Chemistry and Materials Science Yann

Garcia

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/mossbauer-spectroscopy-applications-in-chemistry-a nd-materials-science-yann-garcia/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Spectroscopy of Lanthanide Doped Oxide Materials Dhoble

https://ebookmass.com/product/spectroscopy-of-lanthanide-dopedoxide-materials-dhoble/

Chemistry of Functional Materials Surfaces and Interfaces: Fundamentals and Applications Andrei Honciuc

https://ebookmass.com/product/chemistry-of-functional-materialssurfaces-and-interfaces-fundamentals-and-applications-andreihonciuc/

Polymer science and innovative applications materials, techniques, and future developments Deepalekshmi Ponnamma

https://ebookmass.com/product/polymer-science-and-innovativeapplications-materials-techniques-and-future-developmentsdeepalekshmi-ponnamma/

Materials

for Supercapacitor Applications 1st

M. Aulice Scibioh

Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/materials-for-supercapacitorapplications-1st-edition-m-aulice-scibioh/

Actuators and Their Applications: Fundamentals, Principles, Materials, and Emerging Technologies

Abdullah M. Asiri

https://ebookmass.com/product/actuators-and-their-applicationsfundamentals-principles-materials-and-emerging-technologiesabdullah-m-asiri/

Vibrational Spectroscopy Applications in Biomedical, Pharmaceutical and Food Sciences 1st Edition Andrei A. Bunaciu

https://ebookmass.com/product/vibrational-spectroscopyapplications-in-biomedical-pharmaceutical-and-food-sciences-1stedition-andrei-a-bunaciu/

Hazardous and Trace Materials in Soil and Plants M.

Naeem

https://ebookmass.com/product/hazardous-and-trace-materials-insoil-and-plants-m-naeem/

An Introduction to Materials and Chemistry: Book 1 (Science for Conservators) 3rd Edition Joyce H. Townsend

https://ebookmass.com/product/an-introduction-to-materials-andchemistry-book-1-science-for-conservators-3rd-edition-joyce-htownsend/

Spectroscopy and Dynamics of Single Molecules: Methods and Applications Carey Johnson (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/spectroscopy-and-dynamics-ofsingle-molecules-methods-and-applications-carey-johnson-editor/

MössbauerSpectroscopy

MössbauerSpectroscopy

ApplicationsinChemistryandMaterialsScience

EditedbyYannGarcia,JunhuWang,andTaoZhang

Editors

Prof.YannGarcia UniversitéCatholiquedeLouvain InstituteofCondensedMatterand Nanosciences PlaceLouisPasteur1 1348Louvain-la-Neuve Belgium

Prof.JunhuWang

MössbauerEffectDataCenter(MEDC) DalianInstituteofChemical Physics(DICP) ChineseAcademyofSciences 457ZhongshanRoad 116023Dalian China

Prof.TaoZhang

MössbauerEffectDataCenter(MEDC) DalianInstituteofChemical Physics(DICP) ChineseAcademyofSciences 457ZhongshanRoad 116023Dalian China

CoverImage: CourtesyofNorimichi Kojima

Allbookspublishedby WILEY-VCH arecarefully produced.Nevertheless,authors,editors,and publisherdonotwarranttheinformation containedinthesebooks,includingthisbook, tobefreeoferrors.Readersareadvisedtokeep inmindthatstatements,data,illustrations, proceduraldetailsorotheritemsmay inadvertentlybeinaccurate.

LibraryofCongressCardNo.: appliedfor BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData Acataloguerecordforthisbookisavailable fromtheBritishLibrary.

Bibliographicinformationpublishedby theDeutscheNationalbibliothek TheDeutscheNationalbibliotheklists thispublicationintheDeutsche Nationalbibliografie;detailedbibliographic dataareavailableontheInternetat <http://dnb.d-nb.de>

©2024WILEY-VCHGmbH,Boschstr.12, 69469Weinheim,Germany

Allrightsreserved(includingthoseof translationintootherlanguages).Nopartof thisbookmaybereproducedinanyform–by photoprinting,microfilm,oranyother means–nortransmittedortranslatedintoa machinelanguagewithoutwrittenpermission fromthepublishers.Registerednames, trademarks,etc.usedinthisbook,evenwhen notspecificallymarkedassuch,arenottobe consideredunprotectedbylaw.

PrintISBN: 978-3-527-34691-2

ePDFISBN: 978-3-527-82494-6

ePubISBN: 978-3-527-82493-9

oBookISBN: 978-3-527-82495-3

Typesetting Straive,Chennai,India

Contents

Preface xi

1ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopytoEnergy Materials 1

Pierre-EmmanuelLippens,Jean-ClaudeJumas,andJosetteOlivier-Fourcade

1.1Introduction 1

1.2MössbauerSpectroscopyforLi-ionandNa-ionBatteries 2

1.2.1CharacterizationofElectrodeMaterialsandElectrochemical Reactions 2

1.2.2Tin-BasedNegativeElectrodeMaterialsforLi-ionBatteries 3

1.2.2.1ElectrochemicalReactionsofLithiumwithTin 3

1.2.2.2TinOxides 7

1.2.2.3TinBorophosphates 10

1.2.2.4Tin-BasedIntermetallics 13

1.2.3Iron-BasedElectrodeMaterials 17

1.2.3.1LiFePO4 asPositiveElectrodeMaterialforLi-ionBatteries 17

1.2.3.2Fe1.19 PO4 (OH)0.57 (H2 O)0.43 /CasPositiveElectrodeMaterialforLi-ion Batteries 18

1.2.3.3Na1.5 Fe0.5 Ti1.5 (PO4 )3 /CasElectrodeMaterialforNa-ionBatteries 19

1.3MössbauerSpectroscopyofTin-BasedCatalysts 21

1.3.1ReformingCatalysis 21

1.3.2RedoxPropertiesofPt-SnBasedCatalysts 22

1.3.3TrimetallicPt-Sn-InBasedCatalysts 24

1.4Conclusion 26 Acknowledgments 27 References 27

2MössbauerSpectralStudiesofIronPhosphateContaining MineralsandCompounds 33

GaryJ.LongandFernandeGrandjean

2.1Introduction 33

2.2ThermodynamicPropertiesofIronPhosphateContaining Compounds 34

2.3RoomTemperatureMössbauerSpectraofIronPhosphateContaining Minerals 37

2.4AnalysisofMagneticallyOrderedMössbauerSpectra 50

2.5StructuralandThermodynamicPropertiesofthePolymorphsof FePO4 53

2.5.1PolymorphsofFePO4 53

2.6MössbauerSpectraof �� -FePO4 55

2.7MagneticStructureof �� -FePO4 ,ObtainedbyMössbauer Spectroscopy 57

2.7.1MagneticStructureof �� -FePO4 57

2.8TemperatureDependenceofthe �� -FePO4 StructureTiltAngle 60

2.9MössbauerSpectralStudiesonMetastablePolymorphsofFePO4 62

2.9.1CrystallographicStructuresofTwoPolymorphsofFePO4 ⋅2H2 O 62

2.9.2PreparationandCrystallographicStructuresoftheTwoPolymorphs, �� -FePO4 and �� -FePO4 62

