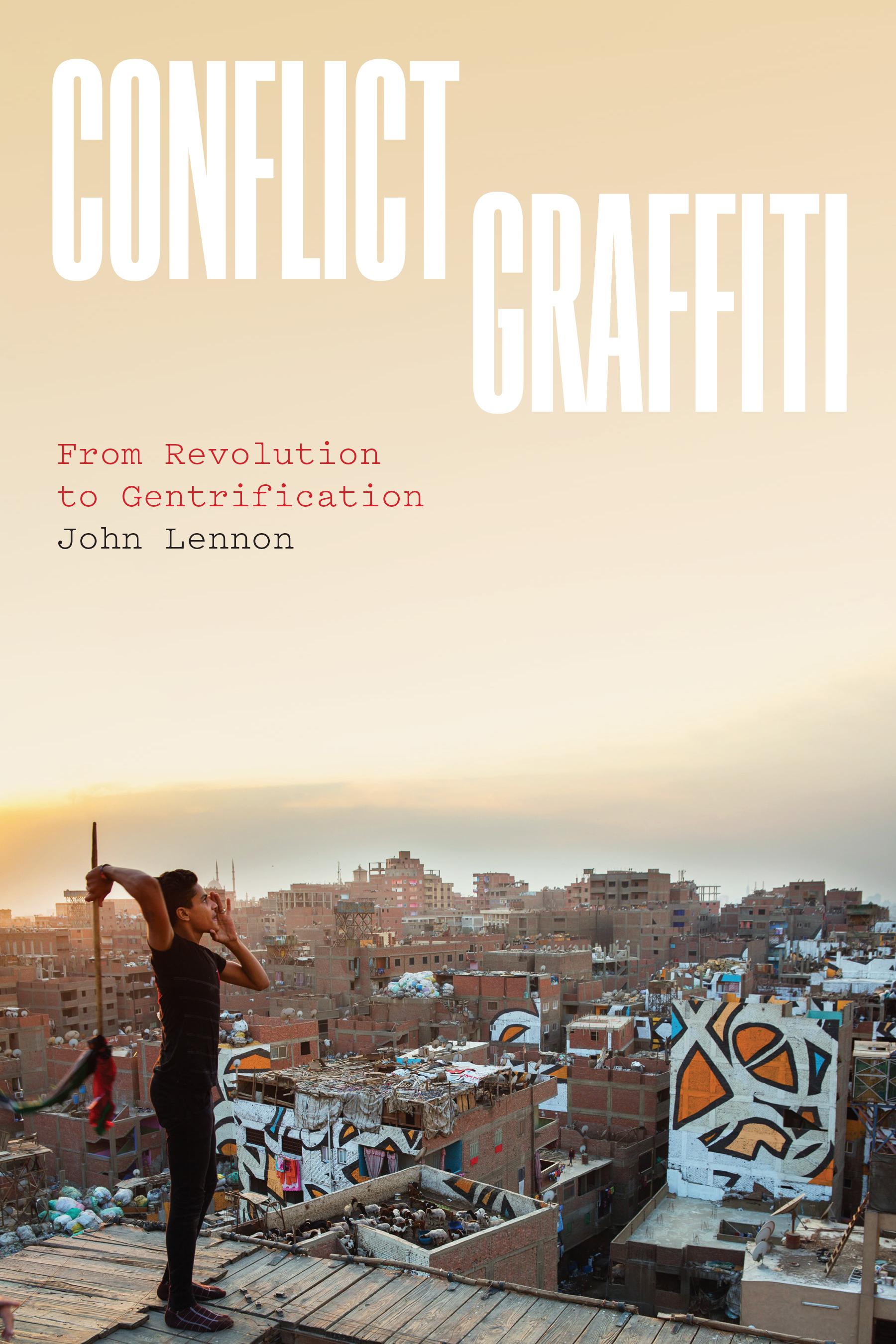

an intro DUC tion to C onfli C t G raffiti

In an episode from the fifth season of the popular Showtime series Homeland, a Hezbollah commander is escorting Central Intelligence Agency officer Carrie Mathison (Claire Danes) through a Syrian refugee camp in Lebanon. With a khimar covering her head (although her blonde hair is still showing), Mathison stares straight ahead as the commander, grabbing a machine gun from another fighter, walks in front of her through a narrow, debris-strewn alley. The camera’s lens tightly focuses on the Hezbollah commander and the CIA agent. Arabic graffiti—يرصنع نطول appears for a split second on the alley’s wall as the two pass by.

Almost immediately after the scene from this episode aired in the United States on October 11, 2015, Arabic speakers watching the show understood Homeland had been tricked. Translated into English, the alley’s graffiti reads, “Homeland is racist.” 1 Heba Amin, Carmen Kapp, and Don Karl later revealed they were the street artists who had “bombed” the show, describing their “hack” on Amin’s website. The three explained that Homeland ’s film crew was searching for “Arabian Street Artists” to “lend authenticity” to the sets of the series that the Washington Post has called “the most bigoted show on television.” 2 After being hired, they were provided with images of graffiti in support of Bashar al-Assad and instructed to spray “nonpolitical” graffiti on the sets’ walls. The Arabic that the show’s crew thought would state sentiments such as “Muhammad is the greatest” was instead a clear political statement decrying the show’s stereotyped descriptions of the Middle East.3

As Homeland ’s designers were busy attempting to replicate a Lebanese Hezbollah stronghold, including by re-creating the minutiae of frayed outdoor plastic curtains on the Berlin-based set, the artists were writing graffiti in Arabic that, when translated to English, read “There is no Homeland”; “Freedom . . . now in 3-D!”; “Homeland is Watermelon”; “Homeland

is a joke and it didn’t make us laugh”; and “#BlackLivesMatter.” Initially, the three artists began their work by spray-painting Arabic proverbs that could be considered subversive only if read in a particular way. But by the second day on the set, they realized no one was paying attention to what they were writing, and they became emboldened to use Western ignorance of Arab culture and language to argue on the set’s walls against Homeland ’s xenophobic representations.4

