Interface Engineering in Organic Field-Effect Transistors Xuefeng Guo

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/interface-engineering-in-organic-field-effect-transistor s-xuefeng-guo/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Effect of electrode Pt-loading and cathode flow-field plate type on the degradation of PEMFC Qu

https://ebookmass.com/product/effect-of-electrode-pt-loading-andcathode-flow-field-plate-type-on-the-degradation-of-pemfc-qu/

Brain-Computer Interface M.G. Sumithra

https://ebookmass.com/product/brain-computer-interface-m-gsumithra/

GaN transistors for efficient power conversion Third Edition De Rooij

https://ebookmass.com/product/gan-transistors-for-efficientpower-conversion-third-edition-de-rooij/

Scattering Methods and their Application in Colloid and Interface Science Otto Glatter

https://ebookmass.com/product/scattering-methods-and-theirapplication-in-colloid-and-interface-science-otto-glatter/

The Zelensky Effect Olga Onuch

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-zelensky-effect-olga-onuch-2/

The Zelensky Effect Olga Onuch

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-zelensky-effect-olga-onuch/

New Media and the Artaud Effect Jay Murphy

https://ebookmass.com/product/new-media-and-the-artaud-effectjay-murphy/

Conditions in Occupational Therapy: Effect on Occupational Performance 5th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/conditions-in-occupational-therapyeffect-on-occupational-performance-5th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Fluid Inclusion Effect in Flotation of Sulfide Minerals 1st Edition Shuming Wen

https://ebookmass.com/product/fluid-inclusion-effect-inflotation-of-sulfide-minerals-1st-edition-shuming-wen/

InterfaceEngineeringinOrganicField-EffectTransistors

InterfaceEngineeringinOrganicField-Effect Transistors

XuefengGuo

HongliangChen

Authors

Prof.XuefengGuo PekingUniversity 202ChengfuRd HaidianDistrict 100871Beijing China

Prof.HongliangChen ZhejiangUniversity No.866YuHangTangRd XihuDistrict 310027Hangzhou China

CoverImage: ©blackdovfx/GettyImages

Allbookspublishedby WILEY-VCH arecarefully produced.Nevertheless,authors,editors,and publisherdonotwarranttheinformation containedinthesebooks,includingthisbook, tobefreeoferrors.Readersareadvisedtokeep inmindthatstatements,data,illustrations, proceduraldetailsorotheritemsmay inadvertentlybeinaccurate.

LibraryofCongressCardNo.: appliedfor BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData Acataloguerecordforthisbookisavailable fromtheBritishLibrary.

Bibliographicinformationpublishedby theDeutscheNationalbibliothek TheDeutscheNationalbibliotheklists thispublicationintheDeutsche Nationalbibliografie;detailedbibliographic dataareavailableontheInternetat <http://dnb.d-nb.de>

©2023WILEY-VCHGmbH,Boschstraße12, 69469Weinheim,Germany

Allrightsreserved(includingthoseof translationintootherlanguages).Nopartof thisbookmaybereproducedinanyform–by photoprinting,microfilm,oranyother means–nortransmittedortranslatedintoa machinelanguagewithoutwrittenpermission fromthepublishers.Registerednames, trademarks,etc.usedinthisbook,evenwhen notspecificallymarkedassuch,arenottobe consideredunprotectedbylaw.

