ContEnts

preface xix

Part o n E drugs in society/ drugs in our Lives 1

Chapter 1

Drugs and Behavior today 1

By the Numbers . . . 2

Social Messages About Drug Use 3

Two Ways of Looking at Drugs and Behavior 4

A Matter of Definition: What Is a Drug? 5

■ hE a L th Lin E : Defining Drugs: Olive Oil, Curry Powder, and a Little Grapefruit? 6

Instrumental Drug Use/Recreational Drug Use 6

Drug Misuse or Drug Abuse? 7

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Drug Abuse and the College Student: An Assessment Tool 8

Drugs in Early Times 9

Drugs in the Nineteenth Century 10

Drugs and Behavior in the Twentieth Century 11

Drugs and Behavior from 1945 to 1960 12

Drugs and Behavior after 1960 12

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 1.1: Understanding the History of Drugs and Behavior 13

Present-Day Attitudes toward Drugs 14

Patterns of Drug Use in the United States 14

Illicit Drug Use among High School Seniors 15

Illicit Drug Use among Eighth Graders and Tenth Graders 16

Illicit Drug Use among College Students 16

Alcohol Use among High School and College Students 16

Tobacco Use among High School and College Students 17

Drug Use and Drug Perceptions 17

Illicit Drug Use among Adults Aged Twenty-Six and Older 18

Making the Decision to Use Drugs 19

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 1.2: Understanding Present-Day Drug Use in the United States 19

Specific Risk Factors 19

Specific Protective Factors 21

Present-day Concerns 21

Club Drugs 21

Nonmedical Use of Prescription Pain Relievers 21

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Facts about Club Drugs 22

Nonmedical Use of Prescription Stimulant Medications 23

Nonmedical Use of Over-the-Counter Cough-and-Cold Medications 23 Why Drugs? 23

■ Portrait: From Oxy to Heroin— The Life and Death of Erik 24

Summary 24 / Key Terms 25 / Endnotes 26

Chap t er 2

Drug-taking Behavior: personal and social issues 28

By the Numbers . . . 29 Drug Toxicity 30

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Acute Toxicity in the News: Drug-Related Deaths 32

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 2.1: Understanding Dose-Response Curves 33 The DAWN Reports 33 Emergencies Related to Illicit Drugs 34 Drug-Related Deaths 34 Judging Drug Toxicity from Drug-Related Deaths 35 Demographics and Trends 35 From Acute Toxicity to Chronic Toxicity 36 Behavioral Tolerance and Drug Overdose 37

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 2.2: Understanding Behavioral Tolerance through Conditioning 38

Physical and Psychological Dependence 39 Physical Dependence 39 Psychological Dependence 39

Diagnosing Drug-Related Problems: The Health Professional’s Perspective 41

Special Circumstances in Drug Abuse 43

Drug Abuse in Pregnancy 43

Drug Abuse and HIV Infection 43

■ hE a L th Lin E : Effects of Psychoactive Drugs on Pregnant Women and Newborns 44 Drugs, Violence, and Crime 45 Pharmacological Violence 45

Economically Compulsive Violence 46 Systemic Violence 47

Governmental Policy, Regulation, and Laws 48 Efforts to Regulate Drugs, 1900–1970 48

Rethinking the Approach toward Drug Regulation, 1970–Present 49

Drug Law Enforcement and Global Politics 50

■ Portrait: Pablo Escobar—Formerly Known as the Colombian King of Cocaine 51

■ hE a L th Lin E : Harm Reduction as a National Drug-Abuse Policy 53

Summary 54 / Key Terms 55 / Endnotes 55

■ Point/Count E r P oint i : Should We Legalize Drugs in General? 58

Chapter 3

how Drugs Work in the Body and on the Mind 60

By the Numbers . . . 61

How Drugs Enter the Body 61

Oral Administration 61

Injection 62

Inhalation 63

Absorption through the Skin or Membranes 63 How Drugs Exit the Body 64

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Ways to Take Drugs: Routes of Administration 65

Factors Determining the Behavioral Impact of Drugs 66 Timing 66

Drug Interactions 67

Cross-Tolerance and Cross-Dependence 67

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 3.1: Understanding Drug Interactions 67

■ hE a L th aLE rt: Adverse Effects of Drug–Drug and Food–Drug Combinations 68

Individual Differences 69

Introducing the Nervous System 69

The Peripheral Nervous System 70

Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Responses 70

The Central Nervous System 71

Understanding the Brain 72

The Hindbrain 73

The Midbrain 73

The Forebrain 73

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 3.2: Understanding Drugs and Brain Functioning 74

Understanding the Neurochemistry of Psychoactive Drugs 74

Introducing Neurons 74

Neuronal Communication 75

Drug Influences on Neuronal Communication 76

The Major Neurotransmitters in Brief: The Big Seven 76

Physiological Aspects of Drug-Taking Behavior 78

The Blood–Brain Barrier 78

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Endorphins, Endocannabinoids, and the “Runner’s High” 79

Biochemical Processes Underlying Drug Tolerance 80

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 3.3: Understanding Cross-Tolerance and Cross-Dependence 80

Physiological Factors in Psychological Dependence 81

■ hE a L th Lin E : Drug Craving and the Insula of the Brain 82

Psychological Factors in Drug-Taking Behavior 82 Expectation Effects 83

■ Portrait: Nora D. Volkow—A ScientistGeneral in the War on Drugs 84 Drug Research Procedures 85

Summary 85 / Key Terms 86 / Endnotes 86

Part two Legally restricted drugs in our society 89

Chapter 4 the Major stimulants: Cocaine and amphetamines 89

By the Numbers . . . 90

The History of Cocaine 90 Cocaine in Nineteenth-Century Life 91

■ hE a L th aLE rt: Cocaine after Alcohol: The Risk of Cocaethylene Toxicity 91

Freud and Cocaine 92

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: What Happened to the Coca in Coca-Cola? 93

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 4.1: Understanding the History of Cocaine 94

Acute Effects of Cocaine 94

Chronic Effects of Cocaine 95

■ hE a L th aLE rt: The Physical Signs of Possible Cocaine Abuse 95

Medical Uses of Cocaine 96

How Cocaine Works in the Brain 96

Present-Day Cocaine Abuse 96

From Coca to Cocaine 97 From Cocaine to Crack 97

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Crack Babies

Revisited: What Are the Effects? 99

Patterns of Cocaine Abuse 100

Treatment Programs for Cocaine Abuse 100

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Paco: A Cheap Form of Cocaine Floods Argentine Slums and Beyond 100

■ Portrait: Robert Downey Jr. and Others—Cleaning Up after Cocaine 101

Amphetamines 103

The Different Forms of Amphetamines 103

The History of Amphetamines 104

How Amphetamines Work in the Brain 104

Acute Effects of Amphetamines 104

Chronic Effects of Amphetamines 105 Methamphetamine Abuse 105

Present-Day Patterns of Methamphetamine Abuse 105

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Methamphetamine and the Heartland of America 107

Methamphetamine-Abuse Treatment 107

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 4.2: Understanding Patterns of Cocaine and Methamphetamine Abuse 108