Much of Homeland ’s story line takes place in the Middle East. It is both racist and lazy that no one on the set could apparently read Arabic.5 The show’s racism and xenophobia are inexcusable; the laziness when it comes to graffiti, though, is easily understood. Homeland ’s designers were attempting to use graffiti to portray a chaotic conflict zone. In this way, they wanted nothing more than what journalists want when reporting from conflict areas around the world as they stand in front of graffitisprayed walls: graffiti is a universal symbol of chaos that signifies a dangerous, lawless area.6 What the graffiti actually states or means is often irrelevant. When it is used simply as a visual backdrop, graffiti are easily accessible symbolic representations of disorder for the viewing audience. What Amin, Kapp, and Karl subversively underscored, though, is precisely the opposite: graffiti are not simplistic, visual, monolithic entities. Instead, these painted words and images rudely interject themselves into the world’s contemporary conflicts. From military outposts to urban storefronts, graffiti appear on streets, walls, lampposts, windows, cars, statues, and countless other objects. Sometimes graffiti demand the overthrow of a government in a war-torn city; other times graffiti are pleas for help in a poverty-stricken area facing the aftermath of an environmental and political catastrophe. Sometimes the words on the wall are radical, arguing for a progressive political agenda in terms of racial and class liberation; other times, they are pro-regime accolades advocating the killing of protesters. Sometimes graffiti are disarmingly idealistic; other times they are jokes, occasionally silly, often darkly humorous.

In short, graffiti are messy politics.

To push graffiti into the background tells only part of the story of an area in conflict. As illustrated by the Homeland example, often that story rests on generic, stock characters and prewritten scripts, representing a conflict in well-trodden narratives. Bringing graffiti to the forefront, however, better contextualizes a conflict’s evolving nature. Graffiti is part of the architecture of the conflict itself—ephemeral artifacts allowing insight into how protest movements react to their built environments. Each graffito on each wall in each city speaks to a particular conflict. To understand individual utterances is to contextualize the roots of that city’s conflict. But placing these utterances in dialogue with one another and fol-

lowing how these images are distributed and remixed illustrates the ways graffiti’s routes address a conflict’s evolution.

For example, on February 11, 2011, a widely shared photograph of Tahrir Square captured the moment when Egypt’s vice president Omar Suleiman announced on television that President Hosni Mubarak had abdicated his office. In the freeze-frame of the image, fireworks adorn the sky while a mass of bodies—individuals are unrecognizable—react to Mubarak’s ouster, something that many had deemed impossible just a few months prior. Visually, the panoramic photo taken from a distance looks not like a photo at all but like an abstract painting, dripping with random dots that haphazardly seep together within the frame. Each dot, though, is a person who had headed to the square in anger, love, or pain.

If we could zoom in on that photo, we would see a kaleidoscope of images and words collectively arguing for Mubarak’s overthrow on the walls that surround Tahrir Square. But just as each protester had individual hopes, desires, and agendas, each sprayed message or image speaks to different individual ideological positionings. Next to the crescent cross was a quickly drawn Guy Fawkes mask. Next to a large replica of Che Guevara in his iconic beret was an earnest sprayed sentence praising the Muslim Brotherhood. Graffiti conversed in both Arabic and English with an abundantly clear consensus: we want Mubarak out of office. There are, though, many textures to the various graffiti that represent an assemblage of differing thoughts on the messiness of sociopolitical movements. Far from a dogmatic message, graffiti offers greater insight into political desire. This focus on graffiti as a complicated and evolving material and immaterial process certainly frames it differently than the Homeland set designers, who wanted no nuance but only a generic script. But this focus also frames graffiti differently than the many scholarly accounts examining conflict zones that do not analyze the process, form, and potential meanings of graffiti. Conflict Graffiti retrieves graffiti from this marginalized position, situating it as an important tool within a larger, amorphous constellation of resistances that materialize protest. Whether from Beirut or Cairo or New Orleans, for many of the graffiti writers, artists, and activists I spoke with, writing on walls is a specific tool to reform the state. Some wish for particular material gains, such as the overthrow of a dictator. Others hope for a revolution of spirit, such as a turning away from capitalism and toward anarchism. All of them, though, understand paint on walls as a way to begin to dismantle oppressive physical and psychological conditions. They are also adamant that graffiti is not a singular tool they can use to achieve their goals. No one I interviewed romantically viewed graffiti as having a magical or innate power to topple a regime, make a police force less racist, or force a nation

to question its ideological foundations. What graffiti writers and artists articulated to me was that through physical confrontation, both in clogging the streets with their bodies and in painting the walls with their demands, a radical change in society could occur. The materiality of protest is key to their political lives. They need to be on the streets, pressed up against one another, their arms outstretched, voices loud and disruptive. The graffiti on the walls mirror these protesters in the streets. When writing about graffiti in conflict areas, I focus on how these two materialities interact—spray paint on walls and bodies in streets consistently engage in dialogue within the pages of this book.

To be clear, though, writing on walls and seizing a city’s square are not the same thing. They have different material presences (and associated dangers) and serve different political functions. They are both, though, types of occupation that frequently share the same public sphere. Scholars employ sophisticated analysis to understand the ideological desires of those who occupy the streets; graffiti, if mentioned at all, is habitually undertheorized. When we think about conflicts, the spectacular violence enacted upon people and cities by overpowering forces is rightfully the focus of discussion. But examining graffiti before, during, and after these spasms of violence renews a needed emphasis on the racialized economic politics that led these people into the path of that violence in the first place, thus furthering discussions on the ways overpowering forces are resisted.

