Chapter 1

Editor’s Introduction

In 1838 Turner & Hughes, booksellers in Raleigh, North Carolina, offered for sale “an assistant for students in the study of law” called The Tree of Legal Knowledge Presented “in the form of a large map,” the study aid was designed “to impress upon the mind the methodical divisions and subdivisions of Blackstone’s Commentaries, and thus enable the student effectually to master the work and preserve the arrangement as the general guide of his future studies.” Not for law students only, The Tree of Legal Knowledge would also be of use to the practicing attorney “in consolidating his learning and forming an instructive and ornamental appendage to an Office.” And the gentleman, too, “desirous of becoming acquainted with that system of laws, of which ours is principally composed, and which is highly necessary to every Legislator and scholar,” would be “materially benefitted by its use.”1

The prosaic description of the study aid as a “map” hardly does it justice. It is, in fact, a work of art in which the law presented in Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England is depicted as a giant tree with the various legal topics arranged along its branches. The illustrations were accompanied by a text, consisting of the author’s Introduction, general Explanation, and detailed Explanation of the Branches.

The Tree of Legal Knowledge bore a dedication to William Gaston, a prominent lawyer appointed to the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1833, and the imprint of the well-known New York lithographer John Henry Bufford, but its author was identified only as “an attorney at law.” An earlier news story (probably a disguised advertisement) had appealed to state patriotism, emphasizing that “the whole affair is a North-Carolina ‘notion’—being in its inception, design and finish, the production of North-Carolina heads.”2 Explaining that great expense had been incurred in “the procurement of the Engraving” and that “the size of the edition will be regulated entirely by the number of Subscribers,” Turner & Hughes called on “citizens of

1 Raleigh Register , 21 May 1838. Newspapers throughout the state were requested to reprint the advertisement two times “and forward their accounts”.

2 Raleigh Register , 14 May 1838.

© The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2023 J. V. Orth, The Tree of Legal Knowledge, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-8696-3_1

the ‘Old North State’” to support “this ingenious production of one of her sons, a gentleman of the bar.”

For a copy mounted on rollers, the price was eight dollars; bound as an atlas, it went for six dollars; in separate sheets, it cost five dollars—all considerable sums in 1838. To those who could afford it, anything that made Blackstone easier to understand and remember was worth paying for. From the eighteenth to the twentieth century, aspiring lawyers learned their law from Blackstone. In some states, as in North Carolina, Blackstone was required reading for admission to the bar.3

Although The Tree of Legal Knowledge was entirely “a North-Carolina ‘notion,’” it was proudly declared to have been “highly spoken of in New York, where it first appeared.”4 A later advertisement carried impressive endorsements.5 U.S. Attorney General B.F. Butler, who also served as a law professor at New York University, reported that he had examined The Tree “with some care” and found that it “exhibits with great ingenuity and accuracy the methods, divisions, and leading principles of the English Law.” Two members of the Yale law faculty, Professors Samuel J. Hitchcock and David Daggett, who also examined the work, concurred. And U.S. Senator Robert Strange of North Carolina commented that “the ingenuity of the design is not surpassed by its happy execution,” adding that “as a North Carolinian, I am proud of this beautiful effort of genius.” Even Senators Henry Clay and Daniel Webster lent their names, although both candidly admitted to giving The Tree only a cursory examination, Webster modestly adding that “more weight… than is due to my opinion is to be attached to those of Mr. Hitchcock and Chief Justice Daggett, as they are regular and distinguished teachers of the law.”6 Notices appeared in both The New Yorker and The Knickerbocker 7 Later, the Tree was listed among new publications in The North American Review, published in Boston.8

3 See Appendix A, “Blackstone’s Ghost: Law and Legal Education in North Carolina,” for details of the North Carolina requirements.

4 Raleigh Register , 14 May 1838. The Tree of Legal Knowledge was copyrighted in New York under the Copyright Act of 1831, which conferred exclusive rights for twenty-eight years. The Act required that a copy of the work be deposited in a federal district court. Beginning in 1870, copyright registrations and deposits were transferred to the Library of Congress. Neither the District Court for the Southern District of New York nor the Library of Congress presently possesses a copy of The Tree of Legal Knowledge.

5 Raleigh Register , 25 June 1838.

6 Samuel J. Hitchcock, a founder of the Yale Law School, taught from 1824 until his death in 1845. David Daggett, formerly Chief Justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors (1832–34), another founder of the Yale Law School, also began teaching in 1824 and was named Kent Professor of Law in 1826, a post he held until his health forced him to resign in 1848.

7 The New Yorker, vol. V, no. 1 at p. 109 (24 March 1838); The Knickerbocker , vol. XI at p. 473 (May 1838).

8 North American Review, vol. XLVII, no. l00 at p. 266 (July 1838).

Today, the only known copy of The Tree of Legal Knowledge is in the collection of the Boston Athenaeum, which has a set of nine large sheets—a title page, a dedication page, accompanying text,9 and six illustrated plates.10 Five plates, lithographed and hand-colored, illustrate the substance of Blackstone’s Commentaries. The sixth illustrated plate, not colored, depicts “the mixed government of Great Britain” and serves as an “index,” explaining the symbols used to illustrate Blackstone’s treatment of criminal law. The sheets, acquired by the Athenaeum on 11 October 1847, remained unexamined in its collection for over a century and a half.11

1.1 Imagining Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone, who lived from 1723 to 1780, is not particularly hard to imagine. We have several reliable portraits of him—reliable to the extent that society portraitists could provide recognizable images but show at the same time an idealized high court judge12 (see Fig. 1.1). We know him from the records as a punctilious university lecturer, a middling lawyer, an undistinguished Member of Parliament, and an almost equally undistinguished judge.13 Unlike Lord Mansfield, his great contemporary lawyer and judge, Blackstone was never known to “drink champagne with the wits.”14 Dr. Samuel Johnson, also Blackstone’s contemporary, would have described him as distinctly “unclubbable.”15 And Blackstone’s latest biographer admits that he was not always an easy man to get along with.16

Mutatis mutandis, Blackstone was like a great many other eighteenth-century professional gentlemen who aspired to join the country gentry. But to generations of lawyers and judges throughout the common law world Blackstone was not a man, but a book. His four-volume Commentaries on the Laws of England , first published

9 The author’s Introduction and Explanation appear on one large sheet. A contemporary pamphlet, not in the collection of the Boston Athenaeum, reprints the Introduction and Explanation and adds the author’s Explanation of the Branches. A copy of the pamphlet is held in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.

10 The sheets measure 21 9/16 in. (54.8 cm) high by 17 5/16 in. (44 cm) wide. Although now unbound, they were once in a red and dark blue leather binding, probably added by the Athenaeum in the second half of the nineteenth century.

11 The sheets were from the library of Ithiel Town, pioneering architect and civil engineer, who died in New Haven, Connecticut in 1844.

12 For a survey of likeness and images of Blackstone in various media—portraits and engravings; statues and stained glass—see Wilfrid Prest & J.H. Baker, “Iconography,” in Blackstone and His Commentaries: Biography, Law, History (ed. Wilfrid Prest, 2009).

13 See John V. Orth, “Blackstone,” in The Oxford Companion to Legal History 359 (ed. Markus D. Dubber & Christopher Tomlins, 2019).

14 James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. 468 (1791) (Johnson’s comment on Mansfield, paraphrasing a line in Matthew Prior’s poem “The Chameleon”).

15 See Leo Damrosh, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age 126 (2019) (Johnson’s description of Sir John Hawkins, lawyer and author).

16 Wilfrid Prest, William Blackstone: Law and Letters in the Eighteenth Century 310–11 (2008).

1.1 “Sir William Blackstone” by an unknown artist. (Credit © National Portrait Gallery, London)

in 1765 to 1769 and never out of print since, is the single most important book in the history of the common law. In 1779, John Dunning, prominent lawyer and opposition MP, wrote a “Letter to a Law Student,” which was published and achieved widespread

Fig.