Medical Uses for Amphetamines and Similar Stimulant Drugs 108

■ hE a L th Lin E : “Bath Salts” as a New Form of Stimulant Abuse 109

Stimulant Medications for ADHD 109

Other Medical Applications 110

Stimulant Medication and Cognitive Enhancement 111

Summary 111 / Key Terms 112 / Endnotes 112

■ Point/Count E r P oint ii : Should Cognitive Performance-Enhancing Drugs Be Used by Healthy People? 116

Chapter 5

Opioids: Opium, heroin, and Opioid pain Medications 118

By the Numbers . . . 119

Opium in History 119

The Opium War 121

Opium in Britain and the United States 122

Morphine and the Advent of Heroin 123

Opioids in American Society 124

Opioid Use and Heroin Abuse after 1914 124

Heroin Abuse in the 1960s and 1970s 125

Heroin and Other Opioids since the 1980s 126

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 5.1: Understanding the History of Opium and Opioids 127

Effects on the Mind and the Body 127

How Opioids Work in the Brain 128

Patterns of Heroin Abuse 129

Tolerance and Withdrawal Symptoms 130

The Lethality of Heroin Abuse 130

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 5.2: Understanding the Effects of Administering and Withdrawing Heroin 131

Heroin Abuse and Society 132

Treatment for Heroin Abuse 132

Heroin Detoxification 132

Methadone Maintenance 133

Alternative Maintenance Programs 134

Behavioral and Social-Community Programs 134

Medical Uses of Opioid Drugs 134

■ hE a L th aLE rt: Sustained-Release Buprenorphine: A New Era in Heroin-Abuse Treatment 135

Beneficial Effects 135

Prescription Pain Medication Misuse and Abuse 137

OxyContin Abuse 137

Responses to OxyContin Abuse 137

■ Portrait: David Laffer—Pharmacy Robber and Killer of Four 138

Abuse of Other Opioids Pain Medications 138

Prevalence of Nonmedical Use of Opioid Pain Medications 138

Summary 139 / Key Terms 140 / Endnotes 140

Chapter 6

lsD and Other hallucinogens 143

By the Numbers . . . 144

A Matter of Definition 144

Classifying Hallucinogens 145

Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) 146

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Strange Days in Salem: Witchcraft or Hallucinogens? 147

The Beginning of the Psychedelic Era 147

■ Portrait: Timothy Leary—Nutty Professor or Psychedelic Visionary? 149

Acute Effects of LSD 149 Effects of LSD on the Brain 150

Patterns of LSD Use 151

Facts and Fiction about LSD 151

Will LSD Produce Substance Dependence? 151

Will LSD Produce a Panic Attack or Psychotic Behavior? 151

Will LSD Increase Your Creativity? 152

Will LSD Damage Your Chromosomes? 152

■ hE a L th aLE rt: Emergency Guidelines for a Bad Trip on LSD 152

Will LSD Have Residual (Flashback) Effects? 153

Will LSD Increase Criminal or Violent Behavior? 153

Psilocybin and Other Hallucinogens Related to Serotonin 154

Lysergic Acid Amide (LAA) 154

■ hE a L th Lin E : Bufotenine and the Bufo Toad 155

Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) 155

Harmine 156

Hallucinogens Related to Norepinephrine 156

Mescaline 156

DOM 156

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Present-Day

Peyotism and the Native American Church 157

MDMA (Ecstasy) 157

■ hE a L th aLE rt: MDMA Toxicity: The Other Side of Ecstasy 158

Hallucinogens Related to Acetylcholine 159

Amanita muscaria 159

The Hexing Drugs and Witchcraft 159

Miscellaneous Hallucinogens 160

Phencyclidine (PCP) 161

Acute Effects of PCP 161

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 6.1: Understanding the Diversity of Hallucinogens 161

Patterns of PCP Abuse 162

Ketamine 162

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 6.2: Understanding PCP 163

Salvia divinorum 163

Summary 163 / Key Terms 165 / Endnotes 165

Chapter 7

Marijuana

167

By the Numbers . . . 168

A Matter of Terminology 168

The History of Marijuana and Hashish 170

Hashish in the Nineteenth Century 170

Marijuana and Hashish in the Twentieth Century 170

The Anti-Marijuana Crusade 171

Challenging Old Ideas about Marijuana 172

Acute Effects of Marijuana 172

Acute Physiological Effects 173

Acute Psychological and Behavioral Effects 173

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 7.1: Understanding the Effects of Marijuana 174

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: The Neurochemical “Yin and Yang” of Cannabis 175

Effects of Marijuana on the Brain 175

Chronic Effects of Marijuana 176

Tolerance 176

Withdrawal and Dependence 176

Cardiovascular Effects 177

Respiratory Effects and the Risk of Cancer 177

Effects on the Immune System 178

Effects on Sexual Functioning and Reproduction 178

Long-Term Cognitive Effects and the Amotivational Syndrome 178

The Gateway Hypothesis 179

The Sequencing Question 179

The Association Question 180

The Causation Question 180

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 7.2:

Understanding the Adverse Effects of Chronic Marijuana Abuse 181

Patterns of Marijuana Smoking 181

Causes for Concern 182

■ hE a L th aLE rt: A Synthetic Marijuana called Spice 182

Medical Marijuana 183

Muscle Spasticity and Chronic Pain 183

■ Portrait: Marcy Dolin—Marijuana

Self-Medicator 183

Nausea and Weight Loss 184

The Medical Marijuana Controversy 184

The Issues of Decriminalization and Legalization 185

Summary 186 / Key Terms 187 / Endnotes 187

Part thr EE Legal drugs in our society 191

Chapter 8

alcohol: social Beverage/social Drug 191

By the Numbers . . . 192

What Makes an Alcoholic Beverage? 192

Alcohol Use through History 194

Alcohol in Nineteenth-Century America 194

The Rise of the Temperance Movement 195

The Road to National Prohibition 196

The Beginning and Ending of a “Noble Experiment” 196

Present-Day Alcohol Regulation by Taxation 196

Patterns of Alcohol Consumption Today 197

Overall Patterns of Alcohol Consumption 197

■ hE a L th Lin E : Multiple Ways of Getting a Standard Drink 198

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Visualizing the Pattern of Alcohol Consumption in the United States 199

Problematic Alcohol Consumption among College Students 200

Alcohol Consumption among Adolescents 200

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 8.1:

Understanding Alcoholic Beverages 201

The Pharmacology of Alcohol 201

The Breakdown and Elimination of Alcohol 201

Measuring Alcohol in the Blood 202

■ hE a L th Lin E : Gender, Race, and Medication: Factors in Alcohol Metabolism 203

Effects of Alcohol on the Brain 204

Acute Physiological Effects 204

Toxic Reactions 205

Heat Loss and the Saint Bernard Myth 205

■ hE a L th aLE rt: Emergency Signs and Procedures in Acute Alcohol Intoxication 205

Diuretic Effects 206

Effects on Sleep 206

Effects on Pregnancy 206

Interactions with Other Drugs 206

Hangovers 206

Acute Behavioral Effects 207

Blackouts 208

Driving Skills 208

Preventing Alcohol-Related Traffic Fatalities among Young People 209

■ Portrait: Candace Lightner—Founder of MADD 209

Alcohol, Violence, and Aggression 210

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Alcohol, Security, and Spectator Sports 211

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Caffeine, Alcohol, and the Dangers of Caffeinated Alcoholic Drinks 212 Sex and Sexual Desire 212

Alcohol and Health Benefits 212

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 8.2: Understanding the Data from Balanced Placebo Designs 213