When people head to public squares to protest a president, or to the streets in anger over a community member’s death, it is often construed as the spontaneous actions of an undifferentiated mass. This interpretation misrepresents the protest and the protesters. The flames of a demonstration may have been caused by an unplanned spark, but the environmental conditions prepared for the fire’s ignition over an extended period of time. Seemingly spontaneous actions have roots in material conditions. Protesters, shoulder to shoulder, shouting the same slogans and walking together, are uniform in neither their desires nor their actions. Each protester embodies social conditions and inhabits a particular space for reasons that often differ from those of their neighbors. Together they take to the streets as a group, but the differing social and political antagonisms that individual protesters embody are present as well. Graffiti during these moments of conflict are similarly varied, reflecting the intersection of racialized, gendered, and class politics. Study the graffiti and you’ll find an assemblage of competing desires to read and interpret that grant entry into the complicated nature of resistance and its development from before a conflict begins to after it has ended. Similar to the graffiti writers and activists I interviewed, I do not have

an idealized view of graffiti. Obviously, graffiti alone will not bring forth a regime change, and not all sprayed marks are revolutionary. Nor are all graffiti done by protesters. As individuals use graffiti to mark their dissent, those in power, and their supporters, also react with graffiti of their own. Invading armies use graffiti to confuse local fighters, police use spray paint to surreptitiously mark houses, and advertisers coopt graffiti-style lettering to sell commodities to demonstrators. Protest movements are unstable, fluctuating as a result of internal and external pressures. Graffiti, too, react to unstable environmental conditions. Graffiti are present during revolutionary moments, but graffiti also responds within an environment that is transforming from violent conflict to an uneasy, postconflict state. As cities rebound from political, environmental, and social conflicts, real estate developers are quick to create a buzz around certain neighborhoods by using graffiti to showcase the area as open for business. The conflict changes; so, too, does the graffiti.

Graffiti’s afterlife is also unstable. When people come up to a wall, spray can in hand, they are writing in a public space. As the paint dries, others begin to interact with the writing in myriad ways. Authorities often declare “wars” on graffiti, intending to eradicate it with zero-tolerance policies. In the 1980s, New York City subway writers found their “masterpieces” covering the outside of whole train cars immediately erased by the Metropolitan Transit Authority. Sometimes individuals fight over particular walls or neighborhoods: different writing crews have “battles” in which they write over each other’s tags for bragging rights or dominance, as Susan Phillips discusses in the context of gangs in Wallbangin’ and as Stefano Bloch writes of graffiti crews in his book Going All City.7 Sometimes people take photos of graffiti, remixing them for their own political and financial gain in a way that is quite different from the author’s original intent. For example, after Amin, Kapp, and Stone gained international attention for their hack on the Homeland set, the US-German artist David Krippendorff sold silkscreen replica images of the graffiti during an art fair. When Amin and others pushed back, Krippendorff argued: “We live in an age of sampling and appropriation . . . I was not ‘stealing’ anybody’s narrative. Homeland is a product of the US entertainment industry, and my homage to a hack at its expense also becomes my narrative.” It is, of course, highly questionable that Krippendorff’s self- described “narrative” involves making money off the sale of replicas of political graffiti designed to call attention to racism against Arabs.8 But Krippendorff’s “homage” is just one more example highlighting the way that graffiti, once placed in the public sphere, is always susceptible to reinterpretation. Spray paint is messy, with paint drips landing in unexpected ways on walls and streets. Graffiti’s afterlife is no less messy.

For these reasons, I employ an inclusive framework for both terms graffiti and conflict. Politicians, scholars, and practitioners have consistently debated definitions of the term graffiti. Although these definitions have filled countless newspaper op- eds and pages in scholarly journals, I am not concerned with forming intellectual moats around the term, privileging some wall writing and drawing over others.9 I explore graffiti in terms of place, reception, and distribution. Graffiti is expansive in its application and meanings, and I liberally use the term in this same spirit of capaciousness.

I also use the term conflict to capture a wide range of sociopolitical situations detailed in this book. In his many scholarly analyses of global conflicts, John Burton defines conflicts as deep-rooted problems without discernable solutions involving seemingly recalcitrant, nonnegotiable issues. These are not “disputes” in which parties may find a solution that meet the interests of both sides in a particular crisis. Conflicts, instead, often have roots with many damaged appendages. In response, nongovernmental organizations arise in conflict areas, working to keep people physically safe while striving for an abatement of violence. The academic subfield of peace and conflict studies has attempted, through an interdisciplinary research and pedagogical approach, to examine conflicts holistically and prevent, de- escalate, and find workable solutions through peaceful means for all parties affected by a conflict.10

My use of the term conflict is influenced by some of the impulses flowing through the many iterations of peace and conflict studies (itself a loose amalgamation of many disciplines and contrary ideological positionings). However, after listening to graffiti writers and activists, I specifically use the term conflict to highlight how violence is intimately involved in the production and reception of graffiti. Many graffiti writers and activists see the use of spray paint as a violent act; it is a tool of resistance used to attack forces that are stronger, more powerful, and equipped with lethal force. In this way, my use of the term is influenced by Marxian conflict theory, which, in simplistic terms, is concerned with how one class solidifies its social and economic power through the exploitation of others. This view of conflict certainly helps frame government responses to protesters in which police are called in (often with military equipment) to quell social uprisings and protect private property. I also use the term conflict to discuss the ways that seemingly “natural” disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina and the damage it caused, emerge from structurally based, racialized class inequalities that formed the conditions for the devastation. To this end, expansively using this term allows for an investigation of other ways that “recovery” is unequal and divided along racial and class demarcations. Specifically, in my chapters on New

Orleans and Detroit, I examine the ways street-art campaigns are used to “beautify” previously economically underinvested neighborhoods. In this case, the violence of spray paint works against the inhabitants of the neighborhood as a tool to drive up real estate values, bringing in wealthy, often white investors who push out poorer, often Black and Brown inhabitants. The term conflict, therefore, reflects the inherent violence central to all the examples I explore in this book.

