ORIENTALIA LOVANIENSIA ANALECTA

John Plousiadenos (1423?-1500)

A Time-Space Geography of his Life and Career

by ELEFTHERIOS DESPOTAKIS

JOHN PLOUSIADENOS (1423?-1500)

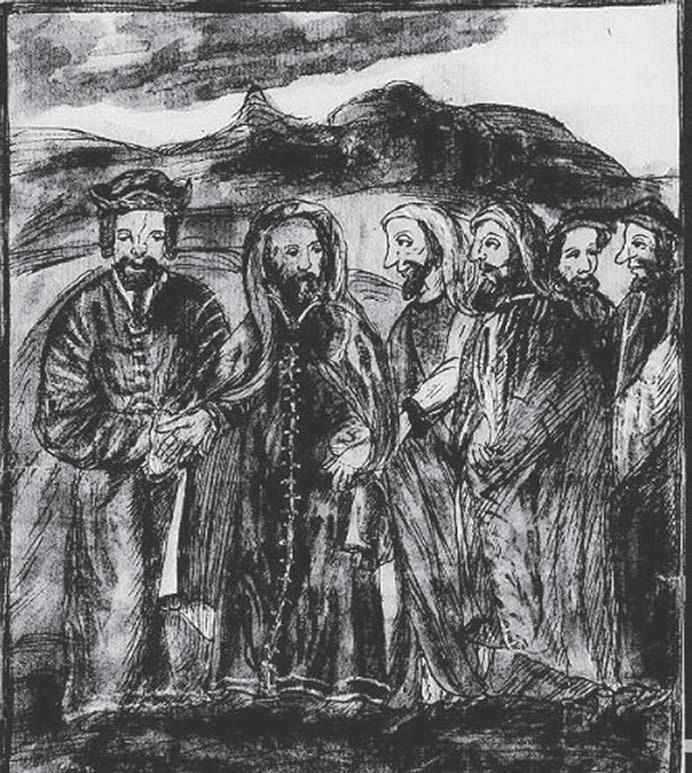

Questi sono gli huomini et religiosi di Candia, ritratti dal suo naturale (Houghton Library, MS Riant 6, 15th c.)

ORIENTALIA

BIBLIOTHÈQUE DE BYZANTION

21

JOHN PLOUSIADENOS (1423?-1500)

A Time-Space Geography of his Life and Career

DESPOTAKIS

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

© 2020, Peeters Publishers, Bondgenotenlaan 153, B-3000 Leuven/Louvain (Belgium)

All rights reserved, including the rights to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form.

ISBN 978-90-429-3787-1

eISBN 978-90-429-3788-8 D/2020/0602/13

To Polyvios & Zoi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PREFACE

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

1. INTRODUCTION

I. The ecclesiastical state in Crete after the Fourth Crusade . . . 1

II. Crete and the Union of the Churches: Uniate trends and anti-Uniate resistance in the first half of the 15th century

2. THE FIRST STEPS OF CAREER PLANNING

I. The Cretan background of his education

II. The establishment of Bessarion’s Bequest

III. The codex Ambrosianus H 41 sup. (Martini-Bassi 429) .

3. PERCEPTIONS AND REALITIES IN THE RELIGIOUS LIFE OF CHANDAX.

I. The encyclical monitory letter to the Orthodox priests of Chandax

II. The letter of Bessarion in 1465 and the Uniates’ everyday life .

III. Fifteen years of contest for the office of vice-protopapas .

4. INTELLECTUAL AND ECCLESIASTICAL

I. Crete, Rome and the “codices Marciani”

II. The project of the Castle Montauto and the Greek community of Venice

III. The hegoumenìa at St Demetrios’ de Perati monastery and the ascension to the bishopric throne of Methone . .

APPENDIX

I. The Prayer to the Holy Spirit

II. The Pattern for the Catholic confession

III. Manuscripts

IV. Archival documents

V. Tables

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I. Index of manuscripts cited

II. Index of names

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am indebted to numerous teachers, colleagues and friends who have generously given off themselves to advice, support and encourage me during this project. First and foremost, I owe my deepest debt of gratitude to Antonio Rigo who has patiently and kindly directed the development of this work during my postdoctoral fellowship at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. I am also profoundly grateful to Thierry Ganchou, who has so generously given of his time and shared his erudition at every stage of my research and at this book in particular. This work is also a product of my research fellowship at the Hellenic Institute of Byzantine and Post-byzantine Studies in Venice where I benefited of the supervision of Chryssa Maltezou who first inspired my interest in the archival research and supported me with consistent care and quality. For all of her contributions, I express my warmest gratitude. My sincere gratitude also goes to my academic supervisor at Athens, Anastasia Papadia-Lala, for guiding me through my Ph.D. dissertation on the Uniates of Crete (15th c.) and offering me several very helpful suggestions. Last but not least, I would like to thank Peter Van Deun for his careful reading of the manuscript and for his valuable comments and corrections. Finally, I want to thank all those who have facilitated my work and supported the conclusion of this book: Panagiotis Athanasopoulos, Olivier Delouis, Marina Detoraki, Paolo Eleuteri, Christian Förstel, Ciro Giacomelli, Ottavia Mazzon, Brigitte Mondrain, Symeon Paschalidis and Arnold Van Gemert.

PREFACE

Sixty years ago, in 1959, Manoussos Manoussakas published an article that began with the following words: “La personnalité et les écrits de Jean Plousiadénos ou, en religion Joseph, évêque de Méthone († 1500), copiste et écrivain crétois et l’un des théologiens et controversistes Grecs les plus remarquables parmi les partisans de l’Union de Florence, ont souvent suscité l’intérêt des savants [...] Sa vie offre pourtant encore plusieurs points obscurs. Cet article, loin de constituer une biographie complète de Plousiadénos, se propose modestement de jeter un peu de lumière sur certains de ces points”.

Despite the quoted words above, the study of Manoussakas, which was mainly based on Venetian archival sources, has remained until today an essential point of reference for the research devoted to John Plousiadenos, to other personalities who were related to him and, more generally, to the intellectual and religious history of the Greek Unionist circles of the second half of the fifteenth century.

At the same time, a new period was inaugurated with studies dedicated to Bessarion, his school, his writings and his library. Increased research interest also focused on Cardinal’s collaborators, their activities, intellectual works and book production.

