Discovering Diverse Content Through Random Scribd Documents

The stem is withdrawn while the finger fixes the tube. (Lejars.)

Standing in front of the patient the operator identifies the tip of the epiglottis with the forefinger of the left hand in the pharynx, this finger being used at the same time to raise and fix the epiglottis and also to serve as a guide to the tip of the tube, which is passed downward alongside it, by a maneuver similar to that by which the laryngoscopic mirror is used in the pharynx (Fig. 487). When the tip of the tube reaches the location behind the epiglottis the finger may be passed a little farther downward, plugging the entrance to the esophagus, while at the same time the handle of the instrument is so manipulated as to bring the tube forward. With gentle movement in the right direction it passes into the larynx (Fig. 488). It is then pressed downward until the flanged upper end has passed the epiglottis, after which the tube is disengaged, the handle and the obturator withdrawn, and the upper end of the tube pressed gently into place by the finger which still rests in the pharynx (Figs. 488,

489 and 490). During the manipulation there is almost complete obstruction of the glottis for two or three seconds. The effort, therefore, should be to shorten the procedure, and at no time should it occupy more than two or three seconds. If the landmarks are not easily recognized, and the tube is not placed at the expiration of three seconds, the operator should discontinue for a few more seconds in order that a few inspirations may be taken, after which he should try again.

The finger pushes the tube into place (Lejars )

Withdrawal of the thread. (Lejars.)

When the tube is in place there will come ease of respiration, at the same time violent coughing efforts, because of the irritation thus suddenly produced. So soon as it is apparent, both to the finger in the pharynx and from the relief of obstructive symptoms, that the tube is in its proper place, the finger may be once more passed into the pharynx, the tube pressed down, while the silk thread is withdrawn, since it is not intended to leave it for more than the time necessary to be assured that the tube will not have at once to come out again (Fig. 491). Before removing the thread the gag should be removed for a few moments, so that the effect of the excitement may

pass, after which it may be re-introduced for the purpose of withdrawing the thread.

The procedure is by no means a simple nor necessarily easy one, and it should be practised with the instruments upon the cadaver before resorting to it on the living child.

The tube being placed it will remain to be decided by the subsequent course of events how long it should be allowed to remain—in some cases a few hours, in others a few days. With young children it should remain for at least a week. The time having arrived for its removal, the procedure is similar to that required for its introduction. The assistants hold the child in the same position as before, while the operator substitutes the extractor, guiding its tip again by the sense of touch along the left index finger, which, passed down into the pharynx, is made to discover and identify the upper end of the metallic tube. So soon as the point of the extractor is engaged within the tube the blades are separated and it is then drawn out, while the finger is withdrawn along with it in order to make its removal easier and to prevent its loss should it slip off the instrument. Unless the patient struggles violently the whole procedure should be conducted so as to scarcely cause the slightest staining of the expectoration with blood.

Various causes may require abrupt removal of the tube. Thus it is possible for its caliber to be become occluded with tenacious secretion. This may produce a violent fit of coughing, during which there may occur spontaneous expulsion of the tube. At any time, when it is seen that asphyxia is increasing, or when violence of respiratory effort would indicate obstruction within the tube, it should be removed, cleaned, and re-introduced. After its introduction and removal the operator should remain within easy reach for a short time, to be sure that no unpleasant effects result and that no reintroduction may be suddenly required. Should obstructive efforts occur the child should be held head downward and be slapped vigorously upon the chest. This may loosen membrane or it may permit dislodgement of the tube and its spontaneous expulsion. The latter may also occur during the act of vomiting.

The above description is meant especially to apply to intubation as performed upon young children for the relief of the laryngeal

obstruction consequent upon diphtheria. It has given better results than tracheotomy, which was the only resort previous to O’Dwyer’s device. It is usually performed easily, and is devoid of the horrors frequently attendant upon an emergency tracheotomy. But intubation is not necessarily limited to children nor to cases of diphtheria. The emplacement of such a tube may be called for at any time in cases of threatening or actual edema of the glottis, as, for instance, from inhalation of steam or flame. It may be advisable in other forms of intralaryngeal disease, both acute and chronic, while individuals suffering from laryngeal stricture or stenosis find that they can wear an O’Dwyer tube almost constantly, not only with relief, but that they are thereby saved from the more serious measure of opening the trachea or removing the larynx.

Impending suffocation having been relieved by intubation, the question of feeding arises. The principal disadvantage attendant upon the use of the tube is partial or complete inability to swallow, for the epiglottis does not always easily close over the tube and prevent entrance of fluid into the larynx. It is necessary to feed patients, especially the young, with extreme care. For this purpose there is no food better than ice-cream, while little children should be placed upon their backs, with the head lower than the body, and made to swallow in this position, at least until they have been accustomed to the presence of the tube and instinctively learn how to avoid irritation by involuntary regulation of the act of swallowing.

C

H A P T E R X L I I . THE NECK.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES OF THE NECK.

These consist largely of defects due to arrest of development along the lines of the branchial clefts. Necessarily of embryonic origin, they do not reveal this until varying periods after birth, sometimes not until old age. They consist of fistulas, opening either externally or internally, or more commonly of cystic dilatations of the interior portions of the original fissures. External openings are usually seen along the sternomastoid, either in front or back of it, or between the larynx and the clavicle. Vestiges are also present in the shape of little tags of skin containing portions of cartilage or bone. They frequently occur together, the tag indicating the location of the fistula, whose opening may be found obstructed with crusts. Internally the openings are usually found in the pharynx, perhaps in the larynx or trachea, generally near the tonsil and base of the tongue. An external fistula may be tested for its completeness by injecting a colored fluid and inspecting the pharynx. The fistulous portion is usually marked by a cord-like mass which extends inward, usually toward the hyoid bone. Internal blind fistulas may gradually expand and constitute one variety of the so-called pulsion diverticula of the pharynx and upper esophagus, their dilatation being due to accumulation of food, and gradual stretching in this way.

All of these embryonic relics are of interest because from their small beginnings large growths may take place, constituting even serious surgical problems. These growths may present in almost any region of the neck and frequently extend into the mouth, where they give rise to certain forms of ranula Almost every cystic tumor beneath the tongue or jaw is open to the suspicion of having an embryonic origin. Most of these vestiges are amenable to surgical treatment should they give rise to discomfort or trouble. The operations required are sometimes quite extensive, as any tumors of

branchiogenic origin are especially liable to adhesions to the large vessels; moreover, they are nearly always firm and the dissection thus made difficult. A dermoid cyst may be evacuated and its wall or sac destroyed or dissected out. It may then be made to heal by packing.

Treatment.

—In the treatment of fistulas of the neck, König has advised that a curved probe be passed through the tract to a point close to the tonsil, at which point on the inside of the mouth or pharynx the mucous membrane is incised, a silk thread is fastened to the end of the probe, pulled out with it, then made to pass to the external end of the fistulous tube, which is then invaginated and pulled back into the mouth, where it is reduced to a short stump which is fastened to the margins of the opening of the mucous membrane. The external wound is then made to heal as usual. This treatment suffices for blind internal fistulas of the cervical region.

It is a matter of great surgical importance and interest that certain branchiogenic remnants persist in a perfectly harmless manner until advanced life is reached, after which there take place therein cancerous changes which convert them into the so-called cancers of branchiogenic origin. These are too often of hopeless character by the time they are seen by the surgeon.

Other congenital defects consist of atrophies, such, for instance, atrophy of the sternomastoid muscle, or of certain hypertrophies which may be unilateral or symmetrical.

WOUNDS AND INJURIES OF THE NECK.

The neck is everywhere exposed to incised and perforating wounds, partly as the result of pure accident, too often as the result of homicidal efforts. The most exposed parts are supplied with veins of large caliber which connect directly with the heart, and whatever danger there may be of entrance of air into the veins, under any circumstances, is in this region enhanced. This entrance of air has been regarded as a serious and often fatal accident. The writer’s experience and research have shown that it may often occur in mild degree with but little temporary disturbance. Should it occur the fact

will be indicated by a slight gurgling sound, with tumultuous action of the heart, dilatation of the pupils, embarrassed breathing, and every indication of lowered blood pressure. Every competent operator will secure these large veins before dividing them, but if anything of this kind should be noted during an operation, pressure or plugging of the wound, with artificial respiration, perhaps even massage of the heart, and tracheotomy if necessary, should be practised until the patient has revived. If in the course of an exceedingly deep dissection the accident can be foreseen it may be avoided by keeping the wound filled with warm sterilized salt solution. This, however, will seriously embarrass the operative work, as it obscures vision.

The lower in the neck a serious wound be received, other things being equal, the more dangerous it becomes. Thus penetrating wounds above the larynx are of less importance than those below it. All injuries or wounds about the larynx are not only likely to dislodge its interior cartilages, but are especially likely to be followed by pressure of effused blood, or the consequences of a rapid edema of the glottis, which may prove fatal unless the trachea be opened below. It is this fact which makes fracture of the larynx so dangerous an injury.

A wound of the trachea rarely occurs by itself, as it lies deeply, and it may be especially serious if vessels in this neighborhood have been so injured that blood may be easily poured or escape into the lungs. If the trachea be completely divided its ends will be separated and gap, while the lower end will be drawn out with each deep inspiration. In this way suffocation may quickly occur. In all such cases the head should be placed lower than the body (Rose’s position), the lungs emptied completely, the wound enlarged, and the tracheal wound be sutured or else a tube be inserted. The treatment must largely depend upon the number of hours which have elapsed since its infliction, and the condition of the wound itself. In these cases it may be assumed that such a wound is infected, therefore it should not be closed without provision for drainage.

Any injury to the respiratory tract proper will be indicated by the character of the expectoration and the sounds heard on auscultation. Such injuries are likely to be complicated by a subsequent bronchitis,

pneumonia, deep abscess, or various other undesirable sequences. Under the suggestive term “Schluck-pneumonie” the Germans have described a condition which we describe in the term “inhalation pneumonia.” It implies a septic type of pneumonia caused by the passage downward of foreign material, including septic wound secretions, which, not being expelled promptly, cause a type of inflammation, with consolidation, which will give most of the ordinary physical signs of pneumonia.

A rather distinct type of incised wound is that included in the term “cut-throat.” It implies a homicidal, usually suicidal, attempt on the part of the ignorant to sever the large vessels in the neck. This is but rarely accomplished, the injury being done to the larynx and the trachea and the tissues anterior to the vascular trunks. Usually inflicted with the right hand, one side of the wound may be deeper than the other. While the trachea is usually cut and often divided, the injury may be to the larynx instead. At all events, a wide gash is made and there is considerable hemorrhage, the external jugulars being nearly always severed. By the time such a wound is seen by the surgeon it is an infected wound and it should not be closed too tightly. The trachea may be sutured by itself, but it will be best to place therein a tracheal tube. Ample provision should also be made for drainage. In some instances the wound may be left open, at least for a few days, until it is granulating, and then be closed by deep sutures. Care should always be given to those of desperate suicidal intent and to the maniacal, that they do not reopen the wound in continuation of their previous efforts. This requires careful watching.

Rupture of the trachea, either due to violent coughing or straining efforts or to external violence, is known. It will call for tracheotomy, because of the emphysema which will ensue. Penetrating wounds of the large arteries and veins are always serious. When not extensive they may be followed by diffuse or circumscribed hematoma or by aneurysm. Nélaton is reported to have stated that it takes four minutes for a man to bleed to death from the carotid artery, and that two minutes should suffice for its ligation. Any injury to the vessels should be followed by their exposure, and probably by ligation or suture, in order to prevent the conditions above mentioned. If the wound be low in the neck it would be proper to remove the upper

end of the sternum or to divide the sternomastoid sufficiently to expose it.

The vertebral artery is occasionally injured, mostly in the osseous canal through which it passes. At the base of the neck a wound at or near its origin is an exceedingly serious injury. The same rules apply as above.

Wounds of the large veins are supposed to be of a more serious nature because of the possibility of inspiration of air, i. e., air embolism. These vessels are occasionally injured during removal of deep-seated and adherent tumors. It has been possible in some instances to make a lateral suture of the jugular vein at the point of injury, providing this be not too extensive. Effort at reunion of this kind is always legitimate if the operator feel himself equal to the task. The jugular vein is also occasionally exposed and tied low down, then opened above the ligature, for the purpose of cleaning out its upper portion when filled with infective thrombi, a condition occasionally seen with mastoid abscess, etc. To open it before tying would be a surgical mistake. By this process it is practically obliterated as recovery ensues.

If such a muscle as the sternomastoid be partially or completely divided muscle suture should be practised and the head and neck kept at rest for the ensuing few days.

Injuries to the cervical nerves may be followed by peculiar and interesting features. That of the recurrent laryngeal will cause paralysis of the laryngeal muscles on one side, with consequent difficulty in speech; injury to the cervical sympathetic will be followed by dilatation of the pupils and protrusion of the eyeballs with flushing; of the spinal accessory, by mastoid and trapezius paralysis; of the phrenic, by paralysis of the diaphragm on one side; and of the pneumogastric, by embarrassment of respiration, with pupillary and abdominal symptoms, which are variable. Of all of these injuries that to the phrenic is probably the most serious. Some years ago I tabulated the then recorded cases of injury to the pneumogastric and was able to show that only about 50 per cent. of such cases were immediately or tardily fatal. The phrenic nerve is then the only one within the neck which can scarcely be spared. Any of these nerves

when divided should be reunited by sutures, as elsewhere described.

When any portion of the brachial plexus has been injured a corresponding paralysis of the arm will follow. Wounds of these nerves should be sutured at once. A distinction should be made in all cases between hysterical anesthesia, malingering, and the actual paralysis of injury. Sometimes the amount of callus thrown out after a fracture of the clavicle will include a nerve of sufficient size to produce a neurosis, usually neuralgia, or possibly a paralysis. Excessive callus, or, in effect, the bony tumor which is thus produced, may be removed by operation, and any entangled nerve should be hunted out and liberated.

Pressure of a tumor upon a nerve will cause paralysis corresponding to its degree. When this comes on gradually, even though it involve the phrenic nerve, the consequences are not so serious. Repeated irritation or pressure may cause paralysis, as in the cases of the strap of letter-carriers or those who carry burdens slung from the neck.

Injuries occur to the cervical muscles during parturition and a hematoma of the sternomastoid in the newborn is described. The muscle is contracted and the head bent over. It usually disappears by resolution within a short time. This muscle is also ruptured by violence in the adult; again, hematoma is the result, with at least temporary torticollis, pain, and tenderness. When an abrupt division can be recognized, exposure of the ends and muscle suture would be indicated. At any time, in the presence of clot, it would be proper to cut down and turn it out.

Syphilitic myositis is often seen in the sternomastoid, where it may affect the entire muscle, transforming it into a cord-like mass, or where it may occur as gummatous infiltration. These cases occur without pain and without known cause save the disease itself, whose possibility should be established by the history of the case. Again, these muscles are sometimes contracted because of reflex excitement from adjoining inflammatory foci. Such an affection subsides shortly after due attention to the exciting cause, unless it has been allowed to continue too long. Inflammation, even of the

destructive type, may be propagated to the muscles by continuity from a neighboring suppurating focus.

Serious phlegmons of the neck may be followed by phlebitis of the internal jugular vein, which may be recognized by the presence of a palpable cord-like clot within its lumen. Such a condition is serious because of the ease with which pyemia may ensue. It would be better to expose the vein, to tie it low down, to freely excise and turn out such a clot, than to leave it to create serious disturbance a little later.

Of the posterior portions of the neck we have fewer injuries, and these less serious, excepting those by which the vertebral column or the enclosed spinal cord are injured. These injuries have been referred to in the chapter on the Spine. A high perforating injury of the cord, especially if it involve the medulla, is promptly fatal. Infanticide has been produced by a long needle driven between the occiput and the vertebræ, corresponding to the pithing of small animals in the laboratory. An injury above the origin of the phrenic, on one side, is not necessarily fatal. Injuries to the posterior portion of the high cervical cord, as well as to the membranes, may be followed by more or less atrophy of the genital organs, with corresponding impotence, Larrey claiming that this may take place even when the cord itself is not affected.

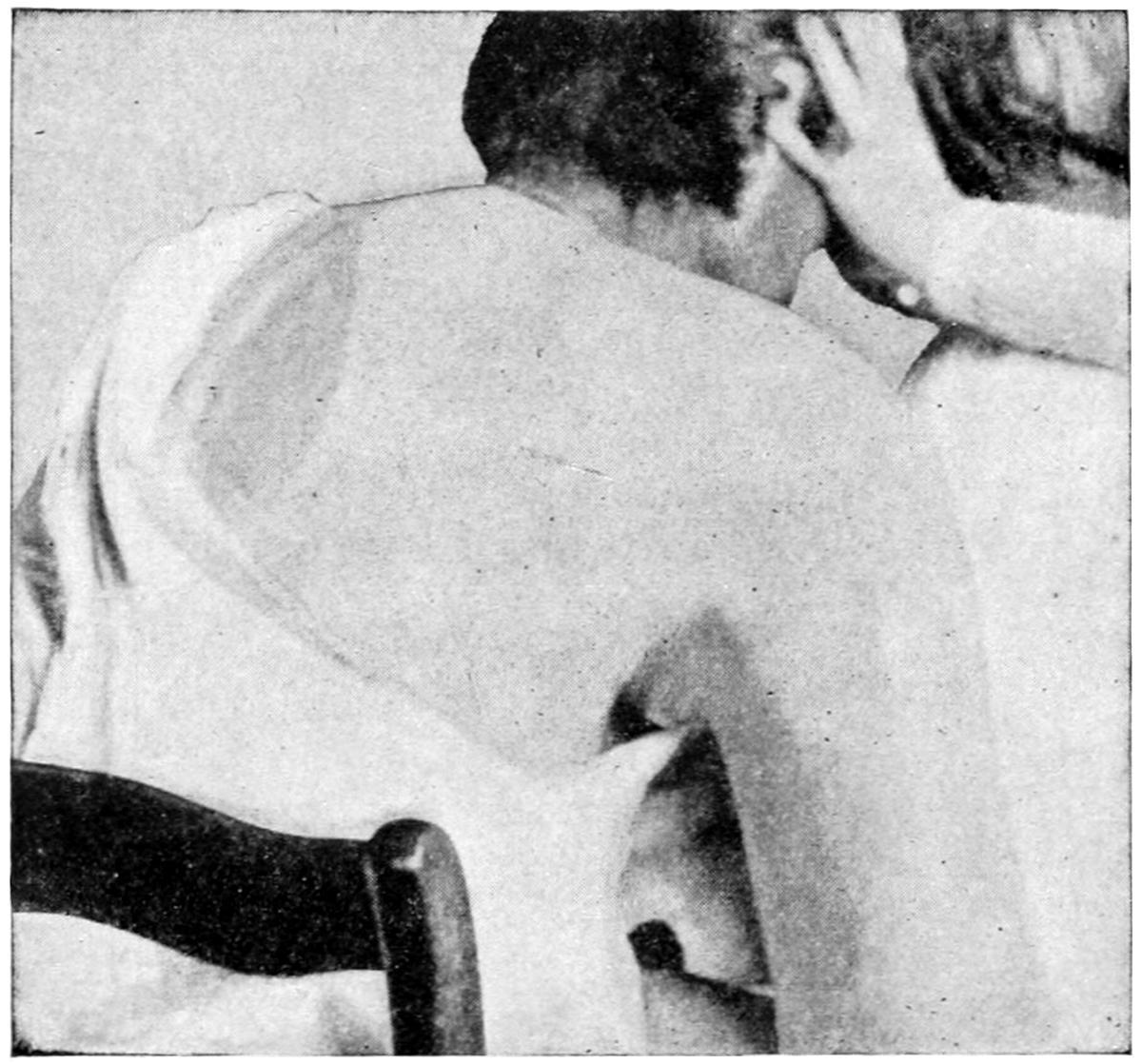

Ruptures of muscles and separations from their insertions or origins are occasionally noted. The scapular muscles are occasionally torn loose. A reflex spasm of the trapezius which follows some of these injuries will produce a posterior form of acute torticollis (wryneck) described in the chapter on Orthopedics (XXXIII). The resulting deformity and stiffening might be confounded with arthritis of the upper vertebral joints. It is to be overcome by traction and by suitable apparatus, save in extreme cases, when division or excision of a sufficient portion of the muscle may be practised.

Of great interest are the blood vascular tumors of the neck, both those of spontaneous and of traumatic origin. Large angiomas, either of the arterial (cirsoid aneurysm) or of the mixed or venous type, are seen about the neck. Here more than anywhere else are found peculiar venous dilatations, especially of the smaller veins, which

Carotid aneurysm successfully treated by complete extirpation (Author’s Clinic )

form cavities in a tissue that becomes thereby almost erectile. Should these tumors connect with the arteries they will pulsate. If composed of larger veins they will prove quite compressible. These tumors should be extirpated, care being taken to place a provisional or permanent ligature upon the large vessels connecting therewith before the tumor itself is attacked. Occasionally the ampullæ of these growths become sufficiently large to entitle the growths to be considered as sanguineous cysts. The neck is also frequently the site of the smaller varieties of these growths which constitute the ordinary nevi. (See chapter on Tumors.)