2.9.3MössbauerSpectralStudiesofFePO4 MetastablePolymorphs 64

2.9.4PreparationandMössbauerSpectraofSyntheticHeterosite, (Fe,Mn)PO4 67

2.9.5FitsoftheMagneticMössbauerSpectraof �� -Fe0.9 Mn0.1 PO4 68

2.10MössbauerSpectralStudiesofVariousIronPhosphateCompounds 73

2.10.1MössbauerSpectralPropertiesof �� -Fe2 (PO4 )O 74

2.10.2MössbauerSpectralPropertiesofFe3 (PO4 )O3 79

2.10.3PreparationandStructuralPropertiesofFe9 (PO4 )O8 80

2.10.4MössbauerSpectralPropertiesofFe9 (PO4 )O8 81 Acknowledgments 85 ReferencesandNotes 85

3MössbauerSpectroscopicInvestigationofFe-Based Silicides 93

XiaoChen,JunhuWang,andChanghaiLiang

3.1Introduction 93

3.2MössbauerSpectroscopicInvestigationofIronSilicidesPreparedBy MechanicalAlloyingandHeatTreatment 95

3.3MössbauerSpectraofIronSilicideonSilicaPreparedbyPyrolysisof Ferrocene-PolydimethylsilaneComposites 99

3.4SynthesisandMössbauerSpectraofIronSilicidesby Temperature-ProgrammedSilicification 102

3.5MössbauerSpectroscopicInvestigationofDopedIronSilicides 104

3.6ConclusionandPerspective 107 References 108

4MössbauerSpectroscopyofCatalysts 113 KárolyLázár

4.1Introduction 113

4.2PrinciplesoftheMössbauerEffectandOutlookofItsApplicationfor CatalystStudies 116

4.2.1BriefOverviewoftheBasicsofMössbauerSpectroscopy 116

4.2.2MössbauerSpectroscopyfromthePointofViewofCatalyst Studies–ParticularFeatures 117

4.2.3TheProbabilityoftheMössbauerEffect–f-FactorandSizeEffects 118

4.2.4VariantsoftheTechnique 120

4.2.4.1 57 CoEmissionSpectroscopy 120

4.2.4.2Synchrotron-BasedNFS(NuclearForwardScattering) 122

4.2.4.3ConversionElectronMössbauerSpectroscopy 122

4.2.5TechnicalImplementations–ExperimentalConditions 123

4.3HeterogeneousCatalysts 124

4.3.1SitesonSupportedParticleswithDifferentParticipationinCatalytic Processes 124

4.3.2CollectiveEffectsinParticles(Magnetism) 125

4.3.3CaseStudies 126

4.3.3.1MetalsandAlloys 126

4.3.3.2OxideCatalysts 130

4.3.3.3CatalystswithFe–N,Fe–C,andFe–N–CCenters 133

4.4Biocatalysts–Enzymes 135

4.5HomogeneousCatalysts–FrozenSolutions 135

4.5.1StudiesonReactionIntermediates–Time-ResolvedFreeze-Quenched Spectra 136

4.6Conclusions 137 Acknowledgment 137 References 138

5ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopyinStudyingCatalysts forCOOxidationandPreferentialOxidationofCOinH2 145 KuoLiu,JunhuWang,andTaoZhang

5.1Introduction 145

5.2ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopyinCOOxidation 147

5.2.1 57 FeMössbauerSpectroscopy 147

5.2.2 119 SnMössbauerSpectroscopy 150

5.2.3 197 AuMössbauerSpectroscopy 151

5.2.4 193 IrMössbauerspectroscopy 152

5.3ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopyinPROX 153

5.3.1PtFe-ContainingCatalysts 153

5.3.2Au-BasedCatalysts 155

5.3.3IrFe-ContainingCatalysts 158

5.3.3.1PorousCarbonSupportedIrFeCatalysts 158

5.3.3.2SiO2 andAl2 O3 SupportedIrFeCatalysts 159

5.3.4CuO/CeO2 withFe2 O3 Additive 165

5.4ConcludingRemarks 165 Acknowledgments 166 References 166

6Applicationof 57 FeMössbauerSpectroscopyinStudying Fe–N–CCatalystsforOxygenReductionReactioninProton ExchangeMembraneFuelCells 171 XinlongXu,JunhuWang,SuliWang,andGongquanSun

6.1Introduction 171

6.2Advanced 57 FeMössbauerSpectroscopyTechnique 173

6.2.1RoomTemperature 57 FeMössbauerSpectroscopy 173

6.2.2LowTemperatureandComputational 57 FeMössbauer Spectroscopy 174

6.2.3InSituElectrochemical 57 FeMössbauerSpectroscopy 175

6.3CharacterizationofFe–N–CUsing 57 FeMössbauerSpectroscopy 177

6.3.1IdentificationofActiveSites 177

6.3.2InvestigationofDegradationMechanism 180

6.3.3OptimizationforSynthesisofFe–N–C 184

6.3.3.1PrecursorComposition 184

6.3.3.2HeatTreatment 185

6.4SummaryandPerspective 187 Acknowledgments 188 References 188

7 197 AuMössbauerSpectroscopyofThiolate-protectedGold Clusters 195 NorimichiKojima,YasuhiroKobaqyashi,andMakotoSeto

7.1Introduction 195

7.2SynthesisofThiolateProtectedGoldClusters 197

7.3 197 AuMössbauerSpectroscopyofGoldNano-clusters 198

7.3.1ExperimentalProcedureof 197 AuMössbauerSpectroscopy 198

7.3.2 197 AuMössbauerSpectraofAun (SG)m (n = 10∼55) 198

7.3.3MolecularStructureand 197 AuMössbauerSpectraofAu10 (SG)10 198

7.3.4MolecularStructureand 197 AuMössbauerSpectraofAu25 (SG)18 200

7.3.5StructuralEvolutionofAun (SG)m (n = 10∼55)Basedon 197 Au MössbauerSpectroscopy 201

7.3.6 197 AuMössbauerSpectraofAu24 Pd1 (SC12 H25 )18 204

7.3.7 197 AuMössbauerSpectraofAun (SC12 H25 )m 205

7.4Conclusion 208 Acknowledgments 208 References 209

8 197 AuMössbauerSpectroscopyofGoldMixed-Valence Complexes,Cs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII Y4 ](X,Y = Cl,Br,I)and [NH3 (CH2 )n NH3 ]2 [(AuI I2 )(AuIII I4 )(I3 )2 ](n = 7,8) 213 NorimichiKojima,YasuhiroKobaqyashi,andMakotoSeto

8.1Introduction 213

8.2ExperimentalProcedure 216

8.2.1SynthesisandCharacterization 216

8.2.1.1Cs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII Y4 ](X,Y = Cl,Br,I) 216

8.2.1.2[NH3 (CH2 )n NH3 ]2 [(AuI I2 )(AuIII I4 )(I3 )2 ](n = 7,8) 217

8.2.2 197 AuMössbauerSpectroscopy 217

8.3CrystalStructureofCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII Y4 ](X,Y = Cl,Br,I) 218

8.4ChemicalBondofAu Xin[AuI X2 ] and[AuIII X4 ] 221

8.5MössbauerParametersof 197 Auin[AuI X2 ] and[AuIII X4 ] 223

8.5.1MössbauerParametersof 197 Auin(C4 H9 )4 N[AuI X2 ]and (C4 H9 )4 N[AuIII X4 ] 224

8.5.1.1IsomerShift 224

8.5.1.2QuadrupoleSplitting 224

8.5.2MössbauerParametersof 197 AuinCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII X4 ] (X = Cl,Br,I) 225

8.5.2.1IsomerShift 225

8.5.2.2QuadrupoleSplitting 226

8.5.2.3Analysisof 197 AuMössbauerParametersforCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII X4 ] 226

8.6ChargeTransferInteractioninCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII X4 ](X = Cl,Br,I) 227

8.7 197 AuMössbauerSpectraofCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII Y4 ](X,Y = Cl,Br,I) 228

8.7.1IsomerShiftofAuI inCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII Y4 ] 228

8.7.2IsomerShiftofAuIII inCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII Y4 ] 230

8.7.3QuadrupoleSplittingofAuI inCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII Y4 ] 230

8.7.4QuadrupoleSplittingofAuIII inCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII Y4 ] 231

8.8SingleCrystal 197 AuMössbauerSpectraofCs2 [AuI I2 ][AuIII I4 ] 231

8.8.1Comparisonof 197 AuMössbauerSpectraBetweenSingleCrystaland PowderCrystal 231

8.8.2SignofEFGforAuI in[AuI I2 ] andAuIII in[AuIII X4 ] 234

8.9 197 AuMössbauerSpectraofCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII X4 ](X = Cl,I)UnderHigh Pressures 235

8.9.1PhaseDiagramofCs2 [AuI X2 ][AuIII X4 ](X = Cl,Br,I) 235

8.9.2OriginofMetallicMixed-ValenceStateinCs2 [AuI Cl2 ][AuIII Cl4 ] 236

8.9.3AuValenceTransitioninCs2 [AuI I2 ][AuIII I4 ] 239

8.10 197 AuMössbauerSpectraof[NH3 (CH2 )n NH3 ]2 [(AuI I2 )(AuIII I4 )(I3 )2 ] (n = 7,8) 241

8.11Conclusion 243 Acknowledgments 244 References 245

9Temperature-andPhoto-InducedSpin-Crossoverin Molecule-BasedMagnets 251 HirokoTokoro,KentaImoto,andShin-ichiOhkoshi

9.1Introduction 251

9.2Spin-CrossoverPhenomenainCesiumIronHexacyanidochromate PrussianBlueAnalog 252

9.3Light-InducedSpin-CrossoverMagnetinIronOctacyanidoniobate BimetalAssembly 254

x Contents

9.4ChiralPhotomagnetismandLight-ControllableSecondHarmonicLight inIronOctacyanidoniobateBimetalAssembly 258

9.5ConclusionandPerspective 265 References 265

10DevelopingaMethodologytoObtainNewPhotoswitchable Fe(II)SpinCrossoverComplexes 271 VarunKumarandYannGarcia

10.1IntroductionandContext 271

10.2IntroductiontoaNewPhoto-responsiveAnion: psca275

10.3CombiningFe(II)and psca TogetherinaSingleCompound 276

10.4Fe(II)MononuclearComplexeswithDMPPand psca Ligands 278

10.51DFe(II)CoordinationPolymerwith psca asNon-Coordinated Anions 281

10.6ConclusionsandPerspectives 284 References 285

11 57 FeMössbauerSpectroscopyasaPrimeTooltoExplore aNewFamilyofColorimetricSensors 291 LiSun,WeiyangLi,andYannGarcia

11.1IntroductionandGeneralContext 291

11.2ColorimetricGasSensorsBasedonFe(II)Complexes 292

11.3ConclusionsandPerspectives 306 References 306

Index 311

Preface

Afterthediscoveryofrecoil-freeresonanceabsorptioninthesolidstatebyR.L. Mössbauerin1958[1],aphysicalmethodcalledMössbauerspectroscopywas established.Thistechniquefindsnowadaysanumberofapplicationsinvarious researchfieldsincludingbiology,physics,materialscience,metallurgy,mineralogy, andchemistry.Itisthusnotsurprisingthatmanytextbooksandessayswithengagingtitlesareavailableintheliterature.Basically,thesecontainanintroduction tothetechnique,withprincipalhyperfineparametersalongwiththeirtheoretical description,followedbychaptersaboutvariousapplications,mostoftenfocusedon physics,whichareoflittlevalueforchemists,inparticularsyntheticchemists.

Thus,thisbook’ssolefocusonchemicalapplicationsconstitutesaunique reference.ItshowshowrelevantMössbauerspectroscopycanbetogivinguseful informationonelectronicpropertiesofmatter,structuralinsights,andsolid-state effectsofchemicalsystems.Readersinterestedinlearningaboutthetheoreticaland experimentalgroundsofthetechniqueareinvitedtorefertoexcellenttextbooks, e.g.byGütlichetal.[2].

Thebookoffersawiderangeofchemicalapplicationsandconceptsaswell asnumerousexamples.ItiswrittenbyleadingspecialistsinMössbauerspectroscopywhoareactiveinvariousfieldsofchemistryattheinternationallevel. Suchhigh-qualitybookisthusbeneficialtoreadersworkingindifferentareasof chemistryandmaterialsciencecoveredbyMössbauerspectroscopysuchasenergy, environment,lifesciences,molecularelectronics.Itisintendedforresearchers inacademia(universities,researchinstitutes)andindustry,aswellasoccasional readersandnewcomerstothefield.Itcouldbeusedforeducationalpurposesat themaster’sandPhDlevelstoo.Readersatthebachelorlevelareinvitedtoreferto thetextbookbyYoshidaandLangouche[3].ThisisanaspectgiventhatMössbauer spectroscopyisnowadaysseldomlytaughtinchemistryschools,withsomestudents evenignoringwhatitisaboutor,atworst,howusefulitcanbe.

Nowadays,thetopicofenergyisgainingimportanceduetothecurrentincrease inenergyprices.ThefundingkeychapterbyLippensintroducesustohowcan 119 Sn and 57 FeoperandoMössbauerspectroscopybeusefulforthestudyofelectrodematerialsforbatteries,aswellasspecificcatalysts.ThisisfollowedbyachapterbyLong andGrandjeanon 57 FeMössbauerspectralstudiesofironphosphate-containing minerals,someofwhicharepartofbatteriesusedintheindustry.

NextcomesachapterbyChen,Wang,andLiangon 57 FeMössbauerstudiesof iron-basedsilicides,whichcanbeusefulinoptoelectronicandthermoelectricapplications,aswellasforcatalyticconversion.

Whatwouldchemistrybewithoutcatalysis?Lázárgivesageneraloverviewofthe useofMössbauerspectroscopyappliedtocatalysts,consideringbothheterogeneous andhomogeneouscatalysts(viafrozensolutions).Itisfollowedbytwochapters:(i) byLiu,Wang,andZhangontheapplicationofthetechniqueinstudyingcatalysts forpreferentialoxidationofCOinthepresenceofH2 .(ii)byXu,Wang,Wang,and Sunontheapplicationof 57 FeMössbauerspectroscopyinstudyingFe–N–Ccatalysts foroxygenreductionreactionsinpolymerelectrolytemembranefuelcells.

ButMössbauerspectroscopyisnotrestrictedto 57 Feand 119 Snisotopes.Indeed, Kojima,Kobayashi,andSetointroduceustothefieldofthiolate-protectedgold nanoclustersinvestigatedby 197 AuMössbauerspectroscopy,followedbythe 197 Au Mössbauerspectroscopystudyofgoldmixedvalencecomplexes,Cs2 [AuI X2 ] [AuIII Y4 ](X,Y = Cl,Br,I)and[NH3 (CH2 )nNH3 ]2 [(AuI I2 )(AuIII I4 )(I3 )2 ](n = 7,8).