PrintISBN: 978-3-527-35145-9

ePDFISBN: 978-3-527-84046-5

ePubISBN: 978-3-527-84047-2

oBookISBN: 978-3-527-84048-9

Typesetting Straive,Chennai,India

Contents

Preface ix

AuthorBiographies xi

ListofAcronymsandAbbreviations xiii

1Introduction 1

1.1DifferentInterfacesinOFETs 1

1.2BriefHistoricOverviewofInterfaceEngineeringinOFETs 3

1.3ScopeoftheBook 3

2InterfacialModificationMethods 7

2.1NoncovalentModificationMethods 7

2.1.1ChargeInsertionLayerattheElectrodeSurface 7

2.1.2DielectricSurfacePassivationMethods 9

2.2CovalentModificationMethods 12

2.2.1SAMModificationofElectrodes 12

2.2.2SAMModificationofDielectrics 12

2.2.2.1SAM/SiO2 Dielectrics 14

2.2.2.2SAM/High-k Dielectrics 14

2.2.2.3Self-AssembledMonolayerField-EffectTransistors(SAMFETs) 28

2.3EffortsinDevelopingNewMethods 31

3Semiconductor/SemiconductorInterface 33

3.1InfluenceofAdditivesonaMaterial’sNucleationandMorphology 37

3.1.1SolventAdditives 37

3.1.2NucleatingAgents 41

3.1.3Template-MediatedCrystallization 43

3.1.4BlendingwithInsulatingPolymers 45

3.1.5BlendingwithPolymerElastomer:NanoconfinementEffect 50

3.2EnhancingthePerformanceThroughSemiconductor Heterojunctions 55

3.2.1PlanarBilayerHeterostructures 57

3.2.2Molecular-LevelHeterojunction 61

3.2.3SupramolecularArrangementoftheHeterojunctions 64

3.3IntegratingMolecularFunctionalitiesintoElectricalCircuits 69

3.3.1Charge-Trapping-InducedMemoryEffect 69

3.3.2Photochromism-InducedSwitchingEffect 72

4Semiconductor/ElectrodeInterface 77

4.1WorkFunctionTuningforBetterContact 79

4.1.1SAMModification 80

4.1.2ChargeInsertionLayerModification 84

4.1.3Polymer-BasedElectrodes 89

4.1.4CarbonNanomaterial-BasedElectrodes 92

4.1.5CovalentBondFormationattheMolecularLevel 97

4.2InstallingSwitchingEffectsatSemiconductor/ElectrodeInterface 100

5Semiconductor/DielectricInterface 103

5.1DielectricModificationtoTuneSemiconductorMorphology 105

5.1.1DielectricSurfaceEnergyControl 106

5.1.1.1ModifywithSAM 106

5.1.1.2SurfaceModificationwithPolymers 112

5.1.2DielectricMicrostructureDesign 113

5.1.2.1RoughnessEffect 114

5.1.2.2Nano-fabricationCreatedMicrostructure 116

5.1.2.3Self-assembledMorphologyofDielectric 118

5.2EliminatingInterfacialTraps 120

5.2.1DielectricSurfacePassivation(Treatment)Methods 121

5.2.1.1PolymerEncapsulationofDielectrics 122

5.2.1.2GapDielectrics 124

5.2.2SAM/SiO2 Dielectrics 126

5.2.2.1ProvideEfficientInsulatingBarrierHeight 127

5.2.2.2ControlSurfacePolarityandCarrierDensity 128

5.2.3SAM/High-k Dielectrics 131

5.2.3.1FundamentalsofSAM-ModifiedHigh-k Dielectrics 132

5.2.3.2SAM/High-k HybridDielectricsforFlexibleSubstrate 134

5.2.4Self-assembledMonolayerField-EffectTransistors(SAMFETs) 137

5.2.4.1MoleculeDesignforSAMFETs 137

5.2.4.2MorphologyControlofSAMFET 139

5.3IntegratingNewFunctionalities 141

5.3.1PhotoresponsiveDielectrics 142

5.3.2OtherExternalStimuli-ResponsiveDielectrics 144

5.3.2.1PressureSensor 145

5.3.2.2ThermalSensor 147

5.3.2.3MagneticSensor 147

5.3.2.4MultifunctionalSensor 148

5.3.3IntegratingMemoryEffectattheDielectrics 148

6Semiconductor/EnvironmentInterface 155

6.1DeviceOptimizationtoImproveSensingPerformance 156

6.1.1MonolayerFunctionalization 156

6.1.2BilayerHeterojunctionApproach 158

6.1.3RemoteFloatingGate 159

6.2OECT-BasedandEGOFET-BasedSensors 160

7InterfacingOrganicElectronicswithBiology 165

7.1IntegrationofOFETs/OECTswithNonelectrogenicCells 166

7.2IntegrationofFlexibleBioelectronicswithElectrogenicCells 170

7.3Light/Cell/DeviceInterfaces 174

8ConcludingRemarksandOutlook 179

8.1NewChallengesinMolecularDesign 179

8.2High-QualityOSCFilms:Self-AssemblyControl 180

8.3High-PerformanceScalableFlexibleOptoelectronics 180

8.4ExplorationofNovelStructures:Organic/2DHeterostructuresand VerticalStructures 181

8.5Instability:StabilityinAqueousMediaandThermalStabilityinHygienic Applications 181

8.6MultifunctionalSensorSystems 183

References 185 Index 251

Preface

Thedevelopmentofmicroelectronicsintomodernintegratedcircuitsoverthe past75yearswastheresultofcontinuouseffortsofhugeteamsofscientistsand engineers.Thedeviceperformanceofmicroelectronicdevicesismainlydetermined bythepropertiesofthematerialsusedandtheircorrespondinginterfaces,justas NobellaureateHerbertKroemercoined,“theinterfaceisthedevice.”Understandingandgoverningthechargetransferphenomenaoccurringattheinterfacescould revolutionizeanumberofrelatedfields,includingbatteries,catalysis,datastorage, energyharvesting,imagingdisplays,sensingdevices,andevensolarcells.Forthese reasons,interfaceengineeringoftheseheterojunctionshascapturedtheattention ofabroadcrosssectionofscientificandindustrialcommunities.

Incomparisonwithtraditionalcomplementarymetaloxidesemiconductor transistors,theadvantagesoforganicfield-effecttransistors(OFETs)originatefrom howOFETscanbemanufactured,includingtheconsiderablevarietyinmolecular design,lowcost,lightweight,mechanicalflexibility,solutionprocessability,and large-areafabrication.Thekeyconceptofthisbookistouseinterfaceengineering strategiestoimprovetheinherentpropertiesofOFETsaswellastobuildnovel functionaldevicesbasedonOFETs.Bothareofgreatimportanceforlayingthe foundationfortheOFETresearch.Forthefirstpoint,rapidprogresshasbeenmade oneachisolatedcomponentofOFETstoimprovetheperformance,withmajor emphasisonorganicsemiconductingmaterialdesignandrelevantfilmprocessing methods.Althoughtheimprovedelectronicpropertiesofthesematerialscould offerdeviceperformanceadvantages,interfacialbarriersbetweenthesemiconductors,dielectriclayers,andelectrodesareoftentreatedassecondaryconcerns incomparisonwiththegenerationandpreservationofcarrierpopulationinthe semiconductoritself.Inpursuitofhighperformance,OFETswillinevitablyrequire anoptimizedcarriertransportpathwaythatleveragesallthedevicelayersandtheir correspondinginterfaces.Thisshouldbeasimportantasthematerialdesignand relevantfilmprocessingmethods.

Thesecondpointisthathowto“use”OFETsisanotherimportantissuein OFETresearch.Ofcourse,hugeprogresshasbeenmadetodevelopavarietyof functionaldevicesbasedonOFETs,suchaschemo/biosensors,photodetectors, integratedcircuits,andflexibleelectronics.Theycanberealizedbyusingvarious strategies,forexample,designingfunctionalsemiconductingmaterials,developing

x Preface semiconductorprocessingmethods,andtailoringfunctionalinterlayers.Inthis book,however,wewillspecificallysurveythemostrecentandimportantworks employinginterfaceengineeringstrategiestodevelopfunctionalOFETdevices. Webelievethatinterfacialmodificationisamuchsimpler,moreefficientwayto integratefunctionalities.

ThisbookwillfocusoninterfaceengineeringofOFETsandaimtoprovidefundamentalunderstandingsoftheinterplaybetweenthemolecularstructure,assembly, andemergentfunctionsatthemolecularlevelandconsequentlyoffernovelinsights intodesigninganewgenerationofmultifunctionalintegratedcircuitsandsensors towardpracticalapplications.Actually,theinterfaceengineeringstrategycanbe leveragedtoimprovetheefficiencyandstabilityofperovskitesolarcells.Webelieve thatthisbookwilldrawwidespreadinterestfromresearchersworkingonorganic electronics,chemo-andbiosensors,solarcells,flexibleelectronics,andother device-relatedfields.

WewouldliketothankWileyforofferingtheopportunitytopreparethis book,especiallyMs.AliceQian.Wewouldalsoliketoexpressourdeepgratitude toMs.KatrinaMacedaandMs.MonicaChandraSekarwhohavecontributed theirtimeandoutstandingexpertisetomakethisbookpossible.Also,thanksto Dr.WeiningZhangforthehelpfuldiscussionsduringthepreparationofthebook. Finally,wehopethatthereadersofthisbookwillfinditbothusefulanddelightful.

Beijing,China XuefengGuoandHongliangChen December2022

AuthorBiographies

XuefengGuo receivedhisPhDin2004fromtheInstituteofChemistry,Chinese AcademyofSciences,Beijing.From2004to2007,hewasapostdoctoralresearch scientistattheColumbiaUniversityNanocenter.Hejoinedthefacultyasaprofessor underthe“Peking100-Talent”ProgramatPekingUniversityin2008.In2012,he wontheNationalScienceFundsforDistinguishedYoungScholarsofChina.His currentresearchisfocusedonfunctionalnanometer/moleculardevices.Professor XuefengGuohasauthoredover210scientificpublicationsandhasreceived numerousscientificawards,includingtheFirstprizeofMinistryofEducation NaturalScienceAward.

HongliangChen receivedhisPhDin2016fromtheCollegeofChemistry andMolecularEngineering,PekingUniversity,undertheguidanceofProfessor XuefengGuo.From2016to2018,heworkedasaresearchscientistattheCore R&DdepartmentinDowChemicalCompany.ThenhemovedtoNorthwestern UniversityinUnitedStatesandworkedasapostdoctoralresearchfellowinProfessor SirFraserStoddart’sgroupfrom2018to2021.HejoinedZhejiangUniversityas anassistantprofessorunder“ZJU100-Talent”PrograminJune2021.Hisresearch interestsarefocusedonorganicfunctionaldevicesandmolecularelectronics.

ListofAcronymsandAbbreviations

1Done-dimensional

2Dtwo-dimensional

3Dthree-dimensional

AFMatomicforcemicroscopy

AZOsazobenzenes

BCBdivinyltetramethyldisiloxane-bis(benzocyclobutene)

BTBT[1]benzothieno[3,2-b][1]-benzothiophene

C8 -BTBT2,7-dioctyl[1]-benzothieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophene

CILchargeinsertionlayer

CNTscarbonnanotubes

CTcharge-transfer

D–Adonor–acceptor

DAEdiarylethene

DNTTdinaphtho[2,3-b:2′ ,3′ -f ]thieno[3,2-b]thiophene

DOSdensitiesofstate

EA energygapofOSC

EF Fermilevelofelectrodes

EVAC vacuumenergylevel

FLGfew-layergraphene

GOsgrapheneoxides

Grgraphene

HMDShexamethyldisilazane

HOMOhighestoccupiedmolecularorbital

k relativepermittivityordielectricconstant

LBLangmuir–Blodgett

LUMOlowestunoccupiedmolecularorbitals

MWCNTsmultiwalledcarbonnanotubes

NDInaphthalenediimide

NHCsN-heterocycliccarbenes

OFETorganicfield-effecttransistor

OLETorganiclight-emittingtransistor

OSCsorganicsemiconductors

P3HTpoly(3-hexylthiophene)

xiv ListofAcronymsandAbbreviations

PAPhosphonicacid

PCBM[6,6]-phenyl-C61 -butyricacidmethylester

PCMsphotochromicmolecules

PDIperylenediimide

PDMSpolydimethylsiloxane

PENpolyethylenenaphthalate

PHBDphotohybridbilayerdielectric

PLApolylactide

PMMApoly(methylmethacrylate)

POMpolyoxometalate

PSpolystyrene

PSApoly(stearylacrylate)

PSSpoly(sodium-p-styrenesulfonate)

PVApoly(vinylalcohol)

P(VDF–TrFE)poly(vinylidenefluoride-trifluoroethylene)

PVPpoly(vinylphenyl)

PVPyrpoly(4-vinylpyridine)

PαMSpoly(α-methylstyrene)

RGOreducedgrapheneoxide

SAMself-assembledmonolayer

SAMFETsself-assembledmonolayerfield-effecttransistors

SEBSpoly(styrene-b-(ethylene-co-butylene)-b-styrene)

SEMscanningelectronmicroscopy

SLGsingle-layergraphene

SPsspiropyrans

SWCNTssingle-walledcarbonnanotubes

TCNB1,2,4,5-tetraacyanobenzene

TCNQtetracyanoquinodimethane

TEMtransmissionelectronmicroscopy

TIPS–pentacene6,13-bis(triisopropylsilylethynyl)pentacene

TTFtetrathiafulvalene

V D source–drainvoltage

V G gatevoltage

V th thresholdvoltage

WEGweakepitaxygrowth

W F workfunction

�� tot totalsurfaceenergy

��0 vacuumpermittivity

�� DT aligneddipolemomentoftheSAM

�� M–S M—Sbonddipoleinterface

φm electrodeworkfunction

1.1DifferentInterfacesinOFETs

WhenNobellaureateHerbertKroemercoinedthefamousphrasethat“theinterface isthedevice”[1],hepointedouttheessentialimportanceoftheinterfacesbetween differentmaterialsinanydeviceaction,especiallyforsemiconductingthin-film devices,whichhaveshownastonishingsuccessesinphotonicandelectronicapplications.Fromthepointofviewofatypicalorganicfield-effecttransistor(OFET), thedeviceperformanceismainlydeterminedbythepropertiesofthematerials usedandtheircorrespondinginterfaces.Ingeneral,anOFET[2–5]consistsofthree electrodes(source,drain,andgate),adielectriclayer,andanorganicsemiconductor (OSC)layer(Figure1.1).Toimprovethedeviceperformanceandevenbuild novelfunctionalities,interfaceengineeringoftheseheterojunctionsiscurrentlya researchfocusbecauseofitspromisingpotentialforfurtherapplicationsinbroad areasrangingfromintegratedcircuitsandenergyconversiontocatalysisandchemical/biologicalsensors[6–14].Infact,scientistsinavarietyofdisciplineshavebeen devotinggreateffortstothisconcept,whichstartedwithsimpleimprovementof thedeviceperformanceandhasbranchedoutindifferentdirections,indicatingthe interdisciplinaryoftheseefforts[15–18].Incomparisonwithtraditionalcomplementarymetaloxidesemiconductortransistors,theadvantagesofOFETsoriginate fromhowtheycanbemanufactured,includingconsiderablevarietyinmolecular design,lowcost,lightweight,mechanicalflexibility,solutionprocessability,and large-areafabrication.

TherearefourmajorcontactinterfacesinOFETs,namely,theinterfacewithinthe semiconductorlayers,semiconductor/electrodeinterface,semiconductor/dielectric interface,andsemiconductor/environmentinterface(Figure1.2).Ingeneral,the interfacewithinthesemiconductorlayers[19,20]containstraps,grainboundaries, andotherdefects,whichprovidescatteringsitesforcarriersandaredetrimental tochargetransport(Figure1.2a).Recentstudies[21,22],however,provedthat semiconductordopingandblendshadapositiveinfluenceonthecrystallinityand morphologyofthesemiconductorfilms.Severalstrategieshavebeendevelopedto achievehigh-qualitythinfilms,aswellastoformgoodheterojunctions,thusaffordingambipolarOFETsthatareusefulforbuildingfutureOFET-basedintegrated

InterfaceEngineeringinOrganicField-EffectTransistors,FirstEdition.XuefengGuoandHongliangChen. ©2023WILEY-VCHGmbH.Published2023byWILEY-VCHGmbH.

Figure1.1 SchematicillustrationofatypicalOFETarchitecture.

Figure1.2 InterfaceengineeringofinterfacesinOFETs.(a)Interfacewithinthe semiconductorlayers,(b)semiconductor/electrodeinterface,(c)semiconductor/dielectric interface,and(d)semiconductor/environmentinterface.SAM:self-assembledmonolayer; OSC:organicsemiconductor;CIL:chargeinsertionlayer.

devices,acceleratingchargeseparation,andimprovingthedeviceperformance.By designingmixedorsegregatedcrystalheterojunctionsmadeofOSCs,functional devicessuchasphotodetectors,memorydevices,andambipolartransistorscanbe realized.

AnotherimportantinterfaceinOFETsisthesemiconductor/electrodeinterface (Figure1.2b)[9,23–25],whichusuallydeterminestheefficiencyofcharge-carrier injectionandextraction.Bycarefullychoosingtheself-assembledmonolayer(SAM) orchargeinsertionlayer(CIL)tomodifymetalelectrodes,thecharge-injection barriercanbefine-tunedattheinterface,whichcouldsignificantlyreducethecontactresistancebetweensemiconductorsandelectrodes,thusenhancingthedevice performance.Moreinterestingly,byusingfunctionallayers,whosemolecular conformationorelectronicstructurecanbeswitchedbyexternalstimuli,thepropertiesofOFETscanrespondtoexternalsignals.Thisconceptsetsthefoundation forbuildingfunctionaldevicessuchasoptical/electricalswitches,memories,and photodetectors.

Thesemiconductor/dielectricinterfaceisavitalinterface[26,27]thatdominates carriertransport(Figure1.2c)because(i)chargecarriersaregeneratedatthe interfaceand(ii)theelectricalcurrentpathisthroughatmostthefirstfewlayers ofmoleculesattheinterface.Inaddition,thesurfaceenergyandmicrostructure ofthedielectricinterfacehaveasignificantimpactonthelocalmorphologyof thesemiconductorlayer.Therefore,modificationofthisinterfacebySAMsor stimuli-responsivelayersoffersanimportantanduniversalmethodologyto improvethedeviceperformanceandtoevenintegratenewmolecularfunctionalitiessuchasphoto-controllablememories,superconductors,andcharge-trap memoriesintoorganicelectricalcircuits.

Thesemiconductor/environmentinterfaceisusefulforbuildingfunctional OFETsforsensingapplications[12,13,15,17,28–30](Figure1.2d)bydirectly exposingthesemiconductorlayertotheenvironmentbeinganalyzed.Thismethod offerssomevaluableadvantagesoverothertechnologies,suchaslabel-freecapability,real-timedetection,andcompatibilitywithboththebiologicalsystemand theelectronicsindustry.Someintrinsicdrawbacks,however,hampertheuseof OFET-basedsensorsforpracticalsensingapplications.Thefirstisthediffusionof theanalyteintograinboundariesinthesemiconductors,causingeithertrapping ordopingofchargecarriers.Thiscouldresultinseriousproblemssuchasdevice instabilityandirreversibilitybecauseofthephysicallydestructiveinteraction betweensemiconductorsandanalytes.Second,becauseofthesignalamplification characteristicsofOFETs,anynonspecificresponseornoisewouldcauseinterferencewiththeintrinsicsignaloftheanalytes,leadingtoapseudo-signalandpoor selectivity.Therefore,rationalcontrolofinterfacialchargetransportiscrucialto controlthedopingeffects,increasethesensingselectivity/sensitivity,andeven installnewfunctionalities.

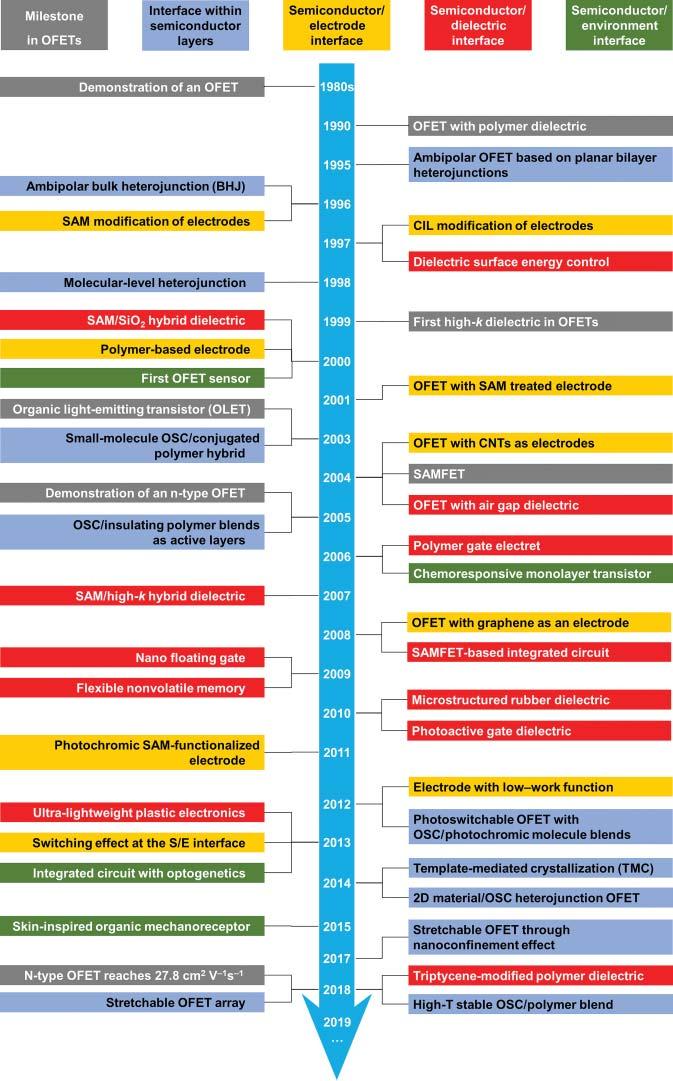

1.2BriefHistoricOverviewofInterfaceEngineering inOFETs

WehavesummarizedinFigure1.3thekeydevelopmentstogiveacomprehensivebig pictureoftheinterface-engineeredfunctionalOFETs.Startingfromthefirstdemonstration[31,32]ofOFETsinthe1980stotheirveryrecentapplications[21,29,30]in skinelectronics,theperformanceandfunctionalityofOFETshaveevolvedsimultaneouslyandpromotedeachother,sheddinglightontheirpotentialapplicationsin healthcare,wearableelectronics,anddegradableelectronics.

1.3ScopeoftheBook

Inthiscomprehensive book,weaimtoprovideasystematicsurveyofrecent significantadvancesindevelopingeffectivemethodologiesofinterfaceengineering inOFETs,fromfundamentalmodelstoexperimentaltechniques,forcreating high-performanceandmultifunctionaloptoelectronicdevices.InChapter2,we

Figure1.3 Timelineshowingkeydevelopmentsininterface-engineeredfunctionalOFETs [10,21,25,28,29,31,32,37,57,71,74,77,81,114,137,143–145,160,168,172,180,187, 205,237–240,298,312,315,326,331,333,348,353,359–361,376,393,397,417,447,459].

willsummarizeinterfacialmodificationmethodsinOFETs,whichincludephysical andchemicalmodificationmethods.Wewillnotgointodetailsofthem.Instead, summativetablesandfigureswillbepresenttocompareeachmethod.Then, wefocusonhowtouseinterfaceengineeringstrategiestoimprovetheinherent propertiesofOFETsatthesemiconductor/semiconductorinterface(Chapter3), semiconductor/electrodeinterface(Chapter4),semiconductor/dielectricinterface (Chapter5),semiconductor/environmentinterface(Chapter6),aswellasinterfacingorganicelectronicswithbiology(Chapter7).Bothareofgreatimportanceto liethefoundationoftheOFETresearch.Wealsoprovideacriticaldiscussionof thelimitationsandmainchallengesthatstillexistforthedevelopmentofpractical applicationsinChapter8.Suchabookwillbeinvaluableforbetterunderstanding fundamentalcharge-transportmechanismsattheinterfacesandwilloffernovel insightsintothedevicedesignconcept,thedevicefabricationprocess,andthe developmentoffuturemultifunctionalpracticaltransistors.

InterfacialModificationMethods

Overthepasttwodecades,extensiveefforts[6,8,9,16]havebeendevotedtothe modificationofinterfacesinorganicfield-effecttransistors(OFETs),includingphysicalmodificationmethods,suchasencapsulationorinsertiononthesurface,and chemicalmodificationmethods,suchascovalentlybondedself-assembledmonolayer(SAM)modification.

2.1NoncovalentModificationMethods

2.1.1ChargeInsertionLayerattheElectrodeSurface

BecausetheinjectionbarrieroriginatesgenerallyfromthegapbetweentheFermi levelofmetalelectrodesandthehighestoccupiedmolecularorbital(HOMO)/lowest unoccupiedmolecularorbital(LUMO)energylevelsoforganicsemiconductors (OSCs)accordingtotheenergeticalignment,areasonablesolutionistoinserta suitableadditionallayertomodifytheelectrodeandfunctionasaspringboard forchargecarriers,thuspossiblyovercomingthepoorinjection[70].Initially, thismethodofintroducingathinbufferlayerofseveralnanometersatmetal OSC/electrodeinterfaces,referredtoasachargeinsertionlayer(CIL)[71,72],had alreadybeenappliedtoincreasetheefficiencyoforganiclight-emittingdiodesby improvingthecontact.

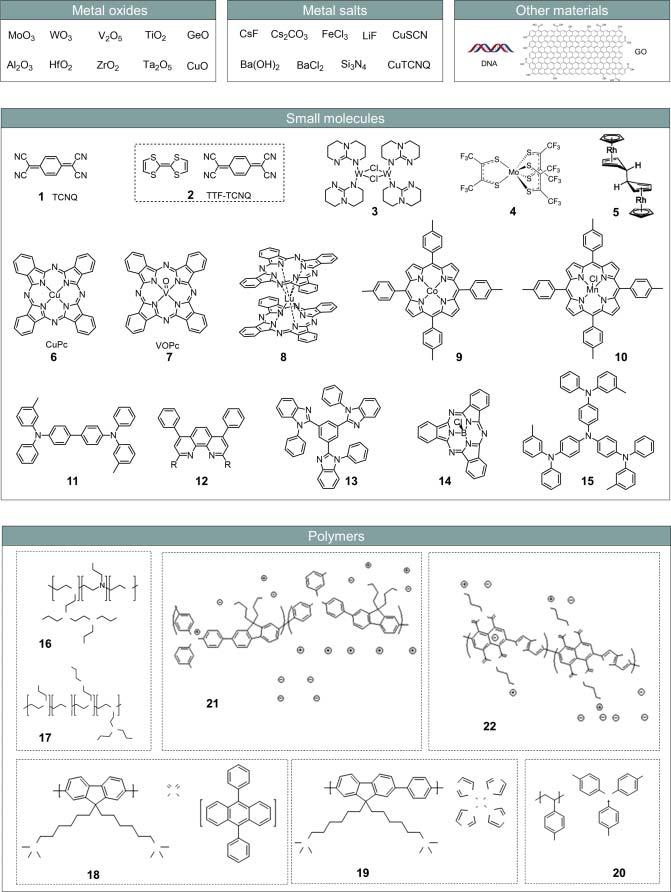

Apreliminarystudy[73]wascarriedoutbyHajlaouietal.,whoinsertedathinfilm oftetracyanoquinodimethane(TCNQ)(1),workingasmoleculardopant,between AuandOSCactivelayersinOFETstoachieveanincreasedholemobility.Byusing anultrathinLiFinterlayerasCILbetweenAlelectrodesandF16 CuPcactivelayers [33],enhancedn-channelperformancewasachieved.Sincethen,CILmodification hasattractedmoreandmoreattentionintermsofenhancingthehole/electroninjectionefficiency.Variousmaterials,suchasinorganiccompounds(metaloxidesand inorganicsalts)andorganiccompounds(smallmoleculesandpolymers),havebeen usedasCILs,asshowninFigure2.1.

Metaloxides[74](Figure2.1a)provideavarietyofcandidatesforCILsbecause oftheirwiderangeofworkfunctions.Transitionmetaloxidesinparticular InterfaceEngineeringinOrganicField-EffectTransistors,FirstEdition.XuefengGuoandHongliangChen.

Figure2.1 Chemicalstructuresofthechargeinsertionlayer(CIL).(a)Metaloxides, (b)metalsalts,(c)smallmolecules,(d)polymers,and(e)othermaterials.

[75,76],whoseworkfunctionsrangefromverylow(φ≈ 3eVforZrO2 )toextremely high(φ≈ 7eVforV2 O5 ),aresuitableformodifyingdifferentmetalswithmatched energylevels.AfterintroducingtheCIL,thethicknessofthedepletionlayer betweenthemetalandmetaloxidedecreasestoafewnanometers,producinga reachabledistancefortunnelinginjection,andthecontactresistancecouldbe significantlyreducedoncethetunnelinginjectionisdominant.TheCILlayercan

2.1NoncovalentModificationMethods 9 alsoactasaprotectionlayeragainstthediffusion[77]ofmetalsfromelectrodesor thepermeation[78]ofO2 orH2 Ointotheactivelayer,thusimprovingthedevice stability.

MetalsaltsareanotherbigfamilyofinorganicmaterialsworkingasCILs (Figure2.1b)[79,80].Theyexperienceasimilarmechanismasmetaloxides. OneofthebenefitsofusingmetalsaltsasCILsistheircompatibilitywiththe solution-processmethod.Forexample,CuSCN[81,82]canbespin-castedonAu electrodesasanovelCILwithanintrinsicelectron-blockingproperty.However, therearesomedrawbacksofmetalsaltswhenapplyingthemasCILs.First,the thicknessoftheCILaffectselectrontransport.AthickerlayerofCsF[83](more than0.6nm)decreasedthemobilityowingtoitsinsulatingnature.Second,when depositingaCILintoambipolarOFETsbyusingasinglecomponent,theoutcome performanceofp-andn-channelscannotbeenhancedsimultaneously.This problemcouldbesolvedbymixingtwodifferentmaterialstoformahybridCIL [84].Theinjectionbarrierfordifferenttypesofcarrierswastunedfinelyaccording tothemolecularratioofthetwocompounds.

WhenitcomestoorganicsmallmoleculesasCILs(Figure2.1c),i.e.chargetransfer(CT)complex(2)[85],metalcomplex(3–5)[86,87],metaltetraphenylporphyrinandphthalocyanine(6–10),[88]andN-heterocycliccompounds(11–15) [89],directCToccursattheinterfacebetweentheorganicCILandthesemiconductor,whichhelpstoreducethecontactresistancebytheadditionalinterface dipole.However,aproblemthatstillexistsisthepossibilityofmatrix–dopant hybridization[90,91].Theorganicpolymerswithdipolargroups[23,92,93] (16 and 17)(Figure2.1d)canalsoactaselectrodesurfacemodifierstoachieve electrodeswithalowworkfunction.Polyelectrolytes(18–22),whichcomprisethe groupscapableofbeingchargedwithcationsoranions,wereprovenrecentlytobe apromisingCILtoachieveohmiccontactswithawiderangeofworkfunctions (3.0–5.8eV)[23].

Othermaterials(Figure2.1e),suchasDNA[94]andgrapheneoxides(GOs) [95–97],havealsobeenusedasCILs.Thepresenceofphosphategroupsinthe DNAleadstoadipolelayer,whichcouldchangetheorientationinresponseto appliedgatevoltagesandenhancethechargeinjectionofbothtypesofcarriers. WhenGOswereappliedasCILsinOFETs,theimprovementindeviceperformance couldbeattributedtothegoodcontactnatureofcarbon-basedmaterialswith semiconductors,whichwillbediscussedinSection3.3.2.

2.1.2DielectricSurfacePassivationMethods

Polymerencapsulationisamainchoiceformodifyingtheinorganicdielectric surface.Mostofthepolymermodifier,forexamplepoly(imide-siloxane)[98], poly(4-vinylpyridine)(PVPyr)[99],andpolystyrene(PS)[100],areusedtochange thesurfaceenergyofthedielectricandthusinfluencethegrainsizeofOSCs growingwhereon.Thereisstilladebateonhowthesurfaceenergyofpolymer modifiersinfluenceperformanceofOSCthinfilms;butasageneralrule,thecloser thesurfaceenergyofthedielectriclayeristothatoftheOSC,thehigherthecarrier

2InterfacialModificationMethods

mobility[101].Morefundamentally,itisacompetitionbetweentheaggregation forcewithintheOSCandtheadsorptionofOSConthesubstrate.

Thepolymermodifiers,however,sufferfromhighroughnessandtrapdensity, whichhamperchargetransportonthesurface.Thesameproblemexistswhen directlyusinginsulatingpolymersasgatedielectrics[102–105].Theseapplications callfortheefficientsurfacemodificationmethodsofpolymerfilms.However,the lackoffunctionalgroupsmakesitveryhardtomodifypolymerdielectrics.Several strategieshavebeendevelopedrecentlytosolvethisproblem:

(i)Bydirectlydepositingabilayerdielectricconsistedofabulkdielectriclayerand anultrathininterfacelayer(Figure2.2a,b);

(ii)Byusingblendsoftwocomponentstoinduceaphase-separatedbilayerstructure(Figure2.2c,d);

(iii)Byutilizingamonolayercapableofself-assemblyonthepolymersurface (Figure2.2e–g).

Forthefirststrategy,abilayerpolymerdielectric(Figure2.2a)wasemployed[34], whichconsistedofabulklayerofelectropositivecopolymer(26)forinducingelectrostaticpolarizationalongthechannelandanultrathininterfacelayerof 23 on toptoformagoodinterfacewithOSCs.Thepolymerdielectricwaspreparedvia aone-step,low-temperature,solvent-freechemicalvapordepositionprocesswith differentratiosoftwomonomers 24 and 25 (Figure2.2b)[35].

