forging a new south

The Life of General John T. Wilder

Maury Nicely

the university of tennessee press Knoxville

Copyright © 2023 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville. All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. First Edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nicely, Maury, author.

Title: Forging a new South : the life of General John T. Wilder / Maury Nicely.

Other titles: Life of General John T. Wilder

Description: First edition. | Knoxville : The University of Tennessee Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Summary: “John T. Wilder was an entrepreneur, Civil War general, and business leader who would become influential in the development of post-Civil War Chattanooga. A northern transplant who made his early fortune in the iron industry, Wilder would gain notoriety in the Western Theater through his victories at the battles of Chattanooga, Chickamauga, and throughout the Tullahoma and Atlanta Campaigns while leading the famous ‘Lightning Brigade.’ After the Civil War, he relocated to Chattanooga and began the Roane Iron Company and fostered ironworks throughout the southeast. He was elected mayor of Chattanooga but would fail to be elected to Congress as its representative. Finally, he was instrumental in the establishment of national military parks in Chattanooga and Chickamauga. Nicely’s biography captures the life of a man important to the development of Chattanooga and East Tennessee and argues that Wilder was influential in bringing both northern and immigrant populations to the area.”

—Provided by publisher

Identifiers: LCCN 2022056859 (print) | LCCN 2022056860 (ebook) | ISBN 9781621908005 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781621908012 (adobe pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Wilder, John Thomas, 1830–1917. | Generals—United States— Biography. | United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Biography. | United States. Army. Wilder’s Brigade. | United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865— Regimental histories. | United States. Army—Biography. | Businessmen—Tennessee— Chattanooga—Biography. | Tennessee—Economic conditions—19th century. | Chattanooga (Tenn.)—Biography. | Greensburg (Ind.)—Biography.

Classification: LCC E467.1.W69 N54 2023 (print) | LCC E467.1.W69 (ebook) | DDC 355.0092 [B]—dc23/eng/20230111

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022056859

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022056860

Illustrations

photographs Following page 185

John Thomas Wilder and Martha Stewart, 1858

Ridgway Foundry, Columbus, Ohio

Wilder’s Patented “Improved Horizontal Water-Wheel”

John T. Wilder Residence, Greensburg, Indiana

Lt. Col. John T. Wilder, 1861

Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton

Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner (CSA)

Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans (US)

“Wilder’s Mounted Infantry Passing the Blockhouse of the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad”

Spencer Repeating Rifle

Hoover’s Gap Battlefield

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Capt. Eli Lilly (US)

First Presbyterian Church, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Friar’s Island, Tennessee River

The “Ditch of Death,” West Viniard Field, Chickamauga

Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana (US)

Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden (US)

Roane Iron Company Furnace, Rockwood, Tennessee

Hiram S. Chamberlain

Superintendent’s House, Rockwood, Tennessee

Company Store, Rockwood, Tennessee

Roane Rolling Mill, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Stanton House, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Opera House Foundations, Chattanooga, Tennessee

John T. Wilder Residence, East Terrace, Chattanooga, Tennessee

H. Clay Evans

David M. Key

Tomlinson Fort

Confederate Monument, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Group of Chattanooga’s “Distinguished Citizens,” 1881

Frank Stratton

John T. Wilder’s “Rustic Boarding House,” Roan Mountain

Roan Mountain Inn, Roan Mountain Station, Tennessee

John T. Wilder Residence, Roan Mountain Station, Tennessee

Wilder Family at Roan Mountain Station, 1886

Northern Methodist Church, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga (U.S. Grant) University, Chattanooga, Tennessee

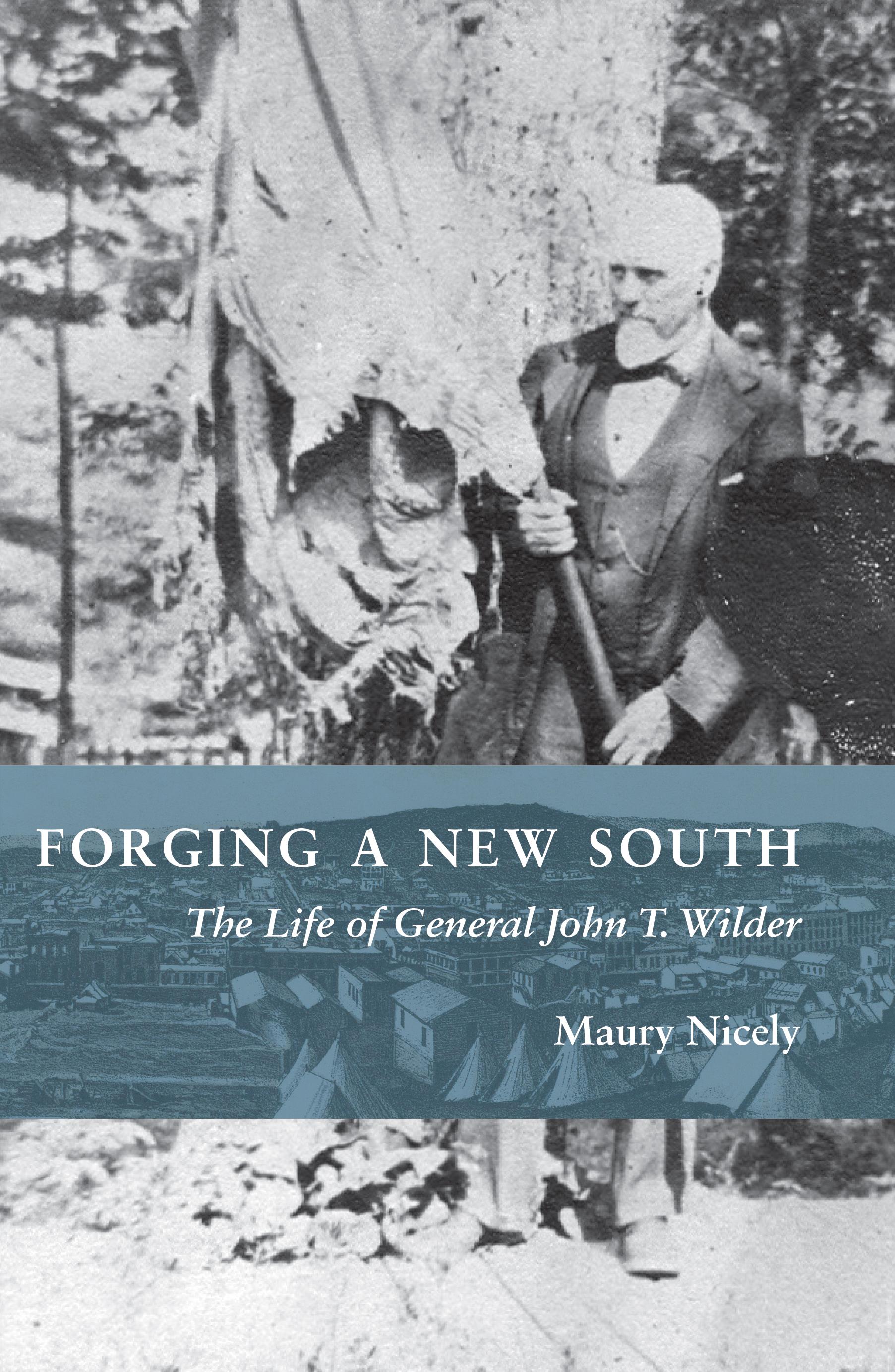

John T. Wilder, early 1880s

John T. Wilder Congressional Campaign Ribbon, 1886

John Randolph Neal

Cloudland Hotel, Roan Mountain

John T. Wilder at Roan Mountain, 1886

Lightning Brigade Officers atop Lookout Mountain, 1880

John T. Wilder, 1887

Joseph Wheeler

Carnegie Hotel, Johnson City, Tennessee

John T. Wilder Residence, Johnson City, Tennessee

President Benjamin Harrison Visit to Johnson City, 1891

Crawfish Springs, Chickamauga, Georgia, 1898

Henry Van Ness Boynton Commissioners, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, 1892

Wilder Brigade Monument, Chickamauga Battlefield

U.S. Custom House, Knoxville, Tennessee

John T. Wilder

Dr. Dora Lee Wilder

John T. Wilder Residence, Knoxville, Tennessee

G.A.R. Monument, Knoxville, Tennessee

Imperial Hotel, Monterey, Tennessee

John T. Wilder Residence, Monterey, Tennessee

John T. Wilder in Monterey, Tennessee, 1913

Lightning Brigade Reunion, Chickamauga, 1903

Wilder Point, Signal Mountain, Tennessee

G.A.R. Encampment, Chattanooga, Tennessee, 1913

John T. Wilder Grave, Forrest Hills Cemetery, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Wilder’s Children at His Funeral, 1917

John T. Wilder, c. 1900

maps

Map 1. Battle of Munfordville 36

Map 2. Battle of Hoover’s Gap 86

Map 3. Crossing the Chickamauga 126

Map 4. John T. Wilder’s East Tennessee 236

Prologue

Mid-summer in the woods of northwest Georgia. Suppertime yet the air is hot and thick. Humidity drips from the trees surrounding the field; those waiting can feel the dampness at their collars.