1.2ImaginingBlackstone’sCommentaries5

circulation, not just in England.17 Dunning included a helpful list of “books necessary for your personal instruction.” Prominent among them was “Blackstone,” with the admonition: “on the second reading turn to the references.” Elegantly written and bearing all the hallmarks of the Enlightenment, Blackstone’s Commentaries soon formed part of every gentleman’s library, being joined over the next few years by Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) and Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1788), with both of which it could be favorably compared.

1.2 Imagining Blackstone’s Commentaries

As the anonymous author of The Tree of Legal Knowledge explained in his accompanying Introduction, he was convinced that a visual image of the law as presented in the Commentaries would make it easier to remember. “The mind more readily grasps and vividly retains impressions communicated through the sense of perception.” He added that he was inspired to prepare his visualization of the Commentaries by two memorable experiences of his own. He had recently viewed the enormous painting “Christ Rejected” by the prominent English artist Benjamin West, which had toured America in 1830–32,18 and remembered the expressions on the faces in the picture with “a distinctness almost equal to visible objects now formed upon the retina” (see Fig. 1.2). And with a recollection no less distinct he recalled how, poring over an atlas “in early youth,” he had gained “the Geographical knowledge of this world with its mighty oceans, boundless continents, indented bays, and serpentine rivers.”

A similar vision had inspired Blackstone, who described his intention in writing the Commentaries as to provide “a general map of the law, marking out the shape of the country, its connections and boundaries, its greater divisions and principal cities.”19 But Blackstone’s most memorable image of the law was a vivid architectural metaphor:

17 “Copy of a Letter from John Dunning, Esq. to a Gentleman of the Inner Temple; Containing Directions to the Student,” The European Magazine, vol. 19, p. 417 (Jun. 1791) (identifying “Lincoln’s Inn, March 3, 1779” as the original place and date of the letter), reprinted in The Carolina Law Repository, vol. 2, p. 223 (1815).

18 Benjamin West, “Christ Rejected” (1814) (200 × 260 in.). First exhibited in London and seen by 240,000 paying visitors, the painting was shown in various locations on its American tour. See Helmut von Erffa & Allen Staley, The Paintings of Benjamin West 359 (1986). When and where the author of The Tree of Legal Knowledge saw West’s painting is not known. Since 1878 “Christ Rejected” has been in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia. 19 1 Bl. Com. 35. Citations to Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–69) (abbreviated Bl. Com.) are to the Oxford Blackstone, general editor Wilfrid Prest, published in four volumes in 2016. The Oxford Blackstone reprints the text of the first edition of each volume and indicates changes Blackstone made in later editions in a separate section at the back. For more information concerning citation of the Commentaries, see John V. Orth, “‘Catch a Falling Star’: The Bluebook and Citing Blackstone’s Commentaries,” 2020 U. Ill. L. Rev. Online 125 (July 10, 2020).

We inherit an old Gothic castle, erected in the days of chivalry, but fitted up for a modern inhabitant. The moated ramparts, the embattled towers, and the trophied halls, are magnificent and venerable, but useless. The inferior apartments, now converted into rooms of convenience, are chearful [sic] and commodious, though their approaches are winding and difficult.20

Blackstone was well aware that English law changed over time: “the rise, progress, and gradual improvements of the laws of England,” as he described it.21 The renovations to the old Gothic castle indicate as much, but an organic metaphor seems not to have occurred to him. In his earlier Treatise on the Law of Descents, Blackstone had provided a visual aid to understanding English law’s conception of blood relationships, which many legal authors over the centuries illustrated with an arbor consanguinitatis, a “family tree.” But, disappointingly, Blackstone chose instead a Table of Consanguinity, a simple diagram illustrating the “astonishing… number of lineal ancestors which every man has”22 (see Fig. 1.3). When, a century later, a Yale

20 3 Bl. Com. 268. See Prest, Blackstone 67 (“This elaborate architectural-cum-historical metaphor… seems entirely of Blackstone’s own contriving. Nothing quite comparable in scale or specificity of reference appears in the early modern legal canon.”).

21 4 Bl. Com. 400 (title of chapter 33).

22 2 Bl. Com. 203–04.

Fig. 1.2 “Christ Rejected” by Benjamin West. (Credit Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia)

1.2ImaginingBlackstone’sCommentaries7

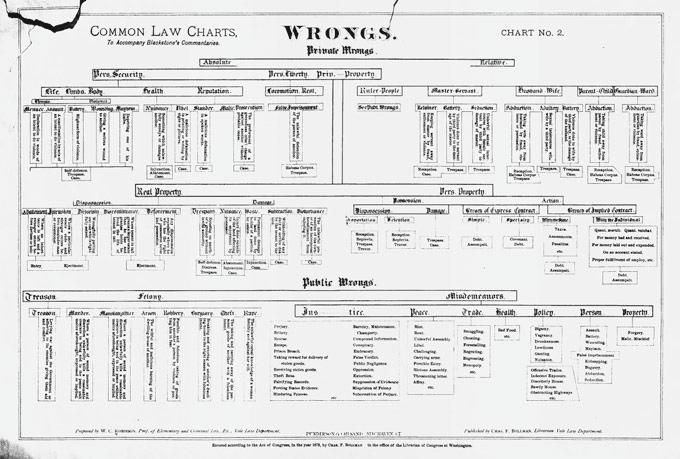

law professor prepared “charts to accompany Blackstone’s Commentaries”for the assistance of his students, they were equally static23 (see Figs. 1.4 and 1.5).

It was the imagination of the anonymous North Carolina “gentleman of the bar” that animated the Commentaries, turning it into a tree, a living metaphor for the growth and development of English law.24 The “life-giving soil” out of which the common law grew was a mixture of natural and revealed law; its roots were customs and ancient rules adopted from Roman and canon law (“general customs,” “particular laws,” and “particular customs”). The role of modern statutes was distinctly secondary, personified as a barefoot “husbandman,” dwarfed beside the enormous tree—an image of which Blackstone, who thought statutes often did more harm than good, would have approved.25

Picturing the common law in this way minimized the role of human agency in its creation. It was a natural growth, with roots deep in reason and revelation. While the details displayed on its spreading branches were the product of human, specifically judicial decisions, they were not the product of one great law-giver but the sum of decisions made over centuries by innumerable, mostly forgotten judges. In consequence, a system of multiple, complex, occasionally astounding rules— illustrated on The Tree and rapidly summarized by the author in his Explanation of the Branches—could be given an air of authority and inevitability. The student’s job was to master its “methodical divisions and subdivisions” and to admire the majestic product of the ages.

Because Blackstone organized all English law under the headings of rights and wrongs,26 allocating two volumes of the Commentaries to each, The Tree of Legal Knowledge has two great branches. Rights are further divided into rights of persons and rights of things, each with its own volume; and wrongs, into private wrongs and public wrongs, each also assigned a volume. Accordingly, as imagined by the anonymous attorney, The Tree’s two great branches divide in two, each with many smaller branches.

The author’s accompanying Explanation of the Branches describes the labels attached to each branch and twig, but several remarkable facts about The Tree of

23 William C. Robinson, Common Law Charts to Accompany Blackstone’s Commentaries (1872).

24 It is difficult not to be reminded of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Garden of Paradise. See Gen. 2:9.

25 See 1 Bl. Com. 70 (“It hath been an antient [sic] observation in the laws of England, that whenever a standing rule of law, of which the reason perhaps could not be remembered or discerned, hath been wantonly broke in upon by statutes or new resolutions, the wisdom of the rule hath in the end appeared from the inconveniences that have followed the innovation.”).

26 Blackstone’s division of English law into rules concerning rights and rules concerning wrongs was suggested by his definition of law as “a rule of civil conduct prescribed by the supreme power in a state, commanding what is right and prohibiting what is wrong.” 1 Bl. Com. 44. Hardly original, this definition of law goes back at least as far as Cicero in the first century B.C. See Cicero, 11 Philippics 12 (sanctio justa, jubens honesta, et prohibens contraria) (“a just ordinance, commanding what is right and prohibiting the contrary”), cited at 1 Bl. Com. 118.

1.3 Blackstone’s Table of Consanguinity. (Credit Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School)

Fig.

