Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/high-voltage-direct-current-transmission-converters-s ystems-and-dc-grids-second-edition-dragan-jovcic/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Voltage Stability in Electrical Power Systems 1st Edition Farid Karbalaei

https://ebookmass.com/product/voltage-stability-in-electricalpower-systems-1st-edition-farid-karbalaei/

America: The Essential Learning Edition (Second High School Edition) Second High School Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/america-the-essential-learningedition-second-high-school-edition-second-high-school-editionebook-pdf-version/

High-Entropy Alloys(Second Edition) B.S. Murty

https://ebookmass.com/product/high-entropy-alloyssecond-editionb-s-murty/

High Performance Computing: Modern Systems and Practices Thomas Sterling

https://ebookmass.com/product/high-performance-computing-modernsystems-and-practices-thomas-sterling/

Deterministic and Stochastic Modeling in Computational Electromagnetics Dragan Poljak

https://ebookmass.com/product/deterministic-and-stochasticmodeling-in-computational-electromagnetics-dragan-poljak/

Must Know High School Chemistry, Second Edition

John T. Moore

https://ebookmass.com/product/must-know-high-school-chemistrysecond-edition-john-t-moore/

Electric Motor Control Sang-Hoon Kim

https://ebookmass.com/product/electric-motor-control-sang-hoonkim/

Electric Motors and Control Systems, Second Edition Frank

D. Petruzella

https://ebookmass.com/product/electric-motors-and-controlsystems-second-edition-frank-d-petruzella/

Dynamics of Coupled Systems in High-Speed Railways: Theory and Practice Weihua Zhang

https://ebookmass.com/product/dynamics-of-coupled-systems-inhigh-speed-railways-theory-and-practice-weihua-zhang/

HighVoltageDirectCurrentTransmission

Converters,SystemsandDCGrids

DraganJovcic

UniversityofAberdeen

Aberdeen,UK

SecondEdition

Thiseditionfirstpublished2019

©2019JohnWiley&SonsLtd

EditionHistory

JohnWiley&Sons(1e,2015)

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedinaretrievalsystem,or transmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,electronic,mechanical,photocopying,recordingorotherwise, exceptaspermittedbylaw.Adviceonhowtoobtainpermissiontoreusematerialfromthistitleisavailable athttp://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

TherightofDraganJovcictobeidentifiedastheauthorofthisworkhasbeenassertedinaccordance withlaw.

RegisteredOffices

JohnWiley&Sons,Inc.,111RiverStreet,Hoboken,NJ07030,USA

JohnWiley&SonsLtd,TheAtrium,SouthernGate,Chichester,WestSussex,PO198SQ,UK

EditorialOffice

TheAtrium,SouthernGate,Chichester,WestSussex,PO198SQ,UK

Fordetailsofourglobaleditorialoffices,customerservices,andmoreinformationaboutWileyproducts visitusatwww.wiley.com.

Wileyalsopublishesitsbooksinavarietyofelectronicformatsandbyprint-on-demand.Somecontentthat appearsinstandardprintversionsofthisbookmaynotbeavailableinotherformats.

LimitofLiability/DisclaimerofWarranty

Inviewofongoingresearch,equipmentmodifications,changesingovernmentalregulations,andthe constantflowofinformationrelatingtotheuseofexperimentalreagents,equipment,anddevices,thereader isurgedtoreviewandevaluatetheinformationprovidedinthepackageinsertorinstructionsforeach chemical,pieceofequipment,reagent,ordevicefor,amongotherthings,anychangesintheinstructionsor indicationofusageandforaddedwarningsandprecautions.Whilethepublisherandauthorshaveused theirbesteffortsinpreparingthiswork,theymakenorepresentationsorwarrantieswithrespecttothe accuracyorcompletenessofthecontentsofthisworkandspecificallydisclaimallwarranties,including withoutlimitationanyimpliedwarrantiesofmerchantabilityorfitnessforaparticularpurpose.Nowarranty maybecreatedorextendedbysalesrepresentatives,writtensalesmaterialsorpromotionalstatementsfor thiswork.Thefactthatanorganization,website,orproductisreferredtointhisworkasacitationand/or potentialsourceoffurtherinformationdoesnotmeanthatthepublisherandauthorsendorsethe informationorservicestheorganization,website,orproductmayprovideorrecommendationsitmaymake. Thisworkissoldwiththeunderstandingthatthepublisherisnotengagedinrenderingprofessionalservices. Theadviceandstrategiescontainedhereinmaynotbesuitableforyoursituation.Youshouldconsultwitha specialistwhereappropriate.Further,readersshouldbeawarethatwebsiteslistedinthisworkmayhave changedordisappearedbetweenwhenthisworkwaswrittenandwhenitisread.Neitherthepublishernor authorsshallbeliableforanylossofprofitoranyothercommercialdamages,includingbutnotlimitedto special,incidental,consequential,orotherdamages.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationDataAppliedfor

ISBN:9781119566540

CoverDesign:Wiley

CoverImage:CoverpagephotographreproducedwithpermissionofSIEMENS–HVDCProjectBrazil

