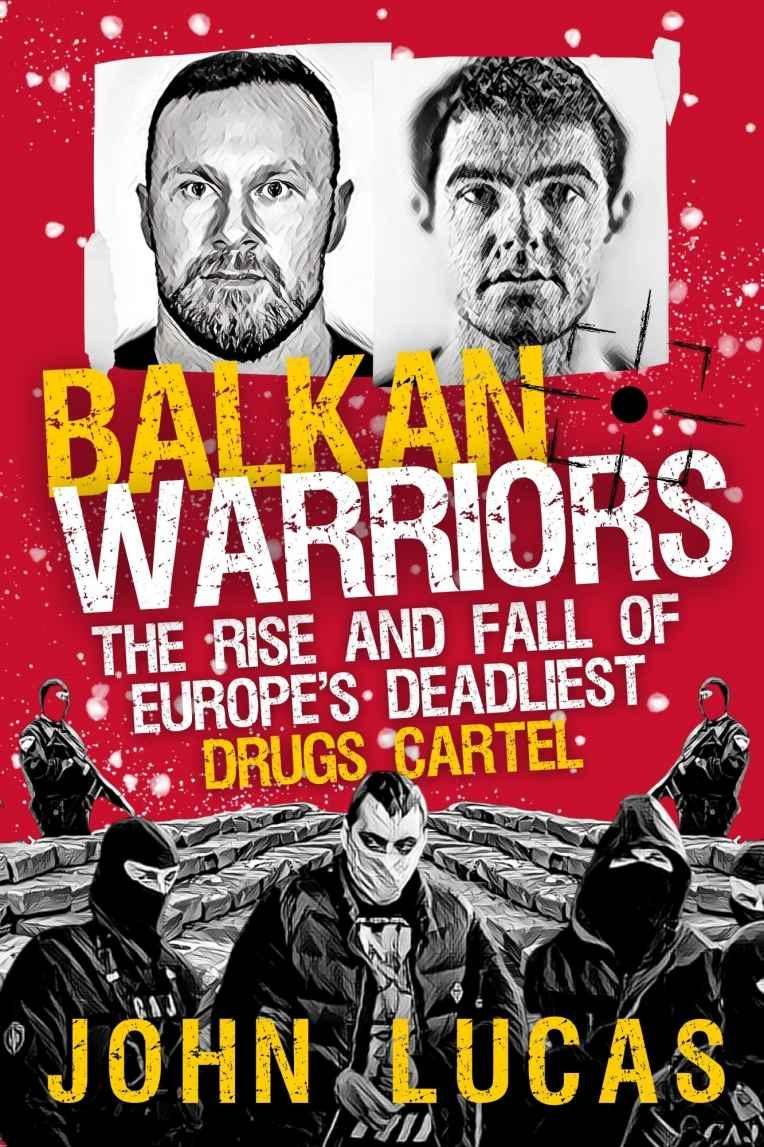

ARKAN

JANUARY 15, 2000: Arkan’s murder was inevitable, so his swift and relatively painless execution was probably a blessing. Relaxed and chatting in the lobby of Belgrade's Intercontinental Hotel, surrounded by friends, admirers, and other hangers-on, he never saw it coming three bullets to the head and he crumpled to the ground. Arkan had been speaking with two associates while his wife waited in the hotel’s restaurant. He was, according to reports, filling out a betting slip, hopeful of cashing in on a sporting event set to take place during the week. Arkan hardly needed the money. During a decades-long career as a criminal and warlord, he had amassed millions. The gunman, a young mob-affiliated cop, had been hanging around in the foyer, apparently unnoticed. After spotting Arkan, he lingered nearby until the perfect opportunity presented itself, then he walked up and let loose a volley of rounds from his CZ99 pistol, which also took out the two men with Arkan, businessman Milenko Mandic, and police inspector Dragan Garic. While the assassin was shot and wounded by one of Arkan’s bodyguards, he survived after surgery.

To this day, the truth behind those few seconds of chaos is still not known, but what is certain is that Zeljko ‘Arkan’ Raznatovic had never been destined for old age. Many who crossed him had gone out in a similarly ruthless fashion, during a career that had seen him graduate from robber to state-sponsored assassin, and then into a paramilitary leader, businessman and outright gangster. Few, if any, European criminals have ever created such a cult of personality, or secured a comparable legendary status in their own lifetimes, as Arkan. And few have left such a legacy. A direct line can be drawn from today’s top mafias from

