Introduction

This history lays out the main developments in social work over two centuries along with the philosophies and thinking behind them. The book takes an expansive view of social work – what it is and what it can accomplish, a broad view found again and again in the work of the practitioners discussed here. The “social” in social work means exactly that – work with a wide social purpose.

The core practice of social work from its beginnings in the turmoil of the industrial revolution was in some measure a brake on the effects of a society rapidly coming under the domination of free-market thinking. The work was with the destitute – those who have insufficient income to pay for the means of life. Social workers provide different descriptions of themselves through time, and used different terms to describe those they assisted – but these descriptions often feel familiar across the decades as this book will show. In this work lies a conception of society – and how it can be improved. Charity social workers of the 19th century called it “raising the district”; we call it improving “community capacity.”

Viviene Cree’s call1 to investigate past practice for its prejudices regarding social class, older people and women is important. A good deal of social work history focuses on its unproblematic development as a profession. This results in an interior history, only occasionally pointing to the context and forces outside the profession, and with a tendency to smooth over conflict and oppressive views. Following the development of practice and values from a social justice perspective opens a critical consideration in relation to a changing society.

There is of course no agreement as to what constitutes social justice, but this flexibility is one of its useful attributes. Social justice has a lengthy pedigree –the earliest use of the phrase that I have found in public discourse appeared in the Liverpool Mercury of November 29, 1811, in a letter to the “Freemen of Liverpool” in which the letter writer links the concept to the overthrow of the divine right of kings – “men became more and more persuaded of their natural claim to freedom, and to as much self-direction as was consistent with social justice.”2 From then on, the phrase is used from time to time in journals and newspapers of a radical bent – more an expression of political hope enlisted to oppose oppression, promote due process and fair hearing and tackle economic disparities by whatever small steps were available.

This book looks at how social workers, as broadly defined, have interacted with those they have worked with over two centuries. In a single phrase it is a book that records, explains and analyses the street-level engagement that social workers have undertaken, beginning in the midst of the industrial revolution when mass poverty became a sufficient concern to supply home visitors – in both charitable and public service – to investigate destitute families’ needs and – perhaps –to assist them.

The work is a search for “recurrent trends in the ocean of past events and remote experiences … to give sense and perspective to the ongoing flux of time.”3 I try to use everyday language and for the most part a narrative form. Case studies are a key source of evidence – they are illustrative of social work’s long walk toward social justice and the impediments it encountered along the way.

A word on terminology. During the early stages of writing, I was hobbled by accidental damage to a finger on my left hand. I turned to a rough and ready dictation system which had the habit of turning the key term “pauper” into “pooper,” “popper,” “party,” “porter.” Thus, I received a symbolic lesson on the slippery, unpleasant connotation of the word which was used both formally and casually throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th century to denote a person who claimed assistance from the poor law authorities. The word had statutory force –but it also stigmatized individuals and families whether or not they were applying for assistance. It was a ready label for presumed cultural and budgetary habits that others in the later 20th century would describe as “the culture of poverty,” or even later as “Benefits Street” behaviour. It was both a legal designation and a term loaded with judgment – a word with which I would prefer to have as little to do as possible. Yet when discussing earlier case histories, it is impossible to avoid the term altogether. This applies to other distasteful designations – such as “mental defective.” When such terms appear here, they do so in their historical context only; not to use them would misrepresent the ideology of the period.

Chapters make chronological progress, albeit relaxed and without fixating on dates. Chapter 1 covers the rights of the destitute and the voices of the poor under what is always referred to as the “old poor law.” Britain in 1820 was the first country to wrestle with the immense social changes that came in the wake of industrialization. The social consequences were without precedent: the migration of hundreds of thousands of people from rural to urban manufacturing centres, or to mining areas to produce the coal that fuelled the revolution. In this upheaval evangelical Christianity emerged as an intermediary force in tackling the destitution and overcrowding associated with industrialization.

Chapter 2 outlines the huge disruption of values in the coming of “the new poor law” and its philosophical underpinning in utilitarianism. From the new regime emerged the first state functionary with recognizable social work roles –the relieving officer. The pressures he – almost always a “he” – worked within and the decisions he had to live with are central to the chapter.

Chapter 3 follows the flowering of charitable and voluntary social work in the second half of the 19th century and the inspirations for that work. By drawing on case records from the Charity Organization Society it examines the assessments

3 and the kinds of decisions the agencies made and brings to light how the voluntary and state provision interacted.

Chapter 4 considers the range of philosophies and the practice in the run-up to the First World War – the concern over young women and sex working, the concern over infant health and strength of the empire, and the spread of civic associations inspired by the new philosophy of Idealism.

Chapter 5 is the keystone chapter. Social work offered a pathway out from under an oppressive domesticity for middle-class women and engagement in public service. The chapter covers the forms of social service that women undertook –and stresses the importance of women’s settlement houses as a community from which a variety of practices emerged and from which university-based training was launched.

Chapter 6 weighs up the immense change in values as users came to be regarded as psychological beings, as opposed to sociological beings. This chapter makes clear that individualization brought with it a wholly different social work that emphasized measuring abnormality, particularly embodied in the arrival of the psychiatric social worker, while at the same time relieving officers were having to deal with post war destitution, industrial strife and austerity in public spending.

