Introduction

Coastal forces came into existence because of the advent of powerful yet compact internal combustion engines beginning early in the twentieth centur y. These same engines made aircraft possible, for the same reason: they offered a great deal of power at a limited cost in space and weight. Small boats and, for that matter, small bombers, could inflict lethal damage on large ships thanks to the advent of torpedoes, which made minimal demands on anything delivering them This new reality was demonstrated in 1917 when an Italian motor torpedo boat penetrated an Austrian base to sink the pre-dreadnought Wien; the following year the Italians sank the dreadnought Szent Istvan at sea Having sunk smaller German ships during the war, in 1919 British motor torpedo boats (CMBs –

Coastal Motor Boats) seriously damaged Russian (Bolshevik) warships in the Baltic, ending a threat to Finland Modern missilearmed fast attack craft are the direct descendants of the torpedo boats which fought in both World Wars

World War I motor torpedo boats in turn were descended from nineteenth centur y steam torpedo boats, which first exploited the torpedo as a ship-killing weapon which did not require a massive warship to wield it Internal combustion made for much more

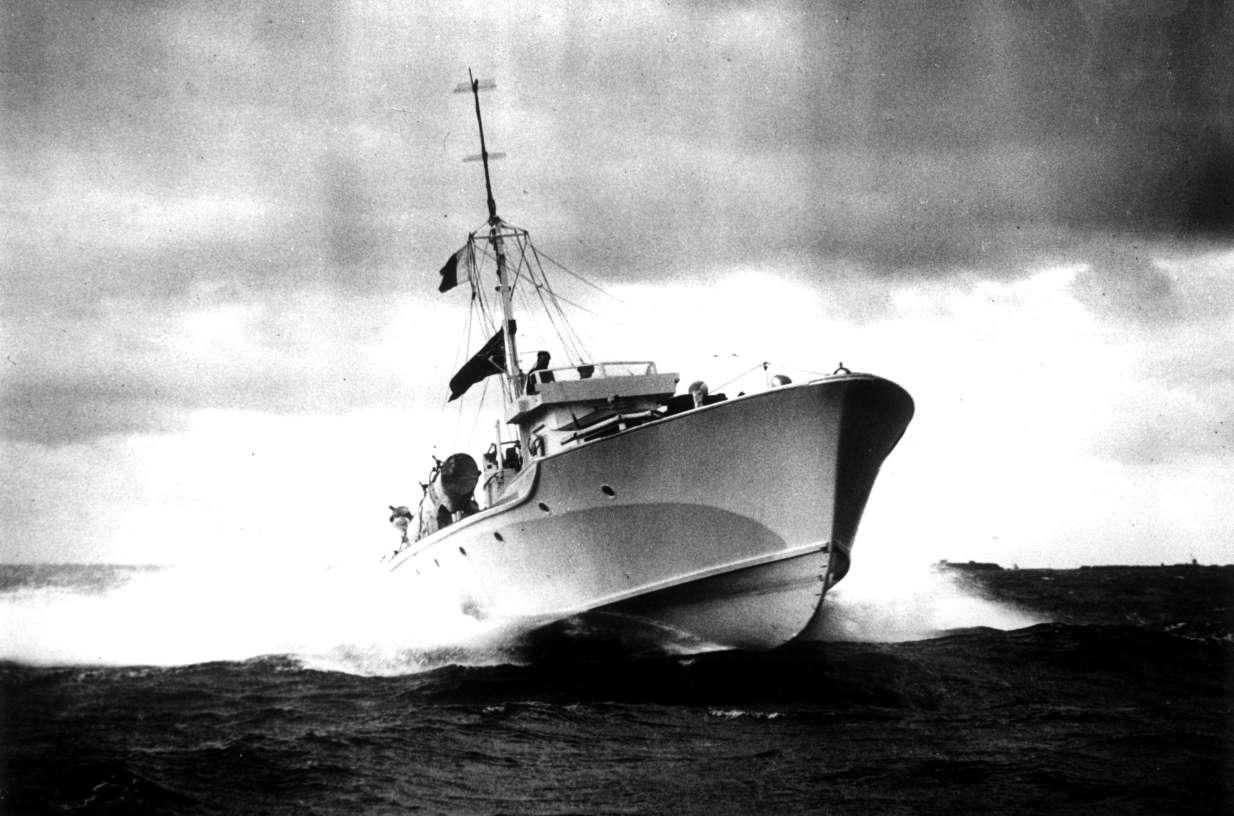

The classic image of British World War II coastal forces: A Vosper MTB planing at speed Note the scallop in her deck line for the torpedo tube

power in a small volume, hence a smaller higher-performance boat with a much smaller crew That possibility was obvious to several pre-1914 inventors, but no navy picked up the possibility, though many already operated steam torpedo boats. However, during the war Britain, Italy, and Germany all deployed what would later be called motor torpedo boats. Britain and Italy employed them operationally

The new boats depended on their speed, manoeuvrability, and small size for sur vival and effectiveness in the face of enemy defences. Speed in turn demanded not only high power but also special hull forms A conventional (displacement) hull requires enormous power to reach high speed, which is defined in terms of the square root of the ship’s length compared to her speed Anything above a ratio of 1 is fast; therefore, for a hundred-foot boat, anything much over 10 knots is fast This reality comes from the fact that a ship supported by her buoyancy generates waves as she moves through the water, pushing it aside To run much faster, the ship or boat needs either an extraordinar y amount of power or else a different way of supporting herself in or above the water By 1914 the different ways on offer were hydrofoils (in effect, under water wings which would lift the craft clear of the water) and planing Hydrofoils remained promising but impractical until well after World War II, despite many experiments.

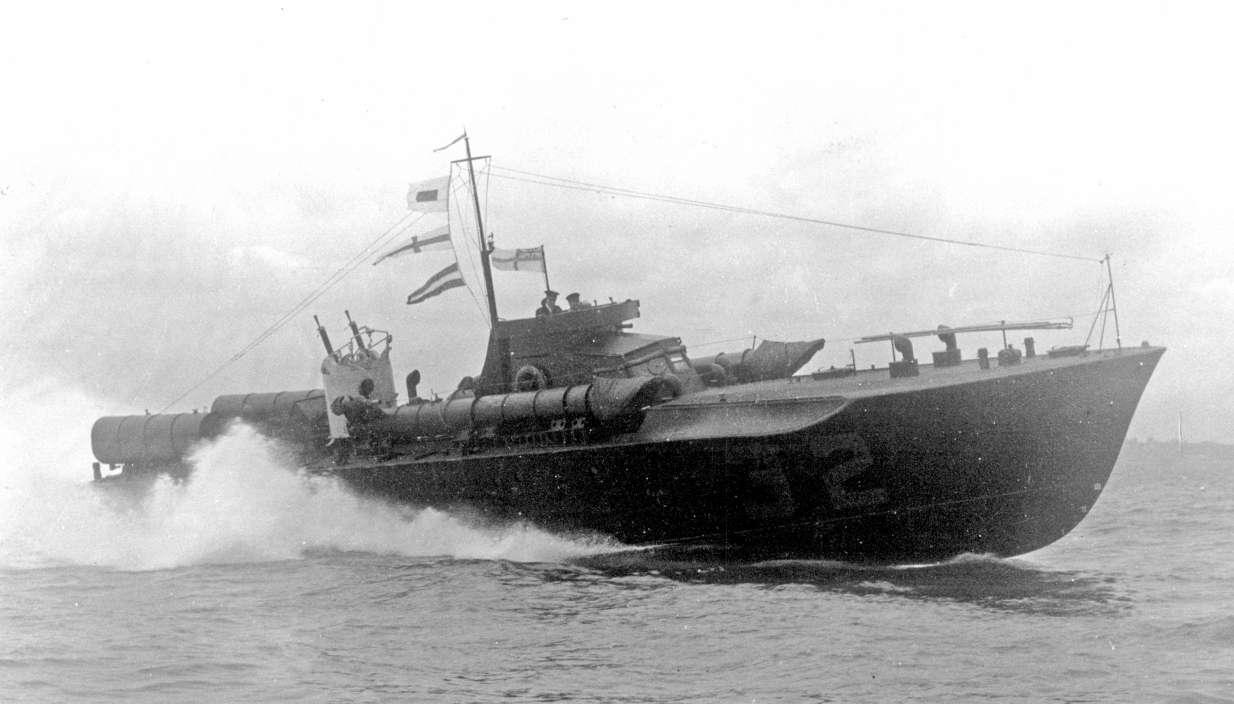

A 40ft Coastal Motor Boat running trials, with the shipyard personnel riding in the empty torpedo trough Its diminutive size is evident

That left planing: at high speed a boat with a flat bottom could ride on the surface of the water, with the only major source of resistance the friction between her bottom and the surface. Planing, like hydrofoiling, was generally attributed to dynamic rather than buoyant lift By dramatically reducing resistance, it enabled a small boat with powerful engines to achieve remarkable speed. How well she could be supported depended on her speed and on the area of the planing surface. Typically, hydrodynamic forces that the boat generates at high speed push her bow out of the water and the chines under the boat help push the stern up, so that at maximum speed as much as half the hull might be out of the water This possibility was discovered before the war for racing boats, and it was employed by the British CMBs and probably by other motor torpedo boats. To plane, a boat had to lift and break the surface tension which kept her in the water That was much the problem faced by a seaplane or floatplane. In each case, as of World War I, the planing surface ended in a step intended to break the hull free

The catch was that the water had to be quite calm, because waves tended to break up planing action and drastically slow the boat In rough water, moreover, the step caused pounding and the flimsy lightweight hull could break up. Too, the limited planing surface available could support only ver y limited weight Nor could the weight var y ver y much, so fuel stowage had to be quite limited. In contrast to a planing boat, a conventional hull could easily absorb additional weight by sinking somewhat deeper into the water

The British World War I Coastal Motor Boat (CMB) was based on pre-war Thornycroft racing craft with planing hulls (see drawing B 1). They were conceived as a way of attacking a German High Seas Fleet which exerted considerable effect on the war at sea without accepting action with the British Grand Fleet. In this sense the CMBs were an alternative to torpedo bombers, either seaplanes or, at the end of the war, carrier aircraft. Both used much the same engines and the same fuel Neither was expected to cross the North Sea to the targets; both needed tenders or carriers to get them within range of their targets. In the case of CMBs, the carriers could be either freighters or light cruisers carr ying the boats in their davits. The war ended before either carrier bombers or CMBs could attack, but the CMBs came close: an October 1918 raid was called off due to bad weather.

For the Royal Navy, the end of World War I dramatically changed the strategic situation and made CMBs far less attractive. The most likely future naval enemy was Japan Despite an alliance with Britain, during the World War the Japanese had supported an ‘Asia for the Asians’ policy (meaning ejection of European colonies) in support of their own desire to create an Asian empire. The British had vital economic interests in the Far East, not only in their colonies but also in China, from which the Japanese wanted to expel them They also had important interests in Thailand, which the Japanese eventually turned into a satellite. The British Dominions in the Pacific, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, all

feared Japanese expansionism When Admiral Jellicoe toured the Empire in 1919–20 to advise on naval defence, his effort was directed entirely against Japan With Britain still tied to Japan by an alliance, the Admiralty publicly disowned Jellicoe’s statements, but its internal documents show that it agreed with him: the major threat the Empire faced came from Japan. By way of contrast, the British saw no apparent threat inside Europe at all comparable to that the Germans had posed before 1914. Nor was there any sense that the United States, the other remaining major seapower, was a realistic threat.

Jellicoe and the Admiralty saw a possible war in the East as a replay of the naval side of World War I over much greater distances, the fleet base at Singapore playing the role of Scapa Flow. If the blockade imposed on Germany had been decisive (as the Admiralty believed), Japan would be far more vulnerable to similar action, a fleet at Singapore blocking the trade routes through the Straits of Malacca, while British cruisers blocked trade from the Americas. The Japanese, like the Germans, would face the choice of either fighting (and, the British hoped, losing) a fleet engagement or being strangled Losing the fleet engagement would leave Japan open to strangulation.

The question was whether the Japanese could upset the strategy by seizing the fleet base at Singapore. The British could not base a fleet there in peacetime, due to the lack of infrastructure and the perceived impossibility of moving families there permanently. Thus, in the 1920s the main British fleet was based at Malta, the intent being to move it East if war seemed to loom. It was assumed that any Far Eastern war would be preceded by a period of

increased tension during which the fleet could move, arriving before war actually broke out. Once in place, the fleet itself would guarantee the security of its base, since it would be able to engage any Japanese force before it could attack the base. Hong Kong would act as a for ward base

These assumptions shaped the fleet built up during the 1920s and the ver y early 1930s They explain why the Royal Navy of that era abandoned the CMBs. During World War I, CMBs had barely been able to get close enough to the German fleet base at Wilhelmshaven. It must have seemed most unlikely that CMB carriers would be able to get close enough to Japanese bases in the face of air and other reconnaissance. In that case the remaining CMB role would probably be the local defence of key bases: Singapore and Hong Kong. However, through the 1920s it was assumed that local defence would be relatively unimportant, as it was assumed that the main fleet would arrive before war broke out It also seemed that the alternative to the CMB, the new carrierbased torpedo bomber, was preferable Carriers could operate over far greater distances, and they could launch torpedo bombers in weather in which CMBs could neither be launched nor operated The CMBs would be superior to carrier aircraft only at night.

With the defeat of Germany and Austria-Hungar y, there were no major maritime enemies in Europe: France and Italy were both allies The new Soviet Union was potentially hostile, but its fleet was inactive and considered ineffective.

The shift in emphasis from the relatively short distances of the North Sea to the vast ones of the Far East placed a premium on new warship construction, as the distances made existing ships largely obsolescent. Moreover, money was extremely tight. In 1925 the Admiralty decided to cease further CMB development and to close the base at Haslar, retaining a few CMBs in reser ve, attached to other establishments at Portsmouth. Thornycroft, which had

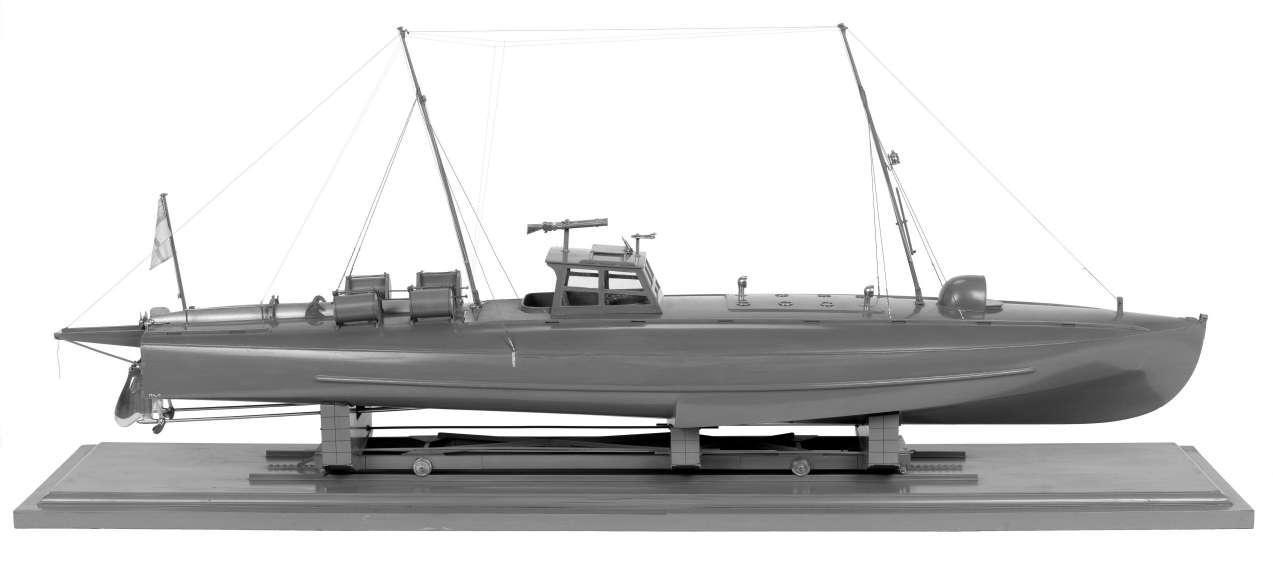

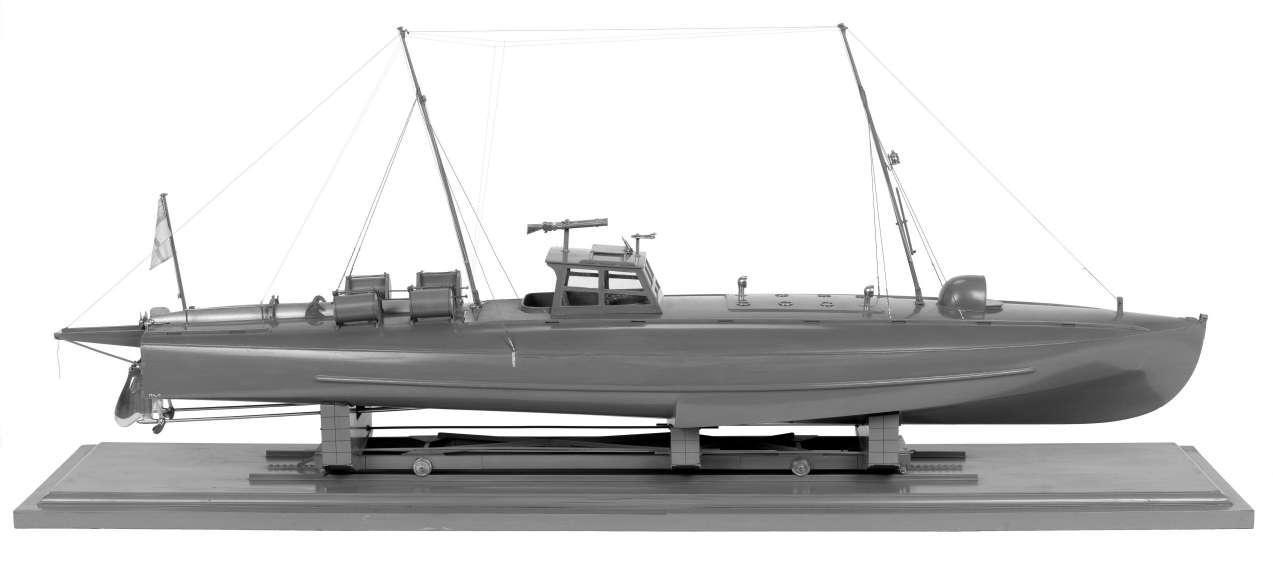

Builder’s model of the larger 55ft Coastal Motor Boat, showing the form of the stepped hydroplane-derived hull (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London F7764-1)

developed the war time CMBs, continued building them in improved form for foreign navies, nearly all of them 55-footers: China (8), Greece (3), Finland (2 plus 2 built in-countr y), France (2), Japan (4), Netherlands (4), Philippines (5), Siam (5), Spain (six 40-footers), Sweden (2), the United States (3), and Yugoslavia (2) Most of these craft were built in the 1920s; by the mid-1930s Thornycroft was considering developing a new larger design, a few of which ended up in Royal Navy ser vice.

It seems to have been common knowledge that Italy was developing substantially more capable craft. Germany was also building motor torpedo boats In 1931 Vice Admiral Backhouse (Controller) suggested building one CMB a year to maintain design expertise, on the theor y that if war broke out such craft would be wanted. It would be worthwhile to keep a current design ready for mass production Engineer-in-Chief strongly supported the proposal, as it would stimulate progress in building high-speed engines and also help British builders compete with their foreign rivals. It also seemed that boats were needed to gain experience in firing torpedoes at high speed Given financial stringency, the

proposal was stretched to one ever y four to five years and then to one ever y seven years Meanwhile the RAF was buying fast boats for air-sea rescue and to work with its seaplanes. Unlike CMBs, they had to be able to run at high speed even in moderately rough water The RAF had tried and rejected CMBs because they could not run out to sea in mildly rough weather. About 1931 the British Power Boat company (headed by Hubert Scott-Paine) won an RAF contract for a 24-knot seaplane tender (the 37ft 6in ST 200 series). Scott-Paine had previously been associated with the Supermarine aircraft firm when it specialised in flying boats (hence its name), so he had experience with fast watercraft – that is, with flying boats running up to speed before taking off. Although too small and too slow for torpedo boat work, the ST 200 series gave the firm its

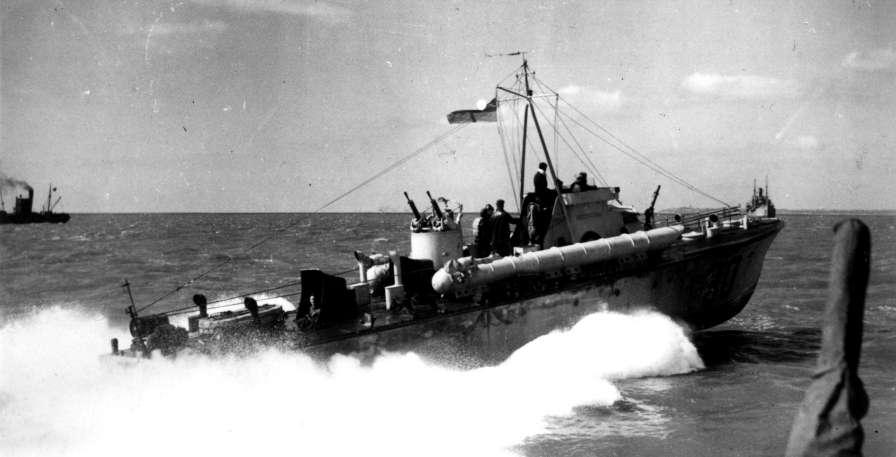

British Power Boat MTBs at sea off Felixstowe in mid-1940, with MTB 18 in the foreground, showing their quadruple Lewis guns abreast their bridges, and, on MTB 18, one of the torpedo-launching gantries aft (it would be folded back over the stern to launch a torpedo)

initial experience in building large fast militar y boats. The firm also built fast target boats for the RAF Scott-Paine designed and built an aluminium racing boat, Miss Britain II, to compete for the 1933 Harmsworth Trophy. It was powered by the Napier Sea Lion engine, an adapted aircraft engine which was to power the first British Power Boat MTBs a few years later.

In 1933 someone in the Admiralty suggested buying a boat suitable for torpedo work, testing it, and then selling it to the RAF. Air Ministr y reaction was lukewarm, but the important point was the Admiralty’s recognition that the technology being developed for the Air Ministr y was the best gateway to developing a future

displacement.

The Admiralty did buy some fast (in terms of length) craft as ships’ boats, but they were far smaller and slower than torpedo boats had to be Presumably they provided experience with the hard-chine hulls which would characterise the new generation of motor torpedo boats

The main potential competitor to British Power Boat was Vosper (headed by Commander Peter du Cane, who was also its chief designer) Other potential builders – Thornycroft, J S White and the yacht builders Camper & Nicolson – seem not to have figured prominently in any prospective torpedo boat program

Backhouse’s comment seems to reflect a demand by the British Government that the Admiralty shift its concentration away from war with Japan. The shift in emphasis seems to have been triggered by a mischievous request by Winston Churchill As Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1929, he questioned the Admiralty’s program, which had been based on the needs of a war against Japan He got the Foreign Office to state that war with Japan was extremely unlikely, hence that he could reject Admiralty demands, for example for spending to complete the Singapore naval base. It is impossible to say how seriously the Admiralty took the shift dictated by the Foreign Office.

British naval strategists got their revenge on the Foreign Office by pointing out that obligations it had cheerfully assumed carried potential risks of war. Some years earlier the British had signed the Locarno Treaty guaranteeing the borders of a largely disarmed Germany. That had seemed a reasonable way of encouraging Germany to stay disarmed The Admiralty pointed out that Britain was pledging to fight any attempt by France or Italy to challenge German borders; Admiralty papers of the time include analyses of the vulnerabilities of both those countries to naval pressure. In 1931 the First Sea Lord warned darkly of ‘ pre-war ’ thinking in Europe which might trigger just such a war.

The ‘Locarno war ’ problem suggested that the Royal Navy should be looking much more closely at what it would need to fight in European waters By this time the Germans were showing less and less willingness to stay disarmed; at a League of Nations conference they demanded parity with other European powers. On

the other hand, when it contemplated further arms control measures, the British Government still concentrated on the Japanese problem. It may have been assumed that a fleet sufficient to fight a Far Eastern war could easily handle the much weaker fleets of various European powers

The Foreign Office argument that the Far East could be neglected collapsed in 1932 Having already seized the Chinese province of Manchuria the previous year, the Japanese invaded North China and horribly mistreated British civilians there Japanese hostility was now obvious; the era in which a Japanese attack on the British Empire was unthinkable was clearly over The British government began to rearm. Symbolically, it turned the committee charged with developing disarmament proposals into t h

deficiencies in British defence The naval building budget grew, but it did not include any coastal craft. It was oriented towards the Far East and the long-range ships needed there The Admiralty position was that Japan was a current threat, whereas a rising Germany was a

impossible for Britain to build a fleet sufficient to fight both in the Far East and in European waters, particularly while arms control treaties were still in force (as they were through 1936) That was aside from the serious loss of British naval industrial strength due to the treaties agreed from 1921 onwards

Ironically, the first big crisis to erupt after reorientation was much like the one the Navy had been considering in 1931 Britain was a member of the League of Nations, which indirectly imposed its own substantial obligations After Italy invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935, the League imposed sanctions. For a time it appeared that the Royal Navy would have to enforce them (particularly sanctions on oil) by fighting the Italians. A horrified First Sea Lord wrote that such action upended the previous assumption that any war would follow a period of heightened tension during which the British could mobilise Although war with Italy did not break out, Italy could not be counted on as an ally, or even a friendly neutral, in the future. Moreover, with the rise of the revived German navy under Hitler, the British had to face the possibility of more or less simultaneous war or crisis in both the Far East and Europe They had sized their fleet for a one-ocean war in the Far East. Even though Italy was relatively weak, the build-up in the Mediterranean had required the Admiralty to bring in many ships from other stations, including the Far East (China Fleet). If war could come with little or no warning, it was impossible to assume that the main fleet could reach Singapore before the outbreak Local defence was essential

The Italians had a large force of motor torpedo boats, which they called MAS (Motoscafi Anti-Sommergibili, to some extent a World War I cover designation). Their modern boats could operate well out to sea, in rougher weather than the CMBs could have tolerated. The British found themselves spending considerable sums to keep them from penetrating fleet bases at Malta and

Alexandria as well as other important Mediterranean ports. Ships were modified to deal with MAS attacks in the open sea The MAS threat also helped justify increased interest in mounting 2pdr multiple pom-poms on board ships. The requirement that the King George V class battleships be able to fire right ahead at zero elevation is generally associated with the MAS threat.

By this time lightweight engines were considerably more powerful than they had been during World War I, with typical

o u t p u t s o f u p t o a b o u t 1 0 0 0 H P Gi ve n s u c h e n g i n e s , a substantially larger boat with hard chines (flat surfaces) on its bottom could plane in smooth water (like a CMB) However, it could also ride out rougher weather (which a CMB could not). This would be a semi-displacement hull, with the advantage that it could carr y a larger variable load, hence more fuel – for much greater range

New Motor Torpedo Boats

At the end of 1935 six boats, the first since 1918, were added to the new construction program By this time boat technology had

improved to the point where they could attack a fleet at sea. The only way to gauge what defence the fleet needed was to operate British boats comparable to the Italian ones. The new boats were called Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs) rather than CMBs, probably to distinguish them clearly from their ancestors Unlike CMBs, they could run at speed in the open sea, albeit only in good weather.

Apart from Thornycroft, in the early 1930s no British builder was selling motor torpedo boats to foreign navies. The only company selling stepless planning craft to the British Government was Scott-Paine’s British Power Boat company. During 1935 ScottPaine offered the Admiralty a 60ft hard-chine MTB powered by three 600 HP Napier Lion engines, carr ying two 18in torpedoes over the engine room As in the World War I CMB, the torpedoes would be launched backwards with propellers aft, the boat accelerating out of the way Speed at ser vice displacement (22 tons)

British Power Boat 60ft MTBs of the 1st MTB Flotilla escor t the royal family on the Thames The occasion was the opening of the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich on 27 April 1937

was 33kts (boats attained 35kts to 37kts on a lighter trial displacement). Although the Admiralty paper amending the 1935 program was dated December 1935, the first two were ordered on 27 September, followed by four on 19 October 1935 (see B 2)

T h re e m o re we re o rd e re d o n 7 De c e m b e r 1 9 3 6 ( 1 9 3 6 / 3 7 program), and another nine (MTB 10–18) on 11 March 1938, as part of the 1937/38 program. There was some renumbering, so that the designations MTB 1, MTB 7, and MTB 13 applied to several boats at different times. The three flotillas of these boats were the only British MTBs in commission on the outbreak of war in September 1939. Although they were good seaboats (they went to Malta on their own bottoms), they were not considered capable of operating anywhere well out to sea. Their hulls were considered too lightly built, requiring considerable repairs after brief ser vice As a rough indicator of fragility, in 15 months in the Mediterranean up to 31 March 1939, the Scott-Paine boats required, on average, 76 days of refits and 26 days in dockyard hands. Furthermore, the torpedo discharge over the stern was found

ver y unsatisfactor y As built, boats were armed with two quadruple 0.303in Lewis guns, one on the hatch to the crew space well for ward, and one on the steering compartment hatch well aft This a r r a n

unacceptable in ser vice. In at least some cases, such as MTB 2 and MTB 12, boats operated with only their for ward set of guns (in MTB 2 a dinghy occupied the after position). In most or all cases the guns were moved to tubular supports abreast the bridge Later boats had machine guns in much the same position. Early boats seem to have had twin rather than quadruple Lewis guns; later boats such as MTB 14 had their Lewis guns abreast their bridges, arranged 2 x 2

When the 60ft boats were built, there were still strong advocates of the earlier Thornycroft stepped-hull type used in World War I CMBs and exported since. These boats were several knots faster, but officers who had made coastal passages in both types of boat generally considered the stepped boats too ‘hard riding’ to be used in a seaway However, Thornycroft continued to sell stepped-hull boats, and during the early part of World War II the Admiralty bought several.

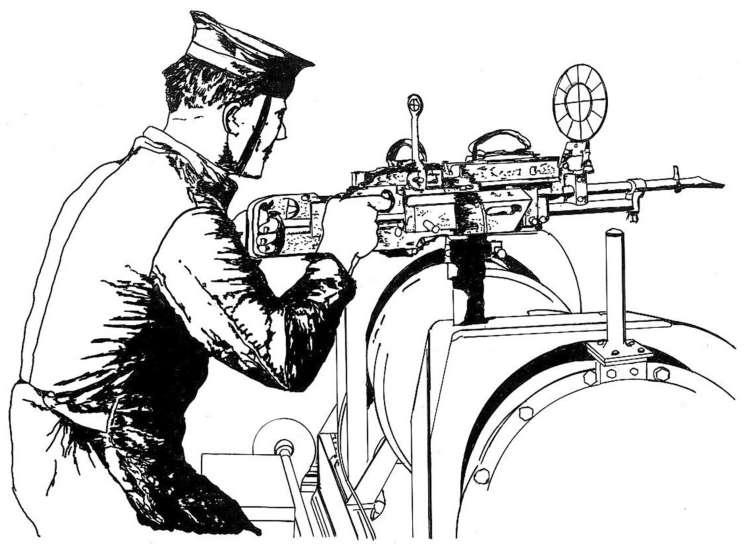

Quadruple Lewis guns on board a 60ft British Power Boat MTB, 1940

The first six Scott-Paine boats formed the 1st Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla for the Mediterranean; the next six went to Hong Kong as its mobile defence. The third flotilla had been earmarked f

, presumably partly because it was assumed that twelve boats were needed for an effective attack on a fleet at sea Two smaller boats built for China but interned in Hong Kong were assigned to

Si n g a p o re T

understanding that local defence was necessar y, at the least to deal with the possibility of a sudden outbreak of war It was apparently impossible to provide Hong Kong with permanent land defences, as was being done at Singapore Furthermore, the situation of Hong Kong became far more precarious once the Japanese invaded China in 1937, seizing much of the Chinese coast

The Mediterranean and Far Eastern roles were connected, in that the recent crisis had shown that it was unlikely that the main fleet would get to the Far East before war broke out. Hence there was an increased need for local defence. Early trials showed that the British Power Boat craft were too small and that their torpedo launching arrangements were unacceptable. In the Mediterranean, they could not make sufficient speed at sea to get into position to attack the fleet. S

Commander Peter du Cane, built a 68ft boat as a private venture

MTB 22 as launched, 3 April 1939, showing her large auxiliary fuel tanks abaft her torpedo tubes and her two hand-operated machine guns, presumably quadruple Vickers GOs. The dinghy aft was soon replaced by a Carley float

in 1935–36. On his own initiative du Cane arranged to import the best current motor boat engine, the Italian-made 1150 BHP IsottaFraschini, supplemented by two Ford V-8s for silent approach at low speed. These engines were well-liked. From the Admiralty constructors ’ point of view, the most important point was the hull structure, using widely-spaced mahogany frames with intermediate bent frames On trials the bottom of the boat pulsated at high speed, showing that it was not strongly enough supported; du Cane had to add more mahogany frames The hull structure was further modified after the Admiralty bought this boat, and it was gradually strengthened in wartime production boats

Initially the boat had a torpedo tube penetrating its stem (and a stern trough), both of which were considered unsatisfactor y HMS Vernon designed loose-fitting torpedo tubes which fired for ward, angled outboard They became standard in later British motor torpedo boats. Du Cane also imported Swiss Oerlikon 20mm automatic cannon, two of which were mounted sided, near amidships. They were in Swiss-developed power (ie, stabilised) mountings with joystick control At this time the Royal Navy had not yet adopted the Oerlikon Compared to the Scott-Paine boats, Vosper’s was considerably faster, achieving 43.7kts on trial. Continuous rated speed at 31 tons displacement was 33 5kts

The Admiralty bought the private-venture boat as MTB 102, the prototype of later Vosper boats (numbers over 100 were initially reser ved for experimental craft). It ordered four Vosper boats on 15 August 1938 under the 1938/39 program (MTB 20–23) They had the same three Isotta-Fraschini engines as the private venture boat, but were slightly longer (71ft 9in overall rather than 68ft) They were designed for 41kts and were rated at 42.5, with a maximum seagoing speed of 40kts About 300 Vosper boats had been built by the end of World War II: 127 in Britain and another 164 in the United States, including 100 for the Soviet Union Remarkably, the d e s i g n m a i n t a i n

considerable increase in weight and change of power plant The 1938 boat displaced 35.8 tons and had a maximum rated speed of 44.4kts. The 1943 version displaced 44.4 tons, its militar y load having increased by 60 per cent Although propulsive power increased by 9 per cent, maximum speed fell only to 40.5kts. At the end of the war displacement was 48 8 tons and maximum speed had fallen to 36kts.

Shortly after MTB 102 was built, British Power Boat built its own new prototype, a 70-footer it later called the Private Venture (PV or PV-70), which it demonstrated early in 1938 Like the Vosper boat, it was considerably larger and more robust than the 60-footers It had a distinctive hull form, with a low chine, a ver y bluff bow (to lift it onto the plane), maximum beam well for ward, and a moderate transom The sheer line, which Scott-Paine called a whaleback, had a hollow at mid-length and a low stern.

Compared to the Vosper boat, Scott-Paine’s had a better f r a m i n g s y s t e m u s i n g c l o s e l y - s p a c e d t r a n s v e r s e f r a m e s a n d numerous stringers. However, it had a light bottom (1/4in less

thickness than Vosper’s) and light sides, both of which gave trouble in ser vice On comparative trials, Scott-Paine’s boat was drier but the Vosper boat felt stronger and seemed less likely to suffer structural damage in ser vice. Powered by three marinized Merlin aero-engines, this boat achieved 44 4kts; claimed continuous speed was 40.5kts.

Scott-Paine won no MTB orders in the 1939 program, but he persuaded the US Elco company to licence-build his PV-70 design for whom British Power Boat built a prototype This boat won a US swim-off competition and the US Navy bought the PV itself as its PT 9; on 11 March 1941 it became the British MTB 258, having been transferred under the new Lend-Lease program. Elco then built large numbers of similar boats for the US Navy, at least initially under licence, and later to somewhat modified designs. The Royal Navy received some under Lend-Lease In May 1940 Scott-Paine set up the Canadian Power Boat Company with a yard

This Vosper MTB was sold to Romania Her finish contrasts with the drab appearance of war time British craft

at Montreal and the original PV-70 demonstrator was shipped to Canada as a production prototype; it became the Royal Canadian Navy’s CMTB 1. The PV hull form was retained in all later boats built by British Power Boat for the Admiralty up to the 71ft 6in MGBs, in which the hull structure was greatly strengthened in a joint effort by British Power Boat and the Admiralty.

British Power Boat exported versions of its PV The Dutch bought one boat (their TM 51) and ordered more (TM 52–70) from their own yards The Germans seized TM 54–61 incomplete and finished them to a modified design. The Dutch also sold an export version, of which three building for Bulgaria were seized when the Germans occupied the Netherlands. The Germans completed them, reportedly powering them with Merlin engines from crashed British aircraft. Also building in 1940 were three more boats on order for Romania The British sold three early Vosper MTBs to Romania as replacements.

When he was building the PV in 1938, Scott-Paine was told by E i i Chi f th t f t MTB ld b p d b

1000 BHP Paxman diesel. Fortunately, he was sceptical. In May 1939 he met the Paris representative of the US Packard company, who had been told that a British boatbuilder wanted to buy 100 engines. He offered a 1200 BHP boat engine of a type previously used in racing This engine was already in limited production for experimental US MTBs. This was when Scott-Paine and Elco brought a PV to the United States to compete in the US Navy’s ‘Plywood Derby’. During 1940, Packard produced 149 engines, 81 of which went into US PT boats, the rest being divided between the United Kingdom and Canada. They embodied modifications Scott-Paine suggested on the basis of his adaptation of the Merlin aero-engine to the PV. The British received 4686 Packard engines

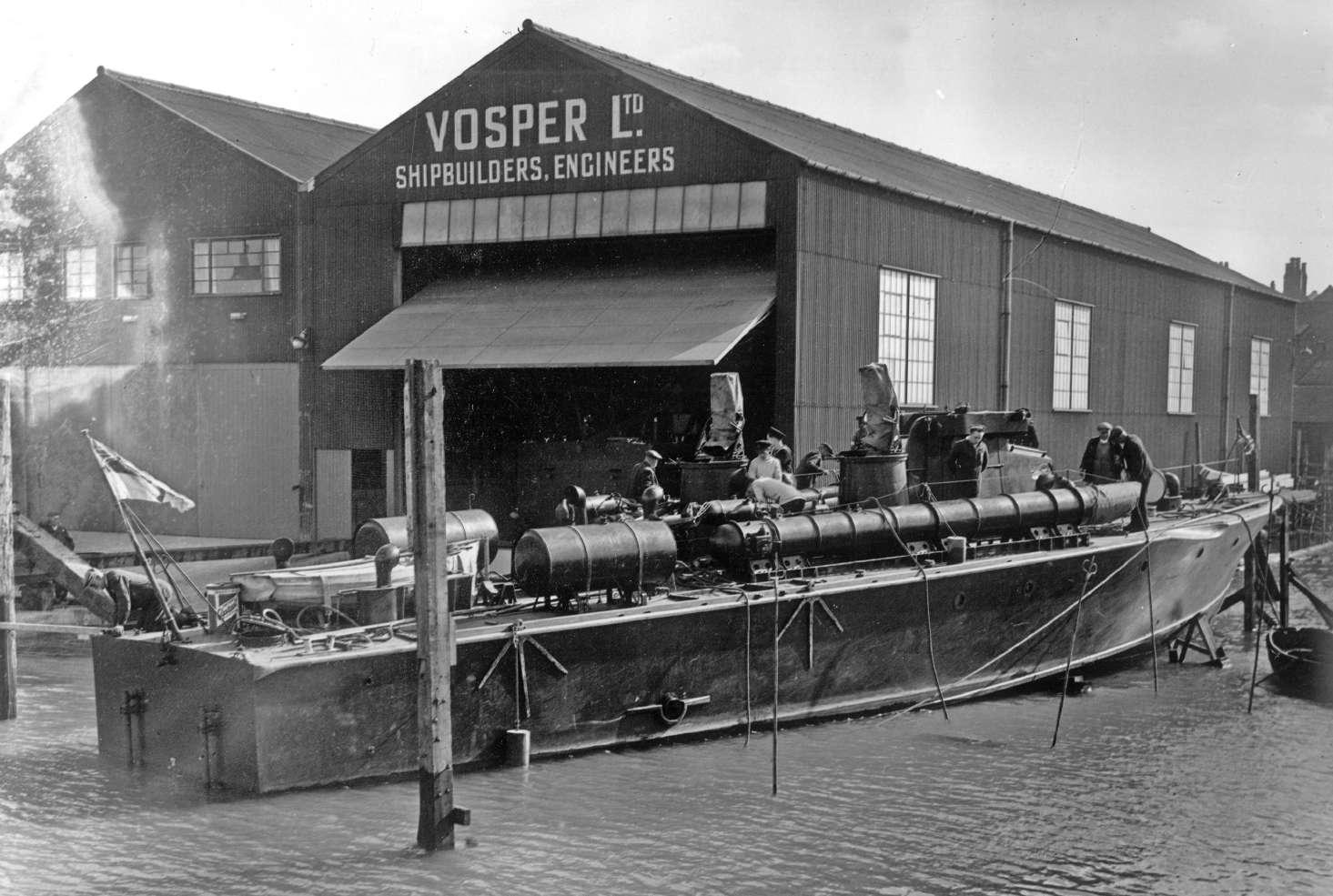

The Vosper yard in 1939 shows some of the firm’s first MTBs, probably the three soon sold to Romania These and other early Vosper boats could be distinguished by their inver ted-vee masts Note also the paired, rather than single, barbettes They were probably intended to carry Vickers GO guns

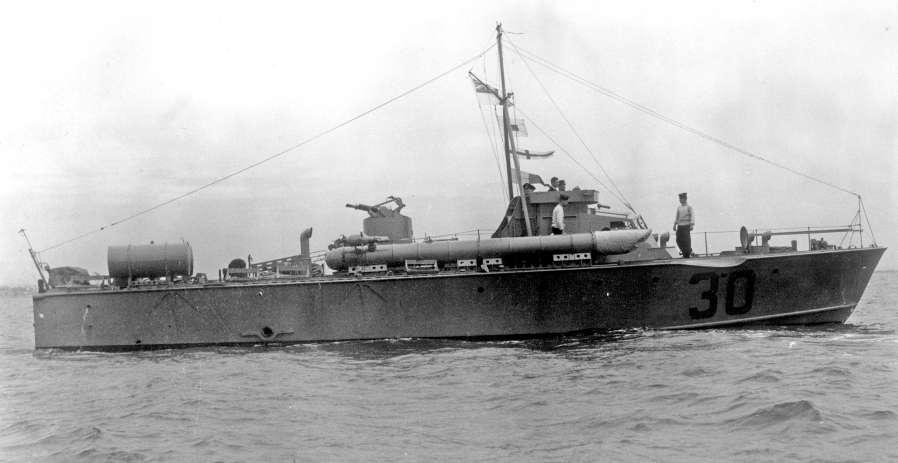

Vosper’s MTB 30 shows her auxiliary fuel tank aft (one was on each side) and her twin Mk V machine gun mounting Right aft, canvascovered, is an early version of the CSA smoke apparatus

during World War II, either by purchase or under Lend-Lease. Ultimately they were rated at a maximum power of 1350 BHP. The Packard was derived from a 2500 cubic inch aircraft engine of the early 1920s. By way of comparison, the British Merlin displaced 1650 cubic inches Displacement was a rough indicator of relative size. Both engines were V-12s. The Packard became standard onboard US and British MTBs

Thornycroft, which had been exporting MTBs (essentially upgraded versions of the World War I CMB), was also interested in the emerging sea-going MTB market. In May 1938 it decided to build a hard-chine stepless boat, 70ft long on the waterline (70ft 9in overall, meaning a nearly vertical stem). This boat was sold to Estonia in Januar y 1939 and then to Eire, which soon ordered two more, and ended up with five. On trial the prototype made 36 05kts, powered by four Thornycroft RY-12 engines geared to two shafts. The Royal Navy ordered two of these boats as MTB 24 and 25 on 15 December 1938 (B 3). They were completed in

MTB 30 in the late summer of 1940 Note the single stripped Lewis gun forward (another is on the other side), and the absence of either an auxiliary fuel tank or depth charges.

Januar y 1940 Unlike the Irish boats, they were powered by the

supplemented by the same two Ford V-8s for slow-speed silent approaches. On trials on 6 November 1939, MTB 24 made 40 03kts on full power and 42 77kts on emergency power Armament was two 21in torpedo tubes and two Vickers ‘K’ machine guns Slightly later, a repeat Thornycroft boat was ordered (MTB 28). Two more Vospers (MTB 29 and 30) were ordered at about the same time from Camper & Nicholson, the yacht builders. Three of the four initial Vospers (MTB 20, 21, and 23) were sold to Romania and replaced by three additional boats in the 1939 Supplemental program.

Two Thornycroft boats, ordered by China and interned at Hong Kong in 1938, were taken over in 1939 as MTB 26 and 27 (six others were delivered to China) They were essentially a modern version of the 55ft World War I CMB, powered by two of the firm’s RY-12 engines.

The Wartime MTB Program

The 1939 program was ten Vospers (MTB 31–40, four of which were destroyed and had to be replaced in the 1940 program).

After war broke out, the Royal Navy became interested in forming an MTB striking force, consisting of twelve sea-going boats (ie, Vospers) led by a destroyer; Ambuscade was chosen. She would be given a heavier close-range anti-aircraft batter y, to protect her flotilla under air attack. If possible her single-purpose main batter y would be replaced by high/low-angle guns, again to protect against air attack and probably also to lay down supporting fire during a torpedo attack As of October 1939, the striking force was to have been formed about March–April 1940, but that never happened It would probably have been based at Har wich British coastal forces later worked with surface leaders to deal with German coastal forces and coastal convoys

Another ten boats were ordered under a Supplemental program soon after war broke out Four boats building for Greece were to have been taken over. Ultimately the part of this program ordered directly by the Admiralty amounted to eight boats from White (MTB 41–48) and eight from Thornycroft (MTB 49–56) White produced its own design, presumably the one it offered on the export market, but the Admiralty ordered it to use Vosper’s hull lines and general arrangement. Like the Vospers, the White Boats were powered by Isotta-Fraschini engines When the supply of these engines dried up as Italy entered the war, the British were forced to resort to Hall-Scott Sea Defenders (850 BHP each) As a consequence, MTB 35–40 and White’s MTB 44–48 were rated at

MTB 34 was an early Vosper MTB. Note the row of depth charge chutes aft

28 or 29kts (they were assigned to training). British Power Boat had used a 1000 BHP marinized version of the Merlin aircraft engine in its 1938 Private Venture boat, but in 1940 such engines were urgently wanted to power the fighters defending Britain.

Some of them were installed on board MGBs, however, testament to how badly they were needed Thornycroft offered a heavier, sturdier MTB which it described as a dual-purpose Anti-Submarine Torpedo Boat, with a primar y

Above: MTB 35 was an early Vosper boat, shown as completed Unlike the earliest Vospers, she had a single barbette for a Vickers Mk V 0 5in gun mounting

Below: MTB 35 on builder’s trials in the spring of 1941, flying the Red Ensign. Note the row of five depth charge chutes abaft her torpedo tube, and the twin 0 5in Mk V mounting on the barbette

ASW role Their design was completed in June 1940 MTB 49–56 were powered by four of the firm’s RY-12 engines geared to twin shafts For greater range, a shaft could be driven by one engine Each shaft could also be driven by an auxiliar y Ford V8 engine, as in the Vospers Unfortunately, the sophisticated gearbox involved was made only in Switzerland. With France defeated and Italy hostile, there was no land connection to that countr y The prototype gearbox was removed to Britain by air, in pieces, and it took about a year to produce others The boats were not completed until April to December 1941. The Thornycroft boats were heavy, and their speeds were about the same as those of Vospers with the Defender engines. MTB 50 made only 30.45kts on trials. Nor were they as sturdy as intended; they had to be withdrawn in December 1942 with cracked frames By Februar y 1943 they had been transferred to the Army as target towers.

The 1940 program included 22 more boats, of which 10 were ordered early (26 Februar y 1940) as Vosper’s MTB 57–66 (B 4). Compared to earlier boats, they were somewhat lengthened (72ft 7in overall). They were powered by two US Packard engines. Trial speed was 37 6kts Later Vospers had three Packards

Boats building for foreign navies were requisitioned in April and May 1940 from Thornycroft (MTB 67–68 from Finland were 55ft CMB designs with torpedoes in stern troughs) and Vosper (MTB 69 and 70 from Sweden and MTB 71 and 72 from Nor way; see B 5). MTB 69–70 were later listed as ex-Greek. Like the early Vospers, these boats had Isotta-Fraschini engines The Vospers were all 60- rather than 70-footers. In addition, Nor way was given two 60-footers which operated under British operational control.

Sweden was allowed to accept two British Power Boat 63-footers. All of these boats had protective plating over the wheelhouse, but not over the bridge above it, the boat being conned from the bridge but steered from the wheelhouse

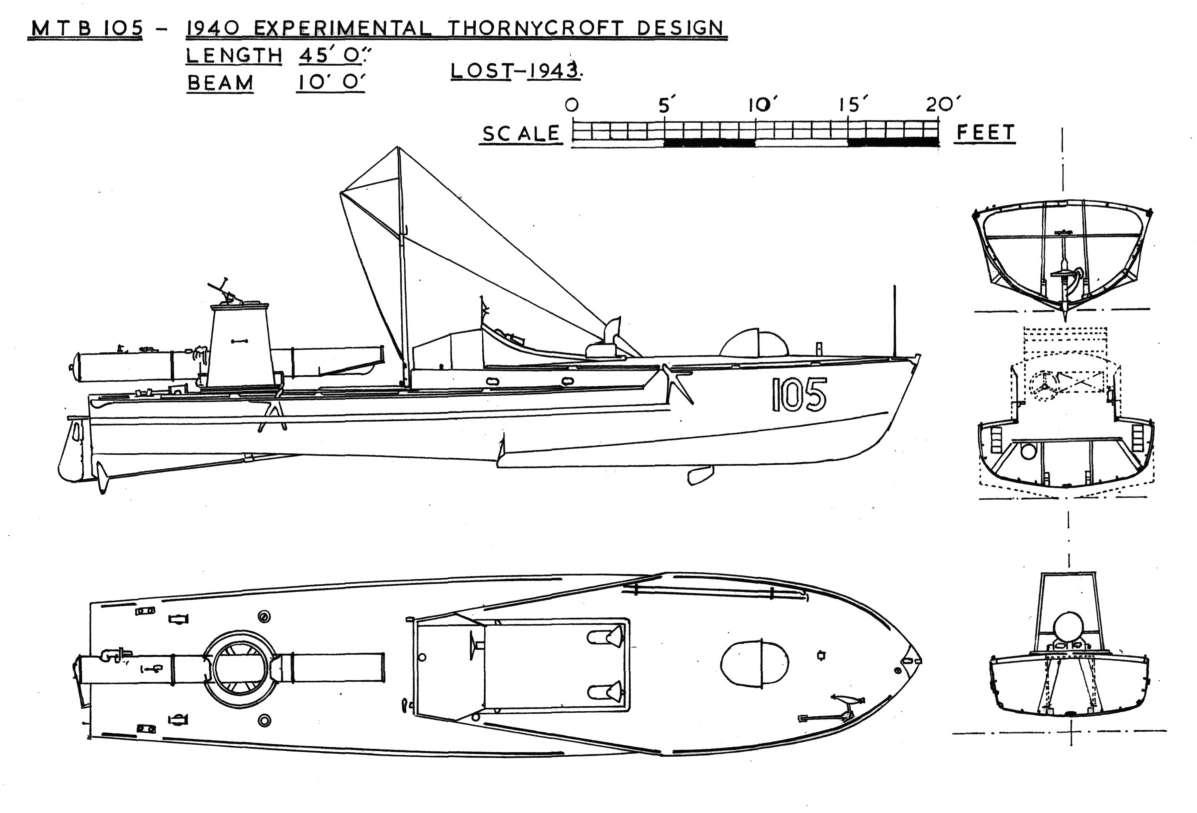

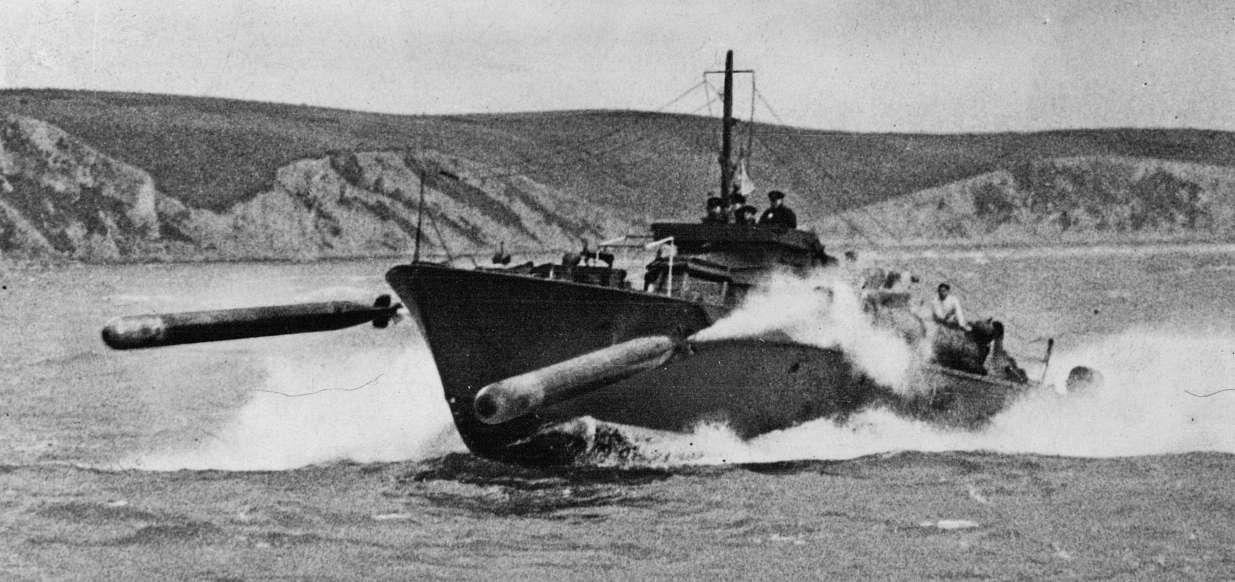

As in World War I, there was interest in an MTB carrier which could bring attack boats close to harbours to attack ships inside A cruiser could carr y a small MTB and hoist it over the side using her seaplane crane Early in 1939 a formal requirement for such a boat was stated, and tenders were invited Speed fully loaded was to be 50kts, and displacement fully loaded not more than 8 tons. Length would be 40ft to 45ft, and endurance would be 100nm at twothirds speed. The engine would be a marinized Merlin, and armament would be limited to two 18in torpedoes in loose-fit tubes on the sides. Several firms offered designs, but Thornycroft was already building a boat which was about what the Admiralty wanted. It carried its torpedo in a single swivelling tube. It was bought as MTB 105 (see below) She had an unusually small turning circle, but the lightly-built hull was poorly adapted to the stress of the movable torpedo tube, and the hull structure was disliked. The idea of a carrier and a small MTB to match stayed alive, and it figured in the projected 1943/44 program

For the 1940/41 program DNC decided to standardise on the Vosper hull for quicker production The Blitz badly damaged Portsmouth and the Vosper yard there, so the Admiralty ordered the company to sub-contract construction. It resisted on the

Ordered for Greece, T 3 ran trials with her Greek designation before being taken over in the spring of 1940 to become MTB 69.

ground that the subcontractors would be its future competitors, but it could not meet the demand with its damaged facilities At one point Harland & Wolff would have built fourteen boats in Belfast, but instead Vosper dealt with yacht-builders

O rd e re d o n 2 0 Ma y 1 9 4 0 , M T B 7 3 – 9 8 w e re s l i g h t l y lengthened (71ft) repeat versions of the 1939 boats, the prototypes of all later British-built MTBs except for the dual-purpose Fairmile Ds Of this batch, MTB 74 was modified for a special operation (ultimately the St Nazaire raid of March 1942) with 18in torpedo tubes right for ward to fire heavy mines over net defences. Her 0.5in

Above: Early Vosper boats alongside MTB 73 shows her twin power gun mounting abaft her bridge.

Right: Twin 0.5in gun on board MTB 94, 18 January 1943.

machine gun turret was removed and the sides of her bridge cut away to reduce weight MTB 75 was bombed while under construction and had to be replaced. Twelve boats of the same type were ordered from J S White: MTB 201–212. This odd numbering was adopted because the MTB 100 series was reser ved for one-off or experimental types, as described below (the number MTB 99 apparently was not used) The Admiralty tried to use sequential numbers for flotillas, so it resumed with MTB 201. These boats could be steered from either the open bridge or the wheelhouse below it. In the 1940/41 boats protection was limited to the bridge, as by that time it was clear that boats would normally be steered mainly from there.

MTB 74 was specially modified for a special operation raid, her torpedo tubes raised so that they could fire over anti-torpedo nets

The weapons were essentially stand-off mines, intended to hit the side of an enemy ship in harbour, then sink and explode using a timer Initially she was to have attacked a German battleship at Brest, but after the Channel Dash removed those ships, she was assigned to the St Nazaire raid, in which she was lost

The White-built MTB 206 differed in detail from Vosper boats: note the single side exhaust Her mast carries the antennas of a Type 286 radar

In the 1940/41 Vospers the Packard engine was geared down, and fuel capacity was considerably increased. Initially there were propeller problems, due in part to added displacement Once they had been resolved, typical maximum speed fully loaded was 38.9kts (35 2kts continuously) Due to a shortage of Packard engines, the White boats used heavier 1100 BHP Sterling Admiral engines (later White boats had modified hull forms adapted to this extra weight aft). With reduced fuel to balance the added weight of the engines, and the modified hull form, the White boats had a

scantlings, which caused problems in some later units.

Typically boats with Packards had auxiliar y power in the form of a pair of Ford V-8s, which were intended to propel the boat quietly. By late 1942 the Packards were being silenced effectively, so it was possible to eliminate the quiet cruising engines One V-8 was retained as an auxiliar y and batter y-charging engine. As of Januar y 1943 the first modified boat had been running satisfactorily for several months.

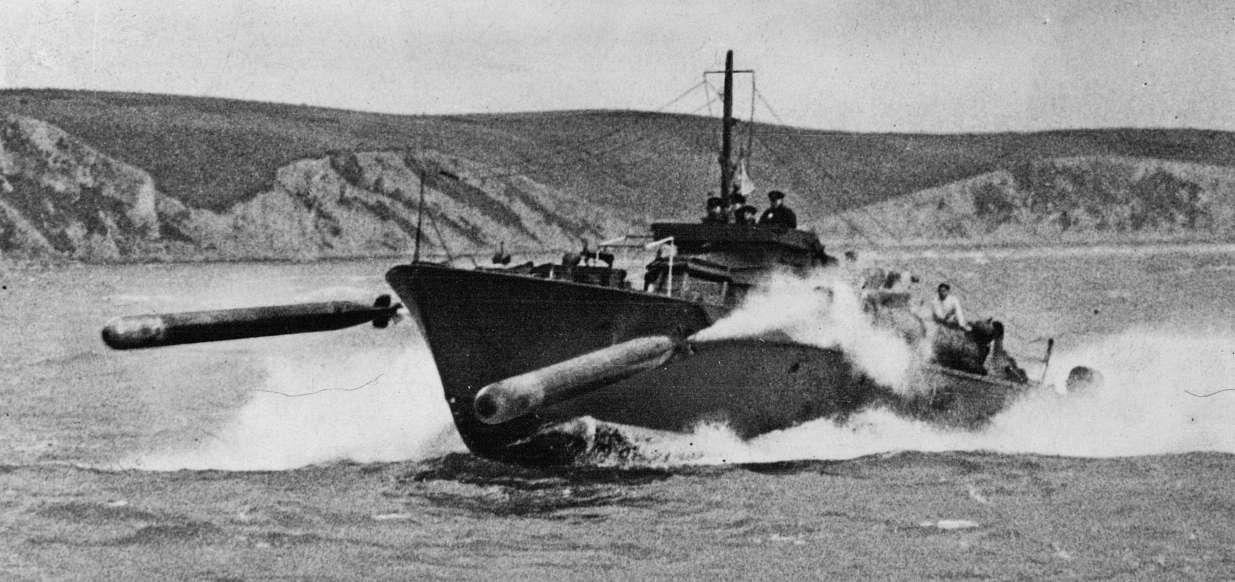

Later in 1940 five Thornycroft boats (MTB 213–217) and four Vosper boats (MTB 218–221) ordered for foreign navies were requisitioned The Thornycrofts were 55ft stepped-hull boats, essentially modernised CMBs, powered by twin RY-12s. The first of them were ordered in October 1939 by the Philippine Commonwealth government as part of a defensive program; they were requisitioned by the Royal Navy in June 1940 before they could be delivered. On trials in September 1940, MTB 213 made 46 76kts

Vosper’s MTB 218–221 were standard 70-footers intended to replace earlier boats taken over from Greece (MTB 71 and 72 plus

The Coastal Forces base at Felixstowe, HMS Beehive. Most boats are Vosper MTBs (MTB 72, 34, 32, 69, and 70 of the 4th MTB Flotilla). In the foreground are two British Power Boat 71ft 6in MGBs, identifiable by their superstructures and their prominent breakwaters

two given to Nor way). They were powered by Hall-Scott engines and therefore slow These boats had been ordered for Greece to replace four taken over earlier; these in turn were taken over by the British after Greece fell to the Germans.

There were also experimental or one-off types in the MTB 100 series MTB 100 was the converted British Power Boat fast minesweeper. MTB 101 was a hydrofoil built by White. After extensive trials of an 18ft hydrofoil boat, the firm estimated that a full-size hydrofoil could make 70–80kts, and it proposed a 67ft boat based on CMB designs It was powered by three IsottaFraschini engines, and used ladders of foils. On final trials in May 1940 it made 41 35kts on a displacement of 22 8 tons; at 28 tons it made 34.23kts. Speed was limited by the severe cavitation which set in over the surface of the foils. Once the boat rose up on its foils

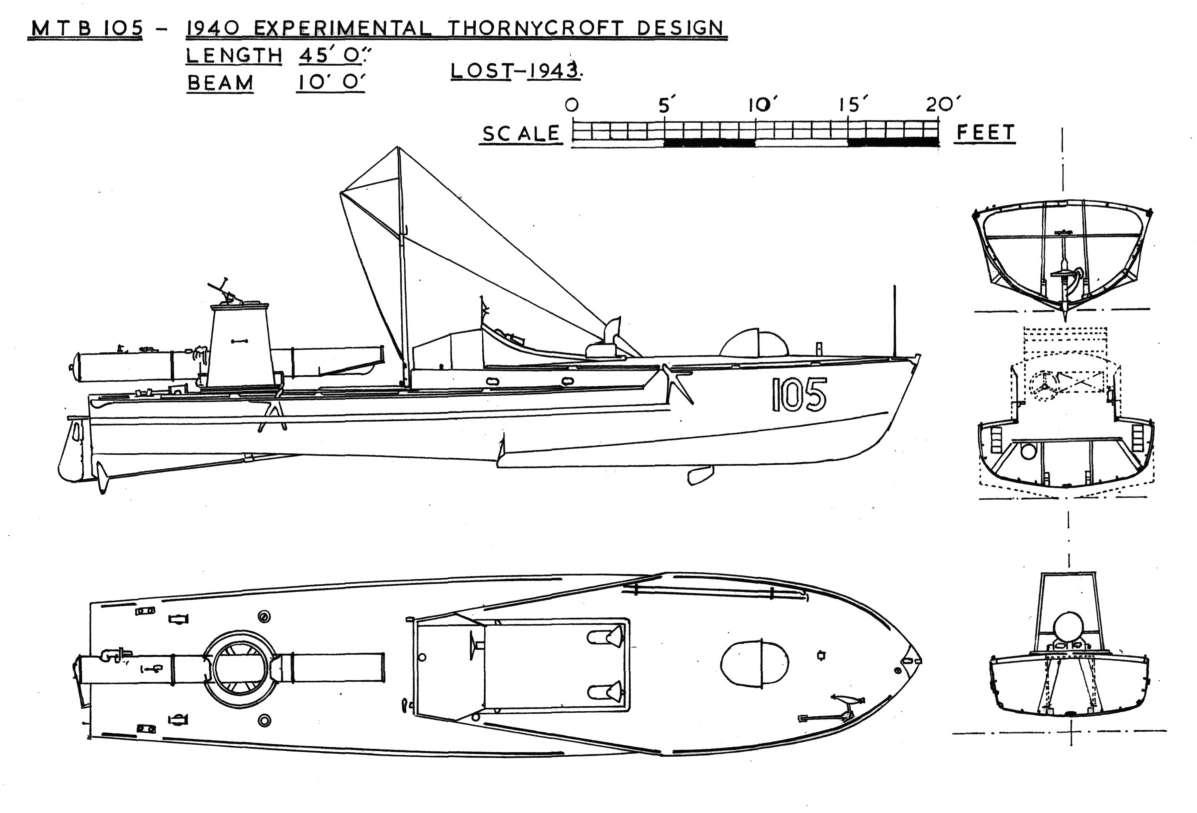

it could not gain further speed. The project died. MTB 102 was the Vosper prototype MTB 103 was a Vosper stepped-hull design which the company thought would make 5kts more than the hardchine type without suffering from hard riding Originally Vosper hoped to power it with Merlins. When they could not be obtained, it proposed using two 1500 BHP supercharged Isotta-Fraschinis; when they could not be obtained, Vosper had to settle for two unsupercharged 1100 HP Packards. That killed any hope of achieving unusual speed; the boat ended up as a radio-controlled target MTB 104 and 105 were requisitioned Thornycroft boats, of which MTB 104 was a 45ft stepped-hull boat powered by a single RY-12 engine, ordered as a private venture in May 1939 and taken over in Januar y 1940; she had two torpedoes in stern troughs, and on trial in April 1940 made 38.87kts. MTB 105 was a 45ft stepped-hull boat powered by a single Merlin, ordered as a private venture in April 1939 and taken over in Januar y 1940. She was armed with a single swivelling 18in torpedo tube, and on trials it made 50 39kts MTB 106 and 107 were ordered from Thornycroft as remote-controlled (distance-controlled) boats and then completed as MTBs They were 40ft stepped-hull boats (like a CMB) powered by a single RY12 and armed with one 18in torpedo in a stern trough. MTB 108

The Thornycroft experimental 45ft design that became MTB 105, drawn by John Lamber t

was a private-venture design produced by Aero-Marine, which had a licence for the French lightweight 600 BHP Lorraine ‘Petrel’ engine. The boat was designed by Chantiers Navals de Meulan, which built French MTBs; it was intended to compete with British and French designs in 1936/37. This ’40-K’ boat was bought by the Spanish Republic during the Civil War, and it ordered eleven more They could not be delivered. Aero-Marine tried and failed to sell similar boats to China and to the Royal Navy In 1939 the prototype, lying in the Vosper yard, was taken over by the Royal Navy (this designation also applied to a French-built MTB, and to a second Vosper boat bombed while building in 1941). MTB 109 was Denny’s semi-hydrofoil, a conventional hull with a foil at the after end. At high speed the boat was to ride on the foil and on the for ward step of the hull Denny proposed something comparable to MTB 105, but with two conventional torpedo tubes; it hoped for 55–60kts in smooth water On trials in September 1944 it made 45.9kts. Unfortunately, the boat lacked lateral stability and was considered unsafe, hence unusable.

MTB 219 test-fires her two 21in torpedoes at speed She was one of the batch powered by Hall-Scott engines, hence unable to reach the desired speed Note the characteristic scallops cut into the deck-edge. They made it possible to mount torpedo tubes low on deck, since the torpedoes could still clear the deck-edge

Explaining the 1941 program, First Lord wrote in April of that year that with the completion of earlier programs the Royal Navy had its planned 12 flotillas (96 boats, 8 per flotilla) He wanted another 32 boats in 1941 as replacements for existing ones, based on a three-year life Any increase in strength would have to come from the United States. The initial Lend-Lease request included a total of 265 motor boats of various types, 32 Vosper and 20 Elco MTBs among them. The United States agreed to supply 28 small combatants, but as of autumn 1941 it appeared that only 22 could be provided

In fact, 36 MTBs were built in Britain: Vosper’s MTB 222–245 (replacing 1939 program boats recently destroyed) and White’s MTB 246–257. These boats were similar to earlier Vosper craft except that their Packard engines were not geared Vosper executed a licence agreement with Annapolis Boats in April 1941. It built 22 boats: (MTB 275–306) rather than the 32 envisaged Elco built another 30: MTB 259–268 and 307–326, of which the US Navy retained 10 (MTB 317–326) Canada provided 12 boats: MTB 332–343 (all ordered in July 1940 as CMTB 01– 12, but with high RN numbers because they were taken over much later) The Canadian and Elco boats were all versions of the British Power Boat PV design, which the Royal Navy had rejected Numbers were made up by MTB 258, the original PV bought by the US Navy as PT 9; the Higgins MTB 269 and 270; non-standard PTs built for

Early Vosper MTBs at Felixstowe coastal forces base in March 1943. Note the single Oerlikon added to the boat on the extreme left Its added weight forward would make it more difficult for the boat to plane, raising its bow out of the water Note also how wheelhouse windows have been covered over in the boats in the second trot (and in the boat on the right) It was soon clear that boats would generally be conned from the open bridge above the pilot house

the US Navy as 7–8 and PT 3–4, respectively, which became MTB 271–274; and five more 55ft stepped-hull Thornycroft boats ordered by the Philippines in June 1940 as MTB 327–331. They had been ordered to replace the boats taken over earlier.

A standard war time Vosper MTB shows large auxiliary fuel tanks aft.

Although the prototype Elco PT boat (which became MTB 258) was a 70-footer like the PV, the production version (after the first 22) was lengthened to 77ft. Later Elco lengthened its boat further to 80ft, the first boat of the new type being laid down in Januar y 1942. Although US boats were armed with four torpedo tubes, the Royal Navy landed two of them, retaining the two for ward tubes. Higgins boats were 78-footers. Compared to the Elcos, they were somewhat slower but accelerated faster, turned more tightly, and were slightly more economical in fuel

T h re e T h o r n yc ro f t b o a t s b o u g h t i n 1 9 4 1 b e c a m e M T B 344–346 MTB 344 was a prototype stepped-hull 60-footer with CMB-type stern torpedo troughs; she made 40.82kts on May 1942 preliminar y trials (but only 36 79kts on official trials, presumably at deeper draught). Thornycroft apparently hoped to sell eight more, but the Admiralty was not interested An MGB conversion was considered but not carried out. MTB 345 was a prototype 55ft stepped-hull minelayer/torpedo boat (two RY-12 engines, 41 08kts on trials at 16.05 tons). MTB 346 was an experimental internaltube boat built as a private venture, with a CMB-style 45ft stepped hull. Powered by a single RY-12, she made 31.07kts on trials in August 1941

The initial 1942 program called for no conventional MTBs at all, only 16 small ones (50ft long) to be carried to an enemy port

Drawn up on a slip, Vosper’s MTB 347 shows her exhausts and the barbette of her twin Mk V gun mounting for 0 5in machine guns

Note also that her rudders are hung from her transom (the ver tical rudder posts are visible), leaving them vulnerable to underwater damage

by two carrier ships. This project died, all the British-built MTBs being Vospers: MTB 347–362 (B 6) MTB 363–378 were built in the United States under Lend-Lease; MTB 363–370 went to the Soviet Navy. On 9 November 1942 Vosper received a contract for a modified design powered by three up-rated Packards (total 4200 BHP), with a maximum speed of 39kts. MTB 379 (completed Januar y 1944) was the prototype

When the 1943 program was framed, British production capacity was badly strained, and there was a considerable effort to limit new construction of small craft. The total requirement for 70ft MTBs was 140 boats, 103 of which would be in ser vice in Februar y 1943. Another 18 were building or authorised for construction in Britain, plus 48 in the United States The proposed new construction program was another 16 Vospers plus the prototype MTB 379: MTB 379–395 Further craft built under this program were 16 Lend-Lease Vospers (MTB 396–411) and 6 White-built boats of Vosper design (MTB 424–429)

The British-built Vospers of this program had redesigned bridges: the long low wheelhouse was eliminated in favour of a

much shorter structure with a steeply inclined face That left more space on the foredeck for armament. Typically, the gun for ward was placed on a bandstand clear of the deck (B 7) The 1943 small MGBs were similarly modified. Vosper MTBs built in the United States were not modified The 1943 MTBs had alternative armaments emphasising either gun or torpedo In one, the two 21in torpedo tubes of earlier Vospers were replaced by four 18in tubes, a twin Oerlikon being mounted on the centreline for ward Alternatively, the new automatic 6pdr could be mounted abaft the bridge A twin hand-worked Oerlikon was mounted on the forecastle, and there were two 18in tubes. There were also two sided twin 0 303in Vickers GO guns abreast the bridge One Holman projector right aft could fire flares. Early in 1944 approval to arm MTB 379–395 with 6pdrs was withdrawn, presumably due to delays in producing this gun.

The Vospers were supplemented by British Power Boat exMGBs (see below): MTB 417–418 and MTB 430–489. MTB 419–423 were Higgins PT boats supplied under Lend-Lease

The 1944 program boats were Vosper’s MTB 523–538 (another 16 boats) and British Power Boat MGBs ordered as convertible craft: MTB 490–509 and MTB 519–522 (24 boats; see B 8). In addition, the program included the experimental MTB 539. The

Vosper’s MTB 355 running trials shows her two single Oerlikon mounts (although the barrels are not yet fitted)