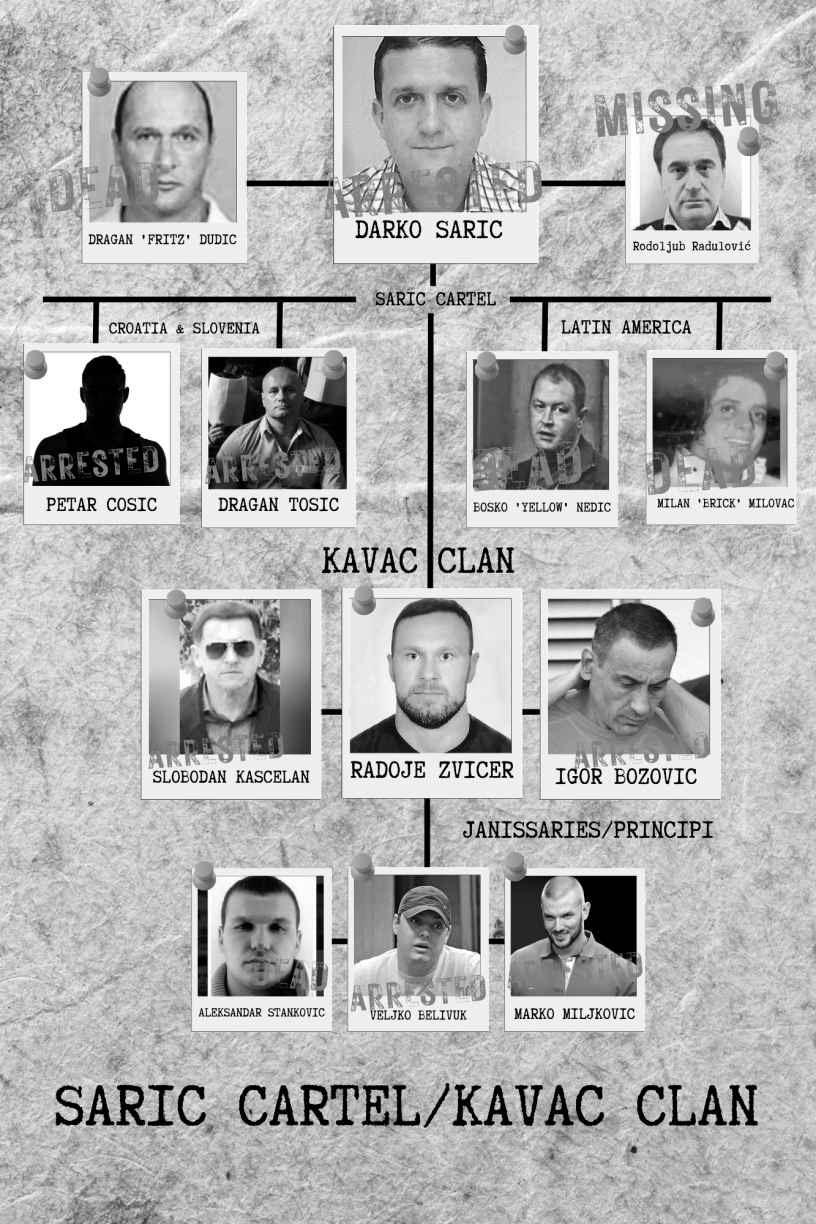

the former Yugoslavia all the way back to Arkan, who not only developed the top-down and highly organised style of the region’s most successful criminal groups, but laid the foundations for the fault lines, and bridges, between the state and elements of the underworld that still exist today. To fully understand the rise and fall of the Saric Cartel and the war between the Kavac and Skaljari Clans, we must go back to the days of Arkan.

Arkan’s assassination rocked Serbia and made global headlines, but the fact that it was carried out with such daring efficiency was no surprise. If Serbian (and Montenegrin) organised crime has a unique characteristic, it is the highly organised and professional nature of its targeted killings. Duplicitous plots, the use of bombs and technology such as drones and GPS trackers, as well as sniper assassinations, are part and parcel of the mob’s MO in this part of the world. This is partly due to the longstanding links between the underworld and the military, police and security services, which still persist today, a generation on from the Balkan wars of the 1990s. And it was Arkan’s almost mythical rise and fall that prepared the groundwork.

Like every country formerly under the Communist yolk, when Yugoslavia’s repressive political system collapsed it gave fresh impetus to criminal enterprise, as well as legitimate commerce. Across the ex-socialist landscape, this manifested itself in different ways. For example, in Yugoslavia’s neighbour Albania the death of dictator Enver Hoxha in 1985, and the subsequent fall of Communism some five years later, precipitated the growth of a series of pyramid schemes, some supported by the new government, which eventually collapsed leaving huge swathes of the country in poverty. Many impoverished young men then gravitated towards organised crime extortion, smuggling, human and drug trafficking. The most successful enterprises sprouted from those working within Albania’s ancient Clan structures, with access to members among the ethnic Albanian diaspora in places like New York and London (see my previous book Albanian Mafia Wars). In Russia, the liberalisation of the underworld was different traditional organised crime groups vied with a new class of corrupt businessmen to divvy up state assets under the gangster ‘democracy’ of Vladimir Putin. The lines between oligarch and mobster became blurred, and still are to this day.

In the former Yugoslavia that is Serbia (and its autonomous regions Kosovo and Vojvodina), Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro and Slovenia the post-Communist kings of the underworld

emerged not necessarily from the crushing poverty of the streets, nor from the heady world of gangster politics, but from somewhere inbetween. Figures from the military and militias, who fought the ethnic conflicts that erupted as the state splintered, formed criminal gangs and absorbed new members from the disaffected youth as time went on. And Arkan set the standard.

Zeljko Raznatovic was born in the small Slovenian border town of Brezice in April 1952. Throughout his short and violent life he would employ more than two dozen aliases, but the one that stuck was Arkan. Where did it come from? One story was that he took the name from a comic strip about a tiger. He supposedly adored the big cats because they combined good looks with an equally devastating ability to kill. Some sources think this explanation fanciful, and that a more prosaic origin is that it was simply one of many fake names he conjured up while robbing banks across Europe. It did appear on a forged Turkish passport, but that’s not to say it had any further relevance. Whatever the case, it became a name that took on a life of its own, striking terror into the hearts of his many enemies.

Although born in Slovenia, Arkan considered himself an ethnic Serb. His father, Veljko, was a colonel in the Yugoslav Air Force and was stationed in barracks in Brezice when Arkan was born. Veljko himself had been born in Montenegro in 1920. He joined the Communist Party and became a partisan during World War Two, participating in the July 13 Uprising in Montenegro against the Italian occupiers. After the war, he became the political commissar of the air force military school, a very senior position. Along with his wife, Slavka, and Arkan’s three sisters Mirjana, Jasna and Biljana, the family moved around to Zagreb, then New Belgrade, and finally to a cramped flat in Old Belgrade, which was still being rebuilt after the near total obliteration it suffered under the Nazis.

The resurrected capital would become a city of angular streets, concrete tower blocks and joyless factories, its people stifled by an equally gray state bureaucracy. The population quadrupled as country peasants arrived seeking work, and to take advantage of state subsidized housing and healthcare. It was a rapid and determined push forward, but life could be dreary, and you had to tow the line. The state, and the nation, was all. In fact, like many Communist countries, it was practically impossible to leave, legally, and the government issued passports very sparingly, at least in the early days. Then, during the economically stagnant 1960s, Yugoslavia's dictator Josip ‘Tito’ Broz opened the borders and allowed Yugoslavia’s citizens to seek employment outside the

country, thus creating a diaspora of hundreds of thousands of migrant workers. It also allowed criminal gangs and political opponents, both suppressed within Yugoslavia, to thrive outside it.

For Arkan, nothing about school, or the society he saw developing around him, held much appeal. By 1980, there were an estimated one million Yugoslavians working abroad. He believed that it was his destiny to join them. A fan of Western movies, comic books and science fiction novels, Arkan grew tired of escapism and sought ways to bring his fantasies to life. Although he was a student loaded with potential, Arkan bunked off school to hang out with friends and chase girls. He first ran away from home aged nine, taking an eleven hour journey to the Croatian coastal city of Dubrovnik. According to legend, Arkan stole a car to make the trip, but even for him that was unlikely, and in reality he probably took the bus and train. Still, it was quite a stunt. After sending a letter to his mother, apparently informing her of his plan to cross into Europe, Arkan’s furious father soon arrived to collect him.

Fast forward a few years, and teenage Arkan had morphed into a tall and charismatic young man. Friends called him Hybrid because he had a large head perched atop a slender frame. The focal point of that head was a baby face, a description that would remain with him throughout his days as a bank robber, gangster and warlord.

Arkan dreamed of living a life of crime, but that was a risky prospect inside Yugoslavia. Murder, rape and even some robbery offences could all be punishable by death. As he drifted towards a gang lifestyle, becoming a teenage pickpocket and holding up local shops, Veljko became ever more insistant that his son should follow him into the military. Whenever he felt Arkan needed a short sharp shock, Veljko lashed out violently. “He would simply pick me up and hurl me on the floor with all his might,” Arkan later recalled. On one occasion, after Arkan cracked a joke about the prospect of Tito dying, Veljko dragged his son towards the window and dangled him outside by his ankles. Arkan became desperate to flee. As he later told his militiamen: “I’d rather live a day like a lion than twenty years like a fucking sheep.” He worked out assiduously and trained as a kickboxer, becoming muscular and potentially deadly with his legs, arms and hands, although he never bothered to enter any competitions. Arkan wasn’t training for prestige, but in preparation for something grander.

Arkan was first arrested in 1966. He spent a year in juvenile detention and then, aged fifteen, Veljko sent him to the port of Kotor, in Montenegro, to sign up with the navy. Kotor will become an important location in this story. But Arkan never made it to the city. Instead, he next emerged in Paris, from where

he was swiftly deported. By 1969, he was seventeen and serving a three year stretch at a youth facility in Serbia for a string of burglaries. There, he honed his physique further and developed a reputation as a leader. One account of his time there recalls the assiduously clean shaven Arkan keeping an immaculate appearance. His shirts were always well folded and his books stacked neatly in a corner, habits no doubt ingrained by his father’s strict regime. He was a class wiseguy, always talking back to the teacher and showing off his intellect, which undoubtedly was superior to most of the other lads’. Still, boys tried to bully him over his high-pitched voice. On one occasion, an inmate remarked: “You’re talking like a woman, are you a woman?” Arkan made no comment, but simply picked up a chair and crashed it over the other lad’s head. In time, Arkan became the leader of his own gang. A prison psychologist later offered some insight into Arkan’s mind. “His father’s harsh treatment created a man who was obsessed with the rule of his own laws,” he wrote. “Arkan was a man who didn’t have control when he was young, and because of that he strove to have total control when he was older and out of his father’s house.”

Arkan was released from jail in 1972 but was quickly re-arrested for another armed robbery. This time, he was handed a ten-year sentence in an adult prison near Belgrade. Things looked bleak, but within weeks Arkan had clambered over the outer wall and escaped. There are various stories about how he made it out of the country, including one wild claim that he held onto the underside of a train carriage. In any case, Arkan made his way to London and embarked on a full time criminal career.

Arkan lived in Chelsea and hung out at the Yugoslav social club in Kensington, a haunt for gangsters, dissidents, spies, diplomats and even actors. He took a part-time job as a bellboy, but also became a burglar. Arkan hung out with criminals running major stolen car rings and people smugglers, as well as gangs of professional thieves who stole to order from the West End’s flagship stores. He was lean and muscular, he wore his black hair long and wavy and favoured a leather trench coat, paired with expensive looking shirts and sharp suits. Arkan now looked like a gangster, and just to ensure that he made the right impression he topped off his look with Italian leather boots, where he kept a two-bullet pistol with a mother of pearl handle. A ladies’ gun, for sure, but potentially lethal nonetheless.

Arkan was an oddity even amongst the colorful collection of emigres at the social club. With his high-pitched voice, he was quiet yet articulate a deep thinker who swore by peach nectar rather than alcohol and snubbed his nose at cigarettes. He was such a straight edge zealot that he would later subject his cronies to regular drugs tests, and when at war the punishment for his men if

caught drinking would be one hundred lashes on the backside. He used various names, including Zeljko, Marco and Arkan, and pretended to be a businessman or diplomat when he met women. Because he could also speak Italian, French and German, it was relatively easy to assume a false identity.

Arkan arrived in Rome later that year. Linking up with a former friend who had already established a modest criminal empire in the city, working under the Sicilian mob. Crimes already included protection rackets, prostitution rings and smuggling. Arkan introduced another method of money making, one that had been growing in popularity in London armed robbery. At first he targeted grocery stores, pawnbrokers and gold shops, often fleeing on a bicycle rather than in a car, earning a reputation for unorthodoxy among his criminal fraternity. He also garnered a reputation as a gentleman thief, smiling during his crimes and dripping in over-the top manners. “You’re so beautiful, please be gentle and so kind and give me some charity,” Arkan was reported to have said to one attractive female bank teller as he robbed her. Within the police, Arkan was known as The Italian, because he was one of the few Yugoslavian criminals who spoke the language. He began to rack up arrests, but nothing seemed to stick. Arkan used the proceeds of his crimes to join high-stake poker games, sometimes traveling to Switzerland or Germany to play. Arkan was becoming a true international man of mystery. It was no surprise that this charismatic, determined criminal should become entwined with the sprawling Yugoslav State Security agency, or UDBA, Tito’s answer to the KGB.

At one point in his wayward youth, Arkan had been made a ward of his father’s friend, the Slovenian interior minister Stane Dolanc, who later became chief of the UDBA, a position he gained partially thanks to his close relationship with Tito. In later life, Dolanc would help Arkan out of various scrapes and was rumoured to have assisted in at least one prison break. “One Arkan is worth more than the whole UDBA,” Dolanc once said. So when Arkan killed for the UDBA, he was in effect acting just one step removed from the Communist leader himself.

Nobody knows for sure how Arkan’s relationship with the UDBA developed, or where he met his handlers to receive instructions. Because he travelled all over Europe, from London to Zurich, it could have been anywhere, there were UDBA sleeper cells and agents dotted across the world. In fact, anywhere that dissidents could be found, so too could Tito's agents and they usually had a license to kill. Bearing in mind that Yugoslavia was a federal republic woven together from many national groups, there were also many dissident factions.

Ironically, given Arkan’s later role as a Serbian nationalist paramilitary, many of the UDBA’s targets were themselves Serbian nationalists. According to some sources, it was the UDBA who began providing the false documents, weapons and cash that Arkan needed to continue building his criminal empire, in return for his services as a hitman.

Arkan’s first known murder was that of a restaurant manager during a robbery in Milan in 1974. Arkan blasted his victim with a shotgun in a panic. It left a gruesome scene, with the man reportedly cut almost in half by the blast. But he is thought to have carried out his first professional hit in 1979. On this occasion, Arkan was tasked with taking out a man supposedly planning to assassinate Tito. By day he worked at reception in a Zurich hotel, where Arkan strolled in and fired a bullet into his head as he snacked on a plumb. According to one account, published in Christopher S Stewart’s authoritative account of Arkan’s life, Hunting the Tiger, the man fell down dead with the plumb still in his mouth. Arkan’s second hit was carried out in Belgium in 1981, when Arkan and another man gunned down an Albanian dissident who wanted to overthrow the Communist regime there. Although it wouldn’t have affected Tito directly he didn’t want the region unsettled, because such revolutionary fervor might have a knock-on effect in the Albanian-majority region of Kosovo.

The total number of hits carried out personally by Arkan is estimated to range between five and fifteen, and it was said that Arkan carried out jobs as far afield as New York, Chicago and Toronto. Around this time, Arkan also ventured into various drug trafficking, smuggling, prostitution and protection enterprises in cities across Europe, expanding his own organisation and posting his lieutenants to places like Amsterdam and Rotterdam to oversee operations. Inbetween the robberies and assassinations came a string of daring prison breaks.

A few days after Christmas, December 1973, Arkan was arrested for a bank robbery in Belgium, ultimately being sentenced to ten years in prison. He spent six years in Verviers prison, before escaping in July 1979, dodging imminent extradition to Sweden for a host of further offences. According to reports, Arkan took advantage of a strike and slipped over a wall to freedom, although there has always been speculation that he was assisted by the UDBA. Arkan then carried out further robberies across Sweden and the Netherlands, before he was captured and jailed for seven years in Amsterdam. He escaped from prison again in May 1981, after somehow getting a gun inside the jail, probably with the help of Yugoslavian intelligence. Armed men waiting outside the jail were also reportedly involved. In any case, Arkan picked up his life of crime almost straight away, getting into a gun fight with cops in West Germany, in which he was wounded. This time, he was able to slip away from a prison hospital ward.

Two years later, Arkan was arrested during a routine traffic stop in Switzerland, where he again managed to escape from prison, in April 1983. But even Arkan must have realised that he would not be able to keep up this run of good luck forever.

It was time to go home.

Back in Belgrade Arkan didn't exactly keep a low profile. He began managing a notorious nightspot popular with mobsters, the Amadeus disco, and became known for driving through the city in a pink Cadillac. He dressed more than a little like Al Pacino in Scarface all white, wide lapelled suits and gold jewellery. Locals likened him to James Bond, calling him 007, but he was more like Scaramanga.

What really sealed Arkan’s reputation as an untouchable was an incident that occurred after a red rose, supposedly his calling card, was left on a counter during a bank robbery in Zagreb. Arkan’s mother’s home was visited by two civilian cops. When Arkan arrived at the property, he shot and injured either one or both of them, the story varies. Tellingly, Arkan was released without charge within two months, some say a mere forty-eight hours. Whatever the details, the incident sealed his reputation - nobody, not even the cops, could fuck with Arkan. Like Keyser Soze in the film The Usual Suspects, he was protected from up on high, if not by the Prince of Darkness, then by someone approximate. Amassing a small fortune and an ever-growing brood of children, he bought a property in the exclusive Dedinje neighbourhood, adorned with an imposing marble edifice that overlooked the Red Star Belgrade football club’s Marakana stadium.

In addition to his criminal empire, nightclub work, protection rackets, and high stakes poker games played across Europe, Arkan found time to take control of Red Star’s superfans, or ultras, known as the Delje, meaning the Braves, or Heroes. It was through the club that Arkan really cemented his legend. Arkan was a relative latecomer to the terraces, and it's questionable whether or not he was truly very passionate about the sport itself. But he could watch games from his balcony and had a secret tunnel built to access the stadium. He even opened up an expensive ice cream parlour outside his home to capitalize on match days, although it primarily became a haunt for mob figures.

Ultras had by this time obtained an unusually well-respected place within Serbia’s football culture. Notorious not just for their flares and violence against rivals, it was not unheard of to see hooligans make their way to the pitch to

openly threaten officials, or even charge into their own teams’ dressing room to berate players when things were going badly. As Yugoslavia teetered on the brink of collapse after the fall of Tito, and fate gave way to the rise of nationalists like Slobodan Milosevic, Serbia’s ultras, almost always right-wing, became more political and their chants referenced not only football, but the political and social situation as well. For example, they would sing lines such as “down with Croatia” while throwing three-fingered Serbian salutes.