Fig. 1.4 Charts to accompany Blackstone’s Commentaries: Rights. (Credit Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School)

Fig. 1.5 Charts to Accompany Blackstone’s Commentaries: Wrongs. (Credit Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School)

Legal Knowledge should be noted. First, The Tree depicts the law exactly as described by Blackstone seventy years earlier, including the traditional rights of the monarch, the aristocracy, and the Church, which are elaborately and artistically illustrated. It is notorious that Blackstone had little to say about the law of contract, which had developed rapidly in the years after he published. Consequently, that increasingly important body of law barely appears on The Tree of Legal Knowledge

On both sides of the Atlantic, scholarly lawyers had been busily producing annotated editions of Blackstone’s Commentaries. But by the 1830s, judicial decisions and statutes in England had rendered so much of it out of date that annotated editions could not keep up. Even as the North Carolina lawyer was painstakingly illustrating the Commentaries of many years ago, Henry John Stephen in England was at work on his four-volume New Commentaries on the Laws of England (Partly Founded on Blackstone) that appeared in 1841 and held the field through twenty editions until 1950.

More remarkable than the absence of contemporary English law on The Tree is the absence of American law, despite the fact that as early as 1803 legal scholar St. George Tucker had published an Americanized Commentaries, complete with notes on the U.S. Constitution and laws.27 By contrast, the “Constitution” that appears on the branch of The Tree of Legal Knowledge devoted to the rights of persons, is the unwritten English Constitution of the eighteenth century.28 Rather than the American Bill of Rights, The Tree sports a banner held by an eagle blazoned with Blackstone’s list of five auxiliary rights that protect the three great rights of life, liberty, and property: first, “The Constitution and privileges of Parliament”; second, “The restraints imposed on the King’s Prerogative”; third, “The right of applying to Courts of Justice for redress”; fourth, “The right of petitioning the King”; and fifth, “The right of having arms for self defence.”29

Although Blackstone’s Commentaries outlived its usefulness in England, in America it continued to thrive. There was no national legislature in the new federal republic with authority to undertake wholesale legal reform. Each state was left to develop the law for itself, and state legislatures generally deferred to the courts,

27 St. George Tucker, Blackstone’s Commentaries: with Notes of Reference to the Constitution and Laws, of the Federal Government of the United States, and of the Commonwealth of Virginia (5 vols., 1803). Tucker was Professor of Law and Police at the College of William and Mary from 1790 to 1804.

28 The English Constitution is still “unwritten.” In 2019 it was described by Britain’s highest court as a collection of “common law, statutes, conventions and practices.” See R. (on the application of Miller) v. The Prime Minister, [2019] UKSC 41.

29 1 Bl. Com. 136–39. The fifth auxiliary right—the right of having arms for self-defense—is of obvious significance in the current debate about the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.” See New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn. v. Bruen, 2022 WL 2,251,305, 142 S.Ct. 2111, 2177 (U.S. 2022) (Breyer, J., dissenting.).

1.3“PublishedbyTurnerandHughes”11

where Blackstone was long accepted as unquestioned authority. Perhaps the classbased English law of the eighteenth century particularly suited conditions in North Carolina and other Southern states with their hierarchical social structures and large enslaved populations. Because slavery found no place in Blackstone’s Commentaries,30 there was no need for the author to find a place for it on The Tree of Legal Knowledge

The Tree’s author did make one curious change, not to Blackstone’s statement of the law, but to his presentation of it. Blackstone began with rights, then turned to wrongs. So readers of the Commentaries would encounter the law in this order: rights of persons, rights of things, private wrongs, public wrongs. But viewers of The Tree of Legal Knowledge, if scanning from left to right, would see the branches in the reverse order: public wrongs, private wrongs, rights of things, rights of persons. The change was quite intentional. The rights of persons, the author explained, constitute “the first or right branch of this tree,” and public wrongs or crimes “the last or left branch.” So the author agreed with Blackstone’s priorities, but “read” The Tree from right to left. Whether or not this interfered with the goal of assisting a student to remember the arrangement of the Commentaries, it did have the effect of putting the law of public wrongs on the left, or sinister, side of The Tree.

1.3 “Published by Turner and Hughes”

Henry D. Turner and Nelson B. Hughes, publishers of The Tree of Legal Knowledge, were proprietors of the North Carolina Bookstore located at the corner of Fayetteville and Morgan Streets in central Raleigh, across from the imposing Greek Revival capitol building then under construction. Their store so impressed a visitor from Richmond in 1834, who had not expected to find so much “literary taste” in the rural state, that he wrote a glowing description on his return home.31 “The store of Messrs. Turner and Hughes… not only offers a very large collection of books, but is fitted up so handsomely, and with so many inducements to attract the curious, that it is crowded at every hour of the day with those who come to pass an hour in the pleasantest lounge that can be imagined.” The store stocked “every newly published work, a great variety of literary periodicals, the daily papers, [and] portfolios of

30 “Pure and proper slavery does not, nay cannot, subsist in England; such I mean, whereby an absolute and unlimited power is given to the master over the life and fortune of the slave.” 1 Bl. Com. 411. In fact, as every North Carolinian in 1838 was well aware, slavery certainly did subsist in North Carolina, and only a few years earlier, the state Supreme Court had held that the master’s power over the slave was indeed absolute and unlimited. State v. Mann, 13 N.C. (2 Dev.) 263 (1829) (“The power of the master must be absolute to render the submission of the slave perfect.”). See John V. Orth, “When Analogy Fails: The Common Law and State v. Mann,” 87 N.C.L.Rev. 979 (2009).

31 Farmers’ Register (Richmond, Va.), 26 Nov. 1834.

prints.” In 1838 Turner & Hughes boasted that they had on hand all the law books necessary for a “COMPLETE LAW LIBRARY.”32 So successful was the North Carolina Bookstore that in 1841 the firm opened a branch in New York under the charge of the enterprising Mr. Turner.33

In connection with their Raleigh store, Turner & Hughes established a printing and binding department, “probably the first of any dimensions in the State,”34 producing a variety of titles. In 1837 they secured the contract with the state to publish and market the two-volume Revised Statutes of North Carolina, which went on sale (for nine dollars) in the same year as The Tree of Legal Knowledge 35 Over the following years, the firm specialized in publishing legal materials, particularly volumes of North Carolina law reports.36 In addition, they produced Turner & Hughes’s North Carolina Almanac, “one of the most widely circulated almanacs of the ante-bellum period.”37

After Turner and Hughes dissolved their partnership in 1846, Turner continued as sole proprietor of the North Carolina Bookstore. He devised a notable “system of conveying books over the State by means of wagons specially adapted to the purpose,” which “made regular visits to the University at Chapel Hill and other schools in the State, as well as bringing stock from distant markets to the city.”38 The almanac continued to appear, now under the title Turner’s North Carolina Almanac. When Turner died in 1866, James H. Enniss took over publication of the almanac, continuing to use Turner’s name, although in 1907 Pinckney C. Enniss, the son of James H. Enniss, renamed it the Turner-Enniss North Carolina Almanac and produced it until 1915.

32 Raleigh Register , 30 April 1838.

33 Turner announced in the New York press that in addition to stocking “every variety of Books, Stationery, etc.,” he continued “to act as Principal Agent for the sale of Beckwith’s Anti-Dyspeptic Pills.” Bentley’s Miscellany (American ed.), vol. 8, issue 2 (1 Aug. 1841). The advertisement included a testimonial to the effectiveness of the pills from Beverly Tucker, a law professor at the College of William and Mary, and the son of St. George Tucker, who had produced the Americanized edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries in 1803.

34 Guion Griffis Johnson, Ante-Bellum North Carolina: A Social History 811 (1937).

35 Although published by Turner & Hughes, the Revised Statutes were printed by Tuttle, Bennet, and Chisholm in Boston, leading to criticism in the Raleigh Register , 23 Dec. 1837. Volume two of the Revised Statutes included, in addition to the North Carolina statutes, several important English documents, including Magna Carta. See John V. Orth, “The Past Is Never Dead: Magna Carta in North Carolina,” 94 N.C. L. Rev. 1635 (2016).

36 E.g., Iredell’s North Carolina Reports (1841); Martin’s North Carolina Reports (1843); Battle’s North Carolina Reports (1844); Taylor’s North Carolina Reports (1844).

37 Johnson, Ante-Bellum North Carolina 811.

38 Moses Neal Amis, Historical Raleigh: With Sketches of Wake County (from 1771) 76 (1913).

1.4 Dedicated to William Gaston

In an elaborate full-page dedication, the unnamed author of The Tree of Legal Knowledge “respectfully inscribed” his work to William Gaston, recently appointed to the North Carolina Supreme Court.39 A well-regarded lawyer and successful politician, Gaston had served in both the North Carolina Senate and House of Commons, as well as in the United States House of Representatives. In the state Senate in 1818 he had chaired the joint legislative committee that framed the act creating the three-member Supreme Court, the state’s first purely appellate judicial body.40

Gaston’s appointment to the Court in 1833 attracted considerable attention and some controversy, not because of any lack of qualification, but because he was a prominent Roman Catholic41 in a state with a constitutional ban on office holding by any person “who shall deny… the truth of the Protestant religion.”42 At a convention called in 1835 to amend the state constitution, Gaston ingeniously justified taking office by arguing that as a Catholic he did not deny the truth of the Protestant religion. “There is no affirmative doctrine embraced by Protestants generally, which is not religiously professed also by Catholics,” he said. “The latter hold that the former err, not in what they believe, but in what they disbelieve.”43 Gaston led the fight to end the religious test for office altogether, delivering an eloquent two-day oration on the subject, but succeeded only in having the word “Christian” substituted for the word “Protestant” in the amendment that was subsequently sent to the voters and adopted.44

1.5 Lithographed by J. H. Bufford

In the small print at the foot of the dedication page, appears the legend “J.H. Buffords Lithog’y 136, Nassau-st N.Y.” Although The Tree of Legal Knowledge had been advertised as an “Engraving,” which meant printed from a design etched on a metal

39 Under the North Carolina Constitution of 1776, judges were appointed by joint ballot of both houses of the General Assembly. N.C. Const. of 1776, Sect. XIII.

40 1818 Laws of N.C. 3. Prior to the creation of the Supreme Court, appeals were heard by the Court of Conference, composed of trial judges.

41 Daniel Hutchinson, “Roman Catholics,” in Religious Traditions of North Carolina 266, 268 (ed. W. Glenn Jonas, Jr., 2018). See Barbara A. Jackson, “Called to Duty: Justice William J. Gaston,” 94 N.C.L.Rev. 2051 (2016), in which Jackson, then herself a justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, argued that Gaston’s religion influenced his judicial decisions, particularly his decisions in cases involving slaves.

42 N.C. Const. of 1776, Sect. XXXII.

43 Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of North Carolina 268 (1836).

44 Amend. 1835, art. IV, § 2.

plate, it was in fact a lithograph, printed from drawing a waxy image on porous limestone. John Henry Bufford was a pioneer of the technique and his reputation at the time rivaled that of his contemporary lithographer Nathaniel Currier, who later joined with James Merritt Ives to form the enormously successful firm of Currier & Ives. Although Bufford had been trained in Boston and after 1840 located his lithography business there, for the last half of the 1830s he operated his shop in New York.45

While Bufford was himself a competent artist, he most often worked from designs supplied by others. Since The Tree was emphatically claimed to be entirely “a NorthCarolina ‘notion’—being in its inception, design and finish, the production of NorthCarolina heads,” it appears that it was the anonymous lawyer who was responsible for the illustrations.

1.6 Imagining the Anonymous Author

Published by Turner & Hughes, dedicated to William Gaston, lithographed by J.H. Bufford, The Tree of Legal Knowledge was authored by an unnamed “attorney at law.” There were few clues to his identity. He was a North Carolinian. He had been raised in a home with books, having studied an atlas “in early youth.” He was an art lover, having seized the opportunity of its American tour to view Benjamin West’s masterpiece, “Christ Rejected.” From The Tree itself one could see that he had artistic talent. And it was obvious from his detailed Explanation of the Branches that he had studied Blackstone’s Commentaries intensively, even obsessively.

He was also well read in serious, if somewhat somber, literature. In his general Explanation he quoted (without attribution) lines from Edward Young’s poem “The Complaint, or Night Thoughts on Life, Death and Immortality” (1742) and from the more recent cautionary long poem The Course of Time (1827) by Robert Pollok. On The Tree itself, he attached a cartouche to a branch of the Rights of Things containing images of a sheep, bee, and goose with the words “The Sheep, the Goose, the Bee/Govern the World these Three/Parchment, Pens, and Wax”—apparently a reference to a poem by William Winstanley (1733), ending “For Deeds, or Dead Men’s Wills.”

After its publication in 1838 The Tree of Legal Knowledge disappeared from North Carolina sources. Finally, almost fifty years later, it was mentioned in the Tarboro Southerner, the local newspaper of the county seat of Edgecombe County in Eastern North Carolina:

TREE OF LEGAL KNOWLEDGE. – Perhaps it is not generally known that Mr. Ben Lavender, the father of Mrs. H.D. Teel, of Tarboro, is the author of the perfect “Tree of Legal Knowledge.” It is only a few of the old lawyers, who have it. We only know of one,

45 See David Tatum, “John Henry Bufford, American Lithographer,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, vol. 86, part 1 (April 1976).

that being in the office of the late Judge Battle. Information as to who has another will be gratefully received by the editor.46

A few months later, the same paper published the obituary of Agnes Helena Teel, who had died of typhoid fever at the seaside in Beaufort, North Carolina, where she had gone in hopes of recovery.47 Born in 1832, she had been educated in Emmittsburg, Md., a center of American Catholicism.48 Most of her obituary was devoted to her religion. “She has lived a constant, practical Roman Catholic lady in this, one of the most enlightened and refined Protestant communities,” where she was “esteemed and beloved by all.” She died “fortified by the sacraments” of “our blessed mother, the Church.” Her remains were brought home to Tarboro by her “bereft husband” Henry Dockery Teel and the Rev. J.J. Reilly and temporarily interred before being moved to “the consecrated cemetery of her ancestry” in Washington, North Carolina.49

Twenty years later The Tree of Legal Knowledge was mentioned once again in the press. In 1900 the Raleigh Times carried the following report:

Mr. P.C. Enniss has found two copies of a rare work by a North Carolinian named Lavinder [sic], dedicated to Judge Gaston. It is entitled “The Tree of Legal Knowledge,” and is an analysis of Blackstone with a fine introduction.50

Pinckney C. Enniss had succeeded his father as publisher of Turner’s North Carolina Almanac, and this connection to Henry Turner may explain his knowledge of the existence of The Tree of Legal Knowledge and of the name, if somewhat garbled, of its author.

46 Tarboro Southerner, 20 May 1880. William Horn Battle, a native of Edgecombe County, who had died in 1879, taught law at the University of North Carolina from 1845 to 1866 and was a justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court from 1852 to 1867.

47 Tarboro Southerner, 23 Sept. 1880. Mrs. Teel had contracted the disease “about three months” earlier.

48 Agnes H. Lavender’s name appears on the roster of St. Joseph’s Academy in Emmittsburg, Md. for the years 1842 and 1843. See Provincial Archives of the Daughters of Charity. St. Joseph’s Academy, the first free parochial school for Catholic girls in America, had been founded in 1810 by Elizabeth Ann Seton (later known as Mother Seton and canonized in 1975). Mother Seton founded the Sisters of Charity in the United States in 1809. The Sisters of Charity joined the Company of the Daughters of Charity in 1850.

49 “As the early nineteenth century progressed, small Catholic congregations emerged in Washington, Wilmington, Fayetteville, and Raleigh.” Hutchinson, Religious Traditions 268. The diocese of Charleston, S.C., encompassing North and South Carolina and Georgia, was established in 1820, and in 1868 a separate Apostolic Vicariate of North Carolina was created. The 1890 U.S. Census of Religious Bodies, the first to count church members, reported 2,640 Catholics in North Carolina out of a population of 1,617,949.

50 Raleigh Times, 16 June 1900.