Thesecondstrategycanberealizedbyblendingafluorinatedhigh-k polymer (27)withpoly(methylmethacrylate)(PMMA)(28)asadielectric[106].Generally, thepurehigh-k dielectriclayerof 27 canenhancetheholemobilitybutsuppress theelectronmobilitybecauseoftheinterfacialC–Fdipole.Intheblends,however, bothp-andn-channelbehaviorswereincreasedsimultaneouslyinambipolarpolymersbecauseoftheexistenceofverticalphaseseparationthatinducesaPMMA-rich regionadjacenttothesemiconductorlayer(Figure2.2c),leadingtoreducedinterfacialdipolardisorder(Figure2.2d).Thesediscoveriesprovidednewstrategiesfor designingdielectricmaterialsbychoosingmultiplecomponentswithproperchemicalandmorphologicalproperties.

Lastbutnotleast,thetechniqueofusingSAMsviacovalentbondingininorganic dielectricscouldnotworkwellonpolymersubstrates,becauseofthelackofparticularanchoringsitesonthepolymersurfacewhosechainsarerandomlyoriented.To overcomethisproblem,Yokotaetal.[108]appliedaparticularparaffinictriptycene (29)(Figure2.2f),whichcanformcompletelyorientedthinfilmswithahigh structuralorderfeaturing2Dnestedhexagonalpackingand1Dlayerstackingfor thesurfacefunctionalizationofapolymersubstrate.Thetriptyceneformednoncovalentlyonpolymersubstrates,wheretheparaffinicsidechainswerearranged verticallytothesubstrate,thusequalizingthesurfacepropertiesofthesesubstrates (Figure2.2e)[107].Withafew-layertriptycenefilm,thesurfaceenergiesofdifferentgatedielectricswerealmostidentical(∼22.2mJm 2 ),thusensuringthehigh crystallinityandenhancedstructuralintegrityofOSCs(Figure2.2g).Thisisamore generalstrategybydepositingafew-layerfilmoftriptyceneonpolymersubstrates, sheddingnewlightoninterfaceengineeringoftheOSC/polymerdielectricinterface.

Verticalphaseseparation

P(VDF-TrFE)richregion

Tripodalparaffinic functionalizationtriptycenes

2.1NoncovalentModificationMethods 11

Figure2.2 Modificationofpolymerdielectrics.(a)Schematicrepresentationshowingthe bilayerdielectricmadefromaninitiatedchemicalvapordepositionprocess.(b)Molecular structuresoftheinterfaciallayerandthebulkdielectriclayer.(c)Aschematicstructureof theverticalphaseseparationoftheblendeddielectric.(d)Schematicrepresentation showingtheeffectofthepolaronicdisorderandcarrierconcentrationinOFETswiththree dielectrics.(e)Afew-layertriptycenefilmfeaturing2Dnestedhexagonalpackingand one-dimensional(1D)layerstackingonaparylenedielectric.(f)Molecularstructureofthe triptycenemolecule.(g)Atomicforcemicroscopy(AFM)heightimagesofevaporatedOSC filmsonparylene(top)andtriptycene-coatedparylene(bottom)gatedielectrics. Source:(a,b)AdaptedfromPaketal.[34].(c,d)AdaptedfromKhimetal.[106]. (e–g)ReproducedfromYokotaetal.[107],©2018SpringerNature.

2.2CovalentModificationMethods

2.2.1SAMModificationofElectrodes

Themetalelectrodesurface,whichiscapableofabsorbingadventitiousorganic materials,offersagoodplatformforstudyingSAMsformedbychemisorption. SAMmodificationisnotonlyauniversalmethodtomodifythesurfaceproperties[36,109–112],butalsoamethodforprovidingmorefunctionalities[37,113]. Herein,wefocusonSAMmodificationmethodsappliedtothemetalelectrodesin OFETs(Figure2.3).

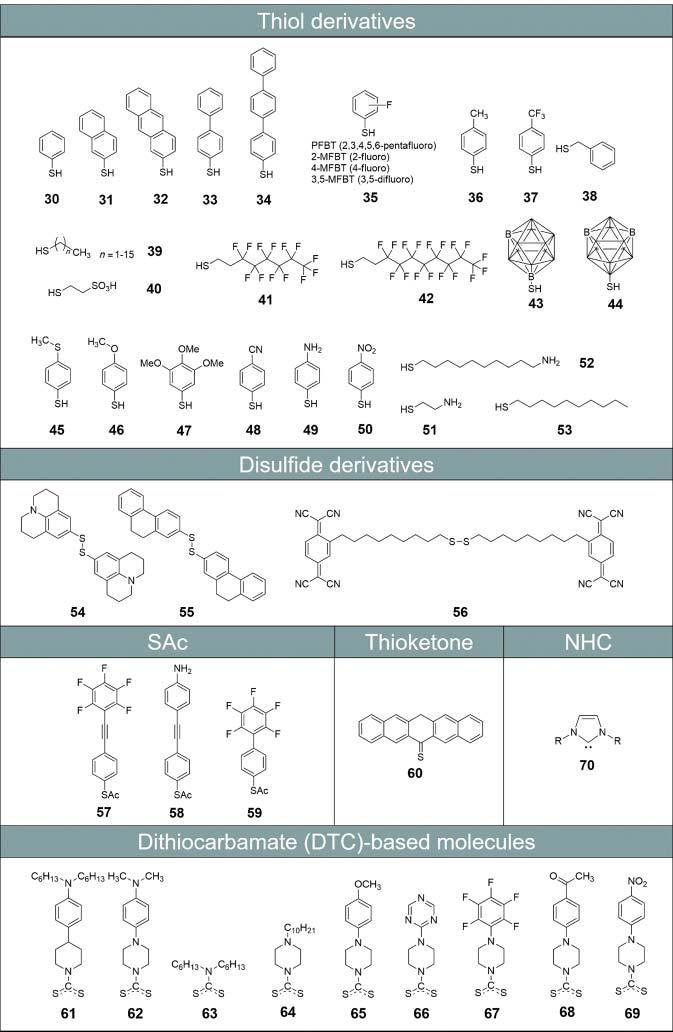

CommonlyusedSAMmoleculesarethiolderivatives(30–53),whichhavea sulfhydrylgroupfordockingtothesurfacesofmetalssuchasAu.Thisforms metal–sulfurinteractionsthroughthesulfurlong-pairelectrons,calledthe thiolate—goldbond(Au—S),whosestrengthisclosetothatoftheAu—Aubond [38,114].Organiccompoundswithdisulfide(S–S)(54–56)orsulfideacetyl(–SAc) (57–59)bondscanalsoformSAMsonAuorAgelectrodesurfaces[115].