Chapter 7 deals with the impact of the Second World War, and the flowering of social democracy within which social work flourished, particularly in a new children’s department. It considers the importance and limits of casework as it emerged after the war and the arrival of generic training. It concludes with a consideration of the Seebohm Report – a vigorous expression of social democratic thinking published in 1968 that heralded the creation of the single social services department in local authorities.

Chapter 8 begins in 1970 with the setting-up of the new departments, and the fractious developments that they had to contend with – child abuse enquiries, radical social workers and trade union action. It deals also with the setting-up of the British Association of Social Workers – through which social work finally formed its own professional association Two statutes propelled social work in two different directions in the 1990s – the Children Act and the NHS and Community Care Act. The statutes added complexity and burden as social workers grappled with free market philosophies while at the same time developing a viable anti-racist and anti-oppressive practice.

Chapter 9 follows policy and practice before and after the year 2010 – in which a change of government took place. The first decade was marked by acute crisis in children’s service brought on by the deaths of Victoria Climbié and Peter Connelly in response to which the then Labour government separated children and adult services. From 2010 the Coalition government elected in that year pursued social work reform within a more directive, top-down structure. Throughout this period the expanding role of the marketplace subsumed what previously was state-mandated provision. The collapse of the College of Social Work only added to the many challenges that social work, dedicated to a better, more just society, faced.

The greater field of welfare, and within it social work, has been, as it continues to be, an arena in which values and practices clash, a field of concern and conflict in which attitudes and ideologies interplay with something resembling a cycle –and certainly not steady, evolutionary progress.

The nature of inequalities – and how social work has conducted itself in a society as riven as ours is the theme of this book. And with so much else the pandemic made inequalities more visible. Low-paid workers – carers, healthcare support workers, delivery drivers, shelf stackers – are working in dangerous but essential lines of duty. The young and active are paying dearly – educational opportunities forgone, income lost, careers on hold. What will be their part in a redrawn future? What equitable restitution can be made for them?

But this is what we cannot know at the moment. “[T]he past is all that makes the present coherent, and further, that the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly” wrote James Baldwin.4 It is not until the past is examined in light of the present that we can fully understand what the present signifies and what the future has in store. The mission of this book is to give due credit to the accomplishments and views of those who went before. There is a tendency to regard the past as merely a preparation for the way things are today, that the present is a culmination of human effort. But as the human rights authority Samuel Moyn has written, “our ancestors were trying to be themselves rather than to anticipate somebody else. The past is not simply a mirror for our own self-regard.”5

Notes

1 V. Cree, “Khaki Fever” during the First World War: A Historical Case Study of Social Work’s Approach towards Young Women, Sex and Moral Danger. British Journal of Social Work (2016) 46, 1839–54.

2 ‘Letters to the Freemen of Liverpool’, Liverpool Mercury, November 29, 1811.

3 C. Pollitt, Time, Policy, Management Governing with the Past (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2008), p. 37.

4 J. Baldwin, Autobiographical Notes Collected Essays (New York: Library of America 1998), p. 7.

5 S. Moyn, Human Rights and the Uses of History (London: Verso 2014), p. xii.

Family visiting and the relief of poverty

On January 19, 1819, three American sailors were walking through Cheshire toward Chester, presumably to go from there to Liverpool for a ship home. As they passed through the small rural parish of Duckington some 10 miles south of Chester (still there and still small), they were broke and sought financial assistance from the parish official in charge of providing relief for the indigent. They were successful in their request for we read in the parish records: “To three American sailors with a pass 1s 0d.” The sum of money was small1 but sufficient to send them on their way along with a pass to indicate that they were not vagrants.

This brief record tells us something about the way assistance was administered under the “old” poor law in England and Wales. The sailors were low on cash –we know that much – they needed something to eat and official permission to pass through the parish and move on toward Chester. We do not know why they were there in the first place, nor do we know whether they were wastrels prone to drink. They could have been pressganged by the Royal Navy or taken prisoner on the high seas during the brief but violent war of 1812 between the young US republic and Britain, but if the parish official in charge of providing assistance knew of their circumstances he makes no mention of it as judging claimant’s character to ascertain whether she or he was ‘worthy’ of relief was not part of his remit.

They were not the only sailors helped by the parish that year for we find in the same parish record the later entry: “To relieving 5 sailors with a pass 0s 10d on 18th of August.” (Note that they received 10 old pence, less than a shilling for the five sailors, and a good deal less than the three Americans.) Parish “overseers” –the officials, who oversaw the distribution of poor relief in the locality – were only too glad to help sailors, or any other travellers, to move through their small parish; should travellers find some reason to stay – for example fall ill or injure themselves – they could become “chargeable” to the parish. For the same reason we read: “To a vagrant in the rode -2s; To a man with a pass 0/6d To a sick woman found in the road – 2s.”2

The office of parish overseer was voluntary, chosen annually to raise local taxes (“poor rates”) from those owning or renting property above a certain value threshold. Most claimants were actually long-term resident (or “settled”) in the parish which was the legal status that determined a claimant’s right to apply for assistance from the parish in the first place. Broadly, a person was settled through

DOI: 10.4324/9780429024276-1

Family visiting and the relief of poverty

birth in the parish, by holding a job for a number of years or through marriage to a “settled” inhabitant. The overseer’s job was to decide which claimants would receive assistance and whether it would be in cash or in kind. He was the front end of the “old poor law” established as a system of national assistance in 1601, in the last years of Queen Elizabeth’s reign – An Act for the Better Relief of the Poor. Under that statute and others that followed every parish in England had a legal duty to raise local taxes from those above a set value of property to maintain the poor. Although designed for a largely rural economy the principles of the old poor law endured for over two centuries.

