Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/desert-jewels-cactus-flowers-of-the-southwest-and-m exico-john-p-schaefer/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The Letters of Barsanuphius and John: Desert Wisdom for Everyday Life John Chryssavgis

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-letters-of-barsanuphius-andjohn-desert-wisdom-for-everyday-life-john-chryssavgis/

The Letters of Barsanuphius and John: Desert Wisdom for Everyday Life John Chryssavgis

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-letters-of-barsanuphius-andjohn-desert-wisdom-for-everyday-life-john-chryssavgis-2/

The Missing Jewels Hayley Leblanc

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-missing-jewels-hayley-leblanc/

The Hayley Mysteries: The Missing Jewels Hayley Leblanc

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-hayley-mysteries-the-missingjewels-hayley-leblanc/

A Portrait of Assisted Reproduction in Mexico: Scientific, Political, and Cultural Interactions 1st ed. Edition

Sandra P. González-Santos

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-portrait-of-assistedreproduction-in-mexico-scientific-political-and-culturalinteractions-1st-ed-edition-sandra-p-gonzalez-santos/

The Siberian World John P. Ziker

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-siberian-world-john-p-ziker/

Agents of Subversion: The Fate of John T. Downey and the CIA's Covert War in China John P. Delury

https://ebookmass.com/product/agents-of-subversion-the-fate-ofjohn-t-downey-and-the-cias-covert-war-in-china-john-p-delury/

Diamond (The Bratva Jewels Book 2) Ja Low

https://ebookmass.com/product/diamond-the-bratva-jewelsbook-2-ja-low/

Pearl of the Desert: A History of Palmyra Rubina Raja

https://ebookmass.com/product/pearl-of-the-desert-a-history-ofpalmyra-rubina-raja/

