Population Genetics and Microevolutionary Theory 2nd Edition

Alan R. Templeton

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/population-genetics-and-microevolutionary-theory-2n d-edition-alan-r-templeton/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Molecular population genetics Hahn

https://ebookmass.com/product/molecular-population-genetics-hahn/

Circuit Theory and Transmission Lines 2nd Edition Ravish R. Singh

https://ebookmass.com/product/circuit-theory-and-transmissionlines-2nd-edition-ravish-r-singh/

Population Health 2nd Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/population-health-2nd-editionebook-pdf/

Genetics and Evolution of Infectious Diseases 2nd Edition Michel Tibayrenc (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/genetics-and-evolution-ofinfectious-diseases-2nd-edition-michel-tibayrenc-editor/

Circuit Theory and Networks Analysis and Synthesis 2nd Edition Ravish R. Singh

https://ebookmass.com/product/circuit-theory-and-networksanalysis-and-synthesis-2nd-edition-ravish-r-singh/

Genetics and Genomics in Nursing Health Care 2nd Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/genetics-and-genomics-in-nursinghealth-care-2nd-edition/

Population: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues 13th Edition John R. Weeks

https://ebookmass.com/product/population-an-introduction-toconcepts-and-issues-13th-edition-john-r-weeks/

Diplomacy: Theory and Practice 6th Edition G. R. Berridge

https://ebookmass.com/product/diplomacy-theory-and-practice-6thedition-g-r-berridge/

The Wiley International Handbook on Psychopathic Disorders and the Law 1st Edition Alan R. Felthous

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-wiley-international-handbookon-psychopathic-disorders-and-the-law-1st-edition-alan-rfelthous/

PopulationGeneticsand MicroevolutionaryTheory

PopulationGeneticsandMicroevolutionaryTheory

SecondEdition

AlanR.Templeton DepartmentofBiology

WashingtonUniversity St.Louis,MO,USA

Thissecondeditionfirstpublished2021

©2021JohnWiley&Sons,Inc.

EditionHistory

2006JohnWiley&Sons,Inc.

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedinaretrievalsystem,ortransmitted, inanyformorbyanymeans,electronic,mechanical,photocopying,recording,orotherwise,exceptas permittedbylaw.Adviceonhowtoobtainpermissiontoreusematerialfromthistitleisavailableat http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

TherightofAlanR.Templetontobeidentifiedastheauthorofthisworkhasbeenassertedinaccordancewithlaw.

RegisteredOffice

JohnWiley&Sons,Inc.,111RiverStreet,Hoboken,NJ07030,USA

EditorialOffice 9600GarsingtonRoad,Oxford,OX42DQ,UK

Fordetailsofourglobaleditorialoffices,customerservices,andmoreinformationaboutWileyproducts,visitusat www.wiley.com.

Wileyalsopublishesitsbooksinavarietyofelectronicformatsandbyprint-on-demand.Somecontentthatappearsin standardprintversionsofthisbookmaynotbeavailableinotherformats.

LimitofLiability/DisclaimerofWarranty

Thecontentsofthisworkareintendedtofurthergeneralscientificresearch,understanding,anddiscussiononlyand arenotintendedandshouldnotberelieduponasrecommendingorpromotingscientificmethod,diagnosis,or treatmentbyphysiciansforanyparticularpatient.Inviewofongoingresearch,equipmentmodifications,changesin governmentalregulations,andtheconstantflowofinformationrelatingtotheuseofmedicines,equipment,and devices,thereaderisurgedtoreviewandevaluatetheinformationprovidedinthepackageinsertorinstructionsfor eachmedicine,equipment,ordevicefor,amongotherthings,anychangesintheinstructionsorindicationofusage andforaddedwarningsandprecautions.Whilethepublisherandauthorshaveusedtheirbesteffortsinpreparingthis work,theymakenorepresentationsorwarrantieswithrespecttotheaccuracyorcompletenessofthecontentsofthis workandspecificallydisclaimallwarranties,includingwithoutlimitationanyimpliedwarrantiesofmerchantability orfitnessforaparticularpurpose.Nowarrantymaybecreatedorextendedbysalesrepresentatives,writtensales materials,orpromotionalstatementsforthiswork.Thefactthatanorganization,website,orproductisreferredtoin thisworkasacitationand/orpotentialsourceoffurtherinformationdoesnotmeanthatthepublisherandauthors endorsetheinformationorservicestheorganization,website,orproductmayprovideorrecommendationsitmay make.Thisworkissoldwiththeunderstandingthatthepublisherisnotengagedinrenderingprofessionalservices. Theadviceandstrategiescontainedhereinmaynotbesuitableforyoursituation.Youshouldconsultwithaspecialist whereappropriate.Further,readersshouldbeawarethatwebsiteslistedinthisworkmayhavechangedor disappearedbetweenwhenthisworkwaswrittenandwhenitisread.Neitherthepublishernorauthorsshallbeliable foranylossofprofitoranyothercommercialdamages,includingbutnotlimitedtospecial,incidental,consequential, orotherdamages.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

Names:Templeton,AlanRobert,author.

Title:Populationgeneticsandmicroevolutionarytheory/AlanR. Templeton.

Description:Secondedition.|Hoboken,NJ:Wiley-Blackwell,2021.| Includesbibliographicalreferencesandindex.

Identifiers:LCCN2021006543(print)|LCCN2021006544(ebook)|ISBN 9781118504239(hardback)|ISBN9781118504369(adobepdf)|ISBN 9781118504345(epub)

Subjects:LCSH:Populationgenetics.|Evolution(Biology)

Classification:LCCQH455.T462021(print)|LCCQH455(ebook)|DDC 576.5/8–dc23

LCrecordavailableathttps://lccn.loc.gov/2021006543

LCebookrecordavailableathttps://lccn.loc.gov/2021006544

CoverDesign:Wiley

CoverImage:CourtesyofAlanR.Templeton

Setin9.5/12.5ptSTIXTwoTextbySPiGlobal,Pondicherry,India

10987654321

ToBonnie andtotheMemoryofLeonBlaustein

Contents

Preface xii

AbouttheCompanionWebsite xiv

1TheScopeandBasicPremisesofPopulationGenetics 1

BasicPremisesofPopulationGenetics 1

DNACanReplicate 1

DNACanMutateandRecombine 3

PhenotypesEmergefromtheInteractionofDNAandEnvironment 7

PopulationGenomics 9

Part1TheScopeandBasicPremisesofPopulationGenetics 17

2ModelingEvolutionandtheHardy–WeinbergLaw 19

HowtoModelMicroevolution 19

TheHardy–WeinbergModel 21

AnExampleoftheHardy–WeinbergLaw 28

ImportanceoftheHardy–WeinbergLaw 30

Hardy–WeinbergforTwoLoci 32

SourcesofLinkageDisequilibrium 39

SomeImplicationsoftheImpactofEvolutionaryHistoryuponDisequilibrium 41

3SystemsofMating 45

Inbreeding 45

DefinitionsofInbreeding 47

AssortativeMating 61

ASimpleModelofAssortativeMating 61

TheCreationofLinkageDisequilibriumbyAssortativeMating 64

AssortativeMatingVersusInbreeding 68

AssortativeMating,LinkageDisequilibrium,andAdmixture 71

DisassortativeMating 73

4GeneticDrift 77

BasicEvolutionaryPropertiesofGeneticDrift 78

FounderandBottleneckEffects 83

GeneticDriftandDisequilibrium 88

GeneticDrift,Disequilibrium,andSystemofMating 89

EffectivePopulationSize 91

InbreedingEffectiveSize 93

VarianceEffectiveSize 97

SomeContrastsBetweenInbreedingandVarianceEffectiveSizes 102

EstimatingEffectivePopulationSizes 110

5GeneticDriftinLargePopulationsandCoalescence 121 NewlyArisenMutations 121

NeutralAlleles 122

TheNeutralTheoryandItsOrigins 122 CritiquesoftheNeutralTheory 129

TheCoalescent 134

TheBasicCoalescentProcess 135

CoalescencewithMutation 143

Genealogies,GeneTrees,andHaplotypeTrees 146 CoalescenceandSpeciesTrees 160

RecombinationandCoalescence 162

6GeneFlowandPopulationSubdivision 169

GeneFlowBetweenTwoLocalPopulations 169

TheBalanceofGeneFlowandDrift 172

AnExampleoftheBalanceofDriftandGeneFlow 183 FactorsInfluencingtheAmountandPatternofGeneFlow 197 Dispersal 197

IsolationbyDistanceandResistance 200

TotalEffectivePopulationSizeinSubdividedPopulations 212 MultipleModesofInheritanceandPopulationStructure 217 Admixture 220

IdentifyingSubpopulationsandPopulationStructure 223 AFinalWarning 235

7PopulationHistory 237

InferringHistoricalEffectivePopulationSizes 239

InferringHistoricalGeneFlowPatternsandAdmixtureEvents 243 UsingHaplotypeTreestoStudyPopulationHistory 249