The law embodied two critical principles for destitute residents legally settled in a parish: 1) a right to work: if the claimant could not find work and was an ablebodied male, the parish would set him to work maintaining roads or bridges and pay him for it; and 2) if a person was destitute he or she had a right to assistance (referred to as “relief”) for those settled in the parish. The law embedded something of immense value: a moral commitment to support the poor. Their needs were assessed and provided for on a no-fault basis. No formal judgement was made between those “deserving” assistance and those who did not. All decisions regarding assistance were made within this legal framework and not a matter for charity. In short, the “old poor law” was law, based on parliamentary statute and common law.

Help under the old poor law “was not directed to a separate underclass but was an established part of the social system to which a large number of people might have recourse.”3 Assistance responded to primary needs – clothes for warmth and for work, food for sustenance, medical assistance, coal for heating, bedding and funeral expenses. By the early 1800s an estimated 10 per cent of the population of England received some form of income support from the old poor law.4

Rights under the old poor law were well established in the popular mind –part of the “moral economy of the poor”5 – a conviction that the right to claim overrode free market concepts which paid no heed to ideals of fairness and justice. This conviction survived well into the 19th century with roots in common law. Surveying this history, Professor Lorie Charlesworth commented that welfare “is not simply the brave new world of Beveridge, but a fundamental cultural and legal norm long embedded within our society,” which she traces back to the old poor law.6 The sheer volume of poor relief paid out through the old poor law demonstrates the broad acceptance of this right. Charlsworth concludes:

The ordinary every day payments are recorded because they represent the performance of parochial legal duties and obligation to the poor and must be accounted for annually to the justices. … historians miss their significance: that the settled poor possess a legal right to relief7

Local administration of poor relief in England and Wales (Scotland had a different poor law system explained below) was decentralized with civil authority largely embodied in the local parish. Those in need of assistance and the ratepayers who would pay for that assistance were known to one another in the mostly rural parishes,

Family visiting and the relief of poverty 7

usually of no more than several hundred persons. Assistance to the destitute was relational, face-to-face work. The theme of reciprocity is evident during the early 19th century between the better off and those living near or at the subsistence level.

Duties lay heavily on the overseer, who after all served only in a voluntary capacity. He was responsible for judging the validity of claims – potentially a difficult, stressful job. Ultimately the overseer was personally liable in law – the claimant/pauper who felt unjustly served could appeal his or her case before local Justices of the Peace; if a destitute person had been refused relief and subsequently died, the overseer could be indicted for manslaughter.

An entry in the Duckington records indicates the lengths that overseers would go to ensure that timely assistance arrived: “To a journey [of 17 miles] taking widow Buckley’s rent to Wem 5s/0d.”8 .

The Duckington accounts from May 1815 to May 1816 also record the help provided to a woman at the birth of her child:

“18th July To Margaret Nevitt child 13 weeks pay at 2/6 per week -£1.12.6d;” and continues, “Paid Mrs Phillips for attending Margaret Nevitt £1.1s.0d” (to be attendant at the birth).

In the following month we read: “10th June To Widow Nield while ill 12s2d” and a few days later: “To Widow Nield burial fees, coffins and a person coming over £2.4s.0d.”

Payment for funerals is frequently found in parish records; to be laid to rest with respect and dignity was of the greatest importance but the expense of even a modest funeral was beyond the means of some families. So we read the accounts of Ebeneezer Allwood, overseer and an eccentric speller if there ever was one, covering the cost of Breeley Cote’s funeral in 1818:

To Breeley Cote 10s 7d; [presumably to cover cost of a medical officer]

To Breeley coffin £1.14s.0d; to Breeley burial fees – 5s/6d;

To Breeley a poors ley (levy?)

To paid for Breeley borrad money 6s 0d. [covering a debt of hers?]

To a man cuming to tel us no[w] Breely being Ded 3s/0d.9

Clothing for work and warmth were necessary items and providing them a form of prevention, staving off destitution. One of the ways parishes reduced costs was by placing the children of families who were being supported by the parish, into service – allocating them to local farmers and ratepayers to get them off the parish lists. In 1822, for example, the parish officers at Hungerford “Ordered that James Woodley have 1 pr. of shoes & a jacket and if he does not continue in his situation the jacket and shoes to be returned to the parish officer.”10

Claimants define their own needs

The needs that people had and the kind of assistance they were asking for survive in the letters they wrote – or had written for them – to their parish authorities in

various parts of England. Many were from those who had recently left their home parish in search of work elsewhere but were still reliant on assistance from their home parish.

The “pauper letters” from claimants in Essex describe the personal circumstances such as unemployment or illness, that made them destitute. Often, they are very direct in asking for the assistance they need – and reveal the lengths that they expected overseers would go to in assessing and providing relief.11

Among the most frequent problems they wrote about were: 1) coping with infirmity in old age or disability (particularly with numbness and uselessness of hands and legs – a critical impairment in an economy dominated by manual labour), 2) parents with children that they are unable to feed and clothe; 3) the plight of widows; 4) paying for funeral expenses.