At the far side of the meadow, a murmur rises. The first few emerge from the thickets, weighed down by the trappings flung over their shoulders. They do not pause at the tree line but step out into the open. Irregular drum bursts and the braying of horns draw them across the field. Others fall in step behind, freshly cut hay crunching beneath their feet as they enter the clearing.

They reach the middle of the field. Wordlessly they toss down their blankets. Styrofoam coolers plunk to the ground with a squeak and the clinking of bottles. Tee shirts are pulled from sticky torsos, toes let out to wiggle in the crisp browned grass of early July. Quilts, their corners pinned down with discarded sandals, scatter the ground like a patchwork.

At the crest of a small rise, a red, white, and blue flag hangs from a stone tower, fluttering in the slightest of breezes. At the foot of the tower, musicians tune their instruments, tightening pegs and wiping brows. Frisbees and footballs arc overhead.

The laughter and chatter subside as a man with a baton steps from behind the tower and raises his hands.

Silence and a thick heat hang over the field for a long second.

It begins with a crash of sound.

The Wilder Brigade Monument is an emblematic symbol of the Chickamauga military park. From a roughly paved pull-off at Tour Stop 6, visitors walk through an iron gate and climb a winding stone staircase to the

highest point in the park, from which the battlefield spreads out into the distance, undulating fields bisected by woods and creeks, the foothills of the mountains at the horizon. Shadowing the iron tablets, green-weathered cannon, and sculptures littering the spot where widow Eliza Glenn’s cabin once stood, the tower overlooks the field like a massive chess piece, a general surveying the terrain with upthrust chin, squinting through battlesmoke toward the enemy.

Celebrating the United States Bicentennial, on July 4, 1976, the Chattanooga Symphony played a “Pops in the Park” concert at the foot of the historic tower. It soon became an annual event, drawing thousands to listen to the patriotic music of Copland, Tchaikovsky, and Sousa. Most of those in attendance, however, were little aware of the tactical movements that took place on the ground where they sat, the story of the iconic stone tower, or the achievements of its namesake.

John Thomas Wilder enlisted in the 17th Indiana Infantry (17 IN) regiment in a patriotic fit in April 1861; he rose to command the regiment, then its brigade. In the aftermath of Chickamauga, where Wilder’s Brigade delayed the Confederate advance and helped to save the Union Army, he was breveted a brigadier-general. “Many believe General Wilder to be the greatest military genius and soldier developed during the war,” a 1905 biographical article gushed. Plagued by a nagging illness, however, he retired from the war in October 1864, his military career spanning roughly three years and six months.1

Perhaps rightfully so, biographies of the notable, colorful, and notorious figures of the American Civil War tend to focus almost exclusively upon the four-year period between 1861 and 1865—their postbellum careers are often a footnote to their wartime exploits. Wars, of course, make for exciting reading—more so than business partnerships and financial investments. As such, biographers focus upon the thrilling wartime adventures of their subjects, in comparison to which their civilian lives often pale.

Many Civil War icons, moreover, had less-than-prosperous peacetime careers. The war was the highlight of their public lives, inspiring otherwise average men to heroic (or notorious) deeds. Many reentered civilian life only to settle into dull mediocrity or failure—the qualities that had served them in the heat of battle ill-suited to the humdrum of daily existence. For many war heroes, there was not much beyond the war worth telling.