WhereaschemistryreadersareinvitedtorefertoseminalreviewsbyGütlichwith Mössbauerapplicationsincoordinationchemistryandspincrossoverphenomena [4,5],thecurrentbookdevelopsnovelapplicationsinthefieldofmolecular electronics.Tokoro,Imoto,andOhkoshiinviteustodiscovertemperature-and photo-inducedspincrossoveroccurringinsomemolecule-basedmagnets,studied by 57 FeMössbauerspectroscopy.KumarandGarciareportonanewwayto photo-inducethespinstateincoordinationcompounds,e.g.byirradiatingthe counter-anion(AD-LISCeffect),whereasSun,Li,andGarciacommentonthe possibilitytouse 57 FeMössbauerspectroscopyasaprimetooltoexploreanew familyofcolorimetricsensors,whichcouldfindapplicationinfoodpackaging freshnesscontrol.

ThebookprojectissupportedbytheMössbauerEffectDataCenter(MEDC), locatedinDalian(China).MEDCalreadydemonstrateditsinterestinthefieldby publishingfivespecialissueson“chemicalapplications”[6–10].Theprojectwas, ofcourse,delayedbytheCOVID-19crisis,affectingauthors,reviewers,aswell asthepublishinghouseatseveraldegreelevels.Nevertheless,theeditorswishto recognizetheinvolvementanddeterminationofeachintheprocessofproducing thisbook.

Attheendofthispreface,wewishtodedicatethisbooktothememoriesofProf. Dr.Ph.Gütlich(1934–2022)andtoDr.EckhardBill(1953–2022),whodidsomuch forchemicalapplicationsofMössbauerspectroscopy.

Wewishyouallreadersanenjoyablereading!

YannGarcia,JunhuWang,TaoZhang

References

1 Mössbauer,R.L.(1958). Z.Physik 151:124.

2 Gütlich,P.,Bill,E.,andTrautwein,A.X.(2011). MössbauerSpectroscopyand TransitionMetalChemistry:FundamentalsandApplications.Springer.

Preface xiii

3 Yoshida,Y.andLangouche,G.(2013). MössbauerSpectroscopy–TutorialBook. Springer.

4 Gütlich,P.andGarcia,Y.(2010). J.Phys.Conf.Ser. 217:012001.

5 Gütlich,P.andGarcia,Y.(2013,Chapter2). ChemicalApplicationsofMössbauer SpectroscopyinMössbauerSpectroscopy–TutorialBook (ed.Y.YoshidaandG. Langouche),23–89.Springer.

6 Garcia,Y.(2012).Chemicalapplications. Möss.Eff.DataRef.J. 35(6):111.

7 Garcia,Y.(2012).Chemicalapplications. Möss.Eff.DataRef.J. 35(8):191.

8 Garcia,Y.(2013).Chemicalapplications. Möss.Eff.DataRef.J. 36(4):47.

9 Garcia,Y.(2013).Chemicalapplications. Möss.Eff.DataRef.J. 36(6):103.

10 Garcia,Y.(2014).Chemicalapplications. Möss.Eff.DataRef.J. 37(3):49.

ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopytoEnergyMaterials

Pierre-EmmanuelLippens,Jean-ClaudeJumas,andJosetteOlivier-Fourcade InstitutCharlesGerhardtdeMontpellier,UMR5253CNRS,UniversitédeMontpellier,ENSCM, PôleChimieBalardRecherche1919routedeMende,MontpellierCedex5,France

1.1Introduction

Theincreasingdemandforenergyandtheenvironmentalproblemscausedbyfossil fuelsmakenecessarythefastdevelopmentofrenewableandcleanenergysources suchassolarorwind.However,theirintermittentnaturerequireshighlyefficient energystoragesystems.Furthermore,cleantransportation,suchaselectricorhybrid vehicles,needspowersourcesofhighenergydensity.Inthisregard,lithium-ion batteriescanbeconsideredasoneofthemostpromisingtechnologies.Although lithium-ionbatteriesareusedinelectronicdevices,powertools,electricbikes,and more,therearestillmanychallengestoovercomefornewapplicationsthatrequire higherenergyandpowerdensities,improvedsafety,andlowercost.Thisexplains thecurrentintensiveresearchonelectrodematerials[1,2].

Theperformanceofcurrentlyusedcarbonandlayeredlithiumtransitionmetal oxidesasnegativeandpositiveelectrodematerials,respectively,hasalmostreached theuppertheoreticallimits.Newnegativeelectrodematerialssuchassiliconand tinhavehightheoreticalcapacities,buttheysufferfromstrongvolumevariations duringcycling,whichleadstocapacityfadingandstronglyreducesthecyclelife [3,4].Amongthedifferentapproachesproposedtoimprovetheperformanceof suchmaterials,downsizingtheparticlesizeordispersingparticleswithinanelectrochemicallyinactivematrixhavebeenproposed[5,6].Forthepositiveelectrodes, newFe-containingmaterialssuchasLiFePO4 ,LiFe1 x Mnx PO4 ,orLiFePO4 Fappear tobeverypromisingforenvironmentalandeconomicaspects[7,8].Finally,the potentialproblemsofcobaltandlithiumsupplyinanearfuturehaverecentlyledto thedevelopmentofalternativetechnologiessuchasNa-ionbatteries[9,10].

Improvingtheperformanceofelectrodematerialsrequiresagoodknowledge oftheelectrochemicalreactionmechanismsinbatteries.Mössbauerspectroscopy isoftenusedforthecharacterizationofmaterials,butisalsoauniquetoolto followsuchreactionsattheatomicscalefromtheanalysisoftheMössbauer parameters:isomershift(giveninthischapterrelativeto α-FeandBaSnO3 for MössbauerSpectroscopy:ApplicationsinChemistryandMaterialsScience, FirstEdition.EditedbyYannGarcia,JunhuWang,andTaoZhang. ©2024WILEY-VCHGmbH.Published2024byWILEY-VCHGmbH.

1ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopytoEnergyMaterials

57 Feand 119 Snisotopes,respectively),quadrupolesplittingandhyperfinemagnetic field[11,12].Differentexamplesareconsideredtoillustratetheapplicationof MössbauerspectroscopytoelectrodematerialsforLi-ionandNa-ionbatteries. Thisincludestin-basednegativeelectrodematerials: β-Sn,tinoxides,tinborophosphates,tinintermetallics,andtin-siliconcomposites,aswellasiron-basedpositive electrodematerials:LiFePO4 ,LiFe1 x Mnx PO4 ,Fe1.19 PO4 (OH)0.57 (H2 O)0.43 ,and Na1.5 Fe0.5 Ti1.5 (PO4 )3

Reducingemissionandpollutionofexistingtransportationbasedonfossilfuelsis alsoagreatchallenge.Reformingcatalysisisamajorpetroleumrefiningprocessfor theproductionofhydrogenorhigh-octanegasoline.Inparticular,catalyticreformingisachemicalprocessusedtoconvertnaphtha,producedduringpetroleumrefining,intohigh-octanenumbergasoline.IfPt/Al2 O3 wasthefirstnaphtha-reforming catalyst,agreatprogresshasbeenachievedwithsupportedbimetallic-reformingcatalysts,inwhichPtispromotedbyanothermetalsuchasSn,thatofferhighselectivity atlowpressure[13].ImprovedselectivitycanbeobtainedbytheadditionofasecondpromoterasIn[14].Mössbauerspectroscopyhasbeenwidelyusedincatalysis [15,16].Someexamplesarepresentedheretoshowhowcomplexredoxprocesses inSn-Ptbasedcatalystsinvolvingmanydifferenttinspeciescanbeelucidated.