Other needs were also prominent: young women who could not afford to buy the clothes they needed before going into service; low wages that had to be supplemented during periods of “slack trade” (what we would call shortterm unemployment or underemployment); compensation for accident and injury, often at work, and assistance for the family where the “breadwinner” either had gone to or was returning from prison. There were also appeals for help from undernourished families, for doctor’s services and medicines and for supporting a mother on her own with children for whom the father refuses to pay maintenance.

From these letters we can also draw a list of the items deemed necessary to live, a “necessities”-based definition of poverty similar to that used by researchers in the late 20th century. There are no luxuries here – to be deprived of any of these necessities would mean life and livelihood were at stake. The tone of the letters is always respectful but written in the context of reciprocity that underpinned the poor law. (I have left the spellings, capitalizations, grammar and syntax as they are in the originals – and have reproduced the layout as closely as possible.)

Letter No 140: From Lucy Nevill [in St Botolph, Colchester], January 15, 1825

Jany 15 1825

Sir

this is to certify that my Son Abraham is alive and well and is as four Years Old the 17th of last Jany I would have come over with him but being in service I can not leave my place hope therefore you will send the money by the Carrier and you will oblige your Humble Sert signd Lucy Nevill12

Comment: Lucy Nevill is in the service of a household, perhaps a farmer’s family, committed to a round of domestic chores, with a four-year-old son for

Family visiting and the relief of poverty 9 whom she receives cash support. It is impossible for her to appear before the parish authorities in person because she is working but it is notable that she is quite at ease in asking for the overseer to send her money by a carrier to her workplace. She also has basic confidence that her explanation, short as it is, will be read with some understanding on the part of the decision-makers and that they will meet her request to send her the money via a third-party carrier.

Letter No 142: From Susannah and Davey Rising in Halstead [Essex] to the governor of the poorhouse in Chelmsford January 27, 1825 Halstead January 27 1825

Honread Gentellmen I once more make Fre[e] to wright to you hoping you will Excuse my Freedom A[n]d parding the liberty I take in So do[in]g As Necessity Forsess me So to do and the Furder Contents of my wrighting is to Inform [you] that my Husband is Weary Bad And Cannot help himself No more than A young Child and Cannot go Across the house if he Could gain [A th]ousand pound Neither Can he Go to bead nor Get up without A man to help him to Bead and From Bread I cannot shift no for Now my husband is laid Aside All is Laid Aside with me therefore I must Surmit [your] Ge[nteel] m[en] mercy For if you Gentellmen do not pleas to help us we must Give up housekeeping For out of nothing thear Ca[n] [be nothing] Done Consider our Destress and Send us Speedy help if you pleas

Your humbells Servants Susannah And Davey Rising.13.

Comment: Susannah Rising makes her points clearly if not in perfect English: her husband is confined to bed. While his condition is unspecified it presents her with difficulties so severe that the couple may be facing starvation. As she so eloquently puts it, “my husband is laid Aside All is Laid Aside with me … For out of nothing thear Can be [nothing] Done” and concludes by asking the authorities to send assistance speedily to ease their distress.

Letter No 153: April 15, 1825. In Susannah’s next letter we learn the couple have a son: “my son Thomas is weary Bad with the hucking Coff” … “And I am in A weary poor State of helth myself And uncapabell of doing For myself or Family.”14 The parish response was to ask the family “to come home if they want more Relief” – that is to return to the parish where they are “settled” and therefore entitled to relief over a period of time. This the family were unable to do. Susannah continued to write to parish authorities in Chelmsford who eventually agreed to provide her with occasional relief payments.

Letter No 162: From Ann Herbert in Bermondsey London June 1, 1825

Sur

I received your letter and I am still Living and I am now entered in my 63 year I git my Livelehood by plain Knedle work and on a Fair Calculation I

Family visiting and the relief of poverty

can say truly it will not a Mount to more than 3 shillings pr Week – as my Helth is in a very precerous State – and I am very unwell at the present. But having my Daughter with me tho she has very Bad state of Helth that renders her – Incapable of servitude to Gether by industry and What you are Kindly allowing wee G[ett] Due – this is a Just and true Statement – you may Depend on – I am Sur – with great respect

Yours ann Hurbert15

Comment: Ann Herbert had been receiving 2s 6s a week for several years up to this point. The overseer in Chelmsford, John Sheppee, had visited her in London in December 1823 – (and visited other claimants in London on behalf of the parish at the same time) and submitted this assessment: Ann

considers that if herself and daughter get 6 Shillings in One Week, it is a good Weeks work, but they generally get about 4s/, as her daughter has a very bad state of health; – their employment is Needle Work; – they bear a very good Character and have been in the present Lodging 15 years, – they pay 2/6 pr Week for one room, – From Appearance I think they are deserving of some allowance, as one or the other is constantly unwell,16

