Brilliance in Exile

The Diaspora of Hungarian Scientists from John von Neumann to Katalin Karikó

ISTVAN HARGITTAI · BALAZS HARGITTAI

Budapest – Vienna – New York

© Istvan Hargittai and Balazs Hargittai, 2023

Published in 2023 by Central European University Press

Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, Hungary

Tel: +36-1-327-3138 or 327-3000

E-mail: ceupress@press.ceu.edu

Website: www.ceupress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Publisher.

Cover illustration: “Scrambled world” by Istvan Orosz

Cover and book design by Sebastian Stachowski

ISBN 978-963-386-625-2 (hardback)

ISBN 978-963-386- 606-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-963-386-607-8 (ebook)

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

2

“Istvan and Balazs Hargittai recount so vividly the inspiring lives of 50 emigrants from Hungary that they seem to be telling their remarkable stories of survival and overcoming themselves. And the paths that these shapers of knowledge took, out of conditions that excluded them, away from intolerance, make the clearest case possible for tolerance and openness. A joy to read!”

Roald Hoffmann, Nobel laureate chemist and writer

2

“The Hungarian emigré scientists Leo Szilard, Eugene Wigner, John von Neumann, and Edward Teller came to the west and changed the world. But their departure from their homeland was just a part of a much larger and longer exodus of brilliant scientists, including several more Nobel laureates. By telling their stories in Brilliance in Exile, Istvan Hargittai and Balazs Hargittai have done more than compile a valuable resource for historians. They have documented a history of Hungary’s intellectual legacy that is both fascinating and tragic – and, it must sadly be said, one that remains poignantly relevant today.

Philip Ball , science writer (London), former long-time editor of Nature, author of Patterns in Nature and Beyond Weird

2

“The contributions of Hungarians to world science and mathematics almost defy belief. In this beautifully organized and meticulously researched book, Istvan and Balazs Hargittai bring to life many of these astonishing “exiles,” showing them as real people.”

Kenneth W. Ford, author of Building the H Bomb: A Personal History

2

“Few countries have produced a brilliant panorama of scientists in exile. Istvan and Balazs Hargittai have assembled a series of sketches of some of Hungary’s most famous physicists, mathematicians, and biochemists – all of whom were emigrés. The reasons for their exiles is punctuated by the bloody forays that intruded on their lives, World War I and World War II, and the uprising in 1956 against the Soviet dominated rule of law. I interacted with four of these exiles, Laszlo Tisza, who taught me atomic physics, George Klein, as a colleague in molecular biology, as well as a local colleague, Peter Lengyel, an excellent biochemist and certainly one of the most polite people I knew, and Olga Kennard, who I met briefly in Cambridge, UK. John von Neumann, Eugene Wigner, Leo

Szilard, Edward Teller were among the great physicists of the 20th century whom I read about. It was a pleasure to read about their own emigration and their achievements. One should never forget their courage in leaving their homeland and then spreading their knowledge in several countries.”

(the late) Sidney Altman, Nobel laureate, Yale University

“A fascinating book. It is remarkable how much talent originated from a small country, and especially from its very small Jewish community. Very interesting and highly readable.”

Avram Hershko, Nobel laureate, TECHNION, Haifa

“The physical chemist Istvan Hargittai, his wife Magdolna, and their son Balazs have, since about a quarter of a century, established themselves as guides par preference in the maze of stories of famous scientists and engineers. As a mountain guide can choose different walks, some to the top of the mountains, some to the lower regions, the Hargittais choose stories ranging from those of Nobel laureates and almost Nobel laureates to “ordinary” scientists and engineers. Istvan and Magdolna have produced fine guidebooks of the science and technology monuments in Budapest, London, Moscow, and New York. In the present book, Brilliance in Exile, Istvan and Balazs have chosen about 50 stories of Hungarian scientists and engineers who emigrated from Hungary during (approximately) the twentieth century. The stories are classified according to 5 periods when something special (such as the Soviet invasion of 1956) made the Hungarians emigrate. Some stories are longer and some shorter, but they are well written and most are beautifully illustrated. For someone enjoying this type of excursion among famous (mainly) men, this book is gefundenes fressen. There is also a very interesting Foreword by Professor Ivan T. Berend, former President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, followed by a detailed Introduction by the authors. These two sections help to structure what the subtitle of the book promises to say something about: The Diaspora of Hungarian Scientists.”

Anders Bárány, Professor Emeritus in Physics at Stockholm University, former Scientific Secretary to the Nobel Committee for Physics, former Deputy Director, the Nobel Museum, Editor-at-Large and Scientific Adviser, the Lindau Mediatheque

“This extraordinary catalogue of a century of Hungarian intellectual diaspora (in science alone) leaves the reader astonished, from one page to the next, that one small nation’s loss could have produced so much of the world’s gain. Reading like a collection of fifty one-act plays, the brilliance of its characters leaves one at a loss for words at the unknown talent that was extinguished, and the danger of repeating the mistake.”

George Dyson, Author of Analogia , Turing’s Cathedral, and Darwin among the Machines

2

“Brilliance in Exile tells the remarkable story of Hungarians who made huge contributions to science outside Hungary. The United States and Britain were among the countries that gained most from the exodus of Hungarian talent. This fascinating book gives powerful support to the authors’ important conclusion that countries that are intolerant and exclusionist lose a great deal, while those that are tolerant and welcoming gain enormously.”

David Holloway, Raymond A. Spruance Professor of International History, Emeritus, Stanford University, author of Stalin and the Bomb

2

“This book describes the extensive Hungarian intellectual and scientific diaspora to Western countries that has taken place during the last century. Some of the names are very familiar, Koestler, Szilard, Szent-Gyorgyi, Simonyi, Polanyi and von Neumann for example, but there have been many more with a total that extends to 50. The list is a highly impressive fire-power of intellectuals, mathematicians, and scientists, some with impressive philosophical and literary leanings. The book summarises their wide contribution to human kind, and discusses why such a diaspora took place, identifying the negative impact that prejudiced and intolerant societies can have on intellectual endeavour and science.”

Sir Paul Nurse, Nobel laureate, Chief Executive and Director of the Francis Crick Institute (London), and former President of the Royal Society

2

Foreword

This book is about fifty scientists who left Hungary during the hundred years between the late 1800s and the late 1900s. The volume at hand is also a major historical document about emigration, one of the central topics of our age. It is well known that Hungary became a country of permanent emigration during the above mentioned century, and this trend continued even after the turn of the millennium. In the decade of 2010s, another five percent of the country’s population chose to work somewhere in the West, and sent two billion euros home every year to their family members. A great many of them will remain permanently abroad.

Emigration from Hungary is, indeed, continuous, and in certain periods especially significant: The turn of the 19th‒20th century, the interwar and immediate post-Second World War years, 1956, but also the 2010s, when— quoting the word of the outstanding interwar Hungarian poet, Attila József— millions of Hungarians “staggered out” (“kitántorgott”) of the country. Thomas Mann stated in 1941, “what is the meaning nowadays of such terms as homeland and foreign country, when homeland became foreign and foreign became homeland?” Indeed, for between two and two-and-a-half million Hungarian citizens, their homeland became foreign and they had to look for a foreign homeland where they could escape.

Emigration is a rule in economically less developed, poorer countries where landlessness is widespread, where sufficient jobs do not exist, and living standards are relatively low. Hungary was and is an economically moderately developed country. Both in 1900 and 1913, per capita income level—in nominal value—was hardly more than half (56%) of the average West European level. This measure of prosperity further declined during the entire 20th and the beginning of the 21st century: in 1950 it was only 48%, in 1990 less than 40%, and in 2018 only 29% of the average West European per capita GDP. The living

standard—since the price level was also lower—was somewhat higher than these numbers would suggest: close to half of the West. Lower income levels, lower living standards, less possibilities in life, create—as demographers call it—a “push effect” to emigrate, especially because the West, only a few hundred kilometers away, created a strong “pull effect.”

For scientists, however, the main problem was not their living standard, but their research possibilities and/or the political environment. The unwritten law is that poorer countries spend a much lower percentage of their lower income for research than the richer countries. This is clearly visible from the figures of the 2010s. Germany and Austria spent 3.2, the USA and Denmark 3.1, and Israel 4.9 percent of their GDP for research, compared to Hungary, which spent 1.4, Poland 1.3, Turkey 1.1, Russia 1, Slovakia 0.9, Bulgaria 0.7, and Romania 0.5 percent. Since the per capita GDP of the Eastern countries is only between half and one quarter of the Western level, a much smaller proportion of their GDP for research equals only a tiny fraction of the Western scientific research money. In other words, scholars in poorer countries had only extremely limited research possibilities compared to their Western colleagues. Research costs have become higher and higher every decade, so insufficient research budgets was one of the greatest “push effects” for them. The often intolerant, even hostile attitudes against their new scholarly ideas and work were just additional elements of the problem.

Indeed, the economic factor was only one of the causes of emigration, and for many who were pushed abroad not even the most important one. I quoted above Thomas Mann’s statement from 1941 defining the notion of “foreign homeland.” He found one in Switzerland, then in the United States, and then again in Switzerland. He did not emigrate from a less developed country, but from 1933 Germany where Hitler rose to power. Authoritarian regimes hate and purge, degrade and even kill people, suppress those who oppose the regime or those who belong to certain minorities which are blamed for all the country’s troubles. Many scientists were slandered as “enemies of their nations” and fled for political reasons.

In modern Hungarian history, this political “push factor” often became equally important and sometime more decisive than the economic one. Around the turn of the 19–20th centuries roughly half of the emigrants from Hungary belonged to disparaged ethnic minorities, such as Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, and others who, altogether, represented half of the population. The ruling Hungarian elite wanted to “magyarize” them, and the school system served this goal. Huge groups of these “second rate” ethnic citizens left Hungary. Another major

factor was a vicious anti-Semitism, clearly expressed by the founding of the Anti-Semitic Party in 1883, and one of Europe’s last blood libels in Tiszaeszlár in 1882–83. This atavistic hatred became a dominant political force in interwar Hungary, accelerated by a lost war, the frustration caused by the peace treaty that cut off two-thirds of the prewar territory, then revolutions and counter-revolutions. A democratic revolution in 1918 was followed by a coup and a shortlived communist regime in 1919, soon bloodily defeated by foreign intervention and a nationalist right-wing counter-revolution. Exalted nationalism and rightwing radicalism became dominant in the interwar regime that equated communism with Jews. In 1920, Hungary became the first country in Europe to enact an anti-Jewish legislation, the so called Numerus Clausus law, limiting the number of Jewish students at universities. Discrimination sharply increased during the 1930s, when the country became Hitler’s close ally. Several new anti-Jewish laws destroyed the living possibilities of Jews who represented five percent of the country’s population, followed by the Holocaust that killed half of them. Half of the remaining half left the country after the war.

The new historical turn, the sovietization of Hungary, also played an important role in the postwar emigration trends. Freedom was suppressed again, and a new type of persecution hit all those people who served the previous regime, opposed or criticized the new one, together with the relatively well-to-do people, including peasants with estates larger than 15 hectares. Even small-scale workshops and shops—virtually the entire economy—became state owned, thus the properties of significant layers of society were expropriated. A new type of first harsh, then, after 1956, milder form of authoritarian system ruled the country for more than forty years. It collapsed in 1989–1990, when democratic transformation began. However, soon after that, a populist-nationalist type of new autocratic regime emerged from 2010 with Viktor Orbán’s leadership.

In other words, Hungary, during its entire troubled modern history was dominated by autocratic systems which discriminated and oppressed certain layers of society. Five dramatic regime changes in one single life-time caused tremendous social trauma, especially because the new regimes often punished and discriminated against those who served the previous one. All these drove mass emigration during most of the last century up to now.

Among the millions of emigrants, there were tens of thousands of highly educated people, intellectuals, scholars, and scientists. Their number, of course, represents a small minority of emigrants. But their importance was much greater than their numbers. In the entire period, a tremendous brain-drain weakened, sometimes undermined the country.