ExpectedPatternsUnderIsolationbyDistance 257

ExpectedPatternsUnderFragmentation 257

ExpectedPatternsUnderRangeExpansion 259

MultiplePatternsinNested-CladeAnalysis 263

IntegratingHaplotypeTreeInferencesAcrossLociorDNARegions 264

Model-BasedApproachestoPhylogeographicAnalysis 274

DirectStudiesoverSpaceandPastTimes 282

HistoricalPopulationGeneticsandMacroevolution 287

Part2GenotypeandPhenotype 295

8BasicQuantitativeGeneticDefinitionsandTheory 297

“Simple” MendelianPhenotypes 298

ThePhenotypeofElectrophoreticMobility 298

ThePhenotypeofSickling 299

ThePhenotypeofSickleCellAnemia 300

ThePhenotypeofMalarialResistance 301

ThePhenotypeofHealth(Viability) 301

NatureVersusNurture? 302

TheFisherianModelofQuantitativeGenetics 304

QuantitativeGeneticMeasuresRelatedtotheMean 305

QuantitativeGeneticMeasuresRelatedtotheVariance 318

9QuantitativeGenetics:UnmeasuredGenotypes 321

CorrelationBetweenRelatives 322

TheDistinctionBetweenHeritabilityandInheritance 329

ResponsetoSelection 331

TheProblemofBetween-PopulationDifferencesinMeanPhenotype 332 ControlledCrossesfortheAnalysesofBetweenPopulationDifferences 338

TheBalanceBetweenMutation,Drift,andGeneFlowUponPhenotypicVariance 343

10QuantitativeGenetics:MeasuredGenotypes 345

MarkerAssociationStudies 347

AdmixtureMapping 347

MarkersofLinkage 350

Genome-WideAssociationStudies 356

CandidateLoci 366

CandidateLociandGeneticArchitecture 379

Pleiotropy 380

Epistasis 381

PleiotropyandEpistasis 387

GenebyEnvironmentInteractions 389

GeneticArchitecture:IstheWholeGreaterthantheSumoftheParts? 390

Part3NaturalSelectionandAdaptation 393

11NaturalSelection 395

TheFundamentalEquationofNaturalSelection:MeasuredGenotypes 397

Sickle-cellAnemiaasanExampleofNaturalSelection 400

AdaptationasaPolygenicProcess 409

TheFundamentalTheoremofNaturalSelection:UnmeasuredGenotypes 411

SomeImplicationsoftheFundamentalEquationsofNaturalSelection 413

TheCourseofAdaptationandNaturalSelection 422

Contents

12InteractionsofNaturalSelectionwithOtherEvolutionaryForcesandthe DetectionofNaturalSelection 423

TheInteractionofNaturalSelectionwithMutation 424

TheInteractionofNaturalSelectionwithMutationandSystemofMating 426

TheInteractionofNaturalSelectionwithGeneFlow 429

TheInteractionofNaturalSelectionwithGeneticDrift 435

TheInteractionsofNaturalSelection,GeneticDrift,andGeneFlow 441

PopulationSubdivision 445

GeneticArchitecture 446

TheInteractionsofNaturalSelection,GeneticDrift,andMutation 451

TheInteractionsofNaturalSelection,GeneticDrift,Mutation,andRecombination 465 CandidateLoci 468

QuantitativeGeneticApproachestoDetectingSelection 471

TheNeutralist/SelectionistDebate 474

13UnitsandTargetsofSelection 475

TheUnitofSelection 477

TargetsofSelectionBelowtheLeveloftheIndividual 483

TheGenome 483

Gametes 489

SomaticCells 501

OverviewofSelectionBelowtheLevelofanIndividual 502

TargetsofSelectionAbovetheLeveloftheIndividual 503

SexualSelection 503

Fertility/Fecundity 508

CompetitionandCooperation 511

Kin/FamilySelection 516

14SelectioninHeterogeneousEnvironments 523

Coarse-grainedSpatialHeterogeneity 524

Coarse-grainedTemporalHeterogeneity 546

SeasonalandCyclicalVariation 547

RandomorFrequentTemporalVariation 549

Sporadic,RecurrentEnvironments 551

TransitionstoaNewLong-termEnvironment 554

Fine-grainedHeterogeneity 558

Coevolution 567

15SelectioninAge-StructuredPopulations 574

LifeHistoryandFitness 574

TheEvolutionofSenescence 581

AbnormalAbdomen:AnExampleofSelectioninanAge-StructuredPopulation 586

GeneticArchitectureandUnitsandTargetsofSelectionBelowtheLevelof theIndividual 586

GeneticArchitectureandUnitsofSelectionattheLeveloftheIndividual 592

PhenotypesandPotentialTargetsofSelectionattheLeveloftheIndividual 594

NaturalSelectiononthe aa SupergeneinaSpatiallyandTemporallyHeterogeneous

Environment 603

NaturalSelectionontheComponentsofthe aa Supergene 614

Overview 616

ComparativeAnalysis 617

Reductionism 617

Holism 618

MonitoringPopulations 620

AppendixA:GeneticSurveyTechniques 622

AppendixB:ProbabilityandStatistics 636

References 668

Index 723

Preface

Muchhaschangedinpopulationgeneticssincethefirsteditioncameoutin2006,andmuchhas stayedthesame.Thescope,questions,andmethodsofpopulationgeneticshavealwaysbeenconstrainedbythetechniquesavailableforsurveyinggeneticvariation,andtheDNA/genomicsrevolutioncontinuestoaltertheseconstraints.Yet,thebasicpremisesofpopulationgenetictheoryand practicehaveremainedthesame.Thesecorepremisesallowthissecondeditiontogrowsmoothly outofthefirstedition,sothebasicstructureofthiseditionisidenticaltothatofthefirst.However, therevolutioninDNAtechnologiesandgenomicsleadstoasignificantexpansionoftopicsand scope.Theconceptsandmethodsfrompopulationgeneticsarenowwidelyusedinalmostallfields ofbiology,frommolecularbiologytoecology,andinappliedfieldsfromgeneticepidemiologyto conservationbiology.

Thisexpandedapplicabilityofpopulationgeneticsisillustratedwellbythefinalresearchproject ofmylong-termcollaboratorandfriend,LeonBlaustein,whosadlydiedalltooyoungin2020.By trainingandcareer,Leonwasafreshwaterpopulation/communityecologistwithagreatconcern forconservationapplications.Hisfinalprojectfocusedonplasticityinaquaticresourceuseinthe endangeredspecies Salamandrainfraimmaculta atitssouthernmostboundaryinnorthernIsrael. Mostsalamandersspecializeinthetypeofaquatichabitattheyusefortheirlarvalphase,but S. infraimmaculta canusepermanentpondsandsprings,permanentandseasonalstreams,aswell asrockpoolsthatfillwithrainwaterforonlyafewmonthsoftheyear.Leonassembledadiverse teamofgraduatestudents,post-docs,andcollaboratorstoaddressthissystemfrommultipledirections.Leonfirstsoughttodefinetheevolutionaryandecologicalcontextinwhichthisplasticityis manifest.Leonandhisgroupperformedsurveysofmoleculargeneticdiversity,maximumentropy modelingofhabitatdatatodetermineoptimalandsub-optimalareas,andphylogeographicanalysestouncoverhistoricaleffects.Hisgroupperformedmark/recapturestudiestoestimateadult populationsizesinadiversityofhabitats.Thesestudiesrevealedthatthissouthernmostboundary washighlyheterogeneous,varyingfromareasofoptimalhabitatwithhighlevelsofgeneticdiversityandgeneflow,toareasofmarginalhabitatthatwerestronglysubdividedgenetically,andtoan areaofoptimalhabitatthatwasanhistoricalisolatewithaseverereductioningeneticdiversitydue toapastfounderevent.Fieldandlaboratoryexperimentsonlarvaldevelopmentalandmorphologicalplasticityaswellasontheirtranscriptomesrevealedthatplasticityatboththeorganismaland transcriptomelevelsdisplayedbothgeneticallybaseddifferencesamongthesepopulationsand directindividualresponsivenesstoenvironmentalvariation.Couplingclimateprojectionmodels withthemaximumentropymodelsrevealeddiverseconservationchallengesinthesedifferent areasofthesouthernmostboundary.Hence,boththeevolvabilityofplasticityandcurrentindividualenvironmentalplasticitycouldplayanimportantroleinthesurvivalofthisendangeredspecies.

Althoughnotapopulationgeneticist,Leon’sfinalprojectillustrateswelltheimportanceofusing populationgeneticsandgenomicsinotherfieldsofbiology.

Theincreasingscopeandrelevanceofpopulationgeneticstomanyfieldsofbasicandapplied biologyalsomeansanexpandedaudiencethatneedstobeknowledgeableofpopulationgenetic theoryandpractice.Thiseditioniswrittenwiththisexpandedaudienceinmind.Manyexamples aregivenfromconservationbiology,humangenetics,andgeneticepidemiology,yetthefocusof thisbookremainsonthebasicmicroevolutionarymechanismsandhowtheyinteracttocreateevolutionarychange.Thisbookisintendedtoprovideasolidunderstandingofthecoreconceptsin populationgeneticsbothforthosestudentsprimarilyinterestedinevolutionarybiologyandgeneticsandforthosestudentsprimarilyinterestedinapplyingthetoolsofpopulationgeneticsinother areassuchasconservationbiology,geneticepidemiology,andgenomics.Withoutasolidfoundationinpopulationgenetics,theanalyticaltoolsemergingfrompopulationgeneticswillfrequently bemisappliedandincorrectinterpretationscanbemade.Thisbookisdesignedtoprovidethat foundationbothforfuturepopulationandevolutionarygeneticistsandforthosewhowillbeapplyingpopulationgeneticconceptsandtechniquestootherareas.

IthankDavidQuellerforreadingoveradraftofthisedition.Hismanysuggestionsandcorrectionswerehighlyvaluable,andIgreatlyappreciatehisefforts.Davidalsousedsomeofthedraftsof thiseditioninthe2020classonPopulationGeneticsatWashingtonUniversity.Ithankthestudents ofthatclassfortheirsuggestionsandcorrections.Finally,Ithankallthepaststudentsofmycourse onpopulationgeneticsandmyformergraduatestudentsandpost-docs.Theyweretheinspiration forthisbookinthefirstplace,andtheycontributedvaluableinputtothefirstedition,muchof whichhascarriedovertothesecondedition.

AbouttheCompanionWebsite

Thisbookisaccompaniedbyacompanionwebsite.

www.wiley.com/go/templeton/populationgenetics2

Thiswebsiteincludes:

• PowerpointslidesofFiguresfromthebook

• ProblemandAnswersets

TheScopeandBasicPremisesofPopulationGenetics

Populationgeneticsisconcernedwiththeorigin,amount,anddistributionofgeneticvariation presentinpopulationsoforganismsandthefateofthisvariationthroughspaceandtime.Thekinds ofpopulationsthatwillbetheprimaryfocusofthisbookarepopulationsofsexuallyreproducing diploidorganisms,andthefateofgeneticvariationinsuchpopulationswillbeexaminedator belowthespecieslevel.Variationingenesthroughspaceandtimeconstitutesthefundamental basisofevolutionarychange;indeed,initsmostbasicsense, evolution isthegenetictransformationofreproducingpopulationsoverspaceandtime.Populationgeneticsis,therefore,atthevery heartofevolutionarybiologyandcanbethoughtofasthescienceofthemechanismsresponsible for microevolution,evolutionwithinspecies.Manyofthesemechanismshaveagreatimpact ontheoriginofnewspeciesandonevolutionabovethespecieslevel(macroevolution).Afew oftheimpactsofpopulationgeneticsuponspeciesandspeciationwillbediscussed,butthisis notthemainfocusofthisbook.

BasicPremisesofPopulationGenetics

Microevolutionarymechanismsworkupongeneticvariability,soitisnotsurprisingthatthe fundamentalpremisesthatunderliepopulationgenetictheoryandpracticealldealwithvarious propertiesofDNA,themoleculethatencodesgeneticinformationinmostorganisms.(AfeworganismsuseRNAastheirgeneticmaterial,andthesamepropertiesapplytoRNAinthosecases.) Indeed,thetheoryofmicroevolutionarychangestemsfromjustthreepremises:

• DNAcanreplicate

• DNAcanmutateandrecombine

• PhenotypesemergefromtheinteractionofDNAandenvironment

Theimplicationsofeachofthesepremiseswillnowbeexamined.

DNACanReplicate

BecauseDNAcanreplicate,aparticularkindofgene(specificsetofnucleotides)canbepassedon fromonegenerationtothenextandcanalsocometoexistasmultiplecopiesindifferentindividuals.Genes,therefore,haveanexistenceintimeandspacethattranscendstheindividualsthat temporarilybearthem.Thebiologicalexistenceofgenesoverspaceandtimeis thephysicalbasis ofevolution

PopulationGeneticsandMicroevolutionaryTheory,Second Edition.AlanR.Templeton. ©2021JohnWiley&Sons,Inc.Published2021byJohnWiley&Sons,Inc. Companionwebsite:www.wiley.com/go/templeton/populationgenetics2

Thephysicalmanifestationofagene’scontinuityovertimeandthroughspaceisareproducing populationofindividuals.Individualshavenocontinuityoverspaceortime;individualsareunique eventsthatliveandthendieandcannotevolve.ButthegenesthatanindividualbearsarepotentiallyimmortalthroughDNAreplication.Forthispotentialtoberealized,theindividualsmust reproduce.Therefore,toobserveevolution,itisessentialtostudyapopulationofreproducingindividuals.Areproducingpopulationdoeshavecontinuityovertimeasonegenerationofindividuals isreplacedbythenext.Areproducingpopulationgenerallyconsistsofmanyindividuals,andthese individualscollectivelyhaveadistributionoverspace.Hence,areproducingpopulationhascontinuityovertimeandspaceandconstitutesthephysicalrealityofagenes’ continuityovertimeand space.Evolutionisthereforepossibleonlyatthelevelofareproducingpopulationandnotatthe leveloftheindividualscontainedwithinthepopulation.

Thefocusofpopulationgeneticsmustbeuponreproducingpopulationstostudymicroevolution. However,theexactmeaningofwhatismeantbyapopulationisnotfixed,butrathercanvary dependinguponthequestionsbeingaddressed.Thepopulationcouldbealocalbreedinggroup ofindividualsfoundinclosegeographicproximity,oritcouldbeacollectionoflocalbreeding groupsdistributedoveralandscapesuchthatmostindividualsonlyhavecontactwithothermembersoftheirlocalgroupbutthat,onoccasion,thereissomereproductiveinterchangeamonglocal groups.Alternatively,apopulationcouldbeagroupofindividualscontinuouslydistributedovera broadgeographicalareasuchthatindividualsattheextremesoftherangeareunlikelytoevercome intocontact.Sometimes,thepopulationincludestheentirespecies.Withinthishierarchyofpopulationsfoundwithinspecies,muchofpopulationgeneticsfocusesuponthe localpopulation or deme,acollectionofinterbreedingindividualsofthesamespeciesthatliveinsufficientproximity thattheyshareasystemofmating.Systemsofmatingwillbediscussedinmoredetailinsubsequent chapters,but,fornow,the systemofmating referstotherulesbywhichindividualspairforsexual reproduction.Theindividualswithinademeshareacommonsystemofmating.Becauseademeis abreedingpopulation,individualsarecontinuallyturningoverasbirthsanddeathsoccur,butthe localpopulationisadynamicentitythatcanpersistthroughtimefarlongerthantheindividuals thattemporarilycompriseit.Thelocalpopulation,therefore,hastheattributesthatallowthephysicalmanifestationofthegeneticcontinuityoverspaceandtimethatfollowsfromthepremisethat DNAcanreplicate.

Becauseourprimaryinterestisongeneticcontinuity,wewillmakeausefulabstractionfrom thedeme.Associatedwitheverypopulationofindividualsisacorrespondingpopulationofgenes calledthe genepool ,thesetofgenescollectivelysharedbytheindividualsofthepopulation.An alternative,andoftenmoreuseful,wayofdefiningthegenepoolisthatthegenepoolisthepopulationofpotentialgametesproducedbyalltheindividualsofthepopulation.Gametesarethe bridgesbetweenthegenerations,sodefiningagenepoolasapopulationofpotentialgametes emphasizesthegeneticcontinuityovertimethatprovidesthephysicalbasisforevolution. Forempiricalstudies,thefirstdefinitionisprimarilyused;fortheory,theseconddefinitionis preferred.

Thegenepoolassociatedwithapopulationisdescribedbymeasuringthenumbersandfrequenciesofthevarioustypesofgenesorgenecombinationsinthepool. Evolution isdefinedasachange throughtimeofthefrequenciesofvarioustypesofgenesorgenecombinationsinthegenepool. Thisdefinitionisnotintendedtobeanall-encompassingdefinitionofevolution.Rather,itis anarrowandfocuseddefinitionofevolutionthatisusefulinmuchofpopulationgenetics preciselybecauseofitsnarrowness.Thiswillthereforebeourprimarydefinitionofevolutionin thisbook.

Sinceonlyalocalpopulationattheminimumcanhaveagenepool,onlypopulationscanevolve underthisdefinitionofevolution,notindividuals.Therefore,evolutionisanemergentpropertyof reproducingpopulationsofindividualsthatisnotmanifestedintheindividualsthemselves.However,therecanbehigherorderassemblagesoflocalpopulationsthatcanevolve.Inmanycases,we willconsidercollectionsofseverallocalpopulationsthatareinterconnectedbydispersalandreproduction,uptoandincludingtheentirespecies.However,anentirespeciesinsomecasescouldbe justasingledemeoritcouldbeacollectionofmanydemeswithlimitedreproductiveinterchange. Aspeciesisthereforenotaconvenientunitofstudyinpopulationgeneticsbecausespeciesstatus itselfdoesnotdefinethereproductivestatusthatissocriticalinpopulationgenetictheory.Wewill alwaysneedtospecifythetypeandlevelofreproducingpopulationthatisrelevantforthequestions beingaddressed.

DNACanMutateandRecombine

Evolutionrequireschange,andchangecanonlyoccurwhenalternativesexist.IfDNAreplication werealways100%accurate,therewouldbenoevolution.Anecessaryprerequisiteforevolutionis geneticdiversity.Theultimatesourceofthisgeneticdiversityismutation.Therearemanyformsof mutation,suchassinglenucleotidesubstitutions,insertions,deletions,transpositions,andduplications.Fornow,ouronlyconcernisthatthesemutationalprocessescreatediversityinthepopulationofgenespresentinagenepool.Becauseofmutation,alternativecopiesofthesame homologousregionofDNAinagenepoolwillshowdifferentstates.

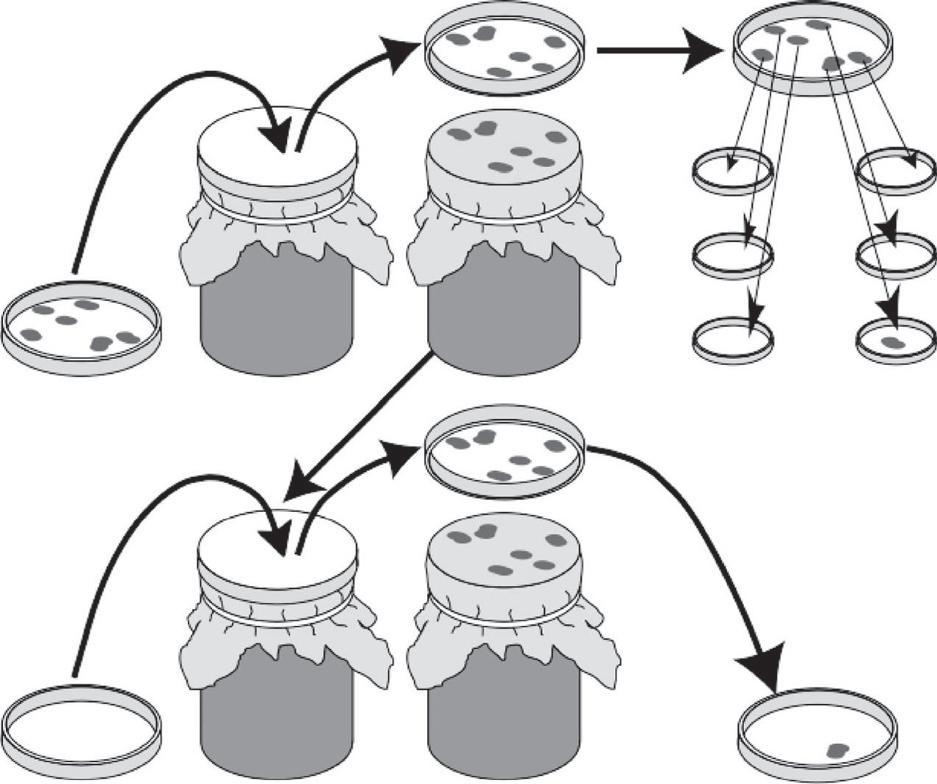

Mutationoccursatthemolecularlevel.Althoughmanyenvironmentalagentscaninfluencethe rateandtypeofmutation,oneofthecentraltenetsofDarwinianevolutionisthatmutationsare randomwithrespecttotheneedsoftheorganismincopingwithitsenvironment.Therehavebeen manyexperimentsaddressingthistenet,butoneofthemoreelegantandconvincingisreplicaplating,firstusedbyJoshuaandEstherLederberg(1952)(Figure1.1).Replicaplatingandotherexperimentsprovideempiricalproofthatmutation,occurringonDNAatthemolecularlevel,isnotbeing directedtoproduceaparticularphenotypicconsequenceatthelevelofanindividualinteracting withitsenvironment.Therefore,wewillregardmutationsasbeingrandomwithrespecttothe organism’sneedsincopingwithitsenvironment(although,aswewillseesoon,mutationishighly nonrandominotherrespectsatthemolecularlevel).

Mutationcreatesallelicdiversity. Alleles arealternativeformsofagene.Insomecases,genetic surveysfocusonaregionofDNAthatmaynotbeageneinaclassicalsense;itmaybeaDNAregion muchlargerorsmallerthanagene,oranoncodingregion.Wewillusetheterm haplotype to refertoanalternativeform(specificnucleotidesequence)amongthehomologouscopiesofa definedDNAregion,whetherageneornot.Theallelicorhaplotypicdiversitycreatedbymutation canbegreatlyamplifiedbythegeneticmechanismsofrecombinationanddiploidy.Inmuchof genetics,recombinationreferstomeioticcrossingover,butweusethetermrecombinationin abroadersenseasanygeneticmechanismthatcancreatenewcombinationsofallelesorhaplotypes.Thisdefinitionofrecombinationencompassesthemeioticeventsofbothindependent assortmentandofcrossingoverandalsoincludesgeneconversionandanynon-meioticeventsthat createnewgenecombinationsthatcanbepassedonthroughagametetothenextgeneration.Sexualreproductionanddiploidycanalsobethoughtofasmechanismsthatcreatenewcombinations ofgenes.

Asanillustrationofthegeneticdiversitythatcanbegeneratedbythejointeffectsofmutationand recombination,considerthe MHC complex(majorhistocompatibilitycomplex,alsoknownin

Plate 1. Bacteria Grown in Absence of Streptomycin

Bacterial Plate Pressed on Velvet

Plate 2. Sterile Plate with Streptomycin

Sterile Plate Pressed on Imprinted Velvet

Bacterial Colonies Imprinted on Velvet

Each Bacterial Colony on Plate 1 is Isolated and Tested for Growth on a Plate with Streptomycin: Only one Colony Grows

Only one Colony Crows on Streptomycin

Figure1.1 Replicaplating.AsuspensionofbacterialcellsisspreaduponaPetridish(plate1)suchthateach individualbacteriumshouldbewellseparatedfromallothers.Eachbacteriumthengrowsintoacolonyof geneticallyidenticalindividuals.Next,acircularblockcoveredwithvelvetispressedontothesurfaceofplate 1.Somebacteriafromeachcolonysticktothevelvet,soaduplicateoftheoriginalplateismadewhenthe velvetispressedontothesurfaceofasecondPetridish(plate2),calledthereplicaplate.Themediumonthe replicaplatecontainsstreptomycin,anantibioticthatkillsmostbacteriafromtheoriginalstrain.Inthe exampleillustrated,onlyonebacterialcolonyonthereplicaplatecangrowonstreptomycin,anditsposition onplate2identifiesitasthedescendantofaparticularcolonyonplate1.Eachbacterialcolonyonplate1is thentestedforgrowthonaplatewiththeantibioticstreptomycin.Ifmutationswererandomandstreptomycin simplyselectedpreexistingmutationsratherthaninducingthem,thenthecoloniesonplate1thatoccupied thepositionsassociatedwithresistantcoloniesonplate2shouldalsoshowresistance,eventhoughthese colonieshadnotyetbeenexposedtostreptomycin.Asshown,thiswasindeedthecase.

humansas HLA,humanleukocyteantigen)ofabout200genesonthesamechromosome.Table1.1 showsthenumberofallelesfoundat26oftheselociasofJuly2018inhumanpopulationsin an HLA database(Robinsonetal.2015).Ascanbeseen,mutationalchangesattheseloci havegeneratedfrom1to5212alleles/locuswithatotalof18690allelesoverall26loci.However, theselocicananddorecombine.Hence,recombinationhasthepotentialofcombiningthese 18690allelesinto7.48×1042 distinctgametetypes(obtainedbymultiplyingtheallelenumbers ateachlocus).Sexualreproductionhasthepotentialofbringingtogetherallpairsofthesegamete typesinadiploidindividual,resultingin2.07×1079 genotypes.Andthisisonlyfrom26lociinone smallregionofonechromosomeofthehumangenome!Giventhatthereareonlyabout7.7×109 humansintheworldatthebeginningof2019,everyoneintheworld(withtheexceptionofidentical twins)willhaveaunique HLA genotypewhenthese26lociareconsideredsimultaneouslyasthere aremanymorepossiblegenotypesthanhumanindividuals.But,ofcourse,humansdifferatmany

Table1.1 Numbersofallelesknownin2018at26loci withinthe human MHC (HLA)region.

Source: DatabasedescribedinRobinsonetal.(2015)asupdated onJuly2018.

morelocithanjustthese26.Asof2015,88milliongeneticvariantswereknowninthehuman genome(The1000GenomesProjectConsortium2015).Assumingthatmostofthesearebiallelic, eachpolymorphicnucleotidedefinesthreegenotypes,socollectivelythenumberofpossible genotypesdefinedbytheseknownpolymorphicsitesis388,000,000 =1041,986670 genotypes.Toput thisnumberintoperspective,thenumberofelectronsintheknownuniverseis1081 (https://www.quora.com/Approximately-how-many-electrons-are-there-in-the-known-Universe), anumberfarsmallerthanthenumberofpotentialgenotypesthatarepossibleinhumanityjust withknowngeneticvariation.Hence,mutationandrecombinationcangeneratetrulyastronomical levelsofgeneticvariation.

Thedistinctionbetweenmutationandrecombinationisoftenblurredbecauserecombination canoccurwithinageneandtherebycreatenewallelesorhaplotypes.Forexample,71individualsfromthreehumanpopulationsweresequencedfora9.7kbregionwithinthe lipoprotein lipase (LPL)locus(Nickersonetal.1998).Thisrepresentsjustaboutathirdofthisonelocus.In all,88variablesiteswerediscovered,and69ofthesesiteswereusedtodefine88distincthaplotypesoralleles.These88haplotypesarosefromatleast69mutationalevents(aminimumof onemutationforeachofthe69variablenucleotidesites)coupledwithabout30recombination andgeneconversionevents(Templetonetal.2000a).Thus,intragenicrecombinationandmutationhavetogethergenerated88haplotypesasinferredusingonlyasubsetoftheknownvariable sitesinjustathirdofasinglegeneinasampleof142chromosomes.These88haplotypes inturndefine3916possiblegenotypes – anumberconsiderablylargerthanthesamplesize of71people.

Studiessuchasthosementionedabovemakeitclearthatmutationandrecombinationcan generatelargeamountsofgeneticdiversityatparticularlociorchromosomalregions,butthey donotaddressthequestionofhowmuchgeneticvariationispresentwithinspeciesingeneral. Howmuchgeneticvariationispresentinnaturalpopulationswasoneofthedefiningquestions ofpopulationgeneticsupuntilthemid-1960s.Beforethen,mostofthetechniquesusedtodefine genesrequiredgeneticvariationtoexist.Forexample,manyoftheearlyimportantdiscoveriesin MendeliangeneticsweremadeinthelaboratoryofThomasHuntMorganduringthefirstfew decadesofthetwentiethcentury.Thislaboratoryusedmorphologicalvariationinthefruitfly Drosophilamelanogaster asitssourceofmaterialtostudy.Amongthegenesidentifiedinthis laboratorywasthelocusthatcodesforanenzymeineyepigmentbiosynthesisknownas vermillion in Drosophila.Morganandhisstudentscouldonlyidentify vermillion asageneticlocus becausetheyfoundamutantthatcodedforadefectiveenzyme,therebyproducingaflywith brightredeyes.Ifageneexistedwithnoallelicdiversityatall,itcouldnotevenbeidentified asalocuswiththetechniquesusedinMorgan’slaboratory.Hence, all observablelocihadatleast twoallelesinthesestudies(the “wildtype” and “mutant ” allelesinMorgan ’sterminology).Asa result,eventhesimplequestionofhowmanylocihavemorethanoneallelecouldnotbe answereddirectly.Thissituationchangeddramaticallyinthemid-1960swiththefirstapplicationsofmoleculargeneticsurveys(firstonproteins,laterontheDNAdirectly;seeAppendix A,whichgivesabriefsurveyofthemoleculartechniquesusedtomeasuregeneticvariation). Thesenewmoleculartechniquesallowedgenestobedefinedbiochemicallyandirrespective ofwhetherornottheyhadallelicvariation.Theinitialstudies(Harris1966;Johnsonetal. 1966;LewontinandHubby1966),usingtechniquesthatcouldonlydetectmutationscausing aminoacidchangesinproteincodingloci(andonlyasubsetofallaminoacidchangesatthat), revealedthataboutathirdofallproteincodinglociwerepolymorphic(i.e.alocuswithtwo ormoreallelessuchthatthemostcommonallelehasafrequencyoflessthan0.95inthegene pool)inavarietyofspecies.Asourgeneticsurveytechniquesacquiredgreaterresolution (AppendixA),thisfigurehasonlygoneup.

Thesegeneticsurveyshavemadeitclearthatmanyspecies,includingourown,haveliterally astronomicallylargeamountsofgeneticvariation.ThechaptersinSection1ofthisbookwillexaminehowpremises1and2combinetoexplaingreatcomplexityatthepopulationlevelintermsof theamountofgeneticvariationanditsdistributioninindividuals,withindemes,amongdemes, andoverspaceandtime.Becauseitisnowclearthatmanyspecieshavevastamountsofgenetic variation,thefieldofpopulationgeneticshasbecomelessconcernedwiththeamountofgenetic variationandmoreconcernedwithitsphenotypicandevolutionarysignificance.Thisshiftin emphasisleadsdirectlyintoourthirdandfinalpremise.

PhenotypesEmergefromtheInteractionofDNAandEnvironment

A phenotype isameasurabletraitofanindividual(oraswewillseelater,itcanbegeneralized tootherunitsofbiologicalorganization).InMorgan’sday,genescouldonlybeidentifiedthrough theirphenotypiceffects.Thegenewasoftennamedforitsphenotypiceffectinahighlyinbred laboratorystrainmaintainedundercontrolledenvironmentalconditions.Thismethodofidentifyinggenesledtoasimple-mindedequatingofgeneswithphenotypesthatstillplaguesustoday. Almostdaily,onereadsabout “thegeneforcoronaryarterydisease,”“thegeneforthrill seeking,” etc.Equatinggeneswithphenotypesisreinforcedbymetaphorsappearinginmany textbooksandsciencemuseumstotheeffectthatDNAisthe “blueprint” oflife.However, DNAisnotablueprintforanything;thatisnothowgeneticinformationisencodedorprocessed. Forexample,thehumanbraincontainsabout1011 neuronsand1015 neuronalconnections (CoveneyandHighfield1995).DoestheDNAprovideablueprintforthese1015 connections? Theanswerisanobvious “NO.” Thereareonlyabout3billionbasepairsinthehumangenome. Evenifeverybasepaircodedforabitofinformation,thereisinsufficientinformationstorage capacityinthehumangenomebyseveralordersofmagnitudetoprovideablueprintfortheneuronalconnectionsofthehumanbrain.DNAdoesnotprovidephenotypicblueprints;instead,the informationencodedinDNAcontrolsdynamicprocesses(suchasaxonalgrowthpatternsand signalresponses)thatalwaysoccurinanenvironmentalcontext.Thereisnodoubtthatenvironmentalinfluenceshaveanimpactonthenumberandpatternofneuronalconnectionsthat developinmammalianbrainsingeneral.Itisthisinteractionofgeneticinformationwith environmentalvariablesthroughdevelopmentalprocessesthatyieldsphenotypes(suchasthe precisepatternofneuronalconnectionsofaperson’sbrain).Genesshouldneverbeequated tophenotypes.Phenotypesemergefromgeneticallyinfluenceddynamicprocesseswhoseoutcome dependsuponenvironmentalcontext.

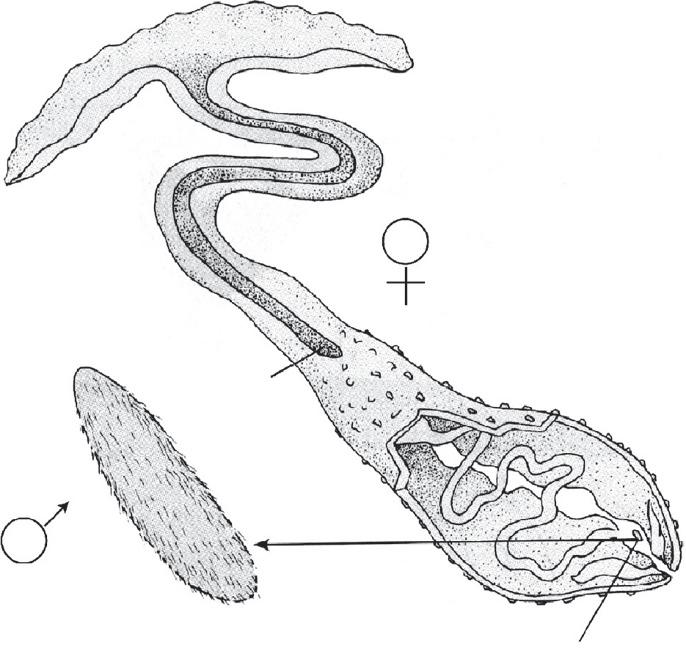

Inthisbook,phenotypesarealwaysregardedasarisingfromaninteractionofgenotypewith environment.Themarineworm Bonellia (Figure1.2)providesanexampleofthisinteraction (GilbertandSarkar2000).Thefree-swimminglarvalformsofthesewormsaresexuallyundifferentiated.Ifalarvasettlesaloneonthenormalmudsubstrate,itbecomesafemalewithalong (about15cm)tubeconnectingaproboscistoamoreroundedpartofthebodythatcontainsthe uterus.Ontheotherhand,thelarvaeareattractedtofemales,andifitcanfindafemale,itdifferentiatesintoamalethatexistsasaciliatedmicroparasiteinsidethefemale.Thebodyforms aresodifferenttheywereinitiallythoughttobetotallydifferentcreatures.Hence,thesame genotype,dependinguponenvironmentalcontext,canyieldtwodrasticallydifferentbodytypes. Theinteractionbetweengenotypeandenvironmentinproducingphenotypeiscriticalforunderstandingtheevolutionarysignificanceofgeneticvariability,sothechaptersinSection2will bedevotedtoanexplorationofthepremisethatphenotypesemergefromagenotype-byenvironmentinteraction.

Asapreludetowhytheinteractionofgenotypeandenvironmentissocriticaltoevolution, considerthefollowingphenotypesthatanorganismcandisplay:

• Beingaliveversusbeingdead:thephenotypeof viability (theabilityoftheindividualtosurvive intheenvironment)

• Givenbeingalive,havingmatedversusnothavingmated:thephenotypeof matingsuccess (theabilityofalivingindividualtofindamateintheenvironment)

• Givenbeingaliveandmated,thenumberofoffspringproduced:thephenotypeof fertility or fecundity (thenumberofoffspringthemated,livingindividualcanproduceinthe environment).

Figure1.2 Sexesin Bonellia.Thefemalehasawalnut-sizedbodythatisusuallyburiedinthemudwitha protrudingproboscis.Themaleisaciliatedmicroorganismthatlivesinsidethefemale. Source: Adapted fromFigure3.18from Genetics,3rdEdition,byPeterJ.Russell.Copyright©1992byPeterJ.Russell. ReprintedbypermissionofPearsonEducation,Inc.

Thethreephenotypesgivenaboveplayanimportantroleinmicroevolutionarytheorybecause, collectively,thesephenotypesdeterminethechancesofanindividualpassingonitsDNAinthe contextoftheenvironment. Reproductivefitness isthecollectivephenotypeproducedbycombiningthesethreecomponentsrequiredforpassingonDNAintoasinglemeasure.Fitnesswillbe discussedindetailinSection3ofthisbook.Reproductivefitnessturnspremise1(DNAcanreplicate)intoreality.DNAisnottrulyself-replicating.DNAcanonlyreplicateinthecontextofan individualsurvivinginanenvironment,matinginthatenvironment,andproducingoffspring inthatenvironment.Hence,thephenotypeofreproductivefitnessunitespremise3(phenotypes aregene-by-environmentinteractions)withpremise1(DNAcanreplicate).Thisunificationof premisesimpliesthattheprobabilityofDNAreplicationisdeterminedbyhowthegenotypeinteractswiththeenvironment.Inapopulationofgeneticallydiverseindividuals(arisingfrompremise 2thatDNAcanmutateandrecombine),itispossiblethatsomegenotypeswillinteractwiththe environmenttoproducemoreorfeweractsofDNAreplicationthanothergenotypes.Hence, theenvironmentinfluencestherelativechancesforvariousgenotypesofreplicatingtheirDNA. AswewillseeinSection3ofthisbook,thisinfluenceoftheenvironment(premise3)upon DNAreplication(premise1)ingeneticallyvariablepopulations(premise2)isthebasisfornatural selectionandoneofthemajoremergentfeaturesofmicroevolution: adaptation totheenvironment.Adaptationreferstoattributesandtraitsdisplayedbyorganismsthataidtheminliving andreproducinginspecificenvironments.Adaptationisoneofthemoredramaticfeaturesof evolution,and,indeed,itwasthemainfocusofthetheoriesofDarwinandWallace.Adaptation canonlybeunderstoodintermsofathree-wayinteractionamongallofthecentralpremisesof populationgenetics(Figure1.3).

Thisbookusesthesethreepremisesinaprogressivefashion:Section1utilizespremises1 (DNAcanreplicate)and2(DNAcanmutateandrecombine),whicharemolecularinfocus,

Proboscis

Mouth

Uterus

Premise I : DNA Can Replicate

Premise II: DNA Can Mutate & Recombine

Heritable Variation in the Phenotype of Reproductive Fitness

Premise III: Phenotypes Emerge from the Interaction of DNA and Environment

Genetically Variable Population of Individuals

Figure1.3 Theintegrationofthethreefundamentalpremisesofpopulationgenetictheorythroughthe phenotypeofreproductivefitness.

toexplaintheamountandpatternofgeneticvariationundertheassumptionthatthevariationhas nophenotypicsignificanceonreproductivefitness.Section2focusesuponpremise3(phenotypes emergefromtheinteractionofDNAandenvironment)andconsiderswhathappenswhen geneticvariationdoesinfluencephenotype.Finally,Section3considerstheemergentevolutionary propertiesthatarisefromtheinteractionsofallthreepremises(Figure1.3)andspecificallyfocuses uponadaptationthroughnaturalselection.Inthismanner,wehopetoachieveathoroughand integratedtheoryofmicroevolutionaryprocesses.

PopulationGenomics

Microevolutionaryprocessesdependupontheexistenceofgeneticvariationinthegenepool,soitis notsurprisingthatthequestionsaskedandapproachesusedinpopulationgeneticresearchare heavilyinfluencedbythetechniquesavailableforsurveyinggeneticvariationinapopulation. Theimportanceofthetechniqueusedtosurveyvariationwasalreadymentionedabovewith respecttooneoftheearliestandmostfundamentalquestionsofpopulationgenetics – howmuch variationexistsinagenepool?Asthefieldofmoleculargeneticsmaturedintogenomics,therehas beenexplosivegrowthintheabilitytoaddressevermorefundamentalquestionsinunprecedented detailinpopulationgenetics.Theapplicationofgenomictechniquestoaddresspopulationgenetic questionsisreferredtoas populationgenomics . Thefocusofthisbookisuponeukaryotic,sexuallyreproducingdiploidspecies.Suchspecieshave multiplegenomes. Agenome isacompletesetofthechromosomesthatarenormallypassedon throughagamete.BecauseeukaryotesarosefromasymbioticfusionoftwoorthreedifferentPrecambrianlineagesofprokaryotes,eukaryoticcellstypicallycarrytwoorthreedifferentgenomes withseparateprokaryoticorigins(Koonin2010).Thefirstisthenucleargenome,whichevolved

Figure1.4 Aphotomicrographofthenucleargenomeof Drosophilabusckii asvisualizedthroughpolytene chromosomes.Polytenechromosomesareformedinsometissuesfromendoreduplication – repeatedrounds ofDNA(deoxyribonucleicacid)replicationwithoutnucleardivision.Homologousstrandssitsidebyside, allowingahigh-resolutionvisualizationofthenuclearchromosomes. Source: AndrewSyred/ScienceSource.

fromanArchaebacteriaancestor.Thisgenomeinmoderneukaryotesgenerallyconsistsofseveral linearanddistinctDNAmoleculescomplexedwithanumberofproteinsandotherchemicalsto formdistinctchromosomes.Thenucleargenomereferstoahaploidsetofthesechromosomes.

Figure1.4showsaphotomicrographofanucleargenomeofthefruitfly Drosophilabusckii.Fruit flies,likehumans,haveanXYsexchromosomesystem,sosomegenomesbearanXchromosome, andanalternativenucleargenomebearsaYchromosomeandnoXchromosome.Ychromosomes areoftenmuchsmallerinmanyspecies,including Drosophila andhumans.Insomespecies,sexis determinedbyfactorsotherthanchromosomes,suchasenvironmentalfactorsasillustratedin Figure1.2,inwhichcasethereisonlyonetypeofnucleargenome.Indiploidspecies,cellscarry twonucleargenomes:onederivedfromthefemalegameteandonederivedfromthemalegamete. Themodeofinheritanceoftheautosomalportionofthegenomeisbisexualandsexuallybalanced, butthesexchromosomesdisplayadifferentpatternofinheritance.Forexample,inanXYsystemof sexchromosomes,suchasthosefoundinhumansand Drosophila,theXchromosomeisinherited bisexually,butfemalesarediploidfortheXchromosomewhereasmalesarehaploid,resultingin haplo–diploidinheritance.TheYchromosomeisunisexualininheritance,beingpassedonfrom fathertoson,andishaploidinmales.

DuringthePrecambrian,certaineubacteriallineagesevolvedthecapacitytoutilizeoxygenfor aerobicmetabolismaftertheearlierevolutionofprokaryoticphotosynthesis.Photosynthesis resultedinthereleaseoflargeamountsofoxygenintoEarth’sancientreducingatmosphere.

Oxygenwasinitiallyadeadlypollutantformostlifeforms,butsomeprokaryoticlineagesadapted tothisnewenvironmentalfactorthroughtheevolutionofaerobicmetabolismthatallowedoxygen tobeusedasanefficientmeansofextractingenergyfromsugars.Someoftheseaerobicbacteria wereingestedbyArchaebacteriabutnotdigested,resultingultimatelyinasymbioticrelationshipin whichtheaerobicsymbiotsevolvedintotheorganellenowcalledmitochondria.Thishorizontal transferbetweenthesetwobacteriallineagesresultedintheeukaryoticcellwithbothnuclear andmitochondrialgenomes.Themitochondriaretainedamorebacteria-likegenomeconsisting ofasingle,circularpieceofDNA(Figure1.5).Overthecourseofevolution,manyofthegenes neededforaerobicmetabolismweretransferredfromthemitochondrialgenomeintothenuclear genome,butothergenesessentialforaerobicmetabolismareretainedinthemitochondrial genome.MitochondrialDNAisofteninheritedonlythroughfemalesinbisexualanimalsand displaysaclonal,non-recombininghaploidpatternofinheritanceratherthanabisexual,recombiningmode.

tRNA Leu

tRNA Ile tRNA Gln tRNA Met

tRNA Trp tRNA Ala tRNA Asn tRNA Cys tRNA Tyr

tRNA Leu tRNA Ser tRNA His

tRNA Ser

Figure1.5 Thehumanmitochondrialgenome.Thenamesandpositionsofthevariousgenesandcontrol elementsareindicatedonthecirculargenome.

Eukaryoticplantsacquiredanothergenome,thechloroplastgenome,throughendosymbiosis withaphotosyntheticcyanobacterialineage.Thechloroplastgenomeconfersuponplantstheabilityofphotosynthesis.Thechloroplastgenome,likethemitochondrialgenome,consistsofcircular DNA,althoughitistypicallylargerandcontainsmoregenesthanthemitochondrialgenome.Like themitochondrialgenome,thechloroplastgenometypicallydisplaysunisexualinheritancethatis effectivelyhaploid.Maternalinheritanceisthemostcommonpattern,butsomegroupsofplants displaybiparentalandpaternalinheritance(Birky2008).

Thefactthatautosomes,sexchromosomes,andorganelleDNAsoftendisplaydistinctpatterns ofinheritancehasmadegeneticsurveysoftwoormoreofthesetypesofDNAapowerfultoolin populationgeneticsandgenomics.Aswewillseeinlaterchapters,suchjointsurveysallowthe separationoftheroleofthesexes,coverageoflongerperiodsoftimeinreconstructingthepast, andtheexplorationofthebalanceofmanydifferentevolutionaryforcesactinginareproducing population.Thediversityinmodesofinheritancehastherebymadepremise1,DNAcanreplicate, morepowerfulthaneverinthegenomicera.

Genomesarethephysical–chemicalstructuresinwhichtheprocessesofmutationandrecombinationarecarriedout.Althoughmutationisrandomwithrespecttotheneedsoftheorganism, aspointedoutaboveandinFigure1.1,mutationishighlynonrandomatthegenomiclevel,afact oftenignoredinthepopulationgeneticliterature.Onecommonclassofmutationsiswhenasingle nucleotidemutatestoanothernucleotidestate.Itiscriticaltonotethatsuchsinglenucleotide substitutionsarechemicalprocesses,and,assuch,theprobabilityandtypeofsubstitutionagiven singlenucleotideislikelytoexperienceareinfluencedbythephysical–chemicalenvironment createdbythenucleotidessurroundingthetargetnucleotide(Sungetal.2015;Zhuetal.2017; Suárez-Villagránetal.2018).Inotherwords,singlesitemutationscanberegardedasphenotypes thatdependinpartupontheenvironmentalcontextasdeterminedbytheirnucleotideneighbors. Hence,singlenucleotidemutagenesisisactuallyamulti-nucleotideprocessthatcreatesmutational hotspotsinthegenome,sometimesforjustasinglenucleotidewithinamulti-nucleotidemutagenic motif,butsometimesforseveralnucleotidesinthemotifleadingtonotonlyahotspotbutclosely spacedmutationalclusters(Schrideretal.2011;Besenbacheretal.2016).Templetonetal.(2000a) exploredtheimpactofmutagenicmotifsuponthenucleotidevariationina9.7kbsegmentofthe LPL genein71individuals.Theydiscoveredthatabouthalfofthenucleotidesitesshowingvariationwereassociatedwithjustthreemulti-nucleotidemotifs,withCGdinucleotidesbeingthemost likelytoshowvariation(Table1.2).CGdinucleotidesarehypermutagenicwhenthecytosineis methylated,makingaCtoTtransitionhighlylikely,andmutabilitycanbefurtherenhanced bythe5 nucleotideadjacenttoaCGpair(Baeleetal.2008).Mutationalhotspotsassociatedwith

Table1.2 Thedistributionofpolymorphicnucleotidesitesina9.7kbregionofthehuman LipoproteinLipase geneovernucleotidesassociatedwiththreeknownmutagenicmotifsandallremainingnucleotidepositions.

Source: ModifiedfromTempletonetal.(2000a).

DNAsequencemotifsarenotlimitedjusttosinglenucleotidesubstitutionsbutarealsofoundfor indel(insertion/deletion)andcopy-numbermutations(KvikstadandDuret2014;Pressetal.2019).

MethylatedCGdinucleotidemutationsillustratethatnonrandommutagenesisnotonlycreates mutationalhotspotsinthegenomebutalsoincreasestheprobabilityof mutationalhomoplasy in whichtwoindependentmutationaleventsatthesamenucleotidesitecreatethesamenucleotide substitution.Suchhomoplasystrikesdirectlyatafundamentalconceptinpopulationgenetics –thedistinctionbetweenidentity-by-descentversusidentity-by-state. Identity-by-descent occurs whentwohomologouscopiesofaDNAregionareidenticalinnucleotidestatebecausenomutationsoccurredineitherDNAlineage,tracingbacktotheircommonancestralDNAmolecule(by definition,homologouscopiesaredescendedfromacommonancestralmolecule).Incontrast, identity-by-state occurswhentwohomologouscopiesofaDNAregionareidenticalinnucleotide stateregardlessoftheirmutationalhistory.Aswillbeseeninlaterchapters,muchofpopulation genetictheoryhasbeenformulatedintermsofidentity-by-descent,andthistheorycanbemost easilyappliedtodatawhenidentity-by-stateisequatedtoidentity-by-descent.HomoplasyunderminesthisassumptionbyallowingtwoidenticalDNAcopiestohavehadmutationsinoneorboth lineagesfromtheancestralmolecule.

Despitetheoverwhelmingevidencethatsinglenucleotidemutagenesisisamulti-nucleotide process,manypopulationgeneticmodelsandcomputersimulationstreateachnucleotideorindel asindependentmutationalunitsthatdonotdependuponthesequencecontext.Forexample,one ofthemostcommonlyusedmodelsofmutationinpopulationgeneticsisthe infinitesitesmodel thatassumesthateverymutationoccursatadifferentmutationalsitebecausetheprobabilityof mutationatanygivensiteissmallandtherearealargenumberofpotentialsites.Theinfinitesites modeleliminatesthepossibilityofmultiplehitsandhomoplasyandalwaysresultsinidentity-bystatebeingthesameasidentity-by-descent.Morecomplicatedmodelsofmutationarepossiblethat allowmultiplehitsandhomoplasy,aswillbegivenlaterinthisbook.Computerprogramssuchas ModelTestandjModelTest(Posada2008)assessthebestfittingmutationalmodelfromDNA sequencedataoveralargenumberofmutationalmodels.Mutationalhotspotscanbeincorporated intosomeofthesemodelsbyallowingratevariationacrosssites.However,noneofthemodelsin ModelTestincorporatetheimpactofmulti-nucleotidesequencecontextintothemutationalmodel. However,justbecauseamodelmakesunrealisticbiologicalassumptionsdoesnotmeanthatitis useless.Inthenextchapter,wewillpresenttheHardy–Weinbergmodel,abasicmodelofevolution thatmakesmanyunrealisticassumptionsyethasturnedouttobeextremelyusefulandyields resultsthataccuratelydescribemanypopulations.Thequestionis,therefore,notiftheassumptions ofamodelareunrealisticbutratherhowrobustarethemodel’spredictionstoviolationsofits assumptions.Unfortunately,becauseoftheanalyticaldifficultyandcomputationalcomplexity ofmultisitemutationalmodels,therehaveonlybeenafewexaminationsofrobustnesstodeviations fromthesimplermutationalmodels.Thefewstudiesthathavebeenperformedindicatethat directlymodelingmultisitecontextresultsinmuchbetterfitstosequencedatathanindependent-sitemodels,andthefailuretoincorporatemultisitecontextproducesbiasesandfalsepositives inphylogeneticinferenceanddetectingnaturalselection(SiepelandHaussler2004;Baeleetal. 2008;Lawrieetal.2011;BérardandGuéguen2012;ChachickandTanay2012;Bloom2014;KvikstadandDuret2014).

Manyofthestudiesmentionedaboveinvolvelongevolutionarytimescales,andafrequentjustificationfortheinfinitesitesmodelisthatmultiplehitsandhomoplasyarenotlikelyontheshorter timescalesrelevantformostpopulationgeneticstudies.However,thisargumentdoesnotseemto beborneoutbygenomicsurveys.Forexample,multiplehitsandparallelchangesminimally occurredat51%ofthe88singlenucleotidepolymorphisms(SNPs)inthe LPL geneinhumans

(Templetonetal.2000a),andextensivehomoplasyhasbeenobservedinotherregionsofthehuman genome(e.g.Fullertonetal.2000).Hence,theverygeneticvariationthatisthemainfocusofpopulationgeneticsisgreatlyinfluencedbymutationalprocessesthatviolatetheinfinitesitesmodel. Theseresultsareworrisomebecausemanyoftheanalysesandcomputersimulationsusedinpopulationgeneticsdependupontheinfinitesitesmodeloratleastindependentsitesmodelsofmutation;yet,therobustnessofthepredictionshasrarelybeenexamined.Afewstudieshaveexamined thequestionofrobustnesstothemutationalmodel,andmanypredictionsarenotrobust.Forexample,inferencesconcerningrecombination(Templetonetal.2000a),geneflow(StrasburgandRieseberg2010),populationstructure/demographichistory(Cutteretal.2012),andnaturalselection (Baeleetal.2008;Cutteretal.2012)canallbegreatlyaffectedbyviolationsofcommonlyused simplemutationalmodels.Giventheseresults,amorecompleteexaminationofrobustnesstosimplemutationalmodelsisgreatlyneededinpopulationgenetics.

Recombinationisanothermajorsourceofgeneticvariation,andittooisoftenconcentratedinto recombinationalhotspotsthatareassociatedwithspecificDNAsequencemotifs(Singhetal.2013; deMassy2014;Singhaletal.2015).Moreover,recombinationhotspotsarefrequentlyhotspotsfor mutationand geneconversion (Prattoetal.2014;Arbel-EdenandSimchen2019;Halldorsson etal.2019),aprocessrelatedtorecombinationthatplacesasmallsegmentfromonechromosome ontoahomologouschromosomeandtherebycancreateanewhaplotype.Forexample,30statisticallysignificantrecombinationandgeneconversionevents(aftercorrectionforfalsepositives) weredetectedinthe9.7kbregioninthehuman LPL gene.Alltheseeventsmappedtoasmall regionassociatedwithamicrosatellitesequenceinthe6thintron(Templetonetal.2000a),as showninFigure1.6,withnotasinglesignificantrecombinationorgeneconversioneventdetected anywhereelseinthis9.7kbregion.Justasmutationalhotspotscancreatefalseormisleadingsignalsforevolutionaryforcessuchasnaturalselection,socanrecombinationandgeneconversion hotspots(Bolívaretal.2019).

ThefactthatDNAsequenceinfluencesboththelocalratesofmutationandrecombinationatthe genomiclevelcreatesaninterestingtwisttopremise2inpopulationgenetics,namely,localmutationandrecombinationcanberegardedasagenomiclevel,inheritedphenotypethatispotentially responsivetonaturalselection.MartincorenaandLuscombe(2013)investigatedthepossibilitythat populationsmightevolvelowermutationratesatgenomicpositionswheremostmutationsare

Figure1.6 Recombinationandgeneconversioneventsina9.7kbintervalofthe LPL gene.Thehorizontalline ismapoftheregion,showingthepositionsofexons(E4throughE9)inthicklinesandintronsinthinlines.The numberofstatisticallysignificantrecombinationorgeneconversioneventsthatcouldhaveoccurredinan intervaldefinedbyadjacentsinglenucleotidepolymorphismpairsisplotted. Source: Basedondatain Templetonetal.(2000a).

deleteriousandincreasedmutationrateswheremanymutationsareadvantageous.Theyfound thatnaturalselectioncouldresultintargetedhyper-andhypomutation,withtheconditionsfavoringhypermutationbeingmorerestrictive.Livnat(2013,2017)hasalsoproposedmodelsofnatural selectioninteractingwithnonrandommutationandrecombinationatthegenomeleveltoproduce adaptiveevolutionarychange.Atfirstglance,theabilityofnaturalselectiontoadjustlocalmutationandrecombinationratesmayseemtocontradictourearlierconclusionthatmutationsarerandomwithrespecttotheenvironmentalneedsoftheorganism,asillustratedbythereplicaplating experimentshowninFigure1.1.However,thereisnothingLamarckianabouttheselectivemodels ofMartincorenaandLuscombe(2013)andLivnat(2013,2017)thatdealwiththeadjustmentof mutation rates throughordinarynaturalselectiononDNAsequencesandnotwiththeproduction ofa specific adaptivemutationinducedbyaspecificenvironmentalneed(theLamarckianmodel). Thesemodelsdoshowthatnonrandommutationandrecombinationatthegenomiclevelcanplay animportantroleinadaptiveresponse(Figure1.3)andthatthedetailsunderlyingpremise2are themselvessubjecttoadaptiveevolutionarychange.

Genomicsciencehasalsohadaprofoundimpactonourunderstandingofpremise3thatphenotypesariseoutoftheinteractionofgenotypesrespondingtotheenvironment.Thegenesinanyof thegenomesconstitutebiologicalinformationbutnotfunctionunlesstheyareexpressed.Whether agenecodesforaproteinorforafunctionalRNAmolecule(BonasioandShiekhattar2014;Lyu etal.2014),thefirststepingoingfromstoredinformationtobiologicalfunctionalityisthetranscriptionoftheDNAintoRNAbyRNApolymerases.The transcriptome referstothefraction ofthegenomethatisactuallybeingtranscribed,andthetranscriptomevariesoverdevelopmental stages,acrosscelltypes,acrossindividuals,andacrossmanyenvironmentalfactors.Thereisnota singletranscriptomeforaspeciesorevenanindividual,butmany,andall,arehighlycontext dependent.Theportionsofagenomethatarebeingtranscribedatagiventimeandcelltype areinfluencedbymanyfactors,includingthethree-dimensionalstructureofthegenomeinterms oftherelativepositioningofsequencesonthesamechromosomeandbetweenchromosomes (BouwmananddeLaat2015;BonevandCavalli2016),chromatinremodeling(Chambersetal. 2013),andDNAsequencessuchaspromoters,enhancers,silencers,responseelements,andinsulators.TheseDNAsequencesoftenhavebindingdomainsthatwhenboundtoaproteinorsome othermolecule(calledtranscriptionfactors)canactivateordeactivatethetranscriptionalfunction ofthepromoters,enhancers,silencers,etc.Thesebindingmoleculesthemselvesareofteninduced byvariousenvironmentalfactors.Environmentalfactorscanalsoinfluencehowthetranscribed RNAisprocessed,edited,andtranslatedintoproteinsandhowtheseproteinsaresometimesmodifiedpost-translationally.Hence,theenvironmentcanplayadirectroleinhowtheinformationin theDNAinfluencesphenotypes.

Manybindingdomainsarefoundin transposableelements (e.g.Cuietal.2011),segmentsof DNAthathavetheabilitytomoveormakecopiesofthemselvesatdifferentlocationsinthe genome.Transposableelements,alsoknownastransposons,oftenconstituteasizableportion ofthenucleargenomeineukaryotes,goingupto90%ofthemaizegenome(SanMigueletal. 1996).Whentransposonsbearingbindingdomainstransposetonewlocationswithinagenome, thereisthepotentialforbringinganewgeneintoanestablishedregulatorynetwork,therebyinducinggeneticvariationinthecoordinationofgene-networktranscriptionregulation.Moreover, manybindingdomainscanbindseveraldifferenttranscriptionfactors,andevenasinglemutation inabindingdomaincangreatlyalterthetranscriptionfactorsthatcaninfluencetranscriptionin theregioninfluencedbythedomain(PayneandWagner2014).Thisabilityofmutationtochange thearrayoftranscriptionfactorsthatwillbindaspecificdomainandthemovementofsuch domainsbytransposonscangeneratemuchvariationintranscriptionalregulatorypatterns.This

variationinturnconfersahighdegreeof evolvability (theabilitytobringforthnoveladaptations) uponthepopulation.Evolvabilityisalsoenhancedbythenonrandomnatureofmutationand recombinationinthemodelsofLivnat(2013,2017).

Anotherimportantaspectofthetranscriptomeis epigenetics,thedevelopmentandmaintenanceofheritablestatesofgeneexpressionpatternsthatdonotdirectlydependontheDNA sequenceandthataretypicallyreversible,ofteninresponsetoenvironmentalcues(Bonasio etal.2010).Epigeneticstatesarefrequentlycontrolledbychemicalmodificationsofhistonesin thechromatinand/orthemethylationofcytosinesatCGdinucleotides(RiveraandRen2013; Wonetal.2013).Thesechemicallymodifiedepigeneticstatesarestableyetreversibleandcan becopiedduringtheprocessofmitosisandtherebypersistovermultiplecellgenerationsand cansometimesbepassedonacrossgenerations(BoskovicandRando2018;Zhangetal.2018). ThesechemicalmodificationsarecontrolledbyenzymesandnoncodingRNAs(FaticaandBozzoni 2014),whichinturnarecodedforingenes.Geneticvariationinthesegenesinfluencesepigenetic phenomena(Klironomosetal.2013;Kilpinenetal.2013),sotheepigenome,includingitssensitivitytoenvironmentalcues,isitselfaphenotypethatisinfluencedbyunderlyinggeneticvariation, andhencesubjecttochangebynaturalselectionasshowninFigure1.3.

Asillustratedbythediscussionabove,theDNAinthegenomeis not astaticblueprintoflifebut ratherisadynamicentitythatisconstantlychanginginresponsetotheenvironmenttoproduce phenotypesandwhosedynamicattributesaresubjecttoevolutionarychange,includingadaptation.Hence,genomicstudiesstronglyreinforcethevalidityofpremise3inpopulationgenetics anditsintegrationwiththeotherpremises,asshowninFigure1.3.

ModelingEvolutionandtheHardy–WeinbergLaw

Throughoutthisbook,wewillconstructmodelsofreproducingpopulationstoinvestigatehowvariousfactorscancauseevolutionarychanges.Inthischapter,wewillconstructsomesimplemodels ofanisolatedlocalpopulation.Thesemodelseliminatemanypossiblefeaturesinordertofocusour inferenceupononeorafewpotentialmicroevolutionaryfactors.Themodelswillalsoprovide insightsthathavebeenhistoricallyimportanttotheacceptanceoftheneoDarwiniantheoryofevolutionatthebeginningofthetwentiethcenturyandareofincreasingimportancetotheapplication ofgeneticstohumanhealthandothercontemporaryproblemsinthetwenty-firstcentury.

HowtoModelMicroevolution

Givenourdefinitionthatevolutionisachangeovertimeinthefrequencyofallelesorallelecombinationsinthegenepool,anymodelofevolutionmustincludeattheminimumthepassingof geneticmaterialfromonegenerationtothenext.Hence,ourfundamentaltimeunitwillbethe transitionbetweentwoconsecutivegenerationsatcomparablestages.Wecanthenexaminethe frequenciesofallelesoralleliccombinationsintheparentalversusoffspringgenerationtoinfer whetherornotevolutionhasoccurred.Allsuchtrans-generationalmodelsofmicroevolutionhave tomakeassumptionsaboutthreemajormechanisms:

• Mechanismsofproducinggametes

• Mechanismsofunitinggametes

• Mechanismsofdevelopingphenotypes

Inordertospecifyhowgametesareproduced,wehavetospecifythegeneticarchitecture. Geneticarchitecture isthenumberoflociandtheirgenomicpositions,thenumberofalleles perlocus,themutationrates,andthemodeandrulesofinheritanceofthegeneticelements. Forexample,thefirstmodelwewilldevelopassumesageneticarchitectureofasingleautosomal locuswithtwoalleleswithnomutation.Thegeneticarchitectureprovidestheinformationneeded tospecifyhowgametesareproduced.Forasingle-locus,two-alleleautosomalmodelwithnomutation,weneedonlytouseMendel’sfirstlawofinheritance(thelawofequalsegregationofthetwo allelesinanindividualheterozygousatanautosomallocus)tospecifyhowgenotypesproduce gametes.Othersingle-locusgeneticarchitecturescandisplaydifferentmodesofinheritance, includingX-linkedloci(withahaplo–diploid,sex-linkedmodeofinheritanceinorganismswith anXYsex-determiningsystem),Ychromosomalloci(withahaploid,unisexualpaternalmode ofinheritanceinorganismswithanXYsex-determiningsystem),ormitochondrialDNAand

PopulationGeneticsandMicroevolutionaryTheory,Second Edition.AlanR.Templeton. ©2021JohnWiley&Sons,Inc.Published2021byJohnWiley&Sons,Inc. Companionwebsite:www.wiley.com/go/templeton/populationgenetics2