Graffiti, as I define it, escapes neat categorization. The same is true for the term violence. The chapters here describe a spectrum of violence inhabiting the graffiti and its responses in a particular conflict. For example, the Palestinian who spray-paints anti–United States messages on the Separation Wall faces death at the hands of Israeli soldiers. Philippe Bourgois describes this political violence as “directly and purposefully administered in the name of a political ideology, movement or state such as the physical repression of dissent by the army or the police as well as its converse, popular armed struggle against a repressive regime.” 11 This stark violence is easily discernable, and throughout this book I discuss graffiti’s role in overt political violence. The chapters, however, also address the structural violence that is present in the economic and racial disparities of neoliberal capitalism, with its unequal international trade policies, exploitation of labor, cutting of social services, and privatization of infrastructure. This violence is not spectacular, as is the damage done by a soldier’s bullet upon the body of a young graffiti writer spraying antiregime messages on a border wall. Rather, this violence comprises the historically ingrained, often legal policies that lay the foundation for socioeconomic oppression of certain classes, races, and ethnicities. Nancy Scheper-Hughes, in her analysis of violence in the Global South, details how the poor and working class experience this structural violence through the “small wars and invisible genocides” that take place in “peace times,” which radically uncovers the brutalities and their many microforms inflicted by those in power upon the subjugated masses.12

This “everyday violence” takes place far away from the halls of power but emerges in the daily lives of the poor and working class. The discourse surrounding the violence within these communities is muted; when it is discussed, it is often used as evidence of the racial or cultural defects of the marginalized. Far from trivial, this everyday violence can be lethal, and as Pierre Bourdieu showed in his foundational work exploring symbolic violence, it can lead to an internalization of the power structures that keep the poor and working class in their subordinated place, manifesting as an unconscious legitimatization of the (racial, gendered, class) power structures that form a particular society. For Scheper-Hughes, this violence encountered in the individual body finds parallels in the na-

tional body.13 Simply put, violence is structural and marginalized bodies intensely feel its effects.

In his 1906 book Reflections on Violence, George Sorel wrote that “the problems of violence still remains very obscure.” 14 In the more than hundred years since, comprehension of violence—experienced both as a national and as a physical body—is still murky. What is clear, though, is that power is never stable. Even though those in control use physical and symbolic violence to legitimize their place, tides turn, people rebel, and power dynamics change. The oppressed take to the streets to protest with graffiti as one particular tool of many, expressing a counterviolence to those in power.

To introduce the waves of conflict graffiti and how they embody these global moments of violence and counterviolence, I begin with the walls of Ferguson, Missouri, in the aftermath of Michael Brown’s death. The graffiti found on these walls is one example of the various and often contradictory graffiti waves that exist within a particular conflict. After a white police officer killed Michael Brown, a young Black man, graffiti played an active role in contextualizing the ensuing protests while framing police violence as both a national and an international problem. As the protests died down, though, graffiti became a tool to depoliticize the uprising, remaking a movement against racialized police violence into universalist and nonconfrontational messages of peace.

On August 9, 2014, Officer Darren Wilson stopped Michael Brown, who was walking in the middle of the street in Ferguson, Missouri. In conflicting claims, Brown’s hands either were raised to the sky or were used to lunge at the officer; either way, the unarmed eighteen-year-old was shot six times and died in the middle of the day on the same street where he was stopped.15 When news of his suspicious death emerged, the streets of Ferguson erupted in civil unrest. One night after the shooting, a local QuikTrip gas station burned down, twelve stores were vandalized, and numerous people were arrested. A small town twenty miles from St. Louis had suddenly become the focus of international news.16

The unrest lasted for weeks, with the violence livestreamed by protesters and displayed on all the major news channels; the national spotlight shone brightly on this town in Middle America. President Barack Obama made televised pleas for peace and for the protection of Ferguson’s private property as he sympathized with the enraged protesters who saw Brown’s death as an indication of the overall racist practices of a po-

lice state. As Brown’s blood stained the asphalt, thousands of protesters in Ferguson and throughout the country symbolically embodied the young man. Standing sometimes inches from police wearing riot gear, they mirrored Brown’s alleged last position, chanting, “Hands up, don’t shoot!”

For many of these protesters, Brown’s death was a bloody representation of the systematic racism that Black and Brown people face daily. For them, Brown’s death was not a singular case of police brutality but representative of the daily violence enacted upon nonwhite communities. Protesters in Ferguson linked Michael Brown’s death with similar deaths of Black men and women in recent years, reenergizing the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Echoing the US civil rights movements of the 1960s—although with a decentralized leadership employing sophisticated uses of social media—these protests were bodily protests, taking over sidewalks, buildings, streets, and highways. The simple plea “Hands up, don’t shoot!” was chanted from coast to coast in solidarity protests by men and women who worried they could be the next victims. This twinning of an outraged physical presence that shut down streets with viral images spreading across social media was highly effective in forcefully expressing resistance to police brutality in the United States.

