CONTENTS

List of Abbreviations ■ vii

Introduction ■ 1

Part I. Mechanics and Genre

1. The Gameworld, the Interface, and the Genre: Red Dead Redemption and the Western in the Digital Age ■ 27

Sören Schoppmeier

2. Frontier Fatherhood: Examining Paternal Masculinity in Red Dead ’s Old West ■ 45

Shannon Lawlor

3. The Last Enemy That Shall Be Considered: Law and Order in Red Dead ■ 59

Robert Whitaker

Part II. Outsiders and Slow Death

4. Ecological Outlaws: Slow Violence and Natural Encounter, from the Arcade Western to Rockstar’s Digital Frontier ■ 77

Nicholas Blower

5. The Medicalization of Arthur Morgan: Tuberculosis as the Good Death in Red Dead Redemption 2 ■ 94

Arno Görgen

6. The Mechanical Machinations of Manifest Destiny: Winning the West and Vanishing the Indian in Red Dead Redemption 2 ■ 111

Ashlee Bird

7. “What’s Famous” and “What’s True”: Women’s Place from Revolver to Redemption ■ 128

Esther Wright

Part III. Representation and Meaning

8. Producing and Exploiting the Cultural Memory of the American West: Imperialism, Gender, and Labor at Rockstar ■ 149

Emil Lundedal Hammar

9. Moral Ambiguity and the Zombie Scapegoat in Red Dead Redemption: Undead Nightmare ■ 164

Poppy Wilde

10. Sublime Reflection and Mundane Realism in Rockstar’s Historic West ■ 183

John Wills

11. No Country for Old Tropes: Representation and Political Affect in Red Dead Redemption 2 ■ 203

Soraya Murray

About the Contributors ■ 221

Index ■ 225

ABBREVIATIONS

Revolver Red Dead Revolver (2004)

RDR Red Dead Redemption (2010)

RDR2 Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018)

Red Dead refers to the franchise as a whole.

INTRODUCTION

JOHN WILLS AND ESTHER WRIGHT

Albert Mason: “This is America after all, we hold a love for killers that borders on the macabre. Loving killers is part of our makeup.”

Arthur Morgan: “Maybe, maybe. But usually, we wait until after they’re dead.”1

It starts with a young boy in a Stetson, making finger guns at the horizon, and pew-pew noises with his mouth. His father returns home, greets his wife and son, assures them that their troubles are fi nally over—they’ve struck gold. He gives his son a pistol and sends him down to the river to shoot at his mother’s pots and pans for practice. Soon, he’s shooting at actual bandits invading the homestead, coming for his family. And not long after, we see the boy grow into a fearsome and resilient bounty hunter, in pursuit of the man who killed his parents on that day. Crudely animated (by today’s standards) and deceptively basic in its premise, you’d be forgiven for doubting at the time that this was to be the

backstory for one of the most successful and critically acclaimed video game franchises ever. But in many ways, it’s the perfect start to a Western adventure.

The expansion of Rockstar’s West from 2004’s Red Dead Revolver to 2018’s Red Dead Redemption 2 is, by and large, a tale of increasing ambition to capture a moment in time—a persistent fascination with perhaps the most enduring, iconic phase of American history in the popular imagination. Hundreds, likely thousands of works have been written about the nineteenth-century conquest of the American West, the region’s relationship to and foundation in our national popu lar culture, and the manufactured memories we now associate with it, which obscure any lived historical “real ity” that might once have existed.2 Thousands of pulp novels and Hollywood movies have depicted the Wild West frontier on page and screen. Yet in established critical analysis of Western history, image, and myth, the Western video game remains an afterthought—a quirky add-on, supplemental to the more “proper,” serious consideration of gaming’s more legitimate media ancestors. It cannot, nor should not, remain this way.

The Red Dead franchise represents perhaps the most impor tant intervention into the Western genre of the twenty-first century. Deeply inspired by canonical genre staples, the franchise has itself gone on to inspire new and impressive Western reboots like HBO’s Westworld (2016–), becoming a truly legitimate reference point and cultural anchor.3 This book is not a complete nor final reckoning with the power and meaning of Red Dead—no book could ever claim such a feat. But it is a start, and in this introduction we seek to map out some of Red Dead ’s broader context and content.

THE RED DEAD FRANCHISE

How to express in words on a page what the Red Dead franchise is, and does? While in their individual chapters throughout this book, our contributors explore various aspects of the franchise’s narrative and gameplay in greater depth, it serves us here to briefly sketch out the contours of Rockstar’s Western imagination, as it has been explored through three titles (so far).

In Red Dead Revolver, we follow Red Harlow—son of gold miner Nate Harlow and his Native American wife Falling Star—as he develops from a young boy playing cowboy to a bounty hunter in search of vengeance. A linear, arcadestyle game originally funded by Japa nese developer Capcom,4 and comprising levels and bosses of increasing difficulty, Revolver takes the player on a tour of archetypal Western locales—canyons, frontier outposts, homesteads, and plains. A patchwork of Italian Western music accompanies the gameplay. Hardly

a sophisticated narrative (and full of humor that now appears as crude and dated as the graphics and gameplay), Revolver nonetheless offers an undeniably, classically Western story of justice and revenge set in the 1880s. As a mostly silent, half-Native warrior, Red isn’t the only version of a Western trope the player meets, and gets to occupy the role of, along the way. The English gentleman sharpshooter (Jack Swift), a corrupt Mexican general (Javier Diego), a Native warrior (and Red’s cousin, Shadow Wolf), a hardy female rancher (Annie Stoakes), and a formerly enslaved Union soldier (Buffalo Soldier) all make an appearance in Rockstar’s first Western. In many ways, it’s a strikingly more diverse cast of characters than the visions of the West that Rockstar would produce later.5