The relative weakness of the country’s economy, the existing limitations of financial possibilities for research, together with the intolerant attitudes of oppressive authoritarian systems repeatedly pushed thousands of young independent-minded people, scholars, and future scholars abroad and in doing so decimated the intellectual and scholarly life of Hungary. This book covers the story of leading scientists. Similar works could also present similar stories of social scientists and artists, such as the social philosophers Karl Polányi and Oszkar Jászi; economic advisors of British governments Nicolas Kaldor and Thomas Balogh; Nobel laureate economist John Charles Harsanyi; Béla Bartók, a pioneer of 20th century music, world class conductors George Szell and Eugene Ormandy, the virtuoso violinist Joseph Szigeti, and thousands of others.

Reading this book automatically raises the question: what would have happened to those great talents and scientists if they remained in Hungary? Katalin Karikó, one of the inventors and main heroes of the anti-Covid vaccination, who left Hungary in 1985, and one of the personalities whose story is presented in this book, answered this question: “I would have become a mediocre, disgruntled researcher.” This highly interesting volume presents personal stories of emigrated scientists; many of whom faced possible disasters and suffering at the beginning of their careers. But exceptional talent and tremendous hard work in friendly environments led to great success in the end. Their stories provide significant historical lessons. The authors, at the end of the book, offer a brief summary of the lessons: “a society is to lose a great deal from being exclusionist and intolerant… a society is to benefit a great deal from being receptive and tolerant, integrating and welcoming.”

Professor Ivan T. Berend, UCLA, History Department Former President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Author of Economics and Politics of European Integration and A Century of Populist Demagogues

Introduction

“I would rather have roots than wings, but if I cannot have roots I shall use wings.”

Leo Szilard, 19541

“And when statesmen or others worry him [the scientist] too much, then he should leave with his possessions. With a firm and steadfast mind one should hold under all conditions, that everywhere the earth is below and the sky above, and to the energetic man, every region is his fatherland.”

Tycho Brahe, 15972

Preface

Of the many famous Hungarian scientists, most have acquired their fame outside Hungary. This book is about them: The Hungarian emigrant scientists, the reasons for their emigration, and their road to world fame. About fifty scientists are presented, so this is a sample rather than a comprehensive collection. Many of this number were Jewish, but not all. The selection represents a broad diversity as to the time of emigration and the fields of activities, but always staying within science and technological invention.

The motivation for this book is to show the contrast between two kinds of societies. One is a society—in this case, the Hungarian—that succumbs to political expediency and prejudice, or simply to negligence, and forces out talent. The other is an open society that gains by inclusiveness and tolerance. Examples are Great Britain and the United States. While it lasted (1918–1933), the Weimar Republic of Germany was another example.

The emigrant scientists included prominent contributors to mathematics, physics, chemistry, biomedicine, and technological innovation. There were Nobel laureates among them: Philipp Lenard, Albert Szent-Györgyi, George de Hevesy, Georg von Békésy, Eugene P. Wigner, Dennis Gabor, John Harsanyi, George Olah, and Avram Hershko.3 Another distinguished group is the

1 Bernard T. Feld and Gertrude Weiss Szilard, eds., The Collected Works of Leo Szilard: Scientific Papers (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1972), 14.

2 Alan L. Mackay, A Dictionary of Scientific Quotations (Bristol: Adam Hilger/IOP Publishing, 1991), 38.

3 In addition to these Nobel laureates, there are other Nobel science laureates who are claimed to be Hungarian, having Hungarian names: Robert Bárány (1876–1936) and Richard A. Zsigmondy

five so-called Martians of Science,4 viz., Theodore von Kármán, Leo Szilard, Eugene P. Wigner, John von Neumann, and Edward Teller. They contributed considerably to the defense of the United States and the Free World during World War II and the Cold War, even at the risk of their careers in science.

A few more names indicate how extraordinary some of the individuals in our selection were. Michael Polanyi was a great physical chemist turned philosopher, best known for his trailblazing book in epistemology, Personal Knowledge. He figures here because of his greatness in science. The writer Arthur Koestler contributed to the understanding of the nature of scientific discovery—and this is why he figures in this volume. His political novel, Darkness at Noon, would qualify as a war effort—making his pen equivalent to the most devastating bombs in the struggle for democracy. The biologist Ervin Bauer pioneered theoretical biology. He emigrated to the Soviet Union and was executed in the 1930s on trumped up charges during Joseph V. Stalin’s Great Terror. The mathematician Paul Erdős has become a folk hero—something unprecedented in his profession. The chemical engineer Andy Grove became the uncrowned king of American computer technology and TIME magazine’s 1997 “Man of the Year.” The software engineer Charles Simonyi became a private citizen‒space traveler. The research chemist Joseph Nagyvary used his science—his chemistry, indeed—to understand the unique riches of the sound of the Stradivari violin. The biochemist Katalin Karikó was a key person in creating the (messenger-RNA-based) vaccine against Covid-19.

The emigrants themselves formulated the reason for their departures in a variety of ways. Here we mention two examples. John von Neumann looked back thirty years after his departure from Hungary and a quarter century after his arrival in the United States. The occasion was his confirmation hearing on March 8, 1955, at the Senate of the United States, for membership of the Atomic Energy Commission. He said: “the main reason was partly because conditions in Hungary were rather limited, and I thought the thing I was doing had a better field in America and to a considerable extent because I was much more in sympathy with the institutions of America; and, lastly, because I expected World (1865–1929). The Báránys were an old Jewish family in Hungary, but Robert Bárány’s father moved to Vienna one year before his son’s birth. Robert Bárány eventually moved to Sweden where his descendants still spell their surname in the Hungarian way, Bárány. Bárány and Zsigmondy are not included in our discussion because they were not born, nor ever lived in Hungary, hence could not have emigrated from Hungary. The book about the Nobel Prize by the Nobel Foundation lists Bárány as Austrian and Zsigmondy as German. Nobel Foundation, ed., Nobel: The Man and His Prizes (Stockholm: Sohlmans Förlag, 1950), 605–607.

4 The origin of the label is described in the Introduction to Part 1.

War II, and I was apprehensive that Hungary would be on the Nazi side, and I didn’t want to be caught dead on that side.”5 And here is how Andy Grove summarized over four decades after his departure his motivation for leaving Hungary: “My life in Hungary was—to understate it—a negative experience.”6

Over the past one hundred plus years there have been waves of emigration of established and future scientists. Each of the subsequent political regimes generated its own wave. First, we present a concise chronology of Hungarian history focusing on drivers of the waves of emigration, followed by the list of the waves.

Concise Chronology

1867 Compromise between Hungary and the Habsburgs, followed by the emancipation of the Jews

1867–1918 Austria-Hungary, unprecedented growth and modernization 1914–1918 World War I

1918, October, Bourgeois democratic revolution 1919, March‒August, Communist dictatorship and terror, followed by a ruthless extreme-right (“white”) terror 1920, June 4, “Peace Treaty of Trianon”7 in which historical Hungary lost two thirds of its area and close to two-thirds of its population, but gained independence 1920–1944 “Horthy regime,” Nicholas Horthy, as “Regent,” head of state 1920 Numerus Clausus anti-Jewish law (the Latin expression means “closed number”). The law severely limited the number of Jewish students in Hungarian higher education 1938, 1939, 1941 First, Second, and Third “anti-Jewish laws” 1944, March 19, Germany occupies Hungary 1944, April‒July, Concentration and deportation of Jews from the provinces to Auschwitz

5 Abraham Pais, The Genius of Science: A Portrait Gallery of Twentieth-Century Physicists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 190.

6 In a speech before the Association of America’s Holocaust Museum in Chicago, September 28, 2003; quoted in Richard S. Tedlow, Andy Grove: The Life and Times of an American (New York: Portfolio, 2006), 1.

7 The “Peace Treaty of Trianon” or the “Trianon Treaty,” often referred to as “Trianon,” is not an official name. It was one of the peace treaties concluded following World War I in the framework of the Paris Peace Conference. This peace treaty with Hungary was signed by most of the Allies and Hungary in the Grand Trianon Palace in Versailles on June 4, 1920, hence the name, “Trianon Treaty.”

1944, October 15, Arrow Cross (Hungarian Nazis) takeover followed by a reign of terror, turning Budapest into an extermination camp for Jews

1945, April, Liberation of Hungary by the Red Army; Soviet occupation begins

1945–1947 Democratic multi-party system

1948–1989 Communist dictatorship

1956, October 23‒November 4, anti-Soviet Revolution, followed by ruthless suppression

1989–1990 Multi-party system and democratic elections reintroduced 2010‒ continuous disassembly of democratic institutions, autocracy

Waves of Emigration

Wave 1: Early 1920s, Fleeing

Wave 2: Late 1930s, Last-minute escapes

Wave 3: 1945–1947, Post-war and pre-Soviet trauma

Wave 4: 1956, Suppressed revolution

Wave 5: 1957–1989, Escape from “Paradise”

There has been continuous emigration since the political changes of 1989–1990, which signaled yet another attempt at democratic governance. Unfortunately, it failed. Another autocratic regime has developed since 2010 with one significant difference from the pre-1990 time: a departure today does not carry the weight of finality as it used to, due to open borders and membership in the European Union. Return is possible even if few exercise it. This is why we hesitate calling the post-1990 departures “emigration.”

During the past one hundred years, each regime found it advantageous to see the departure of independent individuals. There have been limited attempts to bring back some of the emigrants, but with little success. Large scale success could not have been expected because the underlying reasons for emigration did not change. As for political interference in the life of scientists or the lack thereof, we give two international examples.

The United Kingdom has been in the forefront of scientific and innovative progress for centuries. Political affiliation has played very little role in the appointment of professors and the elections of the members of national academies. Those gifted and willing to work, thrived. There were a few exceptions at the time of the Restoration, in the 1660s, when monarchy was being reinstated

and the differences between royalists and parliamentarians moved into spheres of society that should have been nonpartisan. This was an exception and it was three and a half centuries ago.8 Albert Einstein noted something similar with respect to the comparison of German and English conditions, and, remarkably, this he did as early as the time of the Weimar Republic: “Whereas in Germany, in general, the judgment of my theory depended upon the political orientation of the newspapers, the English scientists’ attitude has proven that their sense of objectivity cannot be muddled by political viewpoints.”9

The closer a political system is to totalitarianism, the more direct and devastating its political interference in all spheres of life, including science, may be. When in 1933 Max Planck warned Adolf Hitler about the consequences of forcing the Jewish scientists out of Germany, the Nazi dictator retorted: “Our national policies will not be revoked or modified, even for scientists. If the dismissal of Jewish scientists means the annihilation of contemporary German science, then we shall do without science for a few years.”10

In 1920, Hungarian legislation drastically limited the number of Jewish students allowed admission to university education—this was the infamous Numerus Clausus (closed number) law, the first anti-Semitic legislation in postWorld War I Europe. Nicholas Horthy’s regime not only elevated anti-Semitism to legalized official governmental policy, it introduced the racial principle into anti-Semitism. This fostered the emigration of scientists and budding scientists. There was no “Hungarian Max Planck” to warn Horthy of the danger of losing such a substantial intellectual capacity. But there was international criticism of this legislation. In this connection, Count Kuno Klebelsberg,11 the architect of Hungarian cultural life and education, made this cynical statement in 1924 in the Hungarian Parliament: “Give us back the old Greater

8 Before our notion might be construed as an idealization of all aspects of British scientific life, we mention as a negative example the discrimination on account of sexual orientation that used to influence participants in scientific life. Yet another point could be made about the underrepresentation of women in British scientific life, similar to other countries. The point we stress is the absence of political interference. See I. Hargittai and M. Hargittai, Science in London: A Guide to Memorials (Springer Nature, 2021).

9 Albert Einstein, Jüdische Rundschau, June 21, 1921; quoted in The Expanded Quotable Einstein, comp. and ed. Alice Calaprice (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 282.

10 E.Y. Hartshorne, The German Universities and National Socialism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1937), 112.

11 Kuno Klebelsberg (1875–1932) had a broad vision for the dominance of Hungary in the region through Hungarian “cultural superiority.” He aimed at bringing back some of the talent that had left the country, excluding though the Jewish expatriates.

Hungary and then we will be able to revoke numerus clausus.”12 He thus linked the losses due to the Trianon Treaty to the Numerus Clausus law. To him and to the Horthy regime, named after the autocratic and anti-Semitic head of state, eliminating the reasons for the exodus of Jewish intellectuals would be a favor to the West rather than to Hungary. For such a “favor,” Hungary should be entitled compensation. Klebelsberg’s stand was no less cynical than Hitler’s response to Max Planck’s protest.

The Numerus Clausus law had broad implications.13 It considered the Jews as a separate nationality and listed them among Germans, Slovaks, Romanians, etc., according to mother tongues, although the mother tongue of the Jews in Hungary was Hungarian. It established a Jewish quota of 6% in higher education on the basis of the proportion of the Jews in society.14 It was a prelude to ever stricter restrictions in other spheres of life, including economic life, in the late 1930s. The Numerus Clausus law was not the only anti-Semitic policy introduced in the 1920s; rather, it was the only openly acknowledged and legislated discrimination. In 1928, upon continuous international protest, the law was reformulated and the Jewish quota was replaced by the so-called occupational quota, based on the occupation of the applicant’s father. The disadvantaged occupations were those in which Jews were engaged in relatively large proportions. As this was merely a cosmetic change, in the 1930s the situation further deteriorated with regards the Jewish possibilities in higher education. Some would believe the false notion that after 1928 the discrimination diminished; actually, the opposite happened as the entire Horthy era was infested with anti-Semitic discrimination. Another false notion is that the policy of anti-Semitism in Hungary was a consequence of the imposition of Nazi Germany. As the story of the Numerus Clausus law shows, it predated the Nazi takeover of Germany by a dozen years. The current autocratic regime in Hungary (as of 2021) is a great proponent of these false notions because it considers the Horthy regime of the interwar period as its model to emulate in many respects.

12 Quoted in Mária M. Kovács, Törvénytől sújtva: A numerus clausus Magyarországon, 1920–1945 [Disenfranchised by law: Numerus clausus in Hungary, 1920–1945] (Budapest: Napvilág, 2012), 50. From Nemzetgyűlési Napló, 1922–1926. XXIV. kötet, 295. ülés, 320. old. (1924. június 4).

13 Mária M. Kovács, “Disenfranchised by Law. The ‘Numerus Clausus’ in Hungary 1920–1945,” S.I.M.O.N.—Shoah: Intervention. Methods. Documentation 1, no. 2 (2014): 136–143.

14 In the United States during the same years, a Jewish quota was imposed at some of the best American universities. However, this should not be considered an excuse for the Numerus Clausus law legislated in 1920 in Hungary. As shameful as the institution of the Jewish quota was at the “Ivy League” schools, it was not a nationwide restriction by state or federal authorities, and it did not prevent Jewish applicants from gaining admittance to other institutions of higher education.

To be “exiled” implies forced departure, and to call the departure of the scientists in our sample forced may appear provocative. To be sure, some among them were truly forced out of the country, whereas others felt that circumstances made their staying impossible. Cases varied, so this general term is imprecise. However, after examining the cases discussed in this book, we find the term “exiled” to be the most fitting one to describe the common denominator of the motivation among the emigrants to leave Hungary.

While a sample of fifty is insufficient for statistically meaningful conclusions, it is large enough to give an impression of the significance of emigration for Hungary, on the one hand, and for world science, on the other. Intuitively, one should expect that such a large-scale emigration of scientists from a small country would bring considerable harm to the country, while still hardly being noticed internationally. The reality is the opposite. Had the emigrant scientists stayed in Hungary, most of them might have been murdered. Had they not been murdered but been harassed, they might have ended up with far less achievement than they did as immigrants. As it turns out, they contributed to world science to a remarkable extent. At this point we hasten to stress that the Horthy regime was not the only one that squandered talent during the past one hundred years. The forty-year long communist regime also wasted human collateral and talent. All political systems in Hungary—every consecutive political system— produced emigrants. Every political system considered the supporters or perceived supporters of the preceding political system to be enemies. This parochialism found expression, for example, in restrictions on who could and who could not teach at a university.

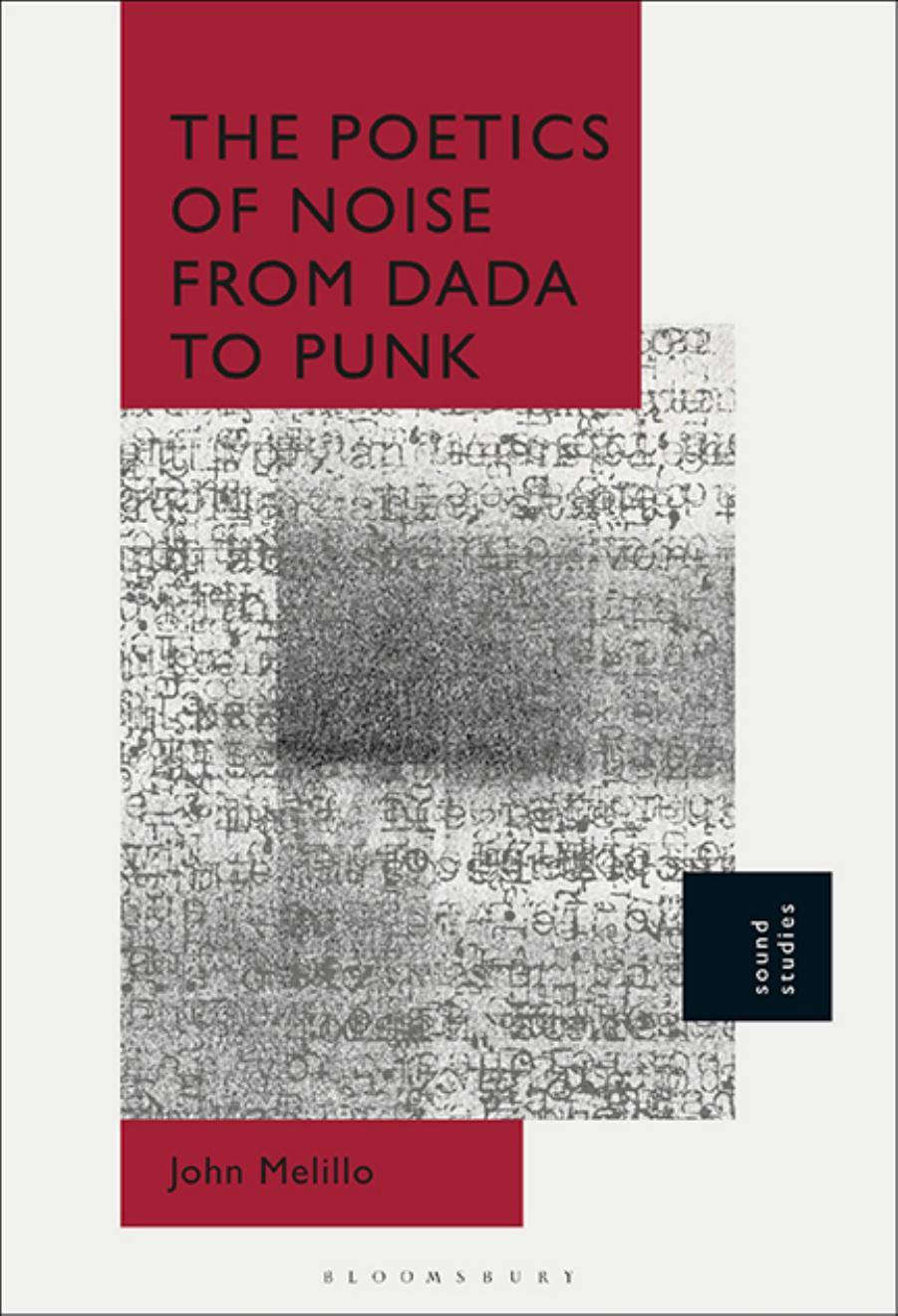

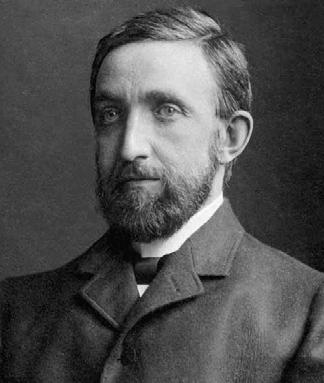

The walkways on the campus of Budapest University of Technology and Economics are lined by busts of former professors. Photograph by the authors.

Walking around the beautiful campus of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, one feels immersed in history. The walkways are lined with busts of renowned professors whose names are displayed on the plinths of the busts. But when one looks up their life stories, the sad truth emerges that only a few of them completed their tenure through retirement as professors. Some lived as emigrés, but even more were stripped of their professorships and the possibility of teaching at the peak of their academic careers. The most frequent reason for losing that privilege was participation (or perceived participation) in the 1919 communist dictatorship or in the 1956 anti-Soviet Revolution.

This was the fate of Gabor Fodor, formerly of the University of Szeged. He was one of the most famous emigrant professors who had been stripped of his right to teach in Hungary because of his activities in the 1956 Revolution. A foreign visitor— who happened to be a Nobel laureate and who knew Fodor— referred to Fodor’s fate in a conversation with the secretary general of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, by saying that Hungary must be a very rich country. The outside observer implied that the treatment accorded to Fodor was shameless squandering.

To be declared enemies of the homeland is a melancholy fate, yet individually these departures, especially in hindsight, did not turn out to be sad. Leo Szilard was leaving on a Danube steamer at Christmas time in December 1919. An old visiting Hungarian emigrant sensed the sadness in Szilard and felt compelled to cheer him up: “As long as you live you’ll remember this as the happiest day of your life.”15 Szilard knew that he was leaving for good; he never looked back. The overwhelming majority of emigrants left for good, save, possibly, for brief visits.

To settle in a new country may be a difficult exercise, but it is also stimulating and fosters enhanced performance. One has to prove one’s worth to the new environment. One brings new experiences that may help in making new observations, new viewpoints, and new approaches for the new environment. Faced by new challenges, the emigré must summon the grit and determination to meet them.

A comparison of Hungarian daily functioning and that in the receiving country sheds some light on the reasons for the outstanding performance of many Hungarian immigrants. The biophysicist George von Békésy and the biochemist Katalin Karikó left Hungary with a difference of forty years between

15 William Lanouette with Bela Silard, Genius in the Shadows: A Biography of Leo Szilard—The Man Behind the Bomb (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992), 50–51. Bela Silard (1900–1994), Leo Szilard’s brother, was an electrical engineer and inventor. He dropped the “z” from his surname upon immigration to the United States in 1938.

them, yet they came to the same conclusion. Both attested that living in Hungary is an every-day struggle for survival, whereas elsewhere, the practice of science comes without additional struggle, without keeping alert and being on one’s guard all the time. The spared efforts and energy, once the emigrant transforms into an immigrant, become the source of enhanced performance, especially if combined with talent.

The majority of Hungarian immigrant scientists, by the time they had arrived in Great Britain or the United States, had already learned from the experience of having been an immigrant in Germany. That was their advantage as compared with, for example, German, Italian, or other West-European immigrants. In addition, the Jewish-Hungarian immigrants had had enhanced experience in their Hungarian lives, not unlike an immigrant in a new home country, because of the anti-Semitic environment in Hungary. This experience was their added “advantage” when starting their lives in their new home country.

This experience found expression in the words of prominent emigrés, such as John von Neumann: “… an external pressure on the whole society of this part of Central Europe, a feeling of extreme insecurity in the individuals, and the necessity to produce the unusual or else face extinction.”16 Edward Teller: “have to be better, much better than anyone else.” Dennis Gabor: “Innovate or die!”17 One generation later, George Klein expressed the same: “… the middle-class Jews with this kind of tradition got the drive and the ambition with mother’s milk. You either became successful or you were going to end up in the gutter.”18 A film critic characterized succinctly the situation of the Jews in Hungary as “strangers at home” in his critique of the film Sunshine. It is about the story of generations of a family over a hundred years, the same period as that of our discussion.19 Prior to the last one hundred years, the emigration of scientists and innovators from Hungary was not common for two reasons. One was that there were not many scientists, and the other was that the westward mobility of scientists was part of a two-way motion. At the time of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, departure to the West for many meant a sojourn in Germany for completing or

16 Quoted in Stanislaw M. Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1991 edition), 111.

17 Both Teller and Gabor are quoted in Donald Michie, “The Genius Phenomenon,” Nature 292, no. 5818 (July 2, 1981): 91–92; actual quote, 92.

18 Istvan Hargittai, Candid Science II: Conversations with Famous Biomedical Scientists, ed. Magdolna Hargittai (London: Imperial College Press, 2002), Chapter 27, “George Klein,” 416–441, actual quote, 425.

19 Istvan Deak, “Strangers at Home,” The New York Review of Books (July 20, 2000). This is about the film Sunshine, directed by Istvan Szabo.

improving training, gathering professional experience, or learning about the latest advances in medicine, before returning home. National borders were not a hindrance, and the Hungarian intellectuals spoke German, which used to be the language-passport for everyone in Central Europe.

Fin de siècle Hungary, especially the capital city, Budapest, was fast developing, considering its architecture, transportation, industry, and education. Part of the modernization of the country—being a part of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy under the Habsburgs—was the emancipation of the Jews who then flourished in all those professions from which they had been excluded: science, education, medicine, engineering, law, commerce, finance, and to a lesser degree: politics and legislation, the judiciary, the army, and the civil service.

The education system underwent modernization. In particular, strong secondary schools developed, including both denominational and secular institutions that could rival any of the best systems in the world. The Stockholm exhibition on the occasion of the Nobel Prize Centennial singled out this national characteristic as the root of Hungarian excellence in science.20 It was the Budapest gimnázium21—the backbone of secondary education— that represented the venues of creativity. Mór (Maurice) Kármán, the father of one of the great future emigrants, Theodore von Kármán, developed the secular Model Gimnázium. He based instruction on practical examples so that the pupils saw the connections between the seemingly abstract ideas and their everyday life. Kármán’s achievement served, indeed, as a model school, and was on the level of the long established denominational high schools. All these high schools produced outstanding contributors to world science and culture.

Science writers often single out the Lutheran Gimnázium in Budapest as the high school where the famous Hungarian scientists studied. In reality, a number of future greats attended quite a number of excellent high schools in Budapest and elsewhere in the country. Teaching at a gimnázium was a well-paid job of high prestige at the time; these teachers were accomplished and, usually, male. A few examples of high schools—gimnáziums—which the future emigrants attended include:

20 Ulf Larsson, ed., Cultures of Creativity: The Centennial Exhibition of the Nobel Prize, trans. Daniel M. Olson (Canton, MA: Science History Publications/USA & The Nobel Museum, 2001), 166–167.

21 We purposely use the Hungarian spelling, gimnázium, which came to Hungarian from the Greek via the Latin gymnasium, meaning an indoor space for exercise without cloth. The gimnázium in Hungary, with proper clothing of course, is the secondary school—high school—that prepares for higher education, that is, universities and colleges.

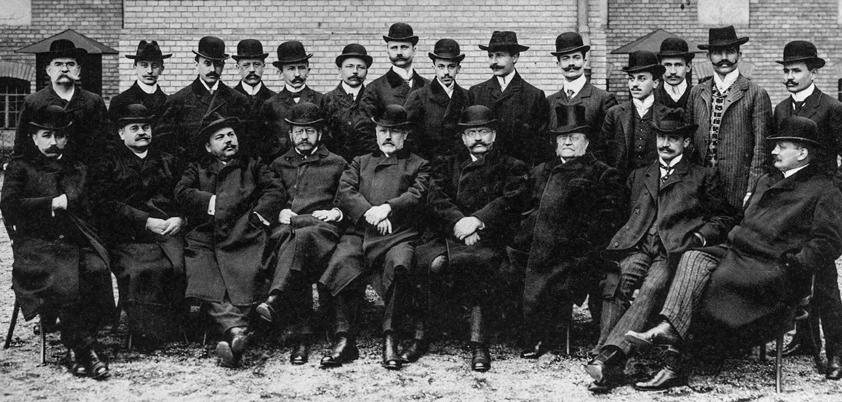

Stern-looking all-male faculty of the Lutheran Gimnázium in Budapest around 1900. Courtesy of the Lutheran Gimnázium, Budapest. László Rátz, the math teacher of Eugene P. Wigner and John von Neumann, sits at the right edge of the picture

Berzsenyi Gimnázium (Dennis Gabor, George Pólya, Georg Klein)

Calvinist Gimnázium (Albert Szent-Györgyi)

Main Real Gimnázium of District 6 (Arthur Koestler, Leo Szilard)

Model Gimnázium (Theodore von Kármán, Nicholas Kurti, Michael Polanyi, Edward Teller, Peter Lax, Gabor Somorjai)

Lutheran Gimnázium (John von Neumann, Eugene P. Wigner, John Harsanyi)

Piarist Gimnázium (George de Hevesy, George A. Olah)

The pharmacist turned PhD philosopher turned PhD mathematical economist John Harsanyi attended the Lutheran Gimnázium. There were sixty boys in the classroom (huge according to present-day ideas about ideal class size). All were intelligent and some even super intelligent. The student body was at least as important to Harsanyi as having excellent teachers. The boys had sizzling discussions about philosophy, politics, everything. Never again in his life did Harsanyi have such an enriching experience of being surrounded by sixty intelligent people.22 His words help understand why these outstanding pupils spent the 8 years of high school without trying to jump ahead.

22 István Magyari Beck, Száműzött értékek: Beszélgetések az alkotó munkáról [Exiled values: Conversations about creative work] (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1989). Conversation with John Harsanyi, 21–46.

The mandatory high school curricula could be augmented by challenging extracurricular activities, among them the self-improvement circles, the national competitions, and the high-school monthly mathematical magazine. The self-improvement circles of voluntary membership had a certain degree of autonomy. There were such circles in different areas, such as literature, science, politics, and others. An elected senior student president chaired their meetings in the presence of a designated teacher. The students gave presentations, often followed by heated debates. Eugene P. Wigner was a member of both the science circle and the literary circle. So was Endre A. Balazs, a generation later at another gimnázium, where he gave talks and conducted discussions on a plethora of topics, from atomic physics to the play The Tragedy of Man by Imre Madách. It was also during his high school time that Leo Szilard became fond of Madách’s Tragedy.

Participation in solving the problems of the high-school mathematical monthly, Középiskolai Matematikai Lapok (KöMaL), was a good preparation for the national competitions in mathematics. This magazine is worthy of special mention among the factors that kept the high school students busy. It was founded by a high-school math teacher, Dániel Arany, who started publishing it in 1894.23 It has been very popular ever since. It presents problems, communicates their solutions, and lists the names of successful collectors of solution points in descending order. Many of the later renowned mathematicians began as top names on these lists. But the lists are long and bring pride not only to a select few but to many of the aspiring, which enhances the magazine’s popularity.24 Eventually it incorporated physics, and lately there is an informatics section in it as well.

Some teachers supplied additional challenges when they noticed a need for them. László Rátz of the Lutheran Gimnázium gave additional instructions in mathematics to von Neumann. When Rátz exhausted his own resources, he arranged that university level mathematicians take over. Rátz gave mathematical books to Wigner as additional reading. According to the self-deprecating Wigner, this was a manifestation of Rátz’s pedagogical acumen as the teacher recognized the difference in their levels.

23 Dániel Arany (1863–1945) edited the magazine for a few years, and then passed the editorship over to László Rátz. After 1919, Arany was forced into retirement for alleged participation in the shortlived communist dictatorship. He never found employment again. In 1944, the Jewish Arany and his wife were locked in the Budapest ghetto. They did not survive and were buried in a mass grave at the Main Synagogue.

24 Both present authors were enthusiastic problem solvers in their respective times.

Of course, a bird’s eye view may be different from a worm’s eye view. Neither Leo Szilard nor Edward Teller was happy with the instructions they received in their respective high schools. They found them obsolete. Peter Lax’s observations about his high school experiences are instructive. First he attended the Model in Budapest, then, following emigration, he became a pupil of the Stuyvesant High School, one of New York’s preeminent secondary schools. His comparison has relevance, beyond these two particular schools, about the two systems of education. Lax was a good student at the Model Gimnázium, but even he was petrified by his teachers; he was afraid of them. At the Stuyvesant High School, the teachers were friends to the students. However, according to Lax, it is debatable which type of high school prepared the students better for life. Such a prolonged adolescence is an explicit goal of the American high school whereas the Hungarian high school considers graduation a border between School and Life. It might sound cynical, but the Hungarian school provided a better preparation—Lax argued. It made youth recognize who the enemies were—the teachers. Coexisting with them was a perpetual struggle, so students learned to fight for inclusion as a true preparation for Life.

As for the universities, the Budapest Technical University, the University of Budapest, including its medical school, the University of Szeged, and other venues, produced outstanding graduates.25 This was due, however, to the impact of individual professors rather than the institutions as a whole. Leopold Fejér (1880–1959) in mathematics was a shining example. His teaching covered much more than the subject itself. He inculcated his pupils with an admiration of mathematics and a realization of the surprises this subject presented for its devotees at every corner. He had many pupils that became professors of mathematics abroad.26 Of the most famous scientists, only von Kármán, Szent-Györgyi, and Olah graduated from Budapest universities. Hevesy, Szilard, Gabor, Wigner, and Teller spent only a few semesters, while von Neumann earned his doctorate at the University of Budapest without attending lectures.

We have described five waves of emigration over the past one hundred years. However, we start with two cases that preceded them and that were not part of a wave, any wave of intellectuals, that is. One, a future Nobel laureate physicist,

25 All of them have gone through name changes and organizational changes. Today, the principal successor institutions are the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Eötvös Loránd University, Semmelweis University, and (once again) the University of Szeged.

26 László Fejes Tóth (1905–2005) was an exception among Fejér’s disciples. He was offered a tenured professorship at the University of Zurich. This happened under the communist regime, and he was not permitted to go (I. Hargittai, “Fejes Tóth László.” Magyar Tudomány 166, no. 3 (2005): 318–324).

Philipp Lenard, was unique. The other, a gifted car designer, Joseph Galamb, could be taken as representative of the technical personnel who left Hungary in search of better jobs. There was mass emigration from Hungary even during the so-called happy peace time (1867–1914). In the early 1900s, millions left Hungary for America, mostly unskilled people for work in agriculture.

Even the fast developing industry in fin de siècle Hungary could not absorb all the available technically skilled people. Industry was not just being modernized, it was to be modern, second to none, because it was being created “from scratch.” The railways and railway stations, electrified railways, telephone exchange centers, were not only among the most modern, but their engineers were in demand elsewhere in Europe. Budapest boasted the first metro line of continental Europe, the second one in the world (London was the first), and there were innovators in motor technology as well. This, however, did not include cars—there was no auto-industry in Hungary. Although entrepreneurs initially moved to Germany with such a purpose, the American automotive industry subsequently attracted them to the United States.

The stories of the physicist Philipp Lenard and the engineer Joseph Galamb are expanded upon following the Introduction.

We conclude with a personal note. One of us (IH) has met and had substantial interaction with quite a number of the heroes of this book: Endre A. Balazs, Laszlo Bito, György Buzsaki, Lars Ernster, Árpád Furka, Avram Hershko, Olga Kennard, Gyorgy Kepes, Georg and Eva Klein, Nicholas Kurti, Peter D. Lax, George A. Olah, Michael Polanyi, Gabor Somorjai, Valentine Telegdi, Edward Teller, Laszlo Tisza, and Eugene P. Wigner. With some, IH recorded and published conversations. With a few more, in addition to those listed here, there were cursory meetings. Personal acquaintance did not influence our choice of who is in this book, but this multitude of human connections has added a pleasant glow to working on this project.