As protesters were overtaking the street, graffiti were also overtaking the walls. In Ferguson, graffiti was a dynamic tool in this resistance, inhabiting both a physical and a virtual life. Reading this graffiti helps reframe the inherent chaos, contextualizing and teasing out nuances of reaction to the unrest. In the days after Michael Brown’s death, graffiti offered a variety of overt political messages. Some were simplistic: Brown’s name written in shaky lines. Others were more ornate: Brown’s image surrounded by “RIP” or “Hands up!” Still others specifically referenced the police in questions, commands, or indictments: “Who will protect the public when police break the law?” “Film the police” and “ACAB” (all cops are bastards). Interestingly, some graffiti referenced the demonstrations even as they were happening: a spray-painted image of Edward Crawford Jr., a Black man who threw a tear gas canister in the direction of the police while holding a bag of chips, was sprayed on a wall almost immediately after the photo of him doing so went viral.17

As the above examples indicate, graffiti are not monolithic statements. Just as protesters uttered a wide array of political expressions, so did the graffiti. Spraying blanket statements about the police—“ACAB”—is not the same thing as spraying Brown’s image on a wall. Too often when graffiti is spotted in conflict areas, all messages are categorized under one generic ideological banner of “protest,” which denies the nuances of po-

litical thought of those who are actively engaged. To illustrate this point, the following examples show how Ferguson graffiti specifically frames Michael Brown’s death within a larger history of police violence but in dramatically different ways.

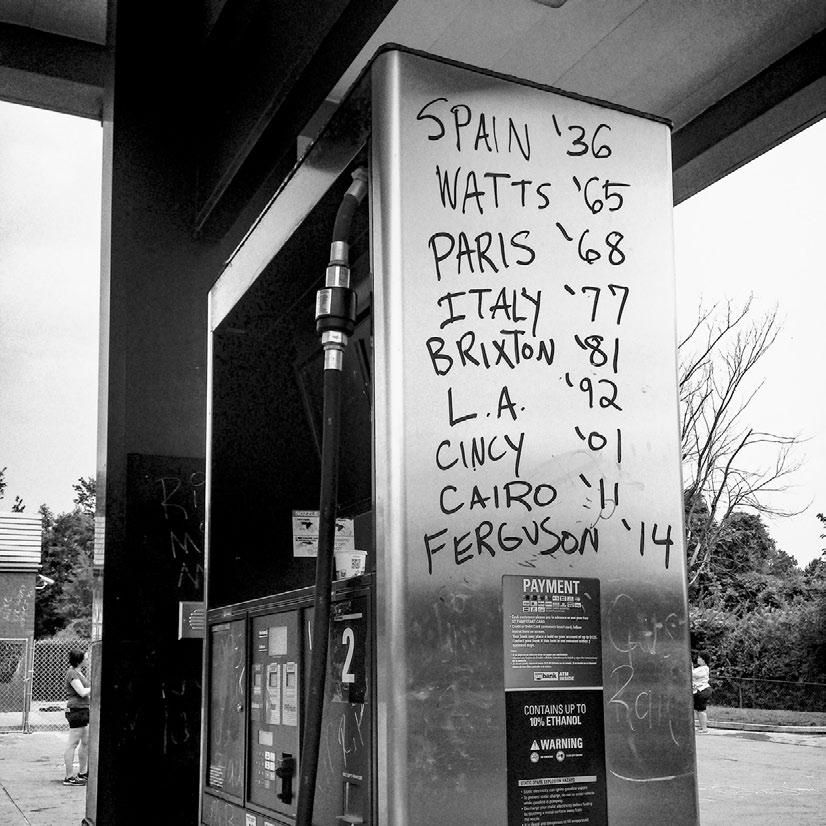

The first graffito is of nine places and dates written in marker on the side of the QuikTrip gas pump destroyed in the protest:

Spain ’36

Watts ’65

Paris ’68

Italy ’77

Brixton ’81

L.A. ’92

Cincy ’01

Cairo ’11

Ferguson ’14

Graffiti on QuikTrip gas pump, Ferguson, Missouri. Photo by Tara Pham.

This graffito rhetorically connects Ferguson protesters with protesters from different continents over the past seventy years. Contextualizing a history of state-imposed violence, this graffito places the Missouri town within a global fight for marginalized people. Importantly, it is not specifically about race or police violence; rather, it internationalizes Brown’s death through instances of localized state violence. This linkage found purchase in other protests throughout the world that used Brown’s death (and the large media presence covering it) to symbolically connect to their own local protest movements. On the wall at Free Derry Corner in Northern Ireland, for example, underneath the famous “You are now entering Free Derry,” someone painted a soldier crouched down and pointing a machine gun at three figures whose hands are raised. Each figure wears a shirt that reads “Derry,” “Palestine,” or “Ferguson.” Connecting all three is the phrase “Hands up, don’t shoot!” 18 In another example, the message “From Ferguson to Palestine—Resistance is not a crime. End racism now!” was sprayed on the Separation Wall dividing Palestine from Israel. A simple heart was painted underneath the words, punctuated with “STLPSC.” Graffiti sutured together these separate geographic areas and complex, varied political situations, awkwardly linking the local, national, and international conversation about Ferguson.

Interestingly, there is no “NYC ’14,” on the Ferguson gas pump and therefore no reference to Eric Garner, another unarmed Black man killed by police a month prior to Brown’s death. Seemingly, the graffiti writer did not want to limit the Ferguson protests to the BLM social movement but, through this omission, expand the scope to other national and international unrests. This graffito on a gas pump—itself an international symbol of the embedded state violence of extraction—refuses to spotlight Ferguson as an isolated incident, instead forcing a broadening of the historical angle. For example, in May 1968 during the Paris student uprisings, a famous graffitied message read “Under the sidewalk, the beach!”—a playful, Dadaist-inspired apothegm ingeniously pointing to other possible worlds hidden within our current one. By referencing these dates, the graffito supplies a short international history lesson to undergird the possibilities still under the protester’s feet as they fought systematic police repression in a Missouri town in 2014.19

The gas pump graffito at the very least suggests that what is happening in the streets of Ferguson also occurred in the streets of Cincinnati or Brixton, but it is also somewhat didactic, requiring knowledge of the historical events that transpired in these places. Importantly, the graffito does not mention the specific racialized injustices revealed in Brown’s death but instead offers, on the side of a gas pump, a compact, global history lesson on the struggle against state violence. Universalizing state

violence links these disparate international civil unrests in interesting ways, but it does so by eliding the specific racial injustices localized in Ferguson.