Setin10/12ptWarnockProbySPiGlobal,Chennai,India 10987654321

Contents

Preface xvii

PartIHVDCwithCurrentSourceConverters 1

1IntroductiontoLineCommutatedHVDC 3

1.1HVDCApplications 3

1.2LineCommutatedHVDCComponents 4

1.3DCCablesandOverheadLines 7

1.3.1Introduction 7

1.3.2Mass-impregnatedCables 7

1.3.3Low-pressureOil-filledCables 7

1.3.4ExtrudedCross-linkedPolyethyleneCables 8

1.4LCCHVDCTopologies 8

1.5LossesinLCCHVDCSystems 10

1.6ConversionofACLinestoDC 10

1.7UltraHighVoltageHVDC 12

2Thyristors 13

2.1OperatingCharacteristics 13

2.2SwitchingCharacteristics 14

2.3LossesinHVDCThyristors 18

2.4ValveStructureandThyristorSnubbers 20

2.5ThyristorRatingSelectionandOverloadCapability 22

3Six-pulseDiodeandThyristorConverter 25

3.1Three-phaseUncontrolledBridge 25

3.2Three-phaseThyristorRectifier 27

3.3AnalysisofCommutationOverlapinaThyristorConverter 28

3.4ActiveandReactivePowerinaThree-phaseThyristorConverter 32

3.5InverterOperation 33

4HVDCRectifierStationModelling,ControlandSynchronisationwith ACSystem 37

4.1HVDCRectifierController 37

4.2Phase-lockedLoop 38

4.3Master-levelHVDCControl 40

5HVDCInverterStationModellingandControl 43

5.1InverterController 43

5.1.1ControlStructure 43

5.1.2ExtinctionAngleControl 43

5.1.3DCVoltageControl 44

5.1.4DCCurrentControlatInverter 45

5.2CommutationFailure 45

6HVDCSystem V–I DiagramsandOperatingModes 49

6.1HVDCEquivalentCircuit 49

6.2HVDC V –I OperatingDiagram 49

6.3HVDCPowerReversal 51

7HVDCAnalyticalModellingandStability 57

7.1IntroductiontoConverterandHVDCModelling 57

7.1.1DetailedSwitchingTransientsModelling 57

7.1.2ModellingwithSwitchings 57

7.1.3AnalyticalDynamicModellingofConverters 58

7.1.4PhasorModelling 58

7.2HVDCAnalyticalModel 58

7.3CIGREHVDCBenchmarkModel 60

7.4ConverterModelling,Linearisation,andGainScheduling 60

7.5ACSystemModellingforHVDCStabilityStudies 64

7.6LCCConverterTransformerModel 67

7.7DCSystemIncludingDCCable 68

7.7.1DCCable/LineModellingasaSingle �� Section 68

7.7.2ControllerModel 69

7.7.3CompleteDCSystemModel 69

7.8AccurateDCCableModelling 70

7.8.1WidebandCableModel 70

7.8.2CableHigher-orderAnalyticalModelinStateSpace 72

7.9HVDC–HVACSystemModel 76

7.10AnalyticalDynamicModelVerification 77

7.11BasicHVDCDynamicAnalysis 77

7.11.1EigenvalueAnalysis 77

7.11.2EigenvalueSensitivityStudy 77

7.11.3InfluenceofPLLGains 79

7.12HVDCSecondHarmonicInstability 80

7.13100HzOscillationsontheDCSide 82

8HVDCPhasorModellingandInteractionswithACSystem 83

8.1ConverterandDCSystemPhasorModel 83

8.2PhasorACSystemModelandInteractionwithDCSystem 84

8.3InverterACVoltageandPowerProfileasDCCurrentisIncreasing 86

8.4InfluenceofConverterExtinctionAngle 88

8.5InfluenceofShuntReactivePowerCompensation 88

8.6InfluenceofLoadattheConverterTerminals 88

8.7InfluenceofOperatingMode(DCVoltageControlMode) 88

8.8RectifierOperatingMode 90

9HVDCOperationwithWeakACSystems 95

9.1Introduction 95

9.2ShortCircuitRatioandEquivalentShortCircuitRatio 95

9.2.1DefinitionofSCRandESCR 95

9.2.2OperatingDifficultieswithLowSCRSystems 98

9.3BackgroundonPowerTransferBetweenTwoACSystems 99

9.4PhasorStudyofConverterInteractionswithWeakACSystems 101

9.5SystemDynamics(SmallSignalStability)withLowSCR 101

9.6ControlandMainCircuitSolutionsforWeakACGrids 102

9.7LCCHVDCwithSVC 103

9.8CapacitorCommutatedConvertersforHVDC 104

9.9ACSystemwithLowInertia 106

10FaultManagementandHVDCSystemProtection 111

10.1Introduction 111

10.2DCLineFaults 111

10.3ACSystemFaults 113

10.3.1RectifierACFaults 113

10.3.2InverterACFaults 114

10.4InternalFaults 115

10.5SystemReconfigurationforPermanentFaults 116

10.6OvervoltageProtection 119

11LCCHVDCSystemHarmonics 121

11.1HarmonicPerformanceCriteria 121

11.2HarmonicLimits 122

11.3ThyristorConverterHarmonics 123

11.4HarmonicFilters 124

11.4.1Introduction 124

11.4.2TunedFilters 126

11.4.3DampedFilters 128

11.5Non-characteristicHarmonicReductionUsingHVDCControls 132

BibliographyPartI:LineCommutatedConverterHVDC 133

PartIIHVDCwithVoltageSourceConverters 137

12VSCHVDCApplicationsandTopologies,PerformanceandCost ComparisonwithLCCHVDC 139

12.1ApplicationofVoltageSourceConvertersinHVDC 139

12.2ComparisonwithLCCHVDC 141

12.3HVDCTechnologyLandscape 142

12.4OverheadandSubsea/UndergroundVSCHVDCTransmission 143

12.5DCCableTypeswithVSCHVDC 147

12.6MonopolarandBipolarVSCHVDCSystems 147

12.7VSCHVDCConverterTopologies 148

12.7.1HVDCwithTwo-levelVoltageSourceConverter 148

12.7.2HVDCwithNeutralPointClampedConverter 150

12.7.3MMCVSCHVDCTransmissionSystems 151

12.7.4MMCHVDCBasedonFBTopology 153

12.8VSCHVDCStationComponents 155

12.8.1ACCB 155

12.8.2VSCConverterTransformer 155

12.8.3VSCConverterACHarmonicFilters 156

12.8.4DCCapacitors 156

12.8.5DCFilter 157

12.8.6Two-levelVSCHVDCValves 158

12.8.7MMCValvesandCells 159

12.9ACInductors 160

12.10DCInductors 161

13IGBTSwitchesandVSCConverterLosses 165

13.1IntroductiontoIGBTandIGCT 165

13.2GeneralVSCConverterSwitchRequirements 166

13.3IGBTTechnology 166

13.3.1IGBTOperatingCharacteristics 167

13.3.2FastRecoveryAnti-parallelDiode 171

13.4HighPowerIGBTDevices 171

13.5IEGTTechnology 172

13.6LossesCalculation 173

13.6.1ConductionLossModelling 173

13.6.2SwitchingLossModelling 174

13.7BalancingChallengesinTwo-levelIGBTValves 178

13.8SnubbersCircuits 179

14Single-phaseandThree-phaseTwo-levelVSCConverters 181

14.1Introduction 181

14.2Single-phaseVSC 181

14.3Three-phaseVSC 184

14.4Square-wave,Six-pulseOperation 185

14.4.1180∘ Conduction 185

14.4.2120∘ Conduction 188

15Two-levelPWMVSCConverters 193

15.1Introduction 193

15.2PWMModulation 193

15.2.1MultipulsewithConstantPulseWidth 193

15.2.2ModulatingSignal 194

15.3SinusoidalPulseWidthModulation 195

15.4ThirdHarmonicInjection 197

15.5SelectiveHarmonicEliminationModulation 198

15.6ConverterLossesforTwo-levelSPWMVSC 198

15.7HarmonicswithPWM 201

15.8ComparisonofPWMModulationTechniques 203

16MultilevelVSCConvertersinHVDCApplications 205

16.1Introduction 205

16.2ModulationTechniquesforMultilevelConverters 207

16.3NeutralPointClampedMultilevelConverter 208

16.4HalfBridgeMMC 210

16.4.1OperatingPrinciplesofHalf-bridgeMMC 210

16.4.2CapacitorVoltageBalancing 212

16.4.3MMCCellCapacitance 214

16.4.4MMCArmInductance 215

16.4.5MMCwithFundamentalFrequencyModulation 218

16.4.6MMCwithPWMModulation 218

16.5FullBridgeMMC 222

16.5.1OperatingPrinciples 222

16.6ComparisonofMultilevelTopologies 224

17Two-levelVSCHVDCModelling,Control,andDynamics 227

17.1PWMTwo-levelConverterAverageModel 227

17.1.1ConverterModelinanABCFrame 227

17.1.2ConverterModelintheABCFrameIncludingBlockedState 229

17.2Two-levelPWMConverterModelinDQFrame 230

17.3VSCConverterTransformerModel 231

17.4Two-levelVSCConverterandACGridModelintheABCFrame 231

17.5Two-levelVSCConverterandACGridModelinaDQRotatingCoordinate Frame 232

17.6VSCConverterControlPrinciples 233

17.7TheInnerCurrentControllerDesign 234

17.7.1ControlStrategy 234

17.7.2DecouplingControl 234

17.7.3CurrentFeedbackControl 235

17.7.4ControllerGains 236

17.8OuterControllerDesign 237

17.8.1ACVoltageControl 237

17.8.2PowerControl 238

17.8.3DCVoltageControl 239

17.8.4ACGridSupport 240

17.9CompleteTwo-levelVSCConverterController 240

17.10SmallSignalLinearisedVSCHVDCModel 242

17.11SmallSignalDynamicStudies 242

17.11.1DynamicsofWeakACSystems 242

17.11.2ImpactofPLLGainsonRobustness 244

18Two-levelVSCHVDCPhasor-domainInteractionwithACSystemsand PQOperatingDiagrams 247