Published in 2010 and set in 1911, Rockstar’s second Western, Red Dead Redemption (RDR) begins with Scottish American rancher and gunfighter John Marston stepping off a train in Blackwater. Once a frontier town, now with cobbled streets and gas lanterns, the world is changing, modernizing around him. He is already a relic of the past, a former outlaw brought back for one last job to protect his family, stepping into an uncomfortable future. RDR, as the first game in the franchise conceived and brought to life solely by Rockstar and for (then) “next-generation” gaming consoles, is naturally a more expansive and developed reckoning with the nature of the American West than Revolver. Offering an open gameworld, RDR afforded the player unrivaled opportunities (at the time) to explore the frontier: to encounter strangers made strange by its harsh landscapes, assist passers-by, ward off animal attacks, duel with villains, gamble and get drunk at saloons, and even collect prairie herbs. In gameplay terms, the title features a distinctive “Dead Eye” gunslinger mechanic that allows players to slow down the action, an established feature of other Rockstar titles like Revolver, Max Payne (2001–2012), and Grand Theft Auto V (2013). It features its own “honor” system reflecting player morality and fame for their deeds (or misdeeds). The story relates Marston’s untiring quest to save his kidnapped family held by Bureau of Investigation agents Edgar Ross and Archer Fordham. Marston becomes embroiled in all manner of skirmishes, rebellions, and bounty hunting (including taking on the remaining fragments of his old gang, led by Dutch Van der Linde). From an Ennio Morricone–inspired original score to a plot that borrows heavi ly from Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), cinematic and wider pop-cultural influences abound.

Red Dead Redemption 2 (RDR2) in many ways represents the apex of a contemporary wave of mainstream historical video games.6 The third Rockstar

Western features an even more massive and detailed open world, evidently meticulously researched and lovingly rendered. Hundreds of species of animals and types of flora populate a range of unique environments and landscapes. With side missions and online quests, the title offers hundreds of hours of gameplay. In place of Marston, it casts outlaw Arthur Morgan as playable-protagonist, while still fleshing out the backstory of Rockstar’s former leading man. Servicing Red Dead fans well with deeper insight into the exploits and downfall of the Van der Linde gang, and the increasing volatility of its patriarch, the game builds on prior stories. In that sense, Rockstar’s most developed Western world and narrative, an emotive and somber lament for the “Old West,” is still a game anchored to and in ser vice of the story that its franchise predecessors established—for better, or indeed, for worse.

The history on show in RDR2 is on many levels breathtaking. The game hat-tips the advent of the motor car and electricity, the shadow of the Civil War and slavery, the suffragette movement, the rise of American industrialism and capitalism, and the power of Pinkerton detectives in their ser vice. It lavishly indulges both rural and urban architecture of the historic West, re- created painstakingly in composite, allegorical, digital form.

But the cornerstone of the Red Dead franchise has always been a masculine experience of the American West—and a white masculine experience, at that. The violent, tragic, poetic deaths of John Marston and Arthur Morgan as depicted by Rockstar—and their embedded claims that a man cannot outrun his foul deeds, no matter how steadfastly he seeks redemption—mark these stories with the indelible notion that such white men are the ultimate victim of American “progress” and civilization, and those who illicit such sympathies.7 Some of Rockstar’s staunchest criticism has been directed at the company’s stubborn refusal to turn its gaze toward anything else, at best—and at worst, to actively indulge in racist and sexist stereotypes, and the Western’s deeply conservative and colonialist ideological baggage, as later chapters in this book explore. The other cornerstones of the thematic engagement we find in the Red Dead franchise can be understood by looking deeper into the background at Rockstar itself and the developer’s branding.

RED DEAD AS A ROCKSTAR PRODUCT

For over two decades, Rockstar has resolved to “prov[e] the cultural status of video games” and their relative worth compared to more established (and more respected) media like film and television.8 To do so, they have by and

large drawn inspiration from, and sought to remediate,9 pervasive American cultural genres. That is, “Rockstar’s output as a studio almost exclusively consists of games which depict or reference iconic moments or specific examples of American cinema.”10

We can also read the company’s development history as a series of titles through which they have provided players with a distinctively “Rockstar” perspective on Amer ica, past and present. This is not to merely resurrect well-worn (and problematized) mid-twentieth-century discussions about the “auteur,” authorship, and intentionality.11 Game developers employ hundreds or thousands of individuals, each with their par ticular job roles and responsibilities. But ideas about authorship, vision, and genius have taken on a new power and value in the twenty-first century, having been weaponized by creatives and companies across the media industries and reconstituted into marketing discourses designed to persuade potential consumers of their worth.12 Rockstar is deeply embedded in such a trend. Marketing discourses for their games dedicate significant time and energy to claiming their “authenticity”: placing them in highly specific historical and cultural contexts, while assuring players that their games are the product of such a “Rockstar vision.”13 The essays in this book, at various points, dissect not only the possible meanings and contradictions of Rockstar’s vision of the West, but the machinations of the company behind it.

Rockstar’s games can also be defined by both an adoration for and a critique of American culture and society, a tension point that has caused debate among those who think and write critically about their output, and the meanings of their games. Where is the line between loving homage and critical parody, and merely hollow pastiche? Is it actually possible to meaningfully criticize what we love, to criticize cultural genres and structures so embedded in our everyday lives we almost no longer perceive them? Can we truly accept Rockstar’s games as “critical” interrogations of American society, culture, and history, when they other wise seem to rely so heavily on conservative stereotypes and outmoded historical assessments?14 Many chapters in this book attempt to address these questions, explicitly or more implicitly.

In hindsight, then, and with a keen eye fixed on the development of Rockstar’s brand identity, the fact that the company has been dedicated to a video game Western franchise for over fifteen years is not a particularly surprising creative (or economic) decision, especially given the place of the Western and ideas about the frontier in traditional American society and history (and the continued endurance of those symbols and myths). As a leading video game

brand, Rockstar continues to appropriate, exploit, and even amend an older product that once sold in droves, a “brand” of history popularly referred to as the “Wild West.”

