of the coastal and inland promontory forts and enclosures of Scotland

Stratford Halliday and Ian Ralston

Introduction

In this paper, which we are delighted to offer to John Collis, we wish to take stock of a particular subset of the sites included in the Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland, a project funded by the AHRC 2012-16 and published online in 2017 (Lock and Ralston 20171; https://hillforts. arch.ox.ac.uk/). The subset we will focus on comprises the Scottish promontory forts and enclosures, which make up almost 30% of all the entries for Scotland. Some of this material will be incorporated in the Atlas volume to be handed over to the publisher in 2021, but the promontory sites of Scotland highlight many of the issues involved in the wider study of enclosed sites in Britain and Ireland, and the discussion of the sites themselves is worth airing in greater detail. On the one hand they expose such prosaic but important issues as classification and chronology; on the other they extend to more testing topics such as issues of function for sites which can occur in highly exposed locations where routine inhabitation may always have offered considerable challenges.

At the national scale Scottish promontory forts have received relatively little attention in recent years. Some of the more unusual examples, such as the coastal sites of Burgi Geos in Shetland [4169] and Burghead in Moray [2925], figure in Harding’s overview (2012) where he rightly stresses that – as is the case for other suites of hillforts – topographic position is not a guide to their chronology (2012, 288). Coastal promontory forts are also a conspicuous component of Toolis’s studies of Galloway (2003; 2007; 2015), but the most recent attempt at a national distribution map, albeit schematic, was that produced by Raymond Lamb (1980,5,fig. 1). In common with all these studies, Lamb focused exclusively on the coastal examples.

In several places in this study we have included the promontory forts of Northumberland in the commentary, because in many ways the later prehistoric

enclosed sites of that county – in both numbers and characteristics – much more closely parallel the world to the north of them than that of the counties to their south, where forts of all kinds are altogether rarer. Thus, Northumberland is the southern flank of a region that we here term ‘Greater Tyne-Forth’, which extends eastwards from the North Sea coast of East Lothian and Berwickshire to include Dumfriesshire and southern Lanarkshire.2 Atlas data demonstrate that the counties of this region are in the top quartile in terms of site numbers per unit area, whereas those to the south are in the lowest quartile (Lock and Ralston 2020, fig. 4); this is the starkest such gradient in the British Isles.

In Scotland alone, a total of 502 promontory enclosures have been included in the Atlas database (see Fig. 1 and Map 1), and there are a further 19 in Northumberland;3 another 29 fortified enclosures occupy promontory positions in topographical terms, but these enclosures belong to other categories and are not considered here. The Scottish entries are divided between 301 distributed around the lengthy hard-rock coastline and 201 which occupy inland positions. Of the overall total, 399 have been ‘Confirmed’ as forts according to the criteria agreed at the outset of the project (Lock and Ralston 2017 and 2020; see Halliday 2019 for a full discussion of the criteria with respect to Scotland): 236 of these are coastal and 163 inland. These 399 sites represent 41% of all the Confirmed entries for promontory forts in the Atlas database for the whole of Britain and Ireland. While these represent the focus of the paper, it is important to also explore the character of the additional 97 that are deemed ‘Unconfirmed’, and the further six marked as having ‘Irreconciled Issues’. In what follows, these are discussed first, the issues that they raise serving to both sharpen and qualify the definition of those Confirmed. The assessment of the latter then follows, with further sections on the character of their defences and internal features and the related series of scarp-edge forts.

1 Individual sites in the database can be accessed by their name and four-digit numbers, here provided in square brackets. The database entries include site bibliographies generally not quoted directly in this paper.

2 For this study, we have retained the pre-1974 counties as the most convenient and best-known geographical divisions. The regions we have used include Greater Tyne-Forth – by which we designate all of south-east Scotland plus Northumberland.

3 Northumberland includes 12 Confirmed, 4 Unconfirmed and 3 Irreconciled Issues sites.

1. A maximising view pf the distribution of inland (N= 201) and coastal (N = 301) promontory forts in Scotland drawing on Atlas data (N = 502).

Stratford Halliday and Ian Ralston

Map

Defining the Dataset

The criteria against which all the entries in the Atlas have been judged rest on three key characteristics, namely physical advantages of the topographical position, scale of the enclosing works, and size of the interior, for which a lower limit of 0.2ha was set (Lock and Ralston 2020). Applied rigorously, however, it was foreseen that numerous well-known Scottish forts would be omitted, and the decision was taken to operate these qualifications to include enclosures that met at least two out of the three criteria. This had far reaching consequences, leading to the inclusion of numerous small fortified enclosures which otherwise would not have qualified. What was not foreseen, however, is that these same criteria also embrace the morphological character of a series of other promontory enclosures that have never been conventionally considered as forts, be that prehistoric or early medieval. To some extent this may be a reflection of the extensive use of Scottish promontories for various purposes at different times, though shades of the same issues are clearly present in Ireland, but we felt it was better to err on the side of caution by including this wider range of ancient promontory enclosures, rather than omitting them and denying the choice of further exploring these sites to the user of the Atlas data.

The overall total of 502 entries thus represents all the promontory works in Scotland that appear to be of some antiquity, the principal exceptions being most medieval stone castles exploiting promontory positions. The emphasis here is placed on the word ‘most’, because several castles clearly occupy earlier Iron Age promontory forts, such as Cullykhan, Banffshire [2982], and Dundarg Castle, Aberdeenshire [2983]. In other cases, notably at Greenan Castle, Ayrshire [1289], and Innerwick Castle, East Lothian [3928], cropmarks have revealed ditch-systems that appear eccentric to the visible medieval defences and are thus considered more likely to relate to a different and earlier phase of activity. This contrasts with several castles where early medieval texts indicate the likely site of a promontory fort, but no evidence of any earlier defences is visible and none has been recovered by small-scale evaluation; Dunnottar Castle [3112] on the Kincardineshire coast, examined by the Alcocks (1992), is the prime example, but others might include the rocky outcrop of Dunaverty, Argyll [4309], according to the Annals of Iona besieged in AD 712 (Alcock 1981, 157), and the cliff-girt Castle Rock of Edinburgh Castle [3713], where again a siege is noted for the year AD 638. Excavation on Edinburgh Rock has at least revealed evidence of Late Bronze Age and early medieval occupation, though any trace of earlier defences is entirely lost beneath the castle walls. On balance, Edinburgh Castle has been accepted as a Confirmed fort, but in the case of Dunnottar Castle there

remains a nagging doubt, which led Alcock to consider the neighbouring and unlikely promontory of Bowduns as a possible alternative. And yet the impregnable character of the conglomerate promontory beneath Dunnottar Castle, rivalled only on this stretch of coast by the tiny sea stack, presumably once a more extensive promontory, at nearby Dunnicaer [3111], renders it almost inconceivable that it was not the location of the sieges referred to in entries in the Annals of Ulster for the years AD 680 and 693 (Alcock 1981, 171-2; Alcock and Alcock 1992, 267). More recently evidence of a timberlaced defence dating from the 3rd-4th centuries AD has been recovered from Dunnicaer (Past Horizons 2015), but it would be surprising if the Dunnottar promontory had escaped occupation in the pre-Roman Iron Age; this, after all, is the premier location for a promontory fort anywhere along this coast. The inclusion of several other castles in the Unconfirmed category is more speculative, such as at Borve Castle, Sutherland [2809], and the Castle of Old Wick, Caithness [2827], where the character of both the promontories and the defences re-creates the form of other promontory sites identified as forts along the coastline of northern Scotland (cf Lamb 1980, 90-2). Another probable castle included under this morphological pretext is the earthwork overlooking the bridge over the River Esk at Gilknockie, Dumfriesshire [1122], and, for completeness, what is probably a late medieval stronghold known as Lady Lindsay’s Castle, Perthshire [3044]. Castle Qua, Lanarkshire [1568], had already been included in the Atlas database when fieldwork recognised traces of the abutments for a bridge crossing the ditch; its status was altered to Irreconcilable Issues.

