L H A S

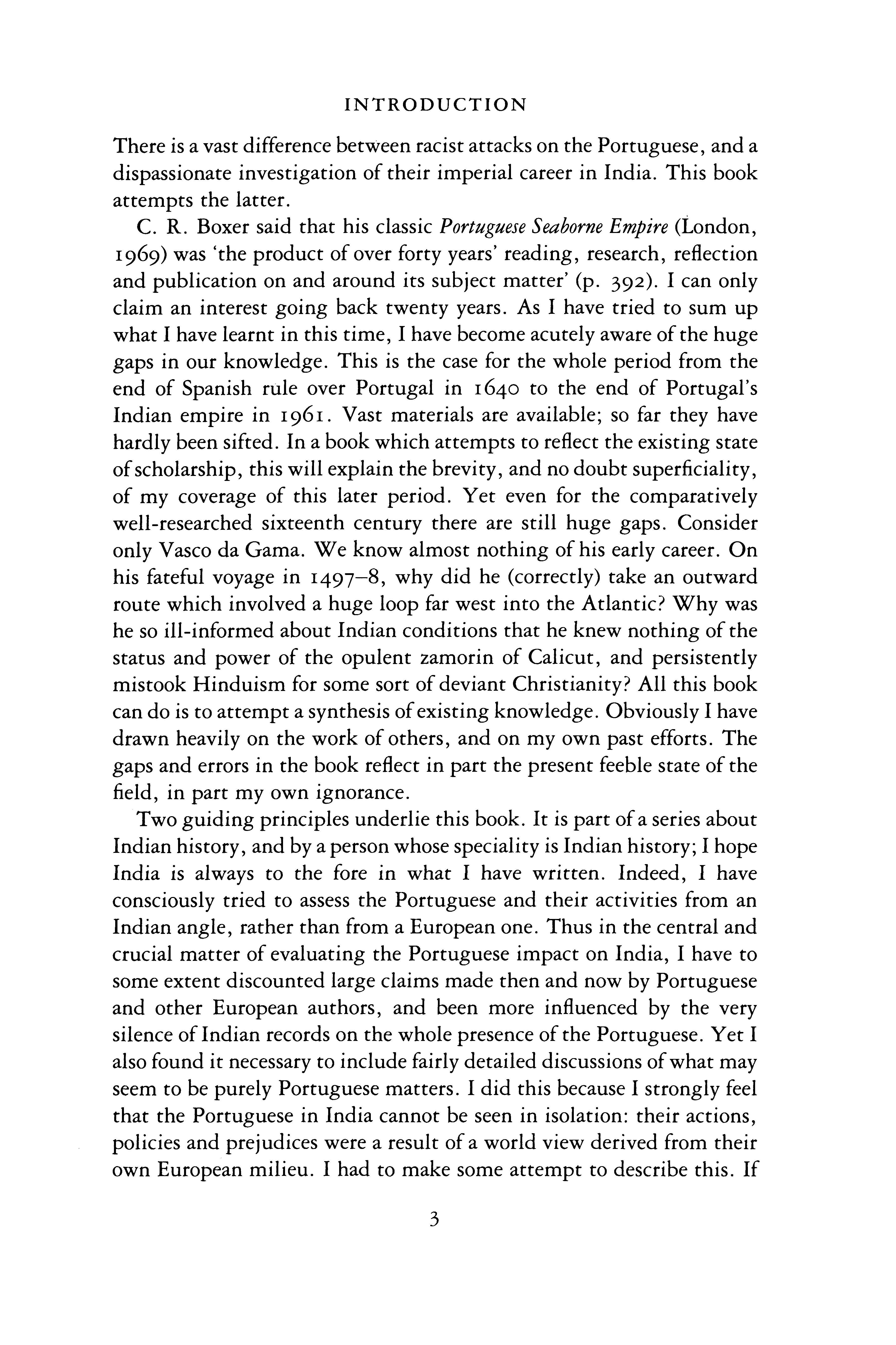

Ma p 3 . Goa

BENGA

BARDE S

INTRODUCTION

Portuga l is th e oldest territoria l stat e in Europe ; Indi a is one of th e world' s newer nations . Ye t ironically histor y is muc h mor e important , and controversial , for Portugues e tha n for Indians . I t is tru e tha t historical writin g played a role in th e India n nationa l movement , for some of th e writin g of th e first half of th e twentiet h centur y was designe d t o foster patriotis m and pride . Today however Indian s are commendabl y relaxed abou t thei r history , as can be seen in vigorous controversies over historica l matter s in whic h i t seems tha t all possible point s of view can be , and are , presented . These debate s are intellectual ; th e validit y of th e India n natio n is no t dependen t on th e outcome . Thi s has usually no t been th e case in Portugal ; too often thei r histor y has had presen t politica l meanings . Rober t Southey visite d Portuga l in 1796 , and 1800—1, enjoyed himself, and spen t years workin g on a huge , and never completed , histor y of Portugal I t was goin g t o be a wonderful book:

I believe no history has ever yet been composed that presents such a continuous interest of one kind or another as this would do, if I should live to complete it . The chivalrous portion is of the very highest beauty; much of what succeeds has a deep tragic interest; and then comes the gradual destruction of a noble national character, brought on by the cancer of Romish superstition. (Quoted in Rose Maccaulay, They Went to Portugal, London, 1946, p . 164)

I n Portuga l histor y is indeed of interest , no t only t o historian s bu t also t o th e general populatio n and especially t o th e governin g elite . A famous savant wrot e in 189 8 tha t 'Perhap s one could say tha t th e memory of and prid e in those past time s of real althoug h transitor y greatness is stil l today one of th e mai n bond s of our nationalism , one of th e thing