Aneurysms of the cervical vessels are more frequently of spontaneous than traumatic origin. They may, however, result from contusions or penetrating injuries. While no vessel in the neck always escapes, it is the common carotid which is more frequently affected than the others. The general subject of aneurysm has been considered. Care should be taken not to confuse the vascular and pulsating goitres, or other pulsating cysts of the thyroid. It is necessary also to distinguish aneurysmal pulsation from that which is transmitted through a tumor overlying the vessels or which may be seen in some of the extensive malignant tumors of the neck. When

the diagnosis of aneurysm is made the surgeon should decide what vessel is primarily affected. This, however, is not always possible, as an aneurysm of the vertebral artery projecting forward is liable to be mistaken for one of some other trunk.

Aneurysm in the neck, unless very deep, and in a very unfavorable subject, is always an indication for operation. While operation necessarily includes ligation, either on the proximal or distal side, if this can be practised the sac itself may be treated just as though it were a tumor of any other character, and extirpated. I have myself had satisfactory results by the last-mentioned procedure (Fig. 492). The existence of laryngeal paralysis, especially unilateral, which is not easily accounted for in other ways, should excite a suspicion of aneurysm, with consequent pressure upon the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Its possibility should be excluded as part of the diagnosis.

Wounds of the subclavian vessels give rise to serious hematomas which may be converted into spurious traumatic aneurysms of arteriovenous character. When such a tumor pulsates it is probably connected with the subclavian artery, which should be ligated. It may be possible to make this ligation above the clavicle, but a portion of the sternum should be removed as well as the inner end of the clavicle for a more complete exposure. On the right side at least the artery can only be reached above the bone after dividing the scalenus anticus, where a provisional ligature may be placed. After this the sac should be incised and the vessel ligated, on either side of it, so that the provisional ligature may be removed. On the left side it is safe to ligate the second portion of the artery at once. The clavicle should be divided to afford better exposure, and its ends reunited with silver wire (Fig. 493).

Any open wound of the subclavian vein is a serious affair, as bleeding will be profuse, and there is also danger of air embolism. Immediate occlusion with an antiseptic dressing would probably afford better prospect than any attempt to enlarge the wound and secure the divided vessel. If the vein be thus attacked its proximal portion should be first secured in order to avoid the entrance of air. Meantime much of the hemorrhage from the distal end may be

Traumatic aneurysm of axillary artery.

prevented if pressure be made in the axilla upon the axillary vein. If the vessel be secured both ends should be tied.