WESTERN, HISTORY, AND GAMES

Like a modern video game with di fferent routes and difficulty settings, Western history is itself marked by competing pathways and intellectual challenges. The traditional history of the West—the most familiar and accessible of pathways—tells of pioneers moving West, in direct and linear fashion, with their trailblazing endeavors emblematic of a greater American journey and victory. The hubris of economic expansion, manifest destiny, religious salvation, and “civilizing” both the Native American and the wilderness invited easterners to take to the trails. It is a history that speaks to a nation’s grand mission—and still has potent currency. As President Barack Obama reflected, while speaking of the 1862 Homestead Act, “ There are certain things only a union can do,” as he paid homage to “the courage of our pioneers to settle the American West.”15

Such a history of the West owes much to early Western scholarship. Frederick Jackson Turner delivered his “frontier thesis” before the American Historical Association back in 1893. Although less than popularly received at the time, it became the standard-bearer for academic scholarship, and on some levels, the easiest way to navigate the region and its meanings. Turner connected the frontier (which he saw as closed in 1890, when the U.S. Census recorded the territory settled) with the making of Americans themselves. Caught in a position of “savagery versus civilization,” these new Americans emerged as a unique group of people. While Turner deified the farmer as the quintessential pioneer, others chose the cowboy as popular champion—not least William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who held his Wild West show just outside the World’s Columbian Exposition the same time Turner delivered his thesis there, as it is customary to point out in historiographical works on the scholarly and popular origins of “the West.”16

A more challenging route through history began its first steps not long after and emerged with greatest coherence in the 1980s and 1990s. In part a reaction to social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, “New Western” historians such as Patricia Nelson Limerick and Richard White sought to rewrite the history of the West around core themes of conflict, sacrifice, and loss. Rejecting traditional historical paradigms, the movement cast “the frontier” as irrelevant at best

(White excising the term from his work), an “F-word” expletive at worst. Indigenous, multiethnic, place-based, and ecological perspectives became newly impor tant, and the trail became one of tears more than triumph. In recent years, scholars have departed from both new and old perspectives, instead emphasizing the middle ground of Native–European interaction, the forces of settler colonialism, and the significance of the West’s global ties.17

The historic West relays di fferent messages to di fferent people. For some, the Wild West, rich in the mythos of individualism and “living off the land,” ser vices a collective nostalgia for altogether simpler times. A return to the “cowboy’s code” is offered as a truer, American way of living. For others, the frontier experience is a lesson in destructive behav ior. The past environmental horrors of westerly pioneering—the damage of hydraulic water jets during the Gold Rush, the wild rivers at standstill, congested with cut logs, and the suffocating storms of the Dust Bowl—presage and partner contemporary climate crises.

People learn about the competing histories of the West from a multiplicity of sources. Not just the preserve of academic scholars, Western history is something lived through and discovered by hand; it is located in the dusty photograph albums of family- owned farms, the barely legible guestbooks of vacationers at Yosemite’s Ahwahnee Hotel, the architectural ruin of ghost towns, the craftwork of Indian reservations, and the hot brand of cattle on the land. The history of the West has been relayed (with various degrees of accuracy) across every kind of entertainment media. From Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show to Ken Burns’s 1996 television documentary miniseries (simply titled The West) through to today’s podcasts and popular fictions, Western history is experienced by all.

In the last few decades, that delivery of historic content has included the new media of video games. As today’s most financially successful entertainment format (Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto V significantly outperforming Star Wars, for example), the cultural reach of video games is not to be underestimated. Historical video game series such as Medal of Honor (1999–), Call of Duty (2003–), and Assassin’s Creed (2007–) have undoubtedly shaped understandings and perceptions of the past. Alongside World War II, the Wild West as a historical theme has inspired a range of games dating back to the 1970s. Designed for the classroom by trainee teachers, The Oregon Trail (1971) was arguably the first Western computer game, and notably aimed to educate kids about frontier history. The text-based management title—creator Don Rawitsch called it a “simulation model”—sought to capture the hardship of pioneering,

imparting a playful sense of realism, with travelers hit by “bad illness” and “hostile” riders on their journey West.18 Other early game designers employed the historical West as a colorful canvas for action scenarios, a familiar backdrop in which to place a shooting game or a scrolling beat-’em-up. The gamifying of Western history included blatant divergences from the lived experience that deservedly courted controversy and protest. In 1982, Mystique released the adult- oriented soft-porn title Custer’s Revenge for the Atari 2600 console that depicted Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer raping Native women in retaliation for defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Women Against Pornography and the American Indian Movement protested the title. With heavy stereotyping of Native Americans, Activision’s Gun (2005) ignited similar boycotts.19

As the most successful Western video game series, then, Rockstar’s Red Dead promotes Western history to the widest audience yet. With over sixty million units in sales, Red Dead easily exceeds the ticket revenue of the biggest Hollywood Westerns, and highlights the broader reach of the video game Western. For many players—and indeed, many students—Red Dead provides their most extensive foray into Western history. Hardcore online players and story completionists expend in excess of one hundred hours residing in Rockstar country, immersed in a simulation of Western history far more complex than that offered by a single book or film. On the surface this is an exemplary “historical game,” a blueprint for representing historical research and arguments through the medium of games.20

The Red Dead series has also been universally popularly applauded. With a Metacritic average score of 97/100, RDR2 stands as one of the most acclaimed video games of our era. In her review for the Guardian newspaper, Keza McDonald declared RDR2 “a landmark game” and “a near miracle,” while Peter Suderman, writing for the New York Times, called it “the most ambitious game ever made,” “true art,” and “a new American epic for the digital age.”21 Considering its developer’s reputation for courting controversy, it is perhaps surprising that the series has been so well received. In part this owes to the perceived authenticity of the product, but also to Rockstar’s West being a place of (surprising) middle-ness in terms of historical depiction. Intriguingly, within its twisting story arcs and vibrant range of characters, Red Dead imparts traditional and revised histories of the West; it panders to an idolization of the violent gunslinger but also hints at the tragedy and complexity of the frontier. The exactitude of Rockstar’s “historic West” is one of the recurring themes of this volume.

STORYTELLING, INTERACTION, AND PLAY

The portrayal of history in Red Dead equally reflects a distinctly Western storytelling tradition. Perhaps more than any other period or place, the American West has inspired the richest of folklore. The first stories of the West date back thousands of years in the guise of Indigenous oral traditions. As Eu ropeans colonized western territories, aggrandized stories of faunal abundance and legendary hunts surfaced, followed soon by tales of mineral bonanzas and boom towns. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, Beadle and Adams dime novels packaged “the West” into a standardized story for the working classes, a neatly wrapped script of high adventure designed to titillate and sell alongside other speedily written stories about detectives, romantics, and pirates.22 Early-twentieth- century novelists such as Zane Grey enriched the definition of the West as a fictive adventure with bestsellers such as Riders of the Purple Sage (1912). Readers lapped up this imaginative and romantic frontier West made up of history, story, and nostalgia. The physical, tactile sense of turning pages kept the wagon trains going and the Indians at bay. Literature helped mold the frontier myth.