1.2MössbauerSpectroscopyforLi-ionandNa-ion Batteries

1.2.1CharacterizationofElectrodeMaterialsandElectrochemical Reactions

ThemainspecificationsofelectrodematerialsforLi-ionorNa-ionbatteriesare specificandvolumetriccapacities,nominalpotential,cyclelife,calendarlife, ratecapability,safety,environmentalimpact,andrecycling.Itisofcourseimpossibletooptimizeallthesefeaturesatthesametime.Forexample,layeredlithium transitionmetaloxides,ascommonlyusedpositiveelectrodematerialsforLi-ion batteries,havehighcapacityandhighpotentialvs.Li+ /Li.Lithiumironphosphate (LiFePO4 )haslowercapacitybutprovidesbettersafetyandhigherelectricpower. Thus,newelectrodematerialsareneededtoimprovetheperformanceofLi-ionand Na-ionbatteries.Thisrequiresabetterknowledgeoftheelectrochemicalreaction mechanismsthattakeplaceduringthecharge–dischargecycles.

Differenttechniqueshavebeenusedforthecharacterizationofelectrodematerials andtofollowthereactionswithinthebatteries.Thisincludesexsituexperiments, i.e.theelectrodematerialisextractedfromthebattery,insituexperiments,i.e.the electrodematerialisinthebattery,andoperandoexperimentsaselectrochemical reactionsproceed[17].X-raydiffraction(XRD)andMössbauerspectroscopyhave oftenbeencombinedtoobtaincomplementaryinformationaboutlongrangeand localproperties,respectively[18].Itisthuspossibletodeterminetheformedspecies eveniftheyareamorphous,tofollowchangesinlocalstructureoroxidationstatein ordertoelucidatethereactionmechanisms.

InsituandoperandoMössbauerandXRDmeasurementsrequirespecific electrochemicalcellsthatallowtransmissionof γ-raysandreflectionofX-rays,

1.2MössbauerSpectroscopyforLi-ionandNa-ionBatteries 3 respectively,whilevoltageorelectriccurrentisimposed.Suchacellisbasedon theusualpositiveelectrode/separator/electrolyte/negativeelectrodeconfiguration[19,20].Toinvestigatetheelectrochemicalreactionsforagivenelectrode material,ahalf-celliscommonlyused,wherethenegativeelectrodeismetallic lithium(orsodium)andthepositiveelectrodeistheformulatedelectrodematerial underinvestigation.Theformulationconsistsofmixingtheelectrochemicallyactive material(nanoparticlesormicroparticles)withanelectronicconductiveadditive, likecarbonblack,andabindertoformaslurrythatiscastedontothemetalcurrent collector[21].Inthecaseofanelectrochemicalhalf-cell,thedischargecorresponds tothelithiation(orsodiation)oftheelectrodematerialunderinvestigationandthe chargetodelithiation(ordesodiation).

1.2.2Tin-BasedNegativeElectrodeMaterialsforLi-ionBatteries

1.2.2.1ElectrochemicalReactionsofLithiumwithTin

Metallicandsemi-metallicelementscanbeusedasnegativeelectrodematerials forhighenergyLi-ionbatteries.Forexample,eachSnatomin β-Sncanreactwith amaximumof4.4Li,whichcorrespondstospecificandvolumetriccapacitiesof 992mAh g 1 and2111mAh cm 3 ,respectively[3].Thisismorethan2.6timesthe capacityofcurrentlyusedgraphite(372mAh g 1 and719mAh cm 3 ).Inaddition, theaveragepotentialof β-SninaLihalf-cellishigherthanthatofcarbon,which reduceslithiumplatingandimprovessafety.Unfortunately,theformationof Lix < 4.4 Snphasesduringlithiationinducesastrongincreaseoftheparticlevolume (>300%)thatcausescracks,whiledelithiationleadstothepulverizationofthe particles.Thesetwoeffectsareresponsibleformechanicalandelectricalinstabilities ofthenegativeelectrodefilm,whichdrasticallyreducesthecyclelifeofthebattery. XRDand 119 SnMössbauerspectroscopyhavebeencombinedtoobtaindeeper insightsintoLi–Snalloyingreactions.

Theexperimentalvoltagecurvesof β-SninaLihalf-cell,obtainedduringthefirst cycleingalvanostaticregimeatlowcurrentdensity,showdifferentwell-defined plateausthatcanbeattributedtotwo-phasereactions(Figure1.1)[22].

Thevoltageplateausareobservedforbothlithiationanddelithiationprocesses, showingthereversibilityofthemechanism.Thefollowingalloyingreactionshave beenproposedbyconsideringthedifferentcrystallinephasesofthecommonly acceptedLi–Snphasediagram[24]: 5 β-Sn + 2Li → Li2 Sn5 (1.1)

Sn5 + 3Li → 5LiSn(1.2) 3LiSn + 4Li → Li7 Sn3 (1.3) 2Li7 Sn3 + Li → 3Li5 Sn2 (1.4) 5Li5 Sn2 + Li → 2Li13 Sn5 (1.5)

2Li13 Sn5 + 9Li → 5Li7 Sn2 (1.6)

5Li7 Sn2 + 9Li → 2Li22 Sn5 (1.7)

First-principlescalculationsofthecellvoltagewereperformedwithdifferent methodsbasedondensityfunctionaltheory(DFT)forreactions(1.1)–(1.6)[22,23].

Figure1.1 Experimentalvoltageprofileforthefirstcycleof β-SninLihalf-cell[22]and voltageplateausevaluatedwithdensityfunctionaltheory(DFT)forthereactions(1.1)–(1.6) describedinthetext[23].Source:AdaptedfromRefs.[22,23].

Thecomparisonbetweentheexperimentalandtheoreticalvoltageprofilessuggests thatthetwofirstplateausataverageexperimentalvoltagesof0.75Vand0.65V reflecttheformationofLi2 Sn5 (reaction1.1)andLiSn(reaction1.2)crystalline phases,respectively.Thefollowingplateau,atabout0.5V,couldbeattributed totheformationofLi7 Sn3 (reaction1.3),Li5 Sn2 (reaction1.4),and/orLi13 Sn5 (reaction1.5)thathaveclosedchemicalcompositionsandformationenergies. TheexpectedplateaufortheformationofLi7 Sn2 (reaction1.6)isnotobserved experimentallysincethevoltagecurveshowsacontinuousdecreaseintherange 2.2–3.8LiperSn.Thiswasinterpretedbytheformationofametastablephasewith abody-centeredcubicdisorderedstructureshowingthesameshort-rangeorderas Li22 Sn5 [22].

OperandoXRDwasusedtofollowthestructuralchangesof β-Snsmallparticles inLihalf-cellduringthefirstcycleingalvanostaticregime(Figure1.2).

Duringthedischarge,thesuccessiveXRDpatternsshowthemainpeaksof β-Sn, Li2 Sn5 ,andLiSn,confirmingthatthetwofirstvoltageplateauscorrespondtothe reactions(1.1)and(1.2).Then,thereisonebroadbandaround2θ= 25∘ andapeak at2θ= 45∘ thatcanbeattributedtooneormoreLi-richLix Snphases,butitisnot possibletodeterminethechemicalcompositionfromtheXRDpatterns.Thelarge linewidthandthesmallintensityofthepeaksindicatethattheelectrochemically formedLix Snphasesarepoorlycrystallizedand/orofsmallsize.Thenanostructurationofthepristinematerialistypicalofalloyingreactionsandexplainstheinability ofXRDtogiveaccurateinformationaboutsuchelectrochemicalmechanisms,especiallyforthehighlylithiatedelectrodes.Themechanismisclearlyreversibleduring thecharge,butitisstilldifficulttodistinguishalltheintermediateLix Snphases. Insuchacase, 119 SnMössbauerspectroscopyisofparticularinterestsinceitissensitivetothelocalenvironmentoftheSnatomsandnottolong-rangeorder.