In instances of accidental injury, or that included in the removal of large and deep tumors, the thoracic duct on the left side and the lymphatic duct on the right have been injured or divided. It is one of the possible dangers in performing extensive operations on the root of the neck, especially on the left side. Its occurrence would be indicated by oozing of the milk-like lymph. The accident has not been frequently reported. It would render closure of the wound without drainage impracticable, but it has been found sufficient to place a deep packing and to rely upon the natural healing process (granulation) by which such a wound would be gradually closed.

It may be said of vascular lesions that when it appears to be necessary the upper part of the sternum may be resected, as it adds little to the danger and exposes the operative field in a more desirable way. There is no better operative method for ligation of the innominate artery than that which includes removal of the upper end of this bone. Incidentally it may be added that this is also justifiable in certain penetrating wounds of the trachea and in attacking retrosternal goitres or lesions of the thymus.

PHLEGMONS OF THE NECK.

Phlegmonous affections in the region of the neck are serious because of the complications which may ensue. The more deeply they lie the greater this danger. This comes not only from septic processes which may follow veins and lymphatics, but from burrowing of pus along and between the deeper muscle planes, which may carry it into one of the mediastinal spaces or within the thorax. These phlegmons may be primary, or may follow infection spreading through the open crypts of the tonsils, or the open pathways afforded by diseased teeth and by superficial ulcerations. An infection of a tonsil may cause an abscess which presents beneath the jaw, while a deep axillary abscess may be the consequence of a phlegmon beginning in the neck. Not infrequently they come about through the mechanism of infected lymph nodes, which may sometimes produce multiple or extensive single

abscesses. These phlegmons occasionally follow the exanthems, especially scarlatina, and the variety of directions in which infection may spread from the middle ear is well known, since it may cause phlegmon in the neck or empyema of the mastoid antrun and even fatal disturbance within the cranium. When the resulting pus travels downward in front of the thyroid and sternum it will appear upon the thoracic wall; when behind the trachea and the oesophagus, or along the large vessels of the neck, it will be seen either within the thorax or at the root of the neck, possibly opening into the esophagus or spreading to the axillary space. Retropharyngeal abscesses are often the result of caries of the vertebræ, but may occur in consequence of a deep cellulitis caused by extension from some focus within the nasopharyngeal cavity. This is an illustration of the rule that pus travels in the direction of least resistance.

Diagnosis.

—The diagnosis of cervical phlegmons is usually not difficult, especially when they are superficial. The everpresent indications of redness and edema of the surface, pitting upon pressure, tender swelling, and loss of function of the surrounding parts, often with fixation through muscle spasm, coupled with the general systemic disturbance, and, in desperate cases, the indications afforded by the blood and the urine, will enable a diagnosis to be made, usually without the use of the exploring needle. This, however, may be employed if necessary. The same is true in lesser degree of tuberculous collections of pus and pyoid, which have been earlier described as “cold abscess.” Only in the beginning of its course can any doubt arise concerning the nature of a carbuncular process.

A somewhat typical type of deep phlegmon is often referred to as angina and Vincent’s angina. Semon regards these manifestations as expressions of an acute septic cellulitis which has been described as abscess of the larynx and as erysipelas of the larynx, and which other writers refer to as cynanche tonsillaris, acute peritonsillitis, etc. The disease may occur in healthy individuals, more often in the diabetic. A violent sore throat is followed by serious dysphagia, with considerable edema of the pharynx, whose surface is of a dark-blue color. Patients may become unable to swallow, while hoarseness with aphonia will result from edema of the glottis. The epiglottis will

be darkly discolored, greatly tumefied, and nearly obscuring the entrance to the larynx. Dyspnea may necessitate tracheotomy. A light-colored false membrane may be seen in the throat. There is always marked lymphatic involvement. The disease may be more confined in some cases to one side. Vincent has described a particular spirillum or bacillus which he found in some of these instances. The infection here doubtless proceeds from the mouth or the tonsils, its activity being due to symbiosis of various organisms. It is to be distinguished from Ludwig’s angina, which is rather a submaxillary affection than a retropharyngeal. It infrequently leads to retropharyngeal abscess.