In 1903, Edwin S. Porter produced The Great Train Robbery, the first filmic Western. At just twelve minutes, Porter compressed the story of the West into a series of short, self- contained segments. The film told the story of outlaws robbing a steam locomotive, an image so enduring it continues to find its way into Western fictions, Rockstar’s included. The Western successfully morphed into a highly visual entertainment format, emerging as one of the founding genres of Hollywood. The Hollywood Western appealed because it told the tale of Amer ica; it also appealed because it brimmed with action, romance, rugged individualism, and villainy. The Western genre dominated mass entertainment from the 1930s through to the 1960s. At the movie theater, John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) and George Stevens’s Shane (1953) showed a richness of archetypes and landscapes. Famous cowboy actors included the “singing cowboy” Gene Autry, conservative icon John Wayne, and Clint Eastwood, “the man with no name” who would come to define the so-called revisionist wave of post-1960s Westerns for many. Meanwhile, Ronald Reagan took his cowboy-actor persona all the way to the presidency. Doris Day entertained in song in Calamity Jane (1953) while Sidney Poitier epitomized frontier panache in Duel at Diablo (1966). The sheer volume of celluloid titles across the years defied any single interpretation or message, though many have tried to offer such. While certain storylines

(cavalry fighting Indians, the redeemed gunslinger), heroic figures (not least Wayne’s white conservative), and historic myths dominated, the filmic Western exhibited a richness still worthy of exploration.23

In the 1950s and 1960s, televisual Westerns such as The Lone Ranger (1949–57), Rawhide (1959–65), Bonanza (1959–73), and Gunsmoke (1955–75), often based on radio shows, brought cinematic-style frontier storylines directly into the home. The Western story served as welcome addition to a suburban family’s TV dinner, providing an escape to simpler, less technological times. In the tumult of a depressed nation caught up in the Vietnam War, Watergate, and social strife, the cinematic Western nonetheless seemed precariously out of touch by the 1970s. Sergio Leone’s Italian genre deconstructions, and now-canonical revisions of Western violence by Sam Peckinpah in films such as The Wild Bunch (1969), eventually gave way to Westerns-in-space such as Star Wars (1977) and the traditional cinematic frontier largely disappeared from screen (at least for a decade).

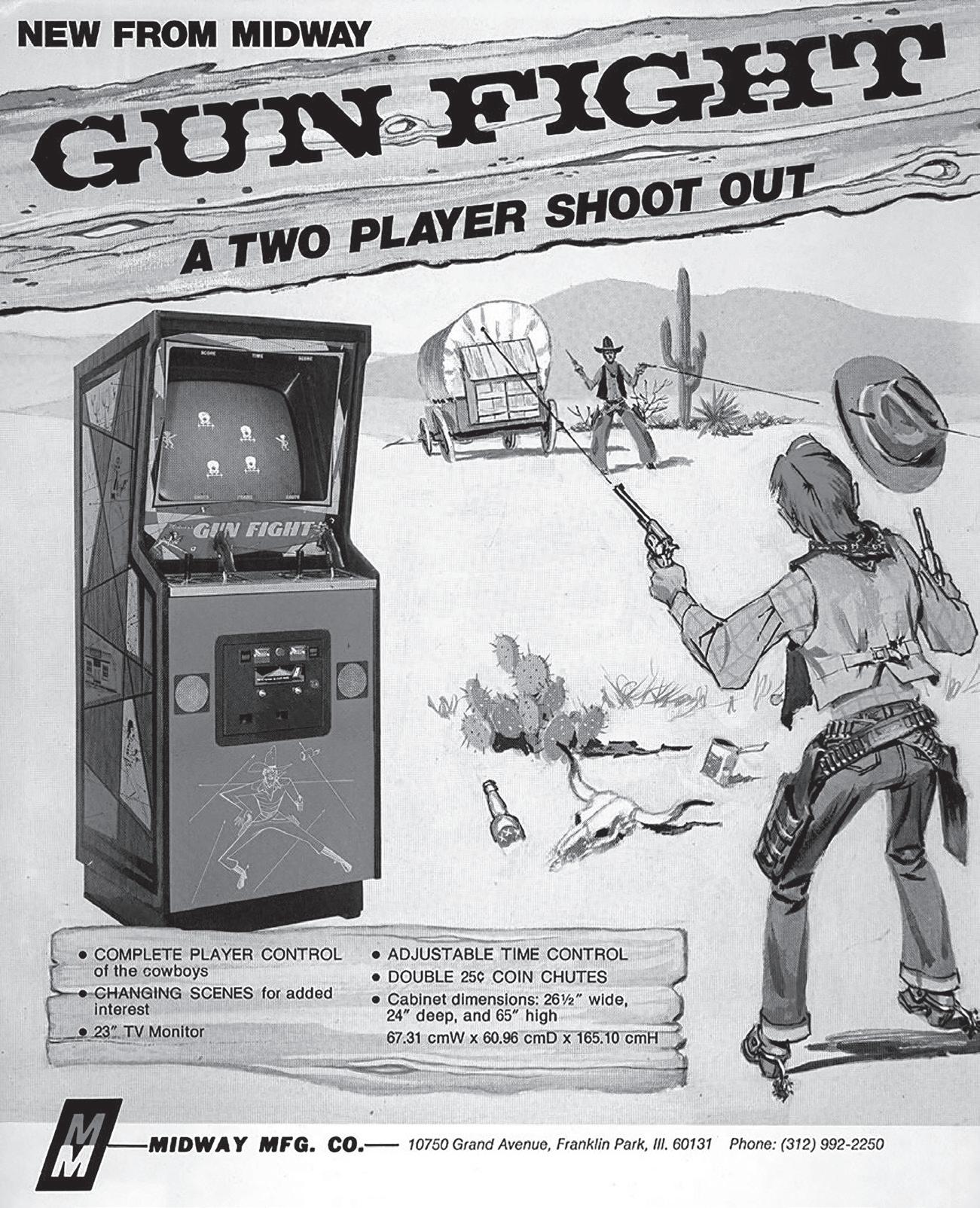

With new entertainment capabilities, the video game revisited past storyboards with gusto. In the 1970s, the first video game Westerns innovated in technology, but largely replicated the look and feel of Hollywood Westerns. An adaptation of Konami’s Western Gun (highlighting the West as an international story), Chicago’s Midway placed one of the first action Westerns, Gun Fight (1975), into the arcades. The game depicted two sticklike cowboys on screen, facing off against each other in a classic frontier duel. The limits of the computer hardware meant that both cowboys remained human- controlled, and a few pixelated cacti represented the whole of the trans-Mississippi landscape. Gun Fight lacked any quantifiable backstory; it nonetheless proved a commercial success.24 In the 1980s, black-and-white graphics turned color, pixels scrolled left and right, and the digital West became far more animated. However, the storytelling remained rudimentary, basic in tone and programming, and fundamentally task- driven, extending only to gunfighters rescuing damsels or seeking revenge or the occasional honing of gun or horse skills (as in SNK’s Lasso [1982]). Players were still left to imagine their own backstories.

