Urban Planning for Transitions

Edited by

Nicolas Douay

Michael Minja

First published 2021 in Great Britain and the United States by ISTE Ltd and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms and licenses issued by the CLA. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms should be sent to the publishers at the undermentioned address:

ISTE Ltd

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

27-37 St George’s Road 111 River Street London SW19 4EU Hoboken, NJ 07030 UK USA

www.iste.co.uk

www.wiley.com

© ISTE Ltd 2021

The rights of Nicolas Douay and Michael Minja to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950533

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78630-675-3

3.1.

3.2.

3.2.1.

3.2.2.

3.3.

4.1.

4.2.

5.1.

5.2.

5.2.1.

5.3.

5.4.

5.6.

6.1.

6.2. Background: the Car-free Livability Programme of

6.3. The role of the Car-free Livability Programme and specific developments brought by it .............................

6.3.1. Advocating city life at the expense of parking space

6.3.2. Exploratory urban development projects

6.3.3. New pedestrian streets and pedestrian-friendly urban

6.3.4. The city center planning model for the future streets

6.4. Car-free city centers are not utopian models

6.5.

6.6.

Bérénice JOURNET

7.1.

7.2.

7.3.

7.4.

7.6.

Esraa ELESAWY

8.1.

8.2.

8.3. The bicycle city plan: making the city

8.3.4.

8.4.

Chapter 9. Smart and Digital City Action Plan, Montreal ........

Daniel Carl NUNOO

9.1. Introduction

9.2. Context

9.3. Montreal’s

9.3.1.

9.3.2.

9.3.3.

Chapter 10. A Smart City Masterplan, Kigali

Haley BURNS

10.1.

Chapter 11. The Array of Things, Chicago ..................

Leonardo

RICAURTE

11.1.

12.1.

12.2. 22@Barcelona

12.3.

12.4.

12.5.

12.6.

Introduction

David Eversley, the author of “The Planner in Society: The Changing Role of a Profession”, described how urban planners might be at a crossroads and they had a choice of paths to take. Eversley writes:

Straight ahead, perhaps, he (sic) can plod on with what he has been doing, and probably doing conscientiously enough: administering the law of the land. To one side: an abyss, a total disgrace, an abdication from social responsibility, the planner at the bottom of the heap and the scapegoat for all the evils of society. But in other directions, the road points to the possibility that the planner may be on the brink of greatness: a long, hard climb, not to a height where his judgment is unassailable and not so far removed from the realities of the urban scene that he need no longer communicate (Eversley 1973, p. 304).

Although the study he conducted focused on British town and city planning back then, it certainly addressed urban planners all over the world and through time. Indeed, Eversley presented this crossroads in a specific moment of debate in the urban planning history.

After dominating the practice and the theory for several decades, the traditional model of spatial planning, based on rationality, was gradually called into question from the end of the 1960s onwards. We then observed important changes in urban planning practices. It was less about a succession

Introduction written by Nicolas DOUAY and Michael MINJA.

of paradigmatic ruptures than a gradual and concomitant evolution (Allmendinger 2002; Douay 2013).

In a context of neo-liberalism from the 1980s onwards, the contribution of the strategic current is above all the search for greater efficiency (Salet and Faludi 2000). Urban project became the catalyst, in order to bring together public and also private actors in their pluralities with the objective of coordinating the different forms of resources and legitimacies to ensure planning implementation and effective policies.

In addition, from the 1990s, the communication or collaborative current began to emerge. Judith Innes puts forward the idea that planning is first defined by communication (Innes 1998). In the same perspective, Patsy Healey put forward the idea that the primary mission of the planning actors is the communication with other participants in public policy processes:

(1) all forms of knowledge are socially constructed; (2) knowledge and reasoning may take many different forms, including storytelling and subjective statements; (3) individuals develop their views through social interaction; (4) people have diverse interests and expectations and these are social and symbolic as well as material; (5) public policy needs to draw upon and make widely available a broad range of knowledge and reasoning drawn from different sources (Healey 1997, p. 29).

Today, as the world undergoes rapid and dynamic transformations, riddled with uncertainties of the future, the role of urban planners has never been more important. So, we can make the hypothesis that urban planning and urban planners are in one of these new moments of crossroads. Climate change, urban migration, financial and economic crises have elevated urbanization to newer heights of complexity. They have also turned and revealed that urbanization is a multi-scalar process that needs to be tackled by integrating a multitude of scenarios, strategies and discourses in order to create an urban ecosystem that is resilient and efficient.