18.1PowerExchangeBetweenTwoACVoltageSources 247

18.2ConverterPhasorModelandPowerExchangewithanACSystem 249

18.3PhasorStudyofVSCConverterInteractionwithACSystem 252

18.3.1TestSystem 252

18.3.2AssumptionsandConverterLimits 252

18.3.3Case1:ConverterVoltagesAreKnown 253

18.3.4Case2:ConverterCurrentsareKnown 254

18.3.5Case3:PCCVoltageisKnown 254

18.4OperatingLimits 254

18.5DesignPointSelection 255

18.6InfluenceofACSystemStrength 258

18.7InfluenceofACSystemImpedanceAngle(X s /Rs ) 258

18.8InfluenceofTransformerReactance 258

18.9InfluenceofConverterControlModes 262

18.10OperationwithVeryWeakACSystems 262

19HalfBridgeMMC:Dimensioning,Modelling,Control,andInteraction withACSystem 269

19.1BasicEquationsandSteady-stateControl 269

19.2Steady-stateDimensioning 272

19.3HalfBridgeMMCNon-linearAverageDynamicModel 275

19.4Non-linearAverageValueModelIncludingBlockedState 276

19.5HBMMCHVDCStart-upandChargingMMCCells 278

19.6HBMMCDynamicDQFrameModelandPhasorModel 279

19.6.1Assumptions 279

19.6.2ZeroSequenceModel 282

19.6.3FundamentalFrequencyModelinDQFrame 282

19.6.4SecondHarmonicModelinthe D2Q2 CoordinateFrame 284

19.7SecondHarmonicofDifferentialCurrent 286

19.8CompleteMMCConverterDQModelinMatrixForm 286

19.9Second-harmonicCirculatingCurrentSuppressionController 287

19.10SimplifiedDQFrameModelwithCirculatingCurrentController 290

19.11PhasorModelofMMCwithCirculatingCurrentSuppression Controller 295

19.12SimplifiedDynamicMMCModelUsingEquivalentSeriesCapacitor C MMC 296

19.13FullDynamicAnalyticalHBMMCModel 300

19.14HBMMCControllerandArmVoltageControl 301

19.15MMCTotalSeriesReactanceandComparisonwithTwo-levelVSC 304

19.16MMCInteractionwithACSystemandPQOperatingDiagrams 306

20FullBridgeMMCConverter:Dimensioning,Modelling,and Control 309

20.1FBMMCArmVoltageRange 309

20.2FullBridgeMMCConverterNon-linearAverageModel 309

20.3FBMMCNon-linearAverageModelIncludingBlockedState 310

20.4FullBridgeMMCCellCharging 312

20.5HybridMMCDesign 313

20.5.1OperationUnderLowDCVoltage 313

20.5.2OvermodulationRequirements 314

20.5.3CellVoltageBalancingUnderLowDCVoltage 315

20.5.4OptimalDesignofFullBridgeMMC 315

20.6FullBridgeMMCDCVoltageVariationUsingaDetailedModel 318

20.7FBMMCAnalyticalDynamic DQ Model 320

20.7.1ZeroSequenceModel 320

20.7.2FundamentalFrequencyModel 321

20.8SimplifiedFBMMCModel 321

20.9FBMMCConverterController 322

21MMCConverterUnderUnbalancedConditions 325

21.1Introduction 325

21.2MMCBalancingControllerStructure 326

21.3BalancingBetweenPhases(HorizontalBalancing) 326

21.4BalancingBetweenArms(VerticalBalancing) 328

21.5SimulationofBalancingControls 330

21.6OperationwithUnbalancedACGrid 332

21.6.1DetectingPositiveandNegativeSequenceComponents 332

21.6.2ControllingGridCurrentSequenceComponentswithMMC 336

22VSCHVDCUnderACandDCFaultConditions 339

22.1Introduction 339

22.2FaultsontheACSystem 339

22.3DCFaultswithTwo-levelVSC 340

22.4InfluenceofDCCapacitors 345

22.5VSCConverterModellingUnderDCFaultsandVSCDiodeBridge 345

22.5.1VSCDiodeBridgeAverageModel 345

22.5.2PhasorModelofVSCDiodeBridgeUnderDCFault 348

22.5.3SimpleExpressionforVSCDiodeBridgeSteady-stateFaultCurrent Magnitude 351

22.6VSCConverterModeTransitionsasDCVoltageReduces 352

22.7DCFaultswithHalfBridgeModularMultilevelConverter 354

22.8FullBridgeMMCUnderDCFaults 356

23VSCHVDCApplicationForACGridSupportandOperationwith PassiveACSystems 359

23.1VSCHVDCHighLevelControlsandACGridSupport 359

23.2HVDCEmbeddedInsideanACGrid 360

23.3HVDCConnectingTwoSeparateACGrids 361

23.4HVDCinParallelwithAC 361

23.5OperationwithaPassiveACSystemandBlackStartCapability 362

23.6VSCHVDCOperationwithOffshoreWindFarms 362

23.7VSCHVDCSupplyingPowerOffshoreandDrivingaMW-SizeVariable SpeedMotor 365

BibliographyPartII:VoltageSourceConverterHVDC 366

PartIIIDCTransmissionGrids 371

24IntroductiontoDCGrids 373

24.1DCversusACTransmission 373

24.2Terminology 374

24.3DCGridPlanning,Topology,andPowerTransferSecurity 375

24.4TechnicalChallenges 376

24.5DCGridBuildingbyMultipleManufacturers–Interoperability 376 24.6EconomicAspects 377