■ hE a L th aLE rt: Guidelines for Responsible Drinking 214

Strategies for Responsible Drinking 215

Summary 215 / Key Terms 216 / Endnotes 216

Chapter 9

Chronic

alcohol abuse and alcoholism 220

Alcoholism: Stereotypes, Definitions, and Life Problems 221

By the Numbers . 221

Problems Associated with a Preoccupation with Drinking 221

Emotional Problems 223

Vocational, Social, and Family Problems 223

Physical Problems 223

■ hE a L th Lin E : A Self-Administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) 224

Hiding the Problems: Denial and Enabling 224

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 9.1: Understanding the Psychology of Alcoholism 225

Alcohol Abuse and Alcohol Dependence: The Health Professional’s Perspective 225

Physiological Effects of Chronic Alcohol Use 226

Tolerance and Withdrawal 226

Liver Disease 226

Cardiovascular Problems 227

Cancer 227

Dementia and Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome 228

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) 228

■ hE a L th Lin E : Alcoholism Screening Instruments in Professional Use 230

Patterns of Chronic Alcohol Abuse 230

Gender Differences in Chronic Alcohol Use 231

Alcohol Abuse among the Elderly 231

The Family Dynamics of Alcoholism: A Systems Approach 232

Children of an Alcoholic Parent or Parents 232

The Genetics of Alcoholism 233

The Concept of Alcoholism as a Disease 234

Approaches to Treatment for Alcoholism 235

Biologically Based Treatments 235

■ Portrait: Bill W. and Dr. Bob—Founders of Alcoholics Anonymous 237

Alcoholics Anonymous 237

■ hE a L th Lin E : Is Controlled Drinking Possible for Alcoholics? 238

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: The Non-Disease Model of Alcoholism and Other Patterns of Substance Abuse 239

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 9.2: Understanding Alcoholics Anonymous 240 SMART Recovery 240

Chronic Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in the Workplace 240

Summary 241 / Key Terms 242 / Endnotes 242

■ Point/Count E r P oint iii : Should Alcoholism Be Viewed as a Disease? 246

Chapter 10

nicotine and tobacco Use 248

By the Numbers . . . 249

Tobacco Use through History 249

Politics, Economics, and Tobacco 250

Snuffing and Chewing 250

Cigars and Cigarettes 250

Tobacco in the Twentieth Century 251

Health Concerns and Smoking Behavior 252

■ hE a L th Lin E : African Americans, Smoking, and Mentholated Cigarettes 252

The Tobacco Industry Today 253

The Tobacco Settlement of 1998 254

The Tobacco Control Act of 2009 254

Tobacco Regulation and Global Economics 254 What’s in Tobacco? 254

Carbon Monoxide 255

Tar 255

Nicotine 256

The Dependence Potential of Nicotine 256

The Titration Hypothesis of Nicotine Dependence 256

Tolerance and Withdrawal 257

Health Consequences of Tobacco Use 257

■ hE a L th Lin E : Visualizing 400,000 to 440,000 Annual Tobacco-Related Deaths 257

Cardiovascular Disease 257

Respiratory Diseases 258

Lung Cancer 259

Other Cancers 259

Special Health Concerns for Women 260

The Hazards of Environmental Smoke 260

■ hE a L th aLE rt: Signs of Trouble from Smokeless Tobacco 261

Patterns of Smoking Behavior and Use of Smokeless Tobacco 261

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 10.1: Understanding the Effects of Tobacco Smoking 262 The Youngest Smokers 262

Attitudes toward Smoking among Young People 262

Smokeless Tobacco 263

Cigars 264

Tobacco Use around the World 264

■ Portrait: Sigmund Freud—Nicotine

Dependence, Cigars, and Cancer 265

Quitting Smoking: The Good News and the Bad 265

The Good News: Undoing the Damage 266

The Bad News: How Hard It Is to Quit 266

■ hE a L th Lin E : How to Succeed in Quitting Smoking—By Really Trying 268

Nicotine Gums, Patches, Sprays, and Inhalers 268

The Role of Physicians in Smoking Cessation 268

A Final Word 269

Summary 270 / Key Terms 271 / Endnotes 271

Chapter 11

275

Coffee 276

By the Numbers . . . 276

Coffee in Britain and North America 276

Major Sources of Coffee 277

The Caffeine Content in Coffee 277

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Why There Are No (Live) Flies in Your Coffee 278

Tea 278

Tea in Britain and North America 278

The Chemical Content in Tea 279

Chocolate 279

How Chocolate Is Made 280

The Chocolate Industry Today 280

The Xanthine Content in Chocolate 280

■ hE a L th Lin E : Chocolate, Flavanols, and Cardiovascular Health 281

Soft Drinks 281

Caffeine from OTC Drugs and Other Products 281

■ Portrait: Milton S. Hershey and the Town Built on Chocolate 282

Caffeine as a Drug 282

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 11.1: Understanding Caffeine Levels in Foods and Beverages 283

Effects of Caffeine on the Body 283

Effects of Caffeine on Behavior 283

Potential Health Benefits 284

Potential Health Risks 285

Cardiovascular Effects 285

Osteoporosis and Bone Fractures 285

■ hE a L th Lin E : Coffee, Genes, and Heart Attacks 286

Breast Disease 286

Effects during Pregnancy and Breastfeeding 286

Panic Attacks 286

Dependence, Acute Toxicity, and Medical Applications 287

Tolerance 287

Withdrawal 287

Craving 287

Acute Toxicity of Caffeine 287

Prescription Drugs Based on Xanthines 288

Caffeine and Young People: A Special Concern 288

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Energy Shots 289

Summary 289 / Key Terms 290 / Endnotes 290

Part four Enhancers and depressants 293

Chapter 12 performance-enhancing Drugs and Drug testing in sports 293

Drug-Taking Behavior in Sports 294 By the Numbers . . . 294

What Are Anabolic Steroids? 294

Anabolic Steroids at the Modern Olympic Games 295

■ Portrait: Lance Armstrong: From Honor to Dishonor 297

Anabolic Steroids in Professional and Collegiate Sports 297

Performance-Enhancing Drug Abuse and Baseball 297

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Suspension

Penalties for Performance-Enhancing Drug Use in Sports 298

The Hazards of Anabolic Steroids 299

Effects on Hormonal Systems 299

Effects on Other Systems of the Body 300

Psychological Problems 300

Special Problems for Adolescents 301

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 12.1: Understanding the Effects of Anabolic Steroids 301

Caffeine

Patterns of Anabolic Steroid Abuse 301

The Potential for Steroid Dependence 302 Counterfeit Steroids and the Placebo Effect 303

■ hE a L th aLE rt: The Symptoms of Steroid Abuse 304

Nonsteroid Hormones and Performance-Enhancing Supplements 304

Human Growth Hormone 304

Dietary Supplements as Performance-Enhancing Aids 305

Nonmedical Use of Stimulant Medication in Baseball 306

Current Drug-Testing Procedures and Policies 306

The Forensics of Drug Testing 306

■ d rugs . . . in f o C us: Pharmaceutical Companies and Anti-Doping Authorities: A New Alliance 307

Sensitivity and Specificity 308

Masking Drugs and Chemical Manipulations 308

Pinpointing the Time of Drug Use 309

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 12.2: Understanding Drug Testing 310