Emphasis should be placed in attaining a “system of cities” rather than focusing on an individual city or individual parameters in the city. In doing so, this will undermine the traditional perception that looked at cities as separate entities from nature and the countryside. Instead, cities will be perceived as reciprocal parts of regional ecosystems and dynamic landscapes

obtained out of social and ecological processes from ecosystems all around the world.

As mentioned, contemporary urbanization is riddled with uncertainty, especially with what is currently going on with regard to climate change, migration and economic crises. That is, planners have a very significant role in the process of either creating sustainable and pristine urban spaces or contributing to the creation of urban spaces that are vulnerable and prone to social, political, economic or ecological complexities.

There is uncertainty and doubtfulness on how these constraints will be addressed with planning theories, policies or strategies. H. Ernston et al. (2010) explained that these uncertainties need to be faced with experimentation, learning and innovation. Urban innovation will eventually allow for more exploration and implementation of various innovation strategies to extreme levels.

Following this brief introduction, the next chapters of the paper will present and concisely discuss various urban transition strategies, action plans and programs that have been proposed or even been conducted in different countries all over the world, as each of them tries to address the urban complexities and also cope with the rapid pace at which the world is evolving. Urban planners have come up with transition proposals and concepts that they hope will be able to respond to the cities’ challenges and ultimately allow the cities to adapt and transition to more robust urban areas.

The transition strategies presented herewith have been presented, written and discussed as part of an introductory course on urban planning in the master’s program International Cooperation in Urban Planning at the Université Grenoble Alpes (IUGA).The main objective was to build on the diversity of students’ personal experiences and knowledge of international planning practices. The different chapters, therefore, are sorted into the following groups:

(i) strategic planning and resilience transition: Rotterdam Resilience Strategy, Rotterdam (Chapter 1); Sustainable Florianópolis Action Plan, Santa Catarina (Chapter 2); “Recife 500 Anos” Plan, Recife (Chapter 3);

(ii) green transitions: Greenest City 2020, Vancouver (Chapter 4); The Grandeur Nature Plan, Eurométropole of Strasbourg (Chapter 5);

(iii) mobility transitions: The Car-free Livability Programme, Oslo (Chapter 6); A Carbon-free City, Uppsala (Chapter 7); The Bicycle Strategy 2011–2025, Copenhagen (Chapter 8);

(iv) digital transitions: Smart and Digital City Action Plan, Montreal (Chapter 9); A Smart City Masterplan, Kigali (Chapter 10); The Array of Things, Chicago (Chapter 11); 22@Barcelona Project, Barcelona (Chapter 12).

These policies and strategies will eventually allow cities to become more efficient “systems”, allowing them to effectively navigate through change, build capacity to withstand shock (such as natural calamities) and use experimentation and innovation ways to face uncertainty, hence adaptive, resilient and robust cities and urban spaces.

Rotterdam Resilience Strategy, Rotterdam

1.1.

Introduction

Rotterdam is facing several challenges including climate change and notable urbanization and digitalization, which have not only brought new opportunities but also brought new risks. Since 80% of its urban area is below sea level, water management has always been vital on the resilience agenda in Rotterdam. With the intensification of urbanization processes, permeable areas to manage stormwater drainage are diminishing. At the same time, climate change only adds to the problem, raising the probability of storms and floods and thus forcing the city to rapidly adapt into more resilient actions and strategies.

On May 2016, the city of Rotterdam launched its very first resilience strategy to make the city resilient and ready for the challenges of the 21st century. To reproduce the current framework where Rotterdam is towards resilience, this chapter will briefly look into the 2016 resilient strategy and also have a brief glimpse on the history of the evolution of the urban policies on sustainable adaptations in Rotterdam.

1.2. Context and background

Chapter written by Munir KHADER

Urban planning strategy

Project scale

Strategy type

Strategy origin

Responsible administrative authority

Rotterdam Resilience Strategy: Ready for the 21st Century

Entire city (325.79 km2)

Social cohesion and education, Energy, Climate adaptation, Cyber, Vital infrastructure, Governance

– The Instrument of Water Assessment (2000)

– Climate Change Plan (2008)

– National Spatial Strategy

– The Rotterdam Climate Adaptation strategy (2013)

The Municipality of Rotterdam + other stakeholders depend on goals and actions

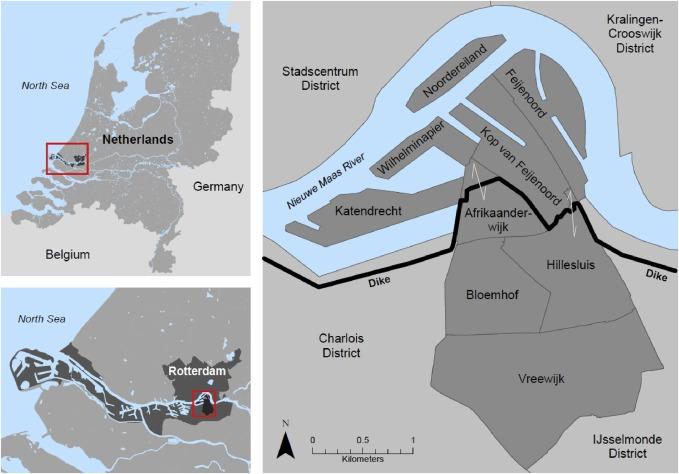

The city of Rotterdam is a thriving world port city; it is the second largest Dutch city after the capital Amsterdam and currently has a population of more than 644,688 inhabitants (2020, Statistica website). It is located in the province of South Holland, in a delta region near the North Sea, as Map 1.1 shows. Rotterdam is considered one of the main gateways to overseas trade in Europe and an industrial and technological hub of the Netherlands.

Table 1.1. Introductive summary table of Rotterdam Resilience Strategy

Map 1.1. Location of Rotterdam city (source: Time map website)

Resilience Strategy, Rotterdam 3

The Netherlands was one of the first countries to commit to the sustainability transition discourse in its public networks. In 2000, the government developed the instrument of Water Assessment for implementation in all spatial plans and spatial decisions relevant to water, sequentially becoming mandatory for zoning plans and project decisions.

However, this first plan embraced water management, but it did not have any integration with other urban complexities. The 2008 plan was complemented with initial measures that addressed climate change and, since then, water management has been incorporated in the National Spatial Strategy. This national strategy contributed to the Rotterdam Climate Initiative (RCI), launched in 2013, which aimed to “reduce CO2 emissions by 50% and to have made the region 100% climate proof by 2025”. This made Rotterdam one of the global pioneers in urban climate adaptation.

The city of Rotterdam released its Resilience strategy on April 2016 with a vision towards 2030. The strategy will strive to bring the city onto the next level of climate readiness. In fact, the implementation of this climate adaptation strategy had already started with the 2013 strategy and managed to fulfill a number of the objectives, hence exposing the plan’s ability to initiate change.

1.3. Rotterdam Resilience Strategy – Ready for the 21st Century

1.3.1.

Methodology

The city formulated a clear methodology to define its resilience strategy and vision. The city’s suggestions came after considering the site analysis and the challenges that faced the city. They ended up formulating an integrated vision that would include all the stakeholders and also address the stakeholders’ requirements. To be able to do so, a number of steps will be compulsory. The strategy referred to the infamous 100 Resilience Cities program, which had already laid out the necessary steps and methodology to create and achieve resilient cities. These steps are outlined below (source: Rotterdam Resilience Strategy):

i) An assessment of the current situation and defining the city’s challenges: using a list of the main fields of activity in the city in which it

includes 12 aspects, that should be covered by the resilience strategy. These aspects are categorized in four sections, which are:

– health and well-being;

– economy and society;

– infrastructure and environment;

– leadership and strategy.

ii) Review the main transitions in development:

– the economy of the 21st Century (“next economy”): simultaneous transitions from fossil fuels to renewable forms of energy, from analogue to digital and from a linear extractive economic model to a circular sustainable model;

– climate change: rising sea levels, unpredictable river flow volumes, more frequent and more intense rainfall, subsidence and heat stress;

– digitization: exponential rate of technological progress and development, characterized by the Internet of Things, Smart City and Big Data. Despite it presenting plenty of opportunities, it also increased the levels of dependency and vulnerability in the field of security and privacy;

– new democracy: individualization, an increase in self-organization, assertive citizens and consumers, better information, new roles for government and utility services, as well as the emergence of the “ prosumers” (people who are simultaneously consumers and producers);

– unknown developments: the ultimate form of resilience needs to deal with unexpected development or changes that might happen and turn out quite differently to what was anticipated.

iii) Defining action areas: based on the analysis and the city challenges, the city decided to formulate its vision and goals around four main areas: citizens, infrastructure, governance and economy.

iv) Defining the resilience lens: based on the seven qualities of resilience, that is: reflective, resourceful, robust, redundant, flexible, inclusive and integrated.

v) Defining focus areas: based on the city’s challenges, which are: social cohesion and education; energy transition; climate adaptation; cyber use and security; critical infrastructure; changing urban governance (changes in

Rotterdam Resilience Strategy, Rotterdam 5

society and democracy, driven by moving away from the top–down hierarchy to a more bottom–up approach with much greater levels of community and citizen involvement); a changing economy that is driven more by sharing and technological innovation “Next Economy” .

vi) Define the resilience goals: based on the city analysis (12 aspects);

vii) Define actions and related actions: connected to the vision and objective of each goal.

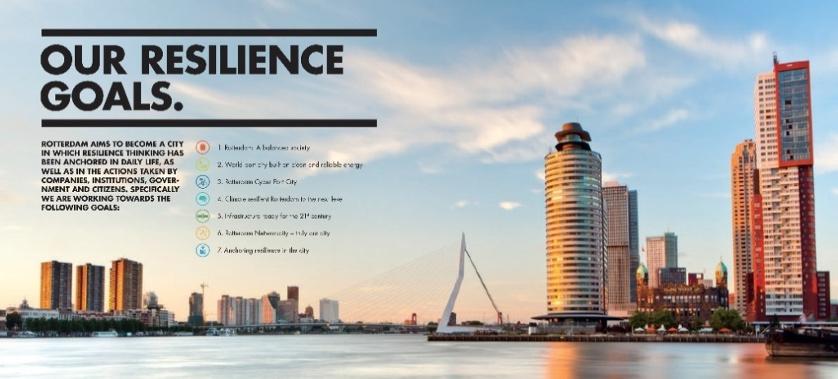

1.3.2. Rotterdam Resilience Strategy – Goals, stakeholders

The Resilience Strategy 2030 adopted by the city of Rotterdam includes seven goals with reference from the resilience qualities: (i) Rotterdam: a balanced society; (ii) World Port City built on clean and reliable energy; (iii) Rotterdam Cyber Port City; (iv) Climate Adaptive city to a new level; (v) infrastructure ready to face the 21st century; (vi) Rotterdam network city; and (vii) anchoring resilience in the city.

Figure 1.1. Resilience goals of Rotterdam Brochure. (Source: Rotterdam Resilience Strategy 2016). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/douay/transitions.zip

The city of Rotterdam managed to launch the resilience strategy by featuring good public participation and the involvement of different stakeholders such as the Rotterdam residents, public and private organizations, businesses and knowledge institutions in the decision-making process. Table 1.2 presents a summary of most of the stakeholders that participated in the process of coming up with the Resilience Strategy 2030.

– The International Water Exchange, powered by the Rockefeller Foundation

– 100 Resilient Cities

– Rotterdam Centre for Resilient Delta Cities

– URBACT: Resilient Europe program

– Cities experience and exchange with: Antwerp, Bristol, Burgas, Glasgow, Katowice, Malmo, Potenza, Rome, Thessaloniki, Vejle and the EU

Besides, 8 (platform) partners including knowledge institutes such as: Microsoft, AECOM, TNO, Drift, Resilient Delta Cities (RDC), Urbanisten, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam and DELTARES.

Table 1.2. Stakeholders and actors (source: Rotterdam Resilience Strategy)

Following this, Rotterdam took a comprehensive approach on the city’s efforts for resilience, targeting a holistic way to face challenges in smaller scales. All the goals scheduled to be acted upon by the different stakeholders were described in each section. It also included a description of the financing methods or feasibility; the current status of development or implementation; the categorization of the response – as short, medium or long term; and the owner and the level of impact, in the scale of an individual, district or the city.

GOAL 1: Rotterdam: a balanced society: “Skilled and healthy citizens in a balanced society”

To build and strengthen resilience at the individual and societal levels, by supporting knowledge, skills, education, health, well-being, as well as mutual understanding and respect as central pillars of a balanced society.

GOAL 2: World Port City built on clean and reliable energy: “Towards a flexible energy infrastructure for an efficient and sustainable energy mix in Port and City”

Providing a clean diversification of energy sources and making the urban energy infrastructure would be a complex task; however, it provides the opportunity for Rotterdam to strengthen its economy and reputation, as well as it makes the city more flexible for the future.

GOAL 3: Rotterdam Cyber Port City: “Rotterdam aims to be a cyber resilient city and port, an important condition required to attract new business and investment” The resilience of Rotterdam to cyber threats will be increased by enhancing awareness, sharing knowledge and experience, and joining forces to improve responsiveness and ICT products.

Rotterdam Resilience Strategy, Rotterdam 7

GOAL 4: Climate Adaptive city to a new level: “Climate proof plus cyber proof critical infrastructure”

The city of Rotterdam will work to better understand the cascading impacts of climate change and to factor these into their cost–benefit decision-making. Furthermore, they will also strengthen their crisis management approaches based on increased knowledge of flood risks, as well as enhancing their climate resilience strategy by taking action on cyber resilience.

GOAL 5: Infrastructure ready for the 21st Century: “A robust and resilient underground infrastructure as a physical basis for a resilient Rotterdam”

Rotterdam wants to increase resilience by enhancing the awareness of risk, developing a policy for more robust decision-making; more integrated planning practice both underground and over-ground, relating to infrastructural interventions.

GOAL 6: Rotterdam network – Truly our city: “Residents, public and private organizations, businesses and knowledge institutions together determine the resilience of the city”

The resilience strategy will focus on increasing government flexibility and will facilitate connecting several networks of locals, individuals and businesses, as a catalyst for more bottom–up community and initiatives, to share knowledge and experiences to the advantage of Rotterdam’s people and prosperity.

GOAL 7: Anchoring resilience in the city: “With stakeholders in the neighborhoods, sharing knowledge and a facilitating organization”

The city will develop an innovative and integrative agenda on the back of this resilience strategy to identify co-benefits and synergies.

This Resilience Strategy adopted by the city has managed to cover different scales, starting from the smallest one that is buildings and people to the world-wide scale through connecting with and recognizing other cities with global resilience strategies. Therefore, the strategy managed to focus and reasonably integrate the following key aspects.

1.3.3. Concrete resilient initiatives and programs

The strategy has adopted different programs and initiatives that made it distinctive, creative and applicable as well. The following ideas present how the strategy has succeeded in being creative in dealing with city’s threats and

Table 1.3. Rotterdam Resilience Goals (source: Rotterdam Resilience Strategy 2016)

how they formulated their weaknesses into opportunities (the following programs and initiatives are based on personal preferences):

i) WEsociety program

The role of Rotterdam’s WEsociety program is that there is a place for everyone, and everyone has the same opportunity to participate in the city’s action plans as well. The stakeholders tend to make Rotterdam a place where people actively want to meet one another and demonstrate their understanding and respect to each other. Mutual dialogue and connection enable and facilitates the discussion of any perceived issues.

The WEsociety program was initiated to make Rotterdam more resilient and resistant to potential harmful influences. It aims to strengthen connectedness in a sustainable way and create space for citizens to express issues and misgivings. Besides, Rotterdam is working also on expanding and strengthening the interconnectedness of the city among city dwellers, social organizations, population groups with different cultural backgrounds and with the municipal government as well. This will help the city to achieve the following different social qualities:

– integration: accept and understand each other’s value and take action to reduce tensions;

– participation: provide same opportunities to different population groups;

– capacity for adaptation: through the cultural diversity of Rotterdam’s population;

– resourcefulness and robustness: become strong and assertive to avoid the potentially negative consequences of world events;

– redundancy: get benefits of the communication channels among local population to support actions during crisis;

– flexibility: society can accommodate population groups that are facing difficulties.

For individuals, a resilient society means that everyone, regardless of their cultural, ethnic or religious backgrounds, is valued and respected and can participate – somehow – in the society (participation). Furthermore,

Rotterdam Resilience Strategy, Rotterdam 9

differences and diversity will always be there, but mutual respect and understanding should always be observed (integration).

Scale The whole city

Owner/partner The Municipality of Rotterdam/welfare organizations

Status On going

Result Short-term/medium-term

Related actions 6, 7, 8, 9 (see Appendix 2 of strategy)

Table 1.4. WEsociety Program (source: Rotterdam Resilience Strategy 2016)

ii) The Rotterdam Energy Infrastructure Plan (REIP)

The transition to efficient and renewable energy will require – in addition to measures at the level of individual buildings – an energy infrastructure that can support this transition and proposals on how this transition can be implemented and overseen (a road map).

This would be an important step towards a 100% CO2-free built environment by 2050. To do so, the municipality has decided to start this process by using the Rotterdam Energy Infrastructure Plan (REIP). It seeks to respond to the strong and ambitious endeavors of the city such as solar energy and wind energy, by finding the means for the needed transition. As the existing infrastructure and facilities are based on outdated ideas in relation to the supply of energy and do not incorporate the concepts of emissions reduction and the finite extent of the earth’s (fossil) resources, it is a good idea to come up with state-of-the-art approaches.

The REIP represents such an intermediate stage (between the ambition and implementation stage) to provide a better understanding of the ultimate goal, the implementation strategy and the relevant parameters. The challenge that exists is to ensure that the city’s energy management systems remain flexible, integrated and yet robust, as the combination of energy storage and smart grids will play a key role.

The REIP will need to deliver the following intermediate results:

– energy mix: what is possible in terms of Rotterdam’s energy supply (and demand)? This includes plans relating to the heat node and developments in the port area;

– infrastructure plan: what do the Rotterdammers need to do and where? The city is seeking to understand the optimum combination of energy solutions at the local level and the urban energy infrastructure that would be needed for this. This subproject focuses on the built environment of the city of Rotterdam;

– road map: how does Rotterdam get there? The road map provides an insight into who needs to do what and which requirements need to be met in order to make progress towards the energy transition.

The REIP approach involves a closer examination of which best combination of top–down and bottom–up measures will work the most effectively (including research into which combination of push and pull measures are required).

iii) Smart cities and climate proof

Rotterdam has approximately 50 km of industrial port, mostly fossil fuelbased, targeted to be transformed in a more sustainable port since the climate adaptation strategy in 2013. The city aims to be among the front-runners of the energy efficiency adaptation in the resilience strategy, supporting recent political agreements through the COP21 agreement in Paris. The French program is accelerating transitions in Rotterdam, as efforts are undergoing to provide cost-effective solar panels in small and large solar parks, as well as switching a large portion of the municipal vehicles to more energy-efficient ones. Also, the renewable energy infrastructure plan (REIP), which is currently under development, will focus on renewable energy and energy conservation in the Smart City Delta.

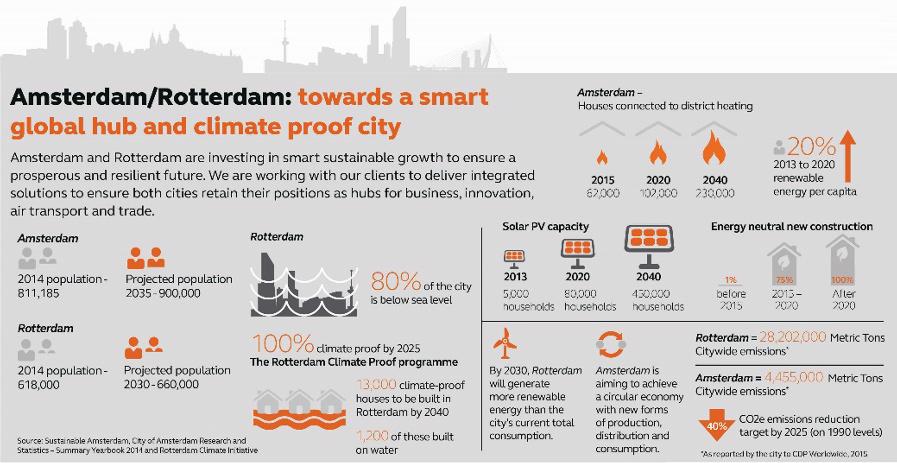

An analysis made by Arcadis included the Resilience Strategy and also made a comparison between Rotterdam and Amsterdam. It showed that statistically, after the implementation of the resilience strategy, there will be huge changes in Rotterdam in comparison to Amsterdam, as both cities strive towards achieving a more resilient environment.

Figure 1.2. Rotterdam and Amsterdam smart cities and climate proof consultancy (source: Arcadis Company 2014). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/douay/transitions.zip

iv) Adaptive waterfront development

An opportunity to respond to the risk of floods in an integrated and inclusive approach; in other words, building resilience by design. The Rotterdam region explored, with multiple stakeholders, the future perspective of the “River as a Tidal Park”. The idea includes building with nature: new eco-habitants, reuse of sediments, wave reduction, better water quality, turning stony embankments into a more natural landscape and creating a foreland or title park. The funding was possible due to the port authorities and multiple stakeholders who were involved and willing to contribute to the reuse of sediments from the port, for example.

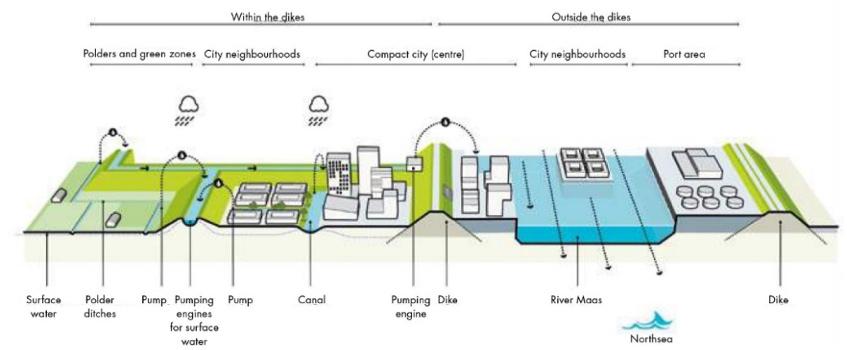

Feijenoord district, as shown in Map 1.2, is considered, on the one hand, a developing urban area. On the other hand, it is an area considered highly vulnerable to flooding from the river. As a solution, the city of Rotterdam found that it is essential to work with all partners (developers and stakeholders) to understand the level of flood risk, its implications as well as the possibilities of integrating flood management strategies into urban design and planning approaches.

This cooperation among partners outlines the distribution of cost among them, to contribute to the design, integrated development and sustainable

development of the district. It could also involve the municipality and the water management board who would contribute to the costs of the construction and management of a flood defense, with private parties also contributing a proportion to the investment costs in return for direct benefits in terms of reduced flood risk and improved socio-economic conditions within the district.

Figure 1.3. Rotterdam water system (source: Rotterdam Resilience Strategy 2016). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/douay/transitions.zip

Map 1.2. Feijenoord district location (source: Spatially evaluating a network of plans and flood vulnerability using a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard: A case study in Feijenoord district, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, Matthew L. Malecha, A.D. Bran). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/douay/transitions.zip

It is essential to also mention that Rotterdam gets the benefit of learning from other cities’ experiences, especially those who suffered from floods such as New Orleans, USA. They have been collaborating since 2008, particularly with regard to water management concerns. Even after the hurricane Katrina, Dutch experts assisted New Orleans by hosting the “Dutch dialogues”. Learning from these dialogues contributed to the development of New Orleans’ Integrated Water Management Plan.

The strategy of Rotterdam is hopeful to tackle the water problem, not only through the National Delta Program but also through the Climate Proof and Adaptation Strategy of Rotterdam. It includes five main related actions that express how they can work together to adapt the current situation to the expected changes. In brief, they are as follows:

a) plan for climate resilience “critical infrastructure”: a new spatial plan will be developed based on the regional analysis of critical infrastructure resilience to climate change;

b) vertical evacuation planning: it leads to the identification of the concept of “multi-layer safety”. It involves prevention (first layer) spatial adaptation (second layer) and evacuation (third layer). It is, however, yet to be thoroughly planned and developed;

c) climate resilient waterfront areas: there are a diverse range of pilot studies that focus on climate-resilient development in the wider region, looking at both urban and industrial areas. The results of these pilots will be collated and translated into an overall policy for the area outside the dykes in Rotterdam;

d) Rotterdam – the HAGUE Emergency Airport: the strategy will create an economic cluster focusing on clean technology and water security in an airport setting;

e) floating city: Rotterdam stated an ambition to explore opportunities presented by building floating developments.

The adaptive waterfront development includes many detailed actions that aim to facilitate the residents’ livelihood and secure sustainable resources. These actions are:

a) The water squares

There are multifunctional public spaces that, in the event of heavy rains and floods, are transformed into basins for the collection and storage of rainwater. By this, the sewer system is not congested and, additionally, creates the possibility of reuse in times of water stresses.

The idea is to create “floodable” areas in strategic areas of the city that will remain dry 90% of the time, creating meeting points and recreational spaces. The system is advanced by means of hygiene; the rainwater from public spaces and roofs of neighboring buildings will be directed to the treatment plants below the ground and thereafter introduced into the basins of the squares without harmful pollutants. The Benthemplein, a once-empty, monotonous square in a dense neighborhood of Rotterdam, now holds a large rainwater collection system, but it also hosts amphitheaters and sports courts, combining climate resilience with social resilience.

1.4. Benthemplein Water Square in Rotterdam (dry and filled with water) (source: De Urbanisten and Ossip van Duivenbode 2013). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/douay/transitions.zip

b) Parking lots

Beneath the cultural heart of the city, the Museumplein Square is a project aimed to accommodate 1,150 cars and also one of the largest underground water reservoirs in the Netherlands. This structure is supposed to accommodate 12% of the entire water storage capacity needed for the city center.

Figure

Figure 1.5. Parking lot project (source: Urban Green-Blue Grids 2011). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/douay/transitions.zip

c) Multifunctional rooftop program

As a part of the climate adaptation strategies, the city of Rotterdam discovered that the surface area on the existing buildings is about 15,000,000 m2. This immediately meant that this area can potentially be used for providing extra public spaces for citizens and as a tool for further solutions with respect to other complexities such as congestion, densification and global warming. The future roof landscape in Rotterdam will consist of the so-called green, blue, red and yellow roofs. Each color represents a particular function as shown in the illustration below; yellow for solar energy, green for vegetation on roofs, blue for extra water storage and red roofs would have a social function.

The one square kilometer sustainable roofscape city center program offers to add value to dwellers by encouraging a combination of integrated solutions in rooftops, meaning more water storage, increased permeability of the urban area, energy generation, greater ecological value, food production, cleaner air, health and social cohesion amongst other benefits (Rotterdam Resilience Strategy 2016).

Figure 1.6. Rooftop Program, (Source: Rotterdam Resilience Strategy & De Urbanisten; Edited by Munir Khader). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/douay/transitions.zip

1.4. Conclusion

The resilient strategy adopted by the city of Rotterdam has, to a good extent, been able to address the different environmental, social, economic and political aspects of the city. After reading their experiences, goals and actions, we can claim that the whole strategy was well thought of and properly coordinated with the existing situation in terms of its methodology and comprehensiveness. It also dwelled on items at various scales and levels, as well as managed to preserve the city’s identity without neglecting its programs and actions.

However, after the brief assessment of Rotterdam’s Resilience Strategy, perhaps one important question that instantly comes to mind is whether they can actually make the changes they described. Execution of the strategy is

Rotterdam Resilience Strategy, Rotterdam 17

probably the biggest challenge as it can be attested in many other global resilient strategies that only made it through the preparation stage but were never accomplished, mainly due to financial or political reasons.

After such a long, detailed and rigorous process of producing the strategy, it is only essential for the city to get the results and realize the goals within the coming years. It is fair to say that the city succeeded to formulate some strong goals and objectives linked with efficient “detailed actions”, which were derived from the real needs of the city that were addressed by the public and various stakeholders involved in the decision-making process and during the formulation of the strategy. Realizing this resilience strategy could make positive changes in the city at natural, economic and social levels.

1.4. References

100 Resilient Cities (2020a). Rotterdam – 100 Resilient Cities [Online]. Available: https://www.100resilientcities.org/strategies/rotterdam.

100 Resilient Cities (2020b). Strategy Resilient Rotterdam [Online]. Available: https://www.100resilientcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/strategy-resilientrotterdam.pdf.

100 Resilient Citiies (2020c). Resilient Ramallah 2050 [Online]. Available: http:// www.100resilientcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/171024_-Resilient-Ram allah_Spreads-High-res.pdf.

Citypopulation.de (2020). Rotterdam (municipality, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands) –Population statistics, charts, map and location [Online]. Available: https:// www.citypopulation.de/php/netherlands-admin.php?adm2id=0599.

Docplayer.net (2020). Rotterdam. Ready for the 21st century [Online]. Available: https://docplayer.net/48504274-Rotterdam-ready-for-the-21-st-century.html.

Esther Wienese (2020). Rotterdam rooftops – Esther Wienese [Online]. Available: https://estherwienese.nl/rotterdam-rooftops.

Gnoinc.org (2020). The greater New Orleans urban water plan. Greater New Orleans, Inc. Regional Economic Development [Online]. Available: https://gnoinc.org/initiatives/the-greater-new-orleans-water-plan.

Pcbs.gov.ps (2020). Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics [Online]. Available: http://www.pcbs.gov.ps.