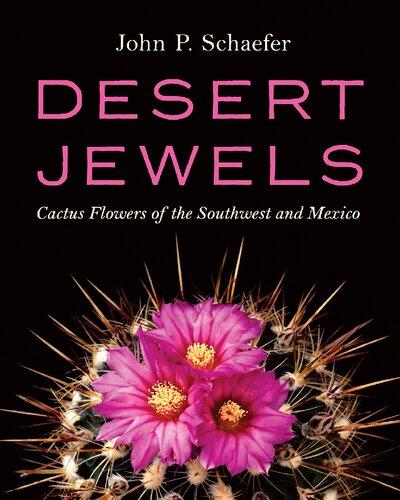

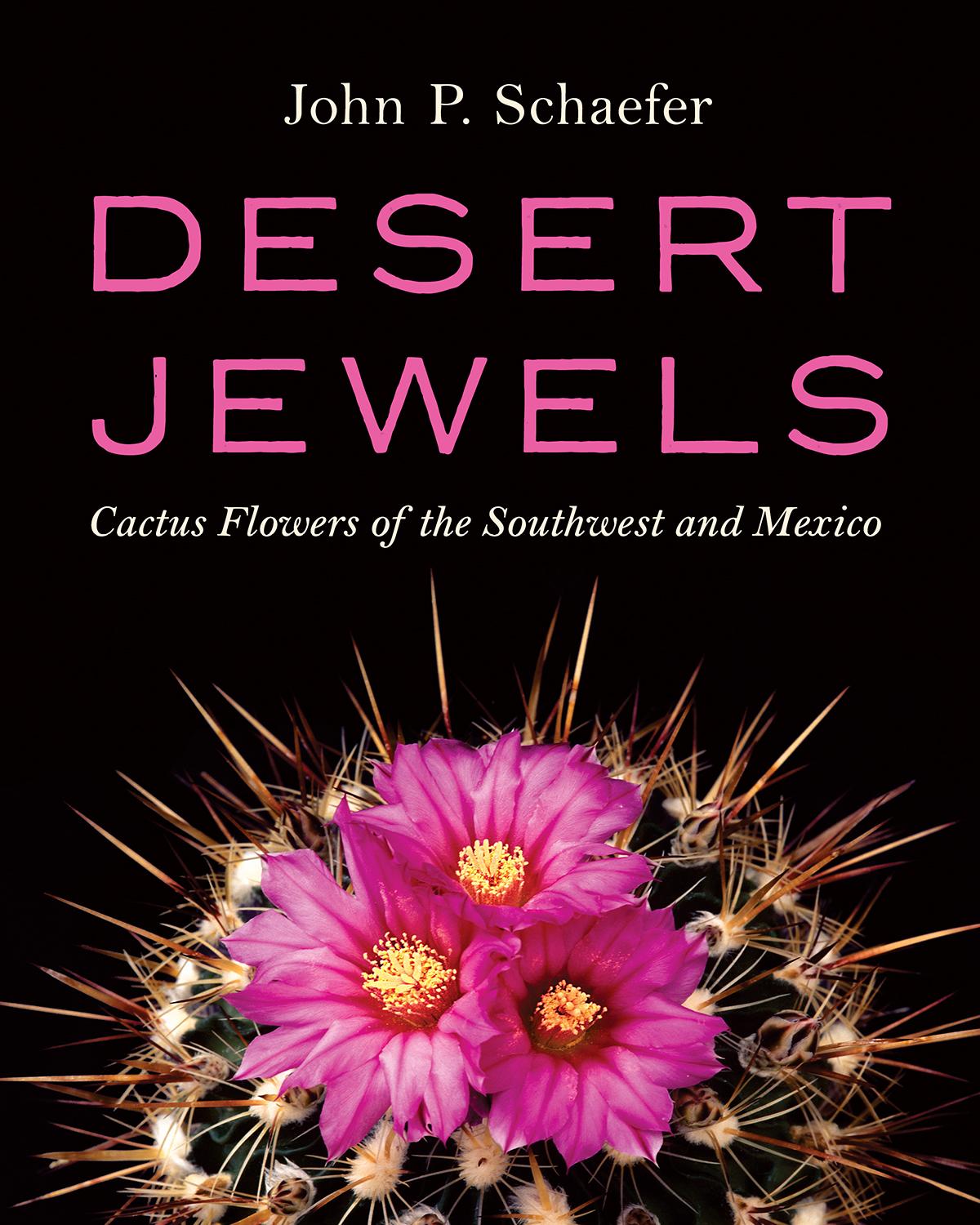

desert jewels

Cactus Flowers of the Southwest and Mexico

JOHNP.SCHAEFER

SENTINEL PEAK

An imprint of e University of Arizona Press www.uapress.arizona.edu

We respectfully acknowledge the University of Arizona is on the land and territories of Indigenous peoples. Today, Arizona is home to twenty-two federally recognized tribes, with Tucson being home to the O’odham and the Yaqui. Commi ed to diversity and inclusion, the University strives to build sustainable relationships with sovereign Native Nations and Indigenous communities through education o erings, partnerships, and community service.

© 2023 by John P. Schaefer

All rights reserved. Published 2023

ISBN-13: 978-1-941451-12-0 (hardcover)

ISBN-13: 978-1-941451-16-8 (ebook)

Cover design by Leigh McDonald

Cover photograph by John P. Schaefer

Art direction, design, and typese ing by Leigh McDonald

Editorial direction by Kristen Buckles

Typeset in Arno Pro 11.5/16 and Golden WF (display)

Publication of this book is made possible in part by nancial support from the University of Arizona Libraries.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schaefer, John Paul, 1934– photographer, writer of introduction.

Title: Desert jewels : cactus owers of the Southwest and Mexico / John P. Schaefer.

Other titles: Cactus owers of the Southwest and Mexico

Description: [Tucson] : Sentinel Peak, an imprint of e University of Arizona Press, 2023.

Identi ers: LCCN 2022015272 (print) | LCCN 2022015273 (ebook) | ISBN 9781941451120 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781941451168 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cactus—Southwestern States—Pictorial works. | Cactus—Mexico—Pictorial works. | LCGFT: Illustrated works.

Classi cation: LCC QK495.C11 S33 2023 (print) | LCC QK495.C11 (ebook) | DDC 583/.8850972—dc23/ eng/20220608

LC record available at h ps://lccn.loc.gov/2022015272

LC ebook record available at h ps://lccn.loc.gov/2022015273

Printed in China

♾ is paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Helen S. Schaefer, whose in nite patience put up with a lot of eld trips

