Like Saul on the Road to Damascus

On October 15, 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed the National Historic Preservation Act, which coincidentally was also the day that the Black Panthers were established in Oakland, California.1 That evening, the ABC television network broadcast the musical Brigadoon, starring Robert Goulet and Peter Falk, in which two American tourists discover a Scottish village that that had been frozen in time to protect it from change. Brigadoon served as an analogy for the transformation of preservation within the context of social, cultural, and economic changes that consumed the United States during the 1960s and beyond. The growing tension between the desire to preserve remnants of the past, like a fly stuck in amber, and that of adapting these resources as useful components of a relevant past was commonly expressed during the decade. By the end of the Johnson administration, the “New Preservation” was operationalized over the next generation as participants sought to expand the types of properties recognized on the National Register of Historic Places; to integrate the consideration of historic places within federal project planning; and to provide economic incentives for the rehabilitation of historic properties. The first generation of the New Preservation saw the gradual enhancement of the kinds of properties thought worthy of conservation, a process illustrated by the compilation of entries in the National Register of Historic Places, the institutional establishment of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs), Certified Local Governments (CLGs), and eventually, Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPOs); each seated within the rise of the Cultural Resources Management (CRM) enterprise. All of these administrative changes to the bureaucratic systems that managed the consideration and conservation of official memory took place within the context of the

modern American civil rights and environmental movements—a cultural intersection that has been little explored by historians.

Gambling in the Institution

In a famous scene from the film Casablanca, Captain Louis Renault, played by Claude Rains, loudly proclaims that he was “Shocked, shocked to find gambling” going on in Rick’s American Café. In a similar way, to find racist thought among historic preservation practitioners during the second half of the 20th century should not be surprising, given the privileged social background and economic status of many of the movement’s founders. No one should be shocked to learn that Alabama Congressman Albert Raines, who led the commission that laid the foundation for the National Historic Preservation Act, was an avowed segregationist.2 Other proponents, like Jane Jacobs, present a more complex story. Following her mantra, the preservation movement honored diversity, at least when it came to architectural styles, adopting the concept of a historic district with its variety of building types and uses. “The sense of history,” noted Arthur Ziegler, was “strongest in a neighborhood with many old buildings; where a progression of style exists, there can be equal interest in the changes that the neighborhood has undergone over the years.”3 Indeed, when asked to address “the Negro question” as part of her landmark book, The Death and Life of American Cities, Jacobs was remarkably silent.4

Jacobs’ dilemma presented a common pattern—that the pervasive and imbedded nature of structural racism was such that it was clearly not a problem that the preservation movement could solve. And yet one characteristic of the movement was that it often saw itself as precisely the right remedy for whatever ill was ailing American society. If Americans were “rootless” without an appreciation for continuity and community heritage, historic preservation and heritage tourism was the answer. If the country was involved in an energy crisis, the qualities of environmentally sensitive traditional design were a great solution. If communities were experiencing an economic downturn, then adaptive use of historic buildings was just what the doctor ordered because of the local economic impact of such endeavors. Since its entry onto the national scene on either side of World War II, the preservation movement was often justified as a useful community undertaking because of its pragmatic problem-solving collateral results. Of course, as shown by James Lindgren and others, the motivations among the white gentry who established many of the national, regional, and statewide preservation organizations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were never purely un-self-centered.5

Indeed, historic preservation in the post-World War II era justly earned and maintained its elitist image, with all of the incumbent characteristics of noblesse oblige as a justification for the maintenance of the status quo. Rather than question the presence of racism among the movement’s leadership, which was surely there, perhaps another appropriate avenue might more readily be to examine to

what extent the dominant culture of white supremacy influenced the criteria and conventions established during the 1960s. More importantly, once the inherent cultural biases of the founders were revealed, how did the movement change to accommodate a more diverse view of American history?

In fact, the extension of the continuum of historic significance to include places of state and local value was vitally important in expanding how practitioners viewed the kinds of places that a variety of people might find as worthy of conservation. Nationally significant properties included some 900 places in 1969 when the first edition of the National Register was published; a quarter-century later the list topped over 50,000. As in the biblical story of Saul on the road to Damascus, the movement was at first blind to its exclusionary content and conventions; its interpretive narrative that generally omitted all but white men; that centered high style over the vernacular: but once these sins were revealed, how did historic preservation’s advocates react, once the scales fell down from their eyes?

Hamilton Grange

Prior to 1966, the historic preservation community often failed to consider the values of minority, ethnic, and low-income groups. In some cases, racism was clearly at the core of the endeavor, in others the impact of a segregated society was perhaps more nuanced. One of the most troublesome episodes centered around efforts to relocate Alexander Hamilton’s home, “The Grange,” out of its Harlem neighborhood to what was considered by some a more appropriate setting.

Originally seated within a 32-acre estate, Hamilton Grange was moved for the first time in 1889 as the urban street grid of Manhattan reached 143rd Street. The home was adaptively used as the parish house for St. Luke’s Episcopal Church that was built adjacent to the new site. By the 1920s the home had become surrounded by larger structures that overwhelmed its setting and, in 1933, the site was acquired by the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (ASHPS), a New York-based association that was a leader in regional conservation activities on either side of World War II.

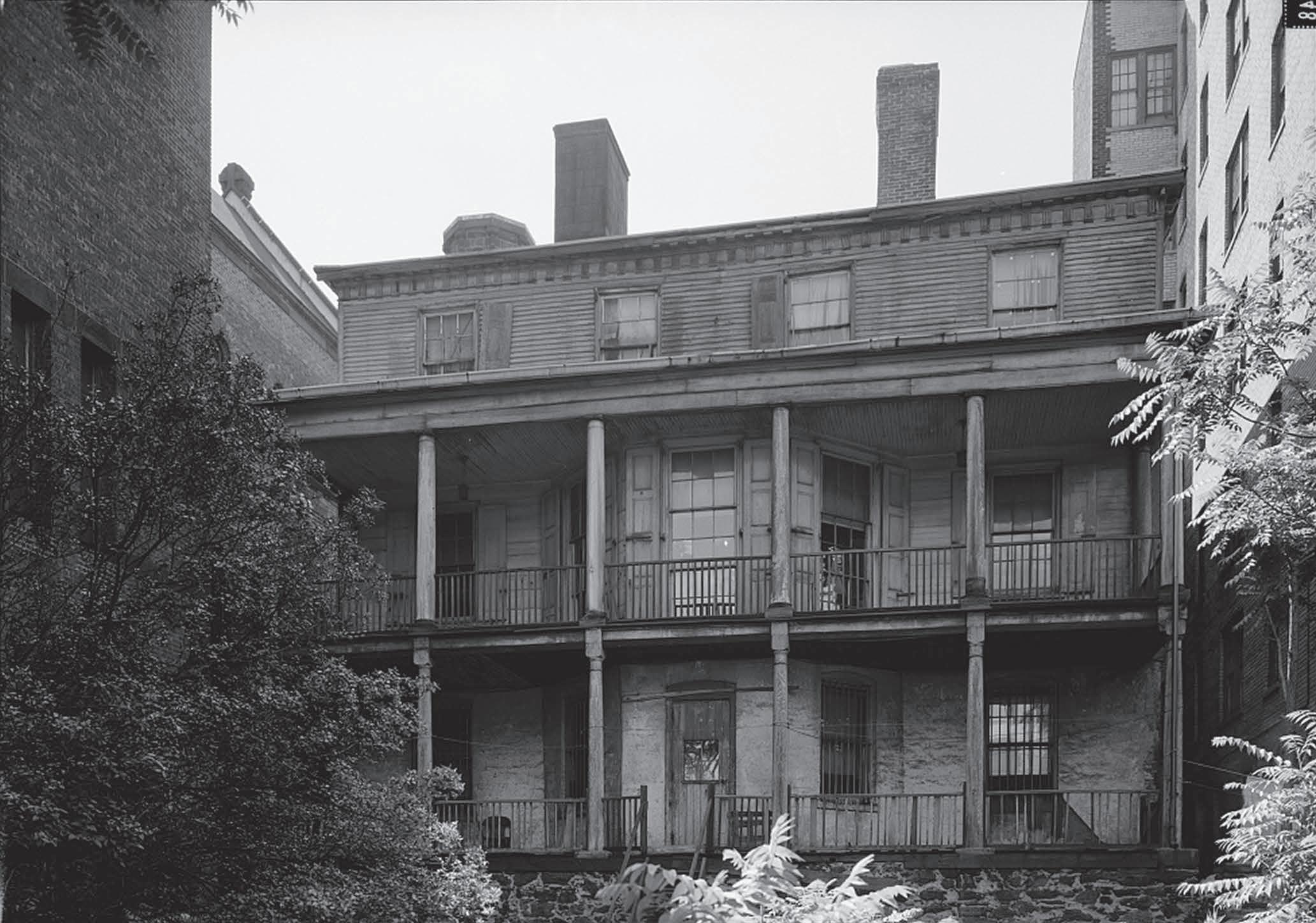

After operating the site as a traditional house museum, in 1950 the leadership of the ASHPS observed that the “shifting character of the population about the Grange” had resulted in a reduction in visitation.6 This solidified the Society’s emerging commitment to secure an alternative location for the building. Ten years later the building’s physical integrity and its neighboring environment had worsened. Despite frequent calls from preservationists and other influential persons, the city’s banking community refused to assist in rescuing and restoring the home to it is former glory. Encroachments were “so acute” that the environment was “disgraceful” and “completely unworthy” of Hamilton’s national stature.7 Seated in the shadow of newer buildings, with its distinctive porches removed, the home looked more like a “slum” than a “shrine.” Indeed, “compared to Mount Vernon

0.1

Grange, Harlem, New York City. Alexander Hamilton’s home, “The Grange” was moved first in 1889 as served as the parish house for St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. By the 1920s the home had lost much of its architectural distinctiveness and was hemmed in and overwhelmed by new construction.

Source: Historic American Buildings Survey: HABS NY-6335. Photograph by Jack Boucher, June 1962.

and Monticello, the Grange looked “more like the former residence of Uncle Tom than the seat of a Founding Father.”8

After private-sector efforts faltered, in 1962 Congress assigned the undertaking to the National Park Service which was left with three basic relocation options: retain the building at its present site; move it to a city-owned parcel in Harlem, or transport it across Manhattan to a new site adjacent to Grant’s Tomb. New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses had offered a small lot on the nearby City College campus and recommended that the home be converted for academic purposes. Park Service planners rejected the proposed adaptive use, preferring instead to continue its primary role as a memorial to Hamilton.9 With little previous experience with the impact of house museums the “distinction of having a national monument in the community” seemed to elude some Harlem residents.10 Other community leaders, such as future Representative Charles B. Rangel, saw the value of neighborhood conservation efforts to retain and enhance community pride.11

In the early 1950s, the noted architectural historian Talbot Hamlin had strongly urged moving Hamilton Grange to the site overlooking the Hudson

FIGURE

Hamilton

because it would provide an appropriate historical setting for the building where its architectural qualities could be appreciated within a reconstructed landscape. Having been assigned the stewardship of the memorial to General Ulysses Grant in 1958, the Park Service also envisioned economies of managing both properties on the same site. Regional Director Ronald Lee reported in 1965 that there was “no question whatsoever” in the minds of his professional staff that the Hudson River site “would be a vast improvement” over relocating the building within Harlem.12 Part of the justification was “recently discovered” information that Hamilton had originally considered building his home near the proposed relocation site—a revelation that enhanced a “growing sentiment in New York among thoughtful people” that the Hudson River site provided a more appropriate setting.13

The New York City Landmarks Commission countered that Hamilton Grange could have been a “great asset” to a “renewing” neighborhood that was “entitled” to “special consideration” by preservation planners as a “deprived” area. Restoring the building at the current site would “best satisfy the condition of service to the community” but, given pragmatic considerations, the Grange “could never be much more than it is now.” Thus, it concluded that leaving the building in Harlem “would be rather an insult to the memory of Alexander Hamilton than a tribute.”14 At least one advocate proposed centering the home at its original location within a reconstructed landscape as part of a major urban renewal project in Harlem. Despite some local residents declaring that Hamilton Grange was “ ‘culturally a part of Harlem’ and should remain” in the neighborhood the National Park Service remained committed to the Hudson River property.15

Using descriptive references like “slum” and “Uncle Tom” to describe the condition of the property were thinly veiled references to the African American residents that predominated Harlem’s neighborhoods. Urban unrest in the community, especially the 1964 Harlem riots, added to the bias against keeping the building near its original location. In the end, community efforts were successful in fostering a reconsideration of the site’s removal out of the district, although controversy still remained about its potential in situ revitalization. This led to generation of patchwork restoration, preventive maintenance, and additional planning efforts. In 2008 the building was finally relocated nearby to a more appropriate parcel within the neighborhood, reopening as a museum in 2011.16

Did Ronald Lee and other nationwide preservation leaders recognize the irony of their efforts to remove a nationally significant resource from its historic associations with Harlem, just as the movement was advocating for another expansion of federal recognition programs in the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966? Clearly, some portions of the preservation community thought that Harlem was exactly the wrong place for Hamilton Grange, preferring to reconstruct the estate’s landscape at a new site along the Hudson. Did racial geography deter the New York financial community from contributing toward the preservation of the founding father most associated with the business community? As an agency, the NPS was constrained by the congressional

mandate to move the building, just as the resource was confined to an inadequate site adjacent to St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. Ironically, in 1966 the New York Landmarks Commission asserted within five years the preservation of The Grange would “undoubtedly assume its proper significance” and foster a revival of scholarly works and “a great surge of popular interest” in this somewhat forgotten founding father.17 The prediction was correct, only several decades too soon, as Ron Chernow’s biography was published in 2004 and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical adaptation, Hamilton , opened in 2015 to wide acclaim.

American Landmarks Celebration

Just as the National Park Service was considering the removal of Hamilton Grange out of Harlem in 1964, its parent agency, the Department of the Interior, was sponsoring the “American Landmarks Celebration.” Created in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) it served as the United States’ contribution to the United Nations’ International Monuments Year. President Johnson, invoking the mandate of the 1935 Historic Sites Act, saw the expanding recognition of historic landmarks as arousing an “awareness of the acute need for action to safeguard the richness and diversity of American architectural, historical and natural heritage.”18 Acting as the honorary chair for the celebration, the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, participated in ceremonies designating Woodrow Wilson’s Washington, DC residence as a National Historic Landmark.

African Americans also saw value in such programs and proudly celebrated the entry of Cedar Hill, the Washington, DC home of the prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass as a unit of the National Park System in June 1964. Using the activist language of the time, Charles W. Thomas noted the “acute need for militant action” within “persistently aggressive” communities to protect historic properties against the “virtually irresistible encroachments” of urban renewal and highway expansion. With references to ongoing civil rights struggles, he continued:

Such landmarks must be preserved for the inspiration of future generations of a race that is taking increasing pride in its history and developing commanding leverage in dramatically remolding the present in accord more nearly with what the American ideal was originally intended to be. . . . The American Landmarks Celebration would do well to remind Negroes and whites who have been eye witness to living history, either as active participants in or as interested observers of the epochal social revolution with its exhilarating successes and horrendous tragedies, to single out for appropriate marking and preservation those sites which have memorably involved in the revolution.19

Here the differences in the language were important: LBJ’s view reflected a consensus, status quo ensemble that was distrustful of a changing environment, while the other focused on the social tumult of the time, embracing all types of change, with recognition of its significance.

At the same time, American historic preservation was undergoing a generational shift as the leadership who began service prior to World War II when the museum curator and architect, Fiske Kimball, coined the phrase the “preservation movement.” Leaders like NPS Director Conrad Wirth, Chief Architect Thomas Vint, Architectural Historian Charles Peterson, and Chief Historian Ronald Lee, each with 30-year careers in conservation, were all retired prior to the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act. New leaders, like the architect Ernest Connally, architectural historian William Murtagh, and historian Robert Utley, were central to the implementation of what they called the “New Preservation.” Guided by a variety of charters and conventions, this new cohort would create the criteria and practices that would structure the American preservation movement over the next generation.20

Spirit of an Age

Writing to Robin Winks in 1972, Charles Hosmer, the most prolific historian of the preservation movement, was concerned that his book, The Presence of the Past, had not accurately captured the motivations and context of the early advocates and their accomplishments. And yet Hosmer concluded that the movement’s continuing story was “itself an excellent representation of the spirit of an age.” Considering the course of the historic preservation movement over the quarter-century after the National Historic Preservation Act the New Preservation reflected the spirit of a generation that transformed the conservation of historic places. At points along this timeline advocates and decision-takers stopped to assess the movement—where it had been and where it was going. As noted by Robert Garvey in 1967, “the act of preservation and the product preserved” strongly represented the values that a generation wanted to share with the future—it says as much about the present as it does about the past.21

As the nation approached the Bicentennial of the American Revolution several thoughtful individuals looked at the past, present, and future of the historic preservation movement and its relationship to the new economic, social, and political context that shaped the mid-1970s. Americans, noted Robin Winks, “wish to preserve that which they want to remember,” adding that it was “interesting to look at what is revealed” by these choices. In his analysis of extant National Parks, Memorials, and Historic Landmarks, Winks found the top three categories of protected areas to be American Revolution or Civil War battlefields; sites associated with the shifting frontier of exploration and settlement; and, those connected to business and industry. Historic preservation had “three serious biases”: it trended toward the positive and the progressive aspects of past events; those that influenced

the American experiment in a “visible and dramatic way”; it was bookish, with an overemphasis on literary and artistic endeavors; and, finally it was inherently interested in the visible, tangible remains of the past. “In America,” concluded Winks, “there is a sense of place, of preserving hallowed ground, even though little remains associated with the events that took place there.”22

The general characteristics of the New Preservation are described in Chapter 1, with an emphasis on how the expansion of the National Register of Historic Places to include sites of state and local historical significance transformed the movement. Despite this mandate, the bureaucratic systems of official memory were slow to launch, taking a decade to ensconce many of the administrative criteria and conventions. Indeed, the Bicentennial of the American Revolution also provided the momentum that expanded how many Americans encountered and embraced their heritage—a change that eventually led to an administrative interregnum that was Heritage Conservation, and Recreation Service (HCRS) and the substantive amendments to the National Historic Preservation Act in 1980. As the new perspectives turned 20 during the mid-1980s, there was time for retrospective and paradigm shifts that might address the challenges of the movement’s encounters with the potpourri of multiculturalism.

The strongest commitment to heritage conservation, as described in Chapter 2, comes when a government incorporates a historic property into a system of parks and protected areas. Despite goals of developing a “well rounded system” of historic sites, the era of the New Preservation began with a paucity of properties under federal stewardship that recognized anything beyond the dominance of colonialism, warfare, politics, and wealth. Sites associated with George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington, and Frederick Douglass became the foundation for a cornucopia of new properties stitched into the fabric of National Parks and led to the consideration of a variety of new themes, such as the Underground Railroad, that more completely represented the changing complexion of the country. In addition, as found in Chapter 3, the stories told (and consciously omitted) at these sites of heritage conservation contributed to the mis-education of the American heritage tourist. After the Bicentennial and the phenomena that was Alex Haley’s Roots, a generation of historic site interpretation was forced to confront the absence of enslavement and its aftermath at many properties.

The well-curated story—told in Chapter 4—that historic preservation brought only positive change to older neighborhoods was challenged during the 1970s, when, despite the creation of the economic engine that was the federal rehabilitation tax credit program, many communities were underwent the residential displacement that came to be known in the 1980s as gentrification. Cities and towns across the country faced, as in Alexandria, Virginia, the choice between enhancing their residential tax base by expanding the boundaries of the Old and Historic District and dispossessing a generation of African American residents in the Uptown neighborhood who were caught between rehabilitation and transitsponsored land speculation. The inherent conflict between historic districts and

displacement demonstrated how far segregated sectors of the preservation movement were from the realities of urban America.

Chapter 5 tells the story of how the New Preservation reacted to challenges by African Americans and other minorities to the status quo elitism that, despite changes in the language of official memory, seemed to remain characteristic of the movement. For the generation of practitioners who came of age, or at least got jobs, during the 1970s, there were opportunities to shape new ways of viewing the past, categorizing it, and ensuring its recognition and perhaps conservation. Proposals to modify or adapt the criteria for the National Register languished, despite evidence that some of the administrative conventions discriminated against the recognition of minority-associated properties.

The conclusion to this volume approaches the concept that heritage conservation must be considered within the bundle of civil rights that shape American society and politics. Just as the environmental movement was shaken by the arrival of Environmental Justice, where was the impact of the modern Civil Rights movement on American historic preservation? Clearly, one of the lessons that should have been learned from the racial turmoil of the 1960s was that African American contributions to society had not received full recognition and that Americans writ large “lacked proper perspective in dealing” the complete narrative of their constitutional experiment.23 And yet, in facing a collection of “wicked” problems revealed by its expanding impact on American communities, how did the New Preservation movement address an evolving “catechism of contradictions” regarding its motivations, its philosophy, and its conventions?24

Notes

1 William T. Martin Riches, The Civil Rights Movement: Struggle and Resistance (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997).

2 Robert R. Garvey, Jr., “Genesis: The Creation of the Historic Preservation Act of 1966,” Remembering the Future, Mary Washington College, 1986, pg. 5.

3 Arthur P. Ziegler, Jr., Historic Preservation in Inner City Areas: A Manual of Practice (Pittsburgh: Ober Park Associates, 1974), pg. 31.

4 Robert Kanigel, Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), pp. 221–222.

5 James M. Lindgren, Preserving Historic New England: Preservation, Progressivism, and the Remaking of Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); James M. Lindgren, Preserving the Old Dominion: Historic Preservation and Virginia Traditionalism (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1993).

6 American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, Minutes of Board of Trustees, June 19, 1950 Meeting. NPS Harpers Ferry Center (HFC), Ronald F. Lee Collection (RFL), American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society File.

7 Director, NPS to Legislative Council, Office of the Solicitor, DOI, March 10, 1961. NPS Park History Program (PHP) Hamilton Grange (HAGR) Files. Mrs. W. Randolph Burgess to Sen. Jacob Javits, June 27, 1961. Library of Congress (LOC), David E. Finley (DEF) Collection Box 50. Mrs. Burgess, a great-great granddaughter of Hamilton, was shocked the financial community was not interested in saving the home.

8 William C. Wing, “Alexander Hamilton Home is Fast Falling into Ruin,” New York Herald Tribune, February 7, 1960; William C. Wing, “The House that Hamilton Built,” New York Herald Tribune, February 8, 1960.

9 Other options proposed included moving it 270 miles to Hamilton College in Clinton, New York; and, acknowledging Hamilton’s role as founder of the Coast Guard, floating the building across New York harbor to a facility on Governor’s Island. Andrew G. Feil, Jr., and Lawrence B. Coryell, “Area Investigation Report on the Home of Alexander Hamilton, New York City,” NPS, October 21, 1960, HFC RFL HAGR.

10 “Urge Speedup for Shrine in Harlem,” New Pittsburgh Courier, December 10, 1960.

11 “Week-long ‘Clean-up’ Campaign a Success at Hamilton Grange,” New Pittsburgh Courier, July 11, 1964. Rep. Rangel would later play an important role in the building’s successful relocation within Harlem. Ned Kaufman, Place, Race and Story: Essays on the Past and Future of Historic Preservation (New York: Routledge, 2009), pg. 287.

12 Newton P. Bevin to James Grote Van Derpool, December 4, 1961, HFC RFL HAGR. Regional Director, Northeast Region to Director, NPS, “Hamilton Grange National Memorial,” March 19, 1965. HFC RFL HAGR.

13 James Grote Van Derpool, Executive Director, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission to NPS Regional Director Ronald F. Lee, June 11, 1965. HFC RFL HAGR.

14 New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, “Report on Hamilton Grange,” May 23, 1966. HFC RFL HAGR. Edgar I. Williams to Max O. Urbahn, “Preserving an Historic Shrine: Alexander Hamilton’s Home,” May 9, 1967. HFC RFL HAGR.

15 John C. Devlin, “Action Sought on Hamilton Home,” New York Times, October 26, 1966. LOC DEF Box 51. William S. Rosenberg to Director, NPS, “Hamilton Grange Trip Report,” December 6, 1966. HFC RFL HAGR.

16 Emily M. Bernstein, “Harlem: The Battle to Keep Alexander Hamilton’s Home Where it is,” NYT, November 7, 1993. Hamilton Grange Update, New York Times, November 21, 1993. John H. Sprinkle, Jr., Crafting Preservation Criteria: The National Register of Historic Places and American Historic Preservation (New York: Routledge, 2014), pp. 177–187.

17 New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, “Report on Hamilton Grange,” May 23, 1966, HFC RFL HAGR.

18 President Lyndon B. Johnson, Presidential Proclamation #3618, September 23, 1964.

19 Charles Walker Thomas, “American Landmarks Celebration Seeks to Preserve Nation’s Heritage,” Negro History Bulletin, Vol. 26, No. 1 (October 1964), pp. 23–24.

20 International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter), International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Venice, 1964.

21 Charles Hosmer to Robin Winks, May 30, 1972 UMD CBH. Robert Garvey, “Look Back in Anger?” Preservation News, February 1967.

22 Robin Winks, “Conservation in America: National Character as Revealed by Preservation,” in Jane Fawcett, editor, The Future of the Past: Attitudes to Conservation, 1147–1974 (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1976), pp. 141–149.

23 National Park Service, Feasibility/Suitability Study for a National Museum of Afro-American History and Culture, Wilberforce, Ohio (Denver: National Park Service, 1978). Report prepared at the direction of Public Law 94–518, enacted in 1976. NPS concluded that it was both feasible and suitable to locate the national museum at Wilberforce, Ohio.

24 W.J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2 (June 1973), pp. 155–169. John McWhorter, Woke Racism (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2021), pp. 8–10.

1 THE NEW PRESERVATION

Over the course of 1966, three men—an archaeologist, a historian, and an architectural historian—gathered to devise the organizational structure that would shape the nature of the New Preservation.1 Mandated by the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act the traditional goals and conventions of American historic preservation would be forever transformed with the creation of a three-legged administrative stool comprising the National Register of Historic Places, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, and the State Historic Preservation Offices. The character of official memory was enhanced with the expansion of federal recognition beyond only national significance to include the consideration of places important in state and local history. This chapter charts the course of the first generation of the New Preservation.

American Historic Preservation Before 1966

Charles Hosmer chronicled the history of American historic preservation in three volumes. Published in 1964, The Presence of the Past provides a history of the movement from the 19th century through the first quarter of the 20th century. Comprising almost 1,300 pages within two volumes, Preservation Comes of Age, published in 1981, covered only the second quarter of the 20th century.2 Often overlooked, because of the dominance of the latter work, the first book also provided a snapshot of historic preservation practice in the early 1960s, just prior to the transformation wrought by the enactment of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and the arrival of the New Preservation.3

Through the first quarter of the 20th-century American historic preservation was, according to Hosmer; a grassroots effort, spontaneously growing as an amateur undertaking, without any formal national leadership. Seeking the material

recognition of cultural exceptionalism, it was a uniquely “American response to an American need.” Ironically, given the calculated absence of Native Americans from his narrative, he characterized the activity as an “indigenous movement” as well as a nostalgic and romantic one.4 As with most social movements, American historic preservation practice reflected the cultural, political, demographic, and economic trends across the decades of change that characterized the 20th century. This flexibility was illustrated most succinctly by the changing criteria used to choose which properties to preserve and which to let go as the American landscape was remade by industrialization, suburbanization, and the automobile transportation revolutions.

Prior to the Civil War, the general consensus was that only one property, the Mount Vernon plantation of George and Martha Washington in Virginia, was thought worthy of perpetual preservation. Over the next century, the kinds of places formally enumerated, landmarked with signs, and set aside as house museums grew as Americans expanded the events and personalities that filled their history books. An expanding appreciation for the diversity of properties that illustrated the panorama of the American experience only went so far. For Hosmer, “preservationism [sic] was an Anglo-Saxon movement” that was without any “outspoken nativist declarations.”5 However naive this evaluation of the motivations of early preservationists, the conventions and criteria developed on either side of World War II shaped the nature and number of historic properties handed down from one generation to the next.

Crafting preservation criteria that expanded the definition of what properties might be considered historic and how these places might continue their contribution to a community through adaptive use was a common thread in the third quarter of the 20th century. Managing the plethora of possible historic properties, whether considered important for their historical associations or for their architectural qualities, proved challenging to preservationists, planners, and politicians.

Soon after Fiske Kimball defined “the preservation movement” in 1941, archaeological sites (with their challenging aspects of physical integrity) and examples of exemplary architectural accomplishment (with their potential lack of historical associations) were added to the continuum of cultural resources considered within American historic preservation. Federal mandates, found in the Historic Sites Act of 1935, to identify, evaluate, and recognize nationally significant properties resulted in a series of thematic surveys which were designed to present the full panorama of American history. Initially calculated to march chronologically through American history, with a focus on exploration, settlement, and political and military affairs, by the 1960s the examination on new themes, such as social and humanitarian movements and scientific discoveries and inventions were undertaken in response to Cold War era trends.6

Chronological limitations on what was, and was not, potentially historic were reduced from a century to a so-called 50-year rule. In 1946, when Alexandria,

Virginia, established the third oldest local historic zoning district it adopted a 100-year standard, which evolved into a program where owners of such buildings could volunteer to have their properties included under the regulatory jurisdiction of the city’s architectural review board. Despite concern regarding the potential for controversy in evaluating the national significance of properties associated with the recent past, by the late 1940s, the National Park System Advisory Board and the National Trust for Historic Preservation had both adopted the twogeneration standard as part of their parallel surveys of historic sites.

Administrative constraints associated with the focus on individual buildings within urban environments pushed the National Park Service to finally recognize “historic districts” as a property type in 1965. Facing tremendous threats from federal programs that supported urban renewal, interstate highways, and suburbanization, there was a liberalization in the criteria that found expression in the National Register of Historic Places after 1966.

The traditional patriotic educational goals of American historic preservation were challenged by the social unrest of the 1960s. Advocates for an expanded role for the preservation movement continued to believe that exposure to the authentic places where American history happened could “help to cure some of the social and political ills that were current in the United States.” For many, one function of old places was as a reminder of the hardships endured by past generations combined with a nostalgia for “the peace and harmony of an uncomplicated past.”7

At the same time some critics, railed against commercial exploitation through “historically veneered amusement” and other honky-tonk attractions, suggesting that their presence diminished the role and authority of authentic historic properties. One example was the plight of “John Brown’s Fort,” a building used during the unsuccessful raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in 1859. The building was dismantled and relocated to Chicago as an exhibit for the 1893 World’s Columbian exposition. Afterwards the structure “wandered” for decades until it was reconstructed back in Harpers Ferry on the campus of Storer College in 1909. Extraction of the resource from its original location had cut off its relationship from the historic events, and its use as a for-profit display diminished its true value.8 For many traditionalists, the encroachment of the commercial and honky-tonk in the 1950s and 1960s threatened the perceived authenticity of many places, like Colonial Williamsburg, Mount Vernon, and Gettysburg, conserved as shrines to a glorified vision of American history. These concerns would reappear during the Bicentennial.

Nixon’s Legacy

As with the wider conservation movement, the rise of environmentalism along with the struggle for civil rights hastened the expansion of how preservationists viewed the world. Charles Hosmer described how the practice shifted from concern for the “isolated museum” to a focus on the “total architectural environment”

New Preservation or the “historical landscape.”9 This philosophical realignment was encapsulated within President Nixon’s Executive Order 11593, issued in May 1971 which called for the “enhancement and protection of the cultural environment” and inadvertently fostered the rise of the cultural resource management industry after the Bicentennial.10 Nixon’s impact on the American historic preservation movement was indeed extensive: he laid the foundation for establishing the Historic Preservation Fund, the historic rehabilitation tax credit program, and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the rehabilitation of historic properties. Charles Lee, the South Carolina State Historic Preservation Officer, considered the Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford years “surprisingly progressive,” with increased appropriations, participation by more and more states in the youthful federal partnership; the activation of surveys for National Register properties; and, the implementation of “brick and mortar” preservation projects.11

Still suffering from the fiscal hangover that came with the end of Mission 66, a decade-long billion-dollar investment in the agency that began in the mid1950s, the National Park Service leaders who operationalized the mandate of 1966’s National Historic Preservation Act were constrained by the tradition of park-centered planning.12 Born from a “bewildering array of forces” embracing the social, cultural, and economic reform found in the environmental movement, historic preservation was cast as a new policy that would enhance the quality of the cultural environment.13 This “rehabilitation” of traditional preservation objectives was undertaken despite the acknowledgment that the New Preservation was in many ways a continuation of the goals expressed with the Historic Sites Act of 1935, which helped to establish many of the conventions that were adopted with the expanded National Register. Indeed, the creation of the Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (OAHP), headed by Dr. Ernest Connally, an architectural historian from the Midwest, approached the ideal for a separate historic sites division envisioned in the mid-1930s by the consortium of interests that sponsored the Historic Sites Act. The OAHP: would be the voice of the NPS. The office, however, would not be simply another bureaucratic organization administering a program and dispensing money. The office was to be an “institute” bringing together professionals who would approach all phases of NPS historic preservation according to the highest standards and practices of their respective disciplines. OAHP would be a creative center that would articulate the new preservation philosophy and give guidance and direction to its realization. In its original conception OAHP was to combine the best of academia and public service.14

The goal was twofold: to blend old and new programs into a single organization and to embrace historic properties at the national, state, and local levels of significance, as well as those in public and private ownership. Despite challenges

from park-centric NPS leaders, the OAHP retained its external mission, as set forth in E.O. 11593, to establish preservation practices that could serve as models for other federal agencies, State Historic Preservation Offices, and the stewards of privately held historic properties.

As portions of the United States erupted in violence and turmoil in 1968, the National Trust for Historic Preservation celebrated its 20th anniversary. The 1960s had been a good decade in terms of membership, with an increase of 300 percent to more than 8,500 members. Its new leader, Gordon Gray, a North Carolina native who served as the Secretary of the Army under President Eisenhower, reflected on the changing order, recommending that preservationists “must learn to help shape events not simply by noisy protests, but by submitting constructive alternatives, recognizing that change is with us and progress persists.” No longer could the goal be “simply embalming a building that is dead,” adaptive use was the “surest way of preserving the grace and continuity of urban living.”15 Indeed, that same year Ernest Connally mused that the federal grants to the states, if adequately funded, could foster a “humane form of urban renewal.”16 His colleague, William Murtagh, agreed, asserting that the expanded and authoritative National Register could be “made an instrument of great good.”17

In certain localities, preservationists worked with the then-available toolkit to approach Connally’s and Murtagh’s shared vision. Many urban communities faced Ada Louise Huxtable’s planning paradox, where anything worth doing was worth doing wrong, such that the only way to “really restore” a neighborhood was to “try to replace the poor with a more well-to-do population.” In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Arthur Zeigler and others adopted an alternative approach where the objective was a “decent living environment,” equal access to housing regardless of skin color, and architectural preservation “when appropriate.”18 In the aftermath of urban tumult, sectors of the preservation movement recognized that local governments were at the core of considering the social and cultural values of buildings, streets, neighborhoods, and open spaces.19

The relative modicum of federal funding that directly supported historic preservation activities must be reconciled with the recognition that the rehabilitation of historic neighborhoods caused the displacement of existing residents. Federal, state, and local agencies tried a variety of approaches to reduce the extent of displacement, with programs like the Neighborhood Housing Service (NHS), which was first used in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and widely advocated by the Urban Reinvestment Task Force.20 In the mid-1970 federal agencies still argued that they were not authorized to spend any funds on the maintenance of buildings and structures that no longer met their program needs—a stance that threatened all sorts of resources with demolition by neglect.21 At some agencies, resistance to compliance with procedures designed to implement Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act remained strong.

The leadership of the National Park Service soon recognized that its programs would never have the fiscal support found at the Department of Housing and