The second graffito I analyze here is most often cropped out from one of the most viral photographs to emerge from the Ferguson protests. In the photograph, the camera is behind and to the side of a Black man with a backward hat covering his long hair. Wearing a blue shirt and jeans, and a backpack hanging off of one shoulder, his hands are raised as he stares down a very frightening dystopian reality. Men in green fatigues, combat boots, armor vests, knee pads, gas masks, and helmets are pointing automatic weapons directly at him. In the photo’s frame, the lifted boots of the armed men indicate their forward motion. Adding to the visual dissonance is the word police on the shirt of one of the approaching men. This officer is not part of an army in a foreign land; he is a member of a US police force patrolling the streets of a Midwestern town with militarized weaponry.

This photo is of a great many contrasts—the casual attire of the Black man with his hands up against the heavily armored white men in camouflage, weapons drawn. The two sets of participants seemingly do not

Protester facing police with hands up 1, Ferguson, Missouri.

Photo by Scott Olsen/Getty.

exist in the same geographic location: the Black man looks as if he is walking down a city street; the officers look as if they are in the middle of military combat. The shocking dissonance is certainly one of the reasons this image resonated so profoundly. As Angela Davis stated in an interview about Ferguson, “There is an unbroken line of police violence in the United States that takes us all the way back to the days of slavery.” 20 For many, this photo is a visual representation of the violent policing of Black and Brown bodies in the United States.

This iconic photo was reproduced in numerous outlets. If we expand the frame to see the full original photo, however, we can spot graffiti that speaks to the larger political struggle against racialized violence at the hands of the police. Scott Olson, a Getty photographer arrested for not staying in the police- enforced “media pen” during the social unrest, took this photo on Wednesday, August 13, 2014. Olson was heading toward the Michael Brown memorial when he heard an explosion and photographed this encounter while running from the police charge.21 In his photo, a metal fence on one side and a blue US Post Office mailbox on the other side frames the image. On that mailbox is a hastily drawn graffitied message: “Fuck the police.”

Protester facing police with hands up 2, Ferguson, Missouri.

Photo by Scott Olsen/Getty.

This graffito is simultaneously a full-throated threat and a contextualization of the Ferguson protests. In reaction to the 1965 Watts uprisings, Marvin X (Marvin Jackmon) wrote a poem, “Burn, Baby, Burn,” with the line “Mother Fuck the police” to describe police interactions with Blacks within a history of enslavement, and the phrase “fuck the police” has since come to describe violent, racialized policing.22 The phrase draws the divide between the two sides in clear, intentional language. In the 1980s, the phrase became popular and more widespread with the 1988 release of N.W.A.’s album Straight Outta Compton. Ice Cube, who was born four years after the Watts uprisings and cowrote the song “Fuck tha Police” with MC Ren, stated that the song emerged from living a life in an impoverished area where there was an ideological divide between the Black community and the police: “Our people been wanting to say, ‘Fuck the police’ for the longest time. If something happened in my neighborhood, the last people we’d call was the police. Our friends get killed; they never find the killer.” 23 In this interview, Ice Cube argues that the song allowed Black people to invoke the phrase together in public. In fact, at a Detroit concert, the crowd chanted the phrase repeatedly until N.W.A. began to rap—and then were quickly shut down by the police (no charges filed). From N.W.A.’s song to Public Enemy’s “911 Is a Joke” to Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (the film’s main character Radio Raheem is choked to death by a white police officer, which is based on an actual killing of a graffiti writer), Black media revealed the systematic racism of policing in the United States.24 “Fuck the police” does not refer to one particular racist act by the police; it is an overall reaction to the divide between police and the Black community.

If we return to Scott Olson’s photo from Ferguson of a Black man facing a large number of militarized police officers, the graffito “Fuck the police”—hastily drawn on the mailbox sometime before the action in the photo but commenting on the event as it occurred—is both a political statement and a lesson in the urban history of police violence. On the mailbox, the graffito pulled no punches; the intensity of its vulgarity matched that of the violence enacted in the streets. The N.W.A. song describes Los Angeles in the late 1980s, a place Robin D. G. Kelley has described as a “war zone”: “Police helicopters, complex electronic surveillance, even small tanks armed with battering rams became part of the increasingly militarized urban landscape.” 25 The militarization of Los Angeles prefigured that of Ferguson by twenty-five years. So from the mouth of a young Ice Cube in 1988 to a graffito on the side of a Missouri mailbox in 2014, the phrase both historicizes and resists how the state surveils and polices Black bodies using militarized weaponry to “control”

the population, be it the “war on drugs” in California or the specific killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson.26

Importantly, the gas pump and mailbox graffiti rebut contradictory images that were circulating in conservative and mainstream media that categorized the unrest as a selfish riot for material goods, repeatedly showing, for example, a photo of Black men emerging with numerous bottles in their hands through the smashed-in door of a liquor store. The graffiti described above resisted this simplistic narrative, offering an alternative understanding of the uprisings. In the days and weeks after Michael Brown’s death, these types of graffiti materialized throughout Ferguson. When they were erased with swaths of white paint, others emerged in their place.