The Social Context of Performance-Enhancing Drugs 310

Summary 311 / Key Terms 312 / Endnotes 312

Chapter 13

Depressants and inhalants 315

By the Numbers . . . 316

Barbiturates 316

Categories of Barbiturates 317

Acute Effects of Barbiturates 317

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Is There Any Truth in “Truth Serum”? 318

Chronic Effects of Barbiturates 319

Current Medical Uses of Barbiturates 319 Patterns of Barbiturate Abuse 319

Nonbarbiturate Sedative-Hypnotics 320

The Development of Antianxiety Drugs 320

Benzodiazepines 321

Medical Uses of Benzodiazepines 321

Acute Effects of Benzodiazepines 322

Chronic Effects of Benzodiazepines 322

How Benzodiazepines Work in the Brain 323 Patterns of Benzodiazepine Misuse and Abuse 323

Nonbenzodiazepine Depressants 324

■ hE a L th aLE rt: The Dangers of Rohypnol as a Date-Rape Drug 324

Zolpidem and Eszopiclone 325

Buspirone 325

Beta Blockers 325

Antidepressants 325

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 13.1: Understanding the Abuse Potential in Drugs 326

A Special Alert: The Risks of GHB 326

Acute Effects 326

Protective Strategies for Women 326

■ Portrait: Patricia White, GHB, and the “Perfect” Crime 326

Inhalants through History 327

Nitrous Oxide 328

Ether 329

Glue, Solvent, and Aerosol Inhalation 329

The Abuse Potential of Inhalants 329

Acute Effects of Glues, Solvents, and Aerosols 330

The Dangers of Inhalant Abuse 330

■ hE a L th aLE rt: The Signs of Possible Inhalant Abuse 330 Patterns of Inhalant Abuse 331

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Resistol and Resistoleros in Latin America 332

The Dependence Potential of Chronic Inhalant Abuse 333

Responses of Society to Inhalant Abuse 333

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 13.2: Understanding the History of Inhalants 334

Summary 334 / Key Terms 335 / Endnotes 336

Part five Medicinal drugs 339

Chapter 14

prescription Drugs, Over-theCounter Drugs, and Dietary supplements 339

By the Numbers . . . 340

The History of Prescription Drug Regulations 341 Procedures for Approving Prescription Drugs 342

Phases of Clinical Testing for Prescription Drugs 342

Patents and Generic Forms of Prescription Drugs 344

Speeding Up the FDA Approval Process 344

Procedures for Approving OTC Drugs 345

Are FDA-Approved Drugs Safe? 346

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 14.1: Understanding the FDA Approval Process 346

The Issue of Speed versus Caution 346 Patterns of Prescription Drug Misuse 347

Unintentional Drug Misuse through Prescription Errors 347

■ hE a L th Lin E : The Potential for Death by Prescription Error 348

■ hE a L th Lin E : Doctor Shopping for Prescription Drugs 349 Patterns of Prescription Drug Abuse 349

Major OTC Analgesic Drugs 349

Aspirin 350

Acetaminophen 351

Ibuprofen 351

Naproxen 352

OTC Analgesic Drugs and Attempted Suicide 352

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 14.2: Understanding OTC Analgesic Drugs 352

Other Major Classes of OTC Drugs 352 Sleep Aids 352

Cough-and-Cold Remedies 353

The Pharmaceutical Industry Today 353

■ Portrait: Ryan Haight and the Ryan Haight Act of 2008 354

Dietary Supplements 355

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: What We Know about Nine Herbal Supplements 356 Summary 357 / Key Terms 358 / Endnotes 358

■ Point/Count E r P oint iv : Should Prescription Drugs Be Advertised to the General Public? 360

Chapter 15

Drugs for treating schizophrenia and Mood Disorders 362

The Biomedical Model 363

By the Numbers . . . 363

Antipsychotic Drugs and Schizophrenia 364

The Symptoms of Schizophrenia 364 The Early Days of Antipsychotic Drug Treatment 364

■ hE a L th Lin E : Mercury Poisoning: On Being Mad As a Hatter 365

Antipsychotic Drug Treatment 365

First-Generation Antipsychotic Drugs 365

Second-Generation Antipsychotic Drugs 366

Third-Generation Antipsychotic Drugs 367 Effects of Antipsychotic Drugs on the Brain 367 Drugs Used to Treat Depression 368

■ Portrait: The Melancholy President— Abraham Lincoln, Depression, and Those “Little Blue Pills” 369

First-Generation Antidepressant Drugs 369

Second-Generation Antidepressant Drugs 370

Third-Generation Antidepressant Drugs 370

■ hE a L th aLE rt: SSRI Antidepressants and Elevated Risk of Suicide among Children and Adolescents 371

Effects of Antidepressant Drugs on the Brain 371 The Effectiveness of Specific Antidepressant Drugs 372 Drugs for Other Types of Mental Disorders 372 Mania and Bipolar Disorder 372

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 15.1: Understanding the Biochemistry of Mental Illness 373 Autism 373

Off-Label Usage of Psychotropic Medications 374 Psychiatric Drugs, Social Policy, and Deinstitutionalization 374

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Psychiatric Drugs and the Civil Liberties Debate 375 Summary 375 / Key Terms 376 / Endnotes 376

Part s ix Prevention and treatment 379 Chapter 16

By the Numbers . . . 380 Levels of Intervention in Substance-Abuse Prevention 380

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 16.1: Understanding Levels of Intervention in SubstanceAbuse Prevention Programs 381 Strategies for Substance-Abuse Prevention 381 Resilience and Primary Prevention Efforts 382

Measuring Success in a Substance-Abuse Prevention Program 382

A Matter of Public Health 382

■ hE a L th Lin E : The Public Health Model and the Analogy of Infectious Disease Control 383

■ Portrait: Dr. A. Thomas McLellan Goes to Washington (Briefly) 384

Lessons from the Past: Prevention Approaches That Have Failed 384

Reducing the Availability of Drugs 384

Punitive Measures 385

Scare Tactics and Negative Education 385

Objective Information Approaches 386

Magic Bullets and Promotional Campaigns 386

Self-Esteem Enhancement and Affective Education 386

Hope and Promise: Components of Effective School-Based Prevention Programs 387

Peer-Refusal Skills 387

Anxiety and Stress Reduction 387

Social Skills and Personal Decision Making 387

An Example of an Effective School-Based Prevention Program 387

■ hE a L th Lin E : Peer-Refusal Skills: Ten Ways to Make It Easier to Say No 388

Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) 389

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 16.2:

Understanding Primary Prevention and Education 389

Community-Based Prevention Programs 390

Components of an Effective Community-Based Program 390

Alternative-Behavior Programming 391

The Influence of Media 391

An Example of an Effective Community-Based Prevention Program 391

Family Systems in Primary and Secondary Prevention 392

Special Role Models in Substance-Abuse Prevention 392

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Substance Use and Abuse among Young Mothers 393