Cheshire historian David Hayns has argued that for all the apparent strictness of settlement requirements – claimants had to be legally settled in the parish from which they were claiming assistance (unless, as with the sailors, they were travellers intent on passing through) –claimants received adequate, even generous, treatment from the overseers which went well beyond cash supplements. Overseers, he concluded, “paid for building houses (thatching and wattle), ground and tools (shovels) to cultivate it; fuel (coal) for heating houses; and sometimes for multiple resources – house rent, coals and washing; improving/fixing fire places.” Payments for children’s clothing were regular; four yards of linen cloth, clogs, shirt and waistcoat, flannel petticoats. He concluded from Cheshire parish records that “the humanity of parish Overseers is demonstrated by the care, evident from their accounts, that they showed for the poor during times of birth, marriage and death.”17

The values of the old poor law lasted in the popular mind well into the 19th century: in particular, the sense that there was a right to assistance if a person became destitute, played a role in resistance to the “new” poor law adopted in 1834 discussed in the next chapter. Critics of the old poor law targeted the sense of entitlement in language that we are wholly familiar with today: it was too generous, it created dependence, and undermined the will of able-bodied labourers to work. From 1815 these attacks became more pointed, particularly as expenditure on the poor began to rise, and became more ideological focusing particularly on the supplements to low wages paid by some parishes which in the eyes of the nascent science of economics was a flagrant violation of free market principles.

Needs as described by Essex claimants in the 1820s

Coping with infrmity and/or old age

For a disability, (numbness and uselessness of hands and legs are cited)

Parents with a number of children to feed and clothe

Clothing for warmth or for work, for example young women going into service

“Slack trade”/wage supplement (for what we now call “underemployment”)

Accident and injury

Breadwinner either in or just returning from prison

Lack of food/starvation

Workmen’s tools

Doctor’s services and medicines

Lone mother with children – Father refusing to pay maintenance; need for family support

Later stage of pregnancy and “lying in”

Rent (to avoid being sent back to home parish)

Illness – to family members/breadwinner

Funeral expenses

Facilitating settlement elsewhere – especially prominent in the Essex collection of pauper’s letters

Paying dues for their club or friendly society

Addiction – rarely identifed specifcally but evident in description of individual’s drinking habits

“Hiring a woman” – to look after children and to care for the sick

Emigration

Social unrest

The period after the war with Napoleon which ended at the battle of Waterloo in 1815 was a time of heightened domestic unrest. Britain had been the first country to industrialize – there were no prior examples of the social consequences following the rapid introduction of factories and machinery in mill towns. Nor were there models of how to deal with the migration of hundreds of thousands of people from rural to manufacturing centres as they looked for work. The pre-industrial experience of local reciprocity between the poor and the better off was difficult to apply to the unemployed of Manchester, the Lancashire cotton towns and the Clyde Valley. People were subject to a new time discipline determined by the working day in the factory as they left behind the ways of the smaller-scale householdbased economy of small towns and rural areas. Artisans from a pre-industrial time – epitomized by the handloom weavers working at home with the whole family contributing to the production of cotton or woollen cloth – were either forced into labour in mills where power looms produced cotton or wool cloth or face unemployment.

12 Family visiting and the relief of poverty

It was a time of unprecedented hardship. Civil unrest grew in the northern manufacturing districts as handloom weavers under the brand name of “General Ludd” (hence Luddites) dismantled the mechanized looms factory owners were installing – and that were putting them out of work – occasionally burning workshops as they did so. The government cracked down on this making the destruction of mechanical weaving “frames” a capital offence with a sentence of death for those weavers who were caught. The poet Lord Byron spoke passionately in the House of Lords against this repression and bitterly mocked those who authorized it in his poem “Ode to the Framers of the Frame Bill”:

Men are more easily made than machinery –Stockings fetch better prices than lives –Gibbets on Sherwood will heighten the scenery, Showing how Commerce, how Liberty thrives!

Some folks for certain have thought it was shocking, When Famine appeals, and when Poverty groans: That life should be valued at less than a stocking, And breaking of frames lead to breaking of bones.18