s whic h fortified, and stil l fortifies, us in those hard time s whic h we later passed through ' (Conde de Ficalho , Viagens de Pedro da Covilham, Lisbon, 1898 , pp . vi-vii) . Al l thi s was exacerbated durin g th e Salazar-Caetan o period . Histor y joined religio n as an opiate . I t was blatantl y used for presen t politica l purposes Portuga l trie d t o retai n her colonies, disingenuousl y renamed overseas provinces . A n importan t bolste r was th e claim tha t all were equal in Portugal , bot h metropolita n

THE PORTUGUESE IN INDIA

and overseas Th e criterio n was no t race bu t degree of'civilization' I n a dictatorshi p where contro l over informatio n was give n a hig h priority , historian s were enliste d t o prove thi s claim for th e past I n a countr y lik e Portugal , small , insignificant, thank s t o D r Salazar th e poorest in Europe , histor y was used t o foster prid e and unity

Since 1974 it has been possible for Portugues e t o writ e wha t they like abou t thei r past and some have availed themselves of thi s opportunity . Ye t amon g all classes and politica l tendencies , Portugal' s pas t is stil l seen as 'important' , and usually stil l as one in whic h th e countr y can tak e pride .

Th e aim of my book is , naturally , t o assess th e influence or impac t of th e Portugues e on India . Thi s is an ambitiou s and difficult task ; i n particular , sweeping generalization s mus t be avoided. Rathe r we need , as they say, t o 'disaggregat e th e data' . Whe n thi s is done , we find Portugues e influence varying very widely , rangin g from massive t o minuscul e according t o thre e criteria : time , place and category (for example , social, religious , economic , political) . A t a particula r time , in a specified place , we may find a substantia l Portugues e impac t on a particula r category of India n life; change one or more of these criteri a (say a different tim e or place) and th e influence may well decrease t o a considerable extent .