The copious graffiti made during the Ferguson protests were born of this city and of Brown’s death. The graffiti, though, were linked to previous uprisings. The routes of conflict graffiti are not direct; they often emerge in a collective consciousness. During the Ferguson protests, when men and women took to the streets to confront the police, they walked in the footsteps of earlier civil rights protesters; even if they had never participated in a protest before, their political desire compelled them to join with and follow others. It is the same for graffiti: those who wrote graffiti after Brown’s death might never before have held a spray can in their hands, but their political desire led them to join with and follow others in the swell of protest.

The messiness of political graffiti becomes evident as we examine graffiti’s longer life on Ferguson’s walls and a new graffiti wave becomes apparent. Weeks after Brown’s death, the street protests dwindled in numbers and were contained, controlled, and dispersed by the police. People returned to their daily lives. Most of the overtly antipolice graffiti were erased from the walls. The graffiti, though, did not completely disappear; some of it has been published in Deborah Gambill and Ronald Montgomery’s Let’s Heal STL: Ferguson Messages in Poetry and Paint (2015). Interspersing images and poetry by Gambill and Montgomery, the book illustrates Ferguson’s “restoration” through graffiti. In their introduction, the poets explain that a small advertisement in a local newspaper asked for community member volunteers to join together to write messages and draw pictures on the boarded-up windows of the business district damaged during the unrest. Many came, and, according to the authors, “the language of art and love went far beyond the words, and reached out with symbolism, color, and emotion to herald the local community and world about hope, peace and reconciliation.” 27 Graffiti images of doves, flowers, peace signs, and the word love dominate the collection.28

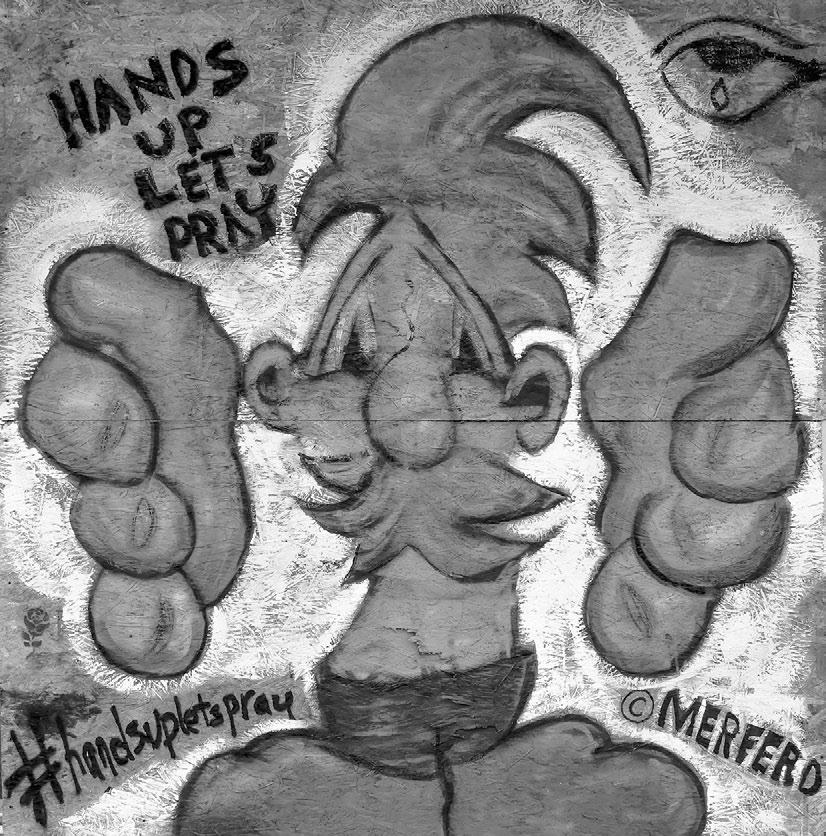

Significantly, there is also a photo of a cartoonish image painted by Phil Berwick of a dwarfish white man with big hands and feet, framed by the words “Hands up let’s pray.” 29 The image coincided with a social media presence—including Facebook and Twitter profiles and the hashtag #HandsUpLetsPray—that, according to a Twitter account, “is a global movement with the purpose of uniting God’s People one church, one community and one nation at a time!” 30 The inclusion of this figure corresponds with Montgomery’s original poem, “Enough . . . Hands up . . . Just Pray.”

Putting aside what appears to be the good intentions of the poets and the community members, young and old, who painted the walls, it is important to understand how this wave of graffiti interacts with previous waves. The graffiti on the gas pump and the mailbox in Ferguson speak to a specific moment of resistance. As the city began to restore order, the universalizing of the “message” began in earnest. Instead of “Fuck the po-

Graffiti image on boarded-up building, Ferguson, Missouri. Graffiti by Phil Berwick.

Photo by Dale D. Gebhardt.

lice,” page after page of images in the book are universal platitudes, such as “Be good to each other,” “Peace for Ferguson,” “We R one,” and “Even in the darkest of nights there is hope.” 31 In these sprayed messages, there are no guilty parties or systemic racism. Instead, the messages reflect an individual responsibility to “be good.” These graffiti reframe the conflict, neutralizing any pointed political attacks. Speaking of a community as “one” instead of identifying the real, deep divisions between Black and white, rich and poor, police and protesters paints over the wounds laid bare in Brown’s death and restores a racial status quo.

This reframing of the protest surfaces in the painfully tone-deaf “Hands up let’s pray” photo reprinted in the book. Michael Brown’s alleged last position taken in his life was with his hands up; he was still shot six times, twice in the head and four times in the right arm. “Hands up let’s pray” erases this specific action that Brown used to protect himself and the material conditions that young Black men face every day in the United States. Instead, the message promotes protection from a mystical higher power (curiously enough depicted as a white male figure).32

The inclusion of a few graffitied “All lives matter” throughout the book underscores the racialized framework that pushes back against the BLM movement, turning attention away from Black people being killed by police to a generic, universalizing “all lives.” Overall, the graffiti “healing” of Ferguson that the book presents is self- evidently an economic one, as evidenced in the image of a white dove with an “Open” sign in its mouth on the boarded-up glass door of a local business. Generic messages of peace ignore the specific material conditions that led to Brown’s death and the subsequent protests. In its “hope” for a return to an economic and racial “normal,” this type of graffiti symbolically erases the racialized physical violence that is meted out on the street.