This theme of medieval works occupying promontories that may be the sites of earlier promontory enclosures also runs through the Irish data in the Atlas, for example at Ballyoughteragh South, Kerry [1259], or Downmacpatrick, Cork [0901], this latter where a 15thcentury tower and curtain wall cut off a promontory identified as an earlier tribal stronghold. Reviewing the descriptions of all these Irish sites against satellite imagery, however, also suggests that the ‘promontory fort’ classification has been employed generously in both the Archaeological Survey of Ireland Database of the National Monuments Service and the Northern Ireland Sites and Monuments Record to include a number of sites that are more likely to be post-medieval stock or agricultural boundaries. A 17ha enclosure at Greenane on Bear Island, Cork [0851], serves as one example, while the 58ha enclosure on Innishark, Galway [1104], representing about a quarter of the surface area of this small island, is another. These Irish examples are marked Unconfirmed in the Atlas database, but in Scotland a conscious decision was taken to try to exclude the majority of such works, which are found widely on coastal headlands large and small, notably in

Halliday and Ian Ralston

Shetland and the Outer Hebrides. In some cases they have also previously been mistakenly identified as fortifications and have been included in the Atlas only to avoid confusion. Weinnia Ness, Shetland [4176], for example, was first reported as a fort by Raymond Lamb but later discounted from his synthesis (1980), and yet it still appears in Canmore – the online National Record of the Historic Environment of what is now Historic Environment Scotland – as a fort. Another ‘fort’ recorded at Lambigart, Shetland [4172], was included on a recent distribution map (Halliday and Ralston 2009, 466, fig 5), but a field visit revealed that the thick banks cutting off the promontory are no more than old dykes built of turf stripped from the neck. Likewise visits to a series of large promontory enclosures noted by coastal surveys in the Outer Hebrides showed that the majority were almost certainly agricultural, in some cases with a 19th-century drystone dyke roughly replicating the line of an earlier bank flanked by turfstripping scars (Halliday and Ralston 2013, 224-5). In most cases, the relationship of these boundary banks to the topography at the neck of a promontory is quite unlike that of defensive works, which almost invariably adopt the cliffs and scarps on the seaward or outer side of the neck to enhance the barrier. This sort of promontory enclosure is not entirely restricted to the Atlantic coast, and those at Strath Howe, Aberdeenshire [2984], and Elliot Water, Angus [3080], are possibly no more than post-medieval field boundaries.

Another group of sites that are more conventionally considered to be early medieval is a series of what are thought to be undocumented monastic sites, both large and small, mainly situated on coastal promontories and isolated sea stacks. In Shetland these include relatively large enclosures, notably at Blue Mull, Unst [3723; 8.2ha], but also including Outer [4195; 0.74ha] and Inner [4196, 4.4ha] Brough, Fetlar, and Brei Holm, Papa Stour [4197; 0.6ha], and the smaller stacks of Clett [4175], Burri Stacks, Culswick [4177], Kame of Isbister [4182], Aastack, Yell [4198], and Birrier of West Sandwick, Yell [4189]. The presence of small clustered rectangular structures on many such sites, best illustrated by Kame of Isbister and Birrier of West Sandwick, forms the basis for the monastic interpretation, but it is difficult to demonstrate conclusively that any of them is not an early medieval secular settlement, nor, if they are indeed monastic, that their origins did not lie in secular defended enclosures. All other forts in the Northern Isles exploit precipitous promontories and stacks, so it is not unreasonable to suggest that some of these enclosures that have been claimed as monastic were initially secular. The inaccessible Birrier of West Sandwick, for example, has a wall overlooking the razorback neck and though usually identified as monastic has been marked Confirmed in the database. Conversely the promontory enclosure on Burrier Head [4174], also on Shetland, which was first

identified as a possible promontory fort by Raymond Lamb (1980, 83) but appears to have a row of three rectangular structures midway along its top, might just as easily be monastic and has been marked Unconfirmed. The Landberg promontory fort on Fair Isle [2861] raises many of these issues, for the rectangular building visible within it (Hunter 1996, 89-93) was demonstrated by excavation to be a chapel and there was evidence of an earlier phase of occupation beneath it from which pottery comparable to that from brochs was recovered, along with moulds for copper alloy artefacts. An evaluation carried out on Brei Holm, Papa Stour [4197], recovered evidence of a complex sequence of occupation and two radiocarbon assays returned dates in the 5th7th centuries AD, rather earlier than the date suggested by the rectangular buildings on its summit.

This problem of disentangling secular and monastic enclosures is by no means unique to Shetland. The Brough of Deerness on Mainland, Orkney [2840], for example, with its chapel and rectangular and bowsided structures scattered across its interior, has long been regarded as a monastic site, but the supposed vallum monasterii is constructed as a major stonefaced rampart defending the now collapsed neck of the promontory, with its outer face set on the steep landward slope. Its status as a fort has therefore been marked as Confirmed. The Brough of Deerness is a relatively large enclosure of almost 1ha, but at the opposite end of the scale there are several smaller and heavily eroded fortified promontories on Orkney with traces of rectangular structures on them, such as The Brough, also on Mainland [2841], and Castle of Burwick on South Ronaldsay [2813]. The offshore stack known as The Brough of Burgh Head on Stronsay [2844] is another with a stout wall along its landward flank but where there may be some doubt about its original function. The northern coast of Caithness and Sutherland includes further examples, on the one hand with the enclosure of 2.25ha on St John’s Point, Caithness [2833], traditionally associated with the remains of a burial-ground and a chapel dedicated to St John, and on the other two minor promontories characterised by spectacular cliffs and the narrowest of razor-backed necks connecting them to the mainland: the first, Aodann Mhor, Sutherland [2782], is crowded with small rectangular structures, and less-certain traces of similar remains are also visible on the second, An Tornaidh Bhuidhe, Sutherland [2790]. Though unusual in this part of Scotland, St John’s Point meets all the criteria for a major fortification with a massive rampart and ditch, so much so that it is impossible to deny its Confirmed status. The other two are much more problematic, and though An Tornaidh Bhuidhe has a bank facing onto the only access and has been accepted also as Confirmed, in truth there is no way of knowing whether either is secular or monastic.

Aspects of the same problem re-surface in eastern and south-eastern Scotland, though these examples have all been accepted as forts, such as the Kirk Hill on St Abb’s Head, Berwickshire [4150]. Whether or not this is the site of the documented monastery of St Aebbe, the place-name Colodaesburg implies a fortified place and Alcock’s excavations uncovered a complex early medieval rampart sequence (Alcock et al. 1986). Elsewhere on this coast at Auldhame, East Lothian [3921], excavations on a promontory enclosure first identified from cropmarks have uncovered a chapel and a long cist cemetery. This has been interpreted as the remains of another Anglo-Saxon monastery, but there is nothing inherently in the character of the ditch, which was not bottomed during the recent excavations and is not closely dated, to demonstrate that its original construction was as a monastic enclosure (Crone et al. 2016, 129). Nor is it alone in the association of long cist burials with a promontory enclosure. In 1831 a long cist cemetery was discovered not far away at Castle Dykes, Dunglass Dean, Berwickshire [0486], and also occupies the site of a multivallate promontory fort, while other cists were said to have been found before 1853 on the neighbouring promontory fort at Castle Dykes, Bilsdean, East Lothian [0487]. Yet another promontory enclosure where cists occur is at Whiting Ness, Angus [3100], which was traditionally the site of a burialground and a chapel dedicated to St Ninian and marked as such by the Ordnance Survey.

Another group of Unconfirmed entries in the Atlas database relating to promontories and sea stacks worth drawing attention to is in the Outer Hebrides. In their case, the scope for confusion is not related to the use of such locations by early monastic communities, but rather as post-medieval strongholds. The small and now inaccessible Stac Dhomnuill Chaim at Mangursta, Lewis [2759], is thought to be the remains of a refuge constructed in the early 17th century by the Uig warrior, Donald Cam Macaulay, while Dun Eistean [2772] on the east coast of Lewis is traditionally a stronghold associated with the Morrisons since the 16th century (Burgess 2008, 60-2). The excavations by the Barrowmans at Dun Eistean found no evidence of occupation before the medieval period, but the possibility that this is also the site of an earlier fort cannot be discounted.

All the same issues arise at Dun Eorradail [2773], another large and inaccessible stack north of Dun Eistean, where there are traces of at least ten rectangular buildings and the possibilities for its use range from fort to early monastic community or post-medieval stronghold. On reflection, the same could be said of several other examples that have been accepted as Confirmed forts. Rudha Shilldinish near Stornoway on Lewis [2765], for example, carries a suite of large rectangular buildings which suggest a medieval or later date rather than a

prehistoric fort at least for the present configuration of the site. On Geirum Mor [2484], a cliff-bound islet of 1ha in the sound between Mingulay and Berneray at the extreme southern end of the chain of islands, a wall blocks the only access at the north-east end and there is a series of rectangular buildings on its summit. Morphologically this is a fort, but whether prehistoric, early medieval or post-medieval cannot be determined without excavation, and it could yet prove to be monastic. Biruaslum [2483], a tidal islet off the west coast of Vatersay, which extends to 9.8ha – the second largest such site in the Outer Hebrides – poses a similar concern. It is defended by a thick wall facing the main island; its position recalls the monastic site on the Brough of Birsay in Orkney, though at 18ha the latter island is rather larger and there is no evidence of a perimeter wall overlooking the tidal isthmus linking it to the mainland.

Another problem found along the Atlantic coasts relates to the interpretation of the outworks of brochs and duns, or Atlantic Roundhouses as they are commonly called, themselves excluded from consideration in the Atlas database on size grounds. The very term outwork assigns primacy to the Atlantic Roundhouse, but in some cases the supposed outworks may have been the primary fortifications, with the Atlantic Roundhouse subsequently set within them. This is a sequence familiar in southern Scotland at Edinshall [4069] and Torwoodlee [3542], and the excavator of the broch at Crosskirk, Caithness [4348], Horace Fairhurst, postulated that the broch there succeeded an earlier promontory fort (1984). No stratigraphic evidence was advanced in support of his case, which largely rests on two radiocarbon dates obtained in the 1970s that purport to predate the assumed chronology of the broch supplied by sherds of Samian ware and late Roman pottery (see discussion by MacKie 2007, 407-26). More recent excavations at Nybster, Caithness [2820], were unable to establish the stratigraphic relationship between the wall across the neck of the promontory and the broch, and radiocarbon dates for samples underlying the wall indicate a phase of Late Bronze Age activity rather than the date of the outwork itself. Four out of nine Unconfirmed promontory works in Argyll fall into this category,4 while for Sutherland and Caithness the figure is 6 out of 16,5 in Orkney 6 out of 10,6 and in Shetland 3 out of 17.7 This uncertainty of the relationship between Atlantic Roundhouses and their supposed outworks is

4 Dun Bhronaig [2444], Dun Haunn [2503], Dun Aorain [2546] and Dun Chruban [2550]

5 An Dun, Clachtoll [2793], Altanduin [2806], Poll Gorm [2810], Scarfskerry [2816], Nybster [2820] and Crosskirk [4348]

6 Weems Castle [2811], Yesnaby, Broch of Borwick [2845], Midhowe [2846], Riggin of Kami [2847], Lamb Head [2848] and Broch of Burrian [2849].

7 [Broch of Aithsetter [4187], Noss Sound [4190] and Sna Broch [4260].

Halliday and Ian Ralston

not limited to those on coastal promontories and recurs amongst those in other locations inland.

The rest of the sites that make up the Unconfirmed promontory enclosures break down into several types of record. Twelve are long-recorded sites that have been so heavily degraded that there is insufficient information to judge their true character with any confidence.8 Twelve others turn on the interpretation of cropmarks, either because a ditch is relatively narrow for a defensive work or the definition of the cropmarks is too diffuse;9 and finally some are simply miscellaneous earthworks on promontories, most of them of uncertain date or purpose. Most spectacular of these is the multivallate earthwork isolating 54ha on the Mull of Galloway [0201], which despite excavation (Strachan 2000) remains undated; it is either the largest fort in any setting in the whole of Scotland or an extraordinary enclosure with some other function that finds its only morphological parallels with several equally large promontory works in southern Ireland, such as the 83.5ha enclosure on the headland at Ballynacarriga, Cork [1970]. Others falling into this category in southern Scotland are inconsequential by comparison. Haly Jo, Lumsdaine, Berwickshire [4092], for example, a slight enclosure on a coastal cliff is probably no more than a small settlement, though others, such as Drummoral, Wigtownshire [0223], appear defensive, here with rock-cut ditches but no evidence of an accompanying rampart. Elsewhere there are: the tiny stone-walled enclosure (claimed as unfinished: MacKie 2016) overlying the broch at Leckie, Stirlingshire [1471]; the enclosure beneath a later medieval burial-ground on Innis Bhuidhe, an island set in the river at Killin, Perthshire [2609]; the slight boundary, undated despite limited excavation, enclosing two rectangular buildings on a low promontory projecting into Loch Kinord, Aberdeenshire [3075]; the precipitous promontory known as Tronach Castle, Banffshire [2944], where there are no visible defences; and Dun Earn, Morayshire [2918], where a ditch 4m-5m in breadth but with little trace of a rampart cuts off about 2.5ha on an inland promontory.

In some cases a visit would solve issues raised by the existing records, as for example at Lambigart discussed above, or Hynish, Tiree, Argyll [2486], where fieldwork (by SH) since the completion of the database clearly demonstrates that this is not a promontory fort as such, though there are traces of a fortified enclosure taking

8 Grennan, Grennan Point [0180], Killantrae Bridge [0217], Port o’ Warren [0311], Gunnerton Crag Camps [0520], Ebb’s Nook [0920], Salter’s Nick [1977], The Heugh [2038], Machrihanish [2222], Keir, Easter Tarr [2617], Firbush Point [2619], Coldstream [4079] and Siccar Point [4115]

9 Clanyard Bay [0196], Leffnoll [0342], Loch Quien [1152], Rousland [1838], Wester Tullynedie [3046], West Lindsaylands [3230], Milton Mill [3782], Bara [3859], Nether Hailes [3883], Lumsdaine Dean [4098], Coveyheugh [4101] and Ayton [4142].

in the top of the headland. The character of several others could be resolved likewise, probably including four relegated to the status of Irreconciled Issues. Three of these, Court Hill, High Skeog, Wigtownshire [0227], and An Fang, Craignish Point [2449] and Creag a’ Chaisteal, Stillaig [2472], Argyll, are where the observations recorded by the archaeologists who first visited the sites have been disputed by subsequent OS surveyors, while the fourth is a site reported in 1993 on the shores of Loch an Iasgaich, Skye [2743], which appears an unlikely candidate to be a fort on the grounds of either its topographical position or the slightness of the supposed defences. In other cases, the only resolution is by invasive evaluation, though as the experience of the Mull of Galloway proved, there is no guarantee of success. Nevertheless, clarifying the date of the Mull of Galloway is evidently vitally important for the interpretation of the Iron Age landscape of south-western Scotland, and the same might be said locally of Dun Evan in Morayshire if this proved to be a fortification of Iron Age date.

Confirmed Promontory Forts

This rehearsal of the range of promontory works found in Scotland and the problems of applying morphological classifications to identify those that are at least potentially prehistoric and early medieval fortifications serves to clarify the definitions that lie behind those that are attributed the status of Confirmed forts. In short, they comprise fortified enclosures where thick walls or earthen ramparts and ditches bar access on one side, usually the easiest line of approach, and the rest of the perimeter is apparently defined by little more than cliff-edges or steep scarps. In this definition the character of most of these forts is synonymous with the description of the topography on which they stand. Originating from its Latin root to describe a raised headland jutting out into the sea, it has been adapted more generally to describe other projecting landforms and raised spits of ground, and in archaeological terminology further extended to embrace inland enclosures set on interfluves and thus often exploiting angles formed in escarpments along streams and rivers, usually where a tributary has cut down at its confluence with the main flow. They are thus largely defined by natural declivities on at least two sides, often creating a roughly triangular plan in which the artificial defences form the third side.

This basic format, however, has also led to the term being applied to the plans of forts that are in hilltop positions, or on the ends of ridges, where the defences were apparently constructed only on one side, complemented by abrupt or at least steep descents elsewhere. Scottish examples of these tend to be located in prominent elevated positions, such as Dumglow, Kinross [3203], Ben Effrey, Perthshire [2648],

Craik Moor, Roxburghshire [3453], An Sgurr on the island of Eigg [2527] or Sithean Buidhe, Argyll [2292]. All told, there are only thirteen in this type of setting in Scotland and they are better analysed with other hilltop forts.10 Much more problematical in this sort of morphological classification driven by topographical descriptors is the exclusion of scarp-edge forts where the circuit was evidently left incomplete along one side and the interior simply backs onto the lip of a cliff or escarpment, and where the distinction between these and some promontory forts is one of degree. This issue is discussed further below under the heading of Scarp-edge Forts. At least 97 other Confirmed forts share this feature, eight of them in coastal locations, and their entries in the Atlas database are variously labelled Contour Fort (40), Hillslope Fort (12), and Level Terrain Fort (45). While these terms serve as topographic descriptors, it is unwise to apply any of them too prescriptively in terms of their archaeological significance.

Whereas Lamb’s schematic map suggested that Scottish promontory forts formed discrete concentrations in Shetland, Orkney, Caithness, Angus and Galloway (1980, 5, fig 1), the Atlas data reveal that they are much more widespread and occur along virtually every coastline where there is some form of normally rocky escarpment or cliff-line. Furthermore, this same defensive format is equally widespread in inland locations. Nevertheless, the new map hides some general trends. Reference to the regional and county table (Fig. 1) shows that the proportions of promontory forts to other forts alter from region to region. The largest single regional group of promontory forts is in the western and northern Highlands, which includes the whole of the mainland Atlantic coast from Argyll northwards, and the Inner Hebrides and Outer Hebrides. Across this region as a whole 159 of the 370 Confirmed forts are promontory forts, representing 43%, and 32 of them occur inland. The pattern within this region, however, varies widely. In the three northernmost counties of Ross-shire, Sutherland and Caithness, where there are relatively few forts, the percentages rise to 59%, 64% and 69% respectively. Locally within them, some of the figures are even higher. In the Outer Hebrides, for example, which were formerly split between Rossshire and Inverness-shire, of the 26 Confirmed forts, all bar 3 are coastal promontories or tidal islands (88%); the exceptions are all islands in inland lochs. In Argyll, too, where the overall number of promontory forts forms 38% of all Confirmed forts there, no fewer than 50 of the 68 promontory forts occur on islands

10 The full list comprises Dumyat [1593], Sithean Buidhe [2292], An Sgurr [2527], Skirley Craig [2633], Ben Effrey [2648], Dun Vallerain [2715], Phoineas Hill [2887], Dumglow [3203], Little Trowpenny [3378], Craik Moor [3453], Earn’s Heugh NW [4094], St Abb’s Head [4150] and An Dun, Cornhill Wood [4381].

in the Inner Hebrides. This is perhaps a reflection of the longer hard coastlines in relation to the surface areas of the islands and probably aspects of their geology too. Islay (about 600 sq km and 165 km of coast), for example, has 38 forts all told, of which no fewer than 26 are promontory works (68%), and 24 of them coastal, whereas Mull (about 880 sq km and with 250 km of coast) has equivalent figures of 22, 10 (45%) and 10. Skye (1650 sq km and 650 km of coast), the northernmost of the Inner Hebrides and formerly part of Inverness-shire, has figures of 31, 15 (48%) and 12 respectively. It is worth noting in this context that the 9 Confirmed forts on Orkney, and 15 on Shetland, are all promontory forts and are all coastal.

Other regions show similar patterns of variation within them. Thus, while promontory forts make up 34 % of all forts in the South-West, in Wigtownshire, again with its relatively long coastline, the figure rises to 65%. The lowest regional percentage is in the Greater Tyne-Forth region, where it is no more than 11%, and here exceptionally 87 of the 98 promontory forts occur inland. In the hillier inland landscapes of Peeblesshire, where forts typically stand on spurs along the sides of valleys, the figure is only 1%, representing a single fort at Castlecraig [3636]. In Roxburghshire and neighbouring Northumberland only 7% of Confirmed forts are on promontories, but for Berwickshire, with its long predominantly rocky coastline, it rises to 25%. Without the 8 coastal examples known there, however, the percentage would be no more than 18%, a figure more akin to the 17% in Dumfriesshire, or 15% in Lanarkshire.

In passing, it is worth taking brief note of the distribution of Unconfirmed promontory works, which are also recorded in Fig. 1. At a regional scale, these form between 17% of all promontory works in Greater Tyne-Forth, but only 2% in comparison to the total number of forts in the region. The equivalent figures for the South-West are 13% and 5% respectively, in Central Scotland 17% and 4%, and in the North-East 15% and 7%. In the northern and western Highlands, these figures appear to rise overall to 20% and 10% respectively, but this masks wide regional differences between Argyll at 14% and 6%, and Caithness at 53% and 76%. The Northern Isles calculations are even more extreme, with 54% and 116%. A significant proportion of these are the supposed outworks of brochs (supra). In themselves, these figures are of little significance, but they confirm the general pattern that the proportions of promontory forts to other forts not only increases on the islands of the Atlantic seaboard, but also more generally northwards through the mainland, and that whereas the alteration of the status of a few of the Unconfirmed category in the south makes little difference to the overall proportions of promontory forts to other types, in the far north it exaggerates the contrast already observed still further.

Stratford Halliday and Ian Ralston

Figure 1. Table of promontory enclosures by region and county. Percentages of Confirmed Promontory Forts are calculated as a ratio of All Confirmed Forts regionally and locally. Sizes column totals include multiple measurements from individual sites; for six others there is no data.

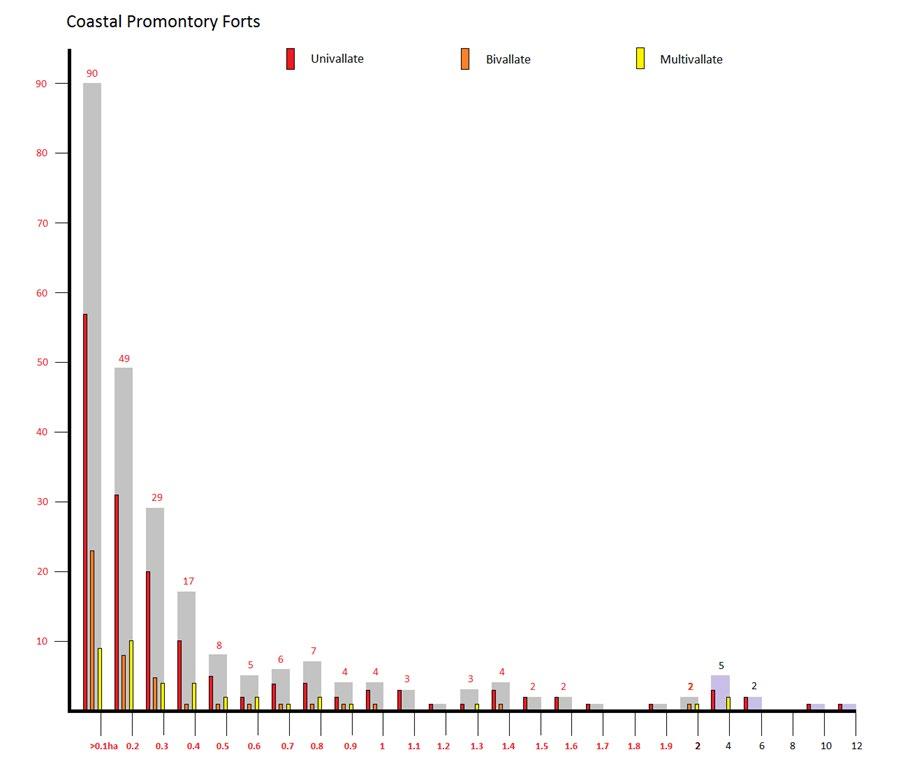

The 399 that are Confirmed include 12 coastal and 17 inland forts with eccentric or wide-spaced lines of ramparts, taken here to represent separate structural arrangements probably belonging to successive phases of construction. In another six cases no size data are available. This provides a total of 430 measured internal sizes, which are plotted on a single graph (Fig. 2) in increments of 0.1ha up to 2ha, and 2ha increments thereafter, the latter in orange. This shows that almost half (48%) fall below 0.2ha. The profile of the graph falls away steeply from 119 (28%) examples below 0.1ha to about 0.7ha, sites below this threshold representing 87% of all promontory forts. In all, 24 lie between 1ha

and 2ha, and 13 are over 2ha, the largest being two coastal forts on Vatersay and Mingulay in the Outer Hebrides enclosing 9.8ha and 10.4ha respectively [2483, 2480].

By breaking this graph (Fig. 2) down into the two datasets, however, different patterns can be detected between those in coastal and inland positions. The profile of the coastal graph of 247 sizes from 236 forts (Fig. 3) falls away much more steeply to about 0.4ha, and there are almost twice as many sizes below 0.1ha as there are in the 0.1ha-0.2ha increment. A total of 185 fall in the four increment classes below 0.4ha, representing

Figure 2. The Confirmed promontory forts of Scotland by enclosed area. Steps are 0.1 ha to 2ha, thereafter by 2ha divisions. N=430.

Stratford Halliday and Ian Ralston

Figure 3. The Confirmed coastal promontory forts of Scotland by enclosed area. Steps are 0.1 ha to 2ha, thereafter by 2ha divisions. N=247 from 236 sites.

4. The Confirmed inland promontory forts of Scotland by enclosed area. Steps are 0.1 ha to 2ha, thereafter by 2ha divisions. N=183 from 163 sites.

Figure

75% of this group. In contrast, the inland graph (Fig. 4) of 183 sizes from 163 forts does not show this peak in the smallest size band (i.e. below 0.1ha), and falls steadily from a high point at 0.1ha-0.2ha down to 0.7ha, beyond which a thin scatter extends to four larger enclosures over 2ha in extent, the largest of them being the hilltop fort of Sithean Buidhe, Argyll [2292], at 7ha. The 168 falling below 0.7ha however represent 92% of this group (compared with 83% for the equivalent range in the coastal group).

Two main areas of difference can be identified in these patterns, the first relating to the incidence of very small examples, and the second to the forts between 0.2ha and 0.4ha. In respect to the first, some 56% of coastal examples (Fig. 3) fall below 0.2ha, compared with 37% of inland examples. The significance of this observation is uncertain. Possibly the high incidence of diminutive coastal sites is little more than an impact of differential erosion. The exposed Atlantic coasts, for example, are undoubtedly subjected to far more extreme erosion than the majority of inland promontories, but the incidence of small inland examples perhaps indicates that erosion has not been the unique determining factor in the overall pattern of relatively small interiors.

The second difference is more clearly defined, and it is that a greater proportion of the slightly larger band of promontory forts between 0.2ha and 0.5ha occur in inland locations. The relative percentages are 21% of the coastal group, and 43% of the inland group. Unsurprisingly, 48 out of the 78 forts in this band in the latter come from Greater Tyne-Forth, and the general profile of the inland graph is consistent with the wider pattern of internal sizes in this region.

Character of Promontory Defence Works

Of the 236 Confirmed coastal promontory forts, at least 246 separate defensive schemes can be identified; size data are also available for all bar four. These schemes can be broken down into 158 univallate defences (64%), 50 bivallate (20%) and 38 cases of multivallation (16 %), based on the maximum number of ramparts occurring in a single sector of the defences. These percentages can be compared with the overall figures for Confirmed Scottish forts of 37% univallate, 37% bivallate and 26% multivallate. Evidently the figure of 64% for promontory forts is well above the general proportion of univallate forts in Scotland, while the combined bivallate and multivallate percentage of 36% is well below the national trend of 63% for all Scottish forts.

The pattern of vallation is displayed against size on the graph (Fig. 5), which also shows the ghost of the coastal promontory fort sizes. What may be skewing the percentages is revealed in the pattern of sizes, since

no fewer than 88 of the very smallest forts under 0.2ha have only a single line of defence, be it a stone wall or a rampart and ditch. Even allowing for heavy erosion of promontories, it would appear that the function of the majority of these small enclosures could be serviced by a relatively modest investment in artificial works. Nevertheless, there are also 31 bivallate examples below 0.2ha, and their graph displays a similar profile, while 19 multivallate works occur in the size bands below 0.2ha. The profile of bivallate examples in Fig. 5 is altogether flatter, petering out with works below 1ha. Above this size the only possible bivallate promontory forts are Meall Lamalum on Colonsay, Argyll [2162], though with its wide-spaced walls this could also be treated as two successive univallate works respectively enclosing 1.3ha and 1.6ha (cf Yesnaby, Brough of Bigging, Orkney [2837]), and Sumburgh Head in Shetland [4184], where the records of the character of the defences are not particularly satisfactory.

The larger multivallate works are less contentious. They comprise Dun a’ Bheirgh (1.2ha) on the rocky Rudha na Berie [2762], a storm-lashed promontory on the north-west coast of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, and the remarkable Burghead, Moray [2925], where at its maximum extent the substantially-demolished outer ramparts cut off some 3.2ha on this sandstone headland. With these exceptions, the rest of the larger Confirmed promontory forts are univallate, 14 falling between 1ha and 2ha, these including the outermost rampart across Isle Head on the Isle of Whithorn, Wigtownshire [0226], the earliest, outer, defences at Cullykhan, Banffshire [2982], both walls across Yesnaby, Brough of Bigging, Orkney [2837] and Mas na Buaile, Sutherland [2784]. In the Outer Hebrides univallate sites include a’ Bheirghe, Port of Ness [2771] on Lewis, and the defended stack of Geirum Mor [2484] in the sound between Mingulay and Berneray, as well as a series of coastal promontories on Islay in Argyll, namely Dun Mor Ghil on the Oa [2071], and along the north-west coast of the Rhinns, four such promontory forts: Beinn a’ Chaisteal [2128], Allt nan Ba [2120], Am Burg Coul [2067], and Lossit Point, Dun na Faing [2062].

There are another seven examples of coastal promontories over 2ha to consider. In Shetland, Hog Sound [4191], where the interior has been severed from its multivallate defences by marine erosion to form an island still of 2ha; on the north coast of mainland Scotland, St John’s Point, Caithness [2833], and a rocky hammerhead in excess of 4ha on Eilean nan Caorach, Sutherland [2779]; on the Rhinns of Islay, Dun Bheolain [2117]; and in the Outer Hebrides the spectacular hammerhead of Gob a’ Chuthail on Lewis [2761], the 9.8ha promontory of Biruaslum [2483] on the west coast of Vatersay (supra), and the precipitous 10.4ha Dun Mhiughlaigh on Mingulay [2480], where a short wall little more than 20m in length at the neck comprises

Figure 5. Univallate, bivallate and multivallate coastal promontory forts mapped against the ghost of the total population of Confirmed coastal promontory forts in Scotland

the sole artificial defence of an otherwise inaccessible promontory with cliffs up to 145m high jutting into the Atlantic (Halliday and Ralston 2013, fig. 3). It should also be remembered that the 54ha enclosure on the Mull of Galloway [0201] is multivallate. This last apart, it is striking how, with relatively few exceptions, these large coastal promontory forts are found in the North-West and far North, many of them on islands, and many in places that are spectacular in their own rights, fringed by sheer cliffs and looking out across open seascapes.

The positioning of some of the smaller works is certainly no less spectacular in terms of the adjacent cliff scenery, irrespective of the character of the artificial defences. Dun Athad, on the Oa peninsula of Islay [1877], which was evidently occupied in the medieval period but where a single piece of vitrified stone has been recovered from the wall above the narrow and challenging neck, soars sheer above the foreshore about 100m below. Unsurprisingly, the choice of materials for

the construction of the defences of these sites is largely driven by the adjacent geology. Ditches are relatively uncommon along the Atlantic coasts from Kintyre to Cape Wrath, and elsewhere are mainly found where there is a covering of till or the rock is relatively soft and easily quarried. Thus 35 out of 50 promontory forts in Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire are equipped with ditches, whereas in Argyll it is only 1 out of 68. Here the majority of defences comprise walls, some of which have evidently been timber-laced and burnt, resulting in vitrifaction. There is no particular pattern to the sizes of the forts where vitrifaction occurs, and the examples qualifying as promontory forts include the diminutive enclosures of no more than 0.07ha defended by three walls at Dun nan Gall [2169] and Trudernish Point [2170] on Islay, and the 0.09ha site of An Dun, on the mainland at Gairloch [2727]. In north-eastern Scotland, the early medieval timber-framed – and very locally vitrified – rampart at Green Castle, Portknockie [2945], cuts off 0.28ha, but the larger timber-laced ramparts

Halliday and Ian Ralston

at Burghead [2925] and Cullykhan [2982] are likely to have been designed to form complete enclosures that happen to exploit the natural strength of promontories and should perhaps be discounted from this reckoning.

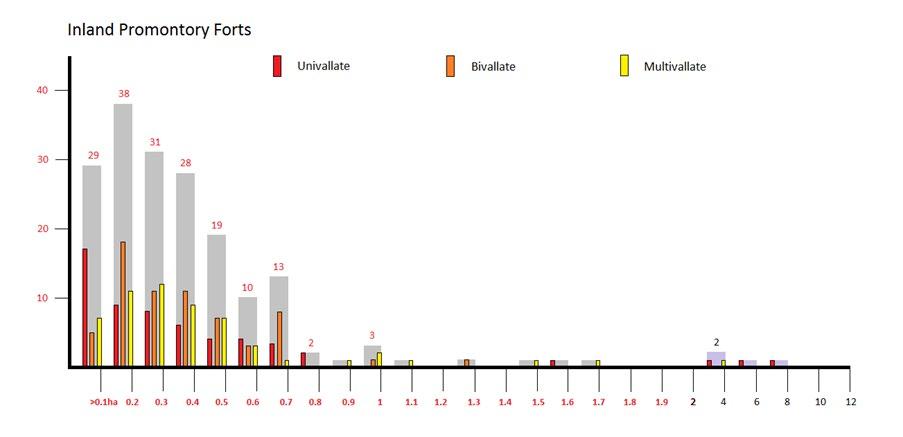

As already observed, the general size graph for inland promontory forts (Fig. 6) is rather different to that for coastal promontories, but the pattern for univallate enclosures is similar. This displays a peak of 17 examples below 0.1ha that upsets the general trend of the inland graph, which shows a gentler gradient declining from the 0.1ha-0.2ha increment down to 0.8ha. Bivallate enclosures, however, climb from the smallest size category to the biggest cohort of 18 at 0.1ha-0.2ha, descending relatively evenly to three at 0.5ha-0.6ha before a spike of eight at 0.6ha-0.7ha, while the multivallate systems peak with twelve cases in the 0.2ha0.3ha size band before descending to only one at 0.6ha0.7ha. Notably there is a dearth of univallate systems enclosing between 0.8ha and 2ha, the exception being a cropmark recorded at Hatchednize, Berwickshire [4077], but three out of the four sites over 2ha are univallate –White Isle, Dumfriesshire [0302], An Sgurr, Eigg [2527], and Sithean Buidhe, Argyll – the latter two being conspicuous hilltop enclosures. The fourth site over 2ha in extent is the multivallate Double Dykes, Sodom Hill, Lanarkshire [0841], set between the Cander Water and Avon Water valleys. The seven other promontory works with more than one rampart and enclosing between 0.8ha and 2ha are mainly cropmarks scattered across south-east and north-east Scotland, but one, unusually for a cropmarked site, is at Bridgend, Islay, Argyll [2155]. This set also includes the multivallate fort of 1.6ha on the summit of Dumglow, Kinross [3203], the commanding northward-facing summit of 379m OD towards the western end of the Cleish Hills.

Internal Features

Of the 236 Confirmed coastal promontory forts, 148 are entirely featureless, and of the rest it is reasonable to suppose that many of the structures that are visible, as often as not rectangular rather than circular, probably relate to later occupations. Some of the rectangular buildings recorded on coastal promontory forts are substantial structures, at least four being the remains of churches or chapels – Brough of Deerness, Orkney [2840], St John’s Point, Caithness [2833], Landberg, Fair Isle [2861], and St Abb’s Head, Berwickshire [4150]. Others include buildings associated with later castles –Castle Feather, Wigtownshire [0232], Dun Athad, Islay, Argyll [1877], and possibly Rudha Shilldinish, Lewis [2765] and Dun na Muirgheidh, Mull, Argyll [2511]. The Brough of Deerness is also latterly a monastic site with numerous traces of rectangular buildings within the interior, and monastic use possibly accounts too for the rows of buildings visible on Birrier of West Sandwick, Yell, Shetland [4189], Castle of Burwick on South Ronaldsay, Orkney [2813], and An Tornaidh Bhuidhe, Sutherland [2790], which have all been accepted for the Atlas as Confirmed promontory forts. The problems of separating the remains of secular fortifications from monastic sites occupying precipitous locations that were almost impregnable before the addition of any artificial works has already been aired.

Elsewhere, some of the other rectangular buildings visible within the defences on coastal and inland promontory forts are probably the remains of medieval or post-medieval settlements, though without excavation such remains cannot be dated with any certainty. In Greater Tyne-Forth examples are Ogle Linn, Dumfriesshire [3206], and Wrunklaw [4039],

Figure 6. Univallate, bivallate and multivallate inland promontory forts mapped against the ghost of the total population of Confirmed inland promontory forts (cf Fig. 4) in Scotland

Stratford Halliday and Ian Ralston

the latter set on a spur deep into the Lammermuir Hills in Berwickshire and one of the few where map evidence shows that some of the overlying buildings and yards were still occupied in the late 18th century. Nevertheless, in Argyll the building recorded on Am Burg, Coul, Islay [2067], appears to have been long deserted by the time of a visit by Thomas Pennant in July 1772, while the depiction on the 1st edition of the OS 6-inch map of Dun Mhic Laitheann [2673] in the Outer Hebrides, on a small tidal islet off Groatay, North Uist, indicates the buildings there were abandoned by the late 19th century.

In at least 14 other cases footings of smaller buildings, huts and pens can be seen on coastal promontories. Such structures appear widely on all types of fort, particularly in the North and West Highland region. Generally they are thought to be the remains of bothies associated with post-medieval grazing and pasturage, rather than contemporary buildings within the defences. This interpretation is to some extent sustained by at least five instances where the structures appear to butt against, or overlie, the defences of promontory forts – Eilean nan Caorach, Sutherland [2779], Dun Channa, Small Isles [2688], Dun Briste, Berneray [2481], Caisteal Odair, North Uist [2669], and Ardmenish, An Dunan, Jura [2185]. Those on Eilean nan Caorach are typical of local shielings, as are those overlying the inland promontory forts at Annait, Bay River, on Skye [2692], and Dunmore, Angus [3067]. At Port Ellen, The Ard, on Islay, Argyll [2177], little more than three shallow oval or sub-rectangular hollows mark the probable positions of structures, but whether these are simply the remains of heavily degraded post-medieval bothies, or much older buildings is quite unknown. Traces of drystone sub-rectangular structures at Gob Eirer on Lewis [2760] are presented by the excavators (Nesbitt et al. 2011) as Late Bronze Age / Iron Age in date and associated with the construction of a wall across the neck of the promontory, but the contexts of the radiocarbon dates, centred on the 9th – 4th centuries BC, are not supplied and the chronological sequence here is most uncertain. In North-east Scotland, however, on the southern shore of the Moray Firth, the rectangular building excavated at Green Castle, Portknockie, [2945], was set parallel to the early medieval timber-framed rampart and was probably broadly contemporary with it; Gordon Noble’s current field project is identifying further instances of first millennium AD rectilinear architecture within Burghead, Moray [2925] (Anon 2017).

The distribution of visible traces of round-houses within promontory forts follows the general pattern for all forts in Scotland. In the Greater Tyne-Forth region the complex hilltop fort on Craik Moor, Roxburghshire [3453], has traces of ring-ditch and ring-groove roundhouses, as does the newly identified fort at Kirktonhill,

Berwickshire [3947], while the stone-founded hutcircles at Earn’s Heugh, Berwickshire [4094], almost certainly relate to a Roman Iron Age reoccupation, a common sequence in neighbouring Northumberland and the eastern Borders. In Dumfriesshire the platforms visible within Auchencat Burn [3213] may be contemporary with the twin ramparts with a medial ditch, but the stone-founded hut-circles at Dalmakethar [1015] are most unusual in this county and their relationship to the defences is thus uncertain. Equally unusual for its district is the hut-circle at Mull Glen, West Tarbert, Wigtownshire [0200], but not far away on The Machars at Carghidown Castle [0229] one of two scooped platforms within the interior of a small univallate work was excavated to reveal a complex sequence of round-houses probably dating from the late 1st millennium BC (Toolis 2007). Only one other Wigtownshire promontory fort has surface traces of round-houses within its interior – Dinnans [0235]. The interiors of a series of other forts on the coastal edge around the Rhinns of Galloway comprise little more than bare rock, and it is notable that the tiny promontory at Dunorroch, West Cairngaan, Wigtownshire [0199], barely has any occupiable space amongst the jagged outcrops behind the line of its single wall, so much so that it seems unlikely that this curious spot tucked away at the foot of the coastal cliffs was ever intended for permanent occupation. The excavator of Carghidown Castle suggested that the round-houses there had been occupied but fleetingly (Toolis 2007) and the site may have served as no more than a refuge.

A similar picture emerges northwards up the Atlantic coast of Argyll and the Inner and Outer Hebrides. Traces of contemporary structures are unusual in any fort here, and there are no more than eight coastal promontory forts containing platforms or stony ringbanks – in the Inner Hebrides, Dun Uragaig [2161] and Meall Lamulum [2162] on Colonsay, and Eilean na Ba [2487] and Nun nan Gall [2488] on Tiree; in the Small Isles, Shellesder on Rum [2695] and Poll Duchaill on Eigg [2524]; and in the Outer Hebrides Gob a Chuthail [2761] and Creag Dubh [2770] on Lewis. In addition there are two platforms in Sithean Buidhe, Argyll [2292], though, like Craik Moor, this is best categorized as an inland hilltop fort. With the exception of Poll Duchaill, which contains about six circular platforms, most of the rest are either ring-banks or, in the cases of Dun nan Gall and Creag Dubh, oval and circular hollows with traces of stonework around their edges, a description that also recalls the structures at The Ard, on Islay, Argyll [2177]. Elsewhere there is a clear mismatch between the visibility of internal structures and the size of the fort. The single ring-bank at Gob a Chuthail, for example, lies within an isolated precipitous headland extending to about 2ha with a huge and spectacular bight eroded into its western flank. The row of three

conjoined hut-circles at Meall Lamulum appears equally disproportionate to its interior of at least 1.3ha, while at Dun Uragaig the greater part of the interior of 0.8ha is bare rock. At this latter, there are four or five structures built immediately behind the wall, though whether they are contemporary with or butted against it is unclear. At Shellesder, however, a fort of 0.3ha, one of the three possible hut-circles overlies the defences and with numerous shieling huts also in the vicinity the antiquity of these structures cannot be guaranteed.

Scarp-edge Forts

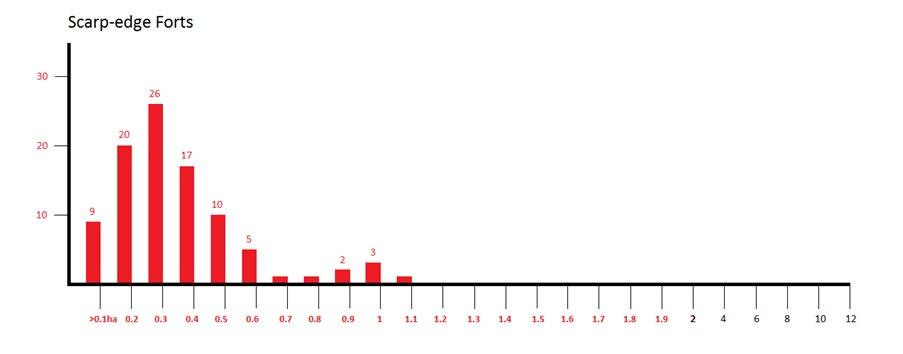

Scarp-edge forts, where one sector of the circuit is completed by the lip of a natural escarpment or cliff, share many similarities with promontory forts. As observed already, for some it is simply a matter of degree as to which category they have been attributed. The two forts on Earn’s Heugh, Berwickshire [4094, 4095], scene of one of the first of Gordon Childe’s excavations of Scotland’s later prehistory (Childe and Forde 1932), have been classified in the Atlas as promontory forts, but they might just as easily be described as scarp-edge forts, and while the south-eastern example cuts off an angle formed where a gully forms a nick in the cliff-edge on the south-east, the defences of the north-western enclosure effectively contour around a hilltop position backing onto the merest stub of a promontory on the north-east. On the other hand, the fort on Dunman, Wigtownshire [0177], a hillock backing onto the coastal cliffs of the Rhinns of Galloway, where a single rampart has been drawn around three sides, has no claim to be a promontory topographically, yet on its southwest flank the interior opens onto a rocky escarpment falling away to the sea in much the same way as any other promontory fort. In essence, promontory forts and scarp-edge forts represent a continuum extending from D-shaped enclosures backing onto cliff edges and escarpments, such as Sron Uamha, Argyll [2198], overlooking the North Channel at the southern end of Kintyre, or Lour, Peeblesshire [3569], through relatively shallow projections from a cliff-line seen at the cropmarked multivallate Barns Mill, Fife [3172], or the broad triangle of ground at Aytonlaw West, Berwickshire [4133], to narrow precipitous fingers with tightly constricted necks, such as Skirza Head, Caithness [2819].

To generalise about the character of this continuum, it extends from locations where the whole of the interior of an enclosure lies in front of, and thus landward of, the general line of the cliff-edge, to those where the whole of the interior lies beyond – often seaward of –the cliff-edge. The latter are clearly more isolated in a physical sense, and indeed require less investment in the construction of their defences, but whether this is any more than a pragmatic approach to the economy of construction of a fortification or translates into

wider cultural or functional differences is difficult to determine. Nevertheless, such a pragmatic approach to construction does seem likely for most of the 40 scarp-edge forts that have been also labelled contour forts, including those already cited on Earn’s Heugh or Dunman. In these cases the absence of any visible rampart around a side with a particularly steep slope is merely an extension of the same reasoning that led to the construction of two or three outer lines on gentler slopes elsewhere, either because of the greater status accrued by being more visible from the easiest lines of approach, or because tactically these sectors represented the weaker flanks.

Excluding this subset of contour forts leaves 57 cases where the distinction between a cliff-edge or promontory location is more blurred, representing 59% of those with incomplete circuits in scarp-edge positions identified in the Atlas database.11 No more than two of these are in coastal locations – Barsalloch Point, Wigtownshire [0219], and Kilspindie Golf Course, East Lothian [3820] – and the rest are located inland. Furthermore, no fewer than 43 of the 57 are in the Greater Tyne-Forth region, contrasting with four in the South-West, six in the Central region (with another three in neighbouring Angus) and only a single example – Balmachree [2903] just east of Inverness – in northern Scotland. Overwhelmingly, these forts are a feature of south-eastern Scotland, occurring within the area with the densest concentration of forts and other enclosures in the whole country. Broadly speaking, the graph of the 55 sites with measurable sizes (Fig. 8) is an extension of that described in the inland promontory forts. What is perhaps more surprising is that, including the two for which there is no size data, no more than eleven are univallate, and that bivallate (29) and multivallate (17) defences make up 81% of this subset; this is significantly greater than the national figure of 63% in these two categories for all forts in Scotland. The univallate examples are concentrated at 0.1ha-0.3ha in the size range, whereas an admixture of univallate and bivallate forts include the rest of the range up to 1.1ha. The largest is the multivallate cropmark above the River Tyne at East Linton, East Lothian [3870], where the defences also overlay an earlier palisaded line. By way of comparison, the 40 contour forts of the overall scarpedge group break down into 13 univallate, 15 bivallate and 12 multivallate, and the combined percentage for the bivallate and multivallate examples is 68%, quite close to the overall figure for Scotland.

11 A search of the Atlas will reveal a total of 132 Confirmed forts in scarp-edge positions, but 16 of these are also annotated as coastal and inland promontories and are included in the analysis of promontory forts, and another 19 have complete circuits of artificial defences and are therefore also discounted for the purposes of this discussion. This reduces the total of what are termed here ‘scarp-edge forts’ to 97; 40 of these are also labelled contour forts, and of the remaining 57 no measurable sizes are available for two (see Fig. 8 and Map 2)

Halliday and Ian Ralston

Stratford

Map 2. The distribution of scarp-edge forts in Scotland (N = 97) as defined on p. 15

Figure 7. The Confirmed scarp-edge forts by enclosed area, including 40 also identified as contour forts. N=95.

Figure 8. Subset of those univallate, bivallate and multivallate scarp-edge forts with measurable size data; the ghost excludes those identified also as contour forts. N=55.

Discussion

In writing about promontory forts almost 40 years ago, Raymond Lamb contended that they were a tradition in their own right and not simply a local adaptation of fort construction to a particular coastal setting (1980, 6). Even then, the case was hardly compelling, but in the light of the new data collected in the Atlas the limitations of his schematic distribution are starkly exposed. Promontories of all descriptions were exploited throughout Scotland, notably in inland settings too, and their natural attributes were merely one set of locational choices open to the builders of fortified enclosures. As we have seen in the varying proportions of promontory forts to other types of fort in Argyll and its islands, a longer hard-rock coastline of suitable type in proportion to the interior seems to have driven more extensive use of precipitous coastal promontories for forts. This reaches its extreme in the Northern Isles where all the known forts are in locations of this type. In effect, the new data turns Lamb’s argument on its head, to suggest that the establishment of fortifications, whether earthworks or

a wall, on a promontory was a normal local adaptation wherever suitable topography occurred.

That said, we should be wary of assuming that the construction of all forts are expressions of the same drivers. This paper has only referred to chronology obliquely, if only because the chronological data for promontory forts is slender at best and hardly sufficient to construct a detailed chronology at either a national or regional scale. Nevertheless, it is clear from the few reliable radiocarbon dates and artefacts from promontory forts that they range widely in date, for example, from the mid 1st millennium BC at Cults Loch, Wigtownshire [0343] (Cavers and Crone 2018, 143-8), to the late 1st millennium BC at nearby Carghidown [0229], and from the Roman Iron Age at West Mains of Ethie, Angus [3093], to the early medieval period at Burghead [2925] or Green Castle, Portknockie [2945], both in Morayshire. It is likely that others, such as Cullykhan [2982], enjoyed longer, or at least recurrent, use. It would be a mistake to assume that the reasons lying behind the construction of these fortified enclosures remained uniform across such a huge span of time, or

Halliday and Ian Ralston

indeed space, let alone that they necessarily mirror the construction of all other types of fort.

Indeed, the morphological observations recorded in the Atlas might lead to the very opposite conclusion. While some of the coastal promontories are in spectacular situations, the imposing nature of their settings does not necessarily equate with the character of their defences. Whereas some contour forts on hills and hillocks are prominently visible from the surrounding landscape, creating a commanding impression of strength in depth by stacking serried banks and ditches or walls on the slope, this is not an opportunity afforded many promontories. In this respect, a promontory fort like Kemp’s Walk, Meikle Larbrax, Wigtownshire [0122], is quite unusual; an enclosure of 0.37ha with a belt of three ramparts and ditches at its neck, it can be seen from over 1km away from across the valley to the east. The Unconfirmed enclosure on the Mull of Galloway [0201] would be another exception to the general pattern of more limited visibility from landward. Elsewhere along this stretch of coast, however, the view from the natural lines of access is more confined. Approached from along the cliff-line, for example, a series of promontories and inlets will often obscure a fort until the visitor is quite close by. In other examples, the approach may be from inland across relatively level ground or a convex slope, and the fort itself will remain invisible until the visitor is dropping down towards the very neck of the promontory. These are common characteristics of coastal promontories, and where they jut out into the sea there may be no lateral viewpoints on land from which to see the defences from any distance. Consequently, coastal promontory forts may be relatively intimate places that are only encountered when the visitor is already close at hand, rather than being locations that appear to command the landscape and attention from afar. In this sense, any visual impact of the defences upon the visitor is only achieved in the last few metres of the approach, and in some cases only when passing through the entrance. These same characteristics can also be found at some inland promontories, though the patterning of the size ranges of inland promontories in the Greater Tyne-Forth region, allied with those of the scarp-edge forts, would suggest that they are merely the extension of the settlement organisation represented by the mass of other forts and enclosures present there.

Having made the case that the selection of a promontory was a natural choice for a fort in many landscapes, this sense of intimacy, particularly in the locations of some coastal promontory forts, hints that perhaps not all these enclosed sites served the same functions, nor were they all normal building blocks in the contemporary settlement pattern. The excavator of Carghidown suggested that it had been an intermittently and briefly

occupied refuge (Toolis 2007, 310). It may be that other explanations should be sought for tiny enclosures such as Dunorroch, Wigtownshire [0199], set at the foot of the main cliff-line and entirely overlooked, and with jagged outcrops taking up most of its interior.

Some insights into the alternative uses of promontories is provided by a small group of northern promontory forts that incorporate structures known as blockhouses. This terminology not only implies a military function, but is taken directly from military vocabulary, though whether this is truly appropriate is debatable. Three are included in the Atlas, all on Shetland – Ness of Burgi [4180] and Tonga, Scatness [4181], on Mainland, and Burgi Geos on Yell [4169] – and have been marked as Confirmed. Each occupies a promontory with an isolated rectangular block of masonry set squarely across its axis and fronted by ditches and other features across the neck. Taken into Care in 1934 and excavated in 1936, Ness of Burgi is the archetypal example, measuring some 23.8m in length by between 5.6m and 6.4m in breadth and standing behind two ditches with a medial wall. The blockhouse is pierced by a central entrance passage furnished with door-checks and a bar-hole, and there are mural cells built into the thickness of the wall to either side; there was also a third mural cell, though it is not known how, or if, this was accessible. More recent excavation of the surviving west half of a second blockhouse nearby at Tonga likewise revealed a central checked entrance-passage and two mural cells, though the only access to the inner was by means of a creep no more than 0.2m high. In contrast to Ness of Burgi, this blockhouse, which had been extensively rebuilt in a second phase, stands eccentrically behind a broad ditch with an external bank; indeed the projection of the arc of the ditch into the eroded east sector implies the blockhouse was set across the centre of the interior when it was constructed. The third of this trio, Burgi Geos, is now one of the most remote forts anywhere in Britain. The ruinous blockhouse stands astride a narrow promontory immediately beyond a torturous approach, which drops down into the neck via a path lined with stones down one side, and a mound studded with upright slabs on the other; the latter are interpreted as the remains of a chevaux de frise

While at first sight these curious structures appear to be, and have been interpreted as fortified gatehouses, this explanation is less than entirely satisfactory. Unlike the walls and ramparts of other promontory forts, these blockhouses appear to have stopped short of the cliff-edges to either side of them, leaving unimpeded alternative access around their ends. Taken with the presence of inaccessible chambers within the walls, this perhaps suggests they were not strictly speaking fortifications. Possibly they reference other more esoteric symbolic practices connected with these places,

located at the hem of the land and the sea. This might accord with the spectacular character of the natural world as viewed from many coastal promontories set at the interface between land, sea and sky. This is a theme that might also be pursued in examining the distribution of early monastic sites on the coastal edge. The superficial similarity between, for example, the Inner Brough [4196] on Fetlar, Shetland, likely to have served a monastic community for at least some of its lifespan as an occupied site, and what is generally accepted as a substantial promontory fort at Dun Mhiughlaigh [2480] on Mingulay in the Outer Hebrides, is noteworthy. The latter, located on the exposed south-western side of Mingulay and out of all proportion to the size of the island, stands sentinel over the Atlantic with precipitous cliffs on virtually every side – a place that must always have been challenging for any habitation.

At present only five blockhouses are known for certain, all of them in Shetland, the additional examples being on small islands in lochs at Clickhimin and Whalsay, Loch of Huxter. Others have been claimed rather less convincingly in Orkney and Caithness, where Raymond Lamb (1980) raised the possibility that some of the promontory forts with thick inner walls may be hiding equivalent structures. There was certainly a mural chamber in the walls of the ‘outworks’ at Nybster [2820], and another at Crosskirk [4348], both in Caithness, but elsewhere at Dun Mhairtein, Sutherland [2788], the impression of a possible blockhouse is partly created by a central entrance and two successive phases of construction in which a wall about 4.2m thick has been superimposed on a massive dump rampart with an external ditch. A more likely possibility is the inaccessible Stac a’ Chaisteil on Lewis [2763]. No comparable structures have been identified any further south, but that is not to say that the philosophy behind their construction was not more widely rooted in Iron Age society.

Conclusion

We hope that the foregoing selective treatment of the promontory forts of Scotland offers some useful insights into the diversity of the evidence that needs to be taken into consideration in attempting to impose some order on these records. Sifting these examples from within the multifarious records of somewhat cognate sites that have been built up primarily since the nineteenth century has been shown recurrently to need the deployment of professional value judgement. This also impinges on the operation of particular thresholds for inclusion or exclusion. Amongst the series of sites included in the Atlas database, promontory forts are far from unique in posing these kinds of issues.

What the online database allows however, is for anyone to extract the data we have employed in the building of our interpretations of the meaning of components

of this data and to reconfigure it as they judge fit. With what is in some regards such fuzzy data, this is only appropriate.12

Acknowledgements

The Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland Project was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (2012-16). The Co-I was Professor Gary Lock (Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford); and data collection for Ireland was undertaken with assistance from Professor William O’Brien, University College, Cork. For this paper, Dr Val Turner (Shetland Amenity Trust) provided assistance with data on promontory forts in Shetland. The maps were prepared by Dr Paula Levick.

Reference list

Alcock, L. 1981 Early historic fortifications in Scotland. In Guilbert, G. Hillfort Studies: Essays for A. H. A. Hogg, 150-80. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

Alcock, L. and Alcock, E A. 1992 ‘Reconnaissance excavations on Early Historic fortifications and other royal sites in Scotland, 1974-84; A, Excavations and other fieldwork at Forteviot, Perthshire, 1981; B, Excavations at Urquhart Castle, Inverness-shire, 1983; C, Excavations at Dunnottar, Kincardineshire, 1984’, Proc Soc Antiq Scot 122, 215-87.

Alcock, L., Alcock, E. A. and Foster, S. M. 1986 ‘Reconnaissance excavations on early historic fortifications and other royal sites in Scotland, 197484:1, excavations near St Abb’s Head, Berwickshire, 1980’. Proc Soc Antiq Scot 116, 255-279.

Anon 2017 ‘Pictish longhouse unearthed at Burghead fort?’, Current Archaeology 331, 12.

Burgess, C. 2008 Ancient Lewis and Harris. Lewis: Comhairle nan Eilean Siar.

Cavers, G. and Crone, C. 2018 A Lake Dwelling in its Landscape: Iron Age settlement at Cults Loch, Castle Kennedy, Dumfries and Galloway. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Childe, V. G. and Forde, D. 1932 ‘Excavations in two Iron Age Forts at Earn’s Heugh, near Coldingham’, Proc Soc Antiq Scot 66, 152-183.

Crone, A. and Hindmarch, E. 2016 Living and dying at Auldhame. The excavation of an Anglian monastic settlement and medieval parish church. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Fairhurst, H. 1984 Excavations at Crosskirk Broch, Caithness. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Monograph Series 3.

12 All calculations in this study were made in 2016 before the Atlas was published online. They are based on spreadsheets derived from the initial Filemaker Pro database employed on the project. Although the overall numbers for forts in these spreadsheets have been crosschecked against comparable searches of the online Atlas, datacleaning associated with the transfer to the online format may have led to some minor discrepancies in searches for points of detail.

Halliday and Ian Ralston

Halliday, S. P. 2019 ‘Forts and fortification in Scotland; applying the Atlas criteria to the Scottish dataset,’ in Lock and Ralston, 2019.

Halliday, S. P. and Ralston, I. 2009 ‘How many hillforts are there in Scotland?’ in Cooney, G., Coles, J., Ryan, M., Sievers, S. and Becker, K. (eds) 2009 Relics of old decency: Archaeological studies in later prehistory. Festschrift in honour of Barry Raftery, 455-467. Dublin: Wordwell.

Halliday, S. P. and Ralston, I. 2013 ‘Major forts and ‘minor oppida’ in Scotland: a reconsideration’, in Krausz, S., Colin, A., Gruel, K., Ralston, I. and Dechezleprêtre, T. (dir.) L’Age du Fer en Europe: mélanges offerts à Olivier Buchsenschutz, 219-234.

Bordeaux: AUSONIUS Editions Mémoires 32.

Harding, D. W. 2012 Iron Age hillforts in Britain and beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hunter, J. R. 1996 Fair Isle: the archaeology of an island community. Edinburgh: HMSO.

Lamb, R. G. 1980 Iron Age promontory forts in the Northern Isles. Oxford: Brit Archaeol Rep Brit Ser 79.

Lock, G. and Ralston, I. 2017 Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland. [ONLINE] Available at: https://hillforts. arch.ox.ac.uk

Lock, G. and Ralston, I. (eds) 2019 Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent: Papers from the Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland Conference, June 2017. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Lock, G. and Ralston, I. 2020 ‘A new overview of the later prehistoric hillforts of Britain and Ireland’ in Delfino, D., Coimbra, F., Cardoso, D. and Cruz, G. (eds) Late Prehistoric Fortifications in Europe: Defensive, Symbolic and Territorial Aspects from the Chalcolithic to the Iron Age. (= UISPP Metal Ages in

Europe Commission international conference, Sociedade Martins Sarmento, Guimaraes, Portugal, November 2017). Oxford: Archaeopress.

MacKie, E. W. 2007 The roundhouses, brochs and wheelhouses of Atlantic Scotland c. 700 BC – AD 500. Architecture and material culture Part 2, the northern and southern mainland and the western islands. Oxford: Brit Archael Rep Brit Ser 444.

MacKie, E. W. 2016 Brochs and the Empire. The impact of Rome on Iron Age Scotland as seen in the Leckie broch excavations. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Nesbitt, C., Church, M. J., and Gilmour, S. M. D. 2011 ‘Domestic, industrial, (en)closed? Survey and excavation of a Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age promontory enclosure at Gob Eirer, Lewis, Western Isles’, Proc Soc Antiq Scot 141, 31-74.

Past Horizons. 2015 ‘Earliest Pictish fort yet discovered was situated on sea stack’. Past Horizons. http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/index. php/archives/07/2015/earliest-pictish-fortyet-discovered-was-situated-on-sea-stack. Last consulted 9th August 2018.

Strachan, R. 2000 ‘Mull of Galloway linear earthworks’, Discovery and Excavation Scotland 1, 21.

Toolis, R. 2003 ‘A Survey of the Promontory Forts of the North Solway Coast’, Trans Dumfries Galloway Nat Hist Antiq Soc 77, 37–78.

Toolis, R. 2007 ‘Intermittent occupation and forced abandonment: excavation of an Iron Age promontory fort at Carghidown, Dumfries and Galloway’, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 137, 265–318.

Toolis, R. 2015 ‘Iron Age settlement patterns in Galloway’, Trans Dumfries Galloway Nat Hist Antiq Soc 89, 17-34.13

13 This paper was revised for submission in 2018 and has only been slightly updated thereafter. The final Atlas has now been published and is supported by online data as outlined on p. xvi of that volume. Lock, G. and Ralston, I 2022 The Atlas of the Hillforts of Britain and Ireland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.