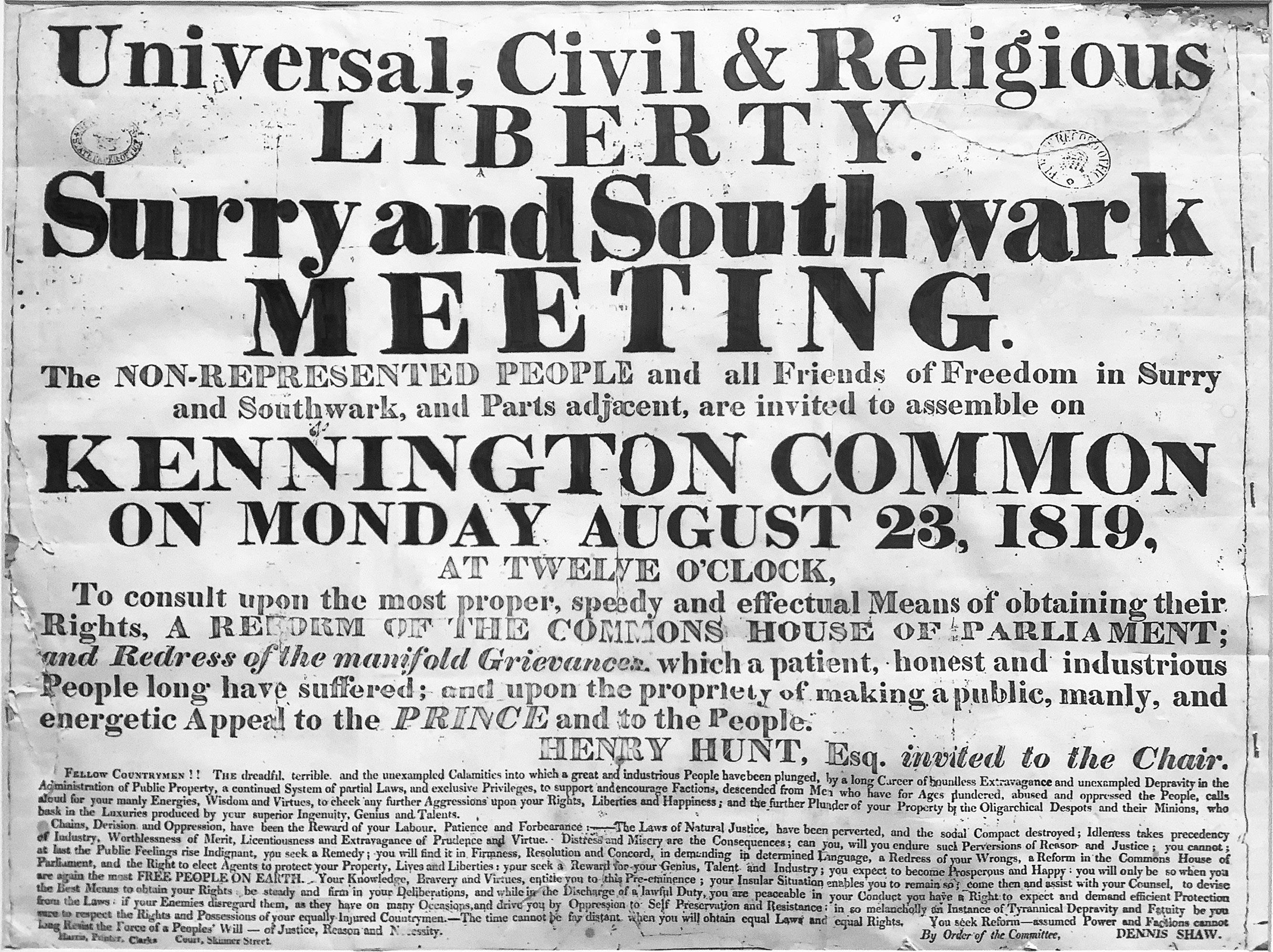

A series of mass demonstrations mobilized by political radicals drawn from artisan and urban workers urged extending the vote which at that time was restricted to a small group of propertied gentlemen, and to reform parliament in which many seats could be bought and sold (see Figure 1.1). The climax of this extended campaign took place at a demonstration in Manchester in August 1819 when mounted cavalry attacked the crowd of 60,000, with some 18 demonstrators killed. This repression, quickly dubbed “Peterloo” in ironic allusion to the final battle with Napoleon, moved the poet Percy Shelley to condemn the massacre and the government ministers in London behind the repression. Among these was Viscount Castlereagh. In “The Masque of Anarchy” Shelley wrote:

I met Murder on the way He had a mask like Castlereagh

Very smooth he looked, yet grim Seven bloodhounds followed him. All were fat; and well they might Be in admirable plight, For one by one, and two by two, He tossed them human hearts to chew Which from his wide cloak he drew.

The environment of political unrest, rapid industrialization and campaigns for parliamentary reform brought a sense of urgency to government circles and wider

1.1 Demonstration at Kennington Common. Poster for the demonstration for parliamentary reform at Kennington Common with Henry Hunt, who was also the main speaker at Peterloo, in the chair.

middle-class opinion to reforming the working class. The poor law came under sustained attack, claiming that it undermined the independence and individual responsibility because it was a statutory right that required no test other than destitution Other critics pointed to the fact that it pressured labourers to remain in their parish if they were to qualify for assistance, an anathema to the growing class of manufacturers who wanted a labour force free to move unencumbered to the fast-growing industrial centres.

Evangelicalism and voluntary charity

The move to reform the poor law joined hands with a powerful, diverse coalition of reformers aiming at persuading the poor to renew their sense of personal responsibility through a rededication to Bible and Christianity: evangelicals. Early 19th-century Christian evangelical thought19 focused on the individual for whom redemption was conditional and not guaranteed. Its theology was a moderate Calvinism, not of fire and brimstone, and oriented toward social reform including opposition to the slave trade (outlawed in Britain in 1808) and prison reform. As a leading historian summed up the movement:

Figure

The most assurance that the individual could hope for in this world was a sanctified life, the evidence for which was perseverance in good works. In this way salvation by faith in the redeeming power of Christ’s sacrifice came necessarily to require some corroborative effort through attempted “works.”20

A belief in personal sin and universally fallen human nature required sacrificial atonement for salvation and in this evangelicals were far less optimistic about human reasoning and institutions than other reformers.21 Perhaps this explains the intensity of their voluntary reform work across so many areas – juvenile street crime, prostitution, vagrancy and begging, temperance and cruelty to animals. Their willingness to set up new voluntary organizations played an outsized role in 19th-century social reform.