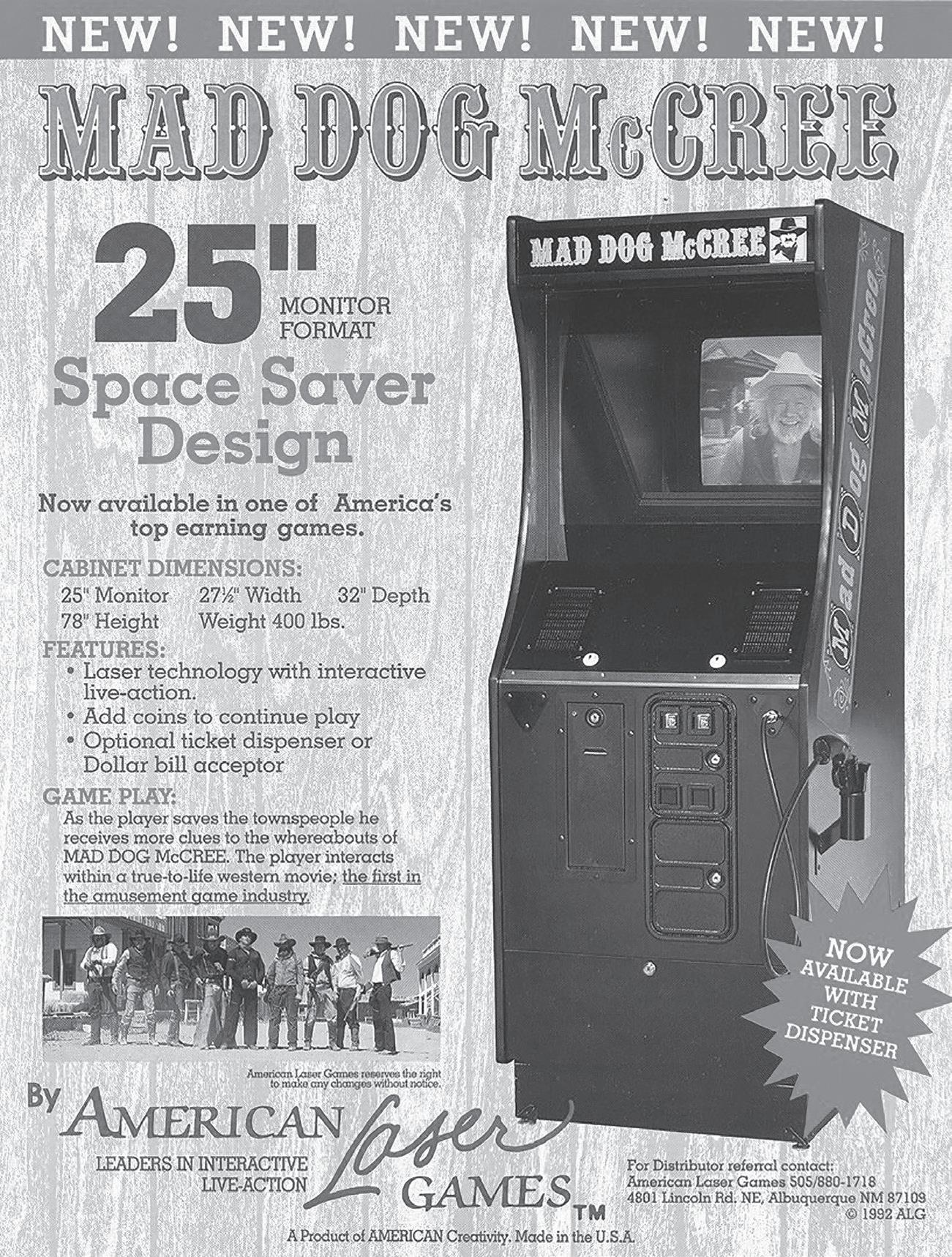

In 1991, Robert Grebe launched American Laser Games with the arcade title Mad Dog McCree. Shot at Eaves Movie Ranch, New Mexico, and deploying the latest laserdisc technology, the arcade machine featured live-action scenes straight out of the movies.25 Real actors spoke directly to the camera (and player), the old saloon doors of film- set buildings swayed, live horses brayed, and the player used a light gun to shoot at myriad actor-villains (the

Advertisement for Gun Fight, Midway, 1975.

hardware registering light changes). Like choreographed sections of The Great Train Robbery, players navigated successive stages of action, facing off Mad Dog himself in a duel at the end. Where once vaudev ille audiences ducked in their seats when outlaw Justus D. Barnes from Porter’s picture fired at them, now video game players watched Mad Dog go for his guns, then briskly shot back. Mad Dog McCree played like an interactive movie, and the Western video game seemed increasingly caught in its celluloid heritage.

Cowboy screenshot, Gun Fight, Midway, 1975.

Beginning with Spellbound’s Desperados (2001), and later Red Dead Revolver, Western video games in the twenty-first century shifted again, expanding on the storytelling capacities of the medium, offering more diverse perspectives, while again building on a long tradition of frontier storytelling. Filmic influences continued unabated, particularly in the guise of the revisionist Western, with the Red Dead series aping the aesthetics, audio cues, and nihilistic, violent scripts of Leone and Peckinpah movies.

Casting the spectator as player, the video game Western potentially offers new ways of engaging with the American West, as region, as history, and as a personal story. Interactivity powers the imagination and the senses, and the video game Western off ers all players the chance to personally frame and reframe the meaning of the frontier experience. Yet while the video game Western is undoubtedly distinctive, it is impor tant to note that a “playable” West existed prior to the modern video game era, and that the video game Western has historic entertainment ties. The West as amusement, as theater, and as play can be seen in the late-nineteenth- century exhibitions

Advertisement for Mad Dog McCree, American Laser Games, 1991.

of P. T. Barnum and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows. Cody reshaped his contemporary experiences of soldiering and bison hunting into playful acting, underlining the West as something mythic and meaningful, but also entertaining and dramatic. His shows brought a distinctive dramaturgy to the West, and paying docents became witnesses (and on occasion active parties)

in the story. 26 Dude ranches meanwhile offered tourists a more practical cowboy experience.

Amusement parks in the twentieth century strengthened the ties between “Western story” and “imaginative play.” In the 1940s and 1950s, Walter Knott transported elements of old ghost towns to Knott’s Berry Farm in Buena Park, California, at that time a popular dining locale. The “Farm” duly became onepart museum, one-part fried chicken, with an emphasis on fun and frolics.27

Soon after, Walt Disney’s Disneyland opened, just seven miles from Knott’s (the two Walts knew each other), with Frontierland featuring movie-set style saloons and similar frontier shenanigans. Disney’s Frontierland underlined the sense of “Western history” as an entertainment “theme” ripe for popular consumption.28 More than just window-dressing (or Disney architecture), Frontierland served as an “immersive story” to be consumed by the paying masses—at that time, in the 1950s, largely a white suburban middle-class clientele, used to watching B Westerns at the cinema, less used to frontier hardship.

Inside amusement parks and early arcades, individual electromechanical rides and machines gave a more condensed version of the Wild West. Targetpractice games such as “Tin Can Alley” proliferated, while gambling machines appropriated Western themes (at Las Vegas, neon cowboy Vegas Vic welcomed players to downtown venues). Meanwhile, toy guns and frontier hats (Disney’s Davy Crockett’s coonskin cap was a bestseller in the 1950s) emphasized the idea of the West as a family-friendly fantasy. Playing “Cowboys and Indians” emerged as a staple playground activity for kids, inside and outside the United States. Adults meanwhile “played Westerner” on ranching vacations and camping adventures, and at rodeo.

The video game Western built on this sense of the West as a myth with which to identify, interact with, and most of all, play. While early arcade Westerns took their cues from Tin Can Alley and Hollywood, Rockstar’s Red Dead offers a far more adult-oriented and complex experience. Far from “Cowboys and Indians” in the playground, it nonetheless stops someway short of a history lesson. Our book helps explore exactly what Red Dead means for, and tells us, about the West today.

WHOSE WEST IS RED DEAD ’S WEST?

Across over one hundred years of Western storytelling, one thing remains remarkably consistent: the pivotal role of the white male hero, or often antihero. Across a range of media, storytelling of the West commonly relates a

white, heterosexual, masculine perspective, working to the detriment of historical realities, and undercutting any sense of the region’s true ethnic and gender diversity. Rather than a rich fabric of associations and shared stories, entertainment media have typically presented a narrow and oversimplified version of history. Wild West shows, dime novels, radio shows, film, and television have all excluded authentic Native American, Hispanic, Chinese, and African American representation in the pursuit of a white male gaze. The twentiethcentury Hollywood Western, a powerhouse in forging images of the region, has consistently relegated minorities to bit parts in a white-man’s drama, with the white male cowboy repetitively cast as pivotal perspective on the frontier experience.

Did the video game, as the newest digital media form, rally or supplant this hegemonic vision? In large part, the video game industry perpetuated preexisting biases. Ocean Software’s High Noon (1984) adapted Fred Zinnemann’s 1952 movie, the player cast as white male sheriff Will Kane (Gary Cooper), with a simple electronic version of the 1950s movie score playing in the background. Putting only white male pixel cowboys on screen, Gun Fight symbolized a Wild West built essentially around a singular identity. Games such as Exidy’s Cheyenne (1984) added tomahawk-wielding Native Americans, but only as colorful targets to shoot down. Reduced to simple caricatures, the heavi ly pixelated indigenous characters lacked detail and identity. The depiction of peoples other than whites relied most on tired stereotypes. Hispanic Americans appeared as simple gun-toting bandits (or “gringos”) in titles such as Wanted (1984) and Law of the West (1985). Divested of any meaningful presence, African Americans largely disappeared from the Western digital story, as if erased from the historical record. Meanwhile, (largely white) women appeared in Western games for titillation and for rescue, as in the buxom damsels trapped inside saloons in High Noon and the side- scrolling action title Sunset Riders (1991).

Only a few titles challenged the white male hero narrative, or the growing consensus of the Wild West as a digital playground for boys. The violent arcade shooter Blood Bros. (1990), an unlikely source of innovation, included the option of two players working together, one as a grizzled cowboy, the other as a Native warrior. Released in 2001, the real-time tactics game Desperados featured a roster of playable characters that included a female gambler (Kate O’Ha ra), an African American explosives expert (Samuel Williams), a Mexican bandit (Pablo Sanchez), and a Chinese teenager (Mia Yung) with a monkey as a pet.29

As noted earlier, Revolver at least offered players the opportunity to occupy the role of a variety of Western characters. Given advances in console technology and the resources available to a major game studio, the Red Dead series signaled a valuable opportunity to truly rework and repopulate the video game West. In Rockstar’s commitment to forge immersive gameworlds populated with unique nonplayable characters (NPCs), each with their own look and script, incorporation of diverse, realistic characters seemed likely. Yet, despite their presence in the historic West, African Americans barely featured in the open world of RDR, with Rockstar’s narrative sidelining period racism, discrimination, and segregation.30 The same could be said of the title’s treatment of Mexico and Mexicans, through the title’s superficial engagement with the Mexican Revolution, as well as its insufficient representation of Native American life and reservations: in RDR Mexican land and reservations existed merely as othered, exotic spaces for the white male hero to prove his mettle.31

Building on previous (wanting) storylines and absences, RDR2 initially looked set to improve matters, and the game’s cast of characters is indeed more diverse. Reprising his role from RDR, Javier Escuella, Mexican revolutionary and bounty hunter, appeared as a major character passionately loyal to gang leader Dutch. Lenny Summers, whose ancestors were enslaved, features as an amiable and dependable character, albeit with a tragic past. As a teenager, Lenny witnesses his educated father killed by drunken white men. After killing them for revenge he becomes a wanted criminal, finding a new family in the Van der Linde gang before his untimely death as a result of one of Dutch’s schemes. Like Lenny, Tilly Jackson enters the game as another favorable character at the heart of the gang and sometime confidant of Arthur Morgan. Another child of a former slave, Tilly is kidnapped at the age of twelve, taken from her mother by a local gang, the Foreman Brothers, before finding solace with the Van der Lindes. Both Lenny and Tilly express their unease the further south the gang travels to escape the law, a poignant reflection of their discomfort in the acute presence of the Civil War aftermath, heading toward former slave catchers and Confederate veterans unwilling to let go of the past. Another central gang member, Charles Smith, educates Morgan as he accompanies the gunfighter on a variety of missions. Smith’s identity as half-Black, half–Native American with his own complicated past provides some opportunity for players to encounter a di fferent perspective on the American West. But as Ashlee Bird explores in a later chapter of this book, the game’s engagement with and representation

of Charles’s identity, and that of other Native people in the game, are far from perfect.32

Yet undoubtedly the aim was to depict these characters with sympathy and realism. People like Javier, Lenny, Tilly, and Charles reveal a gamic West of marginal peoples with common backstories of racial hatred and exploitation. RDR2’s gameworld also communicates a subtler message about Western history, for those players who go in search of it. Rich in period ephemera, architecture, and a wide cast of characters, in some ways its atmospheric gameworld relates a larger and more complex story of Western diversity: from the unnamed Chinese NPCs found populating Saint Denis marketplace, to the Creole population of Lagras and Lakay in the Bayou Nwa, the game’s allegory for Louisiana. In part, it conveys a critical story about structural American racism and exploitation. From slave pens and metal chains to “Wanted” posters for runaway slaves, RDR2 reveals to the more intrepid and investigative player a West marked by hidden but enduring traumas. For Jonathan S. Jones, such a range of carefully placed historic items proves deliberate and collectively relates “one of Red Dead Redemption’s most compelling themes: the game’s overt condemnation of slavery, Jim Crow, and white supremacy.”33 Jones further highlights the role of Rockstar’s in-game morality system that encourages players to actively punish racism, with the killing of Klansmen deemed acceptable and fair game. Certainly, engagement with a complex and traumatic frontier past is present in this game. However, it would be generous to claim that the aforementioned characters and their personal histories, or such examples of (optional) environmental storytelling, are of vital importance to a game narrative still focused on white male outlaws. Indeed, that the incorporation of these characters and their complex backstories is in many ways problematic or superficial is hardly surprising if placed in a broader context of Rockstar’s other franchises, particularly Grand Theft Auto, which has been frequently criticized for its lack of nuance at best, and engagement with racist stereotypes at worst.34 RDR2 still seems, at least on the surface, a very conventional Western. It advertises a Wild West of railroad ambushes and riotous duels, it plays to traditional audiences with its sagebrush and sunsets, and ultimately gives the player no other choice than to be a white male gunfighter in a frontier story (be it John Marston in RDR or Arthur Morgan in RDR2). At this point in time, then, the Red Dead franchise remains somewhat caught in its narrow white gaze, and still ser vices Rockstar’s “vision” of the West as a space defined by white male violence.

BOOK OVERVIEW AND KEY THEMES

From anx ieties over masculinity and fatherhood to slow death and ecological consciousness, the chapters ahead cover a wide range of topics that inform the Red Dead series. The diversity of the pieces stems from the complexity and depth of Rockstar’s games. Drawn together, these contrasting authorial approaches to a singular media franchise show just how far studying games can bridge disciplines, with work on offer here drawing from cultural and media studies, environmental and Western history, film studies, and historical game studies. The interdisciplinary approaches found in this book highlight that studying games facilitates a fruitful conversation between critics and fields—and that games challenge us all to sometimes think a little differently.

In part I of this book, we tackle game mechanics and Red Dead’s relationship to the wider Western genre. In a sophisticated piece of game studies analysis, Sören Schoppmeier looks at the distinctiveness of the Western video game, and reveals how through its interactive, programmed sequences built around player choice, it does something quite di fferent from the linear narratives offered in Western literature and film. Schoppmeier shows us how Red Dead Redemption functions as a “database Western,” wherein players might select scenes, activities, and even histories with which to engage. Highlighting the significance of game mechanics, he shows us how a new media format can destabilize prior understandings of the West, even when it repeats many conventional tropes of the Western genre.

Keeping with the idea of the West as genre, we next turn to two core elements of many Westerns—masculinity, and law and order—and how they function in Rockstar’s gameworlds. Shannon Lawlor examines paternal male presence in Red Dead ’s Old West. Rather than an exploration of the gunslinging cowboy, all bravado and hurt, Lawlor notices something di fferent about the lead men in Rockstar’s West. She highlights how Red Dead focuses on anx ieties related to fatherhood and the need for paternal legacy, aspects of Western masculinity that have been other wise overlooked on the archetypal Hollywood frontier. Robert Whitaker then takes us on a tour of law and order in the realm of Red Dead, exploring the role of the Pinkerton detectives, and later the Bureau of Investigation, in the franchise. These three early chapters underline the importance of mechanics, genre, and history in the Red Dead series. They highlight how Red Dead is both revisiting and revising the Western genre—and with it, perceptions of Western history. The game series deviates from typical Western form,

with the process sometimes mechanical and directed, at other times organic and ambiguous. History, myth, and violence collide in the gameworlds of Red Dead, with both expected and surprising results.

In part II, we turn to themes of damage and othering. In “Ecological Outlaws,” Nicholas Blower tackles ideas about the passing of time (in and outside the game), and how RDR2 relays a distinctive sense of gradual ecological decline in its gameworld. Blower’s look at ecological “slow violence” contrasts with traditional (and much quicker) forms of “violence” typical to the old West (and well explored in Whitaker’s chapter). Blower offers the video game Western as an unexpected source of environmental consciousness. Arno Görgen picks up the broader idea of damage and disruption, then addresses it from a medical perspective. Görgen looks at how RDR2 explores illness and disease through lead character Arthur Morgan’s exposure to tuberculosis. In a sense another form of slow violence, the disease gradually overwhelms Morgan’s body, but also reflects his growth as a person (and leads to his ultimately “good death”).