Parental Communication in Substance-Abuse Prevention 393

The Triple Threat: Stress, Boredom, and Spending Money 394

Multicultural Issues in Primary and Secondary Prevention 394

Prevention Approaches in Latino Communities 394

Prevention Approaches in African American Communities 395

Substance-Abuse Prevention in the Workplace 395

The Economic Costs of Substance Abuse in the Workplace 396

Drug Testing in the Workplace 396

The Impact of Drug-Free Workplace Policies 397

Yes, You: Substance-Abuse Prevention and the College Student 397

Changing the Culture of Alcohol and Other Drug Use in College 398

Substance-Abuse Prevention on College Campuses 398

■ hE a L th Lin E : Alcohol 101 on College Campuses 399

Substance-Abuse Prevention Information 399

Summary 400 / Key Terms 401 / Endnotes 401

■ Point/Count E r P oint v : Should We Continue to D.A.R.E. or Should We Give it up? 405

Chapter 17

substance-abuse treatment: strategies for Change 407

By the Numbers . . . 408

Designing Effective Substance-Abuse Treatment Programs 409

The Biopsychosocial Model for Substance-Abuse Treatment 409

Intervention through Incarceration and Other Punitive Measures 409

Substance-Abuse Treatment and Law Enforcement 410

■ d rugs . . in f o C us: Penalties for Crack versus Penalties for Powder Cocaine: Correcting an Injustice 413

Prison-Alternative Treatment Programs 414 Drug Courts 414

■ Portrait: Monsignor William O’Brien— Founder of Daytop Village 415

Prison-Based Treatment Programs 416

Substance-Abuse Treatment in the Workplace 416

The Personal Journey to Treatment and Recovery 417 Rehabilitation and the Stages of Change 417

Stages of Change and Other Problems in Life 418

■ Qui C k Con CEP t Ch EC k 17.1: Understanding the Stages of Change in SubstanceAbuse Treatment 419

The Impact of Family Systems on Treatment and Recovery 419

Family Dynamics in Drug Abuse 419

Enabling Behaviors as Obstacles to Rehabilitation 420

Survival Roles and Coping Mechanisms 421 Resistance at the Beginning, Support along the Way 421

Finding the Right Substance-Abuse Treatment Program 421

Judging the Quality of the Treatment Facility 422

Principles to Maximize the Chances of Successful Treatment 423

Needing versus Receiving Substance-Abuse Treatment 423

A Final Note: For Those Who Need Help . . . 424

Summary 425 / Key Terms 426 / Endnotes 426

Credits 429 index 433

This page intentionally left blank

In today’s world, drugs and their use have the potential for good and for bad. As a society and as individuals, we can be the beneficiaries of drugs—or their victims. This perspective continues to be the message of Drugs, Behavior, and Modern Society, Eighth Edition. As has been the case since the first edition, this book introduces the basic facts and major issues concerning drug-taking behavior in a straightforward, comprehensive, and reader-friendly manner. A background in biology, sociology, psychology, or chemistry is not necessary. The only requirement is a sense of curiosity about the range of chemical substances that affect our minds and our bodies and an interest in the challenges these substances bring to our society and our daily lives. These challenges can be framed in terms of three fundamental themes.

The role of drug-taking behavior throughout history

First of all, present-day issues concerning drug misuse and abuse are issues that society has confronted for a long time. Drugs and drug-taking behavior are consequences of a particularly human need to feel stronger, more alert, calmer, more distant and dissociated from our surroundings, or simply good. It is the misuse and abuse of chemical substances to achieve these ends that have resulted in major problems in the United States and around the world.

The diversity in psychoactive drugs in our society

There is an enormous diversity among drugs that affect the mind and the body. We need to educate ourselves not only about illicit drugs such as cocaine, amphetamines, heroin, hallucinogens, and marijuana but also about legally available drugs such as alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine. Drugs, Behavior, and Modern Society has been designed as a comprehensive survey of all types of psychoactive drugs, addressing the issues of drug-taking behavior from a combination of psychological, biological, and sociological perspectives. The personal impact of drug-related issues in our lives Finally, we need to recognize that, like it or not, the decision to use drugs is one of life’s choices in contemporary society, regardless of our racial, ethnic, or religious background, how much money we have, where we live, how much education we have acquired, whether we are male or female, and whether we are young or old. The potential for misuse and abuse is a problem facing all of us.

new to this edition

The Eighth Edition of Drugs, Behavior, and Modern Society is divided into six sections:

Part One (Chapters 1–3): Drugs in Society/Drugs in Our Lives

Part Two (Chapters 4–7): Legally Restricted Drugs in Our Society

Part Three (Chapters 8–11): Legal Drugs in Our Society

Part Four (Chapters 12 and 13): Enhancers and Depressants

Part Five (Chapters 14 and 15): Medicinal Drugs

Part Six (Chapters 16 and 17): Prevention and Treatment

As you will see, chapters about particular drugs have been grouped not in terms of their pharmacological or chemical characteristics but, rather, in terms of how readily accessible they are to the general public and today’s societal attitudes toward their use. The last section of the book concerns itself with prevention and treatment. In addition, several special features throughout the book will enhance your experience as a reader and serve as learning aids.

This text is available in a variety of formats—digital and print. To learn more about our programs, pricing options, and customization, visit www.pearsonhighered .com

By the numbers . . .

At the beginning of each chapter, a feature called By the Numbers . . . provides an often surprising and provocative insight into current viewpoints and research. It is presented in a brief, quantitative format that draws you into the chapter and sets the stage for further exploration.

Quick Concept Checks

Sometimes, when the material gets complicated, it is good to have a quick way of finding out whether you understand the basic concepts being explained. Each chapter of this book includes, from time to time, a Quick Concept Check, where you can see in a minute

or two where you stand. Some of the Checks are in a matching format; others involve interpreting a graph or diagram. In some cases, you will be asked to apply the principles you have learned to a real-world situation.

portraits

Seventeen Portrait features, one in each chapter, take you into the lives of individuals who either have influenced our thinking about drugs in our society or have been affected by drug use or abuse. Some of these people are known to the public at large, but many are not. The subjects of these Portraits include a brutal drug trafficker (Pablo Escobar, Chapter 2), a movie star (Robert Downey Jr., Chapter 4), a convicted killer (David Laffer, Chapter 5), a cultural icon (Timothy Leary, Chapter 6), and a depressive U.S. President (Abraham Lincoln, Chapter 13). All the Portraits put a human face on discussions of drugs and behavior. They remind us that we are dealing with issues that affect real people in all walks of life, now and in the past.

Drugs . . . in Focus

There are many fascinating stories to tell about the role of drugs in our history and our present-day culture, along with important facts and serious issues surrounding drug use. A total of 26 Drugs . . . in Focus features are presented in the Eighth Edition. The topics of these features cover a wide range, from questions about the origins of the word coca in Coca-Cola (Chapter 4) and possible hallucinogenic witchcraft in seventeenth century Salem, Massachusetts, (Chapter 6), to future possibilities of gene doping in the Olympics (Chapter 12) and the present-day use of “truth serum” in terrorist interrogations (Chapter 13).

health line

Helpful information regarding the effectiveness and safety aspects of particular drugs, specific aspects of drug-taking behavior, and new medical applications can be found in 22 Health Line features throughout the book. Health Line topics include understanding the neurological basis for drug craving (Chapter 3), the controversy over the use of stimulant medications as “smart pills” (Chapter 4), concerns over a new synthetic marijuana called Spice (Chapter 7), the risks of smoking mentholated cigarettes among African Americans (Chapter 10), “doctor-shopping” and prescription pain medications (Chapter 14), and alcohol prevention programs like Alcohol 101 on college campuses (Chapter 16), to name a few.

health alert

Information of a more urgent nature is provided in 14 Health Alert features. You will find important facts that you can use to recognize the signs of drug misuse or abuse and ways in which you can respond to emergency drug-taking situations, as well as useful Internet links where you can go for assistance. Health Alert topics in the Eighth Edition include strategies to avoid adverse effects of drug-drug and food-drug combinations (Chapter 3), the risks of cocaine combined with alcohol (Chapter 4), emergency guidelines for adverse reactions to LSD (Chapter 6) or alcohol (Chap ter 8), and the dangers of Rohypnol as a date-rape drug (Chapter 13).

point/Counterpoint Debates

Drug issues are seldom black or white, right or wrong. Some of the most hotly debated questions of our day concern the use, misuse, and abuse of drugs. These issues deserve a good deal of critical thought. This is why at specific locations in this book, I have taken five important controversies concerning drugs, collected the key viewpoints pro and con, and created a Point/ Counterpoint debate based on a simulated conversation that two hypothetical people might have on that question. The Point/Counterpoint features appear at the end of the chapter that deal specifically with the controversy addressed in the debate. I invite you to read these debates carefully and try to arrive at your own position, as an exercise in critical thinking. Along with considering the critical thinking questions for further discussion that follow each Point/Counterpoint feature, you may wish to continue the debate in your class.

supplements

Pearson Education is pleased to offer the following supplements to qualified adopters.

instructor’s Manual and test Bank

(0-205-04839-0)

This Instructor’s Manual and Test Bank provides instructors with support material, classroom enrichment information, and wealth of assessment questions. Corresponding to the chapters in the text, each of the manual’s 17 chapters contains discussion questions, lecture outlines, video suggestions, and a test bank, which

includes an extensive set of multiple choice, true/false and essay questions.

Mytest test Bank (0-205-04837-4)

This test bank is available in computerized format, which allows instructors to easily create and print quizzes and exams. Questions and tests can be authored online, allowing instructors ultimate flexibility and the ability to efficiently manage assessments anytime, anywhere. Instructors can easily access existing questions, edit, create, and store using simple drag and drop Word-like controls. For more information, go to www.PearsonMyTest.com.

powerpoint presentation (0-205-04836-6)

The PowerPoint Presentation is an exciting interactive tool for use in the classroom. Each chapter pairs key concepts with images from the textbook to reinforce student learning.

Mypsychlab (www.mypsychlab.com)

This online study resource offers a wealth of animations and practice tests, plus additional study and research tools. With this edition, there are now new assessments, web and video/media links, and flash cards. www.pearsonhighered.com

an invitation to readers

I welcome your reactions to Drugs, Behavior, and Modern Society, Eighth Edition. Please send any comments or questions to the following address: Dr. Charles F. Levinthal, Department of Psychology, 135 Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY 11549. You can also communicate by fax at 516 463-6052 or at the following email address: charles.f.levinthal@hofstra.edu. I look forward to hearing from you.

acknowledgments

In the course of writing the Eighth Edition, I have received much encouragement, assistance, and expert advice from a number of people. I have benefited from their generous

sharing of materials, knowledge, and insights. I am particularly indebted to Dr. Elizabeth Crane, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Charles F. Miller, Office of Policy and Interagency Affairs, National Drug Intelligence Center, U.S. Department of Justice; Dr. Patrick M. O’Malley, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and Lawrence Payne, Office of Public Affairs, Drug Enforcement Administration, U.S. Department of Justice.

I am fortunate to have worked with a superb team at Pearson. I am especially indebted to my editor, Susan Hartman, my program manager, Reena Dalal, and my senior project manager, Revathi Viswanathan. Their professionalism and talents contributed so much to the production quality of this book and are greatly appreciated. A number of manuscript reviewers made invaluable suggestions as I worked on the Eighth Edition. I thank all of them for their help: Marge MurrayDavis, Minnesota State University; Philip Langlais, Old Dominion University; Robin Joynes, Kent State University; Chris Jones-Cage, College of the Desert; Susan Fellows, California State University, Dominguez Hills; Toni Watt, Texas State University; Larry Ashley, University of Nevada; Frank White, University of North Dakota; Jennifer Graham, Penn State University; Christopher Goode, Georgia State University; Andy Harcrow, The University of Alabama; Robert Carr, University of South Dakota; John Gampher, University of Alabama at Birmingham; Bengie Cravey, Darton State College; Lee Ancona, University of North Texas; Sidney Auerbach, Rutgers University; Christopher Correia, Auburn University; Perry Fuchs, UT Arlington; Edith Ellis, College of Charleston; Neil Rowland, University of Florida; William Cabin, Richard Stockton College.

On a more personal note, there are others who have given me their support over the years and to whom my appreciation goes beyond words. As always, I thank my mother-in-law, Selma Kuby, for her encouragement and love.

Above all, my family has been a continuing source of strength. I will always be grateful to my sons David and Brian, and to my daughters-in-law Sarah and Karen, for their love and understanding. I am especially grateful to my wife, Beth, for her abiding love, support, and complete faith in my abilities. The Eighth Edition is dedicated to my grandsons, Aaron Matthew Levinthal and Michael Samuel Levinthal.

Charles F. Levinthal

This page intentionally left blank

Drugs . . . in Focus

Drug Abuse and the College Student: An Assessment Tool

In a research study conducted at Rutgers University, a cutoff score of five or more “yes” responses to the following twentyfive questions in the Rutgers Collegiate Substance Abuse Screening Test (RCSAST) was found effective in correctly classifying 94 percent of young adults in a clinical sample as problem users and 89 percent of control individuals as nonproblem users. It is important, however, to remember that the RCSAST does not by itself determine the presence of substance abuse or dependence (see Chapter 2). The RCSAST is designed to be used as one part of a larger assessment battery aimed at identifying which young adults experience problems due to substance use and specifically what types of problems a particular individual is experiencing. Here are the questions:

1. Have you gotten into financial trouble as a result of drinking or other drug use?

2. Is alcohol or other drug use making your college life unhappy?

3. Do you use alcohol or other drugs because you are shy with other people?

4. Has drinking alcohol or using other drugs ever caused conflicts with close friends of the opposite sex?

5. Has drinking alcohol or using other drugs ever caused conflicts with close friends of the same sex?

6. Has drinking alcohol or using other drugs ever damaged other friendships?

7. Has drinking alcohol or using other drugs ever been behind your losing a job (or the direct reason for it)?

8. Do you lose time from school due to drinking and/or other drug use?

9. Has drinking alcohol or using other drugs ever interfered with your preparations for exams?

10. Has your efficiency decreased since drinking and/or using other drugs?

11. Do you drink alcohol or use other drugs to escape from worries or troubles?

12. Is your drinking and/or using other drugs jeopardizing your academic performance?

13. Do you drink or use other drugs to build up your self-confidence?

14. Has your ambition decreased since drinking and/or drug using?

15. Does drinking or using other drugs cause you to have difficulty sleeping?

16. Have you ever felt remorse after drinking and/or using other drugs?

17. Do you drink or use drugs alone?

18. Do you crave a drink or other drug at a definite time daily?

19. Do you want a drink or other drug the next morning?

20. Have you ever had a complete or partial loss of memory as a result of drinking or using other drugs?

21. Is drinking or using other drugs affecting your reputation?

22. Does your drinking and/or using other drugs make you careless of your family’s welfare?

23. Do you seek out drinking/drugging companions and drinking/drugging environments?

24. Has your physician ever treated you for drinking and/ or other drug use?

25. Have you ever been to a hospital or institution on account of drinking or other drug use?

Source: Bennett, M. E.; McCrady, B. S.; Frankenstein, W.; Laitman, L. A.; Van Horn, D. H. A.; and Keller, D. S. (1993). Identifying young adult substance abusers: The Rutgers Collegiate Substance Abuse Screening Test. Journal of Studies in Alcohol, 54, 522–527. Reprinted with permission of the authors of the RCSAST.

large number of separate medications. This population is especially vulnerable to the hazards of drug misuse.