Myrtillocactus 153

Neolloydia 157

Obregonia 159

Opuntia 161

Pachycereus 173

Pelecyphora 175

Peniocereus 177

Sclerocactus 183

Stenocactus 185

Stenocereus 191

Strombocactus 195

Thelocactus 197

Turbinicarpus 205

Index 209

PHOTOGRAPHSCOMMUNICATE what words alone cannot convey. Words are simply inadequate to describe the visual and emotional impact of the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Yellowstone, or Grand Teton National Parks. Art, when done well as either a photographic or painted image, bridges the gaps between looking, seeing, and perhaps knowing and understanding. e beauty of the Sonoran Desert and its surroundings is more subtle than spectacular. Some would say that it is an “acquired taste,” marred by harsh summers, prolonged droughts, a landscape bristling with spines, snakes, and an abundance of unfriendly cri ers. Nonetheless, it has a rewarding richness that encourages engagement. And it has been my home for more than six decades.

ough I grew up in New York City, camping and the outdoors have always been an important part of my life. Beginning as a Cub Scout, and through the ensuing years as a Boy Scout, Eagle Scout, and later Assistant Scoutmaster, I developed interests such as birdwatching that are still an enriching and important part of my life. When we se led in Tucson in 1960, leisure hours were o en spent exploring the countryside, and marveling at the unfamiliar plant and animal life and the di erent life zones that de ne our state. Binoculars and a camera were two constant companions. Recording places and events on lm began as a pleasant pastime but evolved into a determination to become a competent and serious photographer. Art classes in photography, building my own darkroom, and extensive reading and study followed; photography became a serious avocation.

My primary interest in the 1960s was photographing our surroundings in Tucson, taking advantage of the trails in Saguaro National Monument (now Park) and Sabino Canyon. I used large

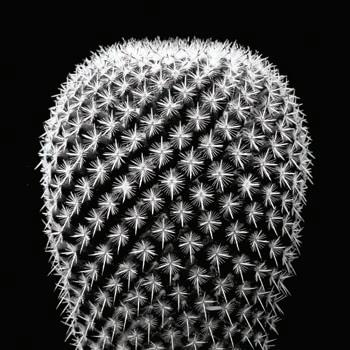

e pa erns generated by the individual and collective plant’s spines are what prompted me to photograph the plant in black and white. In color, the object is less visually interesting.

format view cameras that produced 4 x 5 or 5 x 7 negatives to make enlarged black-and-white prints. Time for long hikes and serious photography was scarcer when I became president of the University of Arizona, though other opportunities presented themselves as I traveled to interesting places around the world. Many of these images were the subject of an exhibition at the Tucson Museum of Art in 1997.

Two decades ago on a chilly December day, Helen and I moved from suburban Tucson to a home we had built in the desert near Saguaro National Park. Living amid relatively undisturbed desert o ered an opportunity to interact with the environment in far greater detail. So I began to look for plants with interesting shapes and forms. is quickly evolved into a new photographic challenge, spurred on by the nearby location of a cactus farm (see examples below). As the season changed, plants began to ower, and I quickly realized that I would need to make the transition to color photography to do justice to these subjects. Digital photography was still of marginal quality, unable to compete with the superb quality of lm, so I began to photograph cactus plants in ower with a medium format camera and transparency lm. In recent years I have begun to use digital cameras, and this is now the medium that I prefer for these subjects.

To date, I have photographed about seven hundred species of cactus plants and owers, primarily at the Arizona- Sonora Desert Museum, the Desert Botanical Garden, Tohono Chul, Tucson Botanical Gardens, the B&B Cactus Farm, and the deserts of Arizona and Mexico. e photographs that follow represent a small glimpse at a subject with an endless horizon.

Photographing cactus plants and owers, while not di cult, does present a variety of interesting challenges. Many species bloom only at night, with owers opening soon a er sunset and closing shortly a er sunrise. Consequently, arti cial lighting is necessary if the blooms are to be photographed during the night. Unless you have the equipment required to set up multiple ash units that simulate a natural se ing, using a single ash unit on camera usually leads to disappointing results.

I found that the best way to photograph night bloomers was to arrive on site about an hour before dawn and to begin taking pictures just before, during, and shortly a er sunrise. is does require careful study of the plant the evening before you photograph so you can set up the camera and tripod in the optimal location. Knowing with certainty that a particular bud will open on a speci c night is critical since owering of many of these species is usually con ned to a narrow space of nights.