While evangelicals were progressive in many areas of reform, in relation to the destitute they struggled to accommodate their belief in the principles of the self-regulating market economy with the demands of their moral code of atonement and renunciation of luxury and ostentation. Philanthropy and charitable works were the means through which any apparent contradiction in reconciling pursuit of profit with ethical and moral outreach was overcome and individual redemption secured. As Young and Ashton framed it in their now decades-old history of 19th-century social work: evangelicals “felt genuinely their duty of private benevolence; what mattered was not how wealth was acquired, but how it was spent.”22

For evangelicals, the urban working class appeared beyond the reach of church and chapel, remote from Christian ethic and conduct. Addressing this issue, they poured great energy into reforming urban working-class behaviour. The range of engagement had many outlets: Sunday schools, soup kitchens, night shelters, a Sabbatarian movement opposed to profanation of the Sabbath, societies to distribute bibles and religious tracts.

In return for charitable aid, whether educative or financial, campaigners expected the recipients of this charity to live up to their same high moral standards. In this they were bound for disappointment because they could not conceive there were forms of poverty that could not be alleviated through Christian philanthropy.23

Mendicity Society

The pre-eminent evangelical society in the early 19th century social work with the poor was the Mendicity Society. Its formation in 1818, originally only in London, can fairly be characterized as the first large-scale voluntary personal social service organization in England. Long before the Charity Organisation Society, the Society developed systems for responding to destitute individuals, by collecting information, assessing the worthiness of claims and recording decisions taken. Its home visiting programme and method for assessing needs offered a model 50 years later for the COS which adopted some of its practices and fell into some of its errors.

In the years after Waterloo in 1815, no problem worried political authority and middle-class opinion as much as begging or “mendicity” as it was then called.24 The Mendicity Society viewed begging as caused by the credulity of the public prone to the sympathetic and generous response to such ploys as children, trained by adults, pleading for aid. The society was convinced that local parish authorities were turning a blind eye to begging as an offence (which it was, under the 1744 Vagrants Act and consolidated under the Vagrants Act of 1824 still in force today), and apparently reluctant to return vagrants to their parish of origin. The fact that London was a magnet for migratory labour at a time of a rural labour glut was not part of their analysis. Other structural factors also contributed to the rise in begging: disabled veterans, former sailors unable to find work, delinquent youth which emerged as a problem during the lengthy wars with France and dispossessed weavers, among others. That there were structural reasons for the increase in begging - economic forces which drove a proportion of people onto the streets to ask for help - was outside their construct of the problem.

Society members believed the pathway to a good society was through reclamation of the most destitute, one individual at a time. Indiscriminate charity to beggars, vagrants and needy children corrupted the recipient by undermining their sense of personal responsibility and motivation to work. The proper aim of charity, rather, was to foster personal ambition and achievement.25

The society sought to reinstate charitable assistance as “a gift,” one that would act as a moral force in the lives of both the giver and receiver of charity, and reestablish a strong relationship, or “good feeling” between social classes – “hearts” triumphing over class boundaries. “True benevolence” required investigation of the circumstances of each potential recipient with a view to distinguish the “deserving” from the “vicious.” As Roberts summed it up:

from the world of business and labour discipline into the world of charity: investors in works of charity were to be as entitled to make decisions on the basis of full information as in any other area of market choice. The involuntary subsidy to waste and injustice would be ended, freeing resources for cases of legitimate need.26

Mendicity Society practice

Driven by its enthusiastic and young general secretary, William Bodkin, the Mendicity Society was both paternalist and more systematic than other evangelical organizations in the field. To ensure it offered assistance only to the deserving, the society distributed tickets to members of the upper-middle class, who in turn gave these, rather than money, to beggars. The beggars were then to turn in the tickets at the society office where their individual circumstances were thoroughly examined. The investigation of the character of the beggars was intended to be rigorous – in society parlance, “rigid and minute inquiry, may invariably precede relief.”27

The society’s conception of begging embraced a wide variety of requests for help. To ensure that they were legitimate its officers sought information on each ticket holder regarding family life, employment history, parish of settlement and the rent they were paying. Investigators wanted to know whether any poor relief had been received, whether belongings had been pawned and whether the applicant was in debt. Judging character was equally important. At interview applicants had to explain why they were reduced to begging – and how they obtained their ticket. They had to supply a reference from “a creditable person who will vouch for your veracity and general character” which was itself double checked and was regarded with suspicion, even if from respectable individuals who themselves could be duped by “artful representations, and speak from an opinion hastily adopted, rather than from information actually obtained.” To investigate further, society visitors interviewed neighbours, landlords and local shopkeepers used by applicants. In so doing they made every effort to dress “as a gentleman to give authority to his questions.”28

The society encountered difficulties from the start. Identifying those “truly deserving” of assistance proved a time-consuming task and for the gentlemen the society recruited as home visitors totally perplexing.

At the time of severe frosts, when there is a great press of business, the establishment [i.e., the volunteer staff] is frequently detained at the office till past 10 o’clock at night, breathing the fetid air which the presence of many hundreds of squalid beggars has created in the course of the day, their constitutions predisposed, by exhaustion and disgust, to contract the sickness against which no adequate precaution can be employed.29

There were also problems of organization, and the effort to overcome those as well as recruit salaried agents ballooned the budget. In trying to refute charges that it was lavishing funds on itself rather than the destitute, the society gave plenty of ammunition to its opponents. As the society’s annual report put it in 1822:

Extensive premises are required, an able and upright superintendent is indispensable; and subordinates for their zeal, labour, endurance, and trustworthiness, are only inadequately remunerated. Constables must be maintained; accounts kept; a miller, a superintendent of the stone-yard, a mistress of the oakum room – must all receive wages; as do cooks to dispense the tons of bread and cheese and hogsheads of soup so freely bestowed.30

But significant evangelical leaders like the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce renewed their support for the society and the crisis in public confidence was surmounted.