But it was not enough to control things on the terraces Arkan needed an official position. So he simply announced his bid to become club president and that was that, he was voted in without opposition. Whether his move was inspired by real fandom is doubtful. Arkan had sense enough to know that with the Delje, he could control a ready-made army to surround his nearby fortress, if he should ever need to, and some of Serbia’s toughest men would pledge their loyalty to him. It’s more than likely that it was then-President Slobodan Milosevic himself who engineered the move. His head of state security, Jovica Stanisic, was on the club’s board, although no evidence of direct collusion between Milosevic and Arkan exists, except for a single photo of them together at the funeral of a deputy minister assassinated in 1997.

In any case, Arkan began instilling discipline early on. “You know these guys,” he told reporters in the wake of his takeover. “They're noisy, they like to drink, to joke. I stopped all that in one go. I made them cut their hair, shave regularly, not drink. And so it began, the way it should.” Furthermore, Arkan launched training sessions in hand-to-hand combat, and indoctrinated the men with nationalist songs and rhetoric. Bearing in mind that he had started out as a hired killer for Tito’s federal Yugoslavia, Arkan now seemed motivated by something else ambitions for a Greater Serbia.

The first sign that Arkan was transforming the Delje into something more came in early 1990, when Red Star travelled to play Croatia's biggest club, Dinamo Zagreb. There were fierce clashes between the two sets of fans, sparked by Red Star fans singing vicious songs against Croatia’s nationalist leader. More than a hundred people were injured in the hour-long battle around the stadium. Incredibly, Serbia’s future president, Aleksander Vucic, was among the Delje that day. A journalist and self-confessed Red Star ultra, he would go on to take a ministerial job in Milosevic’s government in 1998. Much later, Vucic would go on to hire football hooligans to police his own inauguration as well as allegedly perform other services for his government. Red Star controversially lifted the European Cup the following year (it was the last year before the competition switched format to the UEFA Champions League). But by then, Arkan had already moved onto the next stage of the plan.

On October 11, 1990, Arkan announced the creation of a paramilitary organisation named the Serb Volunteer Guard (SDG), formed from about twenty of his most loyal lieutenants and leaders from among the Delje. Arkan also sent scouts into the city looking for its most violent teenagers, as well as bank robbers and killers from the criminal milieu, including from within the country’s prisons. This was all done hand-in-hand with government connivance and funding. About two dozen members swore allegiance to Arkan at a ramshackle church, where all the men were baptised, including Arkan. Eventually, the group, which became known as Arkan’s Tigers, would consist of a core of some two hundred fighters, with a total membership of anything between five hundred and one thousand men (at times its numbers were said to swell anywhere from five thousand to nine thousand, when ranks ballooned thanks to ‘weekend warriors’ or a sudden influx of extra Red Star fans). Shortly after forming the Tigers, recruits began to receive training in weapons, explosives, hand to hand combat, and military tactics. Previously, the closest many had come to combat was on the football terraces, or streets and back alleys of Belgrade. It was this organisation, under the direction of Commander, as Arkan became known, that would blood some of the Serbian mafia’s future leaders.

Most important among them, for the purposes of this tale, was a young man named Luka Bojovic. Born in 1973, Bojovic was two decades younger than Arkan and just seventeen when the Tigers were formed. Born to a university professor mother and a father who ran Belgrade’s zoo, Bojovic could realistically have pursued a middle-class lifestyle. Good looking, charismatic, and with a head of thick, wavy hair (when not cut into a military buzz or shaved as a skin-head, as he was once pictured while being released from jail), Bojovic became one of Arkan’s protégés. As one former friend put it, much later: “I'm going to tattoo him. But I don't want the picture that was in the newspaper. The boy is not like that at all. He’s blond, beautiful like a doll. The guards are afraid of him. Everyone is afraid of him. He's a God there. It's not like he's dangerous. He’s normal, he's quiet.”

Even though he was young, Luka could often be found close to Arkan in the field, as Spanish journalists found when they came to interview the man himself. Luka piped up, declaring his fondness for Spain and that he would go there if he ever had to leave Serbia. “Valencia would be best,” he remarked. Known affectionately by the other Tigers as Pekar, he was handed authority beyond his years, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Arkan recognised his innate leadership qualities. The tiger cub seen being gripped by Arkan in the most famous photograph ever taken of him was reportedly borrowed from Luka's father’s zoo. Looking back, perhaps Arkan saw something of the tiger cub in

Bojovic himself.

After the war, Bojovic became known as The Baker, because he bought an artisan bakery in one of Belgrade’s more upmarket neighbourhoods, where he spent many happy hours feasting on pastries, sipping coffees and kneading dough. But he also became a top gangster. As we shall see, Luka ‘The Baker’ Bojovic retained absolute loyalty to his boss, even after Arkan’s eventual assassination.

Arkan’s graduation to paramilitary leader came at a crucial time in Serbia’s history, which is worth a brief review. The Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was founded in 1918, becoming the new state of Yugoslavia in 1929. It was never a happy union. Croats resented being ruled by Serbs; the majority Albanian population in Kosovo saw no reason why they should not be part of Albania instead; and Macedonian nationalists also began pushing for independence, virtually from the off. In the early days, it was the Macedonians who proved the biggest threat to the new regime. The kingdom was created by the Treaty of Versailles and was meant to bring peace and stability to the region, but King Alexander I, assuming dictatorial powers, set about trying to form a central Yugoslavian state by banning the historic regions and their political parties and flags, and imposing a new constitution. Although he gave up his dictatorial powers two years later, the king was assassinated during a visit to Marseille by a Macedonian revolutionary, who jumped onto the running board of the car and shot him dead. The French foreign minister, chauffeur and two civilians were killed in the subsequent gunfight and the assassin, who bore a skull and crossbones tattoo adorned with the name of his organisation, was struck down by a soldier’s sabre, shot in the head by a policeman and then beaten to death by the furious crowd, just to make sure.