Thioketone(60),whichisstructurallysimilartopentacene,wasusedasaSAM tomodifyAuelectrodespriortothedepositionofpentacene[116],whichinduced acomplementarysurfaceforthegrowthofpentaceneandreducedthecontact resistance.Inaddition,dithiocarbamate(DTC)-basedmolecules(61–69)havebeen proventobestablyadsorbedonmetalsundervarioustypesofenvironmental stresses[117],andcouldreducetheworkfunctionofnoblemetals(AuandAg)to anultralowvalue(suchas ∼3.1eVforAu)[118].Recently, N -heterocycliccarbenes (NHCs)(70)emergedasaversatilesurfacemodificationofgoldsurfaces[119,120], exhibitinghigherstabilityunderharshconditionsincontrasttothemostcommonly usedlinearorganosulfurligands.

Despitetheprogress,greatchallengesremainintheSAMmodificationofmetal electrodes.Therelativelypoormechanicalperformanceandscratchresistancehampertheirpracticalapplicationandcommercialization.Carbonnanomaterials,i.e. carbonnanotubes(CNTs)andgraphene(Gr),haveemergedaspotentialelectrodes withhighconductivity,stability,andproducibility.However,theirchemicalinertnessmakesthemhardtofunctionalizewithoutbreakingthewell-definedstructures andscarifyingtheirperformances.Moreover,themassproduction,purification,and integrationofcarbonnanomaterialsaselectrodesisahugesystematicproject.There isstillalongwaytogo.

2.2.2SAMModificationofDielectrics

TheSAMmodificationstrategyisworthbeinghighlightedattheOSC/dielectric interface.Basedondifferentdielectricmaterials,wesummarizethreeaspectsto discussthetopicindetail:(i)SAM/SiO2 dielectrics,(ii)SAM/high-k dielectrics, and(iii)self-assembledmonolayerfield-effecttransistors(SAMFETs).Interms ofdifferenttypesofmoleculesthathavebeenused[121],twocategoriesofthe most-commonly-usedSAMmoleculesarediscussed:

(i)Silane-basedSAMmolecules[122],whichprefertoreactwiththehydroxyl groupof–SiOHonthesilicon-baseddielectrics(SiO2 andSi3 N4 )toformSAMs viacovalentlinkageofSi—O—Sibonds.

Figure2.3 ChemicalstructuresofSAMsusedtomodifymetalelectrodes.

2InterfacialModificationMethods

(ii)Thephosphonicacid(PA)anditsphosphonateesterderivative-basedSAM molecules[111],whichcanformPA–SAMsonalargerangeofinorganicoxide dielectrics,includinghigh-k materials,bymultidentatebindingofstrong covalentP–O–Manchoring(Mstandsformetalatom).Undernormalambient conditions,phosphonicacidmoleculesdonotreactchemicallyonthesurface ofSiO2 [123].

2.2.2.1SAM/SiO2 Dielectrics

Surfacemodificationwithorganosilanes(71–102)(Figure2.4)hasbeenacommon methodforalongtimetoprepareSAMsonawiderangeofsurfacesbearing–OH groups[124],suchassilica,aluminumoxide,andzincoxides.Themodificationcan bedonebyreactionsinsolutionorinthevaporphase.Thechallengeisthatuniformsilanemonolayersarestilldifficulttoobtain[121],thuslimitingthedevice performancetosomeextent.

TheprocessingconditionshaveagreatimpactonthequalityoftheresultingSAM. TheSAMcoveragewasfoundtobeverysensitivetothepretreatmentconditions.In general,vapor-depositedSAMsarelikelytoresultinhighbutnotfullcoverage,differentfromthesolution-processingprocedure.Theoretically,fullsurfacepassivation andzero-onsetvoltageareonlypossibleatnear100%SAMcoverage,andifthecoverageisincompleteoruncontrolled,highvariabilityintheonsetvoltageoccurs.A partiallycoveredgate-dielectricSAMwouldcausetwoimpactsonthetransportofan OSC[125].Thefirstimpactisthesurface-inducedelectronicdisorderintheadjacent semiconductor,whichbroadenedthedistributionofcharge-transportstates.The secondimpactistherigidshiftofthetransportlevelsofthesemiconductorowingto electrostaticinteractionsbetweentheSAMandthesemiconductor,inducingeither holeorelectronaccumulationaccordingly.Togetacomprehensiveunderstandingof therelationshipbetweenSAMmaterials,preparationmethods,andthefield-effect transistor(FET)performances,wehavelistedbelowrecentworksofSAM-modified dielectricsurfaces,whichareshowninTable2.1.

2.2.2.2SAM/High-k Dielectrics

High-k materials[144]includedifferentkindsofmaterials,suchasthemostabundantinorganicoxides[145]andpolymers[146,147],aswellashybriddielectrics [148].Wefocushereonthewidelyusedinorganicoxidehigh-k materialstoachieve low-voltageOFETs.Theyareusuallypreparedbysolutionprocessingandvapor deposition,suchasthesol–gelandatomiclayerdeposition(ALD)methods.Owing tosomedistinctcharacteristicsofhigh-k metaloxides,i.e.(i)theunavoidable charge-carriertrapsitesonthesurface(usuallyassociatedwith–OHgroups), (ii)theinducedionicpolarizationowingtotheinteractionbetweenchargecarriers andthehigh-k lattice,and(iii)thesurfaceroughness,theycanadverselyaffect thedeviceperformance.Inordertomitigatetheproblems,surfacemodificationis neededforcontrollingthesurfacepropertiesofhigh-k dielectrics.

PA–SAMs(107–134)(Figure2.5)arepreparedeasilyinairandareabletoform well-ordered,stronglycovalentlybondedfilmsonhigh-k oxidesurfaces[149]. PA–SAMsshowbetterstabilitytomoistureandlesstendencytohomocondensation