Its full-time visitors were paid 30 shillings a week – a substantial sum for the time; they must possess integrity, judgement and acquaintance with the weaknesses as well as vices of mankind. They must dress as a gentleman – giving authority to his questioning of applicants and interviews with referees. In due

Family visiting and the relief of poverty 17

course the society itself began to see the behaviour of those they helped in a more complex way: “It has at all times been difficult to discriminate, between the individual, who leaves his home from a sincere desire to obtain employment, and him who has adopted a life of habitual vagrancy.”31

The society itself discovered that many applicants wanted to work but could not find employment. An examination of over 2,000 recipients of assistance from the society found that the vast majority were destitute women with no option to survive other than begging.32 It was also caught by surprise in the numbers of children among the beggars – on occasion more than half. In times of recession or severe winters the society could not process all applicants – there were too many. In 1819 and again in 1830 it was compelled to give relief, no questions asked, in order to meet mass distress.

Between 1838 and 1848 a series of trade depressions plus the eventual ripple effects of Irish migration from famine caused demand for emergency relief to reach a level which the society became desperate to ease but could not. Finally, in January 1848, disaster struck: 20,000 Irish poor “besieged the doors” of the relief office in London, the society was denounced by neighbours for attracting rather than deterring vagrants, and typhus carried off seven members of the office staff.33

The society had vocal critics (see Figure 1.2). A widely disseminated public letter by “Castigator” criticized the small coterie of managers who had formed an exclusionary and self-perpetuating clique – with vacancies on the board available only through “death or quitting the kingdom.” Marshalling support for resolutions before business meetings became common practice. “Thus,” wrote Castigator, “once a Manager, always a Manager.”34

The anonymous author noticed that for the Society the relief of real distress is placed last, and the thought of coercion stands most prominent. You seek for objections against, and not reasons for, giving assistance. You ask not, is the poor creature distressed? But has he not been in the habit of writing for relief? Is he not in debt? Has he not a bad character?

Claimants had to submit to a “holy inquisition” “which pries into the secrets of frequently some of the most respectable families in the kingdom – and in which the chief heresy is – being destitute, without money, and without friends.”35

The writer particularly objected to the existence of a “Black Book” in which the names of 800 individuals were recorded as the main instigators of the begging letters who, according to the society were of “the lowest order.”

“Stigmatizing hundreds of persons as ‘worthless’ who have merely a little family pride, might be avoided,” Castigator wrote. If the society assumed the distress is real from the start “it is Christian duty to relieve him.” But he argued, the society maintained its hard line, proclaiming “any person, old or young, male or female, who gives money in winter to a woman begging about the streets with young children in her arms or company, is guilty of an act of positive cruelty.”36

Figure 1.2 “Mendicity Unmasked.”

Mendicity Society case studies

The society developed a hierarchy of claimants’ worthiness: from the “blameless” (including seduced women), through “the Irish and Scotch,” “foreigners” such as trafficked Italian street children and “beggars.”37

Cases from among “the blameless” were easier to respond to within the society’s perspective. One summary in this category reads:

No. 12,915 – J. Y. a Seaman, aged 24, having no settlement, appeared with a few rags only upon him, and almost famished. A captain in the Royal Navy having given him an excellent character, no means were spared to get him a ship; but from the low state he was in, and the limited demand for sailors at that time, three months elapsed before his case was finally disposed of, during which period he was supported by the Society. A complete set of clothing was given him, and he was put on board an outward bound vessel, grateful in the extreme for the kindness he had experienced.

Another summary, that of case “number. 13,745 – E. N. aged 18, native of Ireland,” is portrayed as

a decent respectable girl, left Dublin for London in the expectation that her sisters, who were servants in a nobleman’s family, would be able to procure her a situation. On arrival in London, to her great mortification she found the family were in France. Her funds being exhausted, and no friend to fly to, she stated her case to a watchman, who happened to come from the same part of Ireland, and he very kindly took her to his home; but being very poor, was not able to support her. She procured a ticket-[her] story was found correct, and she was advised to return to friends in Ireland, and sent over at the society’s expense.

Even within Class Four – “Beggars who belong to Parishes in the Country” – the chief target of the society, the case studies reveal greater understanding than the official remit of the society would suggest. For example, “No. 13,746 – W. K. a decrepit old man, respectable connections, whose parish was in Berkshire. Upon the Society’s application, an allowance was obtained, which is paid in weekly at the Society’s Office.”

Also in Class Four:

No. 13,574 – S.C. a gentleman’s servant who belonged to Shropshire, had lost his place [of employment], and become greatly distressed from an affection [infection] of the knee, which entirely disabled him. The Society sent him to an Hospital where he was perfectly cured. A situation was afterwards provided for him, and the clothing necessary to enable him to enter upon it was given.