Ashlee Bird and Esther Wright then explore two groups typically framed as outsiders in the central story of Red Dead: Native Americans and women. Bird argues that Rockstar’s series offers a colonial mode of play built around historic concepts such as Manifest Destiny, and only at best gestures to Indigenous representation. Wright meanwhile traces a troubling (and worsening) representation of women at the center of the series. That is, rather than embrace New Western histories and meaningfully incorporate them, the games instead increasingly marginalize women—and indeed usually only represent white women, where they are represented at all. The chapters by Bird and Wright engage with one of this book’s themes—how far Red Dead excludes as much as it includes, how the Rockstar West is a selectively programmed, choice-driven, and oftentimes problematic gameworld.

In part III, we ask broader questions about the series and touch on themes of capital, ethics, experience, and representation. Emil Hammar considers the economic systems at work both in producing and in playing Rockstar’s West. Hammar’s chapter is impor tant because it underlines how far games are part of today’s culture industry and caught up in the demands of a digital economy, including the difficult labor conditions that mark today’s games industry. Like Schoppmeier, Hammar is most interested in the greater systems at work behind Red Dead Redemption, the related motions of capital and game mechanics.

Poppy Wilde then takes us on a welcome detour to Rockstar’s Undead Nightmare, a fantastical, “Weird West” horror downloadable content (DLC) expansion

for RDR, wherein zombies prey upon cowboys. Wilde uses the spinoff title to unpack broader ideas about morality and citizenship; her piece also touches on familiar themes of othering and violence. John Wills then turns to senses of experience in the gameworld, looking at how Rockstar crafts both moments of sublime reflection, reminiscent of Western art by the Hudson River School, and mundane realism for the player. Wills shows how such a duality has much older roots in depictions and experiences of the American West.

Many of the chapters in this volume deal with aforementioned contradictions at the heart of Rockstar’s Westerns, the ways in which the Red Dead franchise can be seen to embody and espouse progressive and “revisionist” tendencies, but also conservative and traditional perspectives on the past and on the Western genre, sometimes seemingly in equal measure. Soraya Murray’s chapter, which closes out the book, reckons with this deliberately and reflectively, pondering what we are supposed to do with Red Dead as a particularly difficult object of study. Murray’s reflection considers issues of representation and meaning, and therein explores that greater question of message: what does the series mean not just for the individual player, but for American society? It reminds us that the question is not just whether Red Dead progresses or changes the Western, but whether it influences or changes us.

Despite the depth of work on offer here, notable gaps remain in our coverage. Revolver remains mostly on the fringes of our study, and from a strict film studies perspective, more could undoubtedly be done on linking the game series with the Hollywood Western. This has, however, been written about elsewhere, notably by Jason Buel.35 A critical perspective on depictions of African Americans and Hispanics in the games is also necessary, as others have argued.36 Meanwhile, Red Dead ’s tackling of the Civil War and U.S. soldiers is a focus of Jonathan S. Jones.37 We also wish to draw attention to the excellent foundational work on the series undertaken in the last fifteen years by other writers: on Red Dead ’s negotiations of masculinity in crisis, on Rockstar’s games and their relationship to contemporary “mediated nostalgia,” on notions of “historical accuracy” or “authenticity”, and on the promises and contradictions of Red Dead Online and how players have been testing its limits.38 More recently, Matt Margini’s book is an excellent primer on RDR ’s key themes, wider cultural and historical touchstones, and modes of interaction and play.39

The chapters ahead in spite of these challenges succeed in mapping out some of the core inner workings of the Red Dead series. They continue to deconstruct the game’s masculine lens, Rockstar’s predilection for violence, and the series’

complicated, at times, contradictory journey through the frontier West. They explore the outer workings of the game, especially how the title connects with today’s social values and today’s digital economy. One point we all agree on is that Red Dead amounts to far more than just a simple entertainment product. Rather than a closed-system frivolous experience, and a realm of pure escapism, the Red Dead franchise has the power to influence how we all see the West and Amer ica. The Western video game is a product that speaks to both our past and our present. Its significance lies in where that digital trail leads us.

NOTES

1. “Arcadia for Amateurs IV,” Red Dead Redemption 2 (Rockstar Games, 2018).

2. For our meaning of “conquest,” see Patricia Nelson Limerick, Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York: Norton, 1987).

3. See Simone de Rochefort, “Westworld’s Creators Were Inspired by Red Dead Redemption and BioShock,” Polygon, October 9, 2016, https://www.polygon.com/tv /2016/10/9/13221024/westworld-hbo -grand-theft-auto -nycc-2016.

4. For background, see Blake Hester, “How the Red Dead Franchise Began,” Polygon, October 17, 2018, https://www polygon com/2018/10/17/17986118/how-the-red- dead -franchise-began-angel-studios- capcom-rockstar.

5. Esther Wright, Rockstar Games and American History: Promotional Materials and the Construction of Authenticity (Berlin: DeGruyter, 2022).

6. The Red Dead franchise’s canonical status as a historical video game has made it a frequent touchstone for academics working in historical game studies, and how digital games function as a form of historical representation. See, for example, Dawn Spring, “Gaming History: Computer and Video Games as Historical Scholarship,” Rethinking History 19, no. 2 (April 3, 2015): 207–21; Adam Chapman, Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice (London: Routledge, 2016).

7. Esther Wright, “Rockstar Games, Red Dead Redemption , and Narratives of ‘Progress,’ ” Eu ropean Journal of American Studies 16, no. 3 (2021), https://journals .openedition.org/ejas/17300.

8. Esther Wright, “Marketing Authenticity: Rockstar Games and the Use of Cinema in Video Game Promotion,” Kinephanos: Journal of Media Studies and Popular Culture 7, no. 1 (2017): 136.

9. Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000).

10. Wright, “Marketing Authenticity,” 136.

11. Made popular in Anglophone film criticism in the 1960s by Andrew Sarris, “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” Film Culture 27 (1962): 1–8.

12. Leora Hadas, Authorship as Promotional Discourse in the Screen Industries: Selling Genius (London: Routledge, 2020); Anastasia Salter and Mel Stanfill, A Portrait of the