25DCGridsWithLineCommutatedConverters 379

25.1MultiterminalLCCHVDC 379

25.2Italy–Corsica–SardiniaMultiterminalHVDCLink 380

25.3ConnectingtheLCCConvertertoaDCGrid 381

25.3.1PowerReversal 381

25.3.2DCFaults 382

25.3.3ACFaults 383

25.4ControlofLCCConvertersinDCGrids 383

25.5ControlofLCCDCGridsThroughDCVoltageDroopFeedback 384

25.6ManagingLCCDCGridFaults 385

25.7ReactivePowerIssues 387

25.8EmployingLCCConverterStationsinEstablishedDCGrids 387

26DCGridswithVoltageSourceConvertersandPowerFlowModel 389

26.1ConnectingaVSCConvertertoaDCGrid 389

26.1.1PowerReversalandControl 389

26.1.2DCFaults 389

26.1.3ACFaults 389

26.2MultiterminalVSCHVDCOperatinginChina 390

26.3DCGridPowerFlowModel 390

26.4DCGridPowerFlowUnderDCFaults 395

27DCGridControl 399

27.1Introduction 399

27.2FastLocalVSCConverterControlinDCGrids 399

27.3DCGridDispatcherwithRemoteCommunication 401

27.4Primary,Secondary,andTertiaryDCGridControl 402

27.5DCVoltageDroopControlforVSCConvertersinDCGrids 403

27.6Three-levelControlforVSCConverterswithDispatcherDroop 405

27.6.1Three-levelControlforVSCConverters 405

27.6.2DispatcherController 406

27.7PowerFlowAlgorithmWhenDCPowersareRegulated 406

27.8PowerFlowandControlStudyofCIGREDCGridTestSystem 411

27.8.1CIGREDCGridTestSystem 411

27.8.2PowerFlowAfterOutageoftheLargestTerminal 413

28DCCircuitBreakers 417

28.1Introduction 417

28.2ChallengeswithDCCircuitOpening 417

28.2.1DCCurrentCommutation 417

28.2.2DCCurrentSuppressionandDissipationofEnergy 418

28.3DCCBOperatingPrinciplesandaSimpleModel 418

28.4DCCBPerformanceRequirements 420

28.4.1OpeningSpeed 420

28.4.2DCCBRatingsandSeriesInductors 420

28.4.3BidirectionalCurrentInterruption 421

28.4.4MultipleOpen/closeOperationsinaShortTime 421

28.4.5Losses,Size,andWeight 421

28.4.6Standardisation 421

28.5PracticalHVDCCBs 422

28.6MechanicalDCCB 422

28.6.1OperatingPrinciplesandConstruction 422

28.6.2MathematicalModelandDesignPrinciples 424

28.6.3TestCircuitforDCCBSimulation 426

28.6.4SimulationofDCFaultClearing 427

28.6.5NegativeFaultCurrentInterruption 427

28.6.6MultipleOpen/closeOperationsinaShortTime 428

28.6.7MechanicalDCCBforHighVoltages 429

28.7Semiconductor-basedDCCB 430

28.7.1TopologyandDesign 430

28.7.2Self-protectionofSemiconductorValves 432

28.7.3SimulationofFaultCurrentInterruption 432

28.8HybridDCCB 434

28.8.1TopologyandDesign 434

28.8.2HybridDCCBforHighVoltages 435

28.8.3SimulationofFaultCurrentInterruption 436

28.8.4BidirectionalOperation 437

28.8.5FaultCurrentLimiting 438

29DCGridFaultManagementandProtectionSystem 441

29.1Introduction 441

29.2FaultCurrentComponentsinDCGrids 442

29.3DCSystemProtectionCoordinationwithACSystemProtection 444

29.4DCGridProtectionSystemDevelopment 445

29.5DCGridProtectionSystemBasedonLocalMeasurements 446

29.5.1ProtectionBasedonDCCurrentandCurrentDifferential 446

29.5.2RateofChangeofVoltageProtection 447

29.6BlockingMMCConvertersUnderDCFaults 450

29.7DifferentialDCGridProtectionStrategy 452

29.8SelectiveProtectionforStar-topologyDCGrids 455

29.9DCGridswithDCFault-tolerantVSCConverters 456

29.9.1GridTopologyandStrategy 456

29.9.2VSCConverterwithIncreasedACCouplingReactors 457

29.9.3LCLVSCConverter 459

29.9.4VSCConverterwithFaultCurrentLimiter 461

29.10DCGridswithFullBridgeMMCConverters 461

30HighPowerDC/DCConvertersandDCPowerFlowControlling Devices 465

30.1Introduction 465

30.2PowerFlowControlUsingSeriesResistors 466

30.3Low-stepping-ratioDC/DCConverters(DCChoppers) 469

30.3.1ConverterTopology 469

30.3.2ConverterController 470

30.3.3DC/DCChopperAverageValueModel 471

30.3.4H-BridgeDC/DCChopper 473

30.4Non-isolatedMMC-basedDC/DCConverter(M2DC) 473

30.4.1Introduction 473

30.4.2ModellingandDesign 474

30.4.3DesignExampleandComparisonwithMMCAC/DC 477

30.4.4ControllerDesign 479

30.4.5SimulationResponses 480

30.5DC/DCConverterswithDCPolarityReversal 484

30.6High-stepping-ratioIsolatedDC/DCConverter(DualActiveBridge DC/DC) 484

30.6.1Introduction 484

30.6.2ModellingandControl 486

30.6.3SimulatedResponses 487

30.7High-stepping-ratioLCLDC/DCConverter 490

30.8BuildingDCGridswithDC/DCConverters 492

30.9DCHubs 495

30.10DevelopingDCGridsUsingDCHubs 496

30.11NorthSeaDCGridTopologies 496

BibliographyPartIII:DCTransmissionGrids 500

AppendixAVariableNotations 503

AppendixBAnalyticalBackgroundtoRotatingDQFrame 505

B.1TransformingACVariablestoaDQFrame 505

B.2DerivativeofanOscillatingSignalinaDQFrame 507

B.3TransforminganACSystemDynamicEquationtoaDQFrame 507

B.4Transformingan n-OrderStateSpaceACSystemModeltoaDQFrame 509

B.5Static(Steady-state)ModelinginaRotatingDQCoordinateFrame 510

B.6RepresentingtheProductofOscillatingSignalsinaDQFrame 511

B.7RepresentingPowerinDQFrame 512

AppendixCSystemModelingUsingComplexNumbersandPhasors 515

AppendixDSimulinkExamples 517

D.1Chapter3Examples 517

D.2Chapter5Examples 517

D.3Chapter6Examples 519

D.4Chapter8Examples 521

D.5Chapter14Examples 523

D.6Chapter16Examples 524

D.7Chapter17Examples 527

Index 535

Preface

Atthetimeofwritingthisbookthereareover200highvoltagedirectcurrent(HVDC) linksinstalledworldwide.Thelargestinstallationsoperateat ±800kVDCvoltagewhile thehighestDCcurrentratingsareover4500A.Althoughalternatingcurrentwasthe predominantmethodfortransmittingelectricalenergyduringthetwentiethcentury, HVDChasnowbeendemonstratedtobethebestsolutionformanyspecificapplication areasandthenumberofinstallationsperyearisconstantlyincreasingatthebeginningofthetwenty-firstcentury.Despitesignificantconverterstationcosts,HVDCis techno-economicallypreferredinmanygeneralapplications:

• long-distancelarge-scalepowertransfer;

• subseaandlong-distancecablepowertransmission;

• interconnectingasynchronousACsystems,orsystemswithdifferentfrequencies;

• controllablepowertransferbetweendifferentnodesinanelectricitymarketormarkets;

• ACgridstabilitysupport,ancillaryserviceprovision,andresiliencefromblackouts;

• connectingisolatedsystemslikeoffshorewindfarmsoroilplatforms.

DCtransmissiontechnologywasusedinmanyinstancesintheveryearlypower systems,butthemodernHVDCtransmissionbeganwiththe1954Sweden–Gotland installation.Thissystem,andalloftheotherHVDCscommissioneduntilthemid 1970s,wasbasedonmercuryarcvalves.Significanttechnicaladvancecamewith theintroductionofsolid-statevalves(thyristors)althoughtheyonlysupporttheline commutatedconverterconcept.Inthefirstdecadeofthetwenty-firstcenturythere hasbeenveryrapiddevelopmentoffundamentallynewtechnologiesandincreasing demandforHVDCtechnology.Theintroductionofvoltagesourceconverters(VSCs) requiresnewvalvesthatutiliseinsulatedgatebipolartransistorsandalsonewprotectionandcontrolapproaches.Themodularmultilevelconvertershaveeventually emergedasthemostcost-effectiveVSCconverterconceptwhichpracticallyeliminates filteringneedswithHVDCandremovesvoltagelimitswithVSCvalves.Modular multilevelconverterHVDCnowadayshaslowlosseswhicharecomparablewiththose ofthyristorHVDCandnewtechnologiesareemergingthatopenuppossibilitiesfor widerapplicationareas.

Intheseconddecadeofthetwenty-firstcentury,ithasbecomeapparentthatDC transmissiongridsarebothaviablesolutiontolarge-scaleenergychallengesandtechnicallyfeasible.Theprimaryapplicationdriversarecomingfromtheinitiativeslike theNorthSeaDCgrid,Medtech,Desertec,EuropeanOverlaySupergridandvarious

projectsinChina,wheretwomultiterminalVSCHVDCsystemsarealreadyoperating. ItisacceptedthattheDCtransmissiongridswillhavesimilarorbetterlevelsofreliability andtechnicalperformancetotheACtransmissionsystem.Thislevelofperformance, securityandreliabilityistechnicallyfeasible,althoughinmanyaspectsDCgridswill besubstantiallydifferentfromtraditionalACsystems.ThedevelopmentofDCgrids bringssignificanttechnicaladvancesinHVDCtechnologies,inparticularrelatedtoDC CB(circuitbreakers),DC/DCconvertersandDCprotectionsystems,andsubstantial furtherresearchanddevelopmentisanticipated.

NowadaysHVDCandDCgridsareassociatedwithgreenenergy,asfacilitatorsof large-scalerenewableenergyplants.Thishelpswiththepublicacceptanceandimage, andfacilitatesfurtherinvestmentsinlargepublicprojects.AlsoHVDCisperceived asatechnologythatavoidspylons,byusinglongundergroundcables,whichfurther strengthensargumentsforfuturefundingdecisions.

Thetimingofthisbookis,therefore,instepwithacceleratedinterestinHVDCand projectedsignificantincreaseandexpansioninapplications.Thebookisorganised intothreepartsinordertostudyallthreemajorHVDCconceptsandcurrentresearch developments:linecommutatedHVDC,VSCHVDCandDCgridsincludingcurrent researchdevelopments.Eachpartwillreviewtheoreticalconceptsfirstandanalyse aspectsoftechnology,interactionwithACgrids,modelling,control,faultsandprotectionwithparticularemphasisonpracticalimplementationaspectsandreported operationalissues.Thetechnologydescribedinthefirsttwopartsislargelybasedon theoperatingHVDCsystems,whilethetopicofDCgridsisgroundedinthesignificant volumeofresearchatmanyinstitutions.

ThetechnicalfieldofHVDCtransmissionandDCgridsstraddlesthreemajortraditionalelectricalengineeringdisciplines:

Powertransmissionengineering –theimpactofHVDCsystemsontheconnectingAC transmissionsystemsandthenationalgridsisofprimaryimportance.Theinfluence ofACsystemsonHVDCisalsoofsignificanceintermsoftechnicalperformance, stability,protectionandpowertransfersecurityingeneral.Theharmonicinteraction willbestudiedinsomedepth.

Powerelectronics –eachHVDClinkinvolvesatleasttwoAC/DCconverterswhileDC gridswillhavemanymoreincludingsemiconductorDCCBsandDC/DCconverters. Theseconvertershavesimilarfeaturestothetraditionallow-powerconvertersbut manyotheruniquerequirementsexisttodevelopvalvesandconverterassemblies capableofsustainingupto800kVandperhapsover4500A.Theprotectionofvalves andconvertersisveryimportantanddefiningpowerelectronicsfeatureinHVDC.

Controlengineering –modellingandsimulationofHVDCisessentialfordesign andoperationandseveraldifferentmodellingapproachesexistdependingonthe modelapplication.Inparticular,becauseofhighcostsofHVDCtestingandthe consequencesofanydesignissues,modelaccuracyandsimulationspeedplaya crucialroleinthesystemdesign.ThecontrolsystemsforHVDChaveevolvedinto verycomplextechnologieswhicharealwaysmultivariableandnon-linearwith multiplecontrollayers.

Theabovethreetechnicaldisciplineswillbeemployedinthisbookinordertoanalyse alloftheessentialtechnicalaspectsofHVDCandDCgrids,aimingtofacilitatelearning byresearchersandengineersinterestedinthisfield.

ThematerialinthisbookincludescontributionsfrommanyHVDCresearchersand engineers,anditisdevelopedfromresearchprojectsfundedbyseveralresearchcouncils andprivatefirms.Moreimportantly,thestudiesareinspiredandbuiltonpreviouswork bynumerousHVDCengineersandresearchers.

TheauthorwouldliketoexpressgratitudetoDrKhaledAhmedforsignificationcontributiontothefirsteditionofthismanuscript,whichhasservedasthebasisforthe secondedition.TheauthorisparticularlythankfultoALSTOMGrid,UK,formaking theircomprehensivereport‘HVDCConnectingtothefuture’availabletotheauthors, aswellastoSiemens,Germany,andABB,Sweden,fortheirHVDCphotographs.Iam alsoindebtedtoalloftheresearchersattheUniversityofAberdeenHVDCresearch centreandinparticulartoDr.WeixingLin,Dr.AliJamshidifar,Dr.MasoodHajian,Dr. HuibinZhang,Mr.StefanKovacevic,andDr.LuZhangfortheircontributions.

SpecialthanksarereservedforSSE,Scotland,and,inparticular,toAndrewRobertson, fortheirsupportoftheHVDCcourseattheUniversityofAberdeen,whichprovided substantialmaterialforthisbook.

Theauthorisfurthergratefultothefollowingorganisations,whichhavesupported relatedresearchstudiesattheUniversityofAberdeen:

• EPSRC(EngineeringandPhysicalSciencesResearchCouncil)UK;

• ERC(EuropeanResearchCouncil),FP7Ideasprogram;

• RTE(RéseaudeTransportd’Électricité),France;

• EUHorizon2020.

January2019

DraganJovcic

HVDCwithCurrentSourceConverters

1.1HVDCApplications

Thyristor-basedhighvoltagedirectcurrent(HVDC)transmissionhasfoundapplication inmorethan150point-to-pointworldwideinstallations,andineachcasehasprovento betechnologicallyand/oreconomicallysuperiortoalternatingcurrent(AC)transmission.TypicalHVDCapplicationscanbegroupedasfollows:

• Submarinepowertransmission.ACcableshavelargecapacitanceandforcablesover 40–70kmthereactivepowercirculationbecomesunacceptable.Thisdistancecanbe extendedsomewhatwithreactivepowercompensation.ForlargerdistancesHVDCis moreeconomical.Agoodexampleisthe580km,700MW, ±450kVNorNedHVDC betweenNorwayandTheNetherlands.

• Long-distanceoverheadlines.LongAClinesrequirevariablereactivepowercompensation.Typically600–800kmisbreakevendistance,andforlongerdistancesHVDC ismoreeconomical.Agoodexampleisthe1360km,3.1GW, ±500kVPacificDC intertiealongthewestcostoftheUSA.

• InterconnectingtwoACnetworksofdifferentfrequencies.Agoodexampleisthe 500MW, ±79kVback-to-backMeloHVDCbetweenUruguayandBrazil.The Uruguaysystemoperatesat50HzwhereastheBrazilnationalgridrunsat60Hz.

• InterconnectingtwounsynchronisedACgrids.IfthephasedifferencebetweentwoAC systemsislargetheycannotbedirectlyconnected.Atypicalexampleisthe150MW, ±42kVMcNeillback-to-backHVDClinkbetweenAlbertaandSaskatchewaninterconnectingasynchronouseasternandwesternAmericansystems.

• ControllablepowerexchangebetweentwoACnetworks(fortrading).TheACpower flowisdeterminedbythelineimpedances,andthereforetheACpowerflowcannot bedirectlycontrolledineachline.IncomplexACnetworksitiscommontoobserve looppowerfloworevenoverloadingorunder-utilisationofsomeAClines.Many HVDCsystemsparticipatedirectlyintradingpowerandonetypicalexampleisthe 200MW, ±57kVHighgateHVDCbetweenQuebecandVermont.

ThereareotherlesscommonapplicationsofLCC(linecommutatedconverter)HVDC technologyandthe300MWLevisDe-IcerHVDCprojectwillbementioned.Here,one standardHVDCconverterstation(converterfromStaticVarCompensator)isusedto provideveryhighDCofupto7920A(feedingessentiallyaDCshortcircuit)toenable heatingofremoteCanadianoverheadlinesinordertopreventicebuild-up.

HighVoltageDirectCurrentTransmission:Converters,SystemsandDCGrids, SecondEdition.DraganJovcic. ©2019JohnWiley&SonsLtd.Published2019byJohnWiley&SonsLtd.

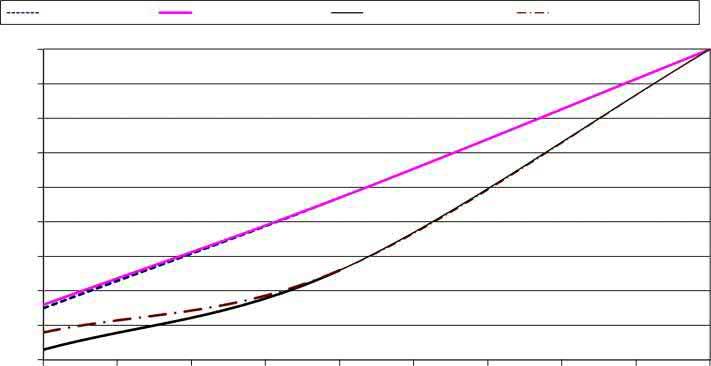

HVDC station costs

HVAC station costs

Beakeven distance

For cables 40–70 km

For overhead lines 600–800 km

Figure1.1 HVDCandHVACtransmissioncostcomparison.

AnimportantargumentforselectingHVDCinsteadofACforanewtransmission lineisalsothecontributiontoshortcircuitlevel.HVDCisabletolimitthefaultcurrent andthereforewillnotrequireupgradeofsubstationequipment.

Figure1.1showsacomparisonofcostsforDCandACtransmissionlines.Inthecase ofHVDCtheinitialcapitalinvestmentismuchhigherbecauseoftheconvertercosts. Asthetransmissiondistanceincreases,thebenefitsofDCcompensateforthecapital investmentandatcertaindistancethetotalcostoftheHVDCsystemissameasthatof theACline.Thebreakevendistanceisintherangeof40–70kmforsubmarinecables andintherangeof600–800kmforoverheadlines.

Figure1.2showsanaerialviewofterminalstationofthe500MWMoyleHVDClink. ThisHVDCenablescontrollablebidirectionalpowerexchangebetweenScotlandand NorthernIreland.

1.2LineCommutatedHVDCComponents

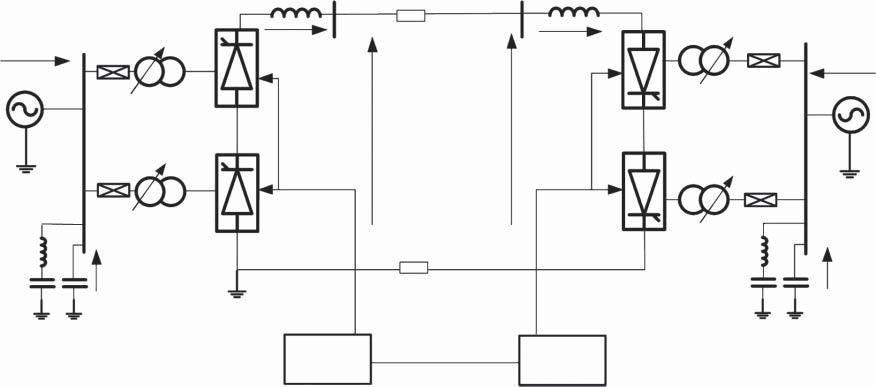

Figure1.3showsatypicallinecommutatedconverterHVDCschematicinterconnectingACsystems1and2.ItconsistsoftwoterminalsandaDClinebetweenthem.Each terminal(converterstation)includesconverters,transformersfilters,reactivepower equipment,acontrolstationandarangeofothercomponents.TherearetwoDClines inthisfigurewhileonelineisatgroundpotential.

AsshowninFigure1.3,themajorcomponentsofanHVDCsysteminclude:

• Converters.Thesetypicallyincludeatleastonesix-pulsethyristor(Graetz)bridge. Eachbridgeconsistsofsixthyristorvalveswhichinturncontainhundredsof individualthyristors.Withlargesystems,bridgesareconnectedinseriesin12-or 24-pulseconfiguration.These12-pulseconverterscanbeconnectedintopolesor bipoles.

• Convertertransformers.Theseareofaspecialconvertertransformertypethatis somewhatmoreexpensivethantypicalACtransformersofthesamerating.The convertertransformersaredesignedtooperatewithhighharmoniccurrentsandto withstandACandDCvoltagestress.Inmostcasesconvertertransformerswillhave tapchangersthatenableoptimisationofHVDCoperation.

Figure1.2 TerminalstationofMoyleHVDCinterconnector(bipole2 × 250MW, ±250kV,with light-triggeredthyristors,commissionedin2001).Source:ReproducedwithpermissionofSiemens.

• SmoothingreactorsontheDCside.ThetypicalinductanceforlargeHVDCsystemsis 0.1–0.5H,whichisdeterminedconsideringDCfaultresponses,commutationfailure anddynamicstability.Thereactorsareofair-core,naturalair-coolingtypeandcosts aremodest.

• Reactivepowercompensation.Theconverterstypicallyrequirereactivepowerof around60%oftheconverterpowerrating.Alargeportionofthisreactivepoweris suppliedbyfilterbanksandtheremainingpartbycapacitorbanks.Sincereactive powerdemandvarieswithDCpowerlevel,thecapacitorsarearrangedinswitchable banks.

• Filters.Atypical12-pulsethyristorterminalwillrequire11th,13th,23rd,and25th filtersontheACside.Inaddition,ahigh-passfilterisfrequentlyincluded.Insome casesthirdharmonicfiltersarerequired.SomeHVDCsystemswithoverheadlines furtheremployDC-sidefilters.

• Electrodes.SomeoldHVDCsystemsnormallyoperatewithsea/groundreturnbut mostgridoperatorsnolongerallowpermanentgroundcurrentsforenvironmentalreasons.Electrodesdemandongoingmaintenancecosts.Manynewbipolar systemsareallowedtooperatewithgroundreturnathalfpowerforashorttime (10–20minutes)incaseoflossofanHVDCpole.Thisimpliesthatelectrodesare designedforfullcurrent,butcarrynocurrentinnormaloperation.

• Controlandcommunicationsystem.Eachterminalwillhaveacontrolsystemconsistingofseveralhierarchicallayers.Adedicatedcommunicationlinkbetweenterminals isneededbutspeedisnotcritical.AnHVDClinkcanoperateincaseofalossof communicationlink.

Figure1.3 TypicalHVDCschematic(12-pulsemonopolewithmetallicreturn).

1.3DCCablesandOverheadLines

1.3.1Introduction

LCCHVDChasbeenimplementedusingbothoverheadlinesandunderground/subsea DCcables.Overheadlinesarevulnerabletolightningstrikes,whichareessentiallyDC faults.NeverthelessDCfaultsonlycausetransientdisturbancesandtheyarereadily managedbyLCCHVDC.Contrarytovoltagesourceconverter(VSC)HVDC,aswillbe discussedlater,DCfaultscausemuchmoreseriousdisturbances.

Themostcommoncabletechnologiesthathavebeendevelopedsofarinclude:

• mass-impregnatedcables(MI);

• low-pressureoil-filledcables;and

• extrudedcross-linkedpolyethylene(XLPE)cables.

Theabovecabletypeshavesameconductorsandtheirconstructionissimilarbut theinsulationmaterialsaresubstantiallydifferent.Thecablevoltageratingdependson thecapabilityoftheinsulation(dielectric)material,andtherearetwomaintypesof dielectrics,namelylappedandextruded.

1.3.2Mass-impregnatedCables

Since1895,MIcableshavebeenusedinpowertransmission.InMIcables,thedielectricislappedpaperinsulation,whichisimpregnatedwithhigh-viscosityfluid.Forbulk powertransmission,MIcablesarestillthemostsuitablesolutionbecauseoftheircapacitytoworkupto500kVDC.AlsothesecablestoleratefastDCvoltagepolarityreversal, makingthemsuitableforLCCHVDC.TheMIcableshavealongrecordoffieldoperationatavoltageof500kVandtransmissioncapacityofover800MW(1.6kA)for monopoleHVDC,but600kVand1000MWratingshavebeenannounced.Therefore anHVDCinbipolarconnectionisabletotransmitupto2000MWwithMIcables. Thesecablescanbeinstalledatdepthsofupto1000mbelowsealevelandwithnearly unlimitedtransmissionlength.Thecapacityofthissystemislimitedbytheconductortemperature,whichcanreduceoverloadcapabilities.The580km-long,700MW, 450kVcablelinkbetweenNorwayandTheNetherlandsrepresentsthehighestpower andlongestlengthforthiscabletype.Atpresentmost(over90%)submarinecablesare oftheMItype.

1.3.3Low-pressureOil-filledCables

Low-pressureoil-filledcablesaresimilarinconstructiontoMIcablesbutareinsulated withpaperimpregnatedwithlow-viscosityoilunderanoverpressureoffewbars.The availabletechnologytodayensuresvoltagesupto500kVandpowersupto2800MW forundergroundinstallation.ItcanbeusedforbothACandDCtransmissionapplications.Sinceoilflowisrequiredalongthecable,thecablelengthislimitedtoaround 80km.Additionally,theriskofoilleakagemustbetakenintoaccountforenvironmental reasons.

Table1.1 DCcablestypesforundergroundandsubmarineapplications.

TypeMass-impregnatedOil-filledXLPE ConductorCu/AlCu/AlCu/Al InsulationPaperandmassPaperandfluidCross-linkedPE Voltage600kV500kV320kV(525kVisavailable) Capacitypercable1000MW2800MW1000MW ConvertertypeLCCorVSCLCCorVSCVSCorunidirectionalLCC DistanceUnlimitedLimitedbecauseofoilUnlimited

1.3.4ExtrudedCross-linkedPolyethyleneCables

Extrudedcross-linkedpolyethylenecablescannotwithstandrapidpolarityreversaland theyarenotnormallyusedwithLCCHVDC(unlessitisaunidirectionalsystem).They willbediscussedfurtherwithVSCHVDC.

Theabovethreetypesofcablesareusedforbothundergroundandsubmarine cablesandtheirbasicpropertiesareshowninTable1.1.Thedifferencebetweenthe undergroundandsubmarinecablesliesintheconductormaterialandthearmourlayer. Armourstrengtheningisusedinsubmarinecablestowithstandtheaxialmechanical tensionduringlayingandoperation.

Cableswithcopperconductorsareusedforsubmarineapplicationswhilealuminium conductorsaregenerallypreferredforunderground.Copperhashighelectricalconductivityandgoodmechanicalproperties.Also,itcanbeusedtoimplementstrongjoints. Howeveritisheavyandmoreexpensivethanaluminium,andforthesereasonsitisused whenitsmechanicalpropertiesaremandatory,suchasinsubmarinecables.Aluminium haslowconductivityandpoorermechanicalproperties.Splicingismoredifficult.Itis lighterandlessexpensivecomparedwithcopper.

1.4LCCHVDCTopologies

HVDCsystemsaredividedintotransmissionsystemsandback-to-backHVDC.HVDC transmissioncanbebipolarormonopolar.AmonopolarHVDCistypicallyusedfor smallersystemsandthetopologyisshowninFigure1.4.TypicallypositiveDCvoltage isadoptedbecauseitcarriesfewercoronaissues.Thereturncurrentcanrunthroughthe groundoradedicatedcablecanbeemployed.Ifareturncableisused(metallicreturn), itwillbeatgroundpotentialwithlowinsulationlevel(typicallyaround10kV)andcosts arethereforelowerthanforapositive-poleDCcable.A12-pulsetopologyisshownwith twosix-pulseconvertersinseries.

Figure1.5showsabipolarHVDC.BipolarHVDChastwoindependentpolesandit canoperateathalf-powerifoneDCcableorpoleisoutofservice.Normallythepolesare balancedandthereisnogroundcurrent,butgroundreturnisusedifonepoleisoutof service.Inmoderngridcodes,groundcurrentisnotallowedbecauseofenvironmental concerns.Insomenationalstandardsgroundcurrentsareallowedonlyforshortperiods

AC system 1

3 phase V1g, f1

Terminal 1Terminal 2

AC system 2 3 phase V2g, f2 P1g, Q1g P2g, Q2g Y

Figure1.4 Twelve-pulsemonopolarHVDCwithgroundreturn.

Terminal 1Terminal 2

Positive pole

AC system 1

3 phase V1g, f1

Positive pole

AC system 2 3 phase V2g, f2 P1g, Q1g P2g, Q2g

Figure1.5 BipolarHVDC(12-pulse)withgroundreturn.

oftimeinemergencysituations(e.g.secondaryreservestart-upfor10–20minutes). InsteadofgroundreturnathirdcableorDCcablefromthefaultedpolecanbeused occasionally.

Figure1.6showsaback-to-backHVDC,whichisfrequentlymonopolar.InthistopologybothconverterterminalsarelocatedinasinglestationandDCcablesarevery short.Themainpurposeofback-to-backHVDCistoprovidecontrollablepowertransferbetweentwoasynchronousACsystemsorACsystemswithdifferentfrequencies. SinceDCcablesareveryshortandthereforetransmissionlossesarelow,back-to-back HVDCisdesignedatlowvoltage(withashighacurrentaspossible)inordertoreduce costs(costsareproportionaltoinsulationlevel).Thesmoothingreactorsareverysmall ornotrequired,sincethereislowprobabilityofDClinefaults.Back-to-backHVDC allowsforoperationwithvariableDCvoltage,andthisfacilitatessomelimitedreactive powercontrolcapability.

Figure1.6 Back-to-backHVDCtopology.

Auxiliaries

Converter valves

AC harmonic filters

Valve cooling plant

DC smoothing reactors

HF filter

Converter transformer

Figure1.7 BreakdownoftypicalLCCHVDCstationlossesat1p.u.power.

1.5LossesinLCCHVDCSystems

ThelossesinHVDCsystemswillincludeconverterstationlossesandDCcablelosses. Figure1.7showsthemaincomponentsoftypicalHVDCstationlosses.ThetotalLCC HVDCstationlosseswilldependonthesizeoftheHVDCstation,thevoltageleveland theconfiguration,andtypicallymayamountto0.5–1%ofthepowertransfer.