The book by Eleftherios Despotakis, a researcher already known for his important contributions on Byzantium and Italy between the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries, has thus a twofold background. On the one hand, the traditional research in the State Archives and the Historical Archive of the Patriarchate of Venice, and on the other hand the investigation of writings and codices of Bessarion and his collaborators, including John Plousiadenos, as well as of palaeographic and philological studies on the ‘Quattrocento’ between Byzantium and the West.

Despotakis’ research, therefore, moves on three distinct levels, skilfully maintained together by the scholar: the archival documents, the manuscript production and lastly the literature of the period. This synthesis allows Despotakis to reconstruct a complete biography of John Plousiadenos, between Italy and Crete, until his death in Methone, and to present his career in an exhaustive way, including his ecclesiastical mission in favour of the union of the Churches in the footsteps of Bessarion, his activity as a copyist and also his literary work, which was the result of the meeting of Byzantine and Latin cultures.

In this way, sixty years after the study of Manoussakas that has so far influenced our knowledge and research on Plousiadenos and his environment, we have a new and more complete guide, which we will certainly use for a long time.

Venice, May 2019

Antonio Rigo

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AASS Acta Sanctorum

AB Analecta Bollandiana

ACO Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum

AHR The American Historical Review

ArchAth Archives de l’Athos

ASE Annali di storia dell’esegesi

BA Byzantinisches Archiv

BBA Berliner Byzantinistische Arbeiten

BBGG Bollettino della Badia greca di Grottaferrata

BECK, Kirche und theologische Literatur

H.-G. BECK, Kirche und theologische Literatur im byzantinischen Reich (Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft, XII.2.1), München, 1959 (= 1977)

BETL Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium

BF Byzantinische Forschungen

BHG Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca

BHL Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina

BHO Bibliotheca Hagiographica Orientalis

BMGS Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies

BNJ Byzantinisch-Neugriechische Jahrbücher

BSGRT Bibliotheca Scriptorum Graecorum et Romanorum Teubneriana

Bsl Byzantinoslavica

Byz Byzantion

BZ Byzantinische Zeitschrift

CACahiers Archéologiques

CABCorpus des astronomes byzantins

CCCA M. GEERARD, J.C. HAELEWYCK, Corpus Christianorum, Claves Apocryphorum Veteris et Novi Testamenti, Turnhout, 1992, 1998

CCSG Corpus Christianorum, Series Graeca

CCSL Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina

CFHB Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae

CIG Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum

CIL Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

CJ Codex Justinianus

CPG

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

M. GEERARD, Clavis Patrum Graecorum, 5 vol., Turnhout, 1983, 1974, 1979, 1980 and 1987; M. GEERARD – J. NORET, Clavis Patrum Graecorum. Supplementum, Turnhout, 1998; J. NORET, Clavis Patrum Graecorum, III A, editio secunda, anastatica, addendis locupletata, Turnhout, 2003

CSCO Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium

CSEL Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum

CSHB Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae

CTh Codex Theodosianus

DACL Dictionnaire d’Archéologie Chrétienne et de Liturgie

DB Dictionnaire de la Bible

DHGE Dictionnaire d’Histoire et de Géographie Ecclésiastiques

DOP

DOS

DSp

DXAE

Dumbarton Oaks Papers

Dumbarton Oaks Studies

Dictionnaire de spiritualité

Deltíon Xristianik±v ˆArxaiologik±v ¨Etaireíav

EEBS ˆEpetjrìv ¨Etaireíav Buhantin¬n Spoud¬n

EHRHARD, Überlieferung

A. EHRHARD, Überlieferung und Bestand der hagiographischen und homiletischen Literatur der griechischen Kirche von den Anfängen bis zum Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts (TU 50-52), 3 vols, Leipzig, 1937-1952

EO Échos d’Orient

FHG C. MÜLLER, Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum, 5 vols., Paris, 1841-1883

GCS Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller der ersten Jahrhunderte

GNO Gregorii Nysseni Opera

GOThR The Greek Orthodox Theological Review

GRBS Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies

HUNGER, Hochsprachliche profane Literatur

JANIN, Géographie ecclésiastique

JG

H. HUNGER , Die hochsprachliche profane Literatur der Byzantiner (Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft, XII.5), 2 vols., München, 1978-1979

R. JANIN, La géographie ecclésiastique de l’Empire byzantin, pt. 1, Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat œcuménique, t. III, Les églises et les monastères, Paris, 19692

I. ZEPOS – P. ZEPOS, Jus Graecoromanum, 8 vols., Athens, 1931

JHS Journal of Hellenic Studies

JÖB Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik

JÖs Jahrbuch der Österreichischen byzantinischen Gesellschaft

JRA Journal of Roman Archaeology

JRS Journal of Roman Studies

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

JThS The Journal of Theological Studies

KAZHDAN, History of Byzantine Literature (650-850)

KAZHDAN, History of Byzantine Literature (850-1000)

KRUMBACHER, Geschichte der byzantinischen Litteratur

A. KAZHDAN, A History of Byzantine Literature (650-850), in collaboration with L. F. SHERRY and Ch. ANGELIDI (Institute for Byzantine research. Research series, 2), Athens, 1999

A. KAZHDAN, A History of Byzantine Literature (850-1000), edited by Ch . ANGELIDI ( Institute for Byzantine research. Research series, 4), Athens, 2006

K. KRUMBACHER, Geschichte der byzantinischen Litteratur von Justinian bis zum Ende des oströmischen Reiches (527-1453).

Zweite Auflage bearbeitet under Mitwirkung von A. EHRHARD – H. GELZER (Handbuch der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, IX.1), München, 1897

LAMPE, Lexicon G. W. H. LAMPE, A Patristic Greek Lexicon, Oxford, 1961

LBGLexikon zur byzantinischen Gräzität

LchILexikon der christlichen Ikonographie

LMLexikon des Mittelalters

LSJ H. G. LIDDELL – R. SCOTT, A Greek-English Lexicon, a new edition revised and augmented throughout by H. S. JONES, Oxford, 19409, with a Supplement ed. by E. A. BARBER, Oxford, 1968 (several reprints)

MANSI J. D. MANSI, Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, Florence – Venice, 1759-1798

MGHMonumenta Germaniae Historica

MM F. MIKLOSICH – J. MÜLLER, Acta et diplomata graeca medii aevi, 6 vols, Wien, 1860-1890

MusLe Muséon

NE Néov ¨Elljnomnßmwn

OCAOrientalia Christiana Analecta

OCPOrientalia Christiana Periodica

ODB P. KAZHDAN et alii (eds), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, 3 vols., Oxford, 1991

OLAOrientalia Lovaniensia Analecta

Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies E. JEFFREYS – J. HALDON – R. CORMACK (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies, Oxford, 2008

PGPatrologia Graeca

Pinakes

Pínakev / Pinakes: Textes et manuscrits grecs (I.R.H.T., Section grecque, Paris): http://pinakes.irht.cnrs.fr/

PLPatrologia Latina

PLPProsopographisches Lexikon der Palaiologenzeit, Wien, 19761996

PLREThe Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, 3 vols, Cambridge, 1971, 1980 and 1992

PmbZ

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit, hrsg. von der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, nach Vorarbeiten F. WINKELMANNS erstellt von R.-J. LILIE, C. LUDWIG, T. PRATSCH, I. ROCHOW, B. ZIELKE u. a., Abt. 1 (641-867), 6 + 2 vols, Berlin – New York, 1998-2002; Abt. 2 (867-1025), 8 + 1 vols, Berlin – Boston, 2009-2013

PO Patrologia Orientalis

PTS Patristische Texte und Studien

RAC

Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum

RACP Les Regestes des Actes du Patriarcat de Constantinople, pt. 1, Les Actes des Patriarches, 7 vols, ed. V. GRUMEL (vols 1-3), V. LAURENT (vol. 4) et J. DARROUZÈS (vols 5-7), Paris, 1932-1991

RBKReallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst

REReal-Encyclopädie (Pauly-Wissowa)

REARevue des études anciennes

REBRevue des études byzantines

REGRevue des études grecques

RGK E. GAMILLSCHEG – D. HARLFINGER – H. HUNGER, Repertorium der griechischen Kopisten 800-1600. 1. Handschriften aus Bibliotheken Grossbritanniens. 2. Handschriften aus Bibliotheken Frankreichs. 3. Handschriften aus Bibliotheken Roms mit dem Vatikan (Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Klasse. Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für Byzantinistik, 3), Wien, 1981, 1989 and 1997

RH Revue Historique

RHE Revue d’Histoire Ecclésiastique

RHTRevue d’histoire des textes

RMRheinisches Museum für Philologie

ROCRevue de l’Orient Chrétien

RSBNRivista di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici

SCSources Chrétiennes

SESacris Erudiri

SHSubsidia hagiographica

STStudi e Testi

Syntagma

G. RHALLES – M. POTLES, Súntagma t¬n qeíwn kaì ïer¬n kanónwn, 6 vols, Athens, 1852-1859

TB C. G. CONTICELLO – V. CONTICELLO (eds), La théologie byzantine et sa tradition, t. II, t. I/1, Turnhout, 2002, 2015

TIB Tabula Imperii Byzantini

TLG Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, TLG®, registered trademark of the University of California: http://www.tlg.uci.edu/

TM Travaux et Mémoires

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

TU Texte und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der altchristlichen Literatur

VigChr Vigiliae Christianae

VV Vizantijskij Vremennik

WBS Wiener Byzantinistische Studien

WS Wiener Studien

ZRVI Zbornik Radova Vizantološkog Instituta

I. THE ECCLESIASTICAL STATE IN CRETE AFTER THE FOURTH CRUSADE

In the period extending from the 13th to the 16th century Venice had to face the opposition of the local population of Crete to the new political status.1 However, the variety of sociocultural fermentation between rulers and the indigenous people gradually led to the formation of a conservative dependent colony, but with its own exclusive social, economic and cultural characteristics.2 The gradual evolution of the capital city of Chandax in a key-centre of the wider Mediterranean’s commercial network chronologically coincided with a preparatory period for the flourishing of Arts and Letters which found its consolidated form in the late 16th century.3 In the general context of this natural process, the basic “yardstick” of the Venetian administration was undoubtedly the political stability inside the colony.

Before the Venetian conquest, Chandax was one of the many ports of the Byzantine province. After 1211 and especially from the late 14th century onwards, the urban planning saw a great development and became the political, economic, military and cultural centre of Crete as well as of the whole Venetian Stato da Mar. Chandax was surrounded by walls built in the Byzantine period, which separated the urban centre (civitas) from the suburban area (burgus). During the 2nd half of the 15th century, the residential development of the suburban settlements and the primary need to protect the capital gave a start to the reinforcement of the old Byzantine defences together with the construction of a new fortified perimeter of walls for the protection of the burgus. For the entrance to the “older” city there were two main gates, viz. the Great Gate (Porta magna, Porta civitatis, Porta grande, Porta Platee or Porta), at the southern side of the Byzantine walls, and the See Gate (Porta ripae maris, Porta de Molo), which connected the city centre to the port in the north. The two gates were intersected by a main road, the Ruga Magistra. Along this principal road and near the Great Gate was the Square, the life core of the administrative, commercial and religious activity of

1 For the Cretan rebellions, see mainly S. BORSARI, Il dominio veneziano a Creta nel XIII secolo (Università di Napoli. Seminario di storia medioevale e moderna, 1), Napoli, 1963, pp. 27-66; S. MCKEE, The Revolt of St Tito in Fourteenth-Century Venetian Crete: A Reassessment, in Mediterranean Historical Review, 9/2 (1994), pp. 173-204; A. PAPADIA-LALA,

(1509-1528):

, Athina, 1983.

2 A. E. LAIOU, Quelques observations sur l’économie et la société de la Crete vénitienne (ca.1270-ca. 1305), in Bisanzio e l’Italia. Raccolta di studi in memoria di Agostino Pertusi, Milano, 1982, pp. 177-198.

3 See generally D. HOLTON (ed.), Literature and society in Renaissance Crete, Cambridge, 1991.

JOHN PLOUSIADENOS (1423?-1500)

Chandax. There was placed the Ducal Palace and the public services, the households of the higher government officers, the market centre, and from the 14th century the Loggia, viz. the operation centre and meeting place of the nobles.4 The most central church of the city was the ducal chapel of St Mark, at the perimeter of the Square, and the Cathedral church of St Titus, the seat of the Latin archbishop of Crete. During the 15th century the city of Chandax contained more than thirty Orthodox and six Catholic churches – including three monasteries – which were scattered over all parts of the older city.

From the beginning of their establishment in Crete, the Venetians had been aware that the political balance and security of the colony would be gained only by taking despotic ecclesiastical measures. This priority given by the Venetians to religious matters seems to be evident from the moment of the partitio terrarum Imperii Romanie5 by occupying the church of St Sophia in Constantinople and declaring to the other crusaders that: Imperium est vestrum. Nos habebimus patriarchatum. 6 The nomination of the Venetian Tommaso Morosini as Latin patriarch of Constantinople followed.7 After 1204, the Venetians’ purpose was not that to replace the Empire of Constantinople as a political hegemony but to create the best circumstances for the preservation and the expansion of their own commercial empire by controlling the religious life of their key-commercial centres. Once they established in Crete in 1211, the Venetians abolished the Orthodox episcopates and removed their head bishops. Until the end of the 15th century, future priests had to reach the Peloponnesian colonies of Maina, Methone or Corone to get ordained. In those colonies, Venice had maintained the Orthodox hierarchy with a view to avoiding those Cretan candidates coming over to the Ottoman territories which were under the influence of the Orthodox patriarchate of Constantinople.8 The Orthodox religious authorities had been

4 For the urban planning of Chandax, see in general Ch. TZOBANAKI, Χάνδακας.

τα τείχη, Heraklion, 1996, pp. 133-141; for the fortification project (1462-1669), see ibidem, pp. 237-272; for the organization and the characteristics of Chandax, see in general M. GEORGOPOULOU, Venice’s Mediterranean colonies: Architecture and urbanism, Cambridge, 2001, pp. 48-55; for the Loggia, see K. E. LAMBRINOS, Λειτουργίες της Loggia στη βενετοκρατούμενη Κρήτη, in N. M. PANAGIOTAKIS (ed.), Άνθη Χαρίτων, Venezia, 1998, pp. 227-243.

5 On this issue, see A. CARILE, Partitio Terrarum Imperii Romanie, in Studi Veneziani, 7 (1965), pp. 125-305.

6 A. J. ANDREA, Contemporary Sources for the Fourth Crusade (The medieval Mediterranean: peoples, economies and cultures, 400-1453, 29), Leiden – Boston, 2000, pp. 337-338.

7 W. O. DUBA, The Status of the Patriarch of Contantinople after the Fourth Crusade, in A. D. BEIHAMMER – M. G. PARANI – A. D. SCHABEL (eds), Diplomatics in the Eastern Mediterranean. 1000-1500: Aspects of Cross-Cultural Communication (The Medieval Mediterranean, 72), Leiden – Boston, 2008, pp. 63-91.

8 N. V. TOMADAKIS, Οἱ

, 13 (1959), pp. 39-72. From the early 16th century and above, after these colonies fell under the Ottomans, candidate were obligated to go reach the Orthodox bishoprics of Monemvasia, Corinth, Zakynthos, Chephalonia and Chythira (M. I. MANOUSSAKAS,

, 4 [1964-1965], p. 317).

replaced by Catholic prelates, almost entirely Venetians, and the city of Chandax was appointed as the seat of the Latin archbishopric. Although Venice encouraged the establishment of the Latin Church in Crete, they did not permit them to exercise authority on the Greek-orthodox priests.9 The Orthodox clergy was under the jurisdiction of the protopapas and protopsaltis (first-priest and firstchanter), Greek philocatholic deputies who were faithful to the Venetian regime.

For more than a hundred years, the Latin archbishopric of Crete, supported by the pope, was struggling against Venice in order to increase its authority upon the Greek clergy.10 By way of a papal proposal in 1266, Venice approved of the jurisdiction of the Latin archbishop upon 130 Greek priests of Chandax, St Myron and their ecclesiastical province.11 In the early 14th century major demands of the Latin Church on this issue created further tension with the political authorities.12 The new claims of the archbishop concerned his total jurisdiction on the Cretan clergy – Orthodox and Catholic – by the side-lining of the Venetian authorities. Although the archbishop’s request was excessive for the political ideology of Venice, the Doge Giovanni Soranzo was favourably disposed towards the Latin Church. On March 13, 1324, Soranzo confirmed the submission of the 130 priests to the Latin archbishop and commanded that the rest of the clergy, in case of delinquency, should be submitted firstly to the judgment of the political authorities and it should be up to them to decide to whose jurisdiction the case would belong.13 In this way, the Latin archbishop should have the same jurisdiction upon the clerics that he had upon the laics, but with the consent of the Venetian regime.

On the one hand, at the same time in which Venice delimited the involvement of the Latin Church in the affairs of the Greek clergy, Pope John XXII began to apply his project aimed at the “Latinization” of the Orthodox Cretan priests. On April 1, 1326, due to the coexistence of the two faiths in Crete, the pope encouraged the Latin archbishop to appoint a Greek philocatholic priest as his vicar and head-chief of the local clergy with a view to the gradual consent of the Orthodox population, clerics and laics, in the Church of Rome.14

Considering the limited jurisdiction that Venice had conceded to the Latin archbishop of Crete, probably the latter had tried once again – after the pope’s proposal – to extend his authority on the Cretan clergy by using the byzantine

9 BORSARI, Il dominio veneziano [see note 1], pp. 110-111; N. V. TOMADAKIS, La politica religiosa di Venezia a Creta verso i cretesi ortodossi dal XIII al XV secolo, in A. PERTUSI (ed.), Venezia e il Levante fino al secolo XV (Civiltà veneziana. Studi, 27), Firenze, 1973, vol. 1 (II), pp. 783-784.

10 Z. N. TSIRPANLIS,

(13

11 BORSARI, Il dominio veneziano [see note 1], pp. 139-143.

12 TSIRPANLIS, Νέα στοιχεία [see note 10], pp. 54-57.

13 Ibidem, pp. 94-96, doc. 4.

, 20 (1967), pp. 44-60.

14 J. GILL, Pope Urban V (1362-1370) and the Greeks of Crete, in OCP, 39 (1973), pp. 464-466.

JOHN PLOUSIADENOS (1423?-1500)

institution of protopapas.15 Hence, the archbishop would act in Crete in line with the papal instructions while at the same time he would gain full control on the Orthodox society. In order to gradually obtain his purpose through the institution of protopapas, it seems that the archbishop started to promote to this office candidates among the 130 priests who belonged to his jurisdiction. On the other hand, Venice could not permit such a diplomatic manoeuvre of the archbishop, neither wished to clearly stand up against the pope’s will. Perhaps for this reason, on October 23, 1360, Venice decided to limit the faculties of the protopapas by removing his license to examine the candidates who wished to go beyond Crete for their ordination and gave this mission to four trusted priests who were forbidden to belong to the 130 of the archbishop’s jurisdiction.16

It seems that in 1360 Venice had already established by decree that candidates should sail out of Crete in order to get ordained but we still do not know when such a decision was taken. It is quite sure that since the Treaty of Alexander Kallergis, in 1299, an Orthodox bishop – who probably could ordain priests – had been established next to Latin archbishopric of Mylopotamos.17 In 1335 an Orthodox bishop still existed in this area and, for that reason, Pope Benedict XII demanded his expulsion.18 Venice would probably decline the pope’s request in order not to break the treaty which had been signed with the rebels since, in the mid-14th century two more Orthodox bishops were presented in Crete viz. Makarios, in 1357, and Anthimos the Confessor a little later. However, in 1373 the Church of Rome declared its satisfaction with Venice for the final expulsion of the Orthodox bishops from Crete.19

Although Venice clearly opposed to the plans of the archbishop and the pope in 1360, the latter persisted in his attempts to spread the Catholic faith within the Orthodox Cretan society. The executive agent of Rome was the Latin archbishop of Crete – and patriarch of Grado as well – Francesco Querini, who promoted the election of George Rabanis to the office of protopapas in the city of Chandax in 1368. It seems that Rabanis had gone himself to Rome in order to convince the pope about his Catholic faith. In July 1368, Urban V asked the

15 For this office during the byzantine period, see in general A. LEONTARITOU,

(Forschungen zur byzantinischen Rechtsgeschichte. Athener Reihe, 8), Athina, 1996, p. 100.

16 F. THIRIET, Délibérations des Assemblées vénitiennes concernant la Romanie, vol. 1, Paris, 1966, p. 322, doc. 668.

17 K. D. MERTZIOS,

, 3 (1949), pp. 268-269; cf. TOMADAKIS,

18 GILL, Pope Urban V [see note 14], p. 466.

[see note 8], p. 47.

19 For Anthimos, bishop of Athens, see E. KOUNTOURA-GALAKI – N. KOUTRAKOU, Ο Άνθιμος

(2011/2012), pp. 341-359; for his presence in Crete, see N. V. TOMADAKIS,

, 37 (1962), pp. 70-74.

Latin archbishop of Crete to increase Rabanis’ authority and to oblige the Greek clergy to see him as their own “first-priest”.20 With the support of the highest religious authorities and probably with the approbation of the local political authorities Rabanis operated for a decade within Cretan society, enjoying financial benefits and privileges. However, in 1379 the Senate of Venice commanded the duke of Crete to take measures against the actions of protopapas Rabanis and his son, the protopsaltis,21 for causing problems and confusion to the Greeks of Crete (inter Grecos insule Crete).22 As long as the election of Rabanis took place just after the suppression of the St Titus’ rebellion in which the protopapas and the protopsaltis were involved rebelling against the Venetian regime,23 it is strange that the central government of Venice was unaware of the circumstances in which Rabanis obtained the office of the protopapas. According to the Senate’s decree, the right for such an election belonged, until then, to the Greek flock, cum beneplacito semper et auctoritate vestra vel regiminis Crete, eligendi et constituendi unum Grecum iuxta ritum et consuetudinem eorum. 24 At this point it is clearly testified that the philocatholic overzealousness of Rabanis was the main cause for the confusion within the Orthodox Cretan flock.

Considering the aforementioned facts we can see that until the mid-14th century, Venice maintained a tolerant attitude towards the involvement of the Latin Church on the issue of the first-priest’s election. As evidenced by the decree of 1379, this attitude was not only by reason of sharing the papal aspirations but because the central government of Venice did not entirely understand until then the relevance of the protopapas’ office for the Orthodox society. After the St Titus’ revolt and the Rabanis’ case, Venice had a serious reason to revise the conditions and the prerequisites for the election to this office, as well as for the function of the office in general. In 1394 the Senate once again censured as illegal the involvement of the Latin archbishop in the same issue.25 With a view to minimizing the continuous interferences of the Latin Church, from the beginning of the 15th century Venice started to reinvest the office of the protopapas and protopsaltis by giving extended political and religious assignments to the officers but under the supervision and the conduction of the Venetian regime and in the interest of the political, social and religious balance of the colony.

20 GILL, Pope Urban V [see note 14], p. 467.

21 George Rabanis probably obtained the office of protopapas just after July 1368 but his son should have been nominated as protopsaltis some years later since in 1371 such office was held by Nicholas Tsilios (Cilio), protopsaltus Grecorum de Candide (ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI VENEZIA [henceforth A.S.VEN.], Notai di Candia, b. 13 [Egidio Valoso], quad. 1, f. 109r).

22 M. I. MANOUSSAKAS

23 A. XIROUCHAKIS,

, 15 (1961), pp. 154-156 doc. 1.

, Alexandria, 1932, pp. 26-27.

24 MANOUSSAKAS, Βενετικὰ ἔγγραφα [see note 22], pp. 154-156 doc. 1.

25 Ibidem, pp. 156-160 doc. 2.

JOHN PLOUSIADENOS (1423?-1500)

On the one hand, the papal court’s efforts for the Latinization of Cretan society persisted during the 15th century but the Orthodox faith of the Greek flock remained unbroken. On the other hand, the continuous abstinence of the Latin clergy from their religious duties and seats constituted a constant impediment against the pope’s aspirations for the dominance of the Catholicism in Crete. This fact has to be placed in the major context of the Catholic Church’s internal schism which began in 1378 and ended with the Council of Constance in 1417.26 Although the Venetians sided with the See of Rome since the beginning, they were not substantially interested in resolving the schism before 1406, when the Venetian Cardinal Angelo Correr accessioned to the papal throne under the name of “Gregory XII”. Two years later, the Venetian pope with a circular bull threatened to abolish the positions and suspend the salary of the Latin clergy of Crete.27 The same policy was also followed by the political authorities against the interests of the Latin clergy because they had perfectly understood the importance of the Latin Church’s presence in Crete as a political-religious counterweight opposed to the resolute Orthodox society of the island. It is worth mentioning that at this period Gregory XII did not consent to the continuous demands of the Venetians for placing a prelate chosen by them in the Latin archbishopric of Crete.28 For this reason, Venice ceded the entire estate of the Latin Church to the local-political authorities and recognized at once the election of the Cretan Peter Filargis as anti-pope, under the name of “Alexander V”.29 It seems that Venice sustained great hopes for the normalization of the religious state of Crete on his prevalence.30

II. CRETE AND THE UNION OF THE CHURCHES: UNIATE TRENDS AND ANTIUNIATE RESISTANCE IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE 15TH CENTURY

When the Byzantine delegation in Florence signed the Decree of the Union in July 1439, the religious policy of Venice in Crete was broadly consolidated. Candidate priests obtained their ordination at the Venetian colony of Methone.

26 See mainly W. BRANDMÜLLER, Das Konzil von Konstanz, 1414-1418 (Konziliengeschichte. Reihe A, Darstellungen), Paderborn, 1991.

27 F. CORNER, Creta Sacra sive de Episcopis utriusque ritus Graeci et Latini in insula Cretae, vol. 2, Venezia, 1755, pp. 111-113.

28 H. NOIRET, Documents inédits pour servir à l’histoire de la domination vénitienne en Crète de 1380 à 1485 (Bibliothèque des écoles françaises d’Athènes et de Rome, 61), Paris, 1892, pp. 191-192; cf. F. THIRIET, Régestes des Délibérations du Sénat de Venise concernant la Romanie, vol. 2, Paris, 1959, p. 74 doc. 1288, p. 79 doc. 1315.

29 Cf. G. FEDALTO, Il grande scisma d’occidente e l’isola di Creta (1378-1417), in Δ΄Διεθνὲς Κρητολογικὸν Συνέδριον (Ηράκλειο, 29 Αυγούστου-3 Σεπτεμβρίου 1976), vol. 2, Athina, 1981, pp. 94-96.

30 F. THIRIET, La situation religieuse en Crète au début du XVe siècle, in Byz, 36 (1966), p. 209.

The protopapas and the protopsaltis were the direct supervisors of the Greek clergy’s activity in Crete. Adherent to the Catholicism and to the Venetian regime, these ecclesiastical officers were excluded from the jurisdiction of the Latin archbishop of Crete and they answered only to the local political authorities, viz. the duke of Crete and his councillors. In regard to the Latin clergy, Martin V had recognized the rights of all the prelates who were placed to the Latin bishoprics of Crete creating the ideal circumstances for the reinstatement of the Latin priests in their positions. Pope Martin V was also well-known for his Uniate tendencies since the time of his election.31 In 1425 Martin V promoted Fantino Valaresso as Latin archbishop of Crete.32 Valaresso was already been a dynamic supporter of the Union and later papal delegate to the European courts.33 At the same time, Martin V set up the mission of the Dominican monk Simon De Candia in Crete. Around the mid-15th century both of them will be the most significant components of the papal effort for the dominance of the Uniate faith within the Orthodox Cretan society.

After the outcome of the Council of Florence in July 1439, Fantino Valaresso was appointed by Eugene IV to propagate the Union’s Decree in Crete. As archbishop of Crete and by following the papal instructions, Valaresso strongly campaigned for the prevalence of the unionism until his death in 1443. His dogmatic treatise Libellus de ordine generalium conciliorum et unione florentina, written around 1442 and dedicated to the Pope Eugene IV, testifies Valaresso’s Uniate zealoussness and gives information about the religious situation in Crete right after the Council of Florence. Encouraged by Marinos Falieros and Paolo Dotti,34 the archbishop tried to point out the dogmatic differences between Orthodoxies and Catholics according to the inferences of the past ecumenical synods and to illustrate the rightness of the Union to the Cretan society. Valaresso’s contribution to the Uniate mobilization is mentioned in a letter of the Cretan scribe Michael Kalophrenas35 to the Uniate patriarch

31 V. LAURENT, Les «Mémoires» du Grand Ecclésiarque de l’église de Constantinople Sylvestre Syropoulos sur le concile de Florence (1438-1439) IX, (Concilium Florentinum. Documenta et Scriptores, Series B), Paris, 1971, pp. 108-110.

32 C. EUBEL, Hierarchia catholica medii aevi sive Summorum pontificum, S. R. E. cardinalium, ecclesiarum, antistitum series... e documentis tabularii praesertim Vaticani collecta, digesta, edita, II (ab anno 1431 usque ad annum 1503 perducta), vol. 2, Münster, 1914 (repr. Padova, 1960), p. 216.

33 V. PERI, Tre lettere inedite a Fantino Vallaresso ed il suo catechismo attribuito a Fantino Dandolo, in Umanesimo e Rinascimento a Firenze e Venezia. Miscellanea di Studi in onore di Vittore Branca, vol. 3, Firenze, 1983, pp. 41-67.

34 B. SCHULTZE, Fantinus Vallaresso, Archiepiscopus Cretensis. Libellus de ordine generalium conciliorum et unione florentina, II. 2. (Concilium Florentinum Documenta et Scriptores, Series B), Roma, 1944, p. xvii n. 4. For Falieros and Dotti, see A. VAN GEMERT, The Cretan Poet Marinos Falieros, in Θησαυρίσματα, 14 (1977), pp. 7-70 and G. DI RENZO VILLATA, Paolo Dotti, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 41 (1992), pp. 543-548.

35 PLP 10738; RGK 2A, nr. 328; RGK 3A, nr. 460.

JOHN PLOUSIADENOS (1423?-1500)

of Constantinople Metrophanes II:

[...].36 Furthermore, the Uniate priest Gratianos calls him:

[...].37 In their letters, Kalophrenas and Gratianos did not miss to report the problems which the Union provoked within Cretan society, the existence of the ἐναντιοφρόνων

ἀγρίων. Because of the religious resistance of the Cretan Orthodox flock, resentment and incertitude were vividly expressed by Valaresso for the success of his mission.38 Metrophanes II suggested the Orthodox Cretan flock to accept the Union of the Churches. 39 A different letter of reaction arrived by Metrophanes’ successor, Gregory III Mammas, who had also threatened anathema to the anti-Uniate clerics.40 Gregory III realized from the beginning the difficulty of Valaresso’s mission and for that reason suggested that the archbishop should have acted with caution in order to avoid religious revolts, especially from the Orthodox part.41 On the other hand, the Venetian authorities were acting against every public anti-Uniate expression with a view to maintaining balance in their colony.

The importance of Crete as a Uniate-operated centre is also testified by the fact of the incessant relations of Simon De Candia with the island since 1437, when the Venetian authorities appointed him as abbot in St Anthony’s tou Makry monastery.42 On June 30, 1443, the local authorities, for unknown reasons, removed the Dominican monk and replaced him with the secular

36 Sp. LAMBROS

in

(1904), pp. 52-55 doc. 2; cf. N. V. TOMADAKIS,

37 V. LAOURDAS, Αἱ ταλαιπωρίαι

, in EEBS, 21 (1951), pp. 142-144 doc. 2.

Γρατιανοῦ, in Κρητικὰ Χρονικά, 5 (1951) (Κρητικὰ Παλαιογραφικά, 11), p. 246.

38 SCHULTZE, Fantinus Vallaresso [see note 34], pp. 3-4; cf. Z. N. TSIRPANLIS, Τὸ κληροδότημα τοῦ καρδιναλίου Βησσαρίωνος γιὰ

(1439-17ος αἰ.) (Ἀριστοτέλειον Πανεπιστήμιον

, 12), Thessaloniki, 1967, p. 39.

39 LAMBROS, Μιχαὴλ

[see note 36], pp. 51-52 doc. 1; I. OUDOT, Patriarchatus Constantinopolitani Acta Selecta (Sacra Congrezione per la Chiesa orientale. Codificazione canonica orientale. Fonti, Serie II, 3), Città del Vaticano, 1941, pp. 174-175 doc. 30.

40 See the letter of George Trapezountios “Περὶ

,

, in PG 161, col. 865B-C. For the letter, see J. MONFASANI, Collectanea Trapezuntiana. Textes, Documents, and Bibliographies of George of Trebizond (Medieval & Renaissance texts & studies, 25 [Renaissance Texts Series, 8]), Bringhamton, 1985, p. 234.

41 TOMADAKIS, Μιχαὴλ

[see note 36], p. 129.

42 TSIRPANLIS, Τὸ κληροδότημα [see note 38], pp. 42-43 n. 4. For the monastery see mainly A. PAPADIA-LALA,

. Oriens Graecolatinus, 4), Athina, 1996, pp. 35-60.

Michele Rugeri.43 Two years later, on July 21, 1445, the central government judged Rugeri’s assignment as illegal and reinstated Simon to the abbey because dictus locus solitus est dari sacerdotibus et religiosis viris sicut in ipso erat et steterat in pacifica possessione venerabilis et religiosis viri fratris Simon de Candida, Ordinis Predicatorum. 44 From another source we learn that Simon left the priorship of the abbey in 1448 and returned on May 14, 1451, thanks to the recommendations of the pope.45 At the same time on his reinstatement by decision of the central government, the local Venetian authorities once more cancelled Simon’s assignment because the incomings of the abbey were significantly reduced during his priorship and they replaced him with the cleric Francesco Rugeri, son of Michele.46 It is uncertain which of the two clerics finally prevailed; though it is quite certain that Simon had left the monastery during the period 1448-1451 because of some mission assigned by Pope Nicholas V. It is worth noticing that at least from 1429 Simon possessed the title of “prior provincialis” of the Dominicans in the Levant.47 Indeed, on September 6, 1448, the pope charged the haereticae pravitatis inquisitori et provinciali [sic] provinciae Graeciae, Ordinis Praedicatorum to prevent the accession of the Latins to the Uniate dogma by emphasizing the decisions of the Decree signed in Florence in 1439.48 During that period, the acceptance of the Union from the Orthodoxies was not the only dogmatic question which worried the Roman See; this fact should be viewed inside the wider context of the pope’s mobilization for the establishment and the expansion of the Catholic faith in the Levant. It needs to be remembered that in such a mission the Latin religious orders had a great conduciveness.49 It seems that Simon owned the office of

43 A.S.VEN., Duca di Candia, b. 2, quad. 19 (=21), f. 73v. It is worthy to mention that similar assignments to seculars were common in this monastery until the 17th century (PAPADIA-LALA, Ευαγή και νοσοκομειακά ιδρύματα [see note 42], pp. 48-49).

44 A.S.VEN., Avogaria di Comun, reg. 3649 (raspe), f. 92r; cf. the Appendix IV, doc. 3; cf. also A.S.VEN., Duca di Candia, b. 2, quad. 19 (=21), f. 73v. Those documents confirm Tsirpanlis’ supposition about Simon’s pause and reinstatement during the years 1437-1451 (TSIRPANLIS, Τὸ κληροδότημα [see note 38], p. 47).

45 Ibidem, p. 247 doc. 8.

46 Z. N. TSIRPANLIS, Κατάστιχο εκκλησιών

, 23), Ioannina, 1985, pp. 257-259 doc. 185 I-II.

(1248-1548). Συμβολή

(

47 R.-J. LOENERTZ, Fr. Simon de Crète, inquisiteur en Grèce et sa mission en Crète, in Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum, 6 (1936), p. 378. For the office of “prior provincialis”, see G. R. GALBRAITH, The Constitution of the Dominican Order, 1216 to 1360 (Publications of the University of Manchester. Historical series, 44), Manchester, 1925, pp. 125-131.

48 Bullarum diplomatum et privilegiorum sanctorum romanorum pontificum. Taurinensis editio locupletior facta: Collectione novissima plurium brevium, epistolarum, decretorum actorumque S. Sedis a s. Leone Magno usque ad praesens [...], vol. 5, Torino 1860, pp. 100-101. Evidently, because of a ‘lapsus calami’, the bull’s scribe skipped the word “priori” before the word “provininciali”.

49 See mainly N. I. TSOUGARAKIS, The Latin Religious Orders in Medieval Greece, (12041500) (Medieval Church studies, 18), Turnhout, 2012, pp. 275-310. Especially for the presence

JOHN PLOUSIADENOS (1423?-1500)

“prior provincialis” for thirty years since, in October 1457, Pope Callixtus III cited him as dilecto filio Simoni de Candia, Ordinis fratrum Predicatorum, professori ac priori provinciali provincie Grecie eiusdem Ordinis and officially nominated him as inquisitor in the Levant and Cyprus. 50 These missions of Simon (1448-1457) seem to be mentioned by the Uniate scholar George Trapezountios in his letter sent to the Cretan clergy in September 1457: πρῶτον

51 In the phrase “

” Trapezountios was not alluding to the anti-Uniates of the Levant but to all the heretics of the Greek territories with a view to implying a Catholic dimension on Simon’s mission in favour of all the Christians ἐν Ἑλλάδι 52

The issue of the Churches’ Union on the island of Crete constituted only a part of a farther mission of Simon, which was also related to the pope’s bull of September 3, 1457. In this document, Callixtus III seems to know very well that the Greek-Orthodox clericis ubilibet existentes were not respecting the decisions of the Council of Florence and were not making mention of the pope during the liturgy. The second part of the bull was wholly dedicated to the matter of the Filioque with the intention that Spiritus Sancti a sacerdotibus Graecis explicite et manifeste ponatur in Symbolo, ut fides ad iustitiam teneatur in corde, et ad salutem omnium eius fiat oris confessio, se tamquam filii obedientiae semper sacrosanctae Ecclesiae Romanae matris suae per omnia conformantes [...].53 Accordingly, two days later, the pope delegated Simon to announce the bull to the Cretan clergy.54 Furthermore, the bull of September 3, 1457, clearly inspired the treatise Περὶ

which Trapezountios addressed to the Cretan flock since Simon’s mission and the pope’s bulls were mentioned within it:

of Dominicans in the Levant, see C. DELACROIX-BESNIER, Les dominicains et la chrétienté grecque aux XIVe et XVe siècles (Collection de l’école française de Rome, 237), Roma, 1997.

50 G. HOFMANN, Papst Kalixt III. und die Frage der Kircheneinheit im Osten, in Miscellanea Giovanni Mercati (ST, 123), vol. 3 (Letteratura e storia bizantina), Città del Vaticano, 1946, p. 213.

51 PG 161, col. 829Α [

]; cf. LOENERTZ, Fr. Simon de Crète [see note 47], p. 374; see below, p. 11.

52 In the same text George distinguishes the “Christians” from the “heretics”: Ὄτι

[...] (PG 161, col. 848B).

53 Bullarum diplomatum et privilegiorum [see note 48], vol. 5, pp. 139-140.

54 For the bull of September 5, 1457, see R. -J. LOENERTZ, O. P., Les dominicains byzantins Théodore et André Chrysobergès et les négociations pour l’Union des églises grecque et latine de 1415 à 1430, in Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum, 9 (1939), p. 47.

INTRODUCTION

The Uniate mobilization in Crete, viz. the mission of Simon De Candia as well as the advisory treatise of George Trapezountios, was enforced during that period by the circular letter of the Uniate patriarch Gregory III Mammas to the Orthodox clergy of the island. As we mentioned above, Gregory III threatened by anathema all those who refused to accept the decisions of the Council of Florence. It is important to observe that, accordingly to Trapezountios’ text, the patriarch did not address his letter to all Cretans but only to the Cretan clergy as did Trapezountios with his own treatise:

Undoubtedly, it was not a coincidence that the pope himself, through Simon’s mission, gave great importance to the dogmatic identity of the Cretan clergy. Just a few years earlier, around 1448, the Uniate Cardinal Isidore of Kiev had assured the pope that significant part of the Greek population in Constantinople and in the Levant had already joined the Union and he suggested eventual solutions for the normalization of the relationship between Uniates and anti-Uniates in Cyprus, Rhodes, Euboea, Methone, Corone without mentioning the important Venetian colony of Crete.57 That was probably because Isidore knew very well that, since the time of Urban V, the island of Crete had been chosen by the papal court as the main territory target for the planting and the gradual diffusion of the Catholic faith in the Levant. The Cretan-Orthodox clergy constituted the epicentre of the Uniate propaganda which had been raised on the island through the religious activities and operations of the protopapas George Rabanis, the archbishop Fantino Valaresso and the Dominican monk Simon De Candia, who

55 The author separates the times of Simon’s missions by mentioning as πρῶτον his anti-heretic action and after that (ἔπειτα) his consultative operation in Crete. Considering that the second mission began on September 5, 1457, we have already indicated that his anti-heretic delegacy was preceded. On the other hand, it has to be remembered that Callixtus III officially designated Simon as inquisitor in the Greek territory and in Cyprus on October 2, 1457, viz. one month after the beginning of his mission in Crete. Moreover, inside that latest bull is mentioned the experientia which Simon had attained until then by challenging the heresies. Apart from his certain participation in the surveillance mission over the Latins in 1448 on the side of the inquisitor, it seems that Simon continued to operate against the heretics of the Greek territory until October 1457, when the pope finally decided to officially nominate him as inquisitor of the Levant. At last, it has to be noted that George Trapezountios could not allude to the October’s bull because in his work there is no mention of Simon’s jurisdiction in Cyprus. Considering that George was in Rome at that period and he was fully aware of the facts (see the passage: Σίμων, ἱερομόναχος

[...] [PG 161, col. 829Α]), the time of his treatise should be collocated in September 1457.

56 PG 161, col. 865B-C; cf. LOENERTZ, Fr. Simon de Crète [see note 47], pp. 375-376.

57 G. MERCATI, Scritti d’Isidoro il cardinale Ruteno, e codici a lui appartenuti che si conservano nella Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (ST, 46), Roma, 1926, pp. 37-39, 54-55; cf. J. GILL, The Council of Florence, Cambridge, 1959, pp. 389-390.