Taken together, the 2014 Ferguson graffiti can be understood as various graffiti waves that mirrored the (d)evolution of the conflict itself. Violent conflicts often seem to erupt out of nowhere; during the first wave, graffiti often anticipates and/or announces the nascent conflict. The signs are literally the writing on the wall, expressing citizens’ political desires. In some conflicts, the marks are few and quickly erased. At the beginning of the 2010 Green Revolution in Iran, sprayed green Vs began appearing in Tehran’s streets during the middle of the night. These letters prefigured the protests that would be brutally repressed shortly afterward.33 Before the Bronx burned in the summer of 1977, graffiti could be found throughout the poor sections of the city, with tags vying for space on the city’s public housing. As either a whisper, as in Iran, or a roar, as in the Bronx, graffiti is often present in an area before violence and protests erupt, anticipating calls for action.

As the conflict turns to overt violence, a larger, second wave of graffiti appears in conjunction with protesters on the street. From Cairo’s teargassed streets to the Katrina-flooded streets of New Orleans, examples throughout this book illustrate the ways that community members used graffiti to magnify their voices in the conflict’s chaotic violence. These voices speak in numerous dialects, aesthetic forms, and political positionings. It is this wave of graffiti that is most recognized (even if mere background) because of the media focus on the conflict.

The third wave of conflict graffiti transpires after the physical violence has subsided and an area lurches into a tenuous postconflict situation. Here graffiti often transforms again, moving nonlinearly from a voice of minority protest to one of majority suppression. Graffiti aesthetics, which in the first two waves often call attention to blatant inequalities in a community, slowly change. Shorn of uncomfortable politics, “beautiful” images dot the neighborhood, embodying generic universal themes rather than advocating against specific injuries. In some societies devastated by conflicts, entrepreneurs, seeing profit in a neighborhood in flux, often use graffiti to sell a “new,” postconflict area to the highest bidder. These waves, though, are never perfectly formed or clearly demarcated. Dependent on political tides and environmental forces, they crash down upon a particular area, mixing together in giant, messy pools of competing ideological desire. For example, political graffiti was an important resistive tool for Palestinians during the First Intifada as they defied Israeli occupation of their land. At the same time, in raids through Palestinian villages, Israeli soldiers wrote graffiti inside the homes of Palestinians, signaling to soldiers who would come after them particular directional pathways and leaving intimidating messages for the occupants of the homes.34 US soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan tagged latrines with graffiti to blow off steam; others were under orders to use graffiti to sow unrest in villages, thereby opening up spaces for US intervention.35 The speed with which multinational corporations used revolutionary graffiti lettering to sell expensive cars to Egyptians shortly after the Tahrir Square demonstrations was both shocking and significant. As Ammar Abo Bakr and other revolutionaries were painting antigovernment slogans and murals of dead protesters on the walls of Mohamed Mahmoud Street, Fiat Chrysler adopted the graffiti style to sell the “dream” of a post-Mubarak society in ads throughout Cairo that showcased the personal “freedom” a Jeep Cherokee could bring an individual.36 In gentrified downtown Detroit, where street art and graffiti are heralded as helping “save” the city by making it appealing to the affluent, others resist gentrification with pointed, guerilla-style graffiti raids on buildings. In all of these places,

the competing graffiti waves interact and mix together. Some waves are overpowered and break apart; others form larger, messy swells.

No matter the wave, graffiti are often encountered as fetishized aesthetic objects. On Instagram, Twitter, Flickr, and other social media sites, millions of disembodied images of graffiti are posted. Where the individual pieces of graffiti originally appeared—street, neighborhood, city, country—is often undiscernible. Graffiti, though, are historically framed physical phenomena. On walls during a conflict they physically interject themselves into the larger political environment. They enact a performance of resistance, defying a dominant narrative of ubiquitous state power. Graffiti is one tool of resistance among many that reveal the cracks in state power by writing over it. To understand graffiti’s subversive performative power is to explore the state’s performance of its own power through the built environment. These dueling performances are locked in a dialectic struggle; to appreciate the former, one must recognize the latter.

In much scholarly analysis and public discussion, graffiti are often encountered as fetishized aesthetic objects. They are ahistorical clickbait, with little reference made to the walls, streets, and public spaces to which they are attached. My analysis in chapter 1 centers the walls themselves, contextualizing how graffiti transforms them into sites of resistance. I start with border walls—specifically between Israel and Palestine and the United States and Mexico—structures built on the edges of nations with lethal shadows that fall upon certain populations within and outside the walls’ boundaries. Moving from border walls to walls lining a nation’s streets reveals the connections between street protests and conflict graffiti, an important, though often unacknowledged, relationship. The chapter also teases out these connections by placing into dialogue Jürgen Habermas’s ideas of democratic “consensus building” with Chantal Mouffe’s theories of political “antagonisms” in order to identify the politics of writing and reading graffiti in the public sphere. “Walls work!” is a rallying cry of politicians demanding bigger and longer border walls; here I focus on how they perform their work, which lays the foundation for us to interpret how graffiti responds with its own counterperformances. The subsequent chapters focus on graffiti in specific environments. Chapter 2 examines political desire as articulated and interpreted through graffiti in Egypt during the revolutionary days of 2011 when millions of protesters took to the streets demanding the removal of Presi-