In contrast, drug abuse is typically applied to cases in which a licit or illicit drug is used in ways that produce some form of physical, mental, or social impairment (See Drug in Focus on p. 8). The primary motivation for individuals involved in drug abuse is recreational. Drugs with abuse potential include not only the common street drugs but also legally available psychoactive substances, such as caffeine and nicotine (stimulants), alcohol and inhaled solvents (depressants), and a number of prescription or OTC medications designated for medical purposes but used by some individuals exclusively on a recreational basis. In Chapter 5, we will examine concerns about the abuse of opioid pain medications such as Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet, among others. In these particular cases, the distinction between drug misuse and drug abuse is particularly blurry. When there is no intent to make a value judgment about the motivation or consequences of a particular type of drug-taking behavior, we will refer to the behavior simply as drug use.

Before examining the major role that drugs and drug-taking behavior play in our lives today, however, it is important to examine the historical foundations of drug use. We need to understand why drug-taking behavior has been so pervasive over the many centuries of human history, and why drug-taking behavior remains so compelling for us in our contemporary society. We also need to understand the ways in which our society has responded to problems associated with drug use. How have our attitudes toward drugs changed over time? How did people feel about drugs and drug-taking behavior one hundred years ago, fifty years ago, twenty years ago, or even ten years ago? These are questions that we will now address.

Drugs in Early Times

Try to imagine the accidental circumstances under which a psychoactive drug might have been discovered. Thousands of years ago, perhaps a hundred thousand years ago, the process of discovery would have been as natural as eating, and the motivation as basic as simple curiosity. In cool climates, next to a cave dwelling may have grown a profusion of blue morning glories or brightly colored mushrooms, plants that produce hallucinogens similar to LSD. In desert regions, yelloworange fruits grew on certain cacti, the source of the hallucinogenic drug peyote. Elsewhere, poppy plants, the source of opium, covered acres of open fields. Coca leaves, from which cocaine is made, grew on shrubs along the mountain valleys throughout Central and

In a wide range of world cultures throughout history, hallucinogens have been regarded as having deeply spiritual powers. Under the influence of drugs, this modern-day shaman communicates with the spirit world.

South America. The hardy cannabis plant, the source of marijuana, grew practically everywhere.

Some of this curiosity may have been sparked by observing the unusual behavior of animals as they fed on these plants. Within their own experience, people made the connection, somewhere along the line, between the chewing of willow bark (the source of modern-day aspirin) and the relief of a headache or between the eating of the senna plant (a natural laxative) and the relief of constipation.9

Of course, some of these plants made people sick, and many of them were poisonous and caused death. However, it is likely that the plants that had the strangest impact on humans were the ones that produced hallucinations. Having a sudden vision of something totally alien to everyday life must have been overwhelming, like a visit to another world. Individuals with prior knowledge about such plants, as well as about plants with therapeutic powers, would eventually acquire great power over others in the community.

The accumulation of knowledge about consciousness-altering substances would mark the beginning of shamanism, a practice among primitive societies, dating back by some estimates more than forty thousand

shamanism: The philosophy and practice of healing in which diagnosis or treatment is based on trancelike states, on the part of either the healer (shaman) or the patient.

years, in which an individual called a shaman acts as a healer through a combination of trances and plantbased medicines, usually in the context of a local religious rite. Shamans still function today in remote areas of the world, often alongside practitioners of modern medicine. As we will see in Chapter 6, hallucinationproducing plants of various kinds play a major role in present-day shamanic healing.

With the development of centralized religions in Egyptian and Babylonian societies, the influence of shamanism gradually declined. The power to heal through one’s knowledge of drugs passed into the hands of the priesthood, which placed greater emphasis on formal rituals and rules than on hallucinations and trances.

The most dramatic testament to the development of priestly healing during this period is a 65-foot-long Egyptian scroll known as the Ebers Papyrus , named after a British Egyptologist who acquired it in 1872. This mammoth document, dating from 1500 b.c ., contains more than eight hundred prescriptions for practically every ailment imaginable, including simple wasp stings and crocodile bites, baldness, constipation, headaches, enlarged prostate glands, sweaty feet, arthritis, inflammations of all types, heart disease, and cancer. More than a hundred of the preparations contained castor oil as a natural laxative; some contained “the berry of the poppy,” which we now recognize as the Egyptian reference to opium. Other ingredients were quite bizarre: lizard’s blood, the teeth of swine, the oil of worms, the hoof of an ass, putrid meat with fly specks, and crocodile dung (excrement of all types being highly favored for its ability to frighten off the evil spirits of disease).10

How successful were these strange remedies? It is impossible to know because no records were kept on what happened to the patients. Although some of the ingredients (such as opium and castor oil) had true medicinal value, much of the improvement from these concoctions may have been psychological rather than physiological. In other words, improvements in the patient’s condition resulted from the patient’s belief that he or she would be helped—a phenomenon known as the placebo effect. Psychological factors have played a critical role throughout the history of drugs. The importance of the placebo effect as an explanation of some drug effects will be examined in Chapter 3.

Along with substances that had genuine healing properties, some psychoactive drugs were put to less positive use. In the early Middle Ages, Viking warriors ate the mushroom Amanita muscaria, known as fly agaric, and experienced a tremendous increase in energy, which resulted in wild behavior in battle. They were called Berserkers because of the bear skins they wore, but this is

the origin of the word “berserk” as a reference to reckless and violent behavior. At about the same time, witches operating on the periphery of European society created “witch’s brews,” mixtures made of various plants such as mandrake, henbane, and belladonna, creating strange hallucinations and a sensation of flying. The toads that they included in their recipes didn’t hurt either: We know now that the sweat glands of certain toads contain a chemical related to dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a powerful hallucinogenic drug (see Chapter 6).11

Drugs in the Nineteenth Century

By the end of the nineteenth century, the medical profession had made significant strides with respect to medicinal healing. Morphine was identified as the active ingredient in opium, a drug that had been in use for at least three thousand years and had become the physician’s most reliable prescription for the control of pain due to disease and injury. The invention of the syringe made it possible to deliver the morphine directly and speedily into the bloodstream. Cocaine, having been extracted from coca leaves, was used as a stimulant and antidepressant. Sedative powers to calm the mind or induce sleep had been discovered in bromides and chloral hydrate.