Ludwig’s angina, also called infectious submaxillary angina, is an infectious cellulitis of the mouth. The tongue is swollen and immovable; the mouth more or less fixed, with difficulty of swallowing, and the condition is one of extensive infiltration, with formation of pus, which is likely to burrow. In some of these cases the Micrococcus tetragenus is the organism at fault. In my experience when present it leads to a brawny infiltration which is slow to subside or disappear.

Treatment.

—The early recognition and evacuation of pus are called for in all cervical phlegmons. The presence of pus may be assumed before it can be recognized from external evidence. Therefore when swelling begins to mask anatomical outlines, or to produce difficulty of swallowing or breathing, free external incision, with deep dissection, will prove much safer than to leave such a case to itself. Retropharyngeal abscesses, or such collections as may be recognized in the tonsil or in the pharynx, may be opened from within the mouth. That there should not be too much haste in this direction, however, was indicated to me when a wellknown surgeon plunged a bistoury into what he supposed to be an abscess of the tonsil and found it to be an aneurysm, the patient dying within five minutes in his office.

Early and free incision will relieve tension, and do good by a certain amount of bloodletting, even if pus is not reached, while an easier outlet for it will be afforded when it does form. However, the surgeon will rarely fail to find it if he goes sufficiently deep or in the

right direction, when the existing symptoms and signs are of serious import.

The operator should incise freely in the beginning, after which deep dissection is best effected with some blunt instrument. The exploring needle may afford valuable information, but if the deep tissues be edematous we may feel quite sure of the presence of pus in the neighborhood. Souchon has described a method of guided dilatation which requires a series of dilating instruments, and which will give good results. Search for pus can be made without them by using the blade of a dissecting knife or hemostatic forceps, or the blades of a pair of scissors to stretch a small opening. The less tissues are cut and the more they are thus separated the better.

Perilaryngeal or peritracheal abscesses are likely to cause dyspnea and show a tendency to extend downward along the trachea into the thorax. In these locations they produce a peculiar diffuse cellulitis, which was described by Dupuytren. Such phlegmons may extend from the ear to the clavicle or from the back of the neck to the larynx. Pus will collect in many small interspaces, and purulent infiltration will affect many of the tissues, and may produce gangrene. This condition has also been described by GrayColey and by Hannon. The surface not infrequently seems to be involved in erysipelas. In fact it is doubtless true that most of these affections are of the streptococcus type, where it is impossible to distinguish between erysipelas and cellulitis. Tracheotomy as well as the other free incisions may be indicated. An early tracheotomy should be made whenever suffocation threatens from any swelling or edema. The latter occurs so suddenly that a tracheotomy should be made early rather than wait for its necessity, especially when patients cannot be kept under constant observation. The operation may be done under cocaine, while the presence of the tube will then permit the administration of one of the ordinary anesthetics without embarrassing respiration.

All of the other phlegmons, no matter what type they assume, are to be treated on the same general principles. If seen, however, before incision and drainage appear these cases may be treated locally with the compound ichthyol-mercurial ointment, or with Credé’s silver ointment, re-inforced by hot external applications; and

Welcome to our website – the ideal destination for book lovers and knowledge seekers. With a mission to inspire endlessly, we offer a vast collection of books, ranging from classic literary works to specialized publications, self-development books, and children's literature. Each book is a new journey of discovery, expanding knowledge and enriching the soul of the reade

Our website is not just a platform for buying books, but a bridge connecting readers to the timeless values of culture and wisdom. With an elegant, user-friendly interface and an intelligent search system, we are committed to providing a quick and convenient shopping experience. Additionally, our special promotions and home delivery services ensure that you save time and fully enjoy the joy of reading.

Let us accompany you on the journey of exploring knowledge and personal growth!