Such was not the case with Wilder. “It would take a book of space and great time to enumerate the successful undertakings of this one man,” pro-

posed an 1891 newspaper article. “A volume would hardly suffice to tell the story of his life,” echoed a turn-of-the-century profile. He was a fascinating, if relatively minor, Civil War officer. He was bold and innovative, his ingenuity and incapacity for boredom spurring him to take advantage of technological advances spurred by the war and pioneer tactical innovations of his own devising. His “Lightning Brigade,” which modernized the nineteenth-century art of war, was “known from Maine to Mexico, without whom no history of the Civil War can be written.”2

War, though, occupied but four years in the eighty-seven-year life of John T. Wilder. Even before the rebellion, he was a successful Indiana businessman. In the wake of the conflict, recognizing the business opportunities in the southern mountains where he had recently fought, he relocated to East Tennessee. He would spend the remainder of his life there, charging into the industrial arena as he had done on the battlefield. Congenitally frustrated by idleness, always on the prowl for new opportunities, he was a New South visionary who created dozens of businesses, factories, mines, hotels, and towns in his adopted home. “His name was a household word in the South,” one writer praised. “Industry after industry here and in upper East Tennessee were inaugurated by Gen. Wilder or through his influence.”3

He ventured South into a region under the yoke of Reconstruction, where the term “carpetbagger” was a pejorative for the Northerners flowing in to capitalize on the federal occupation of the South. In sharply divided East Tennessee, ugly guerilla violence would linger for years. A Union veteran seeking to set up shop in the former Confederacy doubtlessly did so at considerable personal risk. Wilder came, however, not as a conquering warrior claiming the spoils of war, but as a champion of sectional reconciliation and the development of a new South.

Throughout his career, he exhibited a deep commitment to binding the wounds created by the war; at every possible turn, he sought to affiliate with former Confederates as well as Union veterans in his business efforts, and he was well-respected despite his former status as a “Yankee invader.” Of Wilder, one former rebel officer offered that “no man did more . . . in bringing order out of the chaos” of the war. His goal was not to simply wring wealth from the region; he cast his lot with the defeated South, optimistic that together they would create a new economy and society. His mindset was encapsulated upon his death by an associate who remarked, “Gen. Wilder told me thirty-five years ago that doing well was mighty hard to beat.”4

The story of John T. Wilder is more than a Civil War biography. This is the story of a man—a soldier and industrialist—who not only made his mark in the crucible of war, but also led the effort to forge a new South in the wake of conflict.

Part One

old northwest to old south

One

On April 20, 2001, onlookers gathered for the unveiling of a historic marker at the corner of Main and Lathrop Streets in the small town of Greensburg, Indiana. A handful of mustachioed Civil War reenactors, resplendent in blue-trimmed infantry coats and high-crowned Model 1858 “Jeff Davis” dress hats, milled around among the crowd. They were armed with reproduction muzzle-loading muskets—not the Spencer repeating rifles that were the hallmark of the “Lightning Brigade,” the otherwise-eponymous unit whose commander the crowd was gathered to honor.

Dedicated to “Civil War General John T. Wilder,” the iron marker stands on a quiet residential street in front of the home built by Wilder and his wife, Martha, during the closing years of the war. Although his sojourn in Greensburg was fairly brief, Wilder is memorialized by of one of only three historic markers in and around Greensburg. To that end, at the unveiling of the marker, it was noted that it “commemorates the life of a man who, although he spent only eleven of his eighty-seven years in Greensburg, non-the-less was, and continues to be recognized as one of the community’s finest citizens.”1

Throughout his long life, one enduring character trait of John Thomas Wilder was a certain restlessness, an “itchy heel” that kept him surveying the horizon for new opportunities, leaping from one to the next. He was always lured more by the prospect of a new challenge than by the daily drudgery of maintaining his affairs. “I am essentially a pioneer by disposition,” he advised a newspaper reporter in 1887. “Whenever an enterprise gets to running along smoothly in a rut, I get out of it.” This opinion was consistent with American attitudes of the time. “The American has always something better in his eye, further west,” one visitor to the young country wrote in 1823, “he therefore lives and dies on hope, a mere gypsy in this

particular.” This restiveness, coupled with a bold confidence that at times bordered on recklessness, led Wilder to embark headlong upon new ideas and projects from the time he was a young man to the end of his days.2

Wilder’s temperament is not at all surprising when set against the many migrations of his ancestors, who came quite early from England to the American colonies. Around 1584, his great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, Thomas Wilder, was born at Shiplake-on-Thames, a rural community on the west bank of the River Thames in Berkshire, one of the oldest counties in England. The family have been labeled “Puritans,” and upon Thomas’ death on October 23, 1634, his widow, Martha, possibly motivated by the persecution of Protestants under King Charles I, emigrated to America. In May 1638, she sailed from Southampton on the Confidence, bound for Massachusetts Bay; while the evidence is inconclusive, she may have sent some of her children ahead on the perilous journey while settling her affairs in England. She died in April 1652 in Massachusetts, where the family would remain for a handful of generations.

Born in 1623, Edward Wilder received a ten-acre land grant in Hingham (Suffolk County), a town on Boston Harbor that was settled in 1635 and purchased three decades later from the native Wampanoag tribe. In 1651, he married another English colonist, Elizabeth Eames (or Ames), with whom he had eleven children. He was made a freeman in 1644, which provided him with the rights to own land and become a member of the church; this advancement suggests that he had served a term as an indentured servant, possibly in exchange for his passage to America. His rise within the community was complete when, in 1667, he became a selectman, a member of the local assembly that administered the town of Hingham. In 1675 (age 52), he was impressed into military service during King Philip’s War, the first native war in America, after the Wampanoag tribe attacked colonial towns throughout New England; in that way, the Wilder family came quite early to military service in America. Edward Wilder died in 1690, Elizabeth in 1692.

Few facts have survived with respect to the next two generations of Wilders. John Wilder (1653–1724) married Rebecca Doggett (1655–1728) in 1675. His son, Ephraim (1696–1770), a blacksmith by trade, married Mary Lane (d. 1770) in Hingham. He is the first Wilder documented as working with iron, a trade upon which subsequent generations would build. At some point, he relocated to Abington (Plymouth County), Massachusetts, midway between Boston and Plymouth, where he died in 1770.

The eighth of nine children, Seth Wilder (c. 1738–1814) married Mariam Beal in 1761 and moved west to the fairly new town of Cummington, Massachusetts, around 1773, possibly after a chimney fire destroyed their home

in Hingham. Like his father, he was a blacksmith. It has been claimed that he was involved in the Boston Tea Party uprising, but the sole source, a newspaper claim made by a descendant in 1858, cannot be validated.

John T. Wilder’s grandfather, Seth Wilder, Jr. (1764–1813), married Tabitha (or Dorcas) Briggs (1766–1825) around 1788. He died at age fortynine in 1813 and is buried in Cummington.

Reuben Wilder (1797–1880) was John T. Wilder’s father. Like many New Englanders in the decades following the Revolution, he sought his fortune in the green lands of the advancing frontier, venturing west to Hunter Village (Greene County), New York, a small town in the Catskill Mountains. It was a pristine region. Designated as Lot 25 of the two million-acre Hardenbergh Patent granted by Queen Anne in 1708, the land was purchased by John Hunter in the 1790s and christened “Greenland” because of the rich forest lands surrounding the village. After Col. William Edwards established a tannery to exploit the vast hemlock forests whose bark was used for tanning hides, it was renamed “Edwardsville,” but after the tannery failed the chagrinned townspeople substituted Hunter’s name in 1814. The villagers continued to make use of the forests, establishing lumber mills and furniture factories that supported the town until a bristling tourist trade developed in the mid-nineteenth century.

In 1825, Reuben Wilder married Mary Merritt, born in 1793 in Hunter Village. He was a farmer and millwright, described as a “mill contractor and prosperous” and praised as “a man of sturdy self-reliance; a strong man who never used his strength; without ambition beyond living well and educating his children; [and] noted for his broad, practical good sense.” Politically, he was a Whig, although he became a Republican after the collapse of the Whig party.3

John Thomas Wilder was born on January 31, 1830, in Hunter Village. The details of his early life are sparse and have been oft-repeated in biographies over the years. He was the third of five children, following sisters Elizabeth (1826) and Clarissa (1828), and preceding Mary Ann (1832) and Horace (1834). He is said to have attended the local common (public) schools, where accounts uniformly report that he obtained “a fairly adequate education for that day.” Even as a youngster, he was clear-eyed and ambitious. An alert and inquisitive young man, he was interested in natural curiosities, collecting a cabinet full of stones and minerals that he studied throughout his childhood. “Though essentially a business man,” it was later remarked,

“he has scholarly attainments, especially in geology, mining and engineering, which he took up and mastered without a teacher, and on which his advice is constantly sought.” A relative described the youthful Wilder as “a handsome young man, of fine physique, mentally alert, fond of research [and possessed of a] genial and hospitable nature.” He grew to be six feet, two inches tall and of solid build, or as one biographer pronounced, “well proportioned.”4

Wilder’s family background and interest in the study of minerals naturally drew him toward the manufacture of iron. Although an 1886 campaign biography employed the stock claim for political aspirants that Wilder “started in life a poor boy and has risen to be a prominent man,” his father was a successful master millwright who established mills throughout the frontier. Wilder almost certainly completed a period of apprenticeship under his father, learning the various aspects of the millwright trade, as did his brother Horace.5

“I was born on the Hudson and went west in ’44,” Wilder declared in later years. “From the age of fourteen to twenty-one,” one account echoed, “he served an apprenticeship of seven years as a founder, machinist, mill wright and pattern-maker.” In reality, he did not leave home quite so early; the 1850 census lists him as a millwright living with his parents in the town of Olive (Ulster County), New York, immediately south of Hunter Village. It was around that time that the twenty-year-old Wilder, having completed his schooling (and reportedly against the wishes of his family), determined to head west, where new lands and opportunities beckoned. “Though his father was a man of means,” one profile recounted, “he was too proud to ask him for anything, and left home when a boy, and has made his way by industry and push and vim and snap ever since.”6

His initial destination was Columbus, Ohio. “As a boy,” offered an embellished newspaper account, he “had run away from the school at which his father’s care had placed him, and had supported himself by serving an apprenticeship to a master machinist in Ohio.” During the early years of the republic, the Appalachian Mountains stood as a formidable barrier to western expansion. Then, in 1825, the 363-mile Erie Canal was completed, connecting the Atlantic Ocean via the Hudson River (and New York City) to the Great Lakes at Buffalo, New York. It was an engineering marvel. The success of the canal enabled New York to commercially eclipse other Northern cities, and the Northwest frontier, with newfound access to eastern markets, was inundated with settlers pouring into the region by way of the canal.

From Buffalo, travelers continued by boat along the southern edge of Lake Erie to Cleveland. From that point, the Ohio & Erie Canal pierced

the interior of the state. An eleven-mile feeder channel branched off from the canal toward Columbus, which was laid out as the capital of Ohio in 1812 due to its central location. Until the Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad reached the city around 1851, the canal remained the primary means of reaching the capital.

For a time, Wilder was unable to find work in Columbus. “Too poor to enjoy the society of people of the station in life which his father’s family occupied, and too proud to associate with those of pecuniary circumstances like his own,” it was noted, “he took up the study of mineralogy and geology in order to have some occupation for his leisure moments. Of keen powers of observation and marked quickness of the true inwardness of whatever he read, the young man succeeded in thoroughly mastering the sciences which he pursued.” Though this account ignored the fact that the young man had studied mineralogy since boyhood, it did confirm that his scientific interests were not simply a passing childhood fascination.

Gilded Age newspapers often printed colorful but apocryphal morality stories about the childhoods of public figures; Wilder was no exception. “Practically penniless,” the young apprentice was said to have at one point found a coin on the street and, famished, raced to High Street (the main north-south thoroughfare in Columbus) to buy a bun. Once there, however, he determined that he could wait until he was even more starved before parting with the coin. His persistence and frugality were highlighted by the claim that “he kept that coin in his pocket through all of his eventful days.” No evidence exists of Wilder sharing this anecdote himself.

He eventually secured an apprenticeship at the Ridgway Foundry (Columbus Foundry) at the corner of Broad and Water Streets on the west bank of the Scioto River. The foundry was built in 1822 by New York native Joseph Ridgway, who advertised in the Columbus Gazette that he was “preparing a large plough for the special use of breaking up new prairies and barrens.” Operated initially by horse (as opposed to steam) power, the foundry produced the cast-iron “Wood’s Plow,” touted as especially durable for use in the tough fields of the Midwest. “When I came here in 1826,” a competitor recalled, “Ridgway’s foundry was the only manufacturing establishment in the place. For several years all the pig metal was hauled from Granville furnace in a two-horse wagon, which made three trips a week, aggregating about five tons in that time. This was principally used in the manufacture of plows.”

In 1830, the firm converted to steam power, which enabled production of a wide variety of products, including steam engines, stoves, firedogs (which held logs in a fireplace), and gudgeons (flat, circular bearings). It was at the

Ridgway Foundry that the young Wilder “learned the iron business from ore beds to steel ingots.” He was taught the various phases of the trade, including drafting (drawing images of a metal item to be manufactured), pattern making (transforming the drawing into a mold, into which molten iron was poured to create the item), and mill-wrighting (building mill machinery that was correctly aligned so as to operate properly). Wilder later asserted that he “served seven years apprenticeship at the trade of a millwright,” after which he “acted as foreman of a machine shop for one year,” an apprenticeship that would provide him with the skills and knowledge he would employ throughout his business career.

Impressed with the young man’s skill and work ethic, Ridgway eventually offered Wilder a one-half share in the foundry (the other half offered to Ridgway’s son). Though he was surely appreciative of the mark of respect conveyed by the proposal, Wilder rejected the offer; he had set his sights higher than managing another man’s business. His ambition would lead him farther westward, where he would strike out on his own.7

From Ohio, Wilder’s travels carried him to the neighboring state of Indiana. By 1850, railroads linked Columbus to Cincinnati; it was a small leap across the state line to Lawrenceburg, Indiana, on the Ohio River downriver from Cincinnati. Settling there in 1857, he was involved in several business enterprises, including a contracting partnership with William Probasco, a New Jersey native millwright who had come west a decade earlier. The business fell apart due to a difference in moral principles. Although he was by no means prudish, Wilder “never drank, never gambled, [and] never used tobacco or dissipated in any way.” Probasco did not share those attitudes, and when the business obtained a contract to build a large distillery in Petersburg, Kentucky, Wilder ended the partnership.8

After a brief spell in Lawrenceburg, Wilder in 1857 pulled up stakes and moved to Greensburg, a small town midway between Cincinnati and Indianapolis. After the Delaware Indians ceded the surrounding land to the United States in the 1819 Treaty of St. Mary’s, Col. Thomas Hendricks, a Pennsylvania veteran of the War of 1812 and early Indiana legislator, was one of two men selected to survey the area—a plum job he likely obtained because his brother, William, was the governor of the state at the time. Hendricks donated one hundred acres on which to locate the town, with the hope it would be selected as the seat of Decatur County. The name “Greensburg” was selected by his wife, Elizabeth, in honor of her Pennsylvania hometown.

By 1857, Greensburg was home to twenty-five hundred residents, two steam flouring mills, ten dry goods stores, twelve groceries, two carriage

and wagon shops, two drug stores, four hotels, and four churches. It also boasted one of the finest courthouses in the state, a $100,000 Italianate structure that had replaced the original courthouse, Hendricks’ log cabin.9

The advance of the western frontier was fostered by technological innovation, particularly the spread of rail lines. Most Indianans initially clung to the southern fringe of the state along the Ohio River, “the only important navigable river flowing to the west in eastern North America,” which led to important markets, primarily New Orleans. New infrastructure opened the interior of the state (as when a road connecting the Ohio to Lake Michigan was lain through Greensburg), and as railroads replaced rivers, canals, and rudimentary roads, the population boomed. During the 1850s, railroad mileage within Indiana increased from 212 to 2,163 miles; as a result, the population swelled from 988,416 to 1,350,428, making it the sixth most populous state in the nation. This growth benefited Greensburg directly when the Lawrenceburg & Indianapolis Railroad reached the town in 1853; the following year, the L&I was completed to Indianapolis, forging a vital link between the Indiana capital and Cincinnati (reached from Lawrenceburg via the steamer Forrest Queen).10

With the L&I providing efficient, reliable access to commercial markets within the state (and to the Ohio River, connecting the Old Northwest to the South), Greensburg was a fitting choice for Wilder to focus his business interests on. During the antebellum period, Indiana, with abundant limestone deposits, ready access to extensive coal beds, and fields of timber to be converted to charcoal (key ingredients for the manufacture of iron), was a prime site for the construction of blast furnaces. A combination of natural resources, transportation to markets, and available land provided Wilder with a good chance for success in Greensburg.11

Wilder exhibited no caution or doubt as he laid down stakes in his new hometown. As he would do time and again, he leaped immediately into the Greensburg business community, prompting a later assessment that “perhaps no one from that era left a more lasting legacy from his time in Decatur County than John Wilder.” His most significant business involvement was an iron foundry and machine works begun “on a modest scale” across the tracks from the L&I depot, at the corner of Montfort Street and Railroad Avenue. The business quickly boomed, employing nearly one hundred employees by 1861, such that “at the breaking out of the war [Wilder] was at the head of and half owner of the largest establishment of its kind west of the Ohio.”12 Wilder’s Machine Works sold equipment and erected mills in six states, including Indiana, Illinois, Tennessee, Wisconsin, Virginia, and Kentucky, leading to plaudits that Wilder “built more mills than any man

west of the Allegheny mountains.” The business made him a wealthy man. In the census of July 1860, Wilder, a “30 year old Mill-wright from New York,” was said to possess $6,900 in real estate and $25,600 in personal estate—a substantial sum at the time, particularly for a young man.

Part of his success may be traced to innovations Wilder developed while in Greensburg, chief among them the low head water turbine, which he would patent three times over the years. The novel device was first patented on October 18, 1859, as the “Improved Horizontal Water-Wheel” (Patent No. 25,859). The design proved far more efficient than the typical overshot waterwheel, which was powered by water pouring down from above. Wilder’s turbine was set on its side; water was introduced from the side, funneling through the entire encased wheel, maximizing the water pressure powering the mill. As a result of this and other innovations, he became a nationally recognized hydraulics expert, such that “he was called to serve as a witness or umpire in [disputes occurring in] distant parts of the country.”

Tireless and enthusiastic, Wilder leaped into various other enterprises in Greensburg. He contributed funds to erect the three-story brick Wilder Building on the courthouse square, at the corner of Washington and Franklin Streets. It is said that the International Order of Odd Fellows contributed funds for the top floor, while Wilder funded the first two. He maintained an interest in the building well into the 1870s, long after he had left the town. The Greensburg Woolen Mills, situated on land that he owned at the corner of Main and Lincoln Streets, was built after he agreed to relocate the channel of a creek on the property so that the lot would be large enough to accommodate the mill. He also developed a residential area labeled “Wilder’s Addition,” where he would erect his own substantial home.13

Through the success of his business endeavors, or simple good fortune, within a year of his arrival in Greensburg, on May 18, 1858, Wilder married twenty-year-old Martha Stewart, “a lady of great charm” whose father, Silas Stewart, was “a prominent citizen and one of the founders of the town.” The Stewart family was “banished from Scotland, in 1752, for following the fortunes of Charles in the last Scottish rebellion,” before coming to Indiana. In a photograph of the newly wedded couple, he holds her left hand, which rests lightly upon his knee. The image, the earliest portrait of Wilder to survive (and possibly the first taken), depicts him with the short chin-beard, without sideburns or mustache, which he “sported since early manhood” and which would serve as a distinguishing facial feature throughout his life.

By all accounts, the marriage was a first-rate match. “His genial and hospitable nature was equaled by that of his remarkable wife,” a relative recalled decades later. While Wilder seems to have left no personal diary

reflecting his inner thoughts, his correspondence with Martha, whom he (and other family members) called “Pet,” reveals a caring couple dedicated to one another. Described as “a plain, straight forward, sensible, unassuming, charitable Christian mother and wife, and utterly without vanity,” Martha was said to have “possessed many fine qualities of heart and mind, and was most devoted to the welfare of her husband and children.”

Nine months to the day after the wedding, on February 18, 1859, Martha gave birth to the couple’s first child, Mary. The young family is believed to have lived at 515 East Washington in the first house built on that street. In addition to Wilder, Martha (listed in the 1860 census as a “housewife from Indiana”) and little Mary, a nineteen-year-old domestic servant named Kate Snell lived in the household.14

In a short time, Wilder had become a respected member of the Greensburg community. His businesses flourished. He was said to have an “easy kind-hearted temper” and was considered an “honest and trustworthy” businessman. His business endeavors occupied much of his energy and attention, and letters sent to Wilder during his time in Greensburg frequently complain of a lack of response, indicating that he may not have been an avid correspondent.

Despite running off to the Old Northwest, Wilder maintained a close, caring relationship with his parents and siblings in New York. As secession and the possibility of war wafted in the breeze in early 1861, he was asked to travel to Cleveland, Ohio, to escort his parents, who wanted to visit but were wary of the arduous trip, to Greensburg. “Ma is so anxious to see little Mary,” sister Mary Ann Elmendorf wrote, encouraging the busy new father to make the trip. It is unclear whether the visit took place, but it would not be long before the clouds of war would intervene and carry Wilder in a different direction, far from family, business ventures, and Indiana.15