There were also new drugs for specific purposes or particular diseases. Anesthetic drugs were discovered that made surgery painless for the first time in history. Some diseases could actually be prevented through the administration of vaccines, such as the vaccine against smallpox introduced by Edward Jenner in 1796 and the vaccine against rabies introduced by Louis Pasteur in 1885. The discovery of new pharmaceutical products marked the modern era in the history of healing.12

The social picture of drug-taking behavior during this time, however, was more complicated. By the 1890s, prominent leaders in the medical profession and social reformers had begun to call attention to societal problems resulting from the widespread and uncontrolled access to psychoactive drugs. Remedies called

shaman (SHAH-men): A healer whose diagnosis or treatment of patients is based at least in part on trances. These trances are frequently induced by hallucinogenic drugs.

ebers Papyrus: An Egyptian document, dated approximately 1500 b c., containing more than eight hundred prescriptions for common ailments and diseases.

placebo (pla-Cee-bo) effect: Any change in a person’s condition after taking a drug, based solely on that person’s beliefs about the drug rather than on any physical effects of the drug.

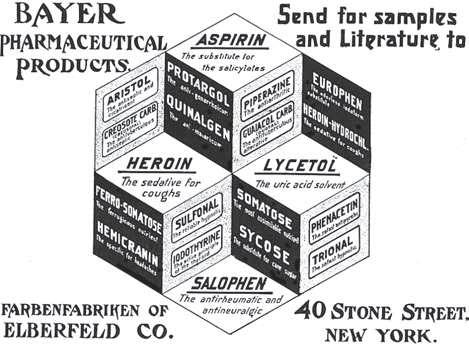

Around 1900, heroin was advertised as a completely safe remedy for common ailments, along with aspirin. No one knows how many people became dependent on heroin as a result.

patent medicines , sold through advertisements, peddlers, or general stores, contained opium, alcohol, and cocaine and were promoted as answers to virtually all common medical and nonmedical complaints.

Opium itself was cheap, easily available, and completely legal. Most people, from newborn infants to the elderly, in the United States and Europe “took opium” during their lives. The way in which they took it, however, was a critical social factor. The respectable way was to drink it, usually in a liquid form called laudanum. By contrast, the smoking of opium, as introduced by Chinese immigrants imported for manual labor in the American West, was considered degrading and immoral. Laws prohibiting opium smoking began to be enacted in 1875. In light of the tolerant attitude toward opium drinking, the strong emotional opposition to opium smoking may be viewed as more anti-Chinese than anti-opium.13

Like opium, cocaine was in widespread use and was taken quite casually in a variety of forms during this period. The original formula for Coca-Cola, as the name suggests, contained cocaine until 1903 (see Chapter 4), as did Dr. Agnew’s Catarrh Powder, a popular remedy for chest colds. In the mid-1880s, Parke, Davis, and Company (since 2002, merged with Pfizer, Inc.) was selling cocaine and its botanical source, coca, in more than a dozen forms, including coca-leaf cigarettes and cigars, cocaine inhalants, a coca cordial, and an injectable cocaine solution.14

A Viennese doctor named Sigmund Freud, who was later to gain a greater reputation for his psychoanalytic theories than for his ideas concerning psychoactive drugs, promoted cocaine as a “magical drug.” In an influential paper published in 1884, Freud recommended cocaine as a safe and effective treatment for morphine addiction. When a friend and colleague became heavily

addicted to cocaine, Freud quickly reversed his position, regretting for the rest of his life that he had been initially so enthusiastic in recommending its use (see Chapter 4).15

Drugs and Behavior in the Twentieth Century

By 1900, the promise of medical advances in the area of drugs was beginning to be matched by concern about the dependence that some of these drugs could produce. For a short while after its introduction in 1898, heroin (a derivative of morphine) was completely legal and considered safe. Physicians were impressed with its effectiveness in the treatment of coughs, chest pains, and the respiratory difficulties associated with pneumonia and tuberculosis. This was an era in which antibiotic drugs were unavailable, and pneumonia and tuberculosis were among the leading causes of death.16

Some physicians even recommended heroin as a treatment for morphine addiction. Its powerful addictive properties, however, soon became evident. The enactment of laws restricting access to heroin and certain other psychoactive drugs, including marijuana, would eventually follow in later years, a topic discussed further in Chapter 2.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, neither the general public nor the government considered alcohol a drug. Nonetheless, the American temperance movement dedicated to the prohibition of alcohol consumption, led by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League, was a formidable political force. In 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution took effect, ushering in the era of national Prohibition, which lasted for thirteen years.

Although successful in substantially reducing the rates of alcohol consumption in the United States, as well as the number of deaths from alcohol-related diseases, Prohibition also succeeded in establishing a nationwide alcohol distribution network dominated by sophisticated criminal organizations. 17 Violent gang wars arose in major American cities as one group battled another for control of the liquor trade.

By the early 1930s, whatever desirable healthrelated effects Prohibition may have brought were perceived to be overshadowed by the undesirable social changes that had come along with it. Since its end in 1933, the social problems associated with the era

patent medicine: Historically, a drug or combination of drugs sold through peddlers, shops, or mail-order advertisements.

of Prohibition have often been cited as an argument against the continuing restriction of psychoactive drugs in general.

Drugs and Behavior from 1945 to 1960

In the years following World War II, for the first time, physicians were able to control bacteria-borne infectious diseases through the administration of antibiotic drugs. Although penicillin had been discovered in a particular species of mold by Alexander Fleming in 1928, techniques for extracting large amounts from the mold were not perfected until the 1940s. Also during that time, Selman Waksman found that a species of fungus had powerful antibacterial effects; it was later to be the source of the drug streptomycin.

In the field of psychiatry, advances in therapeutic drugs did not occur until the early 1950s, when quite accidentally a group of psychoactive drugs were discovered that relieved schizophrenic symptoms without producing heavy sedation. The first of these, chlorpromazine (brand name: Thorazine), reduced the hallucinations, agitation, and disordered thinking common to schizophrenia. Soon after, there was a torrent of new drugs, forming the basis not only for the treatment of schizophrenia but also the

chlorpromazine (chlor-PrO-mah-zeen): An antipsychotic (antischizophrenia) drug. Brand name is Thorazine (THOR-a-zeen).

treatment of mental illness in general. It was a revolution in psychiatric care, equivalent to the impact of antibiotics in medical care a decade earlier.

In the recreational drug scene of post–World War II America, a number of features stand out. Smoking was considered romantic and sexy, and smoking was commonplace. In 1955, regular cigarette smoking involved more than half of all male adults and more than one-quarter of all female adults in the United States. It was the era of the two-martini lunch; social drinking was at the height of its popularity and acceptance. Cocktail parties dominated the social scene. There was little or no public awareness that alcohol or tobacco use constituted drug-taking behavior. In contrast, the general perception of certain drugs such as heroin, marijuana, and cocaine was simple and negative: They were considered bad, they were illegal, and “no one you knew” had anything to do with them. Illicit drugs were seen as the province of criminals, the urban poor, and nonwhites.18 The point is that an entire class of drugs were, during this period, outside the mainstream of American life. Furthermore, an atmosphere of fear and suspicion surrounded people who took such drugs. Nonetheless, for the vast majority of Americans, drugs were not considered an issue in their lives.

Drugs and Behavior after 1960

During the 1960s, basic premises of American life—the beliefs that working hard and living a good life would

The famous Woodstock Festival concert drew an estimated 500,000 people to a farm in upstate New York in the summer of 1969. According to historian David Musto, the peacefulness of such a gigantic gathering is considered to have been due, at least in part, to the widespread use of marijuana, as opposed to alcohol.