In the wake of King Alexander’s murder, the country started out on the path to federalisation, a process pushed hard by the new fascist regime in Croatia. But this process was interrupted by World War Two, and in April 1941 Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers. The Luftwaffe bombarded Belgrade and other major cities, and more than 300,000 Yugoslavian forces were captured. The country was divided and occupied, and some 500,000 people were murdered by the Croatian fascists. Partisan resistance fighters emerged, including a panYugoslavian faction led by Croatian-born Communist Party member Josip Broz, known as Tito. With the Axis powers defeated, on January 31, 1946, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, united to

become the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, under Tito’s rule, with Belgrade doubling up as the federal capital city. Tito almost immediately distanced the country from the Soviet Union, despite modelling the new country on Stalin’s empire. He spoke out about both NATO and the Soviet Union, and accepted aid from America before leading the international Non-Aligned Movement. The country was eventually renamed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, to distance itself from the Soviet Union, and Tito became president for life when the new country came into being in 1963.

Tito dealt brutally with internal Communist Party challenges and in the early 1970s violently suppressed protests in Croatia calling for more civil liberties. Tito also faced claims that the republic was too greatly weighted towards Serbian influence, and he did make concessions by creating a new constitution in 1974, giving greater autonomy to the regions, including Kosovo, which gained autonomy but not, crucially, the right to secede from Yugoslavia, unlike the other republics. This would cause major problems in the decades to come.

While ethnic tensions bubbled away the veteran strongman maintained order until his death in May 1980. But then everything began to change. Like most Socialist regimes, the economy stagnated and by 1989 a wave of redundancies and business closures swept the country. The hardest hit regions were Serbia, Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. With ethnic tensions heating up and economic and social despair sweeping the federation, Yugoslavia became a tinderbox. By this point, the president of its most populous nation, Serbia, was a ruthless Communist politician named Slobodan Milosevic.

Milosevic was an outspoken supporter of Serbs living within Kosovo, who claimed they were persecuted by the majority Albanian population. He wanted to reverse the region’s autonomy and crack down on the growing Albanian separatist movement. Critics said Milosevic was motivated by nationalism and the overarching goal was to increase Serbian strength within the federation. Milosevic denied being a nationalist, but one incident in particular gave others pause for thought. In 1987, while in Kosovo addressing a 15,000-strong crowd of Serbian and Montenegrin protesters, who said they had been beaten by the police, Milosevic told them, “No one should dare to beat you again!” Further signs emerged the next year, when supposedly grassroots protests took place against the government in the autonomous region of Vojvodina, and in neighbouring Montenegro, where around one-third of the 600,000-strong population identified as ethnic Serb. The Vojvodina government was ousted and a key Milosevic ally took power. A similar so-called anti-bureaucratic revolution took place in Montenegro, where demonstrators were seen carrying Milosevic's portrait among their banners and chanting, “Strong Serbia, Strong Yugoslavia.”

Again, a key Milosevic ally became president. Milosevic was accused of being the secret puppetmaster behind the demonstrations.

Milosevic’s next move was to seize control of Kosovo’s police, courts, foreign ministry and defence department. The majority Albanian members of the Kosovo Assembly were intimidated into supporting the measures. Enraged ethnic Albanian citizens then boycotted elections in 1989, allowing Milosevic cronies to be elected by the Serb minority. Further restrictions on Albanian rights, including in education, followed. By early 1990, Milosevic effectively controlled two of Yugoslavia’s six republics and two of the autonomous regions. A new Serbian constitution was created, striking out the word Socialist from the country’s former name, and the new Republic of Serbia put in place an ostensibly democratic, multi-party system.

Amid fears that Milosevic next wanted to use the army and Croatia’s thirteen percent Serbian population to foment another uprising, paving the way to a Greater Serbia, Croatia held an independence referendum in which nearly eighty percent of the population voted to leave the federation. Croatia seceded in June 1991, alongside Slovenia. Bosnia and Herzegovina was next. Although the Serbian minority in Slovenia was only around 47,000, or 2.5 percent of the population, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbs numbered some 1.3 million people, or around thirty percent of the population. Serbian insurrections began in all three nations, with weapons supplied by the Jugoslav People’s Army (JNA), effectively now under Serbian control.

The first of the conflicts, known as the Ten Day War, was started by the JNA in the wake of the secession of Slovenia on June 25, 1991. Soldiers under orders of the federal government moved to secure border crossings, but Slovenian police and territorial army troops set up their own roadblocks, leading to tense stand-offs and some skirmishes, causing several dozen casualties. Fighting was brought to a halt on July 7, 1991, when Slovenia and Croatia agreed to a threemonth delay on secession. The JNA withdrew and, when Macedonia seceded in September 1991, there was no military intervention. But the story was radically different in Croatia and Bosnia, where Milosevic, and Serbian commanders and warlords on the ground, were determined to reintegrate what they saw as rebel states back into what was left of the federation.

This is where Arkan’s Tigers came in. The Croatian War of Independence of 1991-1995 took place amid a UN arms embargo which was easily circumnavigated by the Croatian Serbs. The JNA, with its overwhelmingly Serbian commanders, opposed Croatian independence and sided with the rebels. As a result, they had easy access to weapons supplied by the JNA. By mid-July 1991, the JNA had around 70,000 troops on the ground and fighting had spread

across the country. Although the conflict continued until 1995, most of the heavy fighting was over by January 1992, when a UN-protected zone, known as the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), was imposed along part of the Western borders with Bosnia and Serbia. This was overrun by Croatian forces at the end of the conflict. Around four thousand Serbian paramilitaries, including Arkan’s Tigers, tried to fight off the attack, but the fight was lost in 1995, and some 200,000 Serbs became refugees.

But of all the conflicts, the war in Bosnia, between 1992 and 1995, was the most brutal. The Bosnian Serb's political leader was the ultra-nationalist Radovan Karadzic, while the leading military man was General Ratko Mladic, of the JNA. Although the pair had a fierce rivalry, and Karadzic tried at one point to demote Mladic and seize military command himself, the pair were jointly responsible for the four-year Siege of Sarajevo, which left around 14,000 dead, as well as the Srebrenica massacre of July 1995, which saw eight thousand Bosniak men and boys slaughtered. Eventually, NATO airstrikes helped to pummel the Bosnian Serbs towards the negotiating table and the war ended with the signing of the Dayton Agreement on December 14, 1995, which officially recognised Republika Srpska as an entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Atrocities were committed on all sides but in April 1995 the CIA claimed that all but ten percent were committed by Serb militants (although it must be said that war crimes and attempts at ethnic cleansing also took place against Serbian populations). Most of these atrocities occurred in Bosnia, and Arkan’s outfit carried out a great number of them, although former members have always maintained that they only killed during the conduct of war and that the numerous other paramilitary organisations fighting on the Serbian side were to blame. Officially, the Tigers came under the command of the regular military, but Arkan and his men were given free reign to wage war as they saw fit. “History is coming back,” Arkan was quoted as telling recruits at a training camp. “But this time, the Serbs are going to fight back.” It was a nationalist rallying cry designed to instill a warrior mindset in men whose character and background might otherwise have precluded them from a career in most national militaries, and it was a sign that the Tigers would fight unconstrained by normal rules of engagement.

As Christopher S Stewart wrote in Hunting the Tiger, there were stories of prisons being emptied of Croat men who were never seen again; rape rooms and torture chambers set up at hotels; children crushed under tyre tracks; and hundreds of people who simply disappeared. Many of the Tigers’ worst acts were clearly efforts at ethnic cleansing, if not genocide. Indeed, sometimes Arkan reportedly collected a ‘cleansing fee’ of up to $2m from local Serb

leaders to ‘mop up’ their territory. And amid all this, the Serbian state was never far away. Arkan’s camps were visited frequently by Jovica Stanisic, the head of the State Security Service (SDB), the successor agency of the UDBA, who was later jailed for war crimes.

Milosevic probably authorised many atrocities, although direct orders have never been uncovered. Vojislav Seselj, leader of the Serbian Radical Party and like Arkan a high-profile paramilitary leader, later told how Milosevic was directly involved in supporting paramilitaries and controlled Serb forces during the wars. “Milosevic organised everything,” he explained. “We gathered the volunteers and he gave us a special barracks…all our uniforms, arms, military technology and buses. All our units were always under the command of the Krajina [Serb army] or [Bosnian] Republika Srpska Army or the JNA. Of course, I don't believe he signed anything, these were verbal orders. None of our talks was taped and I never took a paper and pencil when I talked with him. His key people were the commanders. Nothing could happen on the Serbian side without Milosevic’s order or his knowledge.”

This book will not dwell for too long on Arkan’s war crimes, but according to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), under Arkan’s command the Tigers took part in ethnic cleansing and massacred hundreds of people in eastern Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Arkan was indicted by the ICTY in 1997 and the Serb Volunteer Guard was charged with numerous offences, including the transport of twelve men from Sanski Most to an isolated village where the men were shot; the transport of sixty-seven men and one woman from Sanski Most, to an isolated location where they were shot; and various allegations of unlawful detention in inhumane conditions, sometimes resulting in deaths. At one point, Arkan’s Tigers took part, alongside other forces, in the killing of at least forty-eight civilians. “Most of the dead had been shot in the chest, mouth, temple, or back of the head, some at close range,” the ICTY found in a war crimes case against Stanisic and another top Serbian intelligence official, Franko Simatovic. Some atrocities committed by Arkan and his men were said to involve hundreds of victims, with the total killed by the Tigers both military and civilian estimated at around two thousand. When one Tiger confessed to the slaughter of three hundred people at a hospital in Vukovar, an act of which Arkan denied any involvement, he admitted: “We have a people’s court here. You shoot and that’s it.”

Meanwhile, Arkan never lost sight of his criminal origins. Always with the conquest of any town, village, or territory, came plunder. Looting was commonplace and Arkan always found a buyer on the black market, be it for a television set, refrigerator, or jewellery, sometimes dug up after being buried in

the back garden by its fearful owners. As one witness recalled: “You could always recognise Arkan’s men. They had dirty fingernails from digging.” When a wide-ranging UN embargo was imposed on Yugoslavia, Arkan found a way to make even more money. He sent one of his top lieutenants as an emissary to Italian Camorra boss Francesco Schiavone. Through this relationship, Arkan made millions smuggling cigarettes, weapons, heroin, and other goods into the region through Albania, with Schiavone using his connections to stop Albanian mob bosses from blocking the smuggling routes. In return, Camorra families were allowed to set up shop in Serbia, buying up land, farms and businesses at knock down prices ‘negotiated’ by Arkan. Montenegrin crime Clans were also involved in the network, as they had long-standing ties to some of the Italian groups. This may well be where Luka Bojovic began to make his connections with that country’s future top mafia figures, many of whom would be tied to the Skaljari Clan, as we shall see.

Once again, it was all made possible by the collusion of the state. Arkan’s men were always able to get their hands on fake documents and licenses, and never had to worry too much about officials poking their noses in. Nobody stopped a vehicle adorned with the tiger emblem of the Serbian Volunteer Guard, and that was the oil that lubricated the whole system once Arkan’s goods were inside Serbia they were completely untouchable. At Arkan’s base of operations in Erdut, Croatia, he even constructed a sprawling fuel depot and general storage depot, dubbed Arkansas. The UN estimated that Arkan was making about $30,000 for every tanker that left the depot, at one point profiting by as much as one million dollars per day. Milosevic’s gangster son Marko, as well as Jovica Stanisic, were among those taking a healthy slice of the profits. As Christopher S Stewart said in his book Hunting the Tiger:

In time, the sanction-busting world in the Balkans would resemble something the West had always been fighting off the influence of the mob where there was no legal economy. In America, the mob had taken over prostitution, gambling, and drugs In Serbia, in the absence of any legitimate economy, the mob took over everything. The mob was not just a few people, or one family. The mob became the whole damn state

As we shall see, many of these links between the state and the underworld would be hard to shake off even after the shift to a more liberal democracy. Tellingly, Serbia’s prime minister from 2014-2017, and president from May 2017 until the time of writing, Aleksander Vucic, was a Milosevic government official, who served as information minister from 1998-2000. Having risen up from the Delje and through the ranks of the ultra-nationalist Serbian Radical Party, he oversaw chilling repression of the media, fining journalists for reporting critical views of

the government and other transgressions, such as referring to Albanians killed in Kosovo as “people” rather than “terrorists”. During his tenure, one journalist, with whom he was involved in a personal feud, was killed in a state-sponsored assasination. This sweeping media repression extended to censoring articles prepublication and booting out all foreign press from Serbia. Vucic later tried to distance himself from his past by admitting to “mistakes” and disavowing the “horrible crime” of the Srebrenica massacre. Even so, he later hired underworldlinked football hooligans to police protests at his inauguration, and the controversy did not stop there, as we shall see later.