Atpartialloadingthepercentagelosseswillgenerallyincrease.Figure1.8showsthe loaddependenceofmajorlosscomponents.Asanexample,magnetisingcurrentin convertertransformerswillbeconstantirrespectiveofloadingandat10%loadingthe transformerlossesare20%.

1.6ConversionofACLinestoDC

TherehavebeenmanystudiesworldwideonconvertingexistingAClinesintoDC, mainlyinitiatedbythedesiretoincreaseAClinecapacityortoremovestability

Figure1.8 VariationofHVDCstationlosseswithDCpower,shownrelativeto1p.u.losses.

constraints.Theseissuesusuallyrequirecostlylineupgrades/reconductoring,series compensationorinstallationofadevicefromtheFACTS(flexibleACtransmission systems)family.Insuchcase,conversiontoHVDCcanusuallyofferthebiggestcapacity increaseandarangeofotherbenefits.Typicallytowersandconductorswillnotbe changedbutinsulatorsmayneedtobeupgradedtooperatewithDClines.

ThemainadvantagesofconvertingexistingAClinetoHVDCare:

• anincreaseincapacity;

• fewercoronaissues,andgenerallyhigheroperatingvoltages;

• bettercontrolofactiveandreactivepower,andothersystem-levelbenefits;

• betterstabilitylimitsandactivestabilisationofthegrid;and

• lowertransmissionlosses.

SomeofthedisadvantagesofconversiontoHVDCinclude:

• morepollutionbeingattractedtoinsulatorsenergisedwithDC–insulatorupgrade isrecommended;and

• converterstationcosts.

Figure1.9showssomecommonoptionsforconvertingasingle-circuitthree-phase ACtransmissionintoDC:

1.ThefirstoptionemploysallthreeconductorsforasingleDCpolewhilegroundis usedforreturn.Thismethodwillsignificantlyincreasecurrentcarryingcapacitybut groundreturnwillnotbeallowedinmanymodernsystems.

2.ThesecondoptionsadoptsaDCbipolewithmetallicreturn.Theneutralconductor canbeusedformonopolaroperation.

3.Thethirdoptionisbasedonatri-poleHVDCconcept.Thismethodusesthethird conductoralternativelyasapositiveandnegativepole,whichexploitsthelongthermalconstantsofconductors.Acapacityincreaseofaround37%isachieved(over

Figure1.9 Optionsforconversionofthree-phase AClinesintoDC.

DC monopole with ground return

DC bipole with metalic return

DC tripole with metalic return

bipoleconfiguration)usinglinesandtheRMSvaluesofcurrentintheconductors (over10minutes)areequaltotheconductorrating.Anadditionalbidirectionalconverterisrequired.

1.7UltraHighVoltageHVDC

ThestandardDCvoltageforHVDCis500kVandtheItaipu3150MW, ±600kVHVDC hasusedthehighestDCvoltageforalongperiod.Howeverwithemergingrequirements forbulkpowertransmissionof5–10GWoverlongdistancesinAsia,AfricaandSouth Americainthelate1990sresultedintheprogressivedevelopmentofUHVDC(ultra highvoltageDC).

Xiangjiaba–Shanghai6400MW, ±800kVUHVDC,implementedin2010,wasthefirst commercialUHVDC,andfourother ±800kVsystemswereimplementedin2011–2013, whilestudiesareunderwayfor1100kVDCvoltages.TheprogresstowardsUHVDChas demandedmuchresearchanddevelopmenteffort,andthemainchallengesaresummarisedbelow:

• improvementsininsulation,inparticularinpollutedareas;

• transformerdevelopment,includingbushings;

• developmentofultrahighvoltage(UHV)testcentres.

Itisimportanttoappreciatethatalloftheequipment,includingauxiliariesthat connecttoDClines,mustbeupratedtoUHVvoltages.Inpracticethistranslatesto longerunits(bushings,arresters,voltagetransducers,currenttransducers,etc.)with moreseries-connectedbasicelements.Frequently,themainchallengebecomesthe mechanicalstrengthinthefaceofincreasedforcesfromseismicrequirements,wind andotherfactors.

Theuseofnewinsulatingmaterialsandcoronashieldsbecomesstandardtoincrease insulationlevels,althoughthedevelopmentofUHVinsulatorsandbushingsremains challenging.TheUHVvalvedesignisnotconsideredasignificantobstacle.

Thyristors

2.1OperatingCharacteristics

Thethyristorisanessentialcomponentinhighvoltagedirectcurrent(HVDC)valves anditisstilloneofthemostcommondevicesusedinpower-switchingapplicationsin allindustries.Thisisattributedtotheirhighpowerratingsandhighefficiency.Single deviceshaveupto8500V,4500Acapability,theyarebuiltonsinglewafersofupto 150mmdiameter,andhavebeeninexistenceforover60years.

Thethyristorisafour-layer,three-terminaldevice,asshowninFigure2.1.Thethree connectionsareA-anode,K-cathodeandG-gate.Whengatecurrentisapplied,thelayer betweenJ2andJ3becomesN(negative)andthethyristorbecomesaPNdevicesimilar toadiode,alsoshowninFigure2.1.Functionally,itissimilartoadiodebutthestartof conductioncanbedelayedusingthegatecircuit.

Athyristorcanbeconsideredasacontrollablediode,asshownintheoperatingcurves inFigure2.2.Withnogatecurrent, ig = 0,itbehaveslikeanopencircuit(OFFstate)in bothforwardandreversedirections.Aforwardvoltageacrossthedevice(Apositive w.r.t.K)resultsinjunctionsJ1andJ3beingforwardbiased,whereasJ2isreversebiased, andthereforeonlyasmallleakagecurrentflows.If V AK isincreasedtoacriticallimit, thedevicesuddenlyswitchestoaconductingstateastheresultofthebreakdownor breakoverofJ2.Ifagatecurrent ig isappliedthenthemagnitudeof V AK neededfor breakoverisdramaticallyreducedandthedevicebehaveslikeadiode.Thelevelof ig requiredissmallcomparedwiththemainpowercurrent.Thecurrent I l isthelatching current,whichistheanodecurrentrequiredtoensurethatthethyristorswitchesto theONstate.Onceanodecurrentreaches I l thegatecurrentcanberemoved.Thegate currentisthereforeashortpulseof10–50 μs.Theoretically,agatepulseisrequiredonce perhalf-cycle,butinpracticegatepulsesaresentmultipletimesperhalf-cycletoensure firingunderalloperatingconditions.

Oncethedeviceisconducting, ig canbereducedandthedeviceremainsintheON state.Whenthedeviceisinconduction,itsstateisdeterminedsolelybytheanode current.Iftheanodecurrent I A fallsbelowsomecriticalvalue,theholdingcurrent I h (typicallyfewamilliamps),thedeviceswitchesoff,revertingtotheblockingOFFstate. Ifareversevoltageisappliedacrossthedevice(negativeV AK ),J1andJ3become reversebiased,onlyJ2isforwardbiasedandthereforeonlyasmallleakagecurrentflows. Ifnegative V AK isincreasedsufficiently,theneventuallyavalanchebreakdownoccurs acrossJ1andJ3,resultingindamagetothedeviceunlessstepsaretakentolimitthe HighVoltageDirectCurrentTransmission:Converters,SystemsandDCGrids, SecondEdition.DraganJovcic. ©2019JohnWiley&SonsLtd.Published2019byJohnWiley&SonsLtd.