Figure1.2 OperandoXRDpatternsobtainedduringthefirstdischargeandthefirstcharge of β-SninLihalf-cell(galvanostaticregime)wherecolorsreflectX-rayintensity.

Tohavesomereferencecompoundsthatcanhelpintheinterpretationofthe 119 SnMössbauerexperimentsduringthecharge–dischargereactions,thespectra ofthesevenLix Sncrystallinephases,Li2 Sn5 ,LiSn,Li7 Sn3 ,Li5 Sn2 ,Li13 Sn5 ,Li7 Sn2 andLi22 Sn5 ,weremeasuredatroomtemperature[24].Thesephaseswereobtained intwodifferentways,namelyhightemperaturesolid-statereactions[25]and mechanosynthesisfollowedbyannealing[26].Thecrystalstructuresdeterminedby XRDshowtheexistenceofone(Li5 Sn2 ),two(Li2 Sn5 ,LiSn,Li7 Sn2 ),three(Li7 Sn3 , Li13 Sn5 ),andfour(Li22 Sn5 )crystallographicsitesforSn.TheMössbauerspectra obtainedforthetwoseriesofsynthesizedmaterialsgivesimilarMössbauerparameters.Theobservedsmalldifferencesareduetotheexistenceofimpuritiesand thedifficultiestofitunresolvedspectra.Onesetofspectraandthecorresponding parametersarereportedinFigure1.3andTable1.1,respectively.

Thevaluesofthequadrupolesplitting, Δ,canberelatedtothedifferentlocalenvironmentsofSnresultingfromtheexistenceofdifferenttypesofnearestneighbors (Li,Sn),polyhedralgeometries,andbondlengths[26].Theaveragevalueoftheisomershift, δav ,isofabout2.4mm⋅s 1 forthetwoSn-richphasesanddecreasesfrom 2.1to1.8mm⋅s 1 withincreasingnumberofLiperSnfortheLi-richphases.These valuesaretypicaloftheSn(0)oxidationstate.TheyreflecttheexistenceofaSnbased sublatticefortheSn-richphasesandthedecreaseinthenumberofSn—Snbonds perSnfortheLi-richphases.

Thevaluesof δav areplottedfortheLix Snreferencesasafunctionofx(Figure1.4). Thelinearcorrelationshowsthat δav (x)mainlydependsontheaveragechemical compositionofLix Snandcanbeusedtoevaluatexforamorphousphasesorsmall particlesasoftenencounteredinelectrochemicalreactions.Thelinearfunction

6 1ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopytoEnergyMaterials

–6–4–20

–6 –4 –20

(mm . s−1)

Figure1.3 119 SnMössbauerspectraofLix Sncrystallinephasesmeasuredatroom temperature.Source:ReproducedfromRef.[26]/withpermissionfromElsevier.

obtainedfortheregressionlineshowninFigure1.4canbewrittenas: δav (mm s 1 )= 2.55 0.20x(1.8)

OtherempiricalcorrelationruleshavebeenderivedfromtheLix SnMössbauer references,suchas δ–Δ correlationdiagramsusedtopredicttheelectrochemical activityofSnbasednegativeelectrodematerialsforLi-ionbatteries(Figure1.5)[27].

The 119 SnMössbauerspectroscopywasusedforexsitumeasurementsatdifferent stagesofthefirstdischargeof β-SninLihalf-cells[28].Theshapeofthevoltagecurve

1.2MössbauerSpectroscopyforLi-ionandNa-ionBatteries 7

Table1.1 Valuesofthe 119 SnMössbauerparametersofLix Sncrystallinephasesobtainedby Robertetal.[26].Thevaluesoftheisomershift, �� ,relativetoBaSnO3 andquadrupolesplitting, ��, arereportedforSnindifferentcrystallographicsites.

��/�� (mm⋅s 1 ) (crystallographic sites)

2.56/0.29 (4a) 2.49/042 (8i) 2.36/0.78 (2d) 2.38/0.43 (2m) 2.38/0.91 (1a) 2.19/0.82 (2e) 1.94/0.86 (2e,2e) 2.01/0.69 (6c) 1.86/0.48 (1a) 2.07/0.58 (2d,2d) 1.84/0.28 (4i) 1.96/1.13 (4h)

Source:AdaptedfromRef.[26].

1.83/0.31 (16e,16e, 24f,24g)

Figure1.4 AverageexperimentalvaluesoftheisomershiftoftheLix Sncrystalline referencesvs.numberofLiperSnandlinearregressionline(blue).

issimilartothatofFigure1.1,exceptattheverybeginningoflithiationduetothe existenceoftinoxidesasimpurities.Thespectrarecordedfortheinsertionof0.5,1, and3.4LiperSnwerefittedtotwodoubletsandthevaluesoftheMössbauerparametersaresimilartothoseofLi2 Sn5 ,LiSn,andLi7 Sn2 references,respectively,although therearesomesmalldifferencesthatcanbeattributedtothepoorcrystallinityand tovariationsinthechemicalcompositionoftheelectrochemicallylithiatedspecies.

Although β-Snhasahighercapacitythangraphite,itsuffersfromlargevolume variationsduringcyclingthataffectthemechanicalandelectricalintegrityofthe electrodefilm.Tinoxidecompositeswereproposedtoreducesucheffects[29],and theelectrochemicalmechanismsaredescribedinthefollowingtwoparagraphsby consideringtheapplicationofMössbauerspectroscopy.

1.2.2.2TinOxides

Stannicoxide(SnO2 )andstannousoxide(SnO)havetetragonal P42 /mnm and P4/nmm structures,respectively.TheMössbauerspectrumofSnO2 isformedby

Figure1.5 CorrelationdiagramforSn-basedmaterialsbasedonexperimentalvaluesof isomershift, δ,andquadrupolesplitting, Δ asinglepeakreflectingtheSn(IV)oxidationstate(δ= 0mm s 1 )andaslightly distortedSnO6 octahedralenvironment(Δ= 0.5mm s 1 ).SnOcanbedescribedas parallelSn–O–Snlayers,andeachSnatomisbondedtofourOatomstoformaSnO4 squarebasedpyramid.TheMössbauerspectrumconsistsofanasymmetricdoublet characteristicoftheSn(II)oxidationstate(δ= 2.63mm s 1 ),whilethequadrupole splitting(Δ= 1.33mm s 1 )reflectstheanisotropyoftheSnp-typeelectrondensity arisingfromtheSn5plonepairalongthefourfoldpyramidaxis.