At the time, Arkan and his associates were far from the only figures profiting from the war and the general sense of lawlessness inside Serbia. Inflation was running at about 10,000 percent. It was dog eat dog. Weapons flooded the region and armed mobsters flourished in Belgrade and elsewhere, amid an explosion in vice, protection rackets and, increasingly, drug sales and trafficking. Before the war, murders in Belgrade were rare. In 1992, there were seventy-two. In 1993, there were at least 144. Apartment blocks started taking on armed guards, nightclubs began asking visitors to check in their firearms alongside their coats and jackets. Many of these rackets were controlled by Arkan, or if not, other gangsters paid Commander a hefty fee for their right to independence. If they failed to do so, they were swiftly and permanently taken out. The top men in Arkan’s criminal empire were mostly Tigers, who carried ID cards that made them equally as untouchable as their boss. As we shall see, this insertion of former Tigers into the upper echelons of the criminal underworld would have far reaching consequences.

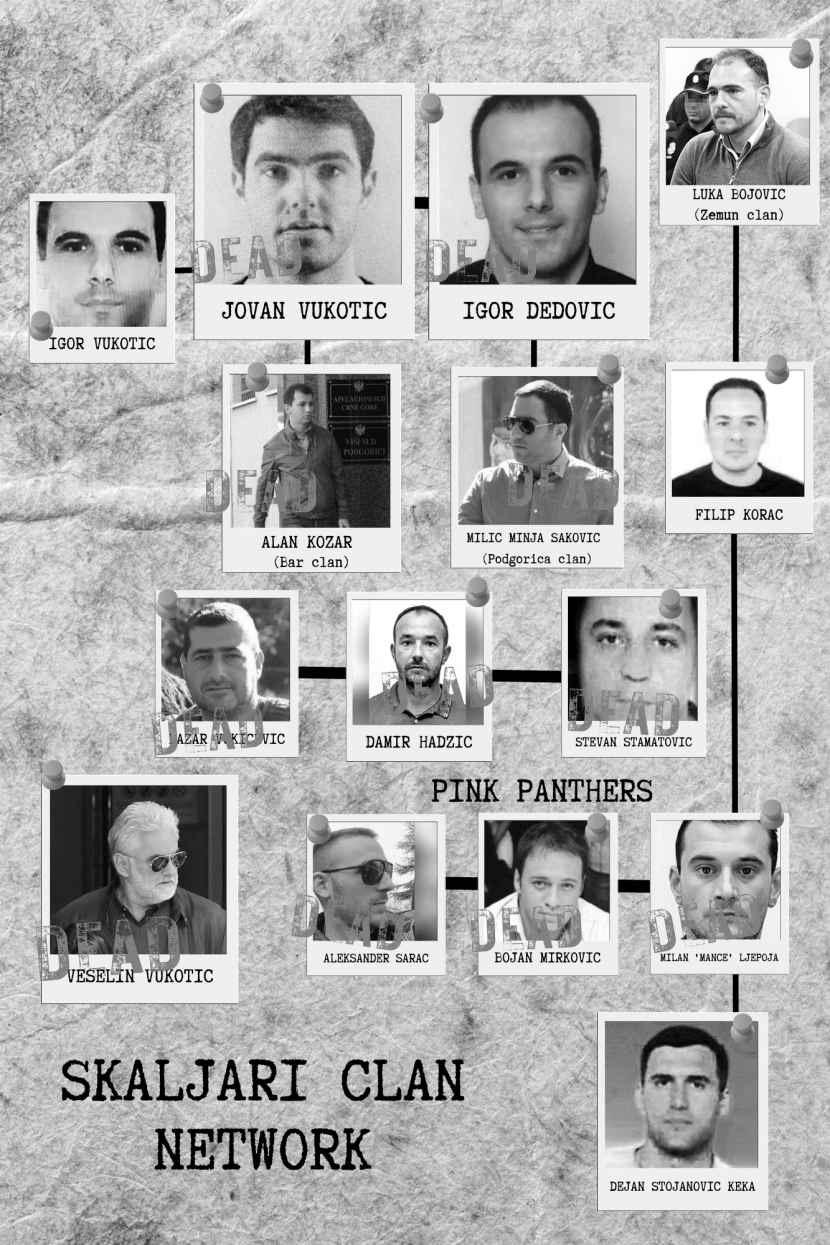

Perhaps just as significantly, in hindsight, was Arkan’s association with a Montenegrin casino boss named Veselin Vukotic. Although not a paramilitary, Vukotic was a former petty criminal and fellow UDBA assassin notorious for his part in killing a high-profile Kosovan dissident in Brussels in 1990. Vukotic’s Belgrade casino was frequented by most top Milosevic officials, and Vukotic met there regularly with Simatovic and Stanisic, among others. He also reportedly gave them access to drugs and prostitutes. On at least one occasion, Milosevic himself attended one of these meetings, while Vukotic was regularly seen in the company of the president's son and daughter. Vukotic helped Arkan permanently settle at least one problem with a rival upstart, and he was probably an important connection too for Arkan’s young protege Luka Bojovic, as he would go on to form a close bond with Veselin’s eldest son, Jovan Vukotic. As they both progressed up the criminal hierarchy, Jovan Vukotic would go on to control his own criminal organisation based in Kotor the Skaljari Clan which allied itself with the Serbian outfit later controlled by Luka Bojovic, the