Th e conclusion , if I may anticipat e th e centra l finding of thi s book , is tha t i n many areas th e Portugues e impac t was minor ; in a few i t was substantial . Overall ther e was muc h mor e co-operatio n and interactio n tha n dominance . Let thi s not be misunderstood . Thi s conclusion was reached on th e basis of th e evidence before me , and also, I believe, reflects an emergin g consensus amon g specialists in th e field. For those like myself who thin k in th e mos t general way tha t i t is 'wrong ' for one grou p of peopl e t o impose thei r values, thei r politica l control , on others , th e them e of thi s book wil l correctly be seen as one which is positive towards th e Portugues e imperia l effort True , thei r leaders hoped t o produc e major change in India ; mos t of th e tim e they failed, and this , even if inadvertently , mad e thei r empir e muc h less deleteriou s tha n th e later mor e complet e achievement of th e British . Needless t o say, my conclusions are in no way influenced by anti-Portugues e or anti-Catholi c feeling (whatever these tw o term s may mean) . Several Englis h author s in th e late nineteent h centur y wrot e books which criticized th e Portugues e on invalid grounds , ground s whic h showed thei r own ethnocentris m (as indeed di d Rober t Southey).

INTRODUCTION

Ther e is a vast difference between racist attack s on th e Portuguese , and a dispassionate investigatio n of thei r imperia l career in India Thi s book attempt s th e latter

C. R . Boxer said tha t his classic Portuguese Seaborne Empire (London, 1969) was 'th e produc t of over forty years' reading , research, reflection and publicatio n on and around it s subject matter ' (p . 392) . I can only claim an interes t goin g back twent y years. As I have trie d t o sum u p wha t I have learn t in thi s time , I have become acutely aware of th e hug e gaps in our knowledge . Thi s is th e case for th e whole perio d from th e end of Spanish rul e over Portuga l in 1640 t o th e end of Portugal' s India n empir e in 1961 . Vast material s are available; so far they have hardly been sifted. I n a book whic h attempt s t o reflect th e existin g stat e of scholarship , thi s wil l explain th e brevity , and no doub t superficiality, of my coverage of thi s later period . Ye t even for th e comparatively well-researched sixteent h centur y ther e are stil l hug e gaps . Consider only Vasco da Gama . W e know almos t nothin g of his early career. O n his fateful voyage i n 1497—8, why di d he (correctly) tak e an outwar d rout e whic h involved a hug e loop far west int o th e Atlantic ? Wh y was he so ill-informed abou t India n condition s tha t he knew nothin g of th e statu s and power of th e opulen t zamorin of Calicut , and persistentl y mistoo k Hinduis m for some sort of devian t Christianity ? All thi s book can do is t o attemp t a synthesis of existin g knowledge . Obviousl y I have draw n heavily on th e work of others , and on my own past efforts. Th e gaps and errors in th e book reflect in par t th e presen t feeble stat e of th e field, in par t my own ignorance .

Tw o guidin g principle s underli e thi s book I t is par t of a series abou t India n history , and by a person whose speciality is India n history ; I hope Indi a is always t o th e fore i n wha t I have written Indeed , I have consciously trie d t o assess th e Portugues e and thei r activitie s from an India n angle , rathe r tha n from a European one Thu s in th e centra l and crucial matte r of evaluatin g th e Portugues e impac t on India , I have t o some exten t discounte d large claims mad e the n and now by Portugues e and othe r European authors , and been more influenced by th e very silence of India n records on th e whole presence of th e Portuguese . Ye t I also found i t necessary t o includ e fairly detaile d discussions of wha t may seem t o be purel y Portugues e matters . I di d thi s because I strongl y feel tha t th e Portugues e in Indi a canno t be seen in isolation: thei r actions , policies and prejudices were a resul t of a world view derived from thei r own European milieu . I had t o mak e some attemp t t o describe this . If

THE PORTUGUESE IN INDIA

ther e is too muc h Portuga l and no t enoug h Indi a - and I earnestly hope thi s is no t th e case — the n I mus t fall back on blamin g th e sources Portugues e sources are relatively full, and accessible; India n sources for th e topi c and perio d are neither . Ther e are obvious problem s i n usin g mostl y sources from one side; I hope I have been able t o transcen d th e limitation s of Portugues e records for one intereste d in India n history . My second guidin g principl e was t o be as comparativ e and analytical as possible . Her e also I hope my book makes some contribution , for muc h existin g writin g on th e Portugues e in India , and on th e histor y of early European activitie s in Indi a in general , is antiquaria n in th e extreme . Years of painstakin g work in th e archives produces only an elaboratio n on a politica l narrative , or mor e detail s abou t th e life of some grea t man . I have trie d t o discuss such broad historica l theme s (related , of course, t o th e histor y of th e Portugues e i n India ) as th e natur e of western 'impacts' ; th e peddlin g trad e of Asia; European contac t wit h Asia in wha t Ja n Kieniewicz has called th e 'pre-colonial ' period , tha t is th e perio d (which he extend s throug h mos t of th e eighteent h century ) of European expansion, bu t no t dominatio n ('Contact and Transformation , th e European pre-colonial expansion in th e India n Ocean world-syste m in th e 16th—17th centuries' , Itinerario, VIII , 2 , 1984 , pp . 45-58) ; and even wha t J . H . Plum b called society 'before th e human-conditio n was radically changed by th e growt h of industry ' ('Th e Undersid e of History' , Guardian Weekly, Jul y 1982 , p . 18). Even whe n such theme s are no t overtly stated , they have been in my mind .

TH E PORTUGUES E ARRIVA L I N INDI A

Vasco da Gama' s arrival near Calicu t on 20 May 1498 was th e culminatio n of a continuous , thoug h spasmodic , Portugues e thrus t int o th e Atlantic , sout h t o th e Cape of Good Hope , and on t o India . Thi s process began in 1415 whe n th e Moroccan city of Ceut a was conquered . Th e Madeira and Azores islands were settle d by Portugues e in th e 1420s and 1430s , and in 1434 treacherous Cape Bojador was rounded . Grea t stride s were mad e in th e 1480s , culminatin g in th e roundin g of th e Cape of Good Hop e by Bartoiome u Dias in 1488 Ther e followed a brief and rathe r mysteriou s hiatus , unti l de Gama' s thre e small ships left Lisbon in Jul y 1497 . After spendin g May t o Octobe r 1498 off th e southwes t India n coast, he returne d t o Portuga l in Augus t 1499 ; no t surprisingly , he was welcomed ecstatically.

Th e king , D . Manuel (1495—1521), immediatel y undertoo k extensive publi c works in Lisbon, designed t o foster trad e and future expeditions Preparation s for th e second expedition , commande d by Cabral , were accelerated: he left in March 1500 wit h a hug e fleet of thirtee n ships and at least 1200 men . Th e sense of confidence and exultatio n of th e tim e can be seen in th e way work was starte d late in 1499 on th e hug e monastery of th e Jeronimo s in th e subur b of Lisbon on th e Tagu s River from whic h th e fleets left for India . Even more indicativ e was th e renamin g of th e area where th e monaster y was t o be erected (i t took fifty years t o complete) : i t was t o be know n henceforth as Belem (Bethlehem) , th e place where th e Portugues e empir e was born

Historian s have lon g debate d th e reasons for these voyages Wh y was almost a centur y spen t on thrustin g down th e Wes t African coast, and why was it th e Portugues e rathe r tha n some othe r European power who undertoo k these voyages? Th e much-quote d answer tells us tha t a membe r of da Gama' s crew, when asked in Calicu t 'Wha t brough t you here? ' replied 'W e seek Christian s and Spices. ' Such a reply was actually a cliche even in th e fifteenth century ; Portugues e king s in thei r letter s explained not only th e discoveries bu t almos t everythin g else they di d as bein g designed t o 'serve Go d and mak e a profit for ourselves' . Some later Portugues e explanations , flying even further in th e face of bot h facts and

THE PORTUGUESE IN INDIA

probability , stress solely religious motives . Portugal' s greates t poet Luis de Camoens in The Lusiads, Portugal' s nationa l epic , has a Portugues e reply t o th e questio n posed above: 'W e have come across th e might y deep , where none has ever sailed before us , in search of th e Indus . Ou r purpos e is t o spread th e Christia n faith' (Willia m C. Atkinson , trans. , The Lusiads, Penguin , 1952 , p . 166). An official Portugues e publicatio n issued in 1956 , when thei r rule in Goa was gravely threatened , claimed tha t 'Commercia l exploitatio n has never been th e mainsprin g of Portugues e actio n overseas Always religious in character , Portugues e expansion was yet no t guide d by a narrow proselytizin g spirit , bu t by a spiri t of gradua l and toleran t assimilation.' 1

Histor y writin g always reflects prevailin g needs and moods . Consequently , in th e period between 1955 and 1985 th e Portugues e discoveries have often been explained in almos t purel y economic terms Several thing s d o seem t o be clear. I n th e early fifteenth centur y Portugues e expansion was in large par t a search for food, for Portuga l was always a grai n importer . Henc e th e settlemen t of th e Azores and Madeira , and th e rapid expansion of cereal and sugar productio n there . Henc e also large-scale grai n productio n in th e Portugues e enclaves i n Nort h Africa Th e search for new fishing grounds , when successful, especially in th e nort h Atlantic , provide d not only protei n bu t also maritim e training . Bu t politica l imperative s also played a part . I n Portugal , as elsewhere in Europe , seigneuria l revenues were falling , and one escape from th e 'crisis of feudalism' was t o provid e alternativ e outlet s for bastards , younger sons, and othe r disadvantage d nobles . Such people received land on feudal term s in th e Atlanti c islands , and could gai n glory , even knighthoods , rightin g on th e Nort h African frontier.

Onc e started , th e expansion fed on itself. As trad e developed gol d was needed; from th e 1450s i t came back i n considerable quantitie s from Wes t Africa. As sugar productio n expanded labour was needed; Wes t Africa turne d ou t t o be a prim e source of slaves and these flooded int o th e islands and metropolita n Portuga l after 1443 But , ironically , one produc t no t in short suppl y was spices, whic h of course became th e leit-motif of the sixteenth-centur y empire . Unti l th e 1470s ther e was no ques t for Asian spices, for fifteenth-century Europe was well provide d

1 Portuguese India Today, 2n d ed (Lisbon , 1956) , pp 31—2

TH E PORTUGUES E ARRIVAL I N INDI A

for by th e traditiona l rout e throug h th e Red Sea, t o Alexandria and so t o Venice

Th e role of different social group s in Portuga l in thi s expansion has been muc h debated . Ther e is evidence, thoug h thi s is a matte r in dispute , tha t th e rise of th e Ottoma n Turk s in th e eastern Mediterranean in th e fifteenth centur y blocked some traditiona l Genoese investmen t areas. To compensate , grea t Genoese bankers turne d t o Portugal , and thei r investment s provide d some of th e impetu s and capita l needed t o finance th e discoveries. Th e role of th e peasantry is also controversial . Some historian s have pointe d t o a populatio n increase in th e fifteenth centur y t o compensat e for th e ravages of th e Black Death ; th e expansion overseas was the n necessary t o provid e a safety-valve. Thi s however seems less convincing . Fifteenth-centur y Portuga l was certainl y a small and ppor country , yet wit h a populatio n of less tha n one millio n any surplu s rural populatio n was easily absorbed in th e towns . I t does seem clear tha t thi s urba n migratio n weakened further th e power of th e nobles on thei r lande d estates . Th e nobilit y in fact suffered no t only from a labour shortag e bu t also from a comparativel y disadvantageous positio n vis-a-vis th e monarchy , th e Hous e of Aviz whic h ruled Portuga l from 1385 t o 1580 . Thi s royal domination , whic h in par t reflected changin g economic and social forces in Portuga l itself, was also a resul t of events in 1385 . In thi s year th e Portugues e kin g beat off a Castilian attack , so establishin g his new dynasty . Most of his nobles had sided wit h th e foreigners, and were eithe r executed or exiled for thei r bad choice. Th e Portugues e nobilit y were thu s facing crises bot h in thei r position s in th e countrysid e and in thei r unusua l subservience t o th e monarchy Th e latte r was forcefully brough t hom e t o the m in 1484 , when an over-might y noble , in fact th e to p noble , th e Duk e of Braganga, was executed for treason Expansion , new lands and new path s t o glor y had an obvious , even if atavistic , appeal

Th e role of th e crown is similarly a matte r of debat e and controversy

Th e imag e of Princ e Henr y th e Navigato r has lon g dominated A younger son of D Joa o I (1385-1433) , and knighte d at Ceuta , he devoted his life, we are told , t o th e discoveries as a crusade t o outflank th e Muslims . In th e fastnesses of Sagres, in th e extrem e southwes t of th e country , he established a school for mariner s and navigators , and sent ou t expeditio n after expeditio n dow n th e Wes t African coast, following thei r progress wit h weary eyes unti l th e Cross of Chris t on thei r sails sank below th e horizon . Recent research has modified thi s picture . Th e

THE PORTUGUESE IN INDIA

princ e was no t particularl y learned , and th e notio n of his establishin g a 'school' for navigators and scientist s seems quit e far-fetched Bu t he played a role nevertheless. Like othe r member s of th e royal family he had large estates and othe r economic interest s in Portuga l (among othe r things , he held a monopoly on soap making) . Whil e ther e may have been a religiou s or mystical elemen t in his patronag e of voyages of discovery, he also profited handsomely from th e results , especially from import s of gol d and slaves. Her e also i t seems economic ma n was dominant , even if not exclusively. Further , Prince Henry' s activities , whatever thei r motives , d o poin t t o one centra l characteristi c of th e discoveries, namely th e centra l role played by th e crown . I t is tru e tha t merchants , bot h Portugues e and foreign, often provided capita l and even ships , yet th e directio n and muc h of th e impetu s came from th e crown . Thi s directio n was particularl y importan t after th e deat h of Prince Henr y i n 1460 . I t is possible t o envisage th e Portugues e standin g pa t aroun d thi s time . Th e Atlanti c islands were producing , a debased chivalry could perform it s barbarous ritual s in Nort h Africa, and trad e wit h Wes t Africa was flourishing. Th e souther n end of Africa seemed nowhere in sight . I t was only a new royal push , thi s tim e from th e future Joa o II (1481—95), whic h led t o further progress southwards . Th e way in whic h thi s was don e encapsulated exactly th e whole merchant—king nexus whic h produce d th e discoveries. I n 1469 after some years of stalemat e a merchan t was give n a wide-rangin g concession . I n retur n for a five-year monopoly on th e trad e in gol d and slaves, he had t o discover 100 leagues of Wes t African coast a year. Thu s were linke d th e merchant' s search for profits, and th e crown's desire , at least partl y also wit h a view t o profits, for further discoveries.

Historian s have pointe d t o various othe r subsidiary element s t o explain th e progress and success of Portugues e discoveries. Th e country' s location in th e extrem e southwes t of Europe may have provided , by reason of greate r contiguity , some small advantage . Portuga l was at peace throug h nearly all th e fifteenth century ; energy could be channelled towards expansion. As in many othe r part s of Europe , th e idea of discovery and foreign travel had some popula r currency , fostered by Marco Polo's book and Sir Joh n Mandeville's extremely popular , thoug h bogus , Travels. Some Portugues e had behin d the m a traditio n of seafaring, derived from th e importanc e of fishing along th e coast and indeed far ou t int o th e nort h Atlantic