Principles of Inorganic Materials Design 3rd

Edition

John N. Lalena

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/principles-of-inorganic-materials-design-3rd-edition-jo hn-n-lalena/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Fundamentals

of Inorganic Glasses 3rd Edition Mauro

https://ebookmass.com/product/fundamentals-of-inorganicglasses-3rd-edition-mauro/

Database Principles: Fundamentals of Design, Implementation, and Management 3rd Edition Carlos Coronel

https://ebookmass.com/product/database-principles-fundamentalsof-design-implementation-and-management-3rd-edition-carloscoronel/

eTextbook 978-0134454177 Building Construction: Principles Materials and Systems (3rd Edition)

https://ebookmass.com/product/etextbook-978-0134454177-buildingconstruction-principles-materials-and-systems-3rd-edition/

Principles of Microeconomics 8th Edition N. Gregory Mankiw

https://ebookmass.com/product/principles-of-microeconomics-8thedition-n-gregory-mankiw/

Principles

of Economics 8th Edition N Gregory Mankiw

https://ebookmass.com/product/principles-of-economics-8thedition-n-gregory-mankiw/

The Principles of Constitutionalism N W Barber

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-principles-ofconstitutionalism-n-w-barber/

Materials for Biomedical Engineering: Inorganic Microand Nanostructures

Valentina Grumezescu

https://ebookmass.com/product/materials-for-biomedicalengineering-inorganic-micro-and-nanostructures-valentinagrumezescu/

Materials for Biomedical Engineering - Inorganic Microand Nanostructures

Valentina Grumezescu

https://ebookmass.com/product/materials-for-biomedicalengineering-inorganic-micro-and-nanostructures-valentinagrumezescu-2/

Principles of Microeconomics, Asia-Pacific Edition N.

Gregory Mankiw

https://ebookmass.com/product/principles-of-microeconomics-asiapacific-edition-n-gregory-mankiw/

PrinciplesofInorganic MaterialsDesign

PrinciplesofInorganicMaterialsDesign

ThirdEdition

JohnN.Lalena PhysicalScientist

DavidA.Cleary GonzagaUniversity

OlivierB.M.HardouinDuparc ÉcolepolytechniqueInstitutPolytechniqueParis

Thiseditionfirstpublished2020 ©2020JohnWiley&SonsInc.

Editionhistory:

“JohnWiley&SonsInc.(1e,2005)”

“JohnWiley&SonsInc.(2e,2010)”

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedinaretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyform orbyanymeans,electronic,mechanical,photocopying,recordingorotherwise,exceptaspermittedbylaw.Adviceon howtoobtainpermissiontoreusematerialfromthistitleisavailableathttp://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

TherightofJohnN.Lalena,DavidA.Cleary,andOlivierB.M.HardouinDuparctobeidentifiedastheauthorsofthis workhasbeenassertedinaccordancewithlaw.

RegisteredOffice

JohnWiley&Sons,Inc.,111RiverStreet,Hoboken,NJ07030,USA

EditorialOffice

111RiverStreet,Hoboken,NJ07030,USA

Fordetailsofourglobaleditorialoffices,customerservices,andmoreinformationaboutWileyproductsvisitusat www.wiley.com.

Wileyalsopublishesitsbooksinavarietyofelectronicformatsandbyprint-on-demand.Somecontentthatappearsin standardprintversionsofthisbookmaynotbeavailableinotherformats.

LimitofLiability/DisclaimerofWarranty

Inviewofongoingresearch,equipmentmodifications,changesingovernmentalregulations,andtheconstantflowof informationrelatingtotheuseofexperimentalreagents,equipment,anddevices,thereaderisurgedtoreviewand evaluatetheinformationprovidedinthepackageinsertorinstructionsforeachchemical,pieceofequipment,reagent, ordevicefor,amongotherthings,anychangesintheinstructionsorindicationofusageandforaddedwarningsand precautions.Whilethepublisherandauthorshaveusedtheirbesteffortsinpreparingthiswork,theymakeno representationsorwarrantieswithrespecttotheaccuracyorcompletenessofthecontentsofthisworkandspecifically disclaimallwarranties,includingwithoutlimitationanyimpliedwarrantiesofmerchantabilityorfitnessforaparticular purpose.Nowarrantymaybecreatedorextendedbysalesrepresentatives,writtensalesmaterialsorpromotional statementsforthiswork.Thefactthatanorganization,website,orproductisreferredtointhisworkasacitationand/or potentialsourceoffurtherinformationdoesnotmeanthatthepublisherandauthorsendorsetheinformationor servicestheorganization,website,orproductmayprovideorrecommendationsitmaymake.Thisworkissoldwiththe understandingthatthepublisherisnotengagedinrenderingprofessionalservices.Theadviceandstrategiescontained hereinmaynotbesuitableforyoursituation.Youshouldconsultwithaspecialistwhereappropriate.Further,readers shouldbeawarethatwebsiteslistedinthisworkmayhavechangedordisappearedbetweenwhenthisworkwaswritten andwhenitisread.Neitherthepublishernorauthorsshallbeliableforanylossofprofitoranyothercommercial damages,includingbutnotlimitedtospecial,incidental,consequential,orotherdamages.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

Names:Lalena,JohnN.author.|Cleary,DavidA.,1957– author.|Duparc, OlivierB.M.Hardouin,author.

Title:Principlesofinorganicmaterialsdesign/JohnN.Lalena,U.S. DepartmentofEnergy,DavidA.Cleary,GonzagaUniversity,OlivierB.M. HardouinDuparc,E’colePolytechnique.

Description:Thirdedition.|Hoboken,NJ,USA:Wiley,2020.|Includes bibliographicalreferencesandindex.

Identifiers:LCCN2019051901(print)|LCCN2019051902(ebook)|ISBN 9781119486831(hardback)|ISBN9781119486916(adobepdf)|ISBN 9781119486763(epub)

Subjects:LCSH:Chemistry,Inorganic–Materials.|Chemistry, Technical–Materials.

Classification:LCCQD151.3.L352020(print)|LCCQD151.3(ebook)|DDC 546–dc23

LCrecordavailableathttps://lccn.loc.gov/2019051901

LCebookrecordavailableathttps://lccn.loc.gov/2019051902

CoverDesign:Wiley

CoverImages:Molecularmodel,illustration©VICTORHABBICKVISIONS/SCIENCEPHOTOLIBRARY/Getty Images,Bluecrystals©assistantua/GettyImages

Setin9.5/12.5ptSTIXTwoTextbySPiGlobal,Pondicherry,India

PrintedinUnitedStatesofAmerica

Contents

ForewordtoSecondEdition xiii

ForewordtoFirstEdition xv

PrefacetoThirdEdition xix

PrefacetoSecondEdition xx

PrefacetoFirstEdition xxi Acronyms xxiii

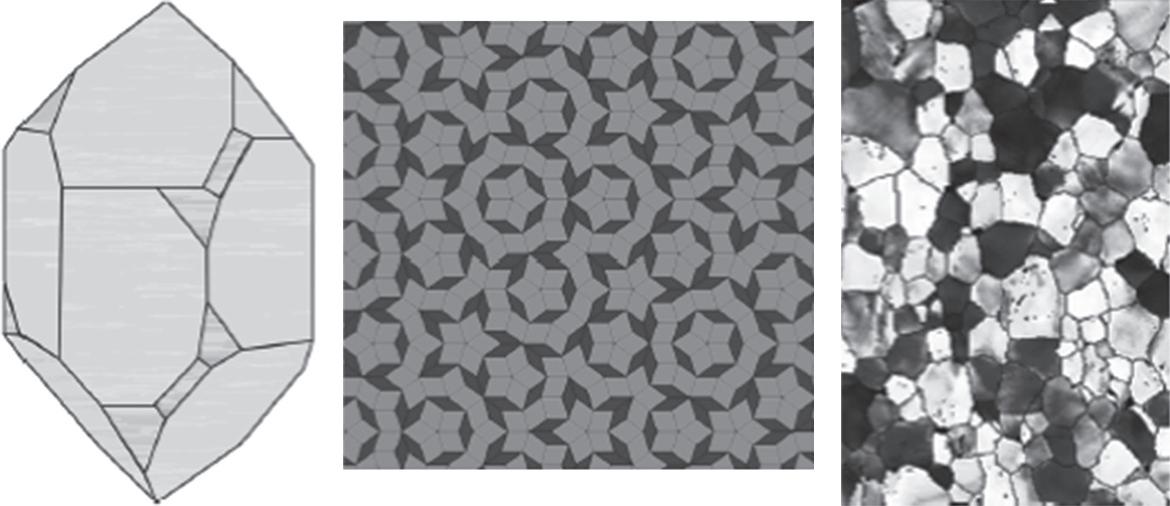

1CrystallographicConsiderations 1

1.1DegreesofCrystallinity 1

1.1.1MonocrystallineSolids 2

1.1.2QuasicrystallineSolids 3

1.1.3PolycrystallineSolids 4

1.1.4SemicrystallineSolids 5

1.1.5AmorphousSolids 8

1.2BasicCrystallography 8

1.2.1CrystalGeometry 8

1.2.1.1TypesofCrystallographicSymmetry 12

1.2.1.2SpaceGroupSymmetry 17

1.2.1.3LatticePlanesandDirections 27

1.3Single-CrystalMorphologyandItsRelationshiptoLatticeSymmetry 32

1.4TwinnedCrystals,GrainBoundaries,andBicrystallography 37

1.4.1TwinnedCrystalsandTwinning 37

1.4.2CrystallographicOrientationRelationshipsinBicrystals 39

1.4.2.1TheCoincidenceSiteLattice 39

1.4.2.2EquivalentAxis–AnglePairs 44

1.5AmorphousSolidsandGlasses 46

1.5.1OxideGlasses 49

1.5.2MetallicGlassesandMetal–OrganicFrameworkGlasses 51

1.5.3Aerogels 53 PracticeProblems 53 References 55

2MicrostructuralConsiderations 57

2.1MaterialsLengthScales 57

2.1.1ExperimentalResolutionofMaterialFeatures 61

2.2GrainBoundariesinPolycrystallineMaterials 63

2.2.1GrainBoundaryOrientations 63

2.2.2DislocationModelofLowAngleGrainBoundaries 65

2.2.3GrainBoundaryEnergy 66

2.2.4SpecialTypesof “Low-Energy” Boundaries 68

2.2.5GrainBoundaryDynamics 69

2.2.6RepresentingOrientationDistributionsinPolycrystallineAggregates 70

2.3MaterialsProcessingandMicrostructure 72

2.3.1ConventionalSolidification 72

2.3.1.1GrainHomogeneity 74

2.3.1.2GrainMorphology 76

2.3.1.3ZoneMeltingTechniques 78

2.3.2DeformationProcessing 79

2.3.3ConsolidationProcessing 79

2.3.4Thin-FilmFormation 80

2.3.4.1Epitaxy 81

2.3.4.2PolycrystallinePVDThinFilms 81

2.3.4.3PolycrystallineCVDThinFilms 83

2.4MicrostructureandMaterialsProperties 83

2.4.1MechanicalProperties 83

2.4.2TransportProperties 86

2.4.3MagneticandDielectricProperties 90

2.4.4ChemicalProperties 92

2.5MicrostructureControlandDesign 93 PracticeProblems 96 References 96

3CrystalStructuresandBindingForces 99

3.1StructureDescriptionMethods 99

3.1.1ClosePacking 99

3.1.2Polyhedra 103

3.1.3The(Primitive)UnitCell 103

3.1.4SpaceGroupsandWyckoffPositions 104

3.1.5StrukturberichtSymbols 104

3.1.6PearsonSymbols 105

3.2CohesiveForcesinSolids 106

3.2.1IonicBonding 106

3.2.2CovalentBonding 108

3.2.3DativeBonds 110

3.2.4MetallicBonding 111

3.2.5AtomsandBondsasElectronChargeDensity 112

3.3ChemicalPotentialEnergy 113

3.3.1LatticeEnergyforIonicCrystals 114

3.3.2TheBorn–HaberCycle 119

3.3.3Goldschmidt’sRulesandPauling’sRules 120

3.3.4TotalEnergy 122

3.3.5ElectronicOriginofCoordinationPolyhedrainCovalentCrystals 124

3.4CommonStructureTypes 127

3.4.1Iono-covalentSolids 128

3.4.1.1 AX Compounds 128

3.4.1.2 AX2 Compounds130

3.4.1.3 AX6 Compounds132

3.4.1.4 ABX2 Compounds132

3.4.1.5 AB2X4 Compounds(SpinelandOlivineStructures)134

3.4.1.6 ABX3 Compounds(PerovskiteandRelatedPhases)135

3.4.1.7 A2B2O5 (ABO2.5) Compounds(Oxygen-DeficientPerovskites)137

3.4.1.8 AxByOz Compounds(Bronzes)139

3.4.1.9 A2B2X7 Compounds(Pyrochlores)139

3.4.1.10SilicateCompounds 140

3.4.1.11PorousStructures 141

3.4.2MetalCarbides,Silicides,Borides,Hydrides,andNitrides 144

3.4.3MetallicAlloysandIntermetallicCompounds 144

3.4.3.1ZintlPhases 147

3.4.3.2NonpolarBinaryIntermetallicPhases 149

3.4.3.3TernaryIntermetallicPhases 151

3.5StructuralDisturbances 153

3.5.1IntrinsicPointDefects 154

3.5.2ExtrinsicPointDefects 155

3.5.3StructuralDistortions 156

3.5.4BondValenceSumCalculations 158

3.6StructureControlandSyntheticStrategies 162 PracticeProblems 165 References 167

4TheElectronicLevelI:AnOverviewofBandTheory 171

4.1TheMany-BodySchrödingerEquationandHartree–Fock 171

4.2ChoiceofBoundaryConditions:Born’sConditions 177

4.3Free-ElectronModelforMetals:FromDrude(Classical)toSommerfeld (Fermi–Dirac) 179

4.4Bloch’sTheorem,BlochWaves,EnergyBands,andFermiEnergy 180

4.5ReciprocalSpaceandBrillouinZones 182

4.6ChoicesofBasisSetsandBandStructurewithApplicativeExamples 188

4.6.1FromtheFree-ElectronModeltothePlaneWaveExpansion 189

4.6.2FermiSurface,BrillouinZoneBoundaries,andAlkaliMetalsversusCopper 191

4.6.3UnderstandingMetallicPhaseStabilityinAlloys 193

4.6.4TheLocalizedOrbitalBasisSetMethod 195

4.6.5UnderstandingBandStructureDiagramwithRheniumTrioxide 196

4.6.6ProbingDOSBandStructureinMetallicAlloys 199

4.7BreakdownoftheIndependent-ElectronApproximation 200

4.8DensityFunctionalTheory:TheSuccessortotheHartree–FockApproachinMaterials Science 202

4.9TheContinuousQuestforBetterDFTXCFunctionals 205

4.10VanderWaalsForcesandDFT 208

PracticeProblems 210

References 210

5TheElectronicLevelII:TheTight-BindingElectronicStructureApproximation 213

5.1TheGeneralLCAOMethod 214

5.2ExtensionoftheLCAOTreatmenttoCrystallineSolids 219

5.3OrbitalInteractionsinMonatomicSolids 221

5.3.1 σ-BondingInteractions 221

5.3.2 π-BondingInteractions 225

5.4Tight-BindingAssumptions 229

5.5QualitativeLCAOBandStructures 232

5.5.1Illustration1:TransitionMetalOxideswithVertex-SharingOctahedra 236

5.5.2Illustration2:ReducedDimensionalSystems 238

5.5.3Illustration3:TransitionMetalMonoxideswithEdge-SharingOctahedra 240

5.5.4Corollary 243

5.6TotalEnergyTight-BindingCalculations 244 PracticeProblems 246 References 246

6TransportProperties 249

6.1AnIntroductiontoTensors 249

6.2MicroscopicTheoryofElectricalTransportinCeramics:TheRoleofPointDefects 254

6.2.1Oxygen-Deficient/MetalExcessandMetal-Deficient/OxygenExcessOxides 256

6.2.2SubstitutionsbyAliovalentCationswithValenceIsoelectronicity 261

6.2.3SubstitutionsbyIsovalentCationsThatAreNotValenceIsoelectronic 263

6.2.4NitrogenVacanciesinNitrides 266

6.3ThermalConductivity 268

6.3.1TheFreeElectronContribution 269

6.3.2ThePhononContribution 271

6.4ElectricalConductivity 274

6.4.1BandStructureConsiderations 278

6.4.1.1Conductors 278

6.4.1.2Insulators 279

6.4.1.3Semiconductors 281

6.4.1.4Semimetals 290

6.4.2Thermoelectric,Photovoltaic,andMagnetotransportProperties 292

6.4.2.1Thermoelectrics 292

6.4.2.2Photovoltaics 298

6.4.2.3GalvanomagneticEffectsandMagnetotransportProperties 301

6.4.3Superconductors 303

6.4.4ImprovingBulkElectricalConductioninPolycrystalline,Multiphasic,and CompositeMaterials 307

6.5MassTransport 308

6.5.1AtomicDiffusion 309

6.5.2IonicConduction 316 PracticeProblems 321 References 322

7HoppingConductionandMetal–InsulatorTransitions 325

7.1CorrelatedSystems 327

7.1.1TheMott–HubbardInsulatingState 329

7.1.2Charge-TransferInsulators 334

7.1.3MarginalMetals 334

7.2AndersonLocalization 336

7.3ExperimentallyDistinguishingDisorderfromElectronCorrelation 340

7.4TuningtheM–ITransition 343

7.5OtherTypesofElectronicTransitions 345 PracticeProblems 347 References 347

8MagneticandDielectricProperties 349

8.1PhenomenologicalDescriptionofMagneticBehavior 351

8.1.1MagnetizationCurves 354

8.1.2SusceptibilityCurves 355

8.2AtomicStatesandTermSymbolsofFreeIons 359

8.3AtomicOriginofParamagnetism 365

8.3.1OrbitalAngularMomentumContribution:TheFreeIonCase 366

8.3.2SpinAngularMomentumContribution:TheFreeIonCase 367

8.3.3TotalMagneticMoment:TheFreeIonCase 368

8.3.4Spin–OrbitCoupling:TheFreeIonCase 368

8.3.5SingleIonsinCrystals 371

8.3.5.1OrbitalMomentumQuenching 371

8.3.5.2SpinMomentumQuenching 373

8.3.5.3TheEffectofJTDistortions 373

8.3.6Solids 374

8.4Diamagnetism 376

8.5SpontaneousMagneticOrdering 377

8.5.1ExchangeInteractions 379

8.5.1.1DirectExchangeandSuperexchangeInteractionsinMagneticInsulators 382

8.5.1.2IndirectExchangeInteractions 387

8.5.2ItinerantFerromagnetism 390

8.5.3NoncollinearSpinConfigurationsandMagnetocrystallineAnisotropy 394

8.5.3.1GeometricFrustration 394

8.5.3.2MagneticAnisotropy 397

8.5.3.3MagneticDomains 398

8.5.4FerromagneticPropertiesofAmorphousMetals 401

8.6MagnetotransportProperties 401

8.6.1TheDoubleExchangeMechanism 402

8.6.2TheHalf-MetallicFerromagnetModel 403

8.7Magnetostriction 404

8.8DielectricProperties 405

8.8.1TheMicroscopicEquations 407

8.8.2Piezoelectricity 408

8.8.3Pyroelectricity 414

8.8.4Ferroelectricity 416 PracticeProblems 421 References 422

9OpticalPropertiesofMaterials 425

9.1Maxwell’sEquations 425

9.2RefractiveIndex 428

9.3Absorption 436

9.4NonlinearEffects 441

9.5Summary 446 PracticeProblems 446 References 447

10MechanicalProperties 449

10.1StressandStrain 449

10.2Elasticity 452

10.2.1TheElasticityTensors 455

10.2.2ElasticallyIsotropicandAnisotropicSolids 459

10.2.3TheRelationBetweenElasticityandtheCohesiveForcesinaSolid 465

10.2.3.1BulkModulus 466

10.2.3.2Rigidity(Shear)Modulus 467

10.2.3.3Young’sModulus 470

10.2.4Superelasticity,Pseudoelasticity,andtheShapeMemoryEffect 473

10.3Plasticity 475

10.3.1TheDislocation-BasedMechanismtoPlasticDeformation 481

10.3.2PolycrystallineMetals 487

10.3.3BrittleandSemi-brittleSolids 489

10.3.4TheCorrelationBetweentheElectronicStructureandthePlasticity ofMaterials 490

10.4Fracture 491 PracticeProblems 494 References 495

11PhaseEquilibria,PhaseDiagrams,andPhaseModeling 499

11.1ThermodynamicSystemsandEquilibrium 500

11.1.1EquilibriumThermodynamics 504

11.2ThermodynamicPotentialsandtheLaws 507

11.3UnderstandingPhaseDiagrams 510

11.3.1UnarySystems 510

11.3.2BinarySystems 511

11.3.3TernarySystems 518

11.3.4MetastableEquilibria 522

11.4ExperimentalPhaseDiagramDeterminations 522

11.5PhaseDiagramModeling 523

11.5.1GibbsEnergyExpressionsforMixturesandSolidSolutions 524

11.5.2GibbsEnergyExpressionsforPhaseswithLong-RangeOrder 527

11.5.3OtherContributionstotheGibbsEnergy 530

11.5.4PhaseDiagramExtrapolations:TheCALPHADMethod 531 PracticeProblems 534 References 535

12SyntheticStrategies 537

12.1SyntheticStrategies 538

12.1.1DirectCombination 538

12.1.2LowTemperature 540

12.1.2.1Sol–Gel 540

12.1.2.2Solvothermal 543

12.1.2.3Intercalation 544

12.1.3Defects 546

12.1.4CombinatorialSynthesis 548

12.1.5SpinodalDecomposition 548

12.1.6ThinFilms 550

12.1.7PhotonicMaterials 552

12.1.8Nanosynthesis 553

12.1.8.1LiquidPhaseTechniques 554

12.1.8.2Vapor/AerosolMethods 556

12.1.8.3CombinedStrategies 556

12.2Summary 558

PracticeProblems 559

References 559

13AnIntroductiontoNanomaterials 563

13.1HistoryofNanotechnology 564

13.2NanomaterialsProperties 565

13.2.1ElectricalProperties 566

13.2.2MagneticProperties 567

13.2.3OpticalProperties 567

13.2.4ThermalProperties 568

13.2.5MechanicalProperties 569

13.2.6ChemicalReactivity 570

13.3MoreonNanomaterialsPreparativeTechniques 572

13.3.1Top-DownMethodsfortheFabricationofNanocrystallineMaterials 572

13.3.1.1NanostructuredThinFilms 572

13.3.1.2NanocrystallineBulkPhases 573

13.3.2Bottom-UpMethodsfortheSynthesisofNanostructuredSolids 574

13.3.2.1Precipitation 575

13.3.2.2HydrothermalTechniques 576

13.3.2.3Micelle-AssistedRoutes 577

13.3.2.4Thermolysis,Photolysis,andSonolysis 580

13.3.2.5Sol–GelMethods 581

13.3.2.6PolyolMethod 582

13.3.2.7High-TemperatureOrganicPolyolReactions(IBMNanoparticleSynthesis) 584

13.3.2.8AdditiveManufacturing(3DPrinting) 584

References 586

14IntroductiontoComputationalMaterialsScience 589

14.1AShortHistoryofComputationalMaterialsScience 590

14.1.11945–1965:TheDawnofComputationalMaterialsScience 591

14.1.21965–2000:SteadyProgressThroughContinuedAdvancesinHardwareand Software 595

14.1.32000–Present:High-PerformanceandCloudComputing 598

14.2SpatialandTemporalScales,ComputationalExpense,andReliabilityofSolid-State Calculations 600

14.3IllustrativeExamples 604

14.3.1ExplorationoftheLocalAtomicStructureinMulti-principalElementAlloysby QuantumMolecularDynamics 604

14.3.2MagneticPropertiesofaSeriesofDoublePerovskiteOxides A2BCO6 (A =Sr,Ca; B =Cr; C =Mo,Re,W)byMonteCarloSimulationsintheFrameworkofthe IsingModel 606

14.3.3CrystalPlasticityFiniteElementMethod(CPFEM)AnalysisforModelingPlasticityin PolycrystallineAlloys 613 References 617

15CaseStudyI:TiO2 619

15.1Crystallography 619

15.2Microstructure 623

15.3Bonding 626

15.4ElectronicStructure 627

15.5Transport 628

15.6Metal–InsulatorTransitions 632

15.7MagneticandDielectricProperties 632

15.8OpticalProperties 634

15.9MechanicalProperties 635

15.10PhaseEquilibria 636

15.11Synthesis 638

15.12Nanomaterial 639

PracticeQuestions 639 References 640

16CaseStudyII:GaN 643

16.1Crystallography 643

16.2Microstructure 646

16.3Bonding 647

16.4ElectronicStructure 647

16.5Transport 648

16.6Metal–InsulatorTransitions 650

16.7MagneticandDielectricProperties 652

16.8OpticalProperties 652

16.9MechanicalProperties 653

16.10PhaseEquilibria 654

16.11Synthesis 654

16.12Nanomaterial 656

PracticeQuestions 657 References 658

AppendixA:Listofthe230SpaceGroups 659

AppendixB:The32CrystalSystemsandthe47PossibleForms 665

AppendixC:PrinciplesofTensors 667

AppendixD:SolutionstoPracticeProblems 679

Index 683

ForewordtoSecondEdition

Materialsscienceisoneofthebroadestoftheappliedscienceandengineeringfieldssinceituses conceptsfromsomanydifferentsubjectareas.Chemistryisoneofthekeyfieldsofstudy,andin manymaterialsscienceprograms,studentsmusttakegeneralchemistryasaprerequisiteforallbut themostbasicofsurveycourses.However,thatistypicallythelasttruechemistrycoursethatthey take.Theremainderoftheirchemistrytrainingisaccomplishedintheirmaterialsclasses.Thishas servedthefieldwellformanyyears,butoverthepastcoupleofdecades,newmaterialsdevelopmenthasbecomemoreheavilydependentuponsyntheticchemistry.Thissecondeditionof PrinciplesofInorganicMaterialsDesign servesasafinetexttointroducethematerialsstudent tothefundamentalsofdesigningmaterialsthroughsyntheticchemistryandthechemisttosome oftheissuesinvolvedinmaterialsdesign.

WhenIobtainedmyBSinceramicengineeringin1981,theprimaryfieldsofmaterialsscience –ceramics,metals,polymers,andsemiconductors – weregenerallytaughtinseparatedepartments, althoughtherewasfrequentlysomeoverlap.Thiswasparticularlytrueattheundergraduatelevel, althoughgraduateprogramsfrequentlyhadmoresubjectoverlap.Duringthe1980s,manyofthese departmentsmergedtoformmaterialsscienceandengineeringdepartmentsthatbegantotakea moreintegratedapproachtothefield,althoughchemicalandelectricalengineeringprograms tendedtocoverpolymersandsemiconductorsinmoredepth.Thistrendcontinuedinthe1990s andincludedthewritingoftextssuchas TheProductionofInorganicMaterials byEvansand DeJonghe(PrenticeHallCollegeDivision,1991),whichfocusedontraditionalproductionmethods.Syntheticchemicalapproachesbecamemoreimportantasthedecadeprogressedandacademiabegantoaddressthisintheclassroom,particularlyatthegraduatelevel.Thefirsteditionof PrinciplesofInorganicMaterialsDesign strovetomakethismaterialavailabletotheupperdivision undergraduatestudent.

Thesecondeditionof PrinciplesofInorganicMaterialsDesign correctsseveralgapsinthefirst editiontoconvertitfromaverygoodcompilationofthefieldintoatextthatisveryusablein theundergraduateclassroom.Perhapsthebiggestoftheseistheadditionofpracticeproblems attheendofeverychaptersincethesecondbestwaytolearnasubjectistoapplyittoproblems (thebestistoteachit),andthisremovestheburdenofcreatingtheproblemsfromtheinstructor. Chapter1,CrystallographicConsiderations,isnewandbothreviewsthebasicinformationinmost introductorymaterialscoursesandclearlypresentsthemoreadvancedconceptssuchasthemathematicaldescriptionofcrystalsymmetrythataretypicallycoveredincoursesoncrystallographyof physicalchemistry.Chapter10,MechanicalProperties,hasalsobeenexpandedsignificantlyto provideboththebasicconceptsneededbythoseapproachingthetopicforthefirsttimeandthe solidmathematicaltreatmentneededtorelatethemechanicalpropertiestoatomicbonding,

crystallography,andothermaterialpropertiestreatedinpreviouschapters.Thisisparticularly importantasdevicesusesmalleractivevolumesofmaterial,sincethisseldomresultsinthematerialsbeinginastress-freestate.

Insummary,thesecondeditionof PrinciplesofInorganicMaterialsDesign isaverygoodtextfor severalapplications:afirstmaterialscourseforchemistryandphysicsstudents,aconsolidated materialschemistrycourseformaterialssciencestudents,andasecondmaterialscourseforother engineeringandappliedsciencestudents.Italsoservesasthebackgroundmaterialtopursuethe chemicalroutestomakethesenewmaterialsdescribedintextssuchas InorganicMaterialsSynthesisandFabrication byLalenaandCleary(Wiley,2008).Suchcoursesarecriticaltoinsurethat studentsfromdifferentdisciplinescancommunicateastheymoveintoindustryandfacetheneed todesignnewmaterialsorreducecoststhroughsyntheticchemicalroutes.

MartinW.Weiser

MartinearnedhisBSinceramicengineeringfromOhioStateUniversityandMSandPhDin MaterialsScienceandMineralEngineeringfromtheUniversityofCalifornia,Berkeley.AtBerkeley heconductedfundamentalresearchonsinteringofpowdercompactsandceramicmatrixcomposites.AftergraduationhejoinedtheUniversityofNewMexico(UNM)wherehewasavisitingassistantprofessorinchemicalengineeringandthenassistantprofessorinmechanicalengineering.At UNMhetaughtintroductoryandadvancedmaterialsscienceclassestostudentsfromallbranches ofengineering.HecontinuedhisresearchinceramicfabricationaspartoftheCenterforMicroEngineeredCeramicsandalsobranchedoutintosoldermetallurgyandbiomechanicsincollaborationwithcolleaguesfromSandiaNationalLaboratoriesandtheUNMSchoolofMedicine, respectively.

MartinjoinedJohnsonMattheyElectronicsinatechnicalservicerolesupportingtheDiscrete PowerProductsGroup(DPPG).InthisrolehealsoinitiatedJME’seffortstodevelopPb-freesolders forpowerdieattachthatcametofruitionincollaborationwithJohnN.Lalenaseveralyearslater afterJMEwasacquiredbyHoneywell.Martinspentseveralyearsastheproductmanagerforthe DPPGandthenjoinedtheSixSigmaPlusorganizationafterearninghisSixSigmaBlackBeltworkingonpolymer/metalcompositethermalinterfacematerials(TIMs).Hespentthelastseveralyears intheR&Dgroupasbothagroupmanagerandprinciplescientistwhereheleadthedevelopmentof improvedPb-freesoldersandnewTIMs.

ForewordtoFirstEdition

Whereassolid-statephysicsisconcernedwiththemathematicaldescriptionofthevariedphysical phenomenathatsolidsexhibitandthesolid-statechemistisinterestedinprobingtherelationships betweenstructuralchemistryandphysicalphenomena,thematerialsscientisthasthetaskofusing thesedescriptionsandrelationshipstodesignmaterialsthatwillperformspecifiedengineering functions.However,thephysicistandthechemistareoftencalledupontoactasmaterialdesigners, andthepracticeofmaterialsdesigncommonlyrequirestheexplorationofnovelchemistrythatmay leadtothediscoveryofphysicalphenomenaoffundamentalimportanceforthebodyofsolid-state physics.Icitethreeillustrationswhereanengineeringneedhasledtonewphysicsandchemistryin thecourseofmaterialsdesign.

In1952,IjoinedagroupattheMITLincolnLaboratorythathadbeenchargedwiththetaskof developingasquareB–Hhysteresisloopinaceramicferrospinelthatcouldhaveitsmagnetization reversedinlessthan1 μsbyanappliedmagneticfieldstrengthlessthantwicethecoercivefield strength.Atthattime,thephenomenonofasquareB–Hloophadbeenobtainedinafewironalloys byrollingthemintotapessoastoalignthegrains,andhencetheeasymagnetizationdirections, alongtheaxisofthetape.TheobservationofasquareB–HloopledJayForrester,anelectrical engineer,toinventthecoincident-current,random-accessmagneticmemoryforthedigitalcomputersince,atthattime,theonlymemoryavailablewasa16×16byteelectrostaticstoragetube. Unfortunately,thealloytapesgavetooslowaswitchingspeed.Asanelectricalengineer,JayForresterassumedtheproblemwaseddy-currentlossesinthetapes,sohehadturnedtotheferrimagneticferrospinelsthatwereknowntobemagneticinsulators.However,thepolycrystalline ferrospinelsareceramicsthatcannotberolled!Nevertheless,theAirForcehadfinancedthe MITLincolnLaboratorytodevelopanairdefensesystemofwhichthedigitalcomputerwasto beakeycomponent.Therefore,JayForresterwasabletoputtogetheraninterdisciplinaryteam ofelectricalengineers,ceramists,andphysiciststorealizehisrandom-accessmagneticmemory withceramicferrospinels.

Themagneticmemorywasachievedbyacombinationofsystematicempiricism,carefulmaterialscharacterization,theoreticalanalysis,andtheemergenceofanunanticipatedphenomenonthat provedtobeastrokeofgoodfortune.Asystematicmappingofthestructural,magnetic,andswitchingpropertiesoftheMg–Mn–Feferrospinelsasafunctionoftheirheattreatmentsrevealedthatthe spinels,inonepartofthephasediagram,weretetragonalratherthancubicandthatcompositions, justonthecubicsideofthecubic–tetragonalphaseboundary,yieldsufficientlysquareB–Hloopsif givenacarefullycontrolledheattreatment.Thisobservationledmetoproposethatthetetragonal distortionwasduetoacooperativeorbitalorderingontheMn3+ ionsthatwouldliftthecubic-field orbitaldegeneracy;cooperativityofthesitedistortionsminimizesthecostinelasticenergyand leadstoadistortionoftheentirestructure.Thisphenomenonisnowknownasacooperative

Jahn–TellerdistortionsinceJahnandTellerhadearlierpointedoutthatamoleculeormolecular complex,havinganorbitaldegeneracy,wouldloweritsenergybydeformingitsconfigurationtoa lowersymmetrythatremovedthedegeneracy.Armedwiththisconcept,Iwasablealmostimmediatelytoapplyittointerpretthestructureandtheanisotropicmagneticinteractionsthathadbeen foundinthemanganese–oxideperovskitessincetheorbitalorderrevealedthebasisforspecifying therulesforthesignofamagneticinteractionintermsoftheoccupanciesoftheoverlappingorbitalsresponsiblefortheinteratomicinteractions.TheserulesarenowknownastheGoodenough–Kanamorirulesforthesignofasuperexchangeinteraction.Thusanengineeringproblem promptedthediscoveryanddescriptionoftwofundamentalphenomenainsolidsthateversince havebeenusedbychemistsandphysiciststointerpretstructuralandmagneticphenomenaintransitionmetalcompoundsandtodesignnewmagneticmaterials.Moreover,thediscoveryofcooperativeorbitalorderingfedbacktoanunderstandingofourempiricalsolutiontotheengineering problem.Byannealingattheoptimumtemperatureforaspecifiedtime,theMn3+ ionsofacubic spinelwouldmigratetoformMn-richregionswheretheirenergyisloweredthroughcooperative, dynamicorbitalordering.Theresultingchemicalinhomogeneitiesactedasnucleatingcentersfor domainsofreversemagnetizationthat,oncenucleated,grewawayfromthenucleatingcenter.We alsoshowedthateddycurrentswerenotresponsiblefortheslowswitchingofthetapes,butasmall coercivefieldstrengthandanintrinsicdampingfactorforspinrotation.

Intheearly1970s,anoilshortagefocusedworldwideattentionontheneedtodevelopalternative energysources,anditsoonbecameapparentthatthesesourceswouldbenefitfromenergystorage. Moreover,replacingtheinternalcombustionenginewithelectric-poweredvehicles,oratleastthe introductionofhybridvehicles,wouldimprovetheairquality,particularlyinbigcities.Therefore,a proposalbytheFordMotorCompanytodevelopasodium–sulfurbatteryoperatingat3008 Cwith moltenelectrodesandaceramicNa+-ionelectrolytestimulatedinterestinthedesignoffastalkali ionconductors.MoresignificantwasinterestinabatteryinwhichLi+ ratherthanH+ istheworkingion,sincetheenergydensitythatcanbeachievedwithanaqueouselectrolyteislowerthan what,inprinciple,canbeobtainedwithanonaqueousLi+-ionelectrolyte.However,realization ofaLi+-ionrechargeablebatterywouldrequireidentificationofacathodematerialinto/from whichLi+ ionscanbeinserted/extractedreversibly.BrianSteeleofImperialCollege,London,first suggestedtheuseofTiS2,whichcontainsTiS2 layersheldtogetheronlybyvanderWaalsS2––S2–bonding;lithiumcanbeinsertedreversiblybetweentheTiS2 layers.M.StanleyWhittingham’s demonstrationwasthefirsttoreducethissuggestiontopracticewhilehewasattheExxonCorporation.Whittingham’sdemonstrationofarechargeableLi–TiS2 batterywascommerciallynonviablebecausethelithiumanodeprovedunsafe.Nevertheless,hisdemonstrationfocusedattention ontheworkofthechemistsJeanRouxelofNantesandR.SchöllhornofBerlinoninsertioncompoundsthatprovideaconvenientmeansofcontinuouslychangingthemixedvalencyofafixed transitionmetalarrayacrossaredoxcouple.AlthoughworkatExxonwashalted,theirdemonstrationhadshownthatifaninsertioncompound,suchasgraphite,wasusedastheanode,aviable lithiumbatterycouldbeachieved,buttheuseofalesselectropositiveanodewouldrequireanalternativeinsertion-compoundcathodematerialthatprovidedahighervoltageversusalithiumanode thanTiS2.Iwasabletodeducethatnosulfidewouldgiveasignificantlyhighervoltagethanthat obtainedwithTiS2 andthereforethatitwouldbenecessarytogotoatransitionmetaloxide. AlthoughoxidesotherthanV2O5 andMoO3,whichcontainvandylormolybdylions,donotform layeredstructuresanalogoustoTiS2,IknewthatLiMO2 compoundsexistthathavealayeredstructuresimilartothatofLiTiS2.ItwasonlynecessarytochoosethecorrectM3+ cationandtodeterminehowmuchLicouldbeextractedbeforethestructurecollapsed.ThatwashowtheLi1 xCoO2 cathodematerialwasdeveloped,whichnowpowersthecelltelephonesandlaptopcomputers.The

choiceofM=Co,Ni,orNi0.5+δMn0.5 δ wasdictatedbythepositionoftheredoxenergiesandan octahedralsitepreferenceenergystrongenoughtoinhibitmigrationoftheMatomtotheLilayers ontheremovalofLi.Electrochemicalstudiesofthesecathodematerials,andparticularlyofLi1 x Ni0.5+δMn0.5 δO2,haveprovidedademonstrationofthepinningofaredoxcoupleatthetopofthe valenceband.Thisisaconceptofsingularimportanceforinterpretationofmetallicoxideshaving onlyM–O–Minteractions,ofthereasonforoxygenevolutionatcriticalCo(IV)/Co(III)orNi(IV)/Ni (III)ratiosinLi1 xMO2 studies,andofwhyCu(III)inanoxidehasalow-spinconfiguration.Moreover,explorationofotheroxidestructuresthatcanactashostsforinsertionofLiasaguestspecies hasprovidedameansofquantitativelydeterminingtheinfluenceofacountercationontheenergy ofatransitionmetalredoxcouple.Thisdeterminationallowstuningoftheenergyofaredoxcouple, whichmayproveimportantforthedesignofheterogenouscatalysts.

Asathirdexample,Iturntothediscoveryofhigh-temperaturesuperconductivityinthecopper oxides,firstannouncedbyBednorzandMüllerofIBMZürichinthesummerof1986.KarlA. Müller,thephysicistofthepair,hadbeenthinkingthatadynamicJahn–Tellerorderingmightprovideanenhancedelectron–phononcouplingthatwouldraisethesuperconductivecriticaltemperature TC.HeturnedtohischemistcolleagueBednorztomakeamixed-valenceCu3+/Cu2+ compoundsinceCu2+ hasanorbitaldegeneracyinanoctahedralsite.Thisspeculationledto thediscoveryofthefamilyofhigh-TC copperoxides;however,theenhancedelectron–phononcouplingisnotduetoaconventionaldynamicJahn–Tellerorbitalordering,butrathertothefirst-order characterofthetransitionfromlocalizedtoitinerantelectronicbehaviorof σ -bondingCu:3delectronsof(x 2 y2)symmetryinCuO2 planes.Inthiscase,thesearchforanimprovedengineering materialhasledtoademonstrationthatthecelebratedMott–Hubbardtransitionisgenerally notassmoothasoriginallyassumed,andithasintroducedanunanticipatednewphysicsassociated withbondlengthfluctuationsandvibronicelectronicproperties.Ithaschallengedthetheoristto developnewtheoriesofthecrossoverregimethatcandescribethemechanismofsuperconductive pairformationinthecopperoxides,quantumcritical-pointbehavioratlowtemperatures,andan anomaloustemperaturedependenceoftheresistivityathighertemperaturesasaresultofstrong electron–phononinteractions.

Theseexamplesshowhowthechallengeofmaterialsdesignfromtheengineermayleadtonew physicsaswellastonewchemistry.Sortingoutofthephysicalandchemicaloriginsofthenew phenomenafedbacktotherangeofconceptsavailabletothedesignerofnewengineeringmaterials.Inrecognitionofthecriticalroleinmaterialsdesignofinterdisciplinarycooperationbetween physicists,chemists,ceramists,metallurgists,andengineersthatispracticedinindustryandgovernmentresearchlaboratories,JohnN.LalenaandDavidA.Clearyhaveinitiated,withtheirbook, whatshouldprovetobeagrowingtrendtowardgreaterinterdisciplinarityintheeducationofthose whowillbeengagedinthedesignandcharacterizationoftomorrow’sengineeringmaterials.

JohnB.Goodenough

JohnreceivedtheNobelPrizeinChemistryin2019.Seehisbiographypage386.