On one occasion, when I was trying to photograph an Organ Pipe Cactus in bloom, I received word that a large plant near the entrance to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum would bloom that night. If I could get there just before dawn, there should be an ample number of owers to work with. Because I lived more than an hour away from the museum, I set my alarm for 3:00 a.m. and drove to the museum to arrive in ample time. Much to my chagrin, not a single ower was to be seen—they had blossomed and reclosed hours earlier. What had happened, and what no one had thought about, was that the plants were directly under some very bright security lights; the plants burst into ower at dusk, the lights came on automatically at dark, and the plants assumed the sun had come up and dutifully closed!

Another lesson learned.

Photographing plants in bright sunlight also presents problems. e range of re ected light from the shadow areas of the plant to highlights in the owers o en exceed the ability of the camera to record essential details of the entire subject. Photographing in open shade or shading the subject with a translucent white photographic umbrella works well (see adjacent photographs).

Desert plants are o en in environments clu ered with weeds, rocks, roots, and distracting objects. To isolate the plant and owers, I o en surround it with black construction paper. My backpack includes a pair of thick leather gloves, packets of black paper, tweezers and tongs, scissors, and Band-Aids (useful for inadvertent encounters with spines, etc.). Most of my photographs were taken with a macro lens, though for tall cacti I used a telephoto lens. Minimal processing of the digital les, either generated by scanning transparency lms or using digital data from the camera, was done with Photoshop, with care being taken to maintain the color values of the original subject.

Shielding the plant in open shade with a translucent umbrella reduces the harsh shadows generated by direct sunlight.

John Schaefer photographing a cactus ower.

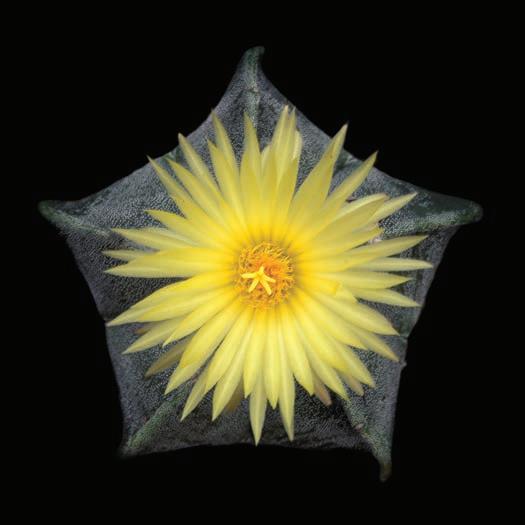

e Bishop’s Cap, Astrophytum myriostigma, before blooming time. See photograph on page 10.

e photographs that follow are a selection from the many I have made over a period of three decades. I have included representative species of most of the common genera of cacti that occur in the U.S. Southwest and Mexico. ese fascinating plants, native to the Americas, have become objects of interest to professional botanists as well as avid gardeners around the world; as a result, plant nurseries have led to their worldwide spread. Cacti native to South America o en do well in similar environments in North America and elsewhere, and it has become relatively easy to accumulate an exotic collection of plants for your own interest and pleasure from authorized dealers.

Many species of cacti are legally protected and cannot be moved or disturbed. is adds to the challenges that a photographer will face because being in the right place at the right time with a suitable se ing is o en a ma er of luck. Consequently, many photographs become “the best you can do under the circumstances” rather than the work of art that you envisioned. In reality, it is closely allied to wildlife photography, but the subjects don’t move quite as fast.

Naming cacti presents an additional challenge, as DNA analysis and other new technology o en results in name changes to individual plants as new botanical information is learned. All nomenclature in this book is generally based on Edward F. Anderson’s 2001 book e Cactus Family.

I hope that the following photographs will further the appreciation of these species and encourage the conservation e orts for their continued survival.

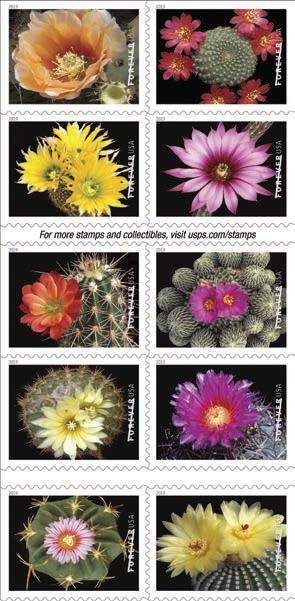

e U.S. Postal Service unveiled the Cactus Flowers Forever stamps on February 19, 2019.