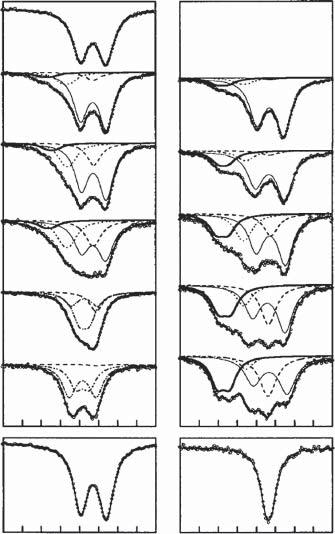

ThevoltageprofilesofSnO2 andSnObasedelectrodesobtainedingalvanostatic regimeshowsimilartrends[30–33].ThefirstdischargeofSnOisformedbya plateauat ∼1Vfor2LiperSn(RegionR1),followedbyacontinuousvoltage decreaseshowingdifferentpseudo-plateaus(RegionR2)(Figure1.6).Then, thevoltageprofilesofthetwotinoxidesaresimilartothatof β-Snforthesubsequentcharge–dischargecycles.Theelectrochemicalmechanismwasstudiedby exsitu[31]andoperando[32] 119 SnMössbauerspectroscopy.Aslithiationproceeds inR1,thereisaprogressivebroadeningofthespectraatthelowvelocityside, endingwithalargeandunresolvedpeakattheendofthefirstplateau(A–Din Figure1.7).Theexperimentalspectraweresuccessfullyfittedtothreecomponents correspondingtoSnO, β-Sn,andaSn(IV)oxide,respectively,andanadditionalcomponentcenteredatabout1.2mm⋅s 1 .ThecontributionofSnOdecreasesduringthe lithiationwhilethatof β-Snincreases,whichcorrespondstotheconversionreaction: SnO + 2Li → β-Sn + Li2 O(1.9)

Thesubspectrumat1.2mm⋅s 1 canbeenattributedtoSnbondedtobothSnand Oatomsresultingfrominteractionsbetween β-SnandLi2 Osmallparticlesortothe existenceofLi–Sn–Oamorphousphases.InregionR2,theexsituspectraEandF

1.2MössbauerSpectroscopyforLi-ionandNa-ionBatteries 9

Figure1.6 VoltagecurvesofSnOinLihalf-cellwiththepointsofmeasurementsforthe firstdischarge(A–F)andfullchargesat3V(B1–F1).Source:ReproducedfromRef.[31]/with permissionfromElsevier.

Figure1.7 Exsitu 119 SnMössbauer spectraatdifferentstagesofthefirst dischargeandoftheendofcharges. Source:ReproducedfromRef.[31]/with permissionfromElsevier.

1ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopytoEnergyMaterials (Figure1.7)aresimilartopublishedinsituMössbauerspectra[32].However,more spectrawererecordedinthelattercaseduetoadeeperlithiation.Theyareclose tothespectraofthereferencematerials,confirmingtheformationofSn-richand Li-richLix Snequilibriumphases,exceptaroundLi5 Sn2 asdiscussedabovefor β-Sn. TheLix Sndealloyingreactionsoperateduringthecharge,butabackreactionofSn withO,arisingfromthedelithiationofLi2 O,isobservedathighvoltage.Thelater reactionisoutoftheusualvoltagerangefornegativeelectrodesinLi-ionbatteriesandshouldnotbeconsidered.Inthatcase,theelectrochemicalmechanismof SnOconsistsoftheirreversibleconversionreactionofSn(II)Ointo β-Sn(0)followed byreversibleLix Snalloyingreactions.TheLi2 Oparticlesformanelectrochemically inactivematrixthatmaintainsthedispersionoftheLix Snparticlesandbuffersthe volumevariations,improvingthecyclingbehaviorcomparedto β-Sn.However,the insituformationoftheLi2 Omatrixleadstoacapacitylossatthefirstcyclethat requiresacompensationbythelithiatedpositiveelectrodeinaLi-ionfull-cell.The situationisevenmorecriticalforSnO2 sincefourLiperSnarerequiredforitstransformationinto β-Sn/Li2 Onanocomposite.

1.2.2.3TinBorophosphates

Tincompositeoxides(TCO)wereproposedbyFujiinthelate1990sasnegativeelectrodematerialsforLi-ionbatteries[29].AmongthedifferentTCOs,thetinborophosphateglassSnO(B2 O3 )0.25 (P2 O5 )0.25 (Sn2 BPO6 inthetext)wasstudiedbyinsitu 119 Sn Mössbauerspectroscopy[32].ThevoltageprofileofthefirstcycleofSn2 BPO6 in aLihalf-cellissimilartothatofSnO,exceptthatthevoltageofthefirstplateau (1.75V)ishigher(Figure1.8).TheMössbauerspectrumofSn(II)2 BPO6 ,similarto thatofSnO,istransformedintoabroadbandofweakintensityattheendofthefirst plateau.ThisreflectsthetransformationoftheSn(II)basedpristinematerialinto β-Snsmallclustersembeddedinamixedborophosphateandlithiumoxidematrix (Figure1.8).Then,theMössbauerspectraaresimilartotheLix Snreferencesexcept aroundLi5 Sn2 .Thespectraobtainedalongthefirstchargeuntil1Vwereattributed totheLix Snphasesresultingfromdealloyingreactions,whichisconsistentwitha reversibleprocess.Asthechargeproceedsuntil2.5V,thereisapartialreformation ofSn2 BPO6 .

Thus,theelectrochemicalmechanismofSn2 BPO6 glassconsistsintheformation ofSn(0)tinyparticlesembeddedinamorecomplexmatrixthanthatobtainedfor SnO,followedbyalloying–dealloyingLix Snreactions.Thevalueofthevoltagecutoff forcharge(≈0.8V)iscrucialtoavoidbackreactionofSnwithO.Theelectrochemical performanceofTCO,suchascyclability,showsthataborophosphatematrixismore efficientthanaLi2 Omatrix,asobtainedfortinoxidecompounds,tomaintainthe dispersionoftheLix Snparticlesandbufferthevolumevariationsduringcycling. TinborophosphatecompositeswerealsoconsideredaspossiblenegativeelectrodematerialsforLi-ionbatteries,suchasSn/(BPO4 )0.2 thatshowsareversible capacityofabout500mAh⋅g 1 [33,34].TheoperandoMössbauermeasurements wereperformedingalvanostaticregimeatC/10inthevoltagerange0.1–1.2V[35]. TheMössbauerspectrumofthepristinematerialshowstheexistenceof β-Sn butalsoofanamorphousSn(II)-borophosphatephasenotobservedbyXRD

Figure1.8 Insitu 119 Sn Mössbauerspectraatdifferent stagesofthefirstdischargeof Sn2 BPO6 .Source:Reproduced fromRef.[32]/withpermission fromElsevier.

1.2MössbauerSpectroscopyforLi-ionandNa-ionBatteries 11

(Figure1.9).Atthebeginningofdischarge,thevoltagecurveshowsaplateau at1.5V,significantlyshorterthantheplateausoftinoxidesorTCOdiscussedabove, followedbyavoltagedecreaseuntil0.4Vforabout0.6LiperSn(Figure1.10a). TheintensityoftheSn(II)Mössbauerabsorptionstronglydecreasesintherange 0–0.2LiperSn,whichindicatesthattheplateaucorrespondstothereduction oftheSn(II)amorphousphaseintoSn(0)(Figure1.10b).Then,thereisnomore changeinthespectrauntil0.9V,inlinewiththeirreversiblereactionoflithium withtheelectrolyte,leadingtotheformationofasolidelectrolyteinterphase(SEI) attheparticlesurface.Asdischargeproceedsfurther,thevoltagecurveshows aplateauat0.4Vandthendecreasesuntil0.1Vintherangefrom0.6to3.2Li perSn.TheaverageMössbauerisomershiftdecreasesfrom2.45to2.0mm⋅s 1

Byconsideringthe δav (x)linearfunctionforLix Sn(seeEq.1.8),thelattervalue suggeststhatx ≈ 2.5(Figure1.10cand1.10d),inagreementwiththe2.6Lireacting with β-Sninthisregion.Thislowvalueofx,comparedtotheexpectedLi22 Sn5 phase,isduetothevoltagecutoffof0.1Vusedinthisexperiment,whichprevents deeplithiation.Duringthefirstcharge,theaverageisomershiftlinearlyincreases, asexpectedfromthedelithiationofLix Sn,endingwith δav ≈ 2.35mm⋅s 1 ,which correspondstox ≈ 1.Thisconfirmsthereversibilityofthealloyingprocessalthough

1ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopytoEnergyMaterials

Figure1.9 119 SnMössbauerspectrumofSn/(BPO4 )0.2 composite(relativetransmission:rel. trans.)showingtherelativeamountsofSnII andSn0 species.Source:AdaptedfromRef.[35].

Figure1.10

VoltageprofileofSn/(BPO4 )0.2 inLihalf-cellforthegalvanostaticregimeof C/10(a),amountsofSn(II)andSn(0)atthebeginningoffirstdischarge(b),evolutionofthe Sn(0)averageisomershift, δ,asafunctionoftimereaction(c),andasafunctionofthe numberofLiperSn(d):firstdischargeinred,firstchargeinblue,andseconddischargein green.

1.2MössbauerSpectroscopyforLi-ionandNa-ionBatteries 13 thereisnofulldelithiation.Thevoltageprofileobservedfortheseconddischarge issimilartothefirstonebutisintherange1.3–3.2LiperSn.Theaverageisomer shiftfollowsthesametrendasduringthefirstdischarge,correspondingtothe progressivechangeintheaveragecompositionofLix Snfromx = 1toabout2.5.

TheresultsreportedherefortinoxidesasnegativeelectrodematerialsforLi-ion batteriesshowthatthefirstdischargeconsistsintherestructurationoftheelectrode material,endingwithLi-richLix Snnanoparticlesdispersedinanelectrochemically inactivematrixcomposedofoxide,borate,orphosphatebasedparticles.Thismatrix helpstobufferthestrongvolumevariationsofLix Snduringalloying–dealloying reactions,reducingthecapacityfadingandimprovingthecyclelife.However,there arestillsomeissuesregardingthecapacitylossatfirstcycleduetotheirreversible consumptionofLiandthelargevoltagepolarizationduetothepoorelectronicconductivityoftheoxidebasedmatrix.Significantimprovementshavebeenobtained withtinintermetallicsasdescribedinthefollowingsection.

1.2.2.4Tin-BasedIntermetallics

AdvantagesoverTinOxides Theuseoftinintermetallicsasnegativeelectrode materialsforLi-ionbatteriesisbasedonthesameconceptastinoxides,which istoformananocompositeduringthefirstdischarge,exceptthatthematrixis composedofmetallicparticlesinordertoimprovetheelectronicconductivity.In addition,themicrostructureofmetalbasedmatricesisdifferentfromthatofoxide matrices,whichcouldbeadvantageousforbufferingthevolumechangesresulting fromLix Snalloyingreactions.Butthemostinterestingaspectoftinintermetallics istheexistenceofSn(0)oxidationstate.Thereisnoreductionoftinpriorto alloyinglithiationduringthefirstdischarge,asSn(IV)orSn(II)intinoxides,which reducesthecapacitylossofthefirstcycle.Mostofthetin-basedintermetallics, MSnx ,combineSnwithatransitionmetal,M,thatdoesnotreactwithLi.The firstdischargeisexpectedtoextrudetheMatomsfromMSnx toformmetallic nanoparticles(thematrix)thatmaintainthedispersionofLix Snnanoparticles. AlthoughcarbonadditivesandabinderareaddedtoMSnx particlestoformthe conductivefilmcastedonthemetalcurrentcollector,carboncanalsobeintroduced duringthesynthesisprocesstoformaMSnx /Ccomposite.Suchcompositeshave beenwidelystudiedinrelationwiththecommercializationbySonyoftheNexelion Li-ionbatteries[36–40].Thespecificcapacitywasabouttwiceashighthanthat ofgraphite.AdetailedstudyofFeSn2 ispresentedinthefollowingpart.This compoundisofparticularinteresttofollowlithiation–delithiationreactionssince itcontainsboth 57 Feand 119 SnMössbauerisotopes.

ElectrochemicalReactionsofLithiumwithFeSn2

FeSn2 hasatetragonalstructure (I 4/mcm),andtheunitcellcontainsonecrystallographicsiteforFeatthecenterof aSnbasedsquareantiprism.ThereisalsoonecrystallographicsiteforSnbonded tofourFeatomstoformaSnFe4 squarebasedpyramid.FeSn2 microparticles weresynthesizedbysolid-statereactionaselectrodematerialforLi-ionbatteries andnanostructuredbyanadditionalball-millingstep[41].TheFeSn2 crystalis antiferromagneticbelow378K[42],andthe 57 FeMössbauerspectrumisformed

1ApplicationofMössbauerSpectroscopytoEnergyMaterials

Figure1.11 VoltageprofilesofFeSn2 basedelectrodesatC/50.Source:Reproducedfrom Ref.[41]/withpermissionfromElsevier.

byasextetatroomtemperature.The 119 SnMössbauerspectrumshowsbroad structuresintherange0–5mm⋅s 1 ,reflectingatransferredhyperfinemagnetic field[43].TheMössbauerparameters: δ= 0.5mm⋅s 1 , Δ= 0mm⋅s 1 ,B = 11Tfor Feand δ= 2.18mm⋅s 1 , Δ= 0.83mm⋅s 1 ,B = 2.4TforSnaretypicalofFe(0)and Sn(0)oxidationstateswithaSnasymmetricalenvironment.Similarvaluesofthe MössbauerparameterswereobtainedfornanostructuredFeSn2 exceptthereisno hyperfinemagneticfieldbecauseofthesmallsizeandthepoorcrystallinityofthe FeSn2 groundparticles[41].

ThevoltageprofileoftheelectrodecontainingFeSn2 microparticlesshowsa lowvoltageplateauforthefirstdischargeandavoltagehysteresisattheaverage valueof0.5Vforthefollowingcycles(Figure1.11).Thevoltagecurveofthefirst dischargediffersfromthatoftinoxidesandreflectsatwo-phasereaction.Thisis confirmedbyoperandoXRDthatshowsthedirecttransformationofFeSn2 intoa Li-richLix Snphaseaslithiationproceeds.However,thechemicalcompositionand thestructureoftheformedLix Snphasecannotbedeterminedduetounresolved Braggpeaks.Theoperando 119 SnMössbauerspectrashowstrongchangesfrom themagneticspectrumofFeSn2 toanasymmetricalpeakattheendofdischarge (Figure1.12a).TheMössbauerparametersofthefullylithiatedelectrodeareclose tothoseoftheLi7 Sn2 crystallinereferenceexceptforonevalueofthequadrupole splitting(Δ= 0.72mm⋅s 1 )smallerthanthereference(Δ= 1.13mm⋅s 1 ).Thiswas attributedtothesmallsizeand/orpoorcrystallinityoftheLi7 Sn2 particles[44]. The 57 FeMössbauerspectrachangefromasextetforFeSn2 toadoubletwith Mössbauerparameters(δ= 0.2mm s 1 , Δ= 0.5mm s 1 )thatcanbeattributedto α-Fenanoparticlesinparamagneticstate(Figure1.12b).

Alltheintermediate 57 Feand 119 SnMössbauerspectraweresuccessfullyfittedto thespectraofFeSn2 /α-Fe(nano)andFeSn2 /Li7 Sn2 (nano)phases,respectively,showingthatthefirstdischargecanbedescribedbythetwo-phasereaction: