Introduction

I write against darkness, confusion, forgetfulness, death? To better understand and make people understand. (To understand is to transform the world.)

Jean Starobinsky

I.1. Objectives and methodological framework

What if we set off on a research path through the construction of the world? A path without prejudice1 trying to find answers to the eternal questions – Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? This is the title of a painting by Paul Gauguin, started by the Symbolist painter in 1897 and completed the following year, influenced by a period of distress marked by the death of the artist’s daughter and his own suicide attempt. Gauguin’s masterpiece, while it appears to be dedicated to the cycle of existence, nevertheless poses many questions; therefore, it has been suggested that the work means that there are no answers to the questions that the artist posed himself – and us – via his panoramic interrogator [WIL 13]. However, since its inception, the human adventure has been about finding answers. Thus, what were Gauguin’s real motivations when he asked Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? His canvas encourages us to ask ourselves, in continuity with the questions he raises: how can we try to analyze human society and untangle the web of the spatial–temporal saga? And how can we

1 “Without prejudice” here means “factors defined without prejudice”. Thus, the reasoning will not be based on factors previously chosen, in order to test whether or not they appear to be associated with the construction of societies, but by analyzing the potential societal role of the factors that will emerge from the itinerary constituting the scientific thread of this book, through the contributions of a set of disciplines ranging from anthropology to sociology, via archeology, biology, climatology, economics, geography and history.

untie the invisible threads (if indeed such threads exist) that guide us, our species, through its unconscious strategies, the necessities of daily life and the river of its imagination?

At a time when these questions were being heavily considered, the author of this reflection found no detailed answers to them. Moreover, he came to the idea that his condition as a Homo sapiens of the 21st Century may not be the ideal subject to study, unless he relied (in terms of transdisciplinarity) on the most recent scientific data, the complexity of the paths of a species that emerged in an archaic form at least 300,000 years ago [HUB 17]. This follows a gradual, even punctuated evolutionary pattern [STR 16], whose origin would be 6–7 million years earlier (assuming that the first hominids were close to the species Sahelanthropus tchadensis) [BRU 02]; even billions, since the appearance of life, in the form of filamentous bacteria, date back 3.8–4.3 billion years [DOD 17], while in terms of the Earth, for its part, 4.5 billion years [KRI 11].

In any case, the author has set himself the objective of studying, as “a man responsible for himself and others”, the determinants of the trajectory of humanity, as well as the characteristics of the sapiens with which this trajectory appears to be associated, and the “mechanisms” that may have generated disharmony within human societies. Mechanisms whose decoding could lead to a humanity that, better aware of the factors of imbalance that affect it, would be in a better position to act, so that sapiens, once the imbalances correct themselves, would be better able to work together and feel that they are all part of the world’s future. These are indeed perspectives that can only be favorable to the involvement – and positive motivation – of the ultra-social animal, articulated around contact and exchanges, i.e. the human being [TOM 14; WIL 13], which, if he/she is in a position of listening and ability to trust, is generally able to raise his/her level of initiative and social involvement, whereas if he/she lives in rejection and oblivion, then he/she tends to let him/herself be won over by passivity and plunge into distrust. Thus, any person left on the roadside, because they are poor, indigent, invisible or considered useless, constitutes a potential loss, with a view to optimizing human functioning.

In order to try to respond in full knowledge of the facts to these objectives, a scientific journey of discovery and analysis of societal constructions will be undertaken within space-time, associating humans with the planet, the Earth, which protects us from the great organized chaos, i.e. the Universe. In order to travel outside a planned approach, no element of this journey will be decided in advance, and the analysis will adopt an exploratory research strategy developed in nine steps through Chapters 1–9 of this book. When elements of knowledge appear unavailable, hypotheses considered plausible may be incorporated into the reasoning, despite the over-interpretations that may result from this practice [LAH 96], which is ultimately considered a necessary risk [DES 96]. When a stage is reached, the theme

of the next stage will be decided “right away”, in accordance with the lessons of the previous stage, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, with the objective of research; and this, until the reflection is completed and methods of balancing human societies are proposed, will be in coherence with the functioning of the world that the journey will have highlighted (“to understand is to transform the world”) [STA 16]. The analysis used as a vehicle for the journey will be based mainly on data from peer-reviewed publications2 and also on summary books, maps and statistical series, as well as reflections on historical routes and Internet pathways. In addition, in order to facilitate the follow-up of the process, a summary of brief reminders of knowledge will be given throughout the reflection, and some key ideas will be reiterated or supported.

Finally, the added value of this book, the drafting of which is very concise, could come from: an original decoding of human dynamics combining human sciences, biological sciences and sciences from the Earth; the demonstrative contribution of descriptive statistics and case–control reasonings, a reflection attempting to free oneself from the mechanisms of distancing (creating distance between oneself and reality) [ETZ 17] and crushing undesirable ideas, which the human cortex can activate using biological mechanisms of elimination and substitution [BEN 12; VAN 17a]; and an analysis suggesting avenues of work, the relevance of which can be specified by subsequent studies, following the collaborations that the book may have generated.

However, whatever factors associated with the operation of human societies may be suggested by the route: is it possible to act on the human journey, given its strength of inertia? In other words, its propensity to be guided by a range of rituals, habits and desires to stay in place. This is possible in connection with the affective impregnations and social interactions that shape our species, as well as with universal conservation mechanisms that lead living beings to reproduce what exists, in order to better guarantee our sustainability. This could indeed be affected, if living beings were not dominated by conservation, by subscribing to the genetic heritage of a species as a result of selection pressures (the constraints that lead to the evolution of species’ characteristics) dictated by the ever-changing environmental circumstances, changes in the structure of expression3 of certain genes that prove to be incapable of improving the adaptation of the species to the environment’s changes which could therefore be harmful to the species.

2 “Peer review” [SPI 12] denotes a critical analysis of research submitted for publication by specialist readers contributing to scientific journals. The purpose of such an evaluation is to ensure the relevance and unpublished nature of a manuscript that is a candidate for publication.

3 Biochemical processes by which active genes (15,000 to 30,000 in humans) trigger the synthesis of amino acids and proteins necessary for cellular functioning. Gene expression is itself regulated by proteins capable of activating, inhibiting or modulating gene function, and thus modifying the biological effects of genes, so that cellular metabolism is adapted to the environment.

Nevertheless, humans could try to free themselves from the conservatism of evolution by voluntarily implementing a reflection on the ways and means of strengthening the species. To this end, the sapiens could try, by taking international dialogue further, to lay the foundations without taboo for the “general interest of humanity”, through the establishment of planetary frameworks for reflection dedicated to the definition of this supra-consideration and the acquisition by humans, following the concretization of their general interest, of significantly increased faculties for dialogue, solidarity and cooperation. Traits whose diffusion within our species could lead, in the long term and by a classic selection pressure (insofar as the cooperative state of mind has become a “vital human behavior”), to their being integrated into our genetic makeup, like being engraved in marble. This path, which would constitute a “voluntary domestication of the human being by themself”, appears to be biologically possible. Indeed, it has been shown in canines that dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), a domestic species if ever there was one [BOT 17], carry variants of the GTF2I and GTF2IRD1 genes (linked to the hypersociability of the canine species) different from those carried by the emblematic wild species, the wolf (Canis lupus) [VON 17]. However, there are a few minor drawbacks: first, the direction of the evolution4 of a species and the expression of its genes, particularly at cerebral level [KHA 06], is not guaranteed, as evolutionary mechanisms may also be subject to uncontrollable factors [GOU 02], and second, to implement its general interest, humanity must be aware of the determinants of its species’ trajectory, which does not seem to be the case, hence the realization of this book.

What should be particularly difficult to achieve, in the reflection to come, if not to be confronted with the limits of sapiens and our own inadequacies, will be to be able to consider human societies, not only with the eyes of the Chimène of our time and the glasses of our particular lives, but also with other views (of different periods, cultures and lifestyles), in order to achieve the most multi-centric and global vision possible of the factors that seem to have governed the path of human societies.

I.2. Getting off to a good start

For us to “get off to a good start”, it seems necessary to recall that we all belong: to the animal kingdom; to the vertebrates branch; to the mammal class; to the order of primates; to the hominid family; to the genus Homo and to the species Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 (Homo: generic name; sapiens: specific epithet;

4 A process of species transformation that takes place over generations. This process takes the form of changes in the structure or expression of certain genes, from environmental pressure, cultural and social changes and also random events. This is done through natural selection, which promotes the reproduction and survival of individuals who are most adaptable to their environment and most in tune with the sociocultural preferences of their fellow creatures.

Linnaeus: description of the species; 1758: year of description). The year 1758, as associated with Homo sapiens, actually corresponds to the period during which Carl Linnaeus (Figure I.1) attributed his Latin name to the human species; this was in the 10th edition of Systema naturæ, a famous book in which humans are mentioned for the first time as part of the active primate family (“ranked first”) [LIN 14].

I.1. Carl Linnaeus portrait at the age of 32 by Johan Henrik Scheffel (source: Uppsala University)

As for the general functioning of sapiens, it should be explained, like other species, by physical and biological characteristics modulated by genetic evolution, environmental fluctuations and their interactions, as well as by a fraction of “chance” [KRI 18]. Also, through the exceptional efficiency of the human brain system [HAN 17], whose genetic evolution is intensely studied [ENA 16] and which makes us capable of triggering, as well as solving, says director Joël Pommerat, “acute conflicts between collective and individual interests triggered through circumstances of fusion and crystallization involving thought, action and imagination”; conflicts that Pommerat staged with talent in reference to the French Revolution, in his play Ça ira (1) Fin de Louis5 [POM 16]. While these considerations point to the idea of “human particularism”, such an observation must be modulated by the fact that many mammals exhibit behaviors, in terms of play [FRÖ 16a], signs of affection or signs of hierarchical allegiance, that are displayed in good similarity with the behaviors of sapiens, even if differences emerge (in this way, animals play without using rules) [HUX 66]. Moreover, some adaptation mechanisms to environmental changes, including adaptation to the cold, come from “evolutionary convergences” between species through the variation in the expression of genes that humans share with other mammals [LIB 15].

5 The title can be roughly translated as “It’ll turn out okay (1) End of Louis”.

Figure

Returning to behavioral proximities, perhaps one of the most revealing facts in this area is that some animals present ways of being almost universally found in religious practices [SEM 08], such as particular attitudes towards death or ritualistic behaviors, which have been particularly observed in “stone collector” chimpanzees (who repeatedly throw stones into the hollow of a tree stump in a manner unrelated to a utilitarian cause, for example, food) [KÜH 16]. Attitudes associated with death appear in great apes, as well as in cetaceans [REG 18] – attitudes, ceremonies and behaviors that amount to protection, emotional support or bereavement [AND 10; KIN 13; VAN 17b]. Thus, it seems clear from these observations and convergences that the idea of a continuum – as disturbing as it is expected – between the non-human and the sapiens animals is well-established. Unless the duality to be considered (in addition to the duality of the human and the animal) is the one that might be seen to exist in the future, that makes us afraid or makes us give in to trends; on the one hand, the ordinary sapiens and on the other, the augmented sapiens, using biological, robotic and computer technologies that give this superhuman an almost divine power [HAR 17].

When we engage with unknown territories, let us hope for instructive and exciting moments to navigate in the path of a human being; and to be able, when this navigation is completed, to see a clearer profile. This is the objective of the journey that is beginning, the ins and outs of the process of constructing humanity and the societies that structure it.

Let us begin.

History of Color

1.1. Linnaeus and us

The preamble completed: a question comes to mind; the answer to which was not known to the author when he asked himself and which seems to be a useful starting point for a research journey within humanity: what presentation does Linnaeus make of the species Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758, which he is the “scientific creator” of in his famous system for species classification? Famous because it was thought of more than 250 years ago, somehow in a framework that current knowledge with subjective and erroneous1, yet not formally superseded by another type of classification based on consensus. So let us dive into Systema Naturæ, under the heading concerning the human being [LIN 14]. What is interesting in this interpretation, apart from the fact that man would be “a frugivore in the Tropics and a carnivore in other areas where plants are less nourishing”, or that there would be a Homo ferus, a kind of wild human being, is that the Swedish naturalist divided sapiens into four main types. Here is an extract from the very surprising descriptions (translated from Latin into English here by the author):

– “the American:

- he is reddish, angry and has a right way of carrying himself;

- black hair, straight, fat, wide nostrils, chin almost free of a beard;

1 If we take the example of flounder and skate with reference to Linnaeus’ classification, these animals are considered, as flat-bodied fish, a closely related species. However, according to current knowledge, human beings are in fact evolutionarily closer to flounder than flounder is to skate. Indeed, skate is a chondrichthyan, i.e. it has a cartilage skeleton, while sapiens and flounder are osteichthyans, insofar as their skeleton is bony. Thus, humans and flounder have a common ancestor closer to them than is the common ancestor to these two fish. This example illustrates how Linnaeus’ classification can be incorrect, even if the names given to the species by the naturalist are still valid.

- he is stubborn, happy with his fate, loving freedom;

- he is painted with red lines, interlaced in different ways;

- he is governed by custom;

– the European:

- he is white, hot-headed, muscly;

- blond, long and thick hair, blue eyes;

- he is inconsistent, ingenious, inventive;

- he wears tight clothing;

- he is governed by laws;

– the Asian:

- he is yellowish, melancholic, strict;

- dark hair, brown eyes;

- he is severe, lavish, stingy;

- he wears large clothing;

- he is governed by public opinion;

– the African:

- he is black, impassive, has a weak constitution;

- very dark frizzy hair, velvet skin, flat nose, fat lips, breastfeeding women have long breasts;

- he is cunning, lazy, careless;

- he rubs his body with oil or grease;

- he is governed by the arbitrary will of his masters”.

For Linnaeus, a man from Southern Sweden, the “blond-white-blue” European was the most successful and civilized human type; the African, on the other hand, the least well-rounded and the wildest, as well as being doomed to slavery; and as for the Asian and American, other main human types considered by Linnaeus, they constituted a kind of intermediary between the African and the European. As for the philosopher Emmanuel Kant, a contemporary of Linnaeus, he also divided humans into four races (white, black, Mongolian and

Hindu), while considering the white and brown populations living “in the Old World”, between the 32nd and 52nd parallels, as the most adaptable to the diversity of climatic conditions, and the closest to the original sapiens [KAN 16]. Buffon on the other hand acknowledged, as a precursor, the influence of climate on the color of the skin when he stated, in 1749 in his Histoire Naturelle [LEC 07], that “man, white in Europe, black in Africa, yellow in Asia and red in America, is just the same man dyed the color of the climate”. As for the 17th-Century traveler and curious mind François Bernier, he can be considered a champion of the theory of human types, according to an article dated 1684 (“Nouvelle division de la Terre par les différentes espèces ou races d’hommes qui l’habitent”) in which he professes the idea of the division of humanity into races, while propelling non-Europeans to the rank of “animal-like villains”. Nevertheless, for La Fontaine and Molière, friends of Bernier, the link that the latter seemed to trace between animals and man could in fact be, beyond the European pre-eminence that he disputed, a way of distancing himself from Christian philosophy. During Bernier’s time absolute domination was starting to be challenged (according to the Christian conception, man, as “a special creation” of God, appears to escape the animal condition).

As for the “natural character of slavery ”, it was already part of Linnaeus’ concepts through his description of the African, as well as of the theories of the influential Greek philosopher Aristotle, who affirmed without hesitation in the 4th Century BCE twenty centuries before Systema Naturæ: “those who are as different [from other men] as the soul from the body or man from beast—and they are in this state if their work is the use of the body, and if this is the best that can come from them—are slaves by nature. For them it is better to be ruled in accordance with this sort of rule, if such is the case for the other things mentioned” [ARI 84a].

Another remark, concerning the Linnaean description of Homo sapiens: skin color is the first criterion put forward by the naturalist as differentiating between human types, and it therefore seems necessary to study its determinants. In addition, other a priori discriminating physical criteria (hair and eye color, lip shape) are mentioned by the great classifier, as well as certain character traits (for Linnaeus, inventiveness would be the European’s own). In fact, following recent scientific work (the sequencing of the Homo sapiens genome was only finalized in 2003) [INT 04], it has been shown that humans all derive from the same paternal and maternal lineage. Thus, there is only one maternal mitochondria lineage [CAN 87] in human cells that appears statistically from sub-Saharan Africa [MAN 07] (however, sapiens derive from several populations that have dispersed across Africa) [SCE 18]. As a result, it is within African populations that the most variations in mitochondrial DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) transmitted by mothers are

found [LI 08], a variability that would not have existed if humans and their predecessors had not lived much longer in Africa than elsewhere on the planet. Thus, molecular genetic techniques have shed a lot of light, and continue to shed more light every day, on the history of species, compared to the crude knowledge available before the development of these techniques [CAS 17].

While sapiens are genetically homogeneous, their populations would have dispersed, according to one theory, as a result of planned migrations. There would be between 220,000 and 50,000 years [HER 18], outside their original African birthplace [MOU 16]. A birthplace which nowadays genetically, the simian species is home to considered, to be the closest to man (chimpanzees and gorillas), and which is, with Asia, the birthplace of primitive monkeys [NI 13; SIG 90]. Note: while Africa is therefore seen as the birthplace of humanity – and this has been since Charles Darwin in the 19th Century [LÓP 15] researchers argue, so far without convincing from a genetic point of view, that man – appeared in Europe or Asia [ATH 17; FUS 17]. As for the migration of Homo, in addition to the habitus of their species, they have been linked to demographic phenomena [FOL 16], environmental accidents (volcanism) and climate changes that have been at the root of: the decline of forests and wetland environments; and the development of grasslands (pollen from wetland shrubs account for 20% of pollen dating back 3 million years, compared to 2% of those aged 2 million years) [COP 14]; landscape changes that may have encouraged bipedalism.

The migrations of our ancestors were also helped by their mental progress (subsistence strategies, spirit of cooperation), in connection with the increasing complexity of their psychocerebral system and the skills acquired in order to reduce their risk of extinction, during the environmental trials associated with their evolutionary journey [COL 16]. Another migratory theory – at this stage, less convincing than the previous [STR 14] – professes the appearance of sapiens, not only in Africa but also independently in other regions of the globe [BOI 11], following very old migrations of Homo out of Africa (1.5–2 million years, even more than 3 million), from which sapiens would have emerged. Migrations which, even if they did not play a role in the emergence of Homo sapiens, would have been the result of Homo erectus, capable of controlling fire and using shells as engraving tools [JOO 14], as well as other hominids, including a specimen, dating back 1.75 million years ago, which has been discovered in Indonesia [ARG 17]. In this regard, the genus Homo was enriched in 2019 with a new species, Homo luzonensis, both recent (50,000–67,000 years) and rather archaic in appearance, whose remains have been discovered in the Philippines [DÉT 19].

In the end, and regardless of its exact method of creation, Homo sapiens spread throughout the world; the result was the geographical isolation of certain human groups, given the extreme difficulty for prehistoric man to overcome natural obstacles such as the ocean or steep mountain ranges. Consequently, and with few exceptions that may have been linked to expeditions of sea adventurers, populations of isolated groups (such as South American sapiens) have only been able to reproduce among themselves; their physical traits, therefore, have been homogenized on the basis of the characteristics of their original groups. The work of molecular geneticists confirmed that, since the genetic variability between humans in the same geographical group is greater than that observed between their various groups, the genetic uniqueness of Homo sapiens prevailed over its regional variants. Thus, it is now generally considered that: 85% of humanity’s genetic diversity is linked to individual differences among all human populations; 10% of this diversity depends on the region of origin (among five major regions, sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas, Oceania, East Asia and Eurasia) and 5% are related to differences between populations within regions [REL 02]. Moreover, genetic differences between populations at continent level and intercontinental contact zones seem to be organized as gene gradients, and not as clearly separated categories [SER 04], as Linnaeus had thought of them. As a result, the concept of race appears to have no relevance to human genetic history and understanding of the adventure of sapiens.

Thus, humans all appear to come from – in addition to the same migratory and existential quest – a genetic matrix with a common basis. This implies, in support of the above, that it is unfounded to divide Homo sapiens into racial types with particular qualities and faults. The result is the creation of pseudo hierarchies, as hypothetical as they are stigmatizing. However, it would be inaccurate to deny any difference between the vague human groups that have formed following: the departure of primitive hominids from Africa; the dispersal of original Homo within continents, including returns to Africa; and the potential emergence of Homo sapiens nuclei from populations of Homo erectus and other Homo. Thus, human biodiversity, as a testament to evolution, runs counter to the instant and definitive creation of species and to the fixed and unalterable nature.

1.2. Ultraviolet and melanin

The color of the skin, which according to Linnaeus discriminates against human types carrying intrinsic defects and qualities, and which appears, as such, to be a factor in the imbalance of human constructions, is not an ethnic characteristic. Indeed, this coloration, composed of hundreds of shades, depends mainly on the

amount of ultraviolet (UV) rays to which an individual’s ancestors were subjected in the very long term [JAB 10] (short-term exposure to the sun, as we have all seen, also has a temporary influence on skin color). To withstand the solar stress they face, dark-skinned sapiens near the equator2 have a melanin production system (UVabsorbing brown-black pigments and protectors against solar stress) that is more effective than that of their light-skinned counterparts. Thus, light-skinned humans, who migrated from Europe to equatorial Africa and stayed there for 10,000 years, inevitably saw their skin change, provided they lived a good part of their time outside, and not shut away in air-conditioned houses writing tweets, draped in long dressing gowns. In any case, if the current phase of global warming were to prove very sustainable, humanity would tend to darken in terms of their skin.

Melanin, in addition to pigmenting the skin, colors the hair and the iris brown/black, thus protecting them from the aggressive action of UV rays, just like the protection they provide for so-called photosensitive vitamins, and in particular vitamin B9 [BOR 14]. The latter is necessary for bone mineralization, brain maturation and maintenance of cognitive function. While genetic mutations (useful or undesirable modifications of the nucleotide sequence of a gene) can, in sapiens, decrease – the case of the appearance of blue eyes in some Europeans –, or even annihilate – the case of albinos – the level of melanin production (Figure 1.1), “the low-melanin-producing white man” is thus the adaptation of the human body to the lowest amount of solar energy hitting the ground in the regions of origin of the same “white man” ancestors. In addition, the synthesis of vitamin D, which is essential for binding calcium to bone and bone growth, depends essentially on the amount of UV rays received by the human body (which synthesizes it through the action of UV, through a cholesterol derivative) and, more incidentally, on the amount of vitamin D contained in food. Thus, for human populations in areas with low levels of sunlight to synthesize enough vitamin D, it is very useful for them to have fair skin. Indeed, if the skin of sapiens in parts of the world with little sunlight were dark: it would absorb, through melanin, the little UV available in these regions, a small quantity of vitamin D would be synthesized and metabolism, particularly bone metabolism, of these humans would be disrupted [JAB 02]. This would be especially true if the diet of these sapiens was not rich in vitamin D, as was the diet of our ancestors prior to the domestication of plants and animals, which was mainly composed of fruits and vegetables with low vitamin D content.

2 At the equator, solar radiation is perpendicular to the ground, resulting in a greater amount of energy received per m2 in this area than in regions near the poles, where solar radiation reaches the ground obliquely. The rays reaching the equatorial regions also have less distance to travel in the atmosphere, which means that they collide less frequently with air molecules and thus lose less energy.

Figure 1.1. African albino child (source: Lars Plougmann, CCBY). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/barnouin/construction.zip

Finally, genetic adaptations of skin color [MYL 07], hair density (hairless skin expels heat more than hairy skin) and sweat mechanisms have resulted in increased resistance of sapiens to climate variations and better adaptability to threats they may face. Indeed, these physical characteristics play a role, not only in terms of thermal regulation but also in the effectiveness of concealment, which appears to be a major factor of survival when existence, like that of primitive sapiens, required protection from predators, effective hunting and resistance to frostbite and disease.

Another factor to consider, in relation to skin color is that everywhere on the planet, including in areas where dark skin is favored by populations (such as Tasmania), women have lighter skin than their male counterparts. This particularity corresponds, in fact, to an adaptation of our species in relation to the important calcium needs of pregnant and breastfeeding women. Indeed, a greater capacity for vitamin D synthesis, particularly through lighter skin, makes it possible to protect mothers more effectively from the harmful consequences of hypovitaminosis D, in terms of the viability of their infants and the strength of their skeletons.

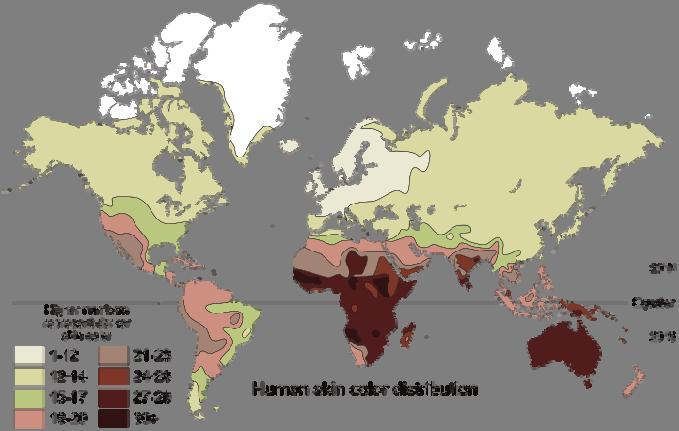

At this point, the journey in the color of the skin leads us to the following question: what is the distribution map of skin color on a global level? Such mapping should indeed show, given what has just been stated, that skin is darker around the equator and lighter when one moves away from it. In fact, only one map, published in 1941 in the book by the Italian geographer Renato Biasutti,

Le razze et i popoli della terra, seems to have been drawn to illustrate the distribution of the color of human skin, according to the regions of the planet [BIA 41].

1.3. The skin map

Georges Chaplin, a geographer at the University of Pennsylvania, interviewed for the purposes of our scientific journey, was indeed not aware of any other skin mapping than that established by Biasutti in the late 1930s (Figure 1.2), despite him being the co-author of many expert articles on skin color [JAB 00]. Before exploring and commenting on this map, it is useful to know that Biasutti made extrapolations based on missing empirical data, and the geographer was one of some 300 Italian scientists who, by necessity or conviction, publicly supported the racial laws enacted by the Benito Mussolini government in 1938 against Jews.

Figure 1.2. Human skin color map [BIA 41; JAB 00]. The higher the number of people in an area on a six-class color scale, the more pigmented the skin of the populations residing in that area is (source: The Ogre, CCBY). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/barnouin/construction.zip

If we look carefully at Biasutti’s map, an anomaly appears; indeed, Central and South America, which are the largest land areas after Africa to be crossed by the equator and the tropics, appear much “whiter” than expected. Thus, of the eight skin color classes mapped by Biasutti, using the Von Luschan chromatic scale [SWI 13], none of the three darkest skin classes appear to be represented within the South American hemisphere.

Unlike South America, the color class assigned to Australia by Biasutti and his collaborators, while it corresponds more or less to the expected climate, appears to describe skin that is far too dark in comparison to what is known about the reality of the Australian population. The explanation for this discrepancy can only be linked to an error by Biasutti, knowing that at the end of the 1930s, Australia had 6 million inhabitants, the vast majority of whom came from the United Kingdom and that, following European colonization, Australia’s indigenous dark-skinned population in this case the Aborigines – which had come very close to extinction, had only a very small population in 1940, less than 2% of the Australian population [HOU 72].

What could be the cause of the anomaly highlighted by Biasutti’s work on the American continent? The less dark than biologically expected skin coloring of South American inhabitants could be explained, at least partially, by the fact that human migrations that reached the American continent from Asia and the Bering Strait between 15,000 and 50,000 years ago [MEL 09], had long lived in regions far from the equator.

These populations had therefore become accustomed to clothing and shelter, ways of life that may have promoted the lightening of their skin, in reference to what is now known about the changes in skin pigmentation of the sapiens who originally emigrated from Africa.

Christopher Columbus was spurred on by the idea of finding wealth and allies by navigating the New World, with a view to liberating Jerusalem. Then in the hands of the Turks, he carried out maritime expeditions in the 15th Century on behalf of the Spanish sovereigns. On his first voyage, which allowed him to reach Cuba, Columbus noted in his book that “the skin of the inhabitants of Cuba was (logically) the color of the Canary Islands, neither black nor white”. However, two things must be known (apart from the fact that Columbus believed he discovered “the East Indes”, and not America), which give full value to Columbus’s testimony: at the beginning of his navigation to “the Indes”, the Genoese navigator, who left Spain in 1492, stopped over in the Canary Islands for almost a month (Figure 1.3) and thus had every opportunity to observe their indigenous inhabitants (the Guanches, decimated in 1495 by Spanish troops). After leaving the Canaries (latitude of Las Palmas: 29.5° N), “the navigator-adventurer”, heading west, reached the Bahamas, Cuba (latitude of Havana: 23.8° N) and Haiti (St. Domingue), stepping into the shoes of discoverer of the “New World”. Thus, Christopher Columbus’s exceptional testimony tends to validate the now accepted hypothesis that the sapiens’ skin color depends significantly on the latitude at which their distant ancestors lived. But on this subject, taking the example of Cuba and its discovery by Columbus, for the explanation what can be the skin color of Cubans today (white at 60%, black or mixed African at 40%) among which, the color of the indigenous population, which Columbus could observe in 1493, no longer seems visible?

Figure 1.3. Schematic outward journey of Christopher Columbus’s first voyage of discovery (1492–1493), from Spain to the West Indies (Bahamas–Cuba–Haiti (St. Domingue)) via the Canary Islands (source: Uwe Dedering, CCBY (background map)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/barnouin/construction.zip

1.4. New World Drama

Here are some answers to the question in the previous paragraph: after the arrival of the Spanish settlers, who settled in Cuba and Haiti (St. Domingue), then in Mexico and throughout Central and South America – with the exception of Brazil, which was given to the Portuguese by the Treaty of Tordesillas, which in 1494 formalized the sharing of the New World, a drastic reduction in the size of the indigenous population, including those of Cuba and Haiti, began. Bear in mind, this reduction also applied, following the European colonization, to the North American Indians, whose number decreased from 10 million to a few hundred thousand between the 16th and 19th Centuries. If we look back at the case of Cuba, 30 years after the arrival of the Spanish and the colonization, more than three quarters of the indigenous population disappeared from this island; and only 1000 remained in 1600, of the 100,000 which would have populated Cuba before its conquest. As for Haiti (St. Domingue), the island where Columbus landed on his first voyage, there were reportedly 300,000 indigenous people in 1492, 50,000 in 1510, 16,000 in 1530 and only 1,000 in 1540 [DEB 91]. This was the case in Cuba, Haiti and elsewhere, in connection with the desire to enrich [GOM 10]: massacres, executions, enslavement, collective suicides of indigenous people and the spread of diseases (smallpox, typhus, syphilis, influenza) against which indigenous people were not immune. These diseases would have been a decisive factor in the collapse of the indigenous populations [BEN 13]; diseases they would have contracted as a result of their contact with the settlers, or even as the result of epidemics the latter would have exacerbated.

As for the result of this deadly sequence – is still relevant today [DAV 77; PAR 18a] – which is the subject of unresolvable controversy between negationists and defenders of native cultures [DOR 06] and the inhumanity of which was denounced by Father Bartolomé de las Casas in his Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (1552) [WAL 10], it seems clear: by the end of the 16th Century, 60–70 million indigenous Latin Americans disappeared from where they had lived for 10,000 years, i.e. more than 80% of the original population, although these estimates may according to sources, vary significantly [GUT 77]. In any case, as far as St. Domingue is concerned we can refer, to the work of Pierre Chaunu [CHA 59], who described “the catastrophic evolution of the island’s indigenous population, on which all the documents and testimonies converge”.

“Eradication of the Native American population”, which forever changed the map of people and cultures, appears to constitute, in addition to a health disaster, the greatest work of societal destruction to be attributed to greed. Destruction that the nations that were part of it tended to distance themselves from, highlighting “the fabulous discovery” of America and its adventure book side. Thus, the abandonment of the Native Americans to their fatal fate was often approached from the cultural perspective of a “dialogue” between civilizations, and referred to imponderable causes dominated by health, rather than being appreciated in its complex, terrible and disturbing entirety. Moreover, no internationally commissioned analysis seems to have been conducted to study, in a multidisciplinary and peaceful manner, the lessons to be drawn in terms of loss of civilization, health risks and criminology, from the actions of the conquistadors and their successors. This is despite citizens’ associations from the Americas starting to document these issues more and more, and despite the actions of the Mexican president. Firstly, in 2019, the president asked Spain to recognise the abuses committed against indigenous people during its conquest – indeed, a century after the conquest of Mexico by Hernán Cortés in 1519, the indigenous population of central Mexico fell by 97%, according to a document from the archives of the Count of Salvatierra, Viceroy of New Spain from 1642 to 1648 [COO 79] – and secondly, the president announced that he would apologize for the “the extermination” of the indigenous people (Yaquis and Maya), perpetrated while Mexico was independent.

To continue on the subject of skin color, it should be pointed out that Cuba’s current black population, like that of other Latin American countries, corresponds to the survivors of the 10–15 million Africans that European nations transported to America and the West Indies, like goods, between the 16th and 19th Centuries. This was done in order to enslave these populations (who were to be “renewed” on average every 10 years) [WAH 12] and to replace the indigenous population, whom the settlers had helped to decimate, after having used them as means of production in the mines (silver, mercury, gold) and farms (tobacco, sugar cane, cotton), and whose property they had taken over. Thus, in the Bolivian silver mines of Potosi alone,

7–8 million indigenous and African slaves died during the colonial period (from 1545, the year of discovery of silver by the Spaniards, to 1825, the year of Bolivia’s independence) [BRO 12].

Finally, the lighter than expected skin tone of populations from South and Central America – apart from that of the indigenous people whose population had been sharply reduced – appears to be a consequence of massive swathes of “predominantly white” European immigrants. Indeed, between the 18th and 20th Centuries, more than 20 million Europeans, mainly Germans, Spaniards, French, Italians, Poles and Portuguese, reached the El Dorado of the New World in the hope of improving their lives and fleeing their past, or because they were forced into exile because of their ideas or legal troubles. Although it is very difficult to classify Latin American populations according to their origins (statistics reflect as much the aspirations for whiteness, Africanness or Indianity, or the language used, as the reality of their origins). Here are some significant figures: no Caribbean country currently has more than 10% of its population being “purely” indigenous; only two countries in South America (Bolivia and Peru) and two in Central America (Belize and Guatemala) exceed this 10% ; and Latin America as a whole, according to statistics for the period 2000–2008, only had 6% of indigenous people, hence its surprising pallor. Nevertheless, ECLAC (UN Regional Commission) estimates that for early 2010, more than 8% of the population of South and Central America was of indigenous origin (with the highest percentages in Bolivia, Guatemala and Peru), in line with a trend towards a relative increase in the indigenous population [UN 14a].

These figures are generally in agreement with Biasutti’s map, which shows that in South America, it is the inhabitants of present-day Peru and Bolivia who seem to have more pigmented skin than the average in this hemisphere. But why do Bolivia and Peru have populations that are composed more of descendants of the original indigenous populations than those of others? To try to explain, it can be noted that Bolivia and Peru are characterized by high average altitude, – both countries have 18 out of 41 peaks above 6,000 m in Latin America – rather inhospitable climates and a large proportion of mountainous and forested areas that are unfavorable to field crops. Bolivia also has no maritime access, but it is the poorest country in South America. Thus, these characteristics would not have been detrimental to the indigenous populations who were well acclimatized to the harsh living conditions of Bolivia and Peru. On the contrary, such characteristics would have attracted few European emigrants, despite the promulgation – without much success – in the 19th Century of laws designed to encourage their immigration.

As for the conquest of the Inca Empire, it was only carried out by a few hundred men, following the landing near the current Peruvian port of Tumbes in 1528, of a handful of Spanish adventurers, under the leadership of Francisco Pizarro. In the

end, Pizarro succeeded in defeating Emperor Atahualpa and his army, with a troop of 168 soldiers equipped with weapons (arquebuses, cannons, muskets) and terrorizing caparisoned horses. The defeat was thanks to his ability to take advantage of the weaknesses and mistakes of his opponents (in this case, the division of indigenous elites and the underestimation, by the Inca emperor, of the threat represented by the conquistadors). Following the conquest, a thousand settlers was sufficient to extract, with the help of slaves and renegade indigenous peoples, precious metals – the possession of which was highly attractive to the Spanish and their allies.

1.5. Foundations of an unfounded theory

Commentary on the human skin color map has projected us into dramatic and destabilizing episodes in the history of sapiens, from which we must draw necessary conclusions for the future, in terms of the development of human societies. As for the unfounded division of sapiens into types with physical appearances and unequal qualities, as Linnaeus engraved in marble, what could be the original written roots of this? As for the Book of Hammurabi (the name of a sovereign of the Kingdom of Babylon), the oldest and most complete legal code to have come down to us – which is said to date back 3,800 years – makes no reference to the question of human typologies. Egyptian hieroglyphics are also perfectly silent on this question, knowing that the inhabitants of ancient Egypt would have been quite close to the populations established in the Levant and the Near East [SCH 17], even if the question of the origin of the Pharaonic Egyptians is not yet fixed.

As for the Old Testament, part of the Bible recounts – in the book of Genesis –the story of Noah and his sons just after the Flood (which is the most universal human myth, along with that of the creation of the world). It tells us that Noah, “father of all people”, was drunk on wine [HER 11] and was observed, while denuded, by one of his three sons; in this case Ham, considered in biblical mythology as the ancestor of African people. However, seeing his father’s nakedness was part of the divine prohibitions in the biblical tradition; thus Noah informed of his son’s inappropriate conduct, cursed Canaan (one of Ham’s four sons) in return, condemning him to be “a slave of slaves to his brothers”. From this episode on, it was ambiguously stated, particularly in the Livre de l’ordre de succession des générations (summary of the holy history and collection of tales written around the year 500), that Ham and his descendants would have had their skin darkened following Noah’s condemnation.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to date the origin of these semantic shifts, as well as to affirm that they were intended to create a link between slavery and black skin, as Benjamin Braude did in Cham et Noé. Race et esclavage entre judaïsme, christianisme et Islam [BRA 02]. However, it is Ham’s curse that seemed to be the

main driving force, in the 18th and 19th Centuries, for the justification of racial slavery in Europe [CHR 77] and America [BRI 75]. However, as early as the 18th Century, the distortion of biblical writing (which makes no discriminatory allusion to skin color) was put to use in the book Enquête minutieuse sur la posterité noire de Cham en Éthiopie by Lutheran Jean-Louis Hannemann, author for whom, “the black population, wherever they live, are cursed and destined for slavery for thousands of generations”, in order to justify the slave trade. A slave trade (transport of goods from one country to another) which Europeans, the Portuguese as early as 1441, then the English, Spanish, French, Dutch and Italian, organized with local accomplices to make the colonization3 of America profitable. It was also established in the United States (thus, the American federal census of 1860 counted 4 million slaves, out of 31 million residents). Here again, it seems, justifications stemming from the “curse”.

Just as the secular texts of the first civilizations do not keep track of it, no founding text of the great religions therefore advocates any pre-eminence – or disqualification – of any particular ethnic type [HER 11], depending, in particular, on skin color (the founding texts of these religions even go in the opposite direction overall). Thus, there is no inevitability at the root of ethnic discrimination. It nevertheless appears to be a major factor in unfounded hatred and sterile controversies, and it must be considered particularly costly, in terms of cohesion and the achievement of human societies. If this burden – which appears to have been misappropriated from religious myth – continues to endure, it is probably because two sides existthat respond to and complement each other: the idiotic disparagement of the darkest skin and the thoughtless glorification of the lightest complexions.

1.6. Deviations in the 19th and 20th Centuries

The supremacy of white skin was particularly on the agenda in the 19th Century, as a kind of accompaniment to the civilizing mission that Europeans embraced at that time, as a counterpoint to the second great wave of colonization that was taking place, focusing on Africa and Asia, not to mention Oceania. In order to justify these

3 Few subjects are the object of so many’s passion as colonization, especially among anthropologists [FLA 12]. Thus, before defining the notion of colonization, it should be recalled that the present reflection is not intended to distribute good and bad points in terms of the unfolding of human history but to describe the sequences of this history in order to try to understand them and to reveal, through the faults in these sequences, ways of solidifying and better achieving humanity. Colonization therefore refers to the occupation, organization and exploitation of a territory under the influence of an external power, for profit, strategy or demographic reasons. The settlers, as representatives, entrepreneurs or ordinary citizens of the occupying power, manage the colony according to their own interests and those of the metropolis, while